Nate Silver's Blog, page 61

August 5, 2019

Is The Field Too Big For Kamala Harris?

In theory, the easiest way to win a presidential nomination is to bring the various wings and factions of your party together toward some type of consensus. Not every voter has to love you (although some of them probably should or you won’t have a base). But they should all at least like you.1 Usually, this is accomplished by adopting policy positions that represent a rough average of the voters in your party — and which are also fairly closely aligned with the views of party elites who can influence the nomination process.2

Kamala Harris is one example of a candidate who has rather explicitly been pursuing this strategy. She’s not the most moderate candidate in the field, nor is she the furthest to the left. Rather, she has tried to calibrate herself somewhere in between. As a black, Asian, 54-year-old woman, she’s also more reflective of the Democraric Party’s demographic mix than some of the septuagenarian white men she’s running against. It’s for these reasons that I’ve generally been optimistic about her chances.

Harris’s performance in last week’s debate gave me reason for pause, however. In particular, the long opening section on health care was a problem for her. It came just a couple days after Harris released her own health care plan, which might loosely be called “Medicare Advantage for All” — where private insurers offer a set of Medicare-regulated plans that Americans can choose to buy into instead of using government-run Medicare — and which represents something of a compromise between Joe Biden’s and Bernie Sanders’s respective approaches. But she’s had trouble defending her plan, which has taken incoming fire both from Sanders and from Biden. The debate helped to reveal several potential problems with Harris’s strategy:

The fact that your policy positions closely resemble those of voters on average doesn’t necessarily mean they reflect a lot of voters’ first choice — and being voters’ first choice is how you win primaries. On health care, for instance, there might not be that many voters who prefer Harris’s compromise approach to both Biden’s public option and to Sanders’s purer form of “Medicare for All,” each of which are fairly easy to explain to voters.

The media tends to frame policy arguments between the candidates in a way that maximizes conflict. If you don’t clearly stand on one side or another of that conflict, you won’t get as much media attention, which, other things held equal, is a valuable resource in the primary.

If you get too cute in tailoring your positions — as Harris has done on some issues — you may develop a reputation as being too triangulating, or as flip-flopping, or even as being less “authentic”3 than candidates whose positions are easier to place into a neat ideological box.

Finally, more nuanced policy positions may simply be harder to describe persuasively in short sound bites, which is all that candidates get most of the time, especially in debates where 10 candidates are on stage.

Some of these problems are going to get better for Harris as the number of candidates dwindles. And she has a lot of options: If she and Sanders or Elizabeth Warren are the final survivors after the early states vote, she could run to the center; if it’s Harris and Biden, she can run to his left.

But it’s worth remembering that the previous times parties have had very large fields, they produced eccentric nominees — George McGovern in 1972, Jimmy Carter in 1976, and Donald Trump in 2016 — who weren’t really pursuing any middle-ground or coalition-building or triangulation strategy. (The opposite, really, in the case of Trump and McGovern.) That isn’t a large sample, and Harris is still among the Democrats most likely to win the nomination. But she’s increasingly at risk of becoming the Marco Rubio in a field of candidates who have more distinctive pitches to voters.

Read the previous entry in Silver Bulletpoints .

And check out the latest polls we’ve collected ahead of the 2020 elections, including all the Democratic primary polls .

August 2, 2019

Live From Detroit: The Post-Debate State Of The Primary

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

In a live taping of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast in downtown Detroit, the crew discusses key takeaways from the second Democratic primary debate. And the team competes in a 2020 Democratic presidential draft, debating which candidates are most likely to win the nomination. Plus, Robert Yoon of Inside Elections joins to talk about the present and future of Michigan politics.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

August 1, 2019

Where I Think The Candidates Stand After The Second Debate

I’m writing this on Thursday morning, before there’s much, if any, polling available that reflects how Democrats’ preferences changed following the two-night presidential debate this week. But even before the debate, some candidates had been on the move in the three weeks since my last comprehensive assessment of the Democratic field.

So let’s do another installment of my not-to-be-taken-too-seriously presidential tiers, based on polling shifts over the past few weeks, an evaluation of who’s likely to qualify for the third Democratic debate in September, and my initial impressions of the debate this week.

