MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 46

September 4, 2017

What did people in the Tudor period eat?

History Extra

What did people in the Tudor period eat?

Rank, station, and even religious customs affected what you ate throughout the Tudor period.

Meat was forbidden on a Friday, when people ate fish instead. However, Henry VIII tended to be flexible, and often included certain meats, declaring them to be ‘fish’.

Certainly the Tudors ate a wider variety of meat than we do today, including swan, peacock, beaver, ox, venison, and wild boar. They did not eat raw vegetables or fruit, believing them to be harmful. Water, especially in cities like London, was polluted, and wealthier individuals drank wine. Everybody drank diluted ale and small beer.

Bread was an important staple of the Tudor diet; the most expensive was manchet bread, which was eaten only by the wealthy.

Lauren Mackay is the author of Inside the Tudor Court: Henry VIII and his Six Wives through the Life and Writings of the Spanish Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys (Amberley Publishing).

Published on September 04, 2017 00:30

September 3, 2017

How the Longbow Revolutionised Warfare in the Middle Ages

Made from History

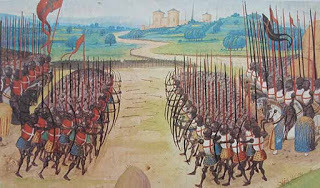

A medieval illustration of longbowmen in battle from Froissart’s Chronicle.

BY TOM CROPPER

The English Longbow was one of the defining weapons of the middle ages. It helped England challenge the might of the French and enabled ordinary peasants to defeat wealthy knights.

Origins

The longbow is generally considered to be an invention of the middle ages, but in truth it has been around since the Stone Age. It was the Welsh, however, who perfected the art, using it to great effect. The first documented occasion of a long bow being used in battle was in 633 in a battle between the Welsh and the Mercians.

It also impressed Edward I during his campaigns against the Welsh. It is said that he incorporated Welsh conscript archers in his later battles in Scotland. He even banned all sports on a Sunday except archery so his archers could hone their skills.

How the Longbow Was Made

The genius of the longbow was its simplicity. It was a length of wood – normally willow or Yew – about the height of a man. Each one was tailor made to its owner and could produce enough power to pierce even the toughest armour of the time.

Using a longbow was not easy. Each bow was heavy and required considerable strength to use. The skeletons of medieval archers appear noticeably deformed with enlarged left arms and often bone spurs on the wrists. Using one effectively was another matter altogether. The weapon had to be used quickly and accurately with the best archers managing a firing rate of one ever five seconds, which in turn gave them a crucial advantage over the crossbows, which not only took longer to fire, but also had a shorter range.

A 15th century miniature showing longbowmen from the Battle of Agincourt 25 October 1415.

Success in War

It was in the Hundred Years War that the longbow came into its own. At the battle of Crecy, English archers were instrumental in defeating a much larger and better equipped French force. At the time warfare had been dominated by the power of the knight, clad in expensive armour and riding an even more expensive war horse. Battles were fought on the principles of chivalry with captured knights being treated with all due respect and returned on receipt of a ransom.

At Crecy Edward III changed the rules. In one battle the flower of French chivalry was cut down in its prime. Two thousand French knights and soldiers were killed by the English arrows, while only around 50 archers were killed. It sent shock waves throughout France. Not only was there the disaster of the defeat to be accounted for, but also the shocking fact that highly trained knights had been killed by low born archers.

English archers would continue to be influential in later battles in The 100 Years War, particularly in Agincourt where English bowmen again defeated a much better equipped army of French knights.

Legacy

Over time the longbow was replaced by gunpowder, but it continues to hold a special place in English psyche. It was even deployed during World War II, when an English soldier used one to bring down a German infantryman. That was the last time it’s been known to have been used in war, but it continues to be used in sport and by archers trained in the medieval skill.

The longbow continues to be used for sport and exhibitions to this day.

A medieval illustration of longbowmen in battle from Froissart’s Chronicle.

BY TOM CROPPER

The English Longbow was one of the defining weapons of the middle ages. It helped England challenge the might of the French and enabled ordinary peasants to defeat wealthy knights.

Origins

The longbow is generally considered to be an invention of the middle ages, but in truth it has been around since the Stone Age. It was the Welsh, however, who perfected the art, using it to great effect. The first documented occasion of a long bow being used in battle was in 633 in a battle between the Welsh and the Mercians.

It also impressed Edward I during his campaigns against the Welsh. It is said that he incorporated Welsh conscript archers in his later battles in Scotland. He even banned all sports on a Sunday except archery so his archers could hone their skills.

How the Longbow Was Made

The genius of the longbow was its simplicity. It was a length of wood – normally willow or Yew – about the height of a man. Each one was tailor made to its owner and could produce enough power to pierce even the toughest armour of the time.

Using a longbow was not easy. Each bow was heavy and required considerable strength to use. The skeletons of medieval archers appear noticeably deformed with enlarged left arms and often bone spurs on the wrists. Using one effectively was another matter altogether. The weapon had to be used quickly and accurately with the best archers managing a firing rate of one ever five seconds, which in turn gave them a crucial advantage over the crossbows, which not only took longer to fire, but also had a shorter range.

A 15th century miniature showing longbowmen from the Battle of Agincourt 25 October 1415.

Success in War

It was in the Hundred Years War that the longbow came into its own. At the battle of Crecy, English archers were instrumental in defeating a much larger and better equipped French force. At the time warfare had been dominated by the power of the knight, clad in expensive armour and riding an even more expensive war horse. Battles were fought on the principles of chivalry with captured knights being treated with all due respect and returned on receipt of a ransom.

At Crecy Edward III changed the rules. In one battle the flower of French chivalry was cut down in its prime. Two thousand French knights and soldiers were killed by the English arrows, while only around 50 archers were killed. It sent shock waves throughout France. Not only was there the disaster of the defeat to be accounted for, but also the shocking fact that highly trained knights had been killed by low born archers.

English archers would continue to be influential in later battles in The 100 Years War, particularly in Agincourt where English bowmen again defeated a much better equipped army of French knights.

Legacy

Over time the longbow was replaced by gunpowder, but it continues to hold a special place in English psyche. It was even deployed during World War II, when an English soldier used one to bring down a German infantryman. That was the last time it’s been known to have been used in war, but it continues to be used in sport and by archers trained in the medieval skill.

The longbow continues to be used for sport and exhibitions to this day.

Published on September 03, 2017 01:00

September 2, 2017

The Ides of March: The Assassination of Julius Caesar Explained

Made from History

BY COLIN RICKETTS

The date that Julius Caesar, the most famous Roman of them all, was killed at or on his way to the Senate is one of the most famous in world history. The events of the Ides of March – March 15th in the modern calendar – in 44 BC had enormous consequences for Rome, triggering a series of civil wars that saw Caesar’s great-nephew Octavian secure his place as Augustus, the first Roman Emperor.

But what actually happened on this famous date? The answer must be that we will never know in any great detail or with any great certainty.

There is no eye-witness account of Caesar’s death. Nicolaus of Damascus wrote the earliest surviving account, probably around 14 AD. While some people believe he may have spoken to witnesses, nobody knows for sure, and his book was written for Augustus so may be biased. Suetonius’ telling of the tale is also believed to be fairly accurate, possibly using eye-witness testimony, but was written around 121 AD.

