MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 73

December 10, 2016

Norwegian Archaeologists Have Found the Shrine of a Miracle-Making Viking King

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists think they have found a shrine dedicated to the Viking king Olaf Haraldsson in the ruins of a church in Trondheim, Norway. The team of archaeologists from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) have discovered the foundations of the church where King Olaf II is believed to have been buried after he was canonized.

The foundations of a church where Viking King Olaf Haraldsson’s body may have been enshrined after he was declared a saint. (Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU))

The King that Became a Saint

Olaf II Haraldsson, also called "the Fat" or "the Stout" during his lifetime, was born in 995 (the year in which Olaf Tryggvessön arrived in Norway.) After fighting the Danes in England, Olaf Haraldsson returned to Norway in 1015 and declared himself king. He obtained the support of the five petty kings of the Uplands. He was the King of Norway from 1016-1029.

The king was posthumously given the title Rex Perpetuus Norvegiae (Eternal King of Norway) and was canonized in Trondheim by Bishop Grimkell one year after his death in the Battle of Stiklestad on July 29, 1030. He is also a canonized as a saint of the Eastern Orthodox Church and is one of the very few famous Western saints before the Great Schism between the Eastern Church and the Western Church in 1054. The pope confirmed St. Olaf's canonization as a saint in 1164.

However, many contemporary historians consider that King Olaf II was inclined to violence and brutality, and they accuse earlier scholars of neglecting this side of his character. Especially during the period of Romantic Nationalism, Olaf was a symbol of national independence and pride. Regardless of the controversy between scholars and historians about Olaf’s personality, the fact remains that he was the last Western saint accepted by the Eastern Orthodox Church and an important figure in Norwegian history.

Statue of St. Olaf (Olav) in Austevoll Church. (Nina Aldin Thune/CC BY SA 2.5)

The Church Where Olaf Haraldsson was Enshrined as a Saint Olaf Haraldsson was buried in Nidaros (modern-day Trondheim) and very quickly stories sprang up of miraculous occurrences at his grave site. For this reason, his body was transferred to a location of honor above the high altar of St. Clement’s church - a wood stave church which Olaf had built a few years before his death.

However, his body was returned to Nidaros some decades later, this time in a bigger and more glamorous site that could accommodate the increasing number of pilgrims dedicated to the cult of Saint Olaf. With the passage of time, St. Clement’s was destroyed and its location forgotten.

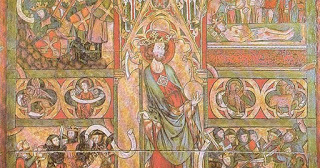

The death of King Olaf. (Public Domain)

Fast forward to 2016, when NIKU announced on November 11 that its team of researchers had discovered the foundations of a wooden church where the body of the Viking king may have been enshrined after he was declared a saint. The discovery was made during an excavation on Søndre Gate Street in Trondheim. Preliminary dating indicates the structure was built in the 11th century.

During the excavation, the archaeologists uncovered a small rectangular stone-built platform at the building’s east end. This is probably the foundation for an altar, and it may be the very same site where St. Olaf’s coffin was placed in 1031. A small well was also found which researchers believe could be a holy well associated with the saint.

The excavation’s director Anna Petersén concluded, “This is a unique site in Norwegian history in terms of religion, culture and politics. Much of the Norwegian national identity has been established on the cult of sainthood surrounding St. Olaf, and it was here it all began!”

The slab which archaeologists believe may have been the base of the altar where King Olaf Haraldsson’s coffin was laid. (NIKU)

Top Image: A depiction of King Olaf Haraldsson from the Trondheim cathedral. Source: Public Domain

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Archaeologists think they have found a shrine dedicated to the Viking king Olaf Haraldsson in the ruins of a church in Trondheim, Norway. The team of archaeologists from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) have discovered the foundations of the church where King Olaf II is believed to have been buried after he was canonized.

The foundations of a church where Viking King Olaf Haraldsson’s body may have been enshrined after he was declared a saint. (Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU))

The King that Became a Saint

Olaf II Haraldsson, also called "the Fat" or "the Stout" during his lifetime, was born in 995 (the year in which Olaf Tryggvessön arrived in Norway.) After fighting the Danes in England, Olaf Haraldsson returned to Norway in 1015 and declared himself king. He obtained the support of the five petty kings of the Uplands. He was the King of Norway from 1016-1029.

The king was posthumously given the title Rex Perpetuus Norvegiae (Eternal King of Norway) and was canonized in Trondheim by Bishop Grimkell one year after his death in the Battle of Stiklestad on July 29, 1030. He is also a canonized as a saint of the Eastern Orthodox Church and is one of the very few famous Western saints before the Great Schism between the Eastern Church and the Western Church in 1054. The pope confirmed St. Olaf's canonization as a saint in 1164.

However, many contemporary historians consider that King Olaf II was inclined to violence and brutality, and they accuse earlier scholars of neglecting this side of his character. Especially during the period of Romantic Nationalism, Olaf was a symbol of national independence and pride. Regardless of the controversy between scholars and historians about Olaf’s personality, the fact remains that he was the last Western saint accepted by the Eastern Orthodox Church and an important figure in Norwegian history.

Statue of St. Olaf (Olav) in Austevoll Church. (Nina Aldin Thune/CC BY SA 2.5)

The Church Where Olaf Haraldsson was Enshrined as a Saint Olaf Haraldsson was buried in Nidaros (modern-day Trondheim) and very quickly stories sprang up of miraculous occurrences at his grave site. For this reason, his body was transferred to a location of honor above the high altar of St. Clement’s church - a wood stave church which Olaf had built a few years before his death.

However, his body was returned to Nidaros some decades later, this time in a bigger and more glamorous site that could accommodate the increasing number of pilgrims dedicated to the cult of Saint Olaf. With the passage of time, St. Clement’s was destroyed and its location forgotten.

The death of King Olaf. (Public Domain)

Fast forward to 2016, when NIKU announced on November 11 that its team of researchers had discovered the foundations of a wooden church where the body of the Viking king may have been enshrined after he was declared a saint. The discovery was made during an excavation on Søndre Gate Street in Trondheim. Preliminary dating indicates the structure was built in the 11th century.

During the excavation, the archaeologists uncovered a small rectangular stone-built platform at the building’s east end. This is probably the foundation for an altar, and it may be the very same site where St. Olaf’s coffin was placed in 1031. A small well was also found which researchers believe could be a holy well associated with the saint.

The excavation’s director Anna Petersén concluded, “This is a unique site in Norwegian history in terms of religion, culture and politics. Much of the Norwegian national identity has been established on the cult of sainthood surrounding St. Olaf, and it was here it all began!”

The slab which archaeologists believe may have been the base of the altar where King Olaf Haraldsson’s coffin was laid. (NIKU)

Top Image: A depiction of King Olaf Haraldsson from the Trondheim cathedral. Source: Public Domain

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on December 10, 2016 01:30

December 9, 2016

Remains of a 7,000-Year-Old Lost City Discovered in Egypt

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists working in Egypt have made an unprecedented find of a previously unknown city containing huts, iron and stone tools, pottery, and even a small cemetery in the southern province of Sohag. The Guardian reports that the archaeologists unearthed their fantastic find just 400 meters (1312.34 ft.) from the Temple of Seti I, across the Nile from Luxor. It is believed that the forgotten city once housed high-ranking officials and grave builders and dates to about 5316 BC.

A section of the newly-discovered site with some artifacts found within it. (Ministry of Antiquities)

So far, the archaeologists have found 15 large mastabas (mudbrick tombs). However, this may be a question of quality over quantity, as Antiquities Minister Mahmoud Afifi said in a statement:

“The size of the graves discovered in the cemetery is larger in some instances than royal graves in Abydos dating back to the first dynasty, which proves the importance of the people buried there and their high social standing during this early era of ancient Egyptian history.”

One of the excavated graves. (Ministry of Antiquities)

Egypt Independent says the excavations are underway by an Egyptian archaeological mission belonging to the Ministry of Antiquities. The group consists of “young Egyptian archaeologists specialized in excavations, pottery, paintings and human bones.”

The antiquities ministry hopes that the discovery will provide new information on Abydos, one of ancient Egypt’s oldest (3,100 – 332 BC) and most important archaeological sites.

The Abydos boats are some of the fascinating artifacts that have been found there during previous excavations. The large size and features of the boats suggest that they could have been used for sailing, however the funerary links tend to dominate over that idea.

