MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 33

January 17, 2018

The Last Civil War of the Roman Republic

Made from History

The Roman Republic ended in war. Octavian, Julius Caesar’s anointed heir, defeated Antony and his lover Cleopatra, the queen of Egypt, to rise to unchallenged power as Augustus, the first Roman Emperor. He ended a long cycle of internal conflict in the Roman world, a territory that Julius Caesar had realised was too big to be ruled by its old institutions.

Caesar Leaves a Messy Inheritance

Julius Caesar’s extraordinary personal power was the prime motive for his assassins, who wanted to revive the power of the Senate in Roman politics. However, the dictator had been enormously popular, and the aristocratic plotters who killed him would soon be faced by men ready to fight to take his place.

Antony was Caesar’s man for years. He was his deputy when he crossed the Rubicon River into Italy in 49 BC to trigger the civil war with Pompey, and was his co-Consul when he died. He was powerful and popular with lots of military experience.

Octavian was Caesar’s great-nephew and had been named as his heir and adopted son in a will made two years before Caesar died. He had proved effective in his short military career, and his links to Caesar gave him instant popularity, particularly with the army. He was only 19 when Caesar died and away from Rome, but would not stay so for long.

After putting down revolts in support of Caesar’s assassins, Octavian and Antony ruled as part of a Triumvirate with Lepidus until 36 BC, when they took joint power, splitting the Empire into Octavian’s West and Antony’s East.

Swords Drawn: Octavian vs. Antony

Just two years later, Antony went too far when he struck a deal with Cleopatra, his lover, that handed Roman territory in Egypt to her and the son she had borne Caesar during her long affair with the Roman leader.

Octavian’s sister was Antony’s wife, and he’d already publicised his adultery. When Antony married Cleopatra in 32 BC and seemed on the verge of setting up an alternative Imperial capital in Egypt, Octavian persuaded the Senate to declare war on Cleopatra, who they blamed for seducing their former hero. As Octavian had foreseen, Antony backed Cleopatra, decisively cutting his ties with Rome and Octavian set off with 200,000 legionaries to punish the renegade pair.

The war was won in one decisive sea battle, off Actium in Greece. Octavian’s fleet of smaller, faster vessels with more experienced crews devastated Antony’s ships and his army surrendered without doing battle.

Antony fled with Cleopatra to Alexandria while Octavian plotted his next move.

He marched to Egypt, cementing the support of legions and Roman client kingdoms along the way. Antony was massively outnumbered, with around 10,000 men at his command who were quickly defeated by one of Octavian’s allies as most of the remainder of Antony’s forces surrendered.

The Lovers’ Suicides of Antony and Cleopatra

With no hope left, Antony messily killed himself on 1 August 30 BC, after apparently failing to strike a deal to protect Cleopatra.

Cleopatra then attempted to secure a deal for herself and Caesar’s son, Caesarion, but Octavian refused to listen, having the young man killed as he fled and warning his mother that she would be paraded in his triumph back in Rome.

Octavian was desperate to keep Cleopatra alive. He wanted a high-status prisoner, and her treasure to pay his troops. Cleopatra was able to kill herself though – possibly using a poisoned snake.

Nothing now stood between Octavian and total power. Egypt was granted to him as his personal possession and by 27 BC the granting of the titles Augustus and Princeps confirmed him as Emperor.

Telling the Tale

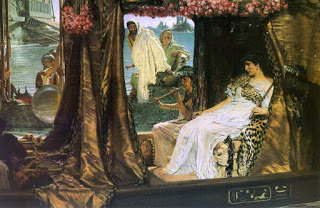

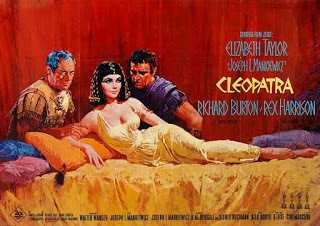

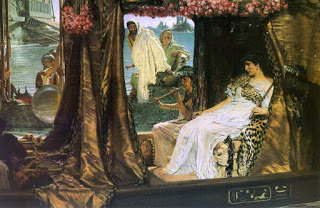

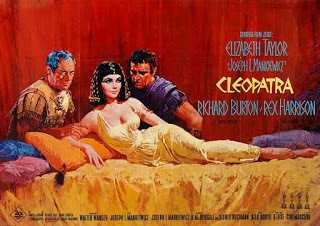

The story of Antony and Cleopatra – the great Roman and the beautiful queen who caused him to turn his back on his nation – is compelling.

Romans and Egyptian no doubt told the tale many times and one surviving account has proved the most durable. Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans was published in the late 1st century, pairing men from both civilisations.

Antony was paired with Demetrius, the king of Macedonia who died in enemy captivity and spent many years with a courtesan as his companion.

Plutarch was interested in character rather than history and his book was a defining text of the rediscovery of classical civilisation during the Renaissance. Among its most devoted readers was one William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra is a fairly faithful telling of the tale, going so far as to lift some phrases directly from Sir Thomas North’s translation of Plutarch’s work.

Antony and Cleopatra would both be remembered by history as great public figures, but their love story – no matter how embellished – has taken them into different territory. Both, and Cleopatra in particular, have been portrayed in literature, film, dance and every other medium of art countless times. By Colin Ricketts Colin Ricketts studied history at the University of Birmingham, graduating in 1992. He's a qualified librarian, a former journalist and currently a freelance writer and editor.

The Roman Republic ended in war. Octavian, Julius Caesar’s anointed heir, defeated Antony and his lover Cleopatra, the queen of Egypt, to rise to unchallenged power as Augustus, the first Roman Emperor. He ended a long cycle of internal conflict in the Roman world, a territory that Julius Caesar had realised was too big to be ruled by its old institutions.

Caesar Leaves a Messy Inheritance

Julius Caesar’s extraordinary personal power was the prime motive for his assassins, who wanted to revive the power of the Senate in Roman politics. However, the dictator had been enormously popular, and the aristocratic plotters who killed him would soon be faced by men ready to fight to take his place.

Antony was Caesar’s man for years. He was his deputy when he crossed the Rubicon River into Italy in 49 BC to trigger the civil war with Pompey, and was his co-Consul when he died. He was powerful and popular with lots of military experience.

Octavian was Caesar’s great-nephew and had been named as his heir and adopted son in a will made two years before Caesar died. He had proved effective in his short military career, and his links to Caesar gave him instant popularity, particularly with the army. He was only 19 when Caesar died and away from Rome, but would not stay so for long.

After putting down revolts in support of Caesar’s assassins, Octavian and Antony ruled as part of a Triumvirate with Lepidus until 36 BC, when they took joint power, splitting the Empire into Octavian’s West and Antony’s East.

Swords Drawn: Octavian vs. Antony

Just two years later, Antony went too far when he struck a deal with Cleopatra, his lover, that handed Roman territory in Egypt to her and the son she had borne Caesar during her long affair with the Roman leader.

Octavian’s sister was Antony’s wife, and he’d already publicised his adultery. When Antony married Cleopatra in 32 BC and seemed on the verge of setting up an alternative Imperial capital in Egypt, Octavian persuaded the Senate to declare war on Cleopatra, who they blamed for seducing their former hero. As Octavian had foreseen, Antony backed Cleopatra, decisively cutting his ties with Rome and Octavian set off with 200,000 legionaries to punish the renegade pair.

The war was won in one decisive sea battle, off Actium in Greece. Octavian’s fleet of smaller, faster vessels with more experienced crews devastated Antony’s ships and his army surrendered without doing battle.

Antony fled with Cleopatra to Alexandria while Octavian plotted his next move.

He marched to Egypt, cementing the support of legions and Roman client kingdoms along the way. Antony was massively outnumbered, with around 10,000 men at his command who were quickly defeated by one of Octavian’s allies as most of the remainder of Antony’s forces surrendered.

The Lovers’ Suicides of Antony and Cleopatra

With no hope left, Antony messily killed himself on 1 August 30 BC, after apparently failing to strike a deal to protect Cleopatra.

Cleopatra then attempted to secure a deal for herself and Caesar’s son, Caesarion, but Octavian refused to listen, having the young man killed as he fled and warning his mother that she would be paraded in his triumph back in Rome.

Octavian was desperate to keep Cleopatra alive. He wanted a high-status prisoner, and her treasure to pay his troops. Cleopatra was able to kill herself though – possibly using a poisoned snake.

