MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 70

January 9, 2017

Bleddyn ap Cynfyn: the first Prince of Wales?

History Extra

Many of us will have heard of Llewelyn the Last, seated to the right of Edward I in this picture. But who was the first Prince of Wales? (Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

As highlighted by the recent 950th anniversary of the Norman conquest of England, in 1066 there was much more going on in Britain than a simple clash between King Harold’s Anglo-Saxons and Duke William’s Normans. As a Welsh historian, it is hard not to conclude that many of the crucial pieces of the jigsaw remain left out of the picture of that epochal year. The third quarter of the 11th century was arguably one of the most formative and dramatic in the entire history of Wales, with events west of the rivers Severn and Dee impacting enormously on those in England and beyond. When the Normans arrived on the Welsh border they would be met by a leader who, I would argue, can be called the first prince of Wales – Bleddyn ap Cynfyn. Yet despite being one of Wales’s greatest leaders, Bleddyn has until now been all but forgotten.

The years before Bleddyn’s accession in 1063 had seen Wales rise to an unprecedented position of power and unity, all achieved under the direction of one man: Bleddyn’s half-brother, Gruffudd ap Llywelyn – the first, last and only king of all the lands of modern-day Wales. His story also remains little known, even in his own country; the BBC’s 2012 Story of Wales TV series managed to leap straight from 950 to 1066, entirely missing the reign of the country’s greatest ruler.

A united Wales

Gruffudd united all the territories that comprise modern Wales, conquered land across the border that had been in English hands for centuries, forged alliances with key Anglo-Saxon dynasties and even turned the Viking threat to his realm into a powerful weapon. In 1055, Gruffudd led a great army and fleet against the English border, crushing its defenders, burning Hereford and forcing Edward the Confessor to recognise his status as an sub-king within the British Isles. Having emerged as a war leader, Gruffudd would also prove to be a patron of the arts and the church. He had all the trappings of a king, including impressive wealth, courts throughout the country, professional ministers, a powerful household and a strong naval presence. At the height of his powers, he was described by a native source as “King Gruffudd, sole and pre-eminent ruler of the British.” His status was also recognised in England, Ireland and on the continent.

The key to Gruffudd’s success on such a broad stage was his unshakeable alliance with Earl Ælfgar of Mercia, which had been made in reaction to the growing power and influence of the Godwine dynasty. Godwine (d1053) had risen to prominence as the earl of Wessex, a position of influence that would allow his sons to dominate the English political scene. The strength of Wales, Mercia and their Hiberno-Scandinavian allies was set against that of Harold, the son of Godwine, and his brother Tostig, the earl of Northumbria. If such a balance of power was maintained, it seems certain that Harold’s path to the English throne would have been blocked, with the compromise candidate Edgar Ætheling ‒ the last male member of the ancient Anglo-Saxon royal line ‒ the likely successor. But Earl Ælfgar’s eldest son and intended heir, Burgheard, died in 1061, and the earl himself passed away the following year. The defence offered by a strong and friendly Mercia was therefore removed from Wales’ eastern border, and the resultant weakness gave Harold the window of opportunity he needed.

Two great brothers of a cloud-born land

Gruffudd’s power did not sit well with many of the conquered localities of Wales – lands formerly ruled by men who still considered themselves kings. With the help of such men, Harold rolled back Gruffudd’s achievements in the south, while his brother Tostig advanced along the north Wales coast. The brothers engaged the Welsh king in a bloody campaign in the wildest depths of north Wales and were lauded as: “two great brothers of a cloud-born land, the kingdom’s sacred oaks, two Hercules”. Gerald of Wales later recounted how: “[Harold] advanced into Wales on foot, at the head of his lightly clad infantry, lived on the country, and marched up and down and round and about the whole of Wales with such energy that he ‘left not one that pisseth against a wall’”.

Gruffudd was deserted by his allies then betrayed by his closest household troops, his head cut off and delivered to Harold. Among those who had deserted Gruffudd were his half-brothers, Bleddyn and Rhiwallon. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded that in 1063: “King Edward entrusted the country to the two brothers of Gruffudd, Bleddyn and Rhiwallon, and they swore oaths and gave hostages to the king and the earl [Harold], promising that they would be faithful to him in everything, and be everywhere ready on water and on land, and likewise would pay such dues from that country as had been given before to any other king”.

The contrast with the peace treaty that Gruffudd had forced on Edward could not have been more marked, and was accompanied by major land losses for Wales in the east. But the brothers had control of much of north and mid-Wales. They retained ambitions to overlordship of the south and would soon look to recreate Gruffudd’s vital alliance with Mercia – reestablishing the kingdom of Wales was always their ambition.

The chance to throw off the shackles of Godwine dominance came in 1065, the Welsh leaders being part of a wider, co-ordinated movement throughout northern and western England against Harold and Tostig. The Welsh raided into Herefordshire and provided large numbers of troops to join the Mercian and Northumbrian opposition to the Godwines, which was led by Ælfgar’s young sons, Edwin and Morcar.

It was this alliance that forced Harold to abandon his brother Tostig and send him into exile, instead agreeing a political marriage with Gruffudd’s widow, Ealdgyth, the sister of Edwin and Morcar. Edward the Confessor suffered a stroke that sent him to an early grave and was succeeded by Harold, whose compromise deal with the house of Mercia had cleared his path to the throne.

The coronation of King Harold II (c1020-66) whose rule saw invasions by his brother, Tostig, Harald Hardrada and William the Conqueror in 1066. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Bleddyn and the divided realm

Even so, it was a divided realm – a situation that led to the 1066 invasions of Tostig, Harald Hardrada and William the Conqueror. Any support the house of Mercia gave to Harold was, at best, half-hearted; Edwin and Morcar seemed to want to play a long game. They played no part at Hastings and, after Harold’s death, the pregnant Ealdgyth was kept in safety at Chester while Edwin hoped to marry the Conqueror’s daughter.

William, though, had other plans for the house of Mercia. Professor Stephen Baxter (University of Oxford) has highlighted how in the succeeding years Edwin and Morcar: “lacked influence and credibility at court; lost territory and property to rival earls; were unable to exercise meaningful power within their earldoms; and failed to hold their family’s network of patronage and lordship together”. The men of earls Edwin and Morcar, famously led by Eadric ‘the Wild’, met the Normans with fierce resistance, which was supported by Bleddyn and Rhiwallon from the outset.

The Welsh were at Eadric’s side in major operations against the Normans in Herefordshire, Shropshire and Cheshire. At the same time, they faced trouble in Wales from their nephews, the sons of Gruffudd, who may have won Norman support. At the battle of Mechain in 1069, Bleddyn was able to kill the sons of Gruffudd, but lost his brother in the same clash. Around the same time, William’s harrying of the north and his march on Chester finally shattered the Anglo-Saxon resistance in northern and western England, meaning the end of the house of Mercia. When Edwin was killed by his own men shortly afterwards, he was said to be still desperately reaching out to his Welsh allies for support.

Eadric submitted to the Normans at this time and it was likely that he was joined by his ally, Bleddyn. The Welsh leader needed a new accord to secure his eastern border and planned to achieve this by switching from hostility to the Normans to accommodation with them. As part of the peace deal, Bleddyn married his niece – Gruffudd and Ealdgyth’s daughter, Nest – to his former enemy Osbern fitz Richard. He also accepted the new Norman castle at Montgomery (Hen Domen), while his son-in-law and ally from south-east Wales – Caradog ap Gruffudd – secured friendly relations with the Normans of Herefordshire.

If such actions meant compromise on Bleddyn’s eastern border, it left him in a dominant position in Wales, and he used Norman military help to pursue his ambitions at the expense of the dynasty of Deheubarth (south-west Wales). It was perhaps to secure recognition of this dominance that in 1075, Bleddyn headed into the heartlands of the Deheubarth dynasty in the Tywi valley. According to one version of the Welsh chronicle: “And then Bleddyn ap Cynfyn was slain by Rhys ab Owain through the treachery of the evil-spirited rulers and chief men of Ystrad Tywi – the man who, after Gruffudd, his brother, eminently held the whole kingdom of the Britons”.

A kingdom in confusion In the succeeding years, Wales was riven apart by a series of horrific civil wars that bewildered and confused both contemporary observers and future historians. This destroyed any remaining vestige of a kingdom of Wales and, in the power vacuum that was created, the Normans moved in. The tone taken by English and continental sources in dealing with Welsh nobles became increasingly patronising – a reflection of growing imperial outlooks and of a very real reduction in the power of Welsh leaders.

The surviving Welsh dynasties slowly regrouped in the 12th century, notably in Gwynedd. Men such as Owain Gwynedd (c1100–70), and his 13th-century descendants, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, would revive the ambition to rule all of Wales. By their day, though, most of the richest lowlands in the south-east and south-west of the country had been irretrievably lost, while eastern border conquests on the scale that Gruffudd ap Llywelyn had made were never a realistic possibility.

