MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 52

July 6, 2017

Tower Bridge: Uncovering the history of a London landmark

History Extra

Tower Bridge bridgemaster AP Rabbit and his crew. The unsung heroes of the bridge’s history are being celebrated in a new exhibition. (Tower Bridge)

The story of Tower Bridge really begins well before its official opening on 30 June 1894. Throughout the 19th century the growing traffic congestion in London increased the calls for an additional river crossing and finally in 1876, a special sub-committee was set up to tackle the issue. After some public wrangling, a royal assent for a new bridge was granted in 1885, and the Corporation of London (since renamed the City of London Corporation) launched a design competition. The winner was architect and surveyor Horace Jones. In 1866, under Jones’s supervision, a mammoth building project began.

After eight years of construction, employing at times nearly 1,000 workers, Tower Bridge opened in 1894 and quickly became not only an essential part of London’s urban infrastructure but also an undisputed symbol of the city.

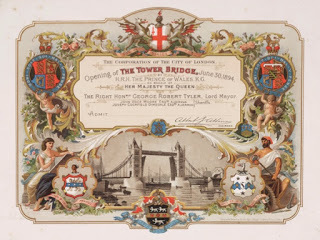

An invitation to the official opening of Tower Bridge in 1894. (Getty Images)

An invitation to the official opening of Tower Bridge in 1894. (Getty Images)Dangerous construction work

Steelworkers, divers, carpenters, painters, riveters, platers, steam crane drivers, holder-ups; countless different trades and companies were involved in the bridge’s construction. Most of the companies involved in the project have since disappeared and the records of their workers with them. Until several years ago, little more than the names of the major architects and engineers were known. Some of these men were real Victorian success stories. William Arrol & Co of Glasgow, for example, was responsible for the steelworks. At the time of construction Arrol’s firm was one of Britain’s leading civil-engineering businesses, involved in major construction projects including the Forth Bridge, Tay Bridge and the gantry [a huge scaffold around a ship’s hull] of the Titanic.

In some cases, like in Newcastle and the Glasgow City Archives, lists and documents have survived. The latter holds the records of William Arrol’s staff, providing a rich source of personal stories, work records and social history. It is because of these records that we now know the names of some of the riveting gangs; the teams of men and boys responsible for hammering the millions of rivets into place that hold the bridge's structure together. These gangs were often made up of families who worked in tandem on site. One such family were the Heaneys: father John, a riveter, and his sons, William, John and Edward.

Work on Tower Bridge could be strenuous and dangerous. (Tower Bridge Exhibition)

The salary for rivet gangs was one pence per rivet; for one week’s work in April 1892 the Heaneys were paid £11 9s 6d as a team. However, the physical exertion and likely hearing damage associated with the job must have taken their toll. Edward’s later army records describe him as 5ft 5in tall with a burn scar on the inside of his right arm - most probably an injury sustained during his gruelling work as a riveter.

Working on Tower bridge could be extremely dangerous, and the building project witnessed tragic fatalities. On 25 April 1888, 20-year-old Richard Bacon fell to his death in the caissons [large cases lowered into the Thames to build the piers]. His death certificate, coroner’s report and the notification for his funeral are still in the family’s possession – a poignant reminder of the often treacherous work involved in building the bridge.

The first known female employee at Tower Bridge was Hannah Griggs, who worked as a cook between 1911 and 1915. Griggs is one of the few women who worked at the bridge in the early years. We know only two more women’s names from this early period, Laura Gass, a tracer [who did drawings and copies of drawings] and Alice Lilly Bode, a clerk. It may well be that both were attracted to the job because of existing family links to the bridge. It was a common occurrence among the bridge’s workforce to already have fathers, siblings or friends working here.

Hannah Griggs, the first known female employee at the Tower Bridge. Griggs worked as a cook between 1911 and 1915. (Tower Bridge Exhibition)

Stunts and capers

The bridge has been a constant magnet for all kinds of reckless, cheeky and occasionally downright criminal behaviour. There is, for example, faded film footage of a strange and intriguing incident in 1917. It shows a man throwing himself off the high-level walkways. He falls for a few seconds towards the river dragging a blooming cloud of dark cloth behind him before splashing into the waters beneath. At that time the walkways were already closed to the public due to lack of use. We do not know if there was an agreement with the then bridge master, John Gass, or if the perpetrator illegally climbed and jumped off the structure, but the fact that the stunt was filmed indicates careful preparation. The jumper’s name was Thomas Hans Orde-Lees, a British adventurer and inventor, born in Aachen, Germany. His aim was to convince the Royal Flying Corps of the benefits of parachutes for the pilots of the fledgling Royal Air Force. His demonstration was successful and the bridge became considered the surprising birthplace of the Royal Parachute Regiment.

Tower Bridge has also been an attractive landmark for attention-grabbing aerial displays, starting in 1912 with Frank McLean – the first of many fly-throughs between the towers and underneath the high-level walkways. Today, of course, such stunts are strictly prohibited.

Capturing imaginations

Kevin McClory may be better known as a producer and writer on the James Bond films Thunderball and Never Say Never Again but in 1959 he directed a little cinematic gem that today is almost forgotten. It is just one example of the bridge’s enormous appeal that transcends its role as a mere river crossing. The Boy and the Bridge tells the story of Tommy, a little boy who runs away to Tower Bridge after a misunderstanding with his father. He strikes up a friendship with a seagull and sets himself up high inside the north tower.

Shot entirely on location, the film is full of fascinating views of a London that still bears the scars of the Second World War. Particularly intriguing are the views from Tommy’s lookout in the north tower of the bridge. He looks over a London cityscape that, apart from a few unmovable landmarks, is near unrecognisable to modern eyes. The contrast becomes all the more striking when night falls and London descends into utter darkness, interrupted by only occasional shards of light – a marked contrast to the shimmering, sparkling, glittering panorama that unfolds today once the sun has set.

The Frederick Cook painting ‘A Flying-bomb Over Tower Bridge’, which depicts the bridge in the midst of the Second World War. Following the war, the London cityscape seen from Tower Bridge was “near unrecognisable to modern eyes”, says Dirk Bennett. (IWM via Getty Images)

The bridge’s appeal in popular culture remains to this day, as indicated by its appearance in blockbuster films such as Mission Impossible and even in computer games such as Assassin’s Creed and Horizon Zero Dawn.

Uncovering the lost voices of Tower Bridge

The bridge has always been an important workplace, however, our knowledge about those who worked there had been scant until a few years ago. Thanks to members of the public sharing their stories and our own targeted research our awareness has now vastly increased.

Finding names of past employees of the bridge resembles detective work: far less is known than you might expect. Some details can be found in the London Metropolitan Archives, but much of it remains the stuff of family folklore, proudly preserved. Visitors can often be overheard referring to relatives who worked at the bridge and much of what is now on display in our new permanent exhibition in the Victorian Engine Rooms is the result of our many conversations with these visitors. Many of the new records come from visitors, descendants of former employees, who often keep documents, photographs and personal mementoes in the family

Stan Fletcher, a bridge foreman. “Finding names of past employees of the bridge resembles detective work”, says Dirk Bennett. (Tower Bridge Exhibition)

The findings are often surprising, even to the families. After his death, one former employee, Edward ‘Ted’ Forrest, was found to have kept two scrap books documenting his time at the bridge. For more than 30 years he collected information about events and incidents, often forgotten but always fascinating. Thanks to his son, some of that information is now accessible to visitors. Another visitor, whose great-grandfather Charles Bull rose from stoker to bridge driver in the early 20th century, felt compelled to start her own research project and has since uncovered the names of over 150 members of staff who worked at the bridge since 1894.

Preserving these voices is a task that the bridge’s current staff embrace. They are not just part of the story of a national landmark but also of London’s social and cultural history. The names of many of those involved in the bridge’s history are now celebrated in a ‘Walk of Fame’; a series of plaques on the bridge’s south-east footpath unveiled in Spring 2017.

