MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 59

April 28, 2017

Breaking News: Entrance to 3,700-Year-Old Previously Unknown Pyramid Discovered in Egypt

Ancient Origins

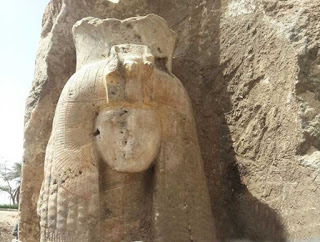

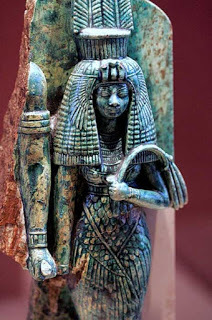

Egyptian archaeologists excavating in the Dahshur Necropolis at an area north of King Senefru's Bent Pyramid, have made an exciting discovery – a 13th dynasty pyramid that experts never knew existed. The sections that have been uncovered so far are in remarkably good condition, leading to hope and anticipation about what may lie within.

Pyramid’s Remains are in Very Good Condition

According to Ahram Online, Mahmoud Afifi, the head of the ancient Egyptian antiquities sector at the antiquities ministry, was the one who announced the new discovery, adding that the remains are in a very good condition and further excavation will take place to reveal more of the structure. The remains of the 13th Dynasty pyramid were found by an Egyptian archaeological mission excavating in the Dahshur Necropolis at an area north of King Senefru's Bent Pyramid.

What Has Been Discovered So Far?

Adel Okasha, director general of the Dahshur Necropolis stated that the uncovered fragments of the pyramid show part of its inner structure, which appears to be composed of a corridor that leads to the inside of the pyramid and a hall leading to a southern ramp in addition to a room that was found at the western end of the pyramid. Egypt Independent also mentions that a 15cm by 17cm alabaster block was also discovered in the corridor, inscribed with ten vertical hieroglyphic lines, which is currently under examination to decipher its meaning. A granite lintel and a collection of stone blocks showing the interior design of the pyramid were the last pieces found of the unearthed structure. Associated Press reports that due to the bent slope of its sides, the pyramid is believed to have been ancient Egypt's first attempt to build a smooth-sided pyramid.

The alabaster block with ten hieroglyphic lines (Ahram Online)

So who was the pyramid built for? A look at the 13th Dynasty may give some hints.

13th Dynasty of Egypt

Lasting for more than 150 years, the 13th Dynasty is best remembered for producing an uncertain number of kings. Some historians often combine it with Dynasties 11, 12 and 14 under the group title ‘Middle Kingdom’. Other historians, however, distinguish it from these dynasties and join it with Dynasties 14 through 17 as part of the ‘Second Intermediate Period’. The 13th Dynasty lasted from approximately 1803 until 1649 BC.

It was a direct continuation of the preceding 12th dynasty and as direct heirs to the kings of the 12th dynasty, pharaohs of the 13th dynasty reigned from Memphis over Middle and Upper Egypt, all the way to the second cataract to the south. Even though the decline in central power came gradually during this period, private monuments testify that Egypt was still a prosperous country. The power of the king was largely replaced with the power of the vizier, who kept the king as the symbolic leader. The 13th dynasty eventually came to end by military defeat to the Hyksos and with it the Middle Kingdom came to an end as well.

The Bent Pyramid seen from the foot of the Red Pyramid. Dahshur, Egypt (Looklex Egypt)

Further analysis will soon take place in order to learn more about the pyramid’s owner and the kingdom to which it belongs.

Top image: The corridor leading to the interior of the newly-discovered pyramid (Ahram Online)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Egyptian archaeologists excavating in the Dahshur Necropolis at an area north of King Senefru's Bent Pyramid, have made an exciting discovery – a 13th dynasty pyramid that experts never knew existed. The sections that have been uncovered so far are in remarkably good condition, leading to hope and anticipation about what may lie within.

Pyramid’s Remains are in Very Good Condition

According to Ahram Online, Mahmoud Afifi, the head of the ancient Egyptian antiquities sector at the antiquities ministry, was the one who announced the new discovery, adding that the remains are in a very good condition and further excavation will take place to reveal more of the structure. The remains of the 13th Dynasty pyramid were found by an Egyptian archaeological mission excavating in the Dahshur Necropolis at an area north of King Senefru's Bent Pyramid.

What Has Been Discovered So Far?

Adel Okasha, director general of the Dahshur Necropolis stated that the uncovered fragments of the pyramid show part of its inner structure, which appears to be composed of a corridor that leads to the inside of the pyramid and a hall leading to a southern ramp in addition to a room that was found at the western end of the pyramid. Egypt Independent also mentions that a 15cm by 17cm alabaster block was also discovered in the corridor, inscribed with ten vertical hieroglyphic lines, which is currently under examination to decipher its meaning. A granite lintel and a collection of stone blocks showing the interior design of the pyramid were the last pieces found of the unearthed structure. Associated Press reports that due to the bent slope of its sides, the pyramid is believed to have been ancient Egypt's first attempt to build a smooth-sided pyramid.

The alabaster block with ten hieroglyphic lines (Ahram Online)

So who was the pyramid built for? A look at the 13th Dynasty may give some hints.

13th Dynasty of Egypt

Lasting for more than 150 years, the 13th Dynasty is best remembered for producing an uncertain number of kings. Some historians often combine it with Dynasties 11, 12 and 14 under the group title ‘Middle Kingdom’. Other historians, however, distinguish it from these dynasties and join it with Dynasties 14 through 17 as part of the ‘Second Intermediate Period’. The 13th Dynasty lasted from approximately 1803 until 1649 BC.

It was a direct continuation of the preceding 12th dynasty and as direct heirs to the kings of the 12th dynasty, pharaohs of the 13th dynasty reigned from Memphis over Middle and Upper Egypt, all the way to the second cataract to the south. Even though the decline in central power came gradually during this period, private monuments testify that Egypt was still a prosperous country. The power of the king was largely replaced with the power of the vizier, who kept the king as the symbolic leader. The 13th dynasty eventually came to end by military defeat to the Hyksos and with it the Middle Kingdom came to an end as well.

The Bent Pyramid seen from the foot of the Red Pyramid. Dahshur, Egypt (Looklex Egypt)

Further analysis will soon take place in order to learn more about the pyramid’s owner and the kingdom to which it belongs.

Top image: The corridor leading to the interior of the newly-discovered pyramid (Ahram Online)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on April 28, 2017 02:00

April 27, 2017

Top 5 Jane Austen recipes

History Extra

Written by Pen Vogler, the editor of Penguin’s Great Food series, the book also features dishes Jane and her family were known to have enjoyed.

Here, we've selected our top five Jane Austen recipes.

Dinner with Mr Darcy by Pen Vogler is published by CICO Books

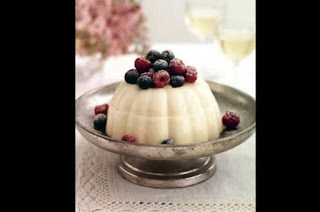

Flummery

Flummery is a white jelly, which was set in elegant molds or as shapes in clear jelly. Its delicate, creamy taste goes particularly well with rhubarb, strawberries, and raspberries. A modern version would be to add the puréed fruit to the ingredients, taking away the same volume of water.

1⁄2 cup/50g ground almonds

1 tsp natural rosewater (with no added alcohol)

A drop of natural almond extract

11⁄4 cups/300ml milk

1 1⁄4 cups heavy (double) cream

1–2 tbsp superfine (caster) sugar

5 gelatin leaves

1) Put the gelatin in a bowl and cover with cold water; leave for 4–5 minutes

2) Pour the milk, almonds, and sugar into a saucepan and heat slowly until just below boiling.

3) Squeeze out the excess water from the gelatin leaves and add them to the almond milk. Simmer for a few minutes, keeping it below boiling point. Let it cool a little and strain it through cheesecloth, or a very fine sieve

4) Whip the cream until thick, and then fold it into the tepid mixture. Wet your molds (essential, to make it turn out), put the flummery in (keeping some back for the hen’s nest recipe below if you’d like) and leave to stand in the fridge overnight

5) To serve: If you don’t have a jelly mold with a removable lid, dip the mold briefly into boiling water before turning out the flummery

"To make Flummery Put one ounce of bitter and one of sweet almonds into a basin, pour over them some boiling water to make the skins come off, which is called blanching. Strip off the skins and throw the kernels into cold water. Then take them out and beat them in a marble mortar with a little rosewater to keep them from oiling. When they are beat, put them into a pint of calf’s foot stock, set it over the fire and sweeten it to your taste with loaf sugar. As soon as it boils strain it through a piece of muslin or gauze. When a little cold put it into a pint of thick cream and keep stirring it often till it grows thick and cold. Wet your moulds in cold water and pour in the flummery, let it stand five or six hours at least before you turn them out. If you make the flummery stiff and wet the moulds, it will turn out without putting it into warm water, for water takes off the figures of the mould and makes the flummery look dull." ELIZABETH RAFFALD,THE EXPERIENCED ENGLISH HOUSEKEEPER, 1769

Pigeon Pie

It was the custom to put ‘nicely cleaned’ pigeon feet in the crust to label the contents (although sensible Margaret Dods says ‘we confess we see little use and no beauty in the practice’). Georgian recipes for pigeon pie called for whole birds, but I’ve suggested stewing the birds first, so your guests don’t have to pick out the bones.

