MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 60

April 18, 2017

Amazing Crystal Weapons Discovered Within 5,000-Year-Old Megalithic Tomb in Spain

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists in Spain have unearthed an extremely rare set of weapons, including a long dagger blade, twenty-five arrowheads and cores used for creating the artifacts, all made of crystal! The finding was made inside megalithic tombs dating to the 3 rd millennium BC in the southwest of Spain.

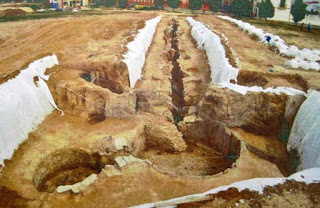

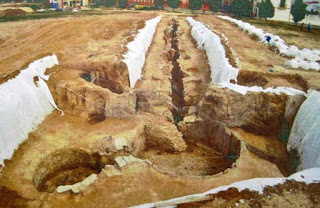

An excavation of megalithic tombs in Valencina de la Concepción in Spain led to the dramatic discovery of the rare relics, which experts described as exceptional and magnificently well-preserved. The objects are estimated to be over five thousand years old (dating back to at least 3000 BC). As Signs of the Times reports , the Montelirio tholos, excavated between 2007 and 2010, is a great megalithic construction which extends nearly 44 meters (144 ft) in total, constructed out of large slabs of slate. At least 25 individuals were found within the structure. Analyses suggested that there was one male and numerous females who had drunk a poison substance. The remains of the women sit in a circle in a chamber adjacent to the bones believed to be of their chief.

The crystal weapons were discovered inside the Montelirio tholos. Copyright: ipolca (ARTURO DEL PINO RUIZ)

Incredible Crystal Arrowheads

They also found "an extraordinary set of sumptuous grave goods...the most notable of which is an unspecified number of shrouds or clothes made of tens of thousands of perforated beads and decorated with amber beads,” according to the study.

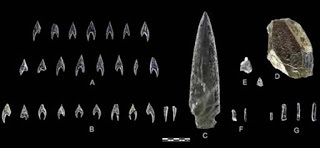

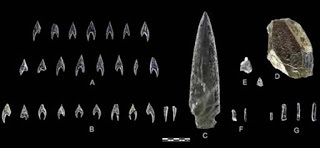

In addition to the human remains and textiles, the archaeologists found the large hoard of crystal arrowheads. The fact that they were discovered altogether indicates that they could have been a ritual offering at an altar. The arrowheads have the distinctive long lateral appendices of flint arrowheads from the region, but archaeologists noted that even greater skill must have been required to produce these unique features when using rock crystal.

A: Ontiveros arrowheads; B: Montelirio tholos arrowheads; C: Montelirio dagger blade; D: Montelirio tholos core; Montelirio knapping debris; F: Montelirio micro-blades; G: Montelirio tholos microblades. Photograph: Miguel Angel Blanco de la Rubia.

Corpse of a Young Male Discovered in Second Structure

In a second structure, also constructed from slate slabs and dubbed 10.042-10.049, archaeologists discovered the corpse of a young individual estimated to have been between 17 and 25 years of age at the time of his death. The body was lying in a fetal position encircled by a large set of valuable objects. These included an elephant tusk laid above the young man’s head, a set of twenty-three flint blades, and several ivory artifacts. As Signs of the Times reports the experts mentioned, “The rock crystal dagger blade appeared in the upper level of Structure 10.049 of the PP4-Montelirio sector, in association with an ivory hilt and sheath, which renders it an exceptional object in Late Prehistoric Europe… The blade is 214 mm in length, a maximum of 59 mm in width and 13 mm thick. Its morphology is not unheard of in the Iberian Peninsula, although all the samples recorded thus far were made from flint and not rock crystal.”

The crystal dagger blade. © Morgado, A., et al.

Crystal Weapons Belonged to a Few Elite Individuals

After examining the finds closely, archaeologists observed that the weapons are almost of the same shape as the flint arrowheads that were pretty common in that region during that time. However, the fact that there are not any crystal mines near the area, implies that the skillful builders of the crystal weapons possibly traveled for many miles to find the material they needed for the construction of their weapons and tools. The shortage of crystal also suggests that these weapons were destined for a select group of people. According to Signs of the Times , experts report in the study, “The more technically sophisticated items, however, were deposited in the larger megalithic structures…As such, it is reasonable to assume that although the raw material was relatively available throughout the community…only the kin groups, factions or individuals who were buried in megaliths were able to afford the added value that allowed the production of sophisticated objects such as arrow heads or dagger blades.”

In conclusion, the experts taking part in the study concerning rock crystal, confirmed Valencina's status as an exceptional location with a high concentration of exotic raw materials and rare products coming from all over Iberia.

Top image: Dagger blade from Structure 10.049 (PP4-Montelirio sector). Photograph: Miguel Angel Blanco de la Rubia.

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Archaeologists in Spain have unearthed an extremely rare set of weapons, including a long dagger blade, twenty-five arrowheads and cores used for creating the artifacts, all made of crystal! The finding was made inside megalithic tombs dating to the 3 rd millennium BC in the southwest of Spain.

An excavation of megalithic tombs in Valencina de la Concepción in Spain led to the dramatic discovery of the rare relics, which experts described as exceptional and magnificently well-preserved. The objects are estimated to be over five thousand years old (dating back to at least 3000 BC). As Signs of the Times reports , the Montelirio tholos, excavated between 2007 and 2010, is a great megalithic construction which extends nearly 44 meters (144 ft) in total, constructed out of large slabs of slate. At least 25 individuals were found within the structure. Analyses suggested that there was one male and numerous females who had drunk a poison substance. The remains of the women sit in a circle in a chamber adjacent to the bones believed to be of their chief.

The crystal weapons were discovered inside the Montelirio tholos. Copyright: ipolca (ARTURO DEL PINO RUIZ)

Incredible Crystal Arrowheads

They also found "an extraordinary set of sumptuous grave goods...the most notable of which is an unspecified number of shrouds or clothes made of tens of thousands of perforated beads and decorated with amber beads,” according to the study.

In addition to the human remains and textiles, the archaeologists found the large hoard of crystal arrowheads. The fact that they were discovered altogether indicates that they could have been a ritual offering at an altar. The arrowheads have the distinctive long lateral appendices of flint arrowheads from the region, but archaeologists noted that even greater skill must have been required to produce these unique features when using rock crystal.

A: Ontiveros arrowheads; B: Montelirio tholos arrowheads; C: Montelirio dagger blade; D: Montelirio tholos core; Montelirio knapping debris; F: Montelirio micro-blades; G: Montelirio tholos microblades. Photograph: Miguel Angel Blanco de la Rubia.

Corpse of a Young Male Discovered in Second Structure

In a second structure, also constructed from slate slabs and dubbed 10.042-10.049, archaeologists discovered the corpse of a young individual estimated to have been between 17 and 25 years of age at the time of his death. The body was lying in a fetal position encircled by a large set of valuable objects. These included an elephant tusk laid above the young man’s head, a set of twenty-three flint blades, and several ivory artifacts. As Signs of the Times reports the experts mentioned, “The rock crystal dagger blade appeared in the upper level of Structure 10.049 of the PP4-Montelirio sector, in association with an ivory hilt and sheath, which renders it an exceptional object in Late Prehistoric Europe… The blade is 214 mm in length, a maximum of 59 mm in width and 13 mm thick. Its morphology is not unheard of in the Iberian Peninsula, although all the samples recorded thus far were made from flint and not rock crystal.”

The crystal dagger blade. © Morgado, A., et al.

Crystal Weapons Belonged to a Few Elite Individuals

After examining the finds closely, archaeologists observed that the weapons are almost of the same shape as the flint arrowheads that were pretty common in that region during that time. However, the fact that there are not any crystal mines near the area, implies that the skillful builders of the crystal weapons possibly traveled for many miles to find the material they needed for the construction of their weapons and tools. The shortage of crystal also suggests that these weapons were destined for a select group of people. According to Signs of the Times , experts report in the study, “The more technically sophisticated items, however, were deposited in the larger megalithic structures…As such, it is reasonable to assume that although the raw material was relatively available throughout the community…only the kin groups, factions or individuals who were buried in megaliths were able to afford the added value that allowed the production of sophisticated objects such as arrow heads or dagger blades.”

In conclusion, the experts taking part in the study concerning rock crystal, confirmed Valencina's status as an exceptional location with a high concentration of exotic raw materials and rare products coming from all over Iberia.

Top image: Dagger blade from Structure 10.049 (PP4-Montelirio sector). Photograph: Miguel Angel Blanco de la Rubia.

