MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 66

February 17, 2017

After 60 Years, Archaeologists are Thrilled to Find a Twelfth Dead Sea Scroll Cave

Ancient Origins

A team of archaeologists from the Hebrew University were exploring a cave near the Dead Sea and claim that the cave once hosted Dead Sea Scrolls from the Second Temple period. Unluckily, the ancient parchments are missing, possibly looted by Bedouins during the 20th century, but their discovery is still seen as an important find related to the famous Dead Sea Scrolls.

Cave Number 12

Until recently it was thought that only 11 caves contained scrolls. After the discovery of this cave, however, many scholars already suggest that it should be numbered as Cave 12. As happened with Cave 8, in which scroll jars but no scrolls were found, this cave will receive the designation Q12 with the Q (Qumran) indicating that no scrolls were found inside the cave.

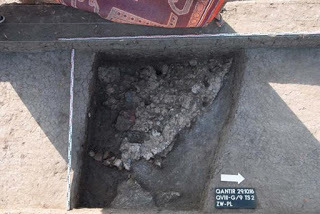

Fragments of shattered jars believed to have contained stolen Dead Sea scrolls, found in cave 12 near Qumran. (Casey L. Olson and Oren Gutfeld, Hebrew University)

The fascinating discovery was made by Dr. Oren Gutfeld and Ahiad Ovadia from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem's Institute of Archaeology, with the contributions of Dr. Randall Price and students from Liberty University in Virginia USA. The researchers became the first in over six decades to discover a new scroll cave and to accurately excavate it.

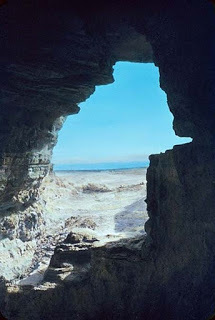

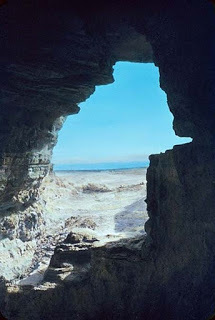

View of the Dead Sea from a Cave at Qumran. (Public Domain)

Dr. Oren Gutfeld, an archaeologist at the Hebrew University's Institute of Archaeology and director of the excavation, couldn’t hide his excitement in his statements to Times of Israel,

"This exciting excavation is the closest we've come to discovering new Dead Sea scrolls in 60 years. Until now, it was accepted that Dead Sea scrolls were found only in 11 caves at Qumran, but now there is no doubt that this is the 12th cave. Although at the end of the day no scroll was found, and instead we 'only' found a piece of parchment rolled up in a jug that was being processed for writing, the findings indicate beyond any doubt that the cave contained scrolls that were stolen.”

More than Just Storage Jars

The finds from the excavation don’t include only the storage jars which held the scrolls, but also fragments of scroll wrappings, a string that tied the scrolls, and a piece of worked leather that was a part of a scroll.

Cloth used for wrapping scrolls discovered in the cave. (Casey L. Olson and Oren Gutfeld)

The discovery of pottery and several flint blades, arrowheads, and a decorated stamp seal made of carnelian, a semi-precious stone, also indicates that this cave was used in the Chalcolithic and the Neolithic periods. Interestingly, pickaxes from the 1940s, a smoking gun from the Bedouin plunderers who dug in the cave, were also found along with the ancient remains.

A seal made of carnelian stone and arrowheads and flint blades were among the other artifacts found in the cave. (Casey L. Olson and Oren Gutfeld)

The Archaeological Significance The first Dead Sea Scrolls were found in 1947 by a Bedouin shepherd who unintentionally chucked a rock into a cave in the vicinity of Qumran. More texts surfaced in the years following during excavations in the Jordanian-held West Bank and were put on sale on the black market. This, however, is the first excavation to take place in the northern part of the Judean Desert as part of "Operation Scroll" - and archaeologists are optimistic to find new scroll material and evidence that will help to better understand the function of the caves.

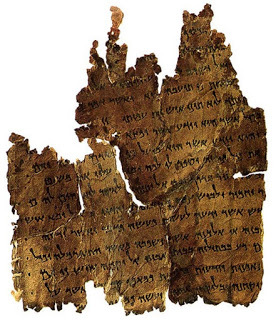

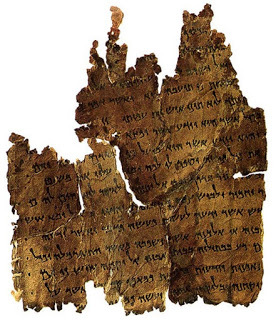

The Damascus Document Scroll 4Q271 (4QDf). (Public Domain)

Speaking on the discovery, Israel Hasson, Director-General of the Israel Antiquities Authority, said,

"The important discovery of another scroll cave attests to the fact that a lot of work remains to be done in the Judean Desert and finds of huge importance are still waiting to be discovered. We are in a race against time as antiquities thieves steal heritage assets worldwide for financial gain. The State of Israel needs to mobilize and allocate the necessary resources in order to launch a historic operation, together with the public, to carry out a systematic excavation of all the caves of the Judean Desert."

Top Image: Remnant of scroll found in a cave near Qumran after it was removed from jar. Source: Casey L. Olson and Oren Gutfeld, Hebrew University

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A team of archaeologists from the Hebrew University were exploring a cave near the Dead Sea and claim that the cave once hosted Dead Sea Scrolls from the Second Temple period. Unluckily, the ancient parchments are missing, possibly looted by Bedouins during the 20th century, but their discovery is still seen as an important find related to the famous Dead Sea Scrolls.

Cave Number 12

Until recently it was thought that only 11 caves contained scrolls. After the discovery of this cave, however, many scholars already suggest that it should be numbered as Cave 12. As happened with Cave 8, in which scroll jars but no scrolls were found, this cave will receive the designation Q12 with the Q (Qumran) indicating that no scrolls were found inside the cave.

Fragments of shattered jars believed to have contained stolen Dead Sea scrolls, found in cave 12 near Qumran. (Casey L. Olson and Oren Gutfeld, Hebrew University)

The fascinating discovery was made by Dr. Oren Gutfeld and Ahiad Ovadia from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem's Institute of Archaeology, with the contributions of Dr. Randall Price and students from Liberty University in Virginia USA. The researchers became the first in over six decades to discover a new scroll cave and to accurately excavate it.

View of the Dead Sea from a Cave at Qumran. (Public Domain)

Dr. Oren Gutfeld, an archaeologist at the Hebrew University's Institute of Archaeology and director of the excavation, couldn’t hide his excitement in his statements to Times of Israel,

"This exciting excavation is the closest we've come to discovering new Dead Sea scrolls in 60 years. Until now, it was accepted that Dead Sea scrolls were found only in 11 caves at Qumran, but now there is no doubt that this is the 12th cave. Although at the end of the day no scroll was found, and instead we 'only' found a piece of parchment rolled up in a jug that was being processed for writing, the findings indicate beyond any doubt that the cave contained scrolls that were stolen.”

More than Just Storage Jars

The finds from the excavation don’t include only the storage jars which held the scrolls, but also fragments of scroll wrappings, a string that tied the scrolls, and a piece of worked leather that was a part of a scroll.

Cloth used for wrapping scrolls discovered in the cave. (Casey L. Olson and Oren Gutfeld)

The discovery of pottery and several flint blades, arrowheads, and a decorated stamp seal made of carnelian, a semi-precious stone, also indicates that this cave was used in the Chalcolithic and the Neolithic periods. Interestingly, pickaxes from the 1940s, a smoking gun from the Bedouin plunderers who dug in the cave, were also found along with the ancient remains.

A seal made of carnelian stone and arrowheads and flint blades were among the other artifacts found in the cave. (Casey L. Olson and Oren Gutfeld)

The Archaeological Significance The first Dead Sea Scrolls were found in 1947 by a Bedouin shepherd who unintentionally chucked a rock into a cave in the vicinity of Qumran. More texts surfaced in the years following during excavations in the Jordanian-held West Bank and were put on sale on the black market. This, however, is the first excavation to take place in the northern part of the Judean Desert as part of "Operation Scroll" - and archaeologists are optimistic to find new scroll material and evidence that will help to better understand the function of the caves.

The Damascus Document Scroll 4Q271 (4QDf). (Public Domain)

Speaking on the discovery, Israel Hasson, Director-General of the Israel Antiquities Authority, said,

"The important discovery of another scroll cave attests to the fact that a lot of work remains to be done in the Judean Desert and finds of huge importance are still waiting to be discovered. We are in a race against time as antiquities thieves steal heritage assets worldwide for financial gain. The State of Israel needs to mobilize and allocate the necessary resources in order to launch a historic operation, together with the public, to carry out a systematic excavation of all the caves of the Judean Desert."

