MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 57

May 17, 2017

Sam’s historical recipe corner: Fake fish

History Extra

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates fake fish - a medieval apple pie for Lent.

In the Middle Ages, people were instructed not to eat meat during Lent. Yet the ban didn’t apply to fish – in fact, Dutch gourmets enjoyed serving up ‘fish’ dishes so much that they devised this fish-shaped apple pie. With no animal products, it’s every bit as virtuous as it is delicious.

Ingredients For the dough:

500g flour 125g oil (I used olive oil)

40g ground almonds

300ml water

1tsp salt

Saffron (optional)

Whole/sliced almonds to make scales

For the filling:

3 apples, chopped

90g cane sugar

1tsp ginger

½tsp cinnamon

½tsp saffron

2 slices gingerbread, lightly toasted and crumbled, or 40 ground almonds

Method For the dough:

Mix all the ingredients together, adding more liquid/flour if required, and knead it all until it’s reasonably smooth. Put the dough in the fridge for an hour before you need to use it.

For the filling: Add the ingredients into a blender or mash by hand using a potato masher.

Preheat the oven to 200°C. Divide the pastry in two. Roll out the first part and cut out an oval shape. Place the fish on a baking tray with toasted breadcrumbs sprinkled on the dough. Put the apple filling on to the oval, roll and cut out a second oval and place over the filling, pressing the top layer to the bottom. Cut out an eye hole and a hole near where the tail will go. Add fins, gills, scales. Bake for 45mins.

Difficulty: 3/10

Time: 90 mins

Recipe courtesy of Coquinaria

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates fake fish - a medieval apple pie for Lent.

In the Middle Ages, people were instructed not to eat meat during Lent. Yet the ban didn’t apply to fish – in fact, Dutch gourmets enjoyed serving up ‘fish’ dishes so much that they devised this fish-shaped apple pie. With no animal products, it’s every bit as virtuous as it is delicious.

Ingredients For the dough:

500g flour 125g oil (I used olive oil)

40g ground almonds

300ml water

1tsp salt

Saffron (optional)

Whole/sliced almonds to make scales

For the filling:

3 apples, chopped

90g cane sugar

1tsp ginger

½tsp cinnamon

½tsp saffron

2 slices gingerbread, lightly toasted and crumbled, or 40 ground almonds

Method For the dough:

Mix all the ingredients together, adding more liquid/flour if required, and knead it all until it’s reasonably smooth. Put the dough in the fridge for an hour before you need to use it.

For the filling: Add the ingredients into a blender or mash by hand using a potato masher.

Preheat the oven to 200°C. Divide the pastry in two. Roll out the first part and cut out an oval shape. Place the fish on a baking tray with toasted breadcrumbs sprinkled on the dough. Put the apple filling on to the oval, roll and cut out a second oval and place over the filling, pressing the top layer to the bottom. Cut out an eye hole and a hole near where the tail will go. Add fins, gills, scales. Bake for 45mins.

Difficulty: 3/10

Time: 90 mins

Recipe courtesy of Coquinaria

Published on May 17, 2017 02:00

May 16, 2017

Audio Book Launch - Scribbler Tales Presents: Escape from Berlin - a collection of short stories

Published on May 16, 2017 07:26

What New Archaeological Treasures Have Been Unearthed in the Ancient City of Caesarea?

Ancient Origins

Through the centuries, Caesarea’s populace comprised all the major Abrahamic faiths—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Throw in the original religion at the site, paganism, and you will get an idea of the importance of Caesarea, where major restoration projects are underway.

Archaeologists working in Caesarea announced this week that they recently found an ancient mother-of-pearl tablet incised with a menorah. The menorah tablet dates to the 4th or 5th century AD, experts have estimated. Other recent activity at the site includes preservation of an ancient synagogue and aqueduct. They also found an altar used to worship Caesar Augustus.

Experts say the mother-of-pearl tablet with the menorah found in the ancient harbor town of Caesarea is evidence of a Jewish presence from the 4th or 5th centuries AD. (Clara Amit/ Israel Antiquities Authority )

Roman dictators fancied themselves deities and ordered their worship across the empire. Julius Caesar’s family said they were descended from Roman forefather Aeneas and the goddess of love and war, Venus. Augustus, Julius’ grand-nephew who became emperor, added Divi Filius, “ son of the divine,” to his name. Augustus ruled the Roman Empire from 27 BC to 14 AD.

The Israel Antiquities Authority calls the excavations and conservation projects at Caesarea, underway for many years, some of the largest and most important ever done in Israel.

The ancient synagogue of Caesarea. (Assaf Peretz/ Israel Antiquities Authority )

Phys.org said in a report about the recent finds: “The site, which contains ruins from later periods including the Byzantine, Muslim and Crusader eras, has been the focus of major excavation work over the decades but recent work has revealed new secrets.”

Herod the Great, the king of Judea appointed by Rome, founded Caesarea. Herod has an interesting background. Herod’s father and mother were Arab but practiced Judaism. Herod’s father, Antipater, was a friend of Julius Caesar, who appointed him procurator (governor) of Judea in 47 BC.

Antipater appointed Herod the governor of Galilee, a province of Judea. Mark Antony later appointed him tetrarch of Galilee. When the Parthians invaded Palestine in 40 BC, Herod fled to Rome, where the Senate nominated him king of Judea. They also gave him an army to secure his throne, which he did in 37 BC.

Aerial photo of Caesarea Maritima. (Meronim/ CC BY SA 3.0 )

A book excerpt about Caesarea Maritima on the Cornell University website states :

“Caesarea Maritima, established by Herod the Great on the site of the Hellenistic city of Strato's Tower, has been known continuously from its founding through until the present day, and is the setting for numerous historically significant events and personages. The palace of the city is mentioned in only a few instances, although incidents in lives of the procurators, governors and other officials who dwelt there are more frequently described.”

Harbor Scene with St. Paul's Departure from Caesarea, by Jan Brueghel the Elder ( Public Domain )

An archaeologist who is part of the team working at the site, Peter Gendelman, led Phys.org on a tour of Caesarea and called the preservation work there the most complicated and interesting that he’s done in his 30 years as an archaeologist.

Dr. Gendelman told Phys.org that recent discoveries there are changing researchers’ “understanding of the dynamics of this area.”

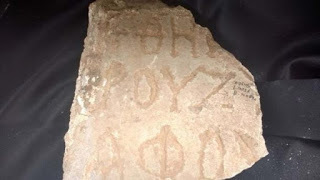

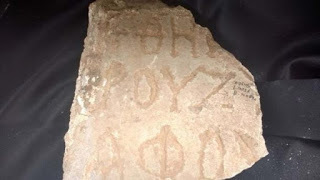

Part of an ancient Greek inscription found during excavations at Caesarea in April 2017. (Ilan Ben Zion/ Times of Israel )

Phys.org also quoted Guy Swersky of the Rothschild Caesarea Foundation as saying, “This was by far the most important port city in this area of the Middle East.”