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on April 18, 2017 02:00

April 17, 2017

Bones Reveal Gruesome Fate of Scottish Clan Members Who Were Smoked to Death in a Cave

Ancient Origins

More than 400 years ago, the Macleod clan massacred about 400 of the Macdonalds on the Isle of Eigg in Scotland, when the Macleods smoked them to death in a cave in which they took refuge. Now a group of tourists have found more bones of the Macdonalds clan in that cave.

The attack on the Macdonalds wiped out most of the island’s residents after a clan feud erupted over some Macleod men possibly molesting some Macdonalds girls. As many as 400 Macdonalds islanders were slain in this outbreak of clan warfare.

Entrance to the cave on Eigg where the Macdonalds clan bones were found in October. Authorities intend to rebury the bones after researchers are done with them. ( Wikimedia Commons /Christian Jones photo)

Archaeologists have dated the 53 bones, discovered in October, to roughly the same era as the massacre, which happened in or around 1577.

The feud dated back to earlier in the 16 th century, when Macleod of Dunvegan’s son was beaten and left to die in a boat, says the BBC . The legend says the boat drifted back to Skye, his home.

Another account of the clan warfare, in the Scotsman, says three young Macleod men were kicked off Eigg and tied up in their boat after they harassed some girls on Eigg. The Macleod men made it back to Dunvegan in Skye, and the clan vowed revenge.

A fleet of Macleod warriors left Skye for Eigg, but a Macdonalds watchman spotted their boats, and the islanders fled to a cave, the entrance of which was reportedly covered by a waterfall.

The historic Isle of Eigg as seen from Knoydart, Scotland. ( Wikimedia Commons /Graeme Churchard photo)

All the Macleods found was an old woman who didn’t reveal where the clan had hidden. Searches were futile, so the Macleods destroyed the Macdonalds’ home before leaving for Skye.

However, it had started to snow when the raiders saw an Eigg islander who was sent to see if the Macleods had left. The Macdonalds made landfall again and followed the Eigg man’s footprints to the cave.

When the Macleods reached the cave, they demanded the Mcdonalds surrender. The Macdonalds refused, and the Macleods smoked the Macdonalds by setting fire to turf and ferns.

Just one family escaped.

In October, police were notified that some tourists had found human remains in the cave on Eigg. Historic Environment Scotland was called to date the bones and found they dated to roughly the same era, 1430 to 1620.

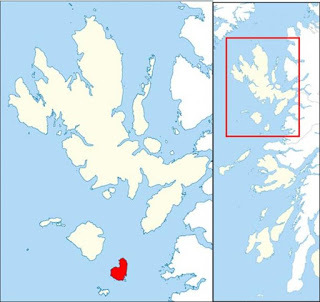

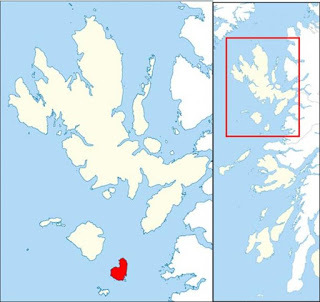

Map showing the location of Eigg near Skye and the Small Isles ( Wikimedia Commons /Howeard photo)

About 250 years after 1577, Sir Walter Scott visited the cave and found some bones, which the authorities reinterred.

In the years after, parts of skeletons were taken by souvenir seekers. Authorities intervened at the islanders’ request and buried all the bones in the Eigg cemetery.

"Some people don't like to go into the cave because of the narrow entrance and they reflect on this as the place where so many people perished,” Ms. Dressler told BBC Radio Scotland. Ms. Dressler added she hopes the discovery of the bones will spur new research into the massacre and the history surrounding it.

Kirstey Owen, a lead archaeologist with Historic Environment Scotland, told The Scotsman :

“This would of course tie in with the cave being used as the resting place of most of the population of Eigg following the massacre of 1577. There are likely to be more bones in the cave but we are treating it like a war grave and will not pro actively look for them.”

Featured image: Clan warfare in Scotland ( scotclans.com)

By Mark Miller

More than 400 years ago, the Macleod clan massacred about 400 of the Macdonalds on the Isle of Eigg in Scotland, when the Macleods smoked them to death in a cave in which they took refuge. Now a group of tourists have found more bones of the Macdonalds clan in that cave.

The attack on the Macdonalds wiped out most of the island’s residents after a clan feud erupted over some Macleod men possibly molesting some Macdonalds girls. As many as 400 Macdonalds islanders were slain in this outbreak of clan warfare.

Entrance to the cave on Eigg where the Macdonalds clan bones were found in October. Authorities intend to rebury the bones after researchers are done with them. ( Wikimedia Commons /Christian Jones photo)

Archaeologists have dated the 53 bones, discovered in October, to roughly the same era as the massacre, which happened in or around 1577.

The feud dated back to earlier in the 16 th century, when Macleod of Dunvegan’s son was beaten and left to die in a boat, says the BBC . The legend says the boat drifted back to Skye, his home.

Another account of the clan warfare, in the Scotsman, says three young Macleod men were kicked off Eigg and tied up in their boat after they harassed some girls on Eigg. The Macleod men made it back to Dunvegan in Skye, and the clan vowed revenge.

A fleet of Macleod warriors left Skye for Eigg, but a Macdonalds watchman spotted their boats, and the islanders fled to a cave, the entrance of which was reportedly covered by a waterfall.

The historic Isle of Eigg as seen from Knoydart, Scotland. ( Wikimedia Commons /Graeme Churchard photo)

All the Macleods found was an old woman who didn’t reveal where the clan had hidden. Searches were futile, so the Macleods destroyed the Macdonalds’ home before leaving for Skye.

However, it had started to snow when the raiders saw an Eigg islander who was sent to see if the Macleods had left. The Macdonalds made landfall again and followed the Eigg man’s footprints to the cave.

When the Macleods reached the cave, they demanded the Mcdonalds surrender. The Macdonalds refused, and the Macleods smoked the Macdonalds by setting fire to turf and ferns.

Just one family escaped.

In October, police were notified that some tourists had found human remains in the cave on Eigg. Historic Environment Scotland was called to date the bones and found they dated to roughly the same era, 1430 to 1620.

Map showing the location of Eigg near Skye and the Small Isles ( Wikimedia Commons /Howeard photo)

About 250 years after 1577, Sir Walter Scott visited the cave and found some bones, which the authorities reinterred.

In the years after, parts of skeletons were taken by souvenir seekers. Authorities intervened at the islanders’ request and buried all the bones in the Eigg cemetery.

"Some people don't like to go into the cave because of the narrow entrance and they reflect on this as the place where so many people perished,” Ms. Dressler told BBC Radio Scotland. Ms. Dressler added she hopes the discovery of the bones will spur new research into the massacre and the history surrounding it.

Kirstey Owen, a lead archaeologist with Historic Environment Scotland, told The Scotsman :

“This would of course tie in with the cave being used as the resting place of most of the population of Eigg following the massacre of 1577. There are likely to be more bones in the cave but we are treating it like a war grave and will not pro actively look for them.”

Featured image: Clan warfare in Scotland ( scotclans.com)

By Mark Miller

Published on April 17, 2017 02:00

April 16, 2017

1,400-Year-Old Coins are the Forgotten Remnants of a Terrifying Siege on Jerusalem

Ancient Origins

Israeli archaeologists have announced the discovery of a hoard of rare Byzantine bronze coins from a site dating back to 614 AD. The coins were discovered during excavations for the widening of the Tel Aviv- Jerusalem highway.

Persian Invasion and Siege of Jerusalem

The newly found coins are clear evidence of the Persian invasion of Jerusalem at the end of the Byzantine period. As the Persian army (supported by many Jewish rebels) marched on Jerusalem in 614 AD, Christians living in the town rushed to hide their possessions, including a hoard of the valuable coins, hoping that things would soon go back to normal.

Nine bronze coins dating to the Byzantine period were hidden in the remains of a settlement near a highway to Jerusalem. (Yoli Shwartz, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority)

Annette Landes-Naggar, Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologist and the one who announced the discovery to the press said, as The Jerusalem Post reports, “The cache was buried adjacent to an area of collapsed large stones. It appears that the owner hid them when there was danger, hoping to return to pick them up. But now we know he was unable to.” She continued, “Apparently, this was during the time of the Persian Sassanid invasion, around 614 AD,” noting that the invasion was among the factors that ended the reign of the Byzantine emperors in Israel. “Fearing the invasion, residents of the area who felt their lives were in danger buried their money against the wall of a winepress. [However], the site was abandoned and destroyed,” Landes-Naggar concluded.

