MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 37

December 3, 2017

The Bewitching Tale of Morgan le Fay, a Captivating Character of Arthurian Legend

Ancient Origins

The legendary Morgan le Fay is quite often mixed with the Celtic goddess Morrigan. The two strong females seem to be separate women, but there is also a possibility that they are linked with each other.

Morgan le Fay is also known as Morgana, Morgane, Morgan le Faye, etc. She is said to be a powerful enchantress, and is also a character of the Arthurian legend. She became very popular in the modern world because of a novel by Marion Zimmer Bradley called The Mists of Avalon. The old legends, with roots in medieval times, had been transformed into the monumental novel, which conquered the hearts of millions of readers.

Morgan probably appears for the first time in literature in The Life of Merlin by Geoffrey of Monmouth (1100 -1155 AD). This text became one of the classic books connected with the Arthurian legends. Among the stories about knights and adventures, Morgan is portrayed as an evil character. She is the one often who leads the heroes of the legends into danger. She is also a very sensual part of the stories, as a woman who tried to seduce men.

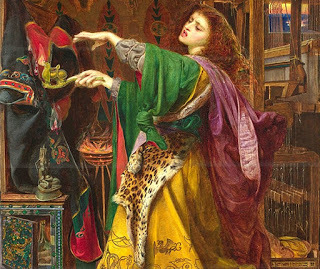

Morgan Le Fay by John R. Spencer Stanhope. (1880) (Public Domain)

The Goddess Morrigan

Morrigan, a Phantom Queen, is a goddess strongly connected with Irish and Celtic mythology. She is associated with fate and known as a goddess of war and death, but also fertility and numerous other things. She appears as a crow on the battlefield in legends. She is also linked to the Valkyries. Additionally, she is described as a triple goddess, called ''the three Morrigan''.

There is still an open discussion between the specialists in legends, myths, and literature about the connection of Morrigan with the Arthurian Morgan. It is quite possible that the literary character may have been inspired by old Irish tales about the goddess Morrigan. What's more interesting, language specialists suggest that the name of Morgan comes from Morrigan - which may have its roots in the words ''greatness'' and ''terror''.

Stories of a Dangerous Witch

In medieval stories, Morgan le Fay is one of the most popular, intriguing, and magnetic women connected with the Camelot court. It is unknown if she was a historical person. For centuries she was considered as a real woman who lived in different parts of Britain. She was believed to be a healer, enchantress, and a mysterious woman with many spiritual talents. Some people called her a “wise woman”, which could also mean witch.

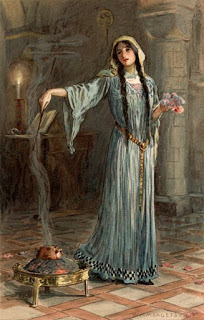

“The Magic Circle” by John William Waterhouse. (1886) (Public Domain)

In late medieval stories, the picture of a good woman who served the people with her talents had changed. Morgan started to appear as the daughter of Lady Irgraine and her first husband Gorlois – and King Arthur was her half-brother. She was also an adviser to Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table.

According to the legend by Thomas Malory (1415 – 1471), she was unhappily married to King Urien. At the same time, she became a sexually aggressive woman who had many lovers - including the famous Merlin. However, her love of Lancelot was unrequited. Morgan appeared also as an indirect cause of Arthur's death.

“Morgan le Fay,” by Christian Waller (1920). (Art Gallery of Ballarat)

Her role expanded in the 13th century in the Vulgate Cycle and Post-Vulgate Cycle. During this period, Morgan became an anti-heroine. She was described as a malicious, cruel, and ambitious nemesis of Arthur. These stories say that Morgan had been sent to a convent to become a nun. However, this was the place where she apparently started her study in the art of magic.

With time she became Merlin’s lover and he taught her witchcraft. Morgan was a very good student and soon became a powerful witch. It is possible that parts of her story were inspired by the motifs of Medea who killed her rival for Jason's affection, and Deianira who sent a poisoned tunic to Hercules.

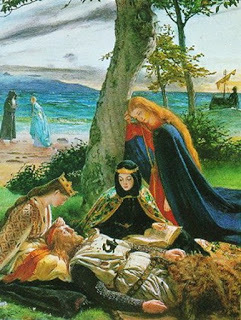

She was known to have studied magic while she was being brought up in the nunnery.” (1914) By W. H. Margetson from: Legends of King Arthur and His Knights. (University of Rochester)

One of the most important parts of her story is her affection for Lancelot. She used all of her knowledge, drugs, and enchantments to try to have Lancelot for herself. In the stories he appears as a strong hero who doesn't allow the beautiful witch to break his rules.

Nonetheless, she manages to capture him under her spell and keeps him in prison, but when he gets ill and is near death she releases him. There are many different variations of this story - in some Morgan appears as a sexual evil, in others as a lost woman who really loves Lancelot.

Morgan le Fay by Edward Burne-Jones. (1862) (Public Domain)

The Last Show by the Lady of Avalon

The final version of her legend concentrates on witchcraft. Morgan is described as a witch who uses her spells to reach her own goals. In these tales, she has gained an ability to transform herself into a crow, horse, or any other animal. Usually, the animals are black.

It is likely that this version of the legend connected Morgan with the goddess Morrigan. Compared to different stories, this time Morgan vanishes for a long time and Arthur begins to believe that she is dead. However, one day he meets her again and she declares her plan to move to the Isle of Avalon to live there. Arthur discovers that the rumors about a secret love affair between her and Lancelot were true. Then the goddess Fortune appears, and foretells Arthur's death.

The story ends with Morgan as a lady in a black hood, who takes the dying Arthur to his final resting place in Avalon. She seems to be strongly connected with death, but is like a person who doesn't belong to the world of the dead nor the world of the living.

The Death of King Arthur by James Archer. (1860) (Public Domain)

Morgan le Fay Dressed in High Heels

It is unknown if the legend about Morgan le Fay was highly inspired by Morrigan, or the similarities are caused by coincidence. Celtic mythology is not easy to understand and several stories may be applied to different people.

Regardless, Morgan le Fay became an icon of pre-Roman and pre-Christian stories. She is also a popular character in modern pop-culture. Artists still record songs, create paintings and drawings, and write books to commemorate the magnetic medieval woman known as Morgan le Fay. Nowadays, she is always presented as a beautiful woman dressed in a very attractive way. She appears to be an icon of medieval sexual desires.

Morgana Le Fay, Anikó Salamon's art for the video game King Arthur II. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

No matter if she was real person, or only a legend, she is undoubtedly one of the most famous women of medieval Northern Europe. She continues to be recognized as a magical force in the mysterious phenomenon called Fata Morgana - a form of mirage common off the shores of Sicily

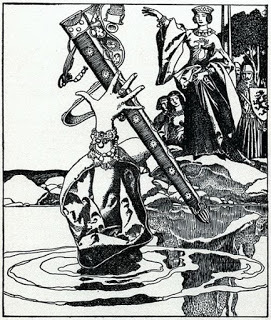

Queen Morgana Loses Excalibur His Sheath, Howard Pyle's illustration from The Story of King Arthur and His Knights. (1903) (Public Domain)

Featured image: Morgan le Fay by Frederick Sandys. (1864) Source: Public Domain

By Natalia Klimczak

Published on December 03, 2017 00:00

December 2, 2017

Your 60-second guide to the Black Death

History Extra

Q: What was the Black Death?

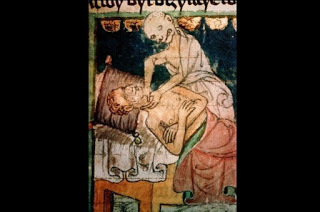

A: In the Middle Ages the Black Death, or ‘pestilencia’, as contemporaries called various epidemic diseases, was the worst catastrophe in recorded history. Some dubbed it ‘magna mortalitas’ (great mortality), emphasising the death rate. It destroyed a higher proportion of the population than any other single known event. One observer noted ‘the living were scarcely sufficient to bury the dead.’ No one could be sure what caused it.

Q: When did the Black Death break out? A: The disease arrived in western Europe in 1347 and in England in 1348. It faded away in the early 1350s. Q: Where did it originate, and what areas did it affect? A: Breaking out in ‘the east’, as medieval people put it, it came north and west after striking the eastern Mediterranean and Italy, Spain and France. It then came to Britain, where it struck Dorset and Hampshire along the south coast of England simultaneously. It then spread north and east, then on to Scandinavia and Russia.

Q: How did it spread?

A: The disease spread from animal populations to humans through the agency of fleas from dying rats. Plague bacteria stifled the vital organs of those infected. Its lethality arose from the onslaught of three types: bubonic, pneumonic and, occasionally, septicaemic plague.

Q: Who was affected?

A: Old and young, men and women: all of society – royalty, peasants, archbishops, monks, nuns and parish clergy. Both artisan and artistic skills were lost or severely affected, from cathedral building in Italy to pottery production in England. Artists such as the Lorinzetti brothers of Siena were victims, and the English royal masons, the Ramseys, died. There were shortages of people to till the land and tend cattle and sheep.

Q: What were the symptoms?

A: Symptoms included swellings – most commonly in the groin, armpits and neck; dark patches, and the coughing up of blood.

Medieval observers – and their modern counterparts in 19th-century China and 20th-century Vietnam, observing more recent outbreaks – noted that different strains of the disease took from five days to as little as half a day to cause death.

