MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 45

September 14, 2017

Ancient Mall Found in Famous Theater City of Aspendos Shows Commerce and Entertainment Went Hand-in-Hand

Ancient Origins

The ancient city of Aspendos was a major commercial center in Roman times. The recent excavations of a large shop complex with offices and storage facilities dating back some 2,000 years provide more insight on the products that were stored and sold near the city’s famous theater. Akin to cinemas found in shopping malls today, the Romans here combined both commerce and entertainment too.

A 2000-year-old two-story shop complex has been excavated at Aspendos, Turkey. (CROSS)

Many coins were discovered in the shops from the Hellenistic and Roman eras. Aspendos coins, minted from the 5th century BC, were often used in the Hellenistic era. The recently unearthed coins had the figure of a slingshot stone on one side and a horse depicted on the other. The appearance of a horse can be connected to Aspendos’ recognition for horse breeding.

Example of a silver stater coin from Aspendos dating to 370-333 BC. Obverse: Olympic games-type scene: two wrestlers grappling, the letters delta and alpha between their legs; Reverse: Olympic games-type scene of a slinger, wearing short chiton, discharging sling to right, triskeles on right with feet clockwise. (Ancientcointraders/CC BY SA 4.0)

Hacettepe University Archaeology Department’s Veli Köse is currently heading the excavations at Antalya and told Hurriyet Daily “We think valuable materials were sold or held in these stores. Some were used as offices. The fact that such a unique structure was unearthed right next to the agora in the city center supports this idea.”

Some of the products that were apparently stored and sold in the complex include: a small glass amphora, pieces of oil and perfume bottles, candles, a bronze belt buckle, a bone hair pin, and lots of studs and rings.

Some of the artifacts found at the shop complex location of the site of Aspendos, Turkey. (Daily Sabah)

The shops were the focus of the recent excavations, yet the team also found hundreds of mussel shells in a field and some wall painting remnants at other locations around the site.

“The existence of two-storey shops and a structure complex in an ancient city symbolizes that this place was an important commercial center. We also know it from the inscriptions. Aspendos is famous especially for grain harvest and horse breeding,” Köse concluded.

The ancient city of Aspendos was established in the 10th century BC. It was likely the most important city in Pamphylia, with its golden age being the Roman period – a great time for trade and commerce. Legends say the famous Greek diviner Mopsos founded the city, however, evidence of a Hittite settlement brings up some debate about the first inhabitants. The city came under Persian rule in the 6th century BC. It was then taken by Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC. By the Roman period, Aspendos was an important harbor city. Yet, it fell from grace in the Byzantine period with the empire’s centralization policies. It has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2015.

Ruins of the Basilica at Aspendos, Turkey. (Saffron Blaze/CC BY SA 3.0)

The city is most famous for its Roman theater, the Aspendos Ancient Theater, which seats 7,000 people. The theater is one of the most visited historic sites in Turkey's Antalya province and it is the best preserved ancient theater in the country. Another feature that makes the theater famous is its remarkable acoustics. Even the slightest sound made at the center of the orchestra can be easily heard as far as the uppermost galleries. The theater hosts events by the Aspendos Opera and a ballet festival in the summer.

The theater at Aspendos, Turkey. (CC BY SA 3.0)

Apart from the theater, the Aspendos archaeological site also contains the ruins of a small temple, a nymphaeum (fountain shrine), the foundations of a bouleuterion (council chamber), and a Roman aqueduct.

Roman aqueduct of Aspendos, Turkey. (Bernard Gagnon/CC BY SA 3.0)

Top Image: The famous Roman theater at Aspendos, Turkey. Source: Saffron Blaze/CC BY SA 3.0

By Alicia McDermott

The ancient city of Aspendos was a major commercial center in Roman times. The recent excavations of a large shop complex with offices and storage facilities dating back some 2,000 years provide more insight on the products that were stored and sold near the city’s famous theater. Akin to cinemas found in shopping malls today, the Romans here combined both commerce and entertainment too.

A 2000-year-old two-story shop complex has been excavated at Aspendos, Turkey. (CROSS)

Many coins were discovered in the shops from the Hellenistic and Roman eras. Aspendos coins, minted from the 5th century BC, were often used in the Hellenistic era. The recently unearthed coins had the figure of a slingshot stone on one side and a horse depicted on the other. The appearance of a horse can be connected to Aspendos’ recognition for horse breeding.

Example of a silver stater coin from Aspendos dating to 370-333 BC. Obverse: Olympic games-type scene: two wrestlers grappling, the letters delta and alpha between their legs; Reverse: Olympic games-type scene of a slinger, wearing short chiton, discharging sling to right, triskeles on right with feet clockwise. (Ancientcointraders/CC BY SA 4.0)

Hacettepe University Archaeology Department’s Veli Köse is currently heading the excavations at Antalya and told Hurriyet Daily “We think valuable materials were sold or held in these stores. Some were used as offices. The fact that such a unique structure was unearthed right next to the agora in the city center supports this idea.”

Some of the products that were apparently stored and sold in the complex include: a small glass amphora, pieces of oil and perfume bottles, candles, a bronze belt buckle, a bone hair pin, and lots of studs and rings.

Some of the artifacts found at the shop complex location of the site of Aspendos, Turkey. (Daily Sabah)

The shops were the focus of the recent excavations, yet the team also found hundreds of mussel shells in a field and some wall painting remnants at other locations around the site.

“The existence of two-storey shops and a structure complex in an ancient city symbolizes that this place was an important commercial center. We also know it from the inscriptions. Aspendos is famous especially for grain harvest and horse breeding,” Köse concluded.

The ancient city of Aspendos was established in the 10th century BC. It was likely the most important city in Pamphylia, with its golden age being the Roman period – a great time for trade and commerce. Legends say the famous Greek diviner Mopsos founded the city, however, evidence of a Hittite settlement brings up some debate about the first inhabitants. The city came under Persian rule in the 6th century BC. It was then taken by Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC. By the Roman period, Aspendos was an important harbor city. Yet, it fell from grace in the Byzantine period with the empire’s centralization policies. It has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2015.

Ruins of the Basilica at Aspendos, Turkey. (Saffron Blaze/CC BY SA 3.0)

The city is most famous for its Roman theater, the Aspendos Ancient Theater, which seats 7,000 people. The theater is one of the most visited historic sites in Turkey's Antalya province and it is the best preserved ancient theater in the country. Another feature that makes the theater famous is its remarkable acoustics. Even the slightest sound made at the center of the orchestra can be easily heard as far as the uppermost galleries. The theater hosts events by the Aspendos Opera and a ballet festival in the summer.

The theater at Aspendos, Turkey. (CC BY SA 3.0)

Apart from the theater, the Aspendos archaeological site also contains the ruins of a small temple, a nymphaeum (fountain shrine), the foundations of a bouleuterion (council chamber), and a Roman aqueduct.

Roman aqueduct of Aspendos, Turkey. (Bernard Gagnon/CC BY SA 3.0)

Top Image: The famous Roman theater at Aspendos, Turkey. Source: Saffron Blaze/CC BY SA 3.0

By Alicia McDermott

Published on September 14, 2017 01:00

September 13, 2017

New Study Reveals that London was the Most Violent Place in Medieval England

Ancient Origins

A new study suggests that medieval London was notorious for its excessive violence. The overall findings suggest that violence affected many parts of medieval London, although predictably it disproportionately affected the lower socioeconomic classes.