Top Image: Remnant of scroll found in a cave near Qumran after it was removed from jar. Source: Casey L. Olson and Oren Gutfeld, Hebrew University

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on February 17, 2017 01:30

February 16, 2017

Would You Drink a Lumpy Beer? People Living in China 5000 Years Ago Did!

Ancient Origins

Researchers have discovered a 5,000-year-old beer recipe by studying the residue on the inner walls of pottery vessels found in an excavated site in northeast China. It’s the earliest evidence of beer production in China so far.

On a recent afternoon, a small group of students gathered around a large table in one of the rooms at the Stanford Archaeology Center.

Li Liu, a professor in Chinese archaeology at Stanford University and coauthor of the study on the beer recipe published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, recently stood before students and a collection of plastic-covered glass beakers and water bottles filled with yellow, foamy liquid. “Archaeology is not just about reading books and analyzing artifacts,” says Liu.

“Trying to imitate ancient behavior and make things with the ancient method helps students really put themselves into the past and understand why people did what they did.”

So That’s Why Barley Went to China

The ancient Chinese made beer mainly with cereal grains, including millet and barley, as well as with Job’s tears, a type of grass from Asia, according to the research. Traces of yam and lily root parts also appeared in the concoction.

Liu says she was particularly surprised to find barley—which is used to make beer today—in the recipe because the earliest evidence to date of barley seeds in China dates to 4,000 years ago. This suggests why barley, which was first domesticated in western Asia, spread to China.

A blend of milled malted barley for beer brewing. (CC BY SA 3.0)

“Our results suggest the purpose of barley’s introduction in China could have been related to making alcohol rather than as a staple food,” Liu says.

The ancient Chinese beer looked more like porridge and likely tasted sweeter and fruitier than the clear, bitter beers of today. The ingredients used for fermentation were not filtered out, and straws were commonly used for drinking, Liu says.

Mashing or Spitting At the end of Liu’s class, each student tried to imitate the ancient Chinese beer using either wheat, millet, or barley seeds.

“People looked at me weird when they saw the ‘spit beer’ I was making for class.”

Some of the students’ creations. (Youtube Screenshot)

The students first covered their grain with water and let it sprout, in a process called malting. After the grain sprouted, the students crushed the seeds and put them in water again. The container with the mixture was then placed in the oven and heated to 65º degrees Celsius (149º F) for an hour, in a process called mashing. Afterward, the students sealed the container with plastic and let it stand at room temperature for about a week to ferment.

Alongside that experiment, the students tried to replicate making beer with a vegetable root called manioc. That type of beer-making, which is indigenous to many cultures in South America where the brew is referred to as “chicha,” involves chewing and spitting manioc, then boiling and fermenting the mixture.

Madeleine Ota, an undergraduate student in Liu’s course, says she knew nothing about the process of making beer before taking the class and was skeptical that her experiments would work. The mastication part of the experiment was especially foreign to her, she says.

“It was a strange process,” Ota says. “People looked at me weird when they saw the ‘spit beer’ I was making for class. I remember thinking, ‘How could this possibly turn into something alcoholic?’ But it was really rewarding to see that both experiments actually yielded results.”

Ota used red wheat for brewing her ancient Chinese beer. Despite the mold, the mixture had a pleasant fruity smell and a citrus taste, similar to a cider, Ota says. Her manioc beer, however, smelled like funky cheese, and Ota had no desire to check how it tasted.

The results of the students’ experiments are going to be used in further research on ancient alcohol-making that Liu and Wang are working on.

“The beer that students made and analyzed will be incorporated into our final research findings,” Wang says. “In that way, the class gives students an opportunity to not only experience what the daily work of some archaeologists looks like but also contribute to our ongoing research.”

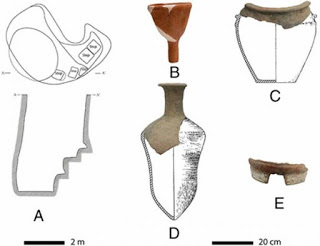

The “beer-making toolkit” from the site Liu and Wang are studying: (A) Pit H82 illustration in top and cross-section views, (B) funnel 1, (C) pot 6 in reconstructed form, (D) pot 3 in reconstructed form, and (E) pottery stove. (Wang et al.)

What Caused a Revolution?

For decades, archeologists have yearned to understand the origin of agriculture and what actions may have sparked humans to transition from hunting and gathering to settling and farming, a period historians call the Neolithic Revolution.

Studying the evolution of alcohol and food production provides a window into understanding ancient human behavior, says Liu.

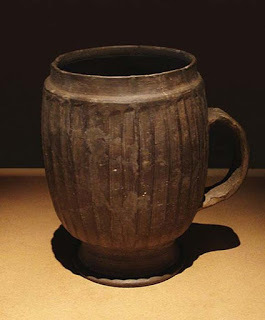

Late Neolithic Period (ca. 2500 - 2000 BC) large gray mug of the Henan Longshan Culture. (CC BY SA 2.5)

But it can be difficult to figure out precisely how the ancient people made alcohol and food from just examining artifacts because organic molecules easily break down with time. That’s why experiential archaeology is so important, Liu says.

“We are still trying to understand what kind of things were used back then,” Liu says.

Top Image: A more modern beer – without the lumps. Source: Public Domain

The article, originally titled ‘Ancient Chinese recipe makes lumpy, tasty beer’ by Stanford University was originally published on Futurity and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Researchers have discovered a 5,000-year-old beer recipe by studying the residue on the inner walls of pottery vessels found in an excavated site in northeast China. It’s the earliest evidence of beer production in China so far.

On a recent afternoon, a small group of students gathered around a large table in one of the rooms at the Stanford Archaeology Center.

Li Liu, a professor in Chinese archaeology at Stanford University and coauthor of the study on the beer recipe published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, recently stood before students and a collection of plastic-covered glass beakers and water bottles filled with yellow, foamy liquid. “Archaeology is not just about reading books and analyzing artifacts,” says Liu.

“Trying to imitate ancient behavior and make things with the ancient method helps students really put themselves into the past and understand why people did what they did.”

So That’s Why Barley Went to China

The ancient Chinese made beer mainly with cereal grains, including millet and barley, as well as with Job’s tears, a type of grass from Asia, according to the research. Traces of yam and lily root parts also appeared in the concoction.

Liu says she was particularly surprised to find barley—which is used to make beer today—in the recipe because the earliest evidence to date of barley seeds in China dates to 4,000 years ago. This suggests why barley, which was first domesticated in western Asia, spread to China.

A blend of milled malted barley for beer brewing. (CC BY SA 3.0)

“Our results suggest the purpose of barley’s introduction in China could have been related to making alcohol rather than as a staple food,” Liu says.

The ancient Chinese beer looked more like porridge and likely tasted sweeter and fruitier than the clear, bitter beers of today. The ingredients used for fermentation were not filtered out, and straws were commonly used for drinking, Liu says.

Mashing or Spitting At the end of Liu’s class, each student tried to imitate the ancient Chinese beer using either wheat, millet, or barley seeds.

“People looked at me weird when they saw the ‘spit beer’ I was making for class.”

Some of the students’ creations. (Youtube Screenshot)

The students first covered their grain with water and let it sprout, in a process called malting. After the grain sprouted, the students crushed the seeds and put them in water again. The container with the mixture was then placed in the oven and heated to 65º degrees Celsius (149º F) for an hour, in a process called mashing. Afterward, the students sealed the container with plastic and let it stand at room temperature for about a week to ferment.

Alongside that experiment, the students tried to replicate making beer with a vegetable root called manioc. That type of beer-making, which is indigenous to many cultures in South America where the brew is referred to as “chicha,” involves chewing and spitting manioc, then boiling and fermenting the mixture.

Madeleine Ota, an undergraduate student in Liu’s course, says she knew nothing about the process of making beer before taking the class and was skeptical that her experiments would work. The mastication part of the experiment was especially foreign to her, she says.

“It was a strange process,” Ota says. “People looked at me weird when they saw the ‘spit beer’ I was making for class. I remember thinking, ‘How could this possibly turn into something alcoholic?’ But it was really rewarding to see that both experiments actually yielded results.”

Ota used red wheat for brewing her ancient Chinese beer. Despite the mold, the mixture had a pleasant fruity smell and a citrus taste, similar to a cider, Ota says. Her manioc beer, however, smelled like funky cheese, and Ota had no desire to check how it tasted.

The results of the students’ experiments are going to be used in further research on ancient alcohol-making that Liu and Wang are working on.

“The beer that students made and analyzed will be incorporated into our final research findings,” Wang says. “In that way, the class gives students an opportunity to not only experience what the daily work of some archaeologists looks like but also contribute to our ongoing research.”

