MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 71

December 30, 2016

Christmas carols: the history behind 5 festive favourites

History Extra

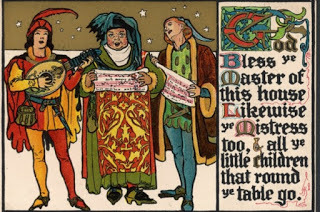

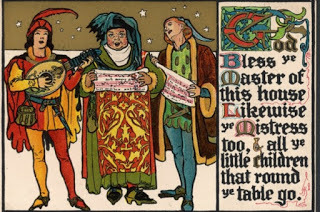

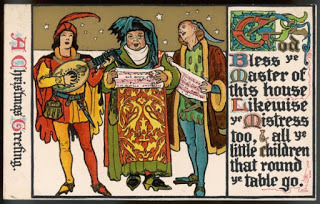

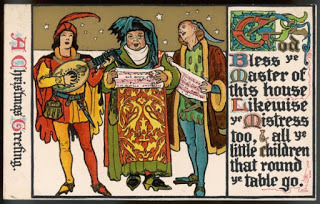

Three medieval carol singers depicted in a card from 1911. (Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo) 1)

The Twelve Days of Christmas

Of all the Christmas carols we sing today, none presents more of a challenge than The Twelve Days of Christmas, with its baffling list of lyrics. What exactly are we to make of this aviary of birds – the swans, geese, doves, hens and calling birds – and what on earth is a partridge (strictly a ground bird) doing up a pear tree? The origins of the carol make things a little clearer. Historians generally agree that the verse first evolved as a festive memory game. The list of objects or animals grows with each verse and forfeits are imposed for forgetting one.

But that still leaves us with the problem of the partridge. While the English partridge is a creature of fields and moors, its French cousin is apparently more likely to find itself up a tree. And if the partridge really is French then it would be called une perdrix. Correctly pronounced ‘pere-dree’, suddenly this word sounds an awful lot like that pear tree. Could it, perhaps, just be an elaborate international game of Chinese whispers that has left us with a partridge stuck forever in a misheard pear tree?

One interpretation of the carol places its origin in the 16th century. The list of bizarre gifts given by the carol author’s ‘true love’ becomes a secret code for Catholics – whose religion had to be practised in secret after the Reformation – to share their beliefs. So the ‘true love’ becomes God himself and the partridge Jesus Christ. The ‘two turtle doves’ are the old and new testaments, ‘three French hens’ the Trinity, ‘four calling birds’ are the four Gospels, all the way through to ‘twelve drummers drumming’ – the twelve points of the apostles’ creed. If you were a Tudor child, wouldn’t you much rather recite this than your catechism?

2) We Wish You a Merry Christmas

What’s interesting about this catchy little carol are the customs it reveals. Both wassailing and mumming were still going strong under the Tudor monarchs, with carollers and players going from door to door performing. It was terribly bad luck not to reward their efforts with food and drink, including the ‘figgy pudding’ – an early version of what we now know as Christmas pudding.

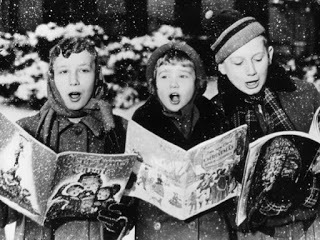

Three young carol singers. (Keystone/Getty Images)

3) Deck the Halls

One popular 16th-century song was the carol we know today as Deck the Halls. Back then it was a favourite Welsh song, originally titled Nos Galan. It wasn’t until the 19th century that it acquired Christmassy words and became part of our own festivities. In its earliest form, Deck the Halls was just a folk song, but one with some rather naughty words. Translated directly, the Welsh text reads something like this:

Oh! how soft my fair one’s bosom, fal lal lal lal lal lal lal lal la Oh! how sweet the grove in blossom, fal lal lal lal lal lal lal lal la

Oh! how blessed are the blisses, Words of love, and mutual kisses, fal lal lal lal lal lal lal lal la These words would not have suited the prim Victorians, so when Thomas Oliphant came to write an English text for the melody in the 1860s he started from scratch, co-opting the dancing melody and lively ‘fa la la’ chorus for an altogether more innocent celebration of Christmas preparations.

A Christmas carols greeting card received 1893. (Amoret Tanner/Alamy Stock Photo)

4) The Holly and the Ivy

Although this charming carol, based on an English folk tune, probably dates from the 17th century, its symbolism is far older. Both the festivals of Saturnalia and Yule placed great emphasis on evergreens. The Romans would exchange boughs of holly and ivy with their friends during the festival, while both the Scandinavians and the Anglo-Saxon pagans would decorate their homes with the evergreens they saw as symbols of eternal life.

So try as Christian carol writers might to impose their own symbols on the plants – the red holly berry as Jesus’s blood, the white holly flower his shroud – they have to work hard to displace earlier layers of meaning. Some think there’s a further secret layer of meaning to the carol. Is the holly, with its phallic prickles, a symbol of the masculine, and the clinging ivy of the feminine? English courtiers were fond of such hidden language and holly-and-ivy carols could have formed the basis of courting games.

5) Silent night

A firm favourite throughout the 19th century was the lovely Silent Night. Schoolmaster Franz Xaver Gruber and priest Joseph Mohr first performed the carol in the church of St Nikola in Oberndorf, Austria, in its original German (Stille Nacht) on Christmas Eve 1818.

Legends attached to this timeless carol persist, to a point where it’s hard to dig out the truth from among them. One charming tale tells of mice chewing through vital sections of St Nikola’s organ, leaving the church without music at Christmas. The resourceful young teacher and priest, so the story goes, stepped in to save the service by composing a simple carol that could be sung with just guitar accompaniment.

These extracts are taken from Carols from King’s (BBC Books, £9.99) by Alexandra Coghlan, a music journalist and former Cambridge choral scholar.

Three medieval carol singers depicted in a card from 1911. (Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo) 1)

The Twelve Days of Christmas

Of all the Christmas carols we sing today, none presents more of a challenge than The Twelve Days of Christmas, with its baffling list of lyrics. What exactly are we to make of this aviary of birds – the swans, geese, doves, hens and calling birds – and what on earth is a partridge (strictly a ground bird) doing up a pear tree? The origins of the carol make things a little clearer. Historians generally agree that the verse first evolved as a festive memory game. The list of objects or animals grows with each verse and forfeits are imposed for forgetting one.

But that still leaves us with the problem of the partridge. While the English partridge is a creature of fields and moors, its French cousin is apparently more likely to find itself up a tree. And if the partridge really is French then it would be called une perdrix. Correctly pronounced ‘pere-dree’, suddenly this word sounds an awful lot like that pear tree. Could it, perhaps, just be an elaborate international game of Chinese whispers that has left us with a partridge stuck forever in a misheard pear tree?

One interpretation of the carol places its origin in the 16th century. The list of bizarre gifts given by the carol author’s ‘true love’ becomes a secret code for Catholics – whose religion had to be practised in secret after the Reformation – to share their beliefs. So the ‘true love’ becomes God himself and the partridge Jesus Christ. The ‘two turtle doves’ are the old and new testaments, ‘three French hens’ the Trinity, ‘four calling birds’ are the four Gospels, all the way through to ‘twelve drummers drumming’ – the twelve points of the apostles’ creed. If you were a Tudor child, wouldn’t you much rather recite this than your catechism?

2) We Wish You a Merry Christmas

What’s interesting about this catchy little carol are the customs it reveals. Both wassailing and mumming were still going strong under the Tudor monarchs, with carollers and players going from door to door performing. It was terribly bad luck not to reward their efforts with food and drink, including the ‘figgy pudding’ – an early version of what we now know as Christmas pudding.