Yet there is still much more research to be done. For example, the names of the divers who in long and tiring shifts worked to clear the riverbed in preparation for the bridge’s massive foundations are yet to be uncovered. And so our research goes on. As do our conversations with the relatives of the unsung heroes who helped make Tower Bridge the national treasure it is today.

Dirk Bennett is the Exhibition Development Manager at the Tower Bridge Exhibition. If you have any personal stories or family connections to Tower Bridge

Published on July 06, 2017 01:30

July 5, 2017

10 Innovative Medieval Weapons: You Would Not Want To Be At The Sharp End Of These!

Ancient Origins

Long before modern warfare, there was a time of knights in shining armor atop equally armored horses fighting for the hand of a maiden or in pitched battle. However, the weapons that these knights wielded expanded far past that of an ordinary sword and shield. Listed here are ten strange and deadly weapons used in the medieval period spanning across hundreds of years and reaching across the globe. While these weapons were not used regularly, they do provide an interesting window into medieval warfare and the advances in technology that were being made at that time.

The Gun Shield

The gun shield was exactly what its name would suggest, it was a shield with a breech loading match lock pistol at its center with a small square window about the barrel as an observation port. The shield is believed to have been used by the personal body guard of Henry VIII around 1544-1547.

Gun shield. (c. 1545-1550) (Public Domain)

Although many examples of gun shields have been found in England, they are thought to be of Italian origin and were offered to King Henry VIII in a letter from the Italian painter Giovanbattista. In this letter, they are described as, “several round shields and arm pieces with guns inside them that fire upon the enemy and pierce any armour.” The Italian version of the gun shield was more delicate and light - to be used in hand to hand combat, compared to the English version - which was typically used on a ship. This technology soon died out.

The Spring Loaded Triple Dagger appeared to be a normal dagger at first glance, but when the wielder pressed a release the two spring-loaded side daggers emerged - making the single dagger into a sort of trident. At the time, daggers were used as a side weapon in case the combatant had lost their primary. As such, daggers had extremely sharp points as opposed to sharpened sides, making it more effective as a stabbing weapon that could pierce armor. The usefulness of the triple dagger came in its versatility, one could use it as a simple dagger to stab, or as the triple pronged version to inflict more damage. It was effective at capturing the weapons of other opponents and parrying in exhibition combat. This weapon was used by fencers in Europe in the middle ages as it was far too expensive to ever see actual battle.

Left hand dagger with spring blades that can be opened by pressing a button, c. 1620. (Public Domain)

The Urumi

The Urumi was a very flexible long sword made from either steel or brass, and was often treated as a metal whip. It was often made up of multiple fine metal blades attached to a single handle, in some cases there could be as many as 30 blades in one sword. The weapon originated in the southern states of India, being known as far back as the Mauryan Empire. While being deadly to the opponent, it was also very dangerous to the wielder. In Medieval India, only the most well-trained Rajput warriors could practice with the Urumi as it required perfect coordination, concentration, and agility. The wielders would be taught to follow and control the momentum of the weapon and the techniques included spins and other agile moves. These spins made the weapon well suited to fight against multiple opponents at once.

Fighters using urumi. (CC BY SA)

Greek Fire

Greek Fire was an incendiary material which could be shot from a ship and would burn on the top of water. It was said that in the 7th century a Byzantine architect by the name of Kallinikos invented Greek Fire and used it to defend Constantinople against an Arab fleet. In the west, the term “Greek Fire” was applied to incendiary weapons also used by the Mongols, Chinese, and Arabs. However, what set the Byzantine Greek Fire apart was their use of pressurized nozzles to project the liquid onto the enemy. While the composition is unknown, it has been suggested that the ingredients could be a mixture of pine resin, naphtha, quicklime, calcium, phosphide, sulfur, or niter.

Image from an illuminated manuscript, the Madrid Skylitzes, showing Greek fire in use against the fleet of the rebel Thomas the Slav. (Public Domain)

The Man-Catcher

The Man-Catcher was a long-shafted pole arm with a two-headed prong on the end that looked like a collar. It was typically used to pull a rider from his horse and was often used to capture royals for ransom since it did not wound the captee. It was expected that the armor of the captee would protect them against being injured by the metal prongs of the man-catcher. However, if the rider was not wearing any armor they may suffer some wounds from the spikes on the inner ring of the prongs. A similar weapon, the sasumata, was found in Japan. It was more of a speared fork but could have padding on it, and it was used in extreme circumstances such as riots as a form of crowd control.

Man Catcher, Germany, 1601-1800 (Wellcome Images CC by 4.0)

The Claw of Archimedes

The Claw of Archimedes was much like the man-catcher but much, much larger. In the 3rd century it was designed by Archimedes to protect the city of Syracuse against the Roman navy. As a response to the catapults built by Archimedes, the Romans began to lash their ships together and outfitted them with giant ladders which they used to climb the seawalls. The Claw was a ship-capturing mechanism with crane-like wooden arms that had hooks at the end of them. The hooks were positioned to lift and capsize the ships that were immediately below the seawall. The people of Syracuse were able to fight off invasions for three years due to this invention.

Detail of a wall painting of the Claw of Archimedes sinking a ship, taking the name "iron hand" in ancient sources. (Public Domain)

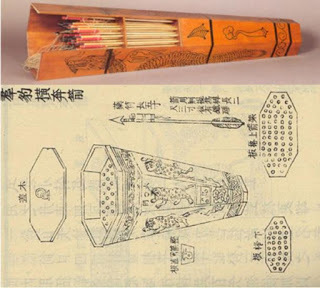

The Nest of Bees

The Nest of Bees consisted of hexagonal tubes filled with dozens of rocket-tipped arrows. The tubes would broaden at the top to aid in the dispersal of the arrows once the nest opened. This weapon could fire off more than two dozen arrows at a time in the same direction. The arrows were often tipped with poison or flammable material. The Nest of Bees was probably invented around the 11th century, during that time that the Chinese were experimenting with gun powder and rocket technology. They were more widely used in the Ming Dynasty. Thousands of these weapons would be deployed simultaneously, raining down death upon the enemy. Not only was this weapon deadly, it acted as a psychological weapon as well due to the noise and smoke that it would emit.

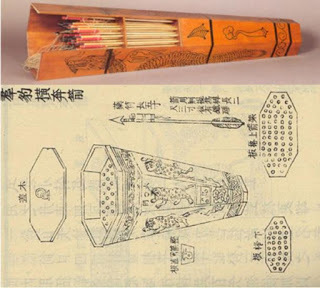

An example (reallycoolweapons) and drawing of ‘the nest of bees.’ (Public Domain)

The Zhua

The Zhua, meaning “claw,” was an Ancient Chinese weapon that consisted of a clawed iron hand on the end of a 6-foot (1.83-meter) pole. Much like the Triple Dagger, it was used to disarm an enemy as well as move shields out of the way. However, the Zhua could also be used for ripping and tearing at the enemy, or, out of sheer weight, it could be used to bludgeon an opponent to death.

Zhua. ( reallycoolweapons)

The Lantern Shield

The Lantern Shield has been called the “swiss army knife of weapons” as it housed many items on one shield. It was a small shield in the shape of a buckler and its defining feature was a hook on which one could hang a lantern. This feature was intended to blind the opponent in battles fought in the dark. More elaborate examples of the lantern shield could include gauntlets, spikes, sword blades, as well as a dimmer for the lantern. Fencing manuals from the 16th and 17th centuries integrated a lantern into the lessons of the swordsman, using it to parry and blind. In general, it is believed that the lantern shield was never actually used in combat, but rather for patrolling Italian city streets at night.

