MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 64

March 9, 2017

Sam’s historical recipe corner: Torta Margherita

History Extra

A delicious gluten and dairy-free cake with only three ingredients. (Credit: Sam Nott)

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates Torta Margherita, a 19th-century cake from Italy that is both gluten and dairy-free.

This recipe comes from Pellegrino Artusi’s 1891 cookbook La Scienza in Cucina e l’Arte di Mangiare Bene (The Science of Cooking and the Art of Fine Dining), and is a cake that has been enjoyed in many Italian households.

Artusi’s introduction to his cookbook gives an insight into the origins of the cake. He originally made it for a friend of his, Antonio Mattei, who took the recipe and, after making a few changes, sold it in his restaurant.

The cake was such a success that it soon became the norm to finish a meal with Torta Margherita. The moral of the story, according to Artusi, is that if you grab opportunities when they arise (as Mattei did) fortune will favour you above someone who merely sits back and waits.

Ingredients

120g of potato starch,

sifted 120g of fine white sugar (caster sugar)

4 eggs

Juice or zest of a lemon (optional)

Butter and baking paper (to line the baking tin)

Method

Separate the yolks from the whites and beat the yolks together with the sugar until pale and creamy. Add the lemon (optional) and the potato starch and beat.

In a separate bowl, whisk the egg whites until stiff peaks form, then delicately fold the whites through the batter. Place the mixture into a round cake tin (buttered and lined with baking paper). Bake at a moderate heat for about an hour or until golden on top and firm to the touch.

Difficulty: 2/10

Time: 60 minutes

Verdict: When I found this recipe I was intrigued: a gluten and dairy-free cake that tastes nice? And with only three ingredients? But the picture in the recipe book looked very enticing so I gave it a try.

And I’m glad I did! I ended up making several of these as they were so delicious; friends and family devoured them all. The cake is incredibly light, goes well with tea or coffee, and takes just an hour to make.

Recipe courtesy of Emiko Davies.

A delicious gluten and dairy-free cake with only three ingredients. (Credit: Sam Nott)

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates Torta Margherita, a 19th-century cake from Italy that is both gluten and dairy-free.

This recipe comes from Pellegrino Artusi’s 1891 cookbook La Scienza in Cucina e l’Arte di Mangiare Bene (The Science of Cooking and the Art of Fine Dining), and is a cake that has been enjoyed in many Italian households.

Artusi’s introduction to his cookbook gives an insight into the origins of the cake. He originally made it for a friend of his, Antonio Mattei, who took the recipe and, after making a few changes, sold it in his restaurant.

The cake was such a success that it soon became the norm to finish a meal with Torta Margherita. The moral of the story, according to Artusi, is that if you grab opportunities when they arise (as Mattei did) fortune will favour you above someone who merely sits back and waits.

Ingredients

120g of potato starch,

sifted 120g of fine white sugar (caster sugar)

4 eggs

Juice or zest of a lemon (optional)

Butter and baking paper (to line the baking tin)

Method

Separate the yolks from the whites and beat the yolks together with the sugar until pale and creamy. Add the lemon (optional) and the potato starch and beat.

In a separate bowl, whisk the egg whites until stiff peaks form, then delicately fold the whites through the batter. Place the mixture into a round cake tin (buttered and lined with baking paper). Bake at a moderate heat for about an hour or until golden on top and firm to the touch.

Difficulty: 2/10

Time: 60 minutes

Verdict: When I found this recipe I was intrigued: a gluten and dairy-free cake that tastes nice? And with only three ingredients? But the picture in the recipe book looked very enticing so I gave it a try.

And I’m glad I did! I ended up making several of these as they were so delicious; friends and family devoured them all. The cake is incredibly light, goes well with tea or coffee, and takes just an hour to make.

Recipe courtesy of Emiko Davies.

Published on March 09, 2017 02:00

March 8, 2017

An Ancient Greek sense of humour

History Extra

Were the ancient Greeks funny? It’s a question not often asked. When thought about, most people will turn to the ‘comedies’ put on at different religio-theatrical festivals across ancient Greece, most notably in Athens. The majority surviving for us today are by Aristophanes, writing across the divide of the 5th and 4th centuries BC, but some also survive by Menander writing later in the 4th century BC.

Aristophanes makes political jokes, imitates the politicians of the day (who without doubt were often sitting in the audience) and uses exaggeration and caricature to pass comment on the social and political well being of the city. The caricature of ‘Demos’ – the people – is, for example, an old man who is easily hood-winked. What we have of Menander on the other hand seems to reveal a comic writer much more concerned with representing a kitchen-sink-drama style portrayal of domestic hilarity.

But did the Ancient Greeks tell jokes? Yes they did. Sources tell of ‘joke-groups’ who met to trade and test their wit, like the group of 60 who met in the Temple of Heracles in Athens in the 4th century BC, and whom even Philip of Macedon paid to send him a collection of their best.

A much later text that has survived down to us is the ‘Philogelos’ – 'the laughter lover' – compiled by Hierocles and Philagrius (of which almost nothing is known) in perhaps the AD 4th century. Here the compilation reveals something of the nature of Greek jokes – and they are surprisingly like are own.

There are those that focus on the ‘buffon’, the idiot, who does something stupid and funny, which have a remarkable parallel, as some scholars have already pointed out, with the ‘English, Scottish and Irish’ jokes still told in Britain today in which the Irish person always does something ridiculous (and which, I’d wager, every country has a version, which simply varies the nationalities).

One ancient Greek idiot joke reads: “An idiot, wanting to go to sleep but not having a pillow, told his slave to set an earthen jar under his head. The slave said that the jug was hard. The idiot told him to fill it with feathers.”

There are also the comic insults, listed so as to be used in instant one-line put downs – “You don’t have a face, but a fireplace” reads one. But my particular favourites are the ‘doctor’ jokes: “A person went to a doctor and said “doctor, whenever I get up from sleeping, I’m groggy for a half an hour afterwards and only after that am I all right” To which the doctor replied: “Get up half an hour later.”

Reprinted from Neos Kosmos www.neoskosmos.com

Were the ancient Greeks funny? It’s a question not often asked. When thought about, most people will turn to the ‘comedies’ put on at different religio-theatrical festivals across ancient Greece, most notably in Athens. The majority surviving for us today are by Aristophanes, writing across the divide of the 5th and 4th centuries BC, but some also survive by Menander writing later in the 4th century BC.

Aristophanes makes political jokes, imitates the politicians of the day (who without doubt were often sitting in the audience) and uses exaggeration and caricature to pass comment on the social and political well being of the city. The caricature of ‘Demos’ – the people – is, for example, an old man who is easily hood-winked. What we have of Menander on the other hand seems to reveal a comic writer much more concerned with representing a kitchen-sink-drama style portrayal of domestic hilarity.

But did the Ancient Greeks tell jokes? Yes they did. Sources tell of ‘joke-groups’ who met to trade and test their wit, like the group of 60 who met in the Temple of Heracles in Athens in the 4th century BC, and whom even Philip of Macedon paid to send him a collection of their best.

A much later text that has survived down to us is the ‘Philogelos’ – 'the laughter lover' – compiled by Hierocles and Philagrius (of which almost nothing is known) in perhaps the AD 4th century. Here the compilation reveals something of the nature of Greek jokes – and they are surprisingly like are own.

There are those that focus on the ‘buffon’, the idiot, who does something stupid and funny, which have a remarkable parallel, as some scholars have already pointed out, with the ‘English, Scottish and Irish’ jokes still told in Britain today in which the Irish person always does something ridiculous (and which, I’d wager, every country has a version, which simply varies the nationalities).

One ancient Greek idiot joke reads: “An idiot, wanting to go to sleep but not having a pillow, told his slave to set an earthen jar under his head. The slave said that the jug was hard. The idiot told him to fill it with feathers.”

There are also the comic insults, listed so as to be used in instant one-line put downs – “You don’t have a face, but a fireplace” reads one. But my particular favourites are the ‘doctor’ jokes: “A person went to a doctor and said “doctor, whenever I get up from sleeping, I’m groggy for a half an hour afterwards and only after that am I all right” To which the doctor replied: “Get up half an hour later.”