Nate’s not-to-be-taken-too-seriously presidential tiers

For the Democratic nomination, as revised on Aug. 1, 2019

Tier

Sub-tier

Candidates

1

a

Biden

b

Warren, Harris ↓

2

a

Sanders

b

Buttigieg, Booker ↑

3

a

Klobuchar ↑, Castro ↑

b

O’Rourke, Yang ↑

4

a

Bullock ↑, Inslee, Gillibrand, Gabbard ↑

b

Everyone else

First things first: Joe Biden is pretty clearly out in front, so I don’t quite get why prediction markets only have him in a rough tie with Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren. Pre-debate, he led his nearest competitors (Bernie Sanders and Warren) by 16 to 17 points in the RCP polling average, a margin that’s nothing to be sneezed at given the historical accuracy of primary polls at this stage. And he’s shown some resilience, having already bounced back in the polling average to where he was before the first debate, and then having had a second debate which — while it wasn’t great, in my view — was better than the first one despite a lot of incoming fire from other Democrats. I’m still a seller of the proposition that Biden is an odds-on favorite to win the nomination — that is, I think his chances are under 50 percent. But I think he’s more likely than anyone else.

With that said, I’d keep an eye on Warren, whose strong first-night performance looks better by comparison after a series of uneven evenings for the Democrats last night. She has a clearer message than Harris, and she makes for a sharper contrast to Biden, whom she hasn’t had a chance to share a debate stage with yet.

For that matter, I am almost tempted to say that Sanders’s chances have become underrated if prediction markets have him at under 10 percent to win the nomination. (He’s been hovering at between 6 percent and 9 percent in recent days at Betfair.) I think Sanders has quite a lot of issues that limit his upside, but those seem to be priced into the conventional wisdom about his chances in a way they weren’t before. And I thought Sanders had a pretty good debate. I’m keeping him at the top of Tier 2 for now, but he’s poised to move back into Tier 1 if the next few polls showing him gaining ground.

I do have Cory Booker moving up a tier, from Tier 3 to Tier 2. He was maybe the strongest performer last night from start to finish, he’s been getting more media attention, and he’s poised to benefit from any loss of support from Harris.

In the lower tiers, it’s mostly a matter of which candidates are actually likely to make the debate stage next time around, something that Amy Klobuchar, Julián Castro, Beto O’Rourke and Andrew Yang can probably be more confident about than any of the others. Sure, Yang would be a less traditional nominee than the rest of the group. But all of these folks are polling at 1 to 3 percent, so putting him in this group isn’t exactly showering him with praise. And I thought he and Castro had stronger debates than Klobuchar and O’Rourke.

If I had to pick someone from among the Tier 4 candidates, it would probably be Montana Gov. Steve Bullock, who was among the stronger performers on Tuesday night, and who has a variety of interesting attributes (electability, executive experience, a mix of moderation and economic populism) that differentiate him from the field. But he’s far from qualifying for the next debates, so he’s going to have to find some way to command attention in what could be a slow period for the campaign.

July 31, 2019

Debate Podcast: The Moderates Push Back

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

After a first round of Democratic primary debates in which the conversation seemed to be guided by candidates further to the left, disagreements between moderates and progressives took center stage on the first night of the second round of debates. In this installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, Nate Silver and Galen Druke discuss what went down in Detroit on night one.

FiveThirtyEight On The Road is brought to you by WeWork. You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

July 30, 2019

What We’re Watching For In The Second Democratic Debate

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): It’s hard to believe it’s been a month, but the Democratic primary debates are baaack. And on Tuesday and Wednesday evening, 20 candidates (10 each night) will take the stage, with one potentially big new showdown (Elizabeth Warren vs. Bernie Sanders) on the first night and one big rematch (Kamala Harris vs. Joe Biden) on the second night.

For reference, here’s Tuesday’s lineup: Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Pete Buttigieg, Beto O’Rourke, Amy Klobuchar, Marianne Williamson, John Delaney, John Hickenlooper, Tim Ryan, Steve Bullock.