Analysis of 399 Skulls Reveals London’s Violent Past

Medieval times could be truly rough times for any man – especially a poor one – as a new study shows. The study identified the patterns and prevalence of violence-related skull trauma among a large sample of skeletons from medieval London. “It appears that violence in medieval London may have been largely tied to sex and social status,” archaeologist Kathryn Krakowka from the University of Oxford tells New Scientist, having reached that conclusion after examining 399 skulls from six different sites from across medieval London (1050-1550).

The skulls were analyzed for evidence of trauma and assessed for the likelihood that it was caused by violence. Kathryn Krakowka and her team collected the skulls from two types of cemeteries; monastic and free parish. The monastic cemeteries were usually reserved for the upper class while the free parish was used by the lower socioeconomic classes.

Skull exhibiting trauma fracture (Museum of London)

Poor Suffered More Violence

Unsurprisingly, males from the free parish cemeteries appear to have been the demographic most affected by violence-related skull injuries, particularly blunt force trauma to the cranial vault. Specifically, Krakowka found that 6.8 per cent of all skulls examined showed some kind of violence-related trauma, while it was mostly males from 26 to 35 years old that were affected. Additionally, nearly 25 per cent of the skull injuries took place near the time of death, indicating that people died from blows to their heads.

Furthermore, Krakowka noticed that the London cemeteries she explored had a violence rate almost double than elsewhere else in England. Despite the results showing violence was more prevalent in medieval London than in any other part of medieval England, it appears to be quite similar to other parts of medieval Europe. “High levels of violence are evident in cemeteries from other parts of medieval Europe such as Croatia,” Krakowka told New Scientist, as a similar study showed an incredible 20.1 per cent of people had cranial fractures in Croatia.

Triumph of the Deputies, William Hogarth, 1764. (Public Domain)

Poor Had No Access to Law

The fact that males from the free parish cemeteries were disproportionately affected by violence-related trauma, especially blunt force trauma, makes Krakowka speculate that this could be the result of an informal conflict resolution between individuals of lower status, as the newly established medieval legal system wasn’t available to them as they couldn’t afford the fees or didn’t know how to access the services. On the other hand, she concludes that the upper classes had access to the developing legal system of the time, and this was how they usually avoided a more informal (and violent) way of resolving disputes.

Coroners’ rolls from the time bolster Krakowka’s suggestions as it shows that a way too large amount of homicides took place on Sunday night, when many working-class men would have been drinking at a pub, and on Monday morning. “This, in combination with my results, possibly suggests that those of lower status resolved conflict through informal fights that may or may not have been fueled by drunkenness,” Krakowka tells New Scientist.

Luke Glowacki, an anthropologist from the Institute for Advanced Study in Toulouse, France, agrees with Krakowka’s conclusions, “People of low status don’t have resort to the rule of law. Unable to hire a barrister to represent them, they resort to violence as a means to resolve conflict,” he tells New Scientist. To conclude, the researchers also noted that even if individuals from the upper class decided to solve a dispute between them (outside a court), they would have most likely fought under different rules, where swords were in play and armor would be involved in order to protect the heads of the opponents.

Top image: Fight with Cudgels, 1819-1823 by Francisco de Goya (Public Domain)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A new study suggests that medieval London was notorious for its excessive violence. The overall findings suggest that violence affected many parts of medieval London, although predictably it disproportionately affected the lower socioeconomic classes.

Analysis of 399 Skulls Reveals London’s Violent Past

Medieval times could be truly rough times for any man – especially a poor one – as a new study shows. The study identified the patterns and prevalence of violence-related skull trauma among a large sample of skeletons from medieval London. “It appears that violence in medieval London may have been largely tied to sex and social status,” archaeologist Kathryn Krakowka from the University of Oxford tells New Scientist, having reached that conclusion after examining 399 skulls from six different sites from across medieval London (1050-1550).

The skulls were analyzed for evidence of trauma and assessed for the likelihood that it was caused by violence. Kathryn Krakowka and her team collected the skulls from two types of cemeteries; monastic and free parish. The monastic cemeteries were usually reserved for the upper class while the free parish was used by the lower socioeconomic classes.

Skull exhibiting trauma fracture (Museum of London)

Poor Suffered More Violence

Unsurprisingly, males from the free parish cemeteries appear to have been the demographic most affected by violence-related skull injuries, particularly blunt force trauma to the cranial vault. Specifically, Krakowka found that 6.8 per cent of all skulls examined showed some kind of violence-related trauma, while it was mostly males from 26 to 35 years old that were affected. Additionally, nearly 25 per cent of the skull injuries took place near the time of death, indicating that people died from blows to their heads.

Furthermore, Krakowka noticed that the London cemeteries she explored had a violence rate almost double than elsewhere else in England. Despite the results showing violence was more prevalent in medieval London than in any other part of medieval England, it appears to be quite similar to other parts of medieval Europe. “High levels of violence are evident in cemeteries from other parts of medieval Europe such as Croatia,” Krakowka told New Scientist, as a similar study showed an incredible 20.1 per cent of people had cranial fractures in Croatia.

Triumph of the Deputies, William Hogarth, 1764. (Public Domain)

Poor Had No Access to Law

The fact that males from the free parish cemeteries were disproportionately affected by violence-related trauma, especially blunt force trauma, makes Krakowka speculate that this could be the result of an informal conflict resolution between individuals of lower status, as the newly established medieval legal system wasn’t available to them as they couldn’t afford the fees or didn’t know how to access the services. On the other hand, she concludes that the upper classes had access to the developing legal system of the time, and this was how they usually avoided a more informal (and violent) way of resolving disputes.

Coroners’ rolls from the time bolster Krakowka’s suggestions as it shows that a way too large amount of homicides took place on Sunday night, when many working-class men would have been drinking at a pub, and on Monday morning. “This, in combination with my results, possibly suggests that those of lower status resolved conflict through informal fights that may or may not have been fueled by drunkenness,” Krakowka tells New Scientist.

Luke Glowacki, an anthropologist from the Institute for Advanced Study in Toulouse, France, agrees with Krakowka’s conclusions, “People of low status don’t have resort to the rule of law. Unable to hire a barrister to represent them, they resort to violence as a means to resolve conflict,” he tells New Scientist. To conclude, the researchers also noted that even if individuals from the upper class decided to solve a dispute between them (outside a court), they would have most likely fought under different rules, where swords were in play and armor would be involved in order to protect the heads of the opponents.

Top image: Fight with Cudgels, 1819-1823 by Francisco de Goya (Public Domain)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on September 13, 2017 01:00

September 12, 2017

Two Pregnant Women and their Fetuses Latest Victims of Mount Vesuvius’ Eruption

Ancient Origins

fter being buried in ash for more than 1,900 years, new victims of the devastating eruption in the Pompeii area have been discovered, including two pregnant women and their newborn or late-term fetuses. Experts suggest that the new discovery could be a “game-changer” for Roman bioarcheology.