Reprinted from Neos Kosmos www.neoskosmos.com

Published on March 08, 2017 02:00

March 7, 2017

Michael Wood on… Alexander the Great

History Extra

On our summer holidays in Greece at the end of August, I started getting excited messages from Greek friends about an amazing discovery at Amphipolis in the north of the country. A Macedonian tomb, the largest yet found: a mound 160m across surrounded by a circular wall, with a series of underground chambers, of which three so far have been entered. Inside are stone sphinxes and caryatids (sculpted female figures).

Stone fragments in the entrance may be part of the famous Lion of Amphipolis which today greets the visitor as you enter the town; very likely the lion once surmounted the burial mound. The date of this extraordinary monument is still uncertain, but the excavators think it is from the late fourth century BC – just after Alexander the Great’s death in Babylon.

The find is front-page news in Greece. The villagers (sensing its potential to draw tourists!) want the tomb to be that of Alexander himself. However, he was certainly buried in Alexandria. But could it still have been originally planned for him? All will be revealed, we hope, when the excavators open the tomb chamber; but the find has focused attention again on one of the great figures in history, and one who has long fascinated me.

Back in the early eighties I was lucky enough to experience the incredible thrill of climbing down by ladder through a hole in the roof of the tomb of Alexander’s father, Philip, in the northern Greek town of Vergina with the excavator, Manolis Andronikos; the marble doors to the underworld still closed. In the late nineties I followed Alexander’s route from Greece to India on the ground, and will never forget the excitement of tracking him across the Hindu Kush to Alexandria the Farthermost (Khujand in Tajikistan), and through the forbidding Makran desert in southern Pakistan.

The Greek adventure in Asia is an astounding tale: people from a small land on the edge of civilisation who conquered half the known world. After Alexander, they went even further. The ‘King and Saviour’ Menander subdued the Ganges valley and became a Buddhist; his name is given on ancient maps to the Arakan mountains, which divide Bengal and Burma. It’s an incredible story of conquest, daring and cruelty, only matched in history perhaps by the conquistadors.

As for Alexander himself, the debate goes on. British imperialists idealised him as a unifier, yet he stands accused of war crimes. But as so often in history, war drove change. The expedition accelerated the dissemination of Greek culture across west Asia in a great cross-fertilisation. For a thousand years Greek was a lingua franca in a Hellenised near east. Even the Qur’an tells the tale of the ‘Two Horned One’ – thought to be Alexander – to whom Allah gave dominion over the Earth.

Going east, the theorem of Pythagoras reached China within decades of Alexander’s death, and the terracotta army and the first monumental bronzes of the Chin emperor are now thought to have been inspired by Hellenistic models, perhaps seen in central Asia.

So amazing vistas open up. The tale has been transformed out of all recognition these last few decades, through archaeology, cuneiform texts, the Vergina tombs and the Derveni papyrus with its insights into Greek mystical cults. And now, unexpectedly, is a spectacular new find from Macedonia itself.

So who lies in the tomb? One of Alexander’s successors? Or one of his family? Could it be a war memorial? (Is it a coincidence that it was at Amphipolis that Alexander’s army assembled before embarking on the war in Asia?) Or could it perhaps commemorate Alexander’s general Laomedon, who went to India but may have ended his days in Amphipolis?

So many questions! In the meantime we all wait with great excitement. When I heard the news on holiday in Greece, my mind went back to the old folktale still told by fishermen on the little Cycladic island where we go each summer. In the midst of the storm a mermaid appears in the raging waters and calls out: ‘Where is Great Alexander?’ To save your life you must give the right answer, or she will drag you into the depths. The answer is this: ‘Great Alexander still lives and rules!’

Michael Wood is professor of public history at the University of Manchester. His most recent TV series was King Alfred and the Anglo-Saxons.

On our summer holidays in Greece at the end of August, I started getting excited messages from Greek friends about an amazing discovery at Amphipolis in the north of the country. A Macedonian tomb, the largest yet found: a mound 160m across surrounded by a circular wall, with a series of underground chambers, of which three so far have been entered. Inside are stone sphinxes and caryatids (sculpted female figures).

Stone fragments in the entrance may be part of the famous Lion of Amphipolis which today greets the visitor as you enter the town; very likely the lion once surmounted the burial mound. The date of this extraordinary monument is still uncertain, but the excavators think it is from the late fourth century BC – just after Alexander the Great’s death in Babylon.

The find is front-page news in Greece. The villagers (sensing its potential to draw tourists!) want the tomb to be that of Alexander himself. However, he was certainly buried in Alexandria. But could it still have been originally planned for him? All will be revealed, we hope, when the excavators open the tomb chamber; but the find has focused attention again on one of the great figures in history, and one who has long fascinated me.

Back in the early eighties I was lucky enough to experience the incredible thrill of climbing down by ladder through a hole in the roof of the tomb of Alexander’s father, Philip, in the northern Greek town of Vergina with the excavator, Manolis Andronikos; the marble doors to the underworld still closed. In the late nineties I followed Alexander’s route from Greece to India on the ground, and will never forget the excitement of tracking him across the Hindu Kush to Alexandria the Farthermost (Khujand in Tajikistan), and through the forbidding Makran desert in southern Pakistan.

The Greek adventure in Asia is an astounding tale: people from a small land on the edge of civilisation who conquered half the known world. After Alexander, they went even further. The ‘King and Saviour’ Menander subdued the Ganges valley and became a Buddhist; his name is given on ancient maps to the Arakan mountains, which divide Bengal and Burma. It’s an incredible story of conquest, daring and cruelty, only matched in history perhaps by the conquistadors.

As for Alexander himself, the debate goes on. British imperialists idealised him as a unifier, yet he stands accused of war crimes. But as so often in history, war drove change. The expedition accelerated the dissemination of Greek culture across west Asia in a great cross-fertilisation. For a thousand years Greek was a lingua franca in a Hellenised near east. Even the Qur’an tells the tale of the ‘Two Horned One’ – thought to be Alexander – to whom Allah gave dominion over the Earth.

Going east, the theorem of Pythagoras reached China within decades of Alexander’s death, and the terracotta army and the first monumental bronzes of the Chin emperor are now thought to have been inspired by Hellenistic models, perhaps seen in central Asia.

So amazing vistas open up. The tale has been transformed out of all recognition these last few decades, through archaeology, cuneiform texts, the Vergina tombs and the Derveni papyrus with its insights into Greek mystical cults. And now, unexpectedly, is a spectacular new find from Macedonia itself.

So who lies in the tomb? One of Alexander’s successors? Or one of his family? Could it be a war memorial? (Is it a coincidence that it was at Amphipolis that Alexander’s army assembled before embarking on the war in Asia?) Or could it perhaps commemorate Alexander’s general Laomedon, who went to India but may have ended his days in Amphipolis?

So many questions! In the meantime we all wait with great excitement. When I heard the news on holiday in Greece, my mind went back to the old folktale still told by fishermen on the little Cycladic island where we go each summer. In the midst of the storm a mermaid appears in the raging waters and calls out: ‘Where is Great Alexander?’ To save your life you must give the right answer, or she will drag you into the depths. The answer is this: ‘Great Alexander still lives and rules!’

Michael Wood is professor of public history at the University of Manchester. His most recent TV series was King Alfred and the Anglo-Saxons.

Published on March 07, 2017 02:00

March 6, 2017

Sam’s historical recipe corner: Buttered beere

History Extra

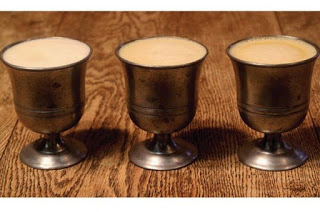

Buttered beere: a sweet drink enjoyed in the Tudor period. (Credit: Sam Nott)

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates buttered beere - a sweet, slightly alcoholic drink that warmed the cockles in Tudor times.

This is an authentic Tudor recipe from 1588, taken from The Good Huswifes Handmaide for the Kitchin. It’s similar to a caudle, a drink of warm wine or ale with sugar, eggs and spices, renowned for its medicinal properties and popular at the same period.