The Conspiracy Against Caesar

Even the briefest study of Roman politics will open a can of worms rich in plotting and conspiracies. Rome’s institutions were relatively stable for their time, but military strength and popular support (as Caesar himself showed), could rewrite the rules very quickly. Power was always up for grabs.

Caesar’s extraordinary personal power was bound to excite opposition. Rome was then a republic and doing away with the arbitrary and often-abused power of kings was one of its founding principles.

Marcus Junius Brutus the Younger – a key conspirator.

In 44 BC Caesar had been appointed dictator (a post previously awarded only temporarily and in times of great crisis) with no time limit on the term. The people of Rome certainly saw him as a king, and he may have already have been regarded as a god.

More than 60 high-ranking Romans, including Marcus Junius Brutus, who may have been Caesar’s illegitimate son, decided to do away with Caesar. They called themselves the Liberators, and their ambition was to restore the power of the Senate.

The Ides of March

This is what Nicolaus of Damascus records:

The conspirators considered a number of plans for killing Caesar, but settled on an attack in the Senate, where their togas would provide cover for their blades.

Rumours of a plot were going around and some of Caesar’s friends tried to stop him going to the Senate. His doctors were concerned by dizzy spells he was suffering and his wife, Calpurnia, had had worrying dreams. Brutus stepped in to reassure Caesar that he would be fine.

He is said to have made some sort of religious sacrifice, revealing bad omens, despite several attempts to find something more encouraging. Again many friends warned him to go home, and again Brutus reassured him.

In the Senate, one of the plotters, Tilius Cimber, approached Caesar under the pretext of pleading for his exiled brother. He grabbed Caesar’s toga, preventing him from standing and apparently signalling the attack.

Nicolaus recounts a messy scene with men injuring each other as they scramble to kill Caesar. Once Caesar was down, more conspirators rushed in, perhaps keen to make their mark on history, and he was reportedly stabbed 35 times.

Caesar’s famous last words, ‘Et tu, Brute?’ are almost certainly an invention, given longevity by William Shakespeare’s dramatised version of events.

The Aftermath: Republican Ambitions Backfire, War Ensues

Expecting a hero’s reception, the assassins ran out into the streets announcing to the people of Rome that they were free again.

But Caesar had been enormously popular, particularly with ordinary people who had seen Rome’s military triumphant while they had been well treated and entertained by Caesar’s lavish public entertainments. Caesar’s supporters were ready to use this people power to support their own ambitions.

The Senate voted an amnesty for the assassins, but Caesar’s chosen heir, Octavian, was quick to return to Rome from Greece to explore his options, recruiting Caesar’s soldiers to his cause as he went. Caesar’s supporter, Mark Antony, also opposed the Liberators, but may have had ambitions of his own. He and Octavian entered into a shaky alliance as the first fighting of a civil war began in northern Italy.

On November 27th, 43 BC, the Senate named Antony and Octavian as two heads of a Triumvirate, together with Caesar’s friend and ally Lepidus, tasked with taking on Brutus and Cassius, two of the Liberators. They set about murdering many of their opponents in Rome for good measure.

The Liberators were defeated in two battles in Greece, allowing the Triumvirate to rule for an uneasy 10 years.

Mark Antony then made his move, marrying Cleopatra, Caesar’s lover and queen of Egypt, and planning to use Egypt’s wealth to fund his own ambitions. Both of them committed suicide in 30 BC after Octavian’s decisive victory at the naval Battle of Actium.

By 27 BC Octavian could rename himself Caesar Augustus. He would go on to be remembered as the first Emperor of Rome.

BY COLIN RICKETTS

The date that Julius Caesar, the most famous Roman of them all, was killed at or on his way to the Senate is one of the most famous in world history. The events of the Ides of March – March 15th in the modern calendar – in 44 BC had enormous consequences for Rome, triggering a series of civil wars that saw Caesar’s great-nephew Octavian secure his place as Augustus, the first Roman Emperor.

But what actually happened on this famous date? The answer must be that we will never know in any great detail or with any great certainty.

There is no eye-witness account of Caesar’s death. Nicolaus of Damascus wrote the earliest surviving account, probably around 14 AD. While some people believe he may have spoken to witnesses, nobody knows for sure, and his book was written for Augustus so may be biased. Suetonius’ telling of the tale is also believed to be fairly accurate, possibly using eye-witness testimony, but was written around 121 AD.

The Conspiracy Against Caesar

Even the briefest study of Roman politics will open a can of worms rich in plotting and conspiracies. Rome’s institutions were relatively stable for their time, but military strength and popular support (as Caesar himself showed), could rewrite the rules very quickly. Power was always up for grabs.

Caesar’s extraordinary personal power was bound to excite opposition. Rome was then a republic and doing away with the arbitrary and often-abused power of kings was one of its founding principles.

Marcus Junius Brutus the Younger – a key conspirator.

In 44 BC Caesar had been appointed dictator (a post previously awarded only temporarily and in times of great crisis) with no time limit on the term. The people of Rome certainly saw him as a king, and he may have already have been regarded as a god.

More than 60 high-ranking Romans, including Marcus Junius Brutus, who may have been Caesar’s illegitimate son, decided to do away with Caesar. They called themselves the Liberators, and their ambition was to restore the power of the Senate.

The Ides of March

This is what Nicolaus of Damascus records:

The conspirators considered a number of plans for killing Caesar, but settled on an attack in the Senate, where their togas would provide cover for their blades.

Rumours of a plot were going around and some of Caesar’s friends tried to stop him going to the Senate. His doctors were concerned by dizzy spells he was suffering and his wife, Calpurnia, had had worrying dreams. Brutus stepped in to reassure Caesar that he would be fine.

He is said to have made some sort of religious sacrifice, revealing bad omens, despite several attempts to find something more encouraging. Again many friends warned him to go home, and again Brutus reassured him.

In the Senate, one of the plotters, Tilius Cimber, approached Caesar under the pretext of pleading for his exiled brother. He grabbed Caesar’s toga, preventing him from standing and apparently signalling the attack.

Nicolaus recounts a messy scene with men injuring each other as they scramble to kill Caesar. Once Caesar was down, more conspirators rushed in, perhaps keen to make their mark on history, and he was reportedly stabbed 35 times.

Caesar’s famous last words, ‘Et tu, Brute?’ are almost certainly an invention, given longevity by William Shakespeare’s dramatised version of events.

The Aftermath: Republican Ambitions Backfire, War Ensues

Expecting a hero’s reception, the assassins ran out into the streets announcing to the people of Rome that they were free again.

But Caesar had been enormously popular, particularly with ordinary people who had seen Rome’s military triumphant while they had been well treated and entertained by Caesar’s lavish public entertainments. Caesar’s supporters were ready to use this people power to support their own ambitions.

The Senate voted an amnesty for the assassins, but Caesar’s chosen heir, Octavian, was quick to return to Rome from Greece to explore his options, recruiting Caesar’s soldiers to his cause as he went. Caesar’s supporter, Mark Antony, also opposed the Liberators, but may have had ambitions of his own. He and Octavian entered into a shaky alliance as the first fighting of a civil war began in northern Italy.