A Lantern Shield. ( Youtube Screenshot )

The Kpinga was a throwing knife used by warriors of the Azande tribe of Nubia in Africa. Also nicknamed the “Hunga Munga,” the knife had three blades that protruded from the center and varied in shape and size. This weapon was often carried into battle on the back of the warrior attached to their oblong Zande shield. The blade would only be thrown after a few spears were loosened and the wielder called to alert their companions. A Kpinga was only given to professional warriors and was considered a symbol of power. Upon marriage, the Kpinga was presented from the groom to the family of the bride.

Kpinga. (Tropenmuseum, part of the National Museum of World Cultures /CC BY SA 3.0 ) The Kpinga

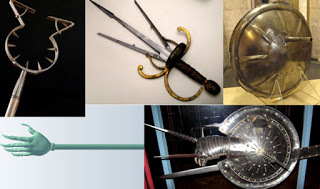

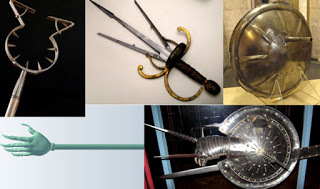

Top Image: Strange Medieval weapons (L-R) Man catcher, Germany, 1601-1800 (Wellcome Images/ CC BY 4.0 ), Left hand dagger with spring blades that can be opened by pressing a button, c. 1620 ( Public Domain ), Gun shield, c. 1540. Exhibit in the Higgins Armory Museum ( Public Domain ), Zhua ( reallycoolweapons), and The Lantern Shield. ( Youtube Screenshot )

By Veronica Parkes

Long before modern warfare, there was a time of knights in shining armor atop equally armored horses fighting for the hand of a maiden or in pitched battle. However, the weapons that these knights wielded expanded far past that of an ordinary sword and shield. Listed here are ten strange and deadly weapons used in the medieval period spanning across hundreds of years and reaching across the globe. While these weapons were not used regularly, they do provide an interesting window into medieval warfare and the advances in technology that were being made at that time.

The Gun Shield

The gun shield was exactly what its name would suggest, it was a shield with a breech loading match lock pistol at its center with a small square window about the barrel as an observation port. The shield is believed to have been used by the personal body guard of Henry VIII around 1544-1547.

Gun shield. (c. 1545-1550) (Public Domain)

Although many examples of gun shields have been found in England, they are thought to be of Italian origin and were offered to King Henry VIII in a letter from the Italian painter Giovanbattista. In this letter, they are described as, “several round shields and arm pieces with guns inside them that fire upon the enemy and pierce any armour.” The Italian version of the gun shield was more delicate and light - to be used in hand to hand combat, compared to the English version - which was typically used on a ship. This technology soon died out.

The Spring Loaded Triple Dagger appeared to be a normal dagger at first glance, but when the wielder pressed a release the two spring-loaded side daggers emerged - making the single dagger into a sort of trident. At the time, daggers were used as a side weapon in case the combatant had lost their primary. As such, daggers had extremely sharp points as opposed to sharpened sides, making it more effective as a stabbing weapon that could pierce armor. The usefulness of the triple dagger came in its versatility, one could use it as a simple dagger to stab, or as the triple pronged version to inflict more damage. It was effective at capturing the weapons of other opponents and parrying in exhibition combat. This weapon was used by fencers in Europe in the middle ages as it was far too expensive to ever see actual battle.

Left hand dagger with spring blades that can be opened by pressing a button, c. 1620. (Public Domain)

The Urumi

The Urumi was a very flexible long sword made from either steel or brass, and was often treated as a metal whip. It was often made up of multiple fine metal blades attached to a single handle, in some cases there could be as many as 30 blades in one sword. The weapon originated in the southern states of India, being known as far back as the Mauryan Empire. While being deadly to the opponent, it was also very dangerous to the wielder. In Medieval India, only the most well-trained Rajput warriors could practice with the Urumi as it required perfect coordination, concentration, and agility. The wielders would be taught to follow and control the momentum of the weapon and the techniques included spins and other agile moves. These spins made the weapon well suited to fight against multiple opponents at once.

Fighters using urumi. (CC BY SA)

Greek Fire

Greek Fire was an incendiary material which could be shot from a ship and would burn on the top of water. It was said that in the 7th century a Byzantine architect by the name of Kallinikos invented Greek Fire and used it to defend Constantinople against an Arab fleet. In the west, the term “Greek Fire” was applied to incendiary weapons also used by the Mongols, Chinese, and Arabs. However, what set the Byzantine Greek Fire apart was their use of pressurized nozzles to project the liquid onto the enemy. While the composition is unknown, it has been suggested that the ingredients could be a mixture of pine resin, naphtha, quicklime, calcium, phosphide, sulfur, or niter.

Image from an illuminated manuscript, the Madrid Skylitzes, showing Greek fire in use against the fleet of the rebel Thomas the Slav. (Public Domain)

The Man-Catcher

The Man-Catcher was a long-shafted pole arm with a two-headed prong on the end that looked like a collar. It was typically used to pull a rider from his horse and was often used to capture royals for ransom since it did not wound the captee. It was expected that the armor of the captee would protect them against being injured by the metal prongs of the man-catcher. However, if the rider was not wearing any armor they may suffer some wounds from the spikes on the inner ring of the prongs. A similar weapon, the sasumata, was found in Japan. It was more of a speared fork but could have padding on it, and it was used in extreme circumstances such as riots as a form of crowd control.

Man Catcher, Germany, 1601-1800 (Wellcome Images CC by 4.0)

The Claw of Archimedes

The Claw of Archimedes was much like the man-catcher but much, much larger. In the 3rd century it was designed by Archimedes to protect the city of Syracuse against the Roman navy. As a response to the catapults built by Archimedes, the Romans began to lash their ships together and outfitted them with giant ladders which they used to climb the seawalls. The Claw was a ship-capturing mechanism with crane-like wooden arms that had hooks at the end of them. The hooks were positioned to lift and capsize the ships that were immediately below the seawall. The people of Syracuse were able to fight off invasions for three years due to this invention.

Detail of a wall painting of the Claw of Archimedes sinking a ship, taking the name "iron hand" in ancient sources. (Public Domain)

The Nest of Bees

The Nest of Bees consisted of hexagonal tubes filled with dozens of rocket-tipped arrows. The tubes would broaden at the top to aid in the dispersal of the arrows once the nest opened. This weapon could fire off more than two dozen arrows at a time in the same direction. The arrows were often tipped with poison or flammable material. The Nest of Bees was probably invented around the 11th century, during that time that the Chinese were experimenting with gun powder and rocket technology. They were more widely used in the Ming Dynasty. Thousands of these weapons would be deployed simultaneously, raining down death upon the enemy. Not only was this weapon deadly, it acted as a psychological weapon as well due to the noise and smoke that it would emit.

An example (reallycoolweapons) and drawing of ‘the nest of bees.’ (Public Domain)

The Zhua

The Zhua, meaning “claw,” was an Ancient Chinese weapon that consisted of a clawed iron hand on the end of a 6-foot (1.83-meter) pole. Much like the Triple Dagger, it was used to disarm an enemy as well as move shields out of the way. However, the Zhua could also be used for ripping and tearing at the enemy, or, out of sheer weight, it could be used to bludgeon an opponent to death.

Zhua. ( reallycoolweapons)

The Lantern Shield

The Lantern Shield has been called the “swiss army knife of weapons” as it housed many items on one shield. It was a small shield in the shape of a buckler and its defining feature was a hook on which one could hang a lantern. This feature was intended to blind the opponent in battles fought in the dark. More elaborate examples of the lantern shield could include gauntlets, spikes, sword blades, as well as a dimmer for the lantern. Fencing manuals from the 16th and 17th centuries integrated a lantern into the lessons of the swordsman, using it to parry and blind. In general, it is believed that the lantern shield was never actually used in combat, but rather for patrolling Italian city streets at night.

