Nate Silver's Blog, page 58

September 25, 2019

If This Is Trump’s Best Case, The Ukraine Scandal Is Looking Really Bad For Him

Sometimes, when a news story is still unfolding in real time, we canât do much better than to hazard a guess about how it will affect the polls. Of course, we can also not hazard a guess — that is, we can not say anything about it at all. But given that I wrote yesterday about public opinion surrounding the impeachment of President Trump, this is one time when I think itâs worth weighing in on the latest development; namely, the White Houseâs decision to release, on Wednesday, Trumpâs reconstructed conversation (note: not a verbatim transcript) with Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky.

This conversation seems to have triggered a nearly Yanny or Laurel-like reaction in my Twitter feed, almost as though people are seeing and hearing two different things. Everyone either seems to think itâs either really bad for Trump, or not very damaging at all, with few people landing in between.

And Iâm not that rare person who hears it both ways. No. Iâm on the side that says itâs bad for Trump. And like the Yanny or Laurel thing or The Dress, I have trouble seeing how people see it any other way.

But Iâd also say you shouldnât take that guess very seriously. Our track record when using statistical models is pretty darn good, but when Iâm in guess mode, I donât claim to be much better than a replacement-level pundit.

With that said, there is a little bit of polling data that points in the bad-for-Trump direction (more about that in a moment). And for the record, this is relatively new territory for me. Up until now, Iâve been skeptical of the political wisdom of impeachment for Democrats, as yesterdayâs post detailed.

The logic behind my this-is-bad-for-Trump guess is that the White Houseâs record of Trumpâs conversation with Zelensky represents the best–case scenario for Trump. And that best-case scenario is still potentially fairly bad for him. They have Trump on record as imploring a foreign leader to investigate Joe Biden, one of his most likely opponents in the 2020 general election.

The White Houseâs spin is that the conversation is exculpatory because it doesnât contain a âquid pro quoâ — that is, a direct and explicit threat to Zelensky or a direct and explicit promise to him — in exchange for turning the screws on Biden. The problem for the White House is that its spin presumes three things to be true, all of which seem debatable:

First, it presumes that the public actually cares about the quid pro quo, rather than viewing Trump telling a foreign leader to investigate a political rival as a prima facie abuse of presidential powers. Or, to use a term that Trump wouldnât like, the public might see it as prima facie evidence of âcollusionâ between Trump and a foreign power that aims to influence the election — the sort of direct evidence that was lacking in the Mueller report.

Second, the White House line presumes that the public wonât see the White Houseâs record of the conversation as containing a quid pro quo. But there are plenty of readings by which it does. In the conversation, Trump directly invokes the idea of âreciprocityâ between the United States and Ukraine. He says âwe do a lot for Ukraine â¦. We spend a lot of effort and a lot of time.â Zelensky also discusses the purchase of Javelin missiles from the U.S. All of this comes before two fairly direct requests — Trump calls the first one a âfavorâ — that Trump makes of Zelensky, one concerning a cybersecurity firm called CrowdStrike and the other concerning Biden.

Third, it presumes that there wonât be more evidence of a quid pro quo that emerges later on. Given how rapidly the story is developing, that doesnât seem like a safe bet, either.

You might object that the public wonât care so much about the technical details here. But that potentially cuts both ways. The public could view the quid pro quo part to be a technicality and see Trumpâs âfavorsâ/demands/requests of Zelensky to be the nut of the story.

And keep in mind that Trump has more to lose than to gain when it comes to public opinion on impeachment. Until now, a fairly sizable number of voters — somewhere around 15 percent of the electorate — has both disapproved of Trump and disapproved of efforts to impeach him. If the hardcore Trump partisans are the only ones who believe the White Houseâs spin, his impeachment numbers would get worse, although his approval ratings might not.

As far as polling evidence for how the public feels about Ukraine, there isnât much of it, but there is some, and it isnât great for Trump. A YouGov poll on Tuesday asked voters how theyâd feel about impeachment if Trump âsuspended military aid to Ukraine in order to incentivize the countryâs officials to investigate his political rivalâ; 55 percent of voters supported impeachment in that case, 26 percent opposed it. The problem is that, so far, the delay in military aid has not been proven to be related to Trumpâs requests of Zelensky on Biden.1 We donât know how much that matters to the American public. Hopefully, pollsters will ask voters different versions of questions about impeachment over Ukraine that can test the importance of the quid pro quo. Meanwhile, polling from Reuters/Ipsos suggests that while relatively few Americans knew much about the Ukraine scandal before today, those who had heard of it were more supportive of impeachment.

Thatâs all weâve really got to work with, for now. We will, of course, track the polls in the upcoming days.

September 24, 2019

Politics Podcast: Why Pelosi Announced An Impeachment Inquiry

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

In this installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics Podcast, the crew discusses House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s decision to formally launch an inquiry into whether President Trump should be impeached. How did Democrats get to this point, and what might come next?

You can listen to the episode by clicking the âplayâ button above or by downloading it in Apple Podcasts, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Elections podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts. Have a comment, question or suggestion for âgood polling vs. bad pollingâ? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Impeaching Trump On Russia Was Unpopular. Will Ukraine Be Different?

Rather suddenly, we are on a trajectory toward the potential impeachment of President Trump.

Both close allies of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and vulnerable Democrats in swing districts have signaled their desire this week to pursue impeachment proceedings over President Trumpâs alleged efforts to induce Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky into investigating Joe Biden, whose son Hunter Biden served on the board of a Ukranian gas producer during Bidenâs tenure as vice president. A majority of House Democrats had already expressed a desire to impeach Trump over his conduct toward Russia in the 2016 campaign and his handling of the Russia investigation, but the list of pro-impeachment Democrats then included relatively few from competitive districts, and Pelosi had largely held the reins against impeachment.

This time is different. Although the story is still unfolding as I write this, impeachment is, at a minimum, highly plausible. And if Pelosi wants impeachment — as she reportedly does — she can probably get it. Democrats have a fairly comfortable majority in the House and they have been relatively unified under Pelosi. Betting markets, which had been bearish on impeachment, now assign around a 50 percent chance that Trump will be impeached (but not necessarily removed from office) during his first term.

But Democrats had better hope that something else is different this time too: public opinion. Despite Trump being quite unpopular, and despite the public largely buying Democratsâ interpretation of the fact pattern on Russia — most polls find that a majority of the public thinks that Trump sought to obstruct the investigation into Russia, for instance — impeachment was a soundly unpopular proposition.

