MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 48

August 15, 2017

Little Pompeii’ Unearthed in France is Most Exceptional Roman Site Found in Half a Century

Ancient Origins

In an extensive excavation of a complete Roman neighborhood found near the outskirts of the city of Vienne in the south-east of France, archaeologists have uncovered the remains of affluent houses and public buildings, including extravagant and beautiful mosaics. The huge site, which dates back to the 1st century AD, is exceptionally well preserved and has been described by Benjamin Clement, the lead archaeologist at the dig as, ‘undoubtedly the most exceptional excavation of a Roman site in 40 or 50 years’ reports The Guardian.

The Pompeii Comparison

Vienne is situated on the Rhône River near Lyon, and is already well-known for its Roman history due to a Roman theater and temple in the city. The current excavations in the Sainte-Colombe area began in April and are opening up a huge Roman landscape of 7000 square meters (75,000 sq ft). The site is remarkable not only due to its size but both the diversity of finds and the excellent condition they have been found in. Despite the perhaps merciful lack of petrified corpses, there are similarities to the equally well preserved site in Pompeii, as the neighborhood was abandoned due to fires after 300 years of habitation. Although devastating to the citizens there, the fires will have aided its preservation.

One of the French archaeological team cleaning household artifacts at the site at Sainte-Colombe in Vienne, France (Credit: Jean-Philippe Ksiazek/AFP)

As Mr Clement commented according to the Telegraph, “It was the succession of fires that ended up helping to preserve the buildings and artifacts, although of course they drove the inhabitants out.” Although the devastation was not on the same scale or so rapid at that of Pompeii, the situation and site have similarities in that people deserted the place quickly leaving some of their belongings which were then preserved by ash from the fires. This is providing rich pickings for the archaeologists and hence justifying the moniker Clement attributes to the site of ‘a real little Pompeii in Vienne.’

Huge Area of Well Preserved Roman History

After around a century of contention with the Gallic inhabitants, the ancient city came under full rule of the Roman empire in about 47 BC under Julius Caesar and began to prosper. This neighborhood was diverse but has evidence of a great deal of wealth and included luxury homes, public buildings and communal spaces. One building believed to be the residence of a merchant has been dubbed by the team as ‘The House of Bacchanalia’ due to its floor mosaic scene of maenads (female followers of Bacchus, Roman god of wine) and satyrs. This building had marble tiling, its own water supply system and large gardens and despite being collapsed by the fire, the team believes it will be able to completely restore it, reports the Telegraph.

The site is extensive and covers a whole neighborhood. Image: JEAN-PHILIPPE KSIAZEK/AFP

Another interesting mosaic that is undergoing restoration in another abode is of Thalia, the patron of comedy, with a bare derrière and being abducted by Pan the god of the satyrs. According to the Guardian report, the team plans to painstakingly remove the mosaics and reassemble them so that they will be available for everyone to enjoy at Vienne’s museum of Gallo-Roman civilization by 2019.

As well as mosaics and household items, a large building with a fountain decorated by a statue of Hercules was uncovered which had been constructed on the site of a former market.

The Vienne of Rome

The Temple of Auguste and Livie lit up at night, Vienne, France (CC BY 3.0)

The position Vienne held on the mighty Rhône river was part of the major transport route that connected Lyon, the soon to be capital of Gaul to the north, with Gallia Narbonensis, a Roman settlement in the south. The colonized city made all its inhabitants citizens of Rome and it prospered under successive Caesars, evidence of which exists until this day. Perhaps the most impressive of this evidence is the Temple of Auguste and Livie, which is remarkably well preserved having later been used as a church. There also still exists a theater, the ‘Garden of Cybele’ (Cybele being known by the Romans as Magna Mater or Great Mother) and a pyramid shaped monument that was part of the Roman ‘circus’ or hippodrome

‘Pyramide de Vienne’ Roman era monument (CC BY 3.0)

The position of Vienne in the empire was not accepted by all and there were calls for its destruction by the people of nearby rival town, Lyon. The city lived on despite these troubles, however it suffered due to competing claim of Lyon to be the leading city in the area and by the 3rd century it had declined drastically as Lyon took the lead role in the region. A new city wall was built that was less than a third of the length of the existing 7-kilometer (4.35 miles) wall.

Modern Revelations

Being on the edges of modern Vienne and dated in the first three centuries AD, the current excavation is revealing further the story of a period when the city was at its ancient height of prosperity. It will add a depth of knowledge concerning the daily life and society at the time when the famous monuments - which have been known an admired in the city for two millennia - were erected.

The archaeological site of the Garden of Cybele, Vienne (CC BY SA 3.0)

The excavation of the Sainte-Colombe site will be ongoing until December.

Top image: A well-preserved mosaic on the archaeological site of Sainte-Colombe, Vienne. (Image: Jean-Philippe Ksiazek/AFP)

By Gary Manners

Published on August 15, 2017 01:00

August 14, 2017

Boudicca, the Celtic Queen that unleashed fury on the Romans

Ancient Origins

We British are used to women commanders in war; I am descended from mighty men! But I am not fighting for my kingdom and wealth now. I am fighting as an ordinary person for my lost freedom, my bruised body, and my outraged daughters.... Consider how many of you are fighting — and why! Then you will win this battle, or perish. That is what I, a woman, plan to do!— let the men live in slavery if they will.

