MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 31

February 7, 2018

Monsanto: The Thriving Medieval Town Built Around Giant Boulders

Ancient Origins

In most parts of Europe, the medieval period ended around the fourteenth century, right around the time Giotto introduced perspective into the art of pre-Renaissance Italy. Yet for the twelfth century municipality of Monsanto in Portugal, the middle ages were just beginning. With Mount Monsanto rising in the east, a shortage of supplies and space forced those living within its shadow to merge with it, forming one of the single most intriguing cities still thriving in the world today. In essence, one could call the inhabitants of Monsanto people of the mountain.

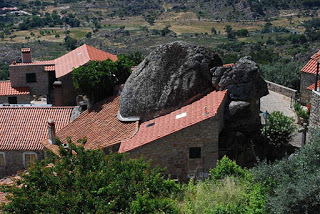

In the province of Idanha-a-Nova (since renamed Idanha-a-Velha), the people of Monsanto live in, under, beside and between the enormous boulders that shaped the village. Situated along the Spanish border "in the Northeast" and "nestled on a steep hill slope [the] Monsanto hillock (Mons Sanctus)…abruptly rises out of the prairie and reaches 758 meters on its highest point. There are several hamlets scattered along the several slopes and at the bottom of the hill, which shows the population movements towards the plain." This mountain-side village has thrived since its medieval founding, holding tight to its early traditions, merging with the very essence of the city's foundation—the rock of Mount Monsanto itself.

House constructed under a rock in Monsanto. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Called a "geopark" under UNESCO, the villagers were forced to work with the granite rocks protruding from the mountain, adapting the medieval structure of their city to fit the overwhelming, unmovable arms of the mountain. Where the boulders fell, house walls, street boundaries, and structural stability were dependent, and this constructive pattern has only continued as time has gone on.

The village has kept much of its medieval construction. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

In the present, Monsanto remains unwavering. In lieu of automobiles, trains, etc., "the streets of the village are too narrow and steep to use any kind of transportation except donkeys." Built atop a mountain, one would expect the steepness. But rather than attempting to restructure their community so that houses are made of brick and mortar rather than of "boulders…fitted with doors" and "red-roofed cottages tucked against" the same boulders, the inhabitants of Monsanto continue to live amongst the mountain’s crevices. The lack of modern conveniences is refreshingly not a deterrent.

House constructed between two boulders. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Though the majority of what remains of Monsanto village is structurally medieval, the origins of the town extend much further back. Traces of Stone Age habitation have been found, along with archaeological evidence of a Lusitanian fortress and of Roman occupation in St. Laurence's field, at the foot of the hill, as well as of Visigoth and Arabian occupation. Likely settling in the region under the Roman Empire, the Romans thrived at the base of the mountain while the native culture was still widely considered Gallic.

The Visigoths (5th-8th centuries AD) arrived at the end of the Roman Empire, usurping the Roman hold that had long laid over the previously Gallic community. During the Reconquista (approximately 718– 1492 AD), King Afonso Henriques conquered Monsanto from the Moors, eventually establishing the country of Portugal in the process. In 1165, the king granted the city to the Templar monks and Monsanto became something of a highlight of religious worship.

Above the village is a medieval castle/fortress that originated in the 12th century. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Throughout all of the turmoil surrounding creation and support of the impressive rock-friendly village, the city continued on with its stoic existence. While the landscape changed around them, the mountain-top village was relatively constant. It thrived embedded in the foundation of the mountain, watching as a silent observer of the various religious and political battles, and vigilantly continues to serve a stoic guardian of the Portuguese and Spanish borders.

Top image: Inbuilt rock house of Monsanto, Portugal. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

By Riley Winters

Published on February 07, 2018 00:00

February 6, 2018

Poseidon’s Wrath - The Scourge of the Sea Peoples

Ancient Origins

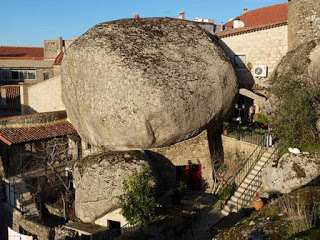

Perhaps 3 000 years from now archaeologists will be debating the reasons for the diaspora that occurred in the lands around the Mediterranean Sea during the early 21st century. What would have accounted for the mass migration of foreigners from the near Middle East and Africa to far northern European countries, they might ask? Would they know about the brutal civil war in Syria causing families to hastily flee with the few possessions they could carry; would they find some of the remnants of 100s of rubber dinghies that littered the shores of Rhodes? Would they consider famine and political-religious conflict in Africa causing families to hand over their life savings in desperation to pirates for sea passage? Would they find some artifacts such as a plastic doll, the last sentimental keepsake of a child that drowned in the perilous sea? About 3 000 years ago, a similar situation occurred when Poseidon in a bout of anger stirred the Mediterranean basin and today we still speculate as to the origins of the so-called Sea Peoples.