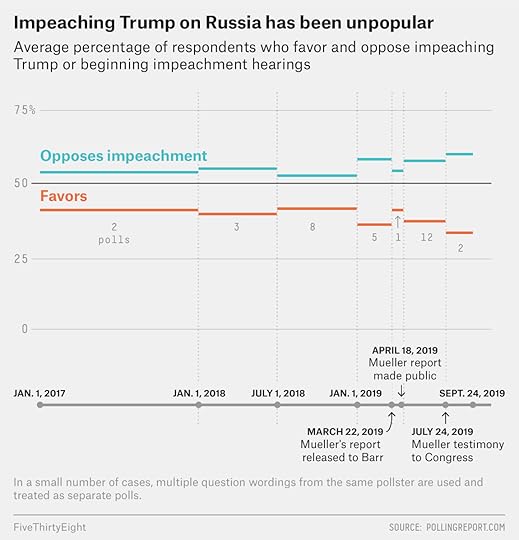

In the table below, Iâve compiled data on all polls from PollingReport.com, a compendium of high-quality telephone surveys, on whether the public thinks Trump should be impeached or at least that Congress should begin impeachment proceedings.1 And despite the slightly different question wordings — you could favor holding hearings on impeaching Trump but not actually favor his impeachment per se2 — these polls have tended to produce similar results: Impeachment was an unpopular option through the entirety of the Russia investigation process.

On average, in all polls since the start of 2017, 38.5 percent of the public favored impeachment and 55.7 percent opposed it, which is fairly close to a mirror image of Trumpâs approval and disapproval ratings. And there had been absolutely no sign that the public was moving toward impeachment. If anything, the opposite was true and impeachment had become slightly less popular. Polls conducted after the release of special counsel Robert Muellerâs report to the public on April 183 showed an average of 37.3 percent of the public favoring impeachment, and 57.3 percent opposed. The two polls in the database conducted since Muellerâs testimony to Congress on July 24 showed even worse numbers: 33.5 percent in favor of impeachment and 59.5 percent against.

This article is meant to be forward-looking, rather than a comprehensive analysis of all facets of public opinion related to the Russia investigation. But numbers like these ought to at least give Democrats pause. Heretofore, quite a lot of voters have both disapproved of Trumpâs conduct and disapproved of impeaching him.

Why this gap has persisted isnât entirely clear. Pelosiâs reluctance on impeachment undoubtedly dissuaded some Democratic voters from getting on board; the most recent Quinnipiac poll found only 61 percent of Democrats in favor of impeachment and 29 percent opposed. Those numbers may increase now that House leadership is coming around to impeachment.

The same poll, however, found independent voters mostly against impeachment — 62 percent opposed it to 28 percent in favor. Thatâs despite Trump having only a 35 percent approval rating among independents in the poll. So impeachment has given Democrats problems among swing voters as well.

Another explanation may simply be that the public has a high threshold for impeachment, especially for an elected president and especially especially when that president will be on the ballot again soon. By contrast, Andrew Johnson was an unelected president when he was impeached — he had taken over the presidency after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. And the impeachment proceedings against Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton took place in their second terms. Voters may not think Russia met that threshold; in fact, the Russia investigation itself was the lowest priority for midterm election voters among 12 issues that Gallup asked about last year.

One explanation that doesnât make any sense — but which seems to come up from pro-impeachment partisans every time Iâve pointed out impeachmentâs lack of popularity — is the notion that the Democrats simply werenât focused enough on the Russia investigation or that the public didnât know enough about it. In fact, the Russia investigation has been one of the most focused-upon news stories of our lifetime; it was the most-covered story of 2017 on the network news and the second most-covered of 2018 after Brett Kavanaughâs confirmation hearings. And the public has not moved toward impeachment as more and more facts have been revealed about Russia, including Muellerâs exhaustive report. This is despite the fact that, as I mentioned — feel free to browse the polling results yourself — the public mostly agrees with the Democratsâ interpretation of Muellerâs findings; they do not think the report cleared Trump of wrongdoing, for instance.

Other Democrats like to cite the fact that impeachment against Nixon was initially fairly unpopular. But this comparison doesnât entirely work either. Rather dramatic facts were being revealed throughout the Watergate investigation and impeachment process, which tended to sway public opinion. By contrast, the outlines of Muellerâs eventual findings were largely laid out for the public a long time ago, through Muellerâs various indictments and through reporting at places such as the Washington Post and the New York Times. Whereas for the past year or so at least, Democrats have had relatively little new material to work with on Russia. The increasing numbers of House Democrats who called for impeachment over the past few months didnât seem to move public sentiment in Democratsâ favor either.

Again, none of this is meant to provide for an absolutely definitive analysis of how public opinion might have evolved if Democrats had proceeded on impeachment as a result of the Russia investigation. The sample size of impeachments is small, which make any conclusions tentative. But that uncertainty doesnât necessarily work to Democratsâ benefit, given that the status quo is fairly promising for them electorally: Trump is quite unpopular and, although these polls donât mean much at this stage, he currently trails all his major Democratic rivals (especially Biden, but also Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren) in head-to-head matchups. Democrats are also coming off a strong midterm.

The politics of impeachment on Ukraine may be different than on Russia. But Democrats should take public opinion seriously. That doesnât mean you always have to do the poll-driven thing. But donât wish the numbers away because you donât like them, or presume that theyâll change in your favor, or assume there wonât be consequences for taking an unpopular action.

More specifically for Democrats, their failure to persuade the public that Russia warranted impeachment offers several potential lessons if they are to proceed on Ukraine:

Lesson No. 1: Be narrow and specific, perhaps with a near-exclusive focus on Ukraine. For some Democrats in Congress who were nearly ready to impeach Trump over Russia, Ukraine may have been the proverbial straw that broke the camelâs back. But Democrats probably shouldnât portray it to the public that way.

The public was largely not persuaded about the wisdom of impeaching Trump on Russia. And Ukraine provides a much clearer story, in some ways: Trump allegedly pressured a foreign leader to undermine one of his chief rivals in the 2020 election. Itâs not a case of the cover-up being worse than the crime, or of Trump attempting to obstruct the investigation, or of actions that took place before Trump took office. Itâs a direct, recent and relatively simple throughline. The more focused Democrats are on Ukraine specifically, the better chance that public opinion will turn out better for them than it did on Russia.