These are the words of Queen Boudicca, according to ancient historian Tacitus, as she summoned her people to unleash war upon the invading Romans in Britain. Boudicca, sometimes written Boadicea, was queen of the Iceni tribe, a Celtic clan which united a number of British tribes in revolt against the occupying forces of the Roman Empire in 60-61 AD. While she famously succeeded in defeating the Romans in three great battles, their victories would not last. The Romans rallied and eventually crushed the revolts, executing thousands of Iceni and taking the rest as slaves. Boudicca’s name has been remembered through history as the courageous warrior queen who fought for freedom from oppression, for herself, and all the Celtic tribes of Britain.

Early years

Little is known about Boudicca's upbringing because the only information about her comes from Roman sources, in particular from Tacitus (56 – 117 AD), a senator and historian of the Roman Empire, and Cassius Dio (155 – 235 AD), a Roman consul and noted historian. However, it is believed that she was born into an elite family in the ancient town of Camulodunum (now Colchester) in around 30 AD, and may have been named after the Celtic goddess of victory, Boudiga.

As an adolescent, Boudicca would have been sent away to another aristocratic family to be trained in the history and customs of the tribe, as well as learning how to fight in battle. Ancient Celtic women served as both warriors and rulers, and girls could be trained to fight with swords and other weapons, just as the boys were. Celtic women were distinct in the ancient world for the liberty and rights they enjoyed and the position they held in society. Compared to their counterparts in Greek, Roman, and other ancient societies, they were allowed much freedom of activity and protection under the law.

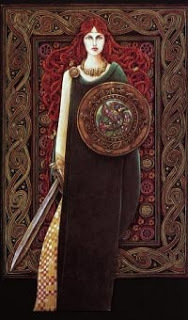

Celtic woman were trained to use swords and other weapons. Image source.

In 43 AD, before the time that Boudicca reached adulthood, the Romans invaded Britain, and most of the Celtic tribes were forced to submit. However, the Romans allowed two Celtic kings to retain some of their traditional power as it was normal Roman practice to allow kingdoms their independence for the lifetime of their client king, who would then agree to leave his kingdom to Rome in his will. One of these kings was Prasutagus, whom Boudicca went on to marry at the age of 18. Their wedding was celebrated for a day and a night and during this time they also gave offerings to the Celtic gods. Together they had two daughters, called Isolda and Siora.

However, it was not a time of harmony for Boudicca and Prasutagus. The Roman occupation brought increased settlement, military presence, and attempts to suppress Celtic religious culture. There were major economic changes, including heavy taxes and money lending.

In 60 AD life changed dramatically for Boudicca, with the death of her husband. As Prasutagus had ruled as a nominally independent, but forced ‘ally’ of Rome, he left his kingdom jointly to his wife and daughters, and the Roman emperor. However, Roman law only allowed inheritance through the male line, so when Prasutagus died, his attempts to preserve his line were ignored and his kingdom was annexed as if it had been conquered.

“Kingdom and household alike were plundered like prizes of war.... The Chieftains of the Iceni were deprived of their family estates as if the whole country had been handed over to the Romans. The king's own relatives were treated like slaves.” — Tacitus

To humiliate the former rulers, the Romans confiscated Prasutagus’s land and property, took the nobles as slaves, publicly flogged Boudicca, and raped their two daughters. This would prove to be the catalyst, which would see Boudicca demanding revenge against the brutal invaders of her lands. Tacitus records the words spoken by Boudicca as she vowed to avenge the actions of the Roman invaders:

“Nothing is safe from Roman pride and arrogance. They will deface the sacred and will deflower our virgins. Win the battle or perish, that is what I, a woman, will do.”

And so Boudicca began her campaign to summon the Britons to fight against the Romans, proving that ‘hell hath no fury like a woman scorned’.

‘Boadicea Haranguing the Britons’ by John Opie. Image source: Wikipedia

Featured image: Artist’s impression of Queen Boudicca. The Celts used to use a plant called Isatis Tinctoria to produce an indigo dye used as war paint. Image credit: beucephalus / deviantart

By April Holloway

Published on August 14, 2017 01:30

August 13, 2017

Millennium Old Structure Unearthed at Medieval Pictish Fort in Scotland

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists have recently uncovered the traces of a millennium old building at the location of the Pictish fort of Burghead in Moray, Scotland. The fort dates back to the time of Alfred the Great and was thought to have been largely destroyed by 19th century development.

Notable Pictish Fort Unearthed

Experts have concluded that the fort was possibly a major source of power for the Pictish kingdom between 500 and 1000. Many notable Pictish artifacts including the Burghead Bull carvings and a mysterious underground well were discovered in the area during the 1800s, but since then it had long been speculated most of the Pictish remains were destroyed when a new town was built on top of the fort at this time. The University of Aberdeen archaeologists overseeing the dig at Burghead Fort near Lossiemouth in Moray, however, have a different opinion and the dig they started in 2015 at Burghead is now uncovering many important clues about the Picts as Live Science reports.

