MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 40

November 3, 2017

Magnificent 2,000-Year-Old Marble Mosaic from Caligula's ‘Orgy Ship’ Ends up as Coffee Table in NYC Apartment

Ancient Origins

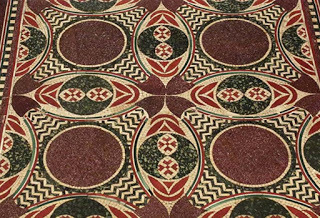

A valuable piece of mosaic flooring from one of Caligula’s ‘orgy ships’, so-called for the lavish sex parties he hosted on the boats, somehow found its way from the bottom of Lake Nemi to the Upper East Side in New York, and now it's finally heading back home in Italy.

From Rome to New York

The square slab of marble flooring, decorated with a floral motif made of pieces of green and red porphyry, serpentine and molded glass, was discovered at an Italian collector's Park Avenue apartment in New York City. So how did it end up being used as a coffee table in a Manhattan's apartment? Well, there’s a logical explanation to the “mystery.” As NBC News reports, the precious artifact, stolen from Italy's Roman Ship Museum after World War II, was seized by the New York district attorney's office from the collection of Helen Fioratti.

She and husband, Italian journalist Nereo Fioratti, purchased the piece more than 45-years-ago from an aristocratic family that lived on the lake, “It was found in the waters of the lake in the 19th century,” Fioratti told NBC News in a phone interview. While it was unknown to the Fioratti couple how much the Italian family paid for the ancient artifact, they both assumed that it cost them thousands of dollars and was a completely innocent purchase. She explained that when they decided to buy the rare mosaic back in the 1960s, they never considered it was stolen, as they had no reason to question the ownership, “They thought they owned it. We thought they owned it. Everyone thought they owned it," she told NBC News.

Mrs. Fioratti added that she didn’t know how the Italian police learned about the artifact and she speculates that may saw it in a magazine shoot of her apartment, “We had our apartment featured a long time ago in Architectural Digest and I’m sure there was a photograph of the table in front of the sofa,” she said as NBC News reported.

The ancient marble mosaic, which has now been returned to the Italian government in New York. Credit: Yana Paskova / The New York Times

The Long History of the Roman Artifact

The Roman artifact dates back to Caligula's reign, 37-41 AD and came from one of his three ships built at the volcanic Lake Nemi. The mosaic, as well as other ancient objects including two vases, bronzes, coins and manuscripts, were recovered thanks to an investigation carried out by the special art unit of the Carabinieri police led by Fabrizio Parrulli and US authorities.

The 2000-year-old piece of Roman history is extremely significant as it was once dredged from the lake outside Rome after laying underwater for centuries and is one of the few pieces left of Caligula's ships. Described as “floating palaces” by the Museum of Roman Ships, which houses the remains of the ships, they were notable for their luxury and are thought to have been the site of Caligula’s flamboyant ceremonies that lasted for days. The ships were over 70-meter-long and were richly decorated with marble, gold and bronze friezes of animals.

A marble bust of Emperor Caligula

The Fate of Caligula’s Ships

After Caligula was killed, his ships were sunk and remained underwater for centuries, despite efforts since the 19th century to find the treasures. Benito Mussolini was the first to launch an organized exploration of the lake and two vessels were retrieved between 1928 and 1932. In 1936, the Italian government of Mussolini built a museum, the Museo delle Navi inaugurated in 1940, to display the artwork. However, in 1944 an arson attack at the museum, which had been used as a bomb shelter, damaged many of the artifacts. Only a few decorations survived the fire, while other artifacts were taken away before the war, including the mosaic, according to NBC News. Two models representing the vessels are currently exhibited at the museum in Nemi. The third ship, which according to Suetonius in the Lives of the Caesars was the most luxurious of the three, was never retrieved.

Some of the decorations from Caligula’s Nemi ships: A bronze railing ( CC BY SA 2.0 ), a face (Miguel Hermoso Cuesta/ CC BY SA 3.0 ), and brass rings recovered in 1895. These were fitted to the ends of cantilevered beams that supported each rowing position on the seconda nave. ( CC BY SA 3.0)

Top image: The ancient marble mosaic, which has now been returned to the Italian government in New York. Credit: Yana Paskova / The New York Times

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on November 03, 2017 00:30

November 2, 2017

November 2 - All Souls' Day - Day of the Dead

The origins of All Souls' Day (Day of the Dead) in European folklore and folk belief are related to customs of ancestor veneration practiced worldwide, such as the Chinese Ghost Festival or the Latin American Day of the Dead.

The Roman custom was that of the Lemuria. The theological basis for the feast is the doctrine that the souls which, on departing from the body, are not perfectly cleansed from venial sins, or have not fully atoned for past transgressions, are debarred from the Beatific Vision, and that the faithful on earth can help them by prayers, alms, deeds, and especially by the sacrifice of the Mass.

Published on November 02, 2017 00:00

November 1, 2017

November 1 - All Saints Day

The origins of the holiday commemorating all the saints of the church are obscure, but by the mid-eighth century, November 1st was the day to honor all known and unknown saints in the Catholic Church. In 837, its general observance was ordered by Pope Gregory IV. The date may have been selected for its coincidence with pagan observations of the harvest, including the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain and the ancient Finnish celebration of Kekri.

Published on November 01, 2017 00:30

October 31, 2017

10 things you didn’t know about the history (and mystery) of Halloween

History Extra

1) Most people believe 31 October is an ancient pagan festival associated with the supernatural. In fact, it has religious connotations – although there is disagreement among historians about when it begun. Some say Hallowtide was introduced as All Saints’ Day in the 7th century AD by Pope Boniface IV, while others maintain it was created in the 9th century AD by Christians to commemorate their martyrs and saints.

In medieval Britain, ‘Halloween’ was the eve of the Catholic festival All Saints or All-Hallows (from Old English ‘Holy Man’) on 1 November, and was followed by the feast of All Souls on 2 November.

2) The tradition of carving a face on a turnip or swede (and more recently pumpkin), and using these as lanterns seems to be a relatively modern tradition. On the last Thursday in October, children in the Somerset village of Hinton St George carry lanterns made of mangel-wurzles (a type of root vegetable). The light shines through a design etched on the skin. They are carried around the streets as the children chant: “It’s Punky Night tonight, It’s Punky Night tonight, Give us a candle, give us a light, It’s Punky Night tonight.”

3) Much of the modern supernatural lore surrounding Halloween was invented as recently as the 19th century. Scots and Irish settlers brought the custom of Mischief Night visiting to North America, where it became known as ‘Trick or Treat’. Until the revival of interest in Halloween during the 1970s, this American tradition was largely unknown in England. The importation of ‘Trick or Treat’ into parts of England during the 1980s was helped by scenes in American TV programmes and the 1982 film E.T.

4) There is no evidence the pagan Anglo-Saxons celebrated a festival on 1 November, but the Venerable Bede says the month was known as ‘Blod-monath’ (blood month), when surplus livestock were slaughtered and offered as sacrifices. The truth is there is no written evidence that 31 October was linked to the supernatural in England before the 19th century.

5) In pre-Christian Ireland, 1 November was known as ‘Samhain’ (summer's end). This date marked the onset of winter in Gaelic-speaking areas of Britain. It was also the end of the pastoral farming year, when cattle were slaughtered and tribal gatherings such as the Irish Feis of Tara were held. In the 19th century the anthropologist Sir James Frazer popularised the idea of Samhain as an ancient Celtic festival of the dead, when pagan religious ceremonies were held.

6) The Catholic tradition of offering prayers to the dead, the ringing of church bells and lighting of candles and torches on 1 November provides the link with the spirit world. In medieval times, prayers were said for souls trapped in purgatory on 1 November. This was believed to be a sort of ‘halfway house’ on the road to Heaven, and it was thought their ghosts could return to earth to ask relatives for assistance in the journey.

7) Popular Halloween customs in England included ‘souling’, where groups of adults – and later children wearing costumes – visited big houses to sing and collect money and food. Souling was common in parts of Cheshire, Shropshire, Lancashire and Yorkshire on 1 and 2 November. In parts of northern England, special cakes were baked and left in churchyards as offerings to the dead.

8) Until the 19th century, bonfires were lit on Halloween in parts of northern England and Derbyshire. Some folklorists believe the enduring popularity of Guy Fawkes bonfires on 5 November may be a memory of an older fire festival, but there is a lack of written evidence for these in England before the late 17th century.