A Lantern Shield. ( Youtube Screenshot )

The Kpinga was a throwing knife used by warriors of the Azande tribe of Nubia in Africa. Also nicknamed the “Hunga Munga,” the knife had three blades that protruded from the center and varied in shape and size. This weapon was often carried into battle on the back of the warrior attached to their oblong Zande shield. The blade would only be thrown after a few spears were loosened and the wielder called to alert their companions. A Kpinga was only given to professional warriors and was considered a symbol of power. Upon marriage, the Kpinga was presented from the groom to the family of the bride.

Kpinga. (Tropenmuseum, part of the National Museum of World Cultures /CC BY SA 3.0 ) The Kpinga

Top Image: Strange Medieval weapons (L-R) Man catcher, Germany, 1601-1800 (Wellcome Images/ CC BY 4.0 ), Left hand dagger with spring blades that can be opened by pressing a button, c. 1620 ( Public Domain ), Gun shield, c. 1540. Exhibit in the Higgins Armory Museum ( Public Domain ), Zhua ( reallycoolweapons), and The Lantern Shield. ( Youtube Screenshot )

By Veronica Parkes

Published on July 05, 2017 01:00

July 4, 2017

Fourth of July - Happy Birthday USA

Published on July 04, 2017 01:30

July 3, 2017

Multiple Previously Unknown Prehistoric Burial Sites Detected Around Bryn Celli Ddu

Ancient Origins

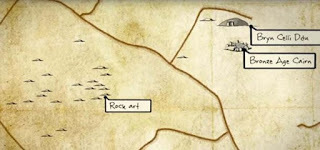

A team of archaeologists has conducted a geophysical survey that has revealed what appears to be a cairn cemetery at the prehistoric ritual area around Bryn Celli Ddu on the Welsh island of Anglesey. This previously unknown manmade landscape could be connected to an even larger complex in the surrounding area in what experts have described as “really exciting stuff.”

Tomb Way Bigger than the Experts Originally Thought

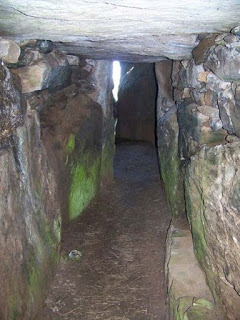

Bryn Celli Ddu, a prehistoric site on the Welsh island of Anglesey that its name means “the mound in the dark grove,” apparently hides more secrets about its past than experts originally thought. Archaeologists have recently detected a prehistoric ritual landscape that may include a cairn cemetery around a 5,000-year-old tomb. Interestingly, archaeologists found out that the tomb, which had been used for thousands of years, was actually way bigger than they initially believed, while on the longest day of the year a beam of sunshine invades in through its main passage, illuminating the entire chamber as Wales Online reports.

Bryn Celli Ddu Passage Tomb is a Neolithic site that overlays an earlier henge monument. (CC BY SA 2.0)

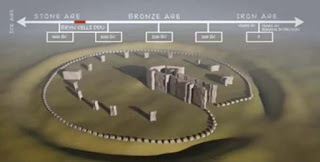

The Legacy of Bryn Celli Ddu

Despite not being as popular as Stonehenge, undoubtedly the most iconic prehistoric monument in the UK, Bryn Celli Ddu is one of Wales’ most impressive and significant ancient historical sites. As Dhwty reports in a previous Ancient Origins article, Bryn Celli Ddu was not only a stone circle, but also operated as a ‘”passage tomb” and was a place to pay tribute to, and protect the remains of ancestors. Archaeologists have suggested that the original stone circles were set up during the Neolithic period, around 3000 BC and it is speculated that during the time of its construction, it was located in a large clearing surrounded entirely by a forest. An outer circular bank and an inner ditch encircled the area, which was originally 21 meters (69 feet) in diameter, and defined the parameters of the monument.

Stone layout of the passage burial mound with timeline. (Youtube Screenshot)

According to archaeologists, the function of Bryn Celli Ddu changed towards the end of the Neolithic, around a thousand years after it was built. Bryn Celli Ddu became a passage tomb, a type of burial monument found around the Irish coastline and some of the standing stones were deliberately destroyed, while a mound was built over the ritual enclosure. Within the mound was a polygonal stone chamber that was reached via an 8 meter (26 foot) long passageway. In 1865 Bryn Celli Ddu was first explored seriously, though it was only in 1928 that a thorough excavation was conducted at the site. At the end of the excavation in 1929, some of the structures were repositioned.

Passageway into Bryn Celli Ddu. The passage opens out to a bigger central chamber. (CC BY SA 2.0)

Researchers Use 3-D Technology and Detect Multiple Cairns

Experts used 3D digital modeling at the Neolithic passage tomb for the first time in order to learn more about its past and usage. According to the re-examination, it now seems that at Bryn Celli Ddu was a large cairn complex or cairn cemetery. As Wales Online explains, a cairn is a man-made pile of stones which is usually used to mark a burial site. Dr. Ben Edwards, from Manchester Metropolitan, that has been investigating the site recently, told Wales Online, “We hit the fields with different geophysical techniques and we found at least four burial cairns. We originally thought it was lone monument but now we know there are four. It seems a complex developed over many years. We call it a cairn cemetery. It is from the Neolithic through to early Bronze age.”

Sketch map showing multiple cairns plus rock art local to Bryn Calli Ddu (Youtube Screenshot)

Apparently, the site has seen human activity for many thousands of years and with several examples of rock art identified as well. Dr. Seren Griffiths, from the University of Central Lancashire, verified the existence of humans at the site by telling Wales Online, “We know that Bryn Celli Ddu sits in a much more complicated landscape than previously thought. Over the last three years, we have discovered 10 new rock art panels and this year the picture has developed to include further evidence for a new Bronze Age cairn along with a cluster of prehistoric pits. We have evidence for over 5,000 years’ worth of human activity in the landscape, ranging from worked flint derived from the tool-making efforts of our prehistoric ancestors to prehistoric burial cairns and pits with pottery deposited within.”

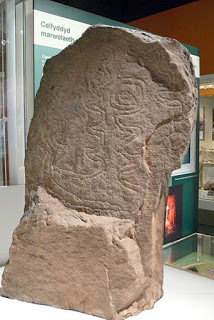

Carved stone from Bryn Celli Ddu tomb, Anglesey. National Museum of Wales (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Impressive Colors and Irish Influence

Dr. Edwards was impressed with both the rock art and the incredible blue color of it, “We don’t dig the monument itself but have investigated the landscape. We have looked at the rock art. This is an incredible blue color but also has colors like gold and fool’s gold. We found that about 10 more rock outcrops with this carved art. Unless you know what you are looking for they are hard to spot,” he told Wales Online. He also added that another interesting thing about the newly found tomb is that it doesn’t look like your typical British monument, “It is much more like what you find in Ireland and this was not coincidence. They were communicating around the Irish Sea,” he said pointing out the obvious Irish influence at the site.

Ultimately, Dr. Ffion Reynolds, from Cadw, couldn’t hide his excitement about the project’s outcome as Daily Post reports, “Since we started the project we have discovered that Bryn Celli Ddu was never in isolation, there was activity happening all around. We knew this would be a good project but it’s turning out to be very exciting.”

Top image: The 5000-year-old burial chamber at Bryn Celli Ddu on Anglesey (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on July 03, 2017 01:30

July 2, 2017

Remains of Saxon Church Discovered on Viking Raided Lindisfarne Island

Ancient Origins

A team of archaeologists have recently excavated the remains of a church on Lindisfarne (Holy Island) in Northumberland. Experts describe the newly discovered church as one of the most significant archaeological finds in the history of the Holy Island.