On November 27th, 43 BC, the Senate named Antony and Octavian as two heads of a Triumvirate, together with Caesar’s friend and ally Lepidus, tasked with taking on Brutus and Cassius, two of the Liberators. They set about murdering many of their opponents in Rome for good measure.

The Liberators were defeated in two battles in Greece, allowing the Triumvirate to rule for an uneasy 10 years.

Mark Antony then made his move, marrying Cleopatra, Caesar’s lover and queen of Egypt, and planning to use Egypt’s wealth to fund his own ambitions. Both of them committed suicide in 30 BC after Octavian’s decisive victory at the naval Battle of Actium.

By 27 BC Octavian could rename himself Caesar Augustus. He would go on to be remembered as the first Emperor of Rome.

Published on September 02, 2017 01:00

September 1, 2017

Analysis of Roman Coins Proves Roman Empire Got Rich on Iberian Silver

Ancient Origins

An analysis of Roman coins has revealed information about the defeat of the Carthaginian General Hannibal and the rise of the Roman Empire. The scientists who examined them suggest that the defeat of the Carthaginian general led to a flood of wealth across the Roman Empire coming from mines on the Iberian Peninsula in Spain.

Roman Coins Track Down the Fall of Hannibal of Carthage and the Rise of Roman Empire A recent examination of Roman coins has revealed how the defeat of Hannibal and the Carthaginian Empire led to coinage spreading across the Roman Empire from silver mines in Spain, as Phys Org reports.

Hannibal was a Carthaginian general who fought against Rome during the second Punic war. His name became synonymous with inciting fear, and to this day he is considered one of the greatest military leaders of all time. As reported in a previous Ancient Origins article, Hannibal was born in Carthage (known as Tunisia today) in 247 BC to Carthaginian leader Hamilcar Barca. One of his most notable achievements was his crossing of the Alps into Italy, where he sought to join up with anti-Roman allies in the region.

According to many historical accounts he led the Carthaginian army and a team of elephants across southern Europe and the Alps Mountains to battle against Rome in the Second Punic War. There has been much scholarly debate as to Hannibal’s exact path through the Alps, but it is the consensus that the journey was treacherous.

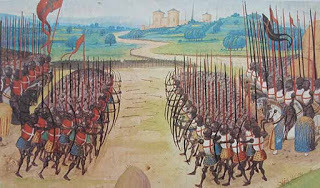

Detail, Hannibal's Famous Crossing of the Alps with War Elephants (Public Domain )

During the Second Punic War, Hannibal defeated the Roman army in several battles, but never managed to capture the city completely. Eventually, Rome counterattacked and he was forced to return to Carthage where he was defeated. He worked for a time as a statesman before he was forced into exile by Rome. To avoid capture by the Romans, he eventually took his own life.

Geochemical Analysis Techniques Reveal New Information

Many centuries after the end of the Second Punic War and Hannibal’s downfall, the use of geochemical analysis techniques has helped modern scientists to prove the vast significance of the Spanish silver – owned by Hannibal before losing to the Romans – to the Roman Empire’s rise. As Phys Org reports, a team of scientists based in Germany and Denmark examined seventy Roman coins dating from around 310 to 101 BC. The coins were drilled at the rim to obtain fresh, untouched heart metal for the measurements. Using Mass Spectrometry, the scientists were able to show that lead in the coins made after 209 BC has characteristic isotopic signatures which identified most of the later coins as undoubtedly originating from Spanish sources. After 209 BC, the lead isotope signatures mainly correlate to those of deposits in southeast and southwest Spain or to mixtures of metal unearthed from these districts.

"Before the war, we find that the Roman coins are made of silver from the same sources as the coinage issued by Greek cities in Italy and Sicily. In other words the lead isotope signatures of the coins correspond to those of silver ores and metallurgical products from the Aegean region," researcher Katrin Westner told Phys Org. And added, "But the defeat of Carthage led to huge reparation payments to Rome, as well as Rome gaining large amounts of booty and ownership of the rich Spanish silver mines. From 209 BC, we see that the majority of Roman coins show geochemical signatures typical for Iberian silver."

A Carthaginian silver shekel depicting a man wearing a laurel wreath on the obverse, and a man riding a war elephant on the reverse, c. 239-209 BC (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Iberian Silver Changes Rome's Economic Status

The scientists have no doubt that the incredible flood of wealth across the Roman territories coming from mines on Iberian Peninsula played a significant role to the Empire’s economic rise, “This massive influx of Iberian silver significantly changed Rome's economy, allowing it to become the superpower of its day. We know this from the histories of Livy and Polybius and others, but our work gives contemporary scientific proof of the rise of Rome. What our work shows is that the defeat of Hannibal and the rise of Rome is written in the coins of the Roman Empire,” they stated as Phys Org reports. Furthermore, Dr. Kevin Butcher of the University of Warwick, said the project has verified what had previously only been speculation, "This research demonstrates how scientific analysis of ancient coins can make a significant contribution to historical research. It allows what was previously speculation about the importance of Spanish silver for the coinage of Rome to be placed on a firm foundation."

The scientists presented their work for the first time in Paris yesterday, at the Goldschmidt geochemistry conference.

Top image: The Battle of Cannae was a major battle of the Second Punic War that took place on 2 August 216 BC in Apulia, in southeast Italy. The army of Carthage, under Hannibal, surrounded and decisively defeated a larger army of the Roman Republic (public domain)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on September 01, 2017 01:00

August 31, 2017

Even in Viking Times Norway was Famous for its ‘White Gold’… a ‘Gold’ You can Eat!

Ancient Origins

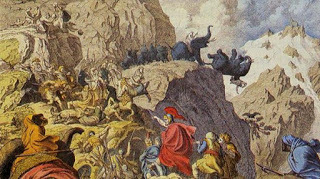

New research using DNA from the fish bone remains of Viking-era meals reveals that north Norwegians have been transporting – and possibly trading – Arctic cod into mainland Europe for a millennium.

Norway is famed for its cod. Catches from the Arctic stock that spawn each year off its northern coast are exported across Europe for staple dishes from British fish and chips to Spanish bacalao stew.

Now, a new study published today in the journal PNAS suggests that some form of this pan-European trade in Norwegian cod may have been taking place for 1,000 years.

Norwegian cod – Norway’s ‘White Gold’. (Seafood from Norway)

Latest research from the universities of Cambridge and Oslo, and the Centre for Baltic and Scandinavian Archaeology in Schleswig, used ancient DNA extracted from the remnants of Viking-age fish suppers.

The study analysed five cod bones dating from between 800 and 1066 AD found in the mud of the former wharves of Haithabu, an early medieval trading port on the Baltic. Haithabu is now a heritage site in modern Germany, but at the time was ruled by the King of the Danes.

The DNA from these cod bones contained genetic signatures seen in the Arctic stock that swim off the coast of Lofoten: the northern archipelago still a centre for Norway’s fishing industry.

Fish from Rügen’ (1882) by Hans Gude. (Public Domain)

Researchers say the findings show that supplies of ‘stockfish’ – an ancient dried cod dish popular to this day – were transported over a thousand miles from northern Norway to the Baltic Sea during the Viking era.

