MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 49

August 5, 2017

The Hidden History of Roman London

Made From History

BY GRAHAM LAND

The Romans founded London as Londinium in 47 AD, later building a bridge over the River Thames and establishing the settlement as a port with roads leading to other outposts in Roman Britain.

As the largest Roman city in Britannia, London remained under Rome’s authority until 410 AD, a very substantial stretch of time.

The Origins of London Though Londinium began as a small fortified settlement, after it was demolished by a massive force of native tribes led by Queen Boudica in 60 AD, it was rebuilt as a planned Roman town and expanded rapidly.

Around 50 years after its founding London was home to some 60,000 inhabitants.

Life in Londinium

A model depicting life in Roman London during 85-90 AD. Credit: Steven G. Johnson (Wikimedia Commons)

Though Romanised, most of the population of London were native Britons, including soldiers, families, labourers, tradesmen, sailors and slaves. For the average Londoner, life was tough, though there were relaxing pursuits imported by Rome, including bathhouses, taverns and amphitheatres. People could also unwind during the many Roman festivals celebrated in the city.

Religion in Roman London

One of London’s most significant archaeological finds dating from Roman times is a temple to the Persian God Mithras, the London Mithraeum, uncovered in 1954. The cult of Mithras, though not Roman or Hellenistic in origin, was popular in the Empire for a time.

For the most part, however, Londoners worshiped the gods of the Romans, which were mostly derived from the Greek pantheon. In the late period of occupation Christianity began to make inroads.

Finds from the London Temple of Mithras in the Museum of London. Credit: Carole Raddato (Wikimedia Commons)

Decline and Fall

Londinium was at its peak in the 2nd century when Emperor Hadrian visited on one of his many travels around the Empire. But by the next century, things were headed downhill. Instability and economic troubles of the Empire increased the city’s vulnerability to Barbarian raids and pirate attacks.

Around 200 AD a defensive wall was built, encircling the city. The population dwindled over the following 200 years.

By the 4th century, public buildings were demolished (maybe due to a rebellion) and the settlement south of the Thames was abandoned. By 407 Emperor Constantine II withdrew all forces from the city and subsequently Emperor Honorius left London’s defence to the Britons.

While some aspects of Roman culture and lifestyle remained, particularly among the wealthy classes, officially London was Roman-less.

Roman London Today

London has maintained a population for over 1,600 years since the Romans left. Time, the elements, demolitions and construction have long removed most visible features of old Londinium. Yet much remains, buried underground and in urban features that survived throughout the years, such as roads that were continually repaved or the odd building foundation.

A surviving remnant of the Roman Wall at Tower Hill. In front is a replica of a statue of Emperor Trajan. Credit: Gene.arboit (Wikimedia Commons)

Some remnants of Roman London can still be seen today, including sections of the Roman Wall at Tower Hill, the Barbican Estate and on the grounds of the Museum of London.

Excavations throughout the years have also exposed much of the city’s Latin past, like the Roman house at Billingsgate (uncovered in 1848) and the 2013 discovery of entire Roman streets and countless well-preserved artefacts at the building site of Bloomberg Place in London’s financial district. A Roman ship was found in the Thames in 1963.

Small artefacts like Roman pottery, statuettes and coins, even brothel tokens, are still routinely found in the city’s main river.

Published on August 05, 2017 00:30

August 4, 2017

Sam’s historical recipe corner: Vanilla ice cream

History Extra

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates vanilla ice cream - a dessert enjoyed by an 18th-century US president.

US president Thomas Jefferson’s love of ice cream is well documented, and led to its huge popularity in the US. Jefferson was in France between 1784 and 1789 and brought back lots of exciting recipes – pigs’ feet, fruit tarts, peach flambe – including this recipe. His hand-written ice cream recipe – the first of its kind in the US – still survives today.

Traditionally ice cream would have been frozen using a salt and ice technique. I’ve included this method for those readers who fancy trying some fun food chemistry.

Ingredients

• 6 egg yolks

• 2 pints of cream (I used 1 of single and 1 of double)

• 250g caster sugar

• pinch salt

• 2 tsp of vanilla or one vanilla pod

• ice and salt (if you’re using this freezing method)

Method

Beat the egg yolks until they are thick and a pale yellow colour. Add the sugar and a pinch of salt.

Pour the cream into a pan and bring to the boil. Take off the heat and slowly pour into the beaten egg mixture. Put over a pan of simmering water (or bain-marie) and let it slowly thicken until it has the consistency of custard.

Strain the mixture through a fine sieve into a bowl. Add the vanilla and allow to cool.

Freezing using ice and salt: You’ll need a plastic tub with a lid for the ice cream, and a larger container (a small bucket is ideal) for the crushed ice and salt (three parts ice to one part salt). Put the ice cream tub into the ice and salt mixture and shake every hour or so to stop ice crystals forming. The ice and salt should react, drawing heat away and freezing the ice cream more quickly.

Freezing using a freezer: Put the tub of ice cream mix in the freezer and after around an hour give it a really good mix to get rid of any ice crystals. Continue to whisk every hour or so until the ice cream has set.

Verdict

I did try the ice and salt method but I must have got my ratios wrong as it didn’t seem to set – that, or I was getting a bit impatient! I ended up popping the mix into the freezer and stirring periodically. The result was worth all the effort, though: a really indulgent vanilla treat.

Difficulty: 5/10

Time (including freezing): 6 hours

Recipe courtesy of DigVentures

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates vanilla ice cream - a dessert enjoyed by an 18th-century US president.

US president Thomas Jefferson’s love of ice cream is well documented, and led to its huge popularity in the US. Jefferson was in France between 1784 and 1789 and brought back lots of exciting recipes – pigs’ feet, fruit tarts, peach flambe – including this recipe. His hand-written ice cream recipe – the first of its kind in the US – still survives today.

Traditionally ice cream would have been frozen using a salt and ice technique. I’ve included this method for those readers who fancy trying some fun food chemistry.

Ingredients

• 6 egg yolks

• 2 pints of cream (I used 1 of single and 1 of double)

• 250g caster sugar

• pinch salt

• 2 tsp of vanilla or one vanilla pod

• ice and salt (if you’re using this freezing method)

Method

Beat the egg yolks until they are thick and a pale yellow colour. Add the sugar and a pinch of salt.

