MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 43

October 4, 2017

Archaeologists Announce that New Discoveries Solve Mystery of How the Great Pyramid Was Built

Ancient Origins

A new set of investigations in ancient Egypt have led to some startling discoveries – the translation of an ancient papyrus, the unearthing of an ingenious system of waterworks, and the discovery of a 4,500-year-old ceremonial boat – may be the final pieces to the millennia-old puzzle of how the Great Pyramid of Egypt was really built.

Archaeologists have reported their incredible new findings to Mail Online, which will be reported in full in tonight’s Channel 4 documentary ‘Egypt’s Great Pyramid: The New Evidence’ in the United Kingdom.

Despite centuries of research into the pyramids of Giza, there has still been no definitive explanation as to how the ancient Egyptians cut, transported, and assembled millions of limestone and granite blocks, each weighing an average of 2.3 metric tons. “For the construction of the pyramids, there is no single theory that is 100% proven or checked; They are all theories and hypotheses,” said Hany Helal, Vice President of the Heritage Innovation Preservation institute.

The Great Pyramid of Giza. Credit: BigStockPhoto

How Were the Stone Blocks Transported?

It has long been established that the limestone was quarried in Tura about eight miles away, while the granite used in the interior of the Great Pyramid was quarried 533 miles away in Aswan. However, archaeologists have not been able to determine how the stones were transported to Giza for the construction of the pyramid of Khufu. A study in April, 2014, claimed to have solved part of the puzzle – ancient Egyptians moved massive stone blocks across the desert by wetting the sand in front of a contraption built to pull the heavy objects. But three separate discoveries in the last few years are now painting a different picture.

New Evidence Reveals Blocks Arrived by Boat

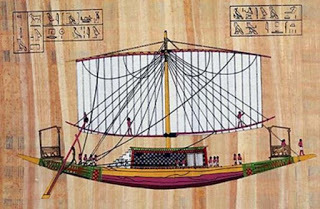

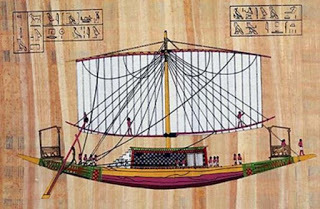

The discovery of an ancient papyrus in a cave at the ancient Red Sea port of Wadi el-Jarf, the unearthing of a lost waterway beneath the Giza plateau and the finding of a ceremonial boat, now strongly suggests that thousands of laborers transported 170,000 tons of limestone along the Nile River Nile wooden boats.

An Ancient Egyptian Boat. Credit: Canadian Museum of History

The Diary of a Pyramid Builder

The 4,500-year-old papyrus found at Wadi el-Jarf offers a significant insight into the construction of the pyramids. Written by Merer, an overseer in charge of a large team of elite workers, the ancient logbook from the 27th year of the reign of the pharaoh Khufu, described in detail the construction of the Great Pyramid.

“The hieroglyphic letters … detailed over the course of several months the construction operations for the Great Pyramid, which was nearing completion, and the work at the limestone quarries at Tura on the opposite bank of the Nile River,” reports History.com. “Merer’s logbook, written in a two-column daily timetable, reports on the daily lives of the construction workers and notes that the limestone blocks exhumed at Tura, which were used to cover the pyramid’s exterior, were transported by boat along the Nile River and a system of canals to the construction site, a journey that took between two and three days.”

Remnants of an Ancient System of Canals

If this account is accurate, where are the canals that Merer speaks of? Until recently, there was little evidence of such a system of waterworks that could have been used to transport the giant blocks. However, archaeologist Mark Lehner has now revealed the discovery of a lost waterway beneath the Giza plateau. “We’ve outlined the central canal basin which we think was the primary delivery area to the foot of the Giza Plateau,” he told Mail Online.

Transport Vessels Found

Seven boat pits have been found in the area around Khufu’s pyramid, two on the south side, two on the east side, two in between the queens’ pyramids and one located beside the mortuary temple and causeway. In addition, archaeologists have found ceremonial boats, which reveal in detail how the ships were constructed, and detailed relief carvings of hundreds of transport vessels.

3,800-year-old relief carving in Egypt depicts over 100 boats. Credit: Josef Wegner.

The details of these new discoveries are being broadcast for the first time in ‘Egypt’s Great Pyramid: The New Evidence’ being aired tonight on Channel 4 at 8pm BST.

Top image: Great Pyramid of Egypt. Source: BigStockPhoto

By April Holloway

A new set of investigations in ancient Egypt have led to some startling discoveries – the translation of an ancient papyrus, the unearthing of an ingenious system of waterworks, and the discovery of a 4,500-year-old ceremonial boat – may be the final pieces to the millennia-old puzzle of how the Great Pyramid of Egypt was really built.

Archaeologists have reported their incredible new findings to Mail Online, which will be reported in full in tonight’s Channel 4 documentary ‘Egypt’s Great Pyramid: The New Evidence’ in the United Kingdom.

Despite centuries of research into the pyramids of Giza, there has still been no definitive explanation as to how the ancient Egyptians cut, transported, and assembled millions of limestone and granite blocks, each weighing an average of 2.3 metric tons. “For the construction of the pyramids, there is no single theory that is 100% proven or checked; They are all theories and hypotheses,” said Hany Helal, Vice President of the Heritage Innovation Preservation institute.

The Great Pyramid of Giza. Credit: BigStockPhoto

How Were the Stone Blocks Transported?

It has long been established that the limestone was quarried in Tura about eight miles away, while the granite used in the interior of the Great Pyramid was quarried 533 miles away in Aswan. However, archaeologists have not been able to determine how the stones were transported to Giza for the construction of the pyramid of Khufu. A study in April, 2014, claimed to have solved part of the puzzle – ancient Egyptians moved massive stone blocks across the desert by wetting the sand in front of a contraption built to pull the heavy objects. But three separate discoveries in the last few years are now painting a different picture.

New Evidence Reveals Blocks Arrived by Boat

The discovery of an ancient papyrus in a cave at the ancient Red Sea port of Wadi el-Jarf, the unearthing of a lost waterway beneath the Giza plateau and the finding of a ceremonial boat, now strongly suggests that thousands of laborers transported 170,000 tons of limestone along the Nile River Nile wooden boats.

An Ancient Egyptian Boat. Credit: Canadian Museum of History

The Diary of a Pyramid Builder

The 4,500-year-old papyrus found at Wadi el-Jarf offers a significant insight into the construction of the pyramids. Written by Merer, an overseer in charge of a large team of elite workers, the ancient logbook from the 27th year of the reign of the pharaoh Khufu, described in detail the construction of the Great Pyramid.

“The hieroglyphic letters … detailed over the course of several months the construction operations for the Great Pyramid, which was nearing completion, and the work at the limestone quarries at Tura on the opposite bank of the Nile River,” reports History.com. “Merer’s logbook, written in a two-column daily timetable, reports on the daily lives of the construction workers and notes that the limestone blocks exhumed at Tura, which were used to cover the pyramid’s exterior, were transported by boat along the Nile River and a system of canals to the construction site, a journey that took between two and three days.”

Remnants of an Ancient System of Canals

If this account is accurate, where are the canals that Merer speaks of? Until recently, there was little evidence of such a system of waterworks that could have been used to transport the giant blocks. However, archaeologist Mark Lehner has now revealed the discovery of a lost waterway beneath the Giza plateau. “We’ve outlined the central canal basin which we think was the primary delivery area to the foot of the Giza Plateau,” he told Mail Online.

Transport Vessels Found

Seven boat pits have been found in the area around Khufu’s pyramid, two on the south side, two on the east side, two in between the queens’ pyramids and one located beside the mortuary temple and causeway. In addition, archaeologists have found ceremonial boats, which reveal in detail how the ships were constructed, and detailed relief carvings of hundreds of transport vessels.

3,800-year-old relief carving in Egypt depicts over 100 boats. Credit: Josef Wegner.

The details of these new discoveries are being broadcast for the first time in ‘Egypt’s Great Pyramid: The New Evidence’ being aired tonight on Channel 4 at 8pm BST.

Top image: Great Pyramid of Egypt. Source: BigStockPhoto

By April Holloway

Published on October 04, 2017 00:30

October 3, 2017

1,000-year-old Viking Boat Burial Discovered Under Market Square in Norway

Ancient Origins

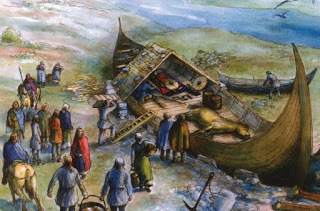

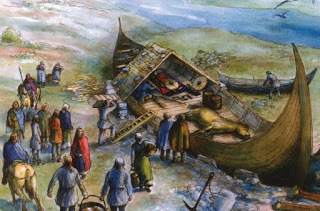

A millennium-old Viking boat grave with bones and sheet bronze still inside has been discovered under a market square in Norway. The grave was found during one of the final days of excavations by the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) in the Norwegian city of Trondheim.