Serves 6–8 as part of a picnic spread

4 rashers of streaky bacon, chopped

Slice of lean ham, chopped

4 pigeons with their livers tucked inside (the livers are hard to come by, but worth hunting out)

Flour, seasoned with salt and pepper

9 oz/250 g steak, diced (original cooks would have used rump steak, but you could use something cheaper like topside, diced across the grain of the meat)

Butter

Olive oil

Finely chopped parsley

2 white onions, roughly chopped

A bouquet garni of any of the following, tied together: thyme, parsley, marjoram, winter savory, a bay leaf

Beurre manie made with about 2 tsp butter and 2 tsp flour

1lb/500g rough puff pastry, chilled

Optional additions: 1 onion, peeled and quartered; 2 carrots, roughly chopped; 1 celery stick, roughly chopped

1) Brown the bacon and then the ham in a frying pan, then add the onions, if using, and cook until they are translucent. Transfer the mixture to a large saucepan

2) Flour the pigeons well and brown them all over in butter and olive oil in a frying pan, transferring them to the same large saucepan. Flour and brown the steak in the same way

3) Put the pigeons in a saucepan, and push the steak, bacon, and onions down all around them (choose a saucepan in which they will be quite tightly packed). Although the original recipe doesn’t include them, you may want to add the carrots and celery stick to improve the stock.

Add approximately 11⁄4 cups/300ml water, or enough to just cover the contents. Cover the pan, and simmer slowly until the meat comes off the pigeon bones — at least an hour.

Do not allow the pan to come to a boil or the beef will toughen. Remove from the heat.

4) When it is cool enough to handle, remove the steak and pigeons with a slotted spoon, and carefully pull the pigeon meat off the bones, keeping it as chunky as possible, and put it, with the livers from the cavity, with the steak. You should have a good thick sauce; if it is too thin, stir in the beurre manie a little at a time.

Wait for it to cook the flour, and thicken before adding any more, until you have the right consistency.

5) Preheat the oven to 375°F/190°C/Gas Mark 5. Roll out two-thirds of the pastry and line a pie dish about 3 inches/8cm deep, keeping a good 1⁄4 inch/5mm of pastry above the lip of the dish to allow for shrinkage

6) Prick the bottom of the pastry and bake blind for 12 minutes. Add the meat mixture and pour in enough gravy to come to within an inch of the top.

Roll out the remaining pastry to cover the top, crimping the edges together. Make a vent in the center, and use the trimmings to decorate.

You may like to use the point of the knife to make small slash marks in the shape of pigeon footprints — a nod to the “nicely cleaned feet” of the original recipe. Bake for 25– 30 minutes until the pastry is lightly golden, and cooked through

7) To serve, this is a juicier pie than we are used to for picnics, so you will need plates, and knives and forks, in the Georgian manner

Clean and season the pigeons well in the inside with pepper and salt. Put into each bird a little chopped parsley mixed with the livers parboiled and minced, and some bits of butter. Cover the bottom of the dish with a beef-steak, a few cutlets of veal, or slices of bacon, which is more suitable. Lay in the birds; put the seasoned gizzards, and, if approved, a few hard-boiled yolks of egg into the dish. A thin slice of lean ham laid on the breast of each bird is an improvement to the flavour. Cover the pie with puff paste. A half-hour will bake it.

Observation — It is common to stick two or three feet of pigeons or moorfowl into the centre of the cover of pies as a label to the contents, though we confess we see little use and no beauty in the practice. Forcemeat-balls may be added to enrich the pie. Some cooks lay the steaks above the birds, which is sensible, if not seemly. MARGARET DODS, THE COOK AND HOUSEWIFE’S MANUAL, 1826

Bath Olivers

These savory crackers (biscuits) were devised by William Oliver, an 18th-century physician in Bath after he realised the Bath Buns he had also invented were making his fashionable patients even fatter. They are perfect served with the English cheeses that the Georgian “higher sort” were beginning to enjoy. Makes 30–40 crackers

Pinch of salt

3 3⁄4 cups/500g all-purpose (plain) flour

2 tablespoons/30g butter

1⁄4 oz/7g sachet active dried yeast

2⁄3 cup/150ml milk

1) Preheat the oven to 325°F/160°C/Gas Mark 3

2) Sift the flour into a bowl and add the dried yeast and salt.Warm the butter and milk together, make a well in the flour and slowly add the liquid, stirring the flour into the center until you have a dough. Add some warm water if necessary

3) Knead the dough on a floured surface until smooth; put it back in the bowl, cover and let it rise in a warm place for 30 minutes

4) Roll out well on a floured surface several times, folding the dough on itself, until it is very thin

5) Cut out with a circular biscuit cutter and prick the surface with a fork

6) Bake for 20–30 minutes until they are hard and bone-colored; if they are turning color, turn the oven down to 300°F/150°C/Gas Mark 2

7) To serve: With a rich local dairy industry, Jane’s circle and characters were likely to have often served local cheeses, including the famous Somerset Cheddar.

Mr Elton gives a clue to what a cheese course might consist of when he unromantically describes his whole dinner of the previous night to Harriet, when Emma overtakes them “and that she was herself come in for the Stilton cheese, the north Wiltshire, the butter, the celery, the beet-root and all the dessert”.

Mrs Norris happily gets both a receipt for and a sample of “a famous cream cheese” from the housekeeper at Sotherton. Mrs Austen describes “good Warwickshire cheese” made in the “delightful dairy” at Stoneleigh Abbey.

To Make Ollivers Biscuits Take 3llb of flour, 1⁄2 a pint of small beer barm. Take some milk and warm it a little put it to your barm and lay a spunge, let it lay for one hour. Then take a quarter of a pound of butter and warm up with some milk and mix your spunge and lay it to rise before the fire. Roll it out in thin cakes, bake it in a slow oven. (You must put a little salt in your flour, but not much, use them before the fire before you put them in the oven).

MARTHA LLOYD’S HOUSEHOLD BOOK

Negus

This mulled wine, created by Colonel Francis Negus (d.1732), was served at the balls in Mansfield Park and The Watsons, and was often offered to guests before their chilly journey home. By Victorian times it was thought to be the thing for children’s birthday parties! This version is safer served to adults.

Serves 16-20

1 x 25 fl oz/75cl bottle of port

25 fl oz/750 ml water

1–2 tbsp brown sugar

Zest and juice of 1 lemon

About 1 tsp freshly grated nutmeg Optional extra spices: 1 cinnamon stick and/or 8 whole cloves

Segments of orange and lemon, to serve

1) Put the water in a saucepan and add the lemon zest, a tablespoon of sugar and the spices. Bring it to a boil and let it simmer very gently for 10–15 minutes. Add the lemon juice

2) Strain, return to the saucepan and reheat. Add the port; taste it, and add a little more sugar if you like. Pour in the port and heat very gently to serving temperature. Put slices of lemon and/or orange into glasses before pouring in the Negus — or serve it from a pitcher (jug)

Miss Debary's Marmalade

Miss Debary was one of the “endless Debarys”; four sisters unloved by Jane who said they were “odious’” (letter to Cassandra 8 September 1816), and had bad breath! (letter to Cassandra, 20 November 1800). Marmalade was made from all kinds of fruit and eaten for dessert until the Scots made it from bitter Seville oranges and started serving it for breakfast at the end of the 18th century.

Makes 6 x 1 lb (450g) jars

1.5kg (3 1⁄4 lb) Seville oranges

2 sweet oranges

1 scant gallon/3.5 litres water

Juice of 2 lemons

About 6 lb/2.75 kg preserving sugar

1) Weigh the fruit and to each 18 oz/500g of fruit weigh out 26 oz/750g sugar. Quarter the fruit and cut off the rind, taking off a little of the pith if you want a sweeter marmalade

2) Boil the rind in water for 11⁄2 –2 hours; there should be a third of the water left. When it is cool, cut the rind into thin slices about 3⁄8 –3⁄4 inch/1–2cm long; Georgian cooks called these “chips”.