Llywelyn Ap Gruffydd was one who challenged to rule all of Wales, though he was defeated by English King Edward I in 1282, to whom he refused to pay homage. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In these straitened circumstances, and with outside observers ridiculing the status of Welsh kings, ambitious native nobles adopted the novel title of ‘prince’ (tywysog in Welsh, princeps in Latin) in order to set them above their fellow ‘kings’. The princes saw all the native lords of Wales as their tenants, but inherent in their plan was the direct feudal lordship of the king of England over the prince of Wales, leaving it clear that the “kingship of the Britons” was to be sought in London, not in the west of the country. The fact that the 13th-century principality of Gwynedd was a part of the kingdom of England and its leader one of the king’s magnates was acknowledged by all.

Bleddyn was unlikely to ever have settled for such a formal acknowledgement of subservience to the English king; he challenged the 1063 settlement that was imposed on him at the earliest opportunity and sought the much more loosely defined position of sub-king within Britain that had been won by Gruffudd. But the political realities that would frame the creation of the principality of Wales had been forged in the reign of Bleddyn, and the extent of his rule looks much more like that of the rulers who would follow him than like that of the king of Wales who preceded him.

In contrast to Gruffudd, Bleddyn was never able to impose his direct rule on south-east Wales and did not rule north-east Wales. The loss of some of Wales’ richest territories on the eastern borders impacted on the ability of Welsh leaders to maintain an effective naval presence, and this in turn further restricted their chances of imposing a wider dominion on the country. A lack of naval power hamstrung Bleddyn’s attempts to exert overlordship in Deheubarth and encouraged interference from across the Irish Sea – an outside threat that had been negated in Gruffudd’s later years. While Bleddyn ruled Ceredigion for some, if not all, of his reign, his power in other parts of Deheubarth (such as Ystrad Tywi) was at best theoretical, at worst non-existent.

Native and external commentators were aware that a change had taken place. Sources outside the country were either reluctant to call Bleddyn king, or failed to mention him at all. Within Wales, some versions of the native chronicle accorded Bleddyn the important title of “King of the Britons”, but stressed that he was inferior to Gruffudd. The ultimate irony for the man who would have been king is that he can be described as the country’s first prince.

Dr Sean Davies is author of The First Prince of Wales? Bleddyn ap Cynfyn, 1063–75 (University of Wales Press, 2016).

A timeline of Bleddyn ap Cynfyn 1062 Death of Earl Ælfgar of Mercia, the ally of King Gruffudd ap Llywelyn of Wales

1063 Harold and Tostig, the sons of Godwine, conquer Wales Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, the only king to ever rule all of Wales, is killed Bleddyn and his brother Rhiwallon succeed to rule in Wales, with Harold’s consent

1065 Mercia, Northumbria and the Welsh rulers rise against the Godwine domination Tostig is exiled, but a compromise deal is agreed with Harold

1066 Edward the Confessor dies, Harold succeeds to the throne Tostig and Harald Hardrada invade in the north Battles of Fulford and Stamford Bridge Duke William invades in the south leading to the battle of Hastings and the death of Harold Surviving Anglo-Saxon nobles submit to William

1067‒70 Resistance to Norman rule throughout England Bleddyn and Rhiwallon support Eadric the Wild and the Mercian rebels 1069 Bleddyn wins the battle of Mechain but loses his brother Rhiwallon in the fight

1070 Widespread submission of Anglo-Saxon rebels to Norman rule Bleddyn agrees peace deals with Normans on Wales’ eastern border

1070‒75 Bleddyn uses his alliances to pursue his ambitions against rivals in south-west Wales 1075 Bleddyn ‘treacherously’ killed by Rhys ab Owain in the Tywi valley

1075‒81 Wales torn apart in the civil wars that followed the slaying of Bleddyn, allowing major Norman advances in the country

Many of us will have heard of Llewelyn the Last, seated to the right of Edward I in this picture. But who was the first Prince of Wales? (Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

As highlighted by the recent 950th anniversary of the Norman conquest of England, in 1066 there was much more going on in Britain than a simple clash between King Harold’s Anglo-Saxons and Duke William’s Normans. As a Welsh historian, it is hard not to conclude that many of the crucial pieces of the jigsaw remain left out of the picture of that epochal year. The third quarter of the 11th century was arguably one of the most formative and dramatic in the entire history of Wales, with events west of the rivers Severn and Dee impacting enormously on those in England and beyond. When the Normans arrived on the Welsh border they would be met by a leader who, I would argue, can be called the first prince of Wales – Bleddyn ap Cynfyn. Yet despite being one of Wales’s greatest leaders, Bleddyn has until now been all but forgotten.

The years before Bleddyn’s accession in 1063 had seen Wales rise to an unprecedented position of power and unity, all achieved under the direction of one man: Bleddyn’s half-brother, Gruffudd ap Llywelyn – the first, last and only king of all the lands of modern-day Wales. His story also remains little known, even in his own country; the BBC’s 2012 Story of Wales TV series managed to leap straight from 950 to 1066, entirely missing the reign of the country’s greatest ruler.

A united Wales

Gruffudd united all the territories that comprise modern Wales, conquered land across the border that had been in English hands for centuries, forged alliances with key Anglo-Saxon dynasties and even turned the Viking threat to his realm into a powerful weapon. In 1055, Gruffudd led a great army and fleet against the English border, crushing its defenders, burning Hereford and forcing Edward the Confessor to recognise his status as an sub-king within the British Isles. Having emerged as a war leader, Gruffudd would also prove to be a patron of the arts and the church. He had all the trappings of a king, including impressive wealth, courts throughout the country, professional ministers, a powerful household and a strong naval presence. At the height of his powers, he was described by a native source as “King Gruffudd, sole and pre-eminent ruler of the British.” His status was also recognised in England, Ireland and on the continent.

The key to Gruffudd’s success on such a broad stage was his unshakeable alliance with Earl Ælfgar of Mercia, which had been made in reaction to the growing power and influence of the Godwine dynasty. Godwine (d1053) had risen to prominence as the earl of Wessex, a position of influence that would allow his sons to dominate the English political scene. The strength of Wales, Mercia and their Hiberno-Scandinavian allies was set against that of Harold, the son of Godwine, and his brother Tostig, the earl of Northumbria. If such a balance of power was maintained, it seems certain that Harold’s path to the English throne would have been blocked, with the compromise candidate Edgar Ætheling ‒ the last male member of the ancient Anglo-Saxon royal line ‒ the likely successor. But Earl Ælfgar’s eldest son and intended heir, Burgheard, died in 1061, and the earl himself passed away the following year. The defence offered by a strong and friendly Mercia was therefore removed from Wales’ eastern border, and the resultant weakness gave Harold the window of opportunity he needed.

Two great brothers of a cloud-born land

Gruffudd’s power did not sit well with many of the conquered localities of Wales – lands formerly ruled by men who still considered themselves kings. With the help of such men, Harold rolled back Gruffudd’s achievements in the south, while his brother Tostig advanced along the north Wales coast. The brothers engaged the Welsh king in a bloody campaign in the wildest depths of north Wales and were lauded as: “two great brothers of a cloud-born land, the kingdom’s sacred oaks, two Hercules”. Gerald of Wales later recounted how: “[Harold] advanced into Wales on foot, at the head of his lightly clad infantry, lived on the country, and marched up and down and round and about the whole of Wales with such energy that he ‘left not one that pisseth against a wall’”.

Gruffudd was deserted by his allies then betrayed by his closest household troops, his head cut off and delivered to Harold. Among those who had deserted Gruffudd were his half-brothers, Bleddyn and Rhiwallon. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded that in 1063: “King Edward entrusted the country to the two brothers of Gruffudd, Bleddyn and Rhiwallon, and they swore oaths and gave hostages to the king and the earl [Harold], promising that they would be faithful to him in everything, and be everywhere ready on water and on land, and likewise would pay such dues from that country as had been given before to any other king”.

The contrast with the peace treaty that Gruffudd had forced on Edward could not have been more marked, and was accompanied by major land losses for Wales in the east. But the brothers had control of much of north and mid-Wales. They retained ambitions to overlordship of the south and would soon look to recreate Gruffudd’s vital alliance with Mercia – reestablishing the kingdom of Wales was always their ambition.

The chance to throw off the shackles of Godwine dominance came in 1065, the Welsh leaders being part of a wider, co-ordinated movement throughout northern and western England against Harold and Tostig. The Welsh raided into Herefordshire and provided large numbers of troops to join the Mercian and Northumbrian opposition to the Godwines, which was led by Ælfgar’s young sons, Edwin and Morcar.

It was this alliance that forced Harold to abandon his brother Tostig and send him into exile, instead agreeing a political marriage with Gruffudd’s widow, Ealdgyth, the sister of Edwin and Morcar. Edward the Confessor suffered a stroke that sent him to an early grave and was succeeded by Harold, whose compromise deal with the house of Mercia had cleared his path to the throne.