Reconstruction of a part of the Hittite city wall, Lower City of Hattusa, Turkey (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Late Bronze Age

The Late Bronze Age was a marked prosperous era. One only has to visit the enormous palace-temple complex at Knossos (Crete), the fortified royal settlement at Mycenae (Greek Peloponnese), the magnificent Hittite capital of Hattusa (northern Turkey); the bustling near-eastern Mediterranean sea ports of Ugarit, (Syria) Byblos, Sidon and Tyre (Lebanon); the wealthy Mesopotamian cities located on the fertile banks of the Tigris and the Euphrates, such as Nippur, Ur, Lagash and Babylon; (Iran and Iraq); down to the royal residences of Memphis, Akhentaten and Thebes along the Nile (Egypt), to realize they all flourished and benefitted from trade. Hugging Poseidon’s Mediterranean coastline merchant ships traded in tin from what is today England, copper from Cyprus, Turkey and the fertile crescent, glass, cedar and incense from the Levant, lapis from north of the Indus valley, gold from Egypt and ivory from Africa. But wealth breeds envy, which leads to war and Ares challenged Poseidon’s supremacy.

The Battle of Kadesh

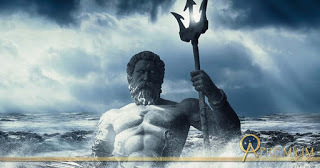

In 1274 BC the mighty Hittites led by King Muwatalli (1295 – 1272 BC) and the equally powerful Egyptians led by Ramesses II (1279 – 1213 BC) faced each other at the Battle of Kadesh (located on the Orontes river on the border of modern Syria and Lebanon). This battle is famous for being the first recorded battle where two-wheeled chariots were employed as war machines. The battle was undecisive and both sides claimed victory. The Egyptians claimed: “(King Ramesses II) cast them into the river like crocodiles, and he slew whomever he desired,” while the Hittite version reads: “at the time when King Muwatalli made war against the king of Egypt, when he defeated the king of Egypt.”

Mural in Ramesses II's temple in Tebes, depicting the Battle of Kadesh (Public Domain)

The war, like most wars, depleted the resources of the empires, which opened the door to exterior threats. In 1280 BC, Egypt had to ward off an attack from Libya, who had formed an alliance with the Sherdans. These fierce warriors were identified as probably Mycenaeans, due to depictions of their Mycenaean horned helmets. The Sherdans settled at Akko and later bequeathed their name to Sardinia. (There is some speculation that they may have originated from Sardinia’s Nuragic civilization.) The Sherdan became mercenaries, fighting on both sides during the Battle of Kadesh. The Libyans were defeated, but they remained a menace. The rising power of Assyria in northern Mesopotamia posed a more serious threat to both the Hittites and the Egyptians, which led the previous adversaries (represented by Pharaoh Ramesses II and King Hattusilis III) to sign a peace treaty in 1269 BC, where they agreed to become allies against aggressive acts.

Top Image: Poseidon, god of the Mediterranean Sea (CC0)

By Dr Micki Pistorius

Published on February 06, 2018 00:00

February 4, 2018

Britannia, Druids and the Surprisingly Modern Origins of Myths

Ancient Origins

The new TV series Britannia, which has won plaudits as heralding a new generation of British folk-horror, is clearly not intended to be strictly historical. Instead director Jez Butterworth gives us a graphic re-imagining of Britain on the eve of the Roman conquest. Despite its violence and chaos, this is a society bound together by ritual under the head Druid (played by Mackenzie Crook). But where does this idea of pre-conquest British religion come from?

Contemporary sources of the period are very thin on the ground and were mainly written by Britain’s Roman conquerors. No classical text provides a systematic account of Druidical ritual or belief. In fact, little was written at length for hundreds of years until William Camden, John Aubrey and John Toland took up the subject in the 1500s and 1600s. But it took later antiquarians, including William Stukeley writing in 1740, as well as William Borlase in 1754 and Richard Polwhele in 1797, to fully develop their thinking.

Popular ideas of pre-Roman Britain today are derived from their elaborate Druidical theories: the bearded Druid, possessor of arcane knowledge, the stone circles, the ritualistic use of dew, mistletoe and oak leaves in dark, wooded groves, and the ultimate horror of human sacrifice and the bacchanalia that followed.

MacKenzie Crook as head Druid Veran in Britannia. (Sky Atlantic)

Ancient disputes

The antiquarians were a disputatious lot and their debates can seem baffling, but underpinning them were fundamental questions about the first settlement of the British Isles and its religious history. In particular, the antiquarians asked if ancient Britons were monotheistic, practising a “natural” religion awaiting Christian “revelation”, or polytheistic idolaters who worshipped many false gods.

The answer to this question determined how the antiquarians understood the monumental stone structures left by this past culture. Were Stonehenge, Avebury or the antiquarian riches of Devon and Cornwall not just relics of idolatry and irreligion but also evidence of the supposed hold the Celts once had over the land? Conversely, if the stone circles and other relics were evidence of the struggle by an ancient people to make sense of the one true God before Roman Catholicism corrupted their beliefs (remember these antiquarians were all Protestant thinkers), then a God-fearing Englishman could claim them as a part of his heritage.