Archaeologists have recently unearthed the traces of an ancient Pictish fort in Scotland underneath an 1800s-era town. (Credit: University of Aberdeen)

The team recently unearthed a Pictish 1,100-year-old longhouse within the fort. Not much is known about Pictish architecture so the new finding could provide very significant information as to the character of Pictish domestic architecture and the nature of activity at major forts such as Burghead. Professor Gordon Noble, Senior Lecturer at the University of Aberdeen, stated as Live Science reports, “Beneath the 19th century debris, we have started to find significant Pictish remains. We appear to have found a Pictish longhouse. This is important because Burghead is likely to have been one of the key royal centers of Northern Pictland and understanding the nature of settlement within the fort is key to understanding how power was materialized within these important fortified sites.”

Excavation site at Burghead (Credit: University of Aberdeen)

Coin of Alfred the Great Found Within the Building

Within the floor layers of the building, an Anglo-Saxon coin of Alfred the Great was found, a fact that indicates the age of the house and fort as the coin dates to the late ninth century when Viking raiders and settlers were leading to drastic changes within Pictish society. Dr. Gordon Noble told Heritage Daily, “There is a lovely stone-built hearth in one end of the building and the Anglo-Saxon coin shows the building dates towards the end of the use of the fort based on previous dating. The coin is also interesting as it shows that the fort occupants were able to tap into long-distance trade networks. The coin is also pierced, perhaps for wearing; it shows that the occupants of the fort in this non-monetary economy literally wore their wealth. Overall these findings suggest that there is still valuable information that can be recovered from Burghead which would tell us more about this society at a significant time for northern Scotland – just as Norse settlers were consolidating their power in Shetland and Orkney and launching attacks on mainland Scotland.”

A coin dated to the era of Alfred the Great was found in the remains of a Pictish fort in Scotland. (Credit: University of Aberdeen)

What do we Really Know about the Picts?

Truth is that we don’t know many things about the Picts, as not much has remained from their peculiar and enigmatic civilization. For that matter, we don’t really know what they called themselves since it was the Romans who “baptized” them Picts (meaning painted people), due to the many characteristic tattoos they had painted all over their bodies.

As a previous Ancient Origins article reports, the Picts have often suffered from the biases of the times, which led to the overgeneralization of their society. Roman historians usually portrayed the Picts as warriors and savages, but contemporary historians are not entirely sure if their Roman counterparts were being as objective as they should with their descriptions. As much as they are known for their body art, the Picts are also known for the variety and quantity of sculpture and artwork that they left, a proficiency that defies their early reputation as uncivilized warriors.

A Pictish Man Holding a Human Head by Theodore de Bry (Public Domain)

Bruce Mann, an archaeologist for Aberdeenshire Council Archaeology Service, said about the new finding as Live Science reported, “Burghead Fort has long been recognized as being an important seat of power during the Early Medieval period, and is known as the largest fort of its type in Scotland. Its significance has just increased again with this discovery. The fact that we have surviving buildings and floor levels from this date is just incredible, and the universities’ work is shedding light on what is too often mistakenly called the ‘Dark Ages’,” implying that the Picts were not as uncivilized as the Romans depicted them to be and have most likely left enough culture behind them, that we just haven’t discovered yet. The dig has been carried out in conjunction with the Burghead Headland Trust and with support from Aberdeenshire Council Archaeology Service.

Top image: Burghead, recognized as an important seat of power during the Early Medieval Period (Credit: University of Aberdeen)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Archaeologists have recently uncovered the traces of a millennium old building at the location of the Pictish fort of Burghead in Moray, Scotland. The fort dates back to the time of Alfred the Great and was thought to have been largely destroyed by 19th century development.

Notable Pictish Fort Unearthed

Experts have concluded that the fort was possibly a major source of power for the Pictish kingdom between 500 and 1000. Many notable Pictish artifacts including the Burghead Bull carvings and a mysterious underground well were discovered in the area during the 1800s, but since then it had long been speculated most of the Pictish remains were destroyed when a new town was built on top of the fort at this time. The University of Aberdeen archaeologists overseeing the dig at Burghead Fort near Lossiemouth in Moray, however, have a different opinion and the dig they started in 2015 at Burghead is now uncovering many important clues about the Picts as Live Science reports.

Archaeologists have recently unearthed the traces of an ancient Pictish fort in Scotland underneath an 1800s-era town. (Credit: University of Aberdeen)

The team recently unearthed a Pictish 1,100-year-old longhouse within the fort. Not much is known about Pictish architecture so the new finding could provide very significant information as to the character of Pictish domestic architecture and the nature of activity at major forts such as Burghead. Professor Gordon Noble, Senior Lecturer at the University of Aberdeen, stated as Live Science reports, “Beneath the 19th century debris, we have started to find significant Pictish remains. We appear to have found a Pictish longhouse. This is important because Burghead is likely to have been one of the key royal centers of Northern Pictland and understanding the nature of settlement within the fort is key to understanding how power was materialized within these important fortified sites.”

Excavation site at Burghead (Credit: University of Aberdeen)

Coin of Alfred the Great Found Within the Building

Within the floor layers of the building, an Anglo-Saxon coin of Alfred the Great was found, a fact that indicates the age of the house and fort as the coin dates to the late ninth century when Viking raiders and settlers were leading to drastic changes within Pictish society. Dr. Gordon Noble told Heritage Daily, “There is a lovely stone-built hearth in one end of the building and the Anglo-Saxon coin shows the building dates towards the end of the use of the fort based on previous dating. The coin is also interesting as it shows that the fort occupants were able to tap into long-distance trade networks. The coin is also pierced, perhaps for wearing; it shows that the occupants of the fort in this non-monetary economy literally wore their wealth. Overall these findings suggest that there is still valuable information that can be recovered from Burghead which would tell us more about this society at a significant time for northern Scotland – just as Norse settlers were consolidating their power in Shetland and Orkney and launching attacks on mainland Scotland.”

