MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 54

June 16, 2017

Celtic Prince or Princess? Researchers Have Finally Ascertained Who Owned an Opulent 2500-Year-Old Tomb in France

Ancient Origins

First unearthed in 2015, research on the stunning artifacts found in a rich tomb in Lavau, France are finally coming to light. Scholars have managed to solve the mystery of the tomb’s owner and have provided some other exciting pieces of information on the rich grave goods.

The 2,500-year-old human remains were first discovered in 2015 when archaeologists were exploring a site in preparation for construction of a new commercial center. The tumulus (burial mound) was surrounded by a ditch and palisade. The tomb was said to be larger than the cathedral of nearby Troyes.

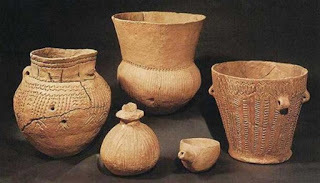

The body found in this huge burial mound was accompanied by a chariot, a vase depicting Dionysus, and a beautiful Mediterranean bronze cauldron adorned with castings of the Greek god Achelous and lions’ heads. These elaborate artifacts, along with a stunning gold necklace, bracelets, and finely worked amber beads adorning the skeleton, asserted the person's elite status.

Artifacts in the Celtic elite’s tomb in 2015. ( Denis Gliksman, Inrap )

The French archaeological agency INRAP said the treasures of the tomb are “fitting for one of the highest elite of the end of the first Iron Age,” and told the media it is one of the most remarkable finds of the Celtic Hallstatt period of 800 to 450 BC.

Initially, the archaeologists were uncertain to whom the tomb pertained, first stating that a large knife found alongside the remains suggested it was made for a man, however, the rich golden jewelry opened the possibility that a Celtic princess may have been buried instead.

Now, IB Times reports the recent analysis of the shape of the pelvic bones has solved that mystery – it is today known as the ‘Lavau prince’s’ tomb.

The recent analysis of the shape of the pelvic bones has solved the mystery of the tomb’s owner – it was a Celtic ‘prince.’ (Denis Gliksman, Inrap )

Furthermore, the recent INRAP analysis of the bronze cauldron has shown researchers that its creator(s) had mastered smelting and engraving techniques. By using X-ray radiography, the researchers have found that the prince’s belt is unique and has Celtic motifs formed with silver threads. An examination of a knife sheath showed fine bronze threads. The researchers also saw that a gold torc and several gold bangles have marks where they rubbed against the prince’s skin.

Finally, chemical analysis and 3-D photography show that a large jar that was used to pour wine combines Greek-style ceramic with golden Etruscan and silver Celtic designs. This is an important discovery for the researchers as it provides more evidence of a mix of cultural influences and supports the presence of economic and social interaction present amongst Celtic and Mediterranean people in the 5th century BC. As INRAP previously explained :

"The tomb contains mortuary deposits of sumptuousness worth that of the top Hallstatt elites. The period between the late 6th Century and the beginning of the 5th Century BC was characterized by the economic development of Greek and Etruscan city-states in the West, in particularly Marseilles. Mediterranean traders come into contact with the continental Celtic communities as they searched for slaves, metals and precious goods (including amber)."

Artifacts from the Celtic Lavau Prince’s tomb. ( Denis Gliksman, Inrap )

The prince’s grave is considered one of the most important archaeological discoveries in France in recent decades and it has been compared to the 1953 unearthing of a grave for the 'Lady of Vix'.

INRAP reports that research concerning the prince’s tomb will continue until 2019, with hopes that more information will come to light.

Top Image: This bronze cauldron is one of the stunning artifacts which have been analyzed from the tomb of a Celtic elite found in Lavau, France. Source: Denis Gliksman, Inrap

By Alicia McDermott

First unearthed in 2015, research on the stunning artifacts found in a rich tomb in Lavau, France are finally coming to light. Scholars have managed to solve the mystery of the tomb’s owner and have provided some other exciting pieces of information on the rich grave goods.

The 2,500-year-old human remains were first discovered in 2015 when archaeologists were exploring a site in preparation for construction of a new commercial center. The tumulus (burial mound) was surrounded by a ditch and palisade. The tomb was said to be larger than the cathedral of nearby Troyes.

The body found in this huge burial mound was accompanied by a chariot, a vase depicting Dionysus, and a beautiful Mediterranean bronze cauldron adorned with castings of the Greek god Achelous and lions’ heads. These elaborate artifacts, along with a stunning gold necklace, bracelets, and finely worked amber beads adorning the skeleton, asserted the person's elite status.

Artifacts in the Celtic elite’s tomb in 2015. ( Denis Gliksman, Inrap )

The French archaeological agency INRAP said the treasures of the tomb are “fitting for one of the highest elite of the end of the first Iron Age,” and told the media it is one of the most remarkable finds of the Celtic Hallstatt period of 800 to 450 BC.

Initially, the archaeologists were uncertain to whom the tomb pertained, first stating that a large knife found alongside the remains suggested it was made for a man, however, the rich golden jewelry opened the possibility that a Celtic princess may have been buried instead.

Now, IB Times reports the recent analysis of the shape of the pelvic bones has solved that mystery – it is today known as the ‘Lavau prince’s’ tomb.

The recent analysis of the shape of the pelvic bones has solved the mystery of the tomb’s owner – it was a Celtic ‘prince.’ (Denis Gliksman, Inrap )

Furthermore, the recent INRAP analysis of the bronze cauldron has shown researchers that its creator(s) had mastered smelting and engraving techniques. By using X-ray radiography, the researchers have found that the prince’s belt is unique and has Celtic motifs formed with silver threads. An examination of a knife sheath showed fine bronze threads. The researchers also saw that a gold torc and several gold bangles have marks where they rubbed against the prince’s skin.

Finally, chemical analysis and 3-D photography show that a large jar that was used to pour wine combines Greek-style ceramic with golden Etruscan and silver Celtic designs. This is an important discovery for the researchers as it provides more evidence of a mix of cultural influences and supports the presence of economic and social interaction present amongst Celtic and Mediterranean people in the 5th century BC. As INRAP previously explained :

"The tomb contains mortuary deposits of sumptuousness worth that of the top Hallstatt elites. The period between the late 6th Century and the beginning of the 5th Century BC was characterized by the economic development of Greek and Etruscan city-states in the West, in particularly Marseilles. Mediterranean traders come into contact with the continental Celtic communities as they searched for slaves, metals and precious goods (including amber)."

Artifacts from the Celtic Lavau Prince’s tomb. ( Denis Gliksman, Inrap )

The prince’s grave is considered one of the most important archaeological discoveries in France in recent decades and it has been compared to the 1953 unearthing of a grave for the 'Lady of Vix'.

INRAP reports that research concerning the prince’s tomb will continue until 2019, with hopes that more information will come to light.

Top Image: This bronze cauldron is one of the stunning artifacts which have been analyzed from the tomb of a Celtic elite found in Lavau, France. Source: Denis Gliksman, Inrap

By Alicia McDermott

Published on June 16, 2017 01:00

June 15, 2017

Burning off the Crust: New Laser Treatment Used to Clean Frescoes in Rome’s Largest 1600-year-old Catacomb Complex

Ancient Origins

Formerly blacked-out frescoes and ancient graffiti in some of Italy’s largest catacombs have been revealed using laser and scanner technology. Restorers, employed by the Vatican, have unveiled frescoes from the time of ancient Rome, depicting some of the most famous Bible stories alongside pagan images - all representing the life to come.

The Catacombs of St. Domitilla house about 150,000 tombs in an underground maze in Rome. The paintings have been covered in grime, dust and smoke since the Roman Empire still ruled much of the world. The remarkable restoration has been carried out by the Pontifical Commission of Sacred Archaeology.

17th Century Discovery

The project has revealed paintings that had been covered for centuries, and also graffiti of the Maltese lawyer, Antonio Bosio, who rediscovered them in the 17th century. Antonio Bosio thought all the tombs were of martyrs, but they only included the tombs of the martyrs Nereus and Achilleus. Bosio wrote his name on some of the paintings in charcoal.

Bosio was called the Christopher Columbus of the Catacombs, says a story about the underground networks on CatholicPhilly.com.

