MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 35

December 22, 2017

5 festive facts from BBC Two’s QI

History Extra

The festive season is well and truly upon us, but how much do you know about the history of Christmas? Here, we bring you a festive extract from the newly released QI book – The Third QI Book of General Ignorance

1) Prince Albert didn’t bring the first Christmas tree to Britain

The first Christmas tree in England went up in December 1800, when Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, gave a children’s party. One of the grown-up guests remarked, ‘After the company had walked round and admired the tree, each child obtained a portion of the sweets it bore, together with a toy, and then all returned home quite delighted.’

Christmas trees soon became wildly fashionable in high society, but it took 40 years (helped by the popular press) for them to catch on across the country. By then Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, was busy importing them, which is why they are so often associated with him.

December 1848 illustration. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Prince Albert and Queen Charlotte were both born in Germany, where families had been bringing evergreen trees indoors and putting candles on them since the sixteenth century. According to legend, the first person to do this was Martin Luther (1483–1546), better known for his role in the Protestant Reformation. One evening, it’s said, he looked up at the night sky, saw the stars twinkling between a tree’s branches, and decided to recreate the effect in his home. Luther was a controversial figure. He was also said to eat a spoonful of his own faeces every day. The Christmas tree story may be romantic fiction, but the German tradition of decorating trees indoors did begin in Luther’s lifetime.

Artificial Christmas trees became popular in Britain after the death of Queen Victoria, when large ostentatious trees suddenly seemed inappropriate. The first ones were made from goose feathers that were dyed green. These were also imported from Germany, where they had become fashionable as a way of conserving the country’s fir tree population. But artificial Christmas trees only took off in the 1930s with mass production by the Addis Brush Company. Founded by William Addis, inventor of the toothbrush, they used the same machinery to make bristly branches that they used to make toilet brushes.

Today artificial Christmas trees are seen as an environmentally conscious alternative to the real thing. Unfortunately, an independent study released in 2009 showed that, to be greener than buying a fresh-cut tree each year, you would have to reuse your plastic tree for more than 20 years.

2) ‘Jingle Bells’ wasn’t originally written as a Christmas song

‘Jingle Bells’ is the only Christmas song that doesn’t mention Christmas, Jesus or the Nativity. That’s because it was written to celebrate Thanksgiving.

Originally entitled ‘The One-Horse Open Sleigh’, ‘Jingle Bells’ was the work of American composer James Lord Pierpont (1822–93), uncle of the financier J. P. Morgan. Pierpont’s father commissioned it for a Thanksgiving service.

Pierpont led a wild life – at 14 he ran away to sea and joined a whaling ship. At 27 he left his wife and children in Boston to join the California gold rush. After re-inventing himself as a photographer, he lost all his possessions in a fire and moved to Savannah, Georgia, where he joined the Confederate army during the Civil War. Throughout this period he continued to write songs, ballads and dance tunes, including Confederate battle hymns and ‘minstrel’ songs for performance by white people with blacked-up faces. Some of his less festive tunes include ‘We Conquer or Die’ and ‘Strike for the South’.

The states of Massachusetts and Georgia both claim Pierpont was there when he wrote ‘Jingle Bells’ in 1857. Wherever he was, he made very little money out of it and never lived to see his song’s enormous popularity.

‘Jingle Bells’ was the first tune played live in space. On 16 December 1965, as US astronauts Wally Schirra and Tom Stafford were preparing to re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere in Gemini VI, Stafford contacted Mission Control to report a UFO. ‘We have an object, looks like a satellite going from north to south, probably in polar orbit . . . Looks like he might be going to re-enter soon . . . I see a command module and eight smaller modules in front. The pilot of the command module is wearing a red suit.’ Before Houston could respond, Schirra began playing ‘Jingle Bells’ on a harmonica he’d smuggled aboard in his spacesuit. He was accompanied by Stafford on sleigh bells.

‘Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer’ started life as a colouring book devised by US advertising copywriter Robert May in 1939. His reindeer was originally called ‘Reginald’ but he changed his mind at the last minute and the book sold 2 million copies in its first Christmas alone. The song was written a decade later by May’s brother-in-law Johnny Marks, who also wrote ‘Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree’. Marks was Jewish, joining a tradition of Jewish songwriters behind classic Christmas songs, including ‘White Christmas’ (Irving Berlin), ‘Let It Snow’ (Sammy Cahn) and ‘Santa Baby’ (Joan Javits).

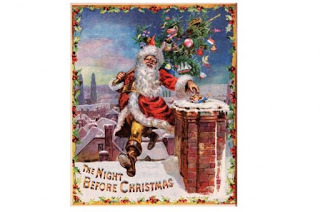

Santa returns to the North Pole after delivering presents from the now empty sack on the back of the sleigh, 1880s. (Photo by Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images)

The story of ‘Winter Wonderland’ (1934) is a sad one. The lyrics were inspired by watching children playing in the snow outside the sanatorium where songwriter Dick Smith was dying of tuberculosis.

3) Jesus’ mum didn’t call him Jesus

For a start, when Jesus lived in Galilee, the letter ‘J’ didn’t exist. In Hebrew, his name was Yeshua or Yehoshua – from which we get the name Joshua. In Aramaic (the language he probably spoke at home) it was Isho or Yeshu.

When the Gospels were translated from Hebrew into Greek, Yeshua became Iesous. When the Greek was rendered into Latin, it became Iesus. Joshua and Jesus were once the same name.

Classical Latin had no letter J – Caesar was Iulius, not Julius. Except for a handful of borrowed foreign words, modern Italian still has no J. The letter J wasn’t really in common use until the seventeenth century, at first to distinguish between words with ‘i’ as a consonant, pronounced as ‘y’ in ‘iest’ (jest) and the short vowel sound ‘i’, as in ‘it’ or ‘inch’. J wasn’t used in English until around 1630, so Shakespeare never used it either – he wrote Romeo and Iuliet, King Iohn and, like Caesar himself, Iulius Caesar. In time, J came to be spoken in English like the Old English ‘dj’ sound, as in ‘hedge’, while in Spanish J still has a ‘Y’ sound’ and in French it’s halfway between the two.

In Hebrew Jesus’ father’s name was Yusuf, not Joseph, and Jesus would have been Yeshua ben Yusuf (‘Joshua, son of Joseph’). It’s possible neither of them were carpenters. The Hebrew word used to describe what they did is naggara (tekton in Greek). It only comes up twice in the New Testament and other possible meanings are ‘architect’, ‘stone mason’ and ‘builder’ – so Jesus may have been a brickie rather than a chippie.

In 2012 more than 4,000 American children were given the first name Jesus. There were also 800 Messiahs, and 29 Christs.

4) The holiday celebrated on 26 December every year is not Boxing Day

Boxing Day in Britain is defined as ‘the first working day after Christmas’, so it’s not always on 26 December.

For example, if Christmas Day falls on a Friday, Boxing Day is on Monday the 28th, because the Saturday and Sunday aren’t working days. When Christmas falls on a Saturday, Boxing Day is on Monday the 27th (the next working day) and, to make up for Christmas Day being on a weekend, the Christmas Bank Holiday moves to Tuesday the 28th – so that, in one sense, Boxing Day sometimes comes before Christmas.

But there is a holiday that always takes place on 26 December: the Feast of St Stephen. Appropriately for someone whose feast day comes the day after Christmas, St Stephen is the patron saint of headaches. He also looks after deacons, horses and coffin makers, and is the patron saint of stone workers – which is grimly ironic as he was the first Christian martyr to be stoned to death.

St Stephen’s Day is celebrated as an official public holiday throughout most of Europe; only Commonwealth countries celebrate Boxing Day instead. The name comes from the British tradition of giving small ‘Christmas boxes’, containing money or treats, to workers for their service throughout the year.

[image error]

(Photo by George Pickow/Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In Scotland Boxing Day was once known as ‘Sweetie Scone Day’, when the lords and ladies of great estates would make cakes with dried fruit and spices to distribute among the poor.

In Ireland Boxing Day is sometimes called ‘Wren Day’, after a tradition that continued till the early twentieth century. Children hunted and killed a wren and took it from door to door, offering its feathers in exchange for money. Boxing Day in Wales was even grislier: female servants who were caught oversleeping were traditionally whipped with holly branches.