The “beer-making toolkit” from the site Liu and Wang are studying: (A) Pit H82 illustration in top and cross-section views, (B) funnel 1, (C) pot 6 in reconstructed form, (D) pot 3 in reconstructed form, and (E) pottery stove. (Wang et al.)

What Caused a Revolution?

For decades, archeologists have yearned to understand the origin of agriculture and what actions may have sparked humans to transition from hunting and gathering to settling and farming, a period historians call the Neolithic Revolution.

Studying the evolution of alcohol and food production provides a window into understanding ancient human behavior, says Liu.

Late Neolithic Period (ca. 2500 - 2000 BC) large gray mug of the Henan Longshan Culture. (CC BY SA 2.5)

But it can be difficult to figure out precisely how the ancient people made alcohol and food from just examining artifacts because organic molecules easily break down with time. That’s why experiential archaeology is so important, Liu says.

“We are still trying to understand what kind of things were used back then,” Liu says.

Top Image: A more modern beer – without the lumps. Source: Public Domain

The article, originally titled ‘Ancient Chinese recipe makes lumpy, tasty beer’ by Stanford University was originally published on Futurity and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Published on February 16, 2017 02:00

February 15, 2017

Leaving an Impression: Footprints Left by Children Found in Ancient Capital of Ramesses II

Ancient Origins

A group of German archaeologists has discovered many Pharaonic features in Egypt's Nile Delta, including the remains of a building complex, a mortar pit with footprints left by children, and a painted wall, as the Egyptian Antiquities Ministry announced Tuesday.

Newly Discovered Building Complex Described as “Monumental”

The head of the Ancient Egyptian Antiquities Department at Egypt’s antiquities ministry, Mahmoud Afifi, announced yesterday that at the ancient city of Pi-Ramesses an excavation team from the Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim in Germany has unearthed parts of a building complex as well as a mortar pit with children’s footprints. Mahmoud Afifi, impressed with the size (covering about 200 by 160 meters) of the newly discovered structure, described it as "truly monumental" and told Ahram Online that its layout suggests the complex was likely a palace or a temple. The buildings were discovered in the village of Qantir, situated about 60 miles (96.6 km) northeast of Cairo. The modern-day village of Qantir is located on the site of Pharaoh Rameses II's capital, "House of Ramses."

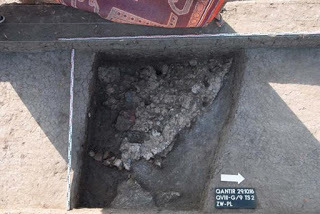

An excavated section of the newly-found building complex. (Ministry of Antiquities)

The Life and Legacy of Ramesses II

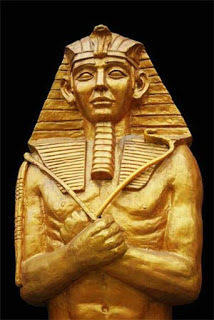

Ramesses II is arguably one of the most influential and remembered pharaohs of ancient Egypt. Ramesses II, the third pharaoh of the 19th Dynasty, ascended the throne of Egypt during his late teens in 1279 BC following the death of his father, Seti I. He is known to have ruled ancient Egypt for a total of 66 years, outliving many of his sons in the process – although he is believed to have fathered more than 100 children. As a result of his long and prosperous reign, Ramesses II was able to undertake numerous military campaigns against neighboring regions, as well as building monuments to the gods, and of course, to himself.

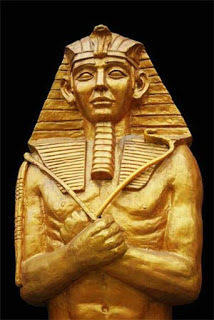

A statue of Ramesses II. Source: BigStockPhoto

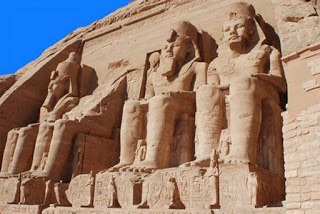

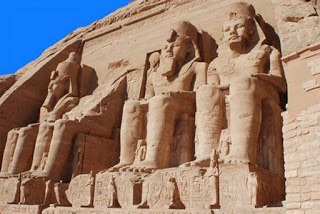

One of the victories of Ramesses II’s reign was the Battle of Kadesh. This was a battle fought between the Egyptians, led by Ramesses II and the Hittites under Muwatalli for the control of Syria. The battle took place in the spring of the 5th year of the reign of Ramesses II, and was caused by the defection of the Amurru from the Hittites to Egypt. This defection resulted in a Hittite attempt to bring the Amurru back into their sphere of influence. Ramesses II would have none of that and decided to protect his new vassal by marching his army north. The pharaoh’s campaign against the Hittites was also aimed at driving the Hittites, who have been causing trouble for the Egyptians since the time of Pharaoh Thutmose III, back beyond their borders. According to the Egyptian accounts, the Hittites were defeated, and Ramesses II had gained a great victory. The story of this victory is most famously monumentalized on the inside of the temple of Abu Simbel.

Abu Simbel Temple of King Ramses II, a masterpiece of pharaonic arts and buildings in Old Egypt. Source: BigStockPhoto

Promising Finds

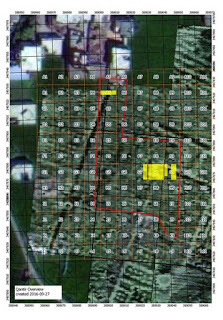

Henning Franzmeier, the mission director, explained that magnetic measurements were carried out in 2016 and through those measurements the building complex was located, "Based on the results of the measurements carried out by the team last year to determine the structure of the ancient city, a field was rented out, beneath which relevant structures were to be placed," he told Ahram Online. The excavation team also unearthed a small trench that was laid out in an area where they suspect the enclosure wall can be spotted. "These finds and archaeological features being uncovered are promising. They can all be dated to the pharaonic period," Franzmeier added.

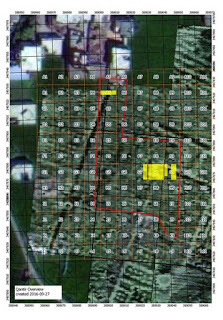

Result of a magnetic survey carried out at the site. (Peramses mission)

A Mortar Pit with Impressions of Children's Feet Last but not least, Franzmeier mentioned that just a few inches beneath the surface, a large number of walls were found, but what excited him the most was a mortar pit extending at least 2.5 x 8 meters (8 x 26 ft)

Remains of a multi-colored wall painting found in the pit. (Ministry of Antiquities)

In the pit, a sheet of mortar has been preserved at the bottom which shows some children’s' footprints mixed with the components of the mortar. "What's extraordinary is the filling of the pit, as it consists of smashed pieces of painted wall plaster. No motifs are recognizable so far, but we are certainly dealing with the remains of large-scale multi-colored wall paintings “ Franzmeier said as Independent of Egypt reports. An all-inclusive excavation of all fragments followed by permanent conservation and the rebuilding of motifs will be the subject of future seasons at this intriguing site.

Children’s footprints in the mortar pit. (Qantir-Pi-Ramesse Project; photographer Robert Stetefeld)

Top Image: A digital reconstruction of the city of Pi-Ramesses. (Ramesses the second)

Insert: Children’s footprints in the mortar pit. (Qantir-Pi-Ramesse Project; photographer Robert Stetefeld)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A group of German archaeologists has discovered many Pharaonic features in Egypt's Nile Delta, including the remains of a building complex, a mortar pit with footprints left by children, and a painted wall, as the Egyptian Antiquities Ministry announced Tuesday.

Newly Discovered Building Complex Described as “Monumental”

The head of the Ancient Egyptian Antiquities Department at Egypt’s antiquities ministry, Mahmoud Afifi, announced yesterday that at the ancient city of Pi-Ramesses an excavation team from the Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim in Germany has unearthed parts of a building complex as well as a mortar pit with children’s footprints. Mahmoud Afifi, impressed with the size (covering about 200 by 160 meters) of the newly discovered structure, described it as "truly monumental" and told Ahram Online that its layout suggests the complex was likely a palace or a temple. The buildings were discovered in the village of Qantir, situated about 60 miles (96.6 km) northeast of Cairo. The modern-day village of Qantir is located on the site of Pharaoh Rameses II's capital, "House of Ramses."

An excavated section of the newly-found building complex. (Ministry of Antiquities)

The Life and Legacy of Ramesses II

Ramesses II is arguably one of the most influential and remembered pharaohs of ancient Egypt. Ramesses II, the third pharaoh of the 19th Dynasty, ascended the throne of Egypt during his late teens in 1279 BC following the death of his father, Seti I. He is known to have ruled ancient Egypt for a total of 66 years, outliving many of his sons in the process – although he is believed to have fathered more than 100 children. As a result of his long and prosperous reign, Ramesses II was able to undertake numerous military campaigns against neighboring regions, as well as building monuments to the gods, and of course, to himself.