The Catastrophic Eruption

Mount Vesuvius was responsible for the destruction of the city of Pompeii on August 24, 79 AD and is without a doubt the most famous volcanic eruption in history, even though not the deadliest one, as many people falsely tend to believe. Still, scientists have estimated that Mt. Vesuvius released thermal energy 100,000 times more powerful than the atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II. For the record, before the eruption of Vesuvius, there was no word for volcano. They had to come up with one right after the catastrophic eruption. The word is derived from “Vulcan," the Roman God of Fire.

New Skeletons are Discovered

As Fox News reports, the estimates as to how many people were killed in Pompeii vary greatly, and the number has been a heated topic of debate among historians for decades. Most historians, however, will agree that at least a thousand people were buried under dozens of feet of lava in the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. It might sound macabre, but the tons of ash and hot gas that killed so many of Pompeii’s citizens, are also the reason why their bodies have been so greatly preserved.

Villa Oplontis as it is today (CC BY SA 2.0)

Surprisingly, the human remains of four more victims, two pregnant women and their newborn or late-term fetuses as Fox News reports, have been found among an estimated fifty others in a building in the nearby villa of Oplontis. Despite more than half of these fifty skeletons being unearthed during the mid-1980s and the others being partly uncovered in 1991, the human remains of the women and their fetuses were fully excavated only a few weeks ago. “This summer, I headed a small team that excavated the remaining skeletons and collected osteological data on all of the people who were trapped at Oplontis by the volcano,” Kristina Kilgrove, a bioarcheologist at the University of West Florida, wrote in Forbes.

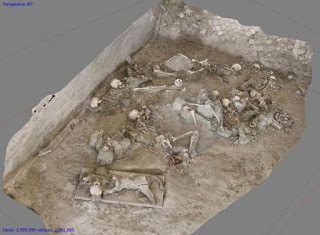

Photomodel of skeletons in situ, Room 10, Oplontis B (Torre Annunziata, Italy). (Credit: N.Terrenato and M. Naglak, University of Michigan)

Newly Discovered Skeletons Could be “Game-Changer”

After sitting beneath a thick layer of ash for more than 1,500 years, Pompeii was accidentally discovered in 1599 when the workers who were digging a water channel unearthed frescoes and an inscription containing the name of the city. The most decorated Italian architect of the time, Domenico Fontana, visited the site to examine the finds and unearthed a few more frescoes. Unfortunately, he was also a huge prude. He re-covered them because of the excessive sexual content of the paintings. In this way, the city became buried again (thanks to censorship) for nearly another 150 years before the king of Naples, Charles of Bourbon, ordered the proper excavation of the site during the late 1740s.

Since then, Pompeii became the center of interest for thousands of archaeologists, historians and scientists. An excited Kilgrove, however, believes that the discovery of the four new “victims” could change Roman history and add even more (cultural) prestige to Pompeii, “These newly analyzed skeletons from Oplontis are a game-changer in Roman bioarcheology, since they represent people who all died catastrophically, rather than after an illness. This means that these skeletons give archaeologists a better glimpse into what life was like for people in their prime than do cemetery burials,” she wrote in Forbes.

She goes on to explain why the skeletons of the women and their fetuses could be particularly intriguing, “While their biological relationship is not in question, their disease status and diet certainly are. If the mother suffered from an intestinal parasite or an infectious disease, did that affect the fetus as well? How will the carbon and nitrogen isotopes reflect the mother's diet of food and the fetus's ‘diet’ of maternal nutrition and energy stores? For our further research, we hope to answer questions such as these that cannot be solved through study of history and archaeology alone,” she writes in Forbes.

Vesuvius erupting at Night, (William Marlow circa 1768) (Public Domain)

Only One Firsthand Account Exists

Ultimately, despite being the most famous volcanic eruption throughout the centuries, there’s only one recorded account saved that describes the catastrophic aftermath of the Mount Vesuvius eruption and it comes from Pliny the Younger. In a letter to Tacitus, Pliny describes what he experienced during the second day of the disaster:

“A dense black cloud was coming up behind us, spreading over the Earth like a flood. 'Let us leave the road while we can still see,' I said, 'or we shall be knocked down and trampled underfoot in the dark by the crowd behind.' We had scarcely sat down to rest when darkness fell, not the dark of a moonless or cloudy night, but as if the lamp had been put out in a closed room. You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, and the shouting of men; some were calling their parents, others their children or their wives, trying to recognize them by their voices. People bewailed their own fate or that of their relatives, and there were some who prayed for death in their terror of dying. Many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness forevermore.”

Top image: Skeletons in the' Boat Houses', Herculaneum (Public Domain)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on September 12, 2017 01:00

September 11, 2017

Roman Era Tombs Discovered in Egypt Reveal Diverse Trends in Burial Architecture and Grave Goods

Ancient Origins

Not all Egyptian tombs are alike. Apart from the impact of social status, there is also a difference in architectural styles and burial preferences over the long history of their existence. This can be noted in five Roman era mudbrick tombs which have been unearthed during excavation works at the Beir Al-Shaghala site in Dakhla Oasis.

The Beir Al-Shaghala site is located near three other archaeological sites - Mut al- Kharab, Tal Markula, and Koam Beshay. The well-preserved tombs were found by an archaeological mission from the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, who have been working at the site since 2002 according to Egypt Independent.

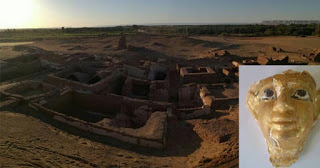

Tombs at the Beir Al-Shaghala site, Egypt. (Ministry of Antiquities)

Head of the Ancient Egyptian Antiquities Sector Ayma Ashmawi described the differing layouts of the tombs to Egyptian Streets:

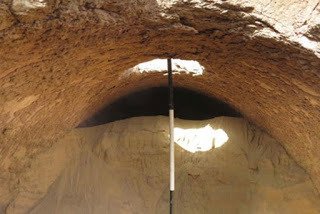

“The first one has an entrance that leads to a rectangular hall with two burial chambers; the second tomb has a domed ceiling and its entrance leads to a burial chamber, while the third one is a pyramid shaped tomb which the mission has yet succeeded to uncover its upper part. The fourth and fifth tombs are sharing one entrance and each tomb has a burial chamber with a domed ceiling.”

The vaulted ceiling in one of the tombs. (Ministry of Antiquities)

The tombs have provided a wealth of interesting artifacts. So far, Ahram Online reports archaeologists have found pottery vessels of varying shapes and sizes, a gypsum funerary mask painted yellow, a clay incense burner, and the base of a small sandstone sphinx statue.

The funerary mask found in one of the tombs. (Ministry of Antiquities)

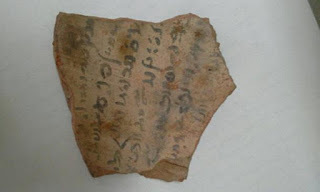

Two ostraca (ink-inscribed shards of pottery) were also discovered - one written in hieroglyphic text and the other in hieratic. Bryan Hill explained the rise of hieratic script in a previous article for Ancient Origins. He wrote:

“Egyptian hieroglyphs are among the oldest writing systems in the world, dating back some 5,200 years […] Around 2700 BC, hieratic (meaning ‘priestly’ by the Greeks) script was introduced which was a form of writing more akin to alphabet letters. Hieratic script eventually became widely used as a faster, more functional form of writing and used for monumental inscriptions. It remained the Egyptian script for about two millennia or until Demotic script was introduced in the 7th century BC.”