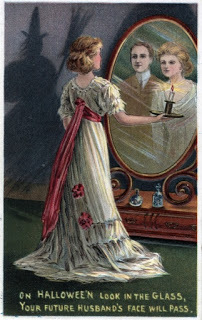

9) Love divinations on Halloween spread to England from Scotland as a result of the popularity of Robert Burn’s poem Halloween in Victorian times. One love divination mentioned by Burns includes placing hazelnuts in the fire, naming one for yourself and the other for your partner. If they burned gently and then went out, this indicated a long and harmonious life together; if they coughed and spluttered or exploded, this was a sign of problems ahead.

Apples were also used for divination purposes: the skin was thrown over the shoulder, or the fruit floated in water or hung upon strings, to be seized by the teeth of the players.

10) The idea of Halloween as a festival of supernatural evil forces is an entirely modern invention. Urban legends about razor blades in apples and cyanide in sweets, hauntings by restless spirits and the use of 31 October as the date of evil or inauspicious events in horror films, reflect modern fears and terrors.

Every year Halloween provokes controversy and divides opinions: most people see it as just as a bit of harmless fun, but modern witches say it marks an ancient pagan festival, while some evangelical Christians claim it is a celebration of dangerous occult forces. This explains why folklorist Steve Roud calls it “the most widely misunderstood and misrepresented day in the festival year”.

Dr David Clarke is a senior lecturer in journalism at Sheffield Hallam University. He holds a PhD in English cultural tradition and folklore, and a degree in archaeology, prehistory and medieval history.

1) Most people believe 31 October is an ancient pagan festival associated with the supernatural. In fact, it has religious connotations – although there is disagreement among historians about when it begun. Some say Hallowtide was introduced as All Saints’ Day in the 7th century AD by Pope Boniface IV, while others maintain it was created in the 9th century AD by Christians to commemorate their martyrs and saints.

In medieval Britain, ‘Halloween’ was the eve of the Catholic festival All Saints or All-Hallows (from Old English ‘Holy Man’) on 1 November, and was followed by the feast of All Souls on 2 November.

2) The tradition of carving a face on a turnip or swede (and more recently pumpkin), and using these as lanterns seems to be a relatively modern tradition. On the last Thursday in October, children in the Somerset village of Hinton St George carry lanterns made of mangel-wurzles (a type of root vegetable). The light shines through a design etched on the skin. They are carried around the streets as the children chant: “It’s Punky Night tonight, It’s Punky Night tonight, Give us a candle, give us a light, It’s Punky Night tonight.”

3) Much of the modern supernatural lore surrounding Halloween was invented as recently as the 19th century. Scots and Irish settlers brought the custom of Mischief Night visiting to North America, where it became known as ‘Trick or Treat’. Until the revival of interest in Halloween during the 1970s, this American tradition was largely unknown in England. The importation of ‘Trick or Treat’ into parts of England during the 1980s was helped by scenes in American TV programmes and the 1982 film E.T.

4) There is no evidence the pagan Anglo-Saxons celebrated a festival on 1 November, but the Venerable Bede says the month was known as ‘Blod-monath’ (blood month), when surplus livestock were slaughtered and offered as sacrifices. The truth is there is no written evidence that 31 October was linked to the supernatural in England before the 19th century.

5) In pre-Christian Ireland, 1 November was known as ‘Samhain’ (summer's end). This date marked the onset of winter in Gaelic-speaking areas of Britain. It was also the end of the pastoral farming year, when cattle were slaughtered and tribal gatherings such as the Irish Feis of Tara were held. In the 19th century the anthropologist Sir James Frazer popularised the idea of Samhain as an ancient Celtic festival of the dead, when pagan religious ceremonies were held.

6) The Catholic tradition of offering prayers to the dead, the ringing of church bells and lighting of candles and torches on 1 November provides the link with the spirit world. In medieval times, prayers were said for souls trapped in purgatory on 1 November. This was believed to be a sort of ‘halfway house’ on the road to Heaven, and it was thought their ghosts could return to earth to ask relatives for assistance in the journey.

7) Popular Halloween customs in England included ‘souling’, where groups of adults – and later children wearing costumes – visited big houses to sing and collect money and food. Souling was common in parts of Cheshire, Shropshire, Lancashire and Yorkshire on 1 and 2 November. In parts of northern England, special cakes were baked and left in churchyards as offerings to the dead.

8) Until the 19th century, bonfires were lit on Halloween in parts of northern England and Derbyshire. Some folklorists believe the enduring popularity of Guy Fawkes bonfires on 5 November may be a memory of an older fire festival, but there is a lack of written evidence for these in England before the late 17th century.

9) Love divinations on Halloween spread to England from Scotland as a result of the popularity of Robert Burn’s poem Halloween in Victorian times. One love divination mentioned by Burns includes placing hazelnuts in the fire, naming one for yourself and the other for your partner. If they burned gently and then went out, this indicated a long and harmonious life together; if they coughed and spluttered or exploded, this was a sign of problems ahead.

Apples were also used for divination purposes: the skin was thrown over the shoulder, or the fruit floated in water or hung upon strings, to be seized by the teeth of the players.

10) The idea of Halloween as a festival of supernatural evil forces is an entirely modern invention. Urban legends about razor blades in apples and cyanide in sweets, hauntings by restless spirits and the use of 31 October as the date of evil or inauspicious events in horror films, reflect modern fears and terrors.

Every year Halloween provokes controversy and divides opinions: most people see it as just as a bit of harmless fun, but modern witches say it marks an ancient pagan festival, while some evangelical Christians claim it is a celebration of dangerous occult forces. This explains why folklorist Steve Roud calls it “the most widely misunderstood and misrepresented day in the festival year”.

Dr David Clarke is a senior lecturer in journalism at Sheffield Hallam University. He holds a PhD in English cultural tradition and folklore, and a degree in archaeology, prehistory and medieval history.

Published on October 31, 2017 00:00

October 30, 2017

Did a Native American travel with the Vikings and arrive in Iceland centuries before Columbus set sail?

Ancient Origins

Scientists have been searching for answers on the puzzles of history by sifting through the genetic code of certain Icelanders. They have been looking to see if a Native American woman from the New World accompanied the Vikings back to Europe, five centuries before Columbus arrived back in Spain with indigenous Native Americans.

It is well established through historical accounts and archaeological findings that Vikings set up initial colonies on the shores of North America just before 1000 A.D. But what is not known for certain is how a family of Icelanders came to have a genetic makeup which includes a surprising marker dating to 1000 A.D. — one which is found mostly in Native Americans.

In 2010, it was reported that the first Native Americans arrived on the continent of Europe sometime around the 11th century. The study, led by deCODE Genetics, a world-leading genome research lab in Iceland, discovered a unique gene that was present in only four distinct family lines. The DNA lineage, which was named C1e, is mitochondrial, meaning that the genes were introduced by and passed down through a female. Based on the evidence of the DNA, it has been suggested that a Native American, (voluntarily or involuntarily) accompanied the Vikings when they returned back to Iceland. The woman survived the voyage across the sea, and subsequently had children in her new home. As of today, there are 80 Icelanders who have the distinct gene passed down by this woman.

Nevertheless, there is another explanation for the presence of the C1e in these 80 Icelanders. It is possible that the Native American genes appeared in Iceland after the discovery of the New World by Columbus. It has been suggested that a Native American woman might have been brought back to mainland Europe by European explorers, who then found her way to Iceland. Researchers believe that this scenario is unlikely, however, given the fact that Iceland was pretty isolated at that point of time.

Nevertheless, the only way to effectively eliminate this possibility is for scientists to find the remains of a pre-Columbian Icelander whose genes can be analyzed and shown to contain the C1e lineage.

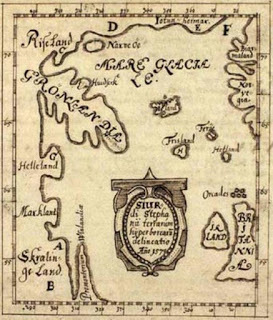

The Skálholt Map made by the Icelandic teacher Sigurd Stefansson in the year 1570. Helleland ('Stone Land' = Baffin island), Markland ('forest land' = Labrador), Skrælinge Land ('land of the foreigners’ = Labrador), Promontorium Vinlandiæ (the of Vinland = Newfoundland). Public Domain

Another problem facing the researchers is that the C1e genes might not have come from Native Americans, but from some other part of the world. For instance, no living Native American group has the exact DNA lineage as the one found in the 80 Icelanders. However, it may be that the Native American people who carried that lineage eventually went extinct.

