MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 77

November 5, 2016

Kings and Queens in profile: Jane Seymour

History Extra

Jane Seymour. (Popperfoto/Getty Images)

Historian Elizabeth Norton tells you everything you need to know about Jane Seymour, queen of England from 1536 to 1537 as the third wife of Henry VIII

Born: In around 1508

Died: 24 October 1537

Ruled: from 1536 to 1537

Family: the daughter of Sir John Seymour of Wolfhall in Wiltshire and his wife, Margery Wentworth

Successor: Anne of Cleves, Henry’s fourth wife

Remembered for: being the only wife to provide Henry with a son and male heir

Life: Jane Seymour, Henry VIII’s third wife, was born in around 1508. Her kinsman, the courtier Sir Francis Bryan, secured a place for her in the service of Queen Catherine of Aragon. Jane later transferred into the household of Catherine’s successor, Anne Boleyn.

By 1535, Jane was in her late twenties, with few marriage prospects. One contemporary considered her to be “no great beauty, so fair that one would call her rather pale than otherwise”.

She nonetheless attracted the king’s attention – perhaps when he visited Wolfhall in September 1535. Anne Boleyn blamed her miscarriage, in late January 1536, on the developing relationship, complaining to Henry that she had “caught that abandoned woman Jane sitting on your knees”. The queen and her maid had already come to blows.

Jane's rise: Anne’s failure to bear a son was an opportunity for Jane. When Henry sent her a letter and a purse of gold, she refused them, declaring that “she had no greater riches in the world than her honour, which she would not injure for a thousand deaths”.

Henry was smitten with this show of virtue, henceforth insisting on meeting her only with a chaperone. During April they discussed marriage and, on 20 May 1536 – the day after Anne Boleyn’s execution – the couple were betrothed. They married shortly afterwards.

Jane, who took as her motto “bound to obey and serve”, presented herself as meek and obedient. She was, however, instrumental in bringing Henry’s estranged daughter, princess Mary, back to court.

The new queen held conservative religious beliefs. This became apparent in October 1536 when she threw herself on her knees before the king at Windsor, begging him to restore the abbeys for fear that the rebellion, known as the Pilgrimage of Grace, was God’s judgment against him. In response, Henry publicly reminded her of the fate of Anne Boleyn, “enough to frighten a woman who is not very secure”.

Jane's fall: Without a son, Jane was vulnerable, and the postponement of her coronation was ominous. Finally, in March 1537, her pregnancy was announced. Henry was solicitous to his wife, resolving to stay close to her and ordering fat quails from Calais when she desired to eat them.

Jane endured a labour of two days and three nights before bearing a son at Hampton Court on 12 October, to great rejoicing. She was well enough to appear at the christening on 15 October, lying in an antechamber, wrapped in furs.

However, she soon sickened, with her attendants blamed for suffering “her to take great cold and to eat things that her fantasy in sickness called for”. In reality, she was probably suffering from puerperal, or childbed, fever. She died on 24 October.

Jane Seymour, as the only one of Henry VIII’s wives to die as queen, received a royal funeral at Windsor. She was later joined there by the king, who requested burial beside the mother of his only surviving son. Her child succeeded as Edward VI, but died at the age of 15.

Jane Seymour. (Popperfoto/Getty Images)

Historian Elizabeth Norton tells you everything you need to know about Jane Seymour, queen of England from 1536 to 1537 as the third wife of Henry VIII

Born: In around 1508

Died: 24 October 1537

Ruled: from 1536 to 1537

Family: the daughter of Sir John Seymour of Wolfhall in Wiltshire and his wife, Margery Wentworth

Successor: Anne of Cleves, Henry’s fourth wife

Remembered for: being the only wife to provide Henry with a son and male heir

Life: Jane Seymour, Henry VIII’s third wife, was born in around 1508. Her kinsman, the courtier Sir Francis Bryan, secured a place for her in the service of Queen Catherine of Aragon. Jane later transferred into the household of Catherine’s successor, Anne Boleyn.

By 1535, Jane was in her late twenties, with few marriage prospects. One contemporary considered her to be “no great beauty, so fair that one would call her rather pale than otherwise”.

She nonetheless attracted the king’s attention – perhaps when he visited Wolfhall in September 1535. Anne Boleyn blamed her miscarriage, in late January 1536, on the developing relationship, complaining to Henry that she had “caught that abandoned woman Jane sitting on your knees”. The queen and her maid had already come to blows.

Jane's rise: Anne’s failure to bear a son was an opportunity for Jane. When Henry sent her a letter and a purse of gold, she refused them, declaring that “she had no greater riches in the world than her honour, which she would not injure for a thousand deaths”.

Henry was smitten with this show of virtue, henceforth insisting on meeting her only with a chaperone. During April they discussed marriage and, on 20 May 1536 – the day after Anne Boleyn’s execution – the couple were betrothed. They married shortly afterwards.

Jane, who took as her motto “bound to obey and serve”, presented herself as meek and obedient. She was, however, instrumental in bringing Henry’s estranged daughter, princess Mary, back to court.

The new queen held conservative religious beliefs. This became apparent in October 1536 when she threw herself on her knees before the king at Windsor, begging him to restore the abbeys for fear that the rebellion, known as the Pilgrimage of Grace, was God’s judgment against him. In response, Henry publicly reminded her of the fate of Anne Boleyn, “enough to frighten a woman who is not very secure”.

Jane's fall: Without a son, Jane was vulnerable, and the postponement of her coronation was ominous. Finally, in March 1537, her pregnancy was announced. Henry was solicitous to his wife, resolving to stay close to her and ordering fat quails from Calais when she desired to eat them.

Jane endured a labour of two days and three nights before bearing a son at Hampton Court on 12 October, to great rejoicing. She was well enough to appear at the christening on 15 October, lying in an antechamber, wrapped in furs.

However, she soon sickened, with her attendants blamed for suffering “her to take great cold and to eat things that her fantasy in sickness called for”. In reality, she was probably suffering from puerperal, or childbed, fever. She died on 24 October.

Jane Seymour, as the only one of Henry VIII’s wives to die as queen, received a royal funeral at Windsor. She was later joined there by the king, who requested burial beside the mother of his only surviving son. Her child succeeded as Edward VI, but died at the age of 15.

Published on November 05, 2016 03:00

November 4, 2016

10 things you (probably) didn't know about Ancient Egypt

History Extra

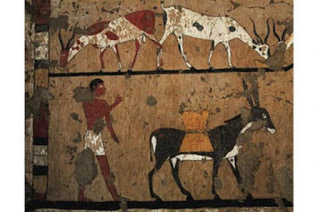

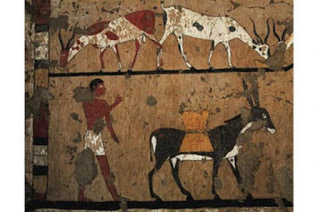

Fresco on the Tomb of Iti showing the transportation of wheat by donkey. Donkeys were more commonly used by the Ancient Egyptians than camels. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