5) You don’t need to take down your Christmas decorations by Twelfth Night

Taking down decorations on Twelfth Night (5 or 6 January) is a modern superstition. For many centuries they were kept up until Candlemas Eve, 1 February. Candlemas celebrates Mary and Joseph taking the baby Jesus to the Temple at Jerusalem and presenting him to the Lord. According to St Luke’s gospel they had to sacrifice two pigeons to do so.

Early Christmas decorations consisted mainly of greenery, which kept the house looking cheerful even when the weather outside was miserable. Some people clung to older, pre-Christian beliefs about these – namely that they contained woodland spirits who, if you left the decorations up, would cause mischief in your house. Careful householders took them down and burned them just to make sure.

This photograph was sold for use in the Christmas 1948 issue of Mother magazine. (Photo by SSPL/Getty Images)

In North America Candlemas is celebrated as Groundhog Day. Groundhogs are large rodents related to squirrels and, according to folklore, if it’s cloudy when a groundhog emerges from its burrow on this day, spring will come early. If it’s sunny, the winter weather will persist for six more weeks.

Of course, the groundhog has no interest in weather forecasting: he’s looking for a mate. Recent statistics, released by the USA’s National Climatic Data Center, "show no predictive skill for the groundhog". Groundhog Day comes from an older medieval European tradition of the Candlemas Bear, where people watched for a hibernating bear as it awoke to get a similar weather prediction. The rarity of bears in France meant that this duty eventually had to be taken over by a man in a bear costume. A similar tradition in Germany is called Dachstag (‘Badger Day’), and in Ireland they use a hedgehog.

Until the 17th century ‘Christmas’ lasted almost three months, from the Feast of St Martin on 11 November to Candlemas on 2 February. Although today it doesn’t officially begin until Advent (the fourth Sunday before Christmas), the shops make it seem as if it’s starting earlier and earlier – a process known as ‘Christmas Creep’. This is getting faster, and it’s not just retailers. Analysis of Internet searches in 2007 found people started looking for ‘Santa Claus’, ‘elf ’ and ‘presents’ on 11 November. By 2013 they started on 25 August.

The Third QI Book of General Ignorance, published by Faber & Faber, is on sale now.

Published on December 22, 2017 23:30

A brief history of medieval magic

History Extra

From Narnia to Harry Potter, so many modern manifestations of magic come from the Middle Ages. Hetta Howes, who is writing a PhD at Queen Mary, University of London, investigates…

Want to get rid of an unwanted husband? Coat yourself in honey, roll naked in grain and cook him up some deadly bread with flour milled from this mixture. Want to increase the amount of supplies in your barn? Leave out child-sized shoes and bows-and-arrows for the satyrs and goblins to play with. If you’re lucky, they might steal some of your neighbour’s goods for you in return. These unusual charms and medical tips, which featured in medieval books, sound suspiciously like magic.

But alongside these weird and wonderful spells and superstitions, medieval history paints a picture of a people actually more enlightened than their Renaissance successors. So what was medieval magic really like?

Season of the witch

The now all-too-familiar figure of the ‘witch’ – that frightening old hag with warts on her nose and curses at her fingertips – didn’t appear until the 15th century. Despite being dubbed ‘The Renaissance’ and ‘The Age of Discovery’, the centuries that followed [the Renaissance lasted from the 14th to the 17th century] were witness not only to ruthless witch-hunts, but also to a new belief in the reality of magic.

In the Middle Ages, the practice of magic was not yet imagined to be essentially ‘female’. In fact, according to court records from the first half of the 14th century, the majority of those tried for maleficium (meaning sorcery, or dark magic) were men. That was because the most troubling form of magic – necromancy – required not only skill, learning and preparation, but above all education, which was less readily available to women. Necromancy involved conjuring the dead and making them perform feats of transportation or illusion, or asking them to reveal the secrets of the universe. Because many books describing necromancy were Latin translations, anyone wanting to practise the craft would need a good working knowledge of Latin.

It wasn’t until the publication of Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum (or, Hammer of Witches) in 1487 that the specific connection between women and satanic magic became widespread. Kramer warned that “women’s spiritual weakness” and “natural proclivity for evil” made them particularly susceptible to the temptations of the devil. He believed that “all witchcraft comes from carnal lust”, and that women’s “uncontrolled” sexuality made them the likely culprits of any sinister occurrence.

Black sabbath

Hand-in-hand with this increased emphasis on women came a shift in the perception of magic. Evidence suggests that medieval church authorities (whose successors would later spearhead the witch-hunts) didn’t really believe magic was real – although they still condemned anyone who claimed to practise it.

The 10th-century canon, Episcopi, describes women who, seduced by illusions from the devil, believed they could fly on the backs of “certain beasts” in the middle of the night alongside the goddess Diana. The canon dismissed these women as “stupid” and “foolish” for actually believing that they could accomplish such things. They were criticised in the text for being tricked rather than for practising any real, magical mischief.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, however, inquisitors seemed to believe that women really could make magic happen by entering into pacts with the devil. It was thought that at sabbaths – nocturnal meetings with other witches – women renounced their Christian faith, devoured babies, participated in orgies and committed other carnal and unspeakable acts.

Execution of three witches by hanging, woodcut, 1589. (© INTERFOTO/Alamy)

Afterwards, the devils worshipped would watch their women for signs, and then do their bidding. For example, if a witch put her broomstick in water and spoke certain words, a devil might cause a storm or flood. Magic of this kind wasn’t always harmful, however. Witches might be able to heal as a result of a pact, or perform other kinds of positive magic. But, because of their fundamental belief that all magic was carried out by demons and devils, inquisitors condemned it just the same.

Magic or medicine?

Certain practices – which sound to us very much like magic – would have been classed as science or medicine in the Middle Ages. William of Auvergne, a 13th-century French priest and bishop, certainly condemned most magic as superstition. However, he admitted that some works of “natural magic” should be viewed as a branch of science: as long as practitioners didn’t use this “natural magic” for evil, they weren’t doing anything criminal. Sealskin could quite happily be used as a charm to repel lightning; vulture body parts could be used as a protective amulet; and gardeners could get virgins to plant their olive trees without any anxiety – this was, after all, a scientific way of promoting their growth.

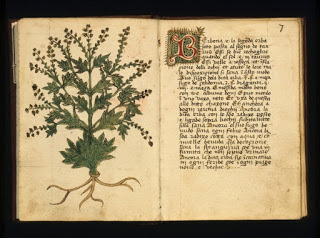

A number of healing practices from the Middle Ages also sound very much like magic to a modern reader: one doctor instructed physicians to place the herb vervain in their patient’s hand. The presence of the herb would, it was thought, cause the patient to speak his or her fate truthfully, offering the physician an accurate prognosis.

Sympathetic magic was another well-known technique – it used imitation to produce effective results. For example, liver of vulture might be prescribed as medicine for a patient suffering from liver complaints. Meanwhile narrative charms – a complex version of sympathetic magic, hinged on the belief that telling a particular story could help channel healing power to the patient – were usually accompanied by a more ‘medical’ application, like a poultice. According to one medical treatise, wool soaked in olive oil from the Mount of Olives could staunch blood when coupled with a spoken story about Longinus, a man who was famously healed of his blindness by the blood of Christ. Religious elements were blended with the magical.

Details of the properties of verbena or vervain, from a 16th-century book about herbs. When placed in a patient's hand the presence of the herb would, it was thought, cause them to speak his or her fate truthfully, offering the physician an accurate prognosis. (© The Art Archive/Alamy)

Although some of these methods were considered superstition by the Christian church in the Middle Ages, they were never associated with demonic magic until the dawning of the witch hunts. Even though women tried for witchcraft were accused of much more diabolical doings than using charms or stories to heal, many women became afraid of carrying out such practices, for fear of attracting suspicion of darker deeds.

Medieval history offers us a magical potion of stories and practices infused with charms, herbs and superstition. While some of the examples might seem curious to us, they are evidence of a people trying to make sense of and control their surroundings – just as we do today.

Hetta Howes is writing a PhD at Queen Mary, University of London on the subject of water and religious imagery in medieval devotional texts by and for women.