An ostracon found in a tomb. (Ministry of Antiquities)

Work will continue at Beir Al-Shaghala to see if more ancient treasures can be recovered.

The five tombs add to eight other well-preserved Roman era tombs that were discovered in previous excavations at the archaeological site.

University College London explains some of the general differences in tomb style and burial preferences in the Roman era of Egypt. By the Roman period, shabtis and canopic jars were out of fashion (they were ‘so pre-Ptolemaic Period’). Instead, “Objects of daily use […] became a popular burial good again under Roman rule: in particular, cosmetic objects are commonly found with women.” This Roman era excavation is thus important as few cemeteries of the Roman Period have been properly audited and finds documented.

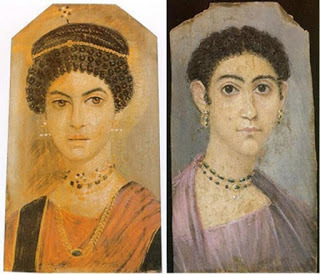

Mummy portraits, or at least Roman or Greek style funerary masks, were preferred over Egyptian style mummy masks. But plaster masks in the Greek/Roman style were apparently the favorite option for the elite.

Fayum mummy portraits of two women. (Left: Public Domain and Right: Public Domain)

By this time, coffins had largely become nothing more elaborate than simple boxes, but mummification became more popular. Multiple burials were also more common for people of all levels of society.

Clay pots of different shapes and sizes were found in the tombs. (Ministry of Antiquities)

Top Image: The five Roman tombs found at the Beir Al-Shaghala site in the Dakhla Oasis of Egypt's Western Desert. (Ministry of Antiquities) Insert: A funerary mask found in one of the tombs. (Ministry of Antiquities)

By Alicia McDermott

Published on September 11, 2017 01:00

September 10, 2017

Picking Apart the Picts: The Value of Aberdeen's Newest Discovery

Ancient Origins

One of the greatest mysteries of Scotland lies in the northeastern portion of the country. Though named for the Scots because the titular medieval clan won a decisive battle, much of Scotland's history lies in the culture which thrived from the "Dark Ages" up until the medieval period (400-1000AD). This culture is the Picts, and unfortunately, outside of the United Kingdom, the name means little. Yet scholars continue in their determination to uncover the secrets of Pictish life and spread Pictish history beyond the British Isles. Most recently, excavations at Burghead in the northern region of Moray have provided exciting new information of Pictish domesticity.

Historical Clues of the Picts Damaged, Destroyed and Buried

The University of Aberdeen has been examining the site at Burghead since 2015 in the hopes of both learning more about the early medieval civilization, as well as salvaging what remains of the site from developmental damage inflicted in the 19 th century. The current town of Burghead was built atop the Pictish site, and the findings of the Burghead Bulls, Pictish artifacts and an underground well were unfortunately determined less important than the necessity of the new town and subsequent road. Because of this building program, archaeologists have feared that evidence of Pictish life at the site was likely damaged or destroyed, thus preventing archaeologists from examining the town in recent decades.

Archaeological excavations at Burghead uncovered relics of the Picts. Credit: University of Aberdeen

More Than Just Any Pictish Fort

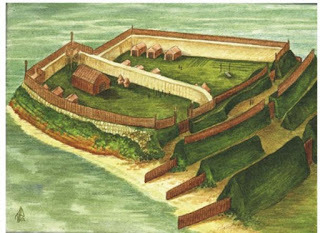

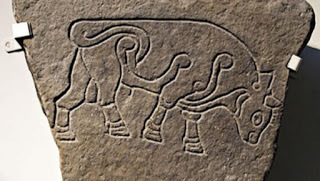

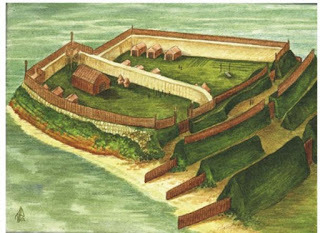

Yet the University of Aberdeen refused to lose hope. There was too much evidence that a treasure of Pictish life might still be buried in the dirt at Burghead. The remains of an upper enclosure, stone revetments and timber ramparts led to a belief that Burghead was more than a just any Pictish fort, but possibly the location of a northern Pictish stronghold called Fortriu. Medieval texts discussed Fortriu as highly valuable to Pictish politics, and the archaeological evidence of the Moray region seemed to indicate the likelihood of its position at Burghead. A minimum of four large stone carvings of Pictish bulls survived the 19 th century renovations of the town, and at least two dozen carvings resembling the Pictish style were uncovered in a pair of caves called Covesea only miles from Burghead. This literary and art historical evidence has long kept scholars from giving up the Pictish scavenger hunt at Burghead. Quite recently, efforts from the University of Aberdeen paid off, revealing the remnants of a Pictish longhouse.

The Pictish fort at Burghead, circa 6th Century AD. Reconstruction of the largest Pictish fort known ( megalithic.co.uk)

Domestic Life in a Royal Complex

The discovery of a domestic space within a royal complex might seem minute to those unfamiliar with excavations or early medieval political spaces. Aberdeen's Dr. Gordon Noble says it best, dictating that finding the longhouse may provide evidence of "how power was materialized within these important fortified sites." A longhouse within the complex of the Pictish leader indicates that the domestic and political spheres were connected, and that separation of the two would likely have been detrimental for reasons heretofore unknown. It is possible that the complex contained storerooms of cereals, grains and other agricultural produce necessary for survival; it might have incorporated an area for butchering animals both for meat and for hides, as seen at the monastery of Portmahomack. Though these two examples are suppositions by this author, the intention of posing the possibility of such undiscovered locations is to accentuate the point that a royal stronghold would have incorporated these more "common" and domicile aspects (and others), whereas a simple fort would have been much less inclusive as it would have not required the same necessities.

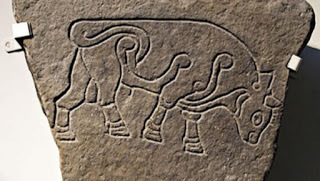

Pictish bull carving, the "Burghead Bull", now in the British Museum ( CC by SA 3.0 )

What the University of Aberdeen has recently done is attempt to preserve the damage of these early discoveries, and search for finds that were not uncovered during the overhaul in the 19 th century and early 20 th centuries. Though the exterior perimeter of the site has been examined in the past, Noble points out that few scholars have attempted to examine the site's interior in recent decades. It was here the Aberdeen team chose to begin, and where the profound discovery of the Pictish longhouse was made a mere two years later. While most details of the Burghead longhouse still remain under wraps, there mere fact of discovery indicates that the secrets of the Picts may yet be buried in Scottish soils, waiting for dedicated archaeologists to strip away their covers and bring them into the light.

Top image: This is the "Celtic Cross" side of a Pictish stone in Aberlemno, Scotland. This stone dates from around 700AD, and the other side of it has some of the mysterious symbols used by the Picts, who lived in this part of Scotland at the time. ( Neil Howard / flickr )

By Riley Winters

One of the greatest mysteries of Scotland lies in the northeastern portion of the country. Though named for the Scots because the titular medieval clan won a decisive battle, much of Scotland's history lies in the culture which thrived from the "Dark Ages" up until the medieval period (400-1000AD). This culture is the Picts, and unfortunately, outside of the United Kingdom, the name means little. Yet scholars continue in their determination to uncover the secrets of Pictish life and spread Pictish history beyond the British Isles. Most recently, excavations at Burghead in the northern region of Moray have provided exciting new information of Pictish domesticity.

