MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 39

November 13, 2017

Who Were These Vikings Buried Sitting Upright?

Ancient Origins

BY THORNEWS

Accidentally, in 1963 a burial ground with 24 graves deep inside the bay of Sandvika on the eastern side of the island of Jøa in Central Norway were discovered. The bodies buried in a sitting position dates back to the years 650 to 1000 AD, and analyses show that these Vikings belonged to a very special group of people.

Unlike other Viking Age graves, the graveyard was unknown because the bodies were not placed inside a burial mound that is clearly visible in the terrain, or marked in any other way. These dead Vikings were lowered into cylinder- and funnel-shaped sand holes from flat ground. The question is why.

Sandvika Burial Ground is Unique

The Sandvika burial ground is unique in Scandinavia, and these people are the only ones found with sitting bodies.

The burial custom had been very strenuous: Firstly, the person must have been dead for at least twenty-four hours so that rigor mortis could make it possible to shape the body into a seated position, and secondly, it must have been very difficult to form seats in the porous shell sand.

However, these are not the only reasons why this particular group of Vikings is a mystery.

One of the skeletons found in the Sandvika sitting graves, Central Norway (Photo: NTNU Museum of Natural History and Archaeology, 1965-66)

Old Women – Small Men

In 14 of the 24 graves there were found skeletons and skeletal remains; 10 graves were empty.

Of these, seven women and four men have been identified. Analyses shows that the women reached an average age of 47 years, much higher than average for Iron Age people, where the normal life expectancy for women was 39 years.

It has only been possible to determine the age of one of the men, and he died at the age of 40.

The reconstructed Tranås Iron Age farm located only a few hundred meters from Sandvika. (Photo: ThorNews)

The women had an average height of 157.2 centimeters (5ft 2in), and the men 162.6 centimeters (5ft 4in), which is much lower than the normal height for this period.

The men were as much as 10 centimeters (3.9in) lower than the average for the Viking Age (172.6 cm / 5ft 8in) and 12 centimeters (4.7in) lower than people living in the Iron Age (174.7 cm / 5ft 9in).

The women do not differ so much – they only were 3.7 centimeters (1.5in) lower than the normal for Iron Age women (160.9 cm / 5ft 3in) and 0.9 centimeters (0.35in) lower than Danish Viking women (158.1 cm / 5ft 3in).

Heathen Hof Nearby

The dating of artifacts shows that these Vikings were buried fully clothed in the period 650 – 1000 AD, i.e. from the Merovingian period to the end of the Viking Age, and it seems like the burial custom ended when Christianity was forced with swords upon the Norse society.

Today, on the other side of the small river Hovselva (English: the Hof River) is the Hov (Hof) farm located in the northeast – indicating that there was a pagan temple located close to the burial ground.

In all of the 24 graves there were found remnants of bonfires, so it is natural to assume that there must have been some kind of ritual that included bonfire in connection with the funeral.

Orientation and Knives

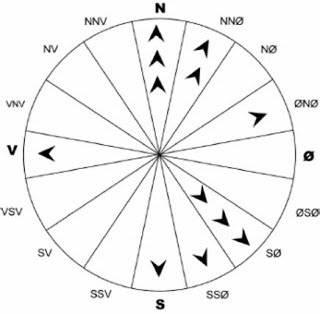

Another peculiarity is that about half the bodies were facing north-northeast (facing the Hof) and half to the south-southeast. No one was facing directly east and only one body was facing directly to the west.

An illustration showing the orientation of the bodies. Credit: Thor Lanesskog

As many as ten knifes were found in nine different graves. They vary in length, but none of them has a blade more than 20 centimeters and consequently had not been used as Viking combat weapons. The individuals they belonged to must have used these knives for a different purpose.

There were no other weapons found inside the graves, which is unusual for the Viking Age. However, there were also found beads, brooches, finger rings and keys, but there is no repeating pattern.

Specialists in Their Field

The similarities between the buried Vikings are many:

Both women and men died at an old age, and the men were much lower than the average height in the Viking Age.

They were buried in a small area close to a heathen Hof, and the dead were put down in a sitting position. There was no marking of the graves but they may have been marked with ornamental shrubs or flowers.

Almost all of the graves contained remnants of bonfire, and there are no traces of weapons. However, there were found many “regular” cut knives.

The bodies were facing north-northeast and south-southeast. No one was facing directly towards the east.

Who was this specialist group of Vikings? Was it “hovgydjer”, meaning pagan priestesses – and were the knives used for sacrifice? If so, the theory that Viking Age priests only were women is not correct.

Maybe Norse pagan priests also were small men with special “feminine qualities”?

Top image: Main image: Screen of Gameplay of the video game War of the Vikings (public domain). Inset: One of the skeletons found in the Sandvika sitting graves, Central Norway (Photo: NTNU Museum of Natural History and Archaeology, 1965-66)

The article ‘Who Were These Vikings Buried Sitting Upright?’ by Thor Lanesskog, was originally published on ThorNews and has been republished with permission.

Published on November 13, 2017 00:00

November 12, 2017

If King Alfred was great, was Æthelstan even greater?

History Extra

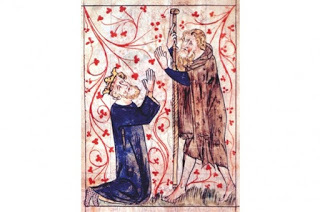

Æthelstan is shown dressed as a pilgrim with Guy of Warwick in a scene from the 14th-century 'Chronicle of England'. (Bridgeman)

Was King Alfred (reigned 871–99) really the greatest Anglo-Saxon king? Certainly he remains the best-remembered – even if it’s only for burning the cakes. But should it really be his grandson Æthelstan (reigned 924–39) – now largely forgotten – whom we celebrate as the most significant pre-Conquest monarch?

Alfred was a highly successful military leader who, in a battle at Edington in 878, resoundingly defeated the Danish army that had almost conquered Wessex. In the ensuing period of peace he launched a programme of educational reform that transformed the use of English as both a literary and a governmental language. Yet Alfred only ruled the West Saxon people, and those in the western part of the Midland kingdom of Mercia not under subjection to the Danes. When he died (the sole remaining native king in England), the east Midlands, East Anglia and Northumbria all lay in Danish hands.

Æthelstan, on the other hand, was the first king to rule all England and laid claim to an imperial overlordship over the whole of Britain. His military prowess brought him direct authority over not just Wessex and Mercia, but the Danelaw (the name given to the area of northern England where Vikings settled) and the kingdom north of the Humber. Celtic rulers from elsewhere in the British Isles subsequently submitted to his authority. He crushed a rebellion of the Scots king in 934, attacking his realm with a land and sea force and ravaging as far north as Caithness. When Æthelstan defeated a combined Norse-Scots-Northumbrian force at the battle of Brunanburh in 937, a contemporary poem entered into the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recalled: “Never yet in this island before this was a greater slaughter of a host made by the edge of the sword since the Angles and Saxons came hither from the east, overcame the Britons and won a country.”

The tomb of King Æthelstan in Malmesbury Abbey. (Alamy)

Foreigners also recognised Æthelstan’s status. He played a significant role on a European stage, forging alliances with royal and ducal houses across the territories of the former Carolingian empire through marriage and fostering arrangements. Scholars from Britain and abroad flocked to his court, bringing books, precious gifts and the relics of the saints (to which Æthelstan showed particular devotion). Alfred founded a dynasty. Æthelstan (who died childless) paved the way for that royal line (through his brothers and nephews) to govern all the English peoples via an effective administrative machine. When he died, an Irish chronicler lamented the demise of the “pillar of the dignity of the western world”. How can so great a king, once celebrated for his achievements, have fallen into such oblivion today?

Alfred’s posthumous reputation received a substantial boost from the profusion of literature that emanated from his court in the latter years of his reign – including the first version of the collection of year-by-year accounts of early English history we know as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

The statue of King Alfred the Great in Wantage, Oxfordshire. Alfred may widely be regarded as the father of the English nation, yet Æthelstan was the first to unite the English people under a single authority and proclaim himself "king of all Britain". (Alamy)

One of his circle, the Welsh priest Asser, also wrote a life of the king in the 890s, giving an unparalleled insight into his personality, his devotion to the saints, his practical and creative abilities and his attitudes to kingship. Texts translated from Latin into English at his court also included passages attributed to the king himself.

By contrast, the reign of Æthelstan is ill-served with narrative sources; the Chronicle offers the sketchiest narrative of events in his reign, there is no surviving biography, nor any writing attributed to his own authorship. Creating a picture of him as a man as well as a royal figurehead involves piecing together information from a disparate range of sources (and a good deal of imaginative licence).