Chop the pulp and pick out the seeds (pips) and pith, or push it through a sieve. Put the chips, pulp and lemon juice into the water used to boil the rinds, and bring to a boil.

Add the sugar and boil vigorously for twenty minutes, stirring to make sure it doesn’t catch on the bottom. When you have put the marmalade on to boil, leave a saucer in the fridge and put your jars on baking sheets into the oven at 350°F/180°C/Gas Mark 4 and leave them to sterilize for 20 minutes

3) After 20 minutes, put a little of the marmalade onto the cold plate. If it sets, it is ready; if not, test every five minutes until you get a set

4) Let the marmalade cool a little before decanting it into the hot jars. When it is cold, put wax paper on the surface, before adding the lids

Written by Pen Vogler, the editor of Penguin’s Great Food series, the book also features dishes Jane and her family were known to have enjoyed.

Here, we've selected our top five Jane Austen recipes.

Dinner with Mr Darcy by Pen Vogler is published by CICO Books

Flummery

Flummery is a white jelly, which was set in elegant molds or as shapes in clear jelly. Its delicate, creamy taste goes particularly well with rhubarb, strawberries, and raspberries. A modern version would be to add the puréed fruit to the ingredients, taking away the same volume of water.

1⁄2 cup/50g ground almonds

1 tsp natural rosewater (with no added alcohol)

A drop of natural almond extract

11⁄4 cups/300ml milk

1 1⁄4 cups heavy (double) cream

1–2 tbsp superfine (caster) sugar

5 gelatin leaves

1) Put the gelatin in a bowl and cover with cold water; leave for 4–5 minutes

2) Pour the milk, almonds, and sugar into a saucepan and heat slowly until just below boiling.

3) Squeeze out the excess water from the gelatin leaves and add them to the almond milk. Simmer for a few minutes, keeping it below boiling point. Let it cool a little and strain it through cheesecloth, or a very fine sieve

4) Whip the cream until thick, and then fold it into the tepid mixture. Wet your molds (essential, to make it turn out), put the flummery in (keeping some back for the hen’s nest recipe below if you’d like) and leave to stand in the fridge overnight

5) To serve: If you don’t have a jelly mold with a removable lid, dip the mold briefly into boiling water before turning out the flummery

"To make Flummery Put one ounce of bitter and one of sweet almonds into a basin, pour over them some boiling water to make the skins come off, which is called blanching. Strip off the skins and throw the kernels into cold water. Then take them out and beat them in a marble mortar with a little rosewater to keep them from oiling. When they are beat, put them into a pint of calf’s foot stock, set it over the fire and sweeten it to your taste with loaf sugar. As soon as it boils strain it through a piece of muslin or gauze. When a little cold put it into a pint of thick cream and keep stirring it often till it grows thick and cold. Wet your moulds in cold water and pour in the flummery, let it stand five or six hours at least before you turn them out. If you make the flummery stiff and wet the moulds, it will turn out without putting it into warm water, for water takes off the figures of the mould and makes the flummery look dull." ELIZABETH RAFFALD,THE EXPERIENCED ENGLISH HOUSEKEEPER, 1769

Pigeon Pie

It was the custom to put ‘nicely cleaned’ pigeon feet in the crust to label the contents (although sensible Margaret Dods says ‘we confess we see little use and no beauty in the practice’). Georgian recipes for pigeon pie called for whole birds, but I’ve suggested stewing the birds first, so your guests don’t have to pick out the bones.

Serves 6–8 as part of a picnic spread

4 rashers of streaky bacon, chopped

Slice of lean ham, chopped

4 pigeons with their livers tucked inside (the livers are hard to come by, but worth hunting out)

Flour, seasoned with salt and pepper

9 oz/250 g steak, diced (original cooks would have used rump steak, but you could use something cheaper like topside, diced across the grain of the meat)

Butter

Olive oil

Finely chopped parsley

2 white onions, roughly chopped

A bouquet garni of any of the following, tied together: thyme, parsley, marjoram, winter savory, a bay leaf

Beurre manie made with about 2 tsp butter and 2 tsp flour

1lb/500g rough puff pastry, chilled

Optional additions: 1 onion, peeled and quartered; 2 carrots, roughly chopped; 1 celery stick, roughly chopped

1) Brown the bacon and then the ham in a frying pan, then add the onions, if using, and cook until they are translucent. Transfer the mixture to a large saucepan

2) Flour the pigeons well and brown them all over in butter and olive oil in a frying pan, transferring them to the same large saucepan. Flour and brown the steak in the same way

3) Put the pigeons in a saucepan, and push the steak, bacon, and onions down all around them (choose a saucepan in which they will be quite tightly packed). Although the original recipe doesn’t include them, you may want to add the carrots and celery stick to improve the stock.

Add approximately 11⁄4 cups/300ml water, or enough to just cover the contents. Cover the pan, and simmer slowly until the meat comes off the pigeon bones — at least an hour.

Do not allow the pan to come to a boil or the beef will toughen. Remove from the heat.

4) When it is cool enough to handle, remove the steak and pigeons with a slotted spoon, and carefully pull the pigeon meat off the bones, keeping it as chunky as possible, and put it, with the livers from the cavity, with the steak. You should have a good thick sauce; if it is too thin, stir in the beurre manie a little at a time.

Wait for it to cook the flour, and thicken before adding any more, until you have the right consistency.

5) Preheat the oven to 375°F/190°C/Gas Mark 5. Roll out two-thirds of the pastry and line a pie dish about 3 inches/8cm deep, keeping a good 1⁄4 inch/5mm of pastry above the lip of the dish to allow for shrinkage

6) Prick the bottom of the pastry and bake blind for 12 minutes. Add the meat mixture and pour in enough gravy to come to within an inch of the top.

Roll out the remaining pastry to cover the top, crimping the edges together. Make a vent in the center, and use the trimmings to decorate.

You may like to use the point of the knife to make small slash marks in the shape of pigeon footprints — a nod to the “nicely cleaned feet” of the original recipe. Bake for 25– 30 minutes until the pastry is lightly golden, and cooked through

7) To serve, this is a juicier pie than we are used to for picnics, so you will need plates, and knives and forks, in the Georgian manner

Clean and season the pigeons well in the inside with pepper and salt. Put into each bird a little chopped parsley mixed with the livers parboiled and minced, and some bits of butter. Cover the bottom of the dish with a beef-steak, a few cutlets of veal, or slices of bacon, which is more suitable. Lay in the birds; put the seasoned gizzards, and, if approved, a few hard-boiled yolks of egg into the dish. A thin slice of lean ham laid on the breast of each bird is an improvement to the flavour. Cover the pie with puff paste. A half-hour will bake it.

Observation — It is common to stick two or three feet of pigeons or moorfowl into the centre of the cover of pies as a label to the contents, though we confess we see little use and no beauty in the practice. Forcemeat-balls may be added to enrich the pie. Some cooks lay the steaks above the birds, which is sensible, if not seemly. MARGARET DODS, THE COOK AND HOUSEWIFE’S MANUAL, 1826

Bath Olivers

These savory crackers (biscuits) were devised by William Oliver, an 18th-century physician in Bath after he realised the Bath Buns he had also invented were making his fashionable patients even fatter. They are perfect served with the English cheeses that the Georgian “higher sort” were beginning to enjoy. Makes 30–40 crackers

Pinch of salt

3 3⁄4 cups/500g all-purpose (plain) flour

2 tablespoons/30g butter

1⁄4 oz/7g sachet active dried yeast

2⁄3 cup/150ml milk

1) Preheat the oven to 325°F/160°C/Gas Mark 3

2) Sift the flour into a bowl and add the dried yeast and salt.Warm the butter and milk together, make a well in the flour and slowly add the liquid, stirring the flour into the center until you have a dough. Add some warm water if necessary

3) Knead the dough on a floured surface until smooth; put it back in the bowl, cover and let it rise in a warm place for 30 minutes

4) Roll out well on a floured surface several times, folding the dough on itself, until it is very thin

5) Cut out with a circular biscuit cutter and prick the surface with a fork

6) Bake for 20–30 minutes until they are hard and bone-colored; if they are turning color, turn the oven down to 300°F/150°C/Gas Mark 2

7) To serve: With a rich local dairy industry, Jane’s circle and characters were likely to have often served local cheeses, including the famous Somerset Cheddar.

Mr Elton gives a clue to what a cheese course might consist of when he unromantically describes his whole dinner of the previous night to Harriet, when Emma overtakes them “and that she was herself come in for the Stilton cheese, the north Wiltshire, the butter, the celery, the beet-root and all the dessert”.

