MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 79

October 18, 2016

The Normans: a timeline

History Extra

Harold’s foot soldiers try to defend themselves at Hastings in a scene from the Bayeux tapestry. (Getty Images)

Harold’s foot soldiers try to defend themselves at Hastings in a scene from the Bayeux tapestry. (Getty Images)

911According to later writer Dudo of Saint-Quentin, in this year the king of the Franks, Charles the Simple, grants land around the city of Rouen to Rollo, or Rolf, leader of the Vikings who have settled the region: the duchy of Normandy is founded. In return Rollo undertakes to protect the area and to receive baptism, taking the Christian name Robert.

1002Emma, sister of Duke Richard II of Normandy, marries Æthelred (‘the Unready’), king of England. Their son, the future Edward the Confessor, flees to Normandy 14 years later when England is conquered by King Cnut, and remains there for the next quarter of a century. This dynastic link is later used as one of the justifications for the Norman conquest.

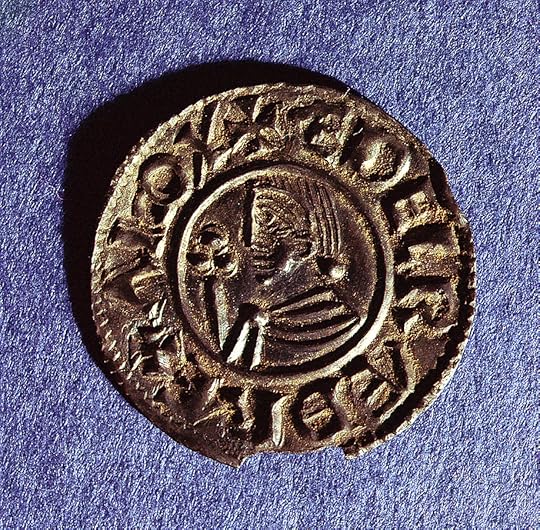

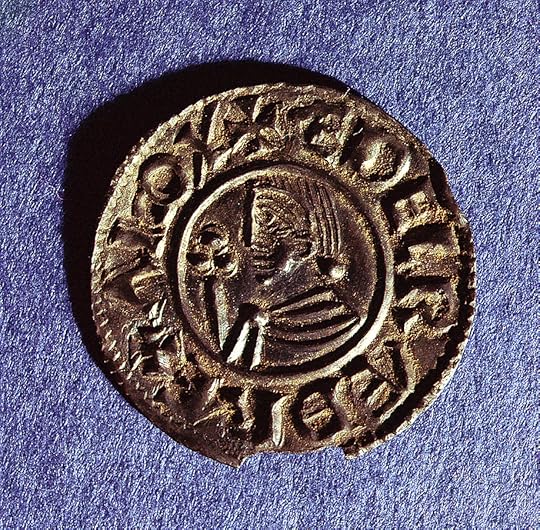

An English silver penny minted c991 during the reign of King Æthelred the Unready. (Getty Images)

1016A group of Norman pilgrims en route to Jerusalem are ‘invited’ to help liberate southern Italy from Byzantine (Greek) control. Norman knights have already been operating as mercenaries here since the turn of the first millennium, selling their military services to rival Lombard, Greek and Muslim rulers.

1035Having ruled Normandy for eight years, Duke Robert I falls ill on his return from

a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and dies at Nicaea. By prior agreement, Robert is succeeded by his illegitimate son William, the future Conqueror of England, then aged just seven or eight. A decade of violence follows as Norman nobles fight each other for control of the young duke and his duchy.

1051Duke William visits England. His rule in Normandy now established, and newly married to Matilda of Flanders, William crosses the Channel to speak with his second cousin, King Edward the Confessor of England. The subject of their conference is unknown, but later chroniclers assert that at this time Edward promises William the English succession.

1059Pope Nicholas II invests the Norman Robert Guiscard with the dukedoms of Apulia, Calabria and Sicily. The popes had opposed the ambitions of the Normans in Italy, but defeat in battle at Civitate in southern Italy in 1053 had caused them to reconsider. In 1060 Robert and his brother Roger embark on the conquest of Sicily, and Roger subsequently rules the island as its great count.

The Norman army of Roger I defeats a vast Saracen army at Cerami, Sicily in 1063, in a 19th-century painting by Prosper Lafaye. (Getty Images)

1066Edward the Confessor dies on 5 January, and the throne is immediately taken by his brother-in-law Harold Godwinson, the most powerful earl in England, with strong popular backing. Harold defeats his Norwegian namesake at Stamford Bridge in September. But on 14 October William’s Norman forces defeat Harold’s army at Hastings. William is crowned as England’s king on Christmas Day.

1069The initial years of William’s reign in England are marked by almost constant English rebellion, matched by violent Norman repression. In autumn 1069 a fresh English revolt is triggered by a Danish invasion. William responds by laying waste to the country north of the Humber, destroying crops and cattle in a campaign that becomes known as the Harrying of the North, leading to widespread famine and death.

1086Worried by the threat of Danish invasion, at Christmas 1085 William decides to survey his kingdom – partly to assess its wealth, and partly to settle arguments about landownership created by 20 years of conquest. The results, later redacted and compiled as Domesday Book, are probably brought to him in August 1086 at Old Sarum (near Salisbury), where all landowners swear an oath to him.