Pour the cream into a pan and bring to the boil. Take off the heat and slowly pour into the beaten egg mixture. Put over a pan of simmering water (or bain-marie) and let it slowly thicken until it has the consistency of custard.

Strain the mixture through a fine sieve into a bowl. Add the vanilla and allow to cool.

Freezing using ice and salt: You’ll need a plastic tub with a lid for the ice cream, and a larger container (a small bucket is ideal) for the crushed ice and salt (three parts ice to one part salt). Put the ice cream tub into the ice and salt mixture and shake every hour or so to stop ice crystals forming. The ice and salt should react, drawing heat away and freezing the ice cream more quickly.

Freezing using a freezer: Put the tub of ice cream mix in the freezer and after around an hour give it a really good mix to get rid of any ice crystals. Continue to whisk every hour or so until the ice cream has set.

Verdict

I did try the ice and salt method but I must have got my ratios wrong as it didn’t seem to set – that, or I was getting a bit impatient! I ended up popping the mix into the freezer and stirring periodically. The result was worth all the effort, though: a really indulgent vanilla treat.

Difficulty: 5/10

Time (including freezing): 6 hours

Recipe courtesy of DigVentures

Published on August 04, 2017 01:30

August 3, 2017

Pompeii: A Snapshot of Ancient Roman Life

BY GRAHAM LAND

Made From History

In August of 79 AD Mount Vesuvius erupted, covering the Roman city of Pompeii in 4 – 6 metres of pumice and ash. The nearby town of Herculaneum met a similar fate.

Of the 11,000-strong population at the time, it is estimated that only around 2,000 survived the first eruption, while most of the rest perished in the second, which was even more powerful. The preservation of the site was so extensive because rain mixed with the fallen ash and formed a sort of epoxy mud, which then hardened.

What was a large-scale natural disaster for the ancient residents of Pompeii turned out to be a miracle in archaeological terms, due to the incredible conservation of the city.

Ash moulds preserved human forms at the time of death. Credit: Sören Bleikertz (Wikimedia Commons)

Written Records of Pompeii

You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, and the shouting of men; some were calling their parents, others their children or their wives, trying to recognise them by their voices. People bewailed their own fate or that of their relatives, and there were some who prayed for death in their terror of dying. Many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness for evermore.

—Pliny the Younger

Before the rediscovery of the site in 1599, the city and its destruction were known only through written records. Both Pliny the Elder and his nephew Pliny the Younger wrote about the eruption of Vesuvius and the death of Pompeii. Pliny the Elder described seeing a large cloud from across the bay, and as a commander in the Roman Navy, embarked on a nautical exploration of the area. He ultimately died, probably from inhaling sulphuric gases and ash.

Pliny the Younger’s letters to the historian Tacitus relate the first and second eruptions as well as the death of his uncle. He describes residents struggling to escape the waves of ash and how the rains later mixed with the fallen ash.

An Incredible Window into Ancient Roman Culture

A house in Pompeii. Credit: Sean Hayford O’Leary (Wikimedia Commons)

Though much about Ancient Roman culture and society was recorded in art and the written word, these media are purposeful, thought-out ways of transmitting information. Contrastingly, the disaster at Pompeii and Herculaneum provides a spontaneous and accurate 3-dimensional snapshot of ordinary life in a Roman city.

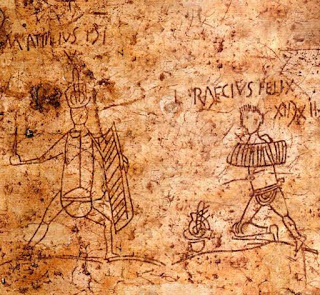

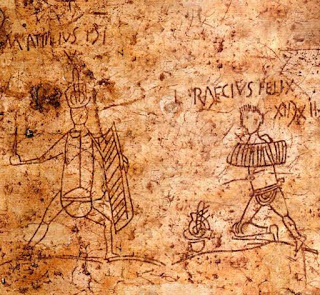

Thanks to the temperamental geological nature of Vesuvius, ornate paintings and gladiator graffiti alike have been preserved for two millennia. The city’s taverns, brothels, villas and theatres were captured in time. Bread was even sealed in bakery ovens. There is simply no archaeological parallel to Pompeii as nothing comparable has survived in such a way or for such a long time, which so accurately preserves the lives of ordinary ancient people.

Most, if not all, the buildings and artefacts of Pompeii would have been lucky to last 100 years if not for the eruption. Instead they have survived for nearly 2,000.

What Survived in Pompeii?

Examples of preservation at Pompeii include such diverse treasures as the Temple of Isis and a complementary wall painting depicting how the Egyptian goddess was worshiped there; a large collection of glassware; animal-powered rotary mills; practically intact houses; a remarkably well-conserved forum baths and even carbonised chicken eggs.

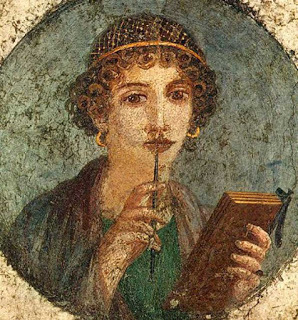

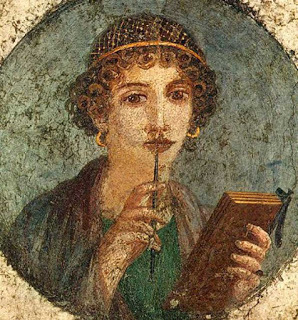

A fresco shows a young woman holding a stylus and wooden tablets

Paintings range from a series of erotic frescos to a fine depiction of a young woman writing on wooden tablets with a stylus, a banquet scene and a baker selling bread. A somewhat more crude painting, though just as valuable in terms of history and archaeology, is from a city tavern and shows men engaging in gameplay.

A Remnant of the Ancient Past Faces an Uncertain Future

While the ancient site is still being excavated, it is more vulnerable to damage than it was all those years buried under ash. UNESCO has expressed concerns that the Pompeii site has suffered from vandalism and a general decline due to poor upkeep and a lack of protection from the elements.

Though most of the frescos have been rehoused in museums, the architecture of the city remains exposed and requires safeguarding as it is a treasure not just of Italy, but of the world.

