Nate Silver's Blog, page 133

May 18, 2016

How I Acted Like A Pundit And Screwed Up On Donald Trump

Since Donald Trump effectively wrapped up the Republican nomination this month, I’ve seen a lot of critical self-assessments from empirically minded journalists — FiveThirtyEight included, twice over — about what they got wrong on Trump. This instinct to be accountable for one’s predictions is good since the conceit of “data journalism,” at least as I see it, is to apply the scientific method to the news. That means observing the world, formulating hypotheses about it, and making those hypotheses falsifiable. (Falsifiability is one of the big reasons we make predictions.1) When those hypotheses fail, you should re-evaluate the evidence before moving on to the next subject. The distinguishing feature of the scientific method is not that it always gets the answer right, but that it fails forward by learning from its mistakes.

But with some time to reflect on the problem, I also wonder if there’s been too much #datajournalist self-flagellation. Trump is one of the most astonishing stories in American political history. If you really expected the Republican front-runner to be bragging about the size of his anatomy in a debate, or to be spending his first week as the presumptive nominee feuding with the Republican speaker of the House and embroiled in a controversy over a tweet about a taco salad, then more power to you. Since relatively few people predicted Trump’s rise, however, I want to think through his nomination while trying to avoid the seduction of hindsight bias. What should we have known about Trump and when should we have known it?

It’s tempting to make a defense along the following lines:

Almost nobody expected Trump’s nomination, and there were good reasons to think it was unlikely. Sometimes unlikely events occur, but data journalists shouldn’t be blamed every time an upset happens,2 particularly if they have a track record of getting most things right and doing a good job of quantifying uncertainty.

We could emphasize that track record; the methods of data journalism have been highly successful at forecasting elections. That includes quite a bit of success this year. The FiveThirtyEight “polls-only” model has correctly predicted the winner in 52 of 57 (91 percent) primaries and caucuses so far in 2016, and our related “polls-plus” model has gone 51-for-57 (89 percent). Furthermore, the forecasts have been well-calibrated, meaning that upsets have occurred about as often as they’re supposed to but not more often.

But I don’t think this defense is complete — at least if we’re talking about FiveThirtyEight’s Trump forecasts. We didn’t just get unlucky: We made a big mistake, along with a couple of marginal ones.

The big mistake is a curious one for a website that focuses on statistics. Unlike virtually every other forecast we publish at FiveThirtyEight — including the primary and caucus projections I just mentioned — our early estimates of Trump’s chances weren’t based on a statistical model. Instead, they were what we sometimes called ”subjective odds” — which is to say, educated guesses. In other words, we were basically acting like pundits, but attaching numbers to our estimates.3 And we succumbed to some of the same biases that pundits often suffer, such as not changing our minds quickly enough in the face of new evidence. Without a model as a fortification, we found ourselves rambling around the countryside like all the other pundit-barbarians, randomly setting fire to things.

There’s a lot more to the story, so I’m going to proceed in five sections:

Our early forecasts of Trump’s nomination chances weren’t based on a statistical model, which may have been most of the problem.1. Our early forecasts of Trump’s nomination chances weren’t based on a statistical model, which may have been most of the problem.

2. Trump’s nomination is just one event, and that makes it hard to judge the accuracy of a probabilistic forecast.

3. The historical evidence clearly suggested that Trump was an underdog, but the sample size probably wasn’t large enough to assign him quite so low a probability of winning.

4. Trump’s nomination is potentially a point in favor of “polls-only” as opposed to “fundamentals” models.

5. There’s a danger in hindsight bias, and in overcorrecting after an unexpected event such as Trump’s nomination.

Usually when you see a probability listed at FiveThirtyEight — for example, that Hillary Clinton has a 93 percent chance to win the New Jersey primary — the percentage reflects the output from a statistical model. To be more precise, it’s the output from a computer program that takes inputs (e.g., poll results), runs them through a bunch of computer code, and produces a series of statistics (such as each candidate’s probability of winning and her projected share of the vote), which are then published to our website. The process is, more or less, fully automated: Any time a staffer enters new poll results into our database, the program runs itself and publishes a new set of forecasts.4 There’s a lot of judgment involved when we build the model, but once the campaign begins, we’re just pressing the “go” button and not making judgment calls or tweaking the numbers in individual states.

Anyway, that’s how things usually work at FiveThirtyEight. But it’s not how it worked for those skeptical forecasts about Trump’s chance of becoming the Republican nominee. Despite the lack of a model, we put his chances in percentage terms on a number of occasions. In order of appearance — I may be missing a couple of instances — we put them at 2 percent (in August), 5 percent (in September), 6 percent (in November), around 7 percent (in early December), and 12 percent to 13 percent (in early January). Then, in mid-January, a couple of things swayed us toward a significantly less skeptical position on Trump.

First, it was becoming clearer that Republican “party elites” either didn’t have a plan to stop Trump or had a stupid plan. Also, that was about when we launched our state-by-state forecast models, which showed Trump competitive with Cruz in Iowa and favored in New Hampshire. From that point onward, we were reasonably in line with the consensus view about Trump, although the consensus view shifted around quite a lot. By mid-February, after his win in New Hampshire, we put Trump’s chances of winning the nomination at 45 percent to 50 percent, about where betting markets had him. By late February, after he’d won South Carolina and Nevada, we said, at about the same time as most others, that Trump would “probably be the GOP nominee.”

But why didn’t we build a model for the nomination process? My thinking was this: Statistical models work well when you have a lot of data, and when the system you’re studying has a relatively low level of structural complexity. The presidential nomination process fails on both counts. On the data side, the current nomination process dates back only to 1972, and the data availability is spotty, especially in the early years. Meanwhile, the nomination process is among the most complex systems that I’ve studied. Nomination races usually have multiple candidates; some simplifying assumptions you can make in head-to-head races don’t work very well in those cases. Also, the primaries are held sequentially, so what happens in one state can affect all the later ones. (Howard Dean didn’t even come close to defeating John Kerry in 2004, for example, finishing with barely more than 100 delegates to Kerry’s roughly 2,700, but if Dean had held on to win Iowa, he might have become the nominee.) To make matters worse, the delegate rules themselves are complicated, especially on the GOP side, and they can change quite a bit from year to year. The primaries may literally be chaotic, in the sense that chaos theory is defined. Under these conditions, any model is going to be highly sensitive to its assumptions — both in terms of which variables are chosen and how the model is parameterized.

The thing is, though, that if the nomination is hard to forecast with a model, it’s just as hard to forecast without a model. We don’t have enough historical data to know which factors are really predictive over the long run? Small, seemingly random events can potentially set the whole process on a different trajectory? Those are problems in understanding the primaries period, whether you’re building a model or not.

And there’s one big advantage a model can provide that ad-hoc predictions won’t, which is how its forecasts evolve over time. Generally speaking, the complexity of a problem decreases as you get closer to the finish line. The deeper you get into the primaries, for example, the fewer candidates there are, the more reliable the polls become, and the less time there is for random events to intervene, all of which make the process less chaotic. Thus, a well-designed model will generally converge toward the right answer, even if the initial assumptions behind it are questionable.

Suppose, for instance, we’d designed a model that initially applied a fairly low weight to the polls — as compared with other factors like endorsements — but increased the weight on polls as the election drew closer.5 Based on having spent some time last week playing around with a couple of would-be models, I suspect that at some point — maybe in late November after Trump had gained in polls following the Paris terror attacks — the model would have shown Trump’s chances of winning the nomination growing significantly.

A model might also have helped to keep our expectations in check for some of the other candidates. A simple, two-variable model that looked at national polls and endorsements would have noticed that Marco Rubio wasn’t doing especially well on either front, for instance, and by the time he was beginning to make up ground in both departments, it was getting late in the game.

Without having a model, I found, I was subject to a lot of the same biases as the pundits I usually criticize. In particular, I got anchored on my initial forecast and was slow to update my priors in the face of new data. And I found myself selectively interpreting the evidence and engaging in some lazy reasoning.6

Another way to put it is that a model gives you discipline, and discipline is a valuable resource when everyone is losing their mind in the midst of a campaign. Was an article like this one — the headline was “Dear Media, Stop Freaking Out About Donald Trump’s Polls” — intended as a critique of Trump’s media coverage or as a skeptical analysis of his chances of winning the nomination? Both, but it’s all sort of a muddle.