Three young carol singers. (Keystone/Getty Images)

3) Deck the Halls

One popular 16th-century song was the carol we know today as Deck the Halls. Back then it was a favourite Welsh song, originally titled Nos Galan. It wasn’t until the 19th century that it acquired Christmassy words and became part of our own festivities. In its earliest form, Deck the Halls was just a folk song, but one with some rather naughty words. Translated directly, the Welsh text reads something like this:

Oh! how soft my fair one’s bosom, fal lal lal lal lal lal lal lal la Oh! how sweet the grove in blossom, fal lal lal lal lal lal lal lal la

Oh! how blessed are the blisses, Words of love, and mutual kisses, fal lal lal lal lal lal lal lal la These words would not have suited the prim Victorians, so when Thomas Oliphant came to write an English text for the melody in the 1860s he started from scratch, co-opting the dancing melody and lively ‘fa la la’ chorus for an altogether more innocent celebration of Christmas preparations.

A Christmas carols greeting card received 1893. (Amoret Tanner/Alamy Stock Photo)

4) The Holly and the Ivy

Although this charming carol, based on an English folk tune, probably dates from the 17th century, its symbolism is far older. Both the festivals of Saturnalia and Yule placed great emphasis on evergreens. The Romans would exchange boughs of holly and ivy with their friends during the festival, while both the Scandinavians and the Anglo-Saxon pagans would decorate their homes with the evergreens they saw as symbols of eternal life.

So try as Christian carol writers might to impose their own symbols on the plants – the red holly berry as Jesus’s blood, the white holly flower his shroud – they have to work hard to displace earlier layers of meaning. Some think there’s a further secret layer of meaning to the carol. Is the holly, with its phallic prickles, a symbol of the masculine, and the clinging ivy of the feminine? English courtiers were fond of such hidden language and holly-and-ivy carols could have formed the basis of courting games.

5) Silent night

A firm favourite throughout the 19th century was the lovely Silent Night. Schoolmaster Franz Xaver Gruber and priest Joseph Mohr first performed the carol in the church of St Nikola in Oberndorf, Austria, in its original German (Stille Nacht) on Christmas Eve 1818.

Legends attached to this timeless carol persist, to a point where it’s hard to dig out the truth from among them. One charming tale tells of mice chewing through vital sections of St Nikola’s organ, leaving the church without music at Christmas. The resourceful young teacher and priest, so the story goes, stepped in to save the service by composing a simple carol that could be sung with just guitar accompaniment.

These extracts are taken from Carols from King’s (BBC Books, £9.99) by Alexandra Coghlan, a music journalist and former Cambridge choral scholar.

Published on December 30, 2016 02:00

December 29, 2016

Medieval Ring Found in Robin Hood’s Forest Hideout May Net Finder a Small Fortune

Ancient Origins

An amateur treasure hunter with a metal detector turned up a Medieval, gold ring that was set with a sapphire stone in Sherwood Forest—haunt of the legendary (or real) Robin Hood. Experts have examined the ring and believe it may date to the 14th century.

The amateur, Mark Thompson, 34, had been using an inexpensive detector that he bought on the online auction website Ebay. He is a painter of fork-lifts and had been searching for treasure for just a year and a half, says the Daily Mail.

The ring may net him a small fortune if it truly is worth its estimated maximum value of $87,000 (70,000 British pounds). He detected metal underneath his wand just 20 minutes into his recent session in Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshire. The British Museum is examining the ring with the expectation of formally declaring it treasure.

The British Museum is analyzing the ring and may declare it to be national treasure, though the finder would collect any reward. (Mark Thompson photo)

Online news accounts of the find said Mr. Thompson expected to find scrap metal of no value or coins of little value, but when he turned up the soil he saw the glint of gold.

One side of the ring depicts a baby, possibly the Christ child, and the other side depicts a female saint, both engraved into the gold of the ring. Mr. Thompson reported the find to proper authorities.

“I called my friend who came down to take a look and help see whether there was anything else related nearby,” Thompson told British news outlets. “If it does prove to be as valuable as we think it might be, it would completely change my life. I’m renting at the moment and I’d love to be able to buy a house or move into somewhere more comfortable.”

A regional finds liaison officer, Dot Boughton, said the ring is being examined by the coroner. The coroner may confirm the ring as treasure at an inquest, after which museums will have a chance to display the ring. Mr. Thompson would collect any reward.

Ms. Boughton has written a report, says the Sun, that compares the stone to another that adorns the tomb of William Wylesey, who died in 1374 and who was the archbishop of Canterbury.

The ring is not believed to be contemporaneous with Robin Hood, who, according to legend, operated with his gang out of Sherwood Forest in the 13th century, around the time of King John. It is unknown who Robin Hood truly was or even if he was more than just a legend but a real historical figure.

A statue of Robin Hood at a castle in Nottinghamshire, where the legendary robber was an outlaw in Sherwood Forest. ( Wikimedia Commons photo /Olaf1541)

A statue of Robin Hood at a castle in Nottinghamshire, where the legendary robber was an outlaw in Sherwood Forest. ( Wikimedia Commons photo /Olaf1541)

He differs from other robbers of the time, including Fulk Fitzwarin and Eustace the Monk, who were real people and not just legendary. Legends say Robin Hood stole from the rich and gave to the poor.

One thing all three of these robbers and other fugitives have in common was that they used the king’s private forest reserves for refuge. The forests of Sherwood and Barnsdale, which are rife with old legends, were supposed to have been the kings’ private lands where they could hunt.

Historians think there may have been two historical figures from whom the legend of Robin Hood derives. Other outlaws also possibly took the name, which further confuses the historical record.

Top image: Experts have valued the ring between $25,000 (20,000 British pounds) and $87,000 (70,000 pounds). The man who detected it, Mark Thompson, will collect any reward associated with the gold ring set with a sapphire stone. (Mark Thompson photo)

By Mark Miller

An amateur treasure hunter with a metal detector turned up a Medieval, gold ring that was set with a sapphire stone in Sherwood Forest—haunt of the legendary (or real) Robin Hood. Experts have examined the ring and believe it may date to the 14th century.

The amateur, Mark Thompson, 34, had been using an inexpensive detector that he bought on the online auction website Ebay. He is a painter of fork-lifts and had been searching for treasure for just a year and a half, says the Daily Mail.

The ring may net him a small fortune if it truly is worth its estimated maximum value of $87,000 (70,000 British pounds). He detected metal underneath his wand just 20 minutes into his recent session in Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshire. The British Museum is examining the ring with the expectation of formally declaring it treasure.

The British Museum is analyzing the ring and may declare it to be national treasure, though the finder would collect any reward. (Mark Thompson photo)

Online news accounts of the find said Mr. Thompson expected to find scrap metal of no value or coins of little value, but when he turned up the soil he saw the glint of gold.

One side of the ring depicts a baby, possibly the Christ child, and the other side depicts a female saint, both engraved into the gold of the ring. Mr. Thompson reported the find to proper authorities.

“I called my friend who came down to take a look and help see whether there was anything else related nearby,” Thompson told British news outlets. “If it does prove to be as valuable as we think it might be, it would completely change my life. I’m renting at the moment and I’d love to be able to buy a house or move into somewhere more comfortable.”

A regional finds liaison officer, Dot Boughton, said the ring is being examined by the coroner. The coroner may confirm the ring as treasure at an inquest, after which museums will have a chance to display the ring. Mr. Thompson would collect any reward.

Ms. Boughton has written a report, says the Sun, that compares the stone to another that adorns the tomb of William Wylesey, who died in 1374 and who was the archbishop of Canterbury.

The ring is not believed to be contemporaneous with Robin Hood, who, according to legend, operated with his gang out of Sherwood Forest in the 13th century, around the time of King John. It is unknown who Robin Hood truly was or even if he was more than just a legend but a real historical figure.