Historical Clues of the Picts Damaged, Destroyed and Buried

The University of Aberdeen has been examining the site at Burghead since 2015 in the hopes of both learning more about the early medieval civilization, as well as salvaging what remains of the site from developmental damage inflicted in the 19 th century. The current town of Burghead was built atop the Pictish site, and the findings of the Burghead Bulls, Pictish artifacts and an underground well were unfortunately determined less important than the necessity of the new town and subsequent road. Because of this building program, archaeologists have feared that evidence of Pictish life at the site was likely damaged or destroyed, thus preventing archaeologists from examining the town in recent decades.

Archaeological excavations at Burghead uncovered relics of the Picts. Credit: University of Aberdeen

More Than Just Any Pictish Fort

Yet the University of Aberdeen refused to lose hope. There was too much evidence that a treasure of Pictish life might still be buried in the dirt at Burghead. The remains of an upper enclosure, stone revetments and timber ramparts led to a belief that Burghead was more than a just any Pictish fort, but possibly the location of a northern Pictish stronghold called Fortriu. Medieval texts discussed Fortriu as highly valuable to Pictish politics, and the archaeological evidence of the Moray region seemed to indicate the likelihood of its position at Burghead. A minimum of four large stone carvings of Pictish bulls survived the 19 th century renovations of the town, and at least two dozen carvings resembling the Pictish style were uncovered in a pair of caves called Covesea only miles from Burghead. This literary and art historical evidence has long kept scholars from giving up the Pictish scavenger hunt at Burghead. Quite recently, efforts from the University of Aberdeen paid off, revealing the remnants of a Pictish longhouse.

The Pictish fort at Burghead, circa 6th Century AD. Reconstruction of the largest Pictish fort known ( megalithic.co.uk)

Domestic Life in a Royal Complex

The discovery of a domestic space within a royal complex might seem minute to those unfamiliar with excavations or early medieval political spaces. Aberdeen's Dr. Gordon Noble says it best, dictating that finding the longhouse may provide evidence of "how power was materialized within these important fortified sites." A longhouse within the complex of the Pictish leader indicates that the domestic and political spheres were connected, and that separation of the two would likely have been detrimental for reasons heretofore unknown. It is possible that the complex contained storerooms of cereals, grains and other agricultural produce necessary for survival; it might have incorporated an area for butchering animals both for meat and for hides, as seen at the monastery of Portmahomack. Though these two examples are suppositions by this author, the intention of posing the possibility of such undiscovered locations is to accentuate the point that a royal stronghold would have incorporated these more "common" and domicile aspects (and others), whereas a simple fort would have been much less inclusive as it would have not required the same necessities.

Pictish bull carving, the "Burghead Bull", now in the British Museum ( CC by SA 3.0 )

What the University of Aberdeen has recently done is attempt to preserve the damage of these early discoveries, and search for finds that were not uncovered during the overhaul in the 19 th century and early 20 th centuries. Though the exterior perimeter of the site has been examined in the past, Noble points out that few scholars have attempted to examine the site's interior in recent decades. It was here the Aberdeen team chose to begin, and where the profound discovery of the Pictish longhouse was made a mere two years later. While most details of the Burghead longhouse still remain under wraps, there mere fact of discovery indicates that the secrets of the Picts may yet be buried in Scottish soils, waiting for dedicated archaeologists to strip away their covers and bring them into the light.

Top image: This is the "Celtic Cross" side of a Pictish stone in Aberlemno, Scotland. This stone dates from around 700AD, and the other side of it has some of the mysterious symbols used by the Picts, who lived in this part of Scotland at the time. ( Neil Howard / flickr )

By Riley Winters

Published on September 10, 2017 01:00

September 9, 2017

Poisonings Went Hand in Hand with the Drinking Water in Ancient Pompeii

Ancient Origins

The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced water supply. But the drinking water in the pipelines was probably poisoned on a scale that may have led to daily problems with vomiting, diarrhea, and liver and kidney damage. This is the finding of analyses of water pipe from Pompeii.

"The concentrations were high and were definitely problematic for the ancient Romans. Their drinking water must have been decidedly hazardous to health." This is what a chemist from University of Southern Denmark reveals: Kaare Lund Rasmussen, a specialist in archaeological chemistry. He analyzed a piece of water pipe from Pompeii, and the result surprised both him and his fellow scientists. The pipes contained high levels of the toxic chemical element, antimony.

The result has been published in the journal Toxicology Letters.

Romans Poisoned Themselves

For many years, archaeologists have believed that the Romans' water pipes were problematic when it came to public health. After all, they were made of lead: a heavy metal that accumulates in the body and eventually shows up as damage to the nervous system and organs. Lead is also very harmful to children. So there has been a long-lived thesis that the Romans poisoned themselves to a point of ruin through their drinking water.

Lead water pipe, Roman, 20-47 CE with owner’s name cast into the pipe. The most notable lady Valeria Messalina’ (third wife of the Roman Emperor Claudius) (CC BY 4.0)

"However, this thesis is not always tenable. A lead pipe gets calcified rather quickly, thereby preventing the lead from getting into the drinking water. In other words, there were only short periods when the drinking water was poisoned by lead: for example, when the pipes were laid or when they were repaired: assuming, of course, that there was lime in the water, which there usually was," says Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

Ancient roman lead pipes in Ostia Antica (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Advanced Equipment at SDU

Unlike lead, antimony is acutely toxic. In other words, you react quickly after drinking poisoned water. The element is particularly irritating to the bowels, and the reactions are excessive vomiting and diarrhea that can lead to dehydration. In severe cases, it can also affect the liver and kidneys and, in the worst-case scenario, can cause cardiac arrest.

This new knowledge of alarmingly high concentrations of antimony comes from a piece of water pipe found in Pompeii. -

Or, more precisely, a small metal fragment of 40 mg, which I obtained from my French colleague, Professor Philippe Charlier of the Max Fourestier Hospital, who asked if I would attempt to analyse it. The fact is that we have some particularly advanced equipment at SDU, which enables us to detect chemical elements in a sample and, ever more importantly, to measure where they occur in large concentrations.

Volcano Made it Even Worse

Kaare Lund Rasmussen underlines that he only analyzed this one little fragment of water pipe from Pompeii. It will take several analyses before we can get a more precise picture of the extent, to which Roman public health was affected.

But there is no question that the drinking water in Pompeii contained alarming concentrations of antimony, and that the concentration was even higher than in other parts of the Roman Empire, because Pompeii was located in the vicinity of the volcano, Mount Vesuvius. Antimony also occurs naturally in groundwater near volcanoes.

The lead pipe sample is being analyzed at University of Southern Denmark. Credit: SDU

This is What the Researchers Did

The measurements were conducted on a Bruker 820 Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer.

The sample was dissolved in concentrated nitric acid. 2 ml of the dissolved sample was transferred to a loop and injected as an aerosol in a stream of argon gas which was heated to 6000 degrees C by the plasma.