Trump’s nomination is just one event, and that makes it hard to judge the accuracy of a probabilistic forecast.The campaign has seemed to last forever, but from the standpoint of scoring a forecast, the Republican nomination is just one event. Sometimes, low-probability events come through. Earlier this month, Leicester City won the English Premier League despite having been a 5,000-to-1 underdog at the start of the season, according to U.K. bookmakers. By contrast, our 5 percent chance estimate for Trump in September 2015 gave him odds of “only” about 20-to-1 against.

What should you think about an argument along the lines of “sorry, but the 20-to-1 underdog just so happened to come through this time!” It seems hard to disprove, but it also seems to shirk responsibility. How, exactly, do you evaluate a probabilistic forecast?

The right way is with something called calibration. Calibration works like this: Out of all events that you forecast to have (for example) a 10 percent chance of occurring, they should happen around 10 percent of the time — not much more often but also not much less often. Calibration works well when you have large sample sizes. For example, we’ve forecast every NBA regular season and playoff game this year. The biggest upset came on April 5, when the Minnesota Timberwolves beat the Golden State Warriors despite having only a 4 percent chance of winning, according to our model. A colossal failure of prediction? Not according to calibration. Out of all games this year where we’ve had one team as at least a 90 percent favorite, they’ve won 99 out of 108 times, or around 92 percent of the time, almost exactly as often as they’re supposed to win.

Another, more pertinent example of a well-calibrated model is our state-by-state forecasts thus far throughout the primaries. Earlier this month, Bernie Sanders won in Indiana when our “polls-only” forecast gave him just a 15 percent chance and our “polls-plus” forecast gave him only a 10 percent chance. More impressively, he won in Michigan, where both models gave him under a 1 percent chance. But there have been dozens of primaries and only a few upsets, and the favorites are winning about as often as they’re supposed to. In the 31 cases where our “polls-only” model gave a candidate at least a 95 percent chance of winning a state, he or she won 30 times, with Clinton in Michigan being the only loss. Conversely, of the 93 times when we gave a candidate less than a 5 percent chance of winning,7 Sanders in Michigan was the only winner.

WIN PROBABILITY RANGENO. FORECASTSEXPECTED NO. WINNERSACTUAL NO. WINNERS95-100%3130.53075-94%1512.51350-74%116.9925-49%124.025-24%222.410-4%930.91Calibration for FiveThirtyEight ”polls-only” forecastBased on election day forecasts in 2016 primaries and caucuses. Probabilities listed as ”>99%” and ”

WIN PROBABILITY RANGENO. FORECASTSEXPECTED NO. WINNERSACTUAL NO. WINNERS95-100%2726.72675-94%1513.11450-74%148.71125-49%134.835-24%273.110-4%880.81Calibration for FiveThirtyEight ”polls-plus“ forecastBased on election day forecasts in 2016 primaries and caucuses. Probabilities listed as ”>99%” and ”

It’s harder to evaluate calibration in the case of our skeptical forecast about Trump’s chances at the nomination. We can’t put it into context of hundreds of similar forecasts because there have been only 18 competitive nomination contests8 since the modern primary system began in 1972 (and FiveThirtyEight has only covered them since 2008). We could possibly put the forecast into the context of all elections that FiveThirtyEight has issued forecasts for throughout its history — there have been hundreds of them, between presidential primaries, general elections and races for Congress, and these forecasts have historically been well-calibrated. But that seems slightly unkosher since those other forecasts were derived from models, whereas our Trump forecast was not.

Apart from calibration, are there other good methods to evaluate a probabilistic forecast? Not really, although sometimes it can be worthwhile to look for signs of whether an upset winner benefited from good luck or quirky, one-off circumstances. For instance, it’s potentially meaningful that in down-ballot races, “establishment” Republicans seem to be doing just fine this year, instead of routinely losing to tea party candidates as they did in 2010 and 2012. Perhaps that’s a sign that Trump was an outlier — that his win had as much to do with his celebrity status and his $2 billion in free media coverage as with the mood of the Republican electorate. Still, I think our early forecasts were overconfident for reasons I’ll describe in the next section.

The historical evidence clearly suggested that Trump was an underdog, but the sample size probably wasn’t large enough to assign him quite so low a probability of winning.Data-driven forecasts aren’t just about looking at the polls. Instead, they’re about applying the empirical method and demanding evidence for one’s conclusions. The historical evidence suggested that early primary polls weren’t particularly reliable — they’d failed to identify the winners in 2004, 2008 and 20129 — and that other measurable factors, such as endorsements, were more predictive. So my skepticism over Trump can be chalked up to a kind of rigid empiricism. When those indicators had clashed, the candidate leading in endorsements had won and the candidate leading in the polls had lost. Expecting the same thing to happen to Trump wasn’t going against the data — it was consistent with the data!

To be more precise about this, I ran a search through our polling database for candidates who led national polls at some point in the year before the Iowa caucuses, but who lacked broad support from “party elites” (such as measured by their number of endorsements, for example). I came up with six fairly clear cases and two borderline ones. The clear cases are as follows:

From top left: George Wallace, Jesse Jackson, Gary Hart, Jerry Brown, Herman Cain and Newt Gingrich.

Getty Images

George Wallace, the populist and segregationist governor of Alabama, led most national polls among Democrats throughout 1975, but Jimmy Carter eventually won the 1976 nomination.Jesse Jackson, who had little support from party elites, led most Democratic polls through the summer and fall of 1987, but Michael Dukakis won the 1988 nomination.Gary Hart also led national polls for long stretches of the 1988 campaign — including in December 1987 and January 1988, after he returned to the race following a sex scandal. With little backing from party elites, Hart wound up getting just 4 percent of the vote in New Hampshire. Jerry Brown , with almost no endorsements, regularly led Democratic polls in late 1991 and very early 1992, especially when non-candidate Mario Cuomo wasn’t included in the survey. Bill Clinton surpassed him in late January 1992 and eventually won the nomination.Herman Cain emerged with the Republican polling lead in October 2011 but dropped out after sexual harassment allegations came to light against him. Mitt Romney won the nomination.Newt Gingrich surged after Cain’s withdrawal and held the polling lead until Romney moved ahead just as Iowa was voting in January 2012.Note that I don’t include Rick Perry, who also surged and declined in the 2012 cycle but who had quite a bit of support from party elites, or Rick Santorum, whose surge didn’t come until after Iowa. There are two borderline cases, however:

Howard Dean led most national polls of Democrats from October 2003 through January 2004 but flamed out after a poor performance in Iowa. Dean ran an insurgent campaign, but I consider him a borderline case because he did win some backing from party elites, such as Al Gore.Rudy Giuliani led the vast majority of Republican polls throughout 2007 but was doomed by also-ran finishes in Iowa and New Hampshire. Giuliani had a lot of financial backing from the Republican “donor class” but few endorsements from Republican elected officials and held moderate positions out of step with the party platform.So Trump-like candidates — guys who had little party support but nonetheless led national polls, sometimes on the basis of high name recognition — were somewhere between 0-for-6 and 0-for-8 entering this election cycle, depending on how you count Dean and Giuliani. Based on that information, how would you assess Trump’s chances this time around?

This is a tricky question. Trump’s eventual win was unprecedented, but there wasn’t all that much precedent. Bayes’ theorem can potentially provide some help, in the form of what’s known as a uniform prior. A uniform prior works like this: Say we start without any idea at all about the long-term frequency of a certain type of event.10 Then we observe the world for a bit and collect some data. In the case of Trump, we observe that similar candidates have won the nomination zero times in 8 attempts. How do we assess Trump’s probability now?

According to the uniform prior, if an event has occurred x times in n observations, the chance of it occurring the next time around is this:

\(\frac{\displaystyle x+1}{\displaystyle n+2}\)

For example, if you’ve observed that an event has occurred 3 times in 4 chances (75 percent of the time) — say, that’s how often your pizza has been delivered on time from a certain restaurant — the chance of its happening the next time around is 4 out of 6, according to the formula, or 67 percent. Basically, the uniform prior has you hedging a bit toward 50-50 in the cases of low information.11

In the case of Trump, we’d observed an event occurring either zero times out of 6 trials, or zero times out of 8, depending on whether you include Giuliani and Dean. Under a uniform prior, that would make Trump’s chances of winning the nomination either 1 in 8 (12.5 percent) or 1 in 10 (10 percent) — still rather low, but higher than the single-digit probabilities we assigned him last fall.