The Israeli government and the Rothschilds have allotted $27 million (25 million Euros) for the exploration and conservation of the site.

Archaeologists intend to continue excavating and preserving the site and open a visitor’s center that will explain the history of Caesarea.

The site already draws visitors to the ruins of an amphitheater that has been restored somewhat to play host to concerts. Israeli officials hope to draw 3 million visitors annually to the site and its beaches by 2030. Top image: Statue of a ram that was discovered next to the vaults at the front of the temple platform in Caesarea. The town was founded by Herod the Great, king of Judea under the Roman Empire. Source: Caesarea Development Corporation

By Mark Miller

Through the centuries, Caesarea’s populace comprised all the major Abrahamic faiths—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Throw in the original religion at the site, paganism, and you will get an idea of the importance of Caesarea, where major restoration projects are underway.

Archaeologists working in Caesarea announced this week that they recently found an ancient mother-of-pearl tablet incised with a menorah. The menorah tablet dates to the 4th or 5th century AD, experts have estimated. Other recent activity at the site includes preservation of an ancient synagogue and aqueduct. They also found an altar used to worship Caesar Augustus.

Experts say the mother-of-pearl tablet with the menorah found in the ancient harbor town of Caesarea is evidence of a Jewish presence from the 4th or 5th centuries AD. (Clara Amit/ Israel Antiquities Authority )

Roman dictators fancied themselves deities and ordered their worship across the empire. Julius Caesar’s family said they were descended from Roman forefather Aeneas and the goddess of love and war, Venus. Augustus, Julius’ grand-nephew who became emperor, added Divi Filius, “ son of the divine,” to his name. Augustus ruled the Roman Empire from 27 BC to 14 AD.

The Israel Antiquities Authority calls the excavations and conservation projects at Caesarea, underway for many years, some of the largest and most important ever done in Israel.

The ancient synagogue of Caesarea. (Assaf Peretz/ Israel Antiquities Authority )

Phys.org said in a report about the recent finds: “The site, which contains ruins from later periods including the Byzantine, Muslim and Crusader eras, has been the focus of major excavation work over the decades but recent work has revealed new secrets.”

Herod the Great, the king of Judea appointed by Rome, founded Caesarea. Herod has an interesting background. Herod’s father and mother were Arab but practiced Judaism. Herod’s father, Antipater, was a friend of Julius Caesar, who appointed him procurator (governor) of Judea in 47 BC.

Antipater appointed Herod the governor of Galilee, a province of Judea. Mark Antony later appointed him tetrarch of Galilee. When the Parthians invaded Palestine in 40 BC, Herod fled to Rome, where the Senate nominated him king of Judea. They also gave him an army to secure his throne, which he did in 37 BC.

Aerial photo of Caesarea Maritima. (Meronim/ CC BY SA 3.0 )

A book excerpt about Caesarea Maritima on the Cornell University website states :

“Caesarea Maritima, established by Herod the Great on the site of the Hellenistic city of Strato's Tower, has been known continuously from its founding through until the present day, and is the setting for numerous historically significant events and personages. The palace of the city is mentioned in only a few instances, although incidents in lives of the procurators, governors and other officials who dwelt there are more frequently described.”

Harbor Scene with St. Paul's Departure from Caesarea, by Jan Brueghel the Elder ( Public Domain )

An archaeologist who is part of the team working at the site, Peter Gendelman, led Phys.org on a tour of Caesarea and called the preservation work there the most complicated and interesting that he’s done in his 30 years as an archaeologist.

Dr. Gendelman told Phys.org that recent discoveries there are changing researchers’ “understanding of the dynamics of this area.”

Part of an ancient Greek inscription found during excavations at Caesarea in April 2017. (Ilan Ben Zion/ Times of Israel )

Phys.org also quoted Guy Swersky of the Rothschild Caesarea Foundation as saying, “This was by far the most important port city in this area of the Middle East.”

The Israeli government and the Rothschilds have allotted $27 million (25 million Euros) for the exploration and conservation of the site.

Archaeologists intend to continue excavating and preserving the site and open a visitor’s center that will explain the history of Caesarea.

The site already draws visitors to the ruins of an amphitheater that has been restored somewhat to play host to concerts. Israeli officials hope to draw 3 million visitors annually to the site and its beaches by 2030. Top image: Statue of a ram that was discovered next to the vaults at the front of the temple platform in Caesarea. The town was founded by Herod the Great, king of Judea under the Roman Empire. Source: Caesarea Development Corporation

By Mark Miller

Published on May 16, 2017 01:30

May 15, 2017

Joyeuse: The Legendary Sword of Charlemagne

Ancient Origins

The sword of Joyeuse, which today sits in the Louvre Museum, is one of the most famous swords in history. Historical records link the sword to Charlemagne the Great, King of the Franks. If it did indeed belong to the famous king, who reigned some 1,200 years ago, the sword of Joyeuse would have been used in countless coronation ceremonies, and is tied with ancient myth and legend ascribing it with magical powers.

The story begins in the year 802 AD. Legend states that the sword of Joyeuse, meaning “joyful” in French, was forged by the famous blacksmith Galas, and took three years to complete. The sword was described as having magical powers associated with it. It was said to have been so bright that it could outshine the sun and blind its wielder's enemies in battle, and any person who wielded the legendary sword could not be poisoned. The Emperor Charlemagne, coming back from Spain was said to have set up camp in the region and acquired the sword.

The finely crafted Joyeuse sword (Wikimedia Commons)

Charlemagne (742-814 AD), who was also known as Charles the Great, was king of the Franks and Christian emperor of the West. He did much to define the shape and character of medieval Europe and presided over the Carolingian Renaissance. After the fall of the Roman Empire, he was the first to reunite Western Europe. He ruled a vast kingdom that encompassed what is now France, Germany, Italy, Austria, and the Low Countries, consolidating Christianity through his vast empire through forced conversions. His military ‘accomplishments’ frequently involved extreme brutality, such as the beheading of more than 2,500 Frankish and Saxon village chiefs.

The coronation of Charlemagne by Raphael, c 1515, (Wikimedia Commons)

The 11th century Song of Roland, an epic poem based on the Battle of Roncevaux in 778, describes Charlemagne riding into battle with Joyeuse by his side:

[Charlemagne] was wearing his fine white coat of mail and his helmet with gold-studded stones; by his side hung Joyeuse, and never was there a sword to match it; its color changed thirty times a day.

One day, during battle, Charlemagne allegedly lost Joyeuse, and promised a reward for anyone who could find it. After several attempts, one of his soldiers brought it to him and Charlemagne kept his promise by saying, “Here will be built an estate of which you will be the lord and master, and your descendants will take the name of my wonderful sword: Joyeuse.” Charlemagne is said to have planted his sword in the ground to mark the point where the town would be built. According to the story, this is the origin of the French town of Joyeuse in Ardèche, which was founded on that spot and named in honor of the sword.