A statue of Robin Hood at a castle in Nottinghamshire, where the legendary robber was an outlaw in Sherwood Forest. ( Wikimedia Commons photo /Olaf1541)

A statue of Robin Hood at a castle in Nottinghamshire, where the legendary robber was an outlaw in Sherwood Forest. ( Wikimedia Commons photo /Olaf1541)He differs from other robbers of the time, including Fulk Fitzwarin and Eustace the Monk, who were real people and not just legendary. Legends say Robin Hood stole from the rich and gave to the poor.

One thing all three of these robbers and other fugitives have in common was that they used the king’s private forest reserves for refuge. The forests of Sherwood and Barnsdale, which are rife with old legends, were supposed to have been the kings’ private lands where they could hunt.

Historians think there may have been two historical figures from whom the legend of Robin Hood derives. Other outlaws also possibly took the name, which further confuses the historical record.

Top image: Experts have valued the ring between $25,000 (20,000 British pounds) and $87,000 (70,000 pounds). The man who detected it, Mark Thompson, will collect any reward associated with the gold ring set with a sapphire stone. (Mark Thompson photo)

By Mark Miller

Published on December 29, 2016 02:00

December 28, 2016

Stunning Celtic Horse Harness Became Treasured Brooch of Norwegian Viking Woman

Ancient Origins

During the summer of 2016, a beautiful bronze brooch was found opportunely at Agdenes farm, at the outermost part of the Trondheim Fjord in mid-Norway, buried as a status symbol in the grave of a Viking woman. An analysis of the precious artifact revealed that it is a 9th century ornament that was originally a Celtic horse harness and was likely stolen during Viking raids in Ireland.

The Decorations Imply that the Jewelry Was Designed in Ireland

The well-maintained piece of jewelry is an ornament with a bird figure that has fish or dolphin like patterns on both sides. The decorations suggest that it was probably created in a Celtic workshop, probably in Ireland, between the 8th and 9th century. What’s more surprising though, it’s the fact that it was originally used as a fitting for a horse’s harness. The holes at the bottom and traces of rust from a needle on the back, reveal that it had probably been turned into a brooch at a later stage.

Some of you might wonder now how a fitting from an Irish horse’s harness ended up being brooch for a Norwegian Viking but those who are familiar with Vikings, a successful historical drama television series written and created by Michael Hirst for the channel History, shouldn’t be surprised. As the show clearly shows, Norwegian Vikings took part in relentless raids of the British Isles.

According to Heritage Daily, Aina Margrethe Heen Pettersen, a doctoral student at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology’s (NTNU) Department of Historical Studies, works with finds brought to Norway during the Viking age and verifies what the popular TV series shows, “A housewife in Mid-Norway probably received the fitting as a gift from a family member who took part in one or more Viking raids to Ireland or Great Britain. When she died, the jewelry was given to her as a burial gift. It has stayed underground until it was found by chance this summer.” She also adds that this is not the first time they have found such pieces of jewelry from that era in a woman’s grave, and speculates that this was a way for Vikings to show their love to their women after they returned from their conquests to the British Isles.

Vikings undertook relentless raids of the British Isles. Thorir Hund kills King Olaf at the Battle of Stiklestad (public domain)

The Visual and Cultural Significance of The Symbols

It looks like love and affection weren’t the only reason Vikings handed such objects to their women, or other female family members. The Vikings who participated in the early raids to the British Isles and made it back alive, gave these objects to female family members not just as gifts but also as trophies that gave them a prestigious status within the Viking societies. The fittings were then transformed into pieces of jewelry, and were worn on traditional Norse clothing as brooches, pendants or belt fittings. Heen Pettersen says about this common practice that became a tradition, “As a result, it became clear to everyone that those women had family members who had taken part in successful expeditions far away. There are traces of gold on the surface of the jewelry, so it was originally covered in gold. It therefore appeared to be more valuable than it actually was. In addition, each piece of jewelry was unique, so the owner did not risk having the housewife next door turn up with the same piece of jewelry.”

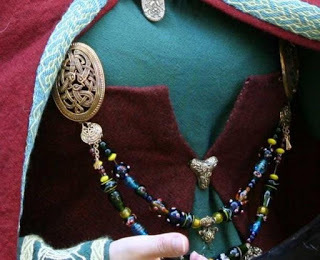

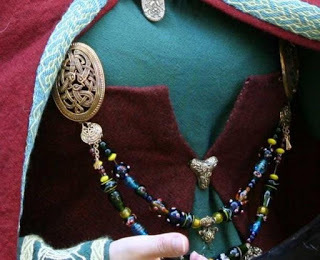

An example of how a Viking woman would have worn her brooch.

The Grave Has Been Disturbed

Heen Pettersen claims that the impressive jewelry was discovered by a civilian with a metal detector so it can’t be considered a find from an archaeological site that was officially excavated. Additionally, the fact that the bronze brooch was not found in the original grave, clearly shows that the grave was disturbed at some point. Regardless these misfortunes, Heen Pettersen is pretty satisfied with the finding and says to Heritage Daily that its cultural and historical value is undeniable, “The new find from Agdenes farm shows that the area was populated in the first part of the Viking Age. Even though it is a random find, it is a nice reminder that Mid-Norway was involved in the early contact with the British Isles.”

Top image: The Celtic harness found buried with a Viking woman in Norway (Photo: Åge Hojem / NTNU Museum of Natural History and Archaeology)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

During the summer of 2016, a beautiful bronze brooch was found opportunely at Agdenes farm, at the outermost part of the Trondheim Fjord in mid-Norway, buried as a status symbol in the grave of a Viking woman. An analysis of the precious artifact revealed that it is a 9th century ornament that was originally a Celtic horse harness and was likely stolen during Viking raids in Ireland.

The Decorations Imply that the Jewelry Was Designed in Ireland

The well-maintained piece of jewelry is an ornament with a bird figure that has fish or dolphin like patterns on both sides. The decorations suggest that it was probably created in a Celtic workshop, probably in Ireland, between the 8th and 9th century. What’s more surprising though, it’s the fact that it was originally used as a fitting for a horse’s harness. The holes at the bottom and traces of rust from a needle on the back, reveal that it had probably been turned into a brooch at a later stage.

Some of you might wonder now how a fitting from an Irish horse’s harness ended up being brooch for a Norwegian Viking but those who are familiar with Vikings, a successful historical drama television series written and created by Michael Hirst for the channel History, shouldn’t be surprised. As the show clearly shows, Norwegian Vikings took part in relentless raids of the British Isles.

According to Heritage Daily, Aina Margrethe Heen Pettersen, a doctoral student at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology’s (NTNU) Department of Historical Studies, works with finds brought to Norway during the Viking age and verifies what the popular TV series shows, “A housewife in Mid-Norway probably received the fitting as a gift from a family member who took part in one or more Viking raids to Ireland or Great Britain. When she died, the jewelry was given to her as a burial gift. It has stayed underground until it was found by chance this summer.” She also adds that this is not the first time they have found such pieces of jewelry from that era in a woman’s grave, and speculates that this was a way for Vikings to show their love to their women after they returned from their conquests to the British Isles.

Vikings undertook relentless raids of the British Isles. Thorir Hund kills King Olaf at the Battle of Stiklestad (public domain)

The Visual and Cultural Significance of The Symbols

It looks like love and affection weren’t the only reason Vikings handed such objects to their women, or other female family members. The Vikings who participated in the early raids to the British Isles and made it back alive, gave these objects to female family members not just as gifts but also as trophies that gave them a prestigious status within the Viking societies. The fittings were then transformed into pieces of jewelry, and were worn on traditional Norse clothing as brooches, pendants or belt fittings. Heen Pettersen says about this common practice that became a tradition, “As a result, it became clear to everyone that those women had family members who had taken part in successful expeditions far away. There are traces of gold on the surface of the jewelry, so it was originally covered in gold. It therefore appeared to be more valuable than it actually was. In addition, each piece of jewelry was unique, so the owner did not risk having the housewife next door turn up with the same piece of jewelry.”