We’ve gotten pretty abstract. The uniform prior isn’t any sort of magic bullet, and it isn’t always appropriate to apply it. Instead, it’s a conservative assumption that serves as a sanity check. Basically, it’s saying that there wasn’t a ton of data and that if you put Trump’s chances much below 10 percent, you needed to have a pretty good reason for it.

Did we have a good reason? One potentially good one was that there was seemingly sound theoretical evidence, in the form of the book “The Party Decides,” and related political science literature, supporting skepticism of Trump. The book argues that party elites tend to get their way and that parties tend to make fairly rational decisions in who they nominate, balancing factors such as electability against fealty to the party’s agenda. Trump was almost the worst imaginable candidate according to this framework — not very electable, not very loyal to the Republican agenda and opposed by Republican party elites.

There’s also something to be said for the fact that previous Trump-like candidates had not only failed to win their party’s nominations, but also had not come close to doing so. When making forecasts, closeness counts, generally speaking. An NBA team that loses a game by 20 points is much less likely to win the rematch than one that loses on a buzzer-beater.

And in the absence of a large sample of data from past presidential nominations, we can look toward analogous cases. How often have nontraditional candidates been winning Republican down-ballot races, for instance? Here’s a list of insurgent or tea party-backed candidates who beat more established rivals in Republican Senate primaries since 201012 (yes, Rubio had once been a tea party hero):

YEARCANDIDATESTATEYEARCANDIDATESTATE2010Sharron AngleNevada2010Marco RubioFlorida2010Ken BuckColorado2012Todd AkinMissouri2010Mike LeeUtah2012Ted CruzTexas2010Joe MillerAlaska2012Deb FischerNebraska2010Christine O’DonnellDelaware2012Richard MourdockIndiana2010Rand PaulKentuckyWinning insurgent candidates, 2010-14That’s 11 insurgent candidate wins out of 104 Senate primaries during that time period, or about 10 percent. A complication, however, is that there were several candidates competing for the insurgent role in the 2016 presidential primary: Trump, but also Cruz, Ben Carson and Rand Paul. Perhaps they began with a 10 percent chance at the nomination collectively, but it would have been lower for Trump individually.

There were also reasons to be less skeptical of Trump’s chances, however. His candidacy resembled a financial-market bubble in some respects, to the extent there were feedback loops between his standing in the polls and his dominance of media coverage. But it’s notoriously difficult to predict when bubbles burst. Particularly after Trump’s polling lead had persisted for some months — something that wasn’t the case for some of the past Trump-like candidates13 — it became harder to justify still having the polling leader down in the single digits in our forecast; there was too much inherent uncertainty. Basically, my view is that putting Trump’s chances at 2 percent or 5 percent was too low, but having him at (for instance) 10 percent or 15 percent, where we might have wound up if we’d developed a model or thought about the problem more rigorously, would have been entirely appropriate. If you care about that sort of distinction, you’ve come to the right website!

Trump’s nomination is potentially a point in favor of “polls-only” as opposed to “fundamentals” models.In these last two sections, I’ll be more forward-looking. Our initial skepticism of Trump was overconfident, but given what we know now, what should we do differently the next time around?

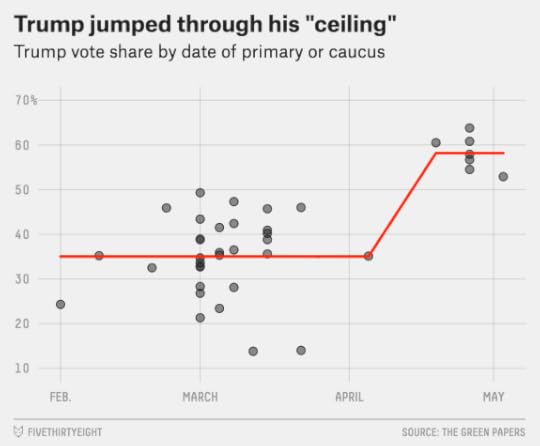

One seeming irony is that for an election that data journalism is accused of having gotten wrong, Trump led in the polls all along, from shortly after the moment he descended the elevator at Trump Tower in June until he wrapped up the nomination in Indiana.14 As I mentioned before, however, polls don’t enjoy any privileged status under the empirical method. The goal is to find out what works based on the historical evidence, and historically polls are considerably more reliable in some circumstances (a week before the general election) than in others (six months before the Iowa caucuses).

Still, Trump’s nomination comes at a time when I’ve had increasing concern about how much value other types of statistical indicators contribute as compared with polls. While in primaries, there’s sometimes a conflict between what the polls say and “The Party Decides” view of the race, in general elections, the battle is between polls and “fundamentals.” These fundamentals usually consist of economic indicators15 and various measures of incumbency.16 (The conflict is pertinent this year: Polls have Clinton ahead of Trump, whereas fundamentals-based models suggest the race should be a toss-up.)

But there are some big problems with fundamentals-based models. Namely, while they backtest well — they can “explain” past election results almost perfectly — they’ve done poorly at predicting elections when the results aren’t known ahead of time. Most of these models expected a landslide win for Al Gore in 2000, for example. Some of them predicted George H.W. Bush would be re-elected in 1992 and that Bob Dole would beat Bill Clinton in 1996. These models did fairly well as a group in 2012, but one prominent model, which previously had a good track record, wrongly predicted a clear win for Romney. Overall, these models have provided little improvement over polls-only forecasts since they regularly began to be published in 1992. A review from Ben Lauderdale and Drew Linzer suggests that the fundamentals probably do contribute some predictive power, but not nearly as much as the models claim.

These results are also interesting in light of the ongoing replication crisis in science, in which results deemed to be highly statistically significant in scientific and academic journals often can’t be duplicated in another experiment. Fundamentals-based forecasts of presidential elections are particularly susceptible to issues such as “p-hacking” and overfitting because of the small sample sizes and the large number of potential variables that might be employed in a model.

Polling-based forecasts suffer from fewer of these problems because they’re less sensitive to how the models are designed. The FiveThirtyEight, RealClearPolitics and Huffington Post Pollster polling averages all use slightly different methods, for example, but they’re usually within a percentage point or two of one another for any given election, and they usually predict the same winner unless the election is very close. By contrast, subtle changes in the choice of “fundamentals” variables can produce radically different forecasts. In 2008, for instance, one fundamentals-based model had Barack Obama projected to win the election by 16 percentage points, while another picked John McCain for a 7-point victory.

Put another way, polling-based models are simpler and less assumption-driven, and simpler models tend to retain more of their predictive power when tested out of sample.

This is a complicated subject, and I don’t want to come across as some sort of anti-fundamentals fundamentalist. Reducing the weight placed on fundamentals isn’t the same as discarding them entirely, and there are methods to guard against overfitting and p-hacking. And certain techniques, especially those that use past voting results, seem to add value even when you have plenty of polling. (For instance, extrapolating from the demographics in previous states to predict the results in future states generally worked well in the Democratic primaries this year, as it had in 2008.) The evidence is concerning enough, however, that we’ll probably publish both “polls-only” and “polls-plus” forecasts for the general election, as we did for the primaries.

There’s a danger in hindsight bias, and in overcorrecting after an unexpected event such as Trump’s nomination.Not so long ago, I wrote an article about the “hubris of experts” in dismissing an unconventional Republican candidate’s chances of becoming the nominee. The candidate, a successful businessman who had become a hero of the tea party movement, was given almost no chance of winning the nomination despite leading in national polls.

The candidate was a fairly heavy underdog, my article conceded, but there weren’t a lot of precedents, and we just didn’t have enough data to rule anything out. “Experts have a poor understanding of uncertainty,” I wrote. “Usually, this manifests itself in the form of overconfidence.” That was particularly true given that they were “coming to their conclusions without any statistical model,” I said.

The candidate, as you may have guessed, was not Trump but Herman Cain. Three days after that post went up in October 2011, accusations of sexual harassment against Cain would surface. About a month later, he’d suspend his campaign. The conventional wisdom would prevail; Cain’s polling lead had been a mirage.