A coin dated to the era of Alfred the Great was found in the remains of a Pictish fort in Scotland. (Credit: University of Aberdeen)

What do we Really Know about the Picts?

Truth is that we don’t know many things about the Picts, as not much has remained from their peculiar and enigmatic civilization. For that matter, we don’t really know what they called themselves since it was the Romans who “baptized” them Picts (meaning painted people), due to the many characteristic tattoos they had painted all over their bodies.

As a previous Ancient Origins article reports, the Picts have often suffered from the biases of the times, which led to the overgeneralization of their society. Roman historians usually portrayed the Picts as warriors and savages, but contemporary historians are not entirely sure if their Roman counterparts were being as objective as they should with their descriptions. As much as they are known for their body art, the Picts are also known for the variety and quantity of sculpture and artwork that they left, a proficiency that defies their early reputation as uncivilized warriors.

A Pictish Man Holding a Human Head by Theodore de Bry (Public Domain)

Bruce Mann, an archaeologist for Aberdeenshire Council Archaeology Service, said about the new finding as Live Science reported, “Burghead Fort has long been recognized as being an important seat of power during the Early Medieval period, and is known as the largest fort of its type in Scotland. Its significance has just increased again with this discovery. The fact that we have surviving buildings and floor levels from this date is just incredible, and the universities’ work is shedding light on what is too often mistakenly called the ‘Dark Ages’,” implying that the Picts were not as uncivilized as the Romans depicted them to be and have most likely left enough culture behind them, that we just haven’t discovered yet. The dig has been carried out in conjunction with the Burghead Headland Trust and with support from Aberdeenshire Council Archaeology Service.

Top image: Burghead, recognized as an important seat of power during the Early Medieval Period (Credit: University of Aberdeen)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on August 13, 2017 01:30

August 12, 2017

History's 1st emoji? Ancient pitcher shows a smiley face

Fox News

By Laura Geggel

The iconic smiley face may seem like a modern squiggle, but the discovery of a smiley face-like painting on an ancient piece of pottery suggests that it may be much older.

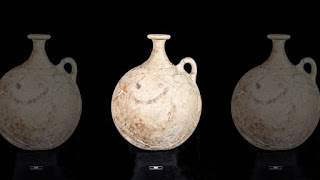

During an excavation of Karkemish, an ancient Hittite city whose remains are in modern-day Turkey near the Syrian border, archaeologists came across a 3,700-year-old pitcher that has three visible paint strokes on it: a swoosh of a smile and two dots for eyes above it.

"The smiling face is undoubtedly there," Nikolo Marchetti, an associate professor in the Department of History and Cultures at the University of Bologna in Italy, told Live Science in an email. "There are no other traces of painting on the flask." [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

The team of Turkish and Italian archaeologists found the pitcher, which dates to about 1700 B.C., in what was a burial site beneath a house in Karkemish, Marchetti said. The pitcher was likely used to drink sherbet, a sweet beverage, he told the Anadolu Agency, a Turkish news outlet.

The archaeologists also found other vases and pots, as well as metal goods in the ancient city, which measures about 135 acres (55 hectares), or slightly more than 100 football fields.

The name Karkemish translates to "Quay of (the god) Kamis," a deity popular at that time in northern Syria. The city was inhabited from the sixth millennium B.C., until the late Middle Ages when it was abandoned, and populated by a string of different cultures, including the Hittites, Neo Assyrians and Romans, the archaeologists said in a statement. It was used once more in 1920 as a Turkish military outpost, the archaeologists added.

British archaeologists visited the site in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but there was still much to be uncovered, so the new team, directed by Marchetti, began excavating it in 2003. But it wasn't until this past field season, which began in May, that the archaeologists unearthed the pitcher with the emoji-like painting.

"It has no parallels in ancient ceramic art of the area," Marchetti told Live Science. "As for the interpretation, you may certainly choose your own."

Original article on Live Science.

Published on August 12, 2017 00:30

August 11, 2017

10 Facts About Healthcare in the Middle Ages

Made from History

BY TOM CROPPER

Medicine in the Medieval period was imprecise and mixed with superstition. The advances made in Antiquity by the Greeks, Romans and Egyptians were scarcely built upon and in some societies, much was forgotten.

Although by the 14th century medical education was growing in Western Europe, Church domination of all aspects of life naturally extended to medicine, further impeding any advanced understanding of the workings of the human body.

Here are 10 facts about medicine and healthcare in medieval times.

1. Eye surgery was conducted with a needle

Cataracts surgery was carried out with a pretty basic needle, which would make more than a few eyes water. This didn’t change until more advanced medical techniques arrived from the Arab world.

2. A surgeon might choose to bore a hole in your head

If you were unwell doctors would occasionally bore a hole in your skull. This was thought to alleviate pressure and was believed to be a cure for many conditions including epilepsy. Needless to say this procedure often proved fatal.

3. Doctors thought too much blood could be bad for you

A painting depicting the letting of blood.

Doctors believed in things called humours – fluids held within the body such as phlegm, bile and blood. Having too much or too little of these, they believed, could make you ill. This is why they often bled patients to relieve an excess of blood.