CatholicPhilly.com’s article says of the frescoes:

Pagan symbolism, such as depictions of the four seasons or a peacock representing the afterlife, together with biblical scenes are integrated without contradiction, [Barbara] Mazzei said. The unifying motif is salvation and the deliverance from death as is underlined by the varied depictions of Noah in his ark welcoming back the dove, Abraham’s aborted sacrifice of Isaac, Jonah and the whale, and the multiplication of the fishes and loaves, she said.

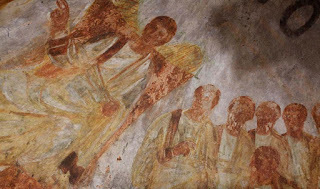

The whale spits out Jonah in a fresco unveiled this week in the huge Roman Christian Catacombs of St. Domitilla. (CNS photo/Carol Glatz)

Lifting The Black Veil

Ms. Mazzei is the director of renovation project. She said the catacombs have 70 burial chambers, called cubicula, but her team restored just 10 of them. She told The Telegraph:

‘When we started work, you couldn’t see anything – it was totally black. Different wavelengths and chromatic selection enabled us to burn away the black disfiguration without touching the colors beneath. Until recently, we weren’t able to carry out this sort of restoration – if we had done it manually we would have risked destroying the frescoes.’

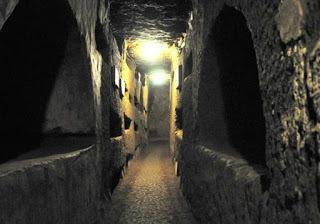

A tunnel showing some of the crypts built into the walls of the Catacombs of St. Domitilla (Dennis Jarvis/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0)

The modern technology used to restore the catacomb’s paintings is better than using conventional methods because they could have been damaged in the process and taken years. The team intends to restore more of the crypts in the underground warrens.

These are Rome’s oldest underground burial sites and were in use from the 2nd century AD until the 9th century. Then they were abandoned. The remains of the 150,000 people are buried in 17 kilometers (10.5 miles) of tunnels or rooms on four levels. The renovations were in the larger rooms, the burial sites for the rich and elite, says an article about the project on IFL Science.

Decorated for Bakers

This renovation work was carried out on the tombs of some of the city’s ancient bakers, says CatholicPhilly. They got rich with a state-supported trade of wheat and bread-baking that benefited people because Rome gave everyone a daily ration.

Bernardino Bertocci attended the unveiling this week to signify that bakers were and still are a vital part of Roman life. Bread, of course, is one of the most important Christian symbols as Jesus broke bread with his disciples during the Last Supper the night before he was beaten, scourged and crucified.

Top image: In this fresco, Jesus is shown seated on a throne with his disciples at hand. The painting is in the Catacombs of St. Domitilla in Rome, which have been newly restored. (CNS photo/Carol Glatz)

By Mark Miller

Published on June 15, 2017 01:30

June 14, 2017

The First Genome Data from Ancient Egyptian Mummies: Ancient Egyptians Were Most Closely Related to Ancient Populations from the Near East

Ancient Origins

An international team of scientists, led by researchers from the University of Tuebingen and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, successfully recovered and analyzed ancient DNA from Egyptian mummies dating from approximately 1400 BCE to 400 CE, including the first genome-wide nuclear data from three individuals, establishing ancient Egyptian mummies as a reliable source for genetic material to study the ancient past. The study, published on Tuesday in Nature Communications, found that modern Egyptians share more ancestry with Sub-Saharan Africans than ancient Egyptians did, whereas ancient Egyptians were found to be most closely related to ancient people from the Near East.

Verena Schuenemann at the Palaeogenetics Laboratory, University of Tuebingen. Credit: Johannes Krause

Methodological Obstacles with Egyptian aDNA

Egypt is a promising location for the study of ancient populations. It has a rich and well-documented history, and its geographic location and many interactions with populations from surrounding areas, in Africa, Asia and Europe, make it a dynamic region. Recent advances in the study of ancient DNA present an intriguing opportunity to test existing understandings of Egyptian history using ancient genetic data.

However, genetic studies of ancient Egyptian mummies are rare due to methodological and contamination issues. Although some of the first extractions of ancient DNA were from mummified remains, scientists have raised doubts as to whether genetic data, especially nuclear genome data, from mummies would be reliable, even if it could be recovered. "The potential preservation of DNA has to be regarded with skepticism," confirms Johannes Krause, Director at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena and senior author of the study. "The hot Egyptian climate, the high humidity levels in many tombs and some of the chemicals used in mummification techniques, contribute to DNA degradation and are thought to make the long-term survival of DNA in Egyptian mummies unlikely." The ability of the authors of this study to extract nuclear DNA from such mummies and to show its reliability using robust authentication methods is a breakthrough that opens the door to further direct study of mummified remains.

Mummified hand (circa 1000 BC) used as a source of ancient DNA (YouTube Screenshot)

The Research

For this study, an international team of researchers from the University of Tuebingen, the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, the University of Cambridge, the Polish Academy of Sciences, and the Berlin Society of Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory, looked at genetic differentiation and population continuity over a 1,300-year timespan, and compared these results to modern populations. The team sampled 151 mummified individuals from the archaeological site of Abusir el-Meleq, along the Nile River in Middle Egypt, from two anthropological collections hosted and curated at the University of Tuebingen and the Felix von Luschan Skull Collection at the Museum of Prehistory of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Stiftung Preussicher Kulturbesitz.

In total, the authors recovered mitochondrial genomes from 90 individuals, and genome-wide datasets from three individuals. They were able to use the data gathered to test previous hypotheses drawn from archaeological and historical data, and from studies of modern DNA. "In particular, we were interested in looking at changes and continuities in the genetic makeup of the ancient inhabitants of Abusir el-Meleq," said Alexander Peltzer, one of the lead authors of the study from the University of Tuebingen. The team wanted to determine if the investigated ancient populations were affected at the genetic level by foreign conquest and domination during the time period under study, and compared these populations to modern Egyptian comparative populations. "We wanted to test if the conquest of Alexander the Great and other foreign powers has left a genetic imprint on the ancient Egyptian population," explains Verena Schuenemann, group leader at the University of Tuebingen and one of the lead authors of this study

Egyptian Mummy in Laboratory (Bigstock)

Close genetic relationship between ancient Egyptians and ancient populations in the Near East The study found that ancient Egyptians were most closely related to ancient populations in the Levant, and were also closely related to Neolithic populations from the Anatolian Peninsula and Europe. "The genetics of the Abusir el-Meleq community did not undergo any major shifts during the 1,300-year timespan we studied, suggesting that the population remained genetically relatively unaffected by foreign conquest and rule," says Wolfgang Haak, group leader at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena. The data shows that modern Egyptians share approximately 8% more ancestry on the nuclear level with Sub-Saharan African populations than with ancient Egyptians. "This suggests that an increase in Sub-Saharan African gene flow into Egypt occurred within the last 1,500 years," explains Stephan Schiffels, group leader at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena. Possible causal factors may have been improved mobility down the Nile River, increased long-distance trade between Sub-Saharan Africa and Egypt, and the trans-Saharan slave trade that began approximately 1,300 years ago.

This study counters prior skepticism about the possibility of recovering reliable ancient DNA from Egyptian mummies. Despite the potential issues of degradation and contamination caused by climate and mummification methods, the authors were able to use high-throughput DNA sequencing and robust authentication methods to ensure the ancient origin and reliability of the data. The study thus shows that Egyptian mummies can be a reliable source of ancient DNA, and can greatly contribute to a more accurate and refined understanding of Egypt's population history.

Top Image: Egyptian sarcophagus containing mummified remains The article ‘ The first genome data from ancient Egyptian mummies: Ancient Egyptians were most closely related to ancient populations from the Near East’ was originally published on Science Daily .

An international team of scientists, led by researchers from the University of Tuebingen and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, successfully recovered and analyzed ancient DNA from Egyptian mummies dating from approximately 1400 BCE to 400 CE, including the first genome-wide nuclear data from three individuals, establishing ancient Egyptian mummies as a reliable source for genetic material to study the ancient past. The study, published on Tuesday in Nature Communications, found that modern Egyptians share more ancestry with Sub-Saharan Africans than ancient Egyptians did, whereas ancient Egyptians were found to be most closely related to ancient people from the Near East.