Nothing now stood between Octavian and total power. Egypt was granted to him as his personal possession and by 27 BC the granting of the titles Augustus and Princeps confirmed him as Emperor.

Telling the Tale

The story of Antony and Cleopatra – the great Roman and the beautiful queen who caused him to turn his back on his nation – is compelling.

Romans and Egyptian no doubt told the tale many times and one surviving account has proved the most durable. Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans was published in the late 1st century, pairing men from both civilisations.

Antony was paired with Demetrius, the king of Macedonia who died in enemy captivity and spent many years with a courtesan as his companion.

Plutarch was interested in character rather than history and his book was a defining text of the rediscovery of classical civilisation during the Renaissance. Among its most devoted readers was one William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra is a fairly faithful telling of the tale, going so far as to lift some phrases directly from Sir Thomas North’s translation of Plutarch’s work.

Antony and Cleopatra would both be remembered by history as great public figures, but their love story – no matter how embellished – has taken them into different territory. Both, and Cleopatra in particular, have been portrayed in literature, film, dance and every other medium of art countless times. By Colin Ricketts Colin Ricketts studied history at the University of Birmingham, graduating in 1992. He's a qualified librarian, a former journalist and currently a freelance writer and editor.

Published on January 17, 2018 23:00

Why Did the Wars of the Roses Start?

A watercolour recreation of the Wars of the Roses.

What Caused the War?

In the simplest terms, the war began because Richard, Duke of York, believed he had a better claim to the throne than the man sitting on it, Henry VI.

Ever since Henry II, the first Plantagenet, took power, Kings had been holding onto their crown by the skin of their teeth and not all of them succeeded. Edward II, for example, was ousted by his wife and replaced by his son Edward III, but at least this kept things in the family.

Problems occurred in 1399 when Richard II was deposed by his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke who would go on to be the Henry IV. This created two competing lines of the family, both of which thought they had the rightful claim. On the one hand were the descendants of Henry IV – known as the Lancastrians – and on the other the heirs of Richard II. In the 1450s, the leader of this family was Richard of York and his followers would come to be known as the Yorkists.

A Dodgy King However, all this dynastic arguing was something of a smokescreen. What really mattered were more practical issues and in particular the disappointing reign of Henry VI.

A portrait of the ailing Henry VI whose inability to rule effectively due to his illness contributed to the outbreak of the Wars of the Roses

When he became king Henry was in an incredible position. Thanks to the military successes of his father, Henry V, he held vast swathes of France and was the only King of England to be crowned King of France and England. However it was not a title he could hold onto for long and over the course of his reign he gradually lost almost all England’s possessions in France.

Finally, in 1453, defeat at the Battle of Castillion called an end to the hundred years war and left England with only Calais from all their French possessions.

The nobles were not happy, but this was as nothing to Henry’s reaction. He had always had a fragile mind and in 1453 it broke. Historians believe he suffered from a condition known as catatonic Schizophrenia which would see him lapse into catatonic states for long periods of time.

Battle for Power

Henry’s weakness created two factions at court. One, led by the Duke of Gloucester and Richard, Duke of York favoured a more aggressive policy in the war, while the other led by the Dukes of Suffolk and Somerset favoured peace. They were supported by the Queen Margaret of Anjou who was rumoured to be having an affair with Somerset.

With Henry in no fit state to rule, Richard was named Regent. Although he relinquished when Henry recovered it had given him a taste for power and this alerted Margaret. She sensed a threat from Richard and did everything she could to force him out of power.

The two sides met in the Battle of St Albans. It was only a small skirmish, but it saw the death of the Duke of Somerset and several other Lancastrian noblemen. This created sons who were out for revenge and turned a dynastic struggle into an even more poisonous blood feud.

Even then there were chances to turn back. The Act of Accord in 1460 named Richard heir, but there was no turning back. Margaret – perhaps grieving for Somerset – was determined to get her revenge on Richard. She would have it when he himself was killed in battle, but that only left his son Edward who was even more determined to get his revenge. The Wars of York and Lancaster had begun.

By Tom Cropper

Tom is a freelance journalist who studied history at Essex University. His work can be found in many different publications focusing on business and politics.

Published on January 17, 2018 00:30

January 15, 2018

10 Facts About Medieval Kings

Made from History

Rumours about Richard I’s sexuality have persisted since his death.

In the Middle Ages England was ruled by 8 kings and 1 queen. Each had their triumphs and failures — as well as secrets. Their lives continue to provide fodder for the imagination and their names remind us of times long gone. But how do we separate truth from fiction? As a start, here are 10 facts about the medieval kings of England.

1. A soldier named Owen founded the Tudors

We know them as the most famous and powerful of our Royal dynasties, but they had somewhat scandalous beginnings. In the 1420s a soldier and courtier Owen Tudor entered the service of the Queen Catherine of Valois after the death of her husband Henry. She was having a hard time finding a replacement husband as the government quashed almost all of her attempts. At some point she decided to elope with Owen. The marriage was later given legitimacy by Henry VI, and so the Tudor bandwagon was on the way.

2. Richard I was possibly homosexual

The symbol of a red blooded English King may actually have been a homosexual. There is evidence which suggests Richard I met his Queen Berrengaria while involved in a relationship with her brother.

3. Plantagenet isn’t a real name

The Plantagenets ruled England for hundreds of years, but it was not their real name. They were in fact the Angevins or counts of Anjou. Plantagenet was a nickname earned by Geoffrey of Anjou for a plant which he often wore.

4. Many English kings lost their throne

While the power of the French King was absolute, English Kings knew that they could all too easily be shifted from power. Edward II and Richard II were all forced from power while Henry II faced rebellions from his own children and King John was struggling to regain his throne when he died of dysentery.

5. Three medieval kings died in battle

They were Harold Godwinson, Richard I and Richard III.

6. Richard the Lionheart was killed by a chef

A picture of the death of Richard I. We think of Richard I as a great rampaging warrior of the middle ages, but he met an ignominious end. While returning to England he laid siege to a small castle hoping for some booty. However, a chef on the battlements spotted the King, grabbed a crossbow and killed him.

7. There were four hopefuls for the Crown in 1066

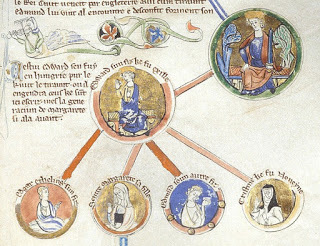

A family tree depicting the descent of Edgar the Aetheling.

We generally only think of Harold, William and the Hardrada as being claimants for the throne in 1066. However, there was another one. Edgar Aetheling was the closest relative to Edward the Confessor and actually had a pretty good case. However, he didn’t have much support so few people took much notice of him.

8. Louis I was a King of England

We believe the last time we were invaded was 1066. This is not true – we’ve actually been invaded many, many times. In 1216, Prince Louis of France invaded England and took control of London and reigned as King Louis I for almost a year. He was eventually beaten back and forced to beat a path back to France.

9. Richard the Lionheart Hated England

Richard the Lionheart would have sold England if he had the chance.

We all think of him as a great hero King, but not only could he not speak the language, he even said he’d have sold the entire country off if only he could find a buyer.

10. England had a second Interregnum

Simon de Montfort who captured a King and briefly ruled England. We all know about Oliver Cromwell and the Interregnum but something similar happened much earlier. In 1264 Simon de Montfort rebelled against Henry III and won a resounding victory at the Battle of Lewes. He began setting up a new government and parliament, but his success was short lived. In 1265 Henry’s son Edward escaped captivity, rallied an army and defeated Simon.

By Tom Cropper

Tom is a freelance journalist who studied history at Essex University. His work can be found in many different publications focusing on business and politics.

Published on January 15, 2018 23:30

January 14, 2018

The global origins of the Boston Tea Party

History Extra

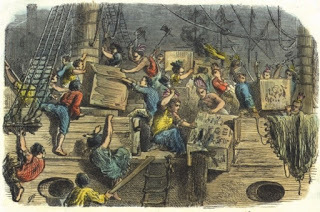

Trouble brewing: This illustration shows “Boston boys throwing tea into the harbour” on 16 December 1773. The protestors revelled in the opportunity to make a bold statement that would be felt across the world. (Getty images)

About a hundred men boarded three ships in Boston harbour on the evening of 16 December 1773. No one knows for sure who they were, or exactly how many of them were there. They had wrapped blankets around their shoulders, and they had slathered paint and soot on their faces. A newspaper report called them “resolute men (dressed like Mohawks or Indians)”. In two or three hours, they hoisted 340 chests above decks, chopped them open with hatchets, and emptied their contents over the rails. Since the tide was out, you could see huge clumps of the stuff piling up alongside the ships.