1) They did not ride camelsThe camel was not used regularly in Egypt until the very end of the dynastic age. Instead, the Egyptians used donkeys as beasts of burden, and boats as a highly convenient means of transport. The River Nile flowed through the centre of their fertile land, creating a natural highway (and sewer!). The current helped those who needed to row from south to north, while the wind made life easy for those who wished to sail in the opposite direction. The river was linked to settlements, quarries and building sites by canals. Huge wooden barges were used to transport grain and heavy stone blocks; light papyrus boats ferried people about their daily business. And every day, high above the river, the sun god Ra was believed to sail across the sky in his solar boat. 2) Not everyone was mummifiedThe mummy – an eviscerated, dried and bandaged corpse – has become a defining Egyptian artefact. Yet mummification was an expensive and time-consuming process, reserved for the more wealthy members of society. The vast majority of Egypt’s dead were buried in simple pits in the desert. So why did the elite feel the need to mummify their dead? They believed that it was possible to live again after death, but only if the body retained a recognisable human form. Ironically, this could have been achieved quite easily by burying the dead in direct contact with the hot and sterile desert sand; a natural desiccation would then have occurred. But the elite wanted to be buried in coffins within tombs, and this meant that their corpses, no longer in direct contact with the sand, started to rot. The twin requirements of elaborate burial equipment plus a recognisable body led to the science of artificial mummification. 3) The living shared food with the deadThe tomb was designed as an eternal home for the mummified body and the ka spirit that lived beside it. An accessible tomb-chapel allowed families, well-wishers and priests to visit the deceased and leave the regular offerings that the ka required, while a hidden burial chamber protected the mummy from harm. Within the tomb-chapel, food and drink were offered on a regular basis. Having been spiritually consumed by the ka, they were then physically consumed by the living. During the ‘feast of the valley’, an annual festival of death and renewal, many families spent the night in the tomb-chapels of their ancestors. The hours of darkness were spent drinking and feasting by torchlight as the living celebrated their reunion with the dead. Food offerings to the dead. From a decorative detail from the Sarcophagus of Irinimenpu. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images) 4) Egyptian women had equal rights with menIn Egypt, men and women of equivalent social status were treated as equals in the eyes of the law. This meant that women could own, earn, buy, sell and inherit property. They could live unprotected by male guardians and, if widowed or divorced, could raise their own children. They could bring cases before, and be punished by, the law courts. And they were expected to deputise for an absent husband in matters of business. Everyone in Ancient Egypt was expected to marry, with husbands and wives being allocated complementary but opposite roles within the marriage. The wife, the ‘mistress of the house’, was responsible for all internal, domestic matters. She raised the children and ran the household while her husband, the dominant partner in the marriage, played the external, wage-earning role. 5) Scribes rarely wrote in hieroglyphs Hieroglyphic writing – a script consisting of many hundreds of intricate images – was beautiful to look at, but time-consuming to create. It was therefore reserved for the most important texts; the writings decorating tomb and temple walls, and texts recording royal achievements. As they went about their daily business, Egypt’s scribes routinely used hieratic – a simplified or shorthand form of hieroglyphic writing. Towards the end of the dynastic period they used demotic, an even more simplified version of hieratic. All three scripts were used to write the same ancient Egyptian language. Few of the ancients would have been able to read either hieroglyphs or hieratic: it is estimated that no more than 10 per cent (and perhaps considerably less) of the population was literate.

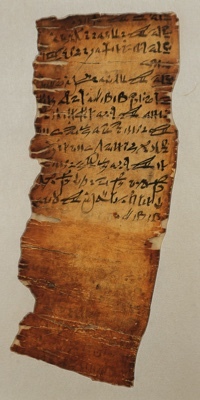

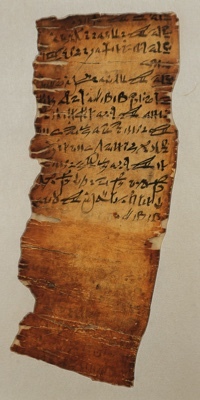

Food offerings to the dead. From a decorative detail from the Sarcophagus of Irinimenpu. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images) 4) Egyptian women had equal rights with menIn Egypt, men and women of equivalent social status were treated as equals in the eyes of the law. This meant that women could own, earn, buy, sell and inherit property. They could live unprotected by male guardians and, if widowed or divorced, could raise their own children. They could bring cases before, and be punished by, the law courts. And they were expected to deputise for an absent husband in matters of business. Everyone in Ancient Egypt was expected to marry, with husbands and wives being allocated complementary but opposite roles within the marriage. The wife, the ‘mistress of the house’, was responsible for all internal, domestic matters. She raised the children and ran the household while her husband, the dominant partner in the marriage, played the external, wage-earning role. 5) Scribes rarely wrote in hieroglyphs Hieroglyphic writing – a script consisting of many hundreds of intricate images – was beautiful to look at, but time-consuming to create. It was therefore reserved for the most important texts; the writings decorating tomb and temple walls, and texts recording royal achievements. As they went about their daily business, Egypt’s scribes routinely used hieratic – a simplified or shorthand form of hieroglyphic writing. Towards the end of the dynastic period they used demotic, an even more simplified version of hieratic. All three scripts were used to write the same ancient Egyptian language. Few of the ancients would have been able to read either hieroglyphs or hieratic: it is estimated that no more than 10 per cent (and perhaps considerably less) of the population was literate.  Legal text on parchment, written in hieratic: a list of witnesses during the settlement of a quarrel, 1000 BC. (Photo by DEA / G Dagli Orti/De Agostini/Getty Images) 6) The king of Egypt could be a womanIdeally the king of Egypt would be the son of the previous king. But this was not always possible, and the coronation ceremony had the power to convert the most unlikely candidate into an unassailable king. On at least three occasions women took the throne, ruling in their own right as female kings and using the full king’s titulary. The most successful of these female rulers, Hatshepsut, ruled Egypt for more than 20 prosperous years. In the English language, where ‘king’ is gender-specific, we might classify Sobeknefru, Hatshepsut and Tausret as queens regnant. In Egyptian, however, the phrase that we conventionally translate as ‘queen’ literally means ‘king’s wife’, and is entirely inappropriate for these women. 7) Few Egyptian men married their sistersSome of Egypt’s kings married their sisters or half-sisters. These incestuous marriages ensured that the queen was trained in her duties from birth, and that she remained entirely loyal to her husband and their children. They provided appropriate husbands for princesses who might otherwise remain unwed, while restricting the number of potential claimants for the throne. They even provided a link with the gods, several of whom (like Isis and Osiris) enjoyed incestuous unions. However, brother-sister marriages were never compulsory, and some of Egypt’s most prominent queens – including Nefertiti – were of non-royal birth. Incestuous marriages were not common outside the royal family until the very end of the dynastic age. The restricted Egyptian kingship terminology (‘father’, ‘mother’, ‘brother’, ‘sister’, ‘son’ and ‘daughter’ being the only terms used), and the tendency to apply these words loosely so that ‘sister’ could with equal validity describe an actual sister, a wife or a lover, has led to a lot of confusion over this issue. 8) Not all pharaohs built pyramidsAlmost all the pharaohs of the Old Kingdom (c2686–2125 BC) and Middle Kingdom (c2055–1650 BC) built pyramid-tombs in Egypt’s northern deserts. These highly conspicuous monuments linked the kings with the sun god Ra while replicating the mound of creation that emerged from the waters of chaos at the beginning of time. But by the start of the New Kingdom (c1550 BC) pyramid building was out of fashion. Kings would now build two entirely separate funerary monuments. Their mummies would be buried in hidden rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings on the west bank of the Nile at the southern city of Thebes, while a highly visible memorial temple, situated on the border between the cultivated land (home of the living), and the sterile desert (home of the dead), would serve as the focus of the royal mortuary cult. Following the collapse of the New Kingdom, subsequent kings were buried in tombs in northern Egypt: some of their burials have never been discovered. 9) The Great Pyramid was not built by slavesThe classical historian Herodotus believed that the Great Pyramid had been built by 100,000 slaves. His image of men, women and children desperately toiling in the harshest of conditions has proved remarkably popular with modern film producers. It is, however, wrong. Archaeological evidence indicates that the Great Pyramid was in fact built by a workforce of 5,000 permanent, salaried employees and up to 20,000 temporary workers. These workers were free men, summoned under the corvée system of national service to put in a three- or four-month shift on the building site before returning home. They were housed in a temporary camp near the pyramid, where they received payment in the form of food, drink, medical attention and, for those who died on duty, burial in the nearby cemetery.