Pompeiian gladiator graffiti

Made From History

In August of 79 AD Mount Vesuvius erupted, covering the Roman city of Pompeii in 4 – 6 metres of pumice and ash. The nearby town of Herculaneum met a similar fate.

Of the 11,000-strong population at the time, it is estimated that only around 2,000 survived the first eruption, while most of the rest perished in the second, which was even more powerful. The preservation of the site was so extensive because rain mixed with the fallen ash and formed a sort of epoxy mud, which then hardened.

What was a large-scale natural disaster for the ancient residents of Pompeii turned out to be a miracle in archaeological terms, due to the incredible conservation of the city.

Ash moulds preserved human forms at the time of death. Credit: Sören Bleikertz (Wikimedia Commons)

Written Records of Pompeii

You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, and the shouting of men; some were calling their parents, others their children or their wives, trying to recognise them by their voices. People bewailed their own fate or that of their relatives, and there were some who prayed for death in their terror of dying. Many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness for evermore.

—Pliny the Younger

Before the rediscovery of the site in 1599, the city and its destruction were known only through written records. Both Pliny the Elder and his nephew Pliny the Younger wrote about the eruption of Vesuvius and the death of Pompeii. Pliny the Elder described seeing a large cloud from across the bay, and as a commander in the Roman Navy, embarked on a nautical exploration of the area. He ultimately died, probably from inhaling sulphuric gases and ash.

Pliny the Younger’s letters to the historian Tacitus relate the first and second eruptions as well as the death of his uncle. He describes residents struggling to escape the waves of ash and how the rains later mixed with the fallen ash.

An Incredible Window into Ancient Roman Culture

A house in Pompeii. Credit: Sean Hayford O’Leary (Wikimedia Commons)

Though much about Ancient Roman culture and society was recorded in art and the written word, these media are purposeful, thought-out ways of transmitting information. Contrastingly, the disaster at Pompeii and Herculaneum provides a spontaneous and accurate 3-dimensional snapshot of ordinary life in a Roman city.

Thanks to the temperamental geological nature of Vesuvius, ornate paintings and gladiator graffiti alike have been preserved for two millennia. The city’s taverns, brothels, villas and theatres were captured in time. Bread was even sealed in bakery ovens. There is simply no archaeological parallel to Pompeii as nothing comparable has survived in such a way or for such a long time, which so accurately preserves the lives of ordinary ancient people.

Most, if not all, the buildings and artefacts of Pompeii would have been lucky to last 100 years if not for the eruption. Instead they have survived for nearly 2,000.

What Survived in Pompeii?

Examples of preservation at Pompeii include such diverse treasures as the Temple of Isis and a complementary wall painting depicting how the Egyptian goddess was worshiped there; a large collection of glassware; animal-powered rotary mills; practically intact houses; a remarkably well-conserved forum baths and even carbonised chicken eggs.

A fresco shows a young woman holding a stylus and wooden tablets

Paintings range from a series of erotic frescos to a fine depiction of a young woman writing on wooden tablets with a stylus, a banquet scene and a baker selling bread. A somewhat more crude painting, though just as valuable in terms of history and archaeology, is from a city tavern and shows men engaging in gameplay.

A Remnant of the Ancient Past Faces an Uncertain Future

While the ancient site is still being excavated, it is more vulnerable to damage than it was all those years buried under ash. UNESCO has expressed concerns that the Pompeii site has suffered from vandalism and a general decline due to poor upkeep and a lack of protection from the elements.

Though most of the frescos have been rehoused in museums, the architecture of the city remains exposed and requires safeguarding as it is a treasure not just of Italy, but of the world.

Pompeiian gladiator graffiti

Published on August 03, 2017 00:00

August 2, 2017

5 Great Female Warriors of the Ancient World

Made from History

BY GRAHAM LAND

Throughout history, most cultures have considered warfare to be the domain of men. It is only quite recently that female soldiers have participated in modern combat on a large scale. The exception is the Soviet Union, which included female battalions and pilots during the First World War and saw hundreds of thousands of women soldiers fight in World War Two.

In the major ancient civilisations, the lives of women were generally restricted to the most traditional roles, with a few notable exceptions. Yet there were some who broke with tradition and even achieved military greatness.

Here are 5 of history’s fiercest warriors who not only had to face their enemies, but also the strict gender roles of their day.

The tomb of Fu Hao. Credit: Chris Gyford (Wikimedia Commons)

Lady Fu Hao was one of the 60 wives of Emperor Wu Ding of ancient China’s Shang Dynasty. She broke with tradition by serving as both a high priestess and military general. According to inscriptions on oracle bones from the time, Fu Hao led many military campaigns, commanded 13,000 soldiers and was considered the most powerful military leader of her time.

The many weapons found in her tomb support Fu Hao’s status as a great military power. She also controlled her own fiefdom on the outskirts of her husband’s empire. Her tomb was unearthed in 1976 and can be visited by the public.

Artemisia I of Caria (fl. 480 BC)

The Ancient Greek Queen of Halicarnassus, Artemisia ruled during the late 5th century BC. She was an ally to the King of Persia, Xerxes I, and fought for him during the second Persian invasion of Greece, personally commanding 5 ships at the Battle of Salamis.

Herodotus writes that she was a decisive and intelligent, albeit ruthless strategist. According to Polyaenus, Xereses praised Artemisia above all other officers in his fleet and rewarded her for her performance in battle.

Boudica (d. 60/61 AD)

Queen of the British Celtic Icini tribe, Boudica led an uprising against the forces of the Roman Empire in Britain after the Romans ignored her husband Prasutagus’ will, which left rule of his kingdom to both Rome and his daughters. Upon Prasutagus’ death, the Romans seized control, flogged Boudica and had her daughters raped.

Boudica led an army of Icini and Trinovantes, and destroyed Camulodinum (Colchester), Verulamium (St. Albans) and Londinium (London) before finally being defeated by the Romans.