Q: How many people were killed?

A: In Europe in three or four years, 50 million people died. The population was reduced from some 80 million to 30 million. It killed at least 60 per cent of the population in rural and urban areas. Some communities such as Quob in Hampshire were wiped out; many rural communities went into decline and were in time deserted. We know that some populations survived, but medieval people had no such knowledge – all they knew was that everyone would certainly die.

Q: Was it a one-off occurrence?

A: No. There have been three identified so-called ‘pandemics’. First, there was a significant international epidemic in the sixth century AD. Second, starting with The Black Death – its deadliest attack - plague later returned to Britain in 1361 (when it affected especially younger and elderly people); 1374, and regularly until it disappeared shortly after the Great Plague of 1665. Third, the disease broke out once more in Asia in the 1890s, and established new foci, where it is still found in animal populations today.

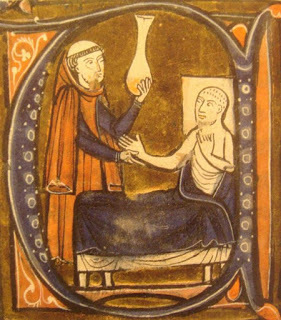

Q: What remedies were used?

A: Medieval people believed that the disease came from God, and so responded with prayers and processions. Some contemporaries realised that the only remedy for plague was to run away from it – Boccaccio’s Decameron is a series of tales told among a group of young people taking refuge from the Black Death outside Florence. There was no known remedy, but people wanted medicines: Chaucer commented that the Doctor of Physic made much ‘gold’ out of the pestilence. The plague bacteria were identified in Asia in the 1890s, and the connection with animals and fleas established. Modern antibiotics can combat plague, but these are under threat from mutating diseases and immunity to antibiotics’ effects.

Q: Will it return?

A: In fact, the disease has never gone away. An outbreak in Surat in India in the early 1990s caused panic across the world. The death of a herdsman in Kyrgyzstan in 2013 from bubonic plague was wildly exaggerated in the media. With our better understanding of historic plague, other diseases among animals such as bird-flu and swine-flu are carefully monitored today in case they develop into person-to-person infections resulting in high mortality as witnessed in the Black Death.

Tom Beaumont James, a professor of archaeology and history at the University of Winchester, sums up the need-to-know facts about the Black Death of 1348-50

Q: What was the Black Death?

A: In the Middle Ages the Black Death, or ‘pestilencia’, as contemporaries called various epidemic diseases, was the worst catastrophe in recorded history. Some dubbed it ‘magna mortalitas’ (great mortality), emphasising the death rate. It destroyed a higher proportion of the population than any other single known event. One observer noted ‘the living were scarcely sufficient to bury the dead.’ No one could be sure what caused it.

Q: When did the Black Death break out? A: The disease arrived in western Europe in 1347 and in England in 1348. It faded away in the early 1350s. Q: Where did it originate, and what areas did it affect? A: Breaking out in ‘the east’, as medieval people put it, it came north and west after striking the eastern Mediterranean and Italy, Spain and France. It then came to Britain, where it struck Dorset and Hampshire along the south coast of England simultaneously. It then spread north and east, then on to Scandinavia and Russia.

Q: How did it spread?

A: The disease spread from animal populations to humans through the agency of fleas from dying rats. Plague bacteria stifled the vital organs of those infected. Its lethality arose from the onslaught of three types: bubonic, pneumonic and, occasionally, septicaemic plague.

Q: Who was affected?

A: Old and young, men and women: all of society – royalty, peasants, archbishops, monks, nuns and parish clergy. Both artisan and artistic skills were lost or severely affected, from cathedral building in Italy to pottery production in England. Artists such as the Lorinzetti brothers of Siena were victims, and the English royal masons, the Ramseys, died. There were shortages of people to till the land and tend cattle and sheep.

Q: What were the symptoms?

A: Symptoms included swellings – most commonly in the groin, armpits and neck; dark patches, and the coughing up of blood.

Medieval observers – and their modern counterparts in 19th-century China and 20th-century Vietnam, observing more recent outbreaks – noted that different strains of the disease took from five days to as little as half a day to cause death.

Q: How many people were killed?

A: In Europe in three or four years, 50 million people died. The population was reduced from some 80 million to 30 million. It killed at least 60 per cent of the population in rural and urban areas. Some communities such as Quob in Hampshire were wiped out; many rural communities went into decline and were in time deserted. We know that some populations survived, but medieval people had no such knowledge – all they knew was that everyone would certainly die.

Q: Was it a one-off occurrence?

A: No. There have been three identified so-called ‘pandemics’. First, there was a significant international epidemic in the sixth century AD. Second, starting with The Black Death – its deadliest attack - plague later returned to Britain in 1361 (when it affected especially younger and elderly people); 1374, and regularly until it disappeared shortly after the Great Plague of 1665. Third, the disease broke out once more in Asia in the 1890s, and established new foci, where it is still found in animal populations today.

Q: What remedies were used?

A: Medieval people believed that the disease came from God, and so responded with prayers and processions. Some contemporaries realised that the only remedy for plague was to run away from it – Boccaccio’s Decameron is a series of tales told among a group of young people taking refuge from the Black Death outside Florence. There was no known remedy, but people wanted medicines: Chaucer commented that the Doctor of Physic made much ‘gold’ out of the pestilence. The plague bacteria were identified in Asia in the 1890s, and the connection with animals and fleas established. Modern antibiotics can combat plague, but these are under threat from mutating diseases and immunity to antibiotics’ effects.

Q: Will it return?

A: In fact, the disease has never gone away. An outbreak in Surat in India in the early 1990s caused panic across the world. The death of a herdsman in Kyrgyzstan in 2013 from bubonic plague was wildly exaggerated in the media. With our better understanding of historic plague, other diseases among animals such as bird-flu and swine-flu are carefully monitored today in case they develop into person-to-person infections resulting in high mortality as witnessed in the Black Death.

Tom Beaumont James, a professor of archaeology and history at the University of Winchester, sums up the need-to-know facts about the Black Death of 1348-50

Published on December 02, 2017 00:00

December 1, 2017

Alcohol as medicine through the ages

Ancient Origins

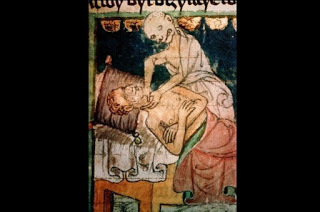

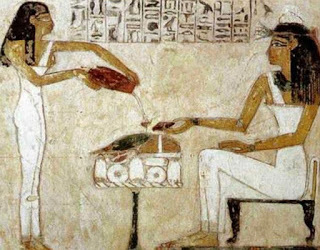

While no one knows exactly when alcohol was first produced, it was presumably the result of a fortuitous accident that occurred at least tens of thousands of years ago. However, the discovery of late Stone Age beer jugs has established the fact that intentionally fermented beverages existed at least as early as the Neolithic period around 10,000 years ago, and it has been suggested that beer may have preceded bread as a staple. Wine clearly appeared as a finished product in Egyptian pictographs around 4,000 BC, and residues of wine samples in Greece date to the same period. But alcohol was not consumed in the same way as it is today. In fact, in ancient times, alcohol was seen as an important medicinal ingredient and as an essential part of the diet.

From the moment the first alcoholic beverages were discovered, man has used it as a medicine. Apart from the stress relieving, relaxing nature that alcohol has on the body and mind, alcohol is an antiseptic and in higher doses has anesthetizing effects. But it is a combination of alcohol and natural botanicals, which creates a far more effective medicine and has been used as such for thousands of years. It is the origin of the most famous toast, “Let’s drink to health”, which exists in many languages around the world.

One of the earliest signs of the use of alcohol as a medicine dates back around 5,000 years to a jar found in the tomb of one of the first pharaohs of Egypt, Scorpion I. With extremely sensitive chemical techniques, bioarchaeologists were able to identify the different compounds within the residue left in the jar. They found that the remnants contained wine, as well as a number of herbs known to have medicinal properties Wine was also a frequent component of ancient Roman medicine. As is well known nowadays, alcohol is a good means of extracting the active elements from medicinal plants.

Wine was the only form of alcohol known to the Romans as distillation wasn’t discovered until the middle ages. Herbs infused in wine were a regular medicinal stratagem which would have a degree of effect given the alcohol’s ability to extract the active compounds of a number of herbs.

One of the most famous practitioners of alcohol-based herbal remedies was the father of modern medicine, Hippocrates, whose own special recipe for intestinal worms was known as Hippocraticum Vinum. Hippocrates was making a crude form of vermouth in approximately 400BC using local herbs in wine, but herbal infusions took on a whole new level of potency once distillation was discovered.

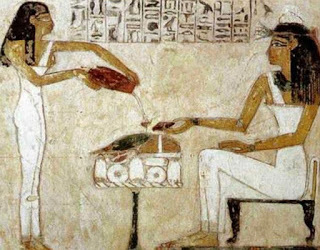

The spread of Christianity with the crusades from 1095 onwards brought knowledge about the art of alchemy and distillation from the early Arab scholars. The ‘Water of Life’ was being refined all over Europe (known as such due to it being safer to drink than disease-ridden water) and soon commercial apothecaries grew from the spread of the knowledge of distillation and botanical extraction selling both raw ingredients and herbal tinctures. Throughout antiquity, available water was polluted with dangerous microbes, so drinking alcohol, which involved the liquid being boiled or subjected to similarly sterilising treatments, was seen as being healthier and safer.