All the elements in the sample were ionized and transferred as an ion beam into the mass spectrometer. By comparing the measurements against measurements on a known standard the concentration of each element is determined.

Top Image: An original Roman lead waterpipe in Bath, England. Photo: Andrew Dunn/CC BY SA 2.0).

University of Southern Denmark. "Poisonings went hand in hand with the drinking water in ancient Pompeii." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 17 August 2017. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/08...

The article ‘Poisonings went hand in hand with the drinking water in ancient Pompeii’ was originally published on Science Daily and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced water supply. But the drinking water in the pipelines was probably poisoned on a scale that may have led to daily problems with vomiting, diarrhea, and liver and kidney damage. This is the finding of analyses of water pipe from Pompeii.

"The concentrations were high and were definitely problematic for the ancient Romans. Their drinking water must have been decidedly hazardous to health." This is what a chemist from University of Southern Denmark reveals: Kaare Lund Rasmussen, a specialist in archaeological chemistry. He analyzed a piece of water pipe from Pompeii, and the result surprised both him and his fellow scientists. The pipes contained high levels of the toxic chemical element, antimony.

The result has been published in the journal Toxicology Letters.

Romans Poisoned Themselves

For many years, archaeologists have believed that the Romans' water pipes were problematic when it came to public health. After all, they were made of lead: a heavy metal that accumulates in the body and eventually shows up as damage to the nervous system and organs. Lead is also very harmful to children. So there has been a long-lived thesis that the Romans poisoned themselves to a point of ruin through their drinking water.

Lead water pipe, Roman, 20-47 CE with owner’s name cast into the pipe. The most notable lady Valeria Messalina’ (third wife of the Roman Emperor Claudius) (CC BY 4.0)

"However, this thesis is not always tenable. A lead pipe gets calcified rather quickly, thereby preventing the lead from getting into the drinking water. In other words, there were only short periods when the drinking water was poisoned by lead: for example, when the pipes were laid or when they were repaired: assuming, of course, that there was lime in the water, which there usually was," says Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

Ancient roman lead pipes in Ostia Antica (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Advanced Equipment at SDU

Unlike lead, antimony is acutely toxic. In other words, you react quickly after drinking poisoned water. The element is particularly irritating to the bowels, and the reactions are excessive vomiting and diarrhea that can lead to dehydration. In severe cases, it can also affect the liver and kidneys and, in the worst-case scenario, can cause cardiac arrest.

This new knowledge of alarmingly high concentrations of antimony comes from a piece of water pipe found in Pompeii. -

Or, more precisely, a small metal fragment of 40 mg, which I obtained from my French colleague, Professor Philippe Charlier of the Max Fourestier Hospital, who asked if I would attempt to analyse it. The fact is that we have some particularly advanced equipment at SDU, which enables us to detect chemical elements in a sample and, ever more importantly, to measure where they occur in large concentrations.

Volcano Made it Even Worse

Kaare Lund Rasmussen underlines that he only analyzed this one little fragment of water pipe from Pompeii. It will take several analyses before we can get a more precise picture of the extent, to which Roman public health was affected.

But there is no question that the drinking water in Pompeii contained alarming concentrations of antimony, and that the concentration was even higher than in other parts of the Roman Empire, because Pompeii was located in the vicinity of the volcano, Mount Vesuvius. Antimony also occurs naturally in groundwater near volcanoes.

The lead pipe sample is being analyzed at University of Southern Denmark. Credit: SDU

This is What the Researchers Did

The measurements were conducted on a Bruker 820 Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer.

The sample was dissolved in concentrated nitric acid. 2 ml of the dissolved sample was transferred to a loop and injected as an aerosol in a stream of argon gas which was heated to 6000 degrees C by the plasma.

All the elements in the sample were ionized and transferred as an ion beam into the mass spectrometer. By comparing the measurements against measurements on a known standard the concentration of each element is determined.

Top Image: An original Roman lead waterpipe in Bath, England. Photo: Andrew Dunn/CC BY SA 2.0).

University of Southern Denmark. "Poisonings went hand in hand with the drinking water in ancient Pompeii." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 17 August 2017. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/08...

The article ‘Poisonings went hand in hand with the drinking water in ancient Pompeii’ was originally published on Science Daily and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Published on September 09, 2017 00:30

September 8, 2017

The 4 Kingdoms that Dominated Early Medieval England

Made from History

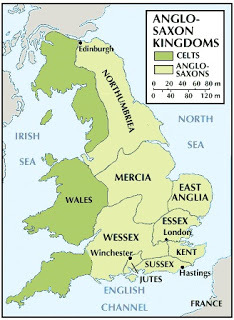

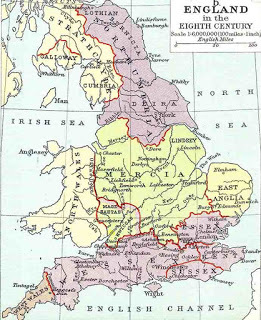

This map shows how Britain was diveded up between the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the Middle Ages

BY CRAIG BESSELL

In the wake of Rome’s withdrawal from Britain in 408 AD the political situation was unstable, no one really had a claim to any particular piece of land. Therefore the person with the biggest army, or more accurately, the largest group of fighting men was able to hold the bigger, more desirable pieces of land. Eventually though some semblance of a political structure grew and boundaries were drawn.

By 650 AD a sporadic patchwork of small kingdoms had been established by strong chieftains who at this point had taken to calling themselves kings of their respective micro-kingdoms. These kingdoms were Bernicia, Deira, Lindsey, East Anglia, Mercia, Wessex and Kent. In time the smaller or less successful kingdoms were absorbed into the others, either through aggression, economic shift or by marriage until a simpler system was revealed. By the eighth century four kingdoms remained, Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia and Wessex.

1. Northumbria

Northumbria was a region that stretched across the neck of northern England and covered much of the east coast and parts of southern Scotland. Modern York was at its southernmost border and Edinburgh at its north. It was formed in the seventh century upon the unification of Bernicia and Deira, the northern and southern parts of the kingdom, respectively. The kingdom was traditionally at odds with Mercia, their neighbouring kingdom. Both consistently raided each others lands and sometimes launched full scale invasions in an attempt to subdue one another.

2. Mercia

Mercia was a large kingdom that covered most of middle England. Its fortunes fluctuated as it was bordered on all sides by potentially hostile rivals. To its north, Northumbria, its west the Welsh kingdoms, traditional enemies of all Anglo-Saxons, to its east, East Anglia and to its south, the least aggressive of its neighbours, Wessex. It was often at war, mainly with Northumbria and Wales, but maintained a largely harmonious relationship with Wessex.