Extremely Important Archaeological Find

For the first time in over a thousand years, a service was held on Tuesday, June 27, within the boundaries of a recently discovered church on Holy Island in Northumberland as Chronicle Live reports. Peter Ryder, an expert when it comes to historic buildings, has described the newly found church as “probably the most significant archaeology find ever on Holy Island.”

The excavations, directed by Richard Carlton of The Archaeological Practice and Newcastle University, were launched two weeks ago and are expected to finish at the end of this week. “It is a very exciting and hugely significant find,” Mr. Carlton tells Chronicle Live, which also notes that the community archaeology project is part of the Peregrini Lindisfarne Landscape Partnership project, which is sponsored by the Heritage Lottery Fund.

The newly-excavated church remains on Holy Island (Photo Source: ChronicleLive)

New Church Adds Another Chapter to the Holy Island’s Rich Legacy

The dig has unearthed immense sandstone blocks used in the building of the church on The Heugh, a ridge on Holy Island which provides its guests amazing views of the Farne Islands and Bamburgh, which used to be a royal capital of the kingdom of Northumbria. The newly discovered Lindisfarne church is dated prior to the Norman Conquest, with archaeologists estimating that it could possibly date from 630 to 1050 AD, although some of them think that it could be even earlier.

Mr. Carlton tells Chronicle Live, “There are not many churches of potentially the Seventh or Eighth Centuries known in medieval Northumbria, which stretched from the Humber to the Forth. [However], what is in favor of the argument for an early church is that on the ridge it would have been entirely visible from Bamburgh, the seat of political power at the time, and in turn would have had great views of Bamburgh…It adds another chapter to the history of Holy Island.

Lindisfarne Priory, Holy Island (CC BY NC 2.0)

According to the history of the island, St. Aidan initially constructed a wooden church on Lindisfarne in 635 AD. Historians believe that the church was renovated later, even though some suggest that the foundations of the newly unearthed church in Lindisfarne have been placed over the remains of St. Aidan’s original church. Peter Ryder’s theory suggests that the new church could have been built in order to honor and commemorate where St Aidan’s wooden church once stood.

Statue of St.Aidan of Lindisfarne at Lindisfarne Priory (CC BY SA 2.0)

The Viking Element at the Site

According to the scholar, Alcuin of York, the Vikings attacked Lindisfarne in 793 AD. As Inquisitr reports, the vicious attack of the Vikings is described in a letter Alcuin of York wrote to the king of Northumbria, which at the same time happens to be the earliest recorded Viking raid in Britain. The letter mentions, “Pagans have desecrated God’s sanctuary, shed the blood of saints around the altar, laid waste the house of our hope and trampled the bodies of saints like dung in the streets.”

Additionally, The Anglo Saxon Chronicle also recorded the Viking attack on Lindisfarne, in this way marking the Viking invasion to Medieval Europe,

“In this year fierce, foreboding omens came over the land of the Northumbrians, and the wretched people shook; there were excessive whirlwinds, lightning, and fiery dragons were seen flying in the sky. These signs were followed by great famine, and a little after those, that same year on 6th ides of January, the ravaging of wretched heathen men destroyed God’s church at Lindisfarne.”

And while it is a historical fact that the Vikings attacked Lindisfarne, historians are not sure if the newly found church was the one that got sacked by the Vikings, as the island had several churches at that time.

Top image: Lindisfarne Castle on Holy island (CC BY 2.0)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on July 02, 2017 01:30

July 1, 2017

The ancient origins of the legendary griffin

Ancient Origins

The griffin is a legendary creature with the head and wings of an eagle, and the body, tail, and hind legs of a lion. As the eagle was considered the ‘king of the birds’, and the lion the ‘king of the beasts’, the griffin was perceived as a powerful and majestic creature. During the Persian Empire, the griffin was seen as a protector from evil, witchcraft, and slander.

Although the griffin is often seen in medieval heraldry, its origins stretch further back in time. For instance, the ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote “But in the north of Europe there is by far the most gold. In this matter again I cannot say with assurance how the gold is produced, but it is said that one-eyed men called Arimaspians steal it from griffins. But I do not believe this, that there are one-eyed men who have a nature otherwise the same as other men. The most outlying lands, though, as they enclose and wholly surround all the rest of the world, are likely to have those things which we think the finest and the rarest.” (Herodotus, The Histories, 3.116)

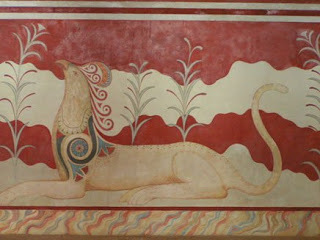

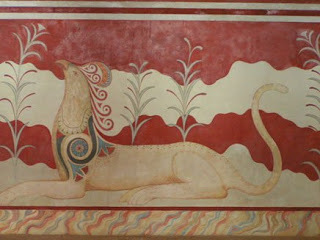

While griffins are most common in the art and mythology of Ancient Greece, there is evidence of representations of griffins in ancient Persia and ancient Egypt dating back to as early as the 4th millennium BC. On the island of Crete in Greece, archaeologists have uncovered depictions of griffins in frescoes in the ‘Throne Room’ of the Bronze Age Palace of Knossos dating back to the 15th century BC.

Griffin fresco in the "Throne Room", Palace of Knossos, Crete. Credit: Wikipedia

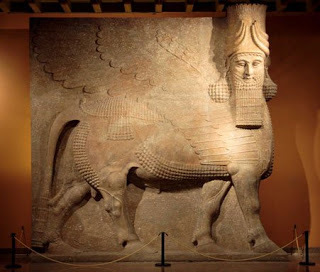

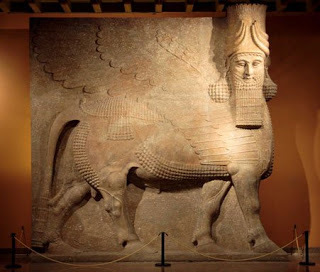

Interestingly, there are various hybrid creatures that are similar to the griffin. For instance, the Lamassu was an Assyrian mythical creature that had the head of a man, a body of a lion or bull, and the wings of an eagle.

The Lamassu, a human-headed winged bull. University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Neo-Assyrian Period, c. 721-705 BCE. Credit: Wikipedia

Further to the east, a part-man, part-bird creature, the Garuda, served as a mount for the Hindu god Vishnu. Perhaps the fascination with such hybrid creatures is due to the fact that it allows people to combine the best characteristics of two or more creatures into one ’super creature’, allowing meaningful symbolism to be attached to them.

Hindu god Vishnu with the Garuda. Image source.

This may hold true for the griffin in the Middle Ages. In European legend of this period, it was believed that griffins mated for life, and that when one partner died, the other would live the rest of his/her without seeking another partner (perhaps due to the fact that there weren’t many griffins around). This has led to claims that the griffin was used by the Church as a symbol against re-marriage. It is unclear, however, whether this was the actual belief, or just a modern interpretation.

Although the griffin might seem like a creature conjured from the imagination of mankind, there might actually be some truth to this creature. One theory suggests that the griffin was brought to Europe by traders travelling along the Silk Road from the Gobi Desert in Mongolia. In this desert, the fossils of a dinosaur called the Protoceratops can be found. As these bones, especially the skull, which has a bird-like beak, were exposed on the desert floor, ancient observers may have interpreted them as proof that such a hybrid creature once lived in the desert. Yet, it has been shown that stories of the griffin have been around even before the Silk Road was developed. Perhaps it was stories about the griffin that made the traders interpret the fossils of the Protoceratops as that of the legendary creature.

Regardless of its origins, the griffin has been part of human culture for a very long time and persists today, as seen in various school emblems, mascots, and even popular literature. It is likely that the griffin and other hybrid mythical creatures will continue to play a role in mankind’s imagination for a long time to come.

Featured image: An artist’s representation of a griffin. Image source.