I love mulled wines and ciders, so the idea of this drink really appealed to me. The smells wafting through my kitchen while I was making it were delicious, though the drink itself was a bit, well, ‘robust’ – great when you’ve just come inside on a cold winter’s day, but for ordinary drinking a bit too heavy for me. My partner loved it, though – he drank the lot!

Ingredients

1,500ml (3 bottles) of good-quality ale

¼ tsp ground ginger

½ tsp ground cloves

½ tsp ground nutmeg

200g demerara or other natural brown sugar

5 egg yolks

100g unsalted butter, chopped into small lumps

Method

Pour the ale gently into a large saucepan and stir in the ginger, cloves and nutmeg. Bring slowly to the boil, then reduce the heat and simmer for a few minutes until the ale clears.

While the ale is simmering, whisk the egg yolks and sugar in a bowl until the mixture is light and creamy. Remove the spiced ale from the hob, add the egg yolk and sugar mixture, and stir until all ingredients are well blended.

Return to a low heat until the liquid starts to thicken, taking care not to overheat.

Simmer for five minutes, add the chopped butter and heat until it has melted. Hand-whisk the liquid until it becomes frothy.

Continue to heat for 10 minutes, then allow to cool to a drinkable temperature. Give the mixture another whisk, serve into a jug or small glasses (or tankards!) and drink while still warm.

Difficulty: 2/10

Time: 25 mins

Recipe from recipewise.co.uk This article was first published in the May 2014 issue of BBC History Magazine.

Buttered beere: a sweet drink enjoyed in the Tudor period. (Credit: Sam Nott)

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates buttered beere - a sweet, slightly alcoholic drink that warmed the cockles in Tudor times.

This is an authentic Tudor recipe from 1588, taken from The Good Huswifes Handmaide for the Kitchin. It’s similar to a caudle, a drink of warm wine or ale with sugar, eggs and spices, renowned for its medicinal properties and popular at the same period.

I love mulled wines and ciders, so the idea of this drink really appealed to me. The smells wafting through my kitchen while I was making it were delicious, though the drink itself was a bit, well, ‘robust’ – great when you’ve just come inside on a cold winter’s day, but for ordinary drinking a bit too heavy for me. My partner loved it, though – he drank the lot!

Ingredients

1,500ml (3 bottles) of good-quality ale

¼ tsp ground ginger

½ tsp ground cloves

½ tsp ground nutmeg

200g demerara or other natural brown sugar

5 egg yolks

100g unsalted butter, chopped into small lumps

Method

Pour the ale gently into a large saucepan and stir in the ginger, cloves and nutmeg. Bring slowly to the boil, then reduce the heat and simmer for a few minutes until the ale clears.

While the ale is simmering, whisk the egg yolks and sugar in a bowl until the mixture is light and creamy. Remove the spiced ale from the hob, add the egg yolk and sugar mixture, and stir until all ingredients are well blended.

Return to a low heat until the liquid starts to thicken, taking care not to overheat.

Simmer for five minutes, add the chopped butter and heat until it has melted. Hand-whisk the liquid until it becomes frothy.

Continue to heat for 10 minutes, then allow to cool to a drinkable temperature. Give the mixture another whisk, serve into a jug or small glasses (or tankards!) and drink while still warm.

Difficulty: 2/10

Time: 25 mins

Recipe from recipewise.co.uk This article was first published in the May 2014 issue of BBC History Magazine.

Published on March 06, 2017 02:00

March 5, 2017

The Toy Boat that Sailed the Seas of Time

Ancient Origins

A thousand years ago, for reasons we will never know, the residents of a tiny farmstead on the coast of central Norway filled an old well with dirt.

Maybe the water dried up, or maybe it became foul. But when archaeologists found the old well and dug it up in the summer of 2016, they discovered an unexpected surprise: a carefully carved toy, a wooden boat with a raised prow like a proud Viking ship, and a hole in the middle where a mast could have been stepped.

"This toy boat says something about the people who lived here," said Ulf Fransson, an archaeologist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's (NTNU) University Museum and one of two field leaders for the Ørland Main Air Station dig, where the well and the boat were found.

"First of all, it is not so very common that you find something that probably had to do with a child. But it also shows that the children at this farm could play, that they had permission to do something other than work in the fields or help around the farm."

The story of a small farm Finding a 1000-year-old Scandinavian toy boat is not that common, but it's not that uncommon either. In fact, a similar boat, in both age and construction, was found in downtown Trondheim in 1900, when the road in front of what is now the Trondheim Main Public Library was dug up to install sewer pipes.

The finds from the city at that time included a big spoon, different handles, pegs made of wood and "a little boat," according to the acquisitions list. This particular boat is even on display at the NTNU University Museum.

But in the Middle Ages, Trondheim was already established as a trading post and a city, one that was the nation's capital during the Viking Period until 1217. The concentration of people, and the wealth generated by trade almost certainly ensured that at least some children had the time and ability to play -- and thus toys, like the boat, to play with.

The find from Ørland, however, is very different, says Ingrid Ystgaard, an archaeologist who is head of the entire Ørland Main Air Base project.

"The Middle Age farm here is far from the sea, it is not that strategically located," she said. "There are other farms in Ørland that were better located."

Thus, this medieval farm was probably not the richest farm in the area, far from it. Yet life here was good enough so that someone had time to carve the toy boat for a child.

And the child had time to play with it.

A really cool toy

Boats were among the most technologically advanced objects made in the Middle Ages, Fransson said.

"If you built a Viking ship or a knarr (a type of boat), both children and adults would have thought it was very important, it was very specialized construction," he said.

"This is a 'real' boat. You don't have to do this much work to make a toy for a child," Fransson said. Whoever made it "worked to make something that also looked like a boat."

A realistic looking toy boat would thus have been perceived as "really cool, just like kids today think that race cars or planes are really cool," he said.

A model of a knarr – exhibited in a museum in Hedeby, in northern Germany. A knarr was a kind of a freighter, and was broader and shorter than a Viking war ship. Photo: Wikipedia

From bay to dry land

One of the things that archaeologists find most fascinating about the entire Ørland project has to do with the location of the dig itself.

Ørland is a rectangle of land on Norway's outer coast that looks like the head of a seahorse jutting into the Atlantic Ocean. But it didn't always look this way.

Consider this: Norway was once covered with kilometres of ice during the last Ice Age, more than 13,000 years ago. The great weight of the ice sheet depressed the land it sat on. After the glaciers disappeared, the land has gradually risen up, or rebounded.

This rebound created many changes along Norway's coast, most notably when land that was once an island rose up and became a part of the mainland, or an area that might have once been a shallow bay became dry land.

Ørland is one of these places. In roughly 200 BC, during the Iron Age, Ørland's big chunky peninsula looked more like a thin curled finger, with a big bay trapped on its southern side. Now that bay is dry land, nearly 2 km from the coast.

The Museum's single largest dig -- ever

Fortunately for the NTNU archaeologists, the Iron Age seaside location is precisely where the Ørland Main Air Base decided to expand its facilities to accommodate the purchase of new F-35 fighter jets, approved by the Norwegian Parliament in 2012.

The expansion plans triggered the need for an archaeological investigation. By the end of the 2016 field season, the NTNU University Museum had excavated nearly 120,000 m2, or roughly four times the size of a good-sized shopping mall, over three summers of fieldwork.

This makes it the single largest archaeological dig undertaken in the history of the museum.

An overview of the Ørland dig where the boat and shoes were found. Photo: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum

Seven farms, 1500 years

Ørland's fertile soil and strategic location near the mouth of Trondheim Fjord have ensured that people have lived in this area for millennia. So it should come as no surprise that the extensive dig uncovered traces of seven farms, spanning 1500 years, from 500 BC to 1000 AD.

The farms and farmyards are marked by postholes from structures, garbage dumps, and old wells. These Ørland farms, clustered as they are in one place, tell a unique story of how farming and farm communities evolved in the region over 1500 years, Ystgaard said.