Legal text on parchment, written in hieratic: a list of witnesses during the settlement of a quarrel, 1000 BC. (Photo by DEA / G Dagli Orti/De Agostini/Getty Images) 6) The king of Egypt could be a womanIdeally the king of Egypt would be the son of the previous king. But this was not always possible, and the coronation ceremony had the power to convert the most unlikely candidate into an unassailable king. On at least three occasions women took the throne, ruling in their own right as female kings and using the full king’s titulary. The most successful of these female rulers, Hatshepsut, ruled Egypt for more than 20 prosperous years. In the English language, where ‘king’ is gender-specific, we might classify Sobeknefru, Hatshepsut and Tausret as queens regnant. In Egyptian, however, the phrase that we conventionally translate as ‘queen’ literally means ‘king’s wife’, and is entirely inappropriate for these women. 7) Few Egyptian men married their sistersSome of Egypt’s kings married their sisters or half-sisters. These incestuous marriages ensured that the queen was trained in her duties from birth, and that she remained entirely loyal to her husband and their children. They provided appropriate husbands for princesses who might otherwise remain unwed, while restricting the number of potential claimants for the throne. They even provided a link with the gods, several of whom (like Isis and Osiris) enjoyed incestuous unions. However, brother-sister marriages were never compulsory, and some of Egypt’s most prominent queens – including Nefertiti – were of non-royal birth. Incestuous marriages were not common outside the royal family until the very end of the dynastic age. The restricted Egyptian kingship terminology (‘father’, ‘mother’, ‘brother’, ‘sister’, ‘son’ and ‘daughter’ being the only terms used), and the tendency to apply these words loosely so that ‘sister’ could with equal validity describe an actual sister, a wife or a lover, has led to a lot of confusion over this issue. 8) Not all pharaohs built pyramidsAlmost all the pharaohs of the Old Kingdom (c2686–2125 BC) and Middle Kingdom (c2055–1650 BC) built pyramid-tombs in Egypt’s northern deserts. These highly conspicuous monuments linked the kings with the sun god Ra while replicating the mound of creation that emerged from the waters of chaos at the beginning of time. But by the start of the New Kingdom (c1550 BC) pyramid building was out of fashion. Kings would now build two entirely separate funerary monuments. Their mummies would be buried in hidden rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings on the west bank of the Nile at the southern city of Thebes, while a highly visible memorial temple, situated on the border between the cultivated land (home of the living), and the sterile desert (home of the dead), would serve as the focus of the royal mortuary cult. Following the collapse of the New Kingdom, subsequent kings were buried in tombs in northern Egypt: some of their burials have never been discovered. 9) The Great Pyramid was not built by slavesThe classical historian Herodotus believed that the Great Pyramid had been built by 100,000 slaves. His image of men, women and children desperately toiling in the harshest of conditions has proved remarkably popular with modern film producers. It is, however, wrong. Archaeological evidence indicates that the Great Pyramid was in fact built by a workforce of 5,000 permanent, salaried employees and up to 20,000 temporary workers. These workers were free men, summoned under the corvée system of national service to put in a three- or four-month shift on the building site before returning home. They were housed in a temporary camp near the pyramid, where they received payment in the form of food, drink, medical attention and, for those who died on duty, burial in the nearby cemetery.  Great Pyramid of Cheops at Giza, which was not, as many believe, built by slaves. (Photo by MyLoupe/UIG via Getty Images) 10) Cleopatra many not have been beautifulCleopatra VII, last queen of ancient Egypt, won the hearts of Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, two of Rome’s most important men. Surely, then, she must have been an outstanding beauty? Her coins suggest that this was probably not the case. All show her in profile with a prominent nose, pronounced chin and deep-set eyes. Of course, Cleopatra’s coins reflect the skills of their makers, and it is entirely possible that the queen did not want to appear too feminine on the tokens that represented her sovereignty within and outside Egypt. Unfortunately we have no eyewitness description of the queen. However the classical historian Plutarch – who never actually met Cleopatra – tells us that her charm lay in her demeanour, and in her beautiful voice. Joyce Tyldesley, senior lecturer in Egyptology at the University of Manchester, is the author of Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt (Allen Lane 2010) and Tutankhamen’s Curse: the developing history of an Egyptian king (Profile 2012).

Great Pyramid of Cheops at Giza, which was not, as many believe, built by slaves. (Photo by MyLoupe/UIG via Getty Images) 10) Cleopatra many not have been beautifulCleopatra VII, last queen of ancient Egypt, won the hearts of Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, two of Rome’s most important men. Surely, then, she must have been an outstanding beauty? Her coins suggest that this was probably not the case. All show her in profile with a prominent nose, pronounced chin and deep-set eyes. Of course, Cleopatra’s coins reflect the skills of their makers, and it is entirely possible that the queen did not want to appear too feminine on the tokens that represented her sovereignty within and outside Egypt. Unfortunately we have no eyewitness description of the queen. However the classical historian Plutarch – who never actually met Cleopatra – tells us that her charm lay in her demeanour, and in her beautiful voice. Joyce Tyldesley, senior lecturer in Egyptology at the University of Manchester, is the author of Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt (Allen Lane 2010) and Tutankhamen’s Curse: the developing history of an Egyptian king (Profile 2012).

Fresco on the Tomb of Iti showing the transportation of wheat by donkey. Donkeys were more commonly used by the Ancient Egyptians than camels. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

1) They did not ride camelsThe camel was not used regularly in Egypt until the very end of the dynastic age. Instead, the Egyptians used donkeys as beasts of burden, and boats as a highly convenient means of transport. The River Nile flowed through the centre of their fertile land, creating a natural highway (and sewer!). The current helped those who needed to row from south to north, while the wind made life easy for those who wished to sail in the opposite direction. The river was linked to settlements, quarries and building sites by canals. Huge wooden barges were used to transport grain and heavy stone blocks; light papyrus boats ferried people about their daily business. And every day, high above the river, the sun god Ra was believed to sail across the sky in his solar boat. 2) Not everyone was mummifiedThe mummy – an eviscerated, dried and bandaged corpse – has become a defining Egyptian artefact. Yet mummification was an expensive and time-consuming process, reserved for the more wealthy members of society. The vast majority of Egypt’s dead were buried in simple pits in the desert. So why did the elite feel the need to mummify their dead? They believed that it was possible to live again after death, but only if the body retained a recognisable human form. Ironically, this could have been achieved quite easily by burying the dead in direct contact with the hot and sterile desert sand; a natural desiccation would then have occurred. But the elite wanted to be buried in coffins within tombs, and this meant that their corpses, no longer in direct contact with the sand, started to rot. The twin requirements of elaborate burial equipment plus a recognisable body led to the science of artificial mummification. 3) The living shared food with the deadThe tomb was designed as an eternal home for the mummified body and the ka spirit that lived beside it. An accessible tomb-chapel allowed families, well-wishers and priests to visit the deceased and leave the regular offerings that the ka required, while a hidden burial chamber protected the mummy from harm. Within the tomb-chapel, food and drink were offered on a regular basis. Having been spiritually consumed by the ka, they were then physically consumed by the living. During the ‘feast of the valley’, an annual festival of death and renewal, many families spent the night in the tomb-chapels of their ancestors. The hours of darkness were spent drinking and feasting by torchlight as the living celebrated their reunion with the dead.

Food offerings to the dead. From a decorative detail from the Sarcophagus of Irinimenpu. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images) 4) Egyptian women had equal rights with menIn Egypt, men and women of equivalent social status were treated as equals in the eyes of the law. This meant that women could own, earn, buy, sell and inherit property. They could live unprotected by male guardians and, if widowed or divorced, could raise their own children. They could bring cases before, and be punished by, the law courts. And they were expected to deputise for an absent husband in matters of business. Everyone in Ancient Egypt was expected to marry, with husbands and wives being allocated complementary but opposite roles within the marriage. The wife, the ‘mistress of the house’, was responsible for all internal, domestic matters. She raised the children and ran the household while her husband, the dominant partner in the marriage, played the external, wage-earning role. 5) Scribes rarely wrote in hieroglyphs Hieroglyphic writing – a script consisting of many hundreds of intricate images – was beautiful to look at, but time-consuming to create. It was therefore reserved for the most important texts; the writings decorating tomb and temple walls, and texts recording royal achievements. As they went about their daily business, Egypt’s scribes routinely used hieratic – a simplified or shorthand form of hieroglyphic writing. Towards the end of the dynastic period they used demotic, an even more simplified version of hieratic. All three scripts were used to write the same ancient Egyptian language. Few of the ancients would have been able to read either hieroglyphs or hieratic: it is estimated that no more than 10 per cent (and perhaps considerably less) of the population was literate.