By Ḏḥwty

The griffin is a legendary creature with the head and wings of an eagle, and the body, tail, and hind legs of a lion. As the eagle was considered the ‘king of the birds’, and the lion the ‘king of the beasts’, the griffin was perceived as a powerful and majestic creature. During the Persian Empire, the griffin was seen as a protector from evil, witchcraft, and slander.

Although the griffin is often seen in medieval heraldry, its origins stretch further back in time. For instance, the ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote “But in the north of Europe there is by far the most gold. In this matter again I cannot say with assurance how the gold is produced, but it is said that one-eyed men called Arimaspians steal it from griffins. But I do not believe this, that there are one-eyed men who have a nature otherwise the same as other men. The most outlying lands, though, as they enclose and wholly surround all the rest of the world, are likely to have those things which we think the finest and the rarest.” (Herodotus, The Histories, 3.116)

While griffins are most common in the art and mythology of Ancient Greece, there is evidence of representations of griffins in ancient Persia and ancient Egypt dating back to as early as the 4th millennium BC. On the island of Crete in Greece, archaeologists have uncovered depictions of griffins in frescoes in the ‘Throne Room’ of the Bronze Age Palace of Knossos dating back to the 15th century BC.

Griffin fresco in the "Throne Room", Palace of Knossos, Crete. Credit: Wikipedia

Interestingly, there are various hybrid creatures that are similar to the griffin. For instance, the Lamassu was an Assyrian mythical creature that had the head of a man, a body of a lion or bull, and the wings of an eagle.

The Lamassu, a human-headed winged bull. University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Neo-Assyrian Period, c. 721-705 BCE. Credit: Wikipedia

Further to the east, a part-man, part-bird creature, the Garuda, served as a mount for the Hindu god Vishnu. Perhaps the fascination with such hybrid creatures is due to the fact that it allows people to combine the best characteristics of two or more creatures into one ’super creature’, allowing meaningful symbolism to be attached to them.

Hindu god Vishnu with the Garuda. Image source.

This may hold true for the griffin in the Middle Ages. In European legend of this period, it was believed that griffins mated for life, and that when one partner died, the other would live the rest of his/her without seeking another partner (perhaps due to the fact that there weren’t many griffins around). This has led to claims that the griffin was used by the Church as a symbol against re-marriage. It is unclear, however, whether this was the actual belief, or just a modern interpretation.

Although the griffin might seem like a creature conjured from the imagination of mankind, there might actually be some truth to this creature. One theory suggests that the griffin was brought to Europe by traders travelling along the Silk Road from the Gobi Desert in Mongolia. In this desert, the fossils of a dinosaur called the Protoceratops can be found. As these bones, especially the skull, which has a bird-like beak, were exposed on the desert floor, ancient observers may have interpreted them as proof that such a hybrid creature once lived in the desert. Yet, it has been shown that stories of the griffin have been around even before the Silk Road was developed. Perhaps it was stories about the griffin that made the traders interpret the fossils of the Protoceratops as that of the legendary creature.

Regardless of its origins, the griffin has been part of human culture for a very long time and persists today, as seen in various school emblems, mascots, and even popular literature. It is likely that the griffin and other hybrid mythical creatures will continue to play a role in mankind’s imagination for a long time to come.

Featured image: An artist’s representation of a griffin. Image source.

By Ḏḥwty

Published on July 01, 2017 01:30

June 30, 2017

How to Train Like an Ancient Roman Gladiator

Roman Fitness Systems

In antiquity, stories of ancient heroes were used to inspire youngsters towards greatness. One story tells of Milo of Croton, the greatest wrestler of his generation.

Milo was so strong that after his victory at the Ancient Olympics, he carried a life-size bronze statue of himself to its stand in the alleyway of heroes at Olympia.

Just like the Olympics today, ancient athletes spent considerable time training in order to win their individual matches, as well as immortality; stories of their feats are still being recounted after generations.

Milo is one such athlete; stories of his discipline and training are legendary.

He came from the city of Croton in Magna Graecia (now in southern Italy) and was a six-time Olympic champion, also winning numerous titles at the Pythian, Nemean, and Isthmian Games.

One mantra of modern training that Milo also used is the progressive overload, where you add heavier and heavier weights as you progress. The story goes that one day, seeing a small bull that had recently been born, he hoisted it onto his shoulders and walked around with it. He got such a good workout out of it that he decided to do it every day.

As the bull grew stronger and larger over time, and so did Milo.

Ancient Heroes: The Gladiators

Forget Spartacus as the greatest gladiator of all time. He’s more famous for leading a revolt than what he accomplished in the arena.

Remember this name: Spiculus.

Spiculus was the Mike Tyson of his day, the greatest fighter of his generation. Men trained in order to be able to look and fight like him, and women threw themselves at his feet.

One way that Spiculus trained was with The Tetrad System. This divided training into 4-day cycles, each focusing on a different type of training.

Day 1 was the day of preparation and consisted of short, high-intensity workouts that prepared the athlete for the next day’s workout.

Day 2 was the killer day. It consisted of long, strenuous exercises and served as an all-out test of the athlete’s potential. He was meant to give 110% during this day.

Day 3 was the rest day. Athletes would either rest or perform only very light exercise. The ancients knew that you needed rest in order to recover and incorporated this principle in their training systems.

Day 4 came after the rest day and consisted of medium intensity exercises. After Day4, the entire cycle was rebooted and started again.

Different gladiator schools used different systems, but The Tetrad System was one of the most popular systems of its time.

Galen, an ancient Roman physician (no, I’m not talking about the smart chimps from Planet of the Apes) got his start at a gladiator school. After treating so many gladiator’s injuries, he developed several principles for training.

The key three were:

1. You need to vary your intensity. Do a proper warm-up and gradually increase the intensity of your workout. Galen taught the gladiators to never start exercising at their full speed.

2. A cool down is important. This principle was stressed by many ancient physicians. In order to prevent injury, you need to cool your body down after an intense effort. Hippocrates, an ancient Greek physician, recommended that everyone take a slow walk after exercising.

3. You need to rest and let your body recover. Rest was very important to the gladiators. In order to aid recovery, many gladiator schools included bathhouses. Like athletes today trying to get rid of all the lactic acid build-up, gladiators would soak in pools of hot and cold water to ease their tired bodies.

Your Attitude is Everything

Seneca compared the life of a gladiator to that of a stoic; the stoic philosophy was incredibly popular in the ancient world and helped many people deal with the stresses of day-to-day life, including gladiators.

Marcus Aurelius (who you might recall from the first few scenes of The Gladiator) was a stoic philosopher who kept a daily journal to keep himself grounded. It was published after his death as Meditations and gives guidance on how to live a good life and stay sane in a world of chaos.

My favorite quote is about how to deal with annoying, petty, or malicious people:

“When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: the people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous, and surly. They are like this because they can’t tell good from evil. But I have seen the beauty of good, and the ugliness of evil, and have recognized that the wrongdoer has a nature related to my own—not of the same blood or birth, but the same mind, and possessing a share of the divine.”

One of the main tenets of stoicism is to focus on the things that you can control and forget about the rest.

You have certain amounts of control over some things and zero control over others. You can control what you eat or if you enter each arena with your game face on, but you cannot control the weather.

If you’re wasting time complaining about things that are out of your zone of control, focus your mental energy on trying to improve things that you can control.

One important aspect of stoicism is learning to accept things as they are or that are inevitable. You’re going to grow old. You’re going to die; it’s inevitable. Stoicism helped people accept that.

The Mind and Body

A gladiator would enter ever arena ready for combat, knowing that he might die that day. This was a given that he had to accept.

Building a healthy mindset was as important to ancient gladiators as was building a strong, capable body. There are certain risks and inevitabilities in life, both of which you can never escape. Like the gladiators, you need to learn to accept them and not let them negatively affect your life.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Peter Burns is a world traveler whose interests include fitness, history, gaining weight, learning languages and a wide variety of other things. He is on a quest to become a superhero. Join him on his journey by checking out his blog, Renaissance Man Journal.