Even so, after his death, Æthelstan enjoyed considerable fame. The West Saxon Latin chronicler Æthelweard saw Æthelstan as a mighty king and drew attention to his victory at Brunanburh (still remembered in the late tenth century as the ‘Great Battle’). Æthelstan’s submission of the Scots and the Picts brought significant and lasting consequences: “The fields of Britain were consolidated into one, there was peace everywhere and abundance of all things, and [since then] no fleet has remained here having advanced against these shores, except under treaty with the English.”

Æthelred the Unready (reigned 978–1016) called his eldest son Æthelstan – and worked through various Old English royal names before he thought to name his eighth son Alfred.

A king to remember

After the Conquest, Æthelstan’s reputation remained strong. To Anglo-Norman writers, he stood out as the founder of a united English realm, and – perhaps more significantly in that era – as having successfully asserted his authority over his Celtic neighbours. William, a monk of Malmesbury Abbey where Æthelstan was buried, paid him particular attention, providing insights not found in any other source, possibly drawing on a now-lost tenth-century life of the king. In William’s hands, Æthelstan became not just a king to remember but one about whom there were many stories, even popular songs worth recalling and repeating.

Various factors combined to diminish Æthelstan’s standing in the literary imagination during the late Middle Ages. Legends about a heroic British king, Arthur, received a substantial boost from the writing of Geoffrey of Monmouth. While Æthelstan’s martial success still gained approval, rumours first reported by William of Malmesbury that Æthelstan’s mother had been a concubine and he was therefore illegitimate gained increasing currency. The mysterious circumstances in which his younger brother, Edwin, was drowned at sea in 933 (supposedly in an open boat without an oar), and Æthelstan’s foundation of the church at Milton Abbas in reparation did him little good either. Æthelstan’s literary reputation reached its nadir in the 14th‑century poem, Æthelston, in which the eponymous hero comes across as a troubled and insecure king, struggling to achieve the moral authority to control his realm.

At the same time, other pre-Conquest kings achieved equal or greater prominence. Attempts to make a saint of Edward the Confessor began soon after his death; he was canonised in 1161. Most problematically for Æthelstan’s cause, Alfred was frequently hailed as the first king to have held sway over all England. Orderic Vitalis, writing in the 12th century, first made that claim, which was energetically promoted by monks at St Albans including Matthew Paris, who went so far as to say that “in view of his merits Alfred was called Great”. King Henry VI even tried in 1441 to get Alfred “the first monarch of the famous kingdom of England” canonised, but without success. No one tried to make a saint of Æthelstan, even though he never married and had such a great reputation for piety in his lifetime.

Æthelstan was overshadowed by the legend of King Arthur, shown in a c1250-80 vellum. (Bridgeman)

Neither great nor saint, Æthelstan’s place in the popular memory started to slide as the reputation of Alfred increasingly eclipsed that of all Anglo-Saxon kings. Elizabeth’s reign saw an increasing interest in the history of pre-Conquest England; antiquarians collected early English manuscripts and began to publish Anglo-Saxon texts, including Asser’s Life of Alfred. This helped to increase popular understanding of Alfred’s qualities as a ruler and build his reputation as a scholar and statesman at the expense not just of Æthelstan but of all other Anglo-Saxon kings for whom no equivalent biographies survive. William Tyndale had claimed that Æthelstan commissioned an early translation of the Bible. But it was Alfred’s promotion of English over Latin as the language through which to get closer to God that would resonate in the reformed English church, eager to find the historic roots of the Ecclesia Anglicana in the distant past.

Alfred’s reputation flourished further after the publication (in Latin in 1678, and in English in 1709) of John Spelman’s Life of King Alfred, which promoted the king as first founder of the English monarchy. Prince Frederick (son of George II) and his circle of patriots enthusiastically evoked Alfred for his protection of English freedoms and his defeat of foreign enemies, on land and sea. Thomas Arne’s masque Alfred, first performed for Prince Frederick in 1740, concludes famously with the anthem Rule Britannia.

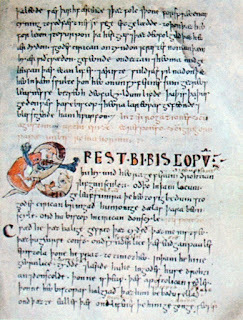

A tenth-century script of the Venerable Bede's 'History of the English People', which was translated during Alfred's reign. (Photoshot)

Thus, gradually during the 18th and 19th centuries, Æthelstan’s memory waned. Only the Freemasons remembered Æthelstan and celebrated him as their mythical founder in England, his ‘son’ (brother) Edwin the first English Grand Master. History books (especially those written for children) found much to celebrate in the deeds for which Alfred was famed, not just his victories over the Danes but his inventions – a candle-clock sheltering inside a horn lantern – and his supposed role in founding the English navy by having ships of a new, longer, design built to try and defeat the enemy at sea.

A national myth

Æthelstan’s right to be considered the first king of all England seemed long forgotten, that epithet given either to Alfred’s grandfather (Ecgberht, d839) or more often to Alfred. Anglo-Saxon topics were popular among Victorian painters but neither Æthelstan nor his great battle at Brunanburh found visual commemoration in any picture exhibited at the Royal Academy between 1769 and 1904; Alfred was however frequently depicted. It was Alfred who took the central role in the creation of a national myth of English and British origins; he became the archetypal symbol of the nation’s own sense of itself. The beginnings of political stability in Britain (which stood in marked contrast to the upheavals elsewhere in 19th‑century Europe) went back to Alfred’s day. As Edward Augustus Freeman argued, Alfred was the most perfect character in history; no other name could compare with his.

Nothing brings out the contrast between the two kings’ reputations better than the marking of the millennial anniversaries of their deaths. Thanks to uncertainty about the precise date of Alfred’s demise, his millennium was celebrated not in 1899 but in 1901. First planned in the aftermath of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee in 1897, the celebration was to be a “National commemoration of the king to whom this empire owes so much.”

Crowds travelled to Winchester on Friday 20 September to watch Lord Rosebery unveil Hamo Thornycroft’s massive statue of the king set in the Broadway, Winchester, before proceeding to Winchester Cathedral for a service with the massed choirs of southern English cathedrals, at which the archbishop of Canterbury preached.

Both sides of a silver coin of Æthelstan, which proclaims him as "Rex To Brit" ("King of All Britain"). (British Museum)

In stark contrast, a single notice in The Times of London for 25 October 1940 (buried under “Ecclesiastical News”), noted the supposed millennium of “Æthelstan the Great” (dating his death to 940, in error for 939). Lamenting that there might in happier times have been some celebration of this event, the correspondent remembered the king as the greatest and most munificent benefactor to St Paul’s Cathedral in London, his donations making that cathedral the richest in England.

Only with the revival of Anglo-Saxonism in the latter years of the 20th century, increased scholarly interest in the Latin and vernacular literature of England before the Conquest, and the critical editing of royal administrative documents, has Æthelstan begun to regain something of his former prominence. His reign lay at the source of many developments. First to unite the English peoples under a single authority, Æthelstan also accepted the submission of all the other rulers of Britain. Welsh kings attended regularly at his court, travelling round the kingdom with him.

Æthelstan expressed his claim to hegemony over all Britain in a new language of imperial rulership and in visual symbols, most obviously his decision to wear a crown (shown on his coins and in the surviving portrait of the king giving a book to St Cuthbert). His sway over the whole island brought together under one rule peoples that had previously suffered significant political disruption and consequent social breakdown because of the Danish wars and Scandinavian settlements.

Æthelstan created an efficient administrative machine to govern a dispersed realm, and directed much of his legal activity towards the repair and renewal of this fractured and damaged society.

“Very mighty”, “worthy of honour”, “his years filled with glory”, “pillar of the dignity of the western world”, “pious King Æthelstan”: each of these near-contemporary comments reflects aspects of Æthelstan’s achievement and personality. He deserves to be brought out of the shadows that have obscured his memory and celebrated as a key figure in the making of England – and, indeed, the forging of Britain.

Where Æthelstan is remembered

Æthelstan supposedly visited Beverley in the East Riding of Yorkshire on his way to fight a major battle in the north and paused to pray for victory at the shrine of St John of Beverley (a prominent figure in Bede’s History, and an early bishop of Hexham). On his return south, victorious, he refounded Beverley church as a collegiate community of canons and granted it land and a number of privileges including the right of sanctuary. Three monuments in the minster recall the king, including a life-size statue cast in lead in 1781 added to the screen at the entrance to the choir. Æthelstan stands holding a sword in one hand, and in the other the charter of privileges he had given to the town of Beverley. On the opposite side of the archway leading into the choir is a similar statue of Bishop John of Beverley.