4. Sheep dung was a form of birth control

It was a long way from the morning after pill, but sheep dung was popularly used as a form of contraceptive.

5. Ill people were thought to be evil

In the Middle Ages much of what happened to us was thought to be down to the way we lived our lives. So people who contracted diseases were often believed to have been guilty of a sin.

6. Going on pilgrimage could cure disease

If you were ill one option could be to go on a long pilgrimage to a holy site.

7. The King’s hands could heal

Edward the Confessor was said to have healing hands. English and French monarchs claimed to be able to heal the sick just by laying their hands on them. Edward the Confessor is the first King said to have this power, but Henry I was the first King to try and use it for political purposes.

8. Spiders had medicinal properties

Spiders and cobwebs held the cure for many diseases.

Cobwebs, for example, were said to be a good cure for warts.

9. Rosemary was a form of toothpaste

In order to brush your teeth the best option was to put burned rosemary into a cloth.

10. Binge drinking was a bigger problem than today

As the Black Death raged across Europe, another plague was following in its wake – drunkenness. People mistakenly believed that alcohol would protect against the disease. Some followed this medicine so completely that they drank themselves to death.

BY TOM CROPPER

Medicine in the Medieval period was imprecise and mixed with superstition. The advances made in Antiquity by the Greeks, Romans and Egyptians were scarcely built upon and in some societies, much was forgotten.

Although by the 14th century medical education was growing in Western Europe, Church domination of all aspects of life naturally extended to medicine, further impeding any advanced understanding of the workings of the human body.

Here are 10 facts about medicine and healthcare in medieval times.

1. Eye surgery was conducted with a needle

Cataracts surgery was carried out with a pretty basic needle, which would make more than a few eyes water. This didn’t change until more advanced medical techniques arrived from the Arab world.

2. A surgeon might choose to bore a hole in your head

If you were unwell doctors would occasionally bore a hole in your skull. This was thought to alleviate pressure and was believed to be a cure for many conditions including epilepsy. Needless to say this procedure often proved fatal.

3. Doctors thought too much blood could be bad for you

A painting depicting the letting of blood.

Doctors believed in things called humours – fluids held within the body such as phlegm, bile and blood. Having too much or too little of these, they believed, could make you ill. This is why they often bled patients to relieve an excess of blood.

4. Sheep dung was a form of birth control

It was a long way from the morning after pill, but sheep dung was popularly used as a form of contraceptive.

5. Ill people were thought to be evil

In the Middle Ages much of what happened to us was thought to be down to the way we lived our lives. So people who contracted diseases were often believed to have been guilty of a sin.

6. Going on pilgrimage could cure disease

If you were ill one option could be to go on a long pilgrimage to a holy site.

7. The King’s hands could heal

Edward the Confessor was said to have healing hands. English and French monarchs claimed to be able to heal the sick just by laying their hands on them. Edward the Confessor is the first King said to have this power, but Henry I was the first King to try and use it for political purposes.

8. Spiders had medicinal properties

Spiders and cobwebs held the cure for many diseases.

Cobwebs, for example, were said to be a good cure for warts.

9. Rosemary was a form of toothpaste

In order to brush your teeth the best option was to put burned rosemary into a cloth.

10. Binge drinking was a bigger problem than today

As the Black Death raged across Europe, another plague was following in its wake – drunkenness. People mistakenly believed that alcohol would protect against the disease. Some followed this medicine so completely that they drank themselves to death.

Published on August 11, 2017 01:00

August 10, 2017

The Disturbing True Story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin

Ancient Origins

When, lo! as they reached the mountain-side, A wondrous portal opened wide, As if a cavern was suddenly hollowed; And the Piper advanced and the children followed, And when all were in to the very last, The door in the mountain-side shut fast. Robert Browning, The Pied Piper of Hamelin: A Child’s Story

Many are familiar with the story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin. Few realise however, that the story is based on real events, which evolved over the years into a fairy tale made to scare children.

For those unfamiliar with the tale, it is set in 1284 in the town of Hamelin, Lower Saxony, Germany. This town was facing a rat infestation, and a piper, dressed in a coat of many coloured, bright cloth, appeared. This piper promised to get rid of the rats in return for a payment, to which the townspeople agreed too. Although the piper got rid of the rats by leading them away with his music, the people of Hamelin reneged on their promise. The furious piper left, vowing revenge. On the 26 th of July of that same year, the piper returned and led the children away, never to be seen again, just as he did the rats. Nevertheless, one or three children were left behind, depending on which version is being told. One of these children was lame, and could not keep up, another was deaf and could not hear the music, while the third one was blind and could not see where he was going.

The earliest known record of this story is from the town of Hamelin itself depicted in a stained glass window created for the church of Hamelin, which dates to around 1300 AD. Although it was destroyed in 1660, several written accounts have survived. The oldest comes from the Lueneburg manuscript (c 1440 – 50), which stated: “In the year of 1284, on the day of Saints John and Paul on June 26, by a piper, clothed in many kinds of colours, 130 children born in Hamelin were seduced, and lost at the place of execution near the koppen.”

The oldest known picture of the Pied Piper copied from the glass window of the Market Church in Hameln/Hamelin Germany (c.1300-1633). Image source: Wikimedia.