One suggestion, which was proposed early in the research, was that the genes came from Asia. This was eventually ruled out, as the researchers managed to work out that the C1e lineage had been present in Iceland as early as the 18th century. This was long before the appearance of Asian genes in Icelanders.

Did a Native American travel to Iceland and leave behind a telltale genetic marker? A man helms replica Viking vessels. Wikimedia Commons

If the discovery does prove ultimately that the Vikings took a Native American woman back to Iceland, then history would indeed have to be rewritten. Although encounters with the Native Americans, known as Skraelings (or foreigners), were recorded by the Viking sagas, there is no mention whatsoever about the Vikings bringing a Native American woman home to Iceland with them. Furthermore, the available archaeological record does not show any presence of a Native American woman in Iceland.

The more digging is done into the history of the Vikings, the more our perceptions are changing as to how they lived, travelled, and traded.

Hopefully more light will be shed on this mystery over time, and the goings-on of the historic world can be unequivocally established, giving us a clearer understanding of our ancient past.

Featured image: Replica of 9th century Viking ship docked in Norway. Juanjo Marin/Flickr

References

Firth, N., 2010. First American in Europe 'was native woman kidnapped by Vikings and hauled back to Iceland 1,000 years ago'.

Govan, F., 2010. First Americands 'reached Europe five centuries before Columbus voyages'.

Watson, T., 2010. American Indian Sailed to Europe With Vikings?.

Tremlett, G. 2010. First Americans 'reached Europe five centuries before Columbus discoveries'. [Online] Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/science/20...

By Ḏḥwty

Published on October 30, 2017 00:30

October 29, 2017

Who or what killed Alexander the Great?

Ancient Origins

In June 323 BC, Alexander the Great died in Babylon aged 32, having conquered an empire stretching from modern Albania to eastern Pakistan. The question of what, or who, killed the Macedonian king has never been answered successfully. However, new research may have finally solved the 2,000-year-old mystery.

Alexander III of Macedon, also known as Alexander the Great, was born in Pella in 356 BC and was mentored by Aristotle until the age of 16. He became king of Macedon, a state in northern ancient Greece, and by the age of 30 had created one of the largest empires of the ancient world, stretching from the Ionian Sea to the Himalayas. Alexander is considered one of history's most successful commanders. He conquered the whole of the Persian Empire but being an ambitious warrior, seeking to reach the 'ends of the world,' he invaded India in 326 BC but later turned back. He is credited with founding some 20 cities that bore his name, including Alexandria in ancient Egypt, and spread Greece's culture east. However, before completing his plans to invade Arabia, Alexander the Great died of a mysterious death, following 12 days of suffering.

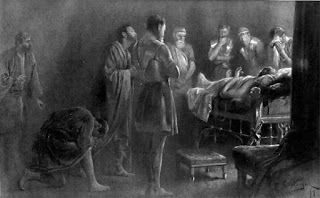

What is known from historical records is that Alexander was holding a memorial feast to honour the death of a close personal friend. But around mid-evening, he was seized with intense pain and collapsed. He was taken to his bedchamber where, after days of agony, high fever, convulsions and delirium, he fell into a coma and died.

His initial systems were agitation, tremors, stiffness in the neck, and sharp pain in the area of the stomach. He then collapsed and suffered acute and excruciating agony wherever he was touched. He experienced an intense thirst, fever and delirium, and throughout the night he experienced convulsions and hallucinations, followed by periods of calm. In the final stages of the condition he could not talk, although he could still move his head and arms. Ultimately, his breathing became difficult and he died.

Alexander the Great on his deathbed. Image source.

The four most popular theories concerning his death are: Malaria, typhoid, alcohol poisoning, or being intentionally poisoned by a rival. Three can probably be discounted. Malaria is carried by mosquitoes that live in jungle and tropical locations, but not in desert regions such as central Iraq where Alexander died. Typhoid is transmitted by food or water contaminated by bacteria which causes epidemics and not just single, individual cases. There is nothing in any of the historical accounts to suggest such outbreak in Babylon at the time Alexander died. The main effect of alcohol poisoning is continual vomiting, but not once do any of the historical sources mention vomiting or even nausea as one of Alexander’s symptoms.

So what did kill Alexander? According to the historical accounts, Alexander’s body failed to show any signs of decay for six days after death, even though it was kept in a hot, sultry place. One explanation is a lethal dose of a toxic substance that pervaded the corpse and slowed the rate of decomposition. This suggests that Alexander the Great was poisoned, but by what?

Recent research conducted by Dr Leo Schep from the National Poisons Centre in New Zealand suggests that Alexander died from drinking poisonous wine from an innocuous-looking plant that, when fermented, is incredibly deadly.

Dr Schep, who has been researching the toxicological evidence for a decade, said some of the other poisoning theories - including arsenic and strychnine - were not plausible as death would have come far too fast, not over 12 days as the records suggest. The same applies to other poisons such as hemlock, aconite, wormwood, henbane and autumn crocus.

However, Dr Schep’s research, co-authored by Otago University classics expert Dr Pat Wheatley and published in the medical journal Clinical Toxicology, found the most plausible culprit was Veratrum album, known as white hellebore. The white-flowered plant, which can be fermented into a poisonous wine, was well-known to the Greeks as a herbal treatment.

Dr Schep's theory was that Veratrum album could have been fermented as a wine that was given to the leader. It would have tasted 'very bitter' but it could have been sweetened - and Alexander was likely to have been very drunk at the banquet. The symptoms caused by consuming the plant also fit with the description of what Alexander experienced over the 12 days before he died.

However, even if Alexander were poisoned, there's no proof that he was murdered by conspiring generals. There have been documented cases of people accidentally poisoning themselves with Veratum album. In 2010, Clinical Toxicology published a paper about four people in Central Europe who thought they were eating wild garlic. In about 30 minutes they were throwing up, in pain, partially blind, and confused. Unlike, perhaps, Alexander, they all survived.

By April Holloway

Published on October 29, 2017 00:30

October 28, 2017

Ten amazing inventions from ancient times

Ancient Origins

Dating back thousands of years are numerous examples of ancient technology that leave us awe-struck at the knowledge and wisdom held by people of our past. They were the result of incredible advances in engineering and innovation as new, powerful civilizations emerged and came to dominate the ancient world. These advances stimulated societies to adopt new ways of living and governance, as well as new ways of understanding their world. However, many ancient inventions were forgotten, lost to the pages of history, only to be re-invented millennia later. Here we feature ten of the best examples of ancient technology and inventions that demonstrate the ingenuity of our ancient ancestors.

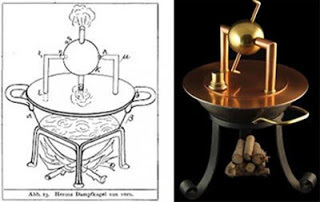

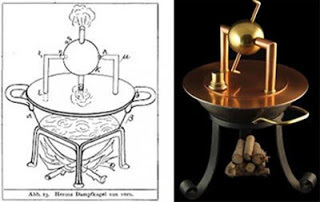

1. The ancient invention of the steam engine by the Hero of Alexandria

Heron Alexandrinus, otherwise known as the Hero of Alexandria, was a 1st century Greek mathematician and engineer who is known as the first inventor of the steam engine. His steam powered device was called the aeolipile, named after Aiolos, God of the winds. The aeolipile consisted of a sphere positioned in such a way that it could rotate around its axis. Nozzles opposite each other would expel steam and both of the nozzles would generate a combined thrust resulting in torque, causing the sphere to spin around its axis. The rotation force sped up the sphere up to the point where the resistance from traction and air brought it to a stable rotation speed. The steam was created by boiling water under the sphere – the boiler was connected to the rotating sphere through a pair of pipes that at the same time served as pivots for the sphere. The replica of Heron’s machine could rotate at 1,500 rounds per minute with a very low pressure of 1.8 pounds per square inch. The remarkable device was forgotten and never used properly until 1577, when the steam engine was ‘re-invented’ by the philosopher, astronomer and engineer, Taqu al-Din.