Some of the Abydos boats in their brick-built graves. (Maritimehistorypodcast.com)

Yet, one of the most memorable features of Abydos is the temple of Seti I. The iconic structure was built mainly of limestone, though some sections were made with sandstone. Ancient Origins writer Dwhty provides more information on the temple’s characteristics:

“Seti’s temple was dedicated to Osiris, and consisted of a pylon, two open courts, two hypostyle halls, seven shrines, each to an important Egyptian deity (Horus, Isis, Osiris, Amun-Ra, Ra-Horakhty and Ptah) and one to Seti himself, a chapel dedicated to the different forms of the god Osiris, and several chambers to the south. In addition to the main temple, there was also an Osireion at the back of it. Various additions to the temple were made by later pharaohs, including those from the Late, Ptolemaic and Roman periods.”

Entrance to the Temple of Seti I. (Hannah Pethen /CC BY SA 2.0)

This temple in Abydos is among the most famous in the country and some scholars claim it is the “most impressive religious structure still standing in Egypt.” Even though Seti I began the work on the temple, it was not completed until his son, Ramesses II, reigned. Despite Seti bringing order back to Egypt following the disruption caused by Akhenaten’s religious reforms, his story is largely overshadowed by his more famous son.

Regarding the pharaoh and his kin, within Seti I’s temple, one can find the well-known Abydos King List. This is a list of 76 Egyptian kings which has proven itself a useful tool in deciphering ancient Egyptian history – even if it is not complete.

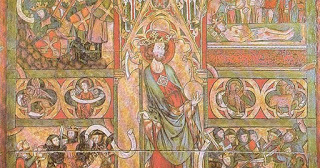

Drawing of cartouches on the Abydos King List. (PLstrom/CC BY SA 3.0)

But there may be even more intriguing information tucked away in the Temple of Seti I. John Black described one of the more controversial finds made within Seti’s temple for Ancient Origins.

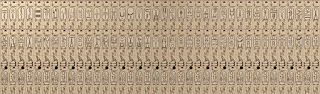

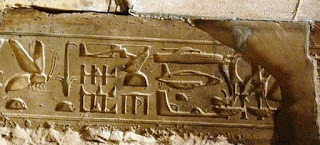

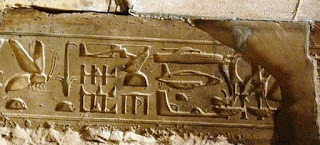

He wrote: “On one of the ceilings of the temple, strange hieroglyphs were found that sparked a debate between Egyptologists. The carvings appear to depict modern vehicles resembling a helicopter, a submarine, and airplanes. At first the images circulating were thought to be fakes, but were later filmed and verified as valid images. Yet, even if these images clearly appear to resemble twentieth century machines, Egyptologists have tried to offer a rational explanation.”

Hieroglyphs showing seemingly modern aircraft and vehicles in the Temple of Seti I in Abydos. (Public Domain)

Though debate continues about that provocative subject, the most recent find hints that there are still many secrets waiting to be exposed around the ancient Egyptian site of Abydos.

Top Image: Part of the excavated site. (Ministry of Antiquities)

By Alicia McDermott

Archaeologists working in Egypt have made an unprecedented find of a previously unknown city containing huts, iron and stone tools, pottery, and even a small cemetery in the southern province of Sohag. The Guardian reports that the archaeologists unearthed their fantastic find just 400 meters (1312.34 ft.) from the Temple of Seti I, across the Nile from Luxor. It is believed that the forgotten city once housed high-ranking officials and grave builders and dates to about 5316 BC.

A section of the newly-discovered site with some artifacts found within it. (Ministry of Antiquities)

So far, the archaeologists have found 15 large mastabas (mudbrick tombs). However, this may be a question of quality over quantity, as Antiquities Minister Mahmoud Afifi said in a statement:

“The size of the graves discovered in the cemetery is larger in some instances than royal graves in Abydos dating back to the first dynasty, which proves the importance of the people buried there and their high social standing during this early era of ancient Egyptian history.”

One of the excavated graves. (Ministry of Antiquities)

Egypt Independent says the excavations are underway by an Egyptian archaeological mission belonging to the Ministry of Antiquities. The group consists of “young Egyptian archaeologists specialized in excavations, pottery, paintings and human bones.”

The antiquities ministry hopes that the discovery will provide new information on Abydos, one of ancient Egypt’s oldest (3,100 – 332 BC) and most important archaeological sites.

The Abydos boats are some of the fascinating artifacts that have been found there during previous excavations. The large size and features of the boats suggest that they could have been used for sailing, however the funerary links tend to dominate over that idea.

Some of the Abydos boats in their brick-built graves. (Maritimehistorypodcast.com)

Yet, one of the most memorable features of Abydos is the temple of Seti I. The iconic structure was built mainly of limestone, though some sections were made with sandstone. Ancient Origins writer Dwhty provides more information on the temple’s characteristics:

“Seti’s temple was dedicated to Osiris, and consisted of a pylon, two open courts, two hypostyle halls, seven shrines, each to an important Egyptian deity (Horus, Isis, Osiris, Amun-Ra, Ra-Horakhty and Ptah) and one to Seti himself, a chapel dedicated to the different forms of the god Osiris, and several chambers to the south. In addition to the main temple, there was also an Osireion at the back of it. Various additions to the temple were made by later pharaohs, including those from the Late, Ptolemaic and Roman periods.”

Entrance to the Temple of Seti I. (Hannah Pethen /CC BY SA 2.0)

This temple in Abydos is among the most famous in the country and some scholars claim it is the “most impressive religious structure still standing in Egypt.” Even though Seti I began the work on the temple, it was not completed until his son, Ramesses II, reigned. Despite Seti bringing order back to Egypt following the disruption caused by Akhenaten’s religious reforms, his story is largely overshadowed by his more famous son.

Regarding the pharaoh and his kin, within Seti I’s temple, one can find the well-known Abydos King List. This is a list of 76 Egyptian kings which has proven itself a useful tool in deciphering ancient Egyptian history – even if it is not complete.

Drawing of cartouches on the Abydos King List. (PLstrom/CC BY SA 3.0)

But there may be even more intriguing information tucked away in the Temple of Seti I. John Black described one of the more controversial finds made within Seti’s temple for Ancient Origins.

He wrote: “On one of the ceilings of the temple, strange hieroglyphs were found that sparked a debate between Egyptologists. The carvings appear to depict modern vehicles resembling a helicopter, a submarine, and airplanes. At first the images circulating were thought to be fakes, but were later filmed and verified as valid images. Yet, even if these images clearly appear to resemble twentieth century machines, Egyptologists have tried to offer a rational explanation.”

Hieroglyphs showing seemingly modern aircraft and vehicles in the Temple of Seti I in Abydos. (Public Domain)

Though debate continues about that provocative subject, the most recent find hints that there are still many secrets waiting to be exposed around the ancient Egyptian site of Abydos.

Top Image: Part of the excavated site. (Ministry of Antiquities)

By Alicia McDermott

Published on December 09, 2016 02:00

December 8, 2016

The 5 greatest mysteries behind the Wars of the Roses

History Extra

The Young Princes in the Tower, 1831, by Paul de la Roche (1910). (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

5) What was really wrong with King Henry VI? Henry VI (1422–60 and 1470–71) was comfortably the most incompetent king of the whole Plantagenet line, and his benign but ultimately disastrous rule began the series of conflicts that we now call the Wars of the Roses.

The crisis broke in 1453 when Henry appears to have suffered a near-complete mental collapse. He stopped responding to other people; he didn’t recognise his own wife or newborn son; and for several months he was completely helpless and utterly withdrawn from the world. One contemporary said the king was “smitten with a frenzy”.

The obvious comparison was with Henry’s grandfather Charles VI of France, who had suffered similarly long bouts of madness in which he attacked his courtiers, smeared himself in his own waste and screamed that he felt thousands of sharp needles piercing his flesh.

So was Henry’s illness hereditary? And how would we diagnose it today? Catatonia? Schizophrenia? Severe depression? Medical diagnoses across the centuries are fraught with difficulties, and it is quite possible that we will never be able to say for sure. What we do know is that Henry’s debilitating illness had a correspondingly dreadful effect on both the man and his kingdom, as his subjects fought at first to save the realm, and then to steal control of it for themselves.