The town of Joyeuse in Ardèche, France (Wikimedia Commons)

There are no historical records to say what happened to the sword Joyeuse after the death of Charlemagne. However, in 1270AD, a sword identified as Joyeuse was used at the coronation ceremony of French King Philip the Bold, which was held in Reims Cathedral, France, and many kings after that. The sword was kept in the nearby monastery in Saint-Denis, a burial place for French kings, where it remained under the protection of the monks until at least 1505.

Joyeuse was moved to the Louvre on December 5, 1793 following the French Revolution. It was last used by a French king in 1824 with the crowning of Charles X and is the only known sword to have served as the coronation sword of the Kings of France.

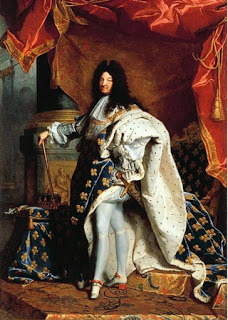

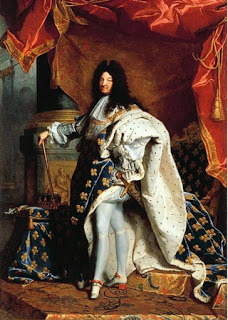

King Louis XIV with Joyeuse by Hyacinthe Rigaud, 1701. (Wikimedia Commons)

Today, the Joyeuse is preserved as a composite of various parts added over the centuries of use as coronation sword. The blade is characteristic of the Oakeshott Style XII, which features a broad, flat, evenly tapering blade. The pommel (top fitting) of the sword dates from the 10th and 11th centuries, the cross to the second half of the 12th century, and the grip to the 13th century.

The grip once featured a fleur-de-lis, but was removed for the coronation of Napoleon I in 1804. Two dragons form the cross section and their eyes are of lapis lazuli. The scabbard, also modified, has a velvet sheath embroidered with fleur-de-lis and was added for the coronation of Charles X in 1824. Both sides of the pommel are decorated with a repoussé motif representing birds affrontee, similar to Scandinavian ornaments of the 10th and 11th centuries. The two cross-guards, in the form of stylized winged dragon figures, can be dated to the 12th century. The gold spindle, covered with a diamond net pattern, is believed to be from the 13th or 14th century.

The Joyeuse sword in the Louvre Museum (Wikimedia Commons)

The sword of Joyeuse stands today as a testament to the exceptionally crafted regalia used throughout the centuries. Appearing in the coronations of the Kings of France over the course of hundreds of years has only reinforced its legacy as a symbol of power and authority. It is visually stunning to behold and today, Joyeuse ranks among the most reproduced of any historical sword.

Featured image: Joyeuse, the Sword of Charlemagne (Wikimedia Commons)

References

O'Neil, Tim. The Legends of Joyeuse. Accessed May 6, 2015. http://www.quora.com/Why-is-Charlemag....

Hellqvist, Bjorn. "The Sword of Charlemagne -- MyArmoury.com." The Sword of Charlemagne -- MyArmoury.com. Accessed May 6, 2015. http://www.myarmoury.com/feature_char....

"4 / Ceremony and Society." Art Through Time: A Global View. Accessed May 6, 2015. https://www.learner.org/courses/globa....

Gaudreau, HJ. "The Sword of Charlemagne." BOOKS BY HJ GAUDREAU. July 6, 2013. Accessed May 6, 2015. http://www.hjgaudreau.com/betrayal/th....

Barclay, Shelly. "The History of Charlemagne's Sword - Joyeuse." Examiner.com. May 28, 2013. Accessed May 6, 2015. http://www.examiner.com/article/the-h....

By Bryan Hilliard

The sword of Joyeuse, which today sits in the Louvre Museum, is one of the most famous swords in history. Historical records link the sword to Charlemagne the Great, King of the Franks. If it did indeed belong to the famous king, who reigned some 1,200 years ago, the sword of Joyeuse would have been used in countless coronation ceremonies, and is tied with ancient myth and legend ascribing it with magical powers.

The story begins in the year 802 AD. Legend states that the sword of Joyeuse, meaning “joyful” in French, was forged by the famous blacksmith Galas, and took three years to complete. The sword was described as having magical powers associated with it. It was said to have been so bright that it could outshine the sun and blind its wielder's enemies in battle, and any person who wielded the legendary sword could not be poisoned. The Emperor Charlemagne, coming back from Spain was said to have set up camp in the region and acquired the sword.

The finely crafted Joyeuse sword (Wikimedia Commons)

Charlemagne (742-814 AD), who was also known as Charles the Great, was king of the Franks and Christian emperor of the West. He did much to define the shape and character of medieval Europe and presided over the Carolingian Renaissance. After the fall of the Roman Empire, he was the first to reunite Western Europe. He ruled a vast kingdom that encompassed what is now France, Germany, Italy, Austria, and the Low Countries, consolidating Christianity through his vast empire through forced conversions. His military ‘accomplishments’ frequently involved extreme brutality, such as the beheading of more than 2,500 Frankish and Saxon village chiefs.

The coronation of Charlemagne by Raphael, c 1515, (Wikimedia Commons)

The 11th century Song of Roland, an epic poem based on the Battle of Roncevaux in 778, describes Charlemagne riding into battle with Joyeuse by his side:

[Charlemagne] was wearing his fine white coat of mail and his helmet with gold-studded stones; by his side hung Joyeuse, and never was there a sword to match it; its color changed thirty times a day.

One day, during battle, Charlemagne allegedly lost Joyeuse, and promised a reward for anyone who could find it. After several attempts, one of his soldiers brought it to him and Charlemagne kept his promise by saying, “Here will be built an estate of which you will be the lord and master, and your descendants will take the name of my wonderful sword: Joyeuse.” Charlemagne is said to have planted his sword in the ground to mark the point where the town would be built. According to the story, this is the origin of the French town of Joyeuse in Ardèche, which was founded on that spot and named in honor of the sword.

The town of Joyeuse in Ardèche, France (Wikimedia Commons)

There are no historical records to say what happened to the sword Joyeuse after the death of Charlemagne. However, in 1270AD, a sword identified as Joyeuse was used at the coronation ceremony of French King Philip the Bold, which was held in Reims Cathedral, France, and many kings after that. The sword was kept in the nearby monastery in Saint-Denis, a burial place for French kings, where it remained under the protection of the monks until at least 1505.

Joyeuse was moved to the Louvre on December 5, 1793 following the French Revolution. It was last used by a French king in 1824 with the crowning of Charles X and is the only known sword to have served as the coronation sword of the Kings of France.