An example of how a Viking woman would have worn her brooch.

The Grave Has Been Disturbed

Heen Pettersen claims that the impressive jewelry was discovered by a civilian with a metal detector so it can’t be considered a find from an archaeological site that was officially excavated. Additionally, the fact that the bronze brooch was not found in the original grave, clearly shows that the grave was disturbed at some point. Regardless these misfortunes, Heen Pettersen is pretty satisfied with the finding and says to Heritage Daily that its cultural and historical value is undeniable, “The new find from Agdenes farm shows that the area was populated in the first part of the Viking Age. Even though it is a random find, it is a nice reminder that Mid-Norway was involved in the early contact with the British Isles.”

Top image: The Celtic harness found buried with a Viking woman in Norway (Photo: Åge Hojem / NTNU Museum of Natural History and Archaeology)

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on December 28, 2016 02:00

December 27, 2016

Festive QI facts: 8 things you (probably) didn’t know about the history of Christmas

History Extra

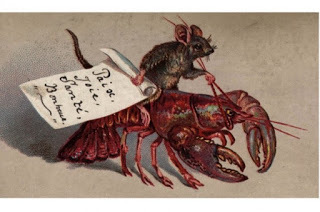

This Victorian Christmas greetings card c1880 depicts a mouse riding a lobster. The card wishes the recipient 'Paix, Joie, Sante, Bonheur' or 'Peace, Joy, Health and Happiness'. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The book of weird and wonderful trivia is compiled by members of the team behind the BBC Television series QI including John Lloyd CBE, the show’s creator; John Mitchinson, QI’s first researcher; James Harkin, QI’s Head Elf and producer of QI’s BBC Radio 4 show The Museum of Curiosity; and Anne Miller, a scriptwriter and researcher for QI. Described as a portal, the book features 1,342 factual nuggets about which readers can find out more by visiting qi.com/1342 and entering the page number of the fact that interests them. The book comes 10 years after the publication of the first QI book, The Book of General Ignorance.

Here we bring you eight historical festive facts featured in 1,342 QI Facts To Leave You Flabbergasted…

1) In the 17th century, Christmas turkeys walked from East Anglia to London in three months.

2) Murderous frogs featured on Victorian Christmas cards, along with children being boiled in teapots and mice riding lobsters.

3) After noticing that she washed up bare-handed, Margaret Thatcher sent the Queen rubber gloves for Christmas.

4) The fake snow in The Wizard of Oz (1939) and White Christmas (1954) was made of asbestos.

American actors Bing Crosby, Rosemary Clooney, Vera-Ellen and Danny Kaye sing together in a scene from the 1954 film 'White Christmas'. (Photo by John Swope/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images)

5) Orthodox Jewish couples abstain from sex on Christmas Eve. Rabbis used to advise them to pass the time tearing toilet paper instead.

6) Christmas presents in Greece aren’t delivered by Father Christmas but by Saint Basil.

7) Harper Lee’s friends gave her a year’s wages for Christmas 1956 so she could take time off to finish To Kill a Mockingbird.

8) Cary Grant and Clark Gable met once a year to exchange unwanted monogrammed Christmas gifts. 1,342

QI Facts To Leave You Flabbergasted is published by Faber & Faber Ltd.

This Victorian Christmas greetings card c1880 depicts a mouse riding a lobster. The card wishes the recipient 'Paix, Joie, Sante, Bonheur' or 'Peace, Joy, Health and Happiness'. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The book of weird and wonderful trivia is compiled by members of the team behind the BBC Television series QI including John Lloyd CBE, the show’s creator; John Mitchinson, QI’s first researcher; James Harkin, QI’s Head Elf and producer of QI’s BBC Radio 4 show The Museum of Curiosity; and Anne Miller, a scriptwriter and researcher for QI. Described as a portal, the book features 1,342 factual nuggets about which readers can find out more by visiting qi.com/1342 and entering the page number of the fact that interests them. The book comes 10 years after the publication of the first QI book, The Book of General Ignorance.

Here we bring you eight historical festive facts featured in 1,342 QI Facts To Leave You Flabbergasted…

1) In the 17th century, Christmas turkeys walked from East Anglia to London in three months.

2) Murderous frogs featured on Victorian Christmas cards, along with children being boiled in teapots and mice riding lobsters.

3) After noticing that she washed up bare-handed, Margaret Thatcher sent the Queen rubber gloves for Christmas.

4) The fake snow in The Wizard of Oz (1939) and White Christmas (1954) was made of asbestos.

American actors Bing Crosby, Rosemary Clooney, Vera-Ellen and Danny Kaye sing together in a scene from the 1954 film 'White Christmas'. (Photo by John Swope/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images)

5) Orthodox Jewish couples abstain from sex on Christmas Eve. Rabbis used to advise them to pass the time tearing toilet paper instead.

6) Christmas presents in Greece aren’t delivered by Father Christmas but by Saint Basil.

7) Harper Lee’s friends gave her a year’s wages for Christmas 1956 so she could take time off to finish To Kill a Mockingbird.

8) Cary Grant and Clark Gable met once a year to exchange unwanted monogrammed Christmas gifts. 1,342

QI Facts To Leave You Flabbergasted is published by Faber & Faber Ltd.

Published on December 27, 2016 02:00

December 26, 2016

Happy Boxing Day

December 26

Boxing Day - is a traditional celebration, dating back to medieval times, when gifts were given to employees, the poor, or to people in a lower social class.

What is Boxing Day?

Boxing Day is a national Bank Holiday, a day to spend with family and friends and to eat up all the leftovers of Christmas Day. The origins of the day, however, are steeped in history and tradition.

Read More

Boxing Day - is a traditional celebration, dating back to medieval times, when gifts were given to employees, the poor, or to people in a lower social class.

What is Boxing Day?

Boxing Day is a national Bank Holiday, a day to spend with family and friends and to eat up all the leftovers of Christmas Day. The origins of the day, however, are steeped in history and tradition.

Read More

Published on December 26, 2016 04:00

December 25, 2016

Merry Christmas

Published on December 25, 2016 04:00

December 24, 2016

Medieval Christmas: how was it celebrated?

History Extra

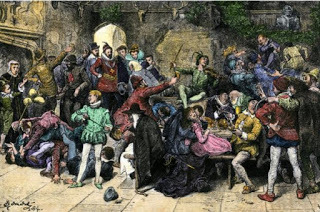

Christmas merriment in an old English manor in the 1500s. (© North Wind Picture Archives/Alamy)

1) Don’t go over the top

Medieval Christmas wasn’t quite the all-encompassing celebration it often is today, so relax a little. Christmas, the Feast of Jesus’s Nativity, was important, but more significant was Easter, and perhaps also the Annunciation – that moment celebrated on 25 March when God was supposedly conceived in Mary’s womb.

2) Be wary

Much of the medieval world didn’t celebrate Christmas, and if you were a medieval Jew, Christmas could be a time of danger. At Korneuburg in around 1305, townsfolk accused the Jews of procuring a consecrated communion wafer at Christmas and desecrating it, whereupon it ‘bubbled blood-drops, like an egg sweats when it is cooked’. Stories like these – imagining Jews conspiring to attack Jesus’ vulnerable body, present in the wafer – could lead to terrible reprisals.

The medieval Muslim scholar Ibn Taymiyya (1263–1328) inveighed against those Muslims who adopted Christian festivities, particularly criticizing what he saw as an imitation of Christmas in the celebration of the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday (mawlid).

3) Fast then feast

For those who did celebrate Christmas, it wasn’t just one day, but a season covering at least the 12 days from 25 December to Epiphany on 6 January. Sounds good? There’s a rider: Christmas was preceded by a month of fasting in the season of Advent. Advent was seen as a time of special preparation for God’s coming, his adventus, into the world – both in the infant Jesus, and at the end of time at the apocalypse.