"This is one of the biggest questions we are studying, the development of farms in this area over a span of 1500 years in the past. It is fantastic material," she said.

Garbage, seeds and pollen

While the field portion of the dig is now completed, archaeologists will continue to work their way through samples they've taken from garbage middens and cooking pits, and sift through dirt that has been removed from house and fence postholes.

A team from the University of Bergen is also hunting for clues about the vegetational history of the area based on pollen in cores they've taken from a nearby wetland called Stormyra.

The garbage middens and cooking pits, with their animal and fish bones and seashells, shed light on what people ate.

The dirt from the postholes offers a different view of daily life. Seeds and grains that have fallen on the ground tend to collect or be swept into corners. That makes postholes a treasure trove of information about the kinds of grains inhabitants ate or grew.

And lastly, by looking at changes in pollen types and amounts over the centuries, based on the cores collected in a nearby wetland, the researchers can reconstruct what the vegetation around the farms was like from the last 2500 years.

They should be able to detect changes caused by grazing animals, logging and farming, of course. All of these puzzle pieces help to fill in the many unknowns about how rural farms operated over the millennia, particularly during the Middle Ages, Ystgaard said.

"We know very little about the organization of farming in Norway in 1000 AD," Ystgaard said. "We have investigated almost no farms in rural communities in Norway from this time."

But with the wealth of information collected from Ørland, "we can look at the social development of farms during this period."

Shoes that date from St. Olav's reign as king

The well that yielded the toy boat and a second well contained other treasures, including pieces of leather that might amount to four leather shoes. The high water table in the filled wells helped preserve the shoes and the wooden boat.

If any of these objects had been discarded in a drier area, they would have probably decomposed, said Ellen Wijgård Randerz, a conservator at the NTNU University Museum who has responsibility for the artefacts from the project.

When the shoes were first discovered, the researchers thought they must be from more recent times than the Middle Ages, she said.

But when the radiocarbon dating information came back, it was "big news," said Ystgaard. "We found shoes that are contemporaneous with Olav den Hellige," who was king of Norway from 1015 to 1028.

One of the most complete shoes from this time period found at the Ørland site. Photo: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum.

This worn-out sole tells archaeologists that the owner was willing to pay to repair his shoes, since the front of the sole is clearly cut off. The size of the heel suggests the owner was probably male and had fairly large feet. Photo: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum

Walking in their shoes

Finding the shoes -- which look a little like moccasins, with a leather sole and simple, form fitted shape -- also tells the archaeologists that the farm was not that wealthy.

"These were more of an ordinary shoe, a work shoe that they wore every day," Fransson said. One of the shoe pieces that was found was a heel piece from a large sole, with a hole worn through it. The clean-cut front edge of the heel piece shows that "the shoe was worn out and they did repair it," he said.

But because the researchers found much of a whole shoe, "that tells me that they weren't that poor either, because they had the means to throw (a whole shoe) out," he said.

The shoe had been cut to fit the individual's foot and probably fit reasonably well, Randerz said, but people today probably would find it thin, cold and slippery.

"They might have stuffed the shoes with grass, and worn thick wool socks, but they were definitely not warm or dry," she said, studying the shoe. "It says a little about what it was like to walk in their shoes."

Top image: Some child likely played with this carved wooden boat a thousand years ago. It was found in an abandoned well during an extensive archaeological dig at the Ørland Main Air Station, on the coast west of Trondheim.

Credit: Åge Hojem, NTNU University The article ‘The toy boat that sailed the seas of time’ was published by The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

A thousand years ago, for reasons we will never know, the residents of a tiny farmstead on the coast of central Norway filled an old well with dirt.

Maybe the water dried up, or maybe it became foul. But when archaeologists found the old well and dug it up in the summer of 2016, they discovered an unexpected surprise: a carefully carved toy, a wooden boat with a raised prow like a proud Viking ship, and a hole in the middle where a mast could have been stepped.

"This toy boat says something about the people who lived here," said Ulf Fransson, an archaeologist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's (NTNU) University Museum and one of two field leaders for the Ørland Main Air Station dig, where the well and the boat were found.

"First of all, it is not so very common that you find something that probably had to do with a child. But it also shows that the children at this farm could play, that they had permission to do something other than work in the fields or help around the farm."

The story of a small farm Finding a 1000-year-old Scandinavian toy boat is not that common, but it's not that uncommon either. In fact, a similar boat, in both age and construction, was found in downtown Trondheim in 1900, when the road in front of what is now the Trondheim Main Public Library was dug up to install sewer pipes.

The finds from the city at that time included a big spoon, different handles, pegs made of wood and "a little boat," according to the acquisitions list. This particular boat is even on display at the NTNU University Museum.

But in the Middle Ages, Trondheim was already established as a trading post and a city, one that was the nation's capital during the Viking Period until 1217. The concentration of people, and the wealth generated by trade almost certainly ensured that at least some children had the time and ability to play -- and thus toys, like the boat, to play with.

The find from Ørland, however, is very different, says Ingrid Ystgaard, an archaeologist who is head of the entire Ørland Main Air Base project.

"The Middle Age farm here is far from the sea, it is not that strategically located," she said. "There are other farms in Ørland that were better located."

Thus, this medieval farm was probably not the richest farm in the area, far from it. Yet life here was good enough so that someone had time to carve the toy boat for a child.

And the child had time to play with it.

A really cool toy

Boats were among the most technologically advanced objects made in the Middle Ages, Fransson said.

"If you built a Viking ship or a knarr (a type of boat), both children and adults would have thought it was very important, it was very specialized construction," he said.

"This is a 'real' boat. You don't have to do this much work to make a toy for a child," Fransson said. Whoever made it "worked to make something that also looked like a boat."

A realistic looking toy boat would thus have been perceived as "really cool, just like kids today think that race cars or planes are really cool," he said.

A model of a knarr – exhibited in a museum in Hedeby, in northern Germany. A knarr was a kind of a freighter, and was broader and shorter than a Viking war ship. Photo: Wikipedia

From bay to dry land

One of the things that archaeologists find most fascinating about the entire Ørland project has to do with the location of the dig itself.

Ørland is a rectangle of land on Norway's outer coast that looks like the head of a seahorse jutting into the Atlantic Ocean. But it didn't always look this way.

Consider this: Norway was once covered with kilometres of ice during the last Ice Age, more than 13,000 years ago. The great weight of the ice sheet depressed the land it sat on. After the glaciers disappeared, the land has gradually risen up, or rebounded.

This rebound created many changes along Norway's coast, most notably when land that was once an island rose up and became a part of the mainland, or an area that might have once been a shallow bay became dry land.

Ørland is one of these places. In roughly 200 BC, during the Iron Age, Ørland's big chunky peninsula looked more like a thin curled finger, with a big bay trapped on its southern side. Now that bay is dry land, nearly 2 km from the coast.

The Museum's single largest dig -- ever

Fortunately for the NTNU archaeologists, the Iron Age seaside location is precisely where the Ørland Main Air Base decided to expand its facilities to accommodate the purchase of new F-35 fighter jets, approved by the Norwegian Parliament in 2012.

The expansion plans triggered the need for an archaeological investigation. By the end of the 2016 field season, the NTNU University Museum had excavated nearly 120,000 m2, or roughly four times the size of a good-sized shopping mall, over three summers of fieldwork.

This makes it the single largest archaeological dig undertaken in the history of the museum.

An overview of the Ørland dig where the boat and shoes were found. Photo: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum

Seven farms, 1500 years

Ørland's fertile soil and strategic location near the mouth of Trondheim Fjord have ensured that people have lived in this area for millennia. So it should come as no surprise that the extensive dig uncovered traces of seven farms, spanning 1500 years, from 500 BC to 1000 AD.

The farms and farmyards are marked by postholes from structures, garbage dumps, and old wells. These Ørland farms, clustered as they are in one place, tell a unique story of how farming and farm communities evolved in the region over 1500 years, Ystgaard said.

"This is one of the biggest questions we are studying, the development of farms in this area over a span of 1500 years in the past. It is fantastic material," she said.