Mrs Norris happily gets both a receipt for and a sample of “a famous cream cheese” from the housekeeper at Sotherton. Mrs Austen describes “good Warwickshire cheese” made in the “delightful dairy” at Stoneleigh Abbey.

To Make Ollivers Biscuits Take 3llb of flour, 1⁄2 a pint of small beer barm. Take some milk and warm it a little put it to your barm and lay a spunge, let it lay for one hour. Then take a quarter of a pound of butter and warm up with some milk and mix your spunge and lay it to rise before the fire. Roll it out in thin cakes, bake it in a slow oven. (You must put a little salt in your flour, but not much, use them before the fire before you put them in the oven).

MARTHA LLOYD’S HOUSEHOLD BOOK

Negus

This mulled wine, created by Colonel Francis Negus (d.1732), was served at the balls in Mansfield Park and The Watsons, and was often offered to guests before their chilly journey home. By Victorian times it was thought to be the thing for children’s birthday parties! This version is safer served to adults.

Serves 16-20

1 x 25 fl oz/75cl bottle of port

25 fl oz/750 ml water

1–2 tbsp brown sugar

Zest and juice of 1 lemon

About 1 tsp freshly grated nutmeg Optional extra spices: 1 cinnamon stick and/or 8 whole cloves

Segments of orange and lemon, to serve

1) Put the water in a saucepan and add the lemon zest, a tablespoon of sugar and the spices. Bring it to a boil and let it simmer very gently for 10–15 minutes. Add the lemon juice

2) Strain, return to the saucepan and reheat. Add the port; taste it, and add a little more sugar if you like. Pour in the port and heat very gently to serving temperature. Put slices of lemon and/or orange into glasses before pouring in the Negus — or serve it from a pitcher (jug)

Miss Debary's Marmalade

Miss Debary was one of the “endless Debarys”; four sisters unloved by Jane who said they were “odious’” (letter to Cassandra 8 September 1816), and had bad breath! (letter to Cassandra, 20 November 1800). Marmalade was made from all kinds of fruit and eaten for dessert until the Scots made it from bitter Seville oranges and started serving it for breakfast at the end of the 18th century.

Makes 6 x 1 lb (450g) jars

1.5kg (3 1⁄4 lb) Seville oranges

2 sweet oranges

1 scant gallon/3.5 litres water

Juice of 2 lemons

About 6 lb/2.75 kg preserving sugar

1) Weigh the fruit and to each 18 oz/500g of fruit weigh out 26 oz/750g sugar. Quarter the fruit and cut off the rind, taking off a little of the pith if you want a sweeter marmalade

2) Boil the rind in water for 11⁄2 –2 hours; there should be a third of the water left. When it is cool, cut the rind into thin slices about 3⁄8 –3⁄4 inch/1–2cm long; Georgian cooks called these “chips”.

Chop the pulp and pick out the seeds (pips) and pith, or push it through a sieve. Put the chips, pulp and lemon juice into the water used to boil the rinds, and bring to a boil.

Add the sugar and boil vigorously for twenty minutes, stirring to make sure it doesn’t catch on the bottom. When you have put the marmalade on to boil, leave a saucer in the fridge and put your jars on baking sheets into the oven at 350°F/180°C/Gas Mark 4 and leave them to sterilize for 20 minutes

3) After 20 minutes, put a little of the marmalade onto the cold plate. If it sets, it is ready; if not, test every five minutes until you get a set

4) Let the marmalade cool a little before decanting it into the hot jars. When it is cold, put wax paper on the surface, before adding the lids

Published on April 27, 2017 02:00

April 26, 2017

The 10 best English queens in history

History Extra

1) Bertha of Kent (539–c612)

Perhaps the most well known of all the pre-Conquest queens, Bertha played a crucial role in the establishment of Christianity in England. She was the daughter of the Christian king, Charibert I of Paris, who insisted that she be free to practise her own religion when she married the pagan king, Æthelbert of Kent.

Bertha crossed the Channel with her chaplain, Bishop Liuthard, and the pair converted an old Roman building into a chapel. She discussed her beliefs with her husband, ensuring that he welcomed the pope’s missionary, St Augustine, when he arrived in 597. She also corresponded directly with the pope, with the pontiff flattering her with comparisons to Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine.

Bertha and Æthelbert were buried together inside a Christian church in England’s first Christian kingdom.

2) Eadgifu (c904–after 966)

Few English queens were as influential as Eadgifu, the great matriarch of the House of Wessex. At 20, she became the third wife of the elderly King Edward the Elder. The marriage was unsurprisingly brief, and she was rarely at court during the reign of her stepson, Athelstan (reigned 924–39).

As Queen Mother, however, Eadgifu was pre-eminent, residing at court and advising her sons, Edmund (r939–46) and Eadred (r946–55). She was deeply involved in the monastic reform movement, patronising leading churchmen, including St Dunstan.

After Eadred’s death, her grandson, Eadwig, confiscated her property when she offered her support to his younger brother, Edgar. On becoming king in 959, Edgar restored his grandmother to her property. By the 960s, Eadgifu was elderly and living in semi-retirement, but she maintained an important role in the royal family. Her last public appearance was at the refoundation of the New Minster at Winchester in 966.

3) Matilda of Scotland (1080–1118)

Although a Scottish princess by birth, Matilda was also a descendant of the Anglo-Saxon kings of England, making her a dynastically important bride for Henry I, the son of William the Conqueror.

Matilda was raised first at Romsey Abbey and then Wilton Abbey. Her aunt, Abbess Christina of Romsey, was anxious that her niece should become a nun. She forced the girl to wear a veil, although Matilda reportedly tore it off and stamped on it when her aunt left the room. On his accession to the throne in 1100, Henry cemented his position by marrying Matilda – overcoming church objections that she was a nun.

The couple had two children but were frequently apart, with Matilda acting as regent of England during the king’s long absences in Normandy. She issued her own charters, and administered justice. She was also renowned for her charity, with calls for her canonisation following her death in 1118.

4) Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122–1204)

As Europe’s greatest heiress, Eleanor of Aquitaine was married at 15 to the monkish Louis VII of France. The couple proved incompatible and, with no son, divorced in 1152.

Within weeks Eleanor had married Henry of Anjou, who became king of England in 1154. Eleanor and Henry worked together to rule an empire that, as well as England, included much of modern France. By 1166, however, the couple, who had eight children, were estranged. Eleanor returned to Aquitaine in 1168.

Five years later she rebelled against Henry, and consequently spent the next 16 years imprisoned in Salisbury Castle. She returned to prominence as queen mother in 1189, governing England on behalf of her absent son, Richard I. Following his death in 1199, Eleanor helped to secure the throne for her youngest son, John. She was John’s greatest and most active supporter, finally dying in April 1204 at the age of 82.

5) Philippa of Hainault (1314–69)

Philippa of Hainault’s marriage to Edward III was agreed between his mother, Isabella of France, and her father, the Count of Hainault. The count provided troops for Isabella’s invasion of England, in which she deposed her husband, Edward II, in favour of her teenage son. Philippa and Edward couple were soon devoted to each other, producing 12 children.

Edward’s reign was dominated by war with France, and Philippa often accompanied him on campaign. At other times she served as regent, with her army capturing the king of Scots at the battle of Neville’s Cross in 1346. She was also a merciful influence upon her husband, regularly interceding with him on behalf of captives. She is remembered as the founder of Queen’s College, Oxford and as a patron of scholars.

Philippa, who was queen for just over 40 years, was the archetypal medieval queen, and one on whom many later queens modelled themselves.

6) Elizabeth I (1533–1603)

No list of the best English queens is complete without Elizabeth I, who reigned between 1558 and 1603. Elizabeth was the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, and had an unpromising start, being declared illegitimate following her mother’s execution. She survived interrogation and imprisonment during the reigns of her half-siblings to become England’s greatest ruling queen.

Elizabeth presided over a period of exploration and great invention, as well as the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. She also ordered the execution of her Catholic cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1587. One of her first acts as queen was to create a Protestant religious settlement for the Church of England, which has proved lasting.

At times ruthless, the queen refused to share power with a husband, although she ultimately paved the way for the smooth succession of her cousin, James VI of Scotland, and the union of the two crowns.

7) Anne (1665–1714)

Anne may seem a surprising choice as one of England’s best queens but, as the first monarch of a united Great Britain, she deserves her place.

Anne was the younger daughter of the Catholic James II and VII. She helped to spread rumours that James’s son, ‘the Old Pretender’, had been smuggled into his mother’s chamber in a warming pan at his birth in 1688. When her Protestant brother-in-law, William of Orange, invaded, Anne joined with him against her father.