Published on December 22, 2017 00:30

December 21, 2017

Winter Solstice: Stone Age people in Ireland built a Fantastic Monument to the New Year

Ancient Origins

Today, the Irish and visitors celebrated the Winter Solstice as they did thousands of years ago at Newgrange, a huge Stone Age megalithic monument into the deepest part of whose main chamber the sun shines at sunrise. This year about 30,000 people participated in a lottery, from whom 50 were chosen, to be in the 5,000-year-old monument at sunrise to witness the primeval event the mornings of Dec. 18 to 23.

While the monument near the Boyne River in County Meath is open all year and is one of Ireland’s most popular attractions, it draws special international attention today.

Newgrange predates the great pyramids at Giza in Egypt by some 500 years and Stonehenge by about 1,000 years. When it was built, sunrise on the shortest day of the year, what we now call December 21, entered the main chamber precisely at sunrise. Experts say it is not by chance that the sun shines there. Now it enters about four minutes after sunrise because of changes in the Earth’s orbiting of the sun since then.

Solstice sunrise light entering the Newgrange monument, a photo by Cyril Byrne of the Irish Times, as seen on NASA’s Astronomy Photo of the Day website.

Archaeologists say they believe Newgrange and two other nearby monuments, Knowth and Dowth, were tombs, built in ancient times to provide somewhere to bury the dead and as ritual and community gatherings, perhaps to honor ancestors. They believe it took decades to construct by generations of the Neolithic people, about whom little is known.

The tomb itself is massive and impressive and is surrounded by a henge or ring of huge stones. Experts say they believe the huge stones were moved from the nearby river, perhaps by rolling them on logs.

This short YouTube video from National Geographic gives great views of the Newgrange tomb and monument.

The number of bone fragments found inside Newgrange hardly constitute evidence of a communal burial chamber, Ancient Origins reported in 2013 in a two-part article about the Neolithic structure. In total, the bones of only five individuals were found inside the monument during excavations in the 1960s. Some bones could have been taken away after the rediscovery of the entrance to the passage and chamber in 1699. But at over 85 meters (278 feet) in diameter, and containing more than 250,000 tons of stone and earth, this monument would seem such a lavish and grandiose tomb for a few mere mortals, if that were indeed its sole purpose.

The structure of the passage tomb was buried in earth for many centuries, until archaeologist M.J. O’Kelly began excavating it in 1962. He worked there until 1975. In 1967, he saw for the first time in thousands of years the dawn sunlight striking into the chamber on December 21. The light enters a perfectly placed window and hits deep in the tomb where the human remains were found.

O’Kelly wrote in his notes: “The effect is very dramatic as the direct light of the sun brightens and cast a glow of light all over the chamber. I can see parts of the roof and a reflected light shines right back into the back of the end chamber.”

O’Kelly and others have restored the Newgrange mound. It is 12 meters (40 feet) high. The total area of the monument and surrounds covers about 1 acre, and its roof is intact and still waterproof 5,000 years after construction. Triple-spiral carvings like the Celts did still adorn many of the stones making up the tomb.

The triple spiral carvings on a wall at Newgrange (Photo by Johnbod/Wikimedia Commons)

Up until 1967, after archaeological excavation, conservation and restoration work, it was not possible for the light of the sun to illuminate the interior. This was because of the slow subsidence of the roofing stones of the passage, which had slowly sunk as the supporting orthostats leaned inwards over the long centuries. Before 1967, when Professor O’Kelly became the first person to witness the solstice event in modern times, nobody could have witnessed this phenomenon. And yet, local folklore held that the sun shone into Newgrange on the shortest day of the year. O’Kelly pointed to this as being one of the reasons for his visit to the chamber in December 1967.

But the astronomical mysteries of Newgrange run deeper. In 1958, in his book about primitive mythology, Joseph Campbell recounted a folk tale from the Boyne Valley in which a local had told him the light of the Morning Star, Venus, shone into the chamber of Newgrange at dawn on one day every eight years and cast a beam upon a stone on the floor of the chamber containing two worn sockets. This might seem like an incredible suggestion, except for the fact that it is astronomically accurate. Venus follows an eight-year cycle and on one year out of every eight, it rises in the pre-dawn sky of winter solstice and its light would be able to be seen from within the chamber.

Featured image: December 21, the longest night and shortest day of the year, is a special event at Newgrange in County Meath, Ireland. This photo was shot August 24, 2014. (Photo by Paul A. Byrne/Wikimedia Commons)

By: Mark Miller

Today, the Irish and visitors celebrated the Winter Solstice as they did thousands of years ago at Newgrange, a huge Stone Age megalithic monument into the deepest part of whose main chamber the sun shines at sunrise. This year about 30,000 people participated in a lottery, from whom 50 were chosen, to be in the 5,000-year-old monument at sunrise to witness the primeval event the mornings of Dec. 18 to 23.

While the monument near the Boyne River in County Meath is open all year and is one of Ireland’s most popular attractions, it draws special international attention today.

Newgrange predates the great pyramids at Giza in Egypt by some 500 years and Stonehenge by about 1,000 years. When it was built, sunrise on the shortest day of the year, what we now call December 21, entered the main chamber precisely at sunrise. Experts say it is not by chance that the sun shines there. Now it enters about four minutes after sunrise because of changes in the Earth’s orbiting of the sun since then.

Solstice sunrise light entering the Newgrange monument, a photo by Cyril Byrne of the Irish Times, as seen on NASA’s Astronomy Photo of the Day website.

Archaeologists say they believe Newgrange and two other nearby monuments, Knowth and Dowth, were tombs, built in ancient times to provide somewhere to bury the dead and as ritual and community gatherings, perhaps to honor ancestors. They believe it took decades to construct by generations of the Neolithic people, about whom little is known.

The tomb itself is massive and impressive and is surrounded by a henge or ring of huge stones. Experts say they believe the huge stones were moved from the nearby river, perhaps by rolling them on logs.

This short YouTube video from National Geographic gives great views of the Newgrange tomb and monument.

The number of bone fragments found inside Newgrange hardly constitute evidence of a communal burial chamber, Ancient Origins reported in 2013 in a two-part article about the Neolithic structure. In total, the bones of only five individuals were found inside the monument during excavations in the 1960s. Some bones could have been taken away after the rediscovery of the entrance to the passage and chamber in 1699. But at over 85 meters (278 feet) in diameter, and containing more than 250,000 tons of stone and earth, this monument would seem such a lavish and grandiose tomb for a few mere mortals, if that were indeed its sole purpose.

The structure of the passage tomb was buried in earth for many centuries, until archaeologist M.J. O’Kelly began excavating it in 1962. He worked there until 1975. In 1967, he saw for the first time in thousands of years the dawn sunlight striking into the chamber on December 21. The light enters a perfectly placed window and hits deep in the tomb where the human remains were found.

O’Kelly wrote in his notes: “The effect is very dramatic as the direct light of the sun brightens and cast a glow of light all over the chamber. I can see parts of the roof and a reflected light shines right back into the back of the end chamber.”

O’Kelly and others have restored the Newgrange mound. It is 12 meters (40 feet) high. The total area of the monument and surrounds covers about 1 acre, and its roof is intact and still waterproof 5,000 years after construction. Triple-spiral carvings like the Celts did still adorn many of the stones making up the tomb.

The triple spiral carvings on a wall at Newgrange (Photo by Johnbod/Wikimedia Commons)

Up until 1967, after archaeological excavation, conservation and restoration work, it was not possible for the light of the sun to illuminate the interior. This was because of the slow subsidence of the roofing stones of the passage, which had slowly sunk as the supporting orthostats leaned inwards over the long centuries. Before 1967, when Professor O’Kelly became the first person to witness the solstice event in modern times, nobody could have witnessed this phenomenon. And yet, local folklore held that the sun shone into Newgrange on the shortest day of the year. O’Kelly pointed to this as being one of the reasons for his visit to the chamber in December 1967.

But the astronomical mysteries of Newgrange run deeper. In 1958, in his book about primitive mythology, Joseph Campbell recounted a folk tale from the Boyne Valley in which a local had told him the light of the Morning Star, Venus, shone into the chamber of Newgrange at dawn on one day every eight years and cast a beam upon a stone on the floor of the chamber containing two worn sockets. This might seem like an incredible suggestion, except for the fact that it is astronomically accurate. Venus follows an eight-year cycle and on one year out of every eight, it rises in the pre-dawn sky of winter solstice and its light would be able to be seen from within the chamber.