Viking Ship Grave Found in Norway

A team of archaeologists excavating in Norway, have unearthed a 1,000-year-old Viking boat burial measuring more than 4 meters (13 feet). The tomb was found during excavations beneath the market square of the Norwegian city of Trondheim as Live Science reported. While none of the vessel's wood remains, preserved lumps of rust and nails indicate a boat was buried at the site between the 7th and 10th centuries AD. “Careful excavation works revealed that no wood remained intact, but lumps of rust and some poorly-preserved nails indicated that it was a boat that was buried here,” archaeologist Ian Reed told NIKU.

The Viking boat is in a poor state of preservation. Credit: Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU)

The Importance of Ships in Viking Society

Many historians suggest that the Viking ship was one of the greatest technical and artistic achievements of the European dark ages. These fast ships had the strength to survive ocean crossings while having a draft of as little as 50cm (20 inches), allowing navigation in very shallow water. Ships were an important part of Viking society, not only as a means of transportation, but also for the prestige that it conferred on her owner and skipper. That’s why if a high-born clansman did not die at sea he would be buried in a ship on land, often with weapons and pottery.

Viking ships were used for trade, raids and cononization. (public domain)

The Tradition of Viking Boat Burials

Burial of ships is an ancient tradition in Scandinavia, stretching back to at least the Nordic Iron Age, as evidenced by the Hjortspring boat (400-300 BC) or the Nydam boats (200-450 AD), for example. Ships and bodies of water have held a major spiritual importance in the Norse cultures since at least the Nordic Bronze Age. The newly uncovered grave, which pointed north to south, was found with two long bones inside. Like the boat, these bones were oriented north to south, and experts will now perform DNA analysis to confirm that they are human.

Inner view of oak made Nydam-boat. (CC by SA 3.0)

Findings Include Sheet Bronze and a Piece of a Spoon

Other finds included a small piece of sheet bronze propped against one of the bones, as well as what appear to be personal items from the grave. Interestingly, in a pothole dug through the middle of the boat, the team found a piece of a spoon. “We also found a key to a small box in the grave,” team member Julian Cadamarteri told Norwegian daily Adresseavisen. And added, “If it originates from the grave, it [the site] is likely to date from anywhere between the 600s and the 900s.”

Could it be an Åfjord boat?

Åfjord, a municipality in Sør-Trøndelag County in Norway, is mainly known for its distinctive wooden boats that were dragged over this thin peninsula in order to shorten the journey and to avoid risking them in bad weather.

Archaeologists speculate that the newly discovered boat could be an Åfjord boat, which has historically been a common sight along the Trøndelag coast as Knut Paasche, a specialist in early boats, suggests. “It is likely a boat that has been dug down into the ground and been used as a coffin for the dead. There has also probably been a burial mound over the boat and grave,” he tells NIKU. And continues, “This is another discovery by NIKU that refers to a Trondheim older than the medieval city. Other Viking settlements such as Birka, Gokstad or Kaupang, all have graves in close proximity to the trading centre,” pointing out that this is the first time a ship burial from the Iron Age and into the Viking Period been discovered in Trondheim city center. The archaeological investigations are financed by the municipality of Trondheim and the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage.

Top image: An Illustration of a Viking boat burial. Credit: Avaldsnes

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A millennium-old Viking boat grave with bones and sheet bronze still inside has been discovered under a market square in Norway. The grave was found during one of the final days of excavations by the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) in the Norwegian city of Trondheim.

Viking Ship Grave Found in Norway

A team of archaeologists excavating in Norway, have unearthed a 1,000-year-old Viking boat burial measuring more than 4 meters (13 feet). The tomb was found during excavations beneath the market square of the Norwegian city of Trondheim as Live Science reported. While none of the vessel's wood remains, preserved lumps of rust and nails indicate a boat was buried at the site between the 7th and 10th centuries AD. “Careful excavation works revealed that no wood remained intact, but lumps of rust and some poorly-preserved nails indicated that it was a boat that was buried here,” archaeologist Ian Reed told NIKU.

The Viking boat is in a poor state of preservation. Credit: Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU)

The Importance of Ships in Viking Society

Many historians suggest that the Viking ship was one of the greatest technical and artistic achievements of the European dark ages. These fast ships had the strength to survive ocean crossings while having a draft of as little as 50cm (20 inches), allowing navigation in very shallow water. Ships were an important part of Viking society, not only as a means of transportation, but also for the prestige that it conferred on her owner and skipper. That’s why if a high-born clansman did not die at sea he would be buried in a ship on land, often with weapons and pottery.

Viking ships were used for trade, raids and cononization. (public domain)

The Tradition of Viking Boat Burials

Burial of ships is an ancient tradition in Scandinavia, stretching back to at least the Nordic Iron Age, as evidenced by the Hjortspring boat (400-300 BC) or the Nydam boats (200-450 AD), for example. Ships and bodies of water have held a major spiritual importance in the Norse cultures since at least the Nordic Bronze Age. The newly uncovered grave, which pointed north to south, was found with two long bones inside. Like the boat, these bones were oriented north to south, and experts will now perform DNA analysis to confirm that they are human.

Inner view of oak made Nydam-boat. (CC by SA 3.0)

Findings Include Sheet Bronze and a Piece of a Spoon

Other finds included a small piece of sheet bronze propped against one of the bones, as well as what appear to be personal items from the grave. Interestingly, in a pothole dug through the middle of the boat, the team found a piece of a spoon. “We also found a key to a small box in the grave,” team member Julian Cadamarteri told Norwegian daily Adresseavisen. And added, “If it originates from the grave, it [the site] is likely to date from anywhere between the 600s and the 900s.”

Could it be an Åfjord boat?

Åfjord, a municipality in Sør-Trøndelag County in Norway, is mainly known for its distinctive wooden boats that were dragged over this thin peninsula in order to shorten the journey and to avoid risking them in bad weather.

Archaeologists speculate that the newly discovered boat could be an Åfjord boat, which has historically been a common sight along the Trøndelag coast as Knut Paasche, a specialist in early boats, suggests. “It is likely a boat that has been dug down into the ground and been used as a coffin for the dead. There has also probably been a burial mound over the boat and grave,” he tells NIKU. And continues, “This is another discovery by NIKU that refers to a Trondheim older than the medieval city. Other Viking settlements such as Birka, Gokstad or Kaupang, all have graves in close proximity to the trading centre,” pointing out that this is the first time a ship burial from the Iron Age and into the Viking Period been discovered in Trondheim city center. The archaeological investigations are financed by the municipality of Trondheim and the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage.

Top image: An Illustration of a Viking boat burial. Credit: Avaldsnes

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on October 03, 2017 00:00

October 2, 2017

Sam’s historical recipe corner: Custard tart

History Extra

Custard tarts really are the food of and queens. They were served at Henry IV’s coronation in 1399 and more recently at Queen Elizabeth’s 80th birthday in 2006. In medieval times the tarts (also known as doucetes and darioles) could include pork too – dinner and pudding in one! Custard recipes go back to Roman times, but I used Marcus Wareing’s Queen’s birthday banquet version.

Ingredients

For the pastry:

• 225g flour + pinch of salt

• Zest of one lemon

• 150g butter

• 75g caster sugar

• 1 egg and 1 egg yolk

For the filling:

• 9 egg yolks

• 75g caster sugar

• 500ml whipping cream

• 2 nutmegs

Method

Preheat oven to 170°C/gas mark 3. Add salt, lemon zest and butter to the flour and mix between fingertips until it resembles breadcrumbs.

Add sugar, then the beaten egg and extra yolk, and form into a ball. Wrap in clingfilm, chill in a fridge for 1-2 hours, then roll out on a floured surface to 2mm thick.

Use to line an 18cm flan ring, placed on a baking tray, and cover with greaseproof paper and baking beans. Bake for 10 mins or until pastry starts to go golden brown. Remove, then cool. Reduce oven to 130°C/gas mark 1.

Bring the cream to the boil. In a separate bowl whisk egg yolks with sugar and mix in the cream. Fill the pastry case to the brim and grate nutmeg on top. Bake for 30–40 mins or until set. Allow to cool.

My verdict

Delicious but extremely rich. Treat yourself to a moderate slice (rather than the robust slices I ate). You’ll find that it still works well if you reduce the sugar content.