Verena Schuenemann at the Palaeogenetics Laboratory, University of Tuebingen. Credit: Johannes Krause

Methodological Obstacles with Egyptian aDNA

Egypt is a promising location for the study of ancient populations. It has a rich and well-documented history, and its geographic location and many interactions with populations from surrounding areas, in Africa, Asia and Europe, make it a dynamic region. Recent advances in the study of ancient DNA present an intriguing opportunity to test existing understandings of Egyptian history using ancient genetic data.

However, genetic studies of ancient Egyptian mummies are rare due to methodological and contamination issues. Although some of the first extractions of ancient DNA were from mummified remains, scientists have raised doubts as to whether genetic data, especially nuclear genome data, from mummies would be reliable, even if it could be recovered. "The potential preservation of DNA has to be regarded with skepticism," confirms Johannes Krause, Director at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena and senior author of the study. "The hot Egyptian climate, the high humidity levels in many tombs and some of the chemicals used in mummification techniques, contribute to DNA degradation and are thought to make the long-term survival of DNA in Egyptian mummies unlikely." The ability of the authors of this study to extract nuclear DNA from such mummies and to show its reliability using robust authentication methods is a breakthrough that opens the door to further direct study of mummified remains.

Mummified hand (circa 1000 BC) used as a source of ancient DNA (YouTube Screenshot)

The Research

For this study, an international team of researchers from the University of Tuebingen, the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, the University of Cambridge, the Polish Academy of Sciences, and the Berlin Society of Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory, looked at genetic differentiation and population continuity over a 1,300-year timespan, and compared these results to modern populations. The team sampled 151 mummified individuals from the archaeological site of Abusir el-Meleq, along the Nile River in Middle Egypt, from two anthropological collections hosted and curated at the University of Tuebingen and the Felix von Luschan Skull Collection at the Museum of Prehistory of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Stiftung Preussicher Kulturbesitz.

In total, the authors recovered mitochondrial genomes from 90 individuals, and genome-wide datasets from three individuals. They were able to use the data gathered to test previous hypotheses drawn from archaeological and historical data, and from studies of modern DNA. "In particular, we were interested in looking at changes and continuities in the genetic makeup of the ancient inhabitants of Abusir el-Meleq," said Alexander Peltzer, one of the lead authors of the study from the University of Tuebingen. The team wanted to determine if the investigated ancient populations were affected at the genetic level by foreign conquest and domination during the time period under study, and compared these populations to modern Egyptian comparative populations. "We wanted to test if the conquest of Alexander the Great and other foreign powers has left a genetic imprint on the ancient Egyptian population," explains Verena Schuenemann, group leader at the University of Tuebingen and one of the lead authors of this study

Egyptian Mummy in Laboratory (Bigstock)

Close genetic relationship between ancient Egyptians and ancient populations in the Near East The study found that ancient Egyptians were most closely related to ancient populations in the Levant, and were also closely related to Neolithic populations from the Anatolian Peninsula and Europe. "The genetics of the Abusir el-Meleq community did not undergo any major shifts during the 1,300-year timespan we studied, suggesting that the population remained genetically relatively unaffected by foreign conquest and rule," says Wolfgang Haak, group leader at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena. The data shows that modern Egyptians share approximately 8% more ancestry on the nuclear level with Sub-Saharan African populations than with ancient Egyptians. "This suggests that an increase in Sub-Saharan African gene flow into Egypt occurred within the last 1,500 years," explains Stephan Schiffels, group leader at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena. Possible causal factors may have been improved mobility down the Nile River, increased long-distance trade between Sub-Saharan Africa and Egypt, and the trans-Saharan slave trade that began approximately 1,300 years ago.

This study counters prior skepticism about the possibility of recovering reliable ancient DNA from Egyptian mummies. Despite the potential issues of degradation and contamination caused by climate and mummification methods, the authors were able to use high-throughput DNA sequencing and robust authentication methods to ensure the ancient origin and reliability of the data. The study thus shows that Egyptian mummies can be a reliable source of ancient DNA, and can greatly contribute to a more accurate and refined understanding of Egypt's population history.

Top Image: Egyptian sarcophagus containing mummified remains The article ‘ The first genome data from ancient Egyptian mummies: Ancient Egyptians were most closely related to ancient populations from the Near East’ was originally published on Science Daily .

Published on June 14, 2017 01:30

June 13, 2017

How to throw a medieval feast

History Extra

An elaborate banquet depicted in a 14th-century illuminated manuscript of Froissart's Chronicles. (Getty Images)

Imagine that you are a master chef, working for a celebrity who wants to throw a wedding dinner for their daughter, with 200–300 guests. Next imagine that you have no electricity – no refrigerators, no freezers, no light – and no gas. Your suppliers have to get everything to you fresh, and you don’t want to use salted meat for this important occasion. You are not sure exactly how much of any ingredient you will need until very close to the day. What’s more, the guests may stay on for several days. Among them there will be vegetarians or people needing special diets. To top this all off, the only transport available is horse and cart, so nothing can be brought at the last minute.

Sounds difficult? Working recently on a book on the feasts and festivals of the Middle Ages, I encountered an extraordinary handbook which described exactly how to deal with this situation. Fortunately for us, in 1420, Amadeus VIII, count of Savoy (on the borders of France and Italy) asked his cook - a Master Chiquart - to record his experiences. The house of Savoy had had a reputation for magnificence and stylish living since the mid-14th century, and Chiquart had been employed by Amadeus VIII since the late 1390s. Yet initially, Chiquart was reluctant to set pen to paper and refused to do so. He was a cook, not a learned man who wrote books and nothing like it had ever been done before. However, the duke persisted. Eventually, Chiquart set down what he had learnt in the course of his service, stylishly and with eloquence, in Du fait de cuisine.

Medieval recipe books

By the time Chiquart became the count of Savoy’s master chef, there was a common stock of recipes circulated in manuscript cookery books, and by word of mouth, which were found in princely courts throughout western Europe. What is striking is that we are nonetheless in the presence of a creative chef; Chiquart goes far beyond this basic repertoire. He either elaborates on the standard recipes, or provides new ones that have no parallel elsewhere.

Furthermore, unlike many earlier recipe books that were vague about how to actually cook a particular dish, Chiquart gives the kind of instructions that we find in a modern cookery book. The only difference between his recipes and today’s cookbooks is that Chiquart does not suggest quantities, possibly because they would have varied so hugely between the count’s private dinners and his greatest feasts. Chiquart is instructing his readers in what he has learnt of his art, part of which is to know the amounts to use. One recipe specifies that the cook should put in “just the right amount, so that there is neither too little nor too much”, implying that knowledge only comes with experience, and cannot be written down.

Preparing for a “most honourable feast”

Unlike any earlier writer, Chiquart begins his treatise on cookery with notes on how to organise a “most honourable feast”. These notes at once open a window on the mundane matters on which the success or failure of such an event depended. Cattle, sheep and pigs were to be bought from the butcher, “and for this the butcher will be wise if he is well supplied, so that if it happens that the feast lasts longer than expected, one has promptly what is necessary; and also, if there are extras, do not butcher them so that nothing is wasted.” In other words, the butcher would buy in animals and keep them in his fields until he needed them.

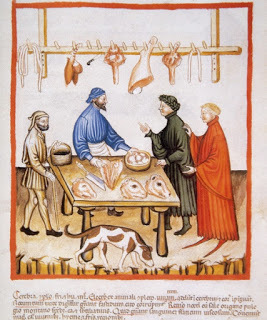

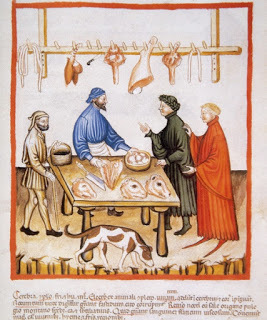

Butchery depicted in a 14th-century handbook of health. (Getty Images)

The quantities were massive: for each day of the feast Chiquart recommended 200 kids and lambs, 100 calves and 2,000 poultry birds; for a major feast lasting a full week, these figures would be multiplied by five, and fish would also be needed for two fast days (Friday and Saturday).

While these numbers may sound huge, comparing Chiquart’s figures against those from English royal feasts in the 13th and 14th centuries shows that they are indeed realistic. At Christmas 1251, Henry III and his guests were served 830 red, fallow and roe deer, 200 wild boar, 1,300 hares, 385 young pigeons (squabs) and 115 cranes; and that was merely the wild game. For the knighting of Edward II in 1306, the cattle required numbered 400 oxen, 800 sheep, 400 pigs and 40 boars.