Outside the guildhall at Kingston upon Thames in Surrey stands a piece of grey-wether sandstone, believed to be the Anglo-Saxon coronation stone on which Æthelstan was crowned in September 925. The stone once lay in St Mary’s chapel in the town; when that was destroyed, it was moved to the market place, where it served as a mounting block. The Masonic order of Surrey led a campaign in the 1850s to re-situate the relic in a more formal setting, arranging for it to be moved in 1854 to its current location, mounted on a heptagonal base and surrounded by railings. Re-laying the stone involved appropriate Masonic ceremonies, including the sprinkling of the monument with corn, oil and wine.

The coronation stone in Kingston upon Thames on which Æthelstan was crowned in September 925. (Alamy)

In the restored Norman abbey church at Malmesbury in Wiltshire, Æthelstan is commemorated by a late medieval tomb chest in perpendicular style, now in the north aisle.

The king’s recumbent, full-length effigy lies beneath a heavy traced canopy. The original head has been removed and replaced with another of unknown date. Æthelstan was a generous patron of Malmesbury in life and chose to be buried there, near the tomb of St Aldhelm. In the 12th century, William of Malmesbury saw the king’s remains and remarked on his fair hair. During the Reformation his bones were lost and the tomb is now empty.

St Cuthbert and the kings of Wessex

Both Alfred and Æthelstan are associated with legends relating to St Cuthbert (bishop of Lindisfarne, d687). At his time of greatest need, before the battle of Edington, King Alfred supposedly received a night-time visitation from the saint, who promised him victory and a glorious future for his sons. If Alfred would be faithful to Cuthbert and his people, Albion would be given to him and his sons, and he would be chosen king of all Britain. Æthelstan – who claimed that very title: king of all Britain – showed great devotion to the saint’s shrine on a visit to Chester-le-Street in 934. He gave many precious gifts including a book containing Bede’s life of Cuthbert. The frontispiece to that volume depicts a double portrait of the crowned King Æthelstan presenting the manuscript to Cuthbert.

Sarah Foot is Regius Professor of ecclesiastical history at Christ Church, Oxford and author of Æthelstan: The First King of England.

Published on November 12, 2017 00:30

November 11, 2017

Ancient Journeys: What was Travel Like for the Romans?

Ancient Origins

It was not uncommon for the ancient Romans to travel long distances all across Europe. Actually during the Roman Empire, Rome had an incredible road network which extended from northern England all the way to southern Egypt. At its peak, the Empire's stone paved road network reached 53,000 miles (85,000 kilometers)! Roman roads were very reliable, they were the most relied on roads in Europe for many centuries after the collapse of the Roman Empire. It could be argued that they were more reliable than our roads today considering how long they could last and how little maintenance they required.

A Roman street in Pompeii. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Travel by road

Unlike today, travel by road was quite slow and... exhausting! For example, going from Rome to Naples would take over six days in Roman times according to ORBIS, the Google Maps for the ancient world developed by Stanford University. By comparison, it takes about two hours and 20 minutes to drive from Rome to Naples today.

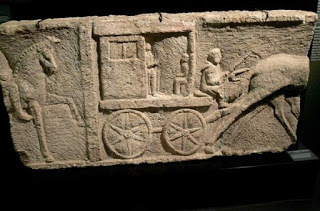

Funeral relief (2nd century ) depicting an Ancient Roman carriage. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Romans would travel in a raeda, a carriage with four noisy iron-shod wheels, many wooden benches inside for the passengers, a clothed top (or no top at all) and drawn by up to four horses or mules. The raeda was the equivalent of the bus today and Roman law limited the amount of luggage it could carry to 1,000 libra (or approximately 300 kilograms).

Rich Romans traveled in the carpentum which was the limousine of wealthy Romans. The carpentum was pulled by many horses, it had four wheels, a wooden arched rooftop, comfortable cushy seats, and even some form a suspension to make the ride more comfortable. Romans also had what would be the equivalent of our trucks today: the plaustrum. The plaustrum could carry heavy loads, it had a wooden board with four thick wheels and was drawn by two oxen. It was very slow and could travel only about 10-15 miles (approximately 15 to 25 kilometers) per day.

Carpentum replica at the Cologne Museum . ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

The fastest way to travel from Rome to Naples was by horse relay or the cursus publicus , which was like a state-run postal service and a service used to transport officials (such as magistrates or people from the military). A certificate issued by the emperor was required in order for the service to be used. A series of stations with fresh and rapid horses were built at short regular intervals (approximately eight miles or 12 kilometers) along the major road systems. Estimates of how fast one could travel using the cursus publicus vary. A study by A.M. Ramsey in "The speed of the Roman Imperial Post" (Journal of Roman Studies) estimates that a typical trip was made at a rate of 41 to 64 miles per day (66 - 103 kilometers per day). Therefore, the trip from Rome to Naples would take approximately two days using this service.

Because of their iron-shod wheels, Roman carriages made of a lot of noise. That's why they were forbidden from big Roman cities and their vicinity during the day. They were also quite uncomfortable due to their lack of suspension, making the ride from Rome to Naples quite bumpy. Fortunately, Roman roads had way stations called mansiones (meaning "staying places" in Latin) where ancient Romans could rest. Mansiones were the equivalent of our highway rest areas today. They sometimes had restaurants and pensions where Romans could drink, eat and sleep. They were built by the government at regular intervals usually 15 to 20 miles apart (around 25 to 30 kilometers). These mansiones were often badly frequented, with prostitutes and thieves roaming around. Major Roman roads also had tolls just like our modern highways. These tolls were often situated at bridges (just like today) or at city gates.

Travel by sea and river

Man sailing a corbita, a small coastal vessel with two masts. ( Public Domain )

There were no passenger ships or cruise ships in ancient Rome. But there were tourists. It was actually not uncommon for well-to-do Romans to travel just for the sake of traveling and visiting new places and friends. Romans had to board a merchant ship. They first had to find a ship, then get the captain's approval and negotiate a price with him. There were a large number of merchant ships traveling regular routes in the Mediterranean. Finding a ship traveling to a specific destination, for example in Greece or Egypt, at a specific time and date wasn't that difficult.

Ancient Roman river vessel carrying barrels, assumed to be wine, and people. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Romans would stay on the deck of the ship and sometimes there would be hundreds of people on the deck. They would bring their own supplies aboard including food, games, blankets, mattresses, or even tents to sleep in. Some merchant ships had cabins at the stern that could accommodate only the wealthiest Romans. It is worth noting that very wealthy Romans could own their own ships, just like very wealthy people own big yachts today. Interestingly, a Roman law forbade senators from owning ships able to carry more than 300 amphorae jars as these ships could also be used to trade goods.

How clay amphorae vessels may have been stacked on a galley. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Traveling by ship wasn't very slow, even compared to modern day standards. For example, going from Brindisium in Italy to Patrae in Greece would take over three days, versus about one day today. Romans could also travel from Italy to Egypt in just a few days. Commercial navigation was suspended during the four winter months in the Mediterranean. This was called the mare clausum . The sea was too rough and too dangerous for commercial ships to sail. Therefore, traveling by sea was close to impossible during the winter and Romans could only travel by road. There were also many navigable rivers that were used to transport merchandise and passengers, even during the winter months.

Traveling during the time of the ancient Romans was definitely not as comfortable as today. However, it was quite easy to travel thanks to Rome's developed road network with its system of way stations and regular ship lines in the Mediterranean. And Romans did travel quite a lot!

Featured image: An ancient Roman road at Leptis Magna, Libya.( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

By: Victor Labate

References

Romae Vitam. Roman roads.

Watler Scheidel, Elijah Meeks. ORBIS The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World. Orbis.Stanford.edu

Romae Vitam. Roman carriages.

Romae Vitam. Roman ships.

Published on November 11, 2017 00:00

November 9, 2017

Ælfthryth: England’s first queen

History Extra

Illustration by Sarah Young.

If asked to name a medieval queen of England, most would probably fasten upon Eleanor of Aquitaine, the influential wife of Henry II, made famous by Katharine Hepburn in The Lion in Winter. A few Plantagenet and Tudor enthusiasts might think of Elizabeth Woodville, the capable consort of Edward IV and grandmother to Henry VIII. One or two of the more adventurous might even fix upon Emma of Normandy, the indomitable wife of King Cnut in the early 11th century. Many would struggle to think of any at all. But very few indeed would name Ælfthryth, the third wife of King Edgar (reigned 959–75) and mother of Æthelred ‘the Unready’ (r978–1013 and 1014–16).