Stukeley believed Britain’s first settlers were eastern Mediterranean seafarers – the so-called Phoenicians – and they brought Abrahamic religion with them. In studies of Stonehenge (1740) and Avebury (1743), he argued that the ancient peoples descended from these first settlers lost sight of these beliefs but retained a core grasp of the fundamental “unity of the Divine Being”. This was represented in stone circles, so “expressive of the nature of the deity with no beginning or end”.

By this reading, Druidical veneration of heavenly bodies, the Earth and the four elements was not polytheism but the worship of the most extraordinary manifestations of this single deity. Moreover, that this worship was conducted in the vernacular and relied on the development of a teaching caste intended to enlighten the people meant that Druidical religion was the forerunner of Protestantism.

Sacred site. (Sky Atlantic)

Borlase, surveying Cornwall’s antiquities, rejected much of this. He scoffed at Stukeley’s Phoenician theories, saying it was illogical that Britain’s first people were overseas traders, and he argued that Druidism was a British invention that crossed the channel to Gaul. Borlase reckoned patriotic French antiquarians, convinced Gauls and Druids had resisted Roman tyranny, were reluctant to admit that “their forefathers [were] indebted so much to this island”.

But was Druidism something to be proud of? By drawing on classical, Biblical and contemporary sources, Borlase developed an elaborate account of the Druids as an idolatrous priesthood who manipulated the ignorance of their followers by creating a sinister air of mystery.

According to Borlase, Druidical ritual was bloody, decadent, immoral stuff, with plenty of sex and booze, and only compelling in atmospheric natural settings. Druidical power rested on fear and Borlase implied that Catholic priests, with their use of incense, commitment to the Latin mass and superstitious belief in transubstantiation, used the same techniques as the Druids to maintain power over their followers.

Going over old ground

Poems such as William Mason’s Caractatus (1759) helped popularise the idea that the Druids led British resistance to the invading Romans – but by the 1790s sophisticated metropolitan observers treated this stuff with scorn. Despite this, Druidical theories retained much influence, especially in south-west England. In Polwhele’s histories of Devonshire (1797), he wrote of Dartmoor as “one of the principal temples of the Druids”, as evident in iconic Dartmoor sites such as Grimspound, Bowerman’s Nose and Crockern Tor.

Most important were the “many Druidical vestiges” centred on the village of Drewsteignton, whose name he believed was derived from “Druids, upon the Teign”. The cromlech, known as Spinsters’ Rock, at nearby Shilstone Farm invited much speculation, as did the effect achieved by the “fantastic scenery” of the steep-sided Teign valley.

Spinsters’ Rock, Dartmoor. Matthew Kelly, Author provided

Polwhele’s influence was felt in Samuel Rowe’s A Perambulation of Dartmoor (1848), the first substantial topographical description of the moor. Many Victorians first encountered Dartmoor through Rowe’s writings but the discussion of these texts in my history of modern Dartmoor shows that a new generation of preservationists and amateur archaeologists did not take Druidical theories very seriously.

For the late Victorian members of the Devonshire Association and the Dartmoor Preservation Association, scepticism was a sign of sophistication. If an earlier generation had detected Druidical traces in virtually all Dartmoor’s human and natural features, these men and women were more likely to see evidence of agriculture and domesticity. Grimspound, once a Druidical temple, was now thought to be a cattle pound.

Despite Protestant hopes during the Reformation that superstitious beliefs associated with landscape features would be banished, the idea that the landscape holds spiritual mysteries that we know but cannot explain, or that the stone circles of antiquity stimulate these feelings, remains common enough. Indeed, Protestantism came to terms with these feelings and the Romantics saw the beauties of the British landscape as the ultimate expression of God’s handiwork.

Britannia recalls Robin of Sherwood (1984-6), with its mystical presentation of the English woodland and, of course, the BBC comedy Detectorists, that delicate exploration of middle-aged male friendship against the rustle of rural mysticism. A sense of spiritual presence can also inflect the British landscapes of the New Nature Writing.

But Butterworth is working according to an older tradition. Rather like his antiquarian predecessors, he has created a largely imagined universe from some scattered classical references and a great deal of accumulated myth and legend. Whether Britannia will re-enchant the British landscape for a new generation of television viewers is impossible to say, but my hunch is that those lonely stones up on the moors, such as the Grey Wethers or Scorhill on Dartmoor, are going to attract a new cohort of visitors.

Top image: Zoe Wanamaker in TV series ‘Britannia’. Source: Sky Atlantic

The article ‘Britannia, Druids and the Surprisingly Modern Origins of Myths’ by Matthew Kelly was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Published on February 04, 2018 23:30

February 3, 2018

Why are kissing gates so called and what is their significance as entrances to graveyards?