This was in fact 46 tonnes of tea worth more than £9,659. At the time, a tonne of tea cost about the same as a two-storey house. The event became a pivotal moment in American history, leading to the overthrow of the British imperial government, an eight-year civil war, and American independence.

Yet the history of the Boston Tea Party belongs not just to the United States of America, but to the world. The Tea Party originated with a Chinese commodity, a British financial crisis, imperialism in India, and American consumption habits. It resounded in a world of Afro-Caribbean slavery, Native American disguises, and widespread tyranny and oppression. And for over 200 years since, the Boston Tea Party has inspired political movements of all stripes, well beyond America’s shores.

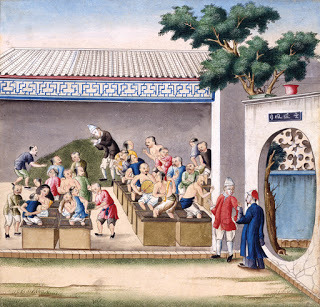

To understand why tea had become so controversial in Boston, we would have to look at the history of how this plant had come to be embraced by Britons all over the world. Camellia sinensis grew among the foothills of the high mountains that separated China from the Indian subcontinent. For over a thousand years, it was the Chinese who had popularised and marketed the drink. Chinese merchants traded tea to Japanese ships, Mongol horsemen, and Persian caravans. Few Europeans had tasted tea before 1680. Yet by the 18th century, trading firms like the English East India Company were regularly negotiating with Cantonese hongs (merchants) and hoppos (port supervisors) to bring tea back to the west. As the tea trade grew, the price dropped.

Tea for two : A fashionable gentleman takes morning tea with a lady in her boudoir, while a maidservant looks on, in an 18th-century engraving. (Wellcome Collection)

The bitter taste of tea might have been unpalatable to Europeans, had it not been for the trade in another commodity – sugar. The 17th century had seen the cultivation of sugarcane in the West Indies yield an enormously profitable crop. To raise cane and process sugar, West Indian planters relied on the labour of African slaves. Britons did not organise an objection to slavery, sugar and tea until the end of the 18th century. In the meantime, tea and sugar went hand in hand.

Tea made its way to American ports like Boston, Massachusetts, and even into the outermost reaches of the American frontier. Some of it was legally bought, and the rest was smuggled to avoid British duties. It soon became the drink of respectable households all over the British empire, although it also pained critics who worried about its corrupting effects. They lamented that tea led to vanity and pride, it encouraged women to gather and gossip, and it threatened to undermine the nation. Nevertheless, the British government, reliant on the revenues from global trade, did nothing to stand in the way of tea drinkers. Indeed, in 1767, parliament passed a Revenue Act that collected a duty on all tea shipped to the American colonies.

These were years when Great Britain, still groaning under the debts incurred during the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), began tightening the reins on its imperial possessions all over the globe. In America, this meant restrictions on westward expansion, stronger enforcement of customs regulations, and new taxes. In India, this meant increased control over the East India Company.

The employees of the East India Company were not just traders in tea and textiles. Since the reign of Elizabeth I, the company had also been fortifying, making allies, and fighting rivals in the lands east of the Cape of Good Hope. It had a monopoly on the eastern trade, and its role took an imperial turn in the 1750s. Eight years after Robert Clive defeated the Nawab of Bengal at the battle of Plassey in 1757, he arranged to have the company assume the civil administration (and tax collection) in Bengal.

General clamour

Many Britons had high hopes for this new source of revenue but then, in the autumn of 1769, Indian affairs took a horrific turn. A famine struck Bengal, killing at least 1.2 million people – this was equivalent to half the population of the 13 American colonies at the time. A horrified British public blamed the East India Company for the disaster. “The oppressions of India,” wrote Horace Walpole, “under the rapine and cruelties of the servants of the company, had now reached England, and created general clamour here.”

The East India Company’s troubles multiplied. In 1772, manipulations of its stock were blamed for a series of bank failures that sent a shockwave of bankruptcies across the globe. The company was losing money on its military ventures in India. The Bank of England refused to keep lending it money, and it owed hundreds of thousands of pounds in back taxes. What’s more, competition from smugglers and excessive imports led the company to amass 17.5 million pounds of tea in its warehouses – more than the English nation drank in a year.

This 18th-century watercolour shows workers crushing tea in wooden crates in China, where the drink was first marketed and popularised. (Credit: V&A)

To rescue the company (and gain greater control over it), parliament passed a series of laws in 1773, including the Tea Act. This law levied no new taxes on Americans, but it allowed the company to ship its tea directly to America for the first time. The legislation, Americans feared, would have three effects. First, it granted a monopoly company special privileges in America, cutting out American merchants (except a few hand-picked consignees). Second, it encouraged further payment of a tax that the Americans had been decrying for six years. Third, the revenue from the tax was used to pay the salaries of certain civil officials (including the Massachusetts governor), leaving them unaccountable to the people.

Americans were vitriolic in their response, and their pamphlets resounded in global language. “Hampden”, a New York writer, warned that the East India Company was “lost to all the Feelings of Humanity” as they “monopolised the absolute Necessaries of Life in India, at a Time of apprehended Scarcity”. The new tea trade, he warned, would “support the Tyranny of the [Company] in the East, enslave the West, and prepare us fit Victims for the Exercise of that horrid Inhumanity they have… practised, in the Face of the Sun, on the helpless Asiaticks”. John Dickinson, a Pennsylvania lawyer who gained fame as a protestor against British taxes, similarly attacked the East India Company. “Their Conduct in Asia, for some Years past, has given ample Proof, how little they regard the Laws of Nations, the Rights, Liberties, or Lives of Men.”

Having drained Bengal of its wealth, he wrote, they now “cast their Eyes on America, as a new Theatre, wheron to exercise their Talents of Rapine, Oppression and Cruelty. The Monopoly of Tea, is, I dare say, but a small Part of the Plan they have formed to strip us of our Property. But thank GOD, we are not Sea Poys, or Marattas, but British Subjects, who are born to Liberty, who know its Worth, and who prize it high.”

Bostonians responded to these warnings. Under pressure from the Sons of Liberty (a group of American patriots) in New York and Philadelphia, they threatened Boston’s consignees until they fled the town. When the first of the tea ships arrived on 28 November 1773, the Bostonians demanded that the cargo be returned to London without unloading. The owner, a Quaker merchant named Francis Rotch, protested that he couldn’t do this, by law, and so a stalemate of almost three weeks ensued. Upon the stroke of midnight on 17 December, the British customs service would have the power to step in, seize the tea, and sell it at auction.

Derided as savages

Therefore, the evening before, on 16 December, the Bostonians got their Indian disguises ready. These were crude costumes, not meant to conceal so much as warn the community not to reveal the perpetrators’ identities. Yet the choice of a Native American disguise was still significant. Americans were often portrayed as American Indians in British cartoons, and the colonists were often lumped in with the indigenous population and derided as savages. What better way to blunt the sting of this epithet than to assume an Indian disguise?

The Bostonians may have been inspired by a New York City newspaper piece in which “The MOHAWKS” wrote that they were “determined not to be enslaved, by any power on earth,” and promised “an unwelcome visit” to anyone who should land tea on American shores. The tea destroyers of Boston selected a costume that situated them on the other side of the Atlantic ocean from the king and parliament. They were beginning to think of themselves as Americans rather than British subjects, as free men throwing off the shackles of empire.

Although most of the tea destroyers were born in Massachusetts, some had more far-flung origins. James Swan, an anti-slavery pamphleteer, was born in Fifeshire, Scotland. Nicholas Campbell hailed from the island of Malta. John Peters had come to America from Lisbon. Although there were wealthy merchants and professionals among the destroyers, the bulk of them were craftsmen who worked with their hands, which enabled them to haul the chests of tea to the decks in a short time. Mostly young men between the ages of 18 and 29, they were thrilled to make a bold statement to the world.