This is understandable. Beyond her outlandish name (sometimes modernised as Elfrida), Ælfthryth faces a number of difficulties. For a start, our sources for her life are much scarcer than they are for her more famous successors. To this may be added the lower public profile of Anglo-Saxon history.

All too often we think of the Middle Ages as starting in 1066. Before this lurks the mysterious ‘Dark Ages’: a period filled with fascinating, semi-mythical figures such as Arthur and Merlin, but little in the way of real historical evidence. Still, it is a pity that she is not better known, for if any medieval English queen deserves to be a household name, it is Ælfthryth. And for all the importance of an Eleanor or an Elizabeth, it is Ælfthryth who has the honour of being the ‘first queen of England’.

Ælfthryth’s reign came at a decisive time in English history. The second half of the ninth century had seen the Vikings subdue the north and east of England. Only the kingdom of Wessex, south of the Thames, survived – and this only thanks to the dogged efforts of Alfred the Great (r871–99). Under Alfred’s successors, the English went on the offensive, and by his grandson Æthelstan’s time (r924–39) most of what is now England had been brought under their control. Later kings had to fight hard to maintain these gains, but in the end they succeeded.

Ælfthryth herself was born in the early to mid-940s to a prominent family in the South West. Upon coming of age, she was married to Æthelwold, the ealdorman of East Anglia (a royal officer, the equivalent of the later ‘earl’). Æthelwold’s family was one of the most powerful in England (his father had borne the nickname ‘half-king’, on account of his quasi-regal standing) and in this capacity he was responsible for almost a quarter of the realm. However, Æthelwold soon died under circumstances that are unclear. But rather than a setback, this proved the making of the young Ælfthryth.

Rival spouses

In 964 Ælfthryth, still only in her late teens or early twenties, went on to marry King Edgar, who had himself succeeded to the throne five years earlier. Like Ælfthryth, Edgar had been married before. In fact, he had two prior spouses, one of whom was still alive. Not surprisingly, there were questions as to whether this was a true marriage ‘till death do us part’: an indissoluble union in the language of the church.

Such concerns were soon put to rest, however. On the occasion of the marriage itself, Edgar granted land to his new wife – a particular honour accorded to neither of his previous consorts. In fact, this seems to have been a different kind of union from the outset. Unlike her predecessors, Ælfthryth regularly appeared in government records. And, far from being there for purely decorative purposes, she seems to have influenced and guided royal policy.

Before this, royal wives had been minor players. They appear only rarely in the documentary record, and when they do, they invariably bear the title ‘king’s wife’ or ‘king’s consort’ rather than ‘queen’. Such terms emphasise the dependency of these women on their husband; queen was not yet an office in its own right. But this too was now to change. From the start, Ælfthryth is styled ‘queen’.

The rugged ruins of Corfe Castle, built on the estate where King Edward was murdered. (Alamy)

The reason for this change lies in another break with tradition: Ælfthryth was also the first consort of England to be crowned and consecrated. The tradition of royal consecration had developed on the continent in the early Middle Ages. At its heart lay the ritual anointing of the monarch with holy oil and investment with symbols of office (above all, the crown – hence the modern term ‘coronation’). The ceremony enacted and symbolised the transition from heir apparent to king, and was thought to endow the monarch with divine favour. It made him king ‘by the grace of God’.

Royal consecration had become common in England in the ninth century, but it was reserved for ruling monarchs, invariably men. That Ælfthryth should be formally anointed like her husband marks an important point of departure. It indicates that, in both practical and symbolic terms, queenship was starting to become an office. Ælfthryth’s influence would not be owed entirely to her husband, but also to ‘divine grace’.

The partnership between Ælfthryth and Edgar is visible throughout the remaining years of his reign. In the year of their marriage, they began to reform the bishopric of Winchester. This was a process that involved removing the existing clergy, who were accused of lax standards, and replacing them with monks. In future years, the two worked closely to foster similar reforms elsewhere. And when, in 973, Edgar decided to undergo a spectacular second coronation at Bath, Ælfthryth was right there by his side.

A succession struggle

In early July 975, at the height of his powers, Edgar died at the age of no more than 32. This had not been foreseen, and a succession struggle soon erupted. This pitted Ælfthryth and Edgar’s son, Æthelred, against Edgar’s eldest son, Edward (Æthelred’s half-brother).

Most surprising is that there was a dispute at all. Though succession rules had yet to be formalised, it was generally anticipated that the eldest son would succeed (at least in the absence of a royal brother). That some were willing to back the much younger son Æthelred, who may only have been six at the time, requires some explanation.

It’s likely that the imposing figure of Ælfthryth lay behind their decision. As queen, she had enjoyed great power and influence and was understandably hesitant to let go of this. Edward’s succession posed a real threat to her. If Edward proved long-lived, there was every chance that Æthelred might be cut out of the succession. Yet Ælfthryth was not just power-hungry. As a consecrated queen, she may have felt that she was more legitimate than Edgar’s previous wives: his only true consort. And if this were so, then Æthelred was his only true offspring.

It was this that seems to have been the real point of contention: was Edward a throne-worthy heir, or an illegitimate bastard? Some were clearly convinced of the latter, but in the end age trumped legitimacy and Edward was consecrated king in his father’s stead.

Edward’s succession was a major blow to Ælfthryth, and such wounds were not easily healed. Barely had Edward taken control of the realm, when he was killed at Corfe in Dorset by supporters of Æthelred and Ælfthryth. He had been travelling to visit the two at the time, and it is hardly surprising that suspicion has often fallen upon them. However, contemporary sources, of which there is little shortage, do not implicate them. We are probably dealing with a situation rather like that of Henry II and Thomas Becket two centuries later: one of zealous supporters seeking to do their masters a favour, and going beyond their orders.

A scene depicting Ælfthryth looking on while King Edward (on horseback) is stabbed to death. Ælfthryth benefitted from the murder - but did she order it? (Bridgeman)

Whatever the precise circumstances, this act landed Æthelred on the throne that his mother had worked so hard to secure for him. However, he was still a child (no older than 12, and perhaps only eight or nine) so there could be no question of him ruling on his own. Instead, an informal regency was established with Ælfthryth and her supporters at its head. For the next six years, it was they who would rule with quiet efficiency. Only when the queen regent’s chief allies, Ælfhere of Mercia and Bishop Æthelwold of Winchester, died in quick succession in 983 and 984, did Æthelred finally take control of affairs. Initially, he distanced himself from the politics of his regents, and for the next eight or nine years Ælfthryth disappears from the record entirely. She was clearly removed from court, and her policies with her.

Crisis of confidence

These years saw something of a youthful rebellion from the teenage Æthelred, who took the opportunity to promote new favourites and attack religious houses associated with his earlier regents. Yet it was also at this juncture that the Vikings began to plague his coasts. In 991 they defeated a major English force at Maldon in Essex. Æthelred suddenly suffered a crisis of confidence.

As was common in the Middle Ages, the king interpreted this as a sign of divine displeasure, and set about mending his errant ways – starting with restoring his mother to favour. He welcomed Ælfthryth back at court and reversed previous policies. Æthelred also charged his mother with the important task of raising his children (her own grandchildren, the heirs to the throne). Reconciliation seems to have been complete.

When Ælfthryth died on 17 November 1001, the king was deeply moved. She was buried at Wherwell, the nunnery she had founded in Hampshire. Soon after Æthelred issued an extraordinary document in favour of this centre. Like most royal enactments, the resulting text opens with a meditation on God’s will. Yet unlike other documents of the era, this quotes the biblical dictum: “Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return,” then cites the fifth commandment: “Honour thy father and thy mother”.

Ælfthryth’s legacy lived on in the queens who followed her. Æthelred’s second wife, Emma of Normandy, cut quite the figure in future years, as did Edith, the wife of Edward the Confessor (and the sister of Harold Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England). The office of queen had been born, and had a long and bright history before it.

Ælfthryth’s inspiration

Two women who set the template for the queen’s achievements

In the years before Ælfthryth, the status of royal women varied significantly. The dynasty that united England in the early 10th century was that of Wessex (south of the Thames), and prevailing attitudes were drawn from there. At the time of Alfred the Great, the king’s Welsh biographer, Bishop Asser, criticised the “strange” West Saxon tradition of denying royal consorts the title of queen – a custom that reportedly went back to the king Beorhtric in the early ninth century (r786–802), whose wife accidentally poisoned him! This is the stuff of legend, but whatever the real grounds, West Saxon royal women – aside from Judith, crowned queen of the West Saxons in 856 – did not have a high profile.