Preparations had to start early. Chiquart suggests that “subtle, diligent and wise” poulterers should have 40 horsemen at their disposal to get game, river birds, and wild birds, and “whatever they can get”. “They should turn their attention to this two months or six weeks before the feast,” he says, “and they should all have come or sent what they could obtain by three or four days before the said feast so that the said meat can be hung and each dealt with as it ought to be.” The birds must have been held in pens, just as the butchers kept their cattle at pasture. Keeping live wild birds as a kind of larder was quite normal. When Edward III went to war in France in 1346, his huge train of carts included several which were caged to hold poultry.

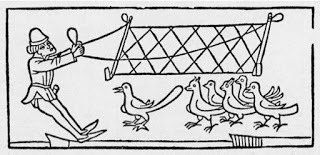

A man trying to catch birds with a net in a 15th-century engraving. (Getty Images)

Spices were a vital ingredient of luxurious dishes in the Middle Ages. Chiquart divides these into “major spices” such as white and Mecca gingers, pepper, cinnamon and grains of paradise (a west African spice somewhere between cardamom and pepper); and “minor spices” such as nutmeg, cloves, colouring agents and decorative items. Also under this heading came practical items, such as wheat starch, as well as almonds, rice and candied fruits, pine nuts and dates. So that the cook could work faster, “one should grind to powder the aforesaid spices and put each separately into large and good leather bags,” Chiquart instructed.

Kitchen equipment is vital for any cook, and Chiquart provides a detailed list with practical comments such as “check the space for making sauces”, and “do not trust wooden spits because they will rot and you could lose all your meat”. Equally there must be enough fuel: “one thousand cartloads of good dry firewood, a great storehouse full of coal. If the feast is held in winter, the kitchen will need 60 torches, 20 pounds of wax candles, and 60 pounds of tallow candles to be used as lights when visiting all the various parts of the kitchen, including the separate building which houses the pastrycooks.”

“In order to better prepare the said feast without reprehension or fault, the house-stewards, the kitchen masters and the master cook should assemble three or four months before the feast to put in order, visit, and find good and sufficient space to do the cooking. This space should be so large and fine that large working sideboards can be set up in such fashion that between the serving sideboards and the others the kitchen masters can go with ease to pass out and receive the dishes.”

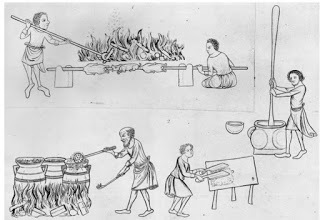

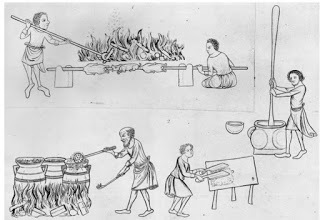

Serfs cooking for their master, depicted in a 14th century manuscript. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Tricky guests

The stewards were evidently in charge of the guest list. They appear in Chiquart’s book to tell the cook how many partridges in tremollete sauce (evidently regarded as a special delicacy) should be put in front of each important guest, ranging downwards from six for a king. These birds were not necessarily for his own personal consumption: a treatise on etiquette explains that a lord’s plate must be piled high so that “you can share your plate courteously to right and to left along the whole high table, so that if you so wish, everyone can have the same food as you”.

There could be complications: “there could be some very high, puissant, noble, venerable and honourable lords and ladies who do not eat meat, for these there must be fish,” records Chiquart. The need to serve fish would also apply if the feast fell on a fast day. Furthermore, some of the guests would have arrived with their own cooks who would prepare certain dishes. Space and provisions would need to be found for these cooks so that they did not hold up the service of the feast as a whole. Another challenge was invalids: “it would be a miracle if there were no ailing or sick people, nor afflicted with any infirmities or maladies”, writes Chiquart. So, having talked to the doctors, he offered 16 recipes for restoratives and special fortifying dishes, including stuffed crayfish and a purée of spinach and parsley.

Chiquart describes a festival to be held over two days. A real event of this kind was held in 1403, when his master the count of Savoy married Mary, daughter of Philip the Bold of Burgundy. Chiquart’s team was required to present a dinner on the first day, as well as dinner and supper on the second day. The wedding celebrations were held on a Friday and Saturday, so meat was not included. These were ‘lean days’, when eating meat was prohibited by the church. Meat was also banned for the whole of Lent and other specific dates in the church calendar.

Colour-coordinated menus

Menus were arranged according to certain basic principles, and the order of service generally conformed to an accepted pattern. At a great feast, the dishes would also be colour-coordinated to demonstrate the cook’s skill. In Chiquart’s first menu, the predominant colours for the first course were gold and green; produced by saffron, egg yolk, green vegetables, herbs and gold serving dishes. The second course of ‘bruets’, or almond milk stews, was white, while the third – lampreys in beef gravy – was red. This was followed by a course of German stews cooked with onions or fish in batter in a green sauce, which had to be carefully judged to come out as a bright and festive green, not a sombre dark green. Decorative pies made up the final course. In another menu, the final course was a spectacular four-coloured blancmange, in which the colours were sharply defined by cooking the four sections separately.

Meat and fish were the most important dishes on the menu. If served roast or boiled, they were always accompanied by a sauce, and Chiquart gives 15 recipes for them. The value placed on sauces is indicated by the name given to a cinnamon sauce in a German cookery book, called a “sauce for lords”. Interestingly, cinnamon seems to have been very rare in Germany, but was used quite widely elsewhere in Europe.

A medieval illustration of a cinnamon seller. (Getty Images)

Soups and stews, which might be based on almond milk or eggs, formed the majority of dishes. Yet they were complex, requiring a careful balance of meats, colours and spices. The list of ingredients for Chiquart’s German stew is as follows: “Capons, pork or lamb, kid or veal; onions; bacon fat; almonds; beef stock; good white wine, verjuice; white ginger, grains of paradise, a little pepper, nutmeg, cloves and mace, saffron for colouring, a lot of sugar; salt.”

All this had to be carefully supervised by the master chef. The kitchen staff on the count of Savoy’s payroll was 20 strong, compared with 34 at the much larger and grander court of the fabulously rich dukes of Burgundy. Chiquart had a kitchen clerk who instructed the cooks as to the number of portions to be prepared: throughout his book, he refers to directing “your companions”, and a high degree of organisation and teamwork was essential. Individual cooks were usually specialists in a particular area with their own assistants, the most skilled being the pastry-maker and sauce cook.

Food as theatre

At this time, the presentation of feasts could be very theatrical. Between courses, there were often dramatic interludes, full of elaborate symbolism, with musicians and members of the court taking part. The most famous feasts at the court of Burgundy involved all kinds of creatures, played by men in pantomime horse fashion:

“My lord the duke was served at table by a two-headed horse ridden by two men sitting back to back, each holding a trumpet and sounding it as loud as he could, and then by a monster, consisting of a man riding on an elephant, with another man, whose feet were hidden, on his shoulders. Next came a white stag ridden by a boy who sang marvellously, while the stag accompanied him with the tenor part."

Part of the responsibility for these interludes fell to the cook’s department: pies containing 24 musicians, statues made of special sugar and pastry, and even elaborate moving devices for which carpenters were brought in.

Considering the immense resources and skills needed to create such an elaborate feast, it is easy to see why Stuart playwright and poet Ben Jonson, two hundred years later, praised Chiquart’s successors in the kitchen to the skies:

“A master cook! why, he is the man of men.

He’s a professor; he designs, he draws,

He paints, he carves, he builds, he fortifies,

Makes citadels of curious fowl and fish.”

Richard Barber is the author of The Prince in Splendour: Court Festivals of Medieval Europe (The Folio Society, 2017)

An elaborate banquet depicted in a 14th-century illuminated manuscript of Froissart's Chronicles. (Getty Images)

Imagine that you are a master chef, working for a celebrity who wants to throw a wedding dinner for their daughter, with 200–300 guests. Next imagine that you have no electricity – no refrigerators, no freezers, no light – and no gas. Your suppliers have to get everything to you fresh, and you don’t want to use salted meat for this important occasion. You are not sure exactly how much of any ingredient you will need until very close to the day. What’s more, the guests may stay on for several days. Among them there will be vegetarians or people needing special diets. To top this all off, the only transport available is horse and cart, so nothing can be brought at the last minute.