She was a virtual invalid by the time she succeeded William in 1702, but presided over an important period in British history, including the Duke of Marlborough’s victories in the War of the Spanish Succession, and the Act of Union of 1707, which established her as queen of Great Britain.

Although she endured 17 pregnancies, Anne left no heir, and her Protestant cousin, George of Hanover, succeeded her in 1714.

8) Caroline of Ansbach (1683–1737)

Caroline of Ansbach was one of the most politically influential queen consorts, and is popularly considered to be the power behind George II’s throne. She was highly intelligent, managing affairs in such a way that her husband never suspected her true influence. In 1727, for example, when George decided to replace his father’s prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole, with his own candidate, Caroline was able to quietly persuade her husband that it was his idea that Walpole should remain.

She worked closely with Walpole throughout the reign, with the pair meeting to discuss policy privately before raising it with George, manipulating him to ensure that he followed their wishes. She also acted as regent during the king’s absences in Germany.

Although he was never faithful, George was devoted to Caroline – on her deathbed when she urged him to remarry, he refused, saying he would only have mistresses. He was devastated when she died in 1737.

9) Victoria (1819–1901)

Victoria, who came to the throne as an 18-year-old in 1837, holds the record as Britain’s longest-reigning monarch. Her reign of more than 60 years saw great changes: she presided over the peak of Britain’s power and influence, while her nine children married into most of the royal houses of Europe.

Victoria married her cousin, Prince Albert, in 1840, and remained devoted to him for the rest of her life – she entered perpetual mourning following his death in 1861. She was, however, able to retain control of her affairs, regularly meeting with her prime ministers, as well as becoming empress of India in 1876. She reached the peak of her popularity at her golden jubilee in 1887 and diamond jubilee in 1897.

Old age finally caught up with the queen on 22 January 1901, when she died at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight.

10) Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (1900–2002)

While Victoria was Britain’s longest-reigning monarch, the longest-lived queen was Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (better known as the Queen Mother), who was 101 when she died in 2002.

Her husband, George VI, became king unexpectedly in 1936 following the abdication of his elder brother, Edward VIII. The couple proved a successful team, with Elizabeth coming into her own during the Second World War. Hitler is supposed to have called her the most dangerous woman in Europe and, from the outset, she strove to improve British morale. She refused to allow her two daughters to be evacuated, while declaring that she could “now look the East End in the face” when Buckingham Palace was bombed.

Elizabeth spent half a century as Queen Mother after her husband’s death in 1952, during which time she was arguably the most popular member of the royal family.

1) Bertha of Kent (539–c612)

Perhaps the most well known of all the pre-Conquest queens, Bertha played a crucial role in the establishment of Christianity in England. She was the daughter of the Christian king, Charibert I of Paris, who insisted that she be free to practise her own religion when she married the pagan king, Æthelbert of Kent.

Bertha crossed the Channel with her chaplain, Bishop Liuthard, and the pair converted an old Roman building into a chapel. She discussed her beliefs with her husband, ensuring that he welcomed the pope’s missionary, St Augustine, when he arrived in 597. She also corresponded directly with the pope, with the pontiff flattering her with comparisons to Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine.

Bertha and Æthelbert were buried together inside a Christian church in England’s first Christian kingdom.

2) Eadgifu (c904–after 966)

Few English queens were as influential as Eadgifu, the great matriarch of the House of Wessex. At 20, she became the third wife of the elderly King Edward the Elder. The marriage was unsurprisingly brief, and she was rarely at court during the reign of her stepson, Athelstan (reigned 924–39).

As Queen Mother, however, Eadgifu was pre-eminent, residing at court and advising her sons, Edmund (r939–46) and Eadred (r946–55). She was deeply involved in the monastic reform movement, patronising leading churchmen, including St Dunstan.

After Eadred’s death, her grandson, Eadwig, confiscated her property when she offered her support to his younger brother, Edgar. On becoming king in 959, Edgar restored his grandmother to her property. By the 960s, Eadgifu was elderly and living in semi-retirement, but she maintained an important role in the royal family. Her last public appearance was at the refoundation of the New Minster at Winchester in 966.

3) Matilda of Scotland (1080–1118)

Although a Scottish princess by birth, Matilda was also a descendant of the Anglo-Saxon kings of England, making her a dynastically important bride for Henry I, the son of William the Conqueror.

Matilda was raised first at Romsey Abbey and then Wilton Abbey. Her aunt, Abbess Christina of Romsey, was anxious that her niece should become a nun. She forced the girl to wear a veil, although Matilda reportedly tore it off and stamped on it when her aunt left the room. On his accession to the throne in 1100, Henry cemented his position by marrying Matilda – overcoming church objections that she was a nun.

The couple had two children but were frequently apart, with Matilda acting as regent of England during the king’s long absences in Normandy. She issued her own charters, and administered justice. She was also renowned for her charity, with calls for her canonisation following her death in 1118.

4) Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122–1204)

As Europe’s greatest heiress, Eleanor of Aquitaine was married at 15 to the monkish Louis VII of France. The couple proved incompatible and, with no son, divorced in 1152.

Within weeks Eleanor had married Henry of Anjou, who became king of England in 1154. Eleanor and Henry worked together to rule an empire that, as well as England, included much of modern France. By 1166, however, the couple, who had eight children, were estranged. Eleanor returned to Aquitaine in 1168.

Five years later she rebelled against Henry, and consequently spent the next 16 years imprisoned in Salisbury Castle. She returned to prominence as queen mother in 1189, governing England on behalf of her absent son, Richard I. Following his death in 1199, Eleanor helped to secure the throne for her youngest son, John. She was John’s greatest and most active supporter, finally dying in April 1204 at the age of 82.

5) Philippa of Hainault (1314–69)

Philippa of Hainault’s marriage to Edward III was agreed between his mother, Isabella of France, and her father, the Count of Hainault. The count provided troops for Isabella’s invasion of England, in which she deposed her husband, Edward II, in favour of her teenage son. Philippa and Edward couple were soon devoted to each other, producing 12 children.

Edward’s reign was dominated by war with France, and Philippa often accompanied him on campaign. At other times she served as regent, with her army capturing the king of Scots at the battle of Neville’s Cross in 1346. She was also a merciful influence upon her husband, regularly interceding with him on behalf of captives. She is remembered as the founder of Queen’s College, Oxford and as a patron of scholars.

Philippa, who was queen for just over 40 years, was the archetypal medieval queen, and one on whom many later queens modelled themselves.

6) Elizabeth I (1533–1603)

No list of the best English queens is complete without Elizabeth I, who reigned between 1558 and 1603. Elizabeth was the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, and had an unpromising start, being declared illegitimate following her mother’s execution. She survived interrogation and imprisonment during the reigns of her half-siblings to become England’s greatest ruling queen.

Elizabeth presided over a period of exploration and great invention, as well as the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. She also ordered the execution of her Catholic cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1587. One of her first acts as queen was to create a Protestant religious settlement for the Church of England, which has proved lasting.

At times ruthless, the queen refused to share power with a husband, although she ultimately paved the way for the smooth succession of her cousin, James VI of Scotland, and the union of the two crowns.

7) Anne (1665–1714)

Anne may seem a surprising choice as one of England’s best queens but, as the first monarch of a united Great Britain, she deserves her place.

Anne was the younger daughter of the Catholic James II and VII. She helped to spread rumours that James’s son, ‘the Old Pretender’, had been smuggled into his mother’s chamber in a warming pan at his birth in 1688. When her Protestant brother-in-law, William of Orange, invaded, Anne joined with him against her father.

She was a virtual invalid by the time she succeeded William in 1702, but presided over an important period in British history, including the Duke of Marlborough’s victories in the War of the Spanish Succession, and the Act of Union of 1707, which established her as queen of Great Britain.

Although she endured 17 pregnancies, Anne left no heir, and her Protestant cousin, George of Hanover, succeeded her in 1714.

8) Caroline of Ansbach (1683–1737)

Caroline of Ansbach was one of the most politically influential queen consorts, and is popularly considered to be the power behind George II’s throne. She was highly intelligent, managing affairs in such a way that her husband never suspected her true influence. In 1727, for example, when George decided to replace his father’s prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole, with his own candidate, Caroline was able to quietly persuade her husband that it was his idea that Walpole should remain.

She worked closely with Walpole throughout the reign, with the pair meeting to discuss policy privately before raising it with George, manipulating him to ensure that he followed their wishes. She also acted as regent during the king’s absences in Germany.

Although he was never faithful, George was devoted to Caroline – on her deathbed when she urged him to remarry, he refused, saying he would only have mistresses. He was devastated when she died in 1737.