4) Were the Tudors really Tudors? The great survivors of the Wars of the Roses were a strange little half-Welsh, half-French family who took the surname Tidyr, or Tudur, or Tudor. Famously, it was Henry Tudor who emerged victorious from the battle of Bosworth in 1485 and, as Henry VII of England, went on to establish the most famous royal dynasty of them all.

But the origins of this remarkable family are surprisingly foggy. Their first connection to the English crown came through Henry VII’s grandmother, Catherine de Valois, widow of Henry V and mother of Henry VI. As dowager queen Catherine had caused quite a stir by secretly marrying her lowly servant, Owen Tudor. Plenty of romantic rumours have swirled around that union, but whatever the case, during the early 1430s Catherine gave birth to several children who took the Tudor name, most notably Henry VII’s father, Edmund Tudor, and another boy named Jasper Tudor.

But were they really Tudors? Intriguingly, shortly before Catherine became involved with Owen, there was a widespread suggestion that she was having an affair with Edmund Beaufort, the future duke of Somerset, who would be killed at the battle of St Albans in 1455. This rumour was taken so seriously that parliament took up the matter and issued a special statute restricting the right of queens of England to remarry.

Edmund Beaufort, c1450. Engraving taken from portrait painted by Hans Holbein the Younger. (Photo by Kean Collection/Getty Images)

It has been speculated that Catherine’s marriage to the lowly Owen Tudor was contracted to cover up her politically dangerous relationship with Edmund Beaufort. In that case, is it possible that Edmund Tudor was not a Tudor at all, but was actually given the forename of his real father?

The great 15th-century expert Gerald Harriss made precisely this suggestion in a fine footnote written in 1988:

“By its very nature the evidence for Edmund ‘Tudor's’ parentage is less than conclusive, but such facts as can be assembled permit the agreeable possibility that Edmund ‘Tudor’ and Margaret Beaufort [ie Edmund Tudor’s wife and Henry VII’s mother] were first cousins and that the royal house of ‘Tudor’ sprang in fact from Beauforts on both sides.”

Wouldn’t that be something?

3) Who was Edward IV’s real wife?

The history books usually state that Edward IV’s wife was Elizabeth Woodville (or ‘Wydeville’). That in itself is a delicious fact: when Edward married Elizabeth in 1464 she was of lowly rank, a widow with two children from her previous marriage and one of the king’s subjects, rather than a foreign princess. What’s more, Edward’s choice of queen upset his closest political ally, the earl of Warwick; caused diplomatic trouble with more than one other country; and annoyed a significant number of other English noble families.

But nothing caused quite so much trouble as the suggestion that Edward IV had in fact married someone else. Following the king’s death in 1483, his brother Richard duke of Gloucester claimed that, before the Woodville marriage took place, Edward IV had promised to marry Lady Eleanor Boteler (née Talbot), a daughter of the famous soldier John Talbot, earl of Shrewsbury.

In 1483 Richard argued that since Edward had once promised to marry Lady Eleanor, he had not subsequently been legally entitled to marry Elizabeth Woodville. This in turn made their union invalid, and their children bastards.

Elizabeth Woodville, 1463. (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

This claim was the basis of Richard’s usurpation of the crown. He made it known that Edward IV’s young son and successor, Edward V, was illegitimate, and instead claimed the throne for himself, as Richard III.

But was it true? Conveniently, in 1483 the case could not be properly tested, since Lady Eleanor had died 15 years previously. But today, those seeking to rehabilitate Richard III’s reputation frequently rely on the ‘pre-contract’ argument to defend his actions.

2) Did Richard III really kill the princes in the Tower?

Perhaps the greatest mystery of them all, and certainly the question most likely to start a fistfight among any given group of medievalists.

For centuries Richard III’s name has been blackened thanks to his usurpation of the throne in 1483 and the subsequent disappearance of his nephews, Edward V and Richard duke of York – better known as ‘the princes in the Tower’.

Did the boys really die? And if so, who was to blame? Did Richard have them murdered? Or did they die of natural causes? Were there other agents at work? And if so, who? Could it be, as one contemporary source suggested, that Richard’s sometime ally, the oily and feckless Henry Stafford, duke of Buckingham, was the prime mover behind the boys’ deaths? Or was there an even more sinister conspiracy, perhaps involving Henry Tudor’s wily mother, Margaret Beaufort?

Readers of my book The Hollow Crown (2014) will know where I stand on this, and you can find out more by watching the third episode of Channel 5’s Britain’s Bloody Crown. But I do not pretend that the case is closed. For many Ricardians, the charge of murdering the princes in the Tower is a heinous and unjust accusation levelled at a grievously misunderstood monarch… Where do you stand?

1) Was Perkin Warbeck really Richard IV? An odd young man with an even odder name, Perkin Warbeck is usually described as either a ‘pretender’ or an ‘imposter’. Who was he really?

We usually think of the Wars of the Roses as having ended in 1485 at the battle of Bosworth. In fact, the threat of a revived dynastic war to put a Yorkist king back on the English throne haunted England deep into the Tudor years – well into the 1520s, in fact.

One of the most dangerous times was the 1490s, when the threat of Yorkist plots sponsored from the continent seriously unsettled the fragile Tudor regime. For several years the figurehead for these plots was a young man who claimed to be Richard, duke of York – the younger of the princes in the Tower. If he were crowned, he would have taken the throne as King Richard IV.

Perkin Warbeck, c1495. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

It is easy now to scoff at all this. But at the time, this supposed Richard IV had serious support from rulers in Ireland, France, the Netherlands, Scotland and the Holy Roman Empire, and he attempted several sea invasions of England.

Events came to a head in 1497 when the pseudo-Richard finally succeeded in landing in England and joined up with rebels in the west country. He was captured and brought before Henry VII, where he confessed that he was not, in fact, Richard duke of York, but a French-Flemish merchant’s son, a troublemaker and a puppet for enemies of the Tudor regime.

At first Henry VII was merciful, keeping Warbeck at court and parading him in public to assure people that he was not the real Richard duke of York. But this peaceful situation did not last long. In 1498 Warbeck escaped. He was recaptured and placed in the Tower of London. But while there he was caught up in further plotting against the crown, this time in league with another Yorkist claimant, Edward earl of Warwick.

Again the plotting was foiled and in 1499 Warbeck was forced once more to confess his imposture, and was hanged at Tyburn.

Yet doubt remains. Was Warbeck a pretender? Or were his confessions made under duress? The plots against Henry VII have more than a whiff of a set-up about them: could it be that really was the young Richard duke of York, entangled in a nightmare of Henry VII’s concoction and forced to deny his own birthright?

Most historians would say not. But the possibility remains tantalizing enough to consider…

The Young Princes in the Tower, 1831, by Paul de la Roche (1910). (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

5) What was really wrong with King Henry VI? Henry VI (1422–60 and 1470–71) was comfortably the most incompetent king of the whole Plantagenet line, and his benign but ultimately disastrous rule began the series of conflicts that we now call the Wars of the Roses.

The crisis broke in 1453 when Henry appears to have suffered a near-complete mental collapse. He stopped responding to other people; he didn’t recognise his own wife or newborn son; and for several months he was completely helpless and utterly withdrawn from the world. One contemporary said the king was “smitten with a frenzy”.

The obvious comparison was with Henry’s grandfather Charles VI of France, who had suffered similarly long bouts of madness in which he attacked his courtiers, smeared himself in his own waste and screamed that he felt thousands of sharp needles piercing his flesh.

So was Henry’s illness hereditary? And how would we diagnose it today? Catatonia? Schizophrenia? Severe depression? Medical diagnoses across the centuries are fraught with difficulties, and it is quite possible that we will never be able to say for sure. What we do know is that Henry’s debilitating illness had a correspondingly dreadful effect on both the man and his kingdom, as his subjects fought at first to save the realm, and then to steal control of it for themselves.

4) Were the Tudors really Tudors? The great survivors of the Wars of the Roses were a strange little half-Welsh, half-French family who took the surname Tidyr, or Tudur, or Tudor. Famously, it was Henry Tudor who emerged victorious from the battle of Bosworth in 1485 and, as Henry VII of England, went on to establish the most famous royal dynasty of them all.

But the origins of this remarkable family are surprisingly foggy. Their first connection to the English crown came through Henry VII’s grandmother, Catherine de Valois, widow of Henry V and mother of Henry VI. As dowager queen Catherine had caused quite a stir by secretly marrying her lowly servant, Owen Tudor. Plenty of romantic rumours have swirled around that union, but whatever the case, during the early 1430s Catherine gave birth to several children who took the Tudor name, most notably Henry VII’s father, Edmund Tudor, and another boy named Jasper Tudor.