King Louis XIV with Joyeuse by Hyacinthe Rigaud, 1701. (Wikimedia Commons)

Today, the Joyeuse is preserved as a composite of various parts added over the centuries of use as coronation sword. The blade is characteristic of the Oakeshott Style XII, which features a broad, flat, evenly tapering blade. The pommel (top fitting) of the sword dates from the 10th and 11th centuries, the cross to the second half of the 12th century, and the grip to the 13th century.

The grip once featured a fleur-de-lis, but was removed for the coronation of Napoleon I in 1804. Two dragons form the cross section and their eyes are of lapis lazuli. The scabbard, also modified, has a velvet sheath embroidered with fleur-de-lis and was added for the coronation of Charles X in 1824. Both sides of the pommel are decorated with a repoussé motif representing birds affrontee, similar to Scandinavian ornaments of the 10th and 11th centuries. The two cross-guards, in the form of stylized winged dragon figures, can be dated to the 12th century. The gold spindle, covered with a diamond net pattern, is believed to be from the 13th or 14th century.

The Joyeuse sword in the Louvre Museum (Wikimedia Commons)

The sword of Joyeuse stands today as a testament to the exceptionally crafted regalia used throughout the centuries. Appearing in the coronations of the Kings of France over the course of hundreds of years has only reinforced its legacy as a symbol of power and authority. It is visually stunning to behold and today, Joyeuse ranks among the most reproduced of any historical sword.

Featured image: Joyeuse, the Sword of Charlemagne (Wikimedia Commons)

References

O'Neil, Tim. The Legends of Joyeuse. Accessed May 6, 2015. http://www.quora.com/Why-is-Charlemag....

Hellqvist, Bjorn. "The Sword of Charlemagne -- MyArmoury.com." The Sword of Charlemagne -- MyArmoury.com. Accessed May 6, 2015. http://www.myarmoury.com/feature_char....

"4 / Ceremony and Society." Art Through Time: A Global View. Accessed May 6, 2015. https://www.learner.org/courses/globa....

Gaudreau, HJ. "The Sword of Charlemagne." BOOKS BY HJ GAUDREAU. July 6, 2013. Accessed May 6, 2015. http://www.hjgaudreau.com/betrayal/th....

Barclay, Shelly. "The History of Charlemagne's Sword - Joyeuse." Examiner.com. May 28, 2013. Accessed May 6, 2015. http://www.examiner.com/article/the-h....

By Bryan Hilliard

Published on May 15, 2017 02:00

May 14, 2017

Why Would You Cremate and Bury Your Home? A Bizarre Viking Ritual Explained

Ancient Origins

The Vikings had a very bizarre tradition that might be totally unique: they buried their own homes. From the Bronze Age until the Viking Age, historians have noted that burial mounds were placed on top of the remains of Viking longhouses. The internal posts that served as roof-supporting beams were usually taken off before the house was set on fire and once the house had burned to the ground, one or more burial mounds were positioned on top of its remnants.

Vikings Burnt and Buried Their Own Houses

As Heritage Daily reports, Marianne Hem Eriksen, a postdoc at the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History at the University of Oslo has investigated these uncommon “deaths” and burials of Scandinavian longhouses for quite some time now. She says, “I studied seven different house burials from the Iron Age in Scandinavia, in five different locations: Högom in Sweden; Ullandhaug in Rogaland; Brista in Uppland, Sweden; Jarlsberg in Vestfold; and Engelaug in Hedmark.”

Eriksen believes that the burial mounds were not always tied with human death, but instead they could possibly mark the cremation and burial of a house within Viking society. She explained to Heritage Daily, “In some cases we have been unable to find human remains, even in places where we could expect such remains to have been preserved. Nevertheless, archaeologists have more or less implicitly assumed that somewhere or other, there must be a deceased individual.

Artist’s interpretation of a ‘Viking Village.’ (Lukasz Wiktorzak/ArtStation)

Living in a Typical Viking Longhouse

As Robin Whitlock suggests in a previous Ancient Origins article, a typical longhouse was a long and probably very chaotic structure, plagued by noise and dirt. This was primarily because a number of families tended to live in the same house along with their animals (that were kept at one end of the structure.) This area would also be where the crops were stored and it would have been separated into stalls for animals and crops. The fire was a source of heat and light, but there was no chimney and that meant the longhouse would have been very smoky. Sometimes, additional lighting was provided in the form of stone lamps with fish liver oil or whale oil as the fuel. Seating was either in the form of wooden benches along the walls or an available spot on the floor.

The walls of a longhouse were commonly made from a structure of wooden poles with wattle and daub infilling. In Denmark, some longhouses had forges inside them, although more commonly the forge was housed in a separate building. The size of the longhouse depended on the wealth of the owner and in some areas of Denmark royal longhouses were located in settlements within round earthen embankments consisting of four longhouses. Each longhouse accommodated the crew of a ship and their families. The roof was made of thatch or wooden shingles.

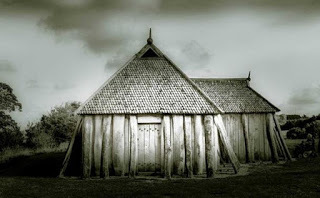

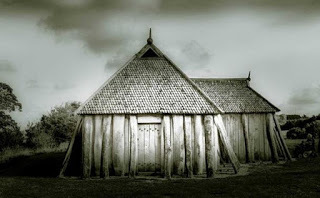

Reconstruction of a Viking house from the ring castle Fyrkat near Hobro, Denmark. (Malene Thyssen/CC BY SA 3.0)

Can a House Die?

The question popping up from such practices is simple: Can a house (or any object for that matter) die? Marianne Hem Eriksen had to dig deep into anthropology’s mysteries to find more sources about people’s attachment to their houses in various cultures. She told Heritage Daily,

“To people in Madagascar, a house has its own life cycle. It is born, lives, grows old and dies. The Batammaliba people of West Africa perform rituals during the construction of houses, the same rites of passage that they perform for newborn babies, adolescents and adults. When the house is completed, they perform a ritual where they ‘kill’ the house. The house has been alive during the building process, and must be killed to make it habitable for people. Many cultures believe that the house is metaphorically linked to the human body.”

The Link Between Human Bodies and Objects in Viking Culture

After years of research and study on the topic, Eriksen is pretty convinced that the Vikings saw a link between the human body and the house they were living in during their lifetime. As she told Heritage Daily:

“Many of the Norse words that are related to houses are derived from the human body. The word window comes from wind and eye and refers to openings in the walls where the wind comes in. The word gable, i.e. the top of the end wall of the house, means head or skull. This connection between bodies and houses may have led them to think that a house has some kind of essence, some kind of soul.”

‘Viking Long house door. Norway, Epcot Center.’ (One Lucky Guy/CC BY NC SA 2.0)

This possibly explains why Norse people during that period would often give their house a proper funeral when it had completed its circle of life. As Eriksen explained:

“By burning down the house they may have had a wish to cremate it, to liberate the life force of the house. If houses and people could be part of a network that had ‘agency’ – vitality and personality – this could at least be part of the explanation for the longevity of longhouses in Scandinavia.”