Triệu Thị Trinh (ca. 222 – 248 AD)

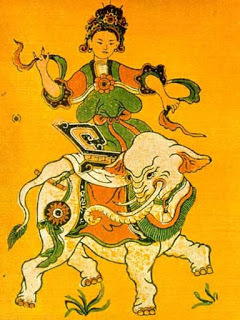

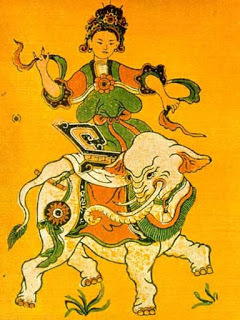

Triệu Thị Trinh

Commonly referred to as Lady Triệu, this warrior of 3rd century Vietnam temporarily freed her homeland from Chinese rule. That is according to traditional Vietnamese sources at least, which also state that she 9 feet tall with 3-foot breasts that she tied behind her back during battle. She usually fought while riding an elephant.

Chinese historical sources make no mention of Triệu Thị Trinh, yet for the Vietnamese, Lady Triệu is the most important historical figure of her time.

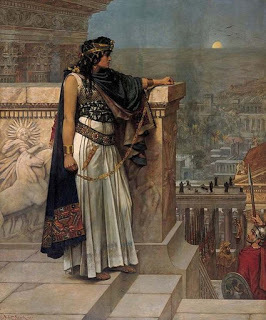

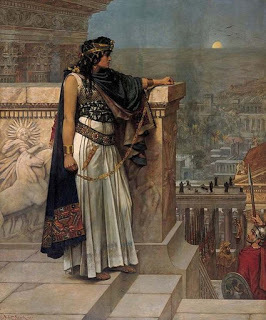

Zenobia (240 – c. 275 AD)

The Queen of Syria’s Palmyrene Empire from 267 AD, Zenobia conquered Egypt from the Romans only 2 years into her reign. Her empire only lasted a short while longer, however, as the Roman Emperor Aurelian defeated her in 271, taking her back to Rome where she — depending on which account you believe — either died shortly thereafter or married a Roman governor and lived out a life of luxury as a well-known philosopher, socialite and matron.

Dubbed the ‘Warrior Queen’, Zenobia was well educated and multi-lingual. She was known to behave ‘like a man’, riding, drinking and hunting with her officers.

Queen Zenobia’s Last Look Upon Palmyra by Herbert Gustave Schmalz

BY GRAHAM LAND

Throughout history, most cultures have considered warfare to be the domain of men. It is only quite recently that female soldiers have participated in modern combat on a large scale. The exception is the Soviet Union, which included female battalions and pilots during the First World War and saw hundreds of thousands of women soldiers fight in World War Two.

In the major ancient civilisations, the lives of women were generally restricted to the most traditional roles, with a few notable exceptions. Yet there were some who broke with tradition and even achieved military greatness.

Here are 5 of history’s fiercest warriors who not only had to face their enemies, but also the strict gender roles of their day.

The tomb of Fu Hao. Credit: Chris Gyford (Wikimedia Commons)

Lady Fu Hao was one of the 60 wives of Emperor Wu Ding of ancient China’s Shang Dynasty. She broke with tradition by serving as both a high priestess and military general. According to inscriptions on oracle bones from the time, Fu Hao led many military campaigns, commanded 13,000 soldiers and was considered the most powerful military leader of her time.

The many weapons found in her tomb support Fu Hao’s status as a great military power. She also controlled her own fiefdom on the outskirts of her husband’s empire. Her tomb was unearthed in 1976 and can be visited by the public.

Artemisia I of Caria (fl. 480 BC)

The Ancient Greek Queen of Halicarnassus, Artemisia ruled during the late 5th century BC. She was an ally to the King of Persia, Xerxes I, and fought for him during the second Persian invasion of Greece, personally commanding 5 ships at the Battle of Salamis.

Herodotus writes that she was a decisive and intelligent, albeit ruthless strategist. According to Polyaenus, Xereses praised Artemisia above all other officers in his fleet and rewarded her for her performance in battle.

Boudica (d. 60/61 AD)

Queen of the British Celtic Icini tribe, Boudica led an uprising against the forces of the Roman Empire in Britain after the Romans ignored her husband Prasutagus’ will, which left rule of his kingdom to both Rome and his daughters. Upon Prasutagus’ death, the Romans seized control, flogged Boudica and had her daughters raped.

Boudica led an army of Icini and Trinovantes, and destroyed Camulodinum (Colchester), Verulamium (St. Albans) and Londinium (London) before finally being defeated by the Romans.

Triệu Thị Trinh (ca. 222 – 248 AD)

Triệu Thị Trinh

Commonly referred to as Lady Triệu, this warrior of 3rd century Vietnam temporarily freed her homeland from Chinese rule. That is according to traditional Vietnamese sources at least, which also state that she 9 feet tall with 3-foot breasts that she tied behind her back during battle. She usually fought while riding an elephant.

Chinese historical sources make no mention of Triệu Thị Trinh, yet for the Vietnamese, Lady Triệu is the most important historical figure of her time.

Zenobia (240 – c. 275 AD)

The Queen of Syria’s Palmyrene Empire from 267 AD, Zenobia conquered Egypt from the Romans only 2 years into her reign. Her empire only lasted a short while longer, however, as the Roman Emperor Aurelian defeated her in 271, taking her back to Rome where she — depending on which account you believe — either died shortly thereafter or married a Roman governor and lived out a life of luxury as a well-known philosopher, socialite and matron.

Dubbed the ‘Warrior Queen’, Zenobia was well educated and multi-lingual. She was known to behave ‘like a man’, riding, drinking and hunting with her officers.

Queen Zenobia’s Last Look Upon Palmyra by Herbert Gustave Schmalz

Published on August 02, 2017 01:30

August 1, 2017

Frontiers of the Roman Empire: Dividing Us From Them

Made From History

BY COLIN RICKETTS

The Roman Empire became very cosmopolitan, containing many races and cultures and granting limited citizenship to many conquered people. However, there was still a strong sense of ‘us and them’ in Roman society – hierarchically between citizen and slave, and geographically between the civilised and the barbarian. The Empire’s frontiers were simple military barriers, but also a dividing line between two ways of life, keeping one safe from the other.

The Limits of the Empire

As Rome expanded out of Italy from the 2nd century BC, there was no force capable of stopping its legions. It’s also important to note that conquest wasn’t always a straight-forward military matter. Rome traded and talked with neighbouring peoples, often having client kings in place before the troops went in. And the Empire – civilised, peaceful, prosperous – was an attractive system to join.