Even worse for Democrats than combining Ukraine and Russia would be to offer a laundry list of impeachment charges, involving the emoluments clause or Trumpâs general conduct in office or what not. The public has a high threshold for what constitutes impeachable conduct, so reasons that are below that threshold might weaken the overall case for impeachment rather than being additive.

Furthermore, such a strategy would tend to play into the White Houseâs strengths. The White House is fairly skilled at muddying the news cycle and navigating its way through the swampy thicket of a story in ways that can fatigue the public. It isnât a perfect analogy, but in the Kavanaugh hearings, the sheer volume of accusations against Kavanaugh eventually helped him; the less credible allegations allowed Kavanaugh and the White House to cast doubt on the more credible ones, such as Christine Blasey Fordâs. Throwing more accusations or alleged reasons for impeachment at Trump could likewise allow the White House to focus on the weakest ones.

Interestingly enough, the Washington Post op-ed by seven first-term Democrats calling for impeachment solely referred to Ukraine as a potential cause for impeachment. So Democratic leadership may agree with this strategy.

Lesson No. 2: Donât overpromise on details unless you can deliver. Youâll sometimes hear the sentiment that the entire Mueller Report might have been more politically damaging to Trump if it had dropped all at once instead of slowly being teased out through indictments and news accounts and investigative reports over the course of two years. That seems reasonable enough, although thereâs no way to test the hypothetical. Itâs also true, though, that the publicâs reaction to news events — and the mediaâs reaction to news events, which conditions the publicâs response — is often calibrated relative to âexpectations.â If the expectations get too far ahead of themselves, even a relatively damaging story may land with a thud.

Without relitigating the Mueller Report more than we have to, itâs safe to say that it provided neither the total exoneration that the president claimed, nor the direct evidence of collusion with Russia that Democrats might have been hoping for. Thatâs to say nothing of the breathless speculation about what the Mueller Report would say on cable news, or the too-frequent reporting missteps on important Russia-related stories (even if, in my view anyway, the press largely got the big picture right on Russia).

The fact that Ukraine is a much simpler story than Russia again works to Democratsâ benefit here: There are fewer details to screw up. But if Democrats promise caught-red-handed evidence above and beyond whatâs been made public already (the White House has not exactly been steadfast in its denials) and doesnât deliver on it, itâs obviously going to injure their case. And it should go without saying that the more damaging the information, the harder it could be for Democrats to obtain. That Trump has pledged to release a âfully declassified and unredacted transcriptâ of his phone conversation with Zelensky might make Democrats a little nervous since Trump presumably wouldnât release it so soon if it contained many bombshells.

Lesson No. 3: Emphasize the threats to election integrity. As I mentioned, I suspect (though I certainly canât prove) that some of the publicâs reluctance on impeachment over Russia stemmed from the fact that Trump was still in his first term and is running for re-election. We want to decide this one for ourselves, the public may have been saying.

In some ways, thatâs a bigger problem for Democrats on Ukraine, since the election is even closer now. But, of course, the Ukraine scandal involves the 2020 election: Trumpâs efforts to impair Bidenâs candidacy. My point is simply that Democrats should emphasize that angle since any impeachment hearings would take place directly against the backdrop of the election, a prospect that voters might otherwise find strange.

Lesson No. 4: Stay unified. As I said above, I donât think Democratic infighting over impeachment on Russia explains all, or necessarily most, of its unpopularity with the general public. But it probably explains some of it. This tends to be one of Pelosiâs strengths, but the more Democrats are willing to sink or swim together on Ukraine impeachment, the more compelling their message is liable to be to the general public.

Lesson No. 5: Work quickly and urgently. Now that theyâve seemingly decided to move forward on Ukraine, there are lots of reasons for Democrats to move fast. It will reduce the potential for public fatigue over the story, which can set in quickly for all news stories in the Trump era. And a sense of urgency could underscore some of the other themes here, e.g. that thereâs an immediate threat to the integrity of the 2020 election, to national security, or both.

Obviously, Democrats will need to weigh moving rapidly against Lesson No. 2 (the risk of getting too far ahead of themselves). Nobody said impeachment would be easy for anyone involved!

But the other benefit to moving fast is that, if impeachment backfires on Democrats and makes Trump more popular, Democrats will have more time to recover from that. Impeachment isnât necessarily an all-in bet for Democrats, but itâs an awfully big one.

September 23, 2019

Politics Podcast: Are Democrats Ready To Impeach Trump?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

Democrats are once again talking about whether to impeach President Trump after news broke that Trump may have asked the Ukrainian president to dig up dirt on former Vice President Joe Biden’s son, Hunter. In this installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew discusses whether the Ukraine story changes Democrats’ calculus on whether to vote to impeach Trump. The team also discusses whether Elizabeth Warren is now the front-runner in Iowa.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the âplayâ button above or by downloading it in Apple Podcasts, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Elections podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts. Have a comment, question or suggestion for âgood polling vs. bad pollingâ? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

September 19, 2019

2019 College Football Predictions

How this works: Our model uses the College Football Playoff (CFP) selection committeeâs past behavior and an Elo rating-based system to anticipate how the committee will rank teams and ultimately choose playoff contestants, accounting for factors that include record, strength of schedule, conference championships won and head-to-head results. It also uses ESPNâs Football Power Index (FPI) and the committeeâs rankings to forecast teamsâ chances of winning. (Before Oct. 30, when the CFP will release its first rankings, the AP Top 25 poll is used instead.) The teams included above either have at least a 0.5 percent chance of making the playoff or are in the top 25 in at least one of the three rankings we use in our model: FPI, the Elo-based rating or CFP/AP. Every forecast update is based on 20,000 simulations of the remaining season. Full methodology »

Design and development by Jay Boice and Rachael Dottle. Statistical model by Nate Silver.

There’s A Better Case For A Top 2 Than A Top 3

Before last weekâs debate, I argued that there was a lot of ambiguity as to who belonged in the top tier in the Democratic primary. Depending on which factors you emphasized, the top group could plausibly consist of any number of candidates from one (Joe Biden) to five (Biden, Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Kamala Harris and Pete Buttigieg).

The Houston debate didnât upend the campaign overnight; polls since the debate donât show huge movement. You can, of course, find big swings for individual candidates in individual polls if youâre willing to cherry-pick, but you shouldnât do that.