Eriksen is currently continuing her study on the topic and has published an article on the same in the European Journal of Archaeology.

Viking Longhouse – Reconstruction. (Eric Gross/CC BY 2.0)

Top Image: ‘Light and Structure’ - Reconstruction of Viking Longhouse: Central Jutland, Denmark. Source: Eric Gross/CC BY 2.0

By Theodoros Karasavvas

The Vikings had a very bizarre tradition that might be totally unique: they buried their own homes. From the Bronze Age until the Viking Age, historians have noted that burial mounds were placed on top of the remains of Viking longhouses. The internal posts that served as roof-supporting beams were usually taken off before the house was set on fire and once the house had burned to the ground, one or more burial mounds were positioned on top of its remnants.

Vikings Burnt and Buried Their Own Houses

As Heritage Daily reports, Marianne Hem Eriksen, a postdoc at the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History at the University of Oslo has investigated these uncommon “deaths” and burials of Scandinavian longhouses for quite some time now. She says, “I studied seven different house burials from the Iron Age in Scandinavia, in five different locations: Högom in Sweden; Ullandhaug in Rogaland; Brista in Uppland, Sweden; Jarlsberg in Vestfold; and Engelaug in Hedmark.”

Eriksen believes that the burial mounds were not always tied with human death, but instead they could possibly mark the cremation and burial of a house within Viking society. She explained to Heritage Daily, “In some cases we have been unable to find human remains, even in places where we could expect such remains to have been preserved. Nevertheless, archaeologists have more or less implicitly assumed that somewhere or other, there must be a deceased individual.

Artist’s interpretation of a ‘Viking Village.’ (Lukasz Wiktorzak/ArtStation)

Living in a Typical Viking Longhouse

As Robin Whitlock suggests in a previous Ancient Origins article, a typical longhouse was a long and probably very chaotic structure, plagued by noise and dirt. This was primarily because a number of families tended to live in the same house along with their animals (that were kept at one end of the structure.) This area would also be where the crops were stored and it would have been separated into stalls for animals and crops. The fire was a source of heat and light, but there was no chimney and that meant the longhouse would have been very smoky. Sometimes, additional lighting was provided in the form of stone lamps with fish liver oil or whale oil as the fuel. Seating was either in the form of wooden benches along the walls or an available spot on the floor.

The walls of a longhouse were commonly made from a structure of wooden poles with wattle and daub infilling. In Denmark, some longhouses had forges inside them, although more commonly the forge was housed in a separate building. The size of the longhouse depended on the wealth of the owner and in some areas of Denmark royal longhouses were located in settlements within round earthen embankments consisting of four longhouses. Each longhouse accommodated the crew of a ship and their families. The roof was made of thatch or wooden shingles.

Reconstruction of a Viking house from the ring castle Fyrkat near Hobro, Denmark. (Malene Thyssen/CC BY SA 3.0)

Can a House Die?

The question popping up from such practices is simple: Can a house (or any object for that matter) die? Marianne Hem Eriksen had to dig deep into anthropology’s mysteries to find more sources about people’s attachment to their houses in various cultures. She told Heritage Daily,

“To people in Madagascar, a house has its own life cycle. It is born, lives, grows old and dies. The Batammaliba people of West Africa perform rituals during the construction of houses, the same rites of passage that they perform for newborn babies, adolescents and adults. When the house is completed, they perform a ritual where they ‘kill’ the house. The house has been alive during the building process, and must be killed to make it habitable for people. Many cultures believe that the house is metaphorically linked to the human body.”

The Link Between Human Bodies and Objects in Viking Culture

After years of research and study on the topic, Eriksen is pretty convinced that the Vikings saw a link between the human body and the house they were living in during their lifetime. As she told Heritage Daily:

“Many of the Norse words that are related to houses are derived from the human body. The word window comes from wind and eye and refers to openings in the walls where the wind comes in. The word gable, i.e. the top of the end wall of the house, means head or skull. This connection between bodies and houses may have led them to think that a house has some kind of essence, some kind of soul.”

‘Viking Long house door. Norway, Epcot Center.’ (One Lucky Guy/CC BY NC SA 2.0)

This possibly explains why Norse people during that period would often give their house a proper funeral when it had completed its circle of life. As Eriksen explained:

“By burning down the house they may have had a wish to cremate it, to liberate the life force of the house. If houses and people could be part of a network that had ‘agency’ – vitality and personality – this could at least be part of the explanation for the longevity of longhouses in Scandinavia.”

Eriksen is currently continuing her study on the topic and has published an article on the same in the European Journal of Archaeology.

Viking Longhouse – Reconstruction. (Eric Gross/CC BY 2.0)

Top Image: ‘Light and Structure’ - Reconstruction of Viking Longhouse: Central Jutland, Denmark. Source: Eric Gross/CC BY 2.0

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on May 14, 2017 02:00

May 13, 2017

One of Jamestown’s Greatest Mysteries – Who Lies Beneath the Knight’s Tombstone?

Ancient Origins

A team of archaeologists at Historic Jamestown is attempting to solve one of the biggest mysteries of the first English settlements in America: a knight’s gravestone that has been embedded into the floor of a church for almost four hundred years. According to the researchers, the two most likely owners of the grave are colonial Governors Sir George Yeardley and Thomas West.

The tombstone, which is carved with an image of a knight and was once adorned with monumental brasses, is located in an old church in Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent English settlement in the Americas.

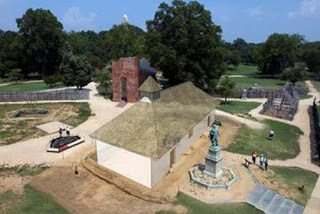

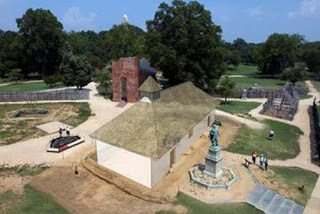

A reconstruction of what Jamestown may have originally looked like (public domain)

Preservation Virginia Team Has Hard Time to Conduct Proper Research Preservation

Virginia Senior Staff Archaeologist Michael Lavin was very honest about the difficulties of this research and all the mysteries the tombstone posed for his team. “This is kind of out of the realm of what we in the conservation department are doing,” he told WY Daily. And went on to explain how his team lacked the required prowess to conduct a proper scientific research in this case, “It is an artifact, but it is more of a monument. One of the most important things for us is knowing our limitations. We’re archaeological conservators. It’s a completely different field than monuments conservation. The things we hold are never this heavy.”

Who’s the Owner of the Body Beneath?