Food offerings to the dead. From a decorative detail from the Sarcophagus of Irinimenpu. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images) 4) Egyptian women had equal rights with menIn Egypt, men and women of equivalent social status were treated as equals in the eyes of the law. This meant that women could own, earn, buy, sell and inherit property. They could live unprotected by male guardians and, if widowed or divorced, could raise their own children. They could bring cases before, and be punished by, the law courts. And they were expected to deputise for an absent husband in matters of business. Everyone in Ancient Egypt was expected to marry, with husbands and wives being allocated complementary but opposite roles within the marriage. The wife, the ‘mistress of the house’, was responsible for all internal, domestic matters. She raised the children and ran the household while her husband, the dominant partner in the marriage, played the external, wage-earning role. 5) Scribes rarely wrote in hieroglyphs Hieroglyphic writing – a script consisting of many hundreds of intricate images – was beautiful to look at, but time-consuming to create. It was therefore reserved for the most important texts; the writings decorating tomb and temple walls, and texts recording royal achievements. As they went about their daily business, Egypt’s scribes routinely used hieratic – a simplified or shorthand form of hieroglyphic writing. Towards the end of the dynastic period they used demotic, an even more simplified version of hieratic. All three scripts were used to write the same ancient Egyptian language. Few of the ancients would have been able to read either hieroglyphs or hieratic: it is estimated that no more than 10 per cent (and perhaps considerably less) of the population was literate.  Legal text on parchment, written in hieratic: a list of witnesses during the settlement of a quarrel, 1000 BC. (Photo by DEA / G Dagli Orti/De Agostini/Getty Images) 6) The king of Egypt could be a womanIdeally the king of Egypt would be the son of the previous king. But this was not always possible, and the coronation ceremony had the power to convert the most unlikely candidate into an unassailable king. On at least three occasions women took the throne, ruling in their own right as female kings and using the full king’s titulary. The most successful of these female rulers, Hatshepsut, ruled Egypt for more than 20 prosperous years. In the English language, where ‘king’ is gender-specific, we might classify Sobeknefru, Hatshepsut and Tausret as queens regnant. In Egyptian, however, the phrase that we conventionally translate as ‘queen’ literally means ‘king’s wife’, and is entirely inappropriate for these women. 7) Few Egyptian men married their sistersSome of Egypt’s kings married their sisters or half-sisters. These incestuous marriages ensured that the queen was trained in her duties from birth, and that she remained entirely loyal to her husband and their children. They provided appropriate husbands for princesses who might otherwise remain unwed, while restricting the number of potential claimants for the throne. They even provided a link with the gods, several of whom (like Isis and Osiris) enjoyed incestuous unions. However, brother-sister marriages were never compulsory, and some of Egypt’s most prominent queens – including Nefertiti – were of non-royal birth. Incestuous marriages were not common outside the royal family until the very end of the dynastic age. The restricted Egyptian kingship terminology (‘father’, ‘mother’, ‘brother’, ‘sister’, ‘son’ and ‘daughter’ being the only terms used), and the tendency to apply these words loosely so that ‘sister’ could with equal validity describe an actual sister, a wife or a lover, has led to a lot of confusion over this issue. 8) Not all pharaohs built pyramidsAlmost all the pharaohs of the Old Kingdom (c2686–2125 BC) and Middle Kingdom (c2055–1650 BC) built pyramid-tombs in Egypt’s northern deserts. These highly conspicuous monuments linked the kings with the sun god Ra while replicating the mound of creation that emerged from the waters of chaos at the beginning of time. But by the start of the New Kingdom (c1550 BC) pyramid building was out of fashion. Kings would now build two entirely separate funerary monuments. Their mummies would be buried in hidden rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings on the west bank of the Nile at the southern city of Thebes, while a highly visible memorial temple, situated on the border between the cultivated land (home of the living), and the sterile desert (home of the dead), would serve as the focus of the royal mortuary cult. Following the collapse of the New Kingdom, subsequent kings were buried in tombs in northern Egypt: some of their burials have never been discovered. 9) The Great Pyramid was not built by slavesThe classical historian Herodotus believed that the Great Pyramid had been built by 100,000 slaves. His image of men, women and children desperately toiling in the harshest of conditions has proved remarkably popular with modern film producers. It is, however, wrong. Archaeological evidence indicates that the Great Pyramid was in fact built by a workforce of 5,000 permanent, salaried employees and up to 20,000 temporary workers. These workers were free men, summoned under the corvée system of national service to put in a three- or four-month shift on the building site before returning home. They were housed in a temporary camp near the pyramid, where they received payment in the form of food, drink, medical attention and, for those who died on duty, burial in the nearby cemetery.

Legal text on parchment, written in hieratic: a list of witnesses during the settlement of a quarrel, 1000 BC. (Photo by DEA / G Dagli Orti/De Agostini/Getty Images) 6) The king of Egypt could be a womanIdeally the king of Egypt would be the son of the previous king. But this was not always possible, and the coronation ceremony had the power to convert the most unlikely candidate into an unassailable king. On at least three occasions women took the throne, ruling in their own right as female kings and using the full king’s titulary. The most successful of these female rulers, Hatshepsut, ruled Egypt for more than 20 prosperous years. In the English language, where ‘king’ is gender-specific, we might classify Sobeknefru, Hatshepsut and Tausret as queens regnant. In Egyptian, however, the phrase that we conventionally translate as ‘queen’ literally means ‘king’s wife’, and is entirely inappropriate for these women. 7) Few Egyptian men married their sistersSome of Egypt’s kings married their sisters or half-sisters. These incestuous marriages ensured that the queen was trained in her duties from birth, and that she remained entirely loyal to her husband and their children. They provided appropriate husbands for princesses who might otherwise remain unwed, while restricting the number of potential claimants for the throne. They even provided a link with the gods, several of whom (like Isis and Osiris) enjoyed incestuous unions. However, brother-sister marriages were never compulsory, and some of Egypt’s most prominent queens – including Nefertiti – were of non-royal birth. Incestuous marriages were not common outside the royal family until the very end of the dynastic age. The restricted Egyptian kingship terminology (‘father’, ‘mother’, ‘brother’, ‘sister’, ‘son’ and ‘daughter’ being the only terms used), and the tendency to apply these words loosely so that ‘sister’ could with equal validity describe an actual sister, a wife or a lover, has led to a lot of confusion over this issue. 8) Not all pharaohs built pyramidsAlmost all the pharaohs of the Old Kingdom (c2686–2125 BC) and Middle Kingdom (c2055–1650 BC) built pyramid-tombs in Egypt’s northern deserts. These highly conspicuous monuments linked the kings with the sun god Ra while replicating the mound of creation that emerged from the waters of chaos at the beginning of time. But by the start of the New Kingdom (c1550 BC) pyramid building was out of fashion. Kings would now build two entirely separate funerary monuments. Their mummies would be buried in hidden rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings on the west bank of the Nile at the southern city of Thebes, while a highly visible memorial temple, situated on the border between the cultivated land (home of the living), and the sterile desert (home of the dead), would serve as the focus of the royal mortuary cult. Following the collapse of the New Kingdom, subsequent kings were buried in tombs in northern Egypt: some of their burials have never been discovered. 9) The Great Pyramid was not built by slavesThe classical historian Herodotus believed that the Great Pyramid had been built by 100,000 slaves. His image of men, women and children desperately toiling in the harshest of conditions has proved remarkably popular with modern film producers. It is, however, wrong. Archaeological evidence indicates that the Great Pyramid was in fact built by a workforce of 5,000 permanent, salaried employees and up to 20,000 temporary workers. These workers were free men, summoned under the corvée system of national service to put in a three- or four-month shift on the building site before returning home. They were housed in a temporary camp near the pyramid, where they received payment in the form of food, drink, medical attention and, for those who died on duty, burial in the nearby cemetery.  Great Pyramid of Cheops at Giza, which was not, as many believe, built by slaves. (Photo by MyLoupe/UIG via Getty Images) 10) Cleopatra many not have been beautifulCleopatra VII, last queen of ancient Egypt, won the hearts of Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, two of Rome’s most important men. Surely, then, she must have been an outstanding beauty? Her coins suggest that this was probably not the case. All show her in profile with a prominent nose, pronounced chin and deep-set eyes. Of course, Cleopatra’s coins reflect the skills of their makers, and it is entirely possible that the queen did not want to appear too feminine on the tokens that represented her sovereignty within and outside Egypt. Unfortunately we have no eyewitness description of the queen. However the classical historian Plutarch – who never actually met Cleopatra – tells us that her charm lay in her demeanour, and in her beautiful voice. Joyce Tyldesley, senior lecturer in Egyptology at the University of Manchester, is the author of Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt (Allen Lane 2010) and Tutankhamen’s Curse: the developing history of an Egyptian king (Profile 2012).