Featured image: December 21, the longest night and shortest day of the year, is a special event at Newgrange in County Meath, Ireland. This photo was shot August 24, 2014. (Photo by Paul A. Byrne/Wikimedia Commons)

By: Mark Miller

Published on December 21, 2017 00:00

December 19, 2017

The Dickensian Christmas

History Extra

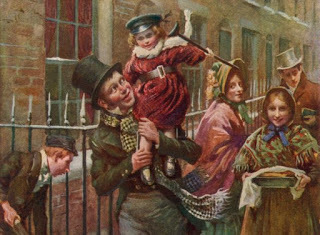

Thanks to his seminal 1843 novel A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens is often credited with inventing winter festivities as we know them. His book of literary favourites including Ebenezer Scrooge, Tiny Tim and the host of Christmas ghosts are thought to define the Dickensian Christmas but is Dickens’ pioneering reputation really deserved?

Charles Dickens’ association with Christmas is infamous. A Christmas Carol was an immediate smash with the public, and quickly spawned a range of ‘pirated’ copies forcing Dickens into a number of legal actions to protect his creation.

“Dickens, it may truly be said, is Christmas,” said the literature scholar, VH Allemandy, in 1921. However, important though he undoubtedly was, Dickens did not create Christmas. Rather, he reflected a general early 19th‑century interest in the season and was part of a widespread, particularly middle-class, desire to reinvigorate its ancient customs.

At the time Dickens was writing his now world famous story he could have consulted an ever-burgeoning number of popular histories of Christmas such as TK Hervey’s Book of Christmas (1836), and his A History of the Christmas Festival, the New Year and their Peculiar Customs (1843) and Thomas Wright’s Specimens of Old Carols (1841). Dickens, being perfectly in-tune with Britain, therefore published his story at precisely the right moment. He was a massive player in a revival that was already under way, but he was not the sole instigator of it.

Mark Connelly is professor of modern British history at the University of Kent, His books include 'Steady the buffs! A regiment, a region and the Great War'.

Published on December 19, 2017 23:30

December 18, 2017

Discovery of 1,000 Sealings Reveals an Ancient City’s Devotion to the Graeco-Roman Pantheon

Ancient Origins

Classical scholars from the Cluster of Excellence "Religion and Politics" of the University of Münster discovered a large number of sealings in south-east Turkey. "This unique group of artifacts comprising more than 1,000 pieces from the municipal archive of the ancient city of Doliche gives many insights into the local Graeco-Roman pantheon -- from Zeus to Hera to Iuppiter Dolichenus, who turned into one of the most important Roman deities from this site," classical scholar and excavation director Prof. Dr. Engelbert Winter from the Cluster of Excellence explains at the end of the excavation season.

"The fact that administrative authorities sealed hundreds of documents with the images of gods shows how strongly religious beliefs shaped everyday life. The cult of Iuppiter Dolichenus did not only take place in the nearby central temple, but also left its mark on urban life," says Prof Winter. "It also becomes apparent how strongly Iuppiter Dolichenus, originally worshipped at this location, was connected with the entire Roman Empire in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD: many of the images show the god shaking hands with various Roman emperors."

Statue of Iupiter Dolichenus standing on a bull. Kunsthistorisches Museum. (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The excavation team has been exploring the temple of the soldier god Iuppiter Dolichenus for 17 years. This year, the team focused on the urban area. "Under a mosaic dated to 400 AD within a complex of buildings, we were able to uncover an even older mosaic floor of equally high quality," Prof. Winter explains. "According to the present findings, there is much evidence of a late antique church. This could turn out to be an important contribution to understanding the history of early Christianity in this region." The excavations in the three-local aisled building complex began in 2015. Up to the present, 150 square meters of the large central nave bordered by columns have been uncovered. Engelbert Winter: "Apart from the architecture, small finds from the surrounding area also point to the existence of a church, such as the fragments of a marble table or the mentioning of a deacon attested by an inscription."

Part of the mosaic floor surrounded columns excavated in 2015. (Image:© Peter Jülich)

"City center discovered"

The researchers have now also discovered the public center of the city of Doliche, which they had first located in the eastern part of the city by geophysical prospecting. "This assumption has been confirmed," the excavation director explains. "We were able to uncover parts of a very large building: it is a public bath from the Roman Iron Age with well-preserved mosaics. Since hardly any Roman thermal baths are known so far in the region, this discovery is of great academic importance." The research team from Münster also gained new insights to the extension of the urban area and the chronology of the city: an intensive survey carried out this year on the settlement hill of the ancient city, Keber Tepe, led to quite surprising results. "A large number of finds from the Stone Age indicate that Keber Tepe was obviously an extremely important place very early on. Doliche reached its greatest extent later, in the Roman and early Byzantine periods."

Mosaic floor of a Roman thermal bath uncovered at Doliche. (Image: Peter Jülich)

Excavation director Winter says about the large number of discovered sealings: "Many sealings can be attributed to the administrative or official seals of the city due to their size, frequent occurrence, and in some cases also due to inscriptions. In addition to the images of the 'city goddess' Tyche, the depictions of Augustus and Dea Roma deserve special attention, since they point to the important role of the Roman emperor and the personified goddess of the Roman state for the town of Doliche, which lies on the eastern border of the Roman Empire. However, the central motif is the most important god of the city, Iuppiter Dolichenus. In the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, his cult spread into large parts of the Mediterranean world, extending as far as Britain," explains Prof. Winter. Therefore, it is not surprising that hundreds of documents were sealed with images showing a handshake between this deity and an emperor. "It was a sign of the god's affinity to the Roman state."

The images also provide insights into the cult itself. In addition to sealings showing busts of Iuppiter and his wife Iuno, there are depictions of the divine twins Castor and Pollux, the sons of Zeus. "The sons of Zeus, also known as Dioscuri or Castores Dolicheni, are often portrayed as companions of Iuppiter and therefore play an important role in the cult," Prof. Winter explains.

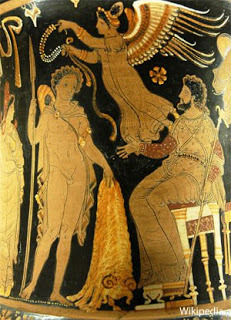

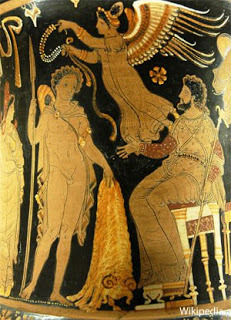

Votive relief to Jupiter Dolichenus and Juno, Jupiter with tiara, sword, an ax and lightning bundle, Juno has a mirror and a scepter, 3rd century AD, from Rome, Neues Museum, Berlin. (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Archaeological park for tourists

Under the supervision of Prof. Winter from the Cluster of Excellence "Religion and Politics," the Asia Minor Research Center of the University of Münster has been excavating the main temple of Iuppiter Dolichenus with the support of the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) since 2001. Each year, the international group of archaeologists, historians, architects, restorers, archaeozoologists, GIS analysts and excavation assistants have uncovered finds from all periods of the 2,000-year history of the place of worship. Among them were the massive foundations of the first Iron Age sanctuary, numerous monumental architectural fragments of the Roman main temple, but also the extensive ruins of an important Byzantine monastery which was built by followers of the Christian faith after the fall of the ancient sanctuary. In order to make the excavation site near the ancient town of Doliche accessible to a broad public, an archaeological park is being developed. Prof. Winter's research project at the Cluster of Excellence "Religion and Politics" is closely connected with the excavation. It is titled "Syriac Cults in the Western Imperium Romanum."

Top image: Sealings from the archive of Doliche. (Image: Asia Minor Research Centre)

The article, originally titled ‘More than 1,000 ancient sealings discovered,’ was originally published on Science Daily.

Classical scholars from the Cluster of Excellence "Religion and Politics" of the University of Münster discovered a large number of sealings in south-east Turkey. "This unique group of artifacts comprising more than 1,000 pieces from the municipal archive of the ancient city of Doliche gives many insights into the local Graeco-Roman pantheon -- from Zeus to Hera to Iuppiter Dolichenus, who turned into one of the most important Roman deities from this site," classical scholar and excavation director Prof. Dr. Engelbert Winter from the Cluster of Excellence explains at the end of the excavation season.