Ælfthryth, shown in a manuscript from Abingdon Abbey. (Bridgeman)

Elsewhere, matters were different. In the Midlands kingdom of Mercia, royal wives traditionally held a more active role. It is here that the most famous female figure of the 10th century is to be found: Æthelflæd, ‘lady of the Mercians’.

Æthelflæd was the eldest daughter of Alfred the Great. She married the Mercian nobleman Æthelred, who oversaw the region on Alfred’s behalf. When her husband died in 911, she took power, working with her brother, King Edward the Elder (r899–924), to conquer much of the east Midlands and East Anglia. Her political links to Wessex doubtless helped her position, but her achievement is no less impressive for this. She may have offered a model for Ælfthryth, whose first husband hailed from East Anglia.

Another likely inspiration was Eadgifu, wife of Edward the Elder. Little is known about Eadgifu during her husband’s reign, but when her sons Edmund (r939–46) and Eadred (r946–55) ruled, she seems to have been the power behind the throne.

Levi Roach is a lecturer in history at the University of Exeter and author of Æthelred the Unready (Yale University Press, 2016)

Published on November 09, 2017 23:30

November 8, 2017

The deadly inheritance of Lady Jane Grey: 60 seconds with Nicola Tallis

History Extra

Ahead of her talk, ‘Crown of Blood: The Deadly Inheritance of Lady Jane Grey’, we caught up with Nicola to find out more…

Q: What can audiences look forward to in your talk?

A: A bit of everything! The great thing about the story of Lady Jane Grey is that it contains all of the elements that make the Tudor period so fascinating: drama, intrigue, ambition – all of which sadly culminate in disaster and tragedy.

Lady Jane Grey, who was married to Lord Guildford Dudley as part of her father's plot to gain the crown, was arrested on the orders of Queen Mary I in 1553 and later executed by beheading at the Tower of London. (Kean Collection/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Q: Why are you so fascinated by this topic?

A: Before I started working on Lady Jane Grey, I thought that there wasn’t much more that I could possibly add – I thought that everything had already been said. It came as a complete surprise when I went back to the original sources and discovered that actually there was so much material that hadn’t been incorporated into Jane’s story. The Jane that I discovered was very different from the one that had been portrayed for many centuries, and it was fascinating delving deeper into how this portrait of her emerged. Comparing this with the material I found was riveting.

Q: Tell us something that might surprise or shock us about this area of history.

A: Lady Jane Grey is actually the only Tudor monarch for whom there are no portraits or authenticated likenesses, so aside from the few descriptions of her we have no real idea of what she looked like.

A 19th-century painting of the execution of Lady Jane Grey, which took place in the Tower of London in 1554. (VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images)

Q: If you could go back in time to witness one moment in history, what would you choose and why?

A: I’d love to have witnessed a glimpse of Elizabeth I’s famous visit to Kenilworth Castle in 1575. Her host Robert Dudley put a great deal of time and money into arranging a whole array of lavish festivities for the queen’s entertainment, including masques, fireworks, hunting and banquets. It was such a dazzling spectacle that it became known as the ‘princely pleasures’, and I’m sure it would have been a wonderful sight to behold!

Q: What historical mystery would you most like to solve?

A: It may be quite an obvious choice, but like many people I’m dying to know the truth about the Princes in the Tower!

Q: What job do you think you would be doing now if you weren’t a historian/author?

A: I used to be a beauty therapist but I hated it, so definitely not that! I adore animals, so I’d like to think I’d be doing something that encompassed that – perhaps a wildlife rehabilitator.

Nicola Tallis is a historian, researcher and author. Her debut book, Crown of Blood: The Deadly Inheritance of Lady Jane Grey, was published in 2016.

Published on November 08, 2017 23:30

November 7, 2017

The great Viking terror: how Norse warriors conquered the Anglo-Saxons

History Extra

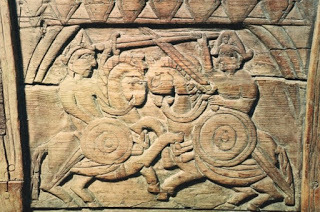

This detail from the side of a sledge in a ninth-century Viking burial shows two men fighting. In the 860s and 870s, the Vikings would bring war to England’s four kingdoms on a massive scale. (Bridgeman)

During the winter of AD 873–74, a Viking warrior met a gruesome death, probably in an attack on a Mercian royal shrine at Repton. He was a big man, almost 6 feet tall, and at least 35–45 years old. But in the shieldwall his head was vulnerable. He suffered a massive blow to the skull and, as he reeled from that, the point of a sword found the weak spot in his helmet – the eye slit in the visor, gouging out his eye, and penetrating the back of the eye socket, into his brain. While he lay on the ground, a second sword blow sliced into his upper thigh, between his legs, cutting into his femur and probably slicing away his genitals.

After the battle, the slain Viking warrior’s comrades buried him next to the Mercian shrine in what is now the parish church of St Wystan, where he lay for over a thousand years – until excavated by archaeologists.

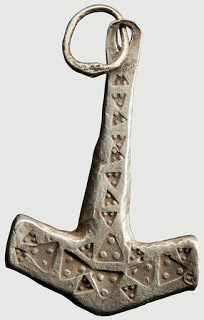

The man in Grave 511 was buried with his head to the west, his hands together on his pelvis. He wore a necklace of two glass beads and an amulet in the shape of a Thor’s hammer. Around his waist was a belt, from which had probably been suspended a key and two knives – one of a folding-type, like a modern Swiss-army penknife.

The other warriors had placed his sword back in its wooden fleece-lined scabbard, and laid it by his left side, where it had doubtless hung in life. They also carefully put the tusk of a wild boar between his thighs, to replace what he had lost in battle; he had died a warrior’s death, and was destined for the pleasures of Valhalla. More mysteriously, they rested the wing bone of a jackdaw lower down, between his legs.

A younger man, perhaps the warrior’s shield-bearer, was buried adjacent to him in order to accompany him to the next world.

Finally, the burial party built a stone cairn over the graves, incorporating fragments of an Anglo-Saxon cross that they had deliberately smashed. They also erected a wooden marker between the graves so that all would know who lay there. There the burials remained undisturbed, and perhaps still visible, for generations.

A coin depicting King Alfred, who defeated Guthrum’s marauding army. (Bridgeman)

Game-changing tactic

Taken in isolation, these Viking graves tell us little about ninth-century England – they are merely the grisly results of one bloody incident in a period characterised by violence. Yet viewed alongside a succinct reference to the events that led to the Vikings’ deaths in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, they soon become something more powerful altogether – a rare insight into the arrival on these shores of a force that would change Anglo-Saxon England for ever, the Viking Great Army.

“In this year,” the Chronicle declares, “the army went from Lindsey to Repton and took up winter quarters (wintersetl) there, and drove King Burgred across the sea… And they conquered all that land… And the same year they gave the kingdom of the Mercians to be held by Ceolwulf, a foolish king’s thegn; and he swore oaths to them and gave hostages.”

The excerpt is full of references to this game-changing development. We know that King Burgred fled to Rome after his kingdom was attacked by marauding Vikings. And we believe that Ceolwulf was a puppet king, put on the Mercian throne by the Vikings for the very good reason that he would do what he was told.

Yet it is the use of “army” and “winter quarters” that make this particular Viking attack stand out from all that had gone before. This was no small band of raiders launching a lightning strike on an unsuspecting population before disappearing with its loot back to Scandinavia. No, this was a mighty military force made up of hundreds, if not thousands, of warriors, and the fact that it decided to bed down on what is now the grounds and cloisters of Repton school, suggests that it was here to stay.

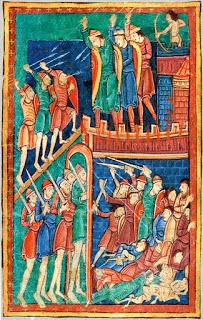

Women and children flee as Vikings launch an attack, in a medieval illustration. (Alamy)

Rival powers

In the mid-ninth century, England was not a single kingdom. Instead it was made up of four rival powers: East Anglia, Wessex (in the south and west), Mercia (including London and the Midlands), and Northumbria, to the north. Anglo-Saxon England was mainly rural and its wealth was derived largely from the wool trade. There were a few trading sites, or wics, that we might call towns. These include Ipswich, Eoforwic (York), Hamwic (Southampton) and Aldwych (the Anglo-Saxon trading port of London, now the Strand). But the majority of the population lived in dispersed rural settlements, as part of large estates owned by the king or the church.