A statue of Ramesses II. Source: BigStockPhoto

One of the victories of Ramesses II’s reign was the Battle of Kadesh. This was a battle fought between the Egyptians, led by Ramesses II and the Hittites under Muwatalli for the control of Syria. The battle took place in the spring of the 5th year of the reign of Ramesses II, and was caused by the defection of the Amurru from the Hittites to Egypt. This defection resulted in a Hittite attempt to bring the Amurru back into their sphere of influence. Ramesses II would have none of that and decided to protect his new vassal by marching his army north. The pharaoh’s campaign against the Hittites was also aimed at driving the Hittites, who have been causing trouble for the Egyptians since the time of Pharaoh Thutmose III, back beyond their borders. According to the Egyptian accounts, the Hittites were defeated, and Ramesses II had gained a great victory. The story of this victory is most famously monumentalized on the inside of the temple of Abu Simbel.

Abu Simbel Temple of King Ramses II, a masterpiece of pharaonic arts and buildings in Old Egypt. Source: BigStockPhoto

Promising Finds

Henning Franzmeier, the mission director, explained that magnetic measurements were carried out in 2016 and through those measurements the building complex was located, "Based on the results of the measurements carried out by the team last year to determine the structure of the ancient city, a field was rented out, beneath which relevant structures were to be placed," he told Ahram Online. The excavation team also unearthed a small trench that was laid out in an area where they suspect the enclosure wall can be spotted. "These finds and archaeological features being uncovered are promising. They can all be dated to the pharaonic period," Franzmeier added.

Result of a magnetic survey carried out at the site. (Peramses mission)

A Mortar Pit with Impressions of Children's Feet Last but not least, Franzmeier mentioned that just a few inches beneath the surface, a large number of walls were found, but what excited him the most was a mortar pit extending at least 2.5 x 8 meters (8 x 26 ft)

Remains of a multi-colored wall painting found in the pit. (Ministry of Antiquities)

In the pit, a sheet of mortar has been preserved at the bottom which shows some children’s' footprints mixed with the components of the mortar. "What's extraordinary is the filling of the pit, as it consists of smashed pieces of painted wall plaster. No motifs are recognizable so far, but we are certainly dealing with the remains of large-scale multi-colored wall paintings “ Franzmeier said as Independent of Egypt reports. An all-inclusive excavation of all fragments followed by permanent conservation and the rebuilding of motifs will be the subject of future seasons at this intriguing site.

Children’s footprints in the mortar pit. (Qantir-Pi-Ramesse Project; photographer Robert Stetefeld)

Top Image: A digital reconstruction of the city of Pi-Ramesses. (Ramesses the second)

Insert: Children’s footprints in the mortar pit. (Qantir-Pi-Ramesse Project; photographer Robert Stetefeld)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on February 15, 2017 02:00

February 14, 2017

How to make 17th-century chocolate for Valentine's Day

History Extra

[image error]

To make Chocolate

Take your Choco Nutts and put them over the fire either In earthern pott, or kettle or frying pan keeping them stirring with a brass spoone till they be very hott and of black browne, then take them and pull of[f] the shells with your fingers. They must look of a black colour though not to[o] much burnt.

Then you must pound them in a great iron or brass mortar and seeth [sieve] them through a fine lawne [linen] seeth [sieve], and soe pound them againe and soe seeth it till all getts through, then take two pound of the powder and three quarters of a pound of good white sugar about 5d or 6d per pound being seethed [sieved] all one as the Choco Nutts, then put a Nuttmeg and half and ounce of Cinnamon and pound it well together and seeth it as herein before mentioned and to each pound of Choco Nutt the like quantity.

When you have mixt it altogether, take your mortar and putt it on the fire and make it pretty hott and take the pestle also, then putt the stuff in it and beat it till it comes to a smooth past[e], then take it out and weigh it into Quarters of pounds then Roll it round in your hands and putt it on a Quarter of sheet of paper and take the paper into your two hands and chafe it up and down till it comes to a short Roll.

English medical notebook, 1575-1663 (Wellcome Library MS.6812, p.137)

[image error]

To make Chocolate

Take your Choco Nutts and put them over the fire either In earthern pott, or kettle or frying pan keeping them stirring with a brass spoone till they be very hott and of black browne, then take them and pull of[f] the shells with your fingers. They must look of a black colour though not to[o] much burnt.

Then you must pound them in a great iron or brass mortar and seeth [sieve] them through a fine lawne [linen] seeth [sieve], and soe pound them againe and soe seeth it till all getts through, then take two pound of the powder and three quarters of a pound of good white sugar about 5d or 6d per pound being seethed [sieved] all one as the Choco Nutts, then put a Nuttmeg and half and ounce of Cinnamon and pound it well together and seeth it as herein before mentioned and to each pound of Choco Nutt the like quantity.

When you have mixt it altogether, take your mortar and putt it on the fire and make it pretty hott and take the pestle also, then putt the stuff in it and beat it till it comes to a smooth past[e], then take it out and weigh it into Quarters of pounds then Roll it round in your hands and putt it on a Quarter of sheet of paper and take the paper into your two hands and chafe it up and down till it comes to a short Roll.

English medical notebook, 1575-1663 (Wellcome Library MS.6812, p.137)

Published on February 14, 2017 02:30

February 13, 2017

Hundreds of Amazonian Geoglyphs Resembling Stonehenge Challenge Perceptions of Human Intervention in the Rainforest

Ancient Origins

Hundreds of enormous and mysterious ancient earthworks bearing a resemblance to those at Stonehenge were built in the Amazon rainforest a couple thousand years ago, as scientists have discovered after flying drones over the area. The Unknown Function of the Sites and Their Resemblance to Stonehenge The function of these puzzling sites remains a mystery, but several experts believe they are unlikely to have been villages, since archaeologists haven’t managed to recover many artifacts during excavations. Yet the fact that many of them are clustered on a 200 meter (656.17 ft.) high plateau implies that they may have been used for defense. However, other experts have suggested they were used for drainage or for channeling water since most were placed near spring water sources.

But Jenny Watling, an archaeologist at the University of São Paulo in Brazil and leader of the current research, sees a clear resemblance between the Amazonian sites with those of Stonehenge, as Telegraph reports,

"It is likely that the geoglyphs were used for similar functions to the Neolithic causewayed enclosures, i.e. public gathering, ritual sites. It is interesting to note that the format of the geoglyphs, with an outer ditch and inner wall enclosure, are what classicly describe henge sites. The earliest phases at Stonhenge consisted of a similarly layed-out enclosure."

One of the ring ditches found in the Amazon (Jenny Watling) and Stonehenge. (English Heritage)

Despite Stonehenge being around 2,500 years older than the geoglyphs found in Brazil, Watling seems confident that they are likely to represent a similar period in social development. It’s also interesting that until recently, it was believed that the earthworks dated to around 200 AD. However, the latest study has revealed that they are, in fact, much older.

New Study Suggests that the Rainforest Ecosystem has been Untouched by Humans

The unusual earthworks, known by archaeologists as “geoglyphs’’ are estimated to be nearly 2,000 years old, and include square, straight, and ring-like ditches. According to Jenny Watling, the geoglyphs were discovered in the 1980s, when deforestation for cattle ranching and other agricultural purposes exposed them. Since then, hundreds of the earthen foundations have been found in a region more than 150 miles (241.40 km) across, covering northern Bolivia and Brazil’s Amazonas state. The ditches were sculpted from the clay-rich soils of the Amazon and are typically around 36 feet (11 meters) wide and 13 feet (4 meters) deep. It is estimated that they were dug at various times between the 1st and 15th centuries.

One of the square geoglyphs. (Diego Gurgel)

"There's been a very big debate circling for decades now about how pristine or man-made the Amazonian forests are," Watling told Live Science, suggesting that despite human involvement in the area, the rainforest ecosystem has been relatively untouched by humans. “The fact that these sites lay hidden for centuries beneath mature rainforest really challenges the idea that Amazonian forests are ‘pristine ecosystems,” said Dr. Watling, who added,

“Our evidence that Amazonian forests have been managed by indigenous peoples long before European contact should not be cited as justification for the destructive, unsustainable land-use practiced today. It should instead serve to highlight the ingenuity of past subsistence regimes that did not lead to forest degradation, and the importance of indigenous knowledge for finding more sustainable land-use alternatives”.