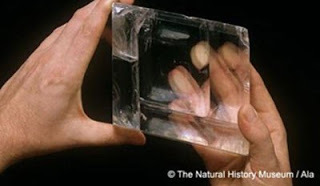

2. Is the Assyrian Nimrud lens the oldest telescope in the world?

The Nimrud lens is a 3,000-year-old piece of rock crystal, which was unearthed by Sir John Layard in 1850 at the Assyrian palace of Nimrud, in modern-day Iraq. The Nimrud lens (also called the Layard lens) is made from natural rock crystal and is a slightly oval in shape. It was roughly ground, perhaps on a lapidary wheel. It has a focal point about 11 centimetres from the flat side, and a focal length of about 12 cm. This would make it equivalent to a 3× magnifying glass (combined with another lens, it could achieve much greater magnification). The surface of the lens has twelve cavities that were opened during grinding, which would have contained naptha or some other fluid trapped in the raw crystal. Since its discovery over a century ago, scientists and historians have debated its use, with some suggesting it was used as a magnifying glass, and others maintaining it was a burning-glass used to start fires by concentrating sunlight. However, prominent Italian professor Giovanni Pettinato proposed the lens was used by the ancient Assyrians as part of a telescope, which would explain how the Assyrians knew so much about astronomy. According to conventional perspectives, the telescope was invented by Dutch spectacle maker, Hans Lippershey in 1608 AD, and Galileo was the first to point it to the sky and use it to study the cosmos. But even Galileo himself noted that the 'ancients' were aware of telescopes long before him. While lenses were around before the Nimrud lens, Pettinato believes this was one of the first to be used in a telescope.

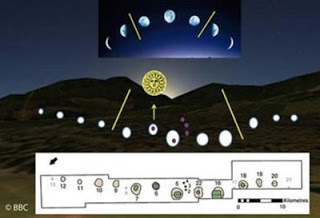

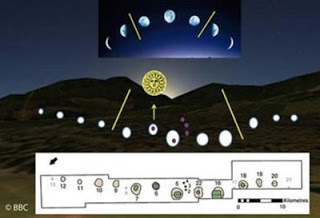

3. The Oldest Calendar in Scotland

Research carried out last year on an ancient site excavated by the National Trust for Scotland in 2004 revealed that it contained a sophisticated calendar system that is approximately 10,000 years old, making it the oldest calendar ever discovered in the world. The site – at Warren Field, Crathes, Aberdeenshire – contains a 50 metre long row of twelve pits which were created by Stone Age Britons and which were in use from around 8000 BC (the early Mesolithic period) to around 4,000 BC (the early Neolithic). The pits represent the months of the year as well as the lunar phases of the moon. They were formed in a complex arc design in which each lunar month was divided into three roughly ten day weeks – representing the waxing moon, the full moon and the waning moon. It also allowed the observation of the mid-winter sunrise so that the lunar calendar could be recalibrated each year to bring it back in line with the solar year. The entire arc represents a whole year and may also reflect the movements of the moon across the sky.

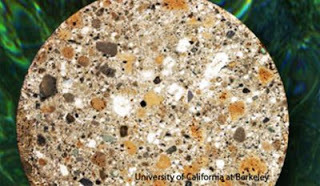

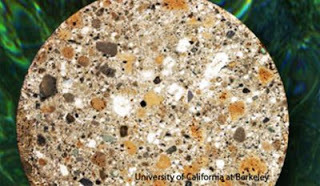

4. Ancient Roman Concrete was Far Superior to Our Own

Scientists studying the composition of Roman concrete, which has been submerged under the Mediterranean Sea for the last 2,000 years, discovered that it was superior to modern-day concrete in terms of durability and being less environmentally damaging. The Romans made concrete by mixing lime and volcanic rock. For underwater structures, the combination of lime and volcanic ash with seawater instantly triggered a chemical reaction in which the lime incorporated molecules into its structure and reacted with the ash to cement the whole mixture together. Analysis of the concrete found that it produces a significantly different compound to modern day cement, which is an incredibly stable binder. In addition, the ancient concrete contains the ideal crystalline structure of Tobermorite, which has a greater strength and durability than the modern equivalent. Finally, microscopic studies identified other minerals in the ancient concrete which show potential application for high-performance concretes, including the encapsulation of hazardous wastes. "In the middle 20th century, concrete structures were designed to last 50 years," said scientist Paulo Monteiro said. "Yet Roman harbour installations have survived 2,000 years of chemical attack and wave action underwater.”

5. 2000-year-old metal coatings superior to today’s standards

Research has shown that artisans and craftsmen 2,000 years ago used a form of ancient technology for applying thin films of metal to statues and other items, which was superior to today’s standards for producing DVDs, solar cells, electronic devices and other products. Fire gilding and silvering are age-old mercury-based processes used to coat the surface items such as jewels, statues and amulets with thin layers of gold or silver. From a technological point of view, what the ancient gilders achieved 2000 years ago, was to make the metal coatings incredibly thin, adherent and uniform, which saved expensive metals and improved its durability, something which has never been achieved to the same standard today. Apparently without any knowledge about the chemical–physical processes, ancient craftsmen systematically manipulated metals to create spectacular results. They developed a variety of techniques, including using mercury like a glue to apply thin films of metals to objects. The findings demonstrate that there was a far higher level of understanding and knowledge of advanced concepts and techniques in our ancient past than what they are given credit for.

6. The incredible 2000-year-old earthquake detector

Although we still cannot accurately predict earthquakes, we have come a long way in detecting, recording, and measuring seismic shocks. Many don’t realise that this process began nearly 2000 years ago, with the invention of the first seismoscope in 132 AD by a Chinese astronomer, mathematician, engineer, and inventor called Zhang (‘Chang’) Heng. The device was remarkably accurate in detecting earthquakes from afar, and did not rely on shaking or movement in the location where the device was situated. Zhang's seismoscope was a giant bronze vessel, resembling a samovar almost 6 feet in diameter. Eight dragons snaked face-down along the outside of the barrel, marking the primary compass directions. In each dragon's mouth was a small bronze ball. Beneath the dragons sat eight bronze toads, with their broad mouths gaping to receive the balls. The sound of the ball striking one of the eight toads would alert observers to the earthquake and would give a rough indication of the earthquake's direction of origin. In 2005, scientists in Zengzhou, China (which was also Zhang's hometown) managed to replicate Zhang's seismoscope and used it to detect simulated earthquakes based on waves from four different real-life earthquakes in China and Vietnam. The seismoscope detected all of them. As a matter of fact, the data gathered from the tests corresponded accurately with that gathered by modern-day seismometers!

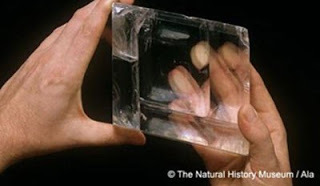

7. Mythical sunstone used as ancient navigational device

An ancient Norse myth described a magical gem used to navigate the seas, which could reveal the position of the sun when hidden behind clouds or even before dawn or after sunset. Now it appears the myth is in fact true. In March 2013, a team of scientists announced that a unique calcite crystal, which was found in the wreck of an Elizabethan ship sunk off the Channel Islands, contains properties consistent with the legendary Viking sunstone and that shards of the crystal can indeed act as a remarkably precise navigational aid. According to the researchers, the principle behind the sunstone relies on its unusual property of creating a double refraction of sunlight, even when it is obscured by cloud or fog. By turning the crystal in front of the human eye until the darkness of the two shadows are equal, the sun's position can be pinpointed with remarkable accuracy.

8. The Baghdad Battery

The Baghdad Battery, sometimes referred to as the Parthian Battery, is a clay pot which encapsulates a copper cylinder. Suspended in the centre of this cylinder—but not touching it—is an iron rod. Both the copper cylinder and the iron rod are held in place with an asphalt plug. These artifacts (more than one was found) were discovered during the 1936 excavations of the old village Khujut Rabu, near Baghdad. The village is considered to be about 2000 years old, and was built during the Parthian period (250BC to 224 AD). Although it is not known exactly what the use of such a device would have been, the name ‘Baghdad Battery’, comes from one of the prevailing theories established in 1938 when Wilhelm Konig, the German archaeologist who performed the excavations, examined the battery and concluded that this device was an ancient electric battery. After the Second World War, Willard Gray, an American working at the General Electric High Voltage Laboratory in Pittsfield, built replicas and, filling them with an electrolyte, found that the devices could produce 2 volts of electricity. The question remains, if it really was a battery, what was it used to power?

9. 1,600-year-old goblet shows that the Romans used nanotechnology

The Lycurgus Cup, as it is known due to its depiction of a scene involving King Lycurgus of Thrace, is a 1,600-year-old jade green Roman chalice that changes colour depending on the direction of the light upon it. It baffled scientists ever since the glass chalice was acquired by the British Museum in the 1950s. They could not work out why the cup appeared jade green when lit from the front but blood red when lit from behind. The mystery was solved in 1990, when researchers in England scrutinized broken fragments under a microscope and discovered that the Roman artisans were nanotechnology pioneers: they had impregnated the glass with particles of silver and gold, ground down until they were as small as 50 nanometres in diameter, less than one-thousandth the size of a grain of table salt. The work was so precise that there is no way that the resulting effect was an accident. In fact, the exact mixture of the metals suggests that the Romans had perfected the use of nanoparticles. When hit with light, electrons belonging to the metal flecks vibrate in ways that alter the colour depending on the observer’s position.