Although capable of great works of manuscript and metalwork art, England was not industrialised. There were some imports, including German wine and lava millstones, but most everyday items were made locally. Most pottery, for example, comprised crude handmade and low-fired wares for local consumption. However, the Anglo-Saxon kings were Christians, and their rich monasteries – often placed in vulnerable coastal locations such as Lindisfarne, Monkwearmouth, and Jarrow – had been targeted by Viking raiding parties from the end of the eighth century.

Initially these were hit-and-run affairs, focused on portable wealth – church silver and slaves – and the forces involved were fairly small. The Vikings hailed from across present-day Scandinavia, and their slender longships – swift and shallow – allowed them to cross the North Sea and sail upriver to attack the heartland of England.

Occasionally the Vikings overwintered in England – on the Isle of Thanet in 850, and the Isle of Sheppey in 855. However, the so-called ‘Great Army’ that landed in East Anglia in 865 – the one that put Burgred to flight and over-wintered in Repton – was of a different magnitude, and had a different strategy. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that it had previously been campaigning in continental Europe but Charles the Bald, Holy Roman Emperor, strengthened Frankish defences and established a mobile cavalry force. The Viking leaders therefore appear to have decided that England, divided by internecine warfare, would provide easier pickings.

They were right. Soon after landing in East Anglia, the Viking Great Army took horses and travelled north, seizing York in 866. Next it swept south to Nottingham in 867, before returning to York the year after. Over the following three years it would attack Thetford (869), Reading (870) and London (871).

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says little of this period beyond recording where the army took wintersetl. Yet there can be little doubt that this was a crucial decade for English history. It witnessed the transformation of the Great Army from raiders to settlers, hastening the demise of the separate kingdoms of Mercia, East Anglia and Northumbria. In 876, one Viking force “shared out the land of the Northumbrians, and they proceeded to plough and support themselves”.

An amulet in the shape of Thor’s hammer – similar to this one – was found in the grave of a Viking leader killed at Repton in 873–74. (Alamy)

Hunger, cold and fear

The remainder of the Great Army, led by Guthrum, continued its campaigns, dividing out Mercia, and seizing the West Saxon royal estate at Chippenham in 877. Then it was suddenly stopped in its tracks by King Alfred of Wessex. Alfred had initially retreated into the marshes of Somerset to avoid capture but it wasn’t long before he was launching a counterattack: constructing a fortress at Athelney, rallying the men of Wessex to arms, and in 878 defeating the Vikings at Edington in Wiltshire. Alfred’s biographer, Asser, records that: “After 14 days the Vikings, thoroughly terrified by hunger, cold and fear, and in the end by despair, sought peace.”

As part of the ensuing negotiations Guthrum accepted Christianity, and “three weeks later Guthrum… with 30 of the best men from his army, came to King Alfred… and Alfred raised him from the holy font of baptism, receiving him as his adoptive son”. In 880 Guthrum’s army went to East Anglia “and settled there and shared out the land”.

Soon after, Guthrum and Alfred formally divided out their areas of jurisdiction, and made arrangements for relations between their followers over legal disputes, trade and the movement of people. Guthrum minted coins in his realm, some of which were copies of those of King Alfred, while on others he used his baptismal English name of Æthelstan. These initiatives were part of the process by which Guthrum became a Christian king in England.

Of the Great Army that precipitated these changes, we know little. Although we are given the names of the places where they over-wintered, the camps themselves remained elusive – until, that is, the archaeological work described in this article.

On the European mainland, Viking armies are known to have based themselves on islands in major rivers. A late ninth-century account by Abbot Adrevaldus of Flavigny Abbey in France of a Viking army on an island in the Loire hints at the advantages that this conferred. The Vikings, we are told, “held crowds of prisoners in chains and… rested themselves after their toil so that they might be ready for warfare. From that place they undertook unexpected raids, sometimes in ships, sometimes on horseback, and they destroyed all the province.”

Other sources suggest that the Vikings were trading as well as raiding. For example, the Annals of St Bertin record that in 873 a Viking army besieged by Frankish forces at Angers was permitted to hold a market on an island in the Loire before departing in February. That armies were associated with trading is reinforced by the entry in the Annals for 876, which describes the “traders and shield-sellers” that followed the army of Charles the Bald. We also know that Viking armies were accompanied by women. A late ninth-century account by Abbo, a monk of St-Germain-des-Prés, refers to the presence of women alongside the Viking force that besieged Paris in 885 and 886. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that a few years later a Viking army “placed their women in safety in East Anglia”.

Nine-foot giant

Archaeological investigation has revealed more still about the Viking Great Army. Excavations of a mound in the vicar’s garden at Repton revealed the disarticulated remains of at least 264 people, of whom 80 per cent were robust males. They had been placed within the stone foundations of a Mercian mortuary chapel, and covered with a stone cairn. The deposit had been disturbed in the 17th century, when most of the stone walls were robbed, and Thomas Walker, a labourer, described to Simon Degge of Derby how the bones had originally been laid out around a central stone coffin, in which the remains of a “nine-foot giant” had been discovered. Exaggeration aside, this has been suggested as the grave of another Viking leader, surrounded by the mass grave of bodies reinterred from the battlefield.

It is also important to consider the landscape around the camp at Repton. Some 2.5 miles to the south-east, and overlying the flood plain of the Trent, archaeology has revealed the only known Viking cremation cemetery in the British Isles – in Heath Wood. Here, there are over 60 burial mounds in four groups, perhaps reflecting different warbands, and a different burial strategy. Excavation has revealed that some of the mounds were erected directly over cremation pyres. The hearths had been swept clean, but fragments of swords and shields remained, as well as the cremated bones of sacrificed horses and dogs, required for hunting in Valhalla.

The graves contained women and children as well as men. But, unlike the warrior in Grave 511, who may have been hedging his bets by being buried adjacent to the location of saintly relics and holy pilgrimage, these Vikings seem to have had no such reservations about their faith.

Trail of destruction: our map shows how the Viking Great Army traversed England from AD 865–78.

The kingdoms’ demise

The term ‘Great Army’ suggests that the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were being assailed by one massive, unified force. However, documentary and archaeological evidence reveals that the army comprised multiple warbands drawn from different parts of Scandinavia. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’s account of the Vikings’ battles with West Saxon forces in 871 records that the army was led by at least two kings – Halfdan and Bagsecg – and many jarls (chiefs), and it was reinforced later in this year by a “great summer army”. The contrasting burial strategies adopted at Repton and Heath Wood may reflect different factions within the Great Army, which divided into two after spending the winter at Repton.

While Guthrum continued to battle against Alfred in Wessex, Halfdan took part of the army to Northumbria and proceeded to settle. This process is witnessed archaeologically by another excavation at Cottam, in East Yorkshire. Here, an Anglo-Saxon farmstead was abandoned before being replaced, in the late ninth century, by what we now describe as an Anglo-Scandinavian farmstead, its occupants adopting a new hybrid cultural identity revealed by, among other things, the style of their jewellery.

This farmstead is just one example of the many ways in which the Viking Great Army transformed England. As well as changes in land ownership, its arrival precipitated the demise of the distinct English kingdoms and the emergence of Wessex, under Alfred, as a united Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It also witnessed the establishment and growth of towns, initially as defended burhs (fortified settlements) against the Vikings, many of which grew into major trading and manufacturing centres.

In the wake of the Great Army, the Anglo-Saxons established a town at Torksey in modern-day Lincolnshire. Torksey was home to a mint and at least four churches, yet it would would earn its fame as the centre of a major pottery industry. This settlement near the banks of the Trent became one of the engine rooms of what has been described as England’s first industrial revolution. And, as the wheel-thrown and industrial-scale kiln technologies that were employed here were unknown in Anglo-Saxon England, they can only have been imported by continental potters travelling in the ‘baggage train’ of the Great Army. In other words, without the Great Army, that first industrial revolution may have looked very different indeed.

After 865, England would never be the same. The Vikings were here to stay, and left their legacy on all aspects of English life.

Overwhelming force

The Viking Great Army’s winter camps were among the largest settlements in England, as Julian D Richards and Dawn Hadley discovered when they investigated a site at Torksey

The theory that the Viking Great Army was small – its size exaggerated by Anglo-Saxon scribes for propaganda purposes – has been well and truly exploded by the discovery of a Norse winter camp at Torksey.