The coronation of King Harold II (c1020-66) whose rule saw invasions by his brother, Tostig, Harald Hardrada and William the Conqueror in 1066. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Bleddyn and the divided realm

Even so, it was a divided realm – a situation that led to the 1066 invasions of Tostig, Harald Hardrada and William the Conqueror. Any support the house of Mercia gave to Harold was, at best, half-hearted; Edwin and Morcar seemed to want to play a long game. They played no part at Hastings and, after Harold’s death, the pregnant Ealdgyth was kept in safety at Chester while Edwin hoped to marry the Conqueror’s daughter.

William, though, had other plans for the house of Mercia. Professor Stephen Baxter (University of Oxford) has highlighted how in the succeeding years Edwin and Morcar: “lacked influence and credibility at court; lost territory and property to rival earls; were unable to exercise meaningful power within their earldoms; and failed to hold their family’s network of patronage and lordship together”. The men of earls Edwin and Morcar, famously led by Eadric ‘the Wild’, met the Normans with fierce resistance, which was supported by Bleddyn and Rhiwallon from the outset.

The Welsh were at Eadric’s side in major operations against the Normans in Herefordshire, Shropshire and Cheshire. At the same time, they faced trouble in Wales from their nephews, the sons of Gruffudd, who may have won Norman support. At the battle of Mechain in 1069, Bleddyn was able to kill the sons of Gruffudd, but lost his brother in the same clash. Around the same time, William’s harrying of the north and his march on Chester finally shattered the Anglo-Saxon resistance in northern and western England, meaning the end of the house of Mercia. When Edwin was killed by his own men shortly afterwards, he was said to be still desperately reaching out to his Welsh allies for support.

Eadric submitted to the Normans at this time and it was likely that he was joined by his ally, Bleddyn. The Welsh leader needed a new accord to secure his eastern border and planned to achieve this by switching from hostility to the Normans to accommodation with them. As part of the peace deal, Bleddyn married his niece – Gruffudd and Ealdgyth’s daughter, Nest – to his former enemy Osbern fitz Richard. He also accepted the new Norman castle at Montgomery (Hen Domen), while his son-in-law and ally from south-east Wales – Caradog ap Gruffudd – secured friendly relations with the Normans of Herefordshire.

If such actions meant compromise on Bleddyn’s eastern border, it left him in a dominant position in Wales, and he used Norman military help to pursue his ambitions at the expense of the dynasty of Deheubarth (south-west Wales). It was perhaps to secure recognition of this dominance that in 1075, Bleddyn headed into the heartlands of the Deheubarth dynasty in the Tywi valley. According to one version of the Welsh chronicle: “And then Bleddyn ap Cynfyn was slain by Rhys ab Owain through the treachery of the evil-spirited rulers and chief men of Ystrad Tywi – the man who, after Gruffudd, his brother, eminently held the whole kingdom of the Britons”.

A kingdom in confusion In the succeeding years, Wales was riven apart by a series of horrific civil wars that bewildered and confused both contemporary observers and future historians. This destroyed any remaining vestige of a kingdom of Wales and, in the power vacuum that was created, the Normans moved in. The tone taken by English and continental sources in dealing with Welsh nobles became increasingly patronising – a reflection of growing imperial outlooks and of a very real reduction in the power of Welsh leaders.

The surviving Welsh dynasties slowly regrouped in the 12th century, notably in Gwynedd. Men such as Owain Gwynedd (c1100–70), and his 13th-century descendants, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, would revive the ambition to rule all of Wales. By their day, though, most of the richest lowlands in the south-east and south-west of the country had been irretrievably lost, while eastern border conquests on the scale that Gruffudd ap Llywelyn had made were never a realistic possibility.

Llywelyn Ap Gruffydd was one who challenged to rule all of Wales, though he was defeated by English King Edward I in 1282, to whom he refused to pay homage. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In these straitened circumstances, and with outside observers ridiculing the status of Welsh kings, ambitious native nobles adopted the novel title of ‘prince’ (tywysog in Welsh, princeps in Latin) in order to set them above their fellow ‘kings’. The princes saw all the native lords of Wales as their tenants, but inherent in their plan was the direct feudal lordship of the king of England over the prince of Wales, leaving it clear that the “kingship of the Britons” was to be sought in London, not in the west of the country. The fact that the 13th-century principality of Gwynedd was a part of the kingdom of England and its leader one of the king’s magnates was acknowledged by all.

Bleddyn was unlikely to ever have settled for such a formal acknowledgement of subservience to the English king; he challenged the 1063 settlement that was imposed on him at the earliest opportunity and sought the much more loosely defined position of sub-king within Britain that had been won by Gruffudd. But the political realities that would frame the creation of the principality of Wales had been forged in the reign of Bleddyn, and the extent of his rule looks much more like that of the rulers who would follow him than like that of the king of Wales who preceded him.

In contrast to Gruffudd, Bleddyn was never able to impose his direct rule on south-east Wales and did not rule north-east Wales. The loss of some of Wales’ richest territories on the eastern borders impacted on the ability of Welsh leaders to maintain an effective naval presence, and this in turn further restricted their chances of imposing a wider dominion on the country. A lack of naval power hamstrung Bleddyn’s attempts to exert overlordship in Deheubarth and encouraged interference from across the Irish Sea – an outside threat that had been negated in Gruffudd’s later years. While Bleddyn ruled Ceredigion for some, if not all, of his reign, his power in other parts of Deheubarth (such as Ystrad Tywi) was at best theoretical, at worst non-existent.

Native and external commentators were aware that a change had taken place. Sources outside the country were either reluctant to call Bleddyn king, or failed to mention him at all. Within Wales, some versions of the native chronicle accorded Bleddyn the important title of “King of the Britons”, but stressed that he was inferior to Gruffudd. The ultimate irony for the man who would have been king is that he can be described as the country’s first prince.

Dr Sean Davies is author of The First Prince of Wales? Bleddyn ap Cynfyn, 1063–75 (University of Wales Press, 2016).

A timeline of Bleddyn ap Cynfyn 1062 Death of Earl Ælfgar of Mercia, the ally of King Gruffudd ap Llywelyn of Wales

1063 Harold and Tostig, the sons of Godwine, conquer Wales Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, the only king to ever rule all of Wales, is killed Bleddyn and his brother Rhiwallon succeed to rule in Wales, with Harold’s consent

1065 Mercia, Northumbria and the Welsh rulers rise against the Godwine domination Tostig is exiled, but a compromise deal is agreed with Harold

1066 Edward the Confessor dies, Harold succeeds to the throne Tostig and Harald Hardrada invade in the north Battles of Fulford and Stamford Bridge Duke William invades in the south leading to the battle of Hastings and the death of Harold Surviving Anglo-Saxon nobles submit to William

1067‒70 Resistance to Norman rule throughout England Bleddyn and Rhiwallon support Eadric the Wild and the Mercian rebels 1069 Bleddyn wins the battle of Mechain but loses his brother Rhiwallon in the fight

1070 Widespread submission of Anglo-Saxon rebels to Norman rule Bleddyn agrees peace deals with Normans on Wales’ eastern border

1070‒75 Bleddyn uses his alliances to pursue his ambitions against rivals in south-west Wales 1075 Bleddyn ‘treacherously’ killed by Rhys ab Owain in the Tywi valley

1075‒81 Wales torn apart in the civil wars that followed the slaying of Bleddyn, allowing major Norman advances in the country

Published on January 09, 2017 01:30

January 8, 2017

10 things you (probably) didn’t know about the Anglo-Saxons

History Extra

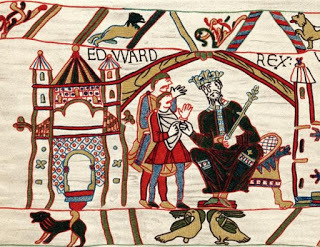

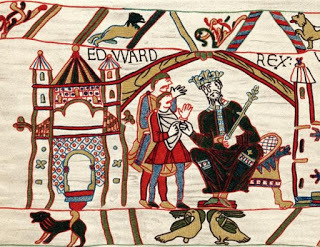

Edward The Confessor, Anglo-Saxon king of England. From the Bayeux Tapestry, which tells the story of the events leading to the 1066 battle of Hastings. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

1) The Anglo-Saxons were immigrants

The people we call Anglo-Saxons were actually immigrants from northern Germany and southern Scandinavia. Bede, a monk from Northumbria writing some centuries later, says that they were from some of the most powerful and warlike tribes in Germany. Bede names three of these tribes: the Angles, Saxons and Jutes. There were probably many other peoples who set out for Britain in the early fifth century, however. Batavians, Franks and Frisians are known to have made the sea crossing to the stricken province of ‘Britannia’. The collapse of the Roman empire was one of the greatest catastrophes in history. Britain, or ‘Britannia’, had never been entirely subdued by the Romans. In the far north – what they called Caledonia (modern Scotland) – there were tribes who defied the Romans, especially the Picts. The Romans built a great barrier, Hadrian’s Wall, to keep them out of the civilised and prosperous part of Britain. As soon as Roman power began to wane, these defences were degraded, and in AD 367 the Picts smashed through them. Gildas, a British historian, says that Saxon war-bands were hired to defend Britain when the Roman army had left. So the Anglo-Saxons were invited immigrants, according to this theory, a bit like the immigrants from the former colonies of the British empire in the period after 1945.