10. The ancient Antikythera mechanism

The Antikythera mechanism was discovered in 1900 during the recovery of a shipwreck off of the Greek island, Antikythera, in waters 60 meters deep. It is a metallic device which consists of a complex combination of gears, and dates back to the 2nd century BCE. The Antikythera mechanism is one of the most amazing mechanical devices discovered from the ancient world. For decades, scientists have utilized the latest technology in attempts to decipher its functionality; however, due to its complexity, its true purpose and function remained elusive. But in the last few years, a number of scientists appear to have solved the mystery as to precisely how this incredible piece of technology once worked. Peter Lynch, professor of meteorology at University College Dublin, explains: “The mechanism was driven by a handle that turned a linked system of more than 30 gear wheels…The gears were coupled to pointers on the front and back of the mechanism, showing the positions of the sun, moon and planets as they moved through the zodiac. An extendable arm with a pin followed a spiral groove, like a record player stylus. A small sphere, half white and half black, indicated the phase of the moon. Even more impressive was the prediction of solar and lunar eclipses.” Amazingly, the device even included a dial to indicate which of the pan-Hellenic games would take place each year, with the Olympics occurring every fourth year. Just one small cog out of 30 remains a mystery and it is hoped that further research can place this last piece in the puzzle.

By April Holloway

Dating back thousands of years are numerous examples of ancient technology that leave us awe-struck at the knowledge and wisdom held by people of our past. They were the result of incredible advances in engineering and innovation as new, powerful civilizations emerged and came to dominate the ancient world. These advances stimulated societies to adopt new ways of living and governance, as well as new ways of understanding their world. However, many ancient inventions were forgotten, lost to the pages of history, only to be re-invented millennia later. Here we feature ten of the best examples of ancient technology and inventions that demonstrate the ingenuity of our ancient ancestors.

1. The ancient invention of the steam engine by the Hero of Alexandria

Heron Alexandrinus, otherwise known as the Hero of Alexandria, was a 1st century Greek mathematician and engineer who is known as the first inventor of the steam engine. His steam powered device was called the aeolipile, named after Aiolos, God of the winds. The aeolipile consisted of a sphere positioned in such a way that it could rotate around its axis. Nozzles opposite each other would expel steam and both of the nozzles would generate a combined thrust resulting in torque, causing the sphere to spin around its axis. The rotation force sped up the sphere up to the point where the resistance from traction and air brought it to a stable rotation speed. The steam was created by boiling water under the sphere – the boiler was connected to the rotating sphere through a pair of pipes that at the same time served as pivots for the sphere. The replica of Heron’s machine could rotate at 1,500 rounds per minute with a very low pressure of 1.8 pounds per square inch. The remarkable device was forgotten and never used properly until 1577, when the steam engine was ‘re-invented’ by the philosopher, astronomer and engineer, Taqu al-Din.

2. Is the Assyrian Nimrud lens the oldest telescope in the world?

The Nimrud lens is a 3,000-year-old piece of rock crystal, which was unearthed by Sir John Layard in 1850 at the Assyrian palace of Nimrud, in modern-day Iraq. The Nimrud lens (also called the Layard lens) is made from natural rock crystal and is a slightly oval in shape. It was roughly ground, perhaps on a lapidary wheel. It has a focal point about 11 centimetres from the flat side, and a focal length of about 12 cm. This would make it equivalent to a 3× magnifying glass (combined with another lens, it could achieve much greater magnification). The surface of the lens has twelve cavities that were opened during grinding, which would have contained naptha or some other fluid trapped in the raw crystal. Since its discovery over a century ago, scientists and historians have debated its use, with some suggesting it was used as a magnifying glass, and others maintaining it was a burning-glass used to start fires by concentrating sunlight. However, prominent Italian professor Giovanni Pettinato proposed the lens was used by the ancient Assyrians as part of a telescope, which would explain how the Assyrians knew so much about astronomy. According to conventional perspectives, the telescope was invented by Dutch spectacle maker, Hans Lippershey in 1608 AD, and Galileo was the first to point it to the sky and use it to study the cosmos. But even Galileo himself noted that the 'ancients' were aware of telescopes long before him. While lenses were around before the Nimrud lens, Pettinato believes this was one of the first to be used in a telescope.

3. The Oldest Calendar in Scotland

Research carried out last year on an ancient site excavated by the National Trust for Scotland in 2004 revealed that it contained a sophisticated calendar system that is approximately 10,000 years old, making it the oldest calendar ever discovered in the world. The site – at Warren Field, Crathes, Aberdeenshire – contains a 50 metre long row of twelve pits which were created by Stone Age Britons and which were in use from around 8000 BC (the early Mesolithic period) to around 4,000 BC (the early Neolithic). The pits represent the months of the year as well as the lunar phases of the moon. They were formed in a complex arc design in which each lunar month was divided into three roughly ten day weeks – representing the waxing moon, the full moon and the waning moon. It also allowed the observation of the mid-winter sunrise so that the lunar calendar could be recalibrated each year to bring it back in line with the solar year. The entire arc represents a whole year and may also reflect the movements of the moon across the sky.

4. Ancient Roman Concrete was Far Superior to Our Own

Scientists studying the composition of Roman concrete, which has been submerged under the Mediterranean Sea for the last 2,000 years, discovered that it was superior to modern-day concrete in terms of durability and being less environmentally damaging. The Romans made concrete by mixing lime and volcanic rock. For underwater structures, the combination of lime and volcanic ash with seawater instantly triggered a chemical reaction in which the lime incorporated molecules into its structure and reacted with the ash to cement the whole mixture together. Analysis of the concrete found that it produces a significantly different compound to modern day cement, which is an incredibly stable binder. In addition, the ancient concrete contains the ideal crystalline structure of Tobermorite, which has a greater strength and durability than the modern equivalent. Finally, microscopic studies identified other minerals in the ancient concrete which show potential application for high-performance concretes, including the encapsulation of hazardous wastes. "In the middle 20th century, concrete structures were designed to last 50 years," said scientist Paulo Monteiro said. "Yet Roman harbour installations have survived 2,000 years of chemical attack and wave action underwater.”

5. 2000-year-old metal coatings superior to today’s standards

Research has shown that artisans and craftsmen 2,000 years ago used a form of ancient technology for applying thin films of metal to statues and other items, which was superior to today’s standards for producing DVDs, solar cells, electronic devices and other products. Fire gilding and silvering are age-old mercury-based processes used to coat the surface items such as jewels, statues and amulets with thin layers of gold or silver. From a technological point of view, what the ancient gilders achieved 2000 years ago, was to make the metal coatings incredibly thin, adherent and uniform, which saved expensive metals and improved its durability, something which has never been achieved to the same standard today. Apparently without any knowledge about the chemical–physical processes, ancient craftsmen systematically manipulated metals to create spectacular results. They developed a variety of techniques, including using mercury like a glue to apply thin films of metals to objects. The findings demonstrate that there was a far higher level of understanding and knowledge of advanced concepts and techniques in our ancient past than what they are given credit for.

6. The incredible 2000-year-old earthquake detector

Although we still cannot accurately predict earthquakes, we have come a long way in detecting, recording, and measuring seismic shocks. Many don’t realise that this process began nearly 2000 years ago, with the invention of the first seismoscope in 132 AD by a Chinese astronomer, mathematician, engineer, and inventor called Zhang (‘Chang’) Heng. The device was remarkably accurate in detecting earthquakes from afar, and did not rely on shaking or movement in the location where the device was situated. Zhang's seismoscope was a giant bronze vessel, resembling a samovar almost 6 feet in diameter. Eight dragons snaked face-down along the outside of the barrel, marking the primary compass directions. In each dragon's mouth was a small bronze ball. Beneath the dragons sat eight bronze toads, with their broad mouths gaping to receive the balls. The sound of the ball striking one of the eight toads would alert observers to the earthquake and would give a rough indication of the earthquake's direction of origin. In 2005, scientists in Zengzhou, China (which was also Zhang's hometown) managed to replicate Zhang's seismoscope and used it to detect simulated earthquakes based on waves from four different real-life earthquakes in China and Vietnam. The seismoscope detected all of them. As a matter of fact, the data gathered from the tests corresponded accurately with that gathered by modern-day seismometers!