One of the earliest records of medicinal alcohol dating to this period comes from Roger Bacon, a 13th Century English philosopher and writer on alchemy and medicine. According to the translation (published in 1683) Bacon suggests wine could: "Preserve the stomach, strengthen the natural heat, help digestion, defend the body from corruption, concoct the food till it be turned into very blood." But he also recognises the dangers of consuming in excess: "If it be over-much guzzles, it will on the contrary do a great deal of harm: For it will darken the understanding, ill-affect the brain... beget shaking of the limbs and bleareyedness."

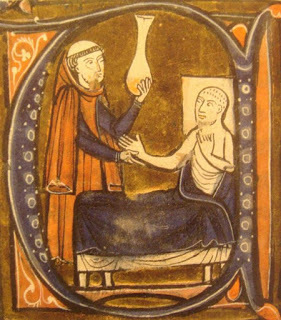

Alcohol as medicine in the Middle Ages ( public domain )

European colonisation during the 15 th and 16 th centuries gave the apothecaries an abundance of exotic herbs, spices, barks, peels and berries to add to their medicine cabinets and from this point until relatively recently, a large percentage of medicines were made with an alcoholic base.

Gin is a good example of a spirit which was originally designed to be used as a medicine; the use of Juniper as a diuretic was believed to be able to cleanse the fevers and tropical diseases that the Dutch settlers were suffering from in the newly colonized West Indies. Many of today’s brands such as Chartreuse and Benedictine were born in the monasteries of Europe designed as stomach tonics and general elixirs.

However, by the 18 th century, there were growing concerns about the more harmful effects of alcohol, including drunkenness, crime, alcoholism and poverty. In 1725, the first documented petition by the Royal College of Physicians expresses fellows' concerns about "pernicious and growing use of spirituous liquors". By the 19th Century, temperance movements began to emerge in Britain - at first some advised restrictions on certain drinks only, but over time their stance shifted to call for total abstinence.

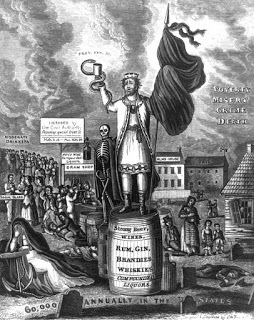

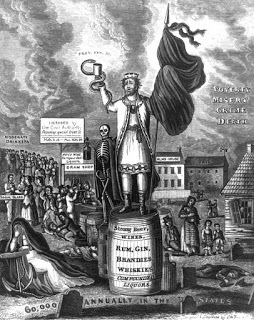

An 1820 engraving warning of the dangers of alcohol ( public domain )

The irony is that we now live in an age where although alcohol is socially acceptable, classing it as ‘good for you’ is frowned upon and is a notion which seems to have been born from the development of modern medicine.

Old-fashioned pharmacies with their jars of coloured macerations died out in the early part of the 1900’s when science was able to synthetically reproduce the key properties of nature therefore no-longer needing alcohol as a base. Drug companies have also been keen to brush over the fact that organic-based medicine is free whereas tablets are not. You can’t patent nature, but you can patent pills.

By April Holloway

While no one knows exactly when alcohol was first produced, it was presumably the result of a fortuitous accident that occurred at least tens of thousands of years ago. However, the discovery of late Stone Age beer jugs has established the fact that intentionally fermented beverages existed at least as early as the Neolithic period around 10,000 years ago, and it has been suggested that beer may have preceded bread as a staple. Wine clearly appeared as a finished product in Egyptian pictographs around 4,000 BC, and residues of wine samples in Greece date to the same period. But alcohol was not consumed in the same way as it is today. In fact, in ancient times, alcohol was seen as an important medicinal ingredient and as an essential part of the diet.

From the moment the first alcoholic beverages were discovered, man has used it as a medicine. Apart from the stress relieving, relaxing nature that alcohol has on the body and mind, alcohol is an antiseptic and in higher doses has anesthetizing effects. But it is a combination of alcohol and natural botanicals, which creates a far more effective medicine and has been used as such for thousands of years. It is the origin of the most famous toast, “Let’s drink to health”, which exists in many languages around the world.

One of the earliest signs of the use of alcohol as a medicine dates back around 5,000 years to a jar found in the tomb of one of the first pharaohs of Egypt, Scorpion I. With extremely sensitive chemical techniques, bioarchaeologists were able to identify the different compounds within the residue left in the jar. They found that the remnants contained wine, as well as a number of herbs known to have medicinal properties Wine was also a frequent component of ancient Roman medicine. As is well known nowadays, alcohol is a good means of extracting the active elements from medicinal plants.

Wine was the only form of alcohol known to the Romans as distillation wasn’t discovered until the middle ages. Herbs infused in wine were a regular medicinal stratagem which would have a degree of effect given the alcohol’s ability to extract the active compounds of a number of herbs.

One of the most famous practitioners of alcohol-based herbal remedies was the father of modern medicine, Hippocrates, whose own special recipe for intestinal worms was known as Hippocraticum Vinum. Hippocrates was making a crude form of vermouth in approximately 400BC using local herbs in wine, but herbal infusions took on a whole new level of potency once distillation was discovered.

The spread of Christianity with the crusades from 1095 onwards brought knowledge about the art of alchemy and distillation from the early Arab scholars. The ‘Water of Life’ was being refined all over Europe (known as such due to it being safer to drink than disease-ridden water) and soon commercial apothecaries grew from the spread of the knowledge of distillation and botanical extraction selling both raw ingredients and herbal tinctures. Throughout antiquity, available water was polluted with dangerous microbes, so drinking alcohol, which involved the liquid being boiled or subjected to similarly sterilising treatments, was seen as being healthier and safer.

One of the earliest records of medicinal alcohol dating to this period comes from Roger Bacon, a 13th Century English philosopher and writer on alchemy and medicine. According to the translation (published in 1683) Bacon suggests wine could: "Preserve the stomach, strengthen the natural heat, help digestion, defend the body from corruption, concoct the food till it be turned into very blood." But he also recognises the dangers of consuming in excess: "If it be over-much guzzles, it will on the contrary do a great deal of harm: For it will darken the understanding, ill-affect the brain... beget shaking of the limbs and bleareyedness."

Alcohol as medicine in the Middle Ages ( public domain )

European colonisation during the 15 th and 16 th centuries gave the apothecaries an abundance of exotic herbs, spices, barks, peels and berries to add to their medicine cabinets and from this point until relatively recently, a large percentage of medicines were made with an alcoholic base.

Gin is a good example of a spirit which was originally designed to be used as a medicine; the use of Juniper as a diuretic was believed to be able to cleanse the fevers and tropical diseases that the Dutch settlers were suffering from in the newly colonized West Indies. Many of today’s brands such as Chartreuse and Benedictine were born in the monasteries of Europe designed as stomach tonics and general elixirs.

However, by the 18 th century, there were growing concerns about the more harmful effects of alcohol, including drunkenness, crime, alcoholism and poverty. In 1725, the first documented petition by the Royal College of Physicians expresses fellows' concerns about "pernicious and growing use of spirituous liquors". By the 19th Century, temperance movements began to emerge in Britain - at first some advised restrictions on certain drinks only, but over time their stance shifted to call for total abstinence.

An 1820 engraving warning of the dangers of alcohol ( public domain )

The irony is that we now live in an age where although alcohol is socially acceptable, classing it as ‘good for you’ is frowned upon and is a notion which seems to have been born from the development of modern medicine.

Old-fashioned pharmacies with their jars of coloured macerations died out in the early part of the 1900’s when science was able to synthetically reproduce the key properties of nature therefore no-longer needing alcohol as a base. Drug companies have also been keen to brush over the fact that organic-based medicine is free whereas tablets are not. You can’t patent nature, but you can patent pills.

By April Holloway

Published on December 01, 2017 00:00

November 30, 2017

Was Life in Medieval Europe Dominated by a Fear of Purgatory?

Made from History

Purgatory by Follower of Hieronymus Bosch, late 15th century.

In Middle Ages Europe organised Christianity extended its reach into daily life through a growth in devout fervour, an ideological and sometimes military war against Islam and increased political power. The thought that after death one may suffer or linger in Purgatory due to one’s sins instead of going to Heaven was one such way the Church exercised power over believers.

The concept of Purgatory was established by the Church in the early part of the Middle Ages and grew more pervasive in the late period of the epoch. However, the idea was not exclusive to medieval Christianity and had roots in Judaism and counterparts in other religions. The idea was more acceptable — and perhaps more useful — than sin resulting in eternal damnation. Purgatory was perhaps like Hell, but its flames purified instead of consumed eternally.

The Rise of Purgatory: From Prayer for the Dead to Selling Indulgences

Temporary and purifying or not, the threat of feeling actual fire burn your body in the afterlife while the living prayed for your soul to be allowed to enter Heaven was still a daunting scenario. It was even said by some that certain souls, after lingering in Purgatory, would still be sent to Hell if not sufficiently purified come Judgement Day.

The Catholic Church officially accepted the doctrine of Purgatory in the 1200s and it became central to the teachings of the Church. Though not as central in the Greek Orthodox Church, the doctrine still served a purpose, especially in the 15th century Byzantine Empire, albeit interpretations of ‘purgatorial fire’ among Eastern Orthodox theologians were less literal.