Garbage, seeds and pollen

While the field portion of the dig is now completed, archaeologists will continue to work their way through samples they've taken from garbage middens and cooking pits, and sift through dirt that has been removed from house and fence postholes.

A team from the University of Bergen is also hunting for clues about the vegetational history of the area based on pollen in cores they've taken from a nearby wetland called Stormyra.

The garbage middens and cooking pits, with their animal and fish bones and seashells, shed light on what people ate.

The dirt from the postholes offers a different view of daily life. Seeds and grains that have fallen on the ground tend to collect or be swept into corners. That makes postholes a treasure trove of information about the kinds of grains inhabitants ate or grew.

And lastly, by looking at changes in pollen types and amounts over the centuries, based on the cores collected in a nearby wetland, the researchers can reconstruct what the vegetation around the farms was like from the last 2500 years.

They should be able to detect changes caused by grazing animals, logging and farming, of course. All of these puzzle pieces help to fill in the many unknowns about how rural farms operated over the millennia, particularly during the Middle Ages, Ystgaard said.

"We know very little about the organization of farming in Norway in 1000 AD," Ystgaard said. "We have investigated almost no farms in rural communities in Norway from this time."

But with the wealth of information collected from Ørland, "we can look at the social development of farms during this period."

Shoes that date from St. Olav's reign as king

The well that yielded the toy boat and a second well contained other treasures, including pieces of leather that might amount to four leather shoes. The high water table in the filled wells helped preserve the shoes and the wooden boat.

If any of these objects had been discarded in a drier area, they would have probably decomposed, said Ellen Wijgård Randerz, a conservator at the NTNU University Museum who has responsibility for the artefacts from the project.

When the shoes were first discovered, the researchers thought they must be from more recent times than the Middle Ages, she said.

But when the radiocarbon dating information came back, it was "big news," said Ystgaard. "We found shoes that are contemporaneous with Olav den Hellige," who was king of Norway from 1015 to 1028.

One of the most complete shoes from this time period found at the Ørland site. Photo: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum.

This worn-out sole tells archaeologists that the owner was willing to pay to repair his shoes, since the front of the sole is clearly cut off. The size of the heel suggests the owner was probably male and had fairly large feet. Photo: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum

Walking in their shoes

Finding the shoes -- which look a little like moccasins, with a leather sole and simple, form fitted shape -- also tells the archaeologists that the farm was not that wealthy.

"These were more of an ordinary shoe, a work shoe that they wore every day," Fransson said. One of the shoe pieces that was found was a heel piece from a large sole, with a hole worn through it. The clean-cut front edge of the heel piece shows that "the shoe was worn out and they did repair it," he said.

But because the researchers found much of a whole shoe, "that tells me that they weren't that poor either, because they had the means to throw (a whole shoe) out," he said.

The shoe had been cut to fit the individual's foot and probably fit reasonably well, Randerz said, but people today probably would find it thin, cold and slippery.

"They might have stuffed the shoes with grass, and worn thick wool socks, but they were definitely not warm or dry," she said, studying the shoe. "It says a little about what it was like to walk in their shoes."

Top image: Some child likely played with this carved wooden boat a thousand years ago. It was found in an abandoned well during an extensive archaeological dig at the Ørland Main Air Station, on the coast west of Trondheim.

Credit: Åge Hojem, NTNU University The article ‘The toy boat that sailed the seas of time’ was published by The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

Published on March 05, 2017 01:30

March 4, 2017

1066 – how the Viking diversion cost Harold his throne

History Extra

The battle of Stamford Bridge, 1066. (Mary Evans Picture Library/Alamy Stock Photo)

Cnut’s father, Swein Forkbeard, defeated Athelred, the famously Unready father of Edward the Confessor, to take the English throne, though he died soon after. Cnut in his turn took the crown from Edward’s half-brother, Edmund Ironside, becoming king of England in 1017. He reigned for nearly 20 years, during which time he was also king of Denmark and later king of Norway.

Unlike William the Conqueror, however, having obtained the throne of England he adopted English laws and customs and promoted Englishmen to positions of power, one such being the Sussex thegn who became Earl Godwin of Wessex. It is a measure of how entwined English and Danish affairs became, that Godwin married Gytha, the sister-in-law of Cnut’s own sister, Estrith, and their children, including Harold Godwinson and Tostig, had a mixture of both English and Danish names.

A family affair

It was Cnut’s early death, and the similarly early deaths of his three sons, that led to the break-up of his empire. While Edward the Confessor came unchallenged to the English throne, Cnut’s nephew, Sweyn Estrithsson, who claimed Denmark, had no such easy ride. He was immediately attacked by Magnus of Norway, who declared that Cnut’s son, Harthacnut, had promised both Denmark and England to him.

Harald Hardrada

Into this mixture came Harald Hardrada, one of the greatest Viking warriors of the age. Half-brother of Olaf II (aka St Olaf), the Norwegian king defeated by Cnut, he had left his homeland as a child and become immensely rich and battle-hardened fighting for the Byzantine emperor in Africa and the Middle East. Now returning home he met Sweyn, temporarily exiled in Sweden, and agreed to support him. He was soon enticed away, though, by Magnus, who was his nephew. According to King Harald’s Saga, our most detailed source of information about him, Hardrada agreed with Magnus that each would give the other half of all his possessions, and (as per the typical Norse agreement) the survivor would take all. Together they drove Sweyn from Denmark, but the death of Magnus soon after let Sweyn back in again. Hardrada, however, took up the fight once more, and they continued until 1064, when it was finally agreed that Hardrada would have Norway and Sweyn, Denmark.

This meant that, when Edward the Confessor died in January 1066 both Sweyn and Harald Hardrada could have made out a claim for the English crown – Sweyn as a successor to Cnut’s dynasty, and Hardrada as a result of the pact between Magnus and Harthacnut and his own pact with Magnus.

Instead it was Harold who was to become king. Harold went on to alienate Tostig, who had been Earl of Northumbria until the previous autumn when he was first expelled by its citizens and then exiled by Edward the Confessor. Tostig sought help for an invasion of England from, among others, William of Normandy (interested, but with his own plans), and Sweyn Estrithsson (no stomach for more fighting and contented with what he had), before enlisting Harald Hardrada to his cause. He promised Hardrada that half of England would rise to support him as king, since the new King Harold was so unpopular – a claim that proved far wide of the truth.

Tostig Godwinson tries to persuade King Sweyn II of Denmark and King Harald Hardrada of Norway to assist him in invading England, 1066. Engraving by L Gruner after D Maclise RA. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Into battle

A summer of preparation provided Hardrada and Tostig with some 300 shiploads of fighting men, around 12,000 in all, who in September 1066 followed the traditional Viking invasion route along the coast of Northumbria and up the rivers Humber and Ouse towards York. The ships were beached at Riccall, some 10 miles south of York, and the army proceeded towards that city to be met at Fulford, just outside, by an English army. Led by earls Edwin of Mercia and Morcar of Northumbria, both young men and inexperienced in warfare, this was no match for the invaders. On a battlefield between a river and a marsh (still visible but about to disappear under houses) they were totally routed.

Edwin and Morcar escaped though probably wounded. Many more did not, forced into the river to drown, or trapped on the marshy ground where corpses were “so thickly strewn… they paved a way across the fen”. York was forced to surrender, and to promise hostages, as well as men and provisions to support Hardrada – these to be brought a few days later to a little place on the crossing of the river Derwent at Stamford Bridge.

At the time, an English army consisted of two main elements. Housecarls were professional, well-trained, well-equipped elite fighters maintained by the king and also by the major earls. The bulk of the forces, however, were made up of the select fyrd, a militia provided from each town and village to serve for a two-month period and organised on a shire basis. They were equipped and paid by the area they represented and were generally well trained, providing a force of many thousands which could be called out when needed, usually on a rota basis, or in whichever area was threatened.

King Harold Godwinson had spent the summer months guarding the south coast against the expected invasion from Normandy, using mainly the southern select fyrd for this. No sooner had he stood down these men, thinking the invasion season past, than news was brought of Hardrada in the north. As he raced northwards to face this new foe, it was therefore the select fyrd from the Midlands and East Anglia that was now summoned to form the bulk of a new army.