Everything has limits though and Rome found its in the early 2nd century AD. The subsequent problems in enforcing central power and the eventual splitting of the Empire into as many as four parts suggests that this territory was already too much to manage successfully. Some historians argue that the limit was military, marking a boundary between cultures that fight on foot and the masters of cavalry warfare whom Rome could not defeat.

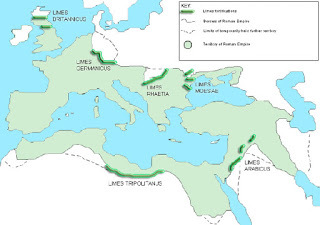

The Empire at its largest extent, at Trajan’s death in 117 AD.

Many of the Empire’s boundaries were natural. For example, in North Africa it was the northern edge of the Sahara. In Europe, the Rhine and Danube rivers provided stable eastern borders for long periods; in the Middle East it was the Euphrates.

The Last Outpost

The Romans also built great frontiers. These were called limes, the Latin word which is the root for our ‘limits’. They were considered the edge of defensible territory and Roman power, and there was an understanding that only exceptional circumstances justified going beyond them. Soldiers sometimes mutinied when they felt the limes were preventing them from doing their job, and were often rewarded with an expedition to sort out whichever uppity tribe had provoked them.

The nature of the defences varied from place to place. Hadrian’s Wall, marking the northern edge of the Empire in Britannia, was the most impressive, with its high stone walls and well-designed and built forts. In Germania, the limes started as an area of felled forest, like a fire break with wooden watch towers. A wooden fence was later added and more forts built. In Arabia, there was no barrier. An important road built by Trajan marked the boundary and forts were built at regular intervals and around the easiest invasion routes from the desert.

Even at their most imposing the limes could be a little porous. Trade was allowed, and people north of Hadrian’s Wall were being taxed to some extent. In fact, the borders of the Empire were commercial hotspots.

The Limes: Rome’s Imperial Borders

The best known and preserved limes are:

Hadrian’s Wall

From the Solway Firth to Wallsend on the River Tyne in the north of the UK, this 117.5-km wall was 6 metres tall in places. A ditch protected the north of the wall while a road to the south helped troops get about quickly. Small mile castles were supplemented with major forts at larger intervals. It only took six years to build. The Antonine Wall further north wasn’t a manned frontier for long.

The Limes Germanicus

This line was built from 83 AD and stood firm until around 260 AD. They ran from the Rhine’s northern estuary to Regensburg on the Danube at their longest, a length of 568 km. Earthworks were supplemented with a palisade fence with walls being built later in parts. There were 60 major forts and 900 watchtowers along the Limes Germanicus, often in several layers where invaders could mass in large numbers.

The Limes Arabicus

This frontier was 1,500 km long, protecting the province of Arabia. Trajan built the Via Nova Traiana road along several hundred kilometres of its length. Large Forts were placed only at strategic danger points with smaller forts every 100 km or so.

The Limes Tripolitanus

More of a zone than a barrier, this limes defended important cities in Libya, first from the desert Garamantes tribe, who were persuaded that trading with Rome was better than fighting it, and then from nomadic raiders. The first fort was built in 75 AD. As the Limes grew they brought prosperity, with soldiers settling to farm and trade. The boundary survived into the Byzantine Era. Today, the remains of Roman fortifications are some of the best in the world.

Other Limes

—The Limes Alutanus marked the eastern European frontier of the Roman province of Dacia.

—The Limes Transalutanus was the lower-Danube frontier.

—Limes Moesiae ran through modern Serbia along the Danube to Moldavia.

—Limes Norici protected Noricum from the River Inn to the Danube in modern Austria.

—Limes Pannonicus was the boundary of the province of Pannonia in modern Austrian and Serbia.

The British and German limes are already part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site and more will be added in time.

BY COLIN RICKETTS

The Roman Empire became very cosmopolitan, containing many races and cultures and granting limited citizenship to many conquered people. However, there was still a strong sense of ‘us and them’ in Roman society – hierarchically between citizen and slave, and geographically between the civilised and the barbarian. The Empire’s frontiers were simple military barriers, but also a dividing line between two ways of life, keeping one safe from the other.

The Limits of the Empire

As Rome expanded out of Italy from the 2nd century BC, there was no force capable of stopping its legions. It’s also important to note that conquest wasn’t always a straight-forward military matter. Rome traded and talked with neighbouring peoples, often having client kings in place before the troops went in. And the Empire – civilised, peaceful, prosperous – was an attractive system to join.

Everything has limits though and Rome found its in the early 2nd century AD. The subsequent problems in enforcing central power and the eventual splitting of the Empire into as many as four parts suggests that this territory was already too much to manage successfully. Some historians argue that the limit was military, marking a boundary between cultures that fight on foot and the masters of cavalry warfare whom Rome could not defeat.

The Empire at its largest extent, at Trajan’s death in 117 AD.

Many of the Empire’s boundaries were natural. For example, in North Africa it was the northern edge of the Sahara. In Europe, the Rhine and Danube rivers provided stable eastern borders for long periods; in the Middle East it was the Euphrates.

The Last Outpost

The Romans also built great frontiers. These were called limes, the Latin word which is the root for our ‘limits’. They were considered the edge of defensible territory and Roman power, and there was an understanding that only exceptional circumstances justified going beyond them. Soldiers sometimes mutinied when they felt the limes were preventing them from doing their job, and were often rewarded with an expedition to sort out whichever uppity tribe had provoked them.

The nature of the defences varied from place to place. Hadrian’s Wall, marking the northern edge of the Empire in Britannia, was the most impressive, with its high stone walls and well-designed and built forts. In Germania, the limes started as an area of felled forest, like a fire break with wooden watch towers. A wooden fence was later added and more forts built. In Arabia, there was no barrier. An important road built by Trajan marked the boundary and forts were built at regular intervals and around the easiest invasion routes from the desert.

Even at their most imposing the limes could be a little porous. Trade was allowed, and people north of Hadrian’s Wall were being taxed to some extent. In fact, the borders of the Empire were commercial hotspots.

The Limes: Rome’s Imperial Borders

The best known and preserved limes are:

Hadrian’s Wall

From the Solway Firth to Wallsend on the River Tyne in the north of the UK, this 117.5-km wall was 6 metres tall in places. A ditch protected the north of the wall while a road to the south helped troops get about quickly. Small mile castles were supplemented with major forts at larger intervals. It only took six years to build. The Antonine Wall further north wasn’t a manned frontier for long.