Great Pyramid of Cheops at Giza, which was not, as many believe, built by slaves. (Photo by MyLoupe/UIG via Getty Images) 10) Cleopatra many not have been beautifulCleopatra VII, last queen of ancient Egypt, won the hearts of Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, two of Rome’s most important men. Surely, then, she must have been an outstanding beauty? Her coins suggest that this was probably not the case. All show her in profile with a prominent nose, pronounced chin and deep-set eyes. Of course, Cleopatra’s coins reflect the skills of their makers, and it is entirely possible that the queen did not want to appear too feminine on the tokens that represented her sovereignty within and outside Egypt. Unfortunately we have no eyewitness description of the queen. However the classical historian Plutarch – who never actually met Cleopatra – tells us that her charm lay in her demeanour, and in her beautiful voice. Joyce Tyldesley, senior lecturer in Egyptology at the University of Manchester, is the author of Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt (Allen Lane 2010) and Tutankhamen’s Curse: the developing history of an Egyptian king (Profile 2012).

Published on November 04, 2016 03:00

November 3, 2016

Two Mysterious Cavities Found Inside Great Pyramid May Be Secret Rooms

Ancient Origins

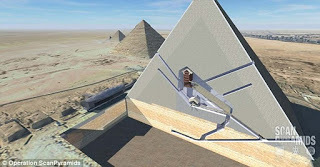

A team of researchers that have used cutting edge technology to scan the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt have discovered two previously unknown cavities inside the world-famous monument. Are they secret rooms or passages that have long been rumored to lie within?

The research team with the Scan Pyramid project applied a combination of infrared thermography, muon radiography imaging and elements of 3D reconstruction of the Great Pyramid. The results revealed two anomalies inside the construction that have been described as “cavities”.

The Ministry of Antiquities announced the discovery of two anomalies in Cairo on Thursday. The millennia-old pyramid has three known chambers, but researchers have speculated for many decades that there is much more to discover inside the 146-meter tall pyramid of King Khufu. According to Seeker, the researchers are able to confirm the existence of a 'void' hidden behind the northern side at the upper part of the entrance gate. The void may be a corridor which runs inside the structure. The second cavity was discovered on the northeast flank of the pyramid.

Does the Great Pyramid contain hidden chambers? Source: BigStockPhotoAccording to the statement by Scan Pyramids, muons are "similar to X-rays, which can penetrate the body and allow bone imaging" and "can go through hundreds of meters of stone before being absorbed. Judiciously placed detectors -- for example inside a pyramid, below a potential, unknown chamber -- can then record particle tracks and discern cavities from denser regions." The newly discovered spaces inside the pyramid may be the long expected lost element of the pyramid.

Does the Great Pyramid contain hidden chambers? Source: BigStockPhotoAccording to the statement by Scan Pyramids, muons are "similar to X-rays, which can penetrate the body and allow bone imaging" and "can go through hundreds of meters of stone before being absorbed. Judiciously placed detectors -- for example inside a pyramid, below a potential, unknown chamber -- can then record particle tracks and discern cavities from denser regions." The newly discovered spaces inside the pyramid may be the long expected lost element of the pyramid.

The work by the French researchers from the Scan Pyramids project has been made in collaboration with famous archeologist and former head of the Ministry of Antiquities, Dr Zahi Hawass. The project had initially been led by Nicholas Reeves, who used radar scans to reveal possible unknown chambers in the tomb of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings. However, that discovery was negated by Dr Hawass and other researchers, so Reeves didn't receive permission to excavate inside the tomb. Dr Hawass’ previous opinions about the scans make his appearance in the project rather surprising. As National Geographic wrote in May 6, 2016: ''After claiming that radar has never led to a single discovery in Egypt, Dr Hawass said, “We have to stop this media business, because there is nothing to publish. There is nothing to publish today or yesterday.''

Previously, but without the company of Dr Hawass, the same team examined the Bent Pyramid in Dahshur. The study became a huge success. As Natalia Klimczak from Ancient Origins reported in May 10, 2016:

A 3-D cutaway showing the inside of the Pyramid of Sneferu. Source:

Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, HIP Institute and the Faculty of Engineering (Cairo University)

A 3-D cutaway showing the inside of the Pyramid of Sneferu. Source:

Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, HIP Institute and the Faculty of Engineering (Cairo University)

The study is based on three modern technologies: infrared thermography, 3D scans with lasers, and cosmic-ray detectors. All of them have allowed the researchers to take better look inside the pyramids. Using the infrared thermography technique, the researchers measured the infrared energy emitted from the structures. The results of their testing were used to estimate the temperature distribution inside. Then, the team used lasers to bounce narrow pulses of light off the interiors of the Bent Pyramid. The last part of the research was locating cosmic particles, muons , within the structure, using detector plates.

Muons are formed at the moment when cosmic rays hit the Earth’s atmosphere. The particles rain down from the atmosphere, pass through empty spaces, and they can be absorbed or deflected by harder surfaces. They don't affect the human body, but if special detector plates are used, they can be tracked.

Kunihiro Morishima, from the Institute for Advanced Research of Nagoya University, Japan, placed 80 plates in the lower chamber of the Bent pyramid. They covered an area of about 10 square feet (0.93 sq. meters) and stayed there for 40 days. Following an analysis of these plates, the researchers were able to create 3D images of the pyramid, which revealed the shape of all of the chambers inside the pyramid.''

The size, shape and exact position of the newly-discovered cavities are now under investigation. To that end, the Scan Pyramids project has requested an extension of one year to complete the project.

Top image: A 3D cutaway view of the Great Pyramid of Giza revealing its interior chambers. Experts confirmed the existence of the mysterious cavities on Saturday after scanning the millennia-old monument with radiography equipment. Credit: Operation Scan Pyramids

By Natalia Klimzcak

A team of researchers that have used cutting edge technology to scan the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt have discovered two previously unknown cavities inside the world-famous monument. Are they secret rooms or passages that have long been rumored to lie within?

The research team with the Scan Pyramid project applied a combination of infrared thermography, muon radiography imaging and elements of 3D reconstruction of the Great Pyramid. The results revealed two anomalies inside the construction that have been described as “cavities”.

The Ministry of Antiquities announced the discovery of two anomalies in Cairo on Thursday. The millennia-old pyramid has three known chambers, but researchers have speculated for many decades that there is much more to discover inside the 146-meter tall pyramid of King Khufu. According to Seeker, the researchers are able to confirm the existence of a 'void' hidden behind the northern side at the upper part of the entrance gate. The void may be a corridor which runs inside the structure. The second cavity was discovered on the northeast flank of the pyramid.

Does the Great Pyramid contain hidden chambers? Source: BigStockPhotoAccording to the statement by Scan Pyramids, muons are "similar to X-rays, which can penetrate the body and allow bone imaging" and "can go through hundreds of meters of stone before being absorbed. Judiciously placed detectors -- for example inside a pyramid, below a potential, unknown chamber -- can then record particle tracks and discern cavities from denser regions." The newly discovered spaces inside the pyramid may be the long expected lost element of the pyramid.

Does the Great Pyramid contain hidden chambers? Source: BigStockPhotoAccording to the statement by Scan Pyramids, muons are "similar to X-rays, which can penetrate the body and allow bone imaging" and "can go through hundreds of meters of stone before being absorbed. Judiciously placed detectors -- for example inside a pyramid, below a potential, unknown chamber -- can then record particle tracks and discern cavities from denser regions." The newly discovered spaces inside the pyramid may be the long expected lost element of the pyramid.The work by the French researchers from the Scan Pyramids project has been made in collaboration with famous archeologist and former head of the Ministry of Antiquities, Dr Zahi Hawass. The project had initially been led by Nicholas Reeves, who used radar scans to reveal possible unknown chambers in the tomb of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings. However, that discovery was negated by Dr Hawass and other researchers, so Reeves didn't receive permission to excavate inside the tomb. Dr Hawass’ previous opinions about the scans make his appearance in the project rather surprising. As National Geographic wrote in May 6, 2016: ''After claiming that radar has never led to a single discovery in Egypt, Dr Hawass said, “We have to stop this media business, because there is nothing to publish. There is nothing to publish today or yesterday.''