By the late Middle Ages the practice of granting indulgences was associated with the interim state between death and the afterlife known as Purgatory. Indulgences were a way to pay for sins committed after being absolved, which can be carried out in life or while languishing in Purgatory.

Indulgences can therefore be distributed to both the living and dead so long as someone living pays for them, whether through prayer, ‘witnessing’ ones faith, performing charitable acts, fasting or by other means.

The practice of the Catholic Church selling indulgences grew substantially during the late Medieval period, contributing to the perceived corruption of the Church and helping to inspire the Reformation.

Devotion = Fear?

Miniature depicting angels leading souls from the fires of Purgatory, circa 1440. Credit: The Hours of Catherine of Cleves, Morgan Library & Museum

Since even a forgiven sin required punishment, dying with outstanding punishments or owing devotional acts to make up for the sin was an ominous prospect. It meant a purging of sins in the afterlife.

Purgatory was depicted in medieval art — specifically in prayer books, which were packed with images of death — as more or less the same as Hell. In an environment so preoccupied with death, sin and the afterlife, naturally people became more devout in order to avoid such a fate.

The thought of spending time in Purgatory helped fill churches, increased the power of the clergy and inspired people — largely through fear — to do things as diverse as pray more, give money to the Church and fight in the Crusades.

Graham Land

Graham is an editor and contributor at Made From History. A London-based writer originally from Washington, DC, he holds a master's degree in Cultural History from Malmö University in Sweden.

Purgatory by Follower of Hieronymus Bosch, late 15th century.

In Middle Ages Europe organised Christianity extended its reach into daily life through a growth in devout fervour, an ideological and sometimes military war against Islam and increased political power. The thought that after death one may suffer or linger in Purgatory due to one’s sins instead of going to Heaven was one such way the Church exercised power over believers.

The concept of Purgatory was established by the Church in the early part of the Middle Ages and grew more pervasive in the late period of the epoch. However, the idea was not exclusive to medieval Christianity and had roots in Judaism and counterparts in other religions. The idea was more acceptable — and perhaps more useful — than sin resulting in eternal damnation. Purgatory was perhaps like Hell, but its flames purified instead of consumed eternally.

The Rise of Purgatory: From Prayer for the Dead to Selling Indulgences

Temporary and purifying or not, the threat of feeling actual fire burn your body in the afterlife while the living prayed for your soul to be allowed to enter Heaven was still a daunting scenario. It was even said by some that certain souls, after lingering in Purgatory, would still be sent to Hell if not sufficiently purified come Judgement Day.

The Catholic Church officially accepted the doctrine of Purgatory in the 1200s and it became central to the teachings of the Church. Though not as central in the Greek Orthodox Church, the doctrine still served a purpose, especially in the 15th century Byzantine Empire, albeit interpretations of ‘purgatorial fire’ among Eastern Orthodox theologians were less literal.

By the late Middle Ages the practice of granting indulgences was associated with the interim state between death and the afterlife known as Purgatory. Indulgences were a way to pay for sins committed after being absolved, which can be carried out in life or while languishing in Purgatory.

Indulgences can therefore be distributed to both the living and dead so long as someone living pays for them, whether through prayer, ‘witnessing’ ones faith, performing charitable acts, fasting or by other means.

The practice of the Catholic Church selling indulgences grew substantially during the late Medieval period, contributing to the perceived corruption of the Church and helping to inspire the Reformation.

Devotion = Fear?

Miniature depicting angels leading souls from the fires of Purgatory, circa 1440. Credit: The Hours of Catherine of Cleves, Morgan Library & Museum

Since even a forgiven sin required punishment, dying with outstanding punishments or owing devotional acts to make up for the sin was an ominous prospect. It meant a purging of sins in the afterlife.

Purgatory was depicted in medieval art — specifically in prayer books, which were packed with images of death — as more or less the same as Hell. In an environment so preoccupied with death, sin and the afterlife, naturally people became more devout in order to avoid such a fate.

The thought of spending time in Purgatory helped fill churches, increased the power of the clergy and inspired people — largely through fear — to do things as diverse as pray more, give money to the Church and fight in the Crusades.

Graham Land

Graham is an editor and contributor at Made From History. A London-based writer originally from Washington, DC, he holds a master's degree in Cultural History from Malmö University in Sweden.

Published on November 30, 2017 00:00

November 29, 2017

Anglo-Saxon and Viking Houses

Made from History

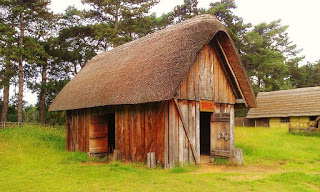

A reconstruction of a typical Anglo-Saxon structure

The Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings were two peoples that colonised Britain during the Middle Ages. A collection of Germanic tribes, the Anglo-Saxons first settled Britain during the 5th century, migrating in significant numbers from around 410 to 560 AD. The Vikings, who were mostly Scandinavian, began invading the British Isles in the early Medieval period and began settling as early as 865. The style of houses built by each culture are unique, but also share similarities. They are both described below.

Anglo-Saxon Dwellings

Several different designs made up the building of the Anglo Saxons. Their homes were primarily single-roomed structures with a sunken floor. The perimeter was marked out around the space required and inside that the ground was dug out to about a metre deep.

This space was an ingenious piece of engineering for a time that is often considered backwards or ‘dark’. The space was used for either storage or, more likely, for insulation. Archaeologists have found evidence that this space was filled with straw in the autumn which was then left to decay; this produced heat, meaning that the Anglo-Saxons invented a rudimentary form of central heating.

Around this space, posts were driven into the ground to form the superstructure. The roof was normally thatched with straw, creating a largely watertight environment. However thatching a building meant that the roof would have to be replaced often, as the straw rotted.

Inside, a fire pit or hearth would take pride of place in the centre of the house. A warm, dry environment was hard to come by in the Dark Ages, so the fire pit needed to be central, offering comfort to the residents. Above it a smoke-hole would sometimes be cut in the roof to allow the fumes to escape; some homes didn’t have this and were instead built with a high ceiling into which the smoke could escape.

The floor was usually carpeted with rushes, which were used because they provided a warmer surface than the cold ground. They also were easy to replace and were therefore perfect for keeping the house clean, particularly during a period when people often house-shared with animals.

Doors were hinged either with wood or iron if the owner could afford it and boasted a latch and a lock if the building doubled as a workshop.

The typical centre of an Anglo-Saxon home was the hearth.

Viking Housing

Scandinavian houses were similar in design to Saxon structures, but often used less wood and had larger roofs that would reach almost to the ground. This was for two reasons: one, there was much less timber available to build houses with and most available wood would be used to fashion boats; secondly, the thatch offered more insulation than wooden walls and Scandinavia is much colder than Britain, so a larger percentage of the building was covered in the heat-retaining material. viking house

This is a reconstructed Longhouse; Landa outdoor museum in Forsand, Norway. Its low walls and large amounts of thatching is characteristic of Dark Age Scandinavian buildings.

A uniquely Scandinavian design that flourished in Britain in the wake of the Viking invasions was the longhouse, a much larger construction that had bowed walls. The walls curved outwards, creating an even larger space inside for communal feasting and entertaining. The construction was particularly favoured amongst the ruling classes.

Built to Last

A Stave Church built in the twelfth century in Norway. It still stands today.

These wooden buildings of both peoples, if properly constructed and looked after, could last for hundreds of years. For example, there are a number of wooden Scandinavian churches built in the early Medieval period that still stand today. Despite this, many, particularly amongst the nobility of both the Anglo-Saxons and the Norsemen, would annually tear their house down and built a new structure form scratch; it was seen as unfashionable to live in an old house.

Craig Bessell: Contributing Author at Made From History. I Graduated from Cardiff University in 2014 with a Bachelor of Arts in History. I love the stories more than the dates, but they're important too.

Published on November 29, 2017 00:00

November 27, 2017

Ancient Rome – 6 burning questions

History Extra

Who founded Ancient Rome?

Like all ancient societies, the Romans possessed a heroic foundation story. What made the Romans different, however, is that they created two distinct creation myths for themselves.

In the first it was claimed that they were descended from the royal Trojan refugee Aeneas (himself the son of the goddess Venus). In the second it was stated that the city of Rome was founded by, and ultimately named after, Romulus, son of a union between an earthly princess and the god Mars.

Both myths helped establish the Romans as a divinely chosen people whose ancestry could be traced back to Troy and the Hellenistic world. Roman tradition had Romulus’ foundling city established on the Palatine Hill in what became, for Rome, ‘Year One’ (or 753 BC in the Christian calendar of the West). Archaeological excavation on the hill has found settlement here dating back to at least 1000 BC.

Who ruled in Ancient Rome?

Rome made much of the fact that it was a republic, ruled by the people and not by kings.

Rome had overthrown its monarchy in 509 BC, and legislative power was thereafter vested in the people’s assemblies: political power in the senate, and military power with two annually elected magistrates known as consuls.

The acronym ‘SPQR’, for Senatus Populusque Romanus (‘the Senate and People of Rome’) was proudly emblazoned across inscriptions and military standards throughout the Mediterranean – a reminder that Rome’s people (theoretically) had the last word.