Our investigations of the site nine miles north-west of Lincoln – occupied by the Viking army over the winter of AD 872–73 – have recovered a wealth of plunder. This includes 26 ingots of silver and gold, as well as 60 pieces of broken-up silver jewellery, known as hacksilver. The Torksey investigations also uncovered fragments of broken-up Anglo-Saxon jewellery, ready to be melted down for recasting. The Vikings were trading, as well as processing their plunder.

The site contained more than 120 fragments of Arabic silver coins, or dirhams (the largest collection of its kind in the British Isles), which arrived here from the Middle East, via Scandinavia.

The Viking winter camp at Torksey, as shown in the recent BBC One documentary Vikings Uncovered. Archaeological fieldwork has revealed that, over the winter of 872-73, its many residents were busy trading, repairing weapons and ships, and making jewellery. (© Compost Creative)

There are over 350 weights, as well as Anglo-Saxon silver and copper coins. It is the English and Arabic coins that enable us to date the camp so precisely to 872–73.

The Vikings, who did not use coinage in Scandinavia, operated a dual economy in England: sometimes they paid in money; at other times, by weight of silver. They were also forging coins on the camp, as well as making jewellery. Other objects found at Torksey include needles and tools – as the army repaired its ships, weapons and clothes – and gaming pieces. No doubt wives and mistresses inhabited the camp too.

But it is the extent of the camp that makes the discoveries significant. The camp would have been an island, created by the river Trent to the west, and low-lying marshes to the east. It extended over 55 hectares (more than 75 football pitches), far larger than the enclosure at the Vikings’ winter camp at Repton.

The force that over-wintered at Torksey in 872–73 numbered in the thousands, not hundreds, and was larger than the population of most Anglo-Saxon towns.

Julian D Richards is professor of archaeology at the University of York and author of The Vikings: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2005). Dawn Hadley is professor of medieval archaeology at the University of Sheffield and is the author of Everyday Life in Viking-Age Towns (Oxbow, 2013). Together they are co-directing the Viking Torksey project.

Published on November 07, 2017 23:30

Game of Queens: when women ruled Renaissance Europe

History Extra

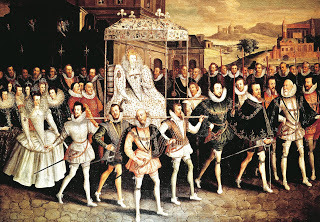

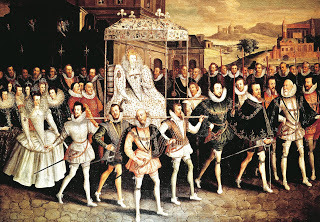

Isabella I of Castille, Anne de Beaujeu and Catherine of Aragon were three of the queens linked by a complex web of mothers, daughters, mentors and proteges. (Getty Images)

After her accession ceremony on 13 December 1474, Isabella of Castile rode through the streets of Segovia – behind a horseman holding a naked sword. Even her husband, Ferdinand of Aragon, was shocked, protesting that he had never before heard of a queen “who usurped this masculine attribute”. But Isabella’s reign ushered in an explosion of female rule, unequalled until our own day. In the 16th century, England, Scotland, France, the Netherlands, Spain, Portugal and Hungary all came at one time or another to be controlled by a woman, whether as regent or queen regnant.

These rulers were linked by a complex web of mothers and daughters, mentors and proteges. Lessons were passed from Isabella of Castile to her daughter Catherine of Aragon and thence Mary I, and from the French regent Anne de Beaujeu to Louise of Savoy, through Louise’s daughter Marguerite of Navarre to her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, to Marguerite’s admirer Anne Boleyn and thus to Elizabeth I.

Their experiences are echoed today. Headlines about Angela Merkel, Theresa May, Nicola Sturgeon and Hillary Clinton emphasise a powerful woman’s looks and likeability; the problem of gendered abuse, of seeming tough enough for high office without being dubbed unfeminine; the question of whether female leaders will relate to each other, and exercise their power, in a specifically female way.

The age of queens did not outlast the 16th century. Women had found themselves at the forefront of the great religious divides that tore Europe apart, but those divisions meant that, though Anne Boleyn could be educated in two foreign countries, her daughter Elizabeth never set foot out of her own land. We introduce 10 key female figures who dominated 16th-century Europe, and explore the relationships that linked them.

Isabella I of Castile (1451–1504)

Before she even took the throne, Isabella broke with tradition by arranging her own marriage to Ferdinand of Aragon, uniting the two main Spanish kingdoms. They ruled together as the mighty Catholic Monarchs, famous for their expulsion of the Moors and Jews, for establishing the Inquisition in Spain, and for their sponsorship of Christopher Columbus. Ferdinand and Isabella produced only one short-lived son but several influential daughters – among them Catherine of Aragon who in 1509 married England’s king Henry VIII.

Catherine of Aragon (1485–1536)

Catherine was defined by Spanish heritage. Henry VII of England sought the valuable Spanish alliance by wedding her to his eldest son, Arthur; after Arthur’s early death she married his younger brother, Henry VIII. As regent in 1513, “in imitation of her mother Isabella”, she rallied English troops to resist a Scottish assault. But as daughter to a successful queen regnant she was poorly placed to understand her husband’s obsessive desire for a son. When her marriage was rent by Henry’s infatuation with her former protege Anne Boleyn, Catherine still, after almost 30 years in England, described herself as a stranger in the land, appealing for help to her former sister-in-law Margaret of Austria.

Margaret of Austria (1480–1530)

The child of Mary of Burgundy (ruling duchess of what would later be known as the Netherlands) and future Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian, Margaret was, while still a toddler, contracted to the French king-to-be Charles VIII. When that alliance fell through she married Juan, heir of Isabella and Ferdinand, and then, after his early death, the Duke of Savoy. After he died she returned to the Netherlands where for many years she ruled as regent on behalf of her nephew, the future emperor Charles V. She raised four of his sisters, all of whom became queens consort – of France, Portugal, Denmark and Hungary. Mary of Hungary succeeded her aunt as regent of the Netherlands and raised another generation of influential nieces. Though Margaret of Austria never bore a living child, she has been called the Grand Mère – ‘Great Mother’ – of Europe.

Anne de Beaujeu. (Getty Images)

Anne de Beaujeu (aka Anne of France, 1461–1522)

Eldest daughter of the French king Louis XI, Anne was widely noted as a woman of great ability. The Salic Law, however, prohibited her from acceding to the throne. Instead, on Louis’ death she acted as regent in all but name during the minority of her younger brother Charles VIII. Anne wrote an advice manual for noblewomen, Enseignements [Lessons for my Daughter] that has been compared to Machiavelli’s The Prince. “When it comes to the government of their lands and affairs, [widows] must depend only on themselves; when it comes to sovereignty, they must not cede power to anyone,” was one of her maxims. Anne was in charge of the upbringings of Margaret of Austria during her marriage to Charles VIII, and of Louise of Savoy.

Louise of Savoy (1476–1531)

Louise’s status rose steadily as several French kings in succession died without heir until the closest in line to the throne was François, her son by the Count d’Angoulême. After François I became king in 1515, Louise was widely regarded as the power behind his throne. In 1529 she sat down with Margaret of Austria (her childhood playmate when they were both raised in Anne de Beaujeu’s care) to negotiate the so-called ‘Ladies’ Peace’ of Cambrai. Neither Louise’s son François nor Margaret’s nephew Charles could compromise their dignity by being the first to talk of reconciliation but, Margaret wrote: “How easy for ladies… to concur in some endeavours for warding off the general ruin of Christendom, and to make the first advance in such an undertaking!”

Marguerite of Navarre (aka Marguerite d’Angoulême, 1492–1549)

Louise of Savoy’s daughter Marguerite was also in Cambrai when the ‘Ladies’ Peace’ was negotiated. Louise, François and Marguerite were so close that they were known as ‘the trinity’; neither of Marguerite’s two marriages (to the Duc d’Alençon and to Henri II of Navarre) impeded her devotion to her brother, nor her sway over his court. Author of the book of short stories known as the Heptaméron, Marguerite was an intellectual leader among the great ladies who sought to reform the Catholic church. The number of ideas, books and contacts they had in common suggests that Marguerite became a role model for Anne Boleyn during the latter’s years in France. Anne would later send word to Marguerite that her “greatest wish, next to having a son, was to see you again”.

Anne Boleyn (c1501–36)

In 1513 Anne came to the court of Margaret of Austria as one of her maids, before spending seven years at the French court. This continental education gave her a glamour that made her a star when she returned to England. But it also gave her the opportunity to witness the religious reforms promoted by Marguerite of Navarre, and to see women exercising power in a way still unfamiliar in England. Before her marriage to Henry, Anne – as an active promoter of French interests – was seen as a useful alternative to the Habsburg Catherine. But a few years later, when a Habsburg alliance was desirable, that French identification contributed to her fall.