2) The Anglo-Saxons murdered their hosts at a conference

Britain was under sustained attack from the Picts in the north and the Irish in the west. The British appointed a ‘head man’, Vortigern, whose name may actually be a title meaning just that – to act as a kind of national dictator. It is possible that Vortigern was the son-in-law of Magnus Maximus, a usurper emperor who had operated from Britain before the Romans left. Vortigern’s recruitment of the Saxons ended in disaster for Britain. At a conference between the nobles of the Britons and Anglo-Saxons, [likely in AD 472, although some sources say AD 463] the latter suddenly produced concealed knives and stabbed their opposite numbers from Britain in the back.

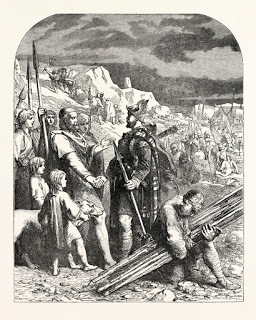

Treaty of Hengist and Horsa with Vortigern. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

Vortigern was deliberately spared in this ‘treachery of the long-knives’, but was forced to cede large parts of south-eastern Britain to them. Vortigern was now a powerless puppet of the Saxons.

3) The Britons rallied under a mysterious leader

The Angles, Saxons, Jutes and other incomers burst out of their enclave in the south-east in the mid-fifth century and set all southern Britain ablaze. Gildas, our closest witness, says that in this emergency a new British leader emerged, called Ambrosius Aurelianus in the late 440s and early 450s. It has been postulated that Ambrosius was from the rich villa economy around Gloucestershire, but we simply do not know for sure. Amesbury in Wiltshire is named after him and may have been his campaign headquarters. A great battle took place, supposedly sometime around AD 500, at a place called Mons Badonicus or Mount Badon, probably somewhere in the south-west of modern England. The Saxons were resoundingly defeated by the Britons, but frustratingly we don’t know much more than that. A later Welsh source says that the victor was ‘Arthur’ but it was written down hundreds of years after the event, when it may have become contaminated by later folk-myths of such a person. Gildas does not mention Arthur, and this seems strange, but there are many theories about this seeming anomaly. One is that Gildas did refer to him in a sort of acrostic code, which reveals him to be a chieftain from Gwent called Cuneglas. Gildas called Cuneglas ‘the bear’, and Arthur means ‘bear’. Nevertheless, for the time being the Anglo-Saxon advance had been checked by someone, possibly Arthur.

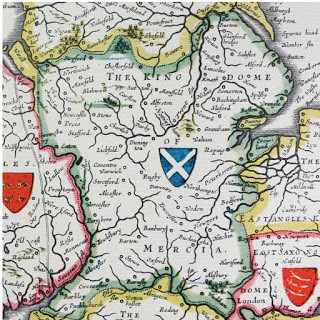

4) Seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms emerged

‘England’ as a country did not come into existence for hundreds of years after the Anglo-Saxons arrived. Instead, seven major kingdoms were carved out of the conquered areas: Northumbria, East Anglia, Essex, Sussex, Kent, Wessex and Mercia. All these nations were fiercely independent, and although they shared similar languages, pagan religions, and socio-economic and cultural ties, they were absolutely loyal to their own kings and very competitive, especially in their favourite pastime – war.

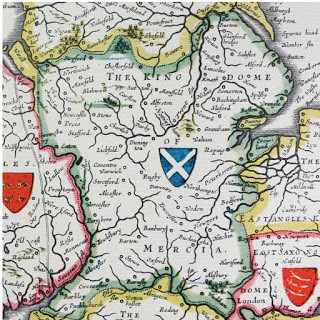

Shield of Mercia, from the Heptarchy; a collective name applied to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of south, east, and central England during late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. Detail from an antique map of Britain by the Dutch cartographer Willem Blaeu in Atlas Novus (Amsterdam, 1635). (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

At first they were pre-occupied fighting the Britons (or ‘Welsh’, as they called them), but as soon as they had consolidated their power-centres they immediately commenced armed conflict with each other. Woden, one of their chief gods, was especially associated with war, and this military fanaticism was the chief diversion of the kings and nobles. Indeed, tales of the deeds of warriors, or their boasts of what heroics they would perform in battle, was the main form of entertainment, and obsessed the entire community – much like football today.

5) A fearsome warrior plundered his neighbours

The ‘heptarchy’, or seven kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons, all aspired to dominate the others. One reason for this was that the dominant king could exact tribute (a sort of tax, but paid in gold and silver bullion), gemstones, cattle, horses or elite weapons. A money economy did not yet exist. Eventually a leader from Mercia in the English Midlands became the most feared of all these warrior-kings: Penda, who ruled from AD 626 until 655. He personally killed many of his rivals in battle, and as one of the last pagan Anglo-Saxon kings he offered up the body of one of them, King Oswald of Northumbria, to Woden. Penda ransacked many of the other Anglo-Saxon realms, amassing vast and exquisite treasures as tribute and the discarded war-gear of fallen warriors on the battlefields. This is just the sort of elite military kit that comprises the Staffordshire Hoard, discovered in 2009. Although a definite connection is elusive, the hoard typifies the warlike atmosphere of the mid-seventh century, and the unique importance in Anglo-Saxon society of male warrior elites.

6) An African refugee helped reform the English church

The Britons were Christians, but were now cut off from Rome, but the Anglo-Saxons remained pagan. In AD 597 St Augustine had been sent to Kent by Pope Gregory the Great to convert the Anglo-Saxons. It was a tall order for his tiny mission, but gradually the seven kingdoms did convert, and became exemplary Christians – so much so that they converted their old tribal homelands in Germany.

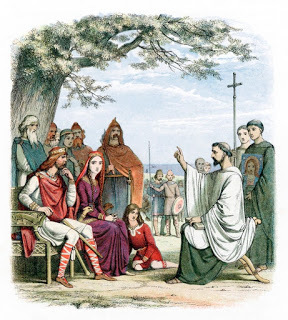

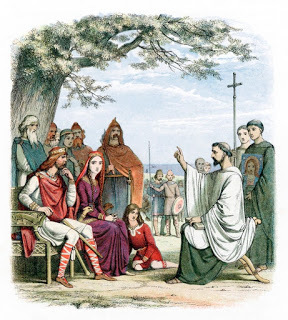

St Augustine of Canterbury, who was sent by Pope Gregory to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. St Augustine is seen here preaching before Ethelbert, Anglo-Saxon King of Kent. Augustine was the first Archbishop of Canterbury. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

One reason why they converted was because the church said that the Christian God would deliver them victory in battles. When this failed to materialise, some Anglo-Saxon kings became apostate, and a different approach was required. The man chosen for the task was an elderly Greek named Theodore of Tarsus, but he was not the pope’s first choice. Instead he had offered the job to a younger man, Hadrian ‘the African’, a Berber refugee from north Africa, but Hadrian objected that he was too young. The truth was that people in the civilised south of Europe dreaded the idea of going to England, which was considered barbaric and had a terrible reputation. The pope decided to send both men, to keep each other company on the long journey. After more than a year (and many adventures) they arrived, and set to work to reform the English church. Theodore lived to be 88, a grand old age for those days, and Hadrian, the young man who had fled from his home in north Africa, outlived him, and continued to devote himself to his task until his death in AD 710.

7) Alfred the Great had a crippling disability

When we look up at the statue of King Alfred of Wessex in Winchester, we are confronted by an image of our national ‘superhero’: the valiant defender of a Christian realm against the heathen Viking marauders. There is no doubt that Alfred fully deserves this accolade as ‘England’s darling’, but there was another side to him that is less well known. Alfred never expected to be king – he had three older brothers – but when he was four years old on a visit to Rome the pope seemed to have granted him special favour when his father presented him to the pontiff. As he grew up, Alfred was constantly troubled by illness, including irritating and painful piles – a real problem in an age where a prince was constantly in the saddle. Asser, the Welshman who became his biographer, relates that Alfred suffered from another painful, draining malady that is not specified. Some people believe it was Crohn’s Disease, others that it may have been a sexually transmitted disease, or even severe depression. The truth is we don’t know exactly what Alfred’s mystery ailment was. Whatever it was, it is incredible to think that Alfred’s extraordinary achievements were accomplished in the face of a daily struggle with debilitating and chronic illness.