But were they really Tudors? Intriguingly, shortly before Catherine became involved with Owen, there was a widespread suggestion that she was having an affair with Edmund Beaufort, the future duke of Somerset, who would be killed at the battle of St Albans in 1455. This rumour was taken so seriously that parliament took up the matter and issued a special statute restricting the right of queens of England to remarry.

Edmund Beaufort, c1450. Engraving taken from portrait painted by Hans Holbein the Younger. (Photo by Kean Collection/Getty Images)

It has been speculated that Catherine’s marriage to the lowly Owen Tudor was contracted to cover up her politically dangerous relationship with Edmund Beaufort. In that case, is it possible that Edmund Tudor was not a Tudor at all, but was actually given the forename of his real father?

The great 15th-century expert Gerald Harriss made precisely this suggestion in a fine footnote written in 1988:

“By its very nature the evidence for Edmund ‘Tudor's’ parentage is less than conclusive, but such facts as can be assembled permit the agreeable possibility that Edmund ‘Tudor’ and Margaret Beaufort [ie Edmund Tudor’s wife and Henry VII’s mother] were first cousins and that the royal house of ‘Tudor’ sprang in fact from Beauforts on both sides.”

Wouldn’t that be something?

3) Who was Edward IV’s real wife?

The history books usually state that Edward IV’s wife was Elizabeth Woodville (or ‘Wydeville’). That in itself is a delicious fact: when Edward married Elizabeth in 1464 she was of lowly rank, a widow with two children from her previous marriage and one of the king’s subjects, rather than a foreign princess. What’s more, Edward’s choice of queen upset his closest political ally, the earl of Warwick; caused diplomatic trouble with more than one other country; and annoyed a significant number of other English noble families.

But nothing caused quite so much trouble as the suggestion that Edward IV had in fact married someone else. Following the king’s death in 1483, his brother Richard duke of Gloucester claimed that, before the Woodville marriage took place, Edward IV had promised to marry Lady Eleanor Boteler (née Talbot), a daughter of the famous soldier John Talbot, earl of Shrewsbury.

In 1483 Richard argued that since Edward had once promised to marry Lady Eleanor, he had not subsequently been legally entitled to marry Elizabeth Woodville. This in turn made their union invalid, and their children bastards.

Elizabeth Woodville, 1463. (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

This claim was the basis of Richard’s usurpation of the crown. He made it known that Edward IV’s young son and successor, Edward V, was illegitimate, and instead claimed the throne for himself, as Richard III.

But was it true? Conveniently, in 1483 the case could not be properly tested, since Lady Eleanor had died 15 years previously. But today, those seeking to rehabilitate Richard III’s reputation frequently rely on the ‘pre-contract’ argument to defend his actions.

2) Did Richard III really kill the princes in the Tower?

Perhaps the greatest mystery of them all, and certainly the question most likely to start a fistfight among any given group of medievalists.

For centuries Richard III’s name has been blackened thanks to his usurpation of the throne in 1483 and the subsequent disappearance of his nephews, Edward V and Richard duke of York – better known as ‘the princes in the Tower’.

Did the boys really die? And if so, who was to blame? Did Richard have them murdered? Or did they die of natural causes? Were there other agents at work? And if so, who? Could it be, as one contemporary source suggested, that Richard’s sometime ally, the oily and feckless Henry Stafford, duke of Buckingham, was the prime mover behind the boys’ deaths? Or was there an even more sinister conspiracy, perhaps involving Henry Tudor’s wily mother, Margaret Beaufort?

Readers of my book The Hollow Crown (2014) will know where I stand on this, and you can find out more by watching the third episode of Channel 5’s Britain’s Bloody Crown. But I do not pretend that the case is closed. For many Ricardians, the charge of murdering the princes in the Tower is a heinous and unjust accusation levelled at a grievously misunderstood monarch… Where do you stand?

1) Was Perkin Warbeck really Richard IV? An odd young man with an even odder name, Perkin Warbeck is usually described as either a ‘pretender’ or an ‘imposter’. Who was he really?

We usually think of the Wars of the Roses as having ended in 1485 at the battle of Bosworth. In fact, the threat of a revived dynastic war to put a Yorkist king back on the English throne haunted England deep into the Tudor years – well into the 1520s, in fact.

One of the most dangerous times was the 1490s, when the threat of Yorkist plots sponsored from the continent seriously unsettled the fragile Tudor regime. For several years the figurehead for these plots was a young man who claimed to be Richard, duke of York – the younger of the princes in the Tower. If he were crowned, he would have taken the throne as King Richard IV.

Perkin Warbeck, c1495. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

It is easy now to scoff at all this. But at the time, this supposed Richard IV had serious support from rulers in Ireland, France, the Netherlands, Scotland and the Holy Roman Empire, and he attempted several sea invasions of England.

Events came to a head in 1497 when the pseudo-Richard finally succeeded in landing in England and joined up with rebels in the west country. He was captured and brought before Henry VII, where he confessed that he was not, in fact, Richard duke of York, but a French-Flemish merchant’s son, a troublemaker and a puppet for enemies of the Tudor regime.

At first Henry VII was merciful, keeping Warbeck at court and parading him in public to assure people that he was not the real Richard duke of York. But this peaceful situation did not last long. In 1498 Warbeck escaped. He was recaptured and placed in the Tower of London. But while there he was caught up in further plotting against the crown, this time in league with another Yorkist claimant, Edward earl of Warwick.

Again the plotting was foiled and in 1499 Warbeck was forced once more to confess his imposture, and was hanged at Tyburn.

Yet doubt remains. Was Warbeck a pretender? Or were his confessions made under duress? The plots against Henry VII have more than a whiff of a set-up about them: could it be that really was the young Richard duke of York, entangled in a nightmare of Henry VII’s concoction and forced to deny his own birthright?

Most historians would say not. But the possibility remains tantalizing enough to consider…

Published on December 08, 2016 02:00

December 7, 2016

December 7 - Remembering Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941. The attack led to the United States' entry into World War II.

Published on December 07, 2016 03:30

New Information Comes to Light on a Unique Mycenaean Tholos Tomb

Ancient Origins

Preliminary results have been provided on a Mycenaean tholos tomb discovered in 2014 on the slope of the Amblianos hill near Amphissa on the Greek mainland. The tomb is considered a special find in West Locris and is one of the few funeral monuments of this type in Central Greece.

Archaeology News Network reports the tomb has a long dromos (road) of about 30 ft. (9 meters) in length, leading to a circular chamber, 19.5 ft. (5.90 meters) in diameter, with a plastered floor. Even though the slab-like stones which were the superstructure of the tholos have crumbled, the walls of the chamber are in a pretty good condition. Archaeologists believe the tomb was used for more than two centuries, from the 13th to the 11th century BC.

The Finds Inside the Tomb The site Archaeology Newsroom says that a variety of osteological material was found inside the funeral chamber, especially in the center and around the walls. The finds also include several pottery vessels, Phi and Psi type figurines, weapons, a large quantity of jewelry, beads of semi-precious stones, and seals portraying animal scenes.

Example of "Phi" figurines (because they look like the Greek letter Φ) from Mycenae. (13th century BC) (Public Domain)

The newly discovered group of seals is especially interesting. They mostly portray simplified animals sitting next to branches or trees and date back to the last periods of Mycenaean seal-making. Among the figurines, another intriguing group of finds includes the image of a bull leaper, like one discovered at Methana.

Clay finds include miniature pieces of furniture such as a three-legged open chair and pieces of two other creations which could be offering tables or even funeral biers. The list of grave goods is completed with bronze vessels and objects made of gold, faience, and glass paste.

Mycenaean figurines from Agios Konstantinos, Methana. (14-13th century BC) Archaeological Museum of Piraeus, Greece. (Schuppi/CC BY SA 3.0) It is clear that the relatives of the people who were buried in the tomb cleaned out the burial chamber pretty often by removing earlier offerings to the dead, especially pottery, into the dromos or in an apothetes sealed with a low wall at the end of the dromos.

This led into the slow rise of the floor level of the dromos and the erection of a small staircase before the chamber’s entrance to make access easier. The archaeologists mostly found drinking vessels and vessels for mixing liquids in the apothetes. Some of the vessels impressed the archaeologists with their beautiful decoration.