Listen to the latest episode of the FiveThirtyEight elections podcast.

https://serve.castfire.com/s:5L8r1/audio/2754984/fivethirtyeightelections_2016-05-16-183724.64k.mp3?ad_params=zones%3DPreroll%2CPreroll2%2CMidroll%2CMidroll2%2CMidroll3%2CMidroll4%2CMidroll5%2CMidroll6%2CPostroll%2CPostroll2%7Cstation_id%3D4278Subscribe: iTunes |Download |RSS |VideoWhen Trump came around, I’d turn out to be the overconfident expert, making pretty much exactly the mistakes I’d accused my critics of four years earlier. I did have at least a little bit more information at my disposal: the precedents set by Cain and Gingrich. Still, I may have overlearned the lessons of 2012. The combination of hindsight bias and recency bias can be dangerous. If we make a mistake — buying into those polls that showed Cain or Gingrich ahead, for instance — we feel chastened, and we’ll make doubly sure not to make the same mistake again. But we can overcompensate and make a mistake in the opposite direction: For instance, placing too little emphasis on national polls in 2016 because 2012 “proved” they didn’t mean anything.

There are lots of examples like this in the political world. In advance of the 2014 midterms, a lot of observers were convinced that the polls would be biased against Democrats because Democrats had beaten their polls in 2012. We pointed out that the bias could just as easily run in the opposite direction. That’s exactly what happened. Republicans beat their polls in almost every competitive Senate and gubernatorial race, picking up a couple of seats that they weren’t expected to get.

So when the next Trump-like candidate comes along in 2020 or 2024, might the conventional wisdom overcompensate and overrate his chances? It’s possible Trump will change the Republican Party so much that GOP nominations won’t be the same again. But it might also be that he hasn’t shifted the underlying odds that much. Perhaps once in every 10 tries or so, a party finds a way to royally screw up a nomination process by picking a Trump, a George McGovern or a Barry Goldwater. It may avoid making the same mistake twice — the Republican Party’s immune system will be on high alert against future Trumps — only to create an opening for a candidate who finds a novel strategy that no one is prepared for.

Cases like these are why you should be wary about claims that journalists (data-driven or otherwise) ought to have known better. Very often, it’s hindsight bias, sometimes mixed with cherry-picking17 and — since a lot of people got Trump wrong — occasionally a pinch of hypocrisy.18

Still, it’s probably helpful to have a case like Trump in our collective memories. It’s a reminder that we live in an uncertain world and that both rigor and humility are needed when trying to make sense of it.

May 17, 2016

Is Sanders Hurting Clinton By Staying In The Race?

In this week’s politics chat, we consider Bernie Sanders, his present and future. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah: It’s been awhile since we really dived into the Democratic nominating contest, so let’s explore Bernie’s world. We’ll cover a couple of topics: Is Sanders hurting Hillary Clinton’s chances in the general election? What does Sanders’s success mean for the future of the Democratic Party? But let’s start with this: What is Sanders doing? Why is he still in the race? What does he want?

harry: Sanders is still in the race for several reasons. First, it’s difficult to leave a presidential race when you’re still winning contests and you’ve been running for over a year. Second, there are still a big chunk of Democrats (45 percent) who think Sanders should stay in the race until the convention. Third, he wants to continue pushing his progressive agenda. There are other reasons, but that’s a start.

clare.malone: “Bernie’s world” sounds like a PBS children’s show about a bear named Bernie.

micah: It was a play on “Wayne’s World.”

natesilver: Sanders has had several opportunities to exit the race, though. In particular, after winning only Rhode Island on April 26 and losing Pennsylvania, Maryland, etc. Or when he got shut out on March 15.

clare.malone: Yikes to that survey Harry just noted, by YouGov, which found that one-third of Democratic voters have an unfavorable view of Clinton, and her unfavorables have jumped of late. Is this where the political revolution curdles?

By way of personal anecdote, my downstairs neighbors put a “Bernie or Bust”-type sign in their window only about a week ago. People are taking the Sanders campaign’s cues of frustration

natesilver: Clinton’s 33 percent unfavorable rating in the YouGov poll is on the high end compared with other surveys, although the methodology matters here. That 33 percent number is among what YouGov calls “likely Democratic primary voters,” which includes both Democrats and independents who vote in the Democratic primaries. Among voters who identify as Democrats, her unfavorability rating is just 16 percent, according to the same poll. So it’s the Sanders-voting independents who are really dragging her numbers down, a group that’s quite liberal but doesn’t affiliate itself with the Democratic Party.

harry: One thing that I think gets undersold is the psychology of coming so far when so few people thought you would come so far. Most people, including me, thought Sanders would win some votes but that Clinton would ultimately crush him. And while she holds a significant lead, Sanders won more than 40 percent of the Democratic primary vote. When the same analysts who thought you didn’t have much of a chance now say you’re dead in the water, there is an understandable tendency to dismiss them. The problem: The analysts are right in this case. And that some in the Sanders campaign are so forcefully arguing that he is losing because the game is fixed could make it difficult for Clinton to coalesce the Democratic vote.

clare.malone: I think you’re right, Harry, that there’s something psychologically different roiling in the Democratic electorate this year — a number of former volunteers and staff from Sanders’s campaign have proposed a post-dropout plan that has the Sanders money machine and organization being directed toward an enterprise separate from the Clinton campaign. Granted, it’ll be devoted to defeating Trump, but this is a far cry from one big happy Democratic family. It’s also important to note that the Sanders campaign said the plan is “totally irrelevant,” to their decision-making.

natesilver: Now I’m really going to get myself in trouble: Weren’t the experts correct that Sanders didn’t have much of a chance?

micah: I’m with Nate on this: Sanders did get crushed — this is what crushed looks like in a proportional primary system. If the Democratic race were run with GOP rules, that would be more apparent.

harry: Oh, I don’t agree with that at all. Sanders is trailing Clinton in the popular vote by about the same as Cruz is trailing Trump.

micah: And Cruz got crushed.

natesilver: To me, it’s like when a college football team — Clinton University — is favored by 24 points. Their opponent, Sanders State, kicks a field goal to go ahead 3-0. But then Clinton U. pulls ahead 14-3 on Super Tuesday and leads the rest of the way. Sanders State never makes it a one-score game, and in the end, Clinton U. wins by 14. So Sanders State beat the point spread, but you wouldn’t really call it a close game — Clinton U. was in control almost the whole way.

micah: Let me focus the conversation for a minute on a more specific question: What does Bernie want? Is his sole goal to win? To shape the Democratic platform? To change the rules governing future primary campaigns?

clare.malone: I’d say shaping the platform is probably the biggest one, and who knows, he might take up the Lawrence Lessig mantle of campaign finance reform post-election.

natesilver: I’m not sure he knows what he wants.

clare.malone: I mean, he’s an ideologue, so the party-platform-influencing seems a given in terms of what Bernie wants; he’s aiming, perhaps, to be the permanent countervailing force in Democratic politics. The eternal bur stuck on the party’s lovely cashmere sweater.

natesilver: He’s caught in the middle of the campaign, it’s sort of fun and exhilarating, he has tens of millions of admirers, he has a staff that’s telling him to hang on, and he’s winning a state or two every couple of weeks. He may not have a long-term game plan — he may just be living in the moment.

clare.malone: Instead of retiring and going fishing, run a presidential campaign! It’s the Boomer plan of 2016, all around.

Harry: I think both Clare and Nate are right. Sanders entered this campaign with the hope of driving the policy debate. He ends up winning a bunch of states, and then it’s like “holy heck, I can win this thing!” That led, I think, to a slightly more negative campaign than I would have expected from a candidate in it more for the policy discussion than to win.

clare.malone: Most likely, the campaign itself is parsing through a lot of these questions right now. They’re definitely in a soul-searching period, and we’ve seen that play out live on primary night cable, when one Sanders surrogate is saying one thing about the campaign’s plans and another surrogate is saying another.

natesilver: It’s also important to keep in mind that although Sanders is a proud progressive, he isn’t a loyal Democratic Party soldier.

micah: So is he hurting Clinton?

clare.malone: Yes, I’d say so.

micah: How so?

clare.malone: In the sense that time heals all wounds — the Clintons would like to have more time for people to forget how much they love Bernie and focus on the pragmatic battle ahead.

natesilver: Agreed. In the general election polls since Indiana, we’re seeing more Republican voters rally behind Trump, but Clinton hasn’t gotten a post-nomination bounce yet. So the polls right now are sort of a test of what might happen if the Sanders voters don’t rally behind Clinton. And the answer is that it makes it a closer election — Clinton’s still ahead, but it’s close enough that if something goes wrong (a recession, for instance), you could have President Trump.

harry: Sanders isn’t helping Clinton, but I’m not sure how much he is hurting her. In many polls, Clinton is already getting a good chunk of the Democratic vote, and you’ll likely see some type of bounce once Sanders exits (depending on whether he endorses and what that endorsement looks like). Trump was getting a lower percentage of the Republican vote before wrapping up the nomination, so I’m not sure we’ll see Clinton get as large of a bounce as Trump has gotten, but there will be some coalescing.

natesilver: The SurveyMonkey poll you just linked to, Harry, is something of an exception, but I’d also note that the number of undecided voters in most of the Clinton-Trump matchup is unusually high. You’re seeing some results like Clinton 43 percent, Trump 40 percent, for instance. That suggests there are a lot of base voters who have yet to be activated. And they won’t necessarily cross parties to vote, but they might sit out, or vote for Gary Johnson or Jill Stein.

clare.malone: Gotta activate the Democratic base storm troopers. The Gary Johnson thing is interesting — I’m not sure how much a typically Democratic-leaning independent voter will go for him, though.

natesilver: Johnson is sort of a capital-L libertarian, instead of a Rand Paul conservative libertarian. I think some Sanders supporters could groove to him on social policy even though they might find his economics pretty detestable.