8) An Anglo-Saxon king was finally buried in 1984

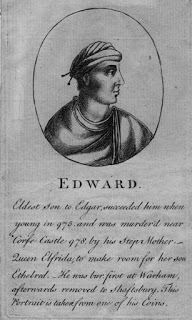

In July 975 the eldest son of King Edgar, Edward, was crowned king. Edgar had been England’s most powerful king yet (by now the country was unified), and had enjoyed a comparatively peaceful reign. Edward, however, was only 15 and was hot-tempered and ungovernable. He had powerful rivals, including his half-brother Aethelred’s mother, Elfrida (or ‘Aelfthryth’). She wanted her own son to be king – at any cost.

c975 AD, Edward the Martyr, Anglo-Saxon king of England and the elder son of King Edgar. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

One day in 978, Edward decided to pay Elfrida and Aethelred a visit in their residence at Corfe in Dorset. It was too good an opportunity to miss: Elfrida allegedly awaited him at the threshold to the hall with grooms to tend the horses, and proffered him a goblet of mulled wine (or ‘mead’), as was traditional. As Edward stooped to accept this, the grooms grabbed his bridle and stabbed him repeatedly in the stomach. Edward managed to ride away but bled to death, and was hastily buried by the conspirators. It was foul regicide, the gravest of crimes, and Aethelred, even though he may not have been involved in the plot, was implicated in the minds of the common people, who attributed his subsequent disastrous reign to this, in their eyes, monstrous deed. Edward’s body was exhumed and reburied at Shaftesbury Abbey in AD 979. During the dissolution of the monasteries the grave was lost, but in 1931 it was rediscovered. Edward’s bones were kept in a bank vault until 1984, when at last he was laid to rest.

9) England was ‘ethnically cleansed’

One of the most notorious of Aethelred’s misdeeds was a shameful act of mass-murder. Aethelred is known as ‘the Unready’, but this is actually a pun on his forename. Aethelred means ‘noble counsel’, but people started to call him ‘unraed’ which means ‘no counsel’. He was constantly vacillating, frequently cowardly, and always seemed to pick the worst men possible to advise him. One of these men, Eadric ‘Streona’ (‘the Aquisitor’), became a notorious English traitor who was to seal England’s downfall. It is a recurring theme in history that powerful men in trouble look for others to take the blame. Aethelred was convinced that the woes of the English kingdom were all the fault of the Danes, who had settled in the country for many generations and who were by now respectable Christian citizens. On 13 November 1002, secret orders went out from the king to slaughter all Danes, and massacres occurred all over southern England. The north of England was so heavily settled by the Danes that it is probable that it escaped the brutal plot. One of the Danes killed in this wicked pogrom was the sister of Sweyn Forkbeard, the mighty king of Denmark. From that time on the Danish armies were resolved to conquer England and eliminate Ethelred. Eadric Streona defected to the Danes and fought alongside them in the war of succession that followed Ethelred’s death. This was the beginning of the end for Anglo-Saxon England.

10) Neither William of Normandy or Harold Godwinson were rightful English kings

We all know something about the 1066 battle of Hastings, but the man who probably should have been king is almost forgotten to history. Edward ‘the Confessor’, the saintly English king, had died childless in 1066, leaving the English ruling council of leading nobles and spiritual leaders (the Witan) with a big problem. They knew that Edward’s cousin Duke William of Normandy had a powerful claim to the throne, which he would certainly back with armed force. William was a ruthless and skilled soldier, but the young man who had the best claim to the English throne, Edgar the ‘Aetheling’ (meaning ‘of noble or royal’ status), was only 14 and had no experience of fighting or commanding an army. Edgar was the grandson of Edmund Ironside, a famous English hero, but this would not be enough in these dangerous times. So Edgar was passed over, and Harold Godwinson, the most famous English soldier of the day, was chosen instead, even though he was not, strictly speaking, ‘royal’. He had gained essential military experience fighting in Wales, however. At first, it seemed as if the Witan had made a sound choice: Harold raised a powerful army and fleet and stood guard in the south all summer long, but then a new threat came in the north. A huge Viking army landed and destroyed an English army outside York. Harold skilfully marched his army all the way from the south to Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire in a mere five days. He annihilated the Vikings, but a few days later William’s Normans landed in the south. Harold lost no time in marching his army all the way back to meet them in battle, at a ridge of high ground just outside… Hastings.

Martin Wall is the author of The Anglo-Saxon Age: The Birth of England (Amberley Publishing, 2015). In his new book, Martin challenges our notions of the Anglo-Saxon period as barbaric and backward, to reveal a civilisation he argues is as complex, sophisticated and diverse as our own.

Edward The Confessor, Anglo-Saxon king of England. From the Bayeux Tapestry, which tells the story of the events leading to the 1066 battle of Hastings. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

1) The Anglo-Saxons were immigrants

The people we call Anglo-Saxons were actually immigrants from northern Germany and southern Scandinavia. Bede, a monk from Northumbria writing some centuries later, says that they were from some of the most powerful and warlike tribes in Germany. Bede names three of these tribes: the Angles, Saxons and Jutes. There were probably many other peoples who set out for Britain in the early fifth century, however. Batavians, Franks and Frisians are known to have made the sea crossing to the stricken province of ‘Britannia’. The collapse of the Roman empire was one of the greatest catastrophes in history. Britain, or ‘Britannia’, had never been entirely subdued by the Romans. In the far north – what they called Caledonia (modern Scotland) – there were tribes who defied the Romans, especially the Picts. The Romans built a great barrier, Hadrian’s Wall, to keep them out of the civilised and prosperous part of Britain. As soon as Roman power began to wane, these defences were degraded, and in AD 367 the Picts smashed through them. Gildas, a British historian, says that Saxon war-bands were hired to defend Britain when the Roman army had left. So the Anglo-Saxons were invited immigrants, according to this theory, a bit like the immigrants from the former colonies of the British empire in the period after 1945.

2) The Anglo-Saxons murdered their hosts at a conference

Britain was under sustained attack from the Picts in the north and the Irish in the west. The British appointed a ‘head man’, Vortigern, whose name may actually be a title meaning just that – to act as a kind of national dictator. It is possible that Vortigern was the son-in-law of Magnus Maximus, a usurper emperor who had operated from Britain before the Romans left. Vortigern’s recruitment of the Saxons ended in disaster for Britain. At a conference between the nobles of the Britons and Anglo-Saxons, [likely in AD 472, although some sources say AD 463] the latter suddenly produced concealed knives and stabbed their opposite numbers from Britain in the back.

Treaty of Hengist and Horsa with Vortigern. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

Vortigern was deliberately spared in this ‘treachery of the long-knives’, but was forced to cede large parts of south-eastern Britain to them. Vortigern was now a powerless puppet of the Saxons.

3) The Britons rallied under a mysterious leader

The Angles, Saxons, Jutes and other incomers burst out of their enclave in the south-east in the mid-fifth century and set all southern Britain ablaze. Gildas, our closest witness, says that in this emergency a new British leader emerged, called Ambrosius Aurelianus in the late 440s and early 450s. It has been postulated that Ambrosius was from the rich villa economy around Gloucestershire, but we simply do not know for sure. Amesbury in Wiltshire is named after him and may have been his campaign headquarters. A great battle took place, supposedly sometime around AD 500, at a place called Mons Badonicus or Mount Badon, probably somewhere in the south-west of modern England. The Saxons were resoundingly defeated by the Britons, but frustratingly we don’t know much more than that. A later Welsh source says that the victor was ‘Arthur’ but it was written down hundreds of years after the event, when it may have become contaminated by later folk-myths of such a person. Gildas does not mention Arthur, and this seems strange, but there are many theories about this seeming anomaly. One is that Gildas did refer to him in a sort of acrostic code, which reveals him to be a chieftain from Gwent called Cuneglas. Gildas called Cuneglas ‘the bear’, and Arthur means ‘bear’. Nevertheless, for the time being the Anglo-Saxon advance had been checked by someone, possibly Arthur.

4) Seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms emerged

‘England’ as a country did not come into existence for hundreds of years after the Anglo-Saxons arrived. Instead, seven major kingdoms were carved out of the conquered areas: Northumbria, East Anglia, Essex, Sussex, Kent, Wessex and Mercia. All these nations were fiercely independent, and although they shared similar languages, pagan religions, and socio-economic and cultural ties, they were absolutely loyal to their own kings and very competitive, especially in their favourite pastime – war.

Shield of Mercia, from the Heptarchy; a collective name applied to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of south, east, and central England during late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. Detail from an antique map of Britain by the Dutch cartographer Willem Blaeu in Atlas Novus (Amsterdam, 1635). (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

At first they were pre-occupied fighting the Britons (or ‘Welsh’, as they called them), but as soon as they had consolidated their power-centres they immediately commenced armed conflict with each other. Woden, one of their chief gods, was especially associated with war, and this military fanaticism was the chief diversion of the kings and nobles. Indeed, tales of the deeds of warriors, or their boasts of what heroics they would perform in battle, was the main form of entertainment, and obsessed the entire community – much like football today.