Silver penny of Harold II (Harold Godwinson), minted in 1066, showing the obverse side. (Photo by CM Dixon/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Hardrada had returned to his ships at Riccall, and on 25 September set out from there with around two-thirds of his men to march across country the 10 miles to Stamford Bridge. It was a hot day, only five days after the victory at Fulford, and he clearly had no suspicion that the English king was anywhere near, so they left most of their armour behind. In fact King Harold had arrived at York the night before, and now, gathering his forces, set out to confront the invaders at the meeting place.

Taken completely by surprise, Hardrada immediately despatched a swift rider to Riccall for reinforcements, before forming a defensive shield wall ring on high ground above the river. In the fighting that followed the shield wall was broken. Hardrada himself, charged into the thickest of the action, swinging his great battle-axe and almost driving the English back, before a well-aimed arrow struck him in the throat and ended the life of the mighty warrior.

The battle might have ended there if Tostig had accepted an invitation to surrender. Instead he took up Hardrada’s banner and fought on through the heat of the afternoon until he too was slain. At that point Eystein Orri arrived with the reinforcements from Riccall, smashing into the weary English army in what became known as ‘Orri’s Storm’. Losses were heavy on both sides, but by evening it was clear Harold had won a great victory, almost annihilating the prime forces of Norway. Of the 300 ships that had arrived at Riccall, only 24 were needed to take the survivors home after Hardrada’s son had sued for peace.

The death of Tostig at the battle of Stamford Bridge, September 1066. By D Maclise. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

But Harold, too, had endured losses. His elite housecarls, fighting in the forefront of battle, had suffered many dead or injured. So, too, had those of Mercia and Northumbria, cut down in two battles fought within five days. The select fyrd of the Midlands and north had also taken a severe battering, while that of the south had spent most of the summer guarding the coast.

It is academic, of course, to speculate what kind of army might have been put into the field against William the Bastard had the Norman invasion been postponed to the following spring. As it was, less than a week after Stamford Bridge, news was brought to Harold at York that William had landed at Pevensey. Once again the select fyrd was summoned to duty. Once again the weary housecarls marched south with the king.

Through the long day at Hastings they stood firm against the best that William could throw at them. Only at the very end was their resolve defeated and their cause lost. In the final analysis it was surely the losses in the north that tipped the balance, shortening their battle line, and thinning their elite forces. It was indisputably Hardrada and his Viking invaders, though soundly beaten by him, that in the end cost Harold his crown and his life.

Teresa Cole is author of The Norman Conquest: William the Conqueror's Subjugation of England (Amberley Publishing, 2016).

The battle of Stamford Bridge, 1066. (Mary Evans Picture Library/Alamy Stock Photo)

Cnut’s father, Swein Forkbeard, defeated Athelred, the famously Unready father of Edward the Confessor, to take the English throne, though he died soon after. Cnut in his turn took the crown from Edward’s half-brother, Edmund Ironside, becoming king of England in 1017. He reigned for nearly 20 years, during which time he was also king of Denmark and later king of Norway.

Unlike William the Conqueror, however, having obtained the throne of England he adopted English laws and customs and promoted Englishmen to positions of power, one such being the Sussex thegn who became Earl Godwin of Wessex. It is a measure of how entwined English and Danish affairs became, that Godwin married Gytha, the sister-in-law of Cnut’s own sister, Estrith, and their children, including Harold Godwinson and Tostig, had a mixture of both English and Danish names.

A family affair

It was Cnut’s early death, and the similarly early deaths of his three sons, that led to the break-up of his empire. While Edward the Confessor came unchallenged to the English throne, Cnut’s nephew, Sweyn Estrithsson, who claimed Denmark, had no such easy ride. He was immediately attacked by Magnus of Norway, who declared that Cnut’s son, Harthacnut, had promised both Denmark and England to him.

Harald Hardrada

Into this mixture came Harald Hardrada, one of the greatest Viking warriors of the age. Half-brother of Olaf II (aka St Olaf), the Norwegian king defeated by Cnut, he had left his homeland as a child and become immensely rich and battle-hardened fighting for the Byzantine emperor in Africa and the Middle East. Now returning home he met Sweyn, temporarily exiled in Sweden, and agreed to support him. He was soon enticed away, though, by Magnus, who was his nephew. According to King Harald’s Saga, our most detailed source of information about him, Hardrada agreed with Magnus that each would give the other half of all his possessions, and (as per the typical Norse agreement) the survivor would take all. Together they drove Sweyn from Denmark, but the death of Magnus soon after let Sweyn back in again. Hardrada, however, took up the fight once more, and they continued until 1064, when it was finally agreed that Hardrada would have Norway and Sweyn, Denmark.

This meant that, when Edward the Confessor died in January 1066 both Sweyn and Harald Hardrada could have made out a claim for the English crown – Sweyn as a successor to Cnut’s dynasty, and Hardrada as a result of the pact between Magnus and Harthacnut and his own pact with Magnus.

Instead it was Harold who was to become king. Harold went on to alienate Tostig, who had been Earl of Northumbria until the previous autumn when he was first expelled by its citizens and then exiled by Edward the Confessor. Tostig sought help for an invasion of England from, among others, William of Normandy (interested, but with his own plans), and Sweyn Estrithsson (no stomach for more fighting and contented with what he had), before enlisting Harald Hardrada to his cause. He promised Hardrada that half of England would rise to support him as king, since the new King Harold was so unpopular – a claim that proved far wide of the truth.

Tostig Godwinson tries to persuade King Sweyn II of Denmark and King Harald Hardrada of Norway to assist him in invading England, 1066. Engraving by L Gruner after D Maclise RA. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Into battle

A summer of preparation provided Hardrada and Tostig with some 300 shiploads of fighting men, around 12,000 in all, who in September 1066 followed the traditional Viking invasion route along the coast of Northumbria and up the rivers Humber and Ouse towards York. The ships were beached at Riccall, some 10 miles south of York, and the army proceeded towards that city to be met at Fulford, just outside, by an English army. Led by earls Edwin of Mercia and Morcar of Northumbria, both young men and inexperienced in warfare, this was no match for the invaders. On a battlefield between a river and a marsh (still visible but about to disappear under houses) they were totally routed.

Edwin and Morcar escaped though probably wounded. Many more did not, forced into the river to drown, or trapped on the marshy ground where corpses were “so thickly strewn… they paved a way across the fen”. York was forced to surrender, and to promise hostages, as well as men and provisions to support Hardrada – these to be brought a few days later to a little place on the crossing of the river Derwent at Stamford Bridge.

At the time, an English army consisted of two main elements. Housecarls were professional, well-trained, well-equipped elite fighters maintained by the king and also by the major earls. The bulk of the forces, however, were made up of the select fyrd, a militia provided from each town and village to serve for a two-month period and organised on a shire basis. They were equipped and paid by the area they represented and were generally well trained, providing a force of many thousands which could be called out when needed, usually on a rota basis, or in whichever area was threatened.

King Harold Godwinson had spent the summer months guarding the south coast against the expected invasion from Normandy, using mainly the southern select fyrd for this. No sooner had he stood down these men, thinking the invasion season past, than news was brought of Hardrada in the north. As he raced northwards to face this new foe, it was therefore the select fyrd from the Midlands and East Anglia that was now summoned to form the bulk of a new army.

Silver penny of Harold II (Harold Godwinson), minted in 1066, showing the obverse side. (Photo by CM Dixon/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Hardrada had returned to his ships at Riccall, and on 25 September set out from there with around two-thirds of his men to march across country the 10 miles to Stamford Bridge. It was a hot day, only five days after the victory at Fulford, and he clearly had no suspicion that the English king was anywhere near, so they left most of their armour behind. In fact King Harold had arrived at York the night before, and now, gathering his forces, set out to confront the invaders at the meeting place.