3. Wessex

Wessex was an unstable, but fertile country that covered most of the south west. It was bordered by the Celtic kingdoms of Cornwall to its west, Mercia to its North and Kent to the East. As was the mode of the period Wessex was constantly at odds with its neighbours and actually dwindled as Mercia began to take some its lands before King Egbert rose to power in the 8th century. Its economy and strength grew under Egbert with the acquisition of Surrey, Sussex, Kent and Essex. He took these lands, abolished the kingdom of Kent and established overlord-ship over Mercia and Northumbria. During his reign he established Wessex as the strongest, wealthiest, most civilised of all of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

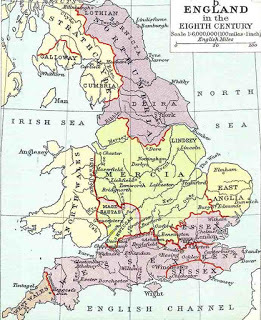

In this map of 8th century Britain you can see the formerly independent states of Kent, Essex and Sussex incorporated into the larger Kingdom of Wessex

4. East-Anglia

East Anglia was the smallest of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, but powerful during the reign of the Wuffingas dynasty. However, by the end of the eighth century it had been subdued by the more powerful Mercia and fell under their rule. East-Anglia briefly claimed independence back in the ninth century before being swiftly conquered and settled by Danish Vikings.

These kingdoms survived for many years, though their borders were often subject to change. Towards the end of the ninth century the whole of Anglo-Saxon Britain faced immense upheaval in the form of invaders from the north, the Vikings. Their invasion would set in motion a series of remarkable events that would bring an end to the separate Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and bring forth one single united Angle-Land.

Published on September 08, 2017 00:30

September 7, 2017

How the Anglo-Saxons Emerged in the 5th Century

Made from History

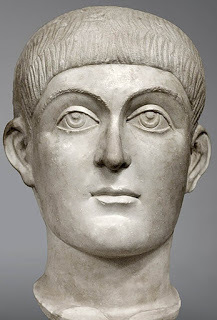

A bust of emperor Honorius (384-423) the last Roman Emperor to control Britain.

BY CRAIG BESSELL

At the turn of the 5th century AD much of the known world was in a state of upheaval as the Roman empire began to splinter and recede. Its outermost borders were neglected as troops were withdrawn from the frontiers to help defend Rome from ‘barbarian’ invasion.

Britain lay at the very edge of the Roman Empire and it was one of the first to suffer from the loss of its imperial defenders. Just over the channel several tribes eyed Britain’s green and now almost completely unprotected shores. It wasn’t long before the first raiders landed.

The End of Roman Britain

The Angles, Jutes, Saxons and other Germanic peoples of north-western Europe began to assail Britain in increasing numbers, the Britons reportedly fought off a sizeable Saxon incursion in 408 AD, but the attacks grew more frequent.

By 410 AD, the native Britons were facing invasions from the north, as the Picts and Scots took advantage of the now unmanned Hadrian’s Wall and all along the eastern and southern coasts from tribes of mainland Europe. More and more invaders landed to pillage or to settle Britain’s fertile lands. The Britons appealed to Emperor Honorius for aid, but all he sent was a message which bid them ‘look to their own defences’. Many historians mark this as the official end of Roman Britain.

The Arrival of the Saxons

What came next was a new period in the county’s history, the reign of the Anglo-Saxons, but how this came about is still subject to disagreement by historians. The traditional assumption was that, without the strong military presence of the Romans, Germanic tribes took swathes of the country by force and behind the invading armies came a massive migration. However, the theory that has become more widely accepted in recent years, due to more comprehensive evidence, is of a more gradual and peaceful merging of the two cultures to form a Germanic, Anglo-Saxon Britain.

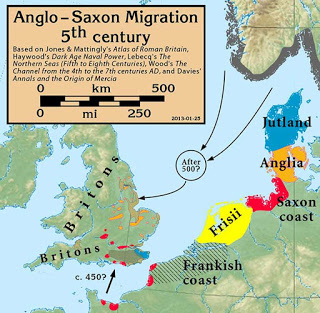

A map indicating the patterns of migration in the 5th century that shaped Anglo-Saxon Britain

Forming a New Identity

There was already a permeation of Germanic culture in many of the trading ports of the south-east of Britain. The prevailing theory now is that a gradual cultural shift occurred in the place of a dwindling Roman presence. The stronger and more immediate Germanic influence, coupled with a gradual migration of smaller groups of mainland Europeans, led to the eventual formation of an Anglo-Saxon Britain, divided into the kingdoms of Mercia, Northumbria, East Anglia and Wessex along with other smaller polities

A map showing the kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England in the 8th Century

That is not to say that there were not skirmishes fought. Records show that some enterprising Saxons, like the aforementioned group in 408 AD, who aimed to take land by force rather than set up a life more peacefully. Some of these raids did succeed, creating a foothold in certain areas of the island of Britain, but there is no evidence to suggest a full scale invasion.

The Anglo-Saxons were therefore a mixture of many different peoples. The Angles and the Saxons, of course, but also other Germanic tribes and Britons. The culture that arose from this eclectic mix predominated in Britain for almost half a millennium.

Published on September 07, 2017 00:30

September 6, 2017

10 Facts About Medieval Knights

Made from History

Tournaments were not the kind of events you’re thinking of.

BY TOM CROPPER

Knights in the Medieval period were pledged to their kings or lieges to carry out military service. In return they were granted a position in court, an estate and/or loot acquired in battle. Knights could either inherit their knighthood or earn it through deeds on the battlefield. But how much much do we know about medieval knights? Here are 10 facts about knights and combat in the Middle Ages.

1. Tournaments were not what you think

We have a clear view of medieval tournaments, but they were not what you’re thinking. Instead they were vast recreations of battles and could last for hours and even days.

2. Tournaments were mass entertainment These tournaments were wildly popular and successful knights became rich and famous. They earned their money by taking another knight hostage for ransom and stealing his horse.

3. William Marshal was the biggest hero in England

William Marshal as played by William Hurt in the movie Robin Hood (2010).

His name has slipped almost into obscurity, but William Marshal was the biggest hero of his day. He was the best tournament knight out there, unseated Richard I in battle, and drove the French away when they invaded. These days you normally get to see him as a bit part character in Robin Hood movies.

4. The longbow came from Wales

The longbow is thought to have been used most effectively by the Welsh before 1066. However, when Edward I sought to put down rebellion in Wales he was so impressed by the skill the Welsh archers ranged against him that he gave them jobs fighting in Scotland.

5. It was hard to become a knight

Becoming a knight was a long process, but could be worth the effort.

Every boy dreamed of becoming a knight, but it was a long road. First of all you’d have to serve seven years as a page followed by seven years as a squire.

6. The Term ‘coup de grace’ originates in the Middle Ages

Two knights coming to blows on the tournament field.

The term coup de grace refers to the final blow delivered to an opponent during a joust.

7. The code of chivalry was real

The classic idea of a Knight taking his vows.

When a man became a knight he took an oath to protect his king, women, the weak and to defend the Church. However, they did not always put this into practice.

8. Women sometimes did the fighting

In true Game of Thrones style some women were pretty handy knights. Countess Petronella of Leicester donned some armour and fought alongside her husband during a rebellion against Henry II. Another damsel, Nicolaa de la Haye, defended Lincoln Castle against the French invaders. With William Marshal, the most famous knight of the time, she fought them off and helped to save England for Edward III.

9. Knights were violent and anything but chivalrous

The idea of chivalry did exist, but it only extended to other knights. In reality there was nothing worse than a bunch of knights with no war to fight. They’d spend their time looting and pillaging and often massacring local villagers just for the pure fun of it.