7. Mythical sunstone used as ancient navigational device

An ancient Norse myth described a magical gem used to navigate the seas, which could reveal the position of the sun when hidden behind clouds or even before dawn or after sunset. Now it appears the myth is in fact true. In March 2013, a team of scientists announced that a unique calcite crystal, which was found in the wreck of an Elizabethan ship sunk off the Channel Islands, contains properties consistent with the legendary Viking sunstone and that shards of the crystal can indeed act as a remarkably precise navigational aid. According to the researchers, the principle behind the sunstone relies on its unusual property of creating a double refraction of sunlight, even when it is obscured by cloud or fog. By turning the crystal in front of the human eye until the darkness of the two shadows are equal, the sun's position can be pinpointed with remarkable accuracy.

8. The Baghdad Battery

The Baghdad Battery, sometimes referred to as the Parthian Battery, is a clay pot which encapsulates a copper cylinder. Suspended in the centre of this cylinder—but not touching it—is an iron rod. Both the copper cylinder and the iron rod are held in place with an asphalt plug. These artifacts (more than one was found) were discovered during the 1936 excavations of the old village Khujut Rabu, near Baghdad. The village is considered to be about 2000 years old, and was built during the Parthian period (250BC to 224 AD). Although it is not known exactly what the use of such a device would have been, the name ‘Baghdad Battery’, comes from one of the prevailing theories established in 1938 when Wilhelm Konig, the German archaeologist who performed the excavations, examined the battery and concluded that this device was an ancient electric battery. After the Second World War, Willard Gray, an American working at the General Electric High Voltage Laboratory in Pittsfield, built replicas and, filling them with an electrolyte, found that the devices could produce 2 volts of electricity. The question remains, if it really was a battery, what was it used to power?

9. 1,600-year-old goblet shows that the Romans used nanotechnology

The Lycurgus Cup, as it is known due to its depiction of a scene involving King Lycurgus of Thrace, is a 1,600-year-old jade green Roman chalice that changes colour depending on the direction of the light upon it. It baffled scientists ever since the glass chalice was acquired by the British Museum in the 1950s. They could not work out why the cup appeared jade green when lit from the front but blood red when lit from behind. The mystery was solved in 1990, when researchers in England scrutinized broken fragments under a microscope and discovered that the Roman artisans were nanotechnology pioneers: they had impregnated the glass with particles of silver and gold, ground down until they were as small as 50 nanometres in diameter, less than one-thousandth the size of a grain of table salt. The work was so precise that there is no way that the resulting effect was an accident. In fact, the exact mixture of the metals suggests that the Romans had perfected the use of nanoparticles. When hit with light, electrons belonging to the metal flecks vibrate in ways that alter the colour depending on the observer’s position.

10. The ancient Antikythera mechanism

The Antikythera mechanism was discovered in 1900 during the recovery of a shipwreck off of the Greek island, Antikythera, in waters 60 meters deep. It is a metallic device which consists of a complex combination of gears, and dates back to the 2nd century BCE. The Antikythera mechanism is one of the most amazing mechanical devices discovered from the ancient world. For decades, scientists have utilized the latest technology in attempts to decipher its functionality; however, due to its complexity, its true purpose and function remained elusive. But in the last few years, a number of scientists appear to have solved the mystery as to precisely how this incredible piece of technology once worked. Peter Lynch, professor of meteorology at University College Dublin, explains: “The mechanism was driven by a handle that turned a linked system of more than 30 gear wheels…The gears were coupled to pointers on the front and back of the mechanism, showing the positions of the sun, moon and planets as they moved through the zodiac. An extendable arm with a pin followed a spiral groove, like a record player stylus. A small sphere, half white and half black, indicated the phase of the moon. Even more impressive was the prediction of solar and lunar eclipses.” Amazingly, the device even included a dial to indicate which of the pan-Hellenic games would take place each year, with the Olympics occurring every fourth year. Just one small cog out of 30 remains a mystery and it is hoped that further research can place this last piece in the puzzle.

By April Holloway

Published on October 28, 2017 00:00

October 27, 2017

Volcanic Eruptions and Climate Change Incited Upheaval in Ancient Egypt - and Historians Warn of Repetition

Ancient Origins

The Nile river was the lifeblood of ancient Egypt. When the waterway flooded nearby lands things were good, but a lack of that precious water caused serious issues. Now, historians have found that the famous waterway could have been negatively impacted at key moments in the Ptolemaic period – inciting social, political, and economic upheavals. Most surprisingly, it seems that the lack of Nile flooding could have been set off by volcanic eruptions altering the climate.

The results of research on the link between the climatic impact in ancient Egypt by volcanoes was recently published in Nature Communications. In the paper, the authors explain that “Explosive eruptions can perturb climate by injecting sulfurous gases into the stratosphere; these gases react to form reflective sulfate aerosols that remain aloft in decreasing concentrations for approximately one to two years.” Through a chain of events, those sulfurous gases cool the atmosphere, and if that takes place in the Northern Hemisphere, monsoon rains may not move as far as they usually do.

Merapi volcano, eruption at night. (1865) Raden Saleh. (Public Domain)

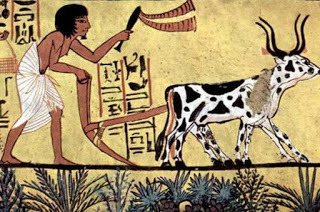

Francis Ludlow, a climate historian at Trinity College in Dublin and a co-author of the study, explained to EurekAlert! how those climatic events impacted the Nile River, “When the monsoon rains don't move far enough north, you don't have as much rain falling over Ethiopia. And that's what feeds the summer flood of the Nile in Egypt that was so critical to agriculture.”

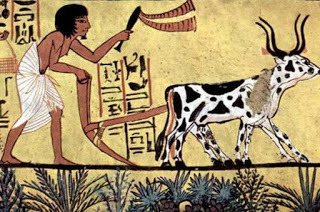

Burial chamber of Sennedjem, Scene: Plowing farmer. (Public Domain)

Science Alert reports that the researchers have linked at least three major events in ancient Egypt’s declining years to volcanic eruptions and the subsequent suppression of the Nile. An eruption in 245 BC has been used as a partial explanation for Ptolemy III's exit from the area now Syria and Iraq, as the Roman historian Justinus wrote, if Ptolemy III “had not been recalled to Egypt by disturbances at home, [he] would have made himself master of all Seleucus's dominions.”

The 20-year Theban revolt (starting in 207 BC) has been connected to another volcanic eruption. And finally, eruptions during the reign of Cleopatra VII in 46 and 44 BC led to serious famines and the release of state-reserved grain. This may have been the so-called “straw that broke the camel’s back” – climatic, social, political, and economic upheaval combined and brought down the famous ancient Egyptian civilization.

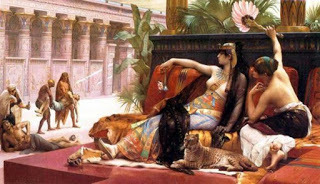

Cleopatra Testing Poisons on Condemned Prisoners by Alexandre Cabanel (1887). (Public Domain)

Ludlow says that the connection between the eruptions, Nile failure, and problematic events in Egypt are “highly unlikely to have occurred by chance, such is the level of overlap.”

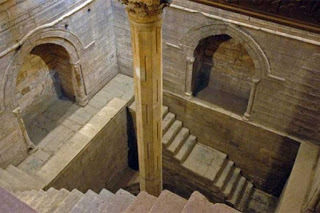

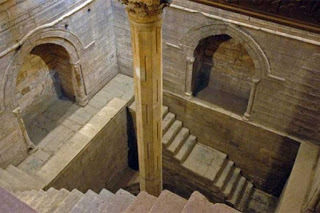

The historians determined the impact of the eruptions on the Nile and Egyptian society by examining a monument known as al-Miqyas, or the Nilometer, which has preserved a record of the Nile's summer peaks since the early 7th century. They combined that data with events prior to that time by piecing together information from previous research providing a timeline of major volcanic eruptions around the world and historical records

Measuring shaft of the Nilometer on Rhoda Island, Cairo. Nilometers measured how high or low the flood would be. (CC BY SA 3.0)

Yale University researcher Joseph Manning told EurekAlert! “That's the beauty of these climate records. For the first time, you can actually see a dynamic society in Egypt, not just a static description of a bunch of texts in chronological order.