A 19th-century illustration shows scribes compiling the results of William’s great survey in Domesday Book. (Getty Images)

1087William retaliates against a French invasion of Normandy. While attacking Mantes he is taken ill or injured – possibly damaging his intestines on the pommel of his saddle – and retires to Rouen, where he dies on 9 September. Taken to Caen for burial, his body proves too fat for its stone sarcophagus, and bursts when monks try to force it in. His eldest surviving son, Robert Curthose, becomes duke of Normandy, while England passes to his second son, William Rufus.

1096Following a call to arms by Pope Urban II in 1095, many Normans set out towards the Holy Land on the First Crusade, determined to recover Jerusalem. Among them are Robert Curthose, who mortgages Normandy to his younger brother, William Rufus, and William the Conqueror’s notorious half-brother, Bishop Odo of Bayeux. Odo dies en route and is buried in Palermo, but Robert goes on to win victories in Palestine and is present when Jerusalem falls.

The siege of Jerusalem during the First Crusade in 1099, shown in a 13th-century illumination. (Getty Images)

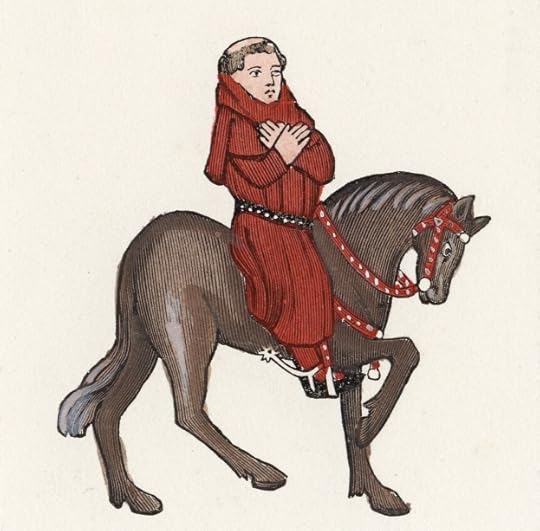

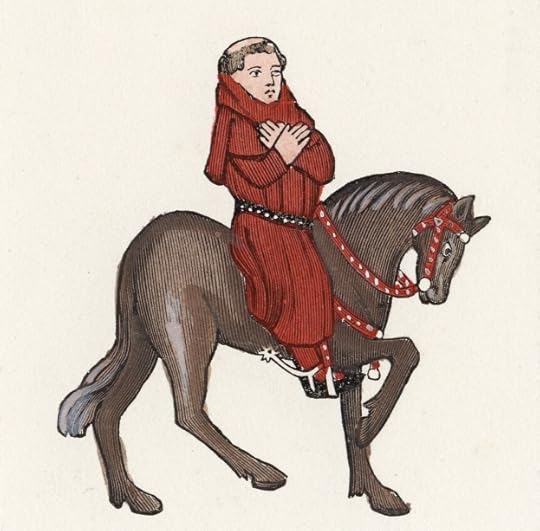

1100Having succeeded his father in 1087 and defeated Robert Curthose’s attempts to unseat him, the rule of William II (‘Rufus’, depicted below) seems secure. But on 2 August 1100, while hunting in the New Forest with some of his barons, William is struck by a stray arrow and killed. His body is carted to Winchester for burial, and the English throne passes to his younger brother, Henry, who is crowned in Westminster Abbey just three days later.

1101Roger I of Sicily dies. By the end of his long rule, Count Roger has gained control over the whole of Sicily – the central Muslim town of Enna submitted in 1087, and the last emirs in the southeast surrendered in 1091. He is briefly succeeded by his eldest son, Simon, but the new count dies in 1105 and is succeeded by his younger brother, Roger II.

1120On 25 November Henry I sets out across the Channel from Normandy to England. One of the vessels in his fleet, the White Ship, strikes a rock soon after its departure, with the loss of all but one of its passengers. One of the drowned is the king’s only legitimate son, William Ætheling. Henry responds by fixing the succession on his daughter, Matilda, and marrying her to Geoffrey Plantagenet, count of Anjou.

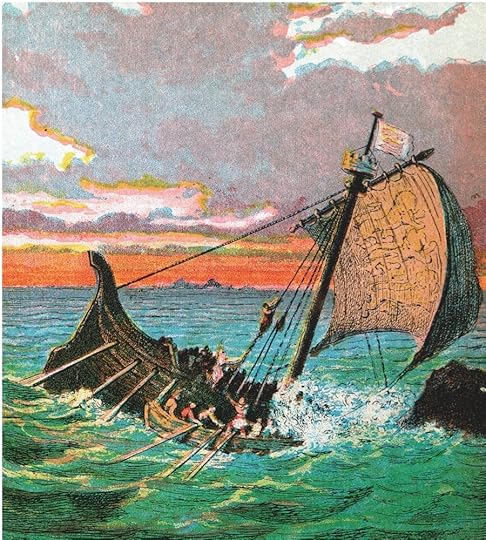

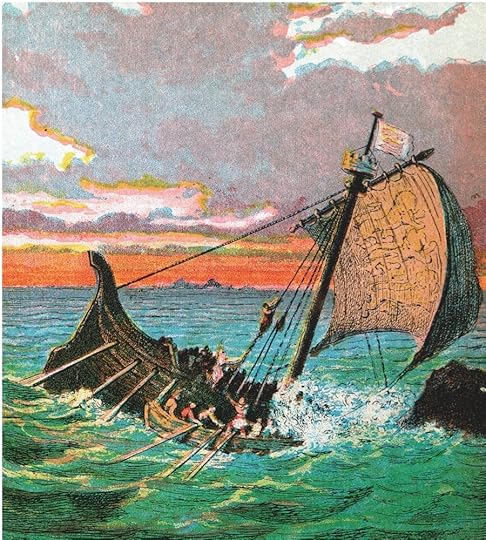

The wreck of King Henry’s White Ship, shown in a c1850 illustration. (Getty Images)

1130Roger II is crowned king of Sicily, having pushed for royal status in order to assert his authority over the barons of southern Italy. A disputed papal succession in 1130 has provided an opportunity and, in return for support against a papal rival, Pope Anacletus II confers the kingship on Roger in September. He is crowned in Palermo Cathedral on Christmas Day.