By the late 1st century BC, the combination of power-hungry politicians and large overseas territories resulted in the breakdown of traditional systems of government. Even after the rise of the emperors – kings in all but name, who ‘guided’ the Roman political system in the 1st century AD – ‘SPQR’ continued to be used in order to sustain the fiction that Rome was a state governed by purely republican principles.

Who were gladiators in ancient Rome?

Gladiatorial games were organised by the elite throughout the Roman empire in order to distract the population from the reality of daily life.

Most gladiators were purchased from slave markets, being chosen for their strength, stamina and good looks. Although taken from the lowest elements of society, the gladiator was a breed apart from the ‘normal’ slave or prisoner of war, being well-trained combatants whose one role in life was to fight and occasionally to kill for the amusement of the Roman mob.

Not all those who fought as gladiators were slaves or convicts, however. Some were citizens down on their luck (or heavily in debt) while some, like the emperor Commodus, simply did it for ‘fun’.

Whatever their reasons for ending up in the arena, gladiators were adored by the Roman public for their bravery and spirit. Their images appeared frequently in mosaics, wall paintings and on glassware and pottery.

In Ancient Rome, what was the law of the twelve tables?

The Twelve Tables was the primary legislative basis for Rome’s republican constitution, protecting the working classes from arbitrary punishment and excessive treatment by the ruling elite (patricians).

Created around 450 BC, the tables were a code that set out the rights and obligations of the people in areas such as marriage, divorce, burial, inheritance, property and ownership, injury, compensation, debt and slavery.

Key provisions included the establishment of burial grounds outside the limits of the city walls, the control of property if the stakeholder was decreed insane, the continual guardianship of women (passing from father to husband), the treatment of children and of slaves (as property), and the settling of compensation claims for injuries sustained at work.

Although the power of the ruling classes was not really constrained by the plebs, the twelve tables were never repealed – they formed the cornerstone of Roman law until well into the 5th century AD.

What did they eat in Ancient Rome?

The Romans ate pretty much everything they could lay their hands on. Meat, especially pork and fish, however, were expensive commodities, and so the bulk of the population survived on cereals (wheat, emmer and barley) mixed with chickpeas, lentils, turnips, lettuce, leek, cabbage and fenugreek.

Olives, grapes, apples, plums and figs provided welcome relief from the traditional forms of thick, cereal-based porridge (tomatoes and potatoes were a much later introduction to the Mediterranean), while milk, cheese, eggs and bread were also daily staples.

The Romans liked to vary their cooking with sweet (honey) and sour (fermented fish) sauces, which often helpfully disguised the taste of rotten meat.

Dining as entertainment was practised within elite society – lavish dinner parties were the ideal way to show off wealth and status. Recipes compiled in the 4th century supply us with details of tasty treats such as pickled sow’s udders and stuffed dormice.

Why did Ancient Rome fall?

A whole variety of reasons can be suggested to explain the fall of the Roman Empire in the west: disease, invasion, civil war, social unrest, inflation, economic collapse. In fact all were contributory factors, although key to the collapse of Roman authority was the prolonged period of imperial in-fighting during the 3rd and 4th century.

Conflict between multiple emperors severely weakened the military, eroded the economy and put a huge strain upon local populations. When Germanic migrants arrived, many western landowners threw their support behind the new ‘barbarian’ elite rather than continuing to back the emperor.

Reduced income from the provinces meant that Rome could no longer pay or feed its military and civil administration, making the imperial system of government redundant. The western half of the Roman empire mutated into a variety of discrete kingdoms while the east, which largely avoided both the in-fighting and barbarian migrations, survived until the 15th century.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication. These Q&As were taken from our ‘History Extra explains’ series, which answers burning questions about ancient Rome, the Tudors, ancient Egypt and the First World War.

Published on November 27, 2017 23:30

November 26, 2017

The Colossus of Rhodes: Ancient Greek Mega Statue

Ancient Origins

The Colossus of Rhodes was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and the most ambitious and tallest statue of the Hellenistic period. The last of the seven wonders to be completed, it was a statue built to thank the gods for victory over an invading enemy. Bearing a striking resemblance to the Statue of Liberty in the United States, the Colossus of Rhodes stood for less than sixty years before being destroyed by an earthquake. Some mystery remains as to where it was really located and what happened after it was destroyed.

Since ancient times, the small Greek island of Rhodes has been a main intersection between the Aegean and the Mediterranean seas, and was an important economic center in the ancient world. The capital city, also named Rhodes, was built in 408 BC and was designed to take advantage of the island's best natural harbor on the northern coast. In 357 BC the island was conquered by Mausolus of Halicarnassus but fell into Persian hands in 340 BC and was finally captured by Alexander the Great in 332 BC. In the late fourth century BC, Rhodes allied with Ptolemy I of Egypt against their common enemy, Antigonus I Monophthalmus of Macedonia. In 305 BC, Antigonus sent his son Demetrius to capture and punish the city of Rhodes for its alliance with Egypt. He attacked the island with 40,000 men and weapons and started a war which lasted a year. A relief force of ships sent by Ptolemy arrived in 304 BC, and Antigonus’ army abandoned the siege, leaving behind most of their siege equipment. To celebrate their victory, the Rhodians sold the equipment and decided to use the money to build a huge statue, to their sun god, Helios, called the Colossus of Rhodes. Nearly as tall as the iconic Statue of Liberty built 2,000 years later, the Colossus was also erected as a celebration of freedom.

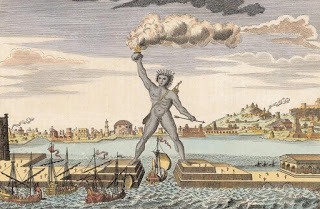

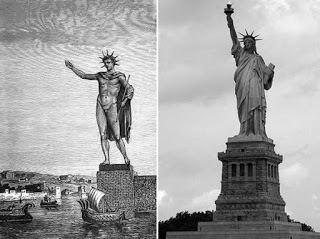

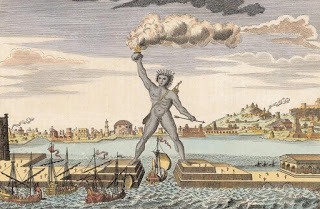

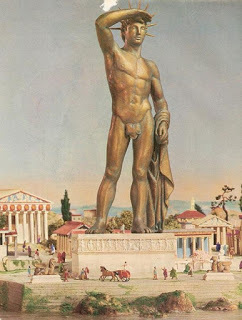

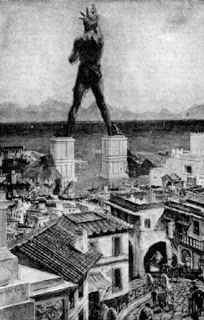

The Colossus of Rhodes, depicted in this hand-colored engraving, was built about 280 BC. Standing 30 meters (100 feet) high, it was built to guard the entrance to the harbor at Rhodes. The ancient Greeks and Romans considered it to be one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Public Domain

According to Pliny the Elder, a Greek historian who lived several centuries after the Colossus was built, its construction took 12 years and was completed in 280 BC. The pride of the city, the people thought the statue would stand forever. Charles of Lindos was its architect and was given the task of building a statue nearly twice as tall as any ever built.

The base was made of white marble and the structure was gradually erected as bronze plates were fortified over an iron and stone framework. According to the book of “Pilon of Byzantium”, 15 tons of bronze was used, along with 9 tons of iron, though these numbers seem low to modern architects. Bronze came from another unlikely source. It was decided to fashion the colossus from the bronze weapons of their defeated invaders along with a captured giant enemy siege tower, some nine stories in height which served as the scaffolding of the project. When the statue was finally finished, it was dedicated with a poem: Preserved in Greek anthologies of poetry is what is believed to be genuine dedication text for the Colossus:

To you, o Sun, the people of Dorian Rhodes set up this bronze statue reaching Olympus,

When they had pacified the waves of war and crowned their city with the spoils taken from the enemy. Not only over the seas but also on land did they kindle the lovely torch of freedom and independence. For to the descendants of Herakles belongs dominion over seas and land.

The Colossus of Rhodes was a statue of superhuman proportions. It stood over 107 feet (30 meters) high, making it one of the largest statues in the ancient world; the thigh alone was supposedly 11 feet (3 meters) in width, the ankle 5 feet (1.5 meters) in length.

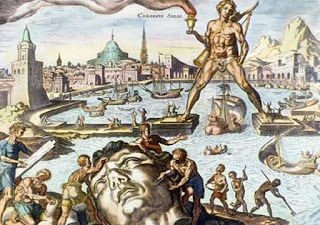

Colossal statues, then and now. Left, illustration of the Colossus of Rhodes in ancient Greece, and right, the Statue of Liberty of the United States of America. (Public Domain)

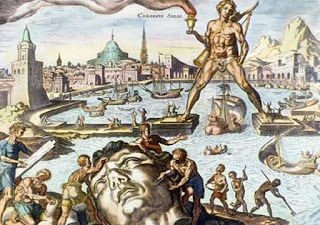

Today, nobody’s exactly sure how the Colossus of Rhodes looked or what its posture was. The only thing for certain is that it did not stand with its legs stretched across the harbor entrance as depicted in many medieval drawings. If the completed statue had straddled the harbor, the entire mouth of the harbor would have been effectively closed during the entirety of the construction.