And Wednesday’s: Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, Cory Booker, Andrew Yang, Julián Castro, Tulsi Gabbard, Michael Bennet, Jay Inslee, Kirsten Gillibrand, Bill de Blasio.

So yes, let’s talk about the lineups and matchups, but first let’s also take a step back to talk about the role of primary debates — how do they change the race?

nrakich (Nathaniel Rakich, elections analyst): I think it’s clear that debates can change the race. But the effects might be fleeting, as after one debate the race might move in one direction while subsequent debates might push things in a different direction.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Debates also tend to ramp up in importance as the campaign goes along. It might feel like we’ve been covering this race forever. But we’re still in the rather early stages, as far as voters are concerned.

julia_azari (Julia Azari, political science professor at Marquette University and FiveThirtyEight contributor): I think I might have a slightly different take on this than Nate. My sense, based on the research, is that the debates will produce diminishing returns as opinions become solidified, but that might apply more for minor candidates than for contention between major ones like Harris and Biden. (Though there’s still a notable big name-recognition gap between the two.)

nrakich: I’m with Julia on this one. In 2016, the first Democratic primary debate had the highest ratings.

natesilver: But in some sense, the purpose of these early, very-inclusive debates is to see if any of the minor candidates can break through. Which didn’t really happen after the Miami debates, although you could argue the case for Castro I guess.

sarahf: Castro was interesting. His favorability numbers shot up, but he didn’t really see as much of a swing in support, or at least that is what we found in our poll with Morning Consult.

nrakich: But Castro is a great example of someone for whom the debates could build on each other to increase his support. He got people’s attention in the first debate; maybe, with another good moment this week, he’ll start to get their support. Or at least get enough backing to clear the third-debate thresholds.

natesilver: I’m skeptical that Castro is likely to break through. I mean, shouldn’t we take the opposite lesson from the first debates, in fact? That you can have a good debate and it doesn’t help you break through because the top of the field is pretty entrenched?

nrakich: We didn’t say he was likely to, though — just that the possibility existed.

He’s already at 130,000 donors, the threshold for the third debate, in large part due to his first debate performance.

natesilver: I guess I’m just saying that I think people are maybe underestimating how much voters like the top-tier candidates when they say they expect a middle-tier candidate to break out.

julia_azari: What we’ve seen so far leaves me questioning whether the top tier is really open to newcomers at this point. I think there’s contention over who will be in that second tier of candidates who meet the requirements for the fall debates, but most of those candidates won’t come close to winning the nomination.

sarahf: Or maybe even making the next debate!

This might be the last time we see many of these candidates on stage because September’s qualifying thresholds will be difficult for them to meet. (Candidates must have at least 2 percent support in four recent qualifying polls1 and 130,000 unique donors.2)

natesilver: There are a lot of middle-tier candidates, so what are the odds that at least one of them will break into the top tier at some point in the race? Maybe fairly high. Let’s say it’s 60 percent, just to make a number up. But that 60 percent is divided between a lot of different candidates.

sarahf: OK, so as to this top-tier vs. middle-tier debate …

Let’s look at night one and unpack some of the dynamics there. As a reminder, night one includes: Sanders, Warren, Buttigieg, O’Rourke, Klobuchar, Williamson, Delaney, Hickenlooper, Ryan, Bullock.

So given the lineup, there’s potential that some of the more moderate candidates — say, Buttigieg, O’Rourke and Klobuchar — maybe try to position themselves against Warren or Sanders, right? And that can maybe help them break through to the top tier? Or at least make the top tier look less fixed?

julia_azari: Yeah, “Can a middle-tier candidate move up?” seems like the unofficial slogan of night one.

sarahf: More so than night two?

julia_azari: I think so. But I reserve the right to flip-flop if one of you convinces me.

nrakich: Agreed, and in fact I’d pay even closer attention to the lower-tier candidates: Hickenlooper, Ryan, Bullock, Delaney. They know that this is their last chance to make a splash before the third debate’s stricter thresholds. And they all have little love for Sanders’s socialism/Warren’s progressivism.