The post-debate polls do, however, reinforce some trends that were already in the works before:

They tend to argue for the presence of a top two (Biden and Warren) as opposed to a top three (Biden, Warren and Sanders), especially if you look at polls of Iowa.

They make it awfully hard to argue that Harris belongs in the top tier. (I recently argued that Harris did belong in the top tier, so put that take in the âdidnât age wellâ bucket, at least for now.)

Meanwhile, a new trend since the debate is that several of the lower-tier candidates, such as Amy Klobuchar and Beto OâRourke, are showing slightly livelier numbers, although weâre still only talking the low-to-mid single digits.

Letâs touch on the new national and early-state polls, and then weâll revisit each of these themes. There are quite a few of these: seven new national polls conducted entirely since the Houston debate, which variously contain good news for Warren, Biden and Sanders. For the gory details of which polls are included and what they say, see the footnote.1

We also have two new polls of Iowa since the debate, which look good for Warren and Biden but not particularly for Sanders; instead, those polls show Buttigieg and (in one of the two polls) Klobuchar outperforming their national numbers.2

As I said, thatâs plenty of data to choose from — or to cherry-pick from — so this is precisely the sort of time when itâs useful to look at the polling average instead of individual polls. Since the new polls vary a lot in sample size and pollster quality, Iâve weighted the average using the same algorithm we use for our Trump approval ratings calculation:

Biden, Warren look strong in post-debate polls

Weighted average of national and Iowa polls since the Houston debate

National

Iowa

Candidate

Average

Trend

Average

Trend

Biden

30.2%

0.2

20.6%

-0.2

Warren

20.4

0.7

23.5

2.8

Sanders

16.6

-0.6

12.5

-2.2

Buttigieg

5.8

-0.1

12.5

2.8

Harris

5.8

-2.2

5.0

-8.2

O’Rourke

3.1

1.2

1.5

0.2

Yang

2.8

0.8

2.5

1.3

Booker

2.6

0.7

2.0

0.0

Klobuchar

1.4

0.3

5.5

2.4

Castro

1.0

0.1

0.5

-0.3

The trend reflects the average change as compared to the previous, pre-debate edition of the same poll, except in the case of the Civiqs Iowa poll, where it reflects a comparison to the average of all Iowa polls in August. Only candidates who participated in the third debate are listed in the table.

Thereâs not a ton of movement in the national polls. On average, Biden held steady at 30 percent. Warren and Sandersâs position isnât much changed, but she does appear to be about 4 points ahead of him nationally and has continued to gain ground slowly but steadily, having now reached 20 percent in the polling average. The biggest gainer since the debate is actually OâRourke, who added an average of 1.2 percentage points, although that still puts him only in the low-to-mid single digits. The biggest loser is Harris, who is down to only about 6 percent and lost another 2 points or so in the most recent round of polls, although some of that movement predates the debate itself.

In Iowa, the major headline is that Warren and Biden form a clear top two in the post-debate polls — a clearer top two there than in national polls. Iowa has always looked like a relatively strong state for Warren and a weak one for Biden, so this isnât a huge surprise, but the trends are nonetheless favorable for Warren. The rest of the field also looks a bit different in Iowa than it does nationally; as I mentioned, the Midwestern candidates — Klobuchar and especially Buttigieg — are doing quite a bit better in the Hawkeye State. Sanders, meanwhile, is surprisingly weak in Iowa given that he nearly won the state last time around, although other Iowa polls have shown better numbers for him than the two released since the debate. The new edition of the Selzer/Des Moines Register poll is due out soon, which should help us to confirm whether the new polls are a trend or a fluke.

For me, that all adds up to something like this:

Nateâs not-to-be-taken-too-seriously presidential tiers

For the Democratic nomination, as revised on Sept. 19, 2019

Tier

Sub-tier

Candidates

1

a

Biden

b

Warren

2

a

Sanders â

b

Harris â, Buttigieg

3

a

Yang, O’Rourke, Klobuchar, Booker

b

Castro

4

a

Steyer â, Gabbard â

b

Everyone else

None of this looks dramatically different than before the debate, but to revisit those themes I touched on before …

Theme No. 1: Thereâs a better case for a Top 2 (Biden, Warren) than a Top 3 (Biden Warren Sanders). Iâve done something slightly sneaky with my tiers, which reflects the fact that Warrenâs position continues to improve incrementally — rather than meteorically — relative to Sandersâs. As before, I have Sanders as the third most likely Democrat to win the nomination. (Keep in mind that these rankings arenât driven by any sort of statistical model;3 theyâre my subjective opinion, which sticks fairly closely to be polls but doesnât omit other factors entirely.) But Iâm demoting him to tier 2a from tier 1c. (Iâm also demoting Harris, who has bigger problems than Sanders does — see the next item.)

You could argue that Sanders and Warren belong in the same tier since theyâre almost tied in national polls. But they arenât quite tied anymore; Warren is ahead in the average of national polls, as you can see above.

That alone might not be enough to put Warren in a higher tier than Sanders. But virtually every other polling-based metric other than the topline numbers in national polls tends to favor Warren over Sanders:

As I mentioned, sheâs doing a fair bit better than Sanders in Iowa, especially in post-debate polls. (New Hampshire, where there hasnât been any post-debate polling, is more of a mess.)

She has equal favorable ratings to Sanders and Biden, but lower unfavorable ratings, meaning that sheâs more broadly acceptable to Democratic voters; she also tends to do better than Sanders when polls ask about votersâ second choices or which candidates theyâre considering.

Although past movement in the polls doesnât necessarily predict future movement, she obviously has the most momentum, having slowly but steadily gained in the polls for several months now.

In Iowa, and increasingly in national polls, she generates more enthusiasm than other candidates, including Sanders.

She does considerably better than Sanders among Democrats who are paying the most attention to the race, possibly a leading indicator of what will happen as more voters tune into the campaign later on.

And although the gap is closing, sheâs still slightly less familiar to voters than Sanders, which implies that she has more room to grow.

The one factor working in Sandersâs favor is that his coalition appears to be a bit more diverse in terms of race and educational status; Warren is eventually going to have to expand her coalition beyond liberal, college-educated whites. On the other hand, Sanders has historically had problems with several major Democratic constituencies, including blacks over the age of 40, whites over the age of 55, and moderate voters of all races and ages. Overall, even from a âpolls onlyâ perspective, Warren is now in a meaningfully better position than Sanders.