The supposed street where the children were last seen is today called Bungelosenstrasse (street without drums), as no one is allowed to play music or dance there. Incidentally, it is said that the rats were absent from earlier accounts, and only added to the story around the middle of the 16 th century. Moreover, the stained glass window and other primary written sources do not speak of the plague of rats.

If the children’s disappearance was not an act of revenge, then what was its cause? There have been numerous theories trying to explain what happened to the children of Hamelin. For instance, one theory suggests that the children died of some natural causes, and that the Pied Piper was the personification of Death. By associating the rats with the Black Death, it has been suggested that the children were victims of this plague. Yet, the Black Death was most severe in Europe between 1348 and 1350, more than half a century after the event in Hamelin. Another theory suggests that the children were actually sent away by their parents, due to the extreme poverty that they were living in. Yet another theory speculates that the children were participants of a doomed ‘Children’s Crusade’, and might have ended up in modern day Romania, or that the departure of Hamelin's children is tied to the Ostsiedlung, in which a number of Germans left their homes to colonize Eastern Europe. One of the darker theories even proposes that the Pied Piper was actually a paedophile who crept into the town of Hamelin to abduct children during their sleep.

One of the darker themed representations of the Pied Piper of Hamelin. Credit: Lui-Gon-Jinn

Historical records suggest that the story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin was a real event that took place. Nevertheless, the transmission of this story undoubtedly evolved and changed over the centuries, although to what extent is unknown, and the mystery of what really happened to those children has never been solved. The story also raises the question, if the Pied Piper of Hamelin was based on reality, how much truth is there in other fairy tales that we were told as children?

Featured image: An illustration of the Pied Piper of Hamelin . Credit: Monlster

Published on August 10, 2017 00:00

August 9, 2017

4 Major Misconceptions About Vikings

Made From History

BY CRAIG BESSELL

There are a lot of misconceptions about Vikings. All fiery rage, horned helmets and relentless pillaging, but this doesn’t paint the proper picture of these men from the north.

1. Vikings Were Not Called Vikings

Perhaps the greatest misconception of these peoples was their name. The word ‘Viking’ was used as a verb rather than a noun. To go raiding was to go viking, and you were going viking as you traveled far from home to search for riches. The word has now come to represent several peoples that came and raided the shores of, not only the kingdoms of Britain, but of Frankia (France) and many other parts of Europe and even as far as Russia. These people were primarily from Scandinavian regions which are now countries like Denmark and Norway.

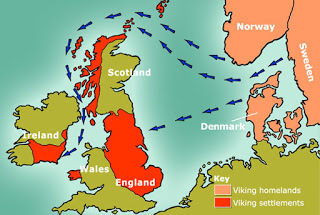

A map showing the routes and destinations of viking expeditions.

These Danes and Norsemen, as they were known, began raiding as a means to survive as their populations expanded. The lands they came from were rocky and sandy, in many places, and offered little in the way of good farm land. So they developed a culture where they took what they needed from others, from lands with richer soil and less warlike tendencies.

2. Beserkers Didn’t Exist

The tales of the berserkers, naked, blood drenched warriors who tore at the opposition’s shield wall with unnatural rage-imbued strength, seem to have been fabricated. The ferocious figures who come up again and again in popular culture seem to have appeared either through misinterpretation of sources or as an artistic whim of writers and historians who appear to have conjured these characters up. Unfortunately, no solid evidence suggests that these mythic warriors ever really existed.

This modern imagining of a Viking warrior is pretty dramatic but not really representative of the historical viking.

3. Vikings Didn’t Have Horned Helmets

The horned helmet is really just a myth, a fanciful addition to the ‘barbarian’ persona attached again by misinterpretation of the evidence and perpetuated within popular culture. There is no historical evidence at all that suggests they wore such helmets in battle. Though they may have used them for ceremonial purposes. They were a fighting people and smart in warfare, a helmet with large protrusions would be more of an unnecessary hindrance and they would likely have mocked such a design.

This kind of helmet would almost definitely have looked alien to a medieval norseman.

4. Vikings Didn’t Depend on Pillaging Alone

They sailed ready for war and often encountered it, but as the years went by and the raiding parties grew larger, the focus was on settlement and an easy life rather than a lightning raid and a return to icy shores. By the middle of the ninth century AD, the men of the north decided they didn’t want to just pillage Britain, they wanted to stay. They came in their thousands and by the year 878AD they had all but conquered the entirety of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Many years of struggle followed, but away from the fighting, mainly in the north of the country, warriors brought their families over the sea and settled into a peaceful farming existence.

Despite their fearsome reputation, it is often beneficial to remember that they were just men and like most others they craved a good life for them and their families. They did not constantly seek out war, but rather saw it as a means to a comfortable retirement on lush green shores.

Published on August 09, 2017 00:30

August 8, 2017

Sam’s historical recipe corner: Coronation chicken

History Extra

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates coronation chicken - a chicken dish dreamt up for a special royal occasion.

Coronation chicken was created in 1953, when renowned florist Constance Spry and cordon bleu chef Rosemary Hume catered for a banquet to celebrate the coronation of Elizabeth II. It is believed to be inspired by the ‘Jubilee Chicken’ created for George V’s silver jubilee in 1935.

At the time the recipe was widely published so it could be enjoyed at street parties across Britain. But, with postwar rationing still in place, the ingredients would have been hard to come by.