Difficulty: 3/10

Time: 120 minutes

Recipe courtesy of Great British Chefs.

Published on October 02, 2017 00:30

October 1, 2017

The Origins of the Faeries: Encoded in our Cultures

Ancient Origins

The faeries appear in folklore from all over the world as metaphysical beings, who, given the right conditions, are able to interact with the physical world. They’re known by many names but there is a conformity to what they represent, and perhaps also to their origins. From the Huldufólk in Iceland to the Tuatha Dé Danann in Ireland, and the Manitou of Native Americans, these are apparently intelligent entities that live unseen beside us, until their occasional manifestations in this world become encoded into our cultures through folktales, anecdotes and testimonies.

Middle-Earth-like elves by artist (Araniart/CC BY 3.0)

In his 1691 treatise on the faeries of Aberfoyle, Scotland, the Reverend Robert Kirk suggested they represented a Secret Commonwealth, living in a parallel reality to ours, with a civilization and morals of their own, only visible to seers and clairvoyants. His assessment fits well with both folktale motifs, and some modern theories about their ancient origins and how they have permeated the collective human consciousness. So who are the faeries, where do they come from…and what do they want?

Faerie-tales

“Myth is a story that implies a certain way of interpreting consensus reality so to derive meaning and effective charge from its images and interactions. As such, it can take many forms: fables, religion and folklore, but also formal philosophical systems and scientific theories.” -

Bernardo Kastrup, More Than Allegory: On religious myth, truth and belief (2016)

Faerie-tales are a type of mythology; explanations of human and environmental phenomena, usually set at an indeterminate time in the past. Most faerie-tales are never one-offs, but seem to cluster as a single form from many sources, which are dispersed geographically and chronologically. In Europe and America, they were mostly collected by folklorists in the 19th and early-20th centuries, from both oral and written sources, and then disseminated from there. Many were incorporated into the folklorists’ bible, the Aarne-Thompson catalogues of folktale types and motifs, which were first put together in 1910 by the Finnish folklorist Antti Aarne, and completed by Stith Thompson in 1958. They consist of several doorstop volumes, which index every conceivable story type and motif from around the world.

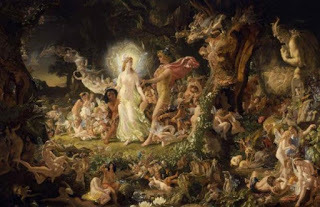

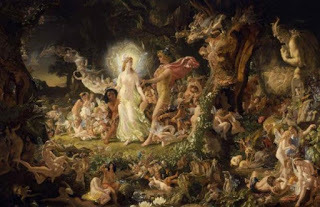

‘The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania’ by Noel Paton (Public Domain)

It’s been suggested that the catalogues actually codify every human experience, distilled into story; an index of our collective memory as a species, realized through the medium of mythology. Amidst the catalogues are the story types classed as faerie-tales, each containing hundreds of separate motifs; they are the descriptors of a vast array of myth. These are not simple tales told to pass the long winter nights (although that was always one use for them), but rather, they are sophisticated tools that can be used to interpret human experience and to help understand the reality we find ourselves in.

One common faerie-tale motif, for instance, is the suspension of time when a mortal visits faerieland. A nice example is the Irish story of Oisín, a poet of the Feinn. After falling asleep under an ash tree he awakes to find Niamh, the shape-shifting Queen of Tir na n’Og, the land of perpetual youth, summoning him to join her in her realm as her husband. He agrees and finds himself living in a paradise of perpetual summer, where all good things abound, and where time and death hold no sway.

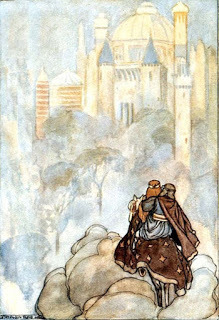

Oisín and Niamh travelling to Tír na nÓg. (Public Domain)

But soon he breaks a taboo of standing on a broad flat stone, from where he is able to view the Ireland he left behind. It has changed for the worse, and he begs Niamh to give him leave to return. She reluctantly agrees, but asks that he return after only one day with the mortals. She supplies him with a black horse, which he is not to dismount, and ‘gifted him with wisdom and knowledge far surpassing that of men.’ Once back in Ireland he realizes that decades have passed and that he is no longer recognized or known of. Inevitably, he dismounts his horse and immediately his youth is gone and he becomes an enfeebled old man with nothing but his immortal wisdom. There is no returning to the faerieland of the Tir na n’Og. In other variations of the story, the hero turns to dust as soon as his feet touch the ground of consensus reality.

The faeries as elementals (Courtesy author)

This important and widespread folktale motif seems to suggest that faerieland is the world of the dead, immune from the passage of time, and that return to the world of the living is not possible as the mortal body has aged and decayed in line with the physical laws of this world. In the Japanese tale of Urashima Taro, the hero, when returning home, is even given a casket by his faerie bride, in which his years are locked. When he opens it, his time is up. These stories articulate a belief in an otherworld that is never heaven, but is apparently ruled over by a race of immortals who can exert control over the consciousness of an individual, who may believe themselves to still be in human form, but are actually already dead and existing in non-material form. It is ultimately the place where the faeries come from; a place untouched by the passage of time and physical death. It could even represent the collective consciousness of humanity made into an understandable form in the stories, immortal in nature and containing all wisdom and knowledge, as suggested in the Oisín tale.

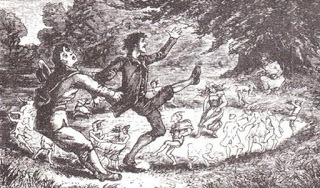

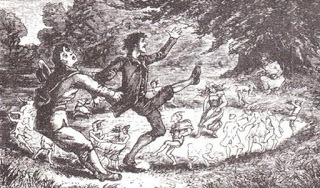

19th-century woodcut demonstrating the dangers of entering the faerie ring. (Public Domain)

This might be explained by seeing folktales of this type as representing a surviving pagan belief system of the afterlife. This afterlife did not follow the strictures of Christianity or other world religions, and provided an alternative view of what happens to consciousness after death. It is a view that was (in the West) superseded by Christian theology, but that may be surfacing in these folktales as remnants of the previous system of belief (a belief system that remained partially intact but operated underground for fear of religious persecution). The presence of faeries in this otherworld, and their ability to materialize in standard reality, suggests that they were an essential element in pagan ideas about consciousness and that they had a role to play when it came to death. In this theory the characters in the story play the part of messengers, telling us about the true nature of a timeless reality that is distinct and separate from consensus reality, and showing us that human consciousness disassociates from the physical body to exist in a parallel reality such as Tir na n’Og, where the faeries are in charge. This message is encoded in the stories.

Real Faeries and Shaman Spirits

However, it’s not possible to reduce the origin of the faeries only to abstract mythological themes. Their appearance in folklore often takes the form of witness testimonies or anecdotes, continuing to the present day. They take a myriad of different forms— leprechauns, sylphs, brownies, pixies, even aliens in a technologically updated version of their form— but they are portrayed as real entities, making appearances in this world from their own.

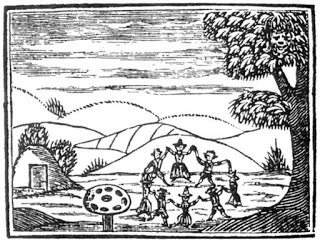

17th-century English woodcut showing faeries dancing in a ring, with hollow hill, amanita muscaria mushroom and 'spirit face' in the tree. (Public Domain)

They lure people into their magical dancing rings, abduct children and adults, play tricks on the unwary, process in faerie funeral corteges, and generally disport themselves with a sense of mischievous, and sometimes malevolent, immorality. There are countless descriptions of their metaphysical presence in our world, throughout time, playing a part in human culture, always liminal, but constantly present as far back as folklore stretches.

Neil Rushton is an archaeologist and freelance writer who has published on a wide variety of topics from castle fortifications to folklore. His first book is Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun.

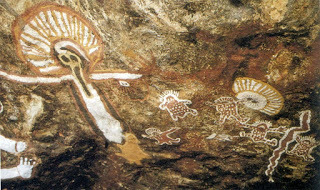

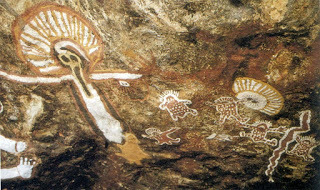

Top Image: Cave painting from Kimberley, Australia, c.10,000 BCE (Public Domain)

By Neil Rushton

The faeries appear in folklore from all over the world as metaphysical beings, who, given the right conditions, are able to interact with the physical world. They’re known by many names but there is a conformity to what they represent, and perhaps also to their origins. From the Huldufólk in Iceland to the Tuatha Dé Danann in Ireland, and the Manitou of Native Americans, these are apparently intelligent entities that live unseen beside us, until their occasional manifestations in this world become encoded into our cultures through folktales, anecdotes and testimonies.