9) Victoria (1819–1901)

Victoria, who came to the throne as an 18-year-old in 1837, holds the record as Britain’s longest-reigning monarch. Her reign of more than 60 years saw great changes: she presided over the peak of Britain’s power and influence, while her nine children married into most of the royal houses of Europe.

Victoria married her cousin, Prince Albert, in 1840, and remained devoted to him for the rest of her life – she entered perpetual mourning following his death in 1861. She was, however, able to retain control of her affairs, regularly meeting with her prime ministers, as well as becoming empress of India in 1876. She reached the peak of her popularity at her golden jubilee in 1887 and diamond jubilee in 1897.

Old age finally caught up with the queen on 22 January 1901, when she died at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight.

10) Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (1900–2002)

While Victoria was Britain’s longest-reigning monarch, the longest-lived queen was Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (better known as the Queen Mother), who was 101 when she died in 2002.

Her husband, George VI, became king unexpectedly in 1936 following the abdication of his elder brother, Edward VIII. The couple proved a successful team, with Elizabeth coming into her own during the Second World War. Hitler is supposed to have called her the most dangerous woman in Europe and, from the outset, she strove to improve British morale. She refused to allow her two daughters to be evacuated, while declaring that she could “now look the East End in the face” when Buckingham Palace was bombed.

Elizabeth spent half a century as Queen Mother after her husband’s death in 1952, during which time she was arguably the most popular member of the royal family.

Published on April 26, 2017 01:30

April 25, 2017

5 things you (probably) didn’t know about the Tudors

History Extra

1) The Tudors should never have got anywhere near the throne

When Henry Tudor defeated Richard III at the battle of Bosworth in 1485, the vast majority of his subjects saw him as a usurper – and they were right. There were other claimants with stronger blood claims to the throne than his.

Henry’s own claim was on the side of his indomitable mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, who was the great granddaughter of John of Gaunt, fourth son of Edward III, and his third wife (and long-standing mistress), Katherine Swynford. But Katherine had given birth to John Beaufort (Henry’s great grandfather) when she was still John’s mistress, so Henry’s claim was through an illegitimate line – and a female one at that.

Little wonder that he was plagued by rivals and ‘pretenders’ for most of his reign.

2) School was for the ‘lucky’ few

Education was seen as something of a luxury for most Tudors, and it was usually the children of the rich who received anything approaching a decent schooling.

There were few books in Tudor schools, so pupils read from 'hornbooks' instead. Pages displaying the alphabet and religious material were attached to wooden boards and covered with a transparent sheet of cow horn (hence the name).

Discipline was much fiercer than it is today. Teachers would think nothing of punishing their pupils with 50 strokes of the cane, and wealthier parents would often pay for a ‘whipping-boy’ to take the punishment on behalf of their child. Barnaby Fitzpatrick undertook this thankless task for the young Edward VI, although the two boys did become best friends.

3) Tudor London was a mud bath

Andreas Franciscius, an Italian visitor to London in 1497, was horrified by what he found. Although he admired the “fine” architecture, he was disgusted by the “vast amount of evil-smelling mud" that covered the streets and lasted a long time – nearly the whole year round.

The citizens, therefore, in order to remove this mud and filth from their boots, are accustomed to spread fresh rushes on the floors of all houses, on which they clean the soles of their shoes when they come in.”

Franciscius added disapprovingly that the English people had “fierce tempers and wicked dispositions”, as well as “a great antipathy to foreigners”.

4) Edward VI’s dog was killed by his uncle

Edward was just nine years old when he became king, and his court was soon riven by faction. Although the king’s uncle, Edward Seymour, had been appointed Lord Protector, he was undermined by the behaviour of his hot-headed and ambitious brother, Thomas.

In January 1549, Thomas Seymour made a reckless attempt to kidnap the king. Breaking into Edward’s privy garden at Westminster, pistol in hand, Thomas tried to gain access to the king’s bedroom, but was lunged at by the boy’s pet spaniel.

Without thinking, he shot the dog dead, which prompted a furore as the royal guard rushed forward, thinking that an assassin was in the palace. Thomas Seymour was arrested and taken to the Tower. He was found guilty of treason shortly afterwards, and his own brother was obliged to sign the death warrant.

5) Elizabeth I owned more than 2,000 dresses

When her mother, Anne Boleyn, was executed, Elizabeth was so neglected by her father, Henry VIII, that she soon outgrew all of her clothes, and her servant was forced to write to ask for new ones.

Perhaps the memory of this humiliation prompted Elizabeth, as queen, to stuff her wardrobes with more than 2,000 beautiful dresses, all in rich fabrics and gorgeous colours.

But despite her enormous collection, she always wanted more. When one of her maids of honour, Lady Mary Howard, appeared in court wearing a strikingly ostentatious gown, the queen was so jealous that she stole it, and paraded around court in it herself.

1) The Tudors should never have got anywhere near the throne

When Henry Tudor defeated Richard III at the battle of Bosworth in 1485, the vast majority of his subjects saw him as a usurper – and they were right. There were other claimants with stronger blood claims to the throne than his.

Henry’s own claim was on the side of his indomitable mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, who was the great granddaughter of John of Gaunt, fourth son of Edward III, and his third wife (and long-standing mistress), Katherine Swynford. But Katherine had given birth to John Beaufort (Henry’s great grandfather) when she was still John’s mistress, so Henry’s claim was through an illegitimate line – and a female one at that.

Little wonder that he was plagued by rivals and ‘pretenders’ for most of his reign.

2) School was for the ‘lucky’ few

Education was seen as something of a luxury for most Tudors, and it was usually the children of the rich who received anything approaching a decent schooling.

There were few books in Tudor schools, so pupils read from 'hornbooks' instead. Pages displaying the alphabet and religious material were attached to wooden boards and covered with a transparent sheet of cow horn (hence the name).

Discipline was much fiercer than it is today. Teachers would think nothing of punishing their pupils with 50 strokes of the cane, and wealthier parents would often pay for a ‘whipping-boy’ to take the punishment on behalf of their child. Barnaby Fitzpatrick undertook this thankless task for the young Edward VI, although the two boys did become best friends.

3) Tudor London was a mud bath

Andreas Franciscius, an Italian visitor to London in 1497, was horrified by what he found. Although he admired the “fine” architecture, he was disgusted by the “vast amount of evil-smelling mud" that covered the streets and lasted a long time – nearly the whole year round.

The citizens, therefore, in order to remove this mud and filth from their boots, are accustomed to spread fresh rushes on the floors of all houses, on which they clean the soles of their shoes when they come in.”

Franciscius added disapprovingly that the English people had “fierce tempers and wicked dispositions”, as well as “a great antipathy to foreigners”.

4) Edward VI’s dog was killed by his uncle

Edward was just nine years old when he became king, and his court was soon riven by faction. Although the king’s uncle, Edward Seymour, had been appointed Lord Protector, he was undermined by the behaviour of his hot-headed and ambitious brother, Thomas.

In January 1549, Thomas Seymour made a reckless attempt to kidnap the king. Breaking into Edward’s privy garden at Westminster, pistol in hand, Thomas tried to gain access to the king’s bedroom, but was lunged at by the boy’s pet spaniel.

Without thinking, he shot the dog dead, which prompted a furore as the royal guard rushed forward, thinking that an assassin was in the palace. Thomas Seymour was arrested and taken to the Tower. He was found guilty of treason shortly afterwards, and his own brother was obliged to sign the death warrant.

5) Elizabeth I owned more than 2,000 dresses

When her mother, Anne Boleyn, was executed, Elizabeth was so neglected by her father, Henry VIII, that she soon outgrew all of her clothes, and her servant was forced to write to ask for new ones.

Perhaps the memory of this humiliation prompted Elizabeth, as queen, to stuff her wardrobes with more than 2,000 beautiful dresses, all in rich fabrics and gorgeous colours.

But despite her enormous collection, she always wanted more. When one of her maids of honour, Lady Mary Howard, appeared in court wearing a strikingly ostentatious gown, the queen was so jealous that she stole it, and paraded around court in it herself.

Published on April 25, 2017 02:00

April 24, 2017

Just How Rich Were the Inhabitants of Magna Graecia Really?

Ancient Origins

A team of archaeologists excavating in the Italian city of Paestum (Poseidonia), has uncovered the remnants of a palatial structure and indispensable ceramics. Almost 2,500 years ago, Poseidonia was part of Magna Graecia’s (“Great Greece’s”) most significant sanctuaries.

Magna Graecia’s Glorious Past

Magna Graecia was the name given in antiquity by the Romans to the group of Greek colonies which encircled the shores of Southern Italy, in the present-day regions of Campania, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria and Sicily that were extensively populated by Greek settlers.