And the world responded. Prints of the Boston Tea Party appeared in France and Germany. In Edinburgh, the philosopher Adam Smith shook his head disapprovingly at the “strange absurdity” of the East India Company’s sovereignty in India. He stitched his ideas together into a foundational theory of free market capitalism in 1776. A Persian historian in Calcutta would write in the 1780s that the British-American conflict “arose from this event: the king of the English maintained these five or six years past, a contest with the people of America (a word that signifies a new world), on account of the [East India] Company’s concerns.” Many years later, activists from China to South Africa to Lebanon would explain their actions by comparing them to the Tea Party. As a symbol of anti-colonial nationalism, non-violent civil disobedience, or costumed political spectacle, the Tea Party was irresistible.

In 1773, the diplomat Sir George Macartney waxed poetic about Great Britain, “this vast empire, on which the sun never sets, and whose bounds nature has not yet ascertained”. Bostonians tested those bounds later that year. The Boston Tea Party is often spun as the opening act in the origin story of the United States. Yet it is better understood as a bright conflagration on the horizon of a big world – a fire that still burns brightly.

Timeline: From Tea Party to independence

16 December 1773 Protesters dump 340 crates of the East India Company’s tea into Boston harbour

January 1774 London learns of the destruction of the tea, and of other American protests

March 1774 Parliament passes the first of the so-called Coerciver Acts, the Boston Port Act, which closes the port of Boston until the town makes restitution for the tea

May 1774 Parliament passes two more laws for restoring order in Massachusetts. These laws limit town meetings, put the provincial council under royal appointments, and allow British civil officers accused of capital crimes to move their trials to other jurisdictions

1 June 1774 The Boston Port Act takes effect, and Governor Thomas Hutchinson departs for England, never to return. His replacement is General Thomas Gage, a military commander

Summer 1774 Massachusetts protesters resist the Coercive Acts by disrupting local courts and forcing councillors to resign their seats

September to October 1774 The First Continental Congress meets, declares opposition to the Coercive Acts, and calls for boycotts of British goods and an embargo on exports to Great Britain

February 1775 Parliament declares Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion. Governor Gage will later receive orders to enforce the Coercive Acts and suppress the uprising

19 April 1775 British regular troops and Massachusetts militiamen exchange fire at Lexington and Concord. In response, armed New Englanders surround the British fortifications at Boston

March 1776 American forces take Dorchester Heights and the British evacuate Boston

July 1776 The Continental Congress adopts the Declaration of Independence of the United States

The global legacy of the Tea Party

More than two centuries after it took place, campaigners around the world are still inspired by the Boston Tea Party as a model of peaceful protest

Temperance movement

During the 19th century, Americans periodically drew upon the Boston Tea Party as a precedent for democratic protests: labour unions, the Mashpee tribe of Native Americans, women’s suffragists, and both foes and defenders of the anti-slavery movement. As a lawyer in 1854, the future president Abraham Lincoln defended nine women who had destroyed an Illinois saloon in the name of the temperance movement. He argued that the Boston Tea Party was a worthy model for their actions.

American suffragettes picket a building bearing the name of the National Woman’s Party, c1900. (Getty images)

Mahatma Gandhi After the British government in South Africa mandated that resident Indians had to be registered and fingerprinted under the Asiatic Registration Act of 1907, Mahatma Gandhi adopted the practice of satyagraha, or non-violent protest. He led the Indian community in the burning of registration cards at mass meetings in August 1908. Gandhi later wrote that a British newspaper correspondent had compared the protest to the Boston Tea Party.

US tax protestors

Today the Boston Tea Party is proving a rallying point for conservative Americans. American tax protesters have often invoked the Tea Party as their inspiration since the 1970s. The libertarian presidential candidate Ron Paul held a campaign fundraiser on 16 December 2007. In February 2009, a business news broadcaster called for a “tea party” to protest against the US government’s plan to help refinance home mortgages. With the help of national organisations and media attention, the movement stitched together local groups of protestors. The tea partiers have been calling for less federal regulation and lower taxes.

Republic of China (Taiwan)

In late 1923, during the struggle for power in China between the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) and the Communist Party of China, Sun Yat-Sen, head of the Kuomintang, threatened to seize customs revenues from Guangzhou. The United States and other western nations sent warships to intervene. On 19 December (three days after the 150th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party), Sun wrote: “We must stop that money from going to Peking to buy arms to kill us, just as your forefathers stopped taxation going to the English coffers by throwing English tea into Boston Harbor.”

African-American civil rights

In his 1963 ‘Letter from a Birmingham Jail,’ the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr called for a “nonviolent direct action program” in Birmingham, Alabama. Discussing his historical inspiration, he wrote: “In our own nation, the Boston Tea Party represented a massive act of civil disobedience.” Three years later, Robert F Williams would recall the Tea Party to rally more violent action on behalf of African-American civil rights: “Burn, baby, burn.”

Benjamin L Carp is associate professor of history, Tufts University, Massachusetts. His book Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America (Yale University Press) is out now.

Published on January 14, 2018 23:30

January 6, 2018

Q&A: Were ducking stools ever used as punishment for crimes other than witchcraft during the Middle Ages?

History Extra

Illustration by Glen McBeth.

The story of the ducking stool is complex and confusing, and subject to various local usages from Anglo-Saxon times right up to the early 19th century.

The confusion is partly over the use of the ‘cucking stool’, a chair to which people – men and women – were tied and put on public display as a form of humiliation for various offences against the peace of the community (drunkenness, gossip), sexual offences or dishonest trading. Its use was common in the Middle Ages but its victims were not generally immersed into water; it was more like the pillory or the stocks.

While in some places women (and some men) were ducked on stools in order to establish whether or not they were witches, the more common means of identifying them was to throw them into the water with a rope attached to see whether or not they floated (guilty) or sank (not guilty).

The ‘ducking’ stool, involving water, may not have appeared until Tudor times, though its use was widespread through England, Scotland and colonial America by the 17th century and it didn’t fall out of use completely until the early 19th.

By then it was long recognised was a punishment almost exclusively for women for a range of minor offences, most of which might be characterised as not behaving as a dutiful maid or wife were expected to. Often the sentence was for being a ‘common scold’.

One memorable fable surrounds the final use of Bristol’s ducking stool in the early 1700s, though we don’t know how true it is. The mayor, Edmund Mountjoy, widely known to be hen-pecked, was out for a walk one evening when he came across a woman berating her own husband, so he ordered that she be ducked. Mistress Blake – we don’t know her full name – endured her punishment, but on emerging from the water ridiculed Mountjoy in front of the crowd for ducking another man’s wife because he didn’t have the courage to duck his own.

She then sued him for assault, and won. Mountjoy’s fellow city fathers enjoyed a season of fun at his expense by inviting him to dinners at which the menu always included … ‘cold duck’.

Because of this (the story goes), Bristol’s ducking stool fell into disuse, and was later bought by an enterprising huckster who turned it into dozens of snuff boxes, claiming that they would protect buyers from nagging and hen-pecking wives.

Answered by Eugene Byrne, author and journalist.

Published on January 06, 2018 23:30

Ancient Symbolism of the Magical Phoenix

Ancient Origins

The symbolism of the Phoenix, like the mystical bird itself, dies and is reborn across cultures and throughout time.

Ancient legend paints a picture of a magical bird, radiant and shimmering, which lives for several hundred years before it dies by bursting into flames. It is then reborn from the ashes, to start a new, long life. So powerful is the symbolism that it is a motif and image that is still used commonly today in popular culture and folklore.

The legendary phoenix is a large, grand bird, much like an eagle or peacock. It is brilliantly coloured in reds, purples, and yellows, as it is associated with the rising sun and fire. Sometimes a nimbus will surround it, illuminating it in the sky. Its eyes are blue and shine like sapphires. It builds its own funeral pyre or nest, and ignites it with a single clap of its wings. After death it rises gloriously from the ashes and flies away.

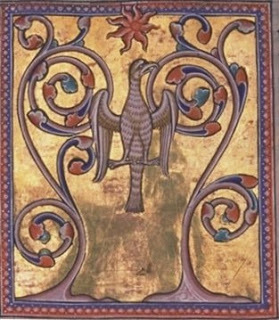

Image: Phoenix rising from the ashes in Book of Mythological Creatures by Friedrich Johann Justin Bertuch (1747-1822)

The phoenix symbolizes renewal and resurrection, and represents many themes, such as “the sun, time, the empire, metempsychosis, consecration, resurrection, life in the heavenly Paradise, Christ, Mary, virginity, the exceptional man”.