The research was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Two ring henges. (University of Exeter)

Top Image: Both round and square enclosures were discovered by drones in the Amazon rainforest region. Source: Salman Kahn and José Iriarte

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Hundreds of enormous and mysterious ancient earthworks bearing a resemblance to those at Stonehenge were built in the Amazon rainforest a couple thousand years ago, as scientists have discovered after flying drones over the area. The Unknown Function of the Sites and Their Resemblance to Stonehenge The function of these puzzling sites remains a mystery, but several experts believe they are unlikely to have been villages, since archaeologists haven’t managed to recover many artifacts during excavations. Yet the fact that many of them are clustered on a 200 meter (656.17 ft.) high plateau implies that they may have been used for defense. However, other experts have suggested they were used for drainage or for channeling water since most were placed near spring water sources.

But Jenny Watling, an archaeologist at the University of São Paulo in Brazil and leader of the current research, sees a clear resemblance between the Amazonian sites with those of Stonehenge, as Telegraph reports,

"It is likely that the geoglyphs were used for similar functions to the Neolithic causewayed enclosures, i.e. public gathering, ritual sites. It is interesting to note that the format of the geoglyphs, with an outer ditch and inner wall enclosure, are what classicly describe henge sites. The earliest phases at Stonhenge consisted of a similarly layed-out enclosure."

One of the ring ditches found in the Amazon (Jenny Watling) and Stonehenge. (English Heritage)

Despite Stonehenge being around 2,500 years older than the geoglyphs found in Brazil, Watling seems confident that they are likely to represent a similar period in social development. It’s also interesting that until recently, it was believed that the earthworks dated to around 200 AD. However, the latest study has revealed that they are, in fact, much older.

New Study Suggests that the Rainforest Ecosystem has been Untouched by Humans

The unusual earthworks, known by archaeologists as “geoglyphs’’ are estimated to be nearly 2,000 years old, and include square, straight, and ring-like ditches. According to Jenny Watling, the geoglyphs were discovered in the 1980s, when deforestation for cattle ranching and other agricultural purposes exposed them. Since then, hundreds of the earthen foundations have been found in a region more than 150 miles (241.40 km) across, covering northern Bolivia and Brazil’s Amazonas state. The ditches were sculpted from the clay-rich soils of the Amazon and are typically around 36 feet (11 meters) wide and 13 feet (4 meters) deep. It is estimated that they were dug at various times between the 1st and 15th centuries.

One of the square geoglyphs. (Diego Gurgel)

"There's been a very big debate circling for decades now about how pristine or man-made the Amazonian forests are," Watling told Live Science, suggesting that despite human involvement in the area, the rainforest ecosystem has been relatively untouched by humans. “The fact that these sites lay hidden for centuries beneath mature rainforest really challenges the idea that Amazonian forests are ‘pristine ecosystems,” said Dr. Watling, who added,

“Our evidence that Amazonian forests have been managed by indigenous peoples long before European contact should not be cited as justification for the destructive, unsustainable land-use practiced today. It should instead serve to highlight the ingenuity of past subsistence regimes that did not lead to forest degradation, and the importance of indigenous knowledge for finding more sustainable land-use alternatives”.

The research was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Two ring henges. (University of Exeter)

Top Image: Both round and square enclosures were discovered by drones in the Amazon rainforest region. Source: Salman Kahn and José Iriarte

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on February 13, 2017 02:00

February 12, 2017

Archaeologists to Explore Mysterious Underground Structure at the Desert Fortress of Masada

Ancient Origins

A team of archaeologists from Tel Aviv University have returned to Masada in Israel, after a 11-year hiatus, in order to excavate previously unexplored areas of the desert mountain fortress, including a mysterious underground structure. Once a pleasure palace for Herod the Great, Masada is most well-known for the deaths of around 960 Jewish rebels and their families in 74 AD, who chose to commit suicide rather than be captured or slaughtered by the Romans.

Fresh Explorations of an Ancient Treasure

For the first time since 2006, a Tel Aviv University team, headed by Roman-period archaeologist Guy Stiebel, have launched new excavations at the UNESCO World Heritage Site, examining previously untouched areas of the legendary desert mountain fortress. “This is the next generation,” Stiebel told The Times of Israel, adding that his team plan to excavate new sections of the Jewish rebel dwellings, as well as a garden constructed by Herod, “Our intention is to further explore a mysterious underground structure that was detected in the earliest (1924) aerial photographs of the site. The building has remained hitherto unexplored.”

Dr Stiebel did not add any further information about the underground structure and what it may have been used for. But it is possible that it was used as a hideout or escape route during the Siege of Masada.

Dr. Stiebel expressed his excitement to return to the site after an eleven-year absence in his statements to i24news, “A lifetime would not suffice to get a glimpse of all the hidden beauties of Masada. Its magic is not just in the military equipment, it is also in small things.” Even though several experts believe that more than 95% of Masada’s potential has already been exploited, Stiebel believe that its core is yet to be discovered, including the mysterious underground structure that lies there and is waiting to be closely explored.

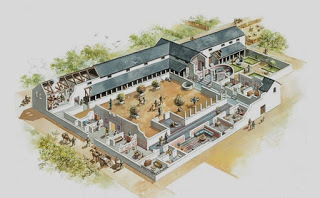

A model of the northern palace as Masada (public domain)

The Dramatic History of the Desert Fortress of Masada The ancient fortress of Masada stands on the eastern edge of the Judean Desert. With a sheer drop of more than 400 meters to the western shore of the Dead Sea, the view from the top of the plateau would have been breath-taking. Yet, the silence of the ruins belies one of the most interesting episodes in Jewish history.

While the first structures on Masada were apparently built by the Hasmonaean king, Alexander Jannaeus in the early 1st century BC, most of the structures were constructed by Herod the Great during the latter half of that century. Having conquered Masada in 42 BC, Masada became a safe refuge for Herod and his family during their long struggle for power in Israel. Apart from being a fortress, Masada was also a pleasure palace for Herod. For instance, it was designed along the lines of a Roman villa, and several amphorae found in Masada’s storerooms had Latin inscriptions, indicating that they contained wine imported all the way from Italy. After the death of Herod in 4 BC, Masada became a military outpost, and housed a Roman garrison, presumably of auxiliary forces.

A Roman siege ramp seen from above ( CC by SA 3.0 )

In 66 AD, the first Jewish Revolt broke out. The most comprehensive record of this record can be found in Flavius Josephus’ The Jewish War. According to Josephus, a group of Jewish zealots, the Sicarii succeeded in seizing Masada from the Romans in the winter of 66 AD. After the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD, Masada was filled up with refugees who escaped and were determined to continue the struggle against the Romans. Hence, Masada became a base for their raiding operations for the following two years. In the winter of 73/74 AD, the governor of Judaea, Flavius Silva, decided to conquer Masada and crush the resistance once and for all. According to Josephus Flavius, the only historical source for the battle, the Jewish rebels committed mass suicide before Roman troops stormed the battlements, even though many historians and archaeologists have challenged the historicity of that account.

“Next Generation” Excavation Begins

The first excavations in the area took place in the period from 1963 to 1965 under former IDF chief of staff and archaeologist Yigal Yadin. The dry desert climate allowed the preservation of classy frescoes and organic remains belonging to the Jewish rebels who holed up on the mountaintop. The archaeological team will be posting updates and photos from the site on its Facebook page

Top image: Aerial view of the desert fortress of Masada ( CC by SA 4.0 )

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A team of archaeologists from Tel Aviv University have returned to Masada in Israel, after a 11-year hiatus, in order to excavate previously unexplored areas of the desert mountain fortress, including a mysterious underground structure. Once a pleasure palace for Herod the Great, Masada is most well-known for the deaths of around 960 Jewish rebels and their families in 74 AD, who chose to commit suicide rather than be captured or slaughtered by the Romans.

Fresh Explorations of an Ancient Treasure

For the first time since 2006, a Tel Aviv University team, headed by Roman-period archaeologist Guy Stiebel, have launched new excavations at the UNESCO World Heritage Site, examining previously untouched areas of the legendary desert mountain fortress. “This is the next generation,” Stiebel told The Times of Israel, adding that his team plan to excavate new sections of the Jewish rebel dwellings, as well as a garden constructed by Herod, “Our intention is to further explore a mysterious underground structure that was detected in the earliest (1924) aerial photographs of the site. The building has remained hitherto unexplored.”

Dr Stiebel did not add any further information about the underground structure and what it may have been used for. But it is possible that it was used as a hideout or escape route during the Siege of Masada.

Dr. Stiebel expressed his excitement to return to the site after an eleven-year absence in his statements to i24news, “A lifetime would not suffice to get a glimpse of all the hidden beauties of Masada. Its magic is not just in the military equipment, it is also in small things.” Even though several experts believe that more than 95% of Masada’s potential has already been exploited, Stiebel believe that its core is yet to be discovered, including the mysterious underground structure that lies there and is waiting to be closely explored.