1135Henry I dies in Normandy on 1 December, reportedly after ignoring doctor’s orders and eating his favourite dish: lampreys. His body is shipped back to England for burial at the abbey he founded in Reading. Many of his barons reject the rule of his daughter, Matilda, instead backing his nephew, Stephen, who is crowned as England’s new king on 22 December.

1154King Stephen, the last Norman king of England, dies. His death ends the vicious civil war between him and his cousin Matilda that lasted for most of his reign. As a result of the Treaty of Wallingford, which Stephen was pressured to sign in 1153, he is succeeded by Matilda’s son Henry of Anjou, who takes the throne as Henry II.

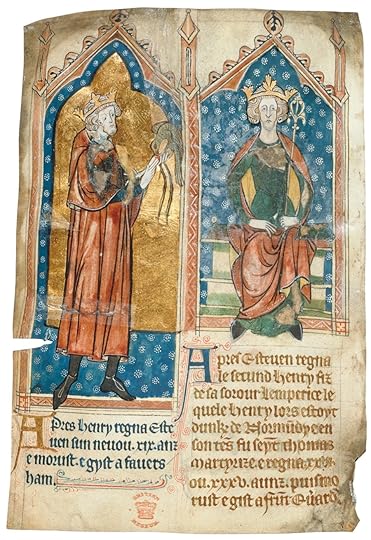

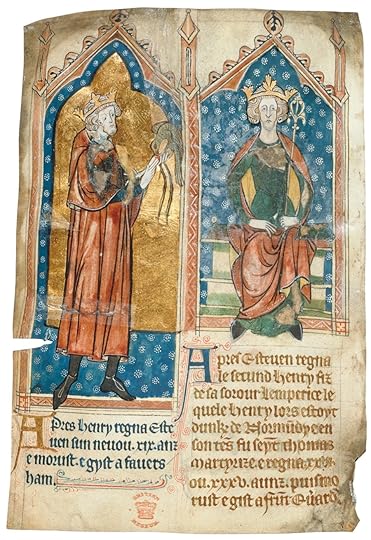

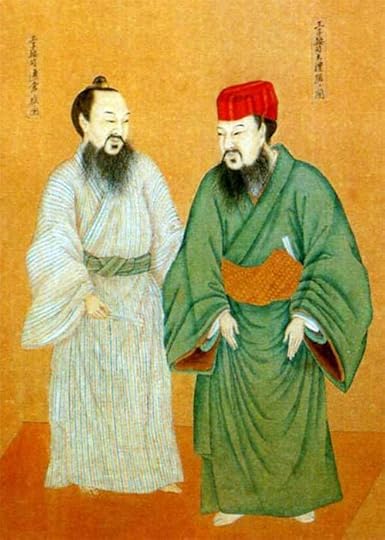

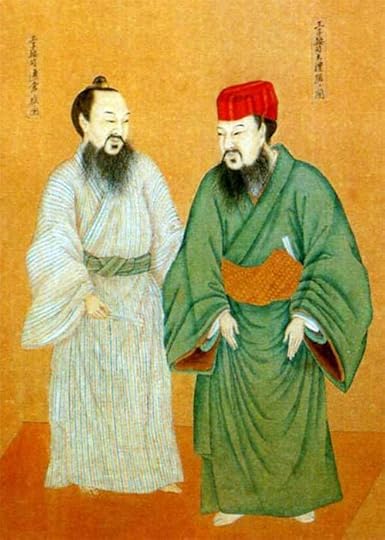

King Stephen is pictured as a falconer alongside his successor, Henry II, in a late-13th-century manuscript. (AKG Images)

1174King William II of Sicily begins the construction of the great church at Monreale (‘Mount Royal’), nine miles from his capital at Palermo. The building is a fusion of Byzantine, Latin and Muslim architectural styles, and is decorated throughout with gold mosaics, including the earliest depiction of Thomas Becket, martyred in 1170.

1194Norman rule on Sicily ends. Tancred of Lecce, son of Roger III, Duke of Apulia, seizes the throne on William’s death in 1189; on his death in 1194 he is succeeded by his young son, William III. Eight months later, Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI, husband of Roger II’s daughter Constance, invades Sicily and is crowned in Palermo on Christmas Day. The following day, Constance gives birth to their son, the future Frederick II.

Tancred (crowned figure on right), king of Sicily until 1194. (AKG Images)

1204King John loses Normandy to the French. The youngest son of Henry II, John had succeeded to England, Normandy, Anjou and Aquitaine after the death of his elder brother, Richard the Lionheart, in 1199. But in just five years he lost almost all of his continental lands to his rival King Philip Augustus of France – the end of England’s link with Normandy.

Marc Morris is a historian who specialises in the Middle Ages.