In antiquity, stories of ancient heroes were used to inspire youngsters towards greatness. One story tells of Milo of Croton, the greatest wrestler of his generation.

Milo was so strong that after his victory at the Ancient Olympics, he carried a life-size bronze statue of himself to its stand in the alleyway of heroes at Olympia.

Just like the Olympics today, ancient athletes spent considerable time training in order to win their individual matches, as well as immortality; stories of their feats are still being recounted after generations.

Milo is one such athlete; stories of his discipline and training are legendary.

He came from the city of Croton in Magna Graecia (now in southern Italy) and was a six-time Olympic champion, also winning numerous titles at the Pythian, Nemean, and Isthmian Games.

One mantra of modern training that Milo also used is the progressive overload, where you add heavier and heavier weights as you progress. The story goes that one day, seeing a small bull that had recently been born, he hoisted it onto his shoulders and walked around with it. He got such a good workout out of it that he decided to do it every day.

As the bull grew stronger and larger over time, and so did Milo.

Ancient Heroes: The Gladiators

Forget Spartacus as the greatest gladiator of all time. He’s more famous for leading a revolt than what he accomplished in the arena.

Remember this name: Spiculus.

Spiculus was the Mike Tyson of his day, the greatest fighter of his generation. Men trained in order to be able to look and fight like him, and women threw themselves at his feet.

One way that Spiculus trained was with The Tetrad System. This divided training into 4-day cycles, each focusing on a different type of training.

Day 1 was the day of preparation and consisted of short, high-intensity workouts that prepared the athlete for the next day’s workout.

Day 2 was the killer day. It consisted of long, strenuous exercises and served as an all-out test of the athlete’s potential. He was meant to give 110% during this day.

Day 3 was the rest day. Athletes would either rest or perform only very light exercise. The ancients knew that you needed rest in order to recover and incorporated this principle in their training systems.

Day 4 came after the rest day and consisted of medium intensity exercises. After Day4, the entire cycle was rebooted and started again.

Different gladiator schools used different systems, but The Tetrad System was one of the most popular systems of its time.

Galen, an ancient Roman physician (no, I’m not talking about the smart chimps from Planet of the Apes) got his start at a gladiator school. After treating so many gladiator’s injuries, he developed several principles for training.

The key three were:

1. You need to vary your intensity. Do a proper warm-up and gradually increase the intensity of your workout. Galen taught the gladiators to never start exercising at their full speed.

2. A cool down is important. This principle was stressed by many ancient physicians. In order to prevent injury, you need to cool your body down after an intense effort. Hippocrates, an ancient Greek physician, recommended that everyone take a slow walk after exercising.

3. You need to rest and let your body recover. Rest was very important to the gladiators. In order to aid recovery, many gladiator schools included bathhouses. Like athletes today trying to get rid of all the lactic acid build-up, gladiators would soak in pools of hot and cold water to ease their tired bodies.

Your Attitude is Everything

Seneca compared the life of a gladiator to that of a stoic; the stoic philosophy was incredibly popular in the ancient world and helped many people deal with the stresses of day-to-day life, including gladiators.

Marcus Aurelius (who you might recall from the first few scenes of The Gladiator) was a stoic philosopher who kept a daily journal to keep himself grounded. It was published after his death as Meditations and gives guidance on how to live a good life and stay sane in a world of chaos.

My favorite quote is about how to deal with annoying, petty, or malicious people:

“When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: the people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous, and surly. They are like this because they can’t tell good from evil. But I have seen the beauty of good, and the ugliness of evil, and have recognized that the wrongdoer has a nature related to my own—not of the same blood or birth, but the same mind, and possessing a share of the divine.”

One of the main tenets of stoicism is to focus on the things that you can control and forget about the rest.

You have certain amounts of control over some things and zero control over others. You can control what you eat or if you enter each arena with your game face on, but you cannot control the weather.

If you’re wasting time complaining about things that are out of your zone of control, focus your mental energy on trying to improve things that you can control.

One important aspect of stoicism is learning to accept things as they are or that are inevitable. You’re going to grow old. You’re going to die; it’s inevitable. Stoicism helped people accept that.

The Mind and Body

A gladiator would enter ever arena ready for combat, knowing that he might die that day. This was a given that he had to accept.

Building a healthy mindset was as important to ancient gladiators as was building a strong, capable body. There are certain risks and inevitabilities in life, both of which you can never escape. Like the gladiators, you need to learn to accept them and not let them negatively affect your life.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Peter Burns is a world traveler whose interests include fitness, history, gaining weight, learning languages and a wide variety of other things. He is on a quest to become a superhero. Join him on his journey by checking out his blog, Renaissance Man Journal.

Published on June 30, 2017 02:00

June 29, 2017

Medieval Sword in Excellent Condition Accidentally Found in a Peat Bog in Poland

Ancient Origins

An excavator operator who was working in a peat bog in Poland last month, accidentally discovered a magnificent 14th century longsword, which is in an extremely good condition. Experts believe that this is a unique find to the region.

Stunning 14th Century Sword Discovered in Great Condition

As Gizmodo reports, Wojciech Kot, an excavator operator who discovered the long-sword in the peat bog in the Polish municipality of Mircze, has donated the sword to the Fr. Stanislaw Staszic Museum. Museum experts are currently examining the weapon, while the preparations for an organized archaeological expedition have already started.

Even though the long sword has been corroded over time, archaeologists reassure say that this is normal due to the fact that it had been in the bog for more than six centuries. The only part missing from the long sword is the original hilt, which was thought to have been made from antler, bone or wood.

Initially, the impressive sword measured 47 inches long (120 cm), and weighed only 3.3 pounds (1.5 kg), “The elongated grip was intended for two-handed use which coupled with its long reach and light weight made the sword an agile weapon for armored knights in battle. This design is typical of the 14th century,” notes The History Blog.

The Long Sword. Image: Fr. Stanisław Staszic Museum

The Sword’s Origins

The rear bar of the sword features an isosceles cross inscribed inside the shape of a heraldic shield, which was most likely created by the blacksmith. Museum’s director Bartłomiej Bartecki focused on the find’s uniqueness, “This is a unique find in the region. It is worth pointing out that while there are similar artefacts in museum collections, their places of discovery is often unknown, and that is very important information for historians and archaeologists,” he stated as Gizmodo reports. As to how the sword ended up in a peat bog, Staszic explained, “It’s possible that an unlucky knight was pulled into the marsh, or simply lost his sword.” The History Blog, however, attempts to give a more detailed explanation about the sword’s likely origins:

“The area is first appears on the historical record in the 13th century where it’s mentioned as the site of a few hunting lodges surrounded by forest. The region was part of Ruthenia (aka the Kievan Rus) then and was absorbed by the Kingdom of Poland in 1366 century after the disintegration of the Rus. The Polish governor built a castle in Hrubieszów in the late 14th century. So at least the second half of the century offered good employment opportunity for knights. Or he could have just been riding through and made a wrong turn into the bog.”

The sword found in the peat bog in Poland. Photo: PAP/ Wojciech Pacewicz

Excavation Expected at the Peat Bog

In the coming days, a team of Polish archaeologists will return to the discovery site to carry out limited excavations at the peat bog. No bones have been found near the sword's location, but the team hopes to find any possible artifacts or other belongings from the knight. As for the sword, it is expected to undergo conservation in Warsaw, "This treatment will also help determine its owner. We believe that there could be engraved signs on the blade near the hilt; those were most often made by swordmakers who marked swords for the knights. This could help us determine the origin of the weapon," Bartecki told PAP, and assured that after the conservation and analysis end, the sword will become part of the main exhibition at the Museum in Hrubieszów.