The Importance of the Discovery

The study and presentation of this rare burial site is very significant for understanding the Mycenaean period in north Boeotia and Phocis - ancient Greek locations for which little is currently known. According to Archaeofeed, both the quality and the quantity of the pottery and the other discoveries from this tomb are important additions to the small, known group of examples from the neighboring sites of Kirrha, Krisa and Delphi, enlightening researchers about a number of matters regarding the local production of pottery and small artifacts.

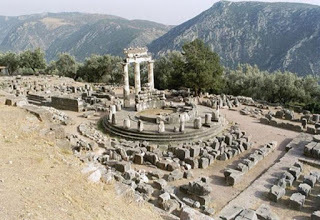

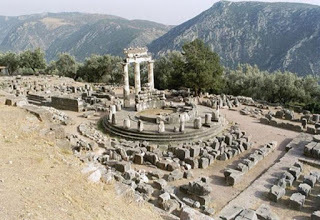

The tholos at the Delphi archaeological site, Phocis, Greece. (Arian Zwegers/CC BY 2.0)

Furthermore, the tholos tomb reveals significant information about the topography of the area and the commercial and cultural elements of the local community situated in the periphery of the Mycenaean world. This makes historians wonder even more about the use of this type of monument by local elites in the past.

The study and the publication of this tomb is the result of work by a multi-disciplinary group of scholars, coordinated by Dr. Elena Kountouri, head of the Directorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities of the Greek Ministry of Culture. Dr. Kountouri will present the information on the tholos tomb found at the site of Amblianos in Amphissa as part of the Mycenaean Seminar series in the University of Athens on November 24, 2016.

Top Image: The tholos tomb discovered in Amblianos, Greece. Source: Archaiologia

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Preliminary results have been provided on a Mycenaean tholos tomb discovered in 2014 on the slope of the Amblianos hill near Amphissa on the Greek mainland. The tomb is considered a special find in West Locris and is one of the few funeral monuments of this type in Central Greece.

Archaeology News Network reports the tomb has a long dromos (road) of about 30 ft. (9 meters) in length, leading to a circular chamber, 19.5 ft. (5.90 meters) in diameter, with a plastered floor. Even though the slab-like stones which were the superstructure of the tholos have crumbled, the walls of the chamber are in a pretty good condition. Archaeologists believe the tomb was used for more than two centuries, from the 13th to the 11th century BC.

The Finds Inside the Tomb The site Archaeology Newsroom says that a variety of osteological material was found inside the funeral chamber, especially in the center and around the walls. The finds also include several pottery vessels, Phi and Psi type figurines, weapons, a large quantity of jewelry, beads of semi-precious stones, and seals portraying animal scenes.

Example of "Phi" figurines (because they look like the Greek letter Φ) from Mycenae. (13th century BC) (Public Domain)

The newly discovered group of seals is especially interesting. They mostly portray simplified animals sitting next to branches or trees and date back to the last periods of Mycenaean seal-making. Among the figurines, another intriguing group of finds includes the image of a bull leaper, like one discovered at Methana.

Clay finds include miniature pieces of furniture such as a three-legged open chair and pieces of two other creations which could be offering tables or even funeral biers. The list of grave goods is completed with bronze vessels and objects made of gold, faience, and glass paste.

Mycenaean figurines from Agios Konstantinos, Methana. (14-13th century BC) Archaeological Museum of Piraeus, Greece. (Schuppi/CC BY SA 3.0) It is clear that the relatives of the people who were buried in the tomb cleaned out the burial chamber pretty often by removing earlier offerings to the dead, especially pottery, into the dromos or in an apothetes sealed with a low wall at the end of the dromos.

This led into the slow rise of the floor level of the dromos and the erection of a small staircase before the chamber’s entrance to make access easier. The archaeologists mostly found drinking vessels and vessels for mixing liquids in the apothetes. Some of the vessels impressed the archaeologists with their beautiful decoration.

The Importance of the Discovery

The study and presentation of this rare burial site is very significant for understanding the Mycenaean period in north Boeotia and Phocis - ancient Greek locations for which little is currently known. According to Archaeofeed, both the quality and the quantity of the pottery and the other discoveries from this tomb are important additions to the small, known group of examples from the neighboring sites of Kirrha, Krisa and Delphi, enlightening researchers about a number of matters regarding the local production of pottery and small artifacts.

The tholos at the Delphi archaeological site, Phocis, Greece. (Arian Zwegers/CC BY 2.0)

Furthermore, the tholos tomb reveals significant information about the topography of the area and the commercial and cultural elements of the local community situated in the periphery of the Mycenaean world. This makes historians wonder even more about the use of this type of monument by local elites in the past.

The study and the publication of this tomb is the result of work by a multi-disciplinary group of scholars, coordinated by Dr. Elena Kountouri, head of the Directorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities of the Greek Ministry of Culture. Dr. Kountouri will present the information on the tholos tomb found at the site of Amblianos in Amphissa as part of the Mycenaean Seminar series in the University of Athens on November 24, 2016.

Top Image: The tholos tomb discovered in Amblianos, Greece. Source: Archaiologia

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on December 07, 2016 02:00

December 6, 2016

Reconstructed Circus Maximus Provides Tourists with a New Opportunity to Experience Ancient Rome

Ancient Origins

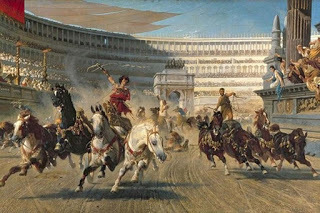

More than six years of excavations and restoration work has given Rome a new tourist attraction in the form of the ancient Circus Maximus. The archaeological ruins were nothing more than an enormous muddy field between the ancient Palatine and Aventine Hills for many centuries. But now they are proudly shown off to visitors as the spruced-up ruins of one of the ancient world's biggest public entertainment venues.

Starting on November 17, history lovers can visit the arched walkways where senators and plebeians once gathered. Everyone who visits the site will be able to see ancient latrines and chunks of what was once a triumphal arch honoring a Roman emperor. Visitors will also learn about a champion horse known as Numitor, whose image is the only documentation of a horse involved in ancient entertainment according to archaeologist Marialetizia Buonfiglio.

The Circus Maximus archaeological site after its restoration and opening to the public. ( The Australian ) Many Significant Treasures The archaeologists who have taken part in the excavations were pleased to discover a lot of ancient artifacts, including more than a thousand bronze coins going back to the 3rd century AD, pieces of gold bracelets and necklaces, and the bottom of a glass goblet with gold tracery portraying the horse Numitor with a palm branch – the symbol of victory – clamped between its teeth. Claudio Parisi Presicce, one of Rome’s most important cultural heritage officials, mentioned that Numitor will be the logo for the Circus Maximus from now on.

Archaeologists have also unearthed the remains of a large triumphal arch that was dedicated to the Emperor Titus in honor of his successful invasion and conquest of Jerusalem in 70 AD, during the first Roman-Jewish war. Huge fragments of fluted pillars and pediments were discovered - all made from white marble mined in Carrara, Tuscany. Impressed with all the findings, Presicce told the Telegraph , “This is one of the most important monuments of ancient Rome. It represents 2,800 years of history, from the age of Romulus to the present day.”

Reconstructions of the Circus Maximus The excavation has helped archaeologists and historians comprehend the many reconstructions that the Circus Maximus underwent over the years, including one after its wooden timbers fed the fire in Rome during Nero’s reign in 64 AD. Guests can climb inside a restored medieval tower for a breath-taking view down the 2,000 ft. (600 meter) long field, witnessing with their own eyes the impressive cupola of the “Eternal City’s” main synagogue. Presicce feels that the 2,800-year-old Circus Maximus was probably the most popular of all venues in Rome when it came to significant entertainment events, and is excited that people can now see all this with their own eyes. As Presicce told Reuters , “Now we can imagine bustling activity around the semicircle which we have restored and made accessible to the people, with crowds gathering around these structures."

Reuters reports that the Circus Maximus archaeological site will be open to the public daily until December 11. After that, opening hours will be reserved for weekends, though guests can call City Hall (+39-06-0608) to make an appointment if they wish to visit the site during the week.

A section of the Circus Maximus after reconstruction. ( HRT Magazin )

Top Image: Chariot racing in ancient Rome ( University of Wisconsin )

By Theodoros II

More than six years of excavations and restoration work has given Rome a new tourist attraction in the form of the ancient Circus Maximus. The archaeological ruins were nothing more than an enormous muddy field between the ancient Palatine and Aventine Hills for many centuries. But now they are proudly shown off to visitors as the spruced-up ruins of one of the ancient world's biggest public entertainment venues.