History Extra

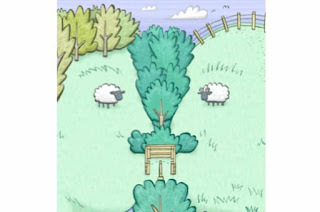

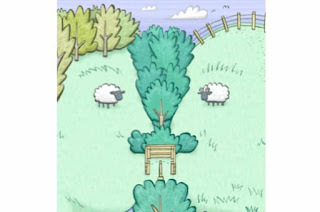

Consisting of a semi-circular, square or V-shaped enclosure on one side and a hinged gate that swings between two shutting posts, it allows one person at a time to pass through but keeps livestock out.

As for the title, the prosaic answer is that it derives from the fact that the hinged part touches – or ‘kisses’ – both sides of the enclosure rather than being securely latched like a normal gate.

That hasn’t stopped many clinging to a more romantic notion: that the first person to pass through would have to close the gate to the next person, providing an opportune moment to demand a kiss in return for entry.

Kissing gates are commonly found at the entrance to church graveyards but there is no evidence that this has any symbolic significance.

Trevor Yorke, author of English Churches Explained (Countryside Books, 2010), says: “I am not aware of any direct symbolism with kissing gates at the entrance to the graveyard. It’s a good way to keep livestock from ruining the grass while allowing people to enter.” Certainly a kissing gate is easier to negotiate than a stile for churchgoers in their Sunday best.

Answered by Dan Cossins, freelance journalist.

Consisting of a semi-circular, square or V-shaped enclosure on one side and a hinged gate that swings between two shutting posts, it allows one person at a time to pass through but keeps livestock out.

As for the title, the prosaic answer is that it derives from the fact that the hinged part touches – or ‘kisses’ – both sides of the enclosure rather than being securely latched like a normal gate.

That hasn’t stopped many clinging to a more romantic notion: that the first person to pass through would have to close the gate to the next person, providing an opportune moment to demand a kiss in return for entry.

Kissing gates are commonly found at the entrance to church graveyards but there is no evidence that this has any symbolic significance.

Trevor Yorke, author of English Churches Explained (Countryside Books, 2010), says: “I am not aware of any direct symbolism with kissing gates at the entrance to the graveyard. It’s a good way to keep livestock from ruining the grass while allowing people to enter.” Certainly a kissing gate is easier to negotiate than a stile for churchgoers in their Sunday best.

Answered by Dan Cossins, freelance journalist.

Published on February 03, 2018 23:00

February 2, 2018

What are the origins of the British taste for black pepper?

History Extra

Pepper has long been one of the most popular spices in the world – not just Britain. The Romans traded in it, and peppercorns have been found in ancient Egyptian tombs. Back then, it was a rare and precious commodity, hailing from south India. Peppercorns at various times were regarded as portable wealth, and often more reliable than a government’s coinage.

Black pepper (and the more expensive white pepper, which comes from the same plant, but is processed differently) initially came overland. That’s why the Guild of Pepperers (nowadays London livery company the Worshipful Company of Grocers), founded in 12th‑century London, chose a camel as its symbol. It was the main spice that European explorers wanted when they sought sea-passages to the ‘Indies’ that would allow them to bypass the overland trade’s expensive middle-men.

The long-cherished view that pepper was used to disguise the flavour of elderly meat is now disputed – surely the rich could afford fresh food – but poorer people might sometimes have used pepper for this purpose once extensive cultivation and trade made it affordable.

The Victorian British working classes bought pepper in large quantities, though usually in ground form; contemporary newspapers are full of scandal stories of pepper being adulterated with other additives.

Until a few decades ago, most Britons consumed ground pepper. The modern popularity of grinders filled with black peppercorns must surely have been inspired by the large mills wielded by waiters in Italian restaurants from the 1970s onwards.

Answered by: Eugene Byrne, author and journalist

Pepper has long been one of the most popular spices in the world – not just Britain. The Romans traded in it, and peppercorns have been found in ancient Egyptian tombs. Back then, it was a rare and precious commodity, hailing from south India. Peppercorns at various times were regarded as portable wealth, and often more reliable than a government’s coinage.

Black pepper (and the more expensive white pepper, which comes from the same plant, but is processed differently) initially came overland. That’s why the Guild of Pepperers (nowadays London livery company the Worshipful Company of Grocers), founded in 12th‑century London, chose a camel as its symbol. It was the main spice that European explorers wanted when they sought sea-passages to the ‘Indies’ that would allow them to bypass the overland trade’s expensive middle-men.

The long-cherished view that pepper was used to disguise the flavour of elderly meat is now disputed – surely the rich could afford fresh food – but poorer people might sometimes have used pepper for this purpose once extensive cultivation and trade made it affordable.

The Victorian British working classes bought pepper in large quantities, though usually in ground form; contemporary newspapers are full of scandal stories of pepper being adulterated with other additives.

Until a few decades ago, most Britons consumed ground pepper. The modern popularity of grinders filled with black peppercorns must surely have been inspired by the large mills wielded by waiters in Italian restaurants from the 1970s onwards.

Answered by: Eugene Byrne, author and journalist

Published on February 02, 2018 23:00

February 1, 2018

Easter treats: what are Biddenden cakes?