Middle-Earth-like elves by artist (Araniart/CC BY 3.0)

In his 1691 treatise on the faeries of Aberfoyle, Scotland, the Reverend Robert Kirk suggested they represented a Secret Commonwealth, living in a parallel reality to ours, with a civilization and morals of their own, only visible to seers and clairvoyants. His assessment fits well with both folktale motifs, and some modern theories about their ancient origins and how they have permeated the collective human consciousness. So who are the faeries, where do they come from…and what do they want?

Faerie-tales

“Myth is a story that implies a certain way of interpreting consensus reality so to derive meaning and effective charge from its images and interactions. As such, it can take many forms: fables, religion and folklore, but also formal philosophical systems and scientific theories.” -

Bernardo Kastrup, More Than Allegory: On religious myth, truth and belief (2016)

Faerie-tales are a type of mythology; explanations of human and environmental phenomena, usually set at an indeterminate time in the past. Most faerie-tales are never one-offs, but seem to cluster as a single form from many sources, which are dispersed geographically and chronologically. In Europe and America, they were mostly collected by folklorists in the 19th and early-20th centuries, from both oral and written sources, and then disseminated from there. Many were incorporated into the folklorists’ bible, the Aarne-Thompson catalogues of folktale types and motifs, which were first put together in 1910 by the Finnish folklorist Antti Aarne, and completed by Stith Thompson in 1958. They consist of several doorstop volumes, which index every conceivable story type and motif from around the world.

‘The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania’ by Noel Paton (Public Domain)

It’s been suggested that the catalogues actually codify every human experience, distilled into story; an index of our collective memory as a species, realized through the medium of mythology. Amidst the catalogues are the story types classed as faerie-tales, each containing hundreds of separate motifs; they are the descriptors of a vast array of myth. These are not simple tales told to pass the long winter nights (although that was always one use for them), but rather, they are sophisticated tools that can be used to interpret human experience and to help understand the reality we find ourselves in.

One common faerie-tale motif, for instance, is the suspension of time when a mortal visits faerieland. A nice example is the Irish story of Oisín, a poet of the Feinn. After falling asleep under an ash tree he awakes to find Niamh, the shape-shifting Queen of Tir na n’Og, the land of perpetual youth, summoning him to join her in her realm as her husband. He agrees and finds himself living in a paradise of perpetual summer, where all good things abound, and where time and death hold no sway.

Oisín and Niamh travelling to Tír na nÓg. (Public Domain)

But soon he breaks a taboo of standing on a broad flat stone, from where he is able to view the Ireland he left behind. It has changed for the worse, and he begs Niamh to give him leave to return. She reluctantly agrees, but asks that he return after only one day with the mortals. She supplies him with a black horse, which he is not to dismount, and ‘gifted him with wisdom and knowledge far surpassing that of men.’ Once back in Ireland he realizes that decades have passed and that he is no longer recognized or known of. Inevitably, he dismounts his horse and immediately his youth is gone and he becomes an enfeebled old man with nothing but his immortal wisdom. There is no returning to the faerieland of the Tir na n’Og. In other variations of the story, the hero turns to dust as soon as his feet touch the ground of consensus reality.

The faeries as elementals (Courtesy author)

This important and widespread folktale motif seems to suggest that faerieland is the world of the dead, immune from the passage of time, and that return to the world of the living is not possible as the mortal body has aged and decayed in line with the physical laws of this world. In the Japanese tale of Urashima Taro, the hero, when returning home, is even given a casket by his faerie bride, in which his years are locked. When he opens it, his time is up. These stories articulate a belief in an otherworld that is never heaven, but is apparently ruled over by a race of immortals who can exert control over the consciousness of an individual, who may believe themselves to still be in human form, but are actually already dead and existing in non-material form. It is ultimately the place where the faeries come from; a place untouched by the passage of time and physical death. It could even represent the collective consciousness of humanity made into an understandable form in the stories, immortal in nature and containing all wisdom and knowledge, as suggested in the Oisín tale.

19th-century woodcut demonstrating the dangers of entering the faerie ring. (Public Domain)

This might be explained by seeing folktales of this type as representing a surviving pagan belief system of the afterlife. This afterlife did not follow the strictures of Christianity or other world religions, and provided an alternative view of what happens to consciousness after death. It is a view that was (in the West) superseded by Christian theology, but that may be surfacing in these folktales as remnants of the previous system of belief (a belief system that remained partially intact but operated underground for fear of religious persecution). The presence of faeries in this otherworld, and their ability to materialize in standard reality, suggests that they were an essential element in pagan ideas about consciousness and that they had a role to play when it came to death. In this theory the characters in the story play the part of messengers, telling us about the true nature of a timeless reality that is distinct and separate from consensus reality, and showing us that human consciousness disassociates from the physical body to exist in a parallel reality such as Tir na n’Og, where the faeries are in charge. This message is encoded in the stories.

Real Faeries and Shaman Spirits

However, it’s not possible to reduce the origin of the faeries only to abstract mythological themes. Their appearance in folklore often takes the form of witness testimonies or anecdotes, continuing to the present day. They take a myriad of different forms— leprechauns, sylphs, brownies, pixies, even aliens in a technologically updated version of their form— but they are portrayed as real entities, making appearances in this world from their own.

17th-century English woodcut showing faeries dancing in a ring, with hollow hill, amanita muscaria mushroom and 'spirit face' in the tree. (Public Domain)

They lure people into their magical dancing rings, abduct children and adults, play tricks on the unwary, process in faerie funeral corteges, and generally disport themselves with a sense of mischievous, and sometimes malevolent, immorality. There are countless descriptions of their metaphysical presence in our world, throughout time, playing a part in human culture, always liminal, but constantly present as far back as folklore stretches.

Neil Rushton is an archaeologist and freelance writer who has published on a wide variety of topics from castle fortifications to folklore. His first book is Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun.

Top Image: Cave painting from Kimberley, Australia, c.10,000 BCE (Public Domain)

By Neil Rushton

Published on October 01, 2017 00:00

September 29, 2017

Earthquake Faults May Have Shaken up the Cultural Practices of Ancient Greece

Ancient Origins

The Ancient Greeks may have built sacred or treasured sites deliberately on land previously affected by earthquake activity, according to a new study by the University of Plymouth.

Professor of Geoscience Communication Iain Stewart MBE, Director of the University's Sustainable Earth Institute, has presented several BBC documentaries about the power of earthquakes in shaping landscapes and communities.

Now he believes fault lines created by seismic activity in the Aegean region may have caused areas to be afforded special cultural status and, as such, led to them becoming sites of much celebrated temples and great cities.

Scientists have previously suggested Delphi, a mountainside complex once home to a legendary oracle, gained its position in Classical Greek society largely as a result of a sacred spring and intoxicating gases which emanated from a fault line caused by an earthquake.

Reconstruction of the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi in an 1894 painting by Albert Tournaire, now at École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts. (Public Domain)

But Professor Stewart believes Delphi may not be alone in this regard, and that other cities including Mycenae, Ephesus, Cnidus and Hierapolis may have been constructed specifically because of the presence of fault lines.

Professor Stewart said: "Earthquake faulting is endemic to the Aegean world, and for more than 30 years, I have been fascinated by the role earthquakes played in shaping its landscape. But I have always thought it more than a coincidence that many important sites are located directly on top of fault lines created by seismic activity. The Ancient Greeks placed great value on hot springs unlocked by earthquakes, but perhaps the building of temples and cities close to these sites was more systematic than has previously been thought."

Thermopylae derives half of its name from its hot springs. This river is formed by the steaming water which smells of sulfur. In the background, you can see buildings of the modern baths. In ancient times, the springs created a swamp. (CC BY SA 3.0)

In the study, published in Proceedings of the Geologists' Association, Professor Stewart says a correspondence of active faults and ancient cities in parts of Greece and western Turkey might not seem unduly surprising given the Aegean region is riddled with seismic faults and littered with ruined settlements.

But, he adds, many seismic fault traces in the region do not simply disrupt the fabric of buildings and streets, but run straight through the heart of the ancient settlements' most sacred structures.

Street scene at the archaeological excavations at Ephesus, an ancient Greek city on the west coast of Anatolia, near present-day Selçuk, Izmir Province, Turkey. (Ad Meskens/CC BY SA 3.0)

There are prominent examples to support the theory, such as in Delphi itself where a sanctuary was destroyed by an earthquake in 373 BC only for its temple to be rebuilt directly on the same fault line.