Harold’s foot soldiers try to defend themselves at Hastings in a scene from the Bayeux tapestry. (Getty Images)

Harold’s foot soldiers try to defend themselves at Hastings in a scene from the Bayeux tapestry. (Getty Images) 911According to later writer Dudo of Saint-Quentin, in this year the king of the Franks, Charles the Simple, grants land around the city of Rouen to Rollo, or Rolf, leader of the Vikings who have settled the region: the duchy of Normandy is founded. In return Rollo undertakes to protect the area and to receive baptism, taking the Christian name Robert.

1002Emma, sister of Duke Richard II of Normandy, marries Æthelred (‘the Unready’), king of England. Their son, the future Edward the Confessor, flees to Normandy 14 years later when England is conquered by King Cnut, and remains there for the next quarter of a century. This dynastic link is later used as one of the justifications for the Norman conquest.

An English silver penny minted c991 during the reign of King Æthelred the Unready. (Getty Images)

1016A group of Norman pilgrims en route to Jerusalem are ‘invited’ to help liberate southern Italy from Byzantine (Greek) control. Norman knights have already been operating as mercenaries here since the turn of the first millennium, selling their military services to rival Lombard, Greek and Muslim rulers.

1035Having ruled Normandy for eight years, Duke Robert I falls ill on his return from

a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and dies at Nicaea. By prior agreement, Robert is succeeded by his illegitimate son William, the future Conqueror of England, then aged just seven or eight. A decade of violence follows as Norman nobles fight each other for control of the young duke and his duchy.

1051Duke William visits England. His rule in Normandy now established, and newly married to Matilda of Flanders, William crosses the Channel to speak with his second cousin, King Edward the Confessor of England. The subject of their conference is unknown, but later chroniclers assert that at this time Edward promises William the English succession.

1059Pope Nicholas II invests the Norman Robert Guiscard with the dukedoms of Apulia, Calabria and Sicily. The popes had opposed the ambitions of the Normans in Italy, but defeat in battle at Civitate in southern Italy in 1053 had caused them to reconsider. In 1060 Robert and his brother Roger embark on the conquest of Sicily, and Roger subsequently rules the island as its great count.

The Norman army of Roger I defeats a vast Saracen army at Cerami, Sicily in 1063, in a 19th-century painting by Prosper Lafaye. (Getty Images)

1066Edward the Confessor dies on 5 January, and the throne is immediately taken by his brother-in-law Harold Godwinson, the most powerful earl in England, with strong popular backing. Harold defeats his Norwegian namesake at Stamford Bridge in September. But on 14 October William’s Norman forces defeat Harold’s army at Hastings. William is crowned as England’s king on Christmas Day.

1069The initial years of William’s reign in England are marked by almost constant English rebellion, matched by violent Norman repression. In autumn 1069 a fresh English revolt is triggered by a Danish invasion. William responds by laying waste to the country north of the Humber, destroying crops and cattle in a campaign that becomes known as the Harrying of the North, leading to widespread famine and death.

1086Worried by the threat of Danish invasion, at Christmas 1085 William decides to survey his kingdom – partly to assess its wealth, and partly to settle arguments about landownership created by 20 years of conquest. The results, later redacted and compiled as Domesday Book, are probably brought to him in August 1086 at Old Sarum (near Salisbury), where all landowners swear an oath to him.

A 19th-century illustration shows scribes compiling the results of William’s great survey in Domesday Book. (Getty Images)

1087William retaliates against a French invasion of Normandy. While attacking Mantes he is taken ill or injured – possibly damaging his intestines on the pommel of his saddle – and retires to Rouen, where he dies on 9 September. Taken to Caen for burial, his body proves too fat for its stone sarcophagus, and bursts when monks try to force it in. His eldest surviving son, Robert Curthose, becomes duke of Normandy, while England passes to his second son, William Rufus.

1096Following a call to arms by Pope Urban II in 1095, many Normans set out towards the Holy Land on the First Crusade, determined to recover Jerusalem. Among them are Robert Curthose, who mortgages Normandy to his younger brother, William Rufus, and William the Conqueror’s notorious half-brother, Bishop Odo of Bayeux. Odo dies en route and is buried in Palermo, but Robert goes on to win victories in Palestine and is present when Jerusalem falls.

The siege of Jerusalem during the First Crusade in 1099, shown in a 13th-century illumination. (Getty Images)

1100Having succeeded his father in 1087 and defeated Robert Curthose’s attempts to unseat him, the rule of William II (‘Rufus’, depicted below) seems secure. But on 2 August 1100, while hunting in the New Forest with some of his barons, William is struck by a stray arrow and killed. His body is carted to Winchester for burial, and the English throne passes to his younger brother, Henry, who is crowned in Westminster Abbey just three days later.

1101Roger I of Sicily dies. By the end of his long rule, Count Roger has gained control over the whole of Sicily – the central Muslim town of Enna submitted in 1087, and the last emirs in the southeast surrendered in 1091. He is briefly succeeded by his eldest son, Simon, but the new count dies in 1105 and is succeeded by his younger brother, Roger II.

1120On 25 November Henry I sets out across the Channel from Normandy to England. One of the vessels in his fleet, the White Ship, strikes a rock soon after its departure, with the loss of all but one of its passengers. One of the drowned is the king’s only legitimate son, William Ætheling. Henry responds by fixing the succession on his daughter, Matilda, and marrying her to Geoffrey Plantagenet, count of Anjou.

The wreck of King Henry’s White Ship, shown in a c1850 illustration. (Getty Images)

1130Roger II is crowned king of Sicily, having pushed for royal status in order to assert his authority over the barons of southern Italy. A disputed papal succession in 1130 has provided an opportunity and, in return for support against a papal rival, Pope Anacletus II confers the kingship on Roger in September. He is crowned in Palermo Cathedral on Christmas Day.