History Extra

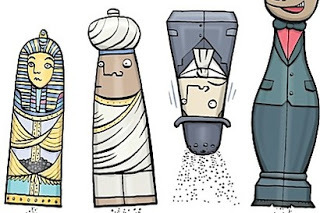

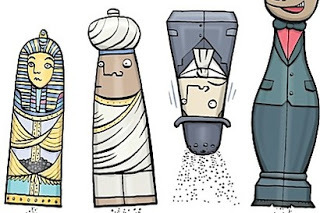

Every Easter Monday, in the village of Biddenden in Kent, a charity doles out tea, cheese and loaves of bread to local pensioners, and distributes hard-baked biscuits, known as Biddenden cakes, to villagers and visitors alike.

Stamped on each cake is a representation of the ‘Biddenden maids’, conjoined twins from the 12th century who supposedly left money in their wills to found the charity. Joined at hip and shoulder, the twins, usually named as Eliza and Mary Chulkhurst, are said to have lived to their thirties and died within six hours of one another in 1134.

There is little evidence, though, that the Chulkhursts actually existed and the earliest account of what is probably a legend was only published in 1770.

Answered by: Nick Rennison

Every Easter Monday, in the village of Biddenden in Kent, a charity doles out tea, cheese and loaves of bread to local pensioners, and distributes hard-baked biscuits, known as Biddenden cakes, to villagers and visitors alike.

Stamped on each cake is a representation of the ‘Biddenden maids’, conjoined twins from the 12th century who supposedly left money in their wills to found the charity. Joined at hip and shoulder, the twins, usually named as Eliza and Mary Chulkhurst, are said to have lived to their thirties and died within six hours of one another in 1134.

There is little evidence, though, that the Chulkhursts actually existed and the earliest account of what is probably a legend was only published in 1770.

Answered by: Nick Rennison

Published on February 01, 2018 23:30

Introduction of farming led to ‘Black Death’-type population collapse

History Extra

The introduction of farming into Western Europe 7,500 years ago led to dramatic population collapse, according to new research.

In a study published in the journal Nature Communications, researchers from University College London (UCL) found evidence of decreases in population size as great as 60 per cent.

Looking at the distribution of nearly 8,000 radiocarbon dates from archaeological sites in several regions, and using novel statistical analysis, the team noticed that while there was evidence of a dramatic increase in human activity shortly after farming was introduced, it was not sustained.

Instead the team found, in many regions, proof of population collapse on a similar scale to the Black Death.

While the exact cause of these population decreases remains unknown, the team says farming could have driven population growth to unsustainable levels.

Alternatively, soils could have become eroded, or depleted of nutrients.

Professor Stephen Shennan, lead author of the study, said: “The introduction of farming is widely believed to have led to sustained population growth, but the new evidence we’ve uncovered suggests this large-scale ‘boom-and-bust’ pattern.

“The reasons behind this trend still remain unknown, but they could have been to do with farming itself.”

Dr Adrian Timpson, a co-author of the study, said: “The reasons why these populations collapsed so dramatically remains unknown.

“One possibility could be changes in climate, which can affect the suitability and productivity of crops in different regions. But when we looked into this further, we found no conclusive proof of a link.”

Published on February 01, 2018 00:00

January 30, 2018

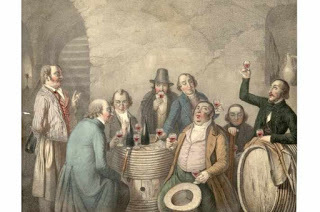

The history of middle-class wine drinking

History Extra

Should politicians tell people what and how much to drink? Recent government decisions to try and impose a minimum price for alcohol sales in England and Wales have taken the campaign against what is seen as excessive consumption into intriguing new territory. (Scotland and Northern Ireland have been having their own debates about how far the law can intervene). The focus now is not only on places where people go out to drink but also on domestic consumption. And middle-class consumption of wine is receiving much more attention too.

Ironically it has been attempts to increase rather than decrease wine consumption in Britain that have figured more prominently in the past – at least since the 19th century. Prior to that, wine, as the imported tipple of the mainly well-to-do, had seen some regulation and had at times been caught up in trade disputes, especially with France. Increased duties were imposed on imported French wine to try and harm French commerce. Spanish and Portuguese wines, by contrast, were generally favoured as these countries were more consistently allies of Britain.

But by the mid-19th century, British champions of free trade challenged such use of tariffs as diplomatic weapons. Good trade relations – sealed amicably, no doubt, over bottles of good vintage – helped prevent future wars, it was argued.

James Nicholls of Bath Spa University, a specialist on the history of alcohol consumption, hails the 1860 Treaty of Commerce – in which import duties were reduced on all wine – as a turning point. William Gladstone, the treaty’s chief architect, spoke openly of what he hoped would be a change in British drinking habits – away from an obsession with beer – so that wine would no longer be a “rich man’s luxury”.

At the same time he was sensitive to the fears of Victorian temperance campaigners that cheaper wine would encourage drunkenness. More wine drinking was meant to civilise British drinkers, claimed Gladstone. His measures were intended for the “promotion of temperance and sobriety as opposed to drunken and demoralised habits”. Other changes – forerunners of the modern ‘off licence’ system – allowed grocers and restaurateurs, rather than just pubs, to sell alcohol. They were intended to weaken the “unnatural divorce between eating and drinking”.