Starting on November 17, history lovers can visit the arched walkways where senators and plebeians once gathered. Everyone who visits the site will be able to see ancient latrines and chunks of what was once a triumphal arch honoring a Roman emperor. Visitors will also learn about a champion horse known as Numitor, whose image is the only documentation of a horse involved in ancient entertainment according to archaeologist Marialetizia Buonfiglio.

The Circus Maximus archaeological site after its restoration and opening to the public. ( The Australian ) Many Significant Treasures The archaeologists who have taken part in the excavations were pleased to discover a lot of ancient artifacts, including more than a thousand bronze coins going back to the 3rd century AD, pieces of gold bracelets and necklaces, and the bottom of a glass goblet with gold tracery portraying the horse Numitor with a palm branch – the symbol of victory – clamped between its teeth. Claudio Parisi Presicce, one of Rome’s most important cultural heritage officials, mentioned that Numitor will be the logo for the Circus Maximus from now on.

Archaeologists have also unearthed the remains of a large triumphal arch that was dedicated to the Emperor Titus in honor of his successful invasion and conquest of Jerusalem in 70 AD, during the first Roman-Jewish war. Huge fragments of fluted pillars and pediments were discovered - all made from white marble mined in Carrara, Tuscany. Impressed with all the findings, Presicce told the Telegraph , “This is one of the most important monuments of ancient Rome. It represents 2,800 years of history, from the age of Romulus to the present day.”

Reconstructions of the Circus Maximus The excavation has helped archaeologists and historians comprehend the many reconstructions that the Circus Maximus underwent over the years, including one after its wooden timbers fed the fire in Rome during Nero’s reign in 64 AD. Guests can climb inside a restored medieval tower for a breath-taking view down the 2,000 ft. (600 meter) long field, witnessing with their own eyes the impressive cupola of the “Eternal City’s” main synagogue. Presicce feels that the 2,800-year-old Circus Maximus was probably the most popular of all venues in Rome when it came to significant entertainment events, and is excited that people can now see all this with their own eyes. As Presicce told Reuters , “Now we can imagine bustling activity around the semicircle which we have restored and made accessible to the people, with crowds gathering around these structures."

Reuters reports that the Circus Maximus archaeological site will be open to the public daily until December 11. After that, opening hours will be reserved for weekends, though guests can call City Hall (+39-06-0608) to make an appointment if they wish to visit the site during the week.

A section of the Circus Maximus after reconstruction. ( HRT Magazin )

Top Image: Chariot racing in ancient Rome ( University of Wisconsin )

By Theodoros II

Published on December 06, 2016 02:00

December 5, 2016

Archaeologists Find Medieval Dentures Made from the Teeth of Dead People

Ancient Origins

A team of scientists from the University of Pisa in Italy made an unusual discovery in an ancient family tomb in Lucca – a set of dentures that was constructed using teeth from several deceased people. The prosthesis dates back to between the 14 th and early 17 th century, but if confirmed to be from the 14 th century, it will be one of the oldest known sets in Europe. The Local reports that the set of false teeth was found at the chapel of San Francesco in a tomb belonging to the Guinigis, a powerful family of bankers and traders who governed the city of Lucca from 1392 until 1429. Members of the Franciscan order were present at the site since 1228, but the current church dates from the 14th-century.

The convent of San Francesco in Lucca, Italy ( CC by 2.5 / Sailko ) The researchers wrote in a paper published in the journal of Clinical Implant Dentistry and Related Research that the dentures are composed of five teeth, canines and incisors, which came from different individuals. They are linked together by a strip of metal composed mostly of gold, along with silver and copper, the latter metal causing the green staining on the teeth. Two small golden pins were inserted into each tooth crossing the root and fixing the teeth to the gold strip. The prosthesis would have stuck to the wearer’s lower gum. An analysis of the calculus on the dentures indicates that the dentures had been worn for a long period.

The set of dentures discovered in Italy. Credit: University of Pisa Dentistry, including drilling and filling, has been practiced for at least 9,000 years, while the first attempt at connecting human teeth together to be used as false teeth can be traced back to the Egyptians as far back as 3,500 years. In Italy, the Etruscans and Romans began making sets of false teeth around the 7 th century BC. There are three known instances of dental bridges found in Egypt in which one or more lost teeth were reattached by means of a gold or silver wire to the surrounding teeth. In some cases, a bridge was made using donor teeth. However, it’s a bit unclear whether these works were performed during the life of the patient or after death – to tidy them up before their burial.

Incredible dental work found on an ancient mummy. The two centre teeth are donor teeth. In the 1400s, dentures seemed to take more of the modernised shape that we see today. These dentures were still made from carved animal bone or ivory, but some were now made from human teeth. Grave robbers often used to steel the teeth from recently deceased people and sell them to dentists, and the poor used to make money by having their teeth extracted and selling them. The finished denture would not be very aesthetically pleasing or very stable in the mouth, and was often tied to the patients remaining teeth. Another problem that occurred with these dentures is that they tended not to last long and began to rot over time. The first porcelain dentures did not arrive until the 18th century. Writing in their paper on the finding, the researchers explain: “'This dental prosthesis provides a unique finding of technologically advanced dentistry in this period… during the Early Modern Age, some authors described gold band technology for the replacement of missing teeth. Nevertheless, no direct evidences of these devices have been brought to light up so far.” One member of the team, Dr Simona Minozzi, told The Local: "The dentures found in the tomb are the first example of dentures from this historical period, and as such are a valuable addition to the history of dentistry."

Top image: The set of dentures discovered in Italy. Credit: University of Pisa

By April Holloway

Published on December 05, 2016 03:00

December 4, 2016

The glorious Caesars

History Extra

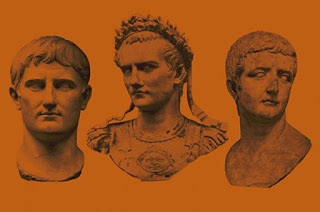

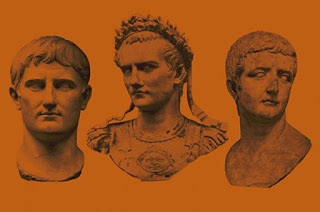

Augustus, Caligula and Tiberius, depicted (left to right) in contemporary busts. For all their despotism, Romans thanked their first three emperors for delivering them from the curse of civil war. © Getty/AKG Images

Almost 2,000 years after his death, Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus remains the archetype of a monstrous leader. Caligula, as he is better known, is one of the few characters from ancient history to be as familiar to pornographers as to classicists. The scandalous details of his reign have always provoked prurient fascination. “But enough of the emperor; now to the monster.” So wrote Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, an archivist in the imperial palace who doubled in his spare time as a biographer of the Caesars, and whose life of Caligula is the oldest extant account that we possess. Written almost a century after the emperor’s death, it catalogues a quite sensational array of depravities and crimes. He slept with his sisters! He dressed up as the goddess Venus! He planned to award his horse the highest magistracy in Rome! So appalling were his stunts that they seemed to shade into lunacy. Suetonius certainly had no doubt about this when explaining Caligula’s behaviour: “He was ill in both body and mind.” But if Caligula was sick then so, too, was his city. The powers of life and death wielded by an emperor would have been abhorrent to an earlier generation. Almost a century before Caligula came to power, his great-great-great-great-uncle had been the first of his dynasty to establish an autocracy in Rome. The exploits of Gaius Julius Caesar were as spectacular as any in his city’s history: the permanent annexation of Gaul, as the Romans called what today is France, and invasions of Britain and Germany. He achieved his feats, though, as a citizen of a republic – one in which it was taken for granted by most that death was the only conceivable alternative to liberty. When Julius Caesar, trampling this presumption, laid claim to a primacy over his fellow citizens, it resulted first in civil war and then, after he had crushed his domestic foes as he had previously crushed the Gauls, in his assassination. Only after two more murderous bouts of slaughtering one another were the Roman people finally inured to their servitude. Submission to the rule of a single man had redeemed their city and its empire from self-destruction – but the cure itself was a kind of disease. Their new master called himself Augustus: the ‘Divinely Favoured One’. The great-nephew of Julius Caesar, he had waded through blood to secure the command of Rome and her empire – and then, once his rivals had been dispatched, had coolly posed as a prince of peace. As cunning as he was ruthless, as patient as he was decisive, Augustus managed to maintain his supremacy for decades, and then to die in his bed. Key to this achievement was his ability to rule with, rather than against the grain of, Roman tradition. By pretending that he was not an autocrat, he licensed his fellow citizens to pretend that they were still free. A veil of shimmering and seductive subtlety was draped over the brute contours of his dominance.