The Nile River from a boat between Luxor and Aswan. (Public Domain)

But this is not just a story of past issues, the researchers stressed to EurekAlert! that we should take note. Ludlow says:

“The 21st century has been lacking in explosive eruptions of the kind that can severely affect monsoon patterns. But that could change at any time. The potential for this needs to be taken into account in trying to agree on how the valuable waters of the Blue Nile are going to be managed between Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt.”

This study is part of the Volcanic Impacts on Climate and Society working group of Past Global Changes (PAGES), a global research project of Future Earth.

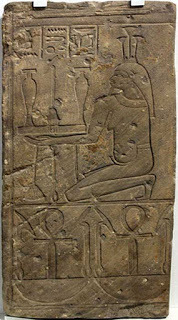

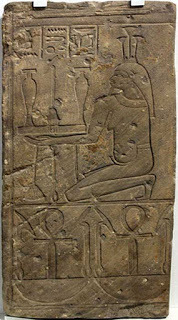

Fragment of a temple relief with Nile god Hapi. The inscription on the frieze reads "all luck, all life" which is what was hoped for; Medinet (Egypt); 746-655 BC. (Public Domain)

Top Image: Artist’s depiction of an Ancient Egyptian girl kneeling by the Nile River. Source: Ann Wuyts/ CC BY 2.0

By Alicia McDermott

The Nile river was the lifeblood of ancient Egypt. When the waterway flooded nearby lands things were good, but a lack of that precious water caused serious issues. Now, historians have found that the famous waterway could have been negatively impacted at key moments in the Ptolemaic period – inciting social, political, and economic upheavals. Most surprisingly, it seems that the lack of Nile flooding could have been set off by volcanic eruptions altering the climate.

The results of research on the link between the climatic impact in ancient Egypt by volcanoes was recently published in Nature Communications. In the paper, the authors explain that “Explosive eruptions can perturb climate by injecting sulfurous gases into the stratosphere; these gases react to form reflective sulfate aerosols that remain aloft in decreasing concentrations for approximately one to two years.” Through a chain of events, those sulfurous gases cool the atmosphere, and if that takes place in the Northern Hemisphere, monsoon rains may not move as far as they usually do.

Merapi volcano, eruption at night. (1865) Raden Saleh. (Public Domain)

Francis Ludlow, a climate historian at Trinity College in Dublin and a co-author of the study, explained to EurekAlert! how those climatic events impacted the Nile River, “When the monsoon rains don't move far enough north, you don't have as much rain falling over Ethiopia. And that's what feeds the summer flood of the Nile in Egypt that was so critical to agriculture.”

Burial chamber of Sennedjem, Scene: Plowing farmer. (Public Domain)

Science Alert reports that the researchers have linked at least three major events in ancient Egypt’s declining years to volcanic eruptions and the subsequent suppression of the Nile. An eruption in 245 BC has been used as a partial explanation for Ptolemy III's exit from the area now Syria and Iraq, as the Roman historian Justinus wrote, if Ptolemy III “had not been recalled to Egypt by disturbances at home, [he] would have made himself master of all Seleucus's dominions.”

The 20-year Theban revolt (starting in 207 BC) has been connected to another volcanic eruption. And finally, eruptions during the reign of Cleopatra VII in 46 and 44 BC led to serious famines and the release of state-reserved grain. This may have been the so-called “straw that broke the camel’s back” – climatic, social, political, and economic upheaval combined and brought down the famous ancient Egyptian civilization.

Cleopatra Testing Poisons on Condemned Prisoners by Alexandre Cabanel (1887). (Public Domain)

Ludlow says that the connection between the eruptions, Nile failure, and problematic events in Egypt are “highly unlikely to have occurred by chance, such is the level of overlap.”

The historians determined the impact of the eruptions on the Nile and Egyptian society by examining a monument known as al-Miqyas, or the Nilometer, which has preserved a record of the Nile's summer peaks since the early 7th century. They combined that data with events prior to that time by piecing together information from previous research providing a timeline of major volcanic eruptions around the world and historical records

Measuring shaft of the Nilometer on Rhoda Island, Cairo. Nilometers measured how high or low the flood would be. (CC BY SA 3.0)

Yale University researcher Joseph Manning told EurekAlert! “That's the beauty of these climate records. For the first time, you can actually see a dynamic society in Egypt, not just a static description of a bunch of texts in chronological order.

The Nile River from a boat between Luxor and Aswan. (Public Domain)

But this is not just a story of past issues, the researchers stressed to EurekAlert! that we should take note. Ludlow says:

“The 21st century has been lacking in explosive eruptions of the kind that can severely affect monsoon patterns. But that could change at any time. The potential for this needs to be taken into account in trying to agree on how the valuable waters of the Blue Nile are going to be managed between Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt.”

This study is part of the Volcanic Impacts on Climate and Society working group of Past Global Changes (PAGES), a global research project of Future Earth.

Fragment of a temple relief with Nile god Hapi. The inscription on the frieze reads "all luck, all life" which is what was hoped for; Medinet (Egypt); 746-655 BC. (Public Domain)

Top Image: Artist’s depiction of an Ancient Egyptian girl kneeling by the Nile River. Source: Ann Wuyts/ CC BY 2.0

By Alicia McDermott

Published on October 27, 2017 00:30

October 26, 2017

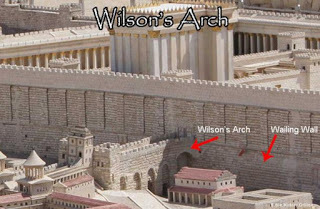

1800-Year-Old Roman Era Theater Found at Jerusalem’s Western Wall

Ancient Origins

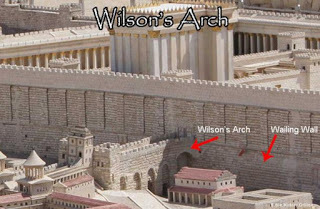

What seems to be a long-lost ancient Roman Theater has been unearthed next to Jerusalem's Western Wall. The archaeological dig under Wilson’s Arch also revealed eight previously unknown layers of Western Wall stones.

Roman Amphitheater

Hidden for More than 1,700 Years A team of Israeli archaeologists have unearthed what they speculate may have been an ancient Roman amphitheater that hasn't seen the light of day in more than 1,700 years as Phys Org reported. Excavations by the Israel Antiquities Authority are currently taking place underneath Wilson's Arch, which stands next to the holy site in the heart of the Old City. Wilson’s Arch, built of immense stones, is the last of a series of such arches that

Wilson's Arch, gives entry to the Temple Mount on the western section of the plaza. (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The team was hoping to find artifacts that would help them date Wilson's Arch, but during the dig they unexpectedly came across the buried theater. "The discovery was a real surprise," site excavators Joe Uziel, Tehillah Lieberman and Avi Solomon said in a statement. "We did not imagine that a window would open for us onto the mystery of Jerusalem's lost theater. What's very exciting about this amazing structure is that we totally didn't expect to find it here," Uziel told CNN.

Dr. Joe Uziel, Excavation Director, standing on steps of the amphitheater (Image: Israel Antiquities)

Theater-Like Structure Couldn’t Have Held More than 200 People

“This is a relatively small structure compared to known Roman theaters (such as at Caesarea, Bet She’an and Bet Guvrin). This fact, in addition to its location under a roofed space – in this case under Wilson’s Arch – leads us to suggest that this is a theater-like structure of the type known in the Roman world as an odeon. In most cases, such structures were used for acoustic performances. Alternatively, this may have been a structure known as a bouleuterion – the building where the city council met, in this case the council of the Roman colony of Aelia Capitolina – Roman Jerusalem,” the archaeologist said as CNN reported. “It’s probably the most important archaeological site in the country, the first public structure from the Roman period of Jerusalem,” Yuval Baruch, chief Jerusalem architect at the Israel Antiquities Authority, told AFP. "It's a theater-like structure that held 200 people," he added.

Archaeologist Tehillah Lieberman on unfinished steps (Image: Israel Antiquities)

The Amphitheater Wasn't Completed

However, it's unlikely that performers or politicians ever used the amphitheater. Several signs, such as an uncut staircase and unfinished carvings, suggest that it was abandoned before its inaugural performance. It's not yet clear why the amphitheater wasn't completed, but it's possible that the Bar Kokhba Revolt, when the Jews rebelled against the Romans, had something to do with the theater's unfinished circumstances, the archaeologists suggest. Perhaps construction began before the revolt, but was abandoned once the revolt started.