Sounds difficult? Working recently on a book on the feasts and festivals of the Middle Ages, I encountered an extraordinary handbook which described exactly how to deal with this situation. Fortunately for us, in 1420, Amadeus VIII, count of Savoy (on the borders of France and Italy) asked his cook - a Master Chiquart - to record his experiences. The house of Savoy had had a reputation for magnificence and stylish living since the mid-14th century, and Chiquart had been employed by Amadeus VIII since the late 1390s. Yet initially, Chiquart was reluctant to set pen to paper and refused to do so. He was a cook, not a learned man who wrote books and nothing like it had ever been done before. However, the duke persisted. Eventually, Chiquart set down what he had learnt in the course of his service, stylishly and with eloquence, in Du fait de cuisine.

Medieval recipe books

By the time Chiquart became the count of Savoy’s master chef, there was a common stock of recipes circulated in manuscript cookery books, and by word of mouth, which were found in princely courts throughout western Europe. What is striking is that we are nonetheless in the presence of a creative chef; Chiquart goes far beyond this basic repertoire. He either elaborates on the standard recipes, or provides new ones that have no parallel elsewhere.

Furthermore, unlike many earlier recipe books that were vague about how to actually cook a particular dish, Chiquart gives the kind of instructions that we find in a modern cookery book. The only difference between his recipes and today’s cookbooks is that Chiquart does not suggest quantities, possibly because they would have varied so hugely between the count’s private dinners and his greatest feasts. Chiquart is instructing his readers in what he has learnt of his art, part of which is to know the amounts to use. One recipe specifies that the cook should put in “just the right amount, so that there is neither too little nor too much”, implying that knowledge only comes with experience, and cannot be written down.

Preparing for a “most honourable feast”

Unlike any earlier writer, Chiquart begins his treatise on cookery with notes on how to organise a “most honourable feast”. These notes at once open a window on the mundane matters on which the success or failure of such an event depended. Cattle, sheep and pigs were to be bought from the butcher, “and for this the butcher will be wise if he is well supplied, so that if it happens that the feast lasts longer than expected, one has promptly what is necessary; and also, if there are extras, do not butcher them so that nothing is wasted.” In other words, the butcher would buy in animals and keep them in his fields until he needed them.

Butchery depicted in a 14th-century handbook of health. (Getty Images)

The quantities were massive: for each day of the feast Chiquart recommended 200 kids and lambs, 100 calves and 2,000 poultry birds; for a major feast lasting a full week, these figures would be multiplied by five, and fish would also be needed for two fast days (Friday and Saturday).

While these numbers may sound huge, comparing Chiquart’s figures against those from English royal feasts in the 13th and 14th centuries shows that they are indeed realistic. At Christmas 1251, Henry III and his guests were served 830 red, fallow and roe deer, 200 wild boar, 1,300 hares, 385 young pigeons (squabs) and 115 cranes; and that was merely the wild game. For the knighting of Edward II in 1306, the cattle required numbered 400 oxen, 800 sheep, 400 pigs and 40 boars.

Preparations had to start early. Chiquart suggests that “subtle, diligent and wise” poulterers should have 40 horsemen at their disposal to get game, river birds, and wild birds, and “whatever they can get”. “They should turn their attention to this two months or six weeks before the feast,” he says, “and they should all have come or sent what they could obtain by three or four days before the said feast so that the said meat can be hung and each dealt with as it ought to be.” The birds must have been held in pens, just as the butchers kept their cattle at pasture. Keeping live wild birds as a kind of larder was quite normal. When Edward III went to war in France in 1346, his huge train of carts included several which were caged to hold poultry.

A man trying to catch birds with a net in a 15th-century engraving. (Getty Images)

Spices were a vital ingredient of luxurious dishes in the Middle Ages. Chiquart divides these into “major spices” such as white and Mecca gingers, pepper, cinnamon and grains of paradise (a west African spice somewhere between cardamom and pepper); and “minor spices” such as nutmeg, cloves, colouring agents and decorative items. Also under this heading came practical items, such as wheat starch, as well as almonds, rice and candied fruits, pine nuts and dates. So that the cook could work faster, “one should grind to powder the aforesaid spices and put each separately into large and good leather bags,” Chiquart instructed.

Kitchen equipment is vital for any cook, and Chiquart provides a detailed list with practical comments such as “check the space for making sauces”, and “do not trust wooden spits because they will rot and you could lose all your meat”. Equally there must be enough fuel: “one thousand cartloads of good dry firewood, a great storehouse full of coal. If the feast is held in winter, the kitchen will need 60 torches, 20 pounds of wax candles, and 60 pounds of tallow candles to be used as lights when visiting all the various parts of the kitchen, including the separate building which houses the pastrycooks.”

“In order to better prepare the said feast without reprehension or fault, the house-stewards, the kitchen masters and the master cook should assemble three or four months before the feast to put in order, visit, and find good and sufficient space to do the cooking. This space should be so large and fine that large working sideboards can be set up in such fashion that between the serving sideboards and the others the kitchen masters can go with ease to pass out and receive the dishes.”

Serfs cooking for their master, depicted in a 14th century manuscript. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Tricky guests

The stewards were evidently in charge of the guest list. They appear in Chiquart’s book to tell the cook how many partridges in tremollete sauce (evidently regarded as a special delicacy) should be put in front of each important guest, ranging downwards from six for a king. These birds were not necessarily for his own personal consumption: a treatise on etiquette explains that a lord’s plate must be piled high so that “you can share your plate courteously to right and to left along the whole high table, so that if you so wish, everyone can have the same food as you”.

There could be complications: “there could be some very high, puissant, noble, venerable and honourable lords and ladies who do not eat meat, for these there must be fish,” records Chiquart. The need to serve fish would also apply if the feast fell on a fast day. Furthermore, some of the guests would have arrived with their own cooks who would prepare certain dishes. Space and provisions would need to be found for these cooks so that they did not hold up the service of the feast as a whole. Another challenge was invalids: “it would be a miracle if there were no ailing or sick people, nor afflicted with any infirmities or maladies”, writes Chiquart. So, having talked to the doctors, he offered 16 recipes for restoratives and special fortifying dishes, including stuffed crayfish and a purée of spinach and parsley.

Chiquart describes a festival to be held over two days. A real event of this kind was held in 1403, when his master the count of Savoy married Mary, daughter of Philip the Bold of Burgundy. Chiquart’s team was required to present a dinner on the first day, as well as dinner and supper on the second day. The wedding celebrations were held on a Friday and Saturday, so meat was not included. These were ‘lean days’, when eating meat was prohibited by the church. Meat was also banned for the whole of Lent and other specific dates in the church calendar.

Colour-coordinated menus

Menus were arranged according to certain basic principles, and the order of service generally conformed to an accepted pattern. At a great feast, the dishes would also be colour-coordinated to demonstrate the cook’s skill. In Chiquart’s first menu, the predominant colours for the first course were gold and green; produced by saffron, egg yolk, green vegetables, herbs and gold serving dishes. The second course of ‘bruets’, or almond milk stews, was white, while the third – lampreys in beef gravy – was red. This was followed by a course of German stews cooked with onions or fish in batter in a green sauce, which had to be carefully judged to come out as a bright and festive green, not a sombre dark green. Decorative pies made up the final course. In another menu, the final course was a spectacular four-coloured blancmange, in which the colours were sharply defined by cooking the four sections separately.

Meat and fish were the most important dishes on the menu. If served roast or boiled, they were always accompanied by a sauce, and Chiquart gives 15 recipes for them. The value placed on sauces is indicated by the name given to a cinnamon sauce in a German cookery book, called a “sauce for lords”. Interestingly, cinnamon seems to have been very rare in Germany, but was used quite widely elsewhere in Europe.

A medieval illustration of a cinnamon seller. (Getty Images)

Soups and stews, which might be based on almond milk or eggs, formed the majority of dishes. Yet they were complex, requiring a careful balance of meats, colours and spices. The list of ingredients for Chiquart’s German stew is as follows: “Capons, pork or lamb, kid or veal; onions; bacon fat; almonds; beef stock; good white wine, verjuice; white ginger, grains of paradise, a little pepper, nutmeg, cloves and mace, saffron for colouring, a lot of sugar; salt.”