The excavation area and the collapsed wall where the Byzantine coin hoard was found. (Maxim Dinstein, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority)

The Sasanian Empire – the last imperial dynasty in Iran before the rise of Islam – conquered Jerusalem after a brief siege in 614, during the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, after the Persian Shah Khosrau II appointed his general Shahrbaraz to conquer the Byzantine controlled areas of the Near East.

More than 20,000 Jewish rebels joined the war against the Byzantine Christians and the Persian army, reinforced by Jewish forces and led by Nehemiah ben Hushiel and Benjamin of Tiberias, captured Jerusalem without resistance. According to Sebeos, a 7th-century Armenian bishop and historian, the siege resulted in a total Christian death toll of 17000 and nearly 5000 prisoners, who were massacred near Mamilla reservoir per Antiochus.

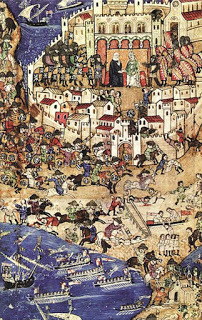

Battle between Heraclius' army and Persians under Khosrau II. Fresco by Piero della Francesca, c. 1452. (Public Domain) Experts believe the coins were hidden while there was a siege on Jerusalem in 614, during the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628.

The Coins Tell the Story of the Site

Fast-forward 1,400 years to the summer of 2016, Israeli archaeologists excavating some Byzantine ruins in the area unearthed a cache consisting of nine bronze coins dating from the Byzantine Period around 324-638 AD. The announcement was scheduled to precede the upcoming Easter holiday, which falls this year on April 16, as part of a push coordinated with the Tourism Ministry to boost Christian pilgrimage to Israel. “The coins were found adjacent to the external wall of one of the monumental buildings found at the site, and it was found among the building stones that collapsed from the wall,” Landes-Naggar told The Times of Israel.

Byzantine coins found by Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologists in 2016 and shown to the press in March 2017. (Ilan Ben Zion/Time of Israel staff)

The coins depict the faces of notable Byzantine Emperors such as Justinian I, Maurice, and Phocas, and were minted in Constantinople, Antioch, and Nicomedia. Despite not being particularly rare or of great value they “betray” the story of the site as Landes-Naggar noted,

“It’s the context of the coins that gives us the puzzle of what happened. This site is situated alongside the main road from the entrance to Jerusalem and was used by Christian pilgrims to enter the city. Settlements were developed along the road.”

Local authorities along with the Israel Pipeline Company are committed to working together to preserve the site for the public.

Top Image: The Byzantine coins found near Jerusalem have been dated to around the time of a 614 siege. Source: YOLI SCHWARTZ/IAA

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Israeli archaeologists have announced the discovery of a hoard of rare Byzantine bronze coins from a site dating back to 614 AD. The coins were discovered during excavations for the widening of the Tel Aviv- Jerusalem highway.

Persian Invasion and Siege of Jerusalem

The newly found coins are clear evidence of the Persian invasion of Jerusalem at the end of the Byzantine period. As the Persian army (supported by many Jewish rebels) marched on Jerusalem in 614 AD, Christians living in the town rushed to hide their possessions, including a hoard of the valuable coins, hoping that things would soon go back to normal.

Nine bronze coins dating to the Byzantine period were hidden in the remains of a settlement near a highway to Jerusalem. (Yoli Shwartz, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority)

Annette Landes-Naggar, Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologist and the one who announced the discovery to the press said, as The Jerusalem Post reports, “The cache was buried adjacent to an area of collapsed large stones. It appears that the owner hid them when there was danger, hoping to return to pick them up. But now we know he was unable to.” She continued, “Apparently, this was during the time of the Persian Sassanid invasion, around 614 AD,” noting that the invasion was among the factors that ended the reign of the Byzantine emperors in Israel. “Fearing the invasion, residents of the area who felt their lives were in danger buried their money against the wall of a winepress. [However], the site was abandoned and destroyed,” Landes-Naggar concluded.

The excavation area and the collapsed wall where the Byzantine coin hoard was found. (Maxim Dinstein, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority)

The Sasanian Empire – the last imperial dynasty in Iran before the rise of Islam – conquered Jerusalem after a brief siege in 614, during the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, after the Persian Shah Khosrau II appointed his general Shahrbaraz to conquer the Byzantine controlled areas of the Near East.

More than 20,000 Jewish rebels joined the war against the Byzantine Christians and the Persian army, reinforced by Jewish forces and led by Nehemiah ben Hushiel and Benjamin of Tiberias, captured Jerusalem without resistance. According to Sebeos, a 7th-century Armenian bishop and historian, the siege resulted in a total Christian death toll of 17000 and nearly 5000 prisoners, who were massacred near Mamilla reservoir per Antiochus.

Battle between Heraclius' army and Persians under Khosrau II. Fresco by Piero della Francesca, c. 1452. (Public Domain) Experts believe the coins were hidden while there was a siege on Jerusalem in 614, during the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628.

The Coins Tell the Story of the Site

Fast-forward 1,400 years to the summer of 2016, Israeli archaeologists excavating some Byzantine ruins in the area unearthed a cache consisting of nine bronze coins dating from the Byzantine Period around 324-638 AD. The announcement was scheduled to precede the upcoming Easter holiday, which falls this year on April 16, as part of a push coordinated with the Tourism Ministry to boost Christian pilgrimage to Israel. “The coins were found adjacent to the external wall of one of the monumental buildings found at the site, and it was found among the building stones that collapsed from the wall,” Landes-Naggar told The Times of Israel.

Byzantine coins found by Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologists in 2016 and shown to the press in March 2017. (Ilan Ben Zion/Time of Israel staff)

The coins depict the faces of notable Byzantine Emperors such as Justinian I, Maurice, and Phocas, and were minted in Constantinople, Antioch, and Nicomedia. Despite not being particularly rare or of great value they “betray” the story of the site as Landes-Naggar noted,

“It’s the context of the coins that gives us the puzzle of what happened. This site is situated alongside the main road from the entrance to Jerusalem and was used by Christian pilgrims to enter the city. Settlements were developed along the road.”

Local authorities along with the Israel Pipeline Company are committed to working together to preserve the site for the public.

Top Image: The Byzantine coins found near Jerusalem have been dated to around the time of a 614 siege. Source: YOLI SCHWARTZ/IAA

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on April 16, 2017 01:30

April 15, 2017

Sam’s historical recipe corner: Beef olives

History Extra

Beef olives. © Sam Nott

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates beef olives – a deliciously traditional dish enjoyed across Europe.

I’ve often heard about beef olives but in never sounded that appetising. I didn’t realise though that I’ve been eating if for years. My German grandmother would often cook rouladen, which is the same as beef olives, and it’s delicious!

I have early memories of my mum pounding meat with a rolling pin, which I’m sure was for roulade. Most parts of Europe have their equivalent recipes and one of the earliest I found was in Hannah Glasse’s 1747 book, The Art of Cookery. I based my dish on a modern version from bbcgoodfood.com.

Ingredients

400g of beef thinly sliced (any cut)

1 tbsp of dijon mustard

1 medium onion

220g celery

150g carrot

250ml red wine

600ml beef stock

2 tbsp of passata

For the stuffing:

1 small onion

3 rashers of smoked bacon

4 mushrooms

1 tsp of thyme leaves

1 clove of garlic

1 tbsp of olive oil

Method

Preheat the oven to 175˚C. Fry the onions, garlic and mushrooms until soft. Add to the raw bacon and set aside: this is your stuffing.

Place the beef on a flat surface and beat with a rolling pin or food hammer until very thin – this part is very satisfying!

Spread each beef slice with the mustard, add the stuffing and then roll the beef slice (with the stuffing inside). Secure with a cocktail stick or string. Fry on all sides until brown and place in an oven-proof dish.

Fry the remaining onion, carrot and celery in a pan for five minutes. Add passata, red wine and beef stock and stir. Pour over the beef olives and cook in the oven, with a lid on, for three hours.

Remove the beef olives from the dish and keep warm. Blend the remaining sauce until no lumps remain.

My verdict

This was really delicious, despite the fact I let it cook too long so the gravy vanished (as you can see from the photo). But with mashed potatoes and gravy, it’s a very hearty dinner.

Difficulty: 5/10

Time: 210 mins

This article was first published in the October 2014 issue of BBC History Magazine.

Beef olives. © Sam Nott

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates beef olives – a deliciously traditional dish enjoyed across Europe.

I’ve often heard about beef olives but in never sounded that appetising. I didn’t realise though that I’ve been eating if for years. My German grandmother would often cook rouladen, which is the same as beef olives, and it’s delicious!