And if you look at non-polling factors, the gap between Warren and Sanders increases. Empirically, the best way to look at the primaries apart from polls is through a âParty Decidesâ perspective, wherein so-called âparty elitesâ — influential Democrats such as elected officials — are instrumental in picking the nominee, or at least are a leading indicator of voter preferences. Sanders is a problematic and even implausible nominee by this metric; he rather proudly doesnât get along with the party establishment (and technically isnât even a Democrat) and instead is running more of a factional campaign where he hopes to win the largest plurality of voters rather than necessarily uniting the party. Warren also doesnât do terrifically well in this framework. (Party elites seem to prefer Biden and Harris.) But she has more endorsement points than Sanders does, and thereâs lots of reporting to suggest that she has better relationships with party insiders than him. Particularly in the event of a contested convention, when superdelegates are allowed to vote on the second and subsequent ballots, this could be a big advantage for her. Sheâs also winning more support from progressive groups and organizations such as the Working Families Party and MoveOn.org which may or may not get along with the Democratic Party establishment, but can help to turn out voters in primaries and caucuses.

So while I donât know that Iâd go as far as prediction markets, which have Warren with a 35 to 40 percent chance of winning the nomination and Sanders at only 10 to 15 percent, thereâs quite a bit to differentiate them, with most of the indicators in Warrenâs favor.

As to whether Warren is more likely to win the nomination than Biden, Iâm not quite ready to go there yet. (I still have Biden in tier 1a and Warren in tier 1b.) As my colleague Clare Malone likes to say on our podcast, Biden is still the âstatistical frontrunnerâ: If you built a model consisting solely of objective indicators — e.g. national polls, Iowa polls, endorsements — heâd probably still be ahead. That isnât necessarily the only way to look at the nomination. But Iâd like to see Warren win a few more endorsements, and Iâd like to see a couple more polls showing her leading in Iowa and New Hampshire, before removing Bidenâs front-runner status. Warren is also near an empirical inflection point in national polls; once you get to 20 percent or so, you go from a factional candidate to a real threat to win the nomination. To the extent she can continue gaining ground — going from 20 percent to 25 percent, say — that would be a pretty huge deal for her, especially if those gains came from voters other than college-educated white Democrats.

Theme No. 2: Harris is in trouble. As I said earlier, Iâve mostly been bullish on Harris throughout the campaign. Sheâs a strong âParty Decidesâ candidate and sheâs still second in endorsements behind Biden, although her pace of endorsements has slowed since a flurry of them after the Miami debate. But sheâs in real danger now. Rather than uniting the party, sheâs losing college educated liberals to Warren and black voters to Biden. Sheâs also well behind in polls of Latino voters.

Thereâs still plenty of time to turn it around, but the risk is that donors, voters and potential endorsers abandon her for a candidate who appears to have more momentum. (Harrisâs fundraising totals for the third quarter, which closes on Sept. 30, will reportedly be weak.) Buttigieg has caught up with her to tie for fourth place nationally and is in a stronger position than her in Iowa and New Hampshire. And OâRourke, Cory Booker and even Andrew Yang are right on her heels nationally. Media coverage is also a factor here: If media coverage that was once devoted to Harris begins to go to candidates such as OâRourke and Booker instead, that could deepen her problems. And Iâm not sure that refocusing her campaign on Iowa, her latest strategic gambit, is going to help.

Theme No. 3: Thereâs a little bit of life in the third tier. I donât want to overstate this, since going from 2 percent to 3 percent means youâre still ⦠at 3 percent. But (with the exception of Julián Castro) this is the best set of polling for candidates outside of the top 5 in a while. Thatâs not entirely surprising, since voters gave several of these candidates — notably Klobuacher, OâRourke, Yang and Booker — relatively good marks for their debate performances. If anything, the problem is that a number of these candidates had strong evenings, so voters who were shopping around for new alternatives were divided several ways between them.

Perhaps the most interesting number of all in the new set of polling was Klobucharâs 8 percent in the David Binder poll of Iowa; among other things, a Klobuchar mini-surge in Iowa could cause big problems for Biden by crowding the moderate/electability lane there. But that number hasnât been replicated in other surveys yet.

All of this does leave one to wonder whether candidates such as Booker and Klobuchar were hurt by the large field and getting mixed up with the Marianne Williamsons and Eric Swalwells of the world. Iâll stick with what I said last week: If youâre polling in the low single digits, youâre probably toast. But letâs hold off on declaring their campaigns dead until at least the next debate.

Politics Podcast: We Ran Into Andrew Yang At The Airport

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

You never know who you’ll run into at the airport. Following last week’s debate, FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver and Galen Druke ran into Democratic primary candidate Andrew Yang. We asked him if he would record a podcast while waiting for a flight, and he obliged. In this installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, Yang discusses his campaign strategy, internal polling and push for a universal basic income. After the interview, Nate and Galen discuss some of Yang’s responses and what his trajectory in the race might look like.

.@NateSilver538 and I ran into @AndrewYang while waiting for the same flight out of Houston. We recorded a podcast and will drop it when the time is right. pic.twitter.com/4BYTMng0vw

— Galen Druke (@galendruke) September 13, 2019

You can listen to the episode by clicking the âplayâ button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen . The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Mondays and Thursdays.

Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for âgood polling vs. bad pollingâ? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

September 18, 2019

What Issues Should The 2020 Democratic Candidates Be Talking About?

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): Last Thursday, the 2020 Democratic candidates covered a wide range of topics during the three-hour debate, including health care, race and criminal justice, immigration, gun control and climate change.

But what issues do voters care most about? In our FiveThirtyEight/Ipsos poll, conducted using Ipsos’s KnowledgePanel, we surveyed the same set of respondents both before and after the debate to find out what issue was most important in determining their vote in the primary. And what we learned was Democrats are most concerned about defeating President Trump — nearly 40 percent of respondents said this was their top issue. For reference, the next-most-common top issue — health care — was picked by just 10 percent voters before the debate and 11 percent after.

So what issues should the candidates be talking more about? Less about? And if Democrats care more about winning this year, what’s the best way to talk about beating Trump?