Behind all this lay cultural assumptions about alcohol consumption that always lurk in these debates. We have tended, says James Nicholls, to “imbue different drinks with different ethical values”. Whereas some have been linked to the bad habits of the lower orders – think of Hogarth’s image of social catastrophe in Gin Lane, or modern debates about lager louts – wine was never associated with boorish drunkenness in this way.

Though there was an initial increase in wine drinking (what’s been called ‘the era of cheap Gladstone claret’), British café society, combining wine-drinking with eating, never took off as Gladstone might have hoped. It was only in the 1960s that there was, as Nicholls puts it, a “greater democratisation of wine drinking”. More wines became available from around the world, and supermarkets added competition. As a result, wine sales have steadily increased, while beer consumption has declined.

So Gladstone might have been pleased by today’s spread of wine into British drinking culture. It is no longer the reserve of the rich. But he would have worried about the evidence that consumption – for some individuals – is rising rapidly. Health professionals, today’s equivalent of 19th‑century temperance campaigners, no longer seem to share the old assumption that wine-drinking is inherently less harmful than other kinds of alcohol.

Extra But reversing this trend will not be easy. Policing what goes on in pubs has been far easier than controlling what people do in their own homes. The long contest between political and moral control and Britain’s ‘drinking culture’ is entering a fascinating new phase.

Chris Bowlby is a presenter on BBC radio, specialising in history

This series is produced with History & Policy.

Published on January 30, 2018 23:30

January 29, 2018

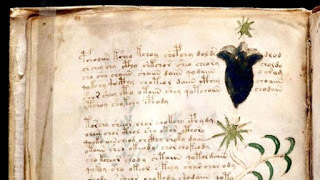

15th-century manuscript with 'alien' characters finally decoded

Fox news

By James Rogers

The Voynich manuscript's unintelligible writings and strange illustrations have defied every attempt at understanding their meaning. (BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY/YALE UNIVERSITY)

Scientists have harnessed the power of artificial intelligence to unlock the secrets of an ancient manuscript that has baffled experts.

Discovered in the 19th century, the Voynich manuscript uses “alien” characters that have long puzzled cryptographers and historians. Now, however, computing scientists at the University of Alberta say they are decoding the mysterious 15th-century text.

Computing science Professor Greg Kondrak and graduate student Bradley Hauer applied artificial intelligence to find ambiguities in the text’s human language.

RESEARCHERS OFFER YET ANOTHER EXPLANATION TO MYSTERIOUS VOYNICH MANUSCRIPT

The first stage of the research was working out the manuscript’s language. The experts used 400 different language translations from the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” to identify the language used in the text. Initially, it seemed like the text was written in Arabic, but the researcher's algorithms revealed that the manuscript is written in Hebrew.

“That was surprising,” said Kondrak, in a statement. “And just saying ‘this is Hebrew’ is the first step. The next step is how do we decipher it.”

Kondrak and Hauer worked out that Voynich manuscript was created using ‘alphagrams’ that use one phrase to define another so built an algorithm to unscramble the text. “It turned out that over 80 per cent of the words were in a Hebrew dictionary, but we didn’t know if they made sense together,” said Kondrak.

MYSTERIOUS MANUSCRIPT'S CODE HAS BEEN CRACKED, 'PROPHET OF GOD' CLAIMS The initial part of the text was then run through Google Translate. “It came up with a sentence that is grammatical, and you can interpret it,” Kondrak explained.

The sentence was: “She made recommendations to the priest, man of the house and me and people.”

The full meaning of the text will need the involvement of historians of ancient Hebrew. The vellum, or animal skin, on which the codex is written has been dated to the early 15th century.

The research study is published in Volume 4 ofTransactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics.

There have been multiple attempts to decode the Voynich manuscript. In 2014, for example, researchers argued that the illustrations of plants in the manuscript could help decode the text’s strange characters. In 2011, a self-proclaimed “prophet of God” claimed that he had decoded the book.

By James Rogers

The Voynich manuscript's unintelligible writings and strange illustrations have defied every attempt at understanding their meaning. (BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY/YALE UNIVERSITY)

Scientists have harnessed the power of artificial intelligence to unlock the secrets of an ancient manuscript that has baffled experts.

Discovered in the 19th century, the Voynich manuscript uses “alien” characters that have long puzzled cryptographers and historians. Now, however, computing scientists at the University of Alberta say they are decoding the mysterious 15th-century text.

Computing science Professor Greg Kondrak and graduate student Bradley Hauer applied artificial intelligence to find ambiguities in the text’s human language.

RESEARCHERS OFFER YET ANOTHER EXPLANATION TO MYSTERIOUS VOYNICH MANUSCRIPT

The first stage of the research was working out the manuscript’s language. The experts used 400 different language translations from the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” to identify the language used in the text. Initially, it seemed like the text was written in Arabic, but the researcher's algorithms revealed that the manuscript is written in Hebrew.