Advent was supposed to be a time of exile, desire, longing, and repentance. So instead of trampling on your fellow shoppers, why not emulate medieval saints and trample on sin, temptation, and unfortunate demons?

If crushing demons is too much effort, at least keep rich foods off the menu. Fasting was central to the sacred rhythm of time in medieval Europe. (It’s no surprise that when reformers wanted to protest against the church in the 16th century, they held a sausage eat-in during a fast.)

4) Reign victorious

William the Conqueror was crowned on Christmas 1066. Christmas is a clever time to inaugurate a reign: you can nod to the classical imagery of an emperor’s triumphal entry into the city, his adventus. And since midwinter is too cold for battles, you can be, like Jesus, a prince of peace. Just as the kingdom of God entered the world in the infant Jesus, so too your reign could be born at Christmas.

William I the Conqueror (1027–87), being crowned king at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

5) Turn the world upside down

If your tastes don’t run to a full imperial coronation, why not celebrate Christmas by inverting the social hierarchy? Mirroring pagan traditions, inversions of order occurred across medieval society around Christmas. One of the most colourful was the election of a boy bishop, who presided over processions and church ritual on the Feast of the Holy Innocents (28 December).

In a surviving example of a boy bishop's sermon, the boy bishop wishes that all his schoolteachers would end up on the gallows at Tyburn. One chronicle records how, at the Abbey of St Gall in the 10th century, King Conrad tried to distract the procession of the boys by strewing apples down the processional route; the boys were, however, so disciplined that not an apple was touched. Inversion could, however, be less controlled: in 1523 at London’s Inns of Court, a ‘lord of misrule’ was responsible for a death.

6) To tree or not to tree?

Evergreen trees feature in the ritual life of many cultures, but medieval Christmas trees are hard to trace. We have stray references, particularly from the later middle ages, but their popularity exploded only in the 19th century.

Alternatively, decorate your house with candles (no electricity!), and holly and ivy. Gifts were more commonly given not on 25 December, but on New Year’s Day or elsewhere in the Christmas season.

7) Make mickle melodie

Carols multiplied in the late middle ages – a sign of Christmas’s rising importance. They are often ‘macaronic’ – uniting learned Latin with vernacular languages, and so mixing the high and low, divine and human, in textual form. As devotion to Mary increased, these Christmas songs often hymned her purity:

Ther is no rose of swych vertu As is the rose that bare Jhesu. Alleluya.

For in this rose conteynyd was Heuen and erthe in lytyl space, Res miranda (translation: what a wondrous thing).

Other carols were slightly less pious:

The boar’s head, I understand, Is chief service in all this land; Wheresoever it may be found, Servitur cum sinapio (translation: it is served with mustard).

Many of the medieval carols we sing today have had their rhythms regularised and their harmonies rewritten to suit later tastes. If you are a purist, return to the complex rhythms and intricate interweaving lines of manuscript carols. Or you might like to accompany carols with bagpipes, associated with shepherds watching their flocks.

Medieval singers. (© Mary Evans Picture Library/Alamy)

8) What to eat?

We know the boar’s head was on the medieval menu from the records of the Christmas feasting of Richard de Swinfield, Bishop of Hereford in the 13th century. Along with boar, Richard served beef, venison, partridges, geese, bread, cheese, ale and wine.

Christmas was also a time for charity and sharing food – at Christmas in 1314, some tenants at North Curry in Somerset received loaves of bread, beef and bacon with mustard, chicken soup, cheese and as much beer as they could drink for the day. Gifts of food were sometimes enforced: for the right to keep rabbits, the town of Lagrasse had to give their best bunny to the local monastery each Christmas.

One chief characteristic of medieval food was its seasonal variation, so you’ll need to source your food from what you have around you, flavoured with spices like pepper, ginger, cloves and saffron.

Foods you won’t see on the menu include chocolate and turkey, first brought to Spain under Ferdinand II in the 16th century.

9) Have a vision

Biblical accounts of Jesus’s birth were often supplemented by other stories or visions in the medieval world. If a vision is not granted to you, you might piously meditate on those of St Bridget of Sweden, a saint from the 14th century: Bridget saw Mary’s womb “very heavy and swollen”, and, as she prayed, “the infant in the womb moved, and at that very moment, in the flash of an eye, [Mary] gave birth to her son”.

10) Build a crib

To complete your medieval Christmas, set up a nativity scene in a cave. I know what you’re thinking: wouldn’t a stable or inn be more biblical? Don’t stress about this kind of historical accuracy – it didn’t really become a consideration until the 16th-century.

You’ll be following the example of St Francis, who famously set up a nativity in a cave at Greccio. The earliest accounts record that Francis was so moved by the crib that as he spoke the word ‘Bethlehem’ during the Christmas Mass, his voice sounded like the bleating of a lamb.

Dr Matthew Champion is a research fellow in medieval and early modern history at St Catharine's College Cambridge.

Christmas merriment in an old English manor in the 1500s. (© North Wind Picture Archives/Alamy)

1) Don’t go over the top

Medieval Christmas wasn’t quite the all-encompassing celebration it often is today, so relax a little. Christmas, the Feast of Jesus’s Nativity, was important, but more significant was Easter, and perhaps also the Annunciation – that moment celebrated on 25 March when God was supposedly conceived in Mary’s womb.

2) Be wary

Much of the medieval world didn’t celebrate Christmas, and if you were a medieval Jew, Christmas could be a time of danger. At Korneuburg in around 1305, townsfolk accused the Jews of procuring a consecrated communion wafer at Christmas and desecrating it, whereupon it ‘bubbled blood-drops, like an egg sweats when it is cooked’. Stories like these – imagining Jews conspiring to attack Jesus’ vulnerable body, present in the wafer – could lead to terrible reprisals.

The medieval Muslim scholar Ibn Taymiyya (1263–1328) inveighed against those Muslims who adopted Christian festivities, particularly criticizing what he saw as an imitation of Christmas in the celebration of the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday (mawlid).

3) Fast then feast

For those who did celebrate Christmas, it wasn’t just one day, but a season covering at least the 12 days from 25 December to Epiphany on 6 January. Sounds good? There’s a rider: Christmas was preceded by a month of fasting in the season of Advent. Advent was seen as a time of special preparation for God’s coming, his adventus, into the world – both in the infant Jesus, and at the end of time at the apocalypse.

Advent was supposed to be a time of exile, desire, longing, and repentance. So instead of trampling on your fellow shoppers, why not emulate medieval saints and trample on sin, temptation, and unfortunate demons?

If crushing demons is too much effort, at least keep rich foods off the menu. Fasting was central to the sacred rhythm of time in medieval Europe. (It’s no surprise that when reformers wanted to protest against the church in the 16th century, they held a sausage eat-in during a fast.)

4) Reign victorious

William the Conqueror was crowned on Christmas 1066. Christmas is a clever time to inaugurate a reign: you can nod to the classical imagery of an emperor’s triumphal entry into the city, his adventus. And since midwinter is too cold for battles, you can be, like Jesus, a prince of peace. Just as the kingdom of God entered the world in the infant Jesus, so too your reign could be born at Christmas.

William I the Conqueror (1027–87), being crowned king at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

5) Turn the world upside down

If your tastes don’t run to a full imperial coronation, why not celebrate Christmas by inverting the social hierarchy? Mirroring pagan traditions, inversions of order occurred across medieval society around Christmas. One of the most colourful was the election of a boy bishop, who presided over processions and church ritual on the Feast of the Holy Innocents (28 December).

In a surviving example of a boy bishop's sermon, the boy bishop wishes that all his schoolteachers would end up on the gallows at Tyburn. One chronicle records how, at the Abbey of St Gall in the 10th century, King Conrad tried to distract the procession of the boys by strewing apples down the processional route; the boys were, however, so disciplined that not an apple was touched. Inversion could, however, be less controlled: in 1523 at London’s Inns of Court, a ‘lord of misrule’ was responsible for a death.