The Limes Germanicus

This line was built from 83 AD and stood firm until around 260 AD. They ran from the Rhine’s northern estuary to Regensburg on the Danube at their longest, a length of 568 km. Earthworks were supplemented with a palisade fence with walls being built later in parts. There were 60 major forts and 900 watchtowers along the Limes Germanicus, often in several layers where invaders could mass in large numbers.

The Limes Arabicus

This frontier was 1,500 km long, protecting the province of Arabia. Trajan built the Via Nova Traiana road along several hundred kilometres of its length. Large Forts were placed only at strategic danger points with smaller forts every 100 km or so.

The Limes Tripolitanus

More of a zone than a barrier, this limes defended important cities in Libya, first from the desert Garamantes tribe, who were persuaded that trading with Rome was better than fighting it, and then from nomadic raiders. The first fort was built in 75 AD. As the Limes grew they brought prosperity, with soldiers settling to farm and trade. The boundary survived into the Byzantine Era. Today, the remains of Roman fortifications are some of the best in the world.

Other Limes

—The Limes Alutanus marked the eastern European frontier of the Roman province of Dacia.

—The Limes Transalutanus was the lower-Danube frontier.

—Limes Moesiae ran through modern Serbia along the Danube to Moldavia.

—Limes Norici protected Noricum from the River Inn to the Danube in modern Austria.

—Limes Pannonicus was the boundary of the province of Pannonia in modern Austrian and Serbia.

The British and German limes are already part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site and more will be added in time.

Published on August 01, 2017 00:30

July 31, 2017

Archaeologists unearth 2,700-year old reservoir in Israel

Fox News

Israeli archaeologists digging near the city of Rosh Ha-Ayin have uncovered a remarkably large 2,700-year-old water system surrounded by wall engravings that dates back to the end of the Iron Age.

The system, which includes a 13-foot-deep reservoir that is 66 feet long, was built beneath a large structure with walls that extended nearly 164 feet, the Israel Antiquities Authority announced last week. Its size suggests that it was an administrative site built to control the region’s water supply.

“The structure exposed in this excavation is different from most of the previously discovered farmsteads,” said Gilad Itach, director of excavations for the IAA, in a statement. “Its orderly plan, vast area, strong walls and the impressive water reservoir hewn beneath it suggest that the site was administrative in nature and it may well have controlled the surrounding farmsteads.”

On the floor next to the reservoir, the archeologists found broken ceramic pieces that they believe are fragments of vessels that were used to draw water.

“It is difficult not to be impressed by the sight of the immense underground reservoir quarried out so many years ago,” Itach said. “In antiquity, rainwater collection and storage was a fundamental necessity. With an annual rainfall of 500 millimeters (20 inches), the region’s winter rains would easily have filled the huge reservoir.

“On its walls, near the entrance, we identified engravings of human figures, crosses and a vegetal motif that were probably carved by passersby in a later period. Overall, we identified seven figures measuring 15–30 centimeters (6-12 inches). Most have outstretched arms, and a few appear to be holding some kind of object.”

The site is being excavated ahead of the construction of a residential neighborhood outside Rosh Ha-Ayin, 14 miles east of Tel Aviv.

The excavators were assisted by high school students majoring in the Education Ministry’s Land of Israel and Archaeology track.

Published on July 31, 2017 02:00

July 30, 2017

Sam’s historical recipe corner: Chicken Marengo

History Extra

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates a chicken recipe inspired by one of Napoleon’s famous battles.

According to legend, Chicken Marengo was a dish hastily invented by Napoleon’s cook from whatever ingredients he could get hold of, following the French leader’s narrow victory at the battle of Marengo in 1800. It was more likely to have been invented in a French restaurant and named after the battle to add to its prestige. There are a number of variations on the recipe, but this one seemed like a relatively simple version.

Ingredients

• 2 skinless chicken breast fillets, each cut into two or three pieces

• 1 tbsp olive oil

• 1 tbsp plain white flour

• 1 medium onion, finely chopped

• 100g mushrooms, sliced

• 150ml dry white wine

• 150ml stock

• 2 garlic cloves, crushed

• 3 tbsp tomato purée

• 1 tsp parsley, finely chopped

• 150g long-grain rice

• 2 eggs

Method

Heat a frying pan and add the oil. Dab the chicken pieces dry with a paper towel and coat thinly with flour. Sauté over a medium heat for five minutes.

Transfer the chicken pieces to a medium-sized, lidded saucepan.

Add the onion and mushrooms to the frying pan and sauté these for around six minutes. Once tender, add to the saucepan. Take the frying pan off the heat and add the wine, before pouring this enriched wine into the saucepan. Add the stock, garlic and tomato purée to the saucepan and stir well. Bring it to the boil and then simmer, covered, for 30 minutes. Remove the lid and simmer for another 30 minutes or until the sauce is reduced. Meanwhile, cook the rice and fry the eggs.

Serve the chicken and sauce on a bed of rice. Sprinkle with parsley and garnish with a fried egg.

Difficulty: 3/10

Time: 90 minutes

Published on July 30, 2017 01:30

July 29, 2017

LIDAR Reveals 2,000-Year-Old Dwellings of Earliest Occupants of an Iron Age Hill Fort

Ancient Origins

A team of archaeologists has detected a conurbation of houses at a hill fort that once hosted some of the earliest occupants of a New Forest town, an area of southern England which includes one of the largest remaining tracts of unenclosed pasture land, heathland and forest in Britain.

East ramparts of the Buckland Rings hilltop fort, Lymington (Public domain)

Research Reveals Significant Archaeological Evidence

Buckland Rings is a spectacular embanked and ditched earthen fortress enclosing six acres within its triple ramparts. Until now, archaeologists have not been able to estimate the hillfort’s age accurately, but this could change very soon. A technologically advanced research at Buckland Rings Iron Age hillfort in Lymington, southern England, has divulged proof of 2,000 year old roundhouses within the fort’s ramparts as Heritage Daily reports. The geophysical research was directed by the New Forest National Park Authority with local volunteers and students from Bournemouth University. Seven pre-historic residences have been determined so far, which according to the experts were once home of hunters and farmers that occupied the lands of what is today Lymington. Archaeologists suggest that these ancient people lived in round wooden dwellings covered with a soil-based mixture and made a living by trading throughout Britain and across the sea.