"The fact that administrative authorities sealed hundreds of documents with the images of gods shows how strongly religious beliefs shaped everyday life. The cult of Iuppiter Dolichenus did not only take place in the nearby central temple, but also left its mark on urban life," says Prof Winter. "It also becomes apparent how strongly Iuppiter Dolichenus, originally worshipped at this location, was connected with the entire Roman Empire in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD: many of the images show the god shaking hands with various Roman emperors."

Statue of Iupiter Dolichenus standing on a bull. Kunsthistorisches Museum. (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The excavation team has been exploring the temple of the soldier god Iuppiter Dolichenus for 17 years. This year, the team focused on the urban area. "Under a mosaic dated to 400 AD within a complex of buildings, we were able to uncover an even older mosaic floor of equally high quality," Prof. Winter explains. "According to the present findings, there is much evidence of a late antique church. This could turn out to be an important contribution to understanding the history of early Christianity in this region." The excavations in the three-local aisled building complex began in 2015. Up to the present, 150 square meters of the large central nave bordered by columns have been uncovered. Engelbert Winter: "Apart from the architecture, small finds from the surrounding area also point to the existence of a church, such as the fragments of a marble table or the mentioning of a deacon attested by an inscription."

Part of the mosaic floor surrounded columns excavated in 2015. (Image:© Peter Jülich)

"City center discovered"

The researchers have now also discovered the public center of the city of Doliche, which they had first located in the eastern part of the city by geophysical prospecting. "This assumption has been confirmed," the excavation director explains. "We were able to uncover parts of a very large building: it is a public bath from the Roman Iron Age with well-preserved mosaics. Since hardly any Roman thermal baths are known so far in the region, this discovery is of great academic importance." The research team from Münster also gained new insights to the extension of the urban area and the chronology of the city: an intensive survey carried out this year on the settlement hill of the ancient city, Keber Tepe, led to quite surprising results. "A large number of finds from the Stone Age indicate that Keber Tepe was obviously an extremely important place very early on. Doliche reached its greatest extent later, in the Roman and early Byzantine periods."

Mosaic floor of a Roman thermal bath uncovered at Doliche. (Image: Peter Jülich)

Excavation director Winter says about the large number of discovered sealings: "Many sealings can be attributed to the administrative or official seals of the city due to their size, frequent occurrence, and in some cases also due to inscriptions. In addition to the images of the 'city goddess' Tyche, the depictions of Augustus and Dea Roma deserve special attention, since they point to the important role of the Roman emperor and the personified goddess of the Roman state for the town of Doliche, which lies on the eastern border of the Roman Empire. However, the central motif is the most important god of the city, Iuppiter Dolichenus. In the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, his cult spread into large parts of the Mediterranean world, extending as far as Britain," explains Prof. Winter. Therefore, it is not surprising that hundreds of documents were sealed with images showing a handshake between this deity and an emperor. "It was a sign of the god's affinity to the Roman state."

The images also provide insights into the cult itself. In addition to sealings showing busts of Iuppiter and his wife Iuno, there are depictions of the divine twins Castor and Pollux, the sons of Zeus. "The sons of Zeus, also known as Dioscuri or Castores Dolicheni, are often portrayed as companions of Iuppiter and therefore play an important role in the cult," Prof. Winter explains.

Votive relief to Jupiter Dolichenus and Juno, Jupiter with tiara, sword, an ax and lightning bundle, Juno has a mirror and a scepter, 3rd century AD, from Rome, Neues Museum, Berlin. (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Archaeological park for tourists

Under the supervision of Prof. Winter from the Cluster of Excellence "Religion and Politics," the Asia Minor Research Center of the University of Münster has been excavating the main temple of Iuppiter Dolichenus with the support of the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) since 2001. Each year, the international group of archaeologists, historians, architects, restorers, archaeozoologists, GIS analysts and excavation assistants have uncovered finds from all periods of the 2,000-year history of the place of worship. Among them were the massive foundations of the first Iron Age sanctuary, numerous monumental architectural fragments of the Roman main temple, but also the extensive ruins of an important Byzantine monastery which was built by followers of the Christian faith after the fall of the ancient sanctuary. In order to make the excavation site near the ancient town of Doliche accessible to a broad public, an archaeological park is being developed. Prof. Winter's research project at the Cluster of Excellence "Religion and Politics" is closely connected with the excavation. It is titled "Syriac Cults in the Western Imperium Romanum."

Top image: Sealings from the archive of Doliche. (Image: Asia Minor Research Centre)

The article, originally titled ‘More than 1,000 ancient sealings discovered,’ was originally published on Science Daily.

Published on December 18, 2017 23:30

A Tradition Revived? Inverted Christmas Trees May Have Pagan Roots

Ancient Origins

Hanging a Christmas tree from the ceiling makes some sense – it can keep your floor space clear and may protect your pets or young children from harm – but it is not common. The costly trend of hanging a tree upside-down is a whole other matter. As with many things that go against the norm, there is a lot of controversy and confusion about the practice of hanging an inverted tree from the ceiling. But it seems the idea is not a new one; in fact, the unconventional decorating idea may trace its roots, at least loosely, to pagan traditions.

CBC News reports that inverted hanging Christmas trees can be found “dangling from the ceilings of exclusive hotel lobbies and public atriums from London to Vancouver.” It is certainly an eye-catching way to decorate for the holidays, but are the people who practice this method of tree-trimming really following a tradition from the Medieval period, or is the idea purely commercial?

An upside-down Christmas tree. Galeries Lafayette. (Laika ac/CC BY SA 2.0)

Followers of the upside-down Christmas tree practice say that it was a popular way of doing things in in the 12th century in Eastern Europe. Yet it is important to note here, the hanging element was generally just the top of a fir tree – not a huge, heavily decorated tree like you may find in a shopping center or luxury hotel today. In Poland, the top of the tree, or a branch from a fir tree, was hung pointing down from the rafters, usually facing the dinner table, in preparation for the holiday of Wigilia or Wilia. These decorative features were adorned with fruit, nuts, shiny sweets, straw, ribbons, golden pine cones, and other ornaments. An article by The Spruce says that the treats and sweets on the tree could not be eaten until the day after the festivities.

There is a legend that may explain the peculiar practice. The traditional story says Saint Boniface was the first to hang a “Christmas tree” upside-down, in the 8th century. Apparently, Boniface saw pagans preparing to celebrate the winter solstice by sacrificing a young man under an oak tree – a sacred tree in their beliefs. He was angered by their actions and cut the tree down. A fir tree grew in its place and Boniface supposedly decided to hang the inverted tree and use the triangular shape as a tool to explain the Holy Trinity to the pagans while trying to convert them to his religion.

Boniface chops down a cult tree in Hessen, engraving by Bernhard Rode, 1781. (Public Domain)

Some historians say that the tradition of hanging a Christmas tree was still popular in certain European countries as recently as 100 years ago. But the reason had changed by then. Bernd Brunner wrote in his book, Inventing the Christmas Tree, that people living in the 19th century needed the floor space. However, it’s worth mentioning that the tree was right-side up.

It seems the modern tree-hanging practice is meant to essentially serve the same purpose in stores. Dan Loughman, vice president of product development at Roman Incorporated, told NPR in 2005, “By having a tree upside down, you're taking a very small footprint on the floor, and you're placing all the ornaments at eye level. And then the retailers can move their store products around the bottom of the tree or on shelves, you know, just behind it.”

An upside-down Christmas tree is suspended from the ceiling at the Fairmont Vancouver Airport hotel in Richmond, B.C. (Darryl Dyck/Canadian Press)

The tradition of putting up Christmas trees may be tied to the German reformer Martin Luther, who popularized the use of the Christmas tree in 1605 after being inspired by the beauty of the stars on Christmas Eve night. Pine trees also used to have a place in ‘miracle plays’ that were performed in front of cathedrals at Christmas time –the Church eventually banned the practice, but the tradition of having a decorated Christmas tree has continued.

Top Image: An upside-down Christmas tree. Source: This is Why I’m Broke

By Alicia McDermott

Hanging a Christmas tree from the ceiling makes some sense – it can keep your floor space clear and may protect your pets or young children from harm – but it is not common. The costly trend of hanging a tree upside-down is a whole other matter. As with many things that go against the norm, there is a lot of controversy and confusion about the practice of hanging an inverted tree from the ceiling. But it seems the idea is not a new one; in fact, the unconventional decorating idea may trace its roots, at least loosely, to pagan traditions.