Tina Garnet writes in The Phoenix in Egyptian, Arab, &; Greek Mythology of the long-lived bird, “When it feels its end approaching, it builds a nest with the finest aromatic woods, sets it on fire, and is consumed by the flames. From the pile of ashes, a new Phoenix arises, young and powerful. It then embalms the ashes of its predecessor in an egg of myrrh, and flies to the city of the Sun, Heliopolis, where it deposits the egg on the altar of the Sun God.”

There are lesser known versions of the myth in which the phoenix dies and simply decomposes before rebirth.

The Greek named it the Phoenix but it is associated with the Egyptian Bennu, the Native American Thunderbird, the Russian Firebird, the Chinese Fèng Huáng, and the Japanese Hō-ō.

It is believed that the Greeks called the Canaanites the Phoenikes or Phoenicians, which may derive from the Greek word 'Phoenix', meaning crimson or purple. Indeed, the symbology of the Phoenix is also closely tied with the Phoenicians.

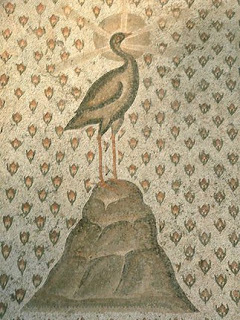

Phoenix and roses, detail. Pavement mosaic (marble and limestone), 2nd half of the 3rd century AD. From Daphne, a suburb of Antioch-on-the-Orontes (now Antakya in Turkey). Image source: Wikimedia

Perhaps the earliest instance of the legend, the Egyptians told of the Bennu, a heron bird that is part of their creation myth. The Bennu lived atop ben-ben stones or obelisks and was worshipped alongside Osiris and Ra. Bennu was seen as an avatar of Osiris, a living symbol of the deity. The solar bird appears on ancient amulets as a symbol of rebirth and immortality, and it was associated with the period of flooding of the Nile, bringing new wealth and fertility.

Greek historian Herodotus wrote that priests of ancient Heliopolis described the bird as living for 500 years before building and lighting its own funeral pyre. The offspring of the birds would then fly from the ashes, and carry priests to the temple altar in Heliopolis. In ancient Greece it was said the bird does not eat fruit, but frankincense and aromatic gums. It also collects cinnamon and myrrh for its nest in preparation for its fiery death.

In Asia the phoenix reigns over all the birds, and is the symbol of the Chinese Empress and feminine grace, as well as the sun and the south. The sighting of the phoenix is a good sign that a wise leader has ascended to the throne and a new era has begun. It was representative of Chinese virtues: goodness, duty, propriety, kindness and reliability. Palaces and temples are guarded by ceramic protective beasts, all lead by the phoenix.

The mythical phoenix has been incorporated into many religions, signifying eternal life, destruction, creation and fresh beginnings.

Due to the themes of death and resurrection, it was adopted a symbol in early Christianity, as an analogy of Christ’s death and three days later his resurrection. The image became a popular symbol on early Christian tombstones. It is also symbolic of a cosmic fire some believe created the world and which will consume it.

A reborn Phoenix. A ventral view of the bird between two trees, with wings out stretched and head to one side, possibly collecting twigs for its pyre but also associated with Jesus on the cross. Image source: Wikimedia

In Jewish legend the phoenix is known as the Milcham – a faithful and immortal bird. Going back to Eden, when Eve possessed the apple of knowledge, she tempted the animals of the garden with the forbidden fruit. The Milcham bird refused the offer, and was granted for its faith a town where it would live in peace almost eternally, rebirthing every thousand years, immune to the Angel of Death.

The Phoenix is also an alchemical symbol. It represents the changes during chemical reactions and progression through colors, properties of matter, and has to do with the steps of alchemy in the making of the Great Work, or the Philosopher’s Stone.

Modern additions to the myth in popular culture say the tears of the phoenix have great healing powers, and if the phoenix is near one cannot tell a lie.

Continually morphing and remorphing, the phoenix represents the idea that the end is only the beginning. Much like this powerful myth, the symbol of the phoenix will be reborn over and over again in human legend and imagination.

Featured image: Artist’s illustration of a phoenix. Image source.

References

Heaven Sent – American Museum of Natural History

Phoenix - Monstrous

The Phoenix in Egyptian, Arab, Greek Mythology - OnMarkProductions

Phoenix Symbol - Signology

Phoenix (Mythology) - Wikipedia

Magnum Opus - Wikipedia

By Liz Leafloor

Published on January 06, 2018 00:00

January 4, 2018

A brief history of how people communicated in the Middle Ages

History Extra

Official speech

In 14th and 15th-century England, as the Hundred Years’ War raged in France, towns and villages heard about events through official speech – primarily through their priests. The church communicated the successes (or setbacks) of their king to the populace: they required masses or procession for thanksgiving in light of a victory, and prayers and invocations for hopes of a success at the start of campaigns. This helped to build public support for wars and the taxes to pay for them.

Official news could be delivered in both written and oral form. The towns of the late medieval Low Countries (modern Belgium and the Netherlands) were ruled by the powerful Dukes of Burgundy. Charters issued by the dukes were written communications, setting out new rights, laws or taxes, but they also carried a significant aural quality: charters would have been read out at specific places in towns, known as bretèches, or in churches or at important civic events.

Rumour and subversive communication

Communication of legislation was important for medieval rulers, but, as today, people were also able to spread rumours and gossip. It is not always clear where medieval, or indeed modern, rumours began, but there is no doubt that they could spread quickly.

In the second half of the 14th century, England saw great upheaval and challenges: the war with France was going badly, and at home the Black Death, beginning in 1348–9, had killed at least a third of the population. Survivors might have hoped for better conditions, as a smaller work force tried to demand higher wages, but this was stopped by the Ordinance and Statute of Labourers setting wages at the pre-plague level.

In 1381 this famously erupted into the violence of the Peasants’ Revolt, but in 1377 there were already signs of discontent, manifested in the ‘Great Rumour’. This social movement, spread by word of mouth across southern England, saw rural labourers refusing to work, arguing that Domesday Book granted them exemptions from their feudal services.

Messengers and networks

In 12th-century England, kings did not stay in London – rather, they travelled around their lands. This necessitated an organised and efficient messenger service, ensuring that correspondence reached the king, and that royal letters, grants, patents and orders arrived at their intended destination. Messengers therefore became a permanent royal expenditure, paid continuously and travelling the kingdom to carry the king’s word.

The English system was efficient, allowing news to be carried quickly: in 1290 Edward I summoned a parliament to grant new taxes. The order, or writ, for the taxes was issued on 22 September at Edward’s hunting lodge in King’s Clipstone, in the Midlands. This was carried to the Privy Seal Office and then to the Barons of the Exchequer, in Westminster. The Exchequer then issued its own writs on 6 October to the sheriffs, ordering them to begin collections between the 18th and 29th of the month.

Thus, less than a month after Edward’s order, his messages had been transmitted to London and then out to the counties, and commissioners had begun their task.

Visual communication

As well as sending written messages, hearing official news from their priests, or listening to rumours spread form village to village, medieval people could also see messages. Late medieval clothing carried layers of meaning, and can be considered a potent means of communication – this is to an extent true also of the modern world, with black for funerals or badges and wrist bands to support causes.

On the battlefield, banners and coats of arms showed armies’ friend from foe, and royal standards enabled soldiers to see where their king was located. Coats of arms further marked out who was of a noble rank, and so worth taking prisoner, and who was not, meaning that being well dressed was about far more than vanity.

The wearing of badges and livery – clothes that bore a symbol, or particular colours or designs – marked out allegiance and community. Though their survival is rare, pilgrim badges were very common: they marked out those who had been on a religious journey, and acted as a souvenir, worn to show that one was devout and had visited Canterbury, or even Rome.

Guilds used badges or liveries to mark out their members, ensuring that anyone looking to buy goods or services in the medieval town would recognise a guild members from less reputable trades – visual forms of identification showed belonging and communicated identify and status.

Laura Crombie is a lecturer in late medieval history at the University of York.