All this had to be carefully supervised by the master chef. The kitchen staff on the count of Savoy’s payroll was 20 strong, compared with 34 at the much larger and grander court of the fabulously rich dukes of Burgundy. Chiquart had a kitchen clerk who instructed the cooks as to the number of portions to be prepared: throughout his book, he refers to directing “your companions”, and a high degree of organisation and teamwork was essential. Individual cooks were usually specialists in a particular area with their own assistants, the most skilled being the pastry-maker and sauce cook.

Food as theatre

At this time, the presentation of feasts could be very theatrical. Between courses, there were often dramatic interludes, full of elaborate symbolism, with musicians and members of the court taking part. The most famous feasts at the court of Burgundy involved all kinds of creatures, played by men in pantomime horse fashion:

“My lord the duke was served at table by a two-headed horse ridden by two men sitting back to back, each holding a trumpet and sounding it as loud as he could, and then by a monster, consisting of a man riding on an elephant, with another man, whose feet were hidden, on his shoulders. Next came a white stag ridden by a boy who sang marvellously, while the stag accompanied him with the tenor part."

Part of the responsibility for these interludes fell to the cook’s department: pies containing 24 musicians, statues made of special sugar and pastry, and even elaborate moving devices for which carpenters were brought in.

Considering the immense resources and skills needed to create such an elaborate feast, it is easy to see why Stuart playwright and poet Ben Jonson, two hundred years later, praised Chiquart’s successors in the kitchen to the skies:

“A master cook! why, he is the man of men.

He’s a professor; he designs, he draws,

He paints, he carves, he builds, he fortifies,

Makes citadels of curious fowl and fish.”

Richard Barber is the author of The Prince in Splendour: Court Festivals of Medieval Europe (The Folio Society, 2017)

Published on June 13, 2017 01:00

June 12, 2017

Archaeologists Discover a Stone Age “Cult” Henge Site and 4,000 Year-old Human Remains

Ancient Origins

A team of archaeologists has discovered a Stone Age “cult” henge site and human remains that are estimated to be nearly 4,000 years old. Experts suggest that the human remains, found near Stratford, could belong to some of south Warwickshire’s earliest residents.

Henge was Most Likely Used for Rituals

A group of archaeologists recently discovered a Stone Age “cult” henge site and ancient human remains at a real estate development of residential buildings in Newbold-on-Stour, on fields at Mansell Farm in Stratford. Unlike Stonehenge, the newly found henge is a plain design consisting of a ditch dug into segments and a bank made up of material thrown up from the ditch.

Archaeology Warwickshire Business Manager Stuart Palmer couldn’t hide his excitement about the discovery and stated as Stratford Observer reports , “This exciting discovery is of national importance as it provides tangible evidence for cult or religious belief in late Stone Age Warwickshire. Amazingly it is the second such find by the team. In 2015 a group of four henges was excavated in Bidford although the burials at this site were all cremated. Prior to this there were no known henges in Warwickshire leading some archaeologists to believe that a different kind of cult was prevalent in the region.”

Excavations at Mansell Farm, Newbold-on-Stour (Credit: Archaeology Warwickshire)

Furthermore, archaeology Warwickshire Project Officer Nigel Page, who excavated the site added as Stratford Observer always reports , “Exactly what the henge was used for is not certain, but it is likely to be have been used for rituals, some of which may have been associated with cosmological events over 4000 years ago. Originally it would have been surrounded by a bank which would probably have been on the outside of the ditch. Unlike other types of site the ditch and bank were not for defense, but were intended to close off the interior of the henge and make it an arena for whatever festivals or rituals were taking place within.”

Human Remains Could Belong to the Earliest Residents of South Warwickshire

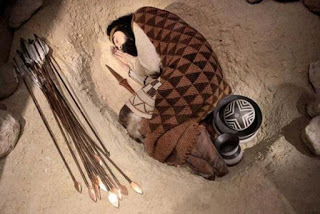

As we already mentioned, the findings also included the buried remains of five individuals which survived as complete skeletons, a very peculiar and unusual phenomenon for the area, archaeologists stated. The individuals were buried very carefully as none of the bodies was found to be positioned on top of another. Experts suggest that the buried individuals could be some of the earliest residents in the area and they estimate that the remains are ancient, somewhere around 4,000 years old. Nigel Page tells Stratford Observer “The rare survival of the skeletons will provide an important opportunity to gain a unique insight into the lives of the people who not only knew the henge and its landscape, but who were probably some of the region’s earliest residents”.

Henge burial detail (Credit: Archaeology Warwickshire)

The three middle burials were facing west, out from the henge, while the two in the two opposite corners were facing east, into the henge. The seemingly calculated positioning of the bodies, indicates that the buried individuals possibly belonged to the same group (most likely were members of the same family), while the people who buried them obviously knew that the grave was owned by the specific group or family.

Further Analysis and Examination Will Reveal More Information

The skeletons have now been unearthed from the site and researchers are getting ready to conduct detailed testing and further analysis, in order to discover more details about who those individuals were.

Nigel Page told Stratford Observer , “The skeletons have been recovered from the site and will undergo scientific analysis to try to answer the many questions that their presence on the site has raised. For example, it is hoped that the sex and age of the people can be established and it may also be possible to determine if there was a family connection between them,” clearly implying that there's more to come from this intriguing discovery.

Top image: Aerial view of circular henge remains and burials (Credit: Archaeology Warwickshire)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on June 12, 2017 01:00

June 11, 2017

Band Posters of the Renaissance: How Medieval Music Fans Showed off Their Taste

Ancient Origins

Tim Shephard / The Conversation

Did you once put a poster of your favorite music artist on your bedroom wall? Are there a few faded gig T-shirts in your bottom drawer? Have you ever bought an LP or CD because of the cover art?

Many music fans enjoy surrounding themselves with images that reflect their musical tastes and experiences – and the meanings and memories they carry. The music enthusiasts of Renaissance Italy were no different.

Serafino sings with lute while under attack by Cupid, title page, 1510 poetry anthology. Fondation Barbier-Mueller pour l'étude de la Poésie Italienne de la Renaissance. (CC BY SA 4.0)

Musical images appeared everywhere in Renaissance Italy, from portraits and altarpieces to dinner plates and saddle steels, from wall paintings and furniture decoration to art prints and book illustration.

Looking at these images can teach us a great deal about what people understood music to be – and what they thought music-making might achieve in their lives.

If you loved music in the age of Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo, the chances are you spent your leisure time playing the lute. And in imitating the most famous singer-songwriter (and inamorato) of the day, Serafino dell’Aquila, young men and women hoped that learning to accompany themselves singing love poems would improve their chances with the opposite sex.

Portrait of an aesthete

When sitting for the portrait painter, many chose the lute as the prop that would capture their character and present them in the best light.

‘Portrait of a Lute Player’ (c. 1600) by Annibale Carracci. (Public Domain)

Hanging your musical portrait in your best room, you’d probably hope that your friends thought you looked a bit like the ancient mythological musician Orpheus. According to the myths, Orpheus was a lover so loyal that he sang his way into hell itself to rescue his wife.

Art prints showing Orpheus sitting under a tree with a lute were all the rage in the Renaissance – you would probably have one sitting about somewhere in your study. In these images, Orpheus is singing a song so powerful that even the animals and birds are moved to tears.

Divine inspiration

Contemporary books on music and poetry explain that this scene of Orpheus moving brute animals to tears represented persuasive eloquence, prized as a leadership quality and a sign of a good education.

‘Orpheus Charming the Animals’ (1613) by Jacob Hoefnagel. (Public Domain)

If you had the money, you’d probably have the walls of your study decorated with pictures of the ancient music-making god Apollo and his Muses.

Inhabitant of the mythological mountain Parnassus, where crystal fountains bubbled forth poetic inspiration, the figure of Apollo allowed you to associate your musical pastime with the immense contemporary fashion for the culture of the ancient world.

You’ll have had him represented with a modern stringed instrument (like yours), probably singing. On your study wall he leads his choir of nine music-making Muses, as they confer their divine inspiration upon your own amateur efforts.