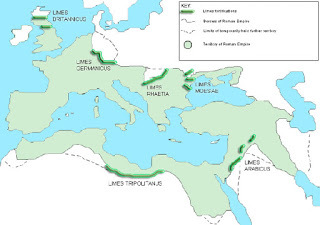

Buckland Rings – artist’s impression, aerial view. (New Forest National Park Authority)

The Utility of Ancient Hillforts in Ancient Britain

As reported in a previous Ancient Origins article, British researchers undertook a large-scale project in 2013, in order to gather information on approximately 5,000 Iron Age hillforts scattered throughout the UK and Ireland. For those who might not know, hillforts are large circular defensive enclosures, protected by one or a series of steep ditches carved out of the earth, and are usually found on prominent hilltop positions, overlooking areas of strategic importance. While they were once thought to have been Roman constructions, archaeological excavations at the end of the 19th century revealed that they were entirely British in nature.

Some hillforts have been traced back to the Bronze Age but the vast majority were constructed in the Iron Age after 500BC. It was once thought that the hillforts had a purely defensive purpose, however, there is evidence to suggest that a wide variety of other activities took place there - domestic, cultural and industrial – suggesting that they functioned like defensible towns, or as administrative centers of a community, home to the local chief and prominent citizens. Interestingly, while hillforts can be found spread throughout the British Isles and Ireland, archaeologists have noticed that they are most prevalent in Southern and Western England.

Archaeologists Examine a Vast Area Covering Six Football Pitches

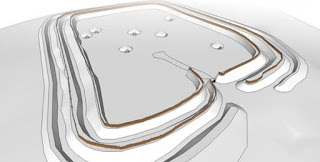

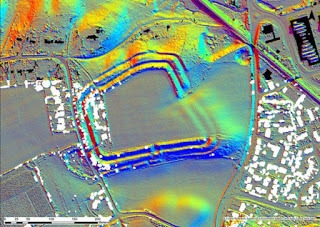

Fast forward to 2017, the team of archaeologists has been using the incredibly revealing Lidar surveying equipment to conduct the recent survey at Buckland Rings Iron Age hillfort in Lymington, has also spotted medieval field systems, which have helped them to understand significantly better the progress and evolution of the Buckland Rings community from prehistoric hamlet to modern day Lymington.

Lidar 3D image of Buckland Rings (New Forest National Park Authority)

The team closely examined a wide area of 4.3 hectares or nearly six football pitches as Heritage Daily characteristically points out, in order to determine disparities in the earth’s soil that show ancient human activity. Lawrence Shaw, Archaeological Officer for the New Forest National Park Authority, told Heritage Daily, “Buckland Rings is a fantastically well preserved hillfort that would have once towered over Lymington and even been visible from the sea. This project has allowed us to look back at the origins of this historic town and see how people were living thousands of years ago. We hope to continue with our research to uncover more details of early Lymington and help the local community to find out more about this fascinating site.”

Ultimately, Josie Hagan, a Bournemouth University archaeology student who participated in the research, told Heritage Daily that the project was not just successful (from an academic point of view), but also fun for the participants, “This survey was a great success and we had a lot of fun over the six days. The volunteers and students worked extremely hard to get a lot of ground covered, and this looks great in the results. It makes it all worthwhile when you get to piece the results together and see features that haven’t been discovered before.”

Top image: Buckland Rings - artist's impression from gates (New Forest National Park Authority)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on July 29, 2017 02:00

July 28, 2017

Race to Recover Elaborate Ancient Roman Mosaics Unearthed in France

Ancient Origins

A team of archaeologists has recently discovered the ruins of an opulent 5th-century Roman palace in Auch, a commune in southwestern France. The team claims to be eager to excavate the site as they battle against time.

Landowner Discovers the Impressive Ruins Accidentally

As the Connexion reports, the newly found palace has been deserted for more than 1,600 years and it was located close to the center of the ancient Roman city of Augusta Auscorum – the capital of the province of Novempopulanie – near the center of the modern French town of Auch. It was discovered by the landowner who was digging foundations to construct a new house. He couldn’t imagine that only 50 cm below the surface he was digging he would discover the amazing 2-metre-deep ruins of an ancient aristocratic Roman palace, which possessed luxurious private baths and remarkable mosaics on the ground.

Excavation of Roman Imperial-era domus in Auch (Credit: © Jean-Louis Bellurget, INRAP)

Archaeologists Have to Race Against Time

Soon after he notified the local archaeological authorities, l’Institut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives (INRAP) has been trying to unravel the huge aristocratic home’s history and background. Additionally, the team of archaeologists doesn’t have much time left for investigation as the land has to be returned to the owner no later than this September. Archaeologists estimate that the ruins date from the first to the fifth century AD, as the building was reconstructed many times. “In the beginning, it was a private habitat. At the time, it was a building with earth walls,” Pascal Lotti, archaeologist at Inrap and scientific leader of the excavation, told Connexion. And added, “In the second century, the cadastre (land registry document) was modified, and in the course of the third century, this great house was set up, which would undergo two major restructurings, as evidenced by the three levels identified by the researchers.”

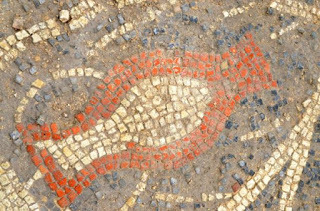

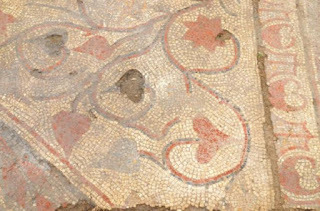

4th century mosaic floors excavated (Credit: © Jean-Louis Bellurget, INRAP)

Impressive Mosaics Amaze Archaeologists

The team of archaeologists has been particularly impressed by the large, prepossessing, colorful mosaics, which are expected to be removed during this month. The mosaics contain several geometric and floral motifs, leaves of ivy, laurel and acanthus; friezes with waves, others with egg-shaped patterns, separated by tridents; octagons with five-leafed flowers and squares separated by three-strand braids. An impressed Mr. Lotti couldn’t hide his excitement in his statements as Connexion reports, “It was not just a dwelling. It was also a place of representation, so it had to be fairly stunning,” he said. Mosaics were seen as a form of fine art by both the ancient Greeks and Romans, who assembled small pieces of colored glass, ceramic, stone, or other materials into an image. Mosaics became particularly popular art form during the time of the Roman Empire, although they were used both before and after this period.