Top image: Bartłomiej Bartecki, director of the Museum in Hrubieszów presents the sword found in the Commune of Mircze. Photo: PAP/ Wojciech Pacewicz

By Theodoros Karasavvas

An excavator operator who was working in a peat bog in Poland last month, accidentally discovered a magnificent 14th century longsword, which is in an extremely good condition. Experts believe that this is a unique find to the region.

Stunning 14th Century Sword Discovered in Great Condition

As Gizmodo reports, Wojciech Kot, an excavator operator who discovered the long-sword in the peat bog in the Polish municipality of Mircze, has donated the sword to the Fr. Stanislaw Staszic Museum. Museum experts are currently examining the weapon, while the preparations for an organized archaeological expedition have already started.

Even though the long sword has been corroded over time, archaeologists reassure say that this is normal due to the fact that it had been in the bog for more than six centuries. The only part missing from the long sword is the original hilt, which was thought to have been made from antler, bone or wood.

Initially, the impressive sword measured 47 inches long (120 cm), and weighed only 3.3 pounds (1.5 kg), “The elongated grip was intended for two-handed use which coupled with its long reach and light weight made the sword an agile weapon for armored knights in battle. This design is typical of the 14th century,” notes The History Blog.

The Long Sword. Image: Fr. Stanisław Staszic Museum

The Sword’s Origins

The rear bar of the sword features an isosceles cross inscribed inside the shape of a heraldic shield, which was most likely created by the blacksmith. Museum’s director Bartłomiej Bartecki focused on the find’s uniqueness, “This is a unique find in the region. It is worth pointing out that while there are similar artefacts in museum collections, their places of discovery is often unknown, and that is very important information for historians and archaeologists,” he stated as Gizmodo reports. As to how the sword ended up in a peat bog, Staszic explained, “It’s possible that an unlucky knight was pulled into the marsh, or simply lost his sword.” The History Blog, however, attempts to give a more detailed explanation about the sword’s likely origins:

“The area is first appears on the historical record in the 13th century where it’s mentioned as the site of a few hunting lodges surrounded by forest. The region was part of Ruthenia (aka the Kievan Rus) then and was absorbed by the Kingdom of Poland in 1366 century after the disintegration of the Rus. The Polish governor built a castle in Hrubieszów in the late 14th century. So at least the second half of the century offered good employment opportunity for knights. Or he could have just been riding through and made a wrong turn into the bog.”

The sword found in the peat bog in Poland. Photo: PAP/ Wojciech Pacewicz

Excavation Expected at the Peat Bog

In the coming days, a team of Polish archaeologists will return to the discovery site to carry out limited excavations at the peat bog. No bones have been found near the sword's location, but the team hopes to find any possible artifacts or other belongings from the knight. As for the sword, it is expected to undergo conservation in Warsaw, "This treatment will also help determine its owner. We believe that there could be engraved signs on the blade near the hilt; those were most often made by swordmakers who marked swords for the knights. This could help us determine the origin of the weapon," Bartecki told PAP, and assured that after the conservation and analysis end, the sword will become part of the main exhibition at the Museum in Hrubieszów.

Top image: Bartłomiej Bartecki, director of the Museum in Hrubieszów presents the sword found in the Commune of Mircze. Photo: PAP/ Wojciech Pacewicz

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on June 29, 2017 01:30

June 28, 2017

Historical recipes: How to make Russian Easter sweet bread Kulich

History Extra

Often baked in a coffee tin so its shape resembles that of the hats of Russian Orthodox priests, kulich remains a tasty treat after the restrictions of Lent. Traditionally it is decorated with the letters XB – Христос Воскресе (Khristos Voskrese – Christ is risen).

Ingredients

Bread:

- 20g dried active baking yeast

- 350ml warm milk

- 200g caster sugar

- 80g sultanas

- 50ml rum

- 750g plain flour, sifted

- 5 eggs

- 1tsp vanilla extract

- pinch of salt

- 250g butter, softened

- 80g almonds

- 80g chopped mixed peel

Icing (optional):

- 1 egg white

- 250g icing sugar

- 1tsp lemon juice

Method

Bread:

Dissolve yeast in 100ml warm milk, add ½tsp sugar.

Soak sultanas in rum.

Sift 120g of flour into a bowl, add remaining 250ml milk and mix well.

Add yeast mixture, cover, and let it stand in a warm place for 30 mins.

Separate egg yolks and beat with sugar until fluffy and pale in colour.

Stir in the rum, add vanilla and mix. In a separate bowl, add a pinch of salt to egg whites. Whisk until peaks form and set aside.

Add egg yolk mixture to yeast mixture and mix. Fold in the egg whites. Add the remaining flour in small batches, mixing well each time.

Knead until dough separates from sides of the bowl. Transfer dough to a flat surface and knead for 10 mins.

When pliable add butter, 50g at a time.

Knead for 2 mins and form into a ball.

Transfer to a lightly oiled bowl, cover with cling film and wrap in a tea towel.

Leave to rise in a warm place for 90 mins. When dough doubles in size, remove and knead for 2 mins. Knead in sultanas, almonds and mixed peel.

Line a tin with baking paper, fill 1/3 full with dough and cover with a tea towel. Leave to prove until dough rises to the top.

Preheat oven to 180°C.

Bake for 45–60 mins.

Icing (optional): Mix raw egg white with icing sugar and lemon juice. Spread over the top of the bread and let it drizzle down the sides.

Difficulty: 4/10

Time: 220 mins

Recipe provided by allrecipes.co.uk

Published on June 28, 2017 01:30

June 27, 2017

Experts map ancient hill forts of UK and Ireland

BBC

Castle Law hill fort, Perth and Kinross. Almost 40% of the hill forts of the UK and Ireland are found in Scotland

The locations and details of all ancient hill forts in the UK and Ireland have been mapped in an online database for the first time.

Scientists found 4,147 sites - ranging from well-preserved forts to those where only crop marks are left.

Researchers from the University of Edinburgh, University of Oxford and University College Cork spent five years on the project.

Nearly 40% are in Scotland, with 408 in the Scottish Borders alone.

Information on all the hill forts has been collated onto a website that will be freely accessible to the public so they can discover details of the ancient sites they see in the countryside.

The University of Edinburgh's Prof Ian Ralston, who co-led the project, said: "Standing on a windswept hill fort with dramatic views across the countryside, you really feel like you're fully immersed in history. "

This research project is all about sharing the stories of the thousands of hill forts across Britain and Ireland in one place that is accessible to the public and researchers."

Brown Caterthun near Edzell, Angus. Sometimes only vegetation marks and remnants of the forts show where they once stood

Prof Gary Lock, from the University of Oxford, said it was important the online database was freely available to researchers and others, such as heritage managers, and would provide the baseline for future research on hill forts.

He added: "We hope it will encourage people to visit some incredible hill forts that they may never have known were right under their feet."

In England, Northumberland leads the way with 271 hill forts, while in the Republic of Ireland, Mayo and Cork each have more than 70 sites.

Powys is the county with the most hill forts in Wales, with 147, and in Northern Ireland, Antrim has the most, with 15.

Hill forts were mostly built during the Iron Age, with the oldest dating to around 1000 BC and the most recent to 700 AD, and had numerous functions, some of which have not been fully discovered.

Hill fort near Alyth, Perth and Kinross. The researchers have found 4,147 sites across the UK and Ireland

Despite the name, not all hill forts are on hills, and not all are forts, the experts said.

Excavations show many were used predominantly as regional gathering spots for festivals and trade, and some are on low-lying land.

The research team from the University of Edinburgh, University of Oxford and University College Cork were funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council to gather information from citizen scientists.

About 100 members of the public collected data about the hill forts they visited, identifying and recording the characteristics of forts, which was then analysed by the team.

Published on June 27, 2017 01:30