Harry: Some quick math: The HuffPost Pollster aggregate has the combined vote for Clinton and Trump in the low 80s. In the previous three presidential election cycles — using the Pollster.com aggregate for 2012 and 2008 and the RealClearPolitics average for 2004 — the two-party vote combined to around 90 percent at this point. Something is clearly going on.

natesilver: Let me be clear, though: Clinton’s support among Democrats is average, or maybe even a little above average. It’s not a crisis for her. It’s just that she ought to have an opportunity to have near-universal support from Democrats, along the lines of what Obama had, in an election against Trump. If she gets that Democratic turnout, it probably isn’t an especially close election against Trump, and Democrats have a lot of opportunities to pick up seats in down-ballot races. If she doesn’t, then who knows.

micah: So will Sanders voters eventually go to Clinton? [Editor’s note: Nate commanded me, offline, to ask this question.]

harry: Question: Does Sanders endorse Clinton?

natesilver: Some or most of them probably will. But there’s one thing that would worry me a bit, if I were Clinton. Namely, it’s the sense you get from Sanders supporters that the system is rigged against them. You saw that on display at the Nevada convention this weekend, for instance, where things got pretty nasty, and Sanders hasn’t really done much to repudiate his supporters.

New: When asked about Nevada Dem convention today, Bernie Sanders walked away mid-Q, @DannyEFreeman reports.

— Alex Seitz-Wald (@aseitzwald) May 17, 2016

micah: IDK, we heard a lot about this kind of stuff in 2008, about how Clinton supporters wouldn’t rally behind Obama. That didn’t turn out to be a problem.

harry: Clinton endorsed Obama pretty much immediately after losing.

natesilver: I guess what I’m saying is that I wonder if the system-is-rigged argument could be harder to repair than other sorts of grievances.

clare.malone: Yeah, and it’s more interesting here because Clinton was obviously going to fall into the party line. Sanders is definitely more of a wild card in terms of how he wants to spin things after he drops out. The revolution is televised, after all!

natesilver: If you think someone isn’t arguing in good faith, they have a lot of work to do to regain your trust.

clare.malone: He could get tons of media play post-dropout if he wanted to take on a certain issue and really make it a part of the general election convo — maybe he does go after reforming the nominating system.

natesilver: It’s also interesting to me how, when you see comments from Sanders supporters online or at rallies, etc., they’re quick to frame things in terms of people being biased, being sellouts, etc. All candidates’ supporters are annoying in their own way, but it’s a different vibe than what you usually get.

clare.malone: Sour grapes-y.

harry: The idea that you are always being unfair.

micah: All right, that flows nicely into our last topic for considering: Bernie’s legacy. I do think he could play some role in reforming the primary system. Or pushing the Democratic platform to the left? More generally, also, what can we learn from the Sanders campaign about the state of the Democratic Party?

clare.malone: It’s funny because I think if his campaign hadn’t taken off, Sanders would have continued to labor in relative obscurity in the Senate for years and years talking about worthy things like dental care for Appalachian kids (I’m recalling the press releases I used to get, about four years back, from his office). So, in some ways, I could see him going back to legislating and just enjoying a more high-profile platform for his issues.

natesilver: The guy has a lot of power, though. He’s the third-most-influential Democrat/liberal in the country, following President Obama and Clinton. And you have a big vacuum between the top 3 and everyone else.

harry: Even more powerful than Martin O’Malley?!

micah: To answer my own question: I think one of the main lessons of the Sanders campaign is that the Democratic elite have an outsider/insider problem too. Maybe it’s not as dire as the GOP’s, but it’s there.

clare.malone: Sanders might have been bitten by the wild tsetse fly of political campaigns, and he feels much more empowered — maybe it’s primary reform, maybe it’s money in politics.

micah: ADDRESS MY OUTSIDER/INSIDER POINT!

natesilver: To me, the outsider/insider framing is somewhat vapid.

harry: Yeah, pure garbage.

natesilver: I don’t really know what it means.

clare.malone: Explain insider/outsider. EXPLAIN YOURSELF!

(micah is typing)

(micah is still typing)

(it’s actually only been a minute)

(but that feels like forever in Slack)

micah: OK, part of the GOP’s problem is that the establishment no longer holds much sway with Republican voters. Just the opposite, actually: Hitting the elites is a plus. To me, here’s one of the main questions about the Sanders campaign: Is his success, such as it is, simply what you get with a liberal challenge in a two-party race? Or is there a sizable bloc of Democratic voters, young voters in particular, who are sick of standard Democratic politics — who feel the system is rigged, to get back to the point we were talking about earlier. If it’s the latter, then I think that potentially poses long-term problems for the Democratic Party. It increases the chances that the Democrats, at some point, get a nominee unacceptable to the party elites, like the GOP got this year.

natesilver: I guess there are two ways to read Sanders, and I’m somewhat conflicted between the two.

The more cynical interpretation, I suppose, is that Sanders is sort of an unlikely pop culture phenomenon, by virtue of being a lovable, grandpa-ish underdog. If that’s the case, we might not want to read as deeply into what he means for the Democratic Party. There was an opening for an alternative to Clinton, and Sanders happened to be the best guy to step into it.

The second interpretation is that the Democratic consensus/coalition associated with the Clintons and Obama is fraying. In particular, the consensus around neo-liberal economic policies. A lot of the differences between Clinton and Sanders are over the efficacy of free markets.

micah: OK, I’m not sure I agree with that. Clinton is pretty liberal, including on economic policy. Their differences there seem to me to be 80 percent tone and 20 percent policy.

natesilver: It’s certainly true that they don’t have that many policy differences, at least on the surface. They voted together 93 percent of the time when in Congress together.

But I think they come to those conclusions from different places. Clinton basically believes in capitalism but thinks it needs some regulation. Sanders is more of a leftist, as opposed to a liberal.

clare.malone: I think that it’s not so much that Democratic voters are fed up with the party’s policies overall — Obama’s health care reform is looked on fondly by a vast majority of them — but I do think there is a sense that Democrats need to repackage and spin their politics to look like the “party of the people.” Mostly, I think, a lot of people don’t like the idea of another Clinton in office, plain and simple — it feels a little wrong from a small-d democratic point of view. Dynastic vibes are not very popular in the age of “The Big Short”; we’re at a moment when the culture is filled with warnings against institutions and insiders and when everyone feels like Ivy League toffs are pulling something over on them. The Clintons sort of unarguably fit into this elite rubric, and I think that makes a lot of Democratic voters uneasy.

micah: To me, the biggest difference — and again this has echoes of what’s going on in the GOP — is in faith in government. Sanders and his supporters are more willing to blow stuff up. Clinton is a tinkerer.

harry: The question is how durable the age split in the 2016 Democratic primaries is. Take a state like Ohio; Clinton won 77 percent of voters 65 and older, while Sanders took 85 percent of the 18- to 29-year-old vote. Does the progressive youth of today translate into the progressive majority of tomorrow? We don’t know the answer to that question yet.

Listen to the latest episode of the FiveThirtyEight elections podcast.

https://serve.castfire.com/s:5L8r1/audio/2754984/fivethirtyeightelections_2016-05-16-183724.64k.mp3?ad_params=zones%3DPreroll%2CPreroll2%2CMidroll%2CMidroll2%2CMidroll3%2CMidroll4%2CMidroll5%2CMidroll6%2CPostroll%2CPostroll2%7Cstation_id%3D4278Subscribe: iTunes |Download |RSS |Videomicah: Final thoughts!