6) To tree or not to tree?

Evergreen trees feature in the ritual life of many cultures, but medieval Christmas trees are hard to trace. We have stray references, particularly from the later middle ages, but their popularity exploded only in the 19th century.

Alternatively, decorate your house with candles (no electricity!), and holly and ivy. Gifts were more commonly given not on 25 December, but on New Year’s Day or elsewhere in the Christmas season.

7) Make mickle melodie

Carols multiplied in the late middle ages – a sign of Christmas’s rising importance. They are often ‘macaronic’ – uniting learned Latin with vernacular languages, and so mixing the high and low, divine and human, in textual form. As devotion to Mary increased, these Christmas songs often hymned her purity:

Ther is no rose of swych vertu As is the rose that bare Jhesu. Alleluya.

For in this rose conteynyd was Heuen and erthe in lytyl space, Res miranda (translation: what a wondrous thing).

Other carols were slightly less pious:

The boar’s head, I understand, Is chief service in all this land; Wheresoever it may be found, Servitur cum sinapio (translation: it is served with mustard).

Many of the medieval carols we sing today have had their rhythms regularised and their harmonies rewritten to suit later tastes. If you are a purist, return to the complex rhythms and intricate interweaving lines of manuscript carols. Or you might like to accompany carols with bagpipes, associated with shepherds watching their flocks.

Medieval singers. (© Mary Evans Picture Library/Alamy)

8) What to eat?

We know the boar’s head was on the medieval menu from the records of the Christmas feasting of Richard de Swinfield, Bishop of Hereford in the 13th century. Along with boar, Richard served beef, venison, partridges, geese, bread, cheese, ale and wine.

Christmas was also a time for charity and sharing food – at Christmas in 1314, some tenants at North Curry in Somerset received loaves of bread, beef and bacon with mustard, chicken soup, cheese and as much beer as they could drink for the day. Gifts of food were sometimes enforced: for the right to keep rabbits, the town of Lagrasse had to give their best bunny to the local monastery each Christmas.

One chief characteristic of medieval food was its seasonal variation, so you’ll need to source your food from what you have around you, flavoured with spices like pepper, ginger, cloves and saffron.

Foods you won’t see on the menu include chocolate and turkey, first brought to Spain under Ferdinand II in the 16th century.

9) Have a vision

Biblical accounts of Jesus’s birth were often supplemented by other stories or visions in the medieval world. If a vision is not granted to you, you might piously meditate on those of St Bridget of Sweden, a saint from the 14th century: Bridget saw Mary’s womb “very heavy and swollen”, and, as she prayed, “the infant in the womb moved, and at that very moment, in the flash of an eye, [Mary] gave birth to her son”.

10) Build a crib

To complete your medieval Christmas, set up a nativity scene in a cave. I know what you’re thinking: wouldn’t a stable or inn be more biblical? Don’t stress about this kind of historical accuracy – it didn’t really become a consideration until the 16th-century.

You’ll be following the example of St Francis, who famously set up a nativity in a cave at Greccio. The earliest accounts record that Francis was so moved by the crib that as he spoke the word ‘Bethlehem’ during the Christmas Mass, his voice sounded like the bleating of a lamb.

Dr Matthew Champion is a research fellow in medieval and early modern history at St Catharine's College Cambridge.

Published on December 24, 2016 02:00

December 23, 2016

Face of King Robert The Bruce is Brought Back to Life 700 Years After His Death

Ancient Origins

Almost 700 years after his death, a team of scientists and historians have produced comprehensive virtual images of the face of Robert the Bruce, a 14th century King of Scotland, and one of the most famous warriors of his generation, eventually leading Scotland during the Wars of Scottish Independence against England.

The images were recreated from the cast of a human skull held by the Hunterian Museum and are the result of a two-year research project by researchers at universities in Glasgow and Liverpool.

Robert the Bruce Arguably the Greatest Scottish Historical Figure of All Time

Even though most historians will agree that Robert the Bruce is the greatest of all Scottish heroes, the famous Mel Gibson’s movie Braveheart gave all the heroics to his compatriot William Wallace, making Bruce out to be nothing more than a self-serving opportunist. In reality, however, Robert Bruce played probably the most significant role in Scotland’s national resistance that later developed into a war of independence. After many years of bloody and heroic battles that lasted for nearly three decades, in 1320 Bruce and the Scottish nobles issued the Declaration of Arbroath asserting Scottish Independence, “For as longs as one hundred of us shall remain alive we shall never in any wise consent to submit to the rule of the English, for it is not for glory that we fight … but for freedom alone”.

However, a truce with Edward II of England failed to stop hostilities which continued until Edward II was deposed in 1327. The Treaty of Edinburgh between Robert Bruce and Edward III in 1328 recognized Scotland's independence, ending the 30 years of Wars of Independence. Edward agreed to the marriage of Robert Bruce’s son David to his younger sister Joan daughter of Edward II. Robert Bruce died at his house in Cardross a year later of a serious illness described by some as leprosy.

Statue of Robert the Bruce (1929) in front of the gates at Edinburgh Castle. (CC by SA 3.0 / Ad Meskens)

The Reconstructed Face of Robert the Bruce Shows that He Could Have Had Leprosy

Robert the Bruce actually did suffer from leprosy, according to the conclusions of the scientists after recreating his face from his skull. For years, scholars have argued about whether the legendary Scottish king was infected with the disease, with some suggesting there was a medieval cover-up so he would not have to relinquish the throne, while others claiming that he was the victim of a smear campaign. However, his newly reconstructed images of his face highlight that his skull shows the telltale signs of leprosy, including a disfigured jaw and nose. Professor Caroline Wilkinson, director of the Face Lab at LJMU, who also reconstructed the face of Richard III, said at Archaeology News Network, “We could accurately establish the muscle formation from the positions of the skull bones to determine the shape and structure of the face. We produced two versions – one without leprosy and one with a mild representation of leprosy. He may have had leprosy, but if he did it is likely that it did not manifest strongly on his face.”

Two versions of Robert the Bruce’s face were produced. This one shows how he may have looked after leprosy disfigured his face. Credit: FaceLab / Liverpool John Moores University.

DNA Could Answer Many Questions About the Legendary Scottish King Even though we do not have any reliable visual depictions of Robert the Bruce and all the written records referring to him tell us nothing about his appearance, the good news is that DNA testing could offer us all the information we need to establish his hair and eye color. However, there is a problem according to Dr. Martin MacGregor, a senior lecturer in Scottish history at the University of Glasgow and the project’s leader, “The skull was excavated in 1818-19 from a grave in Dunfermline Abbey, mausoleum of Scotland’s medieval monarchs. After the excavation the original skeleton and skull were sealed in pitch and reburied, but not before a cast of the head was taken. Several copies of the cast exist, including the one now in The Hunterian, but without the original bone we have no DNA.” Professor Wilkinson adds: “In the absence of any DNA, we relied on statistical evaluation to determine that Robert the Bruce most likely had brown hair and light brown eyes.” And continues saying that for now this is the most realistic image we can have about Bruce’s appearance, “This is the most realistic appearance of Robert the Bruce to-date, based on all the skeletal and historical material available.”

The plaster cast of Robert the Bruce’s skull (CC by SA 3.0)

Top image: The digitally-reconstructed image of the face of Robert the Bruce. Credit: FaceLab / Liverpool John Moores University.

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Almost 700 years after his death, a team of scientists and historians have produced comprehensive virtual images of the face of Robert the Bruce, a 14th century King of Scotland, and one of the most famous warriors of his generation, eventually leading Scotland during the Wars of Scottish Independence against England.

The images were recreated from the cast of a human skull held by the Hunterian Museum and are the result of a two-year research project by researchers at universities in Glasgow and Liverpool.