Catholic tastes

Even a disreputable music-lover would attend church for Mass or Vespers at least once a week, so Catholic plainsong was part of the background hum of everyday life. It was widely thought that plainsong imitated the music-making of the angels in heaven. By singing prayers, therefore, you could yourself attain some measure of the divine.

An old panel painting showing the Virgin and Child with music-making angels hangs in your parlor. It would be the focus of prayer and pious contemplation for the whole household, visualizing the divine encounter you would hope to achieve by singing simple sacred songs.

Bernardino Bergognone, Virgin and Child with Two Angels, 1490-95, oil on panel. (The National Gallery, London 2017)

On the other side of the parlor, your young daughter is practicing at a small keyboard instrument, a virginals, very popular in homes of all sizes. The virginals has a lid in the shape of a wonky rectangle which is often painted on the underside, so that you can see the picture when you open the instrument up to play.

Yours shows Apollo again, but this time he’s in a musical contest with a lusty goat-legged satyr. Sitting in judgement is the foolish King Midas (of “Midas touch” fame). The loser risks having his ears turned into those of a donkey, or even being flayed alive. Your daughter concentrates very hard on her scales.

Images such as these were chosen by Renaissance music fans to form a backdrop to their everyday music-making. Like the band posters on a modern bedroom wall, they bear rich witness to musical tastes and experiences, and the meanings people found in them. Delving more deeply into the stories these images tell, music historians are learning to look as well as listen to Renaissance music.

Top Image: Gerard van Honthorst's 1623 painting ‘The Concert.’ Source: Public Domain

The article ‘Band posters of the Renaissance: how medieval music fans showed off their taste’ by Tim Shephard was originally published on The Conversation and has republished under a Creative Commons license

Published on June 11, 2017 01:30

June 10, 2017

Ivar the Boneless: A Viking Warrior That Drew Strength From His Weakness

Ancient Origins

One would expect "boneless" to describe a man without a lick of bravery. Or perhaps a man without a shred of compassion in a heart of ice. Yet in the case of the infamous Ivar the Boneless, son of the renowned Ragnar Lodbrok, "boneless" means precisely what it sounds like: a man lacking sturdy bones, but not power.

Who Was Ivar?

Possibly the son of Ragnar, best remembered for his horrifying death in a pit filled with venomous snakes, Ivar's existence is as much disputed as his father's. Both men possess names which were highly common in the northern countries in the ninth and tenth centuries, and there are records more formal than the Icelandic sagas which describe the deeds of similarly named men. In the case of Ivar, there is more certainty to his life, though the extent to which his accomplishments were his own rather than men of a similar name remains contested.

Ivar is recorded as likely having a condition called osteogenesis imperfecta, indicating that his body can bend beyond what the average human is capable. Rather than enhancing his performance however, such a condition would damage his body over time, gradually weakening him physically. While such a diagnosis was not quite believable in the ninth century, Ivar's "strange state" was unusual enough that its origins were tacked on to his mythological bio: if he was the son of Ragnar, Ivar's bone deficiency is attributed to Ragnar succumbing to his overwhelming lust for Ivar's mother, Aslaug, before the agreed upon time. In other words, it was a curse.

Ivar the Boneless as portrayed in the History Channel Series ‘Vikings’ (History Channel)

The Great Heathen Army Historically, Ivar—despite his boneless moniker—is highly valued for his role as the leader of the Great Heathen Army in 865 AD, discussed in detail in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of the same year. This army—called "heathen" because the ninth century still preceded Christianity in certain northern realms—is credited with a high-scale invasion of the Anglo-Saxons in modern day England. This amalgamation of Danish, Swedish and Norwegian warriors (though these countries were not defined in the ninth century the same way they are today) destroyed their Anglo-Saxon enemies in a short-lived, three-day battle.

History Channel ‘Vikings’ Ivar the Boneless, second left, with his brothers. (History Channel)

According to sources, the Great Heathen Army was headed by Ragnar Lodbrok's three sons, Halfdan Ragnarsson, Ivar the Boneless*, and Ubba. As previously stated, due to the lack of certainty in whether their father Ragnar was the same as the snake-sufferer, it is up for debate precisely why the heathen warriors chose to invade England—that is, if there was a reason beyond the "usual" pirating practices begun when the Vikings invaded Lindisfarne in 793 AD.** If Ivar and his brothers were, in fact, the children of the legendary Ragnar, the significance of this battle increases as the king of Northumbria (one of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms) was directly responsible for Ragnar's death.

Ivar’s Later Identity

As Ivar the Boneless' parentage is under the umbrella of "legendary", there are other theories as to who this possible historical figure may be. One predominate suggestion is that he is Ímar, a Norse-born ninth century leader of the Viking settlement, Dublin.*** Ímar is recorded in the Irish Annals, an overarching term for the various historical documents written in regions that correlate to modern day Ireland. As Ímar's life and battle against the king of Ulster coincide chronologically with that of Ivar the Boneless, it has often been contemplated whether these two men were one and the same, and it is merely the fault of time and medieval biases that they're ancestry is recorded differently. Further, Ívar is no longer mentioned in any historical records following the year 870, not even as a deceased individual. Ímar, on the other hand, resurfaces at this time after an absence from the Irish Annals, and his death year is definitively determined as 873. Thus, if Ivar and Ímar were, in fact, the same individual with alternating names, giving Ímar/Ivar Ragnar Lodbrok as a father would have made his role in various battles and settlements far more pertinent mythologically as well as historically.

Imperfect as Ivar might have been by Viking standards, his "bonelessness" seemingly did little to affect his performance as a warrior and leader. He survives in historical record through the test of time, and his deeds are recorded with the same strong language one would expect from a man of his rank. Whether or not Ivar and Ímar are one, the acts attributed to Ivar directly paint him as a durable, determined Viking warrior, whose eventual defeat of his mythological father's killer is his final defining moment.

*A different historical source, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, dictates a leader named Ingvar, believed also to be the same as Ivar.

**This attack marked the "beginning" of the Viking Age.

***Dublin was initially settled by the Vikings, just like York in northern England.

Top Image: Ivar the Boneless as portrayed in the History Channel Series ‘Vikings’ (History Channel)

By Ryan Stone

One would expect "boneless" to describe a man without a lick of bravery. Or perhaps a man without a shred of compassion in a heart of ice. Yet in the case of the infamous Ivar the Boneless, son of the renowned Ragnar Lodbrok, "boneless" means precisely what it sounds like: a man lacking sturdy bones, but not power.

Who Was Ivar?

Possibly the son of Ragnar, best remembered for his horrifying death in a pit filled with venomous snakes, Ivar's existence is as much disputed as his father's. Both men possess names which were highly common in the northern countries in the ninth and tenth centuries, and there are records more formal than the Icelandic sagas which describe the deeds of similarly named men. In the case of Ivar, there is more certainty to his life, though the extent to which his accomplishments were his own rather than men of a similar name remains contested.

Ivar is recorded as likely having a condition called osteogenesis imperfecta, indicating that his body can bend beyond what the average human is capable. Rather than enhancing his performance however, such a condition would damage his body over time, gradually weakening him physically. While such a diagnosis was not quite believable in the ninth century, Ivar's "strange state" was unusual enough that its origins were tacked on to his mythological bio: if he was the son of Ragnar, Ivar's bone deficiency is attributed to Ragnar succumbing to his overwhelming lust for Ivar's mother, Aslaug, before the agreed upon time. In other words, it was a curse.

Ivar the Boneless as portrayed in the History Channel Series ‘Vikings’ (History Channel)

The Great Heathen Army Historically, Ivar—despite his boneless moniker—is highly valued for his role as the leader of the Great Heathen Army in 865 AD, discussed in detail in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of the same year. This army—called "heathen" because the ninth century still preceded Christianity in certain northern realms—is credited with a high-scale invasion of the Anglo-Saxons in modern day England. This amalgamation of Danish, Swedish and Norwegian warriors (though these countries were not defined in the ninth century the same way they are today) destroyed their Anglo-Saxon enemies in a short-lived, three-day battle.

History Channel ‘Vikings’ Ivar the Boneless, second left, with his brothers. (History Channel)

According to sources, the Great Heathen Army was headed by Ragnar Lodbrok's three sons, Halfdan Ragnarsson, Ivar the Boneless*, and Ubba. As previously stated, due to the lack of certainty in whether their father Ragnar was the same as the snake-sufferer, it is up for debate precisely why the heathen warriors chose to invade England—that is, if there was a reason beyond the "usual" pirating practices begun when the Vikings invaded Lindisfarne in 793 AD.** If Ivar and his brothers were, in fact, the children of the legendary Ragnar, the significance of this battle increases as the king of Northumbria (one of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms) was directly responsible for Ragnar's death.