Published on January 04, 2018 23:00

Planetary Wars Rise of an Empire by Mary Ann Bernal is now available for pre-order

Eva Braun meets Padmé Amidala

Caught up in a whirlwind romance, Anastasia Dennison, M.D., does not realize her husband is the terrifying dictator, Jayden Henry Shaw, who rules the galaxy with an iron fist while pretending to defend the vulnerable against the Imperial Forces of the Empire. Denying the existence of widespread suffering, Anastasia ignores her principles as she embraces the spoils of war and takes her rightful place among the upper echelon of Terrenean society. Will Anastasia continue to support her husband’s quest for complete domination of every world within the cosmos, or will she follow her conscience and fight the evil invading her home?

For Amazon Kindle edition click here

For Smashwords edition click here

Caught up in a whirlwind romance, Anastasia Dennison, M.D., does not realize her husband is the terrifying dictator, Jayden Henry Shaw, who rules the galaxy with an iron fist while pretending to defend the vulnerable against the Imperial Forces of the Empire. Denying the existence of widespread suffering, Anastasia ignores her principles as she embraces the spoils of war and takes her rightful place among the upper echelon of Terrenean society. Will Anastasia continue to support her husband’s quest for complete domination of every world within the cosmos, or will she follow her conscience and fight the evil invading her home?

For Amazon Kindle edition click here

For Smashwords edition click here

Published on January 04, 2018 10:09

3 curious medieval ghost stories

History Extra

In fact, the medieval conventions of what constituted a ghost story can seem quite odd to a modern reader, as can the apparitions that haunt them. Here are some examples of creepy tales that enthralled readers in England more than 600 years ago...

The Haunting of Frodriver

First recorded in the 13th century as part of the Eyrbyggja Saga, and translated by Sir Walter Scott in 1814 in Illustrations of Northern Antiquities

The story begins as a Hebridian woman named Thorgunna arrives in Iceland one winter. A local woman named Thuirda notices the rich treasures that Thorgunna possesses, and presses her to come and stay with her at her home in Froda.

Thorgunna refuses to part with any of her precious things, but agrees to stay and work as a servant. Soon Thorgunna falls ill and dies, but leaves behind a warning: her bedding is to be burnt, and most of her effects given to local monks. This, she says, is not out of spite, but as a way to protect the settlement from an evil that is coming.

Inevitably, Thurida can't resist taking the rich bedding of Thorgunna for herself, and sure enough the residents of Froda begin to fall victim to a series of grisly accidents, ghostly attacks, and mysterious plagues. After a funeral feast is held, they are beset by a crowd of walking ghouls that refuse to leave, and which gather around the central fire of the main hall each night.

But deliverance soon arrives when Kiartan, the son of Thurida, engages a local priest to stage a trial. The ghouls are charged with staying unlawfully in the hall, and eventually their leader declares, somewhat petulantly: “We have here no longer a peaceful dwelling, therefore will we remove.”

The Bathkeeper

From The Dialogi of Gregory the Great, published in the mid-10th century. Translated by EG Gardner in 1911, and published in Medieval Ghost Stories, by Andrew Joynes

A priest is visiting a hot spring when he comes across a man he hasn't seen before. The man promptly begins to attend to him, helping him to take off his clothes and shoes, and the priest naturally assumes that he is one of the servants there.

The priest then visits the baths several more times, and each time the man appears to him and offers to help him, but doesn't extract any form of payment. Eventually the priest decides that he should give the man a reward. He returns the next time with two Eucharist loaves, and offers them to the man with his gratitude.

When the man sees the loaves, he becomes distressed. He explains that he cannot eat holy bread, for he isn't a living man at all, but an apparition of the former overseer of the baths. He entreats the priest to intercede on his behalf so that he might find peace in the afterlife, and when he finishes speaking he vanishes, so that the priest knows for certain he has seen a ghost.

The priest offers up prayers, and sure enough the ghostly attendant never returns to him.

Byland Abbey Ghost Stories

From fragments in a late 14th-century manuscript, transcribed by MR James in 1920 in Twelve Medieval Ghost Stories

There are many ghost stories recorded by the Monk of Byland. One such tale features a man trying to make his way home with a load of beans after his horse meets with an accident. He sees a terrifying apparition of a horse, and after he tries to scare it away it begins to stalk him. The spirit then appears as a glowing ball of light in a cloud of hay.

Finally the man confronts the spirit in the name of the lord, and a ghostly figure appears in front of him. The spirit claims that it means the man no harm, and asks to carry his load of beans for him. The man agrees, and the load is carried across a river, before reappearing on his back. After this, the spirit vanishes.

In another local story, a spirit accosts two farm labourers, attacking one of them. The man calls on the lord, and the ghost confesses that it was the canon of Newburgh, excommunicated for theft. The labourer digs up a set of spoons stolen by the ghost, and afterwards its spirit rests in peace.

Medieval ghost stories, then, often fall into the category of exempla – cautionary tales intended to reinforce Christian values. But they can also show the exchange of cultures happening over a large expanse of time.

The events at Frodriver read like a mixture of a Christian exempla with more traditional Nordic notions of the undead, while the events described at Byland in Yorkshire feature the kind of aggressive, physical apparitions that Vikings were fond of describing.

MR James – perhaps the most influential modern writer of ghost stories – was also an important medieval scholar who rediscovered many of these stories. He revived features of medieval folklore in his tales, including ghosts that transform into objects, and dangers that lurk in everyday settings. So perhaps our own ghosts are closer to the medieval than we might think…

George Dobbs is a freelance writer who specialises in literature and history, and H Somerset is the author of Rat Abbey: Three Ghost Stories.

In fact, the medieval conventions of what constituted a ghost story can seem quite odd to a modern reader, as can the apparitions that haunt them. Here are some examples of creepy tales that enthralled readers in England more than 600 years ago...

The Haunting of Frodriver

First recorded in the 13th century as part of the Eyrbyggja Saga, and translated by Sir Walter Scott in 1814 in Illustrations of Northern Antiquities

The story begins as a Hebridian woman named Thorgunna arrives in Iceland one winter. A local woman named Thuirda notices the rich treasures that Thorgunna possesses, and presses her to come and stay with her at her home in Froda.

Thorgunna refuses to part with any of her precious things, but agrees to stay and work as a servant. Soon Thorgunna falls ill and dies, but leaves behind a warning: her bedding is to be burnt, and most of her effects given to local monks. This, she says, is not out of spite, but as a way to protect the settlement from an evil that is coming.

Inevitably, Thurida can't resist taking the rich bedding of Thorgunna for herself, and sure enough the residents of Froda begin to fall victim to a series of grisly accidents, ghostly attacks, and mysterious plagues. After a funeral feast is held, they are beset by a crowd of walking ghouls that refuse to leave, and which gather around the central fire of the main hall each night.

But deliverance soon arrives when Kiartan, the son of Thurida, engages a local priest to stage a trial. The ghouls are charged with staying unlawfully in the hall, and eventually their leader declares, somewhat petulantly: “We have here no longer a peaceful dwelling, therefore will we remove.”

The Bathkeeper

From The Dialogi of Gregory the Great, published in the mid-10th century. Translated by EG Gardner in 1911, and published in Medieval Ghost Stories, by Andrew Joynes

A priest is visiting a hot spring when he comes across a man he hasn't seen before. The man promptly begins to attend to him, helping him to take off his clothes and shoes, and the priest naturally assumes that he is one of the servants there.

The priest then visits the baths several more times, and each time the man appears to him and offers to help him, but doesn't extract any form of payment. Eventually the priest decides that he should give the man a reward. He returns the next time with two Eucharist loaves, and offers them to the man with his gratitude.

When the man sees the loaves, he becomes distressed. He explains that he cannot eat holy bread, for he isn't a living man at all, but an apparition of the former overseer of the baths. He entreats the priest to intercede on his behalf so that he might find peace in the afterlife, and when he finishes speaking he vanishes, so that the priest knows for certain he has seen a ghost.

The priest offers up prayers, and sure enough the ghostly attendant never returns to him.

Byland Abbey Ghost Stories

From fragments in a late 14th-century manuscript, transcribed by MR James in 1920 in Twelve Medieval Ghost Stories

There are many ghost stories recorded by the Monk of Byland. One such tale features a man trying to make his way home with a load of beans after his horse meets with an accident. He sees a terrifying apparition of a horse, and after he tries to scare it away it begins to stalk him. The spirit then appears as a glowing ball of light in a cloud of hay.