A lot of Democrats really want to beat Trump

Share of respondents to the FiveThirtyEight/Ipsos poll who said that each issue is the most important to them, before and after the debate

Share for whom issue is most important

issue

Pre-debate

Post-debate

Ability to beat Donald Trump

39.6%

–

39.6%

–

Health care

9.9

–

11.0

–

The economy

8.0

–

8.7

–

Wealth and income inequality

7.9

–

8.4

–

Climate change

7.4

–

6.5

–

Gun policy

4.2

–

4.8

–

Immigration

3.3

–

3.7

–

Something else

3.3

–

3.5

–

Social Security

3.4

–

3.2

–

Education

2.5

–

2.4

–

Racism

3.0

–

2.4

–

The makeup of the Supreme Court

1.7

–

1.7

–

Taxes

1.3

–

1.3

–

Jobs

1.9

–

1.1

–

Foreign affairs

1.3

–

0.7

–

Crime

0.7

–

0.4

–

The military

0.3

–

0.4

–

Sexism

0.1

–

0.2

–

From a survey of 4,320 likely Democratic primary voters who were surveyed between Sept. 5 and Sept. 11. The same people were surveyed again from Sept. 12 to Sept. 16; 3,473 responded to the second wave.

nrakich (Nathaniel Rakich, elections analyst): Well, to state the obvious, the candidates should be talking about their ability to beat Trump.

It’s important to a ton of Democratic voters.

And the more it goes untalked-about, the more other candidates are ceding that ground to Joe Biden, IMO.

Electability is a very fuzzy concept without a ton of data behind it, so pretty much any candidate can make a plausible argument for their “electability.”

sarahf: What are some ways candidates can do that, though?

I know Biden has leaned into his performance in head-to-head polls against Trump, but as we know … general election polls don’t really tell us that much about the strength of candidates in the primary.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): I mean, it’s a little tricky. If you talk too much about electability, you raise the salience of the issue, which might work to Biden’s benefit.

ameliatd (Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux, senior writer): On the other hand, the fact that electability is a fuzzy concept can also be difficult for the candidates to address directly — for example, the female candidates.

nrakich: Amelia, if you ask me, the female candidates should be trotting out the studies that show women do just as well as men when they run for office!

ameliatd: Well, but those studies aren’t about presidential candidates! Most political scientists agree that people don’t cross the aisle to vote against a woman (or for that matter, to vote for a woman) — party loyalties are stronger than gender bias. But that’s not an easy sound bite, and it also may not be especially reassuring to voters who think sexism was a factor in Hillary Clinton’s loss in 2016.

natesilver: In particular, I think it’s risky (by which I mean dumb) for any candidate other than Biden to talk much about his or her head-to-head polls against Trump, because Biden still does better than any other Democrat in those polls by some margin.

sarahf: But is that what will convince voters someone is electable?

nrakich: Amy Klobuchar is pointing to her past election results, where she really ran up the score in the swing state of Minnesota, as evidence that she’s electable. The problem is that she just hasn’t gotten a lot of attention for it (although voters in our poll thought she was slightly more likely to beat Trump after the debate).

sarahf: How else can candidates talk about their ability to defeat Trump without getting into their performance in head-to-head polls?

natesilver: I thought Warren’s response to Delaney in the second debate was good. Basically, like, if you’re not running on ideas, then why are you even running?

nrakich: If you’re Klobuchar, you can also argue that a moderate candidate is better positioned to win over swing voters. Or if you’re Kamala Harris or Cory Booker, you can argue that a black candidate will have the most success increasing black turnout (which could help Democrats win back Midwestern states like Michigan and Pennsylvania and might put new states, like Georgia, in play).

natesilver: I’m not sure that the candidates themselves do a lot of good by litigating more complex points about electability with the public. Their campaigns might do it on background with journalists, but it’s probably best left there.

ameliatd: I agree with that, Nate. One recent study did show that people were more likely to rate female candidates as electable when they were first reminded about how many women won in 2018 — but I don’t think having the candidates make that pitch will necessarily work.

sarahf: But if the best way for a candidate to run is on their ability to beat Trump, how can their stances on other issues help them accomplish that? Or make them seem more electable?

Let’s start with an issue that a lot of voters also care about (it was the second most popular pick for top issue in our Ipsos poll) — health care.

Should Democrats talk about health care more?

Less?

nrakich: Exit polls showed that health care was the most important issue to voters in the 2018 midterm elections, which obviously worked out well for Democrats. So I think that’s good ground for the candidates to focus on for the general election.

For the primary, maybe less so — it depends on their position on health care!

natesilver: I remain convinced that health care is the best issue that Sanders has going for him.

Although, according to our poll, Biden actually gained ground with voters who prioritized the issue. Warren and Harris have been somewhat stuck in the middle on health care, though, and I think it’s a real problem for them.

nrakich: But Nate, what about those polls that show that a single-payer health care system is less popular, even among Democrats, than building on Obamacare (with, say, a public option)?

natesilver: At least Sanders has leadership on the issue. True, Biden has the most popular position. But Harris and Warren got nothing.

sarahf:

Who voters think is best on health care

Among the 435 respondents who said health care was the most important issue to them in an Ipsos/FiveThirtyEight poll

candidate

share of respondents

Bernie Sanders

32.9%

–

–

Joe Biden

28.8

–

–

Elizabeth Warren

16.5

–

–

Someone else

6.4

–

–

Pete Buttigieg

3.3

–

–

Kamala Harris

2.8

–

–

Amy Klobuchar

2.2

–

–

Julián Castro

1.5

–

–

Beto O’Rourke

1.3

–

–

Andrew Yang

1.3

–

–

Cory Booker

0.9

–

–

Poll was conducted from Sept. 5 to Sept. 11 among a general population sample of adults, with 4,320 respondents who say they are likely to vote in their state’s Democratic primary or caucus

Yeah, going into the debate, Sanders had the lead among voters in our poll who prioritized health care. (But Sanders wasn’t the only candidate to gain potential supporters among voters who prioritized health care after the debate — Biden, Yang, Warren and Buttigieg all made bigger gains.)

ameliatd: Part of the challenge, too, is that people still don’t understand the details of all of these plans — for example, Medicare for All, as Sanders and Warren talk about it, involves getting rid of private insurance. That could be more and more of an issue for the candidates on the left. Warren and Sanders keep saying people don’t like their insurance — but that’s not really true.