Robert the Bruce Arguably the Greatest Scottish Historical Figure of All Time

Even though most historians will agree that Robert the Bruce is the greatest of all Scottish heroes, the famous Mel Gibson’s movie Braveheart gave all the heroics to his compatriot William Wallace, making Bruce out to be nothing more than a self-serving opportunist. In reality, however, Robert Bruce played probably the most significant role in Scotland’s national resistance that later developed into a war of independence. After many years of bloody and heroic battles that lasted for nearly three decades, in 1320 Bruce and the Scottish nobles issued the Declaration of Arbroath asserting Scottish Independence, “For as longs as one hundred of us shall remain alive we shall never in any wise consent to submit to the rule of the English, for it is not for glory that we fight … but for freedom alone”.

However, a truce with Edward II of England failed to stop hostilities which continued until Edward II was deposed in 1327. The Treaty of Edinburgh between Robert Bruce and Edward III in 1328 recognized Scotland's independence, ending the 30 years of Wars of Independence. Edward agreed to the marriage of Robert Bruce’s son David to his younger sister Joan daughter of Edward II. Robert Bruce died at his house in Cardross a year later of a serious illness described by some as leprosy.

Statue of Robert the Bruce (1929) in front of the gates at Edinburgh Castle. (CC by SA 3.0 / Ad Meskens)

The Reconstructed Face of Robert the Bruce Shows that He Could Have Had Leprosy

Robert the Bruce actually did suffer from leprosy, according to the conclusions of the scientists after recreating his face from his skull. For years, scholars have argued about whether the legendary Scottish king was infected with the disease, with some suggesting there was a medieval cover-up so he would not have to relinquish the throne, while others claiming that he was the victim of a smear campaign. However, his newly reconstructed images of his face highlight that his skull shows the telltale signs of leprosy, including a disfigured jaw and nose. Professor Caroline Wilkinson, director of the Face Lab at LJMU, who also reconstructed the face of Richard III, said at Archaeology News Network, “We could accurately establish the muscle formation from the positions of the skull bones to determine the shape and structure of the face. We produced two versions – one without leprosy and one with a mild representation of leprosy. He may have had leprosy, but if he did it is likely that it did not manifest strongly on his face.”

Two versions of Robert the Bruce’s face were produced. This one shows how he may have looked after leprosy disfigured his face. Credit: FaceLab / Liverpool John Moores University.

DNA Could Answer Many Questions About the Legendary Scottish King Even though we do not have any reliable visual depictions of Robert the Bruce and all the written records referring to him tell us nothing about his appearance, the good news is that DNA testing could offer us all the information we need to establish his hair and eye color. However, there is a problem according to Dr. Martin MacGregor, a senior lecturer in Scottish history at the University of Glasgow and the project’s leader, “The skull was excavated in 1818-19 from a grave in Dunfermline Abbey, mausoleum of Scotland’s medieval monarchs. After the excavation the original skeleton and skull were sealed in pitch and reburied, but not before a cast of the head was taken. Several copies of the cast exist, including the one now in The Hunterian, but without the original bone we have no DNA.” Professor Wilkinson adds: “In the absence of any DNA, we relied on statistical evaluation to determine that Robert the Bruce most likely had brown hair and light brown eyes.” And continues saying that for now this is the most realistic image we can have about Bruce’s appearance, “This is the most realistic appearance of Robert the Bruce to-date, based on all the skeletal and historical material available.”

The plaster cast of Robert the Bruce’s skull (CC by SA 3.0)

Top image: The digitally-reconstructed image of the face of Robert the Bruce. Credit: FaceLab / Liverpool John Moores University.

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on December 23, 2016 01:30

December 22, 2016

Q&A: How did the Normans learn to build castles?

History Extra

The Great Tower at Chepstow Castle, one of the earliest Norman stone structures in the British Isles. (© Tosca Weijers/Dreamstime.com)

The Normans, as is widely appreciated, were originally Norsemen: Vikings who settled in the area around the Seine estuary in the late ninth and early 10th centuries. The traditional date for the founding of Normandy is AD 911, when the authority of the Norman leader, Rollo, was recognised by the king of France.

Castles appeared somewhat later, with the earliest examples being constructed around the turn of the first millennium. They differed from earlier fortifications by being smaller and taller: the distinctive feature of early castle design was the great artificial mound of earth, or motte. Dating a mound of earth is difficult, since it relies on the discovery of datable ‘small finds’, and so establishing a precise chronology for mottes is impossible. Nor is it possible to say for certain how and why the design originated, other than to observe that the rise of castles seems to coincide with an intensification of lordship across northern France in the decades around the millennium. Evidently someone had the notion of building a great mound of earth to assert his power and the idea caught on fast.

The Normans began ditching their Norse culture and adopting French customs almost from the minute of their arrival. During the 10th century, for example, they embraced Christianity, the French language and the habit of fighting on horseback. Learning how to build castles was therefore simply part of an ongoing process of acculturation. According to contemporary chroniclers, a great surge of castle-building took place during the troubled years of William the Conqueror’s boyhood in the 1030s and 1040s.

“Lots of Normans, forgetful of their loyalties, built earthworks in many places,” wrote William of Jumièges, “and erected fortified strongholds for their own purposes.”

Answered by Marc Morris, historian, author and broadcaster.

The Great Tower at Chepstow Castle, one of the earliest Norman stone structures in the British Isles. (© Tosca Weijers/Dreamstime.com)

The Normans, as is widely appreciated, were originally Norsemen: Vikings who settled in the area around the Seine estuary in the late ninth and early 10th centuries. The traditional date for the founding of Normandy is AD 911, when the authority of the Norman leader, Rollo, was recognised by the king of France.

Castles appeared somewhat later, with the earliest examples being constructed around the turn of the first millennium. They differed from earlier fortifications by being smaller and taller: the distinctive feature of early castle design was the great artificial mound of earth, or motte. Dating a mound of earth is difficult, since it relies on the discovery of datable ‘small finds’, and so establishing a precise chronology for mottes is impossible. Nor is it possible to say for certain how and why the design originated, other than to observe that the rise of castles seems to coincide with an intensification of lordship across northern France in the decades around the millennium. Evidently someone had the notion of building a great mound of earth to assert his power and the idea caught on fast.

The Normans began ditching their Norse culture and adopting French customs almost from the minute of their arrival. During the 10th century, for example, they embraced Christianity, the French language and the habit of fighting on horseback. Learning how to build castles was therefore simply part of an ongoing process of acculturation. According to contemporary chroniclers, a great surge of castle-building took place during the troubled years of William the Conqueror’s boyhood in the 1030s and 1040s.

“Lots of Normans, forgetful of their loyalties, built earthworks in many places,” wrote William of Jumièges, “and erected fortified strongholds for their own purposes.”

Answered by Marc Morris, historian, author and broadcaster.

Published on December 22, 2016 02:00

December 21, 2016

Archaeologists Explore Incredible Ancient City in Supposed Backwater Region of Greece

Ancient Origins

A collaboration between Greek, Swedish, and British researchers has resulted in some interesting discoveries at a previously unexplored 2,500-year-old city in Thessaly, Greece. Their findings are beginning to change the way archaeologists look at the region – an area which was previously believed to be “backwater during Antiquity.”

The Vlochos Archaeological Project (VLAP), which explored the site, reports that the group of researchers consists of scientists from the Ephorate of Antiquities of Karditsa (Greece), the University of Gothenburg (Sweden) and the University of Bournemouth (UK). They have just completed their first season exploring the ruins at a village called Vlochos in Thessaly, about a five-hour drive north of Athens.