So, the main question and undoubtedly the greatest mystery in this research revolves around the identity of the body beneath the tombstone. Hayden Bassett, Assistant Curator with Preservation Virginia, claims that by the process of elimination, the two most possible candidates are colonial Governors Sir George Yeardley and Thomas West, The Lord de la Warre. The team focused on the study of the family records of the two men in order to solve the mystery, “When you’re studying mortuary practices, when you’re studying monuments, you never want to go to the records of the person who died, you want to go to the records of their offspring, of their family members who are still living. They’re the people who are largely going to be dealing with the logistics of getting a massive stone over here,” Basset told WY Daily.

After Preservation Virginia conducted detailed research and went through the journals of both men’s extended families, Basset speculates that they may have found mentions of the stone by Yeardley’s step-grandson Adam Thorowgood II. “What they mention is that they would like to have a black marble tomb with the crest of Sir George Yeardley and the same inscription as upon the broken tomb. We believe that might reference this stone,” Basset tells WY Daily and suggests that if a crest were preserved on the tombstone then archaeologists wouldn’t have any difficulties identifying the grave’s owner.

Mary Anna Hartley, Preservation Virginia Field Supervisor, appears to share the same views with Basset, “Not having the monumental brasses is a real issue,” she told WY Daily, but she believes that the owner is no other than Yeardley and soon they will have more evidence in their hands to prove it, “I’m very optimistic one way or the other who it belonged to, because of how well intact the church has been. We have a real chance here to solve one of our Jamestown mysteries.”

Sir George Yeardley

Sir George Yeardley was knighted by King James I for his role as Governor of the British Colony of Virginia and Jamestown. He was a survivor of the Virginia Company of London's ill-fated Third Supply Mission, whose flagship, the Sea Venture, was shipwrecked on Bermuda for 10 months in 1609-10. He arrived in Jamestown in May, 1610, and in 1616 came to an agreement with the Chickahominy Indians that secured food and peace for two years.

Far from a knight in shining armor, Yeardley was one of the first Virginians to own African slaves, and was also involved in the exploitation of gold and silver mines. His preoccupation with tobacco interests, to the detriment of the colony’s defences, contributed to the decision for Native Americans to attack in 1622. Yeardley responded by demanding the seizure of their corn, then sold it to starving colonists, pocketing the money for himself.

Is George Yeardley the owner of the mysterious knight’s tomb?

Currently and as conservation of the tombstone continues, Preservation Virginia is determining how to display the tombstone and interpret Yeardley’s legacy to the public.

Top image: The Knight’s Tombstone in Jamestown. (Andrew Harris/WYDaily)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A team of archaeologists at Historic Jamestown is attempting to solve one of the biggest mysteries of the first English settlements in America: a knight’s gravestone that has been embedded into the floor of a church for almost four hundred years. According to the researchers, the two most likely owners of the grave are colonial Governors Sir George Yeardley and Thomas West.

The tombstone, which is carved with an image of a knight and was once adorned with monumental brasses, is located in an old church in Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent English settlement in the Americas.

A reconstruction of what Jamestown may have originally looked like (public domain)

Preservation Virginia Team Has Hard Time to Conduct Proper Research Preservation

Virginia Senior Staff Archaeologist Michael Lavin was very honest about the difficulties of this research and all the mysteries the tombstone posed for his team. “This is kind of out of the realm of what we in the conservation department are doing,” he told WY Daily. And went on to explain how his team lacked the required prowess to conduct a proper scientific research in this case, “It is an artifact, but it is more of a monument. One of the most important things for us is knowing our limitations. We’re archaeological conservators. It’s a completely different field than monuments conservation. The things we hold are never this heavy.”

Who’s the Owner of the Body Beneath?

So, the main question and undoubtedly the greatest mystery in this research revolves around the identity of the body beneath the tombstone. Hayden Bassett, Assistant Curator with Preservation Virginia, claims that by the process of elimination, the two most possible candidates are colonial Governors Sir George Yeardley and Thomas West, The Lord de la Warre. The team focused on the study of the family records of the two men in order to solve the mystery, “When you’re studying mortuary practices, when you’re studying monuments, you never want to go to the records of the person who died, you want to go to the records of their offspring, of their family members who are still living. They’re the people who are largely going to be dealing with the logistics of getting a massive stone over here,” Basset told WY Daily.

After Preservation Virginia conducted detailed research and went through the journals of both men’s extended families, Basset speculates that they may have found mentions of the stone by Yeardley’s step-grandson Adam Thorowgood II. “What they mention is that they would like to have a black marble tomb with the crest of Sir George Yeardley and the same inscription as upon the broken tomb. We believe that might reference this stone,” Basset tells WY Daily and suggests that if a crest were preserved on the tombstone then archaeologists wouldn’t have any difficulties identifying the grave’s owner.

Mary Anna Hartley, Preservation Virginia Field Supervisor, appears to share the same views with Basset, “Not having the monumental brasses is a real issue,” she told WY Daily, but she believes that the owner is no other than Yeardley and soon they will have more evidence in their hands to prove it, “I’m very optimistic one way or the other who it belonged to, because of how well intact the church has been. We have a real chance here to solve one of our Jamestown mysteries.”

Sir George Yeardley

Sir George Yeardley was knighted by King James I for his role as Governor of the British Colony of Virginia and Jamestown. He was a survivor of the Virginia Company of London's ill-fated Third Supply Mission, whose flagship, the Sea Venture, was shipwrecked on Bermuda for 10 months in 1609-10. He arrived in Jamestown in May, 1610, and in 1616 came to an agreement with the Chickahominy Indians that secured food and peace for two years.

Far from a knight in shining armor, Yeardley was one of the first Virginians to own African slaves, and was also involved in the exploitation of gold and silver mines. His preoccupation with tobacco interests, to the detriment of the colony’s defences, contributed to the decision for Native Americans to attack in 1622. Yeardley responded by demanding the seizure of their corn, then sold it to starving colonists, pocketing the money for himself.

Is George Yeardley the owner of the mysterious knight’s tomb?

Currently and as conservation of the tombstone continues, Preservation Virginia is determining how to display the tombstone and interpret Yeardley’s legacy to the public.

Top image: The Knight’s Tombstone in Jamestown. (Andrew Harris/WYDaily)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on May 13, 2017 01:30

May 12, 2017

Can Researchers Crack da Vinci’s DNA Code? Recently Discovered Relics Attributed to the Legendary Renaissance Man May Help

Ancient Origins

A team of Italian researchers claim that they have discovered two relics belonging to Leonardo da Vinci, which could them help in tracing the DNA of the legendary polymath whose work epitomized the Renaissance.

A Discovery of Immense Historical Importance? Could These be Da Vinci’s Relics? The peculiar relics were spotted during a long-term genealogical study of da Vinci’s family. “I can’t yet disclose the nature of these relics. I can only say that both are historically associated with Leonardo da Vinci. One is an object, the other is organic material,” Alessandro Vezzosi, director of the Museo Ideale in Vinci, told Seeker. The significance of such a discovery – if the relics are authentic– would be of immense historical value, since there are no known traces left of the Italian genius.