Finally the man confronts the spirit in the name of the lord, and a ghostly figure appears in front of him. The spirit claims that it means the man no harm, and asks to carry his load of beans for him. The man agrees, and the load is carried across a river, before reappearing on his back. After this, the spirit vanishes.

In another local story, a spirit accosts two farm labourers, attacking one of them. The man calls on the lord, and the ghost confesses that it was the canon of Newburgh, excommunicated for theft. The labourer digs up a set of spoons stolen by the ghost, and afterwards its spirit rests in peace.

Medieval ghost stories, then, often fall into the category of exempla – cautionary tales intended to reinforce Christian values. But they can also show the exchange of cultures happening over a large expanse of time.

The events at Frodriver read like a mixture of a Christian exempla with more traditional Nordic notions of the undead, while the events described at Byland in Yorkshire feature the kind of aggressive, physical apparitions that Vikings were fond of describing.

MR James – perhaps the most influential modern writer of ghost stories – was also an important medieval scholar who rediscovered many of these stories. He revived features of medieval folklore in his tales, including ghosts that transform into objects, and dangers that lurk in everyday settings. So perhaps our own ghosts are closer to the medieval than we might think…

George Dobbs is a freelance writer who specialises in literature and history, and H Somerset is the author of Rat Abbey: Three Ghost Stories.

Published on January 04, 2018 00:00

January 2, 2018

The medieval longing for the good old days

History Extra

Illustration by Femke De Jong.

“When Adam dug and Eve span, Who was then a gentleman?” So spoke John Ball, one of the leaders of the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt, and a fiery, rousing preacher. As reported in the chronicle of Thomas Walsingham, Ball evoked a lost world, in which men were equal, free and dignified. Protesters should, declared Ball, like “a good husbandman… uprooting the tares [weeds] that are accustomed to destroy the grain”, rise up to restore this age of liberty.

Ball drew on a nostalgic image of a rural idyll – where all worked hard, and were justly rewarded – to provide a vision of hope for the future. A letter from one rebel, Jack Trewman, argued that “falseness and deceit have reigned too long, and truth has been set under lock and key, and falseness now reigns everywhere”. The rhetoric was powerful with its vivid alliterations, rhymes and appeal to a nostalgia for a past golden age.

But nostalgia was not the exclusive preserve of the rebels. If the peasants claimed that they wanted a return to “the good old laws” of yesteryear, Walsingham conversely accused them of trying to “wipe out… the memory of ancient customs”.

His language appealed to a conservative nostalgia for a rigid social order when peasants knew their place. This rhetoric was mirrored in sermons that lamented the passing of a better age when social hierarchies were apparently stable and people just got on with their work. “The world is transposed upside-down,” cried one 14th-century preacher.

That’s the genius of nostalgia – it can be used to bolster two utterly conflicting arguments. This yearning for an idealised past can rouse radicalism, but it can also sustain reactionary fears.

The Oxford English Dictionary describes nostalgia as a “sentimental longing for or regretful memory of a period of the past”. Or, as a medieval proverb, put it: “It’s in the evening that we look back on the day with pleasure.” In short, it’s something we can all identify with.

Compulsive weeping

The term ‘nostalgia’ was invented by Johannes Höfer, a Swiss doctor, in 1688. He was alarmed by the levels of homesickness that seemed to be affecting many patients, particularly Swiss mercenary soldiers operating in the lowlands of Italy and France, in the 17th century. Höfer identified physical symptoms that included compulsive weeping, anorexia and palpitations. More recently psychologists have offered a more nuanced interpretation of nostalgia – and have concluded that sometimes it can cheer us up. Importantly, whereas the term was invented to describe longing for home, it has now come to mean longing for a past time.

Today it’s widely assumed that nostalgia is a modern phenomenon. Discombobulated by the rapid pace of change in the industrialised world, modern people, so the theory goes, express unprecedented levels of yearning for a time when life was more predictable and slower-paced. The truth, however, is rather different.

The term may not have been coined until the 17th century, but there’s nothing new about nostalgia. Medieval literature is peppered with it – and the 14th century, it seems, saw a particular spike. It was during this century that the French knight Geoffroi de la Tour Landry wrote: “Things aren’t what they used to be/How I long for the old times again!” And Geoffroi was far from alone in donning rose-tinted spectacles and using the past to critique the present. In fact, it seems that he was in many ways reflecting the mood of his times.

But why? Is it because nostalgia is a human trait that stretches beyond modern preoccupations? Or was the 14th century ripe for this kind of reflection on the past because some of those same features of modernity – such as rapid change and commercialisation – were already emerging?

Shock of the new

The 14th century was indeed a time of cataclysmic change throughout Europe. There was horrific famine in the first half of the century, up to 50 per cent of the population was wiped out by recurrent epidemic plague, and warfare ravaged much of the countryside. It was also a time of rapid commercialisation: business and banking practices grew ever-more sophisticated, lending at interest intensified, prices fluctuated as never before.

The rise of merchants – who now routinely travelled across Europe – coupled with the job opportunities provided by mass mortality and rapid urbanisation across the continent, seemed to stimulate unprecedented social mobility. As the poet Dante Alighieri put it in his early 14th-century Purgatorio: “The former age rebukes the new.”

These changes provoked both individual and collective nostalgia. On the one hand, we find a figure like the successful Prato merchant, Francesco Datini, writing to his wife Marguerita about how much he misses the sights and smells of home when he is away on business. On the other hand, and more visible to the historian, nostalgia was a source of widespread social unease. The late 14th-century English romance poem Sir Tryamour expresses it pithily: “The goodness of our forefathers has now entirely gone.”

These writers were not entirely innovating. The poet John Gower evoked the sense of transience in modern times by referencing Boethius (AD 480–524), and wrote: “The fortune of the present day has forsaken the blessed life of the past.”

In the face of rapid urbanisation, writers in the 14th century harked back to an imagined pastoral idyll. In doing so, they were drawing on earlier medieval troubadour poetry (itself perhaps inspired by Arabic poetry) and on classical ideas of a bucolic utopia dating back to Virgil and Horace. But in the 14th century, these idylls were used to criticise the evils of city life.

Much of the nostalgia of the century was provoked by anxiety about commercialisation, what looked like increasingly erratic prices, and monetary debasement. Sermons criticised the pride and avarice of merchants by referring back to a time when traders were not motivated by greed. A sermon now in St Albans Cathedral archive tells of “the just weights and measures” of the past, now manipulated and used for cheating. The poet John Gower elucidated: “In olden days, people behaved properly, without deceit, and without envy. Their buying and selling was honest, without trickery.” Bishop Brinton warned that “false traders in these days infringe the rule of justice”.

Nostalgia could also have a political edge. Boniface VIII, pope and arch-enemy of Philip IV of France, contrasted the king’s conduct with “the happy actions of your forefathers” and their “sincere devotion”. Similar themes were apparent in England. A late medieval English poem lamented: “Once upon a time we had an English ship/It was noble and had high towers.”

Preachers accused current monarchs of neglecting the wellbeing of their citizens. It was a powerful rhetoric, almost guaranteed to appeal to popular emotion. In the context of the growing weakness of the English position in the Hundred Years’ War against France, one sermon claimed that in the past “all Christian kings feared us and spoke of our victory and courage”. Philippe de Mézières, a late 14th-century French knight, described the effects of the Hundred Years’ War on his own country by evoking his childhood, when “the kingdom was rich and [somewhat enigmatically] as full as an egg”.

The rot sets in

In Italy, writers painted the century as a time of degeneration, employing past glories to criticise the present. In Florence, they couldn’t quite agree about which period to be nostalgic about. Chroniclers such as Giovanni Villani looked back on the 13th century as a time of military, political and commercial prowess: “They were loyal and faithful… they did greater and more virtuous deeds than are performed in our own time.” But Dante Alighieri argued that the rot had set in earlier than that. His nostalgia was for the 12th century, the time when “Florence [was] in such tranquillity that she had nothing to cause her grief”.

Fifty years later, in his own writings on Dante, the poet Boccaccio complained that the city (and its art) “once ennobled by geniuses… is now itself corrupted by avarice”. Boccaccio was writing after famine and epidemic disease had wiped out huge swathes of the population, enabling the labourers who did survive to demand better remuneration. He would take up this theme to castigate the corruption of the manners by “new men”. He saw inappropriate clothing as a potent symbol of the pernicious effects of social mobility. In England, the preacher Rypon fumed that: “The garments… of those who were once noble are now divided as spoil… among grooms, and maid-servants and prostitutes.”