Prior to the latest study, there was no archaeological or historical proof of a European stockfish trade before the 12th century.

While future work will look at further fish remains, the small size of the current study prevents researchers from determining whether the cod was transported for trade or simply used as sustenance for the voyage from Norway.

However, they say that the Haithabu bones provide the earliest evidence of fish caught in northern Norway being consumed on mainland Europe – suggesting a European fish trade involving significant distances has been in operation for a millennium.

One of the ancient Viking cod bones from Haithabu used in the study. (James Barrett)

“Traded fish was one of the first commodities to begin to knit the European continent together economically,” says Dr James Barrett, senior author of the study from the University of Cambridge’s McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. “Haithabu was an important trading centre during the early medieval period. A place where north met south, pagan met Christian, and those who used coin met those who used silver by weight.” “By extracting and sequencing DNA from the leftover fish bones of ancient cargoes at Haithabu, we have been able to trace the source of their food right the way back to the cod populations that inhabit the Barents Sea, but come to spawn off Norway’s Lofoten coast every winter.

Reconstructed Viking Age longhouses at Haithabu. (CC BY SA 3.0)

“This Arctic stock of cod is still highly prized – caught and exported across Europe today. Our findings suggest that distant requirements for this Arctic protein had already begun to influence the economy and ecology of Europe in the Viking age.”

Stockfish is white fish preserved by the unique climate of north Norway, where winter temperature hovers around freezing. Cod is traditionally hung out on wooden frames to allow the chill air to dry the fish. Some medieval accounts suggest stockfish was still edible as much as ten years after preservation.

The research team argue that the new findings offer some corroboration to the unique 9th century account of the voyages of Ohthere of Hålogaland: a Viking chieftain whose visit to the court of King Alfred in England resulted in some of his exploits being recorded.

“In the accounts inserted by Alfred’s scribes into the translation of an earlier 5th century text, Ohthere describes sailing from Hålogaland to Haithabu,” says Barrett. Hålogaland was the northernmost province of Norway. “While no cargo of dried fish is mentioned, this may be because it was simply too mundane a detail,” says Barrett. “The fish-bone DNA evidence is consistent with the Ohthere text, showing that such voyages between northern Norway and mainland Europe were occurring.”

‘Vikings Heading for Land’ (1873) by Frank Dicksee. (Public Domain)

“The Viking world was complex and interconnected. This is a world where a chieftain from north Norway may have shared stockfish with Alfred the Great while a late-antique Latin text was being translated in the background. A world where the town dwellers of a cosmopolitan port in a Baltic fjord may have been provisioned from an Arctic sea hundreds of miles away.”

The sequencing of the ancient cod genomes was done at the University of Oslo, where researchers are studying the genetic makeup of Atlantic cod in an effort to unpick the anthropogenic impacts on these long-exploited fish populations.

“Fishing, particularly of cod, has been of central importance for the settlement of Norway for thousands of years. By combining fishing in winter with farming in summer, whole areas of northern Norway could be settled in a more reliable manner,” says the University of Oslo’s Bastiaan Star, first author of the new study.

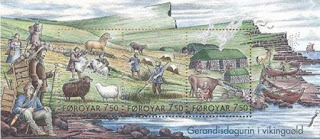

Stamps Showing Everyday Life in the Viking Age Stamps showing ‘Everyday Life in the Viking Age.’ (Public Domain)

Star points to the design of Norway’s new banknotes that prominently feature an image of cod, along with a Viking ship, as an example of the cultural importance still placed on the fish species in this part of Europe.

“We want to know what impact the intensive exploitation history covering millennia has inflicted on Atlantic cod, and we use ancient DNA methods to investigate this,” he says.

The study was funded by the Research Council of Norway and the Leverhulme Trust.

Top Image: Vikings. Summer in the Greenland coast circa year 1000. Source: Public Domain

The article, originally titled ‘DNA from Viking cod bones suggests 1,000 years of European fish trade’ was originally published on University of Cambridge and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Published on August 31, 2017 02:00

August 30, 2017

Laser Tech Reveals 1,000-Year-Old Viking Ring Fortress in Denmark

Ancient Origins

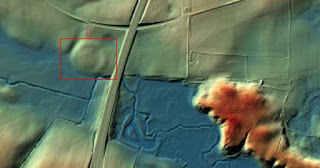

With the help of laser technology, archaeologists have managed to discover a perfectly circular ring fortress in Borgring, Denmark. It dates back to 975-980 AD, and experts suggest that it was constructed during the reign of King Harald Bluetooth.

Borgring Fortress First to be Discovered in Denmark

Since 1953 IBTimes UK reports that the impressive Borgring fortress is the first to be discovered in Denmark since 1953. What has amazed experts the most about this massive fortress is how it appears to be in a very precise circular shape, measuring almost 150 meters in diameter. The building is one of the Trelleborg-type fortresses that have a characteristic circular shape and internal design. The earthworks, houses and other structures are carefully positioned within the fortress and four gates are positioned around the perimeter at cardinal points.

“The Borgring fortress had been tentatively identified in the 1970s, but the technology was lacking then to verify whether it really was a Trelleborg-type fortress,” study author Søren Michael Sindbæk of Aarhus University, told IBTimes UK. And continued, “That is the most beautiful aspect of our results – the suspicion that this could have been a fortress was raised by a very beautiful map made in 1970 that was the best survey method you had in those days. But it was impossible to prove it in those days."

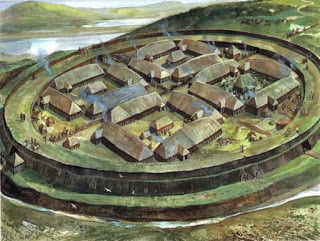

The Trelleborg ring fortress (CC by SA 3.0)

Airborne Laser Scanning Helps Archaeologists to Examine the Fortress

With the help of advanced modern technology such as LiDAR – airborne laser scanning – Sindbæk and his colleagues managed to estimate significant differences at ground-level indicating the presence of the ring fortress as IBTimes UK reports. Before its demolition, the Borgring fortress was created from wood with earth-and-turf ramparts. The fortress contained two streets with that intersected each other to form a cross shape. The streets were most likely paved with timber, with four vast wooden structures within the fortress.

The importance of the discovery consists of the fact that there have only been five confirmed Trelleborg fortresses discovered in Denmark until now. They were all constructed in a short period of time between 975 and 980 AD, during the reign of Harald Bluetooth, a 10th century king who Christianized both Denmark and Norway.

Architectural Achievements of the Vikings

In 2014, archaeologists identified another impressive fortress through laser scan, which had been initially discovered in 1875 – a ring-shaped Viking fortress on the Danish island of Zealand – which historians suggested could have been used to train warriors before launching an invasion of England. As previously reported in an Ancient Origins article, even though the Vikings carry a reputation as brutish invaders, the latest finding shows that they were also accomplished builders. Coincidentally, the research team that made that discovery in 2014, suggested that the fortress dated back to the reign of Harald Bluetooth as well.