Other unfinished buildings from this period have been found in the Western Wall Plaza, the archaeologists added. "This is indeed one of the most important findings in all my 30 years at the Western Wall Heritage Foundation," Mordechai (Suli) Eliav, the director of the Western Wall Heritage Foundation, said in a statement. And added, "This discovery joins many other findings uncovered in the area of the Western Wall Plaza, which together create a living historical mosaic of Jerusalem and the Western Wall for which the generations longed so powerfully."

Other Finds Include Pottery Vessels and Coins

Other findings under Wilson's Arch include pottery vessels and coins. During the recent excavation under the arch, archaeologists also found eight stone courses and a human-made stone layer supporting the structure above buried under 26 feet (8 meters) of dirt. Ultimately, The Jerusalem Post reports that the findings will be presented to the public during a conference called “New Studies in the Archaeology of Jerusalem and its Environs,” which will take place later this year at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem to celebrate the 50 years of archaeology since the unification of Jerusalem.

Top image: Theater-like structure found at the Western Wall Tunnels, Jerusalem (Image: Israel Antiquities)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

What seems to be a long-lost ancient Roman Theater has been unearthed next to Jerusalem's Western Wall. The archaeological dig under Wilson’s Arch also revealed eight previously unknown layers of Western Wall stones.

Roman Amphitheater

Hidden for More than 1,700 Years A team of Israeli archaeologists have unearthed what they speculate may have been an ancient Roman amphitheater that hasn't seen the light of day in more than 1,700 years as Phys Org reported. Excavations by the Israel Antiquities Authority are currently taking place underneath Wilson's Arch, which stands next to the holy site in the heart of the Old City. Wilson’s Arch, built of immense stones, is the last of a series of such arches that

Wilson's Arch, gives entry to the Temple Mount on the western section of the plaza. (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The team was hoping to find artifacts that would help them date Wilson's Arch, but during the dig they unexpectedly came across the buried theater. "The discovery was a real surprise," site excavators Joe Uziel, Tehillah Lieberman and Avi Solomon said in a statement. "We did not imagine that a window would open for us onto the mystery of Jerusalem's lost theater. What's very exciting about this amazing structure is that we totally didn't expect to find it here," Uziel told CNN.

Dr. Joe Uziel, Excavation Director, standing on steps of the amphitheater (Image: Israel Antiquities)

Theater-Like Structure Couldn’t Have Held More than 200 People

“This is a relatively small structure compared to known Roman theaters (such as at Caesarea, Bet She’an and Bet Guvrin). This fact, in addition to its location under a roofed space – in this case under Wilson’s Arch – leads us to suggest that this is a theater-like structure of the type known in the Roman world as an odeon. In most cases, such structures were used for acoustic performances. Alternatively, this may have been a structure known as a bouleuterion – the building where the city council met, in this case the council of the Roman colony of Aelia Capitolina – Roman Jerusalem,” the archaeologist said as CNN reported. “It’s probably the most important archaeological site in the country, the first public structure from the Roman period of Jerusalem,” Yuval Baruch, chief Jerusalem architect at the Israel Antiquities Authority, told AFP. "It's a theater-like structure that held 200 people," he added.

Archaeologist Tehillah Lieberman on unfinished steps (Image: Israel Antiquities)

The Amphitheater Wasn't Completed

However, it's unlikely that performers or politicians ever used the amphitheater. Several signs, such as an uncut staircase and unfinished carvings, suggest that it was abandoned before its inaugural performance. It's not yet clear why the amphitheater wasn't completed, but it's possible that the Bar Kokhba Revolt, when the Jews rebelled against the Romans, had something to do with the theater's unfinished circumstances, the archaeologists suggest. Perhaps construction began before the revolt, but was abandoned once the revolt started.

Other unfinished buildings from this period have been found in the Western Wall Plaza, the archaeologists added. "This is indeed one of the most important findings in all my 30 years at the Western Wall Heritage Foundation," Mordechai (Suli) Eliav, the director of the Western Wall Heritage Foundation, said in a statement. And added, "This discovery joins many other findings uncovered in the area of the Western Wall Plaza, which together create a living historical mosaic of Jerusalem and the Western Wall for which the generations longed so powerfully."

Other Finds Include Pottery Vessels and Coins

Other findings under Wilson's Arch include pottery vessels and coins. During the recent excavation under the arch, archaeologists also found eight stone courses and a human-made stone layer supporting the structure above buried under 26 feet (8 meters) of dirt. Ultimately, The Jerusalem Post reports that the findings will be presented to the public during a conference called “New Studies in the Archaeology of Jerusalem and its Environs,” which will take place later this year at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem to celebrate the 50 years of archaeology since the unification of Jerusalem.

Top image: Theater-like structure found at the Western Wall Tunnels, Jerusalem (Image: Israel Antiquities)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on October 26, 2017 00:00

October 24, 2017

900-Year-Old German Monastery Forced to Shut Down Because of Monk Shortage

Ancient Origins

Himmerod Abbey, a Cistercian monastery that's existed for almost 900 years in what is now western Germany is closing down for good, due to running expenses and also a shortage of monks. Notably, the monastery was used during the 1950’s in a distinctly non-monastic capacity, as a secret meeting point of former Wehrmacht high-ranking officers discussing West Germany's rearmament.

Closure After 883 Years of Operation

Himmerod Abbey is a Cistercian monastery in western Germany that was founded in 1134 by French Abbot Bernhard of Clairvaux. After coming back from the brink of bankruptcy six years ago, the monastery now has to shut its doors permanently as DW reports. There are only six monks currently living in the abbey compared to the thirty residing there almost forty years ago.

Himmerod Monastery Church (CC BY 2.0)

In 1922 the monastery was re-founded by the settlement of German Cistercian monks from the former monastery of Mariastern in modern-day Bosnia. The church building was reconstructed under Abbot Vitus Recke (Abbot from 1937 to 1959), and completed in 1962. The abbey today has a museum, a book - and art shop, a café, a guesthouse and retreat-house, as well as a fishery. Its highlight, however, is its own publishing house, the Himmerod Drucke, which has published over 50 works by a number of authors, especially Father Stephan Reimund Senge, a monk at Himmerod. The journal Unsere Liebe Frau von Himmerod ("Our Lady of Himmerod") appears three times a year, and the newsletter Himmeroder Rundbrief edited by Father Stephan, about ten times a year.

Himmerod Abbey by Fritz von Wille, pre-1941, church ruins before reconstruction (Public Domain)

The Infamous Himmerod Memorandum

The Himmerod memorandum was a 40-page document produced following a 1950 secret meeting of former Wehrmacht high-ranking officers invited by Chancellor Konrad Adenauer to the Himmerod Abbey to discuss West Germany's rearmament. The resulting document laid foundation for the establishment of the new army – Bundeswehr – of the Federal Republic.

The memorandum, along with the public declaration of Wehrmacht's "honor" by the Allied military commanders and West Germany's politicians, contributed to the creation of the myth of the "clean Wehrmacht.”

From 5 to 9 October 1950, a group of former senior officers, at the behest of Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, met in secret at the Himmerod Abbey, from where the memorandum took its name, to discuss West Germany's rearmament. The participants were divided in several subcommittees that focused on the political, ethical, operational and logistical aspects of the future armed forces.

The resulting memorandum included a summary of the discussions at the conference and bore the name "Memorandum on the Formation of a German Contingent for the Defense of Western Europe within the framework of an International Fighting Force". It was intended as both a planning document and as a basis of negotiations with the Western Allies. The participants of the conference were convinced that no future German army would be possible without the historical rehabilitation of the Wehrmacht.

Himmerod Church interior (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Uncertain Future

The monastery’s property, near the village of Grosslittgen, will be transferred to the Catholic diocese of Trier, while the six monks will move to other monasteries. The Catholic diocese of Trier has yet to announce what it plans to do with the site. Additionally, it is not yet clear what will happen to the monastery's other staff. "Himmerod will remain a spiritual site,” head of the monastery, Abbot Johannes, said as DW reports. “The walls have retained this history. I am telling you: There is no way to destroy this spiritual place, which has attracted people for centuries. I am certain people will continue to come here," he added.

The Cistercian order was founded in 1098 in response to a perceived abandonment of humility by the leading order of the time. Cistercian monasteries are divided into those that follow the Common Observance, the Middle Observance and the Strict Observance also known as Trappists. Despite the latest closure, there are still more than 160 Trappist monasteries in the world, with over 2,000 Trappist monks and roughly 1800 Trappist nuns.

Himmerod Abbey church (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Top image: Himmerod Abbey and Church building (Public Domain)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on October 24, 2017 23:30