Ingredients

2 roasting chickens (I used 2.75 lbs chicken drums and thighs) water and a little wine

1 carrot

1 bouquet garni

salt and 3–4 peppercorns

For the sauce:

2oz chopped onion

2 tsp curry powder

1 tsp tomato purée

1 wine glass of red wine

¾ wine glass of water

1 bay leaf salt, sugar, pepper

1–2 slices of lemon

1 squeeze of lemon juice

1–2 tbsp apricot purée (or apricot jam)

¾ pint mayonnaise (I used 28 tbsp)

2–3 tbsp whipped cream, plus a little more

1 tbsp oil

Method

Poach the chicken with carrot, bouquet, salt and peppercorns in water and a little wine, for about 40 minutes or until tender. Allow to cool in the liquid and remove bones.

Cream of curry sauce: Fry the onion in oil for 3-4 minutes, then add curry powder. Fry for a further 1–2 minutes. Add tomato purée, wine, water, and bay leaf. Bring to boil, add lemon slices and juice, pinch of salt, pepper and sugar. Simmer uncovered for 5–10 minutes. Strain and cool.

Add mayonnaise and apricot purée in stages. Season, and add more lemon juice if necessary. Mix in the whipped cream. Coat the chicken in the sauce and mix in a little extra cream and seasoning. Serve with rice salad and a little extra sauce.

Rice salad: The salad comprised rice, cooked peas, diced raw cucumber, finely chopped mixed herbs and French dressing.

Verdict The original version has many more subtle wine and herb-infused flavours than the bright yellow, sultana-laden, modern sandwich filler!

Difficulty: 4/10

Time: 1 1/2 hours

Based on the original 1953 recipe from The Constance Spry Cookery Book by Rosemary Hume and Constance Spry.

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates coronation chicken - a chicken dish dreamt up for a special royal occasion.

Coronation chicken was created in 1953, when renowned florist Constance Spry and cordon bleu chef Rosemary Hume catered for a banquet to celebrate the coronation of Elizabeth II. It is believed to be inspired by the ‘Jubilee Chicken’ created for George V’s silver jubilee in 1935.

At the time the recipe was widely published so it could be enjoyed at street parties across Britain. But, with postwar rationing still in place, the ingredients would have been hard to come by.

Ingredients

2 roasting chickens (I used 2.75 lbs chicken drums and thighs) water and a little wine

1 carrot

1 bouquet garni

salt and 3–4 peppercorns

For the sauce:

2oz chopped onion

2 tsp curry powder

1 tsp tomato purée

1 wine glass of red wine

¾ wine glass of water

1 bay leaf salt, sugar, pepper

1–2 slices of lemon

1 squeeze of lemon juice

1–2 tbsp apricot purée (or apricot jam)

¾ pint mayonnaise (I used 28 tbsp)

2–3 tbsp whipped cream, plus a little more

1 tbsp oil

Method

Poach the chicken with carrot, bouquet, salt and peppercorns in water and a little wine, for about 40 minutes or until tender. Allow to cool in the liquid and remove bones.

Cream of curry sauce: Fry the onion in oil for 3-4 minutes, then add curry powder. Fry for a further 1–2 minutes. Add tomato purée, wine, water, and bay leaf. Bring to boil, add lemon slices and juice, pinch of salt, pepper and sugar. Simmer uncovered for 5–10 minutes. Strain and cool.

Add mayonnaise and apricot purée in stages. Season, and add more lemon juice if necessary. Mix in the whipped cream. Coat the chicken in the sauce and mix in a little extra cream and seasoning. Serve with rice salad and a little extra sauce.

Rice salad: The salad comprised rice, cooked peas, diced raw cucumber, finely chopped mixed herbs and French dressing.

Verdict The original version has many more subtle wine and herb-infused flavours than the bright yellow, sultana-laden, modern sandwich filler!

Difficulty: 4/10

Time: 1 1/2 hours

Based on the original 1953 recipe from The Constance Spry Cookery Book by Rosemary Hume and Constance Spry.

Published on August 08, 2017 01:30

August 7, 2017

How Were Anglo-Saxon Marriage Ceremonies Different From Modern Weddings?

Made From History

BY CRAIG BESSELL

Weddings, for the people of Dark Age Britain, were more business arrangements than declarations of love. There were several formal customs to adhere to, mainly regarding money, before the marriage could be sealed.

Marriage Was Like a Business Transaction The contract of marriage was settled on between the prospective groom and the father of the bride. Terms would be discussed in the presence of witnesses from both sides before an agreement could be reached, upon which both groom and the bride’s father would shake hands, officially sealing the contract.

The men of both families would meet first to discuss the terms of the marriage contract.

The three financial parts of the contract were:

Morning Gift

A set amount agreed by the groom and father-in-law that the former must pay to his wife the morning after the wedding. This gift of money was to ensure the financial security of the bride and provide some independence. This sum was the woman’s to keep indefinitely and would help to support her and any children if anything were to happen to her husband.

Handgeld

Another gift of money was given to the family of the bride. This monetary exchange showed that the groom was able to look after his future wife financially and it also acted as an act of compensation for the bride’s family because she was leaving them. Essentially the groom would buy his wife.

The groom had to spend quite a lot just to have the wedding agreed upon, however the bride’s family also had to present some money.

Bride’s Dowry

This was paid by her family to her. It was similar to the Morning Gift in that the money was the bride’s to do with what she would and in theory would support her in the event that anything happened to her husband.