There are also many tales of individuals who attained oracular status by descending into the underworld, with some commentators arguing that such cave systems or grottoes caused by seismic activity may have formed the backdrop for these stories.

Heinrich Leutemann's The Oracle of Delphi Entranced. (Public Domain)

Professor Stewart concludes: "I am not saying that every sacred site in ancient Greece was built on a fault line. But while our association with earthquakes nowadays is that they are all negative, we have always known that in the long run they give more than they take away. The ancient Greeks were incredibly intelligent people and I believe they would have recognised this significance and wanted their citizens to benefit from the properties they created."

Top Image: Priestess of Delphi (1891) by John Collier. (Public Domain) Drawing of the Tholos of Delphi, Greece. (Public Domain)

The article, originally titled ‘Earthquake faults may have played key role in shaping the culture of ancient Greece’ was originally published on Science Daily.

Source: University of Plymouth. "Earthquake faults may have played key role in shaping the culture of ancient Greece." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 12 September 2017.

Reference: Iain S. Stewart. Seismic faults and sacred sanctuaries in Aegean antiquity. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association, 2017; DOI: 10.1016/j.pgeola.2017.07.009

Published on September 29, 2017 23:00

Rare Tomb Shows Bronze Age Mycenaean-era Nobleman had a Fondness for Jewelry

Ancient Origins

After 3,350 years, a Mycenaean-era nobleman’s tomb has been re-entered and his favored possessions have been seen by modern eyes. Archaeologists consider his burial an odd one, with grave goods and the style of the tomb standing out against others from his time.

The tomb was discovered during excavations near Orchomenos, Boeotia, Greece. It was unearthed during the first year of a five-year joint program between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia/Ministry of Culture and Sports and the British School at Athens/University of Cambridge. According to Euronews, the tomb is “the ninth largest of its kind to be discovered out of around 4,000 excavated in Greece over the last 150 years.”

Recording the bones in the burial chamber’s interior. (Greek Culture Ministry)

The tomb has a 20 meter (65.5 ft.) long rock-cut dromos (passageway) with rock cut benches covered in clay mortar. This hall leads to the 42 sq. meter (452 sq. ft.) burial chamber. It is believed the height to the pitched roof originally measured 3.5 meters ( 11.5 ft.) However, it has been proposed that the roof had already begun to fall apart in antiquity; which slightly moved the burial but also served as some protection for its contents from looters.

View of the Mycenaean-era tomb’s façade and the dry-stone masonry that sealed the entrance. (Ministry of Culture and Sports)

Upon entering the burial chamber, archaeologists found the remains of a man aged around 40-50 years old. Various grave goods were placed alongside his body: ten pottery vessels sheathed in tin, a pair of bronze snaffle-bits (a bit mouthpiece with a ring on either side used on a horse), and bow fittings and arrowheads. The most intriguing of the finds however is the collection of jewelry made of different materials, combs, a seal stone, and a signet ring. Unfortunately, images of the jewelry found in the tomb have yet to be released. Nonetheless, this provides a unique element to the burial, as jewelry was commonly believed to only have been placed in female burials in that period.

Bronze bits found in the Mycenaean-era tomb. (Giannis Galanakis)

The style of burial is also considered rare for Mycenaean chamber tombs. It’s far more common for archaeologists to find chamber tombs from this period which were used for multiple burials and contain grave goods, oftentimes looted or broken, from different generations.

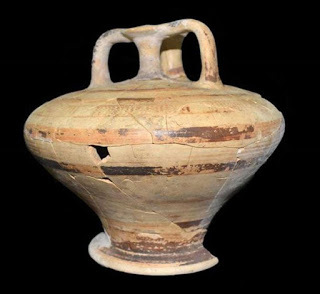

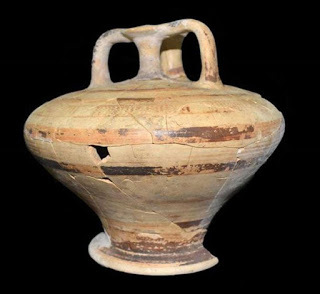

A final factor which sets this burial apart is the lack of decorated Mycenaean pottery in the tomb. Only two small stirrup jars were found, yet this pottery style was popular at that time. With so many different elements to consider, researchers expect this discovery to greatly improve their understanding of the variety of funeral practices used in this region during the Mycenaean period.

One of the two decorated stirrup jars found in the Mycenaean-era tomb. (Giannis Galanakis)

The Mycenaean era was the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece and is remembered for its palatial city-states, artwork, and writing. This period collapsed at the end of the Bronze Age, possibly due to the mysterious ‘people of the sea’ (or Sea People), Dorian invasion, or natural disasters and climate change – or some combination of these. Ancient Origins has previously reported about the impact the Mycenaean era had on ancient Greek literature and tomb building:

“Homer writes that the Mycenaean era was dedicated to Agamemnon, the king who led the Greeks in the Trojan War. The Mycenaean’s were keen traders, establishing contacts with countries across the Mediterranean and Europe. They were also excellent engineers and are also known for their characteristic ‘beehive’ tombs which were circular in shape with a high roof, consisting of a single stone passage leading to a chamber in which the possessions of the tomb’s occupant were also laid to rest.”

Gold death-mask known as the “Mask of Agamemnon.” (Xuan Che/CC BY 2.0) Homer writes that the Mycenaean era was dedicated to Agamemnon.

The tomb’s excavators believe that the recently unearthed site can be linked to the palatial center of Mycenaean Orchomenos – “the most important Mycenaean center of northern Boeotia during the 14th and 13th centuries BC.” They also call the site “one of the best documented burial groups of the Palatial period in mainland Greece.”

In 2015, Ancient Origins reported on another impressive Mycenaean-era discovery in Orchomenos. A pre-classical era Greek palace was found on Aghios Vassilios hill. Some researchers believe that this is the long-lost palace of Sparta.

The palace, which had 10 rooms, was probably built around the 17th to 16th centuries BC. Inscriptions written in Linear B script have also been found around that excavation site. They relate to religious practices and names and places. Archaeologists also discovered objects used for religious ceremonies, clay figurines, a cup adorned with a bull’s head, swords, and fragments of murals. Evidence suggests the palace was probably destroyed by fire at some point in the late 14th or early 13th century.

Mycenean Palace foundations at Orchomenus. (CC BY SA 4.0)

Top Image: Detail of the Mycenaean-era tomb’s façade and the dry-stone masonry that sealed the entrance. Source: Ministry of Culture and Sports

By Alicia McDermott

After 3,350 years, a Mycenaean-era nobleman’s tomb has been re-entered and his favored possessions have been seen by modern eyes. Archaeologists consider his burial an odd one, with grave goods and the style of the tomb standing out against others from his time.

The tomb was discovered during excavations near Orchomenos, Boeotia, Greece. It was unearthed during the first year of a five-year joint program between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia/Ministry of Culture and Sports and the British School at Athens/University of Cambridge. According to Euronews, the tomb is “the ninth largest of its kind to be discovered out of around 4,000 excavated in Greece over the last 150 years.”

Recording the bones in the burial chamber’s interior. (Greek Culture Ministry)

The tomb has a 20 meter (65.5 ft.) long rock-cut dromos (passageway) with rock cut benches covered in clay mortar. This hall leads to the 42 sq. meter (452 sq. ft.) burial chamber. It is believed the height to the pitched roof originally measured 3.5 meters ( 11.5 ft.) However, it has been proposed that the roof had already begun to fall apart in antiquity; which slightly moved the burial but also served as some protection for its contents from looters.

View of the Mycenaean-era tomb’s façade and the dry-stone masonry that sealed the entrance. (Ministry of Culture and Sports)

Upon entering the burial chamber, archaeologists found the remains of a man aged around 40-50 years old. Various grave goods were placed alongside his body: ten pottery vessels sheathed in tin, a pair of bronze snaffle-bits (a bit mouthpiece with a ring on either side used on a horse), and bow fittings and arrowheads. The most intriguing of the finds however is the collection of jewelry made of different materials, combs, a seal stone, and a signet ring. Unfortunately, images of the jewelry found in the tomb have yet to be released. Nonetheless, this provides a unique element to the burial, as jewelry was commonly believed to only have been placed in female burials in that period.

Bronze bits found in the Mycenaean-era tomb. (Giannis Galanakis)

The style of burial is also considered rare for Mycenaean chamber tombs. It’s far more common for archaeologists to find chamber tombs from this period which were used for multiple burials and contain grave goods, oftentimes looted or broken, from different generations.