5) A fearsome warrior plundered his neighbours

The ‘heptarchy’, or seven kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons, all aspired to dominate the others. One reason for this was that the dominant king could exact tribute (a sort of tax, but paid in gold and silver bullion), gemstones, cattle, horses or elite weapons. A money economy did not yet exist. Eventually a leader from Mercia in the English Midlands became the most feared of all these warrior-kings: Penda, who ruled from AD 626 until 655. He personally killed many of his rivals in battle, and as one of the last pagan Anglo-Saxon kings he offered up the body of one of them, King Oswald of Northumbria, to Woden. Penda ransacked many of the other Anglo-Saxon realms, amassing vast and exquisite treasures as tribute and the discarded war-gear of fallen warriors on the battlefields. This is just the sort of elite military kit that comprises the Staffordshire Hoard, discovered in 2009. Although a definite connection is elusive, the hoard typifies the warlike atmosphere of the mid-seventh century, and the unique importance in Anglo-Saxon society of male warrior elites.

6) An African refugee helped reform the English church

The Britons were Christians, but were now cut off from Rome, but the Anglo-Saxons remained pagan. In AD 597 St Augustine had been sent to Kent by Pope Gregory the Great to convert the Anglo-Saxons. It was a tall order for his tiny mission, but gradually the seven kingdoms did convert, and became exemplary Christians – so much so that they converted their old tribal homelands in Germany.

St Augustine of Canterbury, who was sent by Pope Gregory to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. St Augustine is seen here preaching before Ethelbert, Anglo-Saxon King of Kent. Augustine was the first Archbishop of Canterbury. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

One reason why they converted was because the church said that the Christian God would deliver them victory in battles. When this failed to materialise, some Anglo-Saxon kings became apostate, and a different approach was required. The man chosen for the task was an elderly Greek named Theodore of Tarsus, but he was not the pope’s first choice. Instead he had offered the job to a younger man, Hadrian ‘the African’, a Berber refugee from north Africa, but Hadrian objected that he was too young. The truth was that people in the civilised south of Europe dreaded the idea of going to England, which was considered barbaric and had a terrible reputation. The pope decided to send both men, to keep each other company on the long journey. After more than a year (and many adventures) they arrived, and set to work to reform the English church. Theodore lived to be 88, a grand old age for those days, and Hadrian, the young man who had fled from his home in north Africa, outlived him, and continued to devote himself to his task until his death in AD 710.

7) Alfred the Great had a crippling disability

When we look up at the statue of King Alfred of Wessex in Winchester, we are confronted by an image of our national ‘superhero’: the valiant defender of a Christian realm against the heathen Viking marauders. There is no doubt that Alfred fully deserves this accolade as ‘England’s darling’, but there was another side to him that is less well known. Alfred never expected to be king – he had three older brothers – but when he was four years old on a visit to Rome the pope seemed to have granted him special favour when his father presented him to the pontiff. As he grew up, Alfred was constantly troubled by illness, including irritating and painful piles – a real problem in an age where a prince was constantly in the saddle. Asser, the Welshman who became his biographer, relates that Alfred suffered from another painful, draining malady that is not specified. Some people believe it was Crohn’s Disease, others that it may have been a sexually transmitted disease, or even severe depression. The truth is we don’t know exactly what Alfred’s mystery ailment was. Whatever it was, it is incredible to think that Alfred’s extraordinary achievements were accomplished in the face of a daily struggle with debilitating and chronic illness.

8) An Anglo-Saxon king was finally buried in 1984

In July 975 the eldest son of King Edgar, Edward, was crowned king. Edgar had been England’s most powerful king yet (by now the country was unified), and had enjoyed a comparatively peaceful reign. Edward, however, was only 15 and was hot-tempered and ungovernable. He had powerful rivals, including his half-brother Aethelred’s mother, Elfrida (or ‘Aelfthryth’). She wanted her own son to be king – at any cost.

c975 AD, Edward the Martyr, Anglo-Saxon king of England and the elder son of King Edgar. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

One day in 978, Edward decided to pay Elfrida and Aethelred a visit in their residence at Corfe in Dorset. It was too good an opportunity to miss: Elfrida allegedly awaited him at the threshold to the hall with grooms to tend the horses, and proffered him a goblet of mulled wine (or ‘mead’), as was traditional. As Edward stooped to accept this, the grooms grabbed his bridle and stabbed him repeatedly in the stomach. Edward managed to ride away but bled to death, and was hastily buried by the conspirators. It was foul regicide, the gravest of crimes, and Aethelred, even though he may not have been involved in the plot, was implicated in the minds of the common people, who attributed his subsequent disastrous reign to this, in their eyes, monstrous deed. Edward’s body was exhumed and reburied at Shaftesbury Abbey in AD 979. During the dissolution of the monasteries the grave was lost, but in 1931 it was rediscovered. Edward’s bones were kept in a bank vault until 1984, when at last he was laid to rest.

9) England was ‘ethnically cleansed’

One of the most notorious of Aethelred’s misdeeds was a shameful act of mass-murder. Aethelred is known as ‘the Unready’, but this is actually a pun on his forename. Aethelred means ‘noble counsel’, but people started to call him ‘unraed’ which means ‘no counsel’. He was constantly vacillating, frequently cowardly, and always seemed to pick the worst men possible to advise him. One of these men, Eadric ‘Streona’ (‘the Aquisitor’), became a notorious English traitor who was to seal England’s downfall. It is a recurring theme in history that powerful men in trouble look for others to take the blame. Aethelred was convinced that the woes of the English kingdom were all the fault of the Danes, who had settled in the country for many generations and who were by now respectable Christian citizens. On 13 November 1002, secret orders went out from the king to slaughter all Danes, and massacres occurred all over southern England. The north of England was so heavily settled by the Danes that it is probable that it escaped the brutal plot. One of the Danes killed in this wicked pogrom was the sister of Sweyn Forkbeard, the mighty king of Denmark. From that time on the Danish armies were resolved to conquer England and eliminate Ethelred. Eadric Streona defected to the Danes and fought alongside them in the war of succession that followed Ethelred’s death. This was the beginning of the end for Anglo-Saxon England.

10) Neither William of Normandy or Harold Godwinson were rightful English kings

We all know something about the 1066 battle of Hastings, but the man who probably should have been king is almost forgotten to history. Edward ‘the Confessor’, the saintly English king, had died childless in 1066, leaving the English ruling council of leading nobles and spiritual leaders (the Witan) with a big problem. They knew that Edward’s cousin Duke William of Normandy had a powerful claim to the throne, which he would certainly back with armed force. William was a ruthless and skilled soldier, but the young man who had the best claim to the English throne, Edgar the ‘Aetheling’ (meaning ‘of noble or royal’ status), was only 14 and had no experience of fighting or commanding an army. Edgar was the grandson of Edmund Ironside, a famous English hero, but this would not be enough in these dangerous times. So Edgar was passed over, and Harold Godwinson, the most famous English soldier of the day, was chosen instead, even though he was not, strictly speaking, ‘royal’. He had gained essential military experience fighting in Wales, however. At first, it seemed as if the Witan had made a sound choice: Harold raised a powerful army and fleet and stood guard in the south all summer long, but then a new threat came in the north. A huge Viking army landed and destroyed an English army outside York. Harold skilfully marched his army all the way from the south to Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire in a mere five days. He annihilated the Vikings, but a few days later William’s Normans landed in the south. Harold lost no time in marching his army all the way back to meet them in battle, at a ridge of high ground just outside… Hastings.

Martin Wall is the author of The Anglo-Saxon Age: The Birth of England (Amberley Publishing, 2015). In his new book, Martin challenges our notions of the Anglo-Saxon period as barbaric and backward, to reveal a civilisation he argues is as complex, sophisticated and diverse as our own.

Published on January 08, 2017 01:30

January 7, 2017

The French Brews Brothers: Benedictine Monks Bring a Traditional Brewing Practice Back to Life

Ancient Origins

Between prayer, Gregorian chants, and spiritual contemplation, Benedictine monks of Saint-Wandrille monastery in northern France are now dedicating their spare time to producing France's only monastic beer , bringing an old tradition back to life.

A Popular Beverage in Medieval Monasteries

Monastic breweries were a common practice during the middle ages – a time when monks and nuns were expected to live by their own labor and not accept charity (The Rule of Saint Benedict). However, they not only produced, but also partook in the beverage. In 2013 for example, a team of archaeologists discovered an ancient brew house which was visited daily by monks of the former Bicester Priory in England. The men of God drank beer daily to kill off bacteria, and those who visited this particular brew house would have drunk about 10 pints of beer each week.