A large-handled 'canthare' vase in the mosaic (Credit: © Jean-Louis Bellurget, INRAP)

Coin Reveals the Age of the Aristocratic Domus

Archaeologists didn’t have any particular difficulty in dating the palace’s age since the discovery of a coin portraying Emperor Constantine I (272-337 AD) helped them conclude that the domus came into existence after the year 330 AD. The luxurious residence also possessed two underfloor heating systems, a technique that was first used by the Minoans and was further developed later by the Romans. Just a step from the excavation, other mosaics were also found, most likely from an earlier stage of the house. Furthermore, at another even deeper level was spotted a third mosaic adorned with four black tesserae forming a cross.

There is a floral motif theme in many of the mosaics at the domus in Auch (Credit: © Jean-Louis Bellurget, INRAP)

The dig is ongoing, and according to INRAP, as we already mentioned the archaeologists don’t have much time in their hands as the land will have to be returned to its owner by September.

Top image: The site is being carefully excavated before the mosaics are removed. (Credit: © Jean-Louis Bellurget, INRAP)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on July 28, 2017 00:30

July 27, 2017

Ancient Roman Sarcophagus of Great Archaeological Value Discovered in Central London

Ancient Origins

A remarkably rare Roman sarcophagus has been discovered at an ancient burial site in the Borough area of London, England. The stone coffin, has been described by experts as “the find of a lifetime”, as only two other similar sarcophagi have been found in their original burial place.

1,600-Year- Old Coffin Discovered in Borough Market

According to the archaeologists who made the discovery, the 1,600-year-old coffin, which was found near Borough Market in Central London, is believed to contain the remains of a woman, possibly a mother as the bones of a baby were found nearby. Experts cannot be sure yet if the baby was buried with the coffin, but they appear to be certain that the coffin has been opened and looted, possibly by 18th century grave robbers in an area that was used by the Romans as a burial ground. Gillian King, senior planner for archaeology at Southwark council, stated as BBC reports, “A large crack on the lid was probably the work of thieves. I hope they have left the things that were of small value to them but great value to us as archaeologists".

Archaeologists prepare to lift the lid at the site in Swan Street, Southwark (Lauren Hurley/PA)

Furthermore, Gillian King speculates that the grave owner was probably someone from the highest socioeconomic classes, “(the grave owner) was probably very wealthy and would have had a lot of social status to be honored with not just a sarcophagus, but one that was built into the walls of a mausoleum," she says as BBC reported. A metal detector was used to scan the coffin and it registered metal items but what these might be is unknown until further excavation due to it being filled with dirt.

The coffin was found to be filled with dirt, possibly after looting (Lauren Hurley/PA)

Exorbitant Roman Sarcophagus Found in Oxfordshire

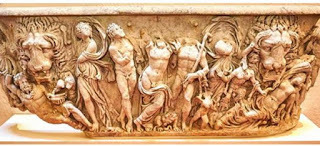

Of course, this is not the first time a Roman sarcophagus has been discovered in England. As we reported in a previous Ancient Origins article, in March 2017, possibly the most luxurious and expensive ancient Roman sarcophagus in British history (worth up to 345,000 Euros) was found. The precious marble coffin was discovered on the grounds of Blenheim Palace, a monumental country house situated in Woodstock, Oxfordshire. The precious Roman artifact of immense archaeological and historical significance, served as a humble flowerpot for the past 100 years in the rock garden of what is also Sir Winston Churchill's birthplace in Oxfordshire.

Before that, the valuable sarcophagus was obtained and used during the 19th century as a garden ornament (a type of fountain) by the fifth Duke of Marlborough, who was famous for his impressive collection of antiquities. Palace officials decided to better examine the almost two meters (6’6ft) long artifact at the suggestion of an antiques expert, who was impressed by the object’s ornate carvings. Ironically, his visit was unrelated to the Roman marble coffin, which he noticed coincidentally.

A Roman sarcophagus that was once used as a garden ornament is now restored and displayed in Blenheim Palace. Source: Blenheim Palace

After conservators removed the front marble section, which is the genuine part, and carried out a detailed examination they were shocked to identify the basin as a white marble sarcophagus portraying lively and noisy Dionysian festivities, dating back to 300 AD. The sarcophagus is now positioned on public display in an underground room in Blenheim Palace.

The Archaeological Importance of the Recent Discovery

Despite not being as luxurious and expensive as the Roman sarcophagus discovered in Oxfordshire, the newly found coffin is of great archaeological value. Ms. King made sure to highlight its archaeological value in a statement as Southwark News reports, “In my long archaeological career I have excavated many hundreds of burials, but this is the first Roman sarcophagus I have ever discovered, still surviving in its original place of deposition. I have seen them in museums, but I think part of me believed that they had probably all been found by now.” And continues, “It really is a very special discovery. Personally, I find it really fascinating to contemplate that this area – which we are now so familiar with – was once, during the Roman period, so completely different. It really does make me feel very honored that my role at Southwark Council contributes to protecting amazing archaeological treasures like this, and our work means that we can ensure that the historic environment is championed and preserved for the enjoyment of us and future generations.”

This discovery was made at one of a number of sites that are being investigated in the Southwark area. The area is now known to contain several religious monuments as part of a ‘complex ritual landscape’ including 3 other Roman cemeteries. However, only two other sarcophagi have been found where they were initially buried.

Cllr Peter John, the Leader of Southwark Council, added to Ms. King’s statements, “In Southwark we take our duty as custodians of the borough’s rich, varied and important archaeological heritage very seriously. This Roman sarcophagus is the find of a lifetime and a credit to the council’s commitment to ensuring that the borough’s history is properly conserved,” Southwark News reports. The sarcophagus will soon be transferred to the Museum of London’s archive in Hackney, where experts will examine and date the bones and soil inside.

Top image: Removing the lid of Roman sarcophagus found in Borough Market, London (Lauren Hurley/PA)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on July 27, 2017 01:30