A final factor which sets this burial apart is the lack of decorated Mycenaean pottery in the tomb. Only two small stirrup jars were found, yet this pottery style was popular at that time. With so many different elements to consider, researchers expect this discovery to greatly improve their understanding of the variety of funeral practices used in this region during the Mycenaean period.

One of the two decorated stirrup jars found in the Mycenaean-era tomb. (Giannis Galanakis)

The Mycenaean era was the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece and is remembered for its palatial city-states, artwork, and writing. This period collapsed at the end of the Bronze Age, possibly due to the mysterious ‘people of the sea’ (or Sea People), Dorian invasion, or natural disasters and climate change – or some combination of these. Ancient Origins has previously reported about the impact the Mycenaean era had on ancient Greek literature and tomb building:

“Homer writes that the Mycenaean era was dedicated to Agamemnon, the king who led the Greeks in the Trojan War. The Mycenaean’s were keen traders, establishing contacts with countries across the Mediterranean and Europe. They were also excellent engineers and are also known for their characteristic ‘beehive’ tombs which were circular in shape with a high roof, consisting of a single stone passage leading to a chamber in which the possessions of the tomb’s occupant were also laid to rest.”

Gold death-mask known as the “Mask of Agamemnon.” (Xuan Che/CC BY 2.0) Homer writes that the Mycenaean era was dedicated to Agamemnon.

The tomb’s excavators believe that the recently unearthed site can be linked to the palatial center of Mycenaean Orchomenos – “the most important Mycenaean center of northern Boeotia during the 14th and 13th centuries BC.” They also call the site “one of the best documented burial groups of the Palatial period in mainland Greece.”

In 2015, Ancient Origins reported on another impressive Mycenaean-era discovery in Orchomenos. A pre-classical era Greek palace was found on Aghios Vassilios hill. Some researchers believe that this is the long-lost palace of Sparta.

The palace, which had 10 rooms, was probably built around the 17th to 16th centuries BC. Inscriptions written in Linear B script have also been found around that excavation site. They relate to religious practices and names and places. Archaeologists also discovered objects used for religious ceremonies, clay figurines, a cup adorned with a bull’s head, swords, and fragments of murals. Evidence suggests the palace was probably destroyed by fire at some point in the late 14th or early 13th century.

Mycenean Palace foundations at Orchomenus. (CC BY SA 4.0)

Top Image: Detail of the Mycenaean-era tomb’s façade and the dry-stone masonry that sealed the entrance. Source: Ministry of Culture and Sports

By Alicia McDermott

Published on September 29, 2017 00:30

September 28, 2017

Two Roman Cavalry Swords and Two Toy Swords Amongst Treasures Found at Frontier Fort

Ancient Origins

Evidence of both work and play have been found at a Roman fort near Hadrian’s Wall in the UK. Two Roman swords as well as two wooden toy swords have been found in ongoing investigations which are uncovering a barracks area. Lead archaeologist, Dr Andrew Birley, said the finds were like "winning the lottery" reported the BBC.

Historical Vindolanda

The finds have been made in the last few weeks in a barracks area at the Vindolanda Roman fort archaeological dig in Northumberland, England. The fort has been a rich source of historical Roman artifacts for many years and remarkable past finds have included a huge hoard of shoes and two caches of Roman letters. The fort was abandoned when the Romans retreated from Britain around the 4th century AD and what has been found to have been left behind provides unique insight into the daily life led by the Roman soldiers and their families that occupied the fort.

The First Sword

The first of the full-size metal swords to be found was unearthed by a delighted volunteer, Rupert Bainbridge, who was digging in the corner of one of the living spaces that had been excavated, reported Past Horizons. The sword was slowly extracted, with first the tip of the sword’s blade being revealed and then the wooden scabbard becoming obvious. Once uncovered completely, it was found to be a complete full-length iron sword with a damaged, bent point. It is likely this damage led to the sword being discarded.

The first sword to be found had a bent end (Image: The Vindolanda Trust)

It might be thought that finding swords at a fort where a garrison of hundreds of soldiers lived would not be so uncommon. But swords were valuable possessions and not readily left. The rarity of such a find is clearly portrayed by the words reported by experienced Dr Birley who has been researching at Vindolanda for many years.

“You can work as an archaeologist your entire life on Roman military sites and, even at Vindolanda, we never expect or imagine to see such a rare and special object as this. It felt like the team had won a form of an archaeological lottery.”

Sword Number Two

After the first find the dig continued with fresh volunteers and was spurred on by Birley’s inexhaustible enthusiasm. Within just a few weeks another sword was discovered in the room adjacent to the first. This one was without the accompaniment of wooden handle, pommel or scabbard but the blade and tang was in excellent shape.

Sword Two with complete well-preserved blade (Image: The Vindolanda Trust)

Well, you can imagine the reaction of the animated Dr Birley who seemed genuinely astounded by the finds. He commented as reported by Past Horizons:

“You don’t expect to have this kind of experience twice in one month so this was both a delightful moment and a historical puzzle. You can imagine the circumstances where you could conceive leaving one sword behind rare as it is…. but two?”

Both swords found were for cavalry use – thin and short with a sharp blade for slashing from horseback.

Evacuation of a Complete Community

One of the most remarkable characteristics of Vindolanda is that it gives evidence of the life of a whole community, not just the soldiers. A good example of this comes with the find of two toy wooden swords. They serve to remind us that this place was inhabited by whole families including the soldier’s off-spring. This complex wasn’t only soldiers living, waiting, training and fighting rebels – there were children playing amongst them too.

One of the ancient toy wooden swords, with a gemstone in its pommel (The Vindolanda Trust)

The two wooden toy swords were found in another room and are said to be pretty similar to toy swords on sale at souvenir shops near Hadrian’s Wall today. Other everyday items that have been found recently include ink writing tablets on wood, bath clogs, leather shoes (from men, women and children), stylus pens, knives, combs, hairpins, brooches and pottery. The letters are particularly telling of the daily life, as has been reported in a previous Ancient Origins article on the finds. As would be expected of a fort that was quickly abandoned, a wide assortment of other weapons including cavalry lances, arrowheads and ballista bolts were left on the barrack room floors.

The rare conditions of oxygen free soil have allowed a lot of wooden items to be preserved where they would have disappeared due to decay in other areas. Some impressive shiny finds are the copper-alloy cavalry and horse fitments for saddles, junction straps and harnesses which were also left behind. These remain in such fine condition that they still shine like gold and are almost completely free from corrosion.

Cavalry Junction strap after conservation. (Image: The Vindolanda Trust)

Why was this Vindolanda Barracks Abandoned?

Although Vindolanda fort was occupied until the 9th century after which it was left for good, the Roman garrisons were long gone centuries before. In fact, these artifacts survived so well because they were hidden by a layer of concrete that was laid by the Romans about 30 years after these barracks had been abandoned reports the Guardian. It seems the Roman presence here to some extent ebbed and flowed. Successive garrisons have built on top of their predecessors at the site. From the sheer amount of possessions that have been found to have been left behind at this level of excavations it is obvious that the inhabitants had a distinct lack of time to pack their bags. But what would make a garrison of the mighty Roman Empire turn tale and flee?

The words of Dr Birley as reported by the Guardian might give us a clue.

“The swords are the icing on the cake for what is a truly remarkable discovery of one of the most comprehensive and important collections from the intimate lives of people living on the edge of the Roman Empire at a time of rebellion and war.”

This fort was right at the far frontier of the Roman Empire and the battle against the British rebels had already been long and hard by the time these barracks were constructed in around 105 AD. It seems possible from the repeated abandonment that the Romans suffered several defeats here and the outpost forces had to be replenished several times. The rebels on this frontier were so troublesome that about a century later, after his visit in 122 AD, the Emperor Hadrian decreed that the best way to deal with the situation was to build a wall that probably either aimed to keep the rebels out or at least to control immigration and smuggling.

Whatever the causes of abandonment, the result archaeologically is that at the deepest levels of the excavation are being found some of the best-preserved and most exciting artifacts.

Top image: Samian ware pottery that was found at the site at the end of last month (The Vindolanda Trust)

By Gary Manners

Evidence of both work and play have been found at a Roman fort near Hadrian’s Wall in the UK. Two Roman swords as well as two wooden toy swords have been found in ongoing investigations which are uncovering a barracks area. Lead archaeologist, Dr Andrew Birley, said the finds were like "winning the lottery" reported the BBC.