Reconstruction of a Viking ring fortress. Unknown artist

Massive, Circular Constructions

The obvious similarity between all these buildings that were constructed during Harald Bluetooth’s reign is that they are all massive and circular constructions typically between 140 to 250 meters in diameter. "They posed a real enigma about the Viking Age when they were first discovered. The Vikings were perceived to be a society of local petty kings competing over power," Sindbæk tells IBTimes UK. And adds, "They are related to a period of exceptional expression of kingship. The question is whether that means we need a complete reassessment of Viking society, or whether we should just be revisiting evidence from this particular period," Sindbæk says, wondering how such vast and costly constructions appeared in Denmark all of a sudden around the year 975.

Enemies Led to the Construction of the Buildings

The fact that these large fortresses were constructed within just five years makes Sindbæk speculate that the Vikings were facing dangerous external enemies coming from the German and Slavic lands. “If we look at the 970s and 980s, it's exactly a time where every authority bordering on this empire is in a high state of emergency. There is a military power which is unprecedented and isn't repeated again for several generations," Sindbæk told IBTimes UK.

Interestingly, after the German emperor died in the 980s, the construction of massive and expensive buildings in Denmark stopped suddenly, a fact that appears to justify Sindbæk’s speculations, who closes his mini-interview by pointing out the historical value and importance of these fortresses by stating to IBTimes UK, "We have barely any other similar fortresses in Norway or Sweden, and in Denmark there are no other very large fortresses of any kind. So they are very special. Because of the dates it seems that they coincide with a very unique military situation."

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on August 30, 2017 00:00

August 29, 2017

3 Kinds of Ancient Roman Shields

Made from History

BY GRAHAM LAND

Umbo from Roman shield. Credit: MatthiasKabel (Wikimedia Commons)

The use of shields in battle originates in pre-history and is present in the earliest known human civilisations. A logical evolution in armed combat, shields were used to block attacks from hand-held weapons like swords as well as projectile weapons such as arrows. Early shields were typically constructed of wood and animal hide and later reinforced with metal.

Shields of Ancient Rome

Roman soldiers or legionaires were well protected by leather and iron armour, helmets and shields, called scuta. The shapes and styles of Roman shields differed according to use and timeframe. Many shields were based on Greek aspis or hoplon, which were round and deeply concave like a dish.

Aspides were wooden and sometimes plated with bronze. Some Roman shields were strengthened by plating their edges with a copper alloy, though this was eventually abandoned in favour of using stitched rawhide, which bound the shields more effectively.

Roman shields also featured a boss or umbo, a thick, round, wooden or metal protrusion that deflected blows and served as a place to mount the grip.

1. Legionaire Scutum

The most famous of the Roman shields, great scuta were large and either rectangular or oval. Early oval scuta evolved into the rectangular, semi-cylindrical versions, which were used by the foot soldiers of the early Empire to great effect. Their concave nature offered substantial protection, but made the use of weapons somewhat difficult as it restricted arm movement.

The only known surviving example of a semicylindrical scutum. Credit: Yale University Art Gallery

The use of rectangular scuta ended by the 3rd century AD, but scuta in general survived into the Byzantine Empire.

Testudo Formation

A battle formation that made excellent use of the great scuta was the testudo or tortoise formation, in which soldiers would gather close and align their shields both in front and on top. This protected the group from frontal attacks and projectiles launched from above.

Re-enactment of Roman testudo formation using rectangular scuta.Credit: Neil Carey (Wikimedia Commons)

2. Parma

For reasons of movement and balance, soldiers on horseback used smaller round shields, called parma. A typical Parma measured a maximum of 36” across and had a strong iron frame, though these were eventually abandoned for lighter oval shields of wood and leather.

During the early Republican period, foot soldiers also used a kind of parma, but this was replaced by the longer scuta, which offered more protection.

3. Clipeus

The clipeus was the Roman version of the Greek aspis. Although the clipeus was used alongside the rectangular legionaire or great scutum, after the 3rd century the oval or round clipeus became the standard shield of the Roman soldier.

Based on examples discovered at archaeological sites, the clipeus was constructed of vertical glued planks, covered with painted leather and bound on the edges with stitched rawhide.

A sculpture of a clipeus from the 1st century AD, featuring Jupiter-Amon, an amalgamation of Roman and Egyptian gods. Credit: National Archeological Museum of Tarragona

Gladiator Shields

The entertainment aspect of gladiatorial fighting leant itself to variety. Contestants were therefore outfitted with different types of shields, whether of Greek or Roman origin or from a foreign, conquered land. It wasn’t unusual to see a hexagonal Germanic shield in the gladiators’ ring, while an elaborately decorated scutum, parma or clipeus served to heighten the spectacle.

BY GRAHAM LAND

Umbo from Roman shield. Credit: MatthiasKabel (Wikimedia Commons)

The use of shields in battle originates in pre-history and is present in the earliest known human civilisations. A logical evolution in armed combat, shields were used to block attacks from hand-held weapons like swords as well as projectile weapons such as arrows. Early shields were typically constructed of wood and animal hide and later reinforced with metal.

Shields of Ancient Rome

Roman soldiers or legionaires were well protected by leather and iron armour, helmets and shields, called scuta. The shapes and styles of Roman shields differed according to use and timeframe. Many shields were based on Greek aspis or hoplon, which were round and deeply concave like a dish.

Aspides were wooden and sometimes plated with bronze. Some Roman shields were strengthened by plating their edges with a copper alloy, though this was eventually abandoned in favour of using stitched rawhide, which bound the shields more effectively.

Roman shields also featured a boss or umbo, a thick, round, wooden or metal protrusion that deflected blows and served as a place to mount the grip.

1. Legionaire Scutum

The most famous of the Roman shields, great scuta were large and either rectangular or oval. Early oval scuta evolved into the rectangular, semi-cylindrical versions, which were used by the foot soldiers of the early Empire to great effect. Their concave nature offered substantial protection, but made the use of weapons somewhat difficult as it restricted arm movement.

The only known surviving example of a semicylindrical scutum. Credit: Yale University Art Gallery

The use of rectangular scuta ended by the 3rd century AD, but scuta in general survived into the Byzantine Empire.

Testudo Formation

A battle formation that made excellent use of the great scuta was the testudo or tortoise formation, in which soldiers would gather close and align their shields both in front and on top. This protected the group from frontal attacks and projectiles launched from above.

Re-enactment of Roman testudo formation using rectangular scuta.Credit: Neil Carey (Wikimedia Commons)

2. Parma

For reasons of movement and balance, soldiers on horseback used smaller round shields, called parma. A typical Parma measured a maximum of 36” across and had a strong iron frame, though these were eventually abandoned for lighter oval shields of wood and leather.

During the early Republican period, foot soldiers also used a kind of parma, but this was replaced by the longer scuta, which offered more protection.

3. Clipeus

The clipeus was the Roman version of the Greek aspis. Although the clipeus was used alongside the rectangular legionaire or great scutum, after the 3rd century the oval or round clipeus became the standard shield of the Roman soldier.

Based on examples discovered at archaeological sites, the clipeus was constructed of vertical glued planks, covered with painted leather and bound on the edges with stitched rawhide.