CBC News reports that inverted hanging Christmas trees can be found “dangling from the ceilings of exclusive hotel lobbies and public atriums from London to Vancouver.” It is certainly an eye-catching way to decorate for the holidays, but are the people who practice this method of tree-trimming really following a tradition from the Medieval period, or is the idea purely commercial?

An upside-down Christmas tree. Galeries Lafayette. (Laika ac/CC BY SA 2.0)

Followers of the upside-down Christmas tree practice say that it was a popular way of doing things in in the 12th century in Eastern Europe. Yet it is important to note here, the hanging element was generally just the top of a fir tree – not a huge, heavily decorated tree like you may find in a shopping center or luxury hotel today. In Poland, the top of the tree, or a branch from a fir tree, was hung pointing down from the rafters, usually facing the dinner table, in preparation for the holiday of Wigilia or Wilia. These decorative features were adorned with fruit, nuts, shiny sweets, straw, ribbons, golden pine cones, and other ornaments. An article by The Spruce says that the treats and sweets on the tree could not be eaten until the day after the festivities.

There is a legend that may explain the peculiar practice. The traditional story says Saint Boniface was the first to hang a “Christmas tree” upside-down, in the 8th century. Apparently, Boniface saw pagans preparing to celebrate the winter solstice by sacrificing a young man under an oak tree – a sacred tree in their beliefs. He was angered by their actions and cut the tree down. A fir tree grew in its place and Boniface supposedly decided to hang the inverted tree and use the triangular shape as a tool to explain the Holy Trinity to the pagans while trying to convert them to his religion.

Boniface chops down a cult tree in Hessen, engraving by Bernhard Rode, 1781. (Public Domain)

Some historians say that the tradition of hanging a Christmas tree was still popular in certain European countries as recently as 100 years ago. But the reason had changed by then. Bernd Brunner wrote in his book, Inventing the Christmas Tree, that people living in the 19th century needed the floor space. However, it’s worth mentioning that the tree was right-side up.

It seems the modern tree-hanging practice is meant to essentially serve the same purpose in stores. Dan Loughman, vice president of product development at Roman Incorporated, told NPR in 2005, “By having a tree upside down, you're taking a very small footprint on the floor, and you're placing all the ornaments at eye level. And then the retailers can move their store products around the bottom of the tree or on shelves, you know, just behind it.”

An upside-down Christmas tree is suspended from the ceiling at the Fairmont Vancouver Airport hotel in Richmond, B.C. (Darryl Dyck/Canadian Press)

The tradition of putting up Christmas trees may be tied to the German reformer Martin Luther, who popularized the use of the Christmas tree in 1605 after being inspired by the beauty of the stars on Christmas Eve night. Pine trees also used to have a place in ‘miracle plays’ that were performed in front of cathedrals at Christmas time –the Church eventually banned the practice, but the tradition of having a decorated Christmas tree has continued.

Top Image: An upside-down Christmas tree. Source: This is Why I’m Broke

By Alicia McDermott

Published on December 18, 2017 00:00

December 16, 2017

Did the Viking Age Really Start on 8 June 793 AD?

Ancient Origins

BY THORNEWS

“Never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race (…). The heathens poured out the blood of saints around the altar, and trampled on the bodies of saints in the temple of God, like dung in the streets”.

With these words, Alcuin of York, a Northumbrian scholar serving King Charlemagne of the Franks and Lombards described the surprising and brutal attack in June 793 on the church of St Cuthbert on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne.

The brutal Viking raid sent a shockwave through England and the rest of Christian Europe.

The 8th of June is according to the Annals of Lindisfarne the exact date when Vikings raided the Holy Island. Consequently, the Viking Age is defined to have started on this date, maybe at sunrise so that the raiders could sneak into the Northumbrian island under cover of dusk.

But is this really the exact date when Vikings became Vikings? Of course not, but the date marks a deep sword stab into the midst of the heart of the Christian Anglo-Saxon England. They came from the fjords of Western Norway, and when they left, only silence could be heard. 1

These men from the fjords represented a new and uncontrollable threat, and the attack clearly demonstrated that the English kings (and other European kings) were more or less unable to protect their own people, even priests and monks, facing these brutal raiders.

Year 805 AD, Yorkshire, England: Imagine, you wake up in the morning and you see this Norseman waiting outside your door. (Illustration by: Stian Dahlslett)

The Vikings did not start to be Vikings in the year 793. The Viking Age started long before and followed the development of keels and sails until their longships easily could cross the North Sea and other open waters.

The Oseberg ship (built around 820-834) is the first proof of sailing ships in Scandinavia, but it is likely that this type of vessels were built as early as the mid 700’s.

Three Ships of Northmen

The attack on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne, just off the Northumbrian coast in northeast England, was not the first on the British Isles. In the year 789, three ships of Northmen who had landed on the coast of Wessex, killed the king’s reeve (chief magistrate) sent out to bring the strangers to the West Saxon court.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports:

During the reign of King Beorhtric 789 – 802], there came for the first time three ships of Northmen and then the reeve rode to them and wished to force them to the king’s residence, for he did not know what they were; and they slew him .

The Vikings did not leave their written version of events. Nor do the later sagas tell anything about their eight century raids.

However, the assault on the Holy Island was something new and represented a great threat because the pagans attacked the sacred heart of the Northumbrian kingdom and dishonored the very place where the Christian religion started on the British Isles.

This was the holy island where Cuthbert (c. 634 – 687) had been bishop, the man who after his death became one of the most important medieval saints of Northern England.

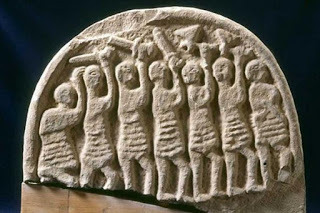

A carved stone found on the island, known as the “Doomsday Stone”, could represent the Viking attack on Lindisfarne. (Photo: english-heritage.org.uk)

As soon as the shocking news reached Alcuin serving at the Charlemagne’s court, he wrote to Higbald, bishop of Lindisfarne:

The church of St Cuthbert is spattered with the blood of the priests of God, stripped of all its furnishing, exposed to the plundering of pagans, a place more sacred than any in Britain .

The raid on Lindisfarne made the Englishmen understand that their lives would never be the same again, and the start of the Viking Age is therefore set to the “dark date” of the attack, i.e. 8 June 793.

However, if the Vikings had got the opportunity to describe themselves, they probably would have said something like: “We come from the north and honor Odin, Thor, Freyr, and our ancestors. Feel free to call us heathens or Vikings, but we have always been, and always will be free men from the north”.

Furthermore, the Viking Age did not come to an end at the Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September 1066, a date determined by today’s historians and archaeologists.

But, this is quite a different story.

Top image: They came from the fjords of Western Norway, and when they left, only silence could be heard. (Illustrating photo from “Trace” Viking movie, by Markus Dahlslett).

The article ‘ Did the Viking Age Really Start on 8 June 793 AD? ’ by Thor Lanesskog was originally published on ThorNews and has been republished with permission.

BY THORNEWS

“Never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race (…). The heathens poured out the blood of saints around the altar, and trampled on the bodies of saints in the temple of God, like dung in the streets”.

With these words, Alcuin of York, a Northumbrian scholar serving King Charlemagne of the Franks and Lombards described the surprising and brutal attack in June 793 on the church of St Cuthbert on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne.

The brutal Viking raid sent a shockwave through England and the rest of Christian Europe.

The 8th of June is according to the Annals of Lindisfarne the exact date when Vikings raided the Holy Island. Consequently, the Viking Age is defined to have started on this date, maybe at sunrise so that the raiders could sneak into the Northumbrian island under cover of dusk.

But is this really the exact date when Vikings became Vikings? Of course not, but the date marks a deep sword stab into the midst of the heart of the Christian Anglo-Saxon England. They came from the fjords of Western Norway, and when they left, only silence could be heard. 1

These men from the fjords represented a new and uncontrollable threat, and the attack clearly demonstrated that the English kings (and other European kings) were more or less unable to protect their own people, even priests and monks, facing these brutal raiders.

Year 805 AD, Yorkshire, England: Imagine, you wake up in the morning and you see this Norseman waiting outside your door. (Illustration by: Stian Dahlslett)

The Vikings did not start to be Vikings in the year 793. The Viking Age started long before and followed the development of keels and sails until their longships easily could cross the North Sea and other open waters.