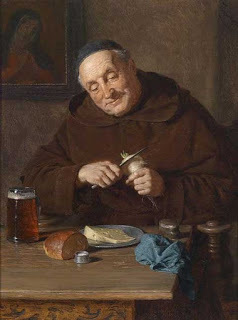

A monk with his meal (1908) By Eduard Grützner. ( Public Domain ) While monks led a solitary life of work and prayer, they also believed in hospitality and charity. Monasteries were renowned as places of refuge for travelers seeking a safe, clean place with decent food and drink. The monks grew or traded for their food and made their own drinks, thus beer and wine were readily available at the monasteries. Many monks have traditionally raised funds through brewing and selling beer.

‘Monk testing wine’ (1886) by Antonio Casanova y Estorach, from the Brooklyn Museum. ( Public Domain )

A Really Good Beer

Located in the heart of Normandy between Le Havre and Rouen, the French monastery started selling a forerunner of their beer in the late summer. They officially launched their new brew in early December. In less than a month the beer has already become a hit - receiving great feedback from craft beer market experts. French beer expert Herve Marziou, who was one of the people who advised the monks to bring this medieval monastery tradition back to life told The Local , “For me it's a major event, one of the most important since I began my career in 1973." More than 25,000 half-liter (pint) bottles costing 4.50 euros ($4.70) each have already been sold at the abbey's shop, at other monasteries, online, and through specialty stores. As the abbey proudly stated through its official website , “This is the only beer currently produced in France by monks in their own monastery.”

Drawing of a monk brewing beer. ( MicroBus Brewery )

However, this is not the first time a bunch of modern monks have produced beer for sale in a European monastery. The Strahov Monastery in Prague , Czech Republic, has also been selling a popular beer for the past couple of years based on a historic recipe. They named it the “Sv Norbert India Pale Ale” and it is based on a recipe that British soldiers brewed for their travels to India when it was under British rule.

Creating a Taste and Goals for the Near Future

The new project in the French monastery has been exclusively directed by the monks and they have even been the ones perfecting the tools they need to market the beer: the kind of bottle, labels, and packaging.

After experimenting with a brewing kit they were given by British friends, the French monks formed a committee and decided on the desired taste for their brew; “If the beer has an English taste, it is because the recipe includes four English hops varieties, grown in France – two bitter hops and two aromatic ones," Brother Matthieu explained.

Cloisters and courtyard of the Abbey of St Wandrille in France, where the new beer is being made.

( CC BY SA 3.0 )

At the end of 2015, the monks took out a 750,000-euro ($778875) bank loan to buy the necessary equipment so they could launch their ambitious brewing project, and their current goal is to produce about 80,000 liters of their exclusive beer a year.

Top Image: Three monks drinking beer. (1885) By Eduard Grützner. Source: Public Domain By Theodoros Karasavvas

Between prayer, Gregorian chants, and spiritual contemplation, Benedictine monks of Saint-Wandrille monastery in northern France are now dedicating their spare time to producing France's only monastic beer , bringing an old tradition back to life.

A Popular Beverage in Medieval Monasteries

Monastic breweries were a common practice during the middle ages – a time when monks and nuns were expected to live by their own labor and not accept charity (The Rule of Saint Benedict). However, they not only produced, but also partook in the beverage. In 2013 for example, a team of archaeologists discovered an ancient brew house which was visited daily by monks of the former Bicester Priory in England. The men of God drank beer daily to kill off bacteria, and those who visited this particular brew house would have drunk about 10 pints of beer each week.

A monk with his meal (1908) By Eduard Grützner. ( Public Domain ) While monks led a solitary life of work and prayer, they also believed in hospitality and charity. Monasteries were renowned as places of refuge for travelers seeking a safe, clean place with decent food and drink. The monks grew or traded for their food and made their own drinks, thus beer and wine were readily available at the monasteries. Many monks have traditionally raised funds through brewing and selling beer.

‘Monk testing wine’ (1886) by Antonio Casanova y Estorach, from the Brooklyn Museum. ( Public Domain )

A Really Good Beer

Located in the heart of Normandy between Le Havre and Rouen, the French monastery started selling a forerunner of their beer in the late summer. They officially launched their new brew in early December. In less than a month the beer has already become a hit - receiving great feedback from craft beer market experts. French beer expert Herve Marziou, who was one of the people who advised the monks to bring this medieval monastery tradition back to life told The Local , “For me it's a major event, one of the most important since I began my career in 1973." More than 25,000 half-liter (pint) bottles costing 4.50 euros ($4.70) each have already been sold at the abbey's shop, at other monasteries, online, and through specialty stores. As the abbey proudly stated through its official website , “This is the only beer currently produced in France by monks in their own monastery.”

Drawing of a monk brewing beer. ( MicroBus Brewery )

However, this is not the first time a bunch of modern monks have produced beer for sale in a European monastery. The Strahov Monastery in Prague , Czech Republic, has also been selling a popular beer for the past couple of years based on a historic recipe. They named it the “Sv Norbert India Pale Ale” and it is based on a recipe that British soldiers brewed for their travels to India when it was under British rule.

Creating a Taste and Goals for the Near Future

The new project in the French monastery has been exclusively directed by the monks and they have even been the ones perfecting the tools they need to market the beer: the kind of bottle, labels, and packaging.

After experimenting with a brewing kit they were given by British friends, the French monks formed a committee and decided on the desired taste for their brew; “If the beer has an English taste, it is because the recipe includes four English hops varieties, grown in France – two bitter hops and two aromatic ones," Brother Matthieu explained.

Cloisters and courtyard of the Abbey of St Wandrille in France, where the new beer is being made.

( CC BY SA 3.0 )

At the end of 2015, the monks took out a 750,000-euro ($778875) bank loan to buy the necessary equipment so they could launch their ambitious brewing project, and their current goal is to produce about 80,000 liters of their exclusive beer a year.

Top Image: Three monks drinking beer. (1885) By Eduard Grützner. Source: Public Domain By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on January 07, 2017 01:30

January 6, 2017

11 things you (probably) didn’t know about Sherlock Holmes

History Extra

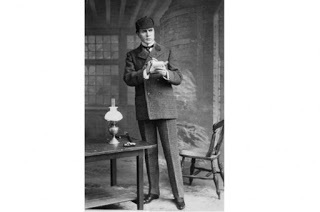

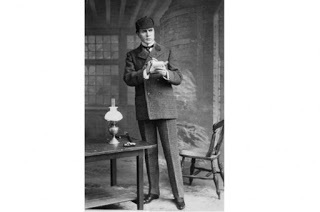

Actor William Gillette playing the detective Sherlock Holmes, 1899. (Photo by Gillette/London Stereoscopic Company/Getty Images)

In A Holmes & Hudson Mystery: Mrs Hudson and the Spirits’ Curse, Martin Davies reimagines the activities of Baker Street’s best-known residents to bring a fresh twist to the classic Victorian mystery. Here, writing for History Extra, Davies shares 11 things you (probably) didn’t know about Sherlock Holmes… Since Sherlock Holmes’ creation, dozens of actors have attempted to portray the great detective – on stage, on radio, in films and on television. But their efforts to breathe new life into this enigmatic character might well have been greeted with bemusement by Holmes’ creator, who wrote in a letter in 1892: “Holmes is as inhuman as Babbage’s Calculating Machine.” Did you know…

1) The first actor to take on the role of Sherlock Holmes in any official capacity was the American William Gillette, whose 1899 stage play was adapted from a script by Conan Doyle himself. Opening six years after the author had attempted to kill off his creation at the Reichenbach Falls, the play was a huge success on both sides of the Atlantic: between 1899 and 1932, Gillette performed the role more than 1,000 times. Gillette is also credited with introducing the curved briar pipe that was to become synonymous with the great detective – possibly because a straight pipe obscured the actor’s face when he delivered his lines. On first meeting Sherlock Holmes’ creator, Gillette is said to have appeared in character, complete with deerstalker, and after examining Conan Doyle most minutely, to have opined: “Unquestionably an author!”

2) Gillette was also one of the first to annoy the purists by introducing a love interest for Holmes. When he telegraphed Conan Doyle with the question “May I marry him?” the author is said to have replied: “You may marry him, or murder or do what you like with him!” It’s impossible to count the number of writers who, since then, have taken Doyle at his word.

3) Holmes, having survived the Reichenbach Falls, refused to die with his creator. By the time of Conan Doyle’s death [7 July 1930], Holmes was already a star of stage and screen. His film debut, Sherlock Holmes Baffled, came as early as 1900. Just a few seconds long, the film used stop-motion camerawork to show Holmes attempting to grapple with a burglar who repeatedly disappears, then reappears in a different part of the room.