“That was surprising,” said Kondrak, in a statement. “And just saying ‘this is Hebrew’ is the first step. The next step is how do we decipher it.”

Kondrak and Hauer worked out that Voynich manuscript was created using ‘alphagrams’ that use one phrase to define another so built an algorithm to unscramble the text. “It turned out that over 80 per cent of the words were in a Hebrew dictionary, but we didn’t know if they made sense together,” said Kondrak.

MYSTERIOUS MANUSCRIPT'S CODE HAS BEEN CRACKED, 'PROPHET OF GOD' CLAIMS The initial part of the text was then run through Google Translate. “It came up with a sentence that is grammatical, and you can interpret it,” Kondrak explained.

The sentence was: “She made recommendations to the priest, man of the house and me and people.”

The full meaning of the text will need the involvement of historians of ancient Hebrew. The vellum, or animal skin, on which the codex is written has been dated to the early 15th century.

The research study is published in Volume 4 ofTransactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics.

There have been multiple attempts to decode the Voynich manuscript. In 2014, for example, researchers argued that the illustrations of plants in the manuscript could help decode the text’s strange characters. In 2011, a self-proclaimed “prophet of God” claimed that he had decoded the book.

Published on January 29, 2018 23:30

January 28, 2018

Dan Jones on the Templars and ‘Knightfall’

History Extra

Historian, presenter and author Dan Jones. (David Levenson/Getty Images)

Q. Who were the Templars?

A. To understand the Templars you’ve got to go back to the First Crusade. The Templars were originally formed in the city of Jerusalem to protect Christian pilgrims from the west as they travelled around the Holy Land. Their role later developed so that, instead of just protecting the pilgrims, they began fighting in elite units in crusader armies. They also had a sideline in a huge variety of commercial, business and financial enterprises, ranging from medieval banking through to commodity production (shipping, property leasing, etc). Most famously, they were brought down in a spectacular series of trials in the 14th century.

Q. What can you tell us about the new TV series Knightfall?

A. Knightfall is a historical drama (where history and drama are equally weighted). It’s a story about what I consider to be the most interesting part of Templar history – the fall of the order, and how it was brought down by a propaganda-driven attack led by King Philip of France. Historical drama these days is usually obsessed with origin stories, but what Knightfall does is look at the story of the Templars at its end. It’s a fascinating period of time, and it’s one of the reasons why the Templars have struck a chord with people across history.

The story follow the lives and experiences of a group of Templars in Paris who are dreaming of getting back into their former roles. In episode one, we learn that the holy grail [a mythological artefact closely linked with the Templars throughout history] has gone missing; this launches the action of the next nine episodes. It’s a very human story, with many of the characters projecting their own hopes and fears onto finding the grail.

Templars wear their distinctive uniform in this scene from 'Knightfall'. (Image credit: History)

Q. What’s the real history behind the fall of the Templars?

A. To understand the fall of the Templars, you need to understand a little about the failure of the Crusader states [Jerusalem, Tripoli, Antioch and Edessa]. In 1291, the Mamluks – a cast of Egyptian slave soldiers who had conquered Egypt and Syria – swept through these states into the eastern Mediterranean and the Crusaders lost their foothold in the Holy Land. A lot of blame was attached to the Templars because of this – their duty had been to protect the Crusader States and they had manifestly failed.

Fifteen years later, the order was destroyed by King Philip IV of France. He took aim at the Templars for a variety of reasons – partly because he was having a long-running battle with the pope (and the Templars, as loyal servants answerable to the pope, were an indirect way of attacking the papacy), and partly because he fancied a slice of the order’s wealth. On Friday 13 October 1307, agents of the king turned up at Templar houses with a list of mostly bogus and maliciously concocted accusations against the order. They were accused of worshipping false idols, spitting on the cross, sleeping with one another, denying Christ, spitting on the image of Jesus, kissing one another in lewd induction ceremonies – anything you could think of that would push the buttons of a conservative Christian mind-set in 1307.

The result was a long-running inquisition, which ran from 1307 in France and spread across every other kingdom in western Christendom. By 1312, the Templars were declared to be institutionally corrupt; they were abolished, rolled up and their property was given away. Two years later, in 1314, the last grandmaster was burned at the stake and that was the end of the order as it had been known in the Middle Ages.

Q. The plot of Knightfall follows a grail quest. How did the Templars become linked with the holy grail?

A. The first links that we know of go back to Arthurian legends and specifically the legend of Parsifal [Percival] by Chrétien de Troyes, which was rewritten in Germany between 1200 and 1210 by a man named Wolfram von Eschenbach. Wolfram placed into his story something called the Gral (the grail), which the Templars have been repeatedly linked to ever since. Although we’re not quite sure what the grail is in Wolfram’s tale, we do know that it’s defended by knights that look very similar to Templars. In my reading of the story – and I think a lot of historians would read it in the same way – the grail is a metaphor for Jerusalem. And who were better to guard Jerusalem than the Templars?