I have early memories of my mum pounding meat with a rolling pin, which I’m sure was for roulade. Most parts of Europe have their equivalent recipes and one of the earliest I found was in Hannah Glasse’s 1747 book, The Art of Cookery. I based my dish on a modern version from bbcgoodfood.com.

Ingredients

400g of beef thinly sliced (any cut)

1 tbsp of dijon mustard

1 medium onion

220g celery

150g carrot

250ml red wine

600ml beef stock

2 tbsp of passata

For the stuffing:

1 small onion

3 rashers of smoked bacon

4 mushrooms

1 tsp of thyme leaves

1 clove of garlic

1 tbsp of olive oil

Method

Preheat the oven to 175˚C. Fry the onions, garlic and mushrooms until soft. Add to the raw bacon and set aside: this is your stuffing.

Place the beef on a flat surface and beat with a rolling pin or food hammer until very thin – this part is very satisfying!

Spread each beef slice with the mustard, add the stuffing and then roll the beef slice (with the stuffing inside). Secure with a cocktail stick or string. Fry on all sides until brown and place in an oven-proof dish.

Fry the remaining onion, carrot and celery in a pan for five minutes. Add passata, red wine and beef stock and stir. Pour over the beef olives and cook in the oven, with a lid on, for three hours.

Remove the beef olives from the dish and keep warm. Blend the remaining sauce until no lumps remain.

My verdict

This was really delicious, despite the fact I let it cook too long so the gravy vanished (as you can see from the photo). But with mashed potatoes and gravy, it’s a very hearty dinner.

Difficulty: 5/10

Time: 210 mins

This article was first published in the October 2014 issue of BBC History Magazine.

Published on April 15, 2017 02:30

April 14, 2017

Face of ‘Ordinary Poor’ Man from Medieval Cambridge Graveyard Revealed

Ancient Origins

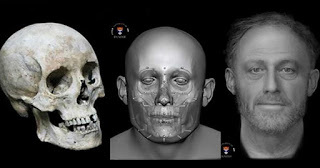

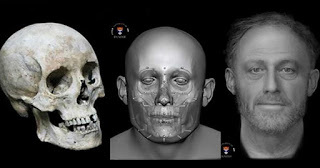

New facial reconstruction of a man buried in a medieval hospital graveyard discovered underneath a Cambridge college sheds light on how ordinary poor people lived in medieval England.

The audience of an event at this year’s Cambridge Science Festival found themselves staring into the face of a fellow Cambridge resident – one who spent the last 700 years buried beneath the venue in which they sat.

The 13th-century man, called Context 958 by researchers, was among some 400 burials for which complete skeletal remains were uncovered when one of the largest medieval hospital graveyards in Britain was discovered underneath the Old Divinity School of St John’s College, and excavated between 2010 and 2012.

Finds beneath the Old Divinity School, St John's College. Credit: Craig Cessford, Cambridge University Department of Archaeology and Anthropology

The bodies, which mostly date from a period spanning the 13th to 15th centuries, are burials from the Hospital of St John the Evangelist which stood opposite the graveyard until 1511, and from which the College takes its name. The hospital was an Augustinian charitable establishment in Cambridge dedicated to providing care to members of the public.

“Context 958 was probably an inmate of the Hospital of St John, a charitable institution which provided food and a place to live for a dozen or so indigent townspeople – some of whom were probably ill, some of whom were aged or poor and couldn't live alone,” said Professor John Robb, from the University’s Division of Archaeology.

In collaboration with Dr. Chris Rynn from the University of Dundee’s Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification, Robb and Cambridge colleagues have reconstructed the man’s face and pieced together the rudiments of his life story by analysing his bones and teeth.

Dr. Sarah Inskip examines the skull of Context 958. Image credit: Laure Bonner

The work is one of the first outputs from the Wellcome Trust-funded project ‘After the plague: health and history in medieval Cambridge’ for which Robb is principle investigator. The project is analysing the St John's burials not just statistically, but also biographically.

“Context 958 was over 40 when he died, and had quite a robust skeleton with a lot of wear and tear from a hard working life. We can't say what job specifically he did, but he was a working class person, perhaps with a specialised trade of some kind,” said Robb.

“One interesting feature is that he had a diet relatively rich in meat or fish, which may suggest that he was in a trade or job which gave him more access to these foods than a poor person might have normally had. He had fallen on hard times, perhaps through illness, limiting his ability to continue working or through not having a family network to take care of him in his poverty.”

There are hints beyond his interment in the hospital’s graveyard that Context 958’s life was one of adversity. His tooth enamel had stopped growing on two occasions during his youth, suggesting he had suffered bouts of sickness or famine early on. Archaeologists also found evidence of a blunt-force trauma on the back of his skull that had healed over prior to his death.

The face of Context 958. Image credit: Dr. Chris Rynn, University of Dundee

“He has a few unusual features, notably being buried face down which is a small irregularity for medieval burial. But, we are interested in him and in people like him more for ways in which they are not unusual, as they represent a sector of the medieval population which is quite hard to learn about: ordinary poor people,” said Robb.

“Most historical records are about well-off people and especially their financial and legal transactions – the less money and property you had, the less likely anybody was to ever write down anything about you. So skeletons like this are really our chance to learn about how the ordinary poor lived.”

Context 958 buried face-down in the cemetery of St John's. Image credit: C. Cessford

The focal point of the ‘After the Plague’ project will be the large sample of urban poor people from the graveyard of the Hospital of St John, which researchers will compare with other medieval collections to build up a picture of the lives, health and day-to-day activities of people living in Cambridge, and urban England as a whole, at this time.

“The After the Plague project is also about humanising people in the past, getting beyond the scientific facts to see them as individuals with life stories and experiences,” said Robb.

“This helps us communicate our work to the public, but it also helps us imagine them ourselves as leading complex lives like we do today. That's why putting all the data together into biographies and giving them faces is so important.”

The Old Divinity School of St John’s College was built in 1877-1879 and was recently refurbished, now housing a 180-seat lecture theatre used for College activities and public events, including last week’s Science Festival lecture given by Robb on the life of Context 958 and the research project

The refurbished Old Divinity School of St John’s College, Cambridge. (CC BY SA 3.0)

The School was formerly the burial ground of the Hospital, instituted around 1195 by the townspeople of Cambridge to care for the poor and sick in the community. Originally a small building on a patch of waste ground, the Hospital grew with Church support to be a noted place of hospitality and care for both University scholars and local people.

Top Image: The facial reconstruction of Context 958 Source: Chris Rynn, University of Dundee

The article ‘Face of ‘Ordinary Poor’ Man from Medieval Cambridge Graveyard Revealed’ was originally published on University of Cambridge and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

New facial reconstruction of a man buried in a medieval hospital graveyard discovered underneath a Cambridge college sheds light on how ordinary poor people lived in medieval England.

The audience of an event at this year’s Cambridge Science Festival found themselves staring into the face of a fellow Cambridge resident – one who spent the last 700 years buried beneath the venue in which they sat.

The 13th-century man, called Context 958 by researchers, was among some 400 burials for which complete skeletal remains were uncovered when one of the largest medieval hospital graveyards in Britain was discovered underneath the Old Divinity School of St John’s College, and excavated between 2010 and 2012.

Finds beneath the Old Divinity School, St John's College. Credit: Craig Cessford, Cambridge University Department of Archaeology and Anthropology

The bodies, which mostly date from a period spanning the 13th to 15th centuries, are burials from the Hospital of St John the Evangelist which stood opposite the graveyard until 1511, and from which the College takes its name. The hospital was an Augustinian charitable establishment in Cambridge dedicated to providing care to members of the public.

“Context 958 was probably an inmate of the Hospital of St John, a charitable institution which provided food and a place to live for a dozen or so indigent townspeople – some of whom were probably ill, some of whom were aged or poor and couldn't live alone,” said Professor John Robb, from the University’s Division of Archaeology.

In collaboration with Dr. Chris Rynn from the University of Dundee’s Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification, Robb and Cambridge colleagues have reconstructed the man’s face and pieced together the rudiments of his life story by analysing his bones and teeth.

Dr. Sarah Inskip examines the skull of Context 958. Image credit: Laure Bonner

The work is one of the first outputs from the Wellcome Trust-funded project ‘After the plague: health and history in medieval Cambridge’ for which Robb is principle investigator. The project is analysing the St John's burials not just statistically, but also biographically.

“Context 958 was over 40 when he died, and had quite a robust skeleton with a lot of wear and tear from a hard working life. We can't say what job specifically he did, but he was a working class person, perhaps with a specialised trade of some kind,” said Robb.