Taken completely by surprise, Hardrada immediately despatched a swift rider to Riccall for reinforcements, before forming a defensive shield wall ring on high ground above the river. In the fighting that followed the shield wall was broken. Hardrada himself, charged into the thickest of the action, swinging his great battle-axe and almost driving the English back, before a well-aimed arrow struck him in the throat and ended the life of the mighty warrior.

The battle might have ended there if Tostig had accepted an invitation to surrender. Instead he took up Hardrada’s banner and fought on through the heat of the afternoon until he too was slain. At that point Eystein Orri arrived with the reinforcements from Riccall, smashing into the weary English army in what became known as ‘Orri’s Storm’. Losses were heavy on both sides, but by evening it was clear Harold had won a great victory, almost annihilating the prime forces of Norway. Of the 300 ships that had arrived at Riccall, only 24 were needed to take the survivors home after Hardrada’s son had sued for peace.

The death of Tostig at the battle of Stamford Bridge, September 1066. By D Maclise. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

But Harold, too, had endured losses. His elite housecarls, fighting in the forefront of battle, had suffered many dead or injured. So, too, had those of Mercia and Northumbria, cut down in two battles fought within five days. The select fyrd of the Midlands and north had also taken a severe battering, while that of the south had spent most of the summer guarding the coast.

It is academic, of course, to speculate what kind of army might have been put into the field against William the Bastard had the Norman invasion been postponed to the following spring. As it was, less than a week after Stamford Bridge, news was brought to Harold at York that William had landed at Pevensey. Once again the select fyrd was summoned to duty. Once again the weary housecarls marched south with the king.

Through the long day at Hastings they stood firm against the best that William could throw at them. Only at the very end was their resolve defeated and their cause lost. In the final analysis it was surely the losses in the north that tipped the balance, shortening their battle line, and thinning their elite forces. It was indisputably Hardrada and his Viking invaders, though soundly beaten by him, that in the end cost Harold his crown and his life.

Teresa Cole is author of The Norman Conquest: William the Conqueror's Subjugation of England (Amberley Publishing, 2016).

Published on March 04, 2017 02:00

March 3, 2017

What English Site is So Favored that Human Activity Spans Across 12,000 Years There?

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists in England digging to investigate the site of a future highway have found evidence of human occupation going as far back as 12,000 years. They call it a favored spot for human activity through the millennia.

The site in Lincolnshire has turned up flint tools from thousands of years ago, part of a Bronze Age barrow cemetery, evidence of Iron Age burials and roundhouses, a strong Roman-era presence, medieval features, and post-medieval structures.

A medieval era silver coin. (Lincolnshire County Council) “The archaeological work is already providing a fascinating glimpse into past communities, settlements and landscapes, illustrating that this area has been a continuously favoured spot for human activity from as far back as 12,000 years ago,” says a news release from the Lincolnshire County Council.

The work is being done at the Lincoln Eastern Bypass highway.

In addition to high-status Roman buildings, there are field systems, a possible vineyard, and pottery kilns from the Roman era.

Pre-Christian burial with Roman pottery grave goods. (Emily Norton/The Lincolnite)

There is also a possible stone tower from the medieval age along with a monastic grange (farm) with a boundary wall and substantial stone buildings and stone-lined wells.

From the post-medieval era there are farm buildings and a water management system, in addition to yards.

A medieval well under excavation ( Lincolnshire County Council )

Experts say the finds at the site are of national stature in England. There are still features to explore at the site, but so far it is the largest Mesolithic location ever found in Lincolnshire and among the largest in England.

Network Archaeology Ltd. is the company doing the excavations. Chris Taylor of Network Archaeology told LincolnshireLive :

“Potentially, the site could yield some very important discoveries. We've found signs of a high-status Roman building and, more interestingly, a possible Roman vineyard, which is rare north of the Home Counties.”

He said another big find was a cemetery from an as-yet unknown era near Washingborough Road that has 18 burials. The remains may be of a monastic order, Mr. Taylor said.

The company has also identified possible remains of a 12th century tower that could have been a fort from the time of the 1141 AD Battle of Lincoln. It’s possible it also may have been a beacon or a lookout to identify any hostile parties coming near the settlement.

A Roman bone pin. ( Lincolnshire County Council )

Councillor Richard Davies of Highways and Tranport told LincolnshireLive that it’s necessary to undertake archaeological work when building a new road “to find out what's gone on here for thousands of years for future generations to learn from and understand.”

It has been known for years that the River Witham Valley has been occupied for as long as the prehistoric era and was a focal point of activity. Scholars were aware that a medieval monastic grange was near the railway west of Washingborough.

Of the Stone Age activity, the news release states:

What is certain is that the presence of the Mesolithic flints illustrates that small communities of hunter-fisher-gatherers were exploiting the natural resources present by the river and its creeks. The later Neolithic occupants of this area were the first settled farmers, and whilst we have found flint artefacts of this period, we have yet to find any evidence of their settlements, which were probably sited away from the river on higher, drier ground.

Bronze Age arrowhead. ( Lincolnshire County Council )

The entire length of the roadway will be investigated. This section between River Witham and Washingborough Road will end early this year, but other sites along the route will be explored later.

Top image: The site includes a cemetery of 18 humans buried from east to west in the Christian fashion from an as-yet undated era. As of press time, bits of bone have been sent off for radio carbon dating. Source: Lincolnshire County Council

By Mark Miller

Archaeologists in England digging to investigate the site of a future highway have found evidence of human occupation going as far back as 12,000 years. They call it a favored spot for human activity through the millennia.

The site in Lincolnshire has turned up flint tools from thousands of years ago, part of a Bronze Age barrow cemetery, evidence of Iron Age burials and roundhouses, a strong Roman-era presence, medieval features, and post-medieval structures.

A medieval era silver coin. (Lincolnshire County Council) “The archaeological work is already providing a fascinating glimpse into past communities, settlements and landscapes, illustrating that this area has been a continuously favoured spot for human activity from as far back as 12,000 years ago,” says a news release from the Lincolnshire County Council.

The work is being done at the Lincoln Eastern Bypass highway.

In addition to high-status Roman buildings, there are field systems, a possible vineyard, and pottery kilns from the Roman era.

Pre-Christian burial with Roman pottery grave goods. (Emily Norton/The Lincolnite)

There is also a possible stone tower from the medieval age along with a monastic grange (farm) with a boundary wall and substantial stone buildings and stone-lined wells.

From the post-medieval era there are farm buildings and a water management system, in addition to yards.

A medieval well under excavation ( Lincolnshire County Council )

Experts say the finds at the site are of national stature in England. There are still features to explore at the site, but so far it is the largest Mesolithic location ever found in Lincolnshire and among the largest in England.

Network Archaeology Ltd. is the company doing the excavations. Chris Taylor of Network Archaeology told LincolnshireLive :

“Potentially, the site could yield some very important discoveries. We've found signs of a high-status Roman building and, more interestingly, a possible Roman vineyard, which is rare north of the Home Counties.”

He said another big find was a cemetery from an as-yet unknown era near Washingborough Road that has 18 burials. The remains may be of a monastic order, Mr. Taylor said.

The company has also identified possible remains of a 12th century tower that could have been a fort from the time of the 1141 AD Battle of Lincoln. It’s possible it also may have been a beacon or a lookout to identify any hostile parties coming near the settlement.

A Roman bone pin. ( Lincolnshire County Council )

Councillor Richard Davies of Highways and Tranport told LincolnshireLive that it’s necessary to undertake archaeological work when building a new road “to find out what's gone on here for thousands of years for future generations to learn from and understand.”

It has been known for years that the River Witham Valley has been occupied for as long as the prehistoric era and was a focal point of activity. Scholars were aware that a medieval monastic grange was near the railway west of Washingborough.

Of the Stone Age activity, the news release states:

What is certain is that the presence of the Mesolithic flints illustrates that small communities of hunter-fisher-gatherers were exploiting the natural resources present by the river and its creeks. The later Neolithic occupants of this area were the first settled farmers, and whilst we have found flint artefacts of this period, we have yet to find any evidence of their settlements, which were probably sited away from the river on higher, drier ground.