A sculpture of a clipeus from the 1st century AD, featuring Jupiter-Amon, an amalgamation of Roman and Egyptian gods. Credit: National Archeological Museum of Tarragona

Gladiator Shields

The entertainment aspect of gladiatorial fighting leant itself to variety. Contestants were therefore outfitted with different types of shields, whether of Greek or Roman origin or from a foreign, conquered land. It wasn’t unusual to see a hexagonal Germanic shield in the gladiators’ ring, while an elaborately decorated scutum, parma or clipeus served to heighten the spectacle.

Published on August 29, 2017 01:00

August 28, 2017

The Year of the 6 Emperors

Made from History

Maximinus Thrax (image public domain)

During the late 2nd century and early 3rd century AD, Rome was rife with political instability, including the assassinations of several Emperors. This was a marked contrast to the era of Pax Romana, the period of prosperity and political stability that had defined the previous circa 200 years.

By the 3rd century, the Roman Empire had already experienced chaotic periods of leadership. The Year of the 4 Emperors in 69 AD, following the death of Nero by suicide, was but a taste of what was to come, and the instability that came after the assassination of the brutal and feckless Commodus meant the 192 AD saw a total of 5 Emperors rule Rome.

Maximinus Thrax Kicks off the Crisis

In 238 AD the office of Emperor would be its most unstable in history. Known as the Year of the 6 Emperors, it began during the short reign of Maximinus Thrax, who had ruled since 235. Thrax’s reign is considered by many scholars to be the start of the Crisis of the 3rd Century (235–84 AD), during which the Empire was beset by invasions, plague, civil wars and economic difficulties.

From low-born Thracian peasant stock, Maximinus was not a favourite of the Patrician Senate, which plotted against him from the start. The hatred was mutual, and the Emperor harshly punished any conspirators, largely supporters of his predecessor, Severus Alexander, who was killed by his own mutinous soldiers.

Gordian and Gordian II’s Brief and Imprudent Reign

An uprising against corrupt tax officials in the province of Africa spurred local landowners to proclaim the elderly provincial governor and his son as co-emperors. The Senate supported the claim, causing Maximinus Thrax to march on Rome. Meanwhile, the forces of the governor of Numidia entered Carthage in support of Maximinus, easily defeating the Gordians. The younger was killed in battle and the older committed suicide by hanging.

Pupienus, Balbinus and Gordian III Try to Tidy Up year of the six emperors

Coin made during Balbinus’ 99-day reign. Reverse shows Balbinus and Pupienus’ hands shaking.

Fearing the wrath of Maximinus upon his return to Rome, the Senate could nonetheless not go back on its rebellion. It elected two of its own members to the throne: Pupienus and Balbinus. The plebeian inhabitants of Rome, who preferred one of their own to rule rather than a pair of upper class patricians, showed their displeasure by rioting and casting sticks and stones at the new emperors.

In order to appease the displeased masses, Pupienus and Balbinus declared the 13-year-old grandson of the elder Gordian, Marcus Antonius Gordianus Pius, as Caesar.

Maximus’ march on Rome did not go as planned. His soldiers suffered from famine and disease during the siege and then eventually turned on him, killing him along with his chief ministers and son Maximus, who had been made deputy emperor. Soldiers carried the father and son’s severed heads into Rome, signifying their support for Pupienus and Balbinus as co-emperors, for which they were pardoned.

When Pupienius and Balbinus returned to Rome, they found the city again in chaos. They managed to calm it, albeit temporarily. Not long after, while arguing over who to attack in an enormous planned military campaign, the Emperors were seized by Praetorian Guard, stripped, dragged through the streets, tortured and killed.

On that day Marcus Antonius Gordianus Pius, or Gordian III, was proclaimed sole Emperor. He ruled from 239 – 244, largely as a figurehead controlled by his advisors, particularly the head of the Praetorian Guard, Timesitheus, who was also his father in law. Gordian III died of unknown causes while campaigning in the Middle East.

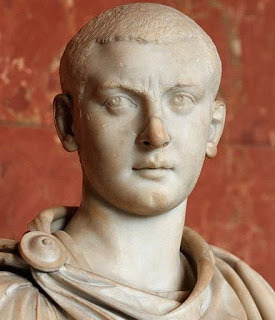

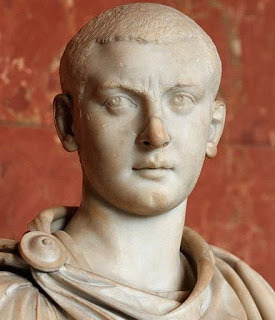

The popular boy-emperor Gordian III, credit: Ancienne collection Borghèse ; acquisition, 1807 / Borghese Collection; purchase, 1807

By Graham Land

Maximinus Thrax (image public domain)

During the late 2nd century and early 3rd century AD, Rome was rife with political instability, including the assassinations of several Emperors. This was a marked contrast to the era of Pax Romana, the period of prosperity and political stability that had defined the previous circa 200 years.

By the 3rd century, the Roman Empire had already experienced chaotic periods of leadership. The Year of the 4 Emperors in 69 AD, following the death of Nero by suicide, was but a taste of what was to come, and the instability that came after the assassination of the brutal and feckless Commodus meant the 192 AD saw a total of 5 Emperors rule Rome.

Maximinus Thrax Kicks off the Crisis

In 238 AD the office of Emperor would be its most unstable in history. Known as the Year of the 6 Emperors, it began during the short reign of Maximinus Thrax, who had ruled since 235. Thrax’s reign is considered by many scholars to be the start of the Crisis of the 3rd Century (235–84 AD), during which the Empire was beset by invasions, plague, civil wars and economic difficulties.

From low-born Thracian peasant stock, Maximinus was not a favourite of the Patrician Senate, which plotted against him from the start. The hatred was mutual, and the Emperor harshly punished any conspirators, largely supporters of his predecessor, Severus Alexander, who was killed by his own mutinous soldiers.

Gordian and Gordian II’s Brief and Imprudent Reign

An uprising against corrupt tax officials in the province of Africa spurred local landowners to proclaim the elderly provincial governor and his son as co-emperors. The Senate supported the claim, causing Maximinus Thrax to march on Rome. Meanwhile, the forces of the governor of Numidia entered Carthage in support of Maximinus, easily defeating the Gordians. The younger was killed in battle and the older committed suicide by hanging.

Pupienus, Balbinus and Gordian III Try to Tidy Up year of the six emperors

Coin made during Balbinus’ 99-day reign. Reverse shows Balbinus and Pupienus’ hands shaking.

Fearing the wrath of Maximinus upon his return to Rome, the Senate could nonetheless not go back on its rebellion. It elected two of its own members to the throne: Pupienus and Balbinus. The plebeian inhabitants of Rome, who preferred one of their own to rule rather than a pair of upper class patricians, showed their displeasure by rioting and casting sticks and stones at the new emperors.

In order to appease the displeased masses, Pupienus and Balbinus declared the 13-year-old grandson of the elder Gordian, Marcus Antonius Gordianus Pius, as Caesar.

Maximus’ march on Rome did not go as planned. His soldiers suffered from famine and disease during the siege and then eventually turned on him, killing him along with his chief ministers and son Maximus, who had been made deputy emperor. Soldiers carried the father and son’s severed heads into Rome, signifying their support for Pupienus and Balbinus as co-emperors, for which they were pardoned.