According to the “mainstream” version of history, the remains of Leonardo da Vinci, who died in 1519 in France, were scattered before the 19th century. However, in 1863 a corpse and large skull were discovered at the church of Saint-Florentin, where da Vinci was initially buried. Unfortunately, the place was pillaged during religious conflicts back in the 16th century and was entirely ruined in 1808. However, a stone inscription reading LEO DUS VINC was uncovered near the corpse, hinting at da Vinci’s name.

Leonardo da Vinci's Tomb in Saint-Hubert Chapel (Amboise). (CC BY SA 3.0)

DNA Testing Dilemmas

The aforementioned bones, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, would be rediscovered in 1874 and reburied in the chapel of Saint-Hubert at the Château d'Amboise. What confuses things, however, is that researchers can’t get permission to conduct DNA testing and further analysis of the bones due to ethical reasons.

Ironically, another team of researchers seeking to unveil the true identity of the mysterious model who sat for Leonardo da Vinci’s world renowned painting, The Mona Lisa, had issues with DNA testing as well, but for different reasons. As Liz Leafloor reported in a previous Ancient Origins article, Italian archaeologists claim to own fragments of bone which they are certain belonged to Lisa Gherardini Del Giocondo —the woman thought to have sat for da Vinci’s famous painting — but the remains cannot be DNA tested due to their decayed condition.

Mona Lisa, one of Leonardo da Vinci’s famous paintings. (Public Domain)

Researchers have tried studying the DNA of bone fragments which belonged to Lisa Gherardini Del Giocondo —the woman thought to have sat for this painting — but the remains cannot be DNA tested due to their decayed condition.

On the other hand, historian Agnese Sabato and Alessandro Vezzosi, founders of an organization titled Leonardo da Vinci Heritage to safeguard and promote his legacy, have been searching for biological traces of da Vinci since 2000 without any particular success. “We pieced together an archive of hundreds of Leonardo’s fingerprints, hoping to get some biological material. At that time, cracking da Vinci’s DNA code was just a wild dream. Now it’s a real possibility,” Vezzosi tells Seeker.

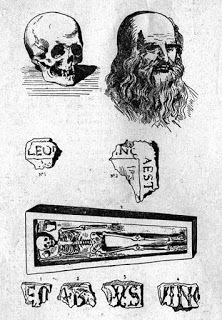

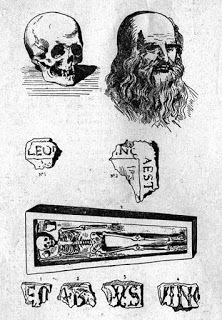

An illustration of Leonardo da Vinci's presumed remains in Amboise, France. (Museo Ideale Leonardo da Vinci)

The Hunt for da Vinci’s DNA Will Continue for a Couple More Years

The research is part of a broader project to trace da Vinci’s DNA by 2019, in honor of the 500th anniversary of his death. “The hunt for Leonardo DNA can now rely on a good, well-referenced genealogy,” Sabato told Seeker, explaining that all of the direct descendants come from Leonardo’s father. The researchers will be in communication with many international universities in order to achieve the widest possible scientific investigation on the relics and da Vinci’s descendants. The plan is to conduct DNA analysis on the relics and compare it to da Vinci’s descendants and bones found in recently identified da Vinci family burials throughout Tuscany.

Leonardo da Vinci statue outside the Uffizi, Florence, by Luigi Pampaloni. (Public Domain)

The researchers know that none of this will be easy and there’s a good chance that they won’t be able to extract any usable DNA from the relics.

Despite the difficulties waiting for them ahead, they are optimistic, “We now have a solid Da Vinci genealogy. We also hope the organic relic yields enough usable DNA,” Vezzosi told Seeker and adds, “Whatever the case. This relic has an extraordinary historic importance. We hope we will be soon able to put it on display.”

Top Image: A representation of Leonardo da Vinci. (Deriv.) (CC BY SA) Background: Structure of DNA. (Public Domain Pictures)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A team of Italian researchers claim that they have discovered two relics belonging to Leonardo da Vinci, which could them help in tracing the DNA of the legendary polymath whose work epitomized the Renaissance.

A Discovery of Immense Historical Importance? Could These be Da Vinci’s Relics? The peculiar relics were spotted during a long-term genealogical study of da Vinci’s family. “I can’t yet disclose the nature of these relics. I can only say that both are historically associated with Leonardo da Vinci. One is an object, the other is organic material,” Alessandro Vezzosi, director of the Museo Ideale in Vinci, told Seeker. The significance of such a discovery – if the relics are authentic– would be of immense historical value, since there are no known traces left of the Italian genius.

According to the “mainstream” version of history, the remains of Leonardo da Vinci, who died in 1519 in France, were scattered before the 19th century. However, in 1863 a corpse and large skull were discovered at the church of Saint-Florentin, where da Vinci was initially buried. Unfortunately, the place was pillaged during religious conflicts back in the 16th century and was entirely ruined in 1808. However, a stone inscription reading LEO DUS VINC was uncovered near the corpse, hinting at da Vinci’s name.

Leonardo da Vinci's Tomb in Saint-Hubert Chapel (Amboise). (CC BY SA 3.0)

DNA Testing Dilemmas

The aforementioned bones, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, would be rediscovered in 1874 and reburied in the chapel of Saint-Hubert at the Château d'Amboise. What confuses things, however, is that researchers can’t get permission to conduct DNA testing and further analysis of the bones due to ethical reasons.

Ironically, another team of researchers seeking to unveil the true identity of the mysterious model who sat for Leonardo da Vinci’s world renowned painting, The Mona Lisa, had issues with DNA testing as well, but for different reasons. As Liz Leafloor reported in a previous Ancient Origins article, Italian archaeologists claim to own fragments of bone which they are certain belonged to Lisa Gherardini Del Giocondo —the woman thought to have sat for da Vinci’s famous painting — but the remains cannot be DNA tested due to their decayed condition.

Mona Lisa, one of Leonardo da Vinci’s famous paintings. (Public Domain)

Researchers have tried studying the DNA of bone fragments which belonged to Lisa Gherardini Del Giocondo —the woman thought to have sat for this painting — but the remains cannot be DNA tested due to their decayed condition.

On the other hand, historian Agnese Sabato and Alessandro Vezzosi, founders of an organization titled Leonardo da Vinci Heritage to safeguard and promote his legacy, have been searching for biological traces of da Vinci since 2000 without any particular success. “We pieced together an archive of hundreds of Leonardo’s fingerprints, hoping to get some biological material. At that time, cracking da Vinci’s DNA code was just a wild dream. Now it’s a real possibility,” Vezzosi tells Seeker.