The grail itself has its own history; there is a long history of people being fascinated with it – from Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur through to Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. I think it’s understandable that the Templars and the grail became linked together – the Templars are one of the church’s most controversial orders and the grail is a symbol of the church’s history.

Q. Why did you include this mythological part of the Templars’ history in the series?

A. If we were to just disregard all of the myths and legends, the question would be: why are we making a show about the Templars at all? Why not the Knights Hospitaller? Why not the Teutonic Knights? Why not any of the other military orders? There is a reason that the Templars keep coming back to us and part of that is because they have been consistently linked with these legends and myths, which are just as much a part of their history. For TV, it’s natural to link those two elements together.

The characters in 'Knightfall' (pictured) are a combination of real historical people and characters from established Templar mythologies, says Dan Jones. (Image credit: History)

Q. Are the characters in Knightfall based on real people from history, or are they fictional?

A. The characters are a combination of real historical people and characters from established Templar mythologies. There are a whole host of characters who are absolutely based on historical figures – King Philip IV and his wife Joan I of Navarre, Isabella of France, and Pope Boniface VIII. There are also a huge range of fictional characters that originate from the fact that the Templars can be traced right back to the origins of the Arthurian stories in the 12th and 13th centuries. In 1200, fictionalised Templars were appearing in Arthurian legend all the time, so in Knightfall we meet Templars called Gawain, Landry, Parsifal and Tancrede. They are all searching for the holy grail.

Q. Are there any female characters in the series? How are they presented?

A. Absolutely – no one in their right mind would make a TV show with no strong female roles! The roles of women in the Middle Ages are quite sensitively explored in Knightfall and are some of the most interesting in the show.

In the first instance, we have the wife of Philip IV. She is referred to as Queen Joan in the show, but her real name was Juan. In the show, she’s imagined to be having an affair with Landry, the lead Templar, although this aspect is fictional. We also meet her daughter – Isabella (the future wife of Edward II) who would become known as the ‘she-wolf’ of France and one of the great medieval queens.

Q. How did you get involved with Knightfall, and what was your role as a historical consultant?

A. I first got involved with the show shortly after it was given the green light by History, and from the outset I was reading the scripts and providing informal feedback. As the show went into pre-production and then production, I came on board in a more official capacity to advise wherever I was needed. This involved anything from answering plot points from the writers’ room, to working with the actors on any queries they might have, to working with the prop, costume and set design departments.

Q. How historically accurate is Knightfall? A. Everyone involved in the show wanted to know as much as possible about the history of the Templars. Sometimes decisions were taken because of a desire for historical fidelity; sometimes decisions leant the other way.

What you see with Knightfall is a blending of history with established legends. Some of the storylines are invented, but one of the questions I was able to answer in those instances was: “Is it plausible that this could have happened?”

Q. How do Templar history and myth come together in the show?

A. The first scene of the first episode is a great example. It’s 1291 and the Templars are evacuating the city of Acre – the setting for the fall of the Crusader states to the Mamluks.

This aspect of the story is true and is based on original chronicle sources that document the Templars evacuating the city. The aspect of the story that’s not based in historical evidence is that the Templars are attempting to move the holy grail. Despite this, I think it’s remarkable how much the writers have stayed faithful to the original chronicles of the time. It’s a really interesting mish-mash between reality and fiction. That’s true of most historical dramas.

Q. As a historian, what’s your verdict on blending fact and fiction for the purpose of historical drama?

A. I think anyone who turns on a historical drama expecting to see something with the narrative architecture and factual veracity of a scholarly article has totally failed to understand the form and the medium that they are watching. The whole idea of historical drama (the clue is in the name) is drama as well as history. The job of the director – and everyone involved in the production – is where to find the balance. There will be people who are personally happy with a great ‘Hollywood story’ with historical props and costumes.

Then there will be people who want a story that is incredibly slow-moving but is absolutely faithful to every historic detail. From a numbers perspective, the former is more effective for television.

I think a lot of people assume that filmmakers who ‘get things wrong’ in period pieces must be stupid. That is absurd. If you’ve ever encountered an enormous television production, you’ll realise that it’s brought together some of the most talented directors, costume designers, actors and screenplay writers. Not all of these people can be stupid and wrong; instead, there is a carefully understood and constantly evolving sense of how to make historical drama that serves both components. Sometimes it is done well, sometimes it is done not so well. But it is never done blindly.

Q. Why do you find the Templars so compelling?

A. For me, it’s because their history has so many different facets. It’s got faith, it’s got tragedy, it’s got fake news and it’s got incredible battles. The Templars are a window into the world of crusading, but they also have this fascinating mythology that I find as interesting as the factual history. Ultimately, they are a great case study for understanding why certain subjects become so compelling generation after generation.

Dan Jones is a historian, TV presenter and author. His latest book, The Templars: The Rise and Fall of God’s Holy Warriors, is out now. He was a historical consultant for the new historical drama Knightfall, currently airing on History in the US, Canada, Southeast Asia and Italy. A UK air date is to be confirmed.

Published on January 28, 2018 23:00