Boccaccio’s fulminations were echoed in legislation that attempted to regulate the kinds of clothing people of each social station were permitted to wear – and to evoke, through law, a former age.

Yet it wasn’t just those trying to fight their way up the social ladder who were failing to live up to their predecessors’ supposed high standards. Apparently, knights also had forgotten their calling. Chivalry had always been founded on a longing for the good old days of King Arthur, but the intensity of this nostalgia was ratcheted up a notch in the 14th century. The chronicler Jean le Bel wistfully remarked: “These days a humble page is as well and as finely armed as a noble knight. Things have changed a lot I feel.”

Chivalry’s fall from grace was partly driven by a sense that modern knights no longer knew how to fight, only to dress up. The preacher Bromyard compared the pretentious flourishes of modern knights with the “strenuous battling… of the knights of antiquity – Charlemagne, Roland and Oliver”. In the past, apparently, knights were real men. The early humanist Petrarch wrote of Italian mercenaries that they lack the “antico valore”, and now “snort and perspire not manfully, but feverishly, not as soldiers, but as women or buffoons”.

If this was about status, it was also about sex. “Once upon a time, young men were ashamed of their dishonourable hidden thoughts; nowadays, they go round showing off things that even animals would gladly conceal if they only could,” ranted one holier-than-thou preacher.

Even children no longer knew their place. “In the olden days, children that were rebellious and disobedient to their fathers and mothers were beaten,” a misty-eyed sermon lamented of times gone by.

In short, a sense of melancholic nostalgia permeated the century. It could be radical, as in the Peasants’ Revolt; it could be reactionary; and it affected the entire social spectrum. The words ‘ubi sunt?’ – ‘Where have they gone?’ – became a catchphrase for the times, embodying a sense of transience and a yearning for a happier past.

In the mid-15th century, the poet François Villon wrote wistfully: “Where are the snows of yesteryear?” Everything melts away, and people in the later Middle Ages were acutely aware that war, commercialisation, political change and disease were transforming their lives. As Chaucer wrote in his poem The Former Age: “A blissful, peaceful and sweet life/was led by people in the olden days.”

Hannah Skoda is associate professor of medieval history at St John’s College, Oxford.

Illustration by Femke De Jong.

“When Adam dug and Eve span, Who was then a gentleman?” So spoke John Ball, one of the leaders of the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt, and a fiery, rousing preacher. As reported in the chronicle of Thomas Walsingham, Ball evoked a lost world, in which men were equal, free and dignified. Protesters should, declared Ball, like “a good husbandman… uprooting the tares [weeds] that are accustomed to destroy the grain”, rise up to restore this age of liberty.

Ball drew on a nostalgic image of a rural idyll – where all worked hard, and were justly rewarded – to provide a vision of hope for the future. A letter from one rebel, Jack Trewman, argued that “falseness and deceit have reigned too long, and truth has been set under lock and key, and falseness now reigns everywhere”. The rhetoric was powerful with its vivid alliterations, rhymes and appeal to a nostalgia for a past golden age.

But nostalgia was not the exclusive preserve of the rebels. If the peasants claimed that they wanted a return to “the good old laws” of yesteryear, Walsingham conversely accused them of trying to “wipe out… the memory of ancient customs”.

His language appealed to a conservative nostalgia for a rigid social order when peasants knew their place. This rhetoric was mirrored in sermons that lamented the passing of a better age when social hierarchies were apparently stable and people just got on with their work. “The world is transposed upside-down,” cried one 14th-century preacher.

That’s the genius of nostalgia – it can be used to bolster two utterly conflicting arguments. This yearning for an idealised past can rouse radicalism, but it can also sustain reactionary fears.

The Oxford English Dictionary describes nostalgia as a “sentimental longing for or regretful memory of a period of the past”. Or, as a medieval proverb, put it: “It’s in the evening that we look back on the day with pleasure.” In short, it’s something we can all identify with.

Compulsive weeping

The term ‘nostalgia’ was invented by Johannes Höfer, a Swiss doctor, in 1688. He was alarmed by the levels of homesickness that seemed to be affecting many patients, particularly Swiss mercenary soldiers operating in the lowlands of Italy and France, in the 17th century. Höfer identified physical symptoms that included compulsive weeping, anorexia and palpitations. More recently psychologists have offered a more nuanced interpretation of nostalgia – and have concluded that sometimes it can cheer us up. Importantly, whereas the term was invented to describe longing for home, it has now come to mean longing for a past time.

Today it’s widely assumed that nostalgia is a modern phenomenon. Discombobulated by the rapid pace of change in the industrialised world, modern people, so the theory goes, express unprecedented levels of yearning for a time when life was more predictable and slower-paced. The truth, however, is rather different.

The term may not have been coined until the 17th century, but there’s nothing new about nostalgia. Medieval literature is peppered with it – and the 14th century, it seems, saw a particular spike. It was during this century that the French knight Geoffroi de la Tour Landry wrote: “Things aren’t what they used to be/How I long for the old times again!” And Geoffroi was far from alone in donning rose-tinted spectacles and using the past to critique the present. In fact, it seems that he was in many ways reflecting the mood of his times.

But why? Is it because nostalgia is a human trait that stretches beyond modern preoccupations? Or was the 14th century ripe for this kind of reflection on the past because some of those same features of modernity – such as rapid change and commercialisation – were already emerging?

Shock of the new

The 14th century was indeed a time of cataclysmic change throughout Europe. There was horrific famine in the first half of the century, up to 50 per cent of the population was wiped out by recurrent epidemic plague, and warfare ravaged much of the countryside. It was also a time of rapid commercialisation: business and banking practices grew ever-more sophisticated, lending at interest intensified, prices fluctuated as never before.

The rise of merchants – who now routinely travelled across Europe – coupled with the job opportunities provided by mass mortality and rapid urbanisation across the continent, seemed to stimulate unprecedented social mobility. As the poet Dante Alighieri put it in his early 14th-century Purgatorio: “The former age rebukes the new.”

These changes provoked both individual and collective nostalgia. On the one hand, we find a figure like the successful Prato merchant, Francesco Datini, writing to his wife Marguerita about how much he misses the sights and smells of home when he is away on business. On the other hand, and more visible to the historian, nostalgia was a source of widespread social unease. The late 14th-century English romance poem Sir Tryamour expresses it pithily: “The goodness of our forefathers has now entirely gone.”

These writers were not entirely innovating. The poet John Gower evoked the sense of transience in modern times by referencing Boethius (AD 480–524), and wrote: “The fortune of the present day has forsaken the blessed life of the past.”

In the face of rapid urbanisation, writers in the 14th century harked back to an imagined pastoral idyll. In doing so, they were drawing on earlier medieval troubadour poetry (itself perhaps inspired by Arabic poetry) and on classical ideas of a bucolic utopia dating back to Virgil and Horace. But in the 14th century, these idylls were used to criticise the evils of city life.

Much of the nostalgia of the century was provoked by anxiety about commercialisation, what looked like increasingly erratic prices, and monetary debasement. Sermons criticised the pride and avarice of merchants by referring back to a time when traders were not motivated by greed. A sermon now in St Albans Cathedral archive tells of “the just weights and measures” of the past, now manipulated and used for cheating. The poet John Gower elucidated: “In olden days, people behaved properly, without deceit, and without envy. Their buying and selling was honest, without trickery.” Bishop Brinton warned that “false traders in these days infringe the rule of justice”.

Nostalgia could also have a political edge. Boniface VIII, pope and arch-enemy of Philip IV of France, contrasted the king’s conduct with “the happy actions of your forefathers” and their “sincere devotion”. Similar themes were apparent in England. A late medieval English poem lamented: “Once upon a time we had an English ship/It was noble and had high towers.”

Preachers accused current monarchs of neglecting the wellbeing of their citizens. It was a powerful rhetoric, almost guaranteed to appeal to popular emotion. In the context of the growing weakness of the English position in the Hundred Years’ War against France, one sermon claimed that in the past “all Christian kings feared us and spoke of our victory and courage”. Philippe de Mézières, a late 14th-century French knight, described the effects of the Hundred Years’ War on his own country by evoking his childhood, when “the kingdom was rich and [somewhat enigmatically] as full as an egg”.

The rot sets in