The health care debate is hard because people want something better, but they’re also afraid of losing what they have.

sarahf: Yeah, the branding of “Medicare for All who want it” that Buttigeig and others are pushing is pretty ingenious, even if it’s just as difficult or costly to pull off as the version of Medicare for All that Sanders and Warren are pitching.

ameliatd: It is weirdly off-brand for Warren to not have a detailed plan on health care. But maybe she’s trying not to get beaten up in the fight over Medicare for All.

natesilver: It’s very off-brand. And, sure, there might be tactical reasons for it. All of which goes to my theory that Warren is more of a politician than she’s assumed to be, which you’d think is a pretty normal thing to say about someone who’s a professional politician but will probably come across as something of a hot take.

I dunno, sometimes Warren’s strategy seems predicated on the idea that she doesn’t need to throw a lot of elbows or make a lot of tight pivots to beat Sanders.

sarahf: Well, if part of the primary is to pitch voters on big ideas, it makes sense to me that Warren isn’t curtailing her vision for Medicare for All just yet.

ameliatd: I wonder also if she thinks there’s too much competition on health care. It can be pretty difficult to follow which candidate is proposing what and what the actual differences are. It’s simpler to just say she’s with Sanders.

nrakich: I do find it interesting that Warren is doing so well in the polls despite not really emphasizing the top two priorities that Democratic voters cited in our poll (electability and health care).

sarahf: In its analysis of swing voters in 2020, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that in addition to having a big advantage on health care, Democrats have a whopping advantage (38 percentage points) on climate change.

So … should the candidates be talking about climate change more?

(According to an analysis by Bloomberg, only 6 percent of the third debate was devoted to it.)

nrakich: I think you have to draw a line between the primary and general election for a lot of these.

As you alluded to with that poll, Sarah, I think the eventual Democratic nominee could have success by talking a lot about climate change next year.

But the differences between the primary candidates on climate change are pretty in the weeds, so I’m not sure whom it would help to talk about it more.

I also think the failure of Jay Inslee’s campaign to win on climate change showed that the issue just wasn’t a big differentiator either (although IMO he had other problems too, like not being very inspiring on the stump).

sarahf: That’s interesting, Nathaniel. So unlike health care, where there’s an incentive for the candidates to hash out their differences, maybe something like climate change should be saved for the general?

nrakich: Yeah, I think there are pretty major differences between the candidates on health care. And having a nominee run on single-payer vs. a public option could be important to swing voters in the general. But I don’t think Republicans will attack a nominee any harder if he or she is trying to get the U.S. to net-zero carbon emissions by 2040 instead of 2050.

ameliatd: Well, another difference between health care and climate is that they’re both fairly technical, complicated issues, but one has a direct and personal impact on people’s health and bank accounts, while the other is more diffuse. It’s harder to get concrete on climate change, too. Which is sometimes why you end up with candidates talking about banning plastic straws.

natesilver: Also on climate — the political willpower to get things done when Joe Manchin is the median vote in the Senate is far less than any of the Democrats’ plans would like.

In some ways, I’m surprised Democrats haven’t spent more time talking about structural issues, like gerrymandering, adding new states (Puerto Rico, D.C.) and things of that nature.

sarahf: I mean, they did wade into blowing up the filibuster in the last debate.

Do you really think that’s good politics for the candidates, though?

natesilver: Oh yeah, sure. I think it’s a good way for Warren to differentiate herself from Sanders, for instance.

ameliatd: Blowing up the filibuster seems like it’s become a way for candidates to say they’re serious about passing their agenda. So it’s kind of a proxy for how far the candidates are willing to go, and how much they care about compromise.

nrakich: I think it has the potential to be good politics, Sarah. People don’t like it when they perceive the system to be unfair, and Democrats can pretty easily make the argument that the system is currently biased against urban dwellers, people of color and others.

Gerrymandering is a good example of something that few people defend. But no Democrat is out there shouting about it from the rooftops.

Voting rights also don’t register very high on the priority list when voters are asked what issues they care about, but there is a lot of political science research that says that politicians can influence what voters care about. And I bet the issue would become more salient if a top-tier candidate talked about it more.

ameliatd: I have also wondered why the Supreme Court hasn’t been a bigger issue so far — it is more unpopular with Democrats than it has been in 20 years, and progressive activists are advocating for some pretty big court reforms, like increasing the number of justices on the bench. And if you’re talking about roadblocks for your progressive agenda — a Supreme Court with a conservative majority is certainly at the top of that list.

nrakich: Maybe it hasn’t been very salient in the primary because it’s assumed that every possible nominee would appoint pro-choice, pro-voting-rights, generally liberal justices?

ameliatd: But there are differences between the candidates on how to approach the Supreme Court — big ones! At least seven candidates still in the race are open to the idea of adding justices to the court, according to The Washington Post. And some have talked about changing its structure in other ways (adding term limits, for example) which would also be quite dramatic.

nrakich: Good point. Maybe Democrats aren’t bringing it up, then, because the issue risks activating Republican voters in the general election?

ameliatd: It is definitely true that the courts historically have been a motivating issue for Republican voters and not really for Democrats. But I think there’s potential for the Democrats to make the Supreme Court into an issue that their voters care about.

natesilver: And I think after Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination last year, there’s still an open question about whether which party gets most motivated by the Supreme Court has shifted. In a Gallup poll just before the midterms, roughly as many Democrats as Republicans called Kavanaugh an important issue in deciding their vote.

That said, I don’t think calling for Kavanaugh’s impeachment is a very wise general election position.

ameliatd: No, I agree — a focus on impeaching Kavanaugh seems tailor-made to rile up Republicans. Part of the issue is that there just isn’t a clear message among Democrats about the Supreme Court or the judiciary in general. Some people want term limits. Others want court-packing, or they want more talk about the type of judicial nominees the candidates would nominate.

sarahf: But what about an issue where Democrats don’t have an advantage (like the economy) and are in a weaker position among voters than Trump? In that same poll on swing voters, KFF gave Trump a 12-point advantage for his handling of economy. And in our Ipsos poll, we found that economy-focused Democrats gave candidates worse marks across the board than voters focused on four other top issues, suggesting that economy voters were maybe unsatisfied by what they heard in the debate.

nrakich: Yeah, Democrats could stand to talk more in the primary about the economy in the traditional sense, like jobs.

For the general election, though, that does seem to be a good issue for Republicans (for now).

natesilver: Isn’t the obvious way for Democrats to talk about the economy to talk about inequality and how the economy ain’t workin’ for some people?