The Cultural Past of Ancient Thessaly

Thessaly was one of the traditional regions of Ancient Greece. During the Mycenaean period, Thessaly was known as Aeolia, a term that continued to be used for one of the basic tribes of Greece, the Aeolians. Meteora: the Impressive Greek Monasteries Suspended in the Air Five Legendary Lost Cities that have Never Been Found

At its greatest extent, ancient Thessaly was a wide area stretching from Mount Olympus (home of the Greek Gods) to the north to the Spercheios Valley to the south. It was home to extensive Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures around 6000 BC-2500 BC. Mycenaean settlements have also been found in Thessaly – for example, tablets bearing Mycenaean Greek inscriptions, written in Linear B, were found at the Kastron of Palaia Hill, in Volos.

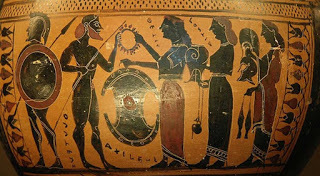

In Greek mythology, Thessaly was the homeland of the heroes Achilles, Jason, and of course, the legendary tribe of Myrmidons. Homer's Iliad said that the Myrmidons were led by Achilles during the Trojan War. According to Greek myths, they were created by Zeus from a colony of ants and therefore took their name from the Greek word for ant, myrmex.

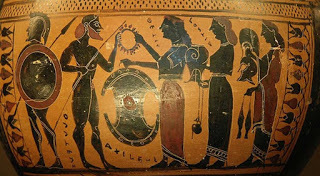

Thetis giving her son Achilles weapons forged by Hephaestus. Detail on an Attic black-figure hydria from 575–550 BC. ( Public Domain )

An Untapped Find The head of the team, Robin Rönnlund, told The Local that some of the remains in the area were known but had been dismissed before as part of an irrelevant little settlement on a hill. It wasn’t until Rönnlund and his colleagues began searching the location that it turned out to be way bigger in size and archaeological significance than they could have dreamed.

Aerial view showing the outline of fortress walls, towers, and city gates. ( University of Gothenburg)

As Rönnlund explained to The Local , “It feels great. I think it is [an] incredibly big [deal], because it's something thought to be a small village that turns out to be a city, with a structured network of streets and a square. A colleague and I came across the site in connection with another project last year, and we realized the great potential right away. The fact that nobody has ever explored the hill before is a mystery."

Archaeologist Johan Klange measuring the Classical-Hellenistic fortifications on the hill of Strongilovoúni. ( VLAP)

Finds from 500 BC The team discovered the ruins of towers, walls, and city gates on the summit and slopes of the hill. Additionally, during their first two weeks of field work in September, they found ancient pottery and coins, dating back to around 500 BC. After that, the city is thought to have prospered from the 4th to 3rd century BC before it was abandoned – possibly when the Romans took over the area.

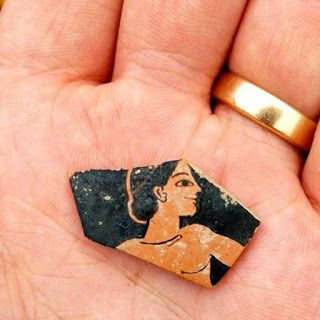

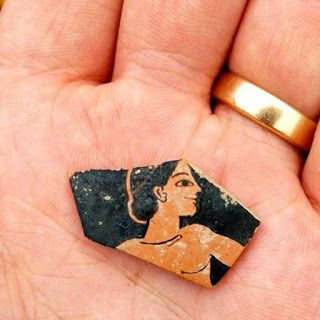

Fragment of red-figure pottery discovered at the site. It is from the late 6th century BC and probably by Attic painter Paseas. ( University of Gothenburg )

Rönnlund hopes that his team won’t need to excavate the site. Instead, they would prefer to use methods such as ground-penetrating radar, which will allow them to leave it in the same condition as they found it.

A second field project is planned for August next year and Rönnlund is optimistic about the future finds and results. He said :

"Very little is known about ancient cities in the region, and many researchers have previously believed that western Thessaly was somewhat of a backwater during Antiquity. Our project therefore fills an important gap in the knowledge about the area and shows that a lot remains to be discovered in the Greek soil.”

The site with the road leading up towards it. ( Swedish Institute at Athens )

Top Image: The city’s acropolis is barely visible on the hill on a cloudy day. Source: University of Gothenburg

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A collaboration between Greek, Swedish, and British researchers has resulted in some interesting discoveries at a previously unexplored 2,500-year-old city in Thessaly, Greece. Their findings are beginning to change the way archaeologists look at the region – an area which was previously believed to be “backwater during Antiquity.”

The Vlochos Archaeological Project (VLAP), which explored the site, reports that the group of researchers consists of scientists from the Ephorate of Antiquities of Karditsa (Greece), the University of Gothenburg (Sweden) and the University of Bournemouth (UK). They have just completed their first season exploring the ruins at a village called Vlochos in Thessaly, about a five-hour drive north of Athens.

The Cultural Past of Ancient Thessaly

Thessaly was one of the traditional regions of Ancient Greece. During the Mycenaean period, Thessaly was known as Aeolia, a term that continued to be used for one of the basic tribes of Greece, the Aeolians. Meteora: the Impressive Greek Monasteries Suspended in the Air Five Legendary Lost Cities that have Never Been Found

At its greatest extent, ancient Thessaly was a wide area stretching from Mount Olympus (home of the Greek Gods) to the north to the Spercheios Valley to the south. It was home to extensive Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures around 6000 BC-2500 BC. Mycenaean settlements have also been found in Thessaly – for example, tablets bearing Mycenaean Greek inscriptions, written in Linear B, were found at the Kastron of Palaia Hill, in Volos.

In Greek mythology, Thessaly was the homeland of the heroes Achilles, Jason, and of course, the legendary tribe of Myrmidons. Homer's Iliad said that the Myrmidons were led by Achilles during the Trojan War. According to Greek myths, they were created by Zeus from a colony of ants and therefore took their name from the Greek word for ant, myrmex.

Thetis giving her son Achilles weapons forged by Hephaestus. Detail on an Attic black-figure hydria from 575–550 BC. ( Public Domain )

An Untapped Find The head of the team, Robin Rönnlund, told The Local that some of the remains in the area were known but had been dismissed before as part of an irrelevant little settlement on a hill. It wasn’t until Rönnlund and his colleagues began searching the location that it turned out to be way bigger in size and archaeological significance than they could have dreamed.

Aerial view showing the outline of fortress walls, towers, and city gates. ( University of Gothenburg)

As Rönnlund explained to The Local , “It feels great. I think it is [an] incredibly big [deal], because it's something thought to be a small village that turns out to be a city, with a structured network of streets and a square. A colleague and I came across the site in connection with another project last year, and we realized the great potential right away. The fact that nobody has ever explored the hill before is a mystery."

Archaeologist Johan Klange measuring the Classical-Hellenistic fortifications on the hill of Strongilovoúni. ( VLAP)

Finds from 500 BC The team discovered the ruins of towers, walls, and city gates on the summit and slopes of the hill. Additionally, during their first two weeks of field work in September, they found ancient pottery and coins, dating back to around 500 BC. After that, the city is thought to have prospered from the 4th to 3rd century BC before it was abandoned – possibly when the Romans took over the area.

Fragment of red-figure pottery discovered at the site. It is from the late 6th century BC and probably by Attic painter Paseas. ( University of Gothenburg )

Rönnlund hopes that his team won’t need to excavate the site. Instead, they would prefer to use methods such as ground-penetrating radar, which will allow them to leave it in the same condition as they found it.

A second field project is planned for August next year and Rönnlund is optimistic about the future finds and results. He said :

"Very little is known about ancient cities in the region, and many researchers have previously believed that western Thessaly was somewhat of a backwater during Antiquity. Our project therefore fills an important gap in the knowledge about the area and shows that a lot remains to be discovered in the Greek soil.”

The site with the road leading up towards it. ( Swedish Institute at Athens )

Top Image: The city’s acropolis is barely visible on the hill on a cloudy day. Source: University of Gothenburg

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on December 21, 2016 02:00