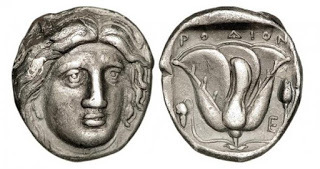

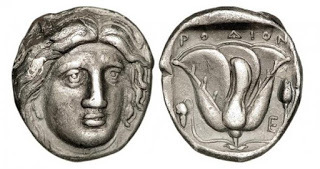

Silver coins from Rhodes circa 316 – 305 AD with Helios represented on one side, a rose on the other. Was this the face of the Colossus of Rhodes? Wikimedia Commons

An idea of what this statue may have looked like comes down through images depicted on a few coins that survived the era. Accounts from eye-witnesses and story-tellers tell of an enormous and amazing statue. Depictions of the time speak of a naked man with a cloak over his left arm or shoulder proudly facing east to the rising sun, torch in one hand, and spear in the other. Some think the statue was wearing a spiked crown, shading its eyes from the rising sun with its right hand, or possibly using that hand to hold the torch aloft in a pose similar to one later given to the Statue of Liberty. Although we do not know the true shape and appearance of the Colossus, modern reconstructions with the statue standing upright are more accurate than older drawings.

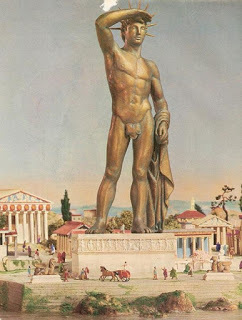

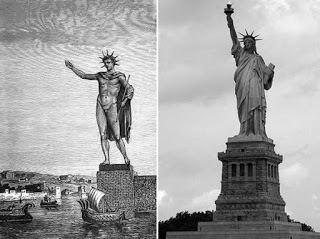

The Colossus of Rhodes, and its possible stance/appearance. Wikimedia Commons

The statue stood for 56 years until the island of Rhodes was hit by an earthquake in 226 BC, destroying much of the city and causing the statue to break off at the knees and topple over into pieces. It is said that the Rhodians received an offer from Ptolemy III Eurgetes of Egypt to cover all restoration costs for the monument but declined. The Rhodians consulted the oracle of Delphi and feared that the statue had somehow offended the god Helios, who used the earthquake to throw it down. Though it lay in ruins on the ground, thousands came and were astounded at the sight of it. Pliny the Elder wrote:

Even as it lies, it excites our wonder and admiration. Few men can clasp the thumb in their arms, and its fingers are larger than most statues. Where the limbs are broken asunder, vast caverns are seen yawning in the interior. Within it, too, are to be seen large masses of rock, by the weight of which the artist steadied it while erecting it.

The statue would go untouched for 900 years or until the Arab invasion of Rhodes in 654. The remains are said to have been melted down to be used as coins, tools, artifacts and weapons. Legend says that a Syrian junk dealer hauled the bits away on nearly 1000 camels. Many believed it impossible to build such a structure with the technology of the time and doubt grew that it ever existed at all. However, in recent years, new evidence has come to light in and around the harbor at Rhodes. Recent archaeological finds have shown that the Colossus stood on the hill overlooking the bay where a medieval castle now stands. Experts found carved stones dating back to the time of the Colossus. These were later used to build a fort that now stands at the entrance to the harbor. It is believed that these were the very stones used to form the base of the giant statue.

The amazing Colossus of Rhodes towers over all others in the annals of the wonders of the ancient world.

Artist's misconception of the Colossus of Rhodes from the 1911 Book of Knowledge. Public Domain

Featured image: Engraving of the Colossus of Rhodes. Paul K / Flickr

By Bryan Hilliard

The Colossus of Rhodes was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and the most ambitious and tallest statue of the Hellenistic period. The last of the seven wonders to be completed, it was a statue built to thank the gods for victory over an invading enemy. Bearing a striking resemblance to the Statue of Liberty in the United States, the Colossus of Rhodes stood for less than sixty years before being destroyed by an earthquake. Some mystery remains as to where it was really located and what happened after it was destroyed.

Since ancient times, the small Greek island of Rhodes has been a main intersection between the Aegean and the Mediterranean seas, and was an important economic center in the ancient world. The capital city, also named Rhodes, was built in 408 BC and was designed to take advantage of the island's best natural harbor on the northern coast. In 357 BC the island was conquered by Mausolus of Halicarnassus but fell into Persian hands in 340 BC and was finally captured by Alexander the Great in 332 BC. In the late fourth century BC, Rhodes allied with Ptolemy I of Egypt against their common enemy, Antigonus I Monophthalmus of Macedonia. In 305 BC, Antigonus sent his son Demetrius to capture and punish the city of Rhodes for its alliance with Egypt. He attacked the island with 40,000 men and weapons and started a war which lasted a year. A relief force of ships sent by Ptolemy arrived in 304 BC, and Antigonus’ army abandoned the siege, leaving behind most of their siege equipment. To celebrate their victory, the Rhodians sold the equipment and decided to use the money to build a huge statue, to their sun god, Helios, called the Colossus of Rhodes. Nearly as tall as the iconic Statue of Liberty built 2,000 years later, the Colossus was also erected as a celebration of freedom.

The Colossus of Rhodes, depicted in this hand-colored engraving, was built about 280 BC. Standing 30 meters (100 feet) high, it was built to guard the entrance to the harbor at Rhodes. The ancient Greeks and Romans considered it to be one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Public Domain

According to Pliny the Elder, a Greek historian who lived several centuries after the Colossus was built, its construction took 12 years and was completed in 280 BC. The pride of the city, the people thought the statue would stand forever. Charles of Lindos was its architect and was given the task of building a statue nearly twice as tall as any ever built.

The base was made of white marble and the structure was gradually erected as bronze plates were fortified over an iron and stone framework. According to the book of “Pilon of Byzantium”, 15 tons of bronze was used, along with 9 tons of iron, though these numbers seem low to modern architects. Bronze came from another unlikely source. It was decided to fashion the colossus from the bronze weapons of their defeated invaders along with a captured giant enemy siege tower, some nine stories in height which served as the scaffolding of the project. When the statue was finally finished, it was dedicated with a poem: Preserved in Greek anthologies of poetry is what is believed to be genuine dedication text for the Colossus:

To you, o Sun, the people of Dorian Rhodes set up this bronze statue reaching Olympus,

When they had pacified the waves of war and crowned their city with the spoils taken from the enemy. Not only over the seas but also on land did they kindle the lovely torch of freedom and independence. For to the descendants of Herakles belongs dominion over seas and land.

The Colossus of Rhodes was a statue of superhuman proportions. It stood over 107 feet (30 meters) high, making it one of the largest statues in the ancient world; the thigh alone was supposedly 11 feet (3 meters) in width, the ankle 5 feet (1.5 meters) in length.

Colossal statues, then and now. Left, illustration of the Colossus of Rhodes in ancient Greece, and right, the Statue of Liberty of the United States of America. (Public Domain)

Today, nobody’s exactly sure how the Colossus of Rhodes looked or what its posture was. The only thing for certain is that it did not stand with its legs stretched across the harbor entrance as depicted in many medieval drawings. If the completed statue had straddled the harbor, the entire mouth of the harbor would have been effectively closed during the entirety of the construction.

Silver coins from Rhodes circa 316 – 305 AD with Helios represented on one side, a rose on the other. Was this the face of the Colossus of Rhodes? Wikimedia Commons

An idea of what this statue may have looked like comes down through images depicted on a few coins that survived the era. Accounts from eye-witnesses and story-tellers tell of an enormous and amazing statue. Depictions of the time speak of a naked man with a cloak over his left arm or shoulder proudly facing east to the rising sun, torch in one hand, and spear in the other. Some think the statue was wearing a spiked crown, shading its eyes from the rising sun with its right hand, or possibly using that hand to hold the torch aloft in a pose similar to one later given to the Statue of Liberty. Although we do not know the true shape and appearance of the Colossus, modern reconstructions with the statue standing upright are more accurate than older drawings.

The Colossus of Rhodes, and its possible stance/appearance. Wikimedia Commons

The statue stood for 56 years until the island of Rhodes was hit by an earthquake in 226 BC, destroying much of the city and causing the statue to break off at the knees and topple over into pieces. It is said that the Rhodians received an offer from Ptolemy III Eurgetes of Egypt to cover all restoration costs for the monument but declined. The Rhodians consulted the oracle of Delphi and feared that the statue had somehow offended the god Helios, who used the earthquake to throw it down. Though it lay in ruins on the ground, thousands came and were astounded at the sight of it. Pliny the Elder wrote:

Even as it lies, it excites our wonder and admiration. Few men can clasp the thumb in their arms, and its fingers are larger than most statues. Where the limbs are broken asunder, vast caverns are seen yawning in the interior. Within it, too, are to be seen large masses of rock, by the weight of which the artist steadied it while erecting it.

The statue would go untouched for 900 years or until the Arab invasion of Rhodes in 654. The remains are said to have been melted down to be used as coins, tools, artifacts and weapons. Legend says that a Syrian junk dealer hauled the bits away on nearly 1000 camels. Many believed it impossible to build such a structure with the technology of the time and doubt grew that it ever existed at all. However, in recent years, new evidence has come to light in and around the harbor at Rhodes. Recent archaeological finds have shown that the Colossus stood on the hill overlooking the bay where a medieval castle now stands. Experts found carved stones dating back to the time of the Colossus. These were later used to build a fort that now stands at the entrance to the harbor. It is believed that these were the very stones used to form the base of the giant statue.