Previously, but without the company of Dr Hawass, the same team examined the Bent Pyramid in Dahshur. The study became a huge success. As Natalia Klimczak from Ancient Origins reported in May 10, 2016:

''A team of researchers has presented the results of an analysis focused on the internal structure of the Bent Pyramid of pharaoh Sneferu (Snefru), a 4,500-year-old monument named after its sloping upper half.”

A 3-D cutaway showing the inside of the Pyramid of Sneferu. Source:

Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, HIP Institute and the Faculty of Engineering (Cairo University)

A 3-D cutaway showing the inside of the Pyramid of Sneferu. Source:

Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, HIP Institute and the Faculty of Engineering (Cairo University)

The study is based on three modern technologies: infrared thermography, 3D scans with lasers, and cosmic-ray detectors. All of them have allowed the researchers to take better look inside the pyramids. Using the infrared thermography technique, the researchers measured the infrared energy emitted from the structures. The results of their testing were used to estimate the temperature distribution inside. Then, the team used lasers to bounce narrow pulses of light off the interiors of the Bent Pyramid. The last part of the research was locating cosmic particles, muons , within the structure, using detector plates.

Muons are formed at the moment when cosmic rays hit the Earth’s atmosphere. The particles rain down from the atmosphere, pass through empty spaces, and they can be absorbed or deflected by harder surfaces. They don't affect the human body, but if special detector plates are used, they can be tracked.

Kunihiro Morishima, from the Institute for Advanced Research of Nagoya University, Japan, placed 80 plates in the lower chamber of the Bent pyramid. They covered an area of about 10 square feet (0.93 sq. meters) and stayed there for 40 days. Following an analysis of these plates, the researchers were able to create 3D images of the pyramid, which revealed the shape of all of the chambers inside the pyramid.''

The size, shape and exact position of the newly-discovered cavities are now under investigation. To that end, the Scan Pyramids project has requested an extension of one year to complete the project.

Top image: A 3D cutaway view of the Great Pyramid of Giza revealing its interior chambers. Experts confirmed the existence of the mysterious cavities on Saturday after scanning the millennia-old monument with radiography equipment. Credit: Operation Scan Pyramids

By Natalia Klimzcak

Published on November 03, 2016 03:00

November 2, 2016

All Souls' Day

November 2

The origins of All Souls' Day (Day of the Dead) in European folklore and folk belief are related to customs of ancestor veneration practiced worldwide, such as the Chinese Ghost Festival or the Latin American Day of the Dead. The Roman custom was that of the Lemuria.

The theological basis for the feast is the doctrine that the souls which,on departing from the body, are not perfectly cleansed from venial sins, or have not fully atoned for past transgressions, are debarred from the Beatific Vision, and that the faithful on earth can help them by prayers, alms deeds, and especially by the sacrifice of the Mass.

Published on November 02, 2016 03:00

November 1, 2016

All Saints' Day

November 1All Saints' Day

The origins of the holiday commemorating all the saints of the church are obscure, but by the mid-eighth century, November 1st was the day to honor all known and unknown saints in the Catholic Church. In 837, its general observance was ordered by Pope Gregory IV. The date may have been selected for its coincidence with pagan observations of the harvest, including the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain and the ancient Finnish celebration of Kekri.

Published on November 01, 2016 03:00

October 31, 2016

All Hallows' Eve

October 31

Historian Nicholas Rogers on the origin of All Hallows' Eve: while some folklorists have detected its origins in the Roman feast of Pomona, the goddess of fruits and seeds, or in the festival of the dead called Parentalia, it is more typically linked to the Celtic festival of Samhain, whose original spelling was Samuin. The name is derived from Old Irish and means roughly "summer's end". A similar festival was held by the ancient Britons and is known as Calan Gaeaf.

The festival of Samhain celebrates the end of the "lighter half" of the year and beginning of the "darker half", and is sometimes regarded as the "Celtic New Year".

The ancient Celts believed that the border between this world and the Otherworld became thin on Samhain, allowing spirits (both harmless and harmful) to pass through. The family's ancestors were honored and invited home while harmful spirits were warded off. It is believed that the need to ward off harmful spirits led to the wearing of costumes and masks.

Published on October 31, 2016 03:00

October 30, 2016

Book Launch - Before They Buried Thom Sloan by Lydia North

This is book six in The Spirits of Maine Series; ghost stories set in Maine. It is highly recommended that you begin with book one of the series to fully understand everything that happens in this story.

At 3:00 A.M. there is a knock at the door. A troubled young man is searching for a missing girl. He asks Eric Rivard to help. This search will be complicated by angry spirits that rival the ghost in ‘Waiting for Harvey’.

If you’re a fan of the Spirits of Maine Series you are in for a treat with this story!

Amazon link

About the AuthorLydia North is the pen name of Maine Author Kim Scott Kim Scott was born in Charleston, South Carolina and grew up in Scarborough, Maine. She presently resides in Southern Maine. She is the author of The Ruth Chernock Series (Regarding Ruth, In Ruth's Memory, On Grace's Shoulders and Pink Sky & Mourning) and The Manning Family Series (What Happened to Alex Manning? and Shuttering the Manning House). Under the pen name of Lydia North she wrote The Spirits of Maine Series.

Published on October 30, 2016 10:30

Margaret Tudor: The forgotten Tudor

History Extra

Bernard van Orley’s portrait of Margaret Tudor, whose marriage to James IV of Scotland would result in her falling out spectacularly with her younger brother. © Bridgeman Art Library

Bernard van Orley’s portrait of Margaret Tudor, whose marriage to James IV of Scotland would result in her falling out spectacularly with her younger brother. © Bridgeman Art Library

The crowds of Scots who gathered to meet their new queen as she approached Edinburgh in the summer of 1503 were understandably excited. While some of this enthusiasm may have been the product of drink generously supplied for the occasion, there was also a sense of optimism. Scotland wanted a queen. Its king, James IV, already had seven illegitimate children and needed a legitimate heir.

Now around 30, James also appreciated the generous dowry and diplomatic advantage his wife would bring. An English princess was arriving to seal a treaty of ‘perpetual peace’ between the two kingdoms and to provide the dynamic, ambitious king with the partner who would help him enhance Scotland’s prestige.

The girl was Margaret Tudor, the eldest daughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, and still only 13 years old. But she had been thoroughly trained for her new role and was determined to prove that she was equal to its demands.

Historians have tended to be dismissive of Margaret’s character and abilities. She is almost forgotten compared with other members of her famous family, yet we know a considerable amount about her, for Margaret was a prolific letter writer. Her extensive correspondence reveals her turbulent life in Scotland and the fraught relationship with her brother Henry VIII.

The homesick daughterTo Henry VII, August 1503

"God send me comfort that I and mine that be left here with me be well entreated… I wish I were with your Grace now and many times more… I pray God I may find it well for my welfare hereafter. Our Lord have you in his keeping. Written with the hand of your humble daughter, Margaret".

Henry VII, shown here in a c1505 painting, used his 13-year-old daughter as a pawn in a treaty of ‘perpetual peace’ between England and Scotland. © Bridgeman

Margaret’s letter to her father, Henry VII, betrays her homesickness and insecurities as she faced the reality of her new situation. Her response to her arrival in Scotland is hardly surprising: her beloved mother had died six months earlier and, in early July, she bid farewell to her father, knowing that she would probably never see him again. The journey north, lasting over three weeks, was exhausting.

Henry VII was determined to demonstrate, through his daughter’s progress into Scotland, the power and success of his dynasty. Margaret was constantly on show, meeting local dignitaries, attending banquets, changing dresses and jewels before she entered the towns along her way. Slim and red-headed, she cut a striking figure in her splendid gowns.

She crossed into Scotland on 1 August, and met her husband at Dalkeith Castle a few days later.

James IV’s visit was ostensibly a surprise, but had been carefully arranged. A charming womaniser, the king knew how to put his bride at her ease, though Margaret’s letter suggests that she did not fully appreciate this. Yet she rode pillion behind him into Edinburgh, to the great approbation of the populace, and James guided her through official functions with his arm around her waist.

The couple wore matching outfits of white damask for their glittering marriage at Holyrood Abbey. James spent extravagantly on preparing accommodation for his queen and on the wedding festivities: a quarter of his annual income went on wine alone. And he shaved his beard after the wedding, at his wife’s behest.