I think they will lash out pretty hard.

julia_azari: And, in fact, I might convince myself to flip-flop because of the timing. If Buttigieg, O’Rourke or Klobuchar has a strong performance (say, on the level of Castro last time) and emerges as the official Biden Alternative for the Heartland Moderate (or whatever, don’t @ me), I think there’s still a strong chance that something else happens on night two that overshadows it.

nrakich: I also think the potential for Sanders-Warren fireworks is overrated. Despite their ideological similarities, they aren’t really competing for the same bloc of voters. Warren supporters are more likely to be higher-income or have a college degree, while Sanders’s support is more working-class.

natesilver: I strongly disagree with Rakich on the Sanders-Warren lanes thing!

sarahf:

July 29, 2019

Politics Podcast: Are Democrats Moving Too Far Left?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

Many of the Democrats running for president in 2020 have staked out positions to the left of traditional Democrats on topics like health care, taxes and immigration. New polling shows that while some of those positions are broadly popular, others don’t register majority support even among Democrats. In this installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew considers the general election risks for 2020 candidates who take unpopular positions. The team also tracks Democratic lawmakers’ debate over whether to begin impeachment proceedings against President Trump in the wake of special counsel Robert Mueller’s testimony.

Also, weâre recording a live podcast in Detroit on Aug. 1! For more information and to get tickets, go here.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the âplayâ button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for âgood polling vs. bad pollingâ? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

15 Percent Is Not A Magic Number For Primary Delegates

If you hear the phrase âdelegate mathâ and remember 2016, you might have some nightmares. Thatâs because Republicans, who briefly kinda sorta looked like they might have a contested convention, have incredibly complicated delegate-allocation rules. Some states were winner-take-all in the GOP primaries. Some were proportional. Some states didnât even really vote at all (!) or had voters chose delegates directly. It was a mess.

Democratic delegate rules are far more uniform from state to state — and theyâre much simpler. But there are a couple of nuances that I can imagine people are going to get wrong.

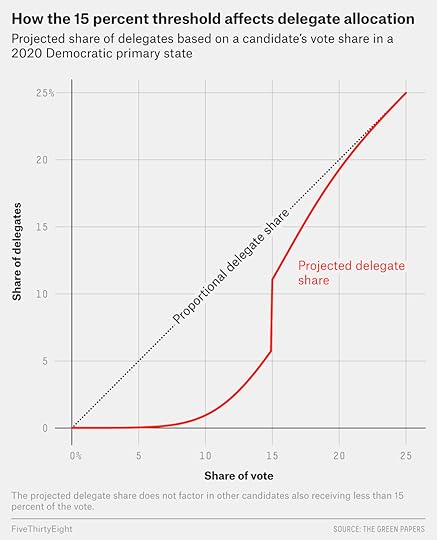

One of them concerns the 15 percent threshold, which is a number that youâre going to be hearing a lot about. Democrats allocate their delegates proportionately among candidates who get 15 percent or more of the vote in a given state or district. So, for instance, if Bernie Sanders gets 42 percent of the vote in a certain state, Kamala Harris gets 18 percent, Joe Biden gets 14 percent, Pete Buttigieg gets 11 percent, Cory Booker gets 10 percent and Marianne Williamson gets 5 percent, then only Sanders and Harris would get state-level delegates, with Sanders getting 70 percent of the delegates1 and Harris getting the other 30 percent.

The part thatâs easy to miss is in that term state-level delegates. In the Democratic primaries, only about 35 percent of delegates are actually allocated at the state level. The remaining 65 percent are allocated by district — usually by congressional district, although some states use different methods such as by county (Montana and Delaware) or state legislative districts (Texas and New Jersey).

This can make a big difference. In the example above, for instance, if Biden were to get 14 percent of the vote statewide, he probably would get some delegates because heâd likely be at or above 15 percent in at least some districts.

How many delegates is harder to say; it depends on how much variation there is from district to district. But for some rough guidance, I looked back at candidates who finished with between 10 and 20 percent of the vote in the Republican primaries in 20162 in states that allocated some of their delegates by congressional district.3 In the average district, there was about a 3-point gap between a candidateâs statewide vote share and that candidateâs districtwide vote share.