Harry: That’s what is so interesting to me. It’s really an age split that has run through this Democratic primary, as opposed to ideological rift. Clinton regularly wins — or comes close to winning — “very liberal” voters. It’s among young voters that she fails. I wonder how much of the Sanders allure is about being an outsider, as opposed to being very progressive.

micah: Score:

Micah — 1

Nate — 0

natesilver: One problem is that Sanders is an old guy. And so are a lot of the other progressives that leftist Democrats might look up to, like Elizabeth Warren. If I were Sanders, one thing I’d be thinking about is creating an organization that supports progressive Democrats in primaries in state elections. Sanders hasn’t done much of that so far. He didn’t endorse Donna Edwards in Maryland or John Fetterman in Pennsylvania, for instance.

micah: Someone put a bow on this.

Harry: I guess this question remains unanswered: Is Sanders a one man in one time phenomenon, or is he the dawning of a new progressive Democratic generation? Sanders’s actions after this campaign can go a long way toward determining that.

clare.malone: Yeah — WHERE ARE THE DEMOCRATIC YOUTH?? There are very few young stars in the Democratic Party with real name recognition. Is the Sanders campaign the factory farm for stars/strategists to come? Maybe. But it seems problematic to me that the progressive rock stars of the Democratic Party are in their 60s/70s.

natesilver: Let’s not get ahead of ourselves. We still have 2016 to figure out. I think Sanders supporters will probably line up behind Clinton after California and that Democrats will wind up with high levels of party unity. But I’m not quite as sure about that as I was a month or so ago.

May 16, 2016

Elections Podcast: Should Congressional Republicans Be Worried About Trump?

Will Donald Trump help or hurt other Republicans up for election this fall? FiveThirtyEight contributor David Wasserman joins the elections podcast to look at whether GOP majorities in the Senate and House are in danger. Then the team tackles the notion that Trump supporters have been reluctant to share their preferences with pollsters, skewing the polls against him. Plus, as scrutiny of North Carolina’s transgender bathroom bill grows, the crew discusses the role that social issues play in how people vote.

https://serve.castfire.com/s:5L8r1/audio/2754984/fivethirtyeightelections_2016-05-16-183724.64k.mp3?ad_params=zones%3DPreroll%2CPreroll2%2CMidroll%2CMidroll2%2CMidroll3%2CMidroll4%2CMidroll5%2CMidroll6%2CPostroll%2CPostroll2%7Cstation_id%3D4278Subscribe: iTunes |Download |RSS |VideoYou can stream or download the full episode above. You can also find us by searching “fivethirtyeight” in your favorite podcast app, or subscribe using the RSS feed. Check out all our other shows.

If you’re a fan of the elections podcast, leave us a rating and review on iTunes, which helps other people discover the show. Have a comment, want to suggest something for “good polling vs. bad polling” or want to ask a question? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

May 11, 2016

Could An Independent Candidate Succeed In 2016?

In this week’s politics Slack chat, we weigh the chances of a viable independent presidential candidate. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): We have a guilty-pleasure topic today: an independent presidential bid. A lot of people have been talking up the idea, and we’ll get into whether an independent run is logistically feasible and who would make a good independent candidate. But first, let’s dive into why people are so taken with the notion of a truly viable independent candidate. Is there something about the current political climate or modern politics generally that makes a successful independent bid more likely? (Define “successful” loosely.)

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Allow me to reel off a few reasons:

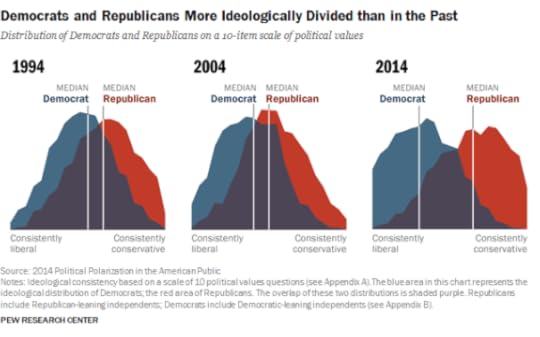

Most Americans think the country is on the wrong track. If you look back at the last big third-party bid, in 1992, you see similar right direction/wrong track numbers.Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, the two presumptive nominees, are extremely disliked. That’s somewhat similar to 1992, with the first George Bush and Bill Clinton, and to a lesser extent with Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan in 1980.We have a major ideological split within the Republican Party. This reminds me of 1980, when some more liberal Republicans were unhappy with Reagan — the most conservative Republican nominee since 1964 and, IMO, probably the second most conservative nominee since Herbert Hoover in 1932. Reagan was also anti-abortion, which John Anderson, a Republican who ran as an independent in 1980, was not. You also saw major-party splits that presaged George Wallace’s independent run in 1968 and Strom Thurmond’s in 1948.A feeling that both candidates are the same. That is, the real need for an outsider. Now, this is interesting because Trump is kind of a third-party candidate within the Republican Party. But since some traditional Republicans feel displaced, they may get behind a third-party candidate. The idea that both candidates are the same was also in the air when Ralph Nader ran in 2000, and to some degree when Thurmond and Henry Wallace ran in 1948.natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): I feel like you’re missing No. 5 (although it somewhat contradicts No. 4): The degree of partisanship is higher than ever. In the abstract, if the parties are pulling farther and farther apart, eventually the rubber band snaps and some voters in the middle are left behind.

micah: For instance, from Pew Research:

farai (Farai Chideya, senior writer): Harry, 1948 was an interesting year because you had two different third-party candidacies. There was Henry Wallace, whose voters largely defected to Harry Truman in the late stages of the race, helping Truman win. But there was also Strom Thurmond. Both got 2.4 percent of the popular vote, but only Thurmond got electoral votes. Independent candidates who have a broad base of support spread evenly across the nation can have less of an effect on the Electoral College than regional candidates.

harry: And then you get someone like Ross Perot, who got nearly 20 percent of the national vote in 1992 and received 0 electoral votes.

farai: I mean, in some ways Trump is a bit of a Trojan horse — an independent who happens to be using the GOP as the equivalent of a shell corporation.

micah: Yeah, that seems right to me. And some of the factors Harry identified also help to explain Trump’s success.

OK, so do we believe this year is really more ripe for a third-party bid? Or is Farai right that Trump is basically an independent running on the GOP line? (I think Farai is right.)

harry: To me, this year pretty much meets all the criteria for at least a moderately successful third-party candidacy. That doesn’t mean it will happen, of course. A truly strong independent bid would have been more likely if Bernie Sanders were winning the Democratic nomination, because then Michael Bloomberg would have likely run.

natesilver: Sometimes I’ll be having a perfectly nice conversation with somebody and they’ll be like “So, what are Mike Bloomberg’s chances of becoming president?” His set of attitudes and policy positions are overrepresented among cultural and political elites, so the media tends to overstate how viable he might be. In some ways, Trump is a much better fit for independent voters. From an article I wrote in January:

micah: In a Trump vs. Clinton general election, wouldn’t the most logical independent candidate or third-party candidate look like — dare I speak his name — Ted Cruz? [Editor’s note: Right after we finished this chat, Cruz told reporters in Washington that he had “no interest” in a third-party bid.]

harry: Just to be clear, we already have a bunch of third parties running: candidates from the Green Party and Libertarian Party, for example. Don’t be surprised if Gary Johnson (if he becomes the nominee) gets a higher percentage of the vote than the Libertarian candidate typically does.

natesilver: Yeah, there’s some question about what a token-ish #NeverTrump independent candidate would get you that Gary Johnson wouldn’t. Libertarians already have ballot access in 30-something states.

micah: So you think it makes more sense for #NeverTrump to rally with Johnson rather than run a movement conservative like #PaulRyan?

natesilver: Can you get a movement conservative as Johnson’s VP? Libertarians haven’t held their convention yet. Obviously, it’s different if you have a Mitt Romney run, or something.

micah: Rubio.

harry: The dream shall never die.

natesilver: RU-BEE-OH! RU-BEE-OH!

micah: Really, though — none of this is going to happen, but in terms of the political space left unfilled in a Trump vs. Clinton election, I think Romney < Rubio < Cruz (Nate’s Rubio adoration notwithstanding). But I’m not sure whether #NeverTrump should go with Johnson or a Cruz-like candidate — what’s more effective if your goal is stopping Trump?