A detail from the Ara Pacis, an altar dedicated to the goddess of peace. It was built under Augustus who, having butchered his way to power, recast himself as a prince of peace. © AKG Images

Over time, though, this veil became increasingly threadbare. On Augustus’s death in AD 14, the powers that he had accumulated over the course of his long and mendacious career stood revealed, not as temporary expediencies but rather as a package to be handed down to an heir. His choice of successor was a man raised since childhood in his own household, an aristocrat by the name of Tiberius. The many qualities of the new Caesar, which ranged from exemplary aristocratic pedigree to a track record as Rome’s finest general, had counted for less than his status as Augustus’s adopted son – and everyone knew it. A diseased age Tiberius, a man who all his life had been wedded to the virtues of the vanished republic, made an unhappy monarch; but Caligula, who succeeded Tiberius after a reign of 23 years, was unembarrassed. That he ruled the Roman world by virtue neither of age nor of experience but as the great-grandson of Augustus bothered him not the slightest. “Nature produced him, in my opinion, to demonstrate just how far unlimited vice can go when combined with unlimited power.” Such was the obituary delivered on Caligula by Seneca, a philosopher who had known him well. The judgment, though, was not just on Caligula, but also on Seneca’s own peers, who had cringed and grovelled before the emperor while he was still alive, and on the Roman people as a whole. The age was a rotten one: diseased, debased, degraded.

A statue from first-century Pompeii showing Caligula on horseback. The emperor’s favourite horse was called Incitatus, and it was said that Caligula planned to make it a consul. © Alamy

Or so many believed. Not everyone agreed. The regime established by Augustus would never have endured had it failed to offer what the Roman people had come so desperately to crave after decades of civil war: peace and order. The vast agglomeration of provinces ruled from Rome, stretching from the North Sea to the Sahara and from the Atlantic to the Fertile Crescent, reaped the benefits as well. Three centuries on, when the nativity of the most celebrated man born in Augustus’s reign – Jesus – stood in infinitely clearer focus than it had done at the time, a bishop named Eusebius could see in the emperor’s achievements the very guiding hand of God. “It was not just as a consequence of human action,” he declared, “that the greater part of the world should have come under Roman rule at the precise moment Jesus was born. The coincidence that saw our Saviour begin his mission against such a backdrop was undeniably arranged by divine agency. After all, had the world still been at war, and not united under a single form of government, then how much more difficult would it have been for the disciples to undertake their travels?” The price of peace Eusebius could see, with the perspective provided by distance, just how startling was the feat of globalisation brought to fulfilment under Augustus and his successors. Though the methods deployed to uphold it were brutal, the sheer immensity of the regions pacified by Roman arms was unprecedented. “To accept a gift,” went an ancient saying, “is to sell your liberty.” Rome held her conquests in fee, but the peace that she bestowed upon them in exchange was not necessarily to be sniffed at. Whether in the suburbs of the capital itself – booming under the Caesars to become the largest city the world had ever seen – or across the span of the Mediterranean, united now for the first time under a single power, or in the furthermost corners of an empire, the pax Romana brought benefits to millions.

A fourth-century relief shows Jesus with three apostles. One bishop of that era claimed that the Augustinian peace hastened the spread of Christianity. © Alamy

Provincials might well be grateful. “He cleared the sea of pirates, and filled it with merchant shipping.” So enthused a Jew from the Egyptian metropolis of Alexandria, writing in praise of Augustus. “He gave freedom to every city, brought order where there had been chaos, and civilised savage peoples.” Similar hymns of praise could be – and were – addressed to Tiberius and Caligula. The depravities for which these men would become notorious rarely had much impact on the wider world. In the provinces it mattered little who ruled as emperor – so long as the centre held.

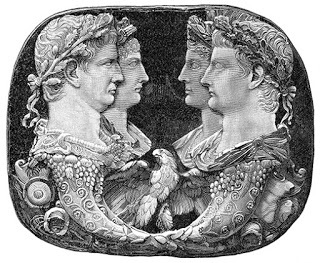

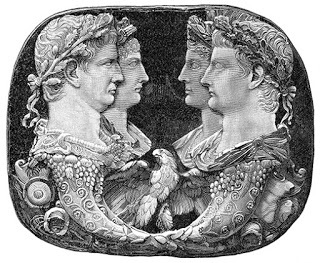

This etching shows the emperors Claudius (left) and Tiberius, with their wives Agrippina and Livia, respectively. © Alamy

Yet even in the empire’s farthest reaches, Caesar was a constant presence. How could he not be? “In the whole wide world, there is not a single thing that escapes him.” An exaggeration, of course – yet a due reflection of the fear and awe that an emperor could hardly help but inspire in his subjects. He alone had command of Rome’s monopoly of violence: the legions and the menacing apparatus of provincial government that ensured that taxes were paid, rebels slaughtered and malefactors thrown to beasts or nailed up on crosses. An emperor did not constantly need to be showing his hand for dread of his arbitrary power to be universal across the world. Small wonder that the face of Caesar should have become, for millions of his subjects, the face of Rome. Rare was the town that did not boast some image of him: a statue, a portrait bust, a frieze. Even in the most provincial backwater, to handle money was to be familiar with Caesar’s profile. Within Augustus’s own lifetime, no living citizen had ever appeared on a Roman coin – but no sooner had he seized control of the world than his face was being minted everywhere, stamped on gold, silver and bronze. “Whose likeness and inscription is this?” Even an itinerant street-preacher in the wilds of Galilee, holding up a coin and demanding to know whose face it portrayed, could be confident of the answer: “Caesar’s.”

A first-century BC coin shows Augustus wearing a laurel wreath – symbol of military victory. © Getty

No surprise, then, that the character of an emperor – his achievements, his relationships and his foibles – should have been topics of obsessive fascination to his subjects. “Your destiny it is to live as in a theatre where your audience is the entire world.” This was the warning attributed by one Roman historian to Maecenas, a close confidant of Augustus. Whether or not he really said it, the sentiment was true to his master’s theatricality. Augustus, lying on his deathbed, was reported by Suetonius to have asked his friends whether he had played his part well in the comedy of life; assured that he had, he demanded their applause as he headed for the exit.

A good emperor had no choice but to be a good actor – as, too, did everyone else in the drama’s cast. Caesar, after all, was never alone on the stage. His potential successors were public figures by virtue of their relationship to him. Even the wife, the niece or the granddaughter of an emperor might have her role to play. Get it wrong and she was liable to pay a terrible price, but get it right and her face might appear on coins alongside Caesar’s own.

No household in history had ever before been so squarely in the public eye as that of Augustus. The fashions and hairstyles of its most prominent members, reproduced in exquisite detail by sculptors across the empire, set trends from Syria to Spain. Their achievements were celebrated with spectacularly showy monuments, their scandals repeated with relish from seaport to seaport. Propaganda and gossip, each feeding off the other, gave the dynasty of Augustus a celebrity that became, for the first time, continent-spanning. Time has barely dimmed it. Two millennia on, the west’s prime examples of tyranny continue to instruct and appal.

The exhaustion of cruelty

“Nothing could be fainter than those torches which allow us not to pierce the darkness but to glimpse it.” So wrote Seneca, shortly before his death in AD 65. The context of his observation was a shortcut that he had recently taken while travelling along the Bay of Naples, down a gloomy and dust-choked tunnel. “What a prison it was, and how long. Nothing could compare with it.” As a man who had spent many years observing the imperial court, Seneca knew all about darkness. He certainly had no illusions about the nature of the regime established by Augustus. Even the peace that it had brought the world, he declared, had ultimately been founded upon nothing more noble than “the exhaustion of cruelty”. Despotism had been implicit in the new order from its beginning. Yet what he detested, Seneca also adored. Contempt for power did not inhibit him from revelling in it. The darkness of Rome was lit by gold. Looking back to Augustus and his heirs from 2,000 years on, we too can recognise – in their mingling of tyranny and achievement, sadism and glamour, power-lust and celebrity – an aureate quality such as no dynasty since has ever quite managed to match. “Caesar is the state.” How this came to be so is a story no less compelling, no less remarkable and no less salutary than it has ever been these past 2,000 years.