By performing a little math,4 we can extrapolate how many district delegates weâd expect a candidate to get given a certain statewide vote share. For instance, a candidate who gets 14 percent of the vote statewide, as Biden did in this example, would expect to achieve at least 15 percent in somewhere around 40 percent of districts, thereby receiving delegates there. Even a candidate who got 10 percent of the vote or less statewide might have a couple of strong districts where he or she received delegates, especially in a large, diverse state such as California.

On the flip side, a candidate who finished just above 15 percent statewide, such as Harrisâs 18 percent in this example, would probably still miss out on a few district-level delegates by falling below 15 percent in some districts.

Overall, considering both state and district delegates, the relationship between statewide vote share and the share of statewide delegates looks something like this:

Thereâs still a big spike at 15 percent when the statewide delegates kick in, but it isnât completely an all-or-nothing proposition; youâll still get some delegates if you finish a bit below 15 percent, and youâll still miss out on some if you finish just above 15 percent. The safest bet, of course, is to finish at 20 percent or higher, in which case youâll not only get almost all of your delegates but will also have the chance to actually win the state.

Laura Bronner contributed research.

July 25, 2019

Medicare For All Isn’t That Popular — Even Among Democrats

Last week, I noted that Bernie Sanders is winning over Democratic primary voters on health care. Whether you love, hate or are indifferent toward his “Medicare for All” plan, polls show Sanders leading when Democratic voters are asked which candidate they think is best able handle to health care.

The thing is, though — according to new polling from Marist College this week — Sanders’s plan isn’t actually the most popular idea in the field. Instead, that distinction belongs to what Marist calls “Medicare for all that want it,” or what’s sometimes called a public option — something very similar to Joe Biden’s recently unveiled health care plan, which claims to give almost everyone “the choice to purchase a public health insurance option like Medicare.”

In the Marist poll, 90 percent of Democrats thought a plan that provided for a public option was a good idea, as compared to 64 percent who supported a Sanders-style Medicare for All plan that would replace private health insurance. The popularity of the public option also carries over to independent voters: 70 percent support it, as compared to 39 percent for Medicare for All.

Americans want Medicare for All … who want it

Share of respondents who agreed that these versions of a Medicare for All plan were a good idea

Dem.

Rep.

Ind.

Overall

Medicare for All, replacing private insurance

64%

14%

39%

41%

Medicare for All who choose it, allowing private insurance

90

46

70

70

Source: Marist COLLEGE

But none of this is meant to negate what I wrote last week. Sanders’s plan is still fairly popular with Democrats, and there’s more to winning elections than just picking whatever policies happen to poll best; Medicare for All is consistent with the sort of revolutionary change for which Sanders advocates.

At the same time, the public option is potentially a winning issue for Biden, and one that allows him to reinforce some of his core strengths. It offers greater continuity with the legacy of the Obama administration (since the public option is a more gradual change from Obamacare — not to mention, something Obamacare initially tried to include), and allows him to double down on his electability message, since it polls better than eliminating private insurance. That may be why Biden has gone on the offense against Medicare for All.

Stuck in the middle, as I wrote last week, are Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren, who (along with other Democrats) have co-sponsored Sanders’s bill rather than developing a health care plan of their own. They aren’t getting credit from voters for leading on health care like Sanders, and they’re also left defending a plan that isn’t as popular as Biden’s among Democrats nor very popular among general election voters. We’re not in the prediction business — that’s a lie, we are — but it wouldn’t be surprising in the least if one or both of them issued their own health care plan within the next few months.

Kamala Harris’s Debate Bounce Is Fading

We’ve documented for years how polls tend to rise and fall — in what are often fairly predictable patterns — after events like debates and conventions. In general, what suddenly goes up in polls tends to gradually come back down after a matter of a few weeks. Conventions typically produce polling swings of 4 to 6 percentage points toward the party that just nominated its candidate, for instance — but the polls usually revert back to about where they were before after a few weeks.

We’ve also repeatedly seen this pattern after various Democrats declared for the race this year. Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, Kamala Harris and even Beto O’Rourke all got noticeable bounces when they officially declared for the presidency, only to fall back to their pre-declaration averages later on.