Unless the economy actually goes way south, in which case you have a lot more things you can say.

nrakich: Yes, but we did offer “wealth and income inequality” as an issue in our poll, and those voters seemed to have different perspectives than the “economy” voters.

If we’re talking about the primary, Warren and Sanders have gotten pretty far by talking about inequality, but our poll does suggest there’s a subset of voters for whom that isn’t what they want to hear about the economy.

sarahf: And while trying to motivate voters around economic inequality sounds good in theory, in practice, I don’t think it actually moves the dial much. Although, there is evidence that voters are keen on a tax on the uber-wealthy, so maybe that’s a good tack for Democrats to take in talking about the economy more?

ameliatd: Right, talking about making the wealthy pay their fair share seems like a smart way for Democrats to approach this.

But what do you think voters want to be hearing on the economy front, Nathaniel? In our poll, “jobs” was listed as a separate option and not that many people seemed interested in hearing about that.

nrakich: Yeah, Amelia, I’m not quite sure. Given their candidate preferences (i.e., voters who prioritized the economy also liked Biden and were much less likely to be considering a vote for Warren or Sanders), maybe those are the fiscally minded voters who oppose Warren and Sanders’s efforts to redistribute wealth.

In other words, business-friendly Democrats?

natesilver: Yeah, Democrats need to be careful on this issue.

Socialism is still not a popular concept with swing voters. Maybe it will be once the millennials and zoomers take over. But for now, it’s a big general-election vulnerability for Sanders, for instance.

nrakich: Wait, this is the first time I’ve heard zoomers as a nickname for Generation Z and I love it.

natesilver: “Let’s get the economy workin’ for workin’ people and make the rich pay their fair share” is probably fine for a general election message. “Let’s topple the entire system” maybe isn’t.

sarahf: But as Nathaniel said earlier … this is the primary. And isn’t socialism more popular than capitalism among Democrats?

So, similar to some of the candidates being more radical on health care, isn’t there an argument to be made they should dream bigger on the economy, too?

natesilver: Well, yeah, but part of what smart candidates do is avoid driving wedges on issues where it might give you a slight advantage in the primary but a big disadvantage in the general election.

nrakich: And while it’s true, Sarah, that Democrats think more highly of socialism than of capitalism, their views of capitalism are still mostly favorable, according to the Pew Research Center. We’re also forgetting that 40 percent of Democrats think the most important thing is to beat Trump! I can imagine plenty of pro-socialism Democrats being persuaded to tone down the rhetoric (but maybe not the policies — Warren is basically doing this) in order to avoid being general-election poison.

ameliatd: Also, isn’t Warren’s wealth tax, which would be applied to rich people’s accumulated fortunes rather than just their income, be an example of Democrats dreaming big? She seems to be doing a good job of selling it as “just making the rich pay their fair share,” but it’s still a pretty radical change from the status quo.

sarahf: That’s fair, Amelia.

And to wrap, if candidates could run on only one issue — and it isn’t beating Trump, because let’s treat that as the overarching argument of everyone’s campaign — what would it be?

nrakich: I think it’s got to be health care, especially if you’re not a single-payer Democrat. Follow the playbook that worked in 2018.

natesilver: It depends on the candidate. For Biden, it’s electability. For Sanders, it’s health care. For Warren, it’s … I’m not sure, exactly? But I think probably inequality.

nrakich: Breakin’ Sarah’s rules (“and it isn’t beating Trump”), Nate …

Intriguing side question: Is it a problem for Biden if he runs on an electability argument during the primary and then doesn’t have a clear rationale for running come the general?

sarahf: What other issue does Biden have to lean into? Health care, maybe?

natesilver: Maybe Biden could adopt a signature issue — or two.

I’m not sure what it would be, though. Guns, maybe?

ameliatd: We didn’t talk about gun policy, but I’ll be interested to see if that has sticking power as the primary moves forward. That’s a big priority for voters right now, but maybe it’s also an issue like climate change where the candidates struggle to differentiate themselves.

Also, I am shamelessly dodging the question, but personal characteristics are also important to voters. A Pew survey from last month asked Democrats to name the most important factor for deciding which candidate to support, and 28 percent named something like honesty or competence. About the same share pointed to a policy. So … maybe policy just matters less than we assume?

nrakich: Great point, Amelia. We basically just did a whole chat on issues while ignoring the fact that people mostly don’t vote on issues!

ameliatd: Shut it down, guys.

natesilver: But you can still vote on the aesthetics of a candidate’s policy positions even if you don’t care about policy per se.

Like, people can like the idea that Warren has a plan for things, even if they don’t know what those plans are, exactly.

nrakich: Right, but to the original chat prompt, does it matter, then, what issues are and aren’t being discussed?

As you pointed out, Warren doesn’t have a meaty health care plan but still gets credit for being issue-driven.

ameliatd: I wonder if Warren’s focus on an overarching theme like corruption can also help with the perception that she’s honest, or something like that.

But then it does make you wonder how much the details matter, as opposed to how the issues fit into a candidate’s overall brand.

September 16, 2019

Politics Podcast: How Both Partiesâ 2020 Primaries Are Going

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

The third Democratic primary debate is over, and the final result from our poll with Ipsos are in. In this installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew breaks down what we know about the winners and losers of last weekâs debate and talks about how the race has changed — or hasnât — as a result.

The team also discusses another primary race — the Republican primary. President Trump now has three challengers: Former congressman and South Carolina Gov. Mark Sanford, former Rep. Joe Walsh and former Massachusetts Gov. Bill Weld. Considering the president’s high approval rating among Republicans, the crew debates whether any of the challengers will affect Trumpâs chances.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the âplayâ button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen . The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for âgood polling vs. bad pollingâ? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Politics Podcast: How Both Parties’ 2020 Primaries Are Going

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

The third Democratic primary debate is over, and the final result from our poll with Ipsos are in. In this installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew breaks down what we know about the winners and losers of last week’s debate and talks about how the race has changed — or hasn’t — as a result.

The team also discusses another primary race — the Republican primary. President Trump now has three challengers: Former congressman and South Carolina Gov. Mark Sanford, former Rep. Joe Walsh and former Massachusetts Gov. Bill Weld. Considering the president’s high approval rating among Republicans, the crew debates whether any of the challengers will affect Trump’s chances.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen . The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 730 followers