Bronze Age arrowhead. ( Lincolnshire County Council )

The entire length of the roadway will be investigated. This section between River Witham and Washingborough Road will end early this year, but other sites along the route will be explored later.

Top image: The site includes a cemetery of 18 humans buried from east to west in the Christian fashion from an as-yet undated era. As of press time, bits of bone have been sent off for radio carbon dating. Source: Lincolnshire County Council

By Mark Miller

Published on March 03, 2017 02:00

March 2, 2017

A brief history of how we fell in love with caffeine and chocolate

History Extra

A heated debate in a coffee house on Bride Lane, Fleet Street in London, c1688. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

These everyday beverages, so integral to British life, all originally came from far-flung regions: coffee from the Arabian peninsula, tea from China, and chocolate from Mesoamerica. By a strange coincidence, all arrived on our shores almost simultaneously during the middle of the 17th century, causing much debate about their benefits (or otherwise) to the health of the nation.

Here, Melanie King, the author of Tea, Coffee & Chocolate: How We Fell in Love with Caffeine, explores the origins of our obsession with caffeine and chocolate…

We may think of the 1650s as a time of puritanical austerity, with the banning of holly wreaths and the closing of theatres. But it was during these years of austerity that tea, coffee, and chocolate first went on sale in Britain.

The first cup of coffee appears to have been served in 1650, in the Angel Inn in Oxford, where an enterprising Jewish merchant began the long tradition of seeing students through their exams. The first cup of hot chocolate came seven years later, when in 1657 an advertisement informed the public that they could enjoy “an excellent West Indian drink called chocolate” at a house in Queen’s Head Alley, Bishopsgate. One year later, a “China drink, called by the Chineans Tcha,” was advertised as being sold at the Sultaness Head Coffee-House by the Royal Exchange. Tea was still an exotic novelty three years later, when Samuel Pepys reported in his diary that he had a cup of tea, “of which I had never drank before”.

The sudden arrival of these three new beverages, all from distant foreign parts, immediately became the source of much curiosity, anxiety, and debate. Entrepreneurs extolled their health benefits, while sceptics made equally dubious announcements about their supposed harmful effects. For example, a 1664 treatise by a tea merchant, entitled An Exact Description of the Growth, Quality and Vertues of the Leaf Tea, confidently claimed that tea “vanquisheth heavie Dreams, easeth the Brain, strengthneth the Memory”, while making the body “active and lusty”. As Pepys discovered, apothecaries recommended cups of tea as a decongestant. Coffee was also widely promoted as a ‘cure-all’. A 1660 advertisement by James Gough, who sold coffee in Oxford, stated that coffee had so many advantages that “it would be too tedious to nominate everything it is good for”. He nevertheless proceeded to give potential customers a long list that included consumption, gout, spleen, dropsy, rheumatism, headaches, and digestion. It was also effective, he pointedly noted, in banishing drowsiness in “students or others who are to sit up late, or all night”. One of the grandest claims for coffee, made in 1721, was that it stopped the spread of the bubonic plague.

Chocolate, meanwhile, was promoted by various treatises, advertisements, and poems, such as In Praise of Chocolate by James Wadsworth (who wrote under the compelling pseudonym Don Diego de Vadesforte). A “lick of chocolate”, Wadsworth claimed, not only helped women to get pregnant but, nine months later, eased the pains and length of childbirth! The cosmetic effects were equally irresistible: “Twill make Old women Young and Fresh.” Little wonder that fashionable women were soon sipping chocolate in bed, assisted by a special vessel, the mancerina, that prevented them from spilling the liquid onto their sheets.

Such bold claims about these new drinks did not go unchallenged. Equally vocal bands of detractors blamed the beverages for undermining the health, morale, and industry of the nation. The fact that they were to be drunk hot became a source of concern, since hot liquids were believed to boil the blood and therefore upset the balance of the four humours [the ancient Greek theory that the health of the body was controlled by four bodily fluids – blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm]. The perils of drinking hot liquids were graphically illustrated by a Fellow of the Royal Society, Dr Stephen Hales, who studied the effects of dipping a suckling pig’s tail in a cup of tea.

Smart gentlemen drinking, smoking and chatting in a coffee house, c1668. (Photo by Rischgitz/Getty Images)

Other alarming claims were made about tea drinking: it supposedly enfeebled the spirits, dried the brain, caused people to commit suicide, and led to a drop in productivity among workers, since even the lowliest labourers, as one opponent furiously noted, downed tools to enjoy a cup of tea. Coffee fared little better – it was denounced in a poem as a “decoction of the devils”, while a 1661 broadsheet claimed that it made men effeminate. In 1674, another broadsheet elaborated the effects of coffee on masculine performance, deploring this ‘heathenish liquor’ for making men unable to discharge their conjugal duties. The women of Britain were, as a result of their men sipping coffee, “languishing in an extremity of want”.

If coffee was suspect because it came from ‘heathen’ lands – the Middle East – chocolate raised suspicions because it was associated with Catholics: the Spanish monks and conquistadors who had been the first Europeans to sample and export it. Its use in Aztec rituals (it sometimes served as a substitute for blood) was also a cause for suspicion. A physician and naturalist named Martin Lister noted that chocolate may have been a suitable drink for “wild Indians” but was hardly one for the “pampered” British.

In the 1660s, chocolate even played a part in a high society sex scandal, when one of the mistresses of the Duke of York (the future James VII and II), Lady Denham, fell ill and died. The poet Andrew Marvell reported that the venom had apparently been administered in a cup of “mortal Chocolate”. An autopsy ruled out any toxin, though it also claimed (as the sceptical Samuel Pepys noted) that she had died a virgin.

Despite their many opponents, all three beverages – tea, coffee, and hot chocolate – became an established part of the British diet, and advice was quickly produced on how best to prepare and enjoy them. The philosopher and courtier Sir Kenelm Digby suggested that tea should be steeped for no longer than it took to recite Psalm 51 (about three minutes).

Pasqua Rosee, an Armenian immigrant who ran London’s first coffee shop, offered advice on how to make and drink a cup of coffee: the grounds should, he said, be boiled with spring water, the liquid then drunk on an empty stomach with no food taken for an hour afterwards. A recipe from 1667 recommended mixing coffee powder with equal quantities of butter and salad oil, proving that today’s trends such as bulletproof coffee – a mixture of coffee and butter – are nothing new. Meanwhile a doctor named Benjamin Moseley suggested that those suffering from flatulence or scurvy might wish to add mustard to their coffee.

Coffee was often consumed in coffee houses, which in London became venues for gossip, political debate and, in the eyes of the authorities, sedition. A publication entitled Rules and Orders of the Coffee House pointed out that, in these establishments, “people of all qualities and conditions” gathered, with no consideration for ranks or titles. Charles II grew so worried about the subversive political effects of coffee houses that in 1675 he ordered their closure. Such was the public indignation that within days he was forced to rescind his proclamation. Within a few decades, by the early 18th century, there were around 3,000 coffee houses in England.

Chocolate, too, was drunk in special establishments. Unlike coffee, it was not a democratic drink that catered to all ranks of society. More expensive than both tea and coffee, chocolate became the drink of the affluent. Consequently, chocolate houses – White’s, Ozinda’s, and the Cocoa Tree – were found in the aristocratic area around Pall Mall in London. Chocolate was often spiced up with exotic ingredients. It was used for dipping wigg bread (a bread spiced with cloves, nutmeg and caraway seeds), and it might be stirred into wine, brandy, port, or sherry. Pepys’s first encounter with chocolate was in a tavern where, as a hangover cure, it was mixed with his morning draft of wine.

Odd as some of these complaints and prescriptions might seem to us today, the health benefits of coffee, tea, and chocolate are still today the subject of much debate and scientific study. We may not have broadsheets anymore, but the internet is full of testimony about the pros and cons of drinking coffee; the fat-burning and cancer-fighting properties of green tea; and the cholesterol-lowering and memory-boosting powers of chocolate. These three drinks have as strong a hold on us as ever.

Melanie King is a freelance writer of historical non-fiction. Her book Tea, Coffee & Chocolate: How We Fell in Love with Caffeine (Bodleian Publishing) is out now.