10. Peasants killed off the knights

The Battle of Crecy where the longbow held the balance of power

When Edward III attacked France in 1337 he brought about a complete change in warfare. While the French had the finest aristocratic knights in the finest armour he scoured the prisons and backstreets for violent soldiers promising pardons if they came to fight. England’s trained longbowmen proved too good for the France’s knights at Crecy, Poitiers and, later, Agincourt.

Rumours about Richard I’s sexuality have persisted since his death.

Tournaments were not the kind of events you’re thinking of.

BY TOM CROPPER

Knights in the Medieval period were pledged to their kings or lieges to carry out military service. In return they were granted a position in court, an estate and/or loot acquired in battle. Knights could either inherit their knighthood or earn it through deeds on the battlefield. But how much much do we know about medieval knights? Here are 10 facts about knights and combat in the Middle Ages.

1. Tournaments were not what you think

We have a clear view of medieval tournaments, but they were not what you’re thinking. Instead they were vast recreations of battles and could last for hours and even days.

2. Tournaments were mass entertainment These tournaments were wildly popular and successful knights became rich and famous. They earned their money by taking another knight hostage for ransom and stealing his horse.

3. William Marshal was the biggest hero in England

William Marshal as played by William Hurt in the movie Robin Hood (2010).

His name has slipped almost into obscurity, but William Marshal was the biggest hero of his day. He was the best tournament knight out there, unseated Richard I in battle, and drove the French away when they invaded. These days you normally get to see him as a bit part character in Robin Hood movies.

4. The longbow came from Wales

The longbow is thought to have been used most effectively by the Welsh before 1066. However, when Edward I sought to put down rebellion in Wales he was so impressed by the skill the Welsh archers ranged against him that he gave them jobs fighting in Scotland.

5. It was hard to become a knight

Becoming a knight was a long process, but could be worth the effort.

Every boy dreamed of becoming a knight, but it was a long road. First of all you’d have to serve seven years as a page followed by seven years as a squire.

6. The Term ‘coup de grace’ originates in the Middle Ages

Two knights coming to blows on the tournament field.

The term coup de grace refers to the final blow delivered to an opponent during a joust.

7. The code of chivalry was real

The classic idea of a Knight taking his vows.

When a man became a knight he took an oath to protect his king, women, the weak and to defend the Church. However, they did not always put this into practice.

8. Women sometimes did the fighting

In true Game of Thrones style some women were pretty handy knights. Countess Petronella of Leicester donned some armour and fought alongside her husband during a rebellion against Henry II. Another damsel, Nicolaa de la Haye, defended Lincoln Castle against the French invaders. With William Marshal, the most famous knight of the time, she fought them off and helped to save England for Edward III.

9. Knights were violent and anything but chivalrous

The idea of chivalry did exist, but it only extended to other knights. In reality there was nothing worse than a bunch of knights with no war to fight. They’d spend their time looting and pillaging and often massacring local villagers just for the pure fun of it.

10. Peasants killed off the knights

The Battle of Crecy where the longbow held the balance of power

When Edward III attacked France in 1337 he brought about a complete change in warfare. While the French had the finest aristocratic knights in the finest armour he scoured the prisons and backstreets for violent soldiers promising pardons if they came to fight. England’s trained longbowmen proved too good for the France’s knights at Crecy, Poitiers and, later, Agincourt.

Rumours about Richard I’s sexuality have persisted since his death.

Published on September 06, 2017 00:30

September 5, 2017

2,000-Year-Old Tombs and Sarcophagi Uncovered in Hidden Burial Chambers in Egypt

Ancient Origins

A team of archaeologists has discovered three tombs dating back 2,000 years in southern Egypt. The three new discoveries in El-Kamin El-Sahrawi point to a large cemetery covering the 27th Dynasty and the Greco-Roman period.

Millennia Old Tombs Discovered

The Ministry of Antiquities of Egypt announced yesterday that three rock-hewn tombs from the Ptolemaic era have been unearthed during excavations in the El-Kamin El-Sahrawi area as Ahram Online reports. An Egyptian archaeological mission from the Ministry of Antiquities working in the area to the south-east of the town of Samalout, was the one making the important discovery and according to their reports the tomb contain several sarcophagi and a collection of clay fragments.

Ayman Ashmawy, head of the ministry's Ancient Egyptian Sector, stated as Ahram Online reports that after the close examination of the clay fragments, the team of archaeologists and experts concluded that the tombs date between the 27th Dynasty, founded in 525BC, and the Greco-Roman era, which began in 332BC. "This fact suggests that the area was a large cemetery over a long period of time," Ashmawy said.

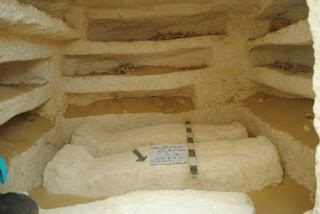

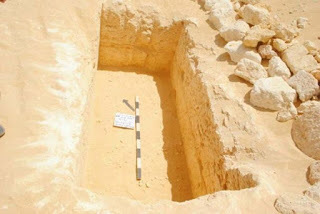

One of the recently discovered burial chambers (Photo: Nevine El-Aref)

Discovery of Great Importance

Ashmawy described the discovery as "very important" due to the fact that it will shed light on many things we previously didn’t know about the El-Kamil El-Sahrawi archaeological site. Ashmawy also added that during previous excavation works, the archaeological team unearthed nearly twenty tombs that were built in the catacomb architectural style, which covers a vast period starting from the 27th Dynasty (also known as First Egyptian Satrapy) and the Greco-Roman era. “The three newly discovered tombs have a different architectural design from the previous ones,” Ali El-Bakry, head of the excavation mission, told Ahram Online.

According to Ali El-Bakry’s reports, the first tomb is composed of a perpendicular burial shaft engraved in rock and leading to a burial chamber containing four sarcophagi which had been carved with human faces. Nine burial holes were also discovered inside. The second tomb is composed of a perpendicular burial shaft as well and two burial chambers. The first chamber is positioned to the north and runs from east to west, “with the remains of two sarcophagi, suggesting that it was for the burial of two people,” Ali El-Bakry tells Ahram Online.

Burial of a Small Child Discovered for the First Time in the Area

The archaeological mission also discovered a collection of six burial holes, including one of a small child. “These tombs were part of a large cemetery for a large city and not a military garrison as some suggest. This was the first time to find a burial of a child at the Sahrawi site,” Ali El-Bakry said as Independent reports, pointing out that human remains and other evidence indicate the presence of men, women and children of different ages being buried there. Furthermore, Ali El-Bakry said that the second room is located at the end of the shaft and does not contain anything of archaeological value except the remains of a wooden coffin, while excavation works at the third tomb have not yet been finished.

Burial hole and sarcophagus of a child (Photo: Nevine El-Aref)

Undergoing Works to Reveal More Secrets Soon

The excavation works were officially launched in 2015 when the archaeological mission uncovered an assembly of five sarcophagi of different shapes and sizes, as well as the remains of a wooden sarcophagus. The second phase of the excavation was launched in October 2016, with five tombs being discovered during the works. As Ahram Online reported, four of them have almost identical interior designs, while the fifth consists of a burial shaft. Ultimately, Ali El-Bakry reassured that excavation works and the examination of the finds will continue intensively in order to reveal more secrets of the site’s history.

Top image: One of the newly discovered sarcophagi (Photo: Nevine El-Aref)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on September 05, 2017 01:30