1135Henry I dies in Normandy on 1 December, reportedly after ignoring doctor’s orders and eating his favourite dish: lampreys. His body is shipped back to England for burial at the abbey he founded in Reading. Many of his barons reject the rule of his daughter, Matilda, instead backing his nephew, Stephen, who is crowned as England’s new king on 22 December.

1154King Stephen, the last Norman king of England, dies. His death ends the vicious civil war between him and his cousin Matilda that lasted for most of his reign. As a result of the Treaty of Wallingford, which Stephen was pressured to sign in 1153, he is succeeded by Matilda’s son Henry of Anjou, who takes the throne as Henry II.

King Stephen is pictured as a falconer alongside his successor, Henry II, in a late-13th-century manuscript. (AKG Images)

1174King William II of Sicily begins the construction of the great church at Monreale (‘Mount Royal’), nine miles from his capital at Palermo. The building is a fusion of Byzantine, Latin and Muslim architectural styles, and is decorated throughout with gold mosaics, including the earliest depiction of Thomas Becket, martyred in 1170.

1194Norman rule on Sicily ends. Tancred of Lecce, son of Roger III, Duke of Apulia, seizes the throne on William’s death in 1189; on his death in 1194 he is succeeded by his young son, William III. Eight months later, Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI, husband of Roger II’s daughter Constance, invades Sicily and is crowned in Palermo on Christmas Day. The following day, Constance gives birth to their son, the future Frederick II.

Tancred (crowned figure on right), king of Sicily until 1194. (AKG Images)

1204King John loses Normandy to the French. The youngest son of Henry II, John had succeeded to England, Normandy, Anjou and Aquitaine after the death of his elder brother, Richard the Lionheart, in 1199. But in just five years he lost almost all of his continental lands to his rival King Philip Augustus of France – the end of England’s link with Normandy.

Marc Morris is a historian who specialises in the Middle Ages.

Published on October 18, 2016 03:00

October 17, 2016

Bringing a Bronze Age Face to Light: Face of the Greek Griffin Warrior

Ancient Origins

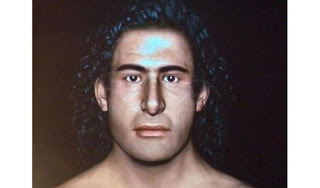

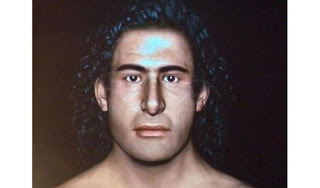

Researchers believe that a Bronze Age skeleton found near the Mycenaean palace of Nestor was once a handsome man with long black hair. Their reconstruction of his appearance was based on an analysis of his skull and an artifact recovered in his rich grave. This is just the latest in discoveries related to the burial of the so-called Griffin Warrior.

The facial reconstruction was one of the topics presented on October 6, 2016 at The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Greece. Themanews.com reports that the image of the Griffin warrior’s face was created by Lynne Schepartz and Tobias Houlton from the University of Witwatersrand, South Africa.

Schepartz and Houlton based their reconstruction on the man’s skull and a stamp which was found alongside his remains. Sharon R. Stocker, one of the University of Cincinnati archaeologists who unearthed the tomb in 2015, said the stamp provided an inspiration for the long black hair shown in the representation and “It seems he was a handsome man.” That stamp is one of the artifacts Stocker and the rest of the team will make public next year.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

Some of the jewelry recovered from the grave. (Griffin Warrior Tomb)The grave of the 30- 35-year-old warrior was discovered by Sharon Stocker and Jack Davis, another University of Cincinnati archaeologist, during their 2015 excavations at the Palace of Nestor on Greece’s Peloponnese peninsula. The man was buried in a shaft grave that measured 5 ft. (1.5 meters) deep, 4 ft. (1.2 meters) wide, and 8 ft. (2.4 meters) long.

Secrets of the Four Gold Rings from the Tomb of the Griffin Warrior RevealedFacial Reconstruction of Bronze Age Woman from 3,700-Year-Old Skull Brings Her Story Back to LifeAccording to Themanews.com, the Griffin Warrior’s grave was intact except for the one-ton stone which had crushed the wooden coffin containing the man’s remains. When April Holloway wrote of the discovery for Ancient Origins she said that the unplundered tomb predates the palace of Nestor and contained many intriguing artifacts.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

Looking inside the Griffin Warrior tomb, complete with the fallen stone. (Griffin Warrior Tomb)Apart from his weapons - a bronze sword with a gold and ivory handle and a gold-hilted dagger, Holloway wrote that the archaeologists found “gold rings, an ornate string of pearls, 50 Minoan seal stones carved with imagery of goddesses, silver vases, gold cups, a bronze mirror, ivory combs, an ivory plaque carved with a griffin [from which the tomb received its name], and Minoan-style gold jewelry decorated with figures of deities, animals, and floral motifs.”

Artifacts within the grave. (Griffin Warrior Tomb)The four gold rings which were found in the tomb also made the news recently for their magnificent craftsmanship and the tales that accompany their designs.

Artifacts within the grave. (Griffin Warrior Tomb)The four gold rings which were found in the tomb also made the news recently for their magnificent craftsmanship and the tales that accompany their designs.

The rings were crafted with multiple sheets of gold by a skilled person who managed to create highly detailed Minoan iconography on the small artifacts. At first, it was believed that the rings and some of the other artifacts showing Minoan themes were loot from a raid of Crete, however further study suggests that they may be examples of Mycenaean-Minoan cultural transfer instead.