Margaret still felt, however, that he did not spend enough time with her, preferring to talk military matters with the Earl of Surrey, who had escorted her to Scotland and whose dictatorial manner she resented. She was clearly worried about the long-term treatment she and

her servants would receive.

The furious sisterTo Henry VIII, May 1513

"We cannot believe that of your mind or by your command we are so unkindly dealt with in our father’s legacy… Our husband knows it is witholden for his sake and will recompense us… We are ashamed therewith and wish God word had never been thereof. It is not worth such estimation as in your divers letters of the same and we lack nothing; our husband is ever the longer the better to us, as God knows".

James IV’s death in battle in 1513 left Margaret – shown in a 17th-century painting – feeling vulnerable and alone. © Bridgeman

These words, penned by an angry Margaret to her brother Henry VIII a decade after her arrival in Scotland, show that her fears about her new life north of the border were to prove unfounded. She swiftly settled into her position as Scotland’s queen, helped by the attention lavished on her by James IV. Clothed in rich furs and gowns and showered with jewels, she did, indeed, lack nothing.

And if James was by no means faithful (Margaret would not have known that his favourite mistress, Janet Kennedy, was pregnant with their third child at the time of her wedding), he was a considerate husband, easing her into the roles of consort and mother. She did not conceive until she was 16 and then produced a prince. But the child, like several others before the birth of the future James V, in 1512, did not survive.

The queen presided with her husband over a cultured court. James IV’s reign saw a flowering of literature and the arts in Scotland and he and his wife shared a love of music, dancing and masques.

Margaret must soon have realised that she had married a capable, popular ruler. James was a polymath whose interests ranged from naval matters to dentistry, and he was committed to being seen as a key player in Europe.

But his policies were to bring him into conflict with his young brother-in-law in England and deepen a rift between Margaret and Henry which may have had its origins in a reported childish spat when she, as a queen, briefly took precedence over him. Henry refused to pay Margaret the money and possessions left to her by both her father and brother, Prince Arthur. She was furious at this insult. But there was worse to come.

The desperate widowTo Henry VIII, November 1514

"My party-adversary continues in their malice and proceeds in their parliament, usurping the king’s authority, as (if) I and my lords were of no reputation, reputing us as rebels, wherefore I beseech that you would make haste with your army by sea and land. Brother, all the welfare of me and my children rests in your hands".

Eighteen months later, Margaret’s life was completely changed. Relations between England and Scotland, increasingly volatile, collapsed as Henry VIII declared war on France and the French king, Louis XII, requested the aid of his Scottish allies.

The decision by James IV to invade England was not, however, taken lightly. Margaret’s opposition to the move has been overstated – her earlier letter suggests strong support for her husband and she was already in the early stages of another pregnancy. Yet tragedy awaited. James engaged the English at the battle of Flodden in September 1513, on a remote hillside in Northumberland. His army outnumbered the English, and boasted the latest military technology but James had no experience of commanding a large force. The wiliness of his opponent, combined with treacherous marshy terrain, resulted in terrible slaughter. Ten thousand Scots perished, among them the king himself. Margaret was left a widow at the age of 23.

The shock to the queen was immense but Margaret acted with resolution, removing the toddler James V to the safety of Stirling Castle where he was crowned on 21 September. She was named as regent in her husband’s will, with one important proviso: she must not remarry.

But Scotland was fiercely patriarchal and Margaret was an Englishwoman. Exercising power was always going to be difficult. She gave birth to another son in April 1514, but in August she made a serious misjudgment: she married again. Her new husband, the Earl of Angus (right), was a member of a powerful family with a history of dividing Scottish politics.

Margaret’s need for strong male support cost her the regency and heralded a prolonged period of faction-fighting during her son’s troubled minority. Desperate to hold on to power and to her children, Margaret appealed to her brother for help. None was forthcoming.

The aggrieved motherAn attack on the Duke of Albany, 1516

"The Duke of Albany, by reason of his might and power, did take from me the king and duke, my said tender children. He removed and put me from out of my said castle [Stirling] being by enfeoffment paid for by the king my father of most blessed memory … and by his crafty and subtle ways made me signify in writing to the Pope’s Holiness and to my dearest brother the King of England and the King of France that I of my own mooting and free will did renounce my said office of tutrix and governess".

A painting of Margaret Tudor with a figure thought to be the Duke of Albany. Margaret was enraged when Albany, ruling Scotland as regent, seized her sons. © SCRAN

By the time the embittered Margaret wrote this official denunciation of the Duke of Albany, she had been forced to flee into England where she gave birth to a final child, her daughter by Angus, Lady Margaret Douglas. She wrote to Albany, the regent of Scotland who had replaced her, to announce the child’s arrival: “So it is that, by the grace of Almighty God, I am delivered, and have a Christian soul, being a young lady.” Her letter was sent in October 1515, from Harbottle Castle in Northumberland.

Margaret’s words reveal the depth of her anguish. John Stewart, Duke of Albany, was cousin to James IV and next in line to the Scottish throne after James V. He had been born and raised in France, and knew little of Scotland.

Initially, Margaret found Albany charming, but her position was further undermined when Henry VIII tried to have her sons kidnapped and brought to England. Determined to rule Scotland justly, Albany realised that he must gain control of the royal children. When Margaret refused, he besieged Stirling Castle and the queen was forced to submit. In a dramatic gesture intended to reinforce her son’s authority as king, she made little James V hand over the keys. Margaret had all the Tudor flair for a public occasion.

By September 1515, she decided that flight was the only option. Heavily pregnant, she rode for miles to the English border with Angus, leaving her jewels and wardrobe in Scotland. It was the last time her second husband would offer her any support.

The long recovery after a difficult labour was brightened by the arrival of new dresses sent from London but saddened by the death in December of her younger son. Margaret’s world had fallen apart.

The estranged wifeTo Henry VIII, 14 July 1524

"Also, my dearest brother, I have seen your writing touching my lord of Angus, which, as your Grace writes, is in your realm, and that ye purpose to send him here shortly, and that ye find him right wise… and that he is well minded of me and beareth me great love and favour. As yet he hath not shown, since his departing out of Scotland, that he desireth my good will and favour, neither by writing nor word… I trust, my dearest brother, that your Grace will not desire me to do nothing that may be hurt to me your sister, nor that may be occasion to hold me from the king my son".

Henry VIII treated his sister well but wanted her to return to Scotland. © Bridgeman

The queen stayed in England, in the company of her brother and sister, Mary, until 1517. The three had not been together for 13 years. But though Henry VIII treated Margaret well, he did not want her to stay, believing that her place was in Scotland.

It was typical of Henry’s muddled Scottish policy and his underlying misgivings about his sister that his preference for influencing Scottish politics was to work through the Anglophile Earl of Angus, Margaret’s husband. Unfortunately, the couple were now estranged and their relationship, despite a brief reconciliation in 1519, went from bad to worse. Angus took up with a former sweetheart and helped himself to the rents from Margaret’s lands, leaving the queen strapped for money and furious at his behaviour.

Taking his daughter Lady Margaret Douglas with him, the earl, who had fallen out with Albany, fled to France and then to England, where Lady Margaret was brought up at court. Feisty and attractive, she never really knew her mother, though her uncle proved an affectionate guardian.

In 1524, however, Queen Margaret’s time appeared to have come again. Albany returned to France and the queen and her supporters declared the 12-year-old James V of age to rule. Assuming the regency again, Margaret, who wanted a divorce, was not about to share power with Angus, and fired the guns of Edinburgh Castle on him when he appeared with armed men.

Her success was short-lived. At the end of 1525 Angus tricked fellow politicians and assumed full control of the king. For three years the boy chafed under the restrictions of his hated stepfather, while his mother outraged Henry VIII by pursuing her campaign for divorce.

The ageing matriarchTo Henry VIII, 12 May 1541

"Here has been great displeasure for the death of the prince and his brother, both with the king and the queen. I have done great diligence to put my dearest son and the queen his wife in comfort. I pray your grace to hold me excused that I write not at length… I can get no leisure".

James V and his wife Mary of Guise. © Bridgeman

Margaret’s marriage to Angus was annulled by the pope in 1527, the year Henry VIII began divorce proceedings against Catherine of Aragon. The following Easter, James V broke free from the domination of the Douglases and Angus fled again to England.