A model of the northern palace as Masada (public domain)

The Dramatic History of the Desert Fortress of Masada The ancient fortress of Masada stands on the eastern edge of the Judean Desert. With a sheer drop of more than 400 meters to the western shore of the Dead Sea, the view from the top of the plateau would have been breath-taking. Yet, the silence of the ruins belies one of the most interesting episodes in Jewish history.

While the first structures on Masada were apparently built by the Hasmonaean king, Alexander Jannaeus in the early 1st century BC, most of the structures were constructed by Herod the Great during the latter half of that century. Having conquered Masada in 42 BC, Masada became a safe refuge for Herod and his family during their long struggle for power in Israel. Apart from being a fortress, Masada was also a pleasure palace for Herod. For instance, it was designed along the lines of a Roman villa, and several amphorae found in Masada’s storerooms had Latin inscriptions, indicating that they contained wine imported all the way from Italy. After the death of Herod in 4 BC, Masada became a military outpost, and housed a Roman garrison, presumably of auxiliary forces.

A Roman siege ramp seen from above ( CC by SA 3.0 )

In 66 AD, the first Jewish Revolt broke out. The most comprehensive record of this record can be found in Flavius Josephus’ The Jewish War. According to Josephus, a group of Jewish zealots, the Sicarii succeeded in seizing Masada from the Romans in the winter of 66 AD. After the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD, Masada was filled up with refugees who escaped and were determined to continue the struggle against the Romans. Hence, Masada became a base for their raiding operations for the following two years. In the winter of 73/74 AD, the governor of Judaea, Flavius Silva, decided to conquer Masada and crush the resistance once and for all. According to Josephus Flavius, the only historical source for the battle, the Jewish rebels committed mass suicide before Roman troops stormed the battlements, even though many historians and archaeologists have challenged the historicity of that account.

“Next Generation” Excavation Begins

The first excavations in the area took place in the period from 1963 to 1965 under former IDF chief of staff and archaeologist Yigal Yadin. The dry desert climate allowed the preservation of classy frescoes and organic remains belonging to the Jewish rebels who holed up on the mountaintop. The archaeological team will be posting updates and photos from the site on its Facebook page

Top image: Aerial view of the desert fortress of Masada ( CC by SA 4.0 )

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on February 12, 2017 02:00

February 11, 2017

Britons were eating frogs' legs 8,000 years before the French

History Extra

They’ve long been considered a French delicacy, but a new archeological dig in Wiltshire suggests frogs' legs may have been first enjoyed in Britain.

Among evidence of life in the eighth millennia BC, found at the Blick Mead site at Amesbury, researchers from the University of Buckingham discovered the burnt leg bone of a toad.

The team also found small bones of trout or salmon, and burnt Aurochs bones (the predecessor of cows).

The finds date to between 6250BC and 7600BC, making the discovery the earliest evidence of a cooked toad or frog’s leg found in the world, and around eight millennia before the French.

David Jacques, senior research fellow in archaeology at the University of Buckingham, said: “It would appear that thousands of years ago people were eating a Heston Blumenthal-style menu on this site, one and a quarter miles from Stonehenge, consisting of toads’ legs, aurochs, wild boar and red deer with hazelnuts for main, another course of salmon and trout, and finishing off with blackberries.

“This is significant for our understanding of the way people were living around 5,000 years before the building of Stonehenge and it begs the question – where are the frogs now?”

The latest information is based on a report by fossil mammal specialist Simon Parfitt, of the Natural History Museum, who looked at the find.

The site already boasts one of the biggest collections of flints and cooked animal bones in northwestern Europe. It has resulted in 12,000 finds, all from the Mesolithic era, which fell between the Palaeolithic and the Neolithic.

The team hopes to confirm Amesbury as the UK's oldest continuous settlement. The dig, which will run until 25 October, is being filmed and made into a documentary by the BBC, to be screened at a later date.

Andy Rhind-Tutt, chairman of Amesbury Museum and Heritage Trust and co-ordinator of the community involvement on the dig, said the site at Blick Mead could help to explain why Stonehenge is where it is.

“No one would have built Stonehenge without there being something unique and really special about the area,” he said.

“There must have been something significant here beforehand and Blick Mead, with its constant temperature spring sitting alongside the river Avon, may well be it.

“I believe that as we uncover more about the site over the coming days and weeks, we will discover it to be the greatest, oldest and most significant Mesolithic home base ever found in Britain.”

They’ve long been considered a French delicacy, but a new archeological dig in Wiltshire suggests frogs' legs may have been first enjoyed in Britain.

Among evidence of life in the eighth millennia BC, found at the Blick Mead site at Amesbury, researchers from the University of Buckingham discovered the burnt leg bone of a toad.

The team also found small bones of trout or salmon, and burnt Aurochs bones (the predecessor of cows).

The finds date to between 6250BC and 7600BC, making the discovery the earliest evidence of a cooked toad or frog’s leg found in the world, and around eight millennia before the French.

David Jacques, senior research fellow in archaeology at the University of Buckingham, said: “It would appear that thousands of years ago people were eating a Heston Blumenthal-style menu on this site, one and a quarter miles from Stonehenge, consisting of toads’ legs, aurochs, wild boar and red deer with hazelnuts for main, another course of salmon and trout, and finishing off with blackberries.

“This is significant for our understanding of the way people were living around 5,000 years before the building of Stonehenge and it begs the question – where are the frogs now?”

The latest information is based on a report by fossil mammal specialist Simon Parfitt, of the Natural History Museum, who looked at the find.

The site already boasts one of the biggest collections of flints and cooked animal bones in northwestern Europe. It has resulted in 12,000 finds, all from the Mesolithic era, which fell between the Palaeolithic and the Neolithic.

The team hopes to confirm Amesbury as the UK's oldest continuous settlement. The dig, which will run until 25 October, is being filmed and made into a documentary by the BBC, to be screened at a later date.

Andy Rhind-Tutt, chairman of Amesbury Museum and Heritage Trust and co-ordinator of the community involvement on the dig, said the site at Blick Mead could help to explain why Stonehenge is where it is.

“No one would have built Stonehenge without there being something unique and really special about the area,” he said.

“There must have been something significant here beforehand and Blick Mead, with its constant temperature spring sitting alongside the river Avon, may well be it.

“I believe that as we uncover more about the site over the coming days and weeks, we will discover it to be the greatest, oldest and most significant Mesolithic home base ever found in Britain.”

Published on February 11, 2017 02:00

February 10, 2017

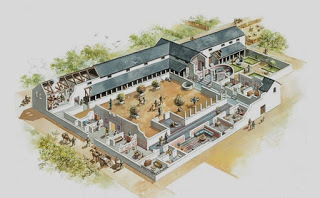

Who Said Ancient People Had it Tough? Luxury Homes and Underfloor Heating Were a Part of Life in the Roman Province of Britannia

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists have uncovered a fantastic Roman mosaic and evidence of good living over 1,500 years ago in Leicester city centre in a home with underfloor heating.

The team from the University of Leicester is currently excavating a large site on the corner of Highcross Street and Vaughan Way, next to Leicester's John Lewis car park. The project, which has been running since November 2016, is uncovering exciting new evidence for Leicester's Roman past, including evidence for a Roman street, and a Roman house once floored with mosaic pavements.

The excavation is funded by Ingleby, who will be developing the site into apartments, and the team from University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) is working closely with the architects to minimise the impact of the new building on the underlying archaeology. Modern rubble and Victorian garden soil are being removed from the footprint of the proposed building to expose the medieval and Roman archaeology. This allows archaeologists to identify where the footings for the new building will have an adverse effect on important archaeological remains, which can then either be designed around, or excavated before they are destroyed, leaving most of the archaeology preserved intact beneath the new building.

The mosaic floor. ( Carl Vivian / University of Leicester )

The excavation covers nearly two-thirds of a Roman insula (city block), giving archaeologists an amazing opportunity to investigate life in the north-east quarter of the Roman town. So far, a Roman street and three Roman buildings have been identified.

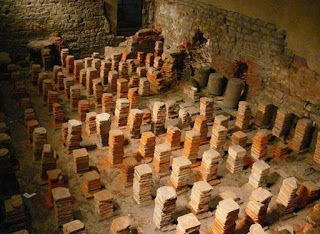

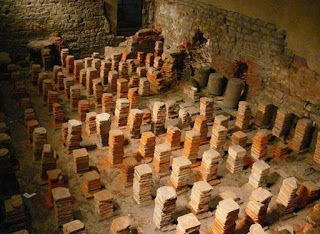

Today, Highcross Street still follows the line of the main road leading from the Roman forum (beneath Jubilee Square) to the north gate, at the junction with Sanvey Gate. On this western side of the site a large Roman building has been uncovered. Two ranges of rooms flanked by a corridor or portico appear to surround a courtyard. At least one room had a hypocaust (underfloor heating), and it is likely that this is a large townhouse, reminiscent of the Vine Street courtyard house excavated nearby, beneath the John Lewis car park, in 2006

A hypocaust (Latin hypocaustum) in the Roman Baths, Bath, UK.