“One interesting feature is that he had a diet relatively rich in meat or fish, which may suggest that he was in a trade or job which gave him more access to these foods than a poor person might have normally had. He had fallen on hard times, perhaps through illness, limiting his ability to continue working or through not having a family network to take care of him in his poverty.”

There are hints beyond his interment in the hospital’s graveyard that Context 958’s life was one of adversity. His tooth enamel had stopped growing on two occasions during his youth, suggesting he had suffered bouts of sickness or famine early on. Archaeologists also found evidence of a blunt-force trauma on the back of his skull that had healed over prior to his death.

The face of Context 958. Image credit: Dr. Chris Rynn, University of Dundee

“He has a few unusual features, notably being buried face down which is a small irregularity for medieval burial. But, we are interested in him and in people like him more for ways in which they are not unusual, as they represent a sector of the medieval population which is quite hard to learn about: ordinary poor people,” said Robb.

“Most historical records are about well-off people and especially their financial and legal transactions – the less money and property you had, the less likely anybody was to ever write down anything about you. So skeletons like this are really our chance to learn about how the ordinary poor lived.”

Context 958 buried face-down in the cemetery of St John's. Image credit: C. Cessford

The focal point of the ‘After the Plague’ project will be the large sample of urban poor people from the graveyard of the Hospital of St John, which researchers will compare with other medieval collections to build up a picture of the lives, health and day-to-day activities of people living in Cambridge, and urban England as a whole, at this time.

“The After the Plague project is also about humanising people in the past, getting beyond the scientific facts to see them as individuals with life stories and experiences,” said Robb.

“This helps us communicate our work to the public, but it also helps us imagine them ourselves as leading complex lives like we do today. That's why putting all the data together into biographies and giving them faces is so important.”

The Old Divinity School of St John’s College was built in 1877-1879 and was recently refurbished, now housing a 180-seat lecture theatre used for College activities and public events, including last week’s Science Festival lecture given by Robb on the life of Context 958 and the research project

The refurbished Old Divinity School of St John’s College, Cambridge. (CC BY SA 3.0)

The School was formerly the burial ground of the Hospital, instituted around 1195 by the townspeople of Cambridge to care for the poor and sick in the community. Originally a small building on a patch of waste ground, the Hospital grew with Church support to be a noted place of hospitality and care for both University scholars and local people.

Top Image: The facial reconstruction of Context 958 Source: Chris Rynn, University of Dundee

The article ‘Face of ‘Ordinary Poor’ Man from Medieval Cambridge Graveyard Revealed’ was originally published on University of Cambridge and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Published on April 14, 2017 02:00

April 13, 2017

Have We Got a Temple, Theater, and Gate? Check! New Details Emerge on Roman Urban Planning in Central Italy

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists have discovered a magnificent ancient Roman temple the size of St Paul's Cathedral in central Italy. The discovery took place with the help of a radar device that was attached to the back of a quad bike in order to explore the hidden details of the excavation site.

Getting to Know Falerii Novi

An archaeological team of Cambridge University discovered the remains of the immense Roman temple in central Italy. The ancient temple had lines of columns on three sides covering an area of about 400 ft. (120 meters) long and 200 ft. (60 meters) wide and was unearthed many feet below Falerii Novi, an abandoned walled town in the Tiber River valley, about 50 km (31 miles) north of Rome. The small town was created by the Romans, who resettled the inhabitants of Falerii Veteres in this much less defensible position after a revolt in 241 BC. It is placed on a modest volcanic plateau and housed around 2,500 people during the 4th and 3rd centuries BC. The town also gives insight into the Roman Empire’s expanding interchange from other cultures, as Greek-style buildings were also discovered there.

Archaeological area of Falerii Novi, Italy. ( Camminare nella storia blog )

Radar Device Helped to Explore the Excavation Site

Archaeologists used a radar device attached to the back of a quad bike to explore the excavation site. Martin Millett, professor of classical archaeology at Cambridge University said as International Business Times reports , that the radar helped the team to discover in depth the layout of the town as well as its development and growth. The fascinating antiquities excavated so far are the remains of a theater, a basilica that was probably used for meetings and legal proceedings, as well as a large defensive gate. Experts suggest that some of these finds (such as the gate) will provide historians with valuable information in order to understand a little more about the urban planning in the early days of the Roman period.

Remnants of the theater. Falerii Novi, Italy. ( CC BY SA 3.0 )

The Role of the British School at Rome’s Tiber Valley Project The Roman colony of Falerii Novi was excavated during the 1990s but it was just recently that it was thoroughly examined as part of the Tiber Valley Project , which shows the urbanization of this area by the Romans. The plan produced by the British School at Rome using magnetometry reveals in great detail the subsurface archaeological features of the Republican city, as this technique can detect metals at a much greater depth than basic metal detectors, which have a standard range of about two meters (6.56 ft.).

Photo of the necropolis of "Tre ponti": the "Cavo degli Zucchi" with the Roman Amerina via (road) near Falerii, Italy. ( CC BY SA 3.0 )

According to its official website , the British School at Rome’s Tiber Valley project, studied the changing landscapes of the middle Tiber valley as the hinterland of Rome through two millennia. It drew on the vast amount of archaeological work carried out in this area to examine the impact of the growth, success and transformation of the Imperial city on the history of settlement, economy, and society in the river valley from 1000 BC to AD 1000. The project involved twelve British universities and institutions as well as many Italian scholars.

A plan of of Falerii Novi - taken from ‘Falerii: A New Survey of the Walled Area, 2002.’

Investigations conducted by the Department of Archaeology of the 'University of Southampton. (Comune di Fabrica di Roma/ CC BY SA 3.0 )

Top Image: Entrance gate to Falerii Novi. Source: Comune di Fabrica di Roma/ CC BY SA 3.0

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Archaeologists have discovered a magnificent ancient Roman temple the size of St Paul's Cathedral in central Italy. The discovery took place with the help of a radar device that was attached to the back of a quad bike in order to explore the hidden details of the excavation site.

Getting to Know Falerii Novi

An archaeological team of Cambridge University discovered the remains of the immense Roman temple in central Italy. The ancient temple had lines of columns on three sides covering an area of about 400 ft. (120 meters) long and 200 ft. (60 meters) wide and was unearthed many feet below Falerii Novi, an abandoned walled town in the Tiber River valley, about 50 km (31 miles) north of Rome. The small town was created by the Romans, who resettled the inhabitants of Falerii Veteres in this much less defensible position after a revolt in 241 BC. It is placed on a modest volcanic plateau and housed around 2,500 people during the 4th and 3rd centuries BC. The town also gives insight into the Roman Empire’s expanding interchange from other cultures, as Greek-style buildings were also discovered there.

Archaeological area of Falerii Novi, Italy. ( Camminare nella storia blog )

Radar Device Helped to Explore the Excavation Site

Archaeologists used a radar device attached to the back of a quad bike to explore the excavation site. Martin Millett, professor of classical archaeology at Cambridge University said as International Business Times reports , that the radar helped the team to discover in depth the layout of the town as well as its development and growth. The fascinating antiquities excavated so far are the remains of a theater, a basilica that was probably used for meetings and legal proceedings, as well as a large defensive gate. Experts suggest that some of these finds (such as the gate) will provide historians with valuable information in order to understand a little more about the urban planning in the early days of the Roman period.

Remnants of the theater. Falerii Novi, Italy. ( CC BY SA 3.0 )

The Role of the British School at Rome’s Tiber Valley Project The Roman colony of Falerii Novi was excavated during the 1990s but it was just recently that it was thoroughly examined as part of the Tiber Valley Project , which shows the urbanization of this area by the Romans. The plan produced by the British School at Rome using magnetometry reveals in great detail the subsurface archaeological features of the Republican city, as this technique can detect metals at a much greater depth than basic metal detectors, which have a standard range of about two meters (6.56 ft.).

Photo of the necropolis of "Tre ponti": the "Cavo degli Zucchi" with the Roman Amerina via (road) near Falerii, Italy. ( CC BY SA 3.0 )

According to its official website , the British School at Rome’s Tiber Valley project, studied the changing landscapes of the middle Tiber valley as the hinterland of Rome through two millennia. It drew on the vast amount of archaeological work carried out in this area to examine the impact of the growth, success and transformation of the Imperial city on the history of settlement, economy, and society in the river valley from 1000 BC to AD 1000. The project involved twelve British universities and institutions as well as many Italian scholars.

A plan of of Falerii Novi - taken from ‘Falerii: A New Survey of the Walled Area, 2002.’