The amazing Colossus of Rhodes towers over all others in the annals of the wonders of the ancient world.

Artist's misconception of the Colossus of Rhodes from the 1911 Book of Knowledge. Public Domain

Featured image: Engraving of the Colossus of Rhodes. Paul K / Flickr

By Bryan Hilliard

Published on November 26, 2017 23:30

9 unsolved historical mysteries

History Extra

1) The Mary Celeste

What became of the crew and passengers of this British-American brigantine remains one of the greatest unsolved mysteries of the sea. The name has since become synonymous worldwide with derelict ‘ghost ships’.

The Mary Celeste was found drifting 400 miles east of the Azores by the crew of another cargo-carrying vessel, the Dei Gratia, on 5 December 1872. The leader of the boarding party told a British board of inquiry at Gibraltar he found the ship was “a thoroughly wet mess”, with possessions left behind and the lifeboat missing.

No trace of Captain Benjamin Spooner Briggs, his wife and their young daughter or the seven experienced crew members has ever been found. Many ingenious theories have been put forward by writers such as Arthur Conan Doyle to explain what happened to them. My favourite comes from a 1965 episode of the BBC series Dr Who, where the frightened crew jump overboard when the Daleks materialise on the ship while chasing the occupants of the TARDIS.

2) Jack the Ripper

The true identity of this Victorian serial killer continues to elude us 126 years after the gruesome killing spree in London’s East End in 1888. In the latest development, an ‘armchair detective’ claims DNA evidence from the shawl of one of the five known victims has identified Polish émigré Aaron Kosminski – one of a list of key suspects – as the man also known as ‘Leather Apron’, or ‘the Whitechapel Murderer’.

A small cottage industry, Ripperology has grown up around the murders with investigators such as Patricia Cornwell and Russell Edwards sifting through surviving evidence in search of a ‘prime suspect.’ Among the wild theories that have become legends is one that depicts Jack as a deranged surgeon who killed the women as part of a conspiracy to protect a member of the royal family.

Professor William Rubinstein describes this story as “palpable nonsense from beginning to end”. He believes it is the very elusiveness of the solution that continues to make the Ripper mystery so attractive to writers and historians.

3) Kenneth Arnold’s ‘flying saucers’

The birth of the modern UFO phenomenon can be traced to a sighting by private pilot Ken Arnold of nine peculiar-shaped flying objects over the Cascade Mountains of Washington on the afternoon of 24 June 1947. Arnold told newsmen the bat-wing shaped objects moved like a saucer would “if you skipped it across the water”. He calculated their speed as faster than the most advanced jet aircraft of that time.

A sub-editor came up with the phrase ‘flying saucers’, and the media coverage that followed triggered off an epidemic for seeing things in the sky that continues to this day. Two weeks after Arnold’s sighting, the US Army Air Force announced that wreckage from a ‘flying disc’ had been recovered from a ranch near Roswell, New Mexico.

A modern myth was born, but ever since controversy has raged about what it was that Arnold actually saw. In my opinion, the most likely explanation is a flock of American white pelicans flying in echelon formation. But no one will ever know for sure.

4) The Devil’s Footprints

Early on the morning of 9 February 1855, people in towns across southern Devon awoke to find a single line of hoof-like marks in the deep snow as if they had been branded with a hot iron. The Times said the marks were found over a distance of 40 miles on both sides of the Exe, as if “some strange and mysterious animal endowed with the power of ubiquity” had created them during the night.

Explanations ranged from an escaped kangaroo, badgers and mice, to a balloon trailing a horseshoe-shaped grappling rope. Superstitious people preferred to believe they were the work of the devil himself. In its summary of the popular theories at the time, a writer in The Illustrated London News said “no satisfactory solution” had been found, and “no known animal could have traversed this extent of country in one night… neither does any known animal walk in a line of single footsteps, not even a man”.

5) The Shroud of Turin

This piece of linen cloth kept in the Cathedral of St John the Baptist in Turin, northern Italy, is one of the most closely investigated objects in human history, yet it retains its secrets. The sacred relic is believed by many Christians to be the shroud in which Jesus of Nazareth was buried.

There is no doubt that it bears a negative imprint of the face and outline of the body of a man who has suffered injuries consistent with crucifixion, but scientists have been unable to reach a consensus about how it was created. Radiocarbon testing by three laboratories in 1988 dated the cloth to the Middle Ages, and this was proclaimed by some as proof it was a medieval fake. But this interpretation remains the subject of intense debate, leading a former editor of Nature, Philip Ball, to declare that the relic remains shrouded in mystery.

6) Richard III and the princes in the Tower

In 2012 the skeleton of the last Plantagenet king of England, Richard III, was unearthed from beneath a council car park on the site of Greyfriars in Leicester city centre. The dig that unearthed his remains was instigated by Philippa Langley of the Richard III Society as a direct result of a “strange feeling” she had when visiting the site.

This apparent example of psychic archaeology is not the only mystery that surrounds Richard’s life and death. His precise role in the fate of his two nephews – popularly known as ‘The princes in the Tower’ – remains a subject of enduring mystery. The 12-year-old Edward and his nine-year-old brother, Richard of Shrewsbury, the sons of King Edward IV, were lodged in the Tower of London by their uncle, Richard, at the time of their disappearance in 1483.

No one knows exactly what happened to them, but a box containing two small human skeletons was found near the White Tower in the 17th century and, at the time, was widely believed to be the remains of the princes.

7) The Solway Spaceman

On the afternoon of 23 May 1964, an employee of the Cumbrian fire service, Jim Templeton, took photographs of his wife and daughter during a day out at a local beauty spot on the Solway Firth. When he collected the photographs from a chemist, the assistant told him it was a shame one was “spoiled by the man in the background wearing a space suit”.

Sure enough, one image of his youngest daughter Elizabeth clearly shows an enigmatic ‘figure’ floating behind her head. The ‘spaceman’ is dressed in a white suit that resembles those worn by NASA astronauts at the time.

The photograph was examined by Kodak and scrutinised by detectives from the Cumbrian police, who were unable to explain it. Jim Templeton died in 2011 without learning the true identity of the ‘Solway spaceman’. The image remains one of the most perplexing in the history of anomalous photography.

8) Mothman

One dark night in November 1966, four American teenagers claimed they saw a huge bird-like monster with glowing red eyes while cruising along a back road near Point Pleasant in rural West Virginia. They claimed it rose into the air, unfolded its bat-like wings, and pursued them as they sped away in terror. The next morning the sheriff’s office held a press conference, and the media dubbed the creature ‘Mothman’ after the Batman series that was showing on TV.

Encounters with the demonic ‘bird’ inspired the 2002 movie The Mothman Prophecies, directed by Mark Pellington. The film was based upon journalist John Keel’s book that chronicled an outbreak of uncanny experiences in the Ohio Valley. He believed the creature was linked in some mysterious way with the collapse of the Silver Bridge in Point Pleasant in December 1967 that killed 46 people, including some mothman witnesses.

9) Monsters of the Deep

Do the depths of our oceans hide undiscovered species of animal such as the great ‘sea serpent’ that was sighted by the captain and crew of HMS Daedalus near the island of St Helena in 1848?

Among the files at the National Archives and the Natural History Museum I found first-hand reports of similar creatures in records from the late 19th to the early 20th century, including one by Arthur Conan Doyle, author of The Lost World. Could it be that, as the museum’s former keeper of zoology, William Calman, told a puzzled witness in 1929: “…we are not so rash as to suppose that we yet know all of the inhabitants of the sea and it is within the bounds of possibility that you saw some animal that has never been captured or described”.

If so, where have they all gone?

Dr David Clarke is the author of Britain’s X-traordinary Files (Bloomsbury 2014).

Published on November 26, 2017 00:30

November 25, 2017

A Succinct Timeline of Roman Emperors—400 Years of Power Condensed

Ancient Origins

To say that the Roman Empire had its ups and downs would be the understatement of all understatements. No “nation” was more abruptly destabilized or even more abruptly stabilized than that of ancient Rome…perhaps with the exception of the United States.

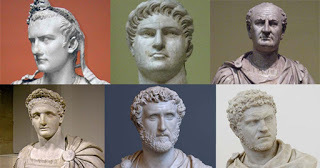

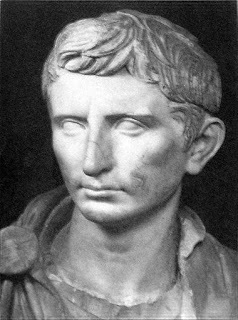

Following the events of the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, Octavian, adopted son of the first dictator Julius Caesar, took over sole power of Rome and all her provinces. It was in this moment that the Republic officially transformed into the Empire. Octavian—renamed Augustus at the beginning of the new Principate—ruled for forty years before his death. The heir he secured was his adopted son Tiberius, though unfortunately Tiberius’ reluctance to rule as Emperor was not well-hidden. For the length of his reign—though he was respected—Tiberius attempted to let the Senate lead the affairs of the state.