The name is not found in any extant author earlier than Polybius, who mentions the cities of Magna Graecia during the time of Pythagoras by using the expression, “the country that was then called Magna Graecia” (Pol. 2.39). However, many historians believe that the name possibly had arisen already at an early stage of Greek history, probably during a period that the Greek colonies in Italy were at the height of their power and prosperity and before many famous city-states of Greece had reached their peak.

The Greek expansion into Southern Italy began in the 8th century BC and the settlers would bring with them their Hellenic civilization, which was to leave a lasting imprint in Italy, such as in the culture of ancient Rome. Greek colonists founded a number of city states on both coasts of the peninsula from the Bay of Naples and the Gulf of Taranto southwards and all-round the narrow coastal plain of Sicily.

Ancient Greek colonies and their dialect groupings in Southern Italy (Magna Graecia). (Public Domain)

In their hey-day these city states, founded by farmers, traders, and craftsmen, represented the “new rich” of the Greek world. Their temples were bigger, their houses more ornate, and their aristocracy lived a life of pampered luxury. Trade between the Italian colonies and their founding cities in mainland Greece prospered, and Magna Graecia became the center for two philosophical groups: Parmenides founded a school at Elea and Pythagoras another at Croton. Croton was also famed to have the finest physicians in the Greek world and was the home of one of the greatest ancient athletes, Milo, who was a six times champion in wrestling at both the Olympic and Pythian games.

Coins from Magna Graecia. (CC BY SA 2.5)

New Findings at Poseidonia Clearly Show the Affluence of its Greek Founders

Despite many of the Greek inhabitants of Southern Italy getting totally Italianized during the Middle Ages, the immense impact of Greek culture and language has survived to present day. One major example of this is Griko people, an ethnic Greek community of Southern Italy that can be mainly found in regions of Calabria and Apulia.

Another major example would be all the discoveries that have taken place in Southern Italy, with the most recent being a block-built building and the new artifacts in Poseidonia as Greek Reporter recently reported.

Archaeologists excavating a structure which is believed to date from when the settlement of Poseidonia was founded in southern Italy. (Parco Archeologico di Paestum)

Poseidonia was established by Greek colonists from the Gulf of Taranto around 400 BC. The city would later fall under the rule of an indigenous Italic people known as the Lucanians, who changed the city’s name.

The remains of the recently unearthed large structure, which most likely served as either a palace or a very luxurious household, seems to have been constructed within the same time period as the Doric-style temples of the Greek gods Athena, Hera, and Poseidon - for which Poseidonia was best known in antiquity.

Second temple of Hera, also called Neptune temple or Poseidon temple, Paestum (Poseidonia), Campania, Italy. (Norbert Nagel/CC BY SA 3.0)

Besides the large building, as New Historian reports, archaeologists have also uncovered a respectable amount of Attic red-figure style pottery – a proficiency invented in Athens after the Greek Dark Age -which influenced the rest of Greece, especially Boeotia, Corinth, the Cyclades, and the Ionian colonies in the east Aegean – along with other luxury objects, which clearly show how rich the city’s Greek founders became catering to the travelers and believers who came to worship at the temples. Other finds include vessels used for cooking, eating, and drinking.

An Attic vase fragment found at the Paestum site in southern Italy. It depicts the Greek god Hermes. (Parco Archeologico di Paestum)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Top Image: A richly decorate vase in the National Archaeological Museum of Paestum, Italy. Source: CC BY SA 3.0

A team of archaeologists excavating in the Italian city of Paestum (Poseidonia), has uncovered the remnants of a palatial structure and indispensable ceramics. Almost 2,500 years ago, Poseidonia was part of Magna Graecia’s (“Great Greece’s”) most significant sanctuaries.

Magna Graecia’s Glorious Past

Magna Graecia was the name given in antiquity by the Romans to the group of Greek colonies which encircled the shores of Southern Italy, in the present-day regions of Campania, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria and Sicily that were extensively populated by Greek settlers.

The name is not found in any extant author earlier than Polybius, who mentions the cities of Magna Graecia during the time of Pythagoras by using the expression, “the country that was then called Magna Graecia” (Pol. 2.39). However, many historians believe that the name possibly had arisen already at an early stage of Greek history, probably during a period that the Greek colonies in Italy were at the height of their power and prosperity and before many famous city-states of Greece had reached their peak.

The Greek expansion into Southern Italy began in the 8th century BC and the settlers would bring with them their Hellenic civilization, which was to leave a lasting imprint in Italy, such as in the culture of ancient Rome. Greek colonists founded a number of city states on both coasts of the peninsula from the Bay of Naples and the Gulf of Taranto southwards and all-round the narrow coastal plain of Sicily.

Ancient Greek colonies and their dialect groupings in Southern Italy (Magna Graecia). (Public Domain)

In their hey-day these city states, founded by farmers, traders, and craftsmen, represented the “new rich” of the Greek world. Their temples were bigger, their houses more ornate, and their aristocracy lived a life of pampered luxury. Trade between the Italian colonies and their founding cities in mainland Greece prospered, and Magna Graecia became the center for two philosophical groups: Parmenides founded a school at Elea and Pythagoras another at Croton. Croton was also famed to have the finest physicians in the Greek world and was the home of one of the greatest ancient athletes, Milo, who was a six times champion in wrestling at both the Olympic and Pythian games.

Coins from Magna Graecia. (CC BY SA 2.5)

New Findings at Poseidonia Clearly Show the Affluence of its Greek Founders

Despite many of the Greek inhabitants of Southern Italy getting totally Italianized during the Middle Ages, the immense impact of Greek culture and language has survived to present day. One major example of this is Griko people, an ethnic Greek community of Southern Italy that can be mainly found in regions of Calabria and Apulia.

Another major example would be all the discoveries that have taken place in Southern Italy, with the most recent being a block-built building and the new artifacts in Poseidonia as Greek Reporter recently reported.

Archaeologists excavating a structure which is believed to date from when the settlement of Poseidonia was founded in southern Italy. (Parco Archeologico di Paestum)

Poseidonia was established by Greek colonists from the Gulf of Taranto around 400 BC. The city would later fall under the rule of an indigenous Italic people known as the Lucanians, who changed the city’s name.

The remains of the recently unearthed large structure, which most likely served as either a palace or a very luxurious household, seems to have been constructed within the same time period as the Doric-style temples of the Greek gods Athena, Hera, and Poseidon - for which Poseidonia was best known in antiquity.

Second temple of Hera, also called Neptune temple or Poseidon temple, Paestum (Poseidonia), Campania, Italy. (Norbert Nagel/CC BY SA 3.0)

Besides the large building, as New Historian reports, archaeologists have also uncovered a respectable amount of Attic red-figure style pottery – a proficiency invented in Athens after the Greek Dark Age -which influenced the rest of Greece, especially Boeotia, Corinth, the Cyclades, and the Ionian colonies in the east Aegean – along with other luxury objects, which clearly show how rich the city’s Greek founders became catering to the travelers and believers who came to worship at the temples. Other finds include vessels used for cooking, eating, and drinking.

An Attic vase fragment found at the Paestum site in southern Italy. It depicts the Greek god Hermes. (Parco Archeologico di Paestum)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Top Image: A richly decorate vase in the National Archaeological Museum of Paestum, Italy. Source: CC BY SA 3.0

Published on April 24, 2017 01:30

April 23, 2017

Tiller the Hun? Farmers in Roman Empire Converted to Hun Lifestyle

Ancient Origins

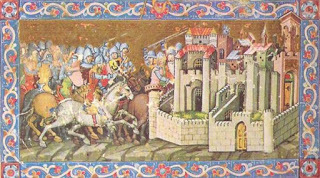

Marauding hordes of barbarian Huns, under their ferocious leader Attila, are often credited with triggering the fall of one of history's greatest empires: Rome.

Historians believe Hunnic incursions into Roman provinces bordering the Danube during the 5th century AD opened the floodgates for nomadic tribes to encroach on the empire. This caused a destabilization that contributed to collapse of Roman power in the West.

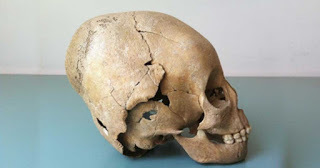

According to Roman accounts, the Huns brought only terror and destruction. However, research from the University of Cambridge on gravesite remains in the Roman frontier region of Pannonia (now Hungary) has revealed for the first time how ordinary people may have dealt with the arrival of the Huns.