A hypocaust is an ancient Roman system of central heating. The word literally means "heat from below", from the Greek hypo meaning below or underneath, and kaiein, to burn or light a fire. (Ad Meskens/ CC BY SA 3.0 )

North of this building, running east to west across the northern edge of the site, close to All Saints' Church, a cambered gravel street has been recorded. Activity along this street appears to have been quiet during the Roman period. Roadside ditches and boundary walls have been identified, but no substantial buildings are present. Instead, activity seems to be more ephemeral in natured, gardens and yards, probably with some timber buildings. Evidence for copper working has been found in the area, perhaps suggesting commercial or industrial activity taking place along the street.

On the eastern side the site, close to the John Lewis car park, a second Roman house has been found. There is evidence for mosaic floors in at least three of its rooms, and one of the mosaic fragments, measuring some 2m by 3m (about a quarter of the original floor) is one of the largest pieces of mosaic pavement found in Leicester in the last 30 years.

Mathew Morris, site director for ULAS, said: "The mosaic is fantastic, it's been a long time since we've found a large, well-preserved mosaic in Leicester. Stylistically, we believe it dates to the early fourth century AD. It would have originally been in a square room in the house. It has a thick border of red tiles surrounding a central square of grey tiles. Picked out in red in the grey square are several decorations, including a geometric border, foliage and a central hexafoil cross. The intricate geometric border follows a pattern known as 'swastika-meander'. The swastika is an ancient symbol found in most world cultures, and it is a common geometrical motif in Roman mosaics, created by laying out the pattern on a repeating grid of 4 by 4 squares. As part of the project, our plan is to lift and conserve it for future display."

Detail of the swastika in the mosaic pavement. Credit: Carl Vivian/ University of Leicester

More curious, however, is a third small Roman building found in the centre of the site. It has a large sunken room or cellar, and it possibly has a small apse (semi-circular niche) attached to one side. Currently, the building has no obvious purpose, but sunken rooms are relatively unusual in the Roman period.

Archaeologists excavate a Roman sunken room, possibly part of a shrine or ornamental garden feature. Some of its walls still survive partially intact. Photo credit: Mathew Morris / University of Leicester

Mathew Morris added: "At the moment there is a lot of speculation about what this building might be. It could be a large hypocaust but we are still investigating. It seems to be tucked away in yards and gardens in the middle of the insula, giving it privacy away from the surrounding streets; and the possible apse is only really big enough to house something like a statue, which makes us wonder if it is something special like a shrine."

Archaeologists will be onsite through February as they investigate the Highcross Street frontage. In the medieval period, the site was occupied by St Johns' Hospital, Leicester earliest hospital founded in the twelfth century, and the town goal, and it is hoped that evidence for both important medieval buildings will found.

A lion-head spout from a Roman Samian ware mortarium (mixing bowl), late 2nd century AD, found during the excavation. Photo credit: Mathew Morris / University of Leicester

Top Image: A reconstruction of what the Vine Street courtyard house might have looked like in the late 3rd century AD. It was discovered during excavations for the John Lewis car park in 2006. Source: Mike Codd

The article, originally titled 'Fantastic mosaic' and home with underfloor heating among new evidence discovered from Leicester's Roman past’ was originally published on Science Daily.

Source: University of Leicester. “Fantastic mosaic' and home with underfloor heating among new evidence discovered from Leicester's Roman past." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 3 February 2017.

Archaeologists have uncovered a fantastic Roman mosaic and evidence of good living over 1,500 years ago in Leicester city centre in a home with underfloor heating.

The team from the University of Leicester is currently excavating a large site on the corner of Highcross Street and Vaughan Way, next to Leicester's John Lewis car park. The project, which has been running since November 2016, is uncovering exciting new evidence for Leicester's Roman past, including evidence for a Roman street, and a Roman house once floored with mosaic pavements.

The excavation is funded by Ingleby, who will be developing the site into apartments, and the team from University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) is working closely with the architects to minimise the impact of the new building on the underlying archaeology. Modern rubble and Victorian garden soil are being removed from the footprint of the proposed building to expose the medieval and Roman archaeology. This allows archaeologists to identify where the footings for the new building will have an adverse effect on important archaeological remains, which can then either be designed around, or excavated before they are destroyed, leaving most of the archaeology preserved intact beneath the new building.

The mosaic floor. ( Carl Vivian / University of Leicester )

The excavation covers nearly two-thirds of a Roman insula (city block), giving archaeologists an amazing opportunity to investigate life in the north-east quarter of the Roman town. So far, a Roman street and three Roman buildings have been identified.

Today, Highcross Street still follows the line of the main road leading from the Roman forum (beneath Jubilee Square) to the north gate, at the junction with Sanvey Gate. On this western side of the site a large Roman building has been uncovered. Two ranges of rooms flanked by a corridor or portico appear to surround a courtyard. At least one room had a hypocaust (underfloor heating), and it is likely that this is a large townhouse, reminiscent of the Vine Street courtyard house excavated nearby, beneath the John Lewis car park, in 2006

A hypocaust (Latin hypocaustum) in the Roman Baths, Bath, UK.

A hypocaust is an ancient Roman system of central heating. The word literally means "heat from below", from the Greek hypo meaning below or underneath, and kaiein, to burn or light a fire. (Ad Meskens/ CC BY SA 3.0 )

North of this building, running east to west across the northern edge of the site, close to All Saints' Church, a cambered gravel street has been recorded. Activity along this street appears to have been quiet during the Roman period. Roadside ditches and boundary walls have been identified, but no substantial buildings are present. Instead, activity seems to be more ephemeral in natured, gardens and yards, probably with some timber buildings. Evidence for copper working has been found in the area, perhaps suggesting commercial or industrial activity taking place along the street.

On the eastern side the site, close to the John Lewis car park, a second Roman house has been found. There is evidence for mosaic floors in at least three of its rooms, and one of the mosaic fragments, measuring some 2m by 3m (about a quarter of the original floor) is one of the largest pieces of mosaic pavement found in Leicester in the last 30 years.

Mathew Morris, site director for ULAS, said: "The mosaic is fantastic, it's been a long time since we've found a large, well-preserved mosaic in Leicester. Stylistically, we believe it dates to the early fourth century AD. It would have originally been in a square room in the house. It has a thick border of red tiles surrounding a central square of grey tiles. Picked out in red in the grey square are several decorations, including a geometric border, foliage and a central hexafoil cross. The intricate geometric border follows a pattern known as 'swastika-meander'. The swastika is an ancient symbol found in most world cultures, and it is a common geometrical motif in Roman mosaics, created by laying out the pattern on a repeating grid of 4 by 4 squares. As part of the project, our plan is to lift and conserve it for future display."

Detail of the swastika in the mosaic pavement. Credit: Carl Vivian/ University of Leicester

More curious, however, is a third small Roman building found in the centre of the site. It has a large sunken room or cellar, and it possibly has a small apse (semi-circular niche) attached to one side. Currently, the building has no obvious purpose, but sunken rooms are relatively unusual in the Roman period.

Archaeologists excavate a Roman sunken room, possibly part of a shrine or ornamental garden feature. Some of its walls still survive partially intact. Photo credit: Mathew Morris / University of Leicester

Mathew Morris added: "At the moment there is a lot of speculation about what this building might be. It could be a large hypocaust but we are still investigating. It seems to be tucked away in yards and gardens in the middle of the insula, giving it privacy away from the surrounding streets; and the possible apse is only really big enough to house something like a statue, which makes us wonder if it is something special like a shrine."

Archaeologists will be onsite through February as they investigate the Highcross Street frontage. In the medieval period, the site was occupied by St Johns' Hospital, Leicester earliest hospital founded in the twelfth century, and the town goal, and it is hoped that evidence for both important medieval buildings will found.

A lion-head spout from a Roman Samian ware mortarium (mixing bowl), late 2nd century AD, found during the excavation. Photo credit: Mathew Morris / University of Leicester

Top Image: A reconstruction of what the Vine Street courtyard house might have looked like in the late 3rd century AD. It was discovered during excavations for the John Lewis car park in 2006. Source: Mike Codd

The article, originally titled 'Fantastic mosaic' and home with underfloor heating among new evidence discovered from Leicester's Roman past’ was originally published on Science Daily.