natesilver: I’m just saying that you have to consider Johnson in your VORC (value over replacement candidate) calculation. If the alternative is some backbench U.S. representative or something, he’s not going to get very many votes that Johnson wouldn’t, you might not have a lot of enthusiasm for petitions to get him on the ballot, and the efforts might be better spent getting Libertarians on the ballot in more states. If it’s Romney or someone with a national profile, that’s way different.

harry: Johnson got 1 percent of the vote in 2012 without much of a yearning for an outsider.

farai: When you have third-party and independent candidates, there’s a vast difference between voters who make judgments purely based on platforms/ideas and ones who do viability math. Some possible Ralph Nader voters in 2000 abandoned his candidacy when they felt it might jeopardize the Democratic Party’s chances; same with Henry Wallace, the Progressive, in 1948. So, circling back to what Harry said about there being lots of third parties already, the issues-based voters may have already aligned with the third parties, but the two-party system makes picking a third party extremely difficult for people who care about viability and likelihood of winning. That’s very different from multiparty democracies in much of the world, and their coalition governments.

harry: Well, there are multiple reasons third/independent candidacies fail in the U.S. One of those is our first-past-the-post or plurality voting system.

natesilver: What’s different this year is that there are some voters, especially movement conservative Republicans, who really might consider their cause better off if Trump loses than if he wins, but who also get a chill in their spine at the thought of having to vote for Clinton. It’s not a large share of the population. It might be 2 or 3 percent or something. But that could make a difference if the election tightens.

farai: Nate, do you think anyone who that demographic would vote for could actually mount a campaign this late in the game?

natesilver: It’s hard to guess. If Trump had wrapped up the nomination one month sooner, it would have been more likely. If he hadn’t wrapped it up until June, it would have been less likely. We’re on the precipice, and my hunch is that it ultimately won’t pan out, but I really have no idea.

micah: So we talked a bit about the current conditions that are favorable to an independent bid. What’s working against such a run?

harry: Money, for one. It takes a lot of money to run for president. President Obama spent over $700 million in 2012, and Romney spent about $450 million.

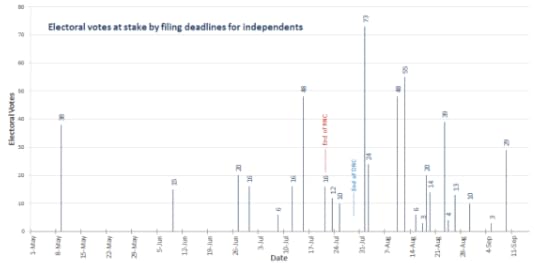

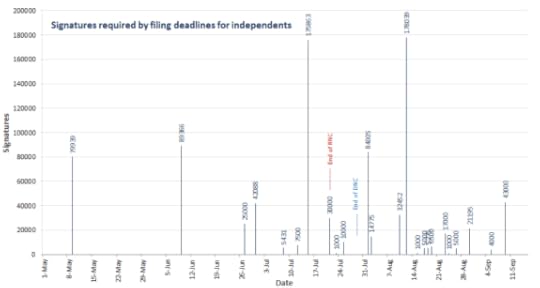

farai: Here are some charts from the Brookings Institution that show the filing deadlines to get on the ballot in each state, and what’s required in each.

It’s hard to imagine who can mount a run with the time we have left. Someone like Bloomberg who’s extremely wealthy could probably assemble a viable machine, but the sheer mechanics of running a campaign are just daunting.

natesilver: Yeah, the filing deadline in Texas has already passed, and you’d have to sue to try to get ballot access. Other deadlines are coming up pretty soon. But mainly … such a bid is quite unlikely to be successful.

farai: Exactly. Most voters are pragmatic about the choices offered and base their vote, at least in part, on a candidate’s chance of winning.

micah: So besides the logistical stuff, isn’t it true that voters just aren’t that into it?

natesilver: Not exactly. It also has to do with the dynamics of the Electoral College and winner-take-all elections.

farai: It’s always worth remembering we have one version of democracy, even of American democracy. We’d be different if fusion voting were national, as it was in the past. And certainly if we had multiparty democracy, we’d see a broader range of political parties.

But the workings of the Electoral College are everything in the end, and a third-party candidate winning any electoral votes has tended to mean having a successful hyper-regional campaign. So from 1940 until today, the only two third-party candidates to win electoral votes were segregationists Strom Thurmond (1948) and George Wallace (1968). Thurmond won about 2.4 percent of the popular vote and 39 electoral votes, and Wallace won 13.5 percent of the popular vote and 46 electoral votes.

natesilver: Unless a third-party candidate is drawing exactly evenly from the two party bases, he tends to be a spoiler. Say the election starts out Clinton 52 percent, Trump 48 percent. A third-party candidate takes 10 percent from Trump and 5 percent from Clinton. That winds up being Clinton 47, Trump 38, third party 15, which will look like a Clinton landslide.

But even if the third-party candidate gets 35 percent of the vote or something, they’ll tend to finish second in a lot of places — second behind Clinton in blue states, and second behind Trump in red states.

harry: That is, as Farai said, unless they are a regional candidate. That’s why Thurmond and George Wallace were bigger players — at least in terms of the electoral college — than say Anderson and Henry Wallace.

But how about this question: Who were the voters most opposed to Trump in the Republican primary? Very conservative voters and well-educated moderates. What type of candidate would appeal to those constituencies? And could that person possibly reach out to the #bernieorbust folks as well?

natesilver: Harry, that’s part of why I’m saying Gary Johnson could do relatively well, unless you have someone else with real star power. The well-educated moderates will vote for Johnson, and a few Bernie types might. Not sure the religious conservatives would, but he’s at least there as a relatively harmless protest vote.

micah: OK, let’s wrap this up — anything else we want to cover?

harry: One thing to watch out for is the cumulative share of the vote earned by third-party candidates. It could be that Johnson takes 4 percent, Jill Stein gets 1 percent, the Constitution Party gets 0.3 percent, etc. That is, the third-party candidates get more support than usual, but it’s spread over a few different candidates.

natesilver: You could also have some undervoting — people who skip the presidential race and just vote for Senate, etc., instead. This gets a little tricky from a polling standpoint and may be one reason we see differences in the polls later this year. Pollsters tend to “push” voters pretty hard toward picking one of the major-party choices. If an above-average number will vote third party, or undervote, or write someone in, or just stay home, that pushing might not be a good idea.

farai: Also, any parties that get 5 percent in a presidential election then get federal matching funds in the next election. So if Johnson could break that threshold for the Libertarians, that could greatly improve their chances in the future.

harry: That’s true. Although the Reform Party getting federal funding (as a result of Perot’s 8 percent showing in 1996) didn’t exactly help Pat Buchanan in 2000.

May 9, 2016

Elections Podcast: Paul Ryan Isn’t Happy

FiveThirtyEight’s elections podcast team reflects on why the media and this podcast underestimated Donald Trump’s appeal in the Republican primary. And after Trump spent his first week as presumptive nominee sparring with House Speaker Paul Ryan, they discuss GOP unity, which appears more elusive than ever. Plus, what a presidential race would look like between two exceptionally disliked candidates.

https://serve.castfire.com/s:5L8r1/audio/2748719/fivethirtyeightelections_2016-05-09-184419.64k.mp3?ad_params=zones%3DPreroll%2CPreroll2%2CMidroll%2CMidroll2%2CMidroll3%2CMidroll4%2CMidroll5%2CMidroll6%2CPostroll%2CPostroll2%7Cstation_id%3D4278Subscribe: iTunes |Download |RSS |VideoYou can stream or download the full episode above. You can also find us by searching “fivethirtyeight” in your favorite podcast app, or subscribe using the RSS feed. Check out all our other shows.

If you’re a fan of the elections podcast, leave us a rating and review on iTunes, which helps other people discover the show. Have a comment, want to suggest something for “good polling vs. bad polling” or want to ask a question? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

May 6, 2016

Is It Paul Ryan’s Party Or Donald Trump’s Party?

In a special “emergency” politics Slack chat, we marvel at — and consider the implications of — House Speaker Paul Ryan’s non-endorsement of Donald Trump. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): Not two days after he took the reins of the Republican Party, Trump has gotten into it with the Republican speaker of the House, Ryan, one of the few GOP leaders with enough stature and credibility to rhetorically arm wrestle with the GOP’s presumptive nominee. To be fair, Ryan started it, going on CNN and saying about backing Trump, “I’m just not ready to do that at this point. I’m not there right now.”