Historical Vindolanda

The finds have been made in the last few weeks in a barracks area at the Vindolanda Roman fort archaeological dig in Northumberland, England. The fort has been a rich source of historical Roman artifacts for many years and remarkable past finds have included a huge hoard of shoes and two caches of Roman letters. The fort was abandoned when the Romans retreated from Britain around the 4th century AD and what has been found to have been left behind provides unique insight into the daily life led by the Roman soldiers and their families that occupied the fort.

The First Sword

The first of the full-size metal swords to be found was unearthed by a delighted volunteer, Rupert Bainbridge, who was digging in the corner of one of the living spaces that had been excavated, reported Past Horizons. The sword was slowly extracted, with first the tip of the sword’s blade being revealed and then the wooden scabbard becoming obvious. Once uncovered completely, it was found to be a complete full-length iron sword with a damaged, bent point. It is likely this damage led to the sword being discarded.

The first sword to be found had a bent end (Image: The Vindolanda Trust)

It might be thought that finding swords at a fort where a garrison of hundreds of soldiers lived would not be so uncommon. But swords were valuable possessions and not readily left. The rarity of such a find is clearly portrayed by the words reported by experienced Dr Birley who has been researching at Vindolanda for many years.

“You can work as an archaeologist your entire life on Roman military sites and, even at Vindolanda, we never expect or imagine to see such a rare and special object as this. It felt like the team had won a form of an archaeological lottery.”

Sword Number Two

After the first find the dig continued with fresh volunteers and was spurred on by Birley’s inexhaustible enthusiasm. Within just a few weeks another sword was discovered in the room adjacent to the first. This one was without the accompaniment of wooden handle, pommel or scabbard but the blade and tang was in excellent shape.

Sword Two with complete well-preserved blade (Image: The Vindolanda Trust)

Well, you can imagine the reaction of the animated Dr Birley who seemed genuinely astounded by the finds. He commented as reported by Past Horizons:

“You don’t expect to have this kind of experience twice in one month so this was both a delightful moment and a historical puzzle. You can imagine the circumstances where you could conceive leaving one sword behind rare as it is…. but two?”

Both swords found were for cavalry use – thin and short with a sharp blade for slashing from horseback.

Evacuation of a Complete Community

One of the most remarkable characteristics of Vindolanda is that it gives evidence of the life of a whole community, not just the soldiers. A good example of this comes with the find of two toy wooden swords. They serve to remind us that this place was inhabited by whole families including the soldier’s off-spring. This complex wasn’t only soldiers living, waiting, training and fighting rebels – there were children playing amongst them too.

One of the ancient toy wooden swords, with a gemstone in its pommel (The Vindolanda Trust)

The two wooden toy swords were found in another room and are said to be pretty similar to toy swords on sale at souvenir shops near Hadrian’s Wall today. Other everyday items that have been found recently include ink writing tablets on wood, bath clogs, leather shoes (from men, women and children), stylus pens, knives, combs, hairpins, brooches and pottery. The letters are particularly telling of the daily life, as has been reported in a previous Ancient Origins article on the finds. As would be expected of a fort that was quickly abandoned, a wide assortment of other weapons including cavalry lances, arrowheads and ballista bolts were left on the barrack room floors.

The rare conditions of oxygen free soil have allowed a lot of wooden items to be preserved where they would have disappeared due to decay in other areas. Some impressive shiny finds are the copper-alloy cavalry and horse fitments for saddles, junction straps and harnesses which were also left behind. These remain in such fine condition that they still shine like gold and are almost completely free from corrosion.

Cavalry Junction strap after conservation. (Image: The Vindolanda Trust)

Why was this Vindolanda Barracks Abandoned?

Although Vindolanda fort was occupied until the 9th century after which it was left for good, the Roman garrisons were long gone centuries before. In fact, these artifacts survived so well because they were hidden by a layer of concrete that was laid by the Romans about 30 years after these barracks had been abandoned reports the Guardian. It seems the Roman presence here to some extent ebbed and flowed. Successive garrisons have built on top of their predecessors at the site. From the sheer amount of possessions that have been found to have been left behind at this level of excavations it is obvious that the inhabitants had a distinct lack of time to pack their bags. But what would make a garrison of the mighty Roman Empire turn tale and flee?

The words of Dr Birley as reported by the Guardian might give us a clue.

“The swords are the icing on the cake for what is a truly remarkable discovery of one of the most comprehensive and important collections from the intimate lives of people living on the edge of the Roman Empire at a time of rebellion and war.”

This fort was right at the far frontier of the Roman Empire and the battle against the British rebels had already been long and hard by the time these barracks were constructed in around 105 AD. It seems possible from the repeated abandonment that the Romans suffered several defeats here and the outpost forces had to be replenished several times. The rebels on this frontier were so troublesome that about a century later, after his visit in 122 AD, the Emperor Hadrian decreed that the best way to deal with the situation was to build a wall that probably either aimed to keep the rebels out or at least to control immigration and smuggling.

Whatever the causes of abandonment, the result archaeologically is that at the deepest levels of the excavation are being found some of the best-preserved and most exciting artifacts.

Top image: Samian ware pottery that was found at the site at the end of last month (The Vindolanda Trust)

By Gary Manners

Published on September 28, 2017 01:30

September 27, 2017

Rich Pickings in Luxor As Two Family Tombs are Found Including that of a Royal Goldsmith

Ancient Origins

In ongoing explorations of a necropolis at Luxor, archaeologists have opened a new tomb and the findings have been rich. Amongst the 3,500-year-old treasures are jewels, sarcophagi, pottery and four mummies, known to be the remains of a goldsmith and his family.

Multiple Finds

This is the latest in a series of interesting tombs that archaeologists have unearthed in Egypt in the last few months. It is the tomb of Amenemhat, a prominent goldsmith from the 18th Dynasty, New Kingdom period (1550 BC to 1292 BC). It has been found on the West Bank of the Nile at Luxor, in the Draa Abul Naga necropolis, an area which is known to contain the burials of many prominent noblemen and top officials, reports the Telegraph. According to Dr. Mostafa Waziri, Director General of Luxor, who is leading the dig, the tomb’s entrance is located in the courtyard of a Middle Kingdom tomb. Found in the same exploration was another burial shaft containing the mummies of a woman and two children, revealed the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities in an announcement on Saturday, reports the Telegraph.

A researcher studies a hoard of remains found at the necropolis (Ministry of Antiquities)

Amenemhat’s Complex

The Ministry claims the tomb is of ‘Amen’s Goldsmith’, as it seems that Amenemhat dedicated his work to the most revered deity of the time, Amen. Antiquities Minister Khaled el-Anani told reporters that the tomb is not in the best condition, reports stthomastimesjournal but as infiltrators of the burial place enter, they are immediately confronted by a slightly damaged sandstone statue of both the goldsmith and his wife, Amenhotep seated next to each other, overlooking their final resting sanctuary beyond. At the feet of the couple, the image of one of their sons is carved as a relief.

The daughter, or as they used to refer (to daughters) 'the precious,' is usually the one pictured in this place. If the family have no daughters, they would take their daughter-in-law. It is unusual to see the son," said Waziri reported CNN.

Moving past this point, Waziri explained you find two burial shafts. The one to the right is 7 meters (23 ft) in length and was probably to house the goldsmith and his wife. In it were found several mummies, sarcophagi, funerary masks, together with several other statues of the couple.

In the shaft to the left, the evidence was quite clear that the tomb had been reused at a later date, as in this second chamber there were sarcophagi from the 21st and 22nd Dynasties or the Third Intermediate Period (1070BC to 664BC) reported the Guardian.

One of several statue representations of Amenemhat, the goldsmith, and his wife Amenhoteb (Ministry of Antiquities)

Another Family Resting Place

Along another burial shaft that was found close-by this tomb were found the mummies of a woman and two children. According to the ministry bone specialist, Sherine Ahmed Shawqi, the woman looks to have died at the age of 50 and showed signs that she had a bacterial bone disease, said the Telegraph. In this instance, the bodies were in two separate coffins with the children sharing one and the mother in the other according to the Ministry of Antiquities.

The lady seemed to have endured an uncomfortable end. “This woman probably cried extensively as the size of her carbuncles are abnormally enlarged,” postulated Shawqi.

The two other bodies, presumed her children, seem to be of two males aged between 20 and 30. It is thought that these would have been added to the burial place at later dates to the parent.

An Egyptian archaeologist looks at a newly-uncovered sarcophagus in the Draa Abul Naga necropolis (Ministry of Antiquities)

More to Come

Other items exposed during the excavation included a cache of 50 funerary cones. Of these cones, 40 are believed to belong to other officials from the time, whose remains have yet to be found. “This is a good sign,” said the leader of the excavation, Mostafa al-Waziry, as reported by the Guardian, “It means if we keep digging in this area, we are going to find more tombs.”