A 14th-century chivalric-romanticized painting of the Huns laying siege to a city. (Public Domain)

Biochemical analyses of teeth and bone to test for diet and mobility suggest that, over the course of a lifetime, some farmers on the edge of empire left their homesteads to become Hun-like roaming herdsmen, and consequently, perhaps, took up arms with the tribes.

Other remains from the same gravesites show a dietary shift indicating some Hun discovered a settled way of life and the joys of agriculture -- leaving their wanderlust, and possibly their bloodlust, behind.

Lead researcher Dr Susanne Hakenbeck, from Cambridge's Department of Archaeology, says the Huns may have brought ways of life that appealed to some farmers in the area, as well learning from and settling among the locals. She says this could be evidence of the steady infiltration that shook an empire.

"We know from contemporary accounts that this was a time when treaties between tribes and Romans were forged and fractured, loyalties sworn and broken. The lifestyle shifts we see in the skeletons may reflect that turmoil," says Hakenbeck. "However, while written accounts of the last century of the Roman Empire focus on convulsions of violence, our new data appear to show some degree of cooperation and coexistence of people living in the frontier zone. Far from being a clash of cultures, alternating between lifestyles may have been an insurance policy in unstable political times."

For the study, published today in the journal PLOS ONE, Hakenbeck and colleagues tested skeletal remains at five 5th-century sites around Pannonia, including one in a former civic center as well as rural homesteads.

The team analyzed the isotope ratios of carbon, nitrogen, strontium and oxygen in bones and teeth. They compared this data to sites in central Germany, where typical farmers of the time lived, and locations in Siberia and Mongolia, home to nomadic herders up to the Mongol period and beyond.

A suggested path of Hunnic movement westwards (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The results allowed researchers to distinguish between settled agricultural populations and nomadic animal herders in the former Roman border area through isotopic traces of diet and mobility in the skeletons.

All the Pannonian gravesites not only held examples of both lifestyles, but also many individuals that shifted between lifestyles in both directions over the course of a lifetime. "The exchange of subsistence strategies is evidence for a way of life we don't see anywhere else in Europe at this time," says Hakenbeck.

She says there are no clear lifestyle patterns based on sex or accompanying grave goods, or even 'skull modification' -- the binding of the head as a baby to create a pointed skull -- commonly associated with the Hun.

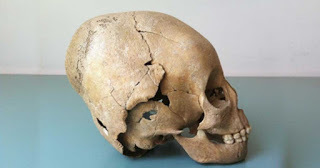

Lithographs of skulls by J. Basire (Public Domain)

"Nomadic animal herding and skull modification may be practices imported by Hun tribes into the bounds of empire and adopted by some of the agriculturalist inhabitants."

The diet of farmers was relatively boring, says Hakenbeck, consisting primarily of plants such as wheat, vegetables and pulses, with a modicum of meat and almost no fish.

The herders' diet on the other hand was high in animal protein and augmented with fish. They also ate large quantities of millet, which has a distinctive carbon isotope ratio that can be identified in human bones. Millet is a hardy plant that was hugely popular with nomadic populations of central Asia because it grows in a few short weeks.

Roman sources of the time were dismissive of this lifestyle. Ammianus Marcellinus, a Roman official, wrote of the Hun that they "care nothing for using the ploughshare, but they live upon flesh and an abundance of milk."

"While Roman authors considered them incomprehensibly uncivilised and barely human, it seems many of citizens at the edge of Rome's empire were drawn to the Hun lifestyle, just as some nomads took to a more settled way of life," says Hakenbeck.

However, there is one account that hints at the appeal of the Hun, that of Roman politician Priscus. While on a diplomatic mission to the court of Attila, he describes encountering a former merchant who had abandoned life in the Empire for that of the Hun enemy as, after war, they "live in inactivity, enjoying what they have got, and not at all, or very little, harassed."

Top image: Example of a modified skull, a practice assumed to be Hunnic that may have been appropriated by local farmers within the bounds of the Credit: Susanne Hakenbeck

The article ‘Tiller the Hun? Farmers in Roman Empire converted to Hun lifestyle -- and vice versa’ was originally published on Science Daily.

Source: University of Cambridge. "Tiller the Hun? Farmers in Roman Empire converted to Hun lifestyle -- and vice versa." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 22 March 2017.

www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/03...

Marauding hordes of barbarian Huns, under their ferocious leader Attila, are often credited with triggering the fall of one of history's greatest empires: Rome.

Historians believe Hunnic incursions into Roman provinces bordering the Danube during the 5th century AD opened the floodgates for nomadic tribes to encroach on the empire. This caused a destabilization that contributed to collapse of Roman power in the West.

According to Roman accounts, the Huns brought only terror and destruction. However, research from the University of Cambridge on gravesite remains in the Roman frontier region of Pannonia (now Hungary) has revealed for the first time how ordinary people may have dealt with the arrival of the Huns.

A 14th-century chivalric-romanticized painting of the Huns laying siege to a city. (Public Domain)

Biochemical analyses of teeth and bone to test for diet and mobility suggest that, over the course of a lifetime, some farmers on the edge of empire left their homesteads to become Hun-like roaming herdsmen, and consequently, perhaps, took up arms with the tribes.

Other remains from the same gravesites show a dietary shift indicating some Hun discovered a settled way of life and the joys of agriculture -- leaving their wanderlust, and possibly their bloodlust, behind.

Lead researcher Dr Susanne Hakenbeck, from Cambridge's Department of Archaeology, says the Huns may have brought ways of life that appealed to some farmers in the area, as well learning from and settling among the locals. She says this could be evidence of the steady infiltration that shook an empire.

"We know from contemporary accounts that this was a time when treaties between tribes and Romans were forged and fractured, loyalties sworn and broken. The lifestyle shifts we see in the skeletons may reflect that turmoil," says Hakenbeck. "However, while written accounts of the last century of the Roman Empire focus on convulsions of violence, our new data appear to show some degree of cooperation and coexistence of people living in the frontier zone. Far from being a clash of cultures, alternating between lifestyles may have been an insurance policy in unstable political times."

For the study, published today in the journal PLOS ONE, Hakenbeck and colleagues tested skeletal remains at five 5th-century sites around Pannonia, including one in a former civic center as well as rural homesteads.

The team analyzed the isotope ratios of carbon, nitrogen, strontium and oxygen in bones and teeth. They compared this data to sites in central Germany, where typical farmers of the time lived, and locations in Siberia and Mongolia, home to nomadic herders up to the Mongol period and beyond.

A suggested path of Hunnic movement westwards (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The results allowed researchers to distinguish between settled agricultural populations and nomadic animal herders in the former Roman border area through isotopic traces of diet and mobility in the skeletons.

All the Pannonian gravesites not only held examples of both lifestyles, but also many individuals that shifted between lifestyles in both directions over the course of a lifetime. "The exchange of subsistence strategies is evidence for a way of life we don't see anywhere else in Europe at this time," says Hakenbeck.

She says there are no clear lifestyle patterns based on sex or accompanying grave goods, or even 'skull modification' -- the binding of the head as a baby to create a pointed skull -- commonly associated with the Hun.

Lithographs of skulls by J. Basire (Public Domain)

"Nomadic animal herding and skull modification may be practices imported by Hun tribes into the bounds of empire and adopted by some of the agriculturalist inhabitants."

The diet of farmers was relatively boring, says Hakenbeck, consisting primarily of plants such as wheat, vegetables and pulses, with a modicum of meat and almost no fish.

The herders' diet on the other hand was high in animal protein and augmented with fish. They also ate large quantities of millet, which has a distinctive carbon isotope ratio that can be identified in human bones. Millet is a hardy plant that was hugely popular with nomadic populations of central Asia because it grows in a few short weeks.

Roman sources of the time were dismissive of this lifestyle. Ammianus Marcellinus, a Roman official, wrote of the Hun that they "care nothing for using the ploughshare, but they live upon flesh and an abundance of milk."

"While Roman authors considered them incomprehensibly uncivilised and barely human, it seems many of citizens at the edge of Rome's empire were drawn to the Hun lifestyle, just as some nomads took to a more settled way of life," says Hakenbeck.

However, there is one account that hints at the appeal of the Hun, that of Roman politician Priscus. While on a diplomatic mission to the court of Attila, he describes encountering a former merchant who had abandoned life in the Empire for that of the Hun enemy as, after war, they "live in inactivity, enjoying what they have got, and not at all, or very little, harassed."

Top image: Example of a modified skull, a practice assumed to be Hunnic that may have been appropriated by local farmers within the bounds of the Credit: Susanne Hakenbeck

The article ‘Tiller the Hun? Farmers in Roman Empire converted to Hun lifestyle -- and vice versa’ was originally published on Science Daily.