Lord of Sipan: First Time Real Face of 2,000-Year-Old Mochican Priest RevealedThe Face of a Beautiful Egyptian Woman Brought to Life from 2,000-Year-Old MummyAs Jack Davis, told EurekAlert!:

One of the four gold rings found in the tomb of the Griffin Warrior depicts a leaping bull. (

Jennifer Stephens/University of Cincinnati

)Finally, Davis told the New York Times that they are uncertain if the warrior was buried by Minoans or Mycenaeans who had adopted elements of Minoan culture. He said, “Whoever they are, they are the people introducing Minoan ways to the mainland and forging Mycenaean culture. They were probably dressing like Minoans and building their houses according to styles used on Crete, using Minoan building techniques.”

One of the four gold rings found in the tomb of the Griffin Warrior depicts a leaping bull. (

Jennifer Stephens/University of Cincinnati

)Finally, Davis told the New York Times that they are uncertain if the warrior was buried by Minoans or Mycenaeans who had adopted elements of Minoan culture. He said, “Whoever they are, they are the people introducing Minoan ways to the mainland and forging Mycenaean culture. They were probably dressing like Minoans and building their houses according to styles used on Crete, using Minoan building techniques.”

Top Image: Facial Reconstruction of the so-called ‘Griffin Warrior.’ Source: Tornosnews

By Alicia McDermott

Researchers believe that a Bronze Age skeleton found near the Mycenaean palace of Nestor was once a handsome man with long black hair. Their reconstruction of his appearance was based on an analysis of his skull and an artifact recovered in his rich grave. This is just the latest in discoveries related to the burial of the so-called Griffin Warrior.

The facial reconstruction was one of the topics presented on October 6, 2016 at The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Greece. Themanews.com reports that the image of the Griffin warrior’s face was created by Lynne Schepartz and Tobias Houlton from the University of Witwatersrand, South Africa.

Schepartz and Houlton based their reconstruction on the man’s skull and a stamp which was found alongside his remains. Sharon R. Stocker, one of the University of Cincinnati archaeologists who unearthed the tomb in 2015, said the stamp provided an inspiration for the long black hair shown in the representation and “It seems he was a handsome man.” That stamp is one of the artifacts Stocker and the rest of the team will make public next year.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]Some of the jewelry recovered from the grave. (Griffin Warrior Tomb)The grave of the 30- 35-year-old warrior was discovered by Sharon Stocker and Jack Davis, another University of Cincinnati archaeologist, during their 2015 excavations at the Palace of Nestor on Greece’s Peloponnese peninsula. The man was buried in a shaft grave that measured 5 ft. (1.5 meters) deep, 4 ft. (1.2 meters) wide, and 8 ft. (2.4 meters) long.

Secrets of the Four Gold Rings from the Tomb of the Griffin Warrior RevealedFacial Reconstruction of Bronze Age Woman from 3,700-Year-Old Skull Brings Her Story Back to LifeAccording to Themanews.com, the Griffin Warrior’s grave was intact except for the one-ton stone which had crushed the wooden coffin containing the man’s remains. When April Holloway wrote of the discovery for Ancient Origins she said that the unplundered tomb predates the palace of Nestor and contained many intriguing artifacts.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]Looking inside the Griffin Warrior tomb, complete with the fallen stone. (Griffin Warrior Tomb)Apart from his weapons - a bronze sword with a gold and ivory handle and a gold-hilted dagger, Holloway wrote that the archaeologists found “gold rings, an ornate string of pearls, 50 Minoan seal stones carved with imagery of goddesses, silver vases, gold cups, a bronze mirror, ivory combs, an ivory plaque carved with a griffin [from which the tomb received its name], and Minoan-style gold jewelry decorated with figures of deities, animals, and floral motifs.”

Artifacts within the grave. (Griffin Warrior Tomb)The four gold rings which were found in the tomb also made the news recently for their magnificent craftsmanship and the tales that accompany their designs.

Artifacts within the grave. (Griffin Warrior Tomb)The four gold rings which were found in the tomb also made the news recently for their magnificent craftsmanship and the tales that accompany their designs.The rings were crafted with multiple sheets of gold by a skilled person who managed to create highly detailed Minoan iconography on the small artifacts. At first, it was believed that the rings and some of the other artifacts showing Minoan themes were loot from a raid of Crete, however further study suggests that they may be examples of Mycenaean-Minoan cultural transfer instead.

Lord of Sipan: First Time Real Face of 2,000-Year-Old Mochican Priest RevealedThe Face of a Beautiful Egyptian Woman Brought to Life from 2,000-Year-Old MummyAs Jack Davis, told EurekAlert!:

“People have suggested that the findings in the grave are treasure, like Blackbeard's treasure, that was just buried along with the dead as impressive contraband. We think that already in this period the people on the mainland already understood much of the religious iconography on these rings, and they were already buying into religious concepts on the island of Crete. This isn't just loot […] it may be loot, but they're specifically selecting loot that transmits messages that are understandable to them.”The researchers also said that “it is no coincidence that the Griffin Warrior was found buried with a bronze bull's head staff capped by prominent horns, which were likely a symbol of his power and authority.”

One of the four gold rings found in the tomb of the Griffin Warrior depicts a leaping bull. (

Jennifer Stephens/University of Cincinnati

)Finally, Davis told the New York Times that they are uncertain if the warrior was buried by Minoans or Mycenaeans who had adopted elements of Minoan culture. He said, “Whoever they are, they are the people introducing Minoan ways to the mainland and forging Mycenaean culture. They were probably dressing like Minoans and building their houses according to styles used on Crete, using Minoan building techniques.”