Although this find is not of a very high-profile personage from the past on the level of a pharaoh, the discovery is seen to be important by the Antiquity Ministry as it was found by Egyptian archaeologists working independently of the international research community.

“We used to escort foreign archaeologists as observers, but that’s now in the past. We are the leaders now,” said Mustafa Waziri, the ministry’s chief archaeologist in Luxor.

The continuation of archaeological investigations in Egypt are of high importance and these new finds add to the momentum. Egyptian minister of antiquities, Khaled Alnani, called it “an important scientific discovery” and went on to call 2017, “a year or archaeological discoveries.”

And he is not exaggerating. To mention just a few examples of finds, Ancient Origins reported on a huge tomb find in April, containing mummies and thousands of artifacts that belonged to a city advisor. In March, an 8 meter (26 ft) statue of Psamtek I was unearthed. Last month, a Roman-era tomb was uncovered near the Upper Egyptian town of Minya.

These recent finds have come after a quiet time for archaeology in Egypt since the disruption of the Arab Spring protests in 2011 and subsequent terrorist actions. According to the Guardian, such a loss of tourist revenue has severely reduced the capacity for of the Antiquities Ministry to maintain the ancient monuments. It is hoped that tourism, which is currently at a third of previous levels, will be encouraged by the recent flurry of finds.

Top image: Mummies of a woman and two children found in burial chamber at Draa Abul Naga, Luxor (Ministry of Antiquities)

By Gary Manners

Published on September 27, 2017 01:00

September 26, 2017

Hunters Find Striking Viking Sword Isolated at High Altitude in Norway

Ancient Origins

Four friends were slowly making their way across the high altitude rocky terrain while hunting reindeer in Oppland, Norway. One noticed a rusty object sticking out of the rocks. Curiosity took over and he sped up to reach the spot, where he soon found himself in front of an impressive-looking sword. After releasing the sword from its rocky hold, the friends decided that it didn’t look like anything modern, so they headed back down the mountain with their treasure to consult a local archaeologist.

Detail of the Viking Age sword found in Oppland, Norway. Source: Secrets of the Ice

That archaeologist, and also another in Dagbladet, confirmed that the sword wasn’t made recently. In fact, archaeologist Espen Finstad told Dagbladet news that the sword was a Viking Age relic created in the 900s AD.

Finstad is also the chief editor of Secrets of the Ice, a group of glacier archaeologists working in the same region where the Viking Age sword was found. Realizing the importance to return quickly to the site, the Secrets of the Ice team spoke with the Museum of Cultural History and the National Park authorities.

Einar Åmbakk, who discovered the sword, one of his hunting trip friends, a local metal detectorist, a local archaeologist, and two members of the Secrets of the Ice team got themselves ready for a brisk three hour walk back up the mountain to reach the location where the sword was found.

Einar Åmbakk holding the sword, just moments after it was discovered. (Einar Åmbakk)

In their report on the Viking Age sword, Secrets of the Ice described the context in which the sword was found:

“The find spot is in a scree-covered area with traces of permafrost movement, situated at 1640 m [5380 ft.] above sea level. Einar Åmbakk told us that the sword was lying with the hilt down between the stones and half of the blade sticking out. He had seen the blade and pulled it out. Only then did he understand that he had found a sword.”

They go on to write that the sword was probably found in its original position, or had perhaps slid between the stones; it’s unlikely that permafrost movement of the stones had pushed it to the surface.

Secrets of the Ice wrote, “The preservation is probably due to a combination of the quality of the iron, the high altitude and the mostly cold conditions. For most of the year, the find spot would have been frozen over and covered in snow.”

The Viking sword, dated to c. AD 850-950. (Espen Finstad, Secrets of the Ice/ Oppland County Council)

The group surveyed and used a metal detector to cover an area of 20 meters (65 ft.) around the sword’s discovery location. No indications of human remains, the sword grip cover of bone, wood or leather (which would have not been preserved in those conditions anyway), nor any other artifacts were found. Thus, there is a mysterious air about the sword and how it came to be left in such a desolate location.

Secrets of the Ice suggest a possible, though still curious, explanation:

“This could suggest that the person who left behind the sword was lost, maybe in a snow blizzard. It seems likely that the sword belonged to a Viking who died on the mountain, perhaps from exposure. However, if that is indeed the case, was he traveling in the high mountains with only his sword? It is a bit of a mystery… As it is now, his remains are long gone, and only the sword bears witness to the drama that happened here more than one thousand years ago.”

‘Viking Across the Land of the Dead Giants.’ (Jean-Michel Trauscht)

The Viking sword is certainly an intriguing find, but it is not the only example of well-preserved artifacts being found at high altitude in that area. Almost one year ago, in October 2016, Ancients Origins reported on another discovery made by the Secrets of the Ice team - a number of arrowheads found in the melting glacier on the mountain Kvitingskjølen in southern Norway’s Jotunheimen range.

Some of the arrowheads have been dated to between 900-1050 AD based on the types of arrows and techniques used in their creation. However, additional evidence suggests other points may be much older. As Espen Finstad said, “The oldest finds here are around 6000 years old. Which means that there’s been hunting here for at least that long.”

So far, the Secrets of the Ice project website says that 49 glaciers and ice patches in Oppland have revealed artifacts. Hunting tools, transport equipment, textiles, leather and clothing have all been recovered by the archaeologists. Moreover, zoological material has also been found in the form of antler, bone, and dung.

Although the receding glaciers may seem to make the discovery of the arrows and other lost or discarded artifacts easier, the lack of an ice covering also presents a problem - without the protection of the ice, artifacts are exposed to the elements. The race against time and the weather means that the glacier archaeologists must try to work quickly but thoroughly to save as much as they can.

Top Image: The Viking Age sword found in Oppland, Norway. (Source: Youtube Screenshot)

By Alicia McDermott

Published on September 26, 2017 01:00

September 25, 2017

First Genetic Proof of a Viking Age Warrior Woman is Identified from an Iconic Swedish Grave

Ancient Origins

Then the high-born lady saw them play the wounding game, she resolved on a hard course and flung off her cloak; she took a naked sword and fought for her kinsmen's lives, she was handy at fighting, wherever she aimed her blows.” - ‘The Greenlandic Poem of Atli’ (st. 49) (Larrington, 1996)

Arguably the most iconic example of a warrior burial in Viking Age Sweden is a mid-10th century grave in Birka. This grave has been the example of what a Viking warrior burial should look like for over a century. Everyone assumed that a man was the one laid to rest in the grave – but new research shows assumptions should not be taken as fact. It is the remains of a warrior woman in that grave.

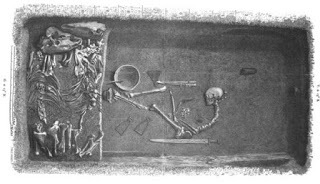

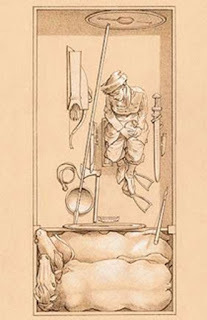

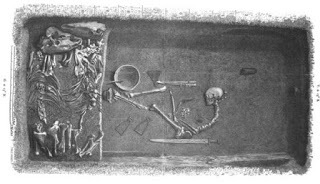

Illustration by Evald Hansen based on the original plan of the Viking Age warrior grave (Bj 581) by excavator Hjalmar Stolpe; published in 1889. (Stolpe, 1889)

According to The Local, the first person to do something about the fact that the skeleton’s morphological features don’t coincide with a male body was Anna Kjellström, an osteologist at Stockholm University. Kjellström was examining the skeleton for an unrelated research project when she noticed that the cheekbones were finer and thinner than men would normally have. However, the tell-tale sign that the skeleton is female is the obvious nature of the hip bones.

After a thorough osteological analysis, DNA testing was applied. And, as Phys.org reports “DNA retrieved from the skeleton demonstrates that the individual carried two X chromosomes and no Y chromosome.” Based on the results of the study, Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson of Stockholm University, who led the research, asserted, “It’s actually a woman, somewhere over the age of 30 and fairly tall too, measuring around 170 centimetres [5.5ft.]”

Furthermore, the researchers write in their journal article that. “The Viking warrior female showed genetic affinity to present-day inhabitants of the British Islands (England and Scotland), the North Atlantic Islands (Iceland and the Orkneys), Scandinavia (Denmark and Norway) and to lesser extent Eastern Baltic Europe (Lithuania and Latvia).”

Romanticized depiction of a Viking woman, 1905, by Andreas Bloch. (Public Domain)