Ivar’s Later Identity

As Ivar the Boneless' parentage is under the umbrella of "legendary", there are other theories as to who this possible historical figure may be. One predominate suggestion is that he is Ímar, a Norse-born ninth century leader of the Viking settlement, Dublin.*** Ímar is recorded in the Irish Annals, an overarching term for the various historical documents written in regions that correlate to modern day Ireland. As Ímar's life and battle against the king of Ulster coincide chronologically with that of Ivar the Boneless, it has often been contemplated whether these two men were one and the same, and it is merely the fault of time and medieval biases that they're ancestry is recorded differently. Further, Ívar is no longer mentioned in any historical records following the year 870, not even as a deceased individual. Ímar, on the other hand, resurfaces at this time after an absence from the Irish Annals, and his death year is definitively determined as 873. Thus, if Ivar and Ímar were, in fact, the same individual with alternating names, giving Ímar/Ivar Ragnar Lodbrok as a father would have made his role in various battles and settlements far more pertinent mythologically as well as historically.

Imperfect as Ivar might have been by Viking standards, his "bonelessness" seemingly did little to affect his performance as a warrior and leader. He survives in historical record through the test of time, and his deeds are recorded with the same strong language one would expect from a man of his rank. Whether or not Ivar and Ímar are one, the acts attributed to Ivar directly paint him as a durable, determined Viking warrior, whose eventual defeat of his mythological father's killer is his final defining moment.

*A different historical source, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, dictates a leader named Ingvar, believed also to be the same as Ivar.

**This attack marked the "beginning" of the Viking Age.

***Dublin was initially settled by the Vikings, just like York in northern England.

Top Image: Ivar the Boneless as portrayed in the History Channel Series ‘Vikings’ (History Channel)

By Ryan Stone

Published on June 10, 2017 02:00

June 9, 2017

Ancient Scots Hit By Roman Slingshots With the Force of a .44 Magnum

Ancient Origins

Researchers have found 400-some lead slingshot balls at the site of a Roman siege in ancient Scotland and say the balls would have struck the natives with nearly the force of a .44 Magnum handgun—one of the most powerful pistols in the world.

The Battle at Burnswark

The occupation north of Hadrian’s Wall began with the rise to power of Caesar Antoninus Pius. A National Geographic article about new research into the siege and occupation of around 140 AD says he had just been crowned and needed a quick victory.

Researcher John Reid of Trimontium Trust is a co-director of the archaeological studies being done at Burnswark, to the south of Edinburgh. He said the locals had only swords and other simple weapons that were no match for the missiles, which could be shot from 130 yards away with near-pinpoint accuracy.

“We’re fairly sure that the natives on top of the hill weren’t allowed to survive,” Professor Reid told National Geographic.

Even with the success of the attack at Burnswark, the occupation of Scotland was to fail after about 20 years. Despite the Romans’ better weapons, they fought an enemy that would just disappear into the marshes and hills, the article states. The Roman soldiers got bogged down and retreated back to Hadrian’s Wall fewer than 20 years after their successful attack on Burnswark.

What the Battlefield Reveals

Research shows the lead bullets could hit a target smaller than a person from 130 yards (118.9 meters) away and be devastating upon impact. About five years ago Reid and Andrew Nicholson decided to undertake a study of Burnswark to settle a dispute as to whether it was the site of a firing range or a battle. Previous research had shown the site had two Roman camps.

Clay sling bullets from Ardoch, another ancient Scottish battlefield. In the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh. (Ross Cowan / Flickr)

The two men decided to look for ancient Roman ammo. They knew American archaeologists had studied the site of the Battle of the Little Bighorn to find buried bullets and shells and determine how the soldiers and warriors moved around on the battlefield. They wanted to do the same thing at Burnswark. They calibrated metal detectors to find the signature of a Roman sling bullet.

The metal detectorists got 2,700 pings from the hillside and summit of Burnswark. Professor Nicholson documented and mapped them. The National Geographic article states:

Then the team ground-truthed the findings by digging five small trenches. The excavations revealed more than 400 Roman sling bullets right where the metal detectors indicated, as well as two spherical sandstone missiles known as ballista balls. The results suggested that 94 percent of the metal detector hits were in fact Roman bullets.

One of the two ballista balls shot by Roman artillery that researchers discovered at Burnswark (Photo by John Reid)

The researchers found a concentration of bullets across the 500-yard rampart to the south of the hill fort, right above a Roman encampment—just what they expected. They found another concentration of the missiles to the north—possibly blocking any escape route.

The Whistling Missiles

About 10 percent of the bullets had holes drilled into them. When such missiles were tested, they made an eerie whistling sound—an instance, the researchers think, of psychological warfare.

Ancient Origins published an article in 2015 about the messages Romans wrote on their slingshot bullets. They included “Ouch!” “Be Lodged Well” and “Here’s a Sugar Plum For You.”

The use of the sling to launch rocks at the enemy is known from the famous battle between David and Goliath in the 9th century BC. Cast lead bullets from 490 BC were also found at the scene of the Battle of Marathon. The use of slings is known in many parts of the world from ancient times.

The ancient Greeks and Romans produced lead bullets for use in slings in mass quantities, sometimes in molds and sometimes just by digging a figure into sand and pouring molten lead into it. The messages that ancient Romans put on lead sling bullets ranged from naming the leader of the sling unit, the commander of the troops or messages invoking a god or wishing injury upon or insulting the targets, according to the Collector Antiquities blog.

Top image: Some of the lead sling bullets from Burnswark that the ancient Romans used against the people of Scotland; some of the bullets had holes cut into them to cause a terrifying noise. (Photo by John Reid)

By Mark Miller

Researchers have found 400-some lead slingshot balls at the site of a Roman siege in ancient Scotland and say the balls would have struck the natives with nearly the force of a .44 Magnum handgun—one of the most powerful pistols in the world.

The Battle at Burnswark

The occupation north of Hadrian’s Wall began with the rise to power of Caesar Antoninus Pius. A National Geographic article about new research into the siege and occupation of around 140 AD says he had just been crowned and needed a quick victory.

Researcher John Reid of Trimontium Trust is a co-director of the archaeological studies being done at Burnswark, to the south of Edinburgh. He said the locals had only swords and other simple weapons that were no match for the missiles, which could be shot from 130 yards away with near-pinpoint accuracy.

“We’re fairly sure that the natives on top of the hill weren’t allowed to survive,” Professor Reid told National Geographic.

Even with the success of the attack at Burnswark, the occupation of Scotland was to fail after about 20 years. Despite the Romans’ better weapons, they fought an enemy that would just disappear into the marshes and hills, the article states. The Roman soldiers got bogged down and retreated back to Hadrian’s Wall fewer than 20 years after their successful attack on Burnswark.

What the Battlefield Reveals

Research shows the lead bullets could hit a target smaller than a person from 130 yards (118.9 meters) away and be devastating upon impact. About five years ago Reid and Andrew Nicholson decided to undertake a study of Burnswark to settle a dispute as to whether it was the site of a firing range or a battle. Previous research had shown the site had two Roman camps.

Clay sling bullets from Ardoch, another ancient Scottish battlefield. In the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh. (Ross Cowan / Flickr)

The two men decided to look for ancient Roman ammo. They knew American archaeologists had studied the site of the Battle of the Little Bighorn to find buried bullets and shells and determine how the soldiers and warriors moved around on the battlefield. They wanted to do the same thing at Burnswark. They calibrated metal detectors to find the signature of a Roman sling bullet.

The metal detectorists got 2,700 pings from the hillside and summit of Burnswark. Professor Nicholson documented and mapped them. The National Geographic article states:

Then the team ground-truthed the findings by digging five small trenches. The excavations revealed more than 400 Roman sling bullets right where the metal detectors indicated, as well as two spherical sandstone missiles known as ballista balls. The results suggested that 94 percent of the metal detector hits were in fact Roman bullets.

One of the two ballista balls shot by Roman artillery that researchers discovered at Burnswark (Photo by John Reid)