Investigations conducted by the Department of Archaeology of the 'University of Southampton. (Comune di Fabrica di Roma/ CC BY SA 3.0 )

Top Image: Entrance gate to Falerii Novi. Source: Comune di Fabrica di Roma/ CC BY SA 3.0

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on April 13, 2017 01:00

April 12, 2017

Was Alfred the Great Just a King that was Great at Propaganda?

Ancient Origins

Stuart Brookes /The Conversation

The Last Kingdom – BBC’s historical drama set in the time of Alfred the Great’s war with the Vikings – has returned to our screens for a second series. While most attention will continue to focus on the fictional hero Uhtred, his story is played out against a political background where the main protagonist is the brooding and bookish mastermind Alfred the Great, vividly portrayed in the series by David Dawson.

But was Alfred the Great really that great? If we judge him on the basis of new findings in landscape archaeology that are radically changing our understanding of warfare in the Viking Age, it would seem not. It looks like Alfred was a good propagandist rather than a visionary military leader.

Alfred the Great's statue at Winchester. Hamo Thornycroft's bronze statue erected in 1899. (Odejea/CC BY 3.0)

The broad outline of King Alfred’s wars with the Vikings is well known. Oft defeated by the great army of the Vikings, he took refuge in a remote part of Somerset before rallying the English army in 878 and defeating the Vikings at Edington. It was not this one victory that made Alfred great, according to his biographer Asser, but the military reforms Alfred implemented after Edington. In creating a system of strongholds, a longer-serving army and new naval forces, Asser argues that Alfred put in place systems which meant that the Vikings would never win again. In doing so, he secured his legacy.

It is a well-known story, but how accurate is it? Research by a team at UCL and another at the University of Nottingham into the archaeology and place-name evidence for late Anglo-Saxon civil defence presents a slightly different picture.

Alfred the Great plots the capture of the Danish fleet. (Public Domain)

Alfred’s strongholds

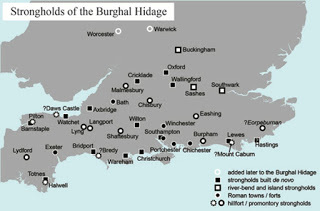

Many towns claim to have been founded by Alfred as part of his plan for defending England. This idea rests largely on a text known as the Burghal Hidage, which lists the names of 33 strongholds (in Old English burhs) across southern England and the taxes assigned to their garrisons, recorded as numbers of hides (a unit of land). According to the list, under Alfred a military machine was created whereby no fewer than 27,000 men, some 6% of the total population, were assigned to the defence and maintenance of what has been described as “fortress Wessex”.

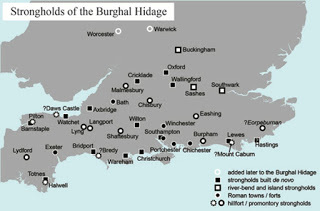

Strongholds listed in the Burghal Hidage. Author provided.

Over the past 40 years, much archaeological evidence has been gathered about the Burghal Hidage strongholds, many of which were former Roman towns or Iron Age hill forts that were reused or refurbished as Anglo-Saxon military sites. Others were new burhs raised with an innovative design that imitated the regular Roman plan.

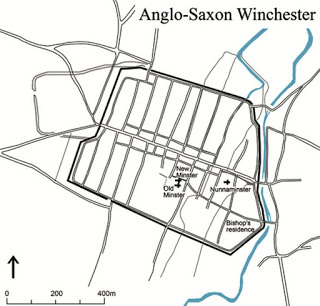

It has been argued that the latter represent an “Alfredian” vision of urban planning. But the evidence doesn’t entirely bear this out. For example, in Winchester radiocarbon and archaeomagnetic dating suggests the new urban plan was probably built around 840–80, almost certainly, therefore, before Alfred’s victory of 878 and probably before he even became king. Excavations in Worcester, by contrast, show that the distinctive “Alfredian” street plan there only came into use in the late tenth or early 11th century, around 100 years after Alfred’s death.

Archaeological evidence shows that many Bughal Hidage strongholds started as defensive sites which only later developed into towns. Sometimes this occurred at the same location, but in the case of strongholds at Iron Age hill forts, such as Burpham (Sussex), Chisbury (Wiltshire), and Pilton (Devon), more suitable locations for defended towns were sought nearby. While the general development of early emergency measures – where defence policy was determined by inaccessibility and expediency – are testimony to Alfred’s civil defence strategy, the more long-term development of purpose-built towns, around which England’s economy and administration became organised, only took place during the reigns of Alfred’s successors.

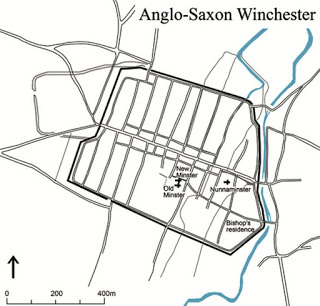

Late Anglo-Saxon Winchester showing the characteristic arrangement of streets and town defences often accredited to Alfred the Great. Author provided.

Landscapes of defence

The major strongholds listed in the Burghal Hidage have received much attention, but landscape research is also now helping to provide a fuller picture, allowing us to identify important early route-ways and river crossing-points.

Place-names containing such compounds as Old English here-pæð or fyrd-weg, both meaning “army road”, are especially important. But place-names also suggest the existence of elaborate systems of beacons and lookouts, often spaced at regular intervals, visible to each other and to known strongholds, and providing control over important route-ways. Written sources and archaeological excavation confirm that beacons were in use in the early 11th century. Landscape analysis is also helping to identify the important mustering sites, crucial to mobilisation, without which the military system would not have worked.

Aerial view of the Burghal Hidage site of Wallingford with the Thames in partial flood. Outline of the Saxon ramparts and ‘Alfredian’ street plan is clear. Image courtesy of the Environmental Agency, Author provided.

Putting all this evidence together makes it likely that Alfred the Great’s military innovations were part of a continuing development, that started in the eight century in Mercia and continued long after his death. Alfred built on existing structures, at first using what was already in place, such as hilltop defences and mustering sites of the eighth and early ninth centuries, but many of the most innovative developments in defensive organisation clearly occurred in the reign of his son, Edward the Elder (899–924). Indeed, the little closely datable evidence that can be gleaned from the major burhs, all points to a long chronology of stronghold construction.

Alfred’s defensive genius lay not in the creation of burhs, then, but in the way he adapted earlier strategies to suit the drastically altered military demands of the Viking age. His first steps towards a reliable and more constant system of military service ensured the continuous availability of troops. But the glories afforded him in popular imagination as the architect of “fortress Wessex” no longer, it seems, stand.

St. Alfred the Great. (CC BY SA 3.0)

Top Image: Alfred the Great. (19th century). Source: Public Domain

The article, originally titled ‘New research indicates that Alfred the Great probably wasn’t that great’ by Stuart Brookes was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Stuart Brookes /The Conversation

The Last Kingdom – BBC’s historical drama set in the time of Alfred the Great’s war with the Vikings – has returned to our screens for a second series. While most attention will continue to focus on the fictional hero Uhtred, his story is played out against a political background where the main protagonist is the brooding and bookish mastermind Alfred the Great, vividly portrayed in the series by David Dawson.

But was Alfred the Great really that great? If we judge him on the basis of new findings in landscape archaeology that are radically changing our understanding of warfare in the Viking Age, it would seem not. It looks like Alfred was a good propagandist rather than a visionary military leader.

Alfred the Great's statue at Winchester. Hamo Thornycroft's bronze statue erected in 1899. (Odejea/CC BY 3.0)

The broad outline of King Alfred’s wars with the Vikings is well known. Oft defeated by the great army of the Vikings, he took refuge in a remote part of Somerset before rallying the English army in 878 and defeating the Vikings at Edington. It was not this one victory that made Alfred great, according to his biographer Asser, but the military reforms Alfred implemented after Edington. In creating a system of strongholds, a longer-serving army and new naval forces, Asser argues that Alfred put in place systems which meant that the Vikings would never win again. In doing so, he secured his legacy.

It is a well-known story, but how accurate is it? Research by a team at UCL and another at the University of Nottingham into the archaeology and place-name evidence for late Anglo-Saxon civil defence presents a slightly different picture.

Alfred the Great plots the capture of the Danish fleet. (Public Domain)

Alfred’s strongholds

Many towns claim to have been founded by Alfred as part of his plan for defending England. This idea rests largely on a text known as the Burghal Hidage, which lists the names of 33 strongholds (in Old English burhs) across southern England and the taxes assigned to their garrisons, recorded as numbers of hides (a unit of land). According to the list, under Alfred a military machine was created whereby no fewer than 27,000 men, some 6% of the total population, were assigned to the defence and maintenance of what has been described as “fortress Wessex”.