One of the four gold rings found in the tomb of the Griffin Warrior depicts a leaping bull. (

Jennifer Stephens/University of Cincinnati

)Finally, Davis told the New York Times that they are uncertain if the warrior was buried by Minoans or Mycenaeans who had adopted elements of Minoan culture. He said, “Whoever they are, they are the people introducing Minoan ways to the mainland and forging Mycenaean culture. They were probably dressing like Minoans and building their houses according to styles used on Crete, using Minoan building techniques.”Top Image: Facial Reconstruction of the so-called ‘Griffin Warrior.’ Source: Tornosnews

By Alicia McDermott

Published on October 17, 2016 03:00

October 16, 2016

Magnificent 3D Reconstruction of Pompeii Home Sheds Light on Life in the Ancient City Before its Destruction

Ancient Origins

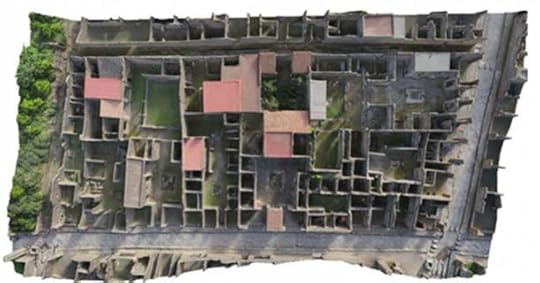

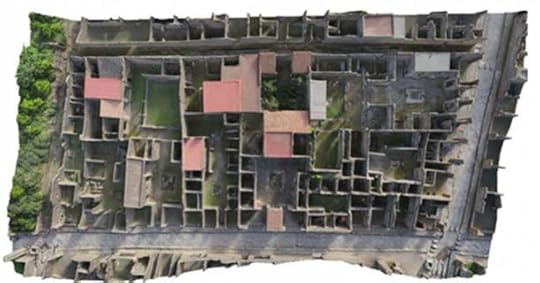

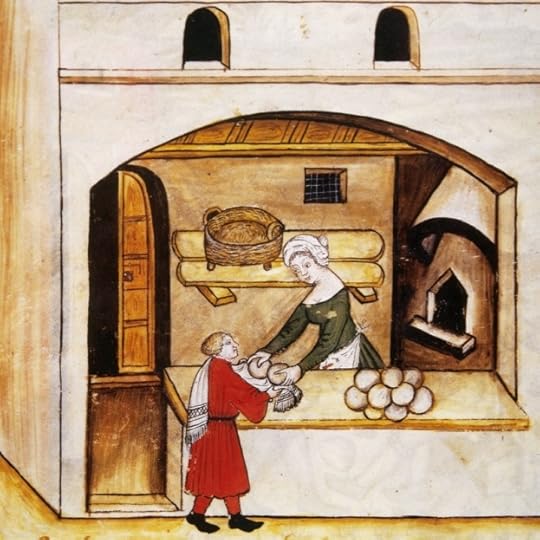

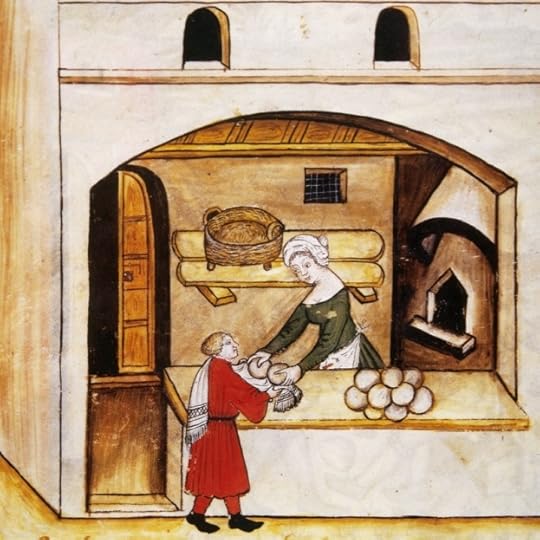

Pompeii was an ancient Roman city near modern-day Naples in Italy, which was wiped out and buried under 6 meters of ash and pumice following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. It is an eerie feeling to walk the empty streets of Pompeii and to view shops and homes left virtually untouched for nearly two millennia. One home still contains a complete loaf of bread sitting in the oven, perfectly preserved by a coating of ash. Now everyone has the opportunity to walk the streets and peer inside homes thanks to a detailed 3D digital reconstruction of an entire Pompeian city-block.

The impressive initiative is part of the Swedish Pompeii Project, which began in 2000 at the Swedish Institute in Rome, and sheds light on the lives of the people who lived and died in the ancient Roman city in the first century AD. It is now overseen by researchers at Sweden's Lund University. The researchers virtually reconstructed an entire block, including a magnificent house that belonged to a banker called Caecilius Iucundus. The home was designed to allow as much light as possible to shine into the rooms, especially in the most elaborate room known as the tabularium (city archive).

The city block that was reconstructed, called Insula VI, includes two large and wealthy estates, in addition to the house of the banker. There is also a bakery, tavern, laundry, and a garden with fountains.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

An overhead view of Insula VI, the city block that was reconstructed. Credit: Swedish Pompeii Project The well preserved mosaic floor pieces and fully intact windows made of translucent gypsum enabled archaeologists to piece together what the home would have looked like nearly 2,000 years ago.