When Pupienius and Balbinus returned to Rome, they found the city again in chaos. They managed to calm it, albeit temporarily. Not long after, while arguing over who to attack in an enormous planned military campaign, the Emperors were seized by Praetorian Guard, stripped, dragged through the streets, tortured and killed.

On that day Marcus Antonius Gordianus Pius, or Gordian III, was proclaimed sole Emperor. He ruled from 239 – 244, largely as a figurehead controlled by his advisors, particularly the head of the Praetorian Guard, Timesitheus, who was also his father in law. Gordian III died of unknown causes while campaigning in the Middle East.

The popular boy-emperor Gordian III, credit: Ancienne collection Borghèse ; acquisition, 1807 / Borghese Collection; purchase, 1807

By Graham Land

Published on August 28, 2017 01:30

August 27, 2017

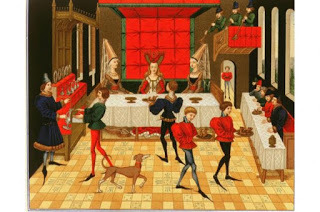

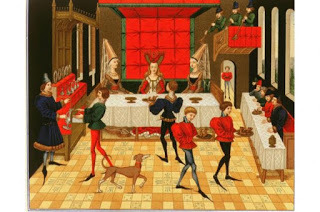

Fit for a queen: 3 medieval recipes enjoyed at English and Scottish royal courts

History Extra

Rys Lumbard Stondyne

Period: England, 14th century

Description: Sweet Rice and Egg Pudding

Original recipe And for to make rys lumbard stondyne, take raw yolkes of eyren, and bete hom, and put hom to the rys beforesaid, and qwen hit is sothen take hit off the fyre, and make thenne a dragée of the yolkes of harde eyren broken, and sugre and gynger mynced, and clowes, and maces; and qwen hit is put in dyshes, strawe the dragée theron, and serve hit forth.

Modern recipe

• 1 cup rice

• 2 cups beef, chicken, or other broth

• 4 raw egg yolks

• 2 tsp sugar, or to taste

• 1/8 tsp saffron

• Salt to taste

Dragées

• 2 hard-boiled egg yolks

• 1 tsp sugar, or to taste

• 1 tsp grated fresh ginger

• 1/8 tsp each cloves and mace

1) In a heavy saucepan or pot combine rice, broth and salt. Over medium heat, bring to a boil, reduce heat and simmer, covered, for about 15 minutes, or until all liquid has been absorbed.

2) When rice is done, stir in raw egg yolks, sugar and saffron, and cook over medium heat, stirring constantly, until the mixture gets very thick. Dish into a lightly oiled mould or bowl, cool, and turn out for serving.

3) To make the dragées, in a bowl combine hard-boiled egg yolks, grated fresh ginger, sugar and spices, and blend into a paste. Roll this paste into little balls about half an inch across, and decorate the moulded Rys Lumbard with them.

Great Pie

Ingredients

• 1 kg mixed game (venison, pheasant, rabbit and boar)

• 2 large onions, peeled and diced

• 1 garlic clove

• 120 grams of brown mushrooms, sliced

• 120 grams smoked back bacon, diced

• 25 grams plain flour

• Juice and zest of 1 orange

• 300 ml chicken stock

• 70 ml of Merlot wine

• Salt and pepper Modern recipe (serves eight to 12)

1) Preheat oven to 180°C.

2) In a frying pan, brown the game.

3) Soften the onions and then add the garlic, mushrooms and bacon and fry for a few minutes. Add the stock and orange juice and zest. Raise it to a boil then simmer for an hour until the meat is tender. 4) Let the mixture cool and add it to your short crust pastry case. Add a pastry lid and press it onto the lip of the base then trim it. Cut a steam hole or two and brush with a beaten egg all over.

5) Put the pie in the oven and bake for one hour. Cool before serving.

Malaches of Pork

Period: England, 14th century

Description: Pork Quiche

Original recipe

Hewe pork al to pecys and medle it with ayren & chese igrated. Do therto powdour fort, safroun & pynes with salt. Make a crust in a trap; bake it wel therinne, and serue it forth.

Modern recipe

(Serves eight to 12)

• Pastry dough for 1 nine-inch pie crust

• 1 pound lean pork, cubed

• 4 eggs

• 1 cup grated, hard cheese

• 1/4 cup pine nuts

• 1/4 tsp salt

• Pinch of each, cloves, mace, black pepper

1) Preheat oven to 230°C.

2) Line a nine-inch pie pan with the pastry dough, and bake it for five to 10 minutes to harden it. Remove it, and reduce oven temperature to 175°C.

3) In a frying pan, over medium heat, brown the cubed pork until it is tender.

4) In a bowl, beat the eggs and spices together.

5) Line the bottom of the pie crust with the browned pork, grated cheese, and pine nuts. Pour the egg and spice mixture over them. 6) Put the pie in the oven and bake for 45 minutes, or until a toothpick draws out clean. Cool before serving

Rys Lumbard Stondyne

Period: England, 14th century

Description: Sweet Rice and Egg Pudding

Original recipe And for to make rys lumbard stondyne, take raw yolkes of eyren, and bete hom, and put hom to the rys beforesaid, and qwen hit is sothen take hit off the fyre, and make thenne a dragée of the yolkes of harde eyren broken, and sugre and gynger mynced, and clowes, and maces; and qwen hit is put in dyshes, strawe the dragée theron, and serve hit forth.

Modern recipe

• 1 cup rice

• 2 cups beef, chicken, or other broth

• 4 raw egg yolks

• 2 tsp sugar, or to taste

• 1/8 tsp saffron

• Salt to taste

Dragées

• 2 hard-boiled egg yolks

• 1 tsp sugar, or to taste

• 1 tsp grated fresh ginger

• 1/8 tsp each cloves and mace

1) In a heavy saucepan or pot combine rice, broth and salt. Over medium heat, bring to a boil, reduce heat and simmer, covered, for about 15 minutes, or until all liquid has been absorbed.

2) When rice is done, stir in raw egg yolks, sugar and saffron, and cook over medium heat, stirring constantly, until the mixture gets very thick. Dish into a lightly oiled mould or bowl, cool, and turn out for serving.

3) To make the dragées, in a bowl combine hard-boiled egg yolks, grated fresh ginger, sugar and spices, and blend into a paste. Roll this paste into little balls about half an inch across, and decorate the moulded Rys Lumbard with them.

Great Pie

Ingredients

• 1 kg mixed game (venison, pheasant, rabbit and boar)

• 2 large onions, peeled and diced

• 1 garlic clove

• 120 grams of brown mushrooms, sliced

• 120 grams smoked back bacon, diced

• 25 grams plain flour

• Juice and zest of 1 orange

• 300 ml chicken stock

• 70 ml of Merlot wine

• Salt and pepper Modern recipe (serves eight to 12)

1) Preheat oven to 180°C.

2) In a frying pan, brown the game.