Source: University of Leicester. “Fantastic mosaic' and home with underfloor heating among new evidence discovered from Leicester's Roman past." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 3 February 2017.

Published on February 10, 2017 02:00

February 9, 2017

Sam’s historical recipe corner: Marlborough pie

History Extra

(© Jessica Hope)

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates marlborough pie – a tasty pie that travelled to America in the 17th century.

English chef Robert May created this apple custard pie when compiling dishes for his 1660 recipe book The Accomplisht Cook.

As the English established colonies in the New World during the 17th century, settlers took the pie recipe with them. Since the 19th century it has become a favourite dessert in the US during holidays such as Thanksgiving.

The original recipe includes equal quantities of egg, apple and dry sherry. I used a modified recipe to ensure the right taste and cooking time.

Ingredients

For the pastry:

• 180g strong bread flour

• 1 tbsp granulated sugar

• ½ tsp table salt

• 125g chilled unsalted butter, cut into cubes

• 3 tbsp ice cold water

For the filling:

• 1½ bramley cooking apples (peeled and grated)

• 3 tbsp lemon juice

• 3 tbsp dry sherry

• 30g salted butter

• 140g granulated sugar

• 3 large eggs

• 240ml single cream

• ¼ tsp ground cinnamon

• ¼ tsp freshly grated nutmeg

• ¼ tsp table salt

Method

Put the flour, salt and sugar in a bowl. Work the butter cubes into the flour with fingers until the mixture looks crumbly. Add water to make dough. Knead the dough on a lightly floured surface until smooth. Roll into a ball and cover in cling film. Refrigerate for 30 mins.

Pie filling: Place the grated apple in a bowl and stir in lemon juice and sherry. Melt the butter in a pan and add apple mixture and sugar. Allow the liquid to boil. Reduce heat and stir until most of the liquid has evaporated. Cool for 10 mins.

Preheat the oven to 200°C. Line a 9 inch pie tin with baking parchment. Roll the dough into a 10 inch circle, 1/8 inch thick. Place in the pie tin and fold excess onto edge of tin to make a crust. Prick the dough and blind bake for 10 mins. Remove weights and parchment and bake for another 5 mins.

Reduce oven temperature to 180°C. Whisk together the eggs, cream, cinnamon, nutmeg and salt, and add apple mixture. Pour the filling into the pastry. Bake for 35 mins until the custard is set but not too brown.

Verdict: The spices really complement the creamy filling.

Difficulty: 5/10

Time: 1 hour 40 mins

Recipe courtesy of KCRW Good Food This article was first published in the October 2015 issue of BBC History Magazine

(© Jessica Hope)

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates marlborough pie – a tasty pie that travelled to America in the 17th century.

English chef Robert May created this apple custard pie when compiling dishes for his 1660 recipe book The Accomplisht Cook.

As the English established colonies in the New World during the 17th century, settlers took the pie recipe with them. Since the 19th century it has become a favourite dessert in the US during holidays such as Thanksgiving.

The original recipe includes equal quantities of egg, apple and dry sherry. I used a modified recipe to ensure the right taste and cooking time.

Ingredients

For the pastry:

• 180g strong bread flour

• 1 tbsp granulated sugar

• ½ tsp table salt

• 125g chilled unsalted butter, cut into cubes

• 3 tbsp ice cold water

For the filling:

• 1½ bramley cooking apples (peeled and grated)

• 3 tbsp lemon juice

• 3 tbsp dry sherry

• 30g salted butter

• 140g granulated sugar

• 3 large eggs

• 240ml single cream

• ¼ tsp ground cinnamon

• ¼ tsp freshly grated nutmeg

• ¼ tsp table salt

Method

Put the flour, salt and sugar in a bowl. Work the butter cubes into the flour with fingers until the mixture looks crumbly. Add water to make dough. Knead the dough on a lightly floured surface until smooth. Roll into a ball and cover in cling film. Refrigerate for 30 mins.

Pie filling: Place the grated apple in a bowl and stir in lemon juice and sherry. Melt the butter in a pan and add apple mixture and sugar. Allow the liquid to boil. Reduce heat and stir until most of the liquid has evaporated. Cool for 10 mins.

Preheat the oven to 200°C. Line a 9 inch pie tin with baking parchment. Roll the dough into a 10 inch circle, 1/8 inch thick. Place in the pie tin and fold excess onto edge of tin to make a crust. Prick the dough and blind bake for 10 mins. Remove weights and parchment and bake for another 5 mins.

Reduce oven temperature to 180°C. Whisk together the eggs, cream, cinnamon, nutmeg and salt, and add apple mixture. Pour the filling into the pastry. Bake for 35 mins until the custard is set but not too brown.

Verdict: The spices really complement the creamy filling.

Difficulty: 5/10

Time: 1 hour 40 mins

Recipe courtesy of KCRW Good Food This article was first published in the October 2015 issue of BBC History Magazine

Published on February 09, 2017 02:00

February 8, 2017

Sam's historical recipe corner: Tudor vegetable pie

History Extra

The Tudors loved pastry, from the high-status venison pasty to this meat-free pie.

This 1596 recipe for a “pie of bald meats [greens] for fish days” was handy for times such as Lent or Fridays when the church forbade the eating of meat (another similar recipe is called simply Friday Pie). Medieval pastry was a disposable cooking vessel, but in the 1580s there were great advancements in pastry work. Pies became popular, with many pastry types, shapes and patterns filled with everything from lobster to strawberries. This pie’s sweet/savoury combo is typical of Tudor cookery: I enjoyed it, but was glad I’d reduced the sugar content.

Ingredients

• Pastry: 1lb plain flour, 5oz butter, 1 egg

• 8oz mixture of spinach, lettuce, cabbage, chard

• 2oz raisins, chopped

• 1oz grated hard cheese

• 2oz fresh bread crumbs

• ½ tsp salt

• ½ tsp cinnamon

• 1 tbsp sugar (I used 1 tsp)

• 3 raw egg yolks • 1 hard-boiled egg yolk

• 1oz melted butter

Method

To make the pastry, rub the butter into the flour, work in egg and water, and knead lightly. Use half to line a dish; I used a 10-inch metal flan dish. Remove the coarse stalks of the greens, shred leaves thinly, mix with other ingredients (I also added black pepper) and pack into the dish. Cover with pastry, keeping some back to make decorations for the top. Bake at 150°C for 50 mins (mine took an hour), brushing the top with a little butter and sprinkling on a little fine sugar before serving.

Difficulty: 4/10

Time: 1 hour 30 mins

Verdict: The pastry handled well and the pie was tasty. It made a good summer lunch, served with pickles. I’ll make it again, but this time minus the sugar sprinkled on top. From a recipe in Cooking and Dining in Tudor & Early Stuart England by Peter Brears (Prospect, 2015).

This recipe was published in the May 2016 issue of BBC History Magazine.

The Tudors loved pastry, from the high-status venison pasty to this meat-free pie.

This 1596 recipe for a “pie of bald meats [greens] for fish days” was handy for times such as Lent or Fridays when the church forbade the eating of meat (another similar recipe is called simply Friday Pie). Medieval pastry was a disposable cooking vessel, but in the 1580s there were great advancements in pastry work. Pies became popular, with many pastry types, shapes and patterns filled with everything from lobster to strawberries. This pie’s sweet/savoury combo is typical of Tudor cookery: I enjoyed it, but was glad I’d reduced the sugar content.

Ingredients

• Pastry: 1lb plain flour, 5oz butter, 1 egg

• 8oz mixture of spinach, lettuce, cabbage, chard

• 2oz raisins, chopped

• 1oz grated hard cheese

• 2oz fresh bread crumbs

• ½ tsp salt

• ½ tsp cinnamon

• 1 tbsp sugar (I used 1 tsp)

• 3 raw egg yolks • 1 hard-boiled egg yolk

• 1oz melted butter

Method

To make the pastry, rub the butter into the flour, work in egg and water, and knead lightly. Use half to line a dish; I used a 10-inch metal flan dish. Remove the coarse stalks of the greens, shred leaves thinly, mix with other ingredients (I also added black pepper) and pack into the dish. Cover with pastry, keeping some back to make decorations for the top. Bake at 150°C for 50 mins (mine took an hour), brushing the top with a little butter and sprinkling on a little fine sugar before serving.

Difficulty: 4/10

Time: 1 hour 30 mins

Verdict: The pastry handled well and the pie was tasty. It made a good summer lunch, served with pickles. I’ll make it again, but this time minus the sugar sprinkled on top. From a recipe in Cooking and Dining in Tudor & Early Stuart England by Peter Brears (Prospect, 2015).

This recipe was published in the May 2016 issue of BBC History Magazine.

Published on February 08, 2017 02:00