An illustration of Leonardo da Vinci's presumed remains in Amboise, France. (Museo Ideale Leonardo da Vinci)

The Hunt for da Vinci’s DNA Will Continue for a Couple More Years

The research is part of a broader project to trace da Vinci’s DNA by 2019, in honor of the 500th anniversary of his death. “The hunt for Leonardo DNA can now rely on a good, well-referenced genealogy,” Sabato told Seeker, explaining that all of the direct descendants come from Leonardo’s father. The researchers will be in communication with many international universities in order to achieve the widest possible scientific investigation on the relics and da Vinci’s descendants. The plan is to conduct DNA analysis on the relics and compare it to da Vinci’s descendants and bones found in recently identified da Vinci family burials throughout Tuscany.

Leonardo da Vinci statue outside the Uffizi, Florence, by Luigi Pampaloni. (Public Domain)

The researchers know that none of this will be easy and there’s a good chance that they won’t be able to extract any usable DNA from the relics.

Despite the difficulties waiting for them ahead, they are optimistic, “We now have a solid Da Vinci genealogy. We also hope the organic relic yields enough usable DNA,” Vezzosi told Seeker and adds, “Whatever the case. This relic has an extraordinary historic importance. We hope we will be soon able to put it on display.”

Top Image: A representation of Leonardo da Vinci. (Deriv.) (CC BY SA) Background: Structure of DNA. (Public Domain Pictures)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on May 12, 2017 01:00

May 11, 2017

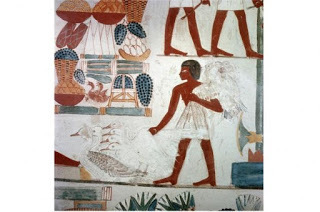

What did people eat in Ancient Egypt?

History Extra

The River Nile had a regular cycle that gave Egypt her three seasons: the time of inundation (when the land was covered with water), the time of coming forth (when the crops sprouted in the fertile fields), and the time of summer (when the harvested ground baked beneath the hot sun).

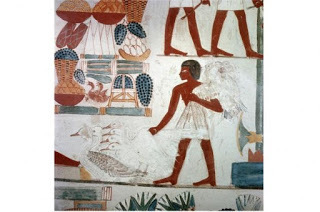

Most years saw a magnificent harvest of cereal (barley and emmer wheat, which could be used to make bread, cakes and beer); vegetables (beans, lentils, onions, garlic, leeks, lettuces and cucumbers), and fruits (including grapes, figs and dates). In addition there was abundant wild fowl and Nile fish, cattle farmed by the wealthy, and smaller animals (sheep, goats, pigs, geese) kept by the more humble households.

While the elite dined off meat, fruit, vegetables, and honey-sweetened cakes enhanced by the finest of wines, the poor were limited to a more monotonous diet of bread, fish, beans, onions and garlic washed down with a sweet, soupy beer.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Life Sciences at the University of Manchester, where she writes and teaches a number of Egyptology courses.

The River Nile had a regular cycle that gave Egypt her three seasons: the time of inundation (when the land was covered with water), the time of coming forth (when the crops sprouted in the fertile fields), and the time of summer (when the harvested ground baked beneath the hot sun).

Most years saw a magnificent harvest of cereal (barley and emmer wheat, which could be used to make bread, cakes and beer); vegetables (beans, lentils, onions, garlic, leeks, lettuces and cucumbers), and fruits (including grapes, figs and dates). In addition there was abundant wild fowl and Nile fish, cattle farmed by the wealthy, and smaller animals (sheep, goats, pigs, geese) kept by the more humble households.

While the elite dined off meat, fruit, vegetables, and honey-sweetened cakes enhanced by the finest of wines, the poor were limited to a more monotonous diet of bread, fish, beans, onions and garlic washed down with a sweet, soupy beer.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Life Sciences at the University of Manchester, where she writes and teaches a number of Egyptology courses.

Published on May 11, 2017 01:30

May 10, 2017

Who were gladiators in ancient Rome?

History Extra

Gladiatorial games were organised by the elite throughout the Roman empire in order to distract the population from the reality of daily life.

Most gladiators were purchased from slave markets, being chosen for their strength, stamina and good looks. Although taken from the lowest elements of society, the gladiator was a breed apart from the ‘normal’ slave or prisoner of war, being well-trained combatants whose one role in life was to fight and occasionally to kill for the amusement of the Roman mob.

Not all those who fought as gladiators were slaves or convicts, however. Some were citizens down on their luck (or heavily in debt) while some, like the emperor Commodus, simply did it for ‘fun’.

Whatever their reasons for ending up in the arena, gladiators were adored by the Roman public for their bravery and spirit. Their images appeared frequently in mosaics, wall paintings and on glassware and pottery.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication.

Gladiatorial games were organised by the elite throughout the Roman empire in order to distract the population from the reality of daily life.

Most gladiators were purchased from slave markets, being chosen for their strength, stamina and good looks. Although taken from the lowest elements of society, the gladiator was a breed apart from the ‘normal’ slave or prisoner of war, being well-trained combatants whose one role in life was to fight and occasionally to kill for the amusement of the Roman mob.

Not all those who fought as gladiators were slaves or convicts, however. Some were citizens down on their luck (or heavily in debt) while some, like the emperor Commodus, simply did it for ‘fun’.

Whatever their reasons for ending up in the arena, gladiators were adored by the Roman public for their bravery and spirit. Their images appeared frequently in mosaics, wall paintings and on glassware and pottery.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication.

Published on May 10, 2017 01:30

May 9, 2017

Why were they called the Tudors?

History Extra

The Tudors were originally from Wales, but they were not exactly of royal stock. The dynasty began with a rather scandalous secret marriage between a royal attendant, named Owain ap Maredydd ap Tudur, and the dowager queen Catherine of Valois, widow of King Henry V.

Surprisingly, the two were allowed to remain married, and their children were recognised as legitimate. But it would be two of their sons, Edmund and Jasper Tudor, who would rise at court, recognised as half brothers to Henry VI.

It was also Edmund’s son by his wife, Margaret Beaufort, Henry Tudor, who emerged as a strong claimant for the throne through his mother, a descendent of Edward III.

Lauren Mackay is the author of Inside the Tudor Court: Henry VIII and his Six Wives through the Life and Writings of the Spanish Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys (Amberley Publishing).

The Tudors were originally from Wales, but they were not exactly of royal stock. The dynasty began with a rather scandalous secret marriage between a royal attendant, named Owain ap Maredydd ap Tudur, and the dowager queen Catherine of Valois, widow of King Henry V.

Surprisingly, the two were allowed to remain married, and their children were recognised as legitimate. But it would be two of their sons, Edmund and Jasper Tudor, who would rise at court, recognised as half brothers to Henry VI.

It was also Edmund’s son by his wife, Margaret Beaufort, Henry Tudor, who emerged as a strong claimant for the throne through his mother, a descendent of Edward III.

Lauren Mackay is the author of Inside the Tudor Court: Henry VIII and his Six Wives through the Life and Writings of the Spanish Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys (Amberley Publishing).

Published on May 09, 2017 01:30