The various financial agreements could be paid in coins, a certain amount of raw precious metal, or even in land and livestock.

This businesslike agreement may seem strange, but these were uncertain times. Death could be lurking behind any bush, hill or tree in the shape of a marauding Viking, another Saxon war-band, the Welsh or, even more likely, disease. The above financial agreement would ensure the bride was cared for in the likely event that her husband should die.

A Ceremony of Ritual and Religion

The actual wedding was much less businesslike, though there were many traditions to be adhered to. A wedding was usually the time for a wash; a unique event in these times, most people washing only twice a year at most. Both bride and groom would bathe separately the night before the wedding and would not be allowed to see each other until the day of the ceremony.

On the day, both would be dressed in their best clothes and the groom would be wearing his ancestral sword. The bride would arrive preceded by a member of her family carrying a new sword to be presented to the groom. A priest or Weofodthegn would officiate the ceremony. A Weofodthegn was a priest of the Old Saxon religion, with gods like Woden and Thunor.

The priest would first bless the union, calling on the gods to look favourably upon the couple. Frige, the mother of the gods, would be the deity most called upon, as she was the goddess of love, fertility and marriage.

Next there would be the official exchange of swords. The groom would receive the new blade, provided by the bride’s family, and the bride would receive the groom’s family’s ancestral sword to one day pass on to their eldest son and heir.

Found in Abingdon, Oxfordshire this hilt, and what is left of the blade, is a good exmple of the Saxon swords exchanged during the ceremony.

Then another exchange would take place, one more familiar to a modern audience — the exchange of rings. The groom would also present the keys to his house to his new wife. This represented him bestowing upon her governance of the household, just as the sword he received earlier represented his protection of that home.

Finally, the Weofodthegn would pronounce them wedded and at last everyone could celebrate.

Eat, Drink and Be Married

When the solemn ceremony was over and the marriage contract sealed, the Saxons woud feast and celebrate.

A reception would be held after the wedding, similar to a modern one. The couple and their families would eat, drink and make merry, all the while toasting the gods and asking for blessings for the marriage.

For a month after the wedding the couple would drink mead every day. Mead is an alcoholic beverage made from honey, quite popular at the time. This month was called the hunigmonap, or honeymoon, for this reason.

Published on August 07, 2017 01:30

August 6, 2017

5 Myths About Richard III

Made from History

BY GRAHAM LAND

Richard of Gloucester, better known as Richard III, ruled England from 1483 until his death in 1485 at the battle of Bosworth. Most of our impressions about what kind of man and king he was are rooted in how he is represented in Shakespeare’s eponymous play, which was largely based on the propaganda of the Tudor family.

However, facts about the much-maligned regent don’t always match up to his fictional portrayals.

Here are 5 myths about Richard III that are either inaccurate, unknowable or just plane untrue.

Engraving of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth

1. He Was An Unpopular King

The impression we have of Richard as an evil and treacherous man with a murderous ambition mostly comes from Shakespeare. Yet he was probably more or less well liked.

While Richard was certainly no angel, he enacted reforms that improved the lives of his subjects, including the translation of laws into English and making the legal system more fair. His defence of the North during the rule of his brother also improved his standing among the people. Furthermore, his assumption of the throne was approved by Parliament and the rebellion he faced was a typical occurrence for a monarch at the time.

2. He Was a Hunchback With a Shrivelled Arm

There are some Tudor references to Richard’s shoulders being somewhat uneven, and the examination of his spine shows evidence of scoliosis, yet none of the accounts from his coronation mention any such physical characteristics. More proof of posthumous character assassination are x-rays of portraits of Richard that show they were altered to have him appear hunchbacked. At least one contemporary portrait shows no deformities.

3. He Killed the Two Princes in the Tower

The Princes in the Tower

After the death of their father, Edward IV, Richard lodged his two nephews — Edward the V of England and Richard of Shrewsbury — in the Tower of London in preparation for Edward’s coronation. Instead, Richard became king and the two princes were never seen again.

Though Richard certainly had a motive to kill them, there has never been any evidence discovered that he did, nor that the princes were even murdered. There are also other suspects, such as Richard III’s ally Henry Stafford and Henry Tudor, who executed other claimants to the throne. In the following years at least two people claimed to be Richard of Shrewsbury, leading some to believe that the princes were never murdered.

4. Richard III Was a Bad Ruler

Like the claims of unpopularity, evidence does not support this assertion, which is mostly founded upon the opinions and contentions of the Tudors. Evidence suggests that Richard was an open-minded regent and talented administrator. In his brief reign he encouraged foreign trade and the growth of the printing industry as well as establishing — under his brother’s rule —the Council of the North, which lasted until 1641.

5. Richard Poisoned His Wife

Anne Neville was Queen of England for most of her husband’s reign, but died in March 1485, 5 months before Richard III’s death on the battlefield. By contemporary accounts the cause of Anne’s death was tuberculosis, which was common at the time.

Though Richard grieved publicly for his deceased wife, there were rumours that he poisoned her in order to marry Elizabeth of York, but what evidence we have generally refutes this, as Richard sent Elizabeth away and even later negotiated for her marriage with the future King of Portugal, Manuel I.

An 1890 painting of Anne Neville and a hunchbacked Richard III

Published on August 06, 2017 01:30