Strongholds listed in the Burghal Hidage. Author provided.

Over the past 40 years, much archaeological evidence has been gathered about the Burghal Hidage strongholds, many of which were former Roman towns or Iron Age hill forts that were reused or refurbished as Anglo-Saxon military sites. Others were new burhs raised with an innovative design that imitated the regular Roman plan.

It has been argued that the latter represent an “Alfredian” vision of urban planning. But the evidence doesn’t entirely bear this out. For example, in Winchester radiocarbon and archaeomagnetic dating suggests the new urban plan was probably built around 840–80, almost certainly, therefore, before Alfred’s victory of 878 and probably before he even became king. Excavations in Worcester, by contrast, show that the distinctive “Alfredian” street plan there only came into use in the late tenth or early 11th century, around 100 years after Alfred’s death.

Archaeological evidence shows that many Bughal Hidage strongholds started as defensive sites which only later developed into towns. Sometimes this occurred at the same location, but in the case of strongholds at Iron Age hill forts, such as Burpham (Sussex), Chisbury (Wiltshire), and Pilton (Devon), more suitable locations for defended towns were sought nearby. While the general development of early emergency measures – where defence policy was determined by inaccessibility and expediency – are testimony to Alfred’s civil defence strategy, the more long-term development of purpose-built towns, around which England’s economy and administration became organised, only took place during the reigns of Alfred’s successors.

Late Anglo-Saxon Winchester showing the characteristic arrangement of streets and town defences often accredited to Alfred the Great. Author provided.

Landscapes of defence

The major strongholds listed in the Burghal Hidage have received much attention, but landscape research is also now helping to provide a fuller picture, allowing us to identify important early route-ways and river crossing-points.

Place-names containing such compounds as Old English here-pæð or fyrd-weg, both meaning “army road”, are especially important. But place-names also suggest the existence of elaborate systems of beacons and lookouts, often spaced at regular intervals, visible to each other and to known strongholds, and providing control over important route-ways. Written sources and archaeological excavation confirm that beacons were in use in the early 11th century. Landscape analysis is also helping to identify the important mustering sites, crucial to mobilisation, without which the military system would not have worked.

Aerial view of the Burghal Hidage site of Wallingford with the Thames in partial flood. Outline of the Saxon ramparts and ‘Alfredian’ street plan is clear. Image courtesy of the Environmental Agency, Author provided.

Putting all this evidence together makes it likely that Alfred the Great’s military innovations were part of a continuing development, that started in the eight century in Mercia and continued long after his death. Alfred built on existing structures, at first using what was already in place, such as hilltop defences and mustering sites of the eighth and early ninth centuries, but many of the most innovative developments in defensive organisation clearly occurred in the reign of his son, Edward the Elder (899–924). Indeed, the little closely datable evidence that can be gleaned from the major burhs, all points to a long chronology of stronghold construction.

Alfred’s defensive genius lay not in the creation of burhs, then, but in the way he adapted earlier strategies to suit the drastically altered military demands of the Viking age. His first steps towards a reliable and more constant system of military service ensured the continuous availability of troops. But the glories afforded him in popular imagination as the architect of “fortress Wessex” no longer, it seems, stand.

St. Alfred the Great. (CC BY SA 3.0)

Top Image: Alfred the Great. (19th century). Source: Public Domain

The article, originally titled ‘New research indicates that Alfred the Great probably wasn’t that great’ by Stuart Brookes was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Published on April 12, 2017 01:30

April 11, 2017

Sam’s historical recipe corner: A delicate chewit

History Extra

© Sam Nott

© Sam Nott

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates a delicate chewit - a meat and fruit pie enjoyed in the 16th century.

Britain loves pies, and recipes for them can be found in cookbooks going back centuries. This month I’ve chosen a 16th-century pie called a chewit that mixes sweet and savoury flavours – a combination that was popular in the Tudor era. Recipes from that time often refer to coffins – robust pastry designed more to contain the filling than to be eaten. My version, including measurements, is based on this 16th-century recipe:

Parboyle a piece of a Legge of Veal, and being cold, mince it with Beefe Suit, and Marrow, and an Apple or a couple of Wardens: when you haue minst it fine, put to a few parboyld Currins, sixe Dates minst, a piece of a preserued Orenge pill minst, Marrow cut in little square pieces. Season all this with Pepper, Salt, Nutmeg, and a little Sugar: then put it into your Coffins, and so bake it. Before you close your Pye, sprinckle on a little Rosewater, and when they are baked shaue on a little Sugar, and so serue it to the Table.

Ingredients

Pastry:

• 400g flour

• 1 tsp salt

• 200g butter

• 1 egg yolk

• Iced water

Filling:

• 500g minced beef

• 50g sultanas

• 6 dates

• Zest from half an orange

• 2 medium-sized pears, chopped

• 100g suet

• 1 tsp nutmeg

• Salt and pepper

• Rose water (sprinkle)

• Sugar (sprinkle)

Method

Pastry:

Sift the flour and salt into a basin. Cut the butter into small chunks and rub it into the flour until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs. Make a well in the centre. Add the egg yolk and 5 tbsp of iced water. Roll the pastry into a ball, wrap in cling film and leave in the fridge for 30 minutes.

Filling:

Roll out the pastry and line a pie tin, leaving enough for the lid of the pie. Lightly fry the minced beef, then add the suet, fruit and seasoning. Pack tightly into the pie case and sprinkle a small amount of rose water on the top of the filling before adding the pie top. Sprinkle sugar on the pastry and cook for an hour in an oven preheated to 200˚C.

Team verdict: “Delicious and moist” “Mmmmm – fruity!”

Difficulty: 4/10

Time: 1 hour preparation, 1 hour cooking

This article was first published in the December 2015 issue of BBC History Magazine

© Sam Nott

© Sam Nott In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates a delicate chewit - a meat and fruit pie enjoyed in the 16th century.

Britain loves pies, and recipes for them can be found in cookbooks going back centuries. This month I’ve chosen a 16th-century pie called a chewit that mixes sweet and savoury flavours – a combination that was popular in the Tudor era. Recipes from that time often refer to coffins – robust pastry designed more to contain the filling than to be eaten. My version, including measurements, is based on this 16th-century recipe:

Parboyle a piece of a Legge of Veal, and being cold, mince it with Beefe Suit, and Marrow, and an Apple or a couple of Wardens: when you haue minst it fine, put to a few parboyld Currins, sixe Dates minst, a piece of a preserued Orenge pill minst, Marrow cut in little square pieces. Season all this with Pepper, Salt, Nutmeg, and a little Sugar: then put it into your Coffins, and so bake it. Before you close your Pye, sprinckle on a little Rosewater, and when they are baked shaue on a little Sugar, and so serue it to the Table.

Ingredients

Pastry:

• 400g flour

• 1 tsp salt

• 200g butter

• 1 egg yolk

• Iced water

Filling:

• 500g minced beef

• 50g sultanas

• 6 dates

• Zest from half an orange

• 2 medium-sized pears, chopped

• 100g suet

• 1 tsp nutmeg

• Salt and pepper

• Rose water (sprinkle)

• Sugar (sprinkle)

Method

Pastry:

Sift the flour and salt into a basin. Cut the butter into small chunks and rub it into the flour until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs. Make a well in the centre. Add the egg yolk and 5 tbsp of iced water. Roll the pastry into a ball, wrap in cling film and leave in the fridge for 30 minutes.

Filling:

Roll out the pastry and line a pie tin, leaving enough for the lid of the pie. Lightly fry the minced beef, then add the suet, fruit and seasoning. Pack tightly into the pie case and sprinkle a small amount of rose water on the top of the filling before adding the pie top. Sprinkle sugar on the pastry and cook for an hour in an oven preheated to 200˚C.

Team verdict: “Delicious and moist” “Mmmmm – fruity!”

Difficulty: 4/10

Time: 1 hour preparation, 1 hour cooking

This article was first published in the December 2015 issue of BBC History Magazine

Published on April 11, 2017 01:30

April 10, 2017

Where Did It Begin? Gathering Place for the Battle of Salamis is Found

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists think they have found where the Greek fleet gathered before the 480 BC Battle of Salamis, fought between Greeks and Persians in the bay of Ampelakia. The team studying the area found antiquities in the water and did a survey using modern technology to nail the site down.

The underwater archaeology team studied three sides of bay on the east coast of Salamis Island in November and December. The focus of the study, which researchers are conducting in a three-year program, was in the western part of the bay, the Greek Reporter says.