3) Soften the onions and then add the garlic, mushrooms and bacon and fry for a few minutes. Add the stock and orange juice and zest. Raise it to a boil then simmer for an hour until the meat is tender. 4) Let the mixture cool and add it to your short crust pastry case. Add a pastry lid and press it onto the lip of the base then trim it. Cut a steam hole or two and brush with a beaten egg all over.

5) Put the pie in the oven and bake for one hour. Cool before serving.

Malaches of Pork

Period: England, 14th century

Description: Pork Quiche

Original recipe

Hewe pork al to pecys and medle it with ayren & chese igrated. Do therto powdour fort, safroun & pynes with salt. Make a crust in a trap; bake it wel therinne, and serue it forth.

Modern recipe

(Serves eight to 12)

• Pastry dough for 1 nine-inch pie crust

• 1 pound lean pork, cubed

• 4 eggs

• 1 cup grated, hard cheese

• 1/4 cup pine nuts

• 1/4 tsp salt

• Pinch of each, cloves, mace, black pepper

1) Preheat oven to 230°C.

2) Line a nine-inch pie pan with the pastry dough, and bake it for five to 10 minutes to harden it. Remove it, and reduce oven temperature to 175°C.

3) In a frying pan, over medium heat, brown the cubed pork until it is tender.

4) In a bowl, beat the eggs and spices together.

5) Line the bottom of the pie crust with the browned pork, grated cheese, and pine nuts. Pour the egg and spice mixture over them. 6) Put the pie in the oven and bake for 45 minutes, or until a toothpick draws out clean. Cool before serving

Published on August 27, 2017 01:00

August 26, 2017

Ancient Journeys: What was Travel Like for the Romans?

Ancient Origins

It was not uncommon for the ancient Romans to travel long distances all across Europe. Actually during the Roman Empire, Rome had an incredible road network which extended from northern England all the way to southern Egypt. At its peak, the Empire's stone paved road network reached 53,000 miles (85,000 kilometers)! Roman roads were very reliable, they were the most relied on roads in Europe for many centuries after the collapse of the Roman Empire. It could be argued that they were more reliable than our roads today considering how long they could last and how little maintenance they required.

A Roman street in Pompeii. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Travel by road

Unlike today, travel by road was quite slow and... exhausting! For example, going from Rome to Naples would take over six days in Roman times according to ORBIS, the Google Maps for the ancient world developed by Stanford University. By comparison, it takes about two hours and 20 minutes to drive from Rome to Naples today.

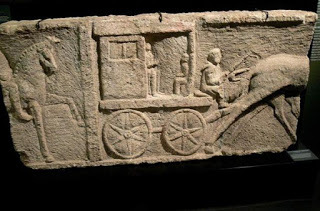

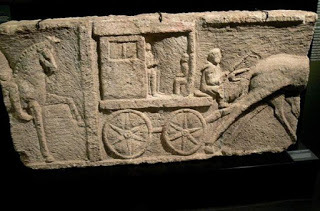

Funeral relief (2nd century ) depicting an Ancient Roman carriage. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Romans would travel in a raeda, a carriage with four noisy iron-shod wheels, many wooden benches inside for the passengers, a clothed top (or no top at all) and drawn by up to four horses or mules. The raeda was the equivalent of the bus today and Roman law limited the amount of luggage it could carry to 1,000 libra (or approximately 300 kilograms).

Rich Romans traveled in the carpentum which was the limousine of wealthy Romans. The carpentum was pulled by many horses, it had four wheels, a wooden arched rooftop, comfortable cushy seats, and even some form a suspension to make the ride more comfortable. Romans also had what would be the equivalent of our trucks today: the plaustrum. The plaustrum could carry heavy loads, it had a wooden board with four thick wheels and was drawn by two oxen. It was very slow and could travel only about 10-15 miles (approximately 15 to 25 kilometers) per day.

Carpentum replica at the Cologne Museum. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The fastest way to travel from Rome to Naples was by horse relay or the cursus publicus, which was like a state-run postal service and a service used to transport officials (such as magistrates or people from the military). A certificate issued by the emperor was required in order for the service to be used. A series of stations with fresh and rapid horses were built at short regular intervals (approximately eight miles or 12 kilometers) along the major road systems. Estimates of how fast one could travel using the cursus publicus vary. A study by A.M. Ramsey in "The speed of the Roman Imperial Post" (Journal of Roman Studies) estimates that a typical trip was made at a rate of 41 to 64 miles per day (66 - 103 kilometers per day). Therefore, the trip from Rome to Naples would take approximately two days using this service.

Because of their iron-shod wheels, Roman carriages made of a lot of noise. That's why they were forbidden from big Roman cities and their vicinity during the day. They were also quite uncomfortable due to their lack of suspension, making the ride from Rome to Naples quite bumpy. Fortunately, Roman roads had way stations called mansiones (meaning "staying places" in Latin) where ancient Romans could rest. Mansiones were the equivalent of our highway rest areas today. They sometimes had restaurants and pensions where Romans could drink, eat and sleep. They were built by the government at regular intervals usually 15 to 20 miles apart (around 25 to 30 kilometers). These mansiones were often badly frequented, with prostitutes and thieves roaming around. Major Roman roads also had tolls just like our modern highways. These tolls were often situated at bridges (just like today) or at city gates.

Travel by sea and river

Man sailing a corbita, a small coastal vessel with two masts. (Public Domain)

There were no passenger ships or cruise ships in ancient Rome. But there were tourists. It was actually not uncommon for well-to-do Romans to travel just for the sake of traveling and visiting new places and friends. Romans had to board a merchant ship. They first had to find a ship, then get the captain's approval and negotiate a price with him. There were a large number of merchant ships traveling regular routes in the Mediterranean. Finding a ship traveling to a specific destination, for example in Greece or Egypt, at a specific time and date wasn't that difficult.

Ancient Roman river vessel carrying barrels, assumed to be wine, and people. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Romans would stay on the deck of the ship and sometimes there would be hundreds of people on the deck. They would bring their own supplies aboard including food, games, blankets, mattresses, or even tents to sleep in. Some merchant ships had cabins at the stern that could accommodate only the wealthiest Romans. It is worth noting that very wealthy Romans could own their own ships, just like very wealthy people own big yachts today. Interestingly, a Roman law forbade senators from owning ships able to carry more than 300 amphorae jars as these ships could also be used to trade goods.

How clay amphorae vessels may have been stacked on a galley. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Traveling by ship wasn't very slow, even compared to modern day standards. For example, going from Brindisium in Italy to Patrae in Greece would take over three days, versus about one day today. Romans could also travel from Italy to Egypt in just a few days. Commercial navigation was suspended during the four winter months in the Mediterranean. This was called the mare clausum. The sea was too rough and too dangerous for commercial ships to sail. Therefore, traveling by sea was close to impossible during the winter and Romans could only travel by road. There were also many navigable rivers that were used to transport merchandise and passengers, even during the winter months.

Traveling during the time of the ancient Romans was definitely not as comfortable as today. However, it was quite easy to travel thanks to Rome's developed road network with its system of way stations and regular ship lines in the Mediterranean. And Romans did travel quite a lot!

Featured image: An ancient Roman road at Leptis Magna, Libya.(CC BY-SA 3.0)

By: Victor Labate

Published on August 26, 2017 00:30