Archeologists also studied the water and sewer systems and discovered important information about the social hierarchies of the town – namely, that retailers were dependent on wealthy families for water, which they held in large tanks or wells, until the construction of a large aqueduct in later days.

The team was led by Anne-Marie Leander Touati, former director of the Swedish Institute in Rome and now Professor of Archaeology and Ancient History at Lund University. 3D scanning of the Pompeii city block took place during fieldwork expeditions between 2011 and 2012 with the use of FARO Focus3D and FARO PHOTON 120 laser scanners.

"By combining new technology with more traditional methods, we can describe Pompeii in greater detail and more accurately than was previously possible,'' said digital archaeologist Nicoló Dell´Unto [via ScienceAlert].

The reconstruction is fully documented in the article “Reconstructing the Original Splendour of the House of Caecilius Iucundus: A Complete Methodology for Virtual Archaeology Aimed at Digital Exhibition”. The part of the city known as Insula V1 was chosen due to its location at the crossing of two of Pompeii's main thoroughfares. The project was carried out using technical and literary texts, paintings, drawings, pictures taken via drone, and scans.

Pompeii still hides many treasures and secrets. Researchers have been excavating it for centuries, but there is still a lot to discover. In September, 2015, Mark Miller from Ancient Origins, reported on a discovery of an unexpected tomb in Pompeii:

''Archaeologists have unearthed an extremely rare 4 th century BC tomb of a woman dating to before the Roman presence in Pompeii, when the Samnites occupied the area. Evidence suggests the Romans knew of the burial site and chose not to build on it, allowing the site to survive undisturbed for more than two millennia. Scholars hope the find will give important insight into the Samnite people, an Italic people who once fought against the Romans.

Inside the tomb, archaeologists found amphorae or earthenware jugs, still with substances in them. The clay jars were found to come from various parts of Italy, showing that the Samnite people had contact outside their own area on the western coast of Italy. Researchers will examine the contents of the jars, but an initial examinations revealed food, wine and cosmetics, providing a fascinating insight into Samnite diet and culture.

A French archaeological team based in Naples discovered the tomb by surprise.

“The burial objects will show us much about the role of women in Samnite society and can provide us with a useful social insight,” Massimo Osanna, the archaeological superintendent of Pompeii said , according to theLocal.it .

After the Samnite Wars in the 4 th century BC, the town became subject to Rome while still retaining administrative and linguistic autonomy. Osanna said little is known about Pompeii before Rome annexed it.

The Samnite inhabitants of early Pompeii took part in the wars against Rome along with other towns of the Campania region in 89 BC. Rome laid siege to the town but did not subdue it until 80 BC.''

Top image: Digital reconstruction of a Pompeii home. Credit: Swedish Pompeii Project .

By Natalia Klimzcak

Pompeii was an ancient Roman city near modern-day Naples in Italy, which was wiped out and buried under 6 meters of ash and pumice following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. It is an eerie feeling to walk the empty streets of Pompeii and to view shops and homes left virtually untouched for nearly two millennia. One home still contains a complete loaf of bread sitting in the oven, perfectly preserved by a coating of ash. Now everyone has the opportunity to walk the streets and peer inside homes thanks to a detailed 3D digital reconstruction of an entire Pompeian city-block.

The impressive initiative is part of the Swedish Pompeii Project, which began in 2000 at the Swedish Institute in Rome, and sheds light on the lives of the people who lived and died in the ancient Roman city in the first century AD. It is now overseen by researchers at Sweden's Lund University. The researchers virtually reconstructed an entire block, including a magnificent house that belonged to a banker called Caecilius Iucundus. The home was designed to allow as much light as possible to shine into the rooms, especially in the most elaborate room known as the tabularium (city archive).

The city block that was reconstructed, called Insula VI, includes two large and wealthy estates, in addition to the house of the banker. There is also a bakery, tavern, laundry, and a garden with fountains.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]An overhead view of Insula VI, the city block that was reconstructed. Credit: Swedish Pompeii Project The well preserved mosaic floor pieces and fully intact windows made of translucent gypsum enabled archaeologists to piece together what the home would have looked like nearly 2,000 years ago.

Archeologists also studied the water and sewer systems and discovered important information about the social hierarchies of the town – namely, that retailers were dependent on wealthy families for water, which they held in large tanks or wells, until the construction of a large aqueduct in later days.

The team was led by Anne-Marie Leander Touati, former director of the Swedish Institute in Rome and now Professor of Archaeology and Ancient History at Lund University. 3D scanning of the Pompeii city block took place during fieldwork expeditions between 2011 and 2012 with the use of FARO Focus3D and FARO PHOTON 120 laser scanners.

"By combining new technology with more traditional methods, we can describe Pompeii in greater detail and more accurately than was previously possible,'' said digital archaeologist Nicoló Dell´Unto [via ScienceAlert].

The reconstruction is fully documented in the article “Reconstructing the Original Splendour of the House of Caecilius Iucundus: A Complete Methodology for Virtual Archaeology Aimed at Digital Exhibition”. The part of the city known as Insula V1 was chosen due to its location at the crossing of two of Pompeii's main thoroughfares. The project was carried out using technical and literary texts, paintings, drawings, pictures taken via drone, and scans.

Pompeii still hides many treasures and secrets. Researchers have been excavating it for centuries, but there is still a lot to discover. In September, 2015, Mark Miller from Ancient Origins, reported on a discovery of an unexpected tomb in Pompeii:

''Archaeologists have unearthed an extremely rare 4 th century BC tomb of a woman dating to before