It looks as though something like this is happening again following the first Democratic debate last month. If you look at the RealClearPolitics average:

Biden has rebounded to 28.4 percentage points from a low of 26.0 percentage points just after the debate. He was at 32.1 percent before the debate, so he’s regained about two-fifths of what he lost.

Harris has fallen to 12.2 percentage points from a peak of 15.2 percentage points. She was at 7.0 percent before the debate, so she’s lost about a third of what she’d gained.

Harris is still in better shape than she was before the debates, but she’s currently 16 points behind Biden instead of looking like she’s on the verge of overtaking him.

I’ll be honest … as predictable as this pattern is, it’s easy even for professionals like me to get caught up in the moment, especially in the early stages of a race before we’re using any sort of model to smooth the data out.7 If a candidate rapidly goes from 7 to 15 in the polls, our unconscious, System 1 reflex is to assume the trend will continue, and that the candidate will continue gaining ground — to 20 points, 25 points and beyond. More often than not, though, the candidate loses ground after a sharp rise.

Why this pattern occurs is somewhat beyond the scope of this short article. But one contributing factor may be nonresponse bias — after a good debate for Harris and a poor one for Biden, for instance, Harris supporters may be more likely to respond to polls and Biden ones less so. I tend to think this phenomenon is a little overstated and that an easier answer is simply that a lot of voters don’t have deep convictions about the race until much later, and so bounce around among whichever candidates have gotten favorable press coverage recently. We’ll save that discussion for another time, though.

So it’s worthwhile to be at least a little bit skeptical of rapid, news-driven swings in the polls. By contrast, slow-and-steady gains or losses in the polls — say, Warren’s gradual improvement over the past few months or Sanders’s gradual decline — are often more durable.

Kamala Harrisâs Debate Bounce Is Fading

Weâve documented for years how polls tend to rise and fall — in what are often fairly predictable patterns — after events like debates and conventions. In general, what suddenly goes up in polls tends to gradually come back down after a matter of a few weeks. Conventions typically produce polling swings of 4 to 6 percentage points toward the party that just nominated its candidate, for instance — but the polls usually revert back to about where they were before after a few weeks.

Weâve also repeatedly seen this pattern after various Democrats declared for the race this year. Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, Kamala Harris and even Beto OâRourke all got noticeable bounces when they officially declared for the presidency, only to fall back to their pre-declaration averages later on.

It looks as though something like this is happening again following the first Democratic debate last month. If you look at the RealClearPolitics average:

Biden has rebounded to 28.4 percentage points from a low of 26.0 percentage points just after the debate. He was at 32.1 percent before the debate, so heâs regained about two-fifths of what he lost.

Harris has fallen to 12.2 percentage points from a peak of 15.2 percentage points. She was at 7.0 percent before the debate, so sheâs lost about a third of what sheâd gained.

Harris is still in better shape than she was before the debates, but sheâs currently 16 points behind Biden instead of looking like sheâs on the verge of overtaking him.

Iâll be honest … as predictable as this pattern is, itâs easy even for professionals like me to get caught up in the moment, especially in the early stages of a race before weâre using any sort of model to smooth the data out.1 If a candidate rapidly goes from 7 to 15 in the polls, our unconscious, System 1 reflex is to assume the trend will continue, and that the candidate will continue gaining ground — to 20 points, 25 points and beyond. More often than not, though, the candidate loses ground after a sharp rise.

Why this pattern occurs is somewhat beyond the scope of this short article. But one contributing factor may be nonresponse bias — after a good debate for Harris and a poor one for Biden, for instance, Harris supporters may be more likely to respond to polls and Biden ones less so. I tend to think this phenomenon is a little overstated and that an easier answer is simply that a lot of voters donât have deep convictions about the race until much later, and so bounce around among whichever candidates have gotten favorable press coverage recently. Weâll save that discussion for another time, though.

So itâs worthwhile to be at least a little bit skeptical of rapid, news-driven swings in the polls. By contrast, slow-and-steady gains or losses in the polls — say, Warrenâs gradual improvement over the past few months or Sandersâs gradual decline — are often more durable.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 730 followers