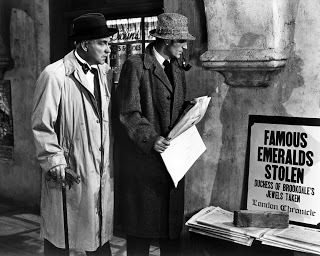

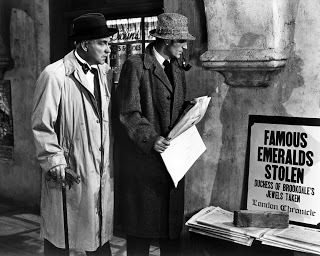

4) One of the oldest surviving film adaptations of Conan Doyle’s work dates to 1916 (William Gillette again), but it was the English duo of Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce in the 1940s who for many years became identified in the public imagination as the Holmes and Watson.

British actors Nigel Bruce (left) as Dr Watson and Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes in 'Pursuit to Algiers', 1945. (Photo by Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images)

Rathbone and Bruce made 14 Sherlock Holmes films between 1939 and 1946 (and starred in more than 200 dramatisations for American radio), yet only the first two films were set in the Victorian period. The others had a contemporary setting, allowing Sherlock Holmes to pursue Nazi spies and to urge the purchase of war bonds. Bruce’s dim, bumbling Watson tends to infuriate Holmes purists.

5) The Adventures of ChubbLock Homes, an early comic strip, appeared in Comic Cuts magazine as early as 1893, and the urge to parody the great detective has never gone away. In 1901, while William Gillette’s official Holmes play was running in London, audiences at Terry’s Theatre were enjoying performances of the rather more frivolous Sheerluck Jones. The comic strip Sherlocko & Watson was hugely popular in the USA in the early 20th century, and silent film parodies abounded. Later in the century, Peter Cook and John Cleese both played comedy Sherlocks on film (Cleese's character was Arthur Sherlock Holmes, Sherlock’s grandson). Less well remembered, perhaps, is the 1976 TV film The Return of the World’s Greatest Detective, in which a youthful Larry Hagman (before his JR Ewing days) played a deluded motorcycle cop, Sherman Holmes.

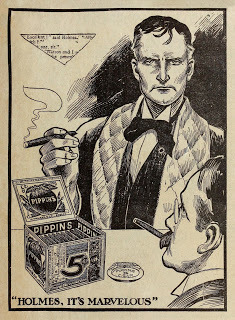

6) Even in his early days, Sherlock Holmes was helping manufacturers to sell their products. In the 1890s, the makers of Beecham’s Pills ran advertisements suggesting that the great detective was a devoted user. And as a smoker, Holmes was popular with the tobacco companies. Early cigarette advertisements using Holmes’ image included brands such as Lambert and Butler’s ‘Varsity’ mixture, Chesterfield, Ogden’s, Gallaher’s and Players. Since then, products as diverse as furniture cream, mouthwash, breakfast cereal and photocopiers have all benefited from association with the great man.

"Holmes, it's Marvelous" Pippins Cigar print advert featuring Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson. From a series of booklets distributed with The Boston Sunday Post in 1911. Sherlock is drawn to resemble actor William Gillette. (© Contraband Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

7) With the growth of television after the Second World War, the Baker Street detective was quick to adapt to the new medium. Alan Wheatley was the first actor to portray Holmes on British television – his 1951 series was broadcast live. But it seems Wheatley was not a fan of Holmes. When asked about Holmes’ character, he is said to have replied: “In my opinion he just seemed to be an insufferable prig”.

8) Peter Cushing appeared as Holmes on the BBC in the 1960s. He had already played the detective in the 1959 Hammer film The Hound of the Baskervilles, alongside Christopher Lee as Sir Henry Baskerville. Lee was to play Holmes himself in a 1962 film; then, nearly 30 years later, he took up the pipe again, playing an ageing Sherlock in two TV films known together as Sherlock Holmes the Golden Years. Throw in an appearance as Mycroft Holmes in Billy Wilder’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, and Sir Christopher almost bagged the complete set. Alas, he never appeared on screen as Doctor Watson.

[image error]

English actor Peter Cushing as fictional detective Sherlock Holmes with Andre Morell as Dr Watson in a scene from 'The Hound of the Baskervilles', 1959. (Photo by Express Newspapers/Getty Images)

9) For many people, the definitive portrayal of Sherlock Holmes was by Jeremy Brett, for Granada Television, in the 1980s and 1990s. Brett appeared in 41 episodes, including five feature-length productions. However, even that impressive achievement doesn’t make Brett the most prolific Holmes. That title must go to the British actor Clive Merrison, who played the detective on BBC Radio between 1989 and 1998, and who completed the full canon – dramatisations of all 60 of Conan Doyle’s Holmes stories and novels.

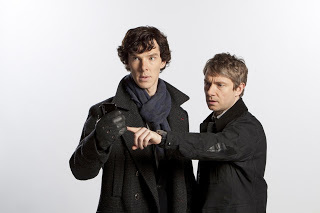

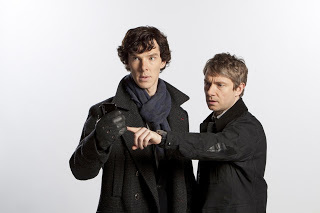

10) And so to Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock, in which Andrew Scott rose to prominence playing Moriarty. Scott has since appeared in the new James Bond film, Spectre, joining an illustrious club of actors who have performed alongside Britain’s most famous spy and Britain’s most famous detective. But only Sir Roger Moore has played both leading roles on film. Sadly his one appearance as Holmes – in the 1976 TV-film Sherlock Holmes in New York – is not, perhaps, his most memorable work. Sean Connery never played Holmes, but he did play the ultra-astute friar William of Baskerville in The Name of the Rose, so you might say that he came close.

Benedict Cumberbatch as Sherlock (season 1). (© Photos 12/Alamy Stock Photo)

11) The actor playing Dr Watson to Roger Moore’s Holmes was Patrick Macnee, most famous as John Steed in The Avengers. Macnee played Watson again, 15 years later, alongside Christopher Lee’s Holmes. Then, in 1993, he donned the deerstalker himself in The Hound of London, thus becoming that very rare thing – an actor who has starred in films as both Holmes and Watson. Martin Davies’

Mrs Hudson and the Spirits’ Curse is published by Canelo.

Actor William Gillette playing the detective Sherlock Holmes, 1899. (Photo by Gillette/London Stereoscopic Company/Getty Images)

In A Holmes & Hudson Mystery: Mrs Hudson and the Spirits’ Curse, Martin Davies reimagines the activities of Baker Street’s best-known residents to bring a fresh twist to the classic Victorian mystery. Here, writing for History Extra, Davies shares 11 things you (probably) didn’t know about Sherlock Holmes… Since Sherlock Holmes’ creation, dozens of actors have attempted to portray the great detective – on stage, on radio, in films and on television. But their efforts to breathe new life into this enigmatic character might well have been greeted with bemusement by Holmes’ creator, who wrote in a letter in 1892: “Holmes is as inhuman as Babbage’s Calculating Machine.” Did you know…

1) The first actor to take on the role of Sherlock Holmes in any official capacity was the American William Gillette, whose 1899 stage play was adapted from a script by Conan Doyle himself. Opening six years after the author had attempted to kill off his creation at the Reichenbach Falls, the play was a huge success on both sides of the Atlantic: between 1899 and 1932, Gillette performed the role more than 1,000 times. Gillette is also credited with introducing the curved briar pipe that was to become synonymous with the great detective – possibly because a straight pipe obscured the actor’s face when he delivered his lines. On first meeting Sherlock Holmes’ creator, Gillette is said to have appeared in character, complete with deerstalker, and after examining Conan Doyle most minutely, to have opined: “Unquestionably an author!”

2) Gillette was also one of the first to annoy the purists by introducing a love interest for Holmes. When he telegraphed Conan Doyle with the question “May I marry him?” the author is said to have replied: “You may marry him, or murder or do what you like with him!” It’s impossible to count the number of writers who, since then, have taken Doyle at his word.

3) Holmes, having survived the Reichenbach Falls, refused to die with his creator. By the time of Conan Doyle’s death [7 July 1930], Holmes was already a star of stage and screen. His film debut, Sherlock Holmes Baffled, came as early as 1900. Just a few seconds long, the film used stop-motion camerawork to show Holmes attempting to grapple with a burglar who repeatedly disappears, then reappears in a different part of the room.

4) One of the oldest surviving film adaptations of Conan Doyle’s work dates to 1916 (William Gillette again), but it was the English duo of Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce in the 1940s who for many years became identified in the public imagination as the Holmes and Watson.

British actors Nigel Bruce (left) as Dr Watson and Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes in 'Pursuit to Algiers', 1945. (Photo by Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images)

Rathbone and Bruce made 14 Sherlock Holmes films between 1939 and 1946 (and starred in more than 200 dramatisations for American radio), yet only the first two films were set in the Victorian period. The others had a contemporary setting, allowing Sherlock Holmes to pursue Nazi spies and to urge the purchase of war bonds. Bruce’s dim, bumbling Watson tends to infuriate Holmes purists.