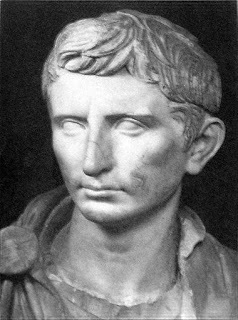

A statue of Augustus as a younger Octavian, dated ca. 30 BC. (Public Domain)

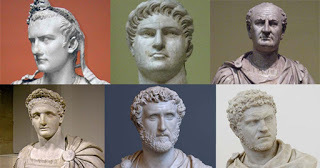

The Dynasty Augustus: Caligula, Claudius, and Nero

Following Tiberius was his great nephew Caligula who ruled for just under four years. His sadistic leadership and essential emptying of the city’s treasuries—coupled, of course, with his overtly immoral sexual tendencies, led to a swift assassination. Caligula’s uncle Claudius was handed the Empire next, as the Senate was forced to make a quick decision when Caligula left no heir. (Or rather, his assassin left no living heir.)

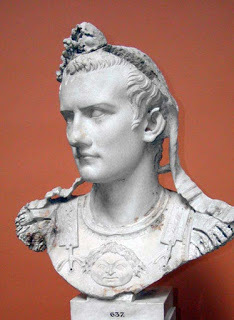

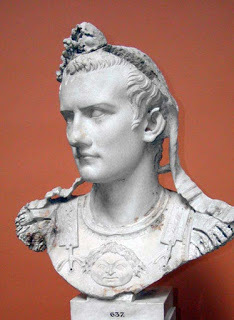

Emperor Caligula. (CC BY SA 3.0)

Claudius’ leadership was filled with compassion and expansion. Caligula’s conspirators were pardoned, supposedly for the prevention of another assassination, while Claudius led his army the furthest into Britain they had ever been. Under Claudius, the first proper Roman colonia was founded at modern Colchester.

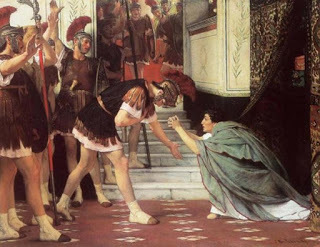

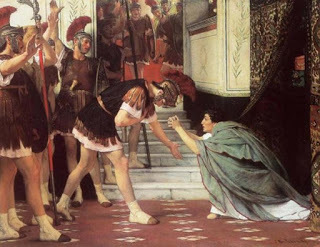

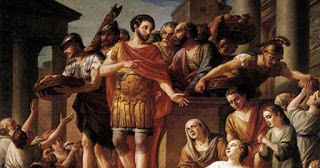

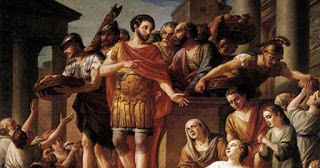

Proclaiming Claudius Emperor. (1867) By Lawrence Alma-Tadema. In one version of the tale of Claudius’ rise as the Emperor of Rome the Praetorian Guard found him hiding behind a curtain after Caligula’s death and proclaimed him as the emperor. (Public Domain)

This dynasty, however, would not last much longer. Poisoned (supposedly) by his own wife, Claudius was succeeded by his stepson, the infamous Emperor Nero. This emperor who spent an extraordinary amount of money on a Golden House, squashed the revolt of Queen Boudicca in Brittania, and purportedly played the fiddle while Rome burned around him, would last (rather surprisingly) for thirteen years as Rome’s leader. His death, a suicide influenced by the likelihood of assassination, brought an abrupt and fierce end to the dynasty Augustus attempted to create, and would pave the way for extensive Senatorial consideration about the benefits and pitfalls of blood-lineages.

A plaster bust of Nero, Pushkin Museum, Moscow. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Flavian Dynasty: Vespasian and his Sons

After Nero’s death, the power of the Principate was left without an owner. Thus followed the year of the Four Emperors—Galba, Otho, and Vitellus—eventually ending in the success of military general Vespasian as the new leader of the Roman people. Vespasian's rule and that of his two sons, Titus and Domitian, was riddled with military victory. The borders of Rome expanded, and powerful strides were made both in the eastern and western parts of the Empire. Vespasian rebuilt much of the city, including beginning the transformation of Nero's Domus Aurea into the renowned Colosseum.

Vespasian. Plaster cast in Pushkin museum after original in Louvre. (Sariling gawa/CC BY SA 3.0)

Meanwhile, Titus’ two-year leadership—though proceeded by a valiant triumph over Judea—was predominately spent dealing with the greatest natural disaster of the Roman world: the explosion of Vesuvius in 79 AD. It is a shame that Vespasian and Titus’ stable reigns ended when Vespasian’s younger son ascended in only 81 AD. Domitian, unfortunately for both the Roman people and the Flavian name, drove a wedge between the Senate and the army, in part because of the lavish paychecks he gave his soldiers. His assassination brought the Flavian dynasty to a screeching halt.

Bust of Roman emperor Domitianus. Antique head, body added in the 18th century. Musée du Louvre (Ma 1264), Paris. Formerly in the Albani Collection in Rome. (Sailko/CC BY SA 3.0)

Nerva, Trajan, and Hadrian - The Nervan end of the Nervan-Antonine Dynasty

The Nervan-Antonine dynasty rose next—Nerva, the first namesake of the lineage, a friend of Domitian's and, more importantly, of the Senate. This dynasty was the first that purposely attempted to name successors outside the family. For the first few generations, this succeeded (in part due to a lack of heirs). Yet it also appears that the Senate’s belief that empires suffered under blood dynasties rule was accurate. While this peace would not last, the Roman Empire had almost one hundred years of more politically and mentally stable rulers.

Bronze statue of emperor Nerva, Forum of Nerva, Rome. (Carole Raddato/CC BY SA 2.0)

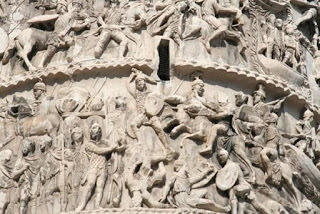

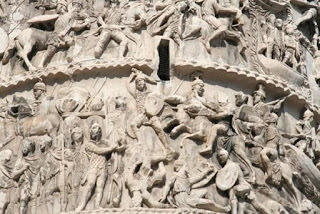

Under Nerva, the army and the Senate—the two "bodies" with the most power—ceased the feud caused by Domitian. His successor, Trajan, would surpass him after two years, not only in length of rulership, but in military deeds and civic duty. Best remembered for his double defeat of the Dacians in 101-102 and 105-106 AD, Trajan brought order and calm to the regions of modern day Romania for the first time. Trajan was then able to focus his attentions on public building projects, such as the Forum.

Statue of Roman Emperor Trajan at Tower Hill, London. (CC BY SA 3.0)

Hadrian, leader from Trajan's death in 117 until 138, quickly became another favored ruler. His philhellenism—love for all things Greek—would benefit his time as Emperor as he incorporated Greek art and architecture into Roman building projects and encouraged the study of the Greek language and academics (i.e., philosophy, literature, etc.). Hadrian also furthered the boundaries of the Empire to northern Britain (culminating in the construction of Hadrian's Wall), and later to Judea in the east.

The view along Hadrian's Wall towards Housesteads Roman Fort. (CC BY-NC 2.0 )

The Antonine Part of the Nervan-Antonine Dynasty: Antoninus Pius, Lucius Verus, and Marcus Aurelius

Antoninus Pius followed Hadrian from 138-161 AD and continued the trend of stable leadership. Though he was known for appreciating the more luxurious side of court life, Antoninus' time as emperor is positively remembered for its lack of documented military victories or defeats under Antoninus directly. Any provincial disruptions were handled predominately by the governors of the various regions and generals of the Roman army, additional powers granted by Antoninus as needed. Antoninus was more concerned, it seems, with improving Rome proper. On his death, Marcus Aurelius was left as heir, ruling jointly with Lucius Verus from 161 until Verus' death in 169.

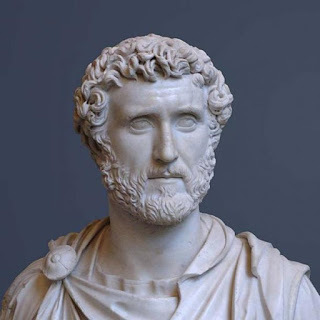

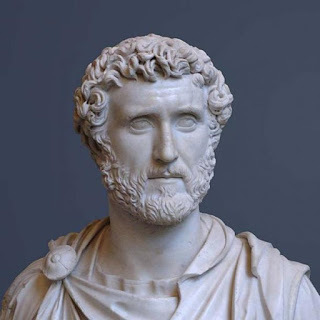

Bust of Antoninus Pius, circa 150 AD. ( Public Domain )

The philosopher-king of the Empire, Marcus Aurelius ruled as an intellect rather than a general. While his reign saw numerous victories against eastern and northern enemies, Marcus himself focused on stepping away from Antoninus' lavish preferences and putting more emphasis on personally responding to the people. Thus, when his legitimate son Commodus came to sole power in 181 AD, Rome was shaken by the increasingly unstable and reckless behavior. Within just over ten years, Commodus was assassinated in his bath.

Marcus Aurelius Distributing Bread to the People ( Public Domain )

The Year of the Five Emperors

The Year of the Five Emperors followed Commodus' untimely death, as distressing as the Year of the Four Emperors a hundred years prior. Once again, men attempted to gain power backed by their individual armies. In essence, there was more than one "declared" emperor at any given time of the year 193 AD.