Another few choice quotes:

“I think what a lot of Republicans want to see is that we have a standard-bearer that bears our standards.”“I think conservatives want to know, does he share our values and our principles on limited government, the proper role of the executive, adherence to the Constitution?”“There are lots of questions that conservatives, I think, are going to want answers to, myself included. I want to be a part of this unifying process. I want to help to unify this party.”So, is this the first crack in the foundation of the Republican Party? Is it a minor disagreement that’ll get patched up? Is Ryan just trying to maintain some leverage over Trump to keep him — at least a little — in line?

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): We should also include the Trump response, since he was basically counter-punching, as he is wont to do:

I am not ready to support Speaker Ryan’s agenda. Perhaps in the future we can work together and come to an agreement about what is best for the American people. They have been treated so badly for so long that it is about time for politicians to put them first!

julia.azari (Julia Azari, associate political science professor at Marquette University and FiveThirtyEight contributor): There are two fault lines here: One between Trump and Ryan/Mitt Romney/the Bushes/etc.; and one between that latter group and the established party leaders who are supporting and going to support Trump (Mike Pence, perhaps the Republican National Committee), even though they weren’t part of his movement initially.

These have different implications. A party at odds with its nominee can be at least partly written off as an organizational failure. A party at odds over its nominee has got bigger problems.

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Honestly, I don’t know the answer to your question, Micah. But there are a number of Republicans who feel the way Ryan does. Not the majority of them, but some of them. Lots of polls show some straggling Republicans in getting aboard the S.S. Trump. In the latest CNN poll, for example, Trump gets the support of only 83 percent of respondents who lean Republican. Clinton gets 91 percent of Democrats and Democratic-leaners.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Stepping back here, consider how unusual it is for a party nominee to be opposed by any major figure within his or her party.

micah: Well … it’s freaking crazy. Has it happened before?

natesilver: When Georgia Senator Zell Miller opposed John Kerry in 2004, it was considered a pretty big deal. And Miller was a Democrat-in-name-only who had a voting record like a typical Republican.

This time, the freaking speaker of the House isn’t able to endorse the nominee. So to some extent, it will be interesting to see whether (say) 70 percent or 80 percent or 90 percent of Republican party elites eventually get behind Trump. But since the usual benchmark is 99 percent or 100 percent, it’s a big story either way.

clare.malone: I think this is a smart move by Ryan, and one he can point back to when he eventually runs for president — he’s probably going to end up supporting Trump, but he can say to people in four years, “look, I was being thoughtful/skeptical about the direction Trump was leading our party.”

julia.azari: This goes back to the piece I wrote a couple months ago about party splits: When people grumbled or even opposed, say, William Howard Taft in 1912 or Hubert Humphrey in 1968, it was because there was a clear divide in the party over something — in both those cases, that party controlled the presidency and nothing splits a party like having to respond to its own ideas in practice. This is really, really Trump-focused.

Also, if you all will indulge me in a little 19th century party history: Supporting the presidential nominee was the essence of what it meant to be a political party back then. You could deviate from the party on policy (true in both parties) in order to please your local constituents, but you had to support the nominee if you wanted to stay in the party. Now it’s kinda the opposite in the Republican Party.

harry: I think Julia makes a really interesting point. I wonder though is it Trump-focused as much as it is what Trump stands for? How many people are merely opposed to what they see as heated rhetoric versus his stance on say taxes, as you could argue Ryan is?

micah: Harry, we’ll get to that in one second, but first: Is it possible the Republican Party basically splits into two groups, both still called the Republican Party, and one runs for president and one cares about Congress, and the two don’t really talk that much or support each other?

julia.azari: I’ve been thinking about this a lot, especially since the tea party, which paved the way for Trump in some ways, is a Congress-focused movement. It never gained traction in presidential politics.

The electoral map supports this. Challenging someone in a primary is way easier to do to members of Congress. And Republicans control some, you know, really red districts as well as some light red ones. But the presidential map is a much bigger challenge since urban areas dominate states like Illinois, Pennsylvania and New York.

harry: Of course, wasn’t the tea party thought of as mostly a conservative movement?

clare.malone: The Freedom Caucus in Congress is an interesting thing to look at when we’re talking about party fission.

julia.azari: Yeah. So tea party supporters look like Trump supporters in their racial/ethnic attitudes but not in their social issue attitudes or opinion of, say, Obamacare. But I think the structural connection is key there. The Freedom Caucus loosened up the party and made it acceptable and normal to challenge established figures. Trump followed their lead.

micah: Is the Freedom Caucus in Ryan’s camp? Trump’s camp? Neither?

julia.azari: I bet they will split.

clare.malone: They have been intransigent party members for years. … I’m not quite sure people have the stomach right now to up and create a whole new party, but it seems pretty unsustainable to simply bicker endlessly without wounding yourself pretty badly in the future (also, that’s maybe already happened). I think the Freedom Caucus doesn’t have a camp yet … but I’d be willing to bet they’ll get down with Trump, Micah.

micah: Interesting … so that brings us to policy, which seemed to be Ryan’s chief concern, i.e. “I think conservatives want to know, does he share our values and our principles on limited government, the proper role of the executive, adherence to the Constitution?”

But as Washington Post reporter Philip Rucker pointed out, do GOP voters even care about that crap anymore?

He also beat 16 people who more closely align w/ Ryan agenda, meaning Trump likely won't give much ground on policy https://t.co/qfyaFyyBxC

— Philip Rucker (@PhilipRucker) May 6, 2016

harry: I think most people don’t care. BUT! There is a section of people who do care. Here’s a YouGov poll from January (just before the primaries started) in which only 14 percent of Republicans said Trump was a “true conservative.” He, of course, still held a 16-percentage-point lead over Ted Cruz in that survey.

julia.azari: Ryan is trying to make the party a more policy-driven one again. This necessarily (and not just for Republicans) means it cannot be hyper-responsive to every emotion its voters have. Sorry to be elitist, but I think that’s just true.

natesilver: I mean, the cynical interpretation is that voters come to the Republican Party for the cultural resentment, and then Ryan et al try to sell them on the movement conservatism once they’re in the building.

Trump suggests that not only is movement conservatism not the main draw, but you don’t really need it at all. Although I’d caution, as always, that Trump could be a sui generis case caused by, for instance, total dominance of media coverage.

julia.azari: What percent of the Republican primary vote did Trump win?

micah: Forty percent. But that’s why I’m not sure I agree with you, Clare — aren’t the members of the Freedom Caucus movement conservatives? Or maybe what they care about most is throwing rocks at the establishment, and Trump is one hell of a rock?

clare.malone: I think if we’re talking about people who have been on the outside of the power establishment — the Freedom Caucus — and they see that a new pole of power is coming into existence in the party — Trump — it’s a savvy move to jump on board and at least drag off his popularity.

julia.azari: See, I think the issue is that the definition of “movement conservative” is now muddled. For some it’s rock-throwing. For some it’s social and/or economic conservatism. Cultural stuff for others. Having not been sufficiently wrong about enough things this year, I’ll boldly predict that the Freedom Caucus will divide on their Trump support.

micah: Bold!

julia.azari: Well. I don’t know if it actually will. But I’ll make that prediction. I really want to be in one of those “who was wrongest” pundit round-ups.

natesilver: When I’m using the term “movement conservatism,” I mean a Reaganish or G.W.B.ish agenda. Supply-side economics, hawkish foreign policy (U.S. as leader of the free world), “family values.”

Also, it’s not actually that fun to be in one of those roundups, Julia.

harry: The group that Trump consistently did worst with in the primary was those who identified as “very conservative” and those who attended church more than once a week.

micah: Let me shift this discussion … should Trump give a sh*t what Ryan says?

clare.malone: Yes. He needs institutional support to run a national campaign, and Ryan is a big part of securing that machine power that you need.

harry: Yes. Yes, he should.

micah: Didn’t we think that about the primary campaign?

harry: Big difference, Micah, is this …

clare.malone: $$$$$$

harry: You need a unified Republican base to beat Clinton. And right now, Trump clearly doesn’t have that. He’s trailing in almost all the polls. That’s a big difference from the primary, where he led in all the polls. You cannot win a general election with 40 percent of the vote. You have one opponent.

natesilver: If Trump only gets 85 percent of the Republican vote, he’s probably screwed. Hell, if he gets only 88 percent, he’s probably screwed, given all his other problems. So even if this stuff is only at the margin, the marginal stuff matters.