Elizabeth I (Getty Images).

Elizabeth I (1533–1603)

Thanks in part to her long reign, Anne Boleyn’s daughter is remembered by many as England’s greatest monarch. She represents the apogee of an age of queens – which, however, was perhaps already waning before her death. Elizabeth might be seen as exemplifying many of the maxims laid down for powerful women at the beginning of the 16th century by the French regent Anne de Beaujeu (above). Elizabeth’s motto was Video et taceo – I see but say nothing. “Have eyes to notice everything yet to see nothing, ears to hear everything yet to know nothing,” Anne de Beaujeu had urged.

Elizabeth corresponded with Jeanne d’Albret, Catherine de Medici and the influential Ottoman consort Safiye. But the religious divisions of the Reformation denied her the easy contact with other women across the continent that had been enjoyed by earlier generations, and fostered her long rivalry with her Catholic kinswoman Mary, Queen of Scots.

Jeanne d’Albret (1528–72)

In 1555 Marguerite’s daughter Jeanne inherited her father’s Navarrese kingdom. Reared in her mother’s reforming tradition, in 1560 she publicly converted to the Protestant faith. Joining France’s Huguenot rebels inside the besieged fortress of La Rochelle, she became a heroine of the Reformation. When summoned to appear before the Inquisition, Jeanne was saved by the intervention of Catherine de Medici, even though the latter was on the other side of the religious divide. Catherine tried to promote religious tolerance, but the marriage of her daughter Marguerite to Jeanne’s son Henri in 1572 provoked the slaughter of Huguenots known as the Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (pictured below). “You cannot govern too wisely with kindness and diffidence,” Anne de Beaujeu had said – the final bitter ‘Lesson’ with which her daughters were to end the century.

St Bartholemes Day Massacre. (Getty images)

Mary I (1516–58)

Catherine of Aragon inculcated in her daughter Mary her own belief in the validity of her marriage to Henry VIII, and her own resolute Catholicism. “We never come unto the kingdom of Heaven but by troubles,” she assured her daughter. Mary’s determined resistance to her father’s religious reforms was attributed to her “unbridled Spanish blood”. She endured years of real hardship before, in 1553, the death of her younger brother Edward (and a passage of armed resistance reminiscent of her female forebears) brought her to the throne. Once on it, as observers noted, she always favoured Spain and promoted her mother’s religion. She married Philip of Spain and her efforts to restore the Catholic faith, involving the persecution of Protestants, earned her the sobriquet ‘Bloody Mary’.

Sarah Gristwood is the author of Game of Queens: The Women Who Made Sixteenth-Century Europe (Oneworld, 2016)

Isabella I of Castille, Anne de Beaujeu and Catherine of Aragon were three of the queens linked by a complex web of mothers, daughters, mentors and proteges. (Getty Images)

After her accession ceremony on 13 December 1474, Isabella of Castile rode through the streets of Segovia – behind a horseman holding a naked sword. Even her husband, Ferdinand of Aragon, was shocked, protesting that he had never before heard of a queen “who usurped this masculine attribute”. But Isabella’s reign ushered in an explosion of female rule, unequalled until our own day. In the 16th century, England, Scotland, France, the Netherlands, Spain, Portugal and Hungary all came at one time or another to be controlled by a woman, whether as regent or queen regnant.

These rulers were linked by a complex web of mothers and daughters, mentors and proteges. Lessons were passed from Isabella of Castile to her daughter Catherine of Aragon and thence Mary I, and from the French regent Anne de Beaujeu to Louise of Savoy, through Louise’s daughter Marguerite of Navarre to her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, to Marguerite’s admirer Anne Boleyn and thus to Elizabeth I.

Their experiences are echoed today. Headlines about Angela Merkel, Theresa May, Nicola Sturgeon and Hillary Clinton emphasise a powerful woman’s looks and likeability; the problem of gendered abuse, of seeming tough enough for high office without being dubbed unfeminine; the question of whether female leaders will relate to each other, and exercise their power, in a specifically female way.

The age of queens did not outlast the 16th century. Women had found themselves at the forefront of the great religious divides that tore Europe apart, but those divisions meant that, though Anne Boleyn could be educated in two foreign countries, her daughter Elizabeth never set foot out of her own land. We introduce 10 key female figures who dominated 16th-century Europe, and explore the relationships that linked them.

Isabella I of Castile (1451–1504)

Before she even took the throne, Isabella broke with tradition by arranging her own marriage to Ferdinand of Aragon, uniting the two main Spanish kingdoms. They ruled together as the mighty Catholic Monarchs, famous for their expulsion of the Moors and Jews, for establishing the Inquisition in Spain, and for their sponsorship of Christopher Columbus. Ferdinand and Isabella produced only one short-lived son but several influential daughters – among them Catherine of Aragon who in 1509 married England’s king Henry VIII.

Catherine of Aragon (1485–1536)

Catherine was defined by Spanish heritage. Henry VII of England sought the valuable Spanish alliance by wedding her to his eldest son, Arthur; after Arthur’s early death she married his younger brother, Henry VIII. As regent in 1513, “in imitation of her mother Isabella”, she rallied English troops to resist a Scottish assault. But as daughter to a successful queen regnant she was poorly placed to understand her husband’s obsessive desire for a son. When her marriage was rent by Henry’s infatuation with her former protege Anne Boleyn, Catherine still, after almost 30 years in England, described herself as a stranger in the land, appealing for help to her former sister-in-law Margaret of Austria.

Margaret of Austria (1480–1530)

The child of Mary of Burgundy (ruling duchess of what would later be known as the Netherlands) and future Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian, Margaret was, while still a toddler, contracted to the French king-to-be Charles VIII. When that alliance fell through she married Juan, heir of Isabella and Ferdinand, and then, after his early death, the Duke of Savoy. After he died she returned to the Netherlands where for many years she ruled as regent on behalf of her nephew, the future emperor Charles V. She raised four of his sisters, all of whom became queens consort – of France, Portugal, Denmark and Hungary. Mary of Hungary succeeded her aunt as regent of the Netherlands and raised another generation of influential nieces. Though Margaret of Austria never bore a living child, she has been called the Grand Mère – ‘Great Mother’ – of Europe.

Anne de Beaujeu. (Getty Images)

Anne de Beaujeu (aka Anne of France, 1461–1522)

Eldest daughter of the French king Louis XI, Anne was widely noted as a woman of great ability. The Salic Law, however, prohibited her from acceding to the throne. Instead, on Louis’ death she acted as regent in all but name during the minority of her younger brother Charles VIII. Anne wrote an advice manual for noblewomen, Enseignements [Lessons for my Daughter] that has been compared to Machiavelli’s The Prince. “When it comes to the government of their lands and affairs, [widows] must depend only on themselves; when it comes to sovereignty, they must not cede power to anyone,” was one of her maxims. Anne was in charge of the upbringings of Margaret of Austria during her marriage to Charles VIII, and of Louise of Savoy.

Louise of Savoy (1476–1531)

Louise’s status rose steadily as several French kings in succession died without heir until the closest in line to the throne was François, her son by the Count d’Angoulême. After François I became king in 1515, Louise was widely regarded as the power behind his throne. In 1529 she sat down with Margaret of Austria (her childhood playmate when they were both raised in Anne de Beaujeu’s care) to negotiate the so-called ‘Ladies’ Peace’ of Cambrai. Neither Louise’s son François nor Margaret’s nephew Charles could compromise their dignity by being the first to talk of reconciliation but, Margaret wrote: “How easy for ladies… to concur in some endeavours for warding off the general ruin of Christendom, and to make the first advance in such an undertaking!”

Marguerite of Navarre (aka Marguerite d’Angoulême, 1492–1549)

Louise of Savoy’s daughter Marguerite was also in Cambrai when the ‘Ladies’ Peace’ was negotiated. Louise, François and Marguerite were so close that they were known as ‘the trinity’; neither of Marguerite’s two marriages (to the Duc d’Alençon and to Henri II of Navarre) impeded her devotion to her brother, nor her sway over his court. Author of the book of short stories known as the Heptaméron, Marguerite was an intellectual leader among the great ladies who sought to reform the Catholic church. The number of ideas, books and contacts they had in common suggests that Marguerite became a role model for Anne Boleyn during the latter’s years in France. Anne would later send word to Marguerite that her “greatest wish, next to having a son, was to see you again”.

Anne Boleyn (c1501–36)