The Oseberg ship (built around 820-834) is the first proof of sailing ships in Scandinavia, but it is likely that this type of vessels were built as early as the mid 700’s.

Three Ships of Northmen

The attack on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne, just off the Northumbrian coast in northeast England, was not the first on the British Isles. In the year 789, three ships of Northmen who had landed on the coast of Wessex, killed the king’s reeve (chief magistrate) sent out to bring the strangers to the West Saxon court.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports:

During the reign of King Beorhtric 789 – 802], there came for the first time three ships of Northmen and then the reeve rode to them and wished to force them to the king’s residence, for he did not know what they were; and they slew him .

The Vikings did not leave their written version of events. Nor do the later sagas tell anything about their eight century raids.

However, the assault on the Holy Island was something new and represented a great threat because the pagans attacked the sacred heart of the Northumbrian kingdom and dishonored the very place where the Christian religion started on the British Isles.

This was the holy island where Cuthbert (c. 634 – 687) had been bishop, the man who after his death became one of the most important medieval saints of Northern England.

A carved stone found on the island, known as the “Doomsday Stone”, could represent the Viking attack on Lindisfarne. (Photo: english-heritage.org.uk)

As soon as the shocking news reached Alcuin serving at the Charlemagne’s court, he wrote to Higbald, bishop of Lindisfarne:

The church of St Cuthbert is spattered with the blood of the priests of God, stripped of all its furnishing, exposed to the plundering of pagans, a place more sacred than any in Britain .

The raid on Lindisfarne made the Englishmen understand that their lives would never be the same again, and the start of the Viking Age is therefore set to the “dark date” of the attack, i.e. 8 June 793.

However, if the Vikings had got the opportunity to describe themselves, they probably would have said something like: “We come from the north and honor Odin, Thor, Freyr, and our ancestors. Feel free to call us heathens or Vikings, but we have always been, and always will be free men from the north”.

Furthermore, the Viking Age did not come to an end at the Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September 1066, a date determined by today’s historians and archaeologists.

But, this is quite a different story.

Top image: They came from the fjords of Western Norway, and when they left, only silence could be heard. (Illustrating photo from “Trace” Viking movie, by Markus Dahlslett).

The article ‘ Did the Viking Age Really Start on 8 June 793 AD? ’ by Thor Lanesskog was originally published on ThorNews and has been republished with permission.

Published on December 16, 2017 23:30

December 15, 2017

Star Wars: why did the film make history?

History Extra

This article was first published in December 2015

Peter Mayhew, Harrison Ford, Alec Guinness and Mark Hamill, on-set of the film Star Wars, 1977. (© Glasshouse Images/Alamy Stock Photo)

Professor Nicholas John Cull explores the history of the Star Wars franchise, and explains why in 1977 thousands of people flocked to cinemas to be taken to a galaxy far, far away…

There is a moment in the first Star Wars film when the mystic Obi Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness) detects across at great distance of space the destruction of a planet and remarks: “I felt a great disturbance in the Force… as if as if millions of voices suddenly cried out in terror and were suddenly silenced.”

The release of the seventh installment of the Star Wars saga today therefore prompts the question of exactly what the particular “disturbance in the Force” associated with the release of the first film in the series back in May 1977 might mean historically. What does it say about the time in which it was made and the people who so took it to their hearts? And what does the ongoing success of the franchise say about us?

At one level, Star Wars was – and is – a commercial commodity: a milestone in the evolution of the film industry. Its creator, George Lucas, demonstrated that films could be made for families; that spectacular effects could help film to claw back some territory from the small-screen entertainment; and profits could be swollen to astonishing proportions though tie-in merchandise.

Other films of the era attempted similar synergies, but there was plainly something about Star Wars that struck a particular chord. Reports of initial audiences in the US stressed how hungry they seemed for what Star Wars offered: the film was fundamentally not like so many other elements of the culture in which it landed – a world that was only too happy to embrace the film’s escapism because it had so much that it wished to escape from.

For the initial audiences in America and beyond, the experience of viewing Star Wars was a curious mixture of watching something completely new and something incredibly familiar. It was a paradox, illustrated in the film’s opening declaration that it was set “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away”.

The familiar components in the film were the incorporation of multiple elements of beloved genres that were out of step with the cynical post-Watergate, post-Vietnam War, energy crisis world of the mid-1970s. Star Wars’ abstract and distant location with absolutely no point of reference to humanity or earth culture enabled favourite tropes of the screen to be revisited without the necessity of apology or self-examination or of any danger of alienating a nationality or ethnic group at home or abroad.

Star Wars was the product of and for an American society yearning to be free of its own bonds of history and be good again. It was the perfect transferable product in which everyone could find themselves, not just within the US, but worldwide. It helped that the film’s heroic structure was borrowed from the myths common to all human cultures: Star Wars recovered the energy and zest of the old Flash Gordon serials; it borrowed characters and settings from the classic western, which by the 1970s was burdened in its explicit form by America’s awareness of the moral ugliness of the historical reality.

Star Wars’ location allowed much play and humour at the expense of ethnic and racial differences that would have been impossible (and tasteless) in the wake of the Civil Rights movement. Various characters seemed to fill the role of the ethnic ‘other’: the droids experience segregation in the bar scene, and Chewbacca is cast as a noble, ethnic side-kick, providing heroic support and comic relief.

Peter Mayhew as Chewbacca and Harrison Ford as Han Solo in Star Wars, 1977. (© Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo)

Two genres had particular significance within Star Wars: the war film and the religious epic. Star Wars enabled the representation of a war without having to worry about that war’s consequences; the merits of its antagonists; or that any participant might be offended. Much of it channelled the Second World War with Imperial uniforms and the terminology of Storm Troopers borrowed from the Third Reich; however, it was also swiftly noticed that in Star Wars a country that had just been defeated by an army of guerillas was able to happily identify with a rebel alliance. So, much of the film’s look could be borrowed from Asia, in particular the Vietnam War, without audiences having to recall who firebombed Tokyo or dropped Agent Orange on the Ho Chi Minh trail.

The elements of Star Wars lifted from religious epics functioned in much the same way: the film recovered a genre that had been an immense part of 20th-century cinema, reaching its apogee in the late fifties with wildly successful films like The Ten Commandments or Ben-Hur (its chariot race scene was the model for the pod-race in Episode I: The Phantom Menace). By creating its universe of right and wrong, and its religion of The Force, George Lucas was able to tell an essentially religious story of awakening, sacrifice, temptation and redemption, and it so doing he could touch his viewers’ sense of wonder and the infinite. The setting in space enabled maximum engagement with minimal alienation, and enabled visual wonders every bit as impressive as the parting of the Red Sea.

Overall, then, in 1977 Star Wars was a mechanism to culturally have your cake and eat it at a time of great uncertainty in America and the west. It allowed its viewer to luxuriate in the triumphalism, ethnic voyeurism and religiosity without apology.

Of course, it didn’t take long for people in America and many other parts of the world to outgrow the uncertainty of mid 1970s; to trade Jimmy Carter for Ronald Reagan or James Callaghan for Margaret Thatcher, and reconnect with the self-confidence that allowed triumphalism, ethnocentrism and religiosity to flourish openly.

It turned out that audiences weren’t too alienated anyway. The Rambo cycle had the political sensitivity of a sledgehammer and did well around the world. By the time the original trilogy was re-released in the late 1990s (with up-dated effects), the Second World War’s Allied victory was a cause for celebration again, and did not have to be evoked by proxy.

In the meantime, Star Wars itself had become a cultural reference point: Ronald Reagan could tap into its language when he called Russia an ‘evil empire’; Ted Kennedy did the same when he dubbed Reagan’s pet strategic defense initiative the ‘Star Wars program’; and the Oklahoma City bomber, Tim McVeigh, compared himself to Luke Skywalker destroying the Death Star. In the end, the cultural phenomenon struck back. Comments on the decline of democracy and evils of “with us or against us” language in the script for Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, were unmistakable barbs from the liberal Lucas aimed at the George W Bush administration.

Looking back, it is plain that in its nearly 40-year (and counting) career, the Star Wars franchise has evolved. The films still turn on a twin drive to escape and to remember, but the direction of the remembrance has changed. In the beginning, audiences were remembering a film culture that had become unfashionable or untenable. Today we watch Star Wars to remember Star Wars. Given that the need for both remembrance and escapism remains undiminished, the new films should do very well indeed.