Margaret was elated, as she had fallen in love with a member of her household, Henry Stewart, and, at the age of 39, wanted to marry again. Her son gave permission but extracted a high price. He would not tolerate Margaret’s further meddling in Scottish politics. The queen felt sidelined and increasingly aggrieved, the more so as her third marriage was as unsuccessful as the union with Angus. Henry Stewart exploited her financially and was unfaithful.

Relief and a sense of fulfilment came from an unexpected source, Mary of Guise, James V’s second wife. This attractive and clever French noblewoman paid due attention to Margaret and the ‘old queen’ spent more time at court. In 1541 tragedy struck when Margaret’s two grandsons died within days of each other, leaving their parents devastated. Her support at this desperate time was greatly appreciated.

But Margaret’s own life was drawing to a close. In October, 1541, she suffered a stroke at Methven Castle, outside Perth, and died before her son could reach her. She was buried at St John’s Abbey in the city, alongside other Scottish rulers.

During the Reformation, Margaret’s tomb was desecrated and her skeleton burned – probably because she was English and Catholic. Like her first husband, James, she has no monument. But she would, no doubt, have been pleased that it was their great-grandson, James VI and I, who united the crowns of England and Scotland in 1603.

Linda Porter’s book about the rivalry between Tudors and Stuarts, Crown of Thistles: The Fatal Inheritance of Mary Queen of Scots, is out now in paperback (Macmillan)

Bernard van Orley’s portrait of Margaret Tudor, whose marriage to James IV of Scotland would result in her falling out spectacularly with her younger brother. © Bridgeman Art Library

Bernard van Orley’s portrait of Margaret Tudor, whose marriage to James IV of Scotland would result in her falling out spectacularly with her younger brother. © Bridgeman Art Library The crowds of Scots who gathered to meet their new queen as she approached Edinburgh in the summer of 1503 were understandably excited. While some of this enthusiasm may have been the product of drink generously supplied for the occasion, there was also a sense of optimism. Scotland wanted a queen. Its king, James IV, already had seven illegitimate children and needed a legitimate heir.

Now around 30, James also appreciated the generous dowry and diplomatic advantage his wife would bring. An English princess was arriving to seal a treaty of ‘perpetual peace’ between the two kingdoms and to provide the dynamic, ambitious king with the partner who would help him enhance Scotland’s prestige.

The girl was Margaret Tudor, the eldest daughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, and still only 13 years old. But she had been thoroughly trained for her new role and was determined to prove that she was equal to its demands.

Historians have tended to be dismissive of Margaret’s character and abilities. She is almost forgotten compared with other members of her famous family, yet we know a considerable amount about her, for Margaret was a prolific letter writer. Her extensive correspondence reveals her turbulent life in Scotland and the fraught relationship with her brother Henry VIII.

The homesick daughterTo Henry VII, August 1503

"God send me comfort that I and mine that be left here with me be well entreated… I wish I were with your Grace now and many times more… I pray God I may find it well for my welfare hereafter. Our Lord have you in his keeping. Written with the hand of your humble daughter, Margaret".

Henry VII, shown here in a c1505 painting, used his 13-year-old daughter as a pawn in a treaty of ‘perpetual peace’ between England and Scotland. © Bridgeman

Margaret’s letter to her father, Henry VII, betrays her homesickness and insecurities as she faced the reality of her new situation. Her response to her arrival in Scotland is hardly surprising: her beloved mother had died six months earlier and, in early July, she bid farewell to her father, knowing that she would probably never see him again. The journey north, lasting over three weeks, was exhausting.

Henry VII was determined to demonstrate, through his daughter’s progress into Scotland, the power and success of his dynasty. Margaret was constantly on show, meeting local dignitaries, attending banquets, changing dresses and jewels before she entered the towns along her way. Slim and red-headed, she cut a striking figure in her splendid gowns.

She crossed into Scotland on 1 August, and met her husband at Dalkeith Castle a few days later.

James IV’s visit was ostensibly a surprise, but had been carefully arranged. A charming womaniser, the king knew how to put his bride at her ease, though Margaret’s letter suggests that she did not fully appreciate this. Yet she rode pillion behind him into Edinburgh, to the great approbation of the populace, and James guided her through official functions with his arm around her waist.

The couple wore matching outfits of white damask for their glittering marriage at Holyrood Abbey. James spent extravagantly on preparing accommodation for his queen and on the wedding festivities: a quarter of his annual income went on wine alone. And he shaved his beard after the wedding, at his wife’s behest.

Margaret still felt, however, that he did not spend enough time with her, preferring to talk military matters with the Earl of Surrey, who had escorted her to Scotland and whose dictatorial manner she resented. She was clearly worried about the long-term treatment she and

her servants would receive.

The furious sisterTo Henry VIII, May 1513

"We cannot believe that of your mind or by your command we are so unkindly dealt with in our father’s legacy… Our husband knows it is witholden for his sake and will recompense us… We are ashamed therewith and wish God word had never been thereof. It is not worth such estimation as in your divers letters of the same and we lack nothing; our husband is ever the longer the better to us, as God knows".

James IV’s death in battle in 1513 left Margaret – shown in a 17th-century painting – feeling vulnerable and alone. © Bridgeman

These words, penned by an angry Margaret to her brother Henry VIII a decade after her arrival in Scotland, show that her fears about her new life north of the border were to prove unfounded. She swiftly settled into her position as Scotland’s queen, helped by the attention lavished on her by James IV. Clothed in rich furs and gowns and showered with jewels, she did, indeed, lack nothing.

And if James was by no means faithful (Margaret would not have known that his favourite mistress, Janet Kennedy, was pregnant with their third child at the time of her wedding), he was a considerate husband, easing her into the roles of consort and mother. She did not conceive until she was 16 and then produced a prince. But the child, like several others before the birth of the future James V, in 1512, did not survive.

The queen presided with her husband over a cultured court. James IV’s reign saw a flowering of literature and the arts in Scotland and he and his wife shared a love of music, dancing and masques.

Margaret must soon have realised that she had married a capable, popular ruler. James was a polymath whose interests ranged from naval matters to dentistry, and he was committed to being seen as a key player in Europe.

But his policies were to bring him into conflict with his young brother-in-law in England and deepen a rift between Margaret and Henry which may have had its origins in a reported childish spat when she, as a queen, briefly took precedence over him. Henry refused to pay Margaret the money and possessions left to her by both her father and brother, Prince Arthur. She was furious at this insult. But there was worse to come.

The desperate widowTo Henry VIII, November 1514

"My party-adversary continues in their malice and proceeds in their parliament, usurping the king’s authority, as (if) I and my lords were of no reputation, reputing us as rebels, wherefore I beseech that you would make haste with your army by sea and land. Brother, all the welfare of me and my children rests in your hands".

Eighteen months later, Margaret’s life was completely changed. Relations between England and Scotland, increasingly volatile, collapsed as Henry VIII declared war on France and the French king, Louis XII, requested the aid of his Scottish allies.

The decision by James IV to invade England was not, however, taken lightly. Margaret’s opposition to the move has been overstated – her earlier letter suggests strong support for her husband and she was already in the early stages of another pregnancy. Yet tragedy awaited. James engaged the English at the battle of Flodden in September 1513, on a remote hillside in Northumberland. His army outnumbered the English, and boasted the latest military technology but James had no experience of commanding a large force. The wiliness of his opponent, combined with treacherous marshy terrain, resulted in terrible slaughter. Ten thousand Scots perished, among them the king himself. Margaret was left a widow at the age of 23.

The shock to the queen was immense but Margaret acted with resolution, removing the toddler James V to the safety of Stirling Castle where he was crowned on 21 September. She was named as regent in her husband’s will, with one important proviso: she must not remarry.

But Scotland was fiercely patriarchal and Margaret was an Englishwoman. Exercising power was always going to be difficult. She gave birth to another son in April 1514, but in August she made a serious misjudgment: she married again. Her new husband, the Earl of Angus (right), was a member of a powerful family with a history of dividing Scottish politics.

Margaret’s need for strong male support cost her the regency and heralded a prolonged period of faction-fighting during her son’s troubled minority. Desperate to hold on to power and to her children, Margaret appealed to her brother for help. None was forthcoming.

The aggrieved motherAn attack on the Duke of Albany, 1516