The first five Roman emperors

The first emperor - Augustus (63 BC–AD 14, emperor from 27 BC) Born Gaius Octavius, his adoption by his great-uncle Julius Caesar left him with a commanding name and fortune. By his mid-thirties he enjoyed an unprecedented dominance over the Roman world. In 27 BC he took the title Augustus: ‘Divinely Favoured One’. By the time of his death, he had established an autocracy secure enough to survive as long as the empire itself.

The iconic general: Tiberius (42 BC–AD 37, emperor from AD 14) His mother’s marriage to Augustus won Tiberius a place at the heart of the new imperial dynasty. Though an accomplished general, he was unpopular with the masses, and his respect for republican traditions ensured he was never entirely comfortable as emperor. His retirement to Capri in AD 27 fuelled salacious rumours, but by maintaining peace he won respect in the provinces.

The witty sadist: Caligula (AD 12–41, emperor from AD 37) Properly called Gaius, as a young boy he was nicknamed ‘Caligula’ (‘little boots’) by soldiers serving under his father. “I am rearing a viper,” declared Tiberius – and so it proved. On becoming emperor, Caligula’s twin tastes for theatricality and hurting people fuelled attacks on the authority of the Senate. Even so, when he was assassinated by his own guards in AD 41 his death was widely mourned.

The able ruler: Claudius (10 BC–AD 54, emperor from AD 41) The nephew of Tiberius was prone to twitching and stammering, which hindered his political progress. He became Caesar when his nephew Caligula was murdered. Though widely despised as being under the thumb of women and freedmen, he proved an effective emperor, invading Britain and commissioning a new port for Rome. His death was believed to have been caused by his wife (and niece), Agrippina.

The showman: Nero (AD 37–68, emperor from AD 54) Known initially as Domitius, the son of Agrippina was adopted by Claudius; he later had his mother and wife murdered. He refined Caligula’s policy of appealing over the heads of the senatorial elite to the mass of the people; the more murderous his regime became, the more his showmanship flourished. Faced with rebellion, he committed suicide in AD 68 – marking the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Tom Holland is a presenter on BBC Radio 4’s Making History.

Augustus, Caligula and Tiberius, depicted (left to right) in contemporary busts. For all their despotism, Romans thanked their first three emperors for delivering them from the curse of civil war. © Getty/AKG Images

Almost 2,000 years after his death, Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus remains the archetype of a monstrous leader. Caligula, as he is better known, is one of the few characters from ancient history to be as familiar to pornographers as to classicists. The scandalous details of his reign have always provoked prurient fascination. “But enough of the emperor; now to the monster.” So wrote Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, an archivist in the imperial palace who doubled in his spare time as a biographer of the Caesars, and whose life of Caligula is the oldest extant account that we possess. Written almost a century after the emperor’s death, it catalogues a quite sensational array of depravities and crimes. He slept with his sisters! He dressed up as the goddess Venus! He planned to award his horse the highest magistracy in Rome! So appalling were his stunts that they seemed to shade into lunacy. Suetonius certainly had no doubt about this when explaining Caligula’s behaviour: “He was ill in both body and mind.” But if Caligula was sick then so, too, was his city. The powers of life and death wielded by an emperor would have been abhorrent to an earlier generation. Almost a century before Caligula came to power, his great-great-great-great-uncle had been the first of his dynasty to establish an autocracy in Rome. The exploits of Gaius Julius Caesar were as spectacular as any in his city’s history: the permanent annexation of Gaul, as the Romans called what today is France, and invasions of Britain and Germany. He achieved his feats, though, as a citizen of a republic – one in which it was taken for granted by most that death was the only conceivable alternative to liberty. When Julius Caesar, trampling this presumption, laid claim to a primacy over his fellow citizens, it resulted first in civil war and then, after he had crushed his domestic foes as he had previously crushed the Gauls, in his assassination. Only after two more murderous bouts of slaughtering one another were the Roman people finally inured to their servitude. Submission to the rule of a single man had redeemed their city and its empire from self-destruction – but the cure itself was a kind of disease. Their new master called himself Augustus: the ‘Divinely Favoured One’. The great-nephew of Julius Caesar, he had waded through blood to secure the command of Rome and her empire – and then, once his rivals had been dispatched, had coolly posed as a prince of peace. As cunning as he was ruthless, as patient as he was decisive, Augustus managed to maintain his supremacy for decades, and then to die in his bed. Key to this achievement was his ability to rule with, rather than against the grain of, Roman tradition. By pretending that he was not an autocrat, he licensed his fellow citizens to pretend that they were still free. A veil of shimmering and seductive subtlety was draped over the brute contours of his dominance.

A detail from the Ara Pacis, an altar dedicated to the goddess of peace. It was built under Augustus who, having butchered his way to power, recast himself as a prince of peace. © AKG Images

Over time, though, this veil became increasingly threadbare. On Augustus’s death in AD 14, the powers that he had accumulated over the course of his long and mendacious career stood revealed, not as temporary expediencies but rather as a package to be handed down to an heir. His choice of successor was a man raised since childhood in his own household, an aristocrat by the name of Tiberius. The many qualities of the new Caesar, which ranged from exemplary aristocratic pedigree to a track record as Rome’s finest general, had counted for less than his status as Augustus’s adopted son – and everyone knew it. A diseased age Tiberius, a man who all his life had been wedded to the virtues of the vanished republic, made an unhappy monarch; but Caligula, who succeeded Tiberius after a reign of 23 years, was unembarrassed. That he ruled the Roman world by virtue neither of age nor of experience but as the great-grandson of Augustus bothered him not the slightest. “Nature produced him, in my opinion, to demonstrate just how far unlimited vice can go when combined with unlimited power.” Such was the obituary delivered on Caligula by Seneca, a philosopher who had known him well. The judgment, though, was not just on Caligula, but also on Seneca’s own peers, who had cringed and grovelled before the emperor while he was still alive, and on the Roman people as a whole. The age was a rotten one: diseased, debased, degraded.

A statue from first-century Pompeii showing Caligula on horseback. The emperor’s favourite horse was called Incitatus, and it was said that Caligula planned to make it a consul. © Alamy

Or so many believed. Not everyone agreed. The regime established by Augustus would never have endured had it failed to offer what the Roman people had come so desperately to crave after decades of civil war: peace and order. The vast agglomeration of provinces ruled from Rome, stretching from the North Sea to the Sahara and from the Atlantic to the Fertile Crescent, reaped the benefits as well. Three centuries on, when the nativity of the most celebrated man born in Augustus’s reign – Jesus – stood in infinitely clearer focus than it had done at the time, a bishop named Eusebius could see in the emperor’s achievements the very guiding hand of God. “It was not just as a consequence of human action,” he declared, “that the greater part of the world should have come under Roman rule at the precise moment Jesus was born. The coincidence that saw our Saviour begin his mission against such a backdrop was undeniably arranged by divine agency. After all, had the world still been at war, and not united under a single form of government, then how much more difficult would it have been for the disciples to undertake their travels?” The price of peace Eusebius could see, with the perspective provided by distance, just how startling was the feat of globalisation brought to fulfilment under Augustus and his successors. Though the methods deployed to uphold it were brutal, the sheer immensity of the regions pacified by Roman arms was unprecedented. “To accept a gift,” went an ancient saying, “is to sell your liberty.” Rome held her conquests in fee, but the peace that she bestowed upon them in exchange was not necessarily to be sniffed at. Whether in the suburbs of the capital itself – booming under the Caesars to become the largest city the world had ever seen – or across the span of the Mediterranean, united now for the first time under a single power, or in the furthermost corners of an empire, the pax Romana brought benefits to millions.

A fourth-century relief shows Jesus with three apostles. One bishop of that era claimed that the Augustinian peace hastened the spread of Christianity. © Alamy

Provincials might well be grateful. “He cleared the sea of pirates, and filled it with merchant shipping.” So enthused a Jew from the Egyptian metropolis of Alexandria, writing in praise of Augustus. “He gave freedom to every city, brought order where there had been chaos, and civilised savage peoples.” Similar hymns of praise could be – and were – addressed to Tiberius and Caligula. The depravities for which these men would become notorious rarely had much impact on the wider world. In the provinces it mattered little who ruled as emperor – so long as the centre held.

This etching shows the emperors Claudius (left) and Tiberius, with their wives Agrippina and Livia, respectively. © Alamy