Nicholas John Cull is Professor of Communication at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School. He is the author (with James Chapman) of Projecting Tomorrow: Science Fiction and Popular Cinema (I B Tauris, 2012) which includes an extended discussion of the making and reception of Star Wars.

This article was first published in December 2015

Peter Mayhew, Harrison Ford, Alec Guinness and Mark Hamill, on-set of the film Star Wars, 1977. (© Glasshouse Images/Alamy Stock Photo)

Professor Nicholas John Cull explores the history of the Star Wars franchise, and explains why in 1977 thousands of people flocked to cinemas to be taken to a galaxy far, far away…

There is a moment in the first Star Wars film when the mystic Obi Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness) detects across at great distance of space the destruction of a planet and remarks: “I felt a great disturbance in the Force… as if as if millions of voices suddenly cried out in terror and were suddenly silenced.”

The release of the seventh installment of the Star Wars saga today therefore prompts the question of exactly what the particular “disturbance in the Force” associated with the release of the first film in the series back in May 1977 might mean historically. What does it say about the time in which it was made and the people who so took it to their hearts? And what does the ongoing success of the franchise say about us?

At one level, Star Wars was – and is – a commercial commodity: a milestone in the evolution of the film industry. Its creator, George Lucas, demonstrated that films could be made for families; that spectacular effects could help film to claw back some territory from the small-screen entertainment; and profits could be swollen to astonishing proportions though tie-in merchandise.

Other films of the era attempted similar synergies, but there was plainly something about Star Wars that struck a particular chord. Reports of initial audiences in the US stressed how hungry they seemed for what Star Wars offered: the film was fundamentally not like so many other elements of the culture in which it landed – a world that was only too happy to embrace the film’s escapism because it had so much that it wished to escape from.

For the initial audiences in America and beyond, the experience of viewing Star Wars was a curious mixture of watching something completely new and something incredibly familiar. It was a paradox, illustrated in the film’s opening declaration that it was set “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away”.

The familiar components in the film were the incorporation of multiple elements of beloved genres that were out of step with the cynical post-Watergate, post-Vietnam War, energy crisis world of the mid-1970s. Star Wars’ abstract and distant location with absolutely no point of reference to humanity or earth culture enabled favourite tropes of the screen to be revisited without the necessity of apology or self-examination or of any danger of alienating a nationality or ethnic group at home or abroad.

Star Wars was the product of and for an American society yearning to be free of its own bonds of history and be good again. It was the perfect transferable product in which everyone could find themselves, not just within the US, but worldwide. It helped that the film’s heroic structure was borrowed from the myths common to all human cultures: Star Wars recovered the energy and zest of the old Flash Gordon serials; it borrowed characters and settings from the classic western, which by the 1970s was burdened in its explicit form by America’s awareness of the moral ugliness of the historical reality.

Star Wars’ location allowed much play and humour at the expense of ethnic and racial differences that would have been impossible (and tasteless) in the wake of the Civil Rights movement. Various characters seemed to fill the role of the ethnic ‘other’: the droids experience segregation in the bar scene, and Chewbacca is cast as a noble, ethnic side-kick, providing heroic support and comic relief.

Peter Mayhew as Chewbacca and Harrison Ford as Han Solo in Star Wars, 1977. (© Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo)

Two genres had particular significance within Star Wars: the war film and the religious epic. Star Wars enabled the representation of a war without having to worry about that war’s consequences; the merits of its antagonists; or that any participant might be offended. Much of it channelled the Second World War with Imperial uniforms and the terminology of Storm Troopers borrowed from the Third Reich; however, it was also swiftly noticed that in Star Wars a country that had just been defeated by an army of guerillas was able to happily identify with a rebel alliance. So, much of the film’s look could be borrowed from Asia, in particular the Vietnam War, without audiences having to recall who firebombed Tokyo or dropped Agent Orange on the Ho Chi Minh trail.

The elements of Star Wars lifted from religious epics functioned in much the same way: the film recovered a genre that had been an immense part of 20th-century cinema, reaching its apogee in the late fifties with wildly successful films like The Ten Commandments or Ben-Hur (its chariot race scene was the model for the pod-race in Episode I: The Phantom Menace). By creating its universe of right and wrong, and its religion of The Force, George Lucas was able to tell an essentially religious story of awakening, sacrifice, temptation and redemption, and it so doing he could touch his viewers’ sense of wonder and the infinite. The setting in space enabled maximum engagement with minimal alienation, and enabled visual wonders every bit as impressive as the parting of the Red Sea.

Overall, then, in 1977 Star Wars was a mechanism to culturally have your cake and eat it at a time of great uncertainty in America and the west. It allowed its viewer to luxuriate in the triumphalism, ethnic voyeurism and religiosity without apology.

Of course, it didn’t take long for people in America and many other parts of the world to outgrow the uncertainty of mid 1970s; to trade Jimmy Carter for Ronald Reagan or James Callaghan for Margaret Thatcher, and reconnect with the self-confidence that allowed triumphalism, ethnocentrism and religiosity to flourish openly.

It turned out that audiences weren’t too alienated anyway. The Rambo cycle had the political sensitivity of a sledgehammer and did well around the world. By the time the original trilogy was re-released in the late 1990s (with up-dated effects), the Second World War’s Allied victory was a cause for celebration again, and did not have to be evoked by proxy.

In the meantime, Star Wars itself had become a cultural reference point: Ronald Reagan could tap into its language when he called Russia an ‘evil empire’; Ted Kennedy did the same when he dubbed Reagan’s pet strategic defense initiative the ‘Star Wars program’; and the Oklahoma City bomber, Tim McVeigh, compared himself to Luke Skywalker destroying the Death Star. In the end, the cultural phenomenon struck back. Comments on the decline of democracy and evils of “with us or against us” language in the script for Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, were unmistakable barbs from the liberal Lucas aimed at the George W Bush administration.

Looking back, it is plain that in its nearly 40-year (and counting) career, the Star Wars franchise has evolved. The films still turn on a twin drive to escape and to remember, but the direction of the remembrance has changed. In the beginning, audiences were remembering a film culture that had become unfashionable or untenable. Today we watch Star Wars to remember Star Wars. Given that the need for both remembrance and escapism remains undiminished, the new films should do very well indeed.

Nicholas John Cull is Professor of Communication at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School. He is the author (with James Chapman) of Projecting Tomorrow: Science Fiction and Popular Cinema (I B Tauris, 2012) which includes an extended discussion of the making and reception of Star Wars.

Published on December 15, 2017 23:00

December 14, 2017

Puzzling Medieval Runes Found on Stone in Norway

Ancient Origins

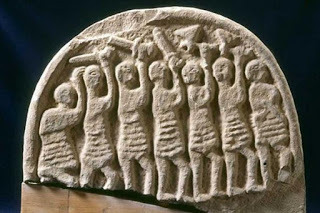

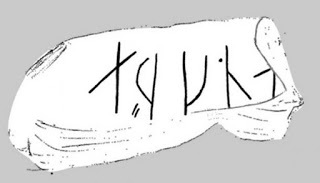

A rare find of a stone bearing engravings of runes that date back to the Middle Ages has been unearthed recently at an excavation near Oslo. The relic is a whetstone which was a tool used for sharpening knives. Oddly, this one has some symbols cut into it which have been recognized as being runic.

Medieval Symbols Are From Runic Writing

The whetstone, which was found during earthworks ahead of a railway-construction project in Oslo, Norway, is of polished slate and has been carved with ancient runes, reports LiveScience. It is only the second object of its type to be found anywhere in Norway, the other being found in Bergen on the west coast. Uncovering any items with runic inscriptions is a rare occurrence according to a statement by the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU), where the keen eyed archaeologist who picked out the special stone is based.

The spot where the runic whetstone appeared. Image: Khalil Olsen Holmen, NIKU.

It was recovered from an area of the excavation dating from between AD 1050-1500, a time when Vikings were still dominant in Norway, as LiveScience reports. The runic writing system was used widely in Europe by Germanic language speakers as early as AD 150 and even up to AD 1100, although throughout this time Europe was gradually adopting the Latin alphabet due to the spread of Christianity in the region. After this time use of runes continued but was limited to certain purposes.