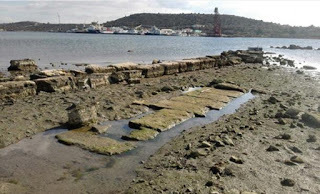

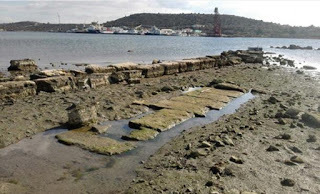

Ruins of ancient classical city and the port of Salamis (5th to 2nd BC) Ampelakia. (CC BY SA 4.0)

The Greek Ministry of Culture issued a statement about the research that states:

“This is the commercial and possibly military port of the Classical and Hellenistic city-municipality of Salamis, the largest and closest to the Athenian state, after the three ports of Piraeus (Kantharos, Zea, Mounichia). It is also the place where at least part of the united Greek fleet gathered on the eve of the great battle of 480 BC, which is adjacent to the most important monuments of Victory: the Polyandreion (tomb) of Salamis and the trophy on Kynosoura. References to the ancient port of Salamis responded to works geographer Skylakos (4th c. BC), the geographer Stravonas (1st Century BC-1st Century AD) and Pausanias (2nd century AD).”

A Ministry of Culture statement on the findings also says the researchers discovered ancient structures on three sides of the bay—south, north, and west. These structures are sometimes seen as the water level changes. In February, the ebb reduces the depth of the waters by half a meter (about 1.6 ft.)

An archaeologist excavates a ship-shed at Mounichia Harbor, another body of water involved in the battle of Salamis, on a very rare day of good visibility in the waters. (University of Copenhagen)

The team saw remnants of fortifications, buildings, and harbor structures as they did aerial photography and photogrammetric processing. They also studied topographical and architectural features of visible structures, thus creating the first underwater archaeological map of the harbor. The map will help in future studies of the port.

Also, the geoarchaeological and geophysical research being done by the team, which is from the University of Patras, resulted in fine digital surveys that are expected to aid in the reconstruction of the paleography of the site.

Some of the architectural features in the bay of Ampelakia near the ancient ruins of the port town of Salamis. (Chr. Marabou)

There is another ancient Greek location sharing the name of this notable island. As Ancient Origins’ April Holloway reported in 2015, Salamis on the island of Cyprus was a large city in ancient times. It served many dominant groups over the course of its history, including Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, and Romans. According to Homeric legend, Salamis was founded by archer Teucer from the Trojan War. Although long abandoned, the city of Salamis serves as a reminder of the great cities that existed in antiquity, and an indicator of how far we have come in the past few centuries.

Bronze statue depicting legendary archer, Teucer, the legendary founder of Salamis. (CC BY SA 2.5)

Ancient Origins also reported in 2016 that in 493 BC, Greek general and politician Themistocles urged Athens to build a naval force of 200 triremes as a bulwark against the Persians, who’d attacked and been repelled on land at the Battle of Marathon. Within three years, Persia unsuccessfully attacked Greece again, including by sea this time. So instead of the West being influenced by Persia, it remained under the sway of Greek religion and culture, including the democratic style of government that is purportedly the epitome of civilization.

Top image: ‘Battle of Salamis’ (1868) by Wilhem von Kaulbach. Source: Public Domain

By Mark Miller

Archaeologists think they have found where the Greek fleet gathered before the 480 BC Battle of Salamis, fought between Greeks and Persians in the bay of Ampelakia. The team studying the area found antiquities in the water and did a survey using modern technology to nail the site down.

The underwater archaeology team studied three sides of bay on the east coast of Salamis Island in November and December. The focus of the study, which researchers are conducting in a three-year program, was in the western part of the bay, the Greek Reporter says.

Ruins of ancient classical city and the port of Salamis (5th to 2nd BC) Ampelakia. (CC BY SA 4.0)

The Greek Ministry of Culture issued a statement about the research that states:

“This is the commercial and possibly military port of the Classical and Hellenistic city-municipality of Salamis, the largest and closest to the Athenian state, after the three ports of Piraeus (Kantharos, Zea, Mounichia). It is also the place where at least part of the united Greek fleet gathered on the eve of the great battle of 480 BC, which is adjacent to the most important monuments of Victory: the Polyandreion (tomb) of Salamis and the trophy on Kynosoura. References to the ancient port of Salamis responded to works geographer Skylakos (4th c. BC), the geographer Stravonas (1st Century BC-1st Century AD) and Pausanias (2nd century AD).”

A Ministry of Culture statement on the findings also says the researchers discovered ancient structures on three sides of the bay—south, north, and west. These structures are sometimes seen as the water level changes. In February, the ebb reduces the depth of the waters by half a meter (about 1.6 ft.)

An archaeologist excavates a ship-shed at Mounichia Harbor, another body of water involved in the battle of Salamis, on a very rare day of good visibility in the waters. (University of Copenhagen)

The team saw remnants of fortifications, buildings, and harbor structures as they did aerial photography and photogrammetric processing. They also studied topographical and architectural features of visible structures, thus creating the first underwater archaeological map of the harbor. The map will help in future studies of the port.

Also, the geoarchaeological and geophysical research being done by the team, which is from the University of Patras, resulted in fine digital surveys that are expected to aid in the reconstruction of the paleography of the site.

Some of the architectural features in the bay of Ampelakia near the ancient ruins of the port town of Salamis. (Chr. Marabou)

There is another ancient Greek location sharing the name of this notable island. As Ancient Origins’ April Holloway reported in 2015, Salamis on the island of Cyprus was a large city in ancient times. It served many dominant groups over the course of its history, including Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, and Romans. According to Homeric legend, Salamis was founded by archer Teucer from the Trojan War. Although long abandoned, the city of Salamis serves as a reminder of the great cities that existed in antiquity, and an indicator of how far we have come in the past few centuries.

Bronze statue depicting legendary archer, Teucer, the legendary founder of Salamis. (CC BY SA 2.5)

Ancient Origins also reported in 2016 that in 493 BC, Greek general and politician Themistocles urged Athens to build a naval force of 200 triremes as a bulwark against the Persians, who’d attacked and been repelled on land at the Battle of Marathon. Within three years, Persia unsuccessfully attacked Greece again, including by sea this time. So instead of the West being influenced by Persia, it remained under the sway of Greek religion and culture, including the democratic style of government that is purportedly the epitome of civilization.

Top image: ‘Battle of Salamis’ (1868) by Wilhem von Kaulbach. Source: Public Domain

By Mark Miller

Published on April 10, 2017 01:30

April 9, 2017

Crusader Shipwreck Yields Coins and Other Artifacts from the Final Years of a Holy Land Fortress

Ancient Origins

Marine archaeologists have discovered some intriguing artifacts in the wreck of a ship belonging to the Crusaders in Acre, Israel. It dates to the time of the valiant last stand by the few remaining knights and mercenaries who died heroically defending the walls of the last powerful Christian fortress in the Holy Land.

The Geopolitical Significance of Acre in the Past

The Crusader kingdom in the Holy Land began to collapse in the later part of the 13th century. The fall of Jaffa and Antioch in 1268 to the Muslims forced Louis IX to undertake the Eighth Crusade (1270), which was cut short by his death in Tunisia. The Ninth Crusade (1271–72), was led by Prince Edward, who landed at Acre but retired after concluding a truce. In 1289, Tripoli fell to the Muslims, leaving Acre as the only remaining Christian fortress in the Holy Land. Capturing Acre was extremely crucial from a geopolitical and strategical point of view for the Mamluks, as Western European forces had used the site for a very long time as a landing point for European soldiers, knights, and horses, as well as an international commercial spot for the export of sugar, spices, glass, and textiles back to Europe.

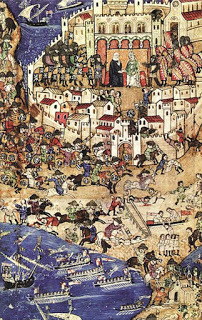

The fall of Tripoli to the Mamluks, April 1289. This was a battle towards the end of the Crusades and preceded the siege of Acre. (Public Domain)

During the spring of 1291, the Egyptian sultan Al-Ashraf Khalil with his immense forces (over 100,000 cavalry and foot soldiers) attacked the fortress in Acre and for six weeks the siege dragged on - until the Mamluks took the outer wall. The Military Orders drove back the Mamluks temporarily, but three days later the inner wall was breached. King Henry escaped, but the bulk of the defenders and most of the citizens perished in the fighting or were sold into slavery. The surviving knights fell back to their fortress, resisting for ten days, until the Mamluks broke through, killing them. Western Christianity would never again establish a firm foothold in the Middle East.

The Siege of Acre. The Hospitalier Master Mathieu de Clermont defending the walls in 1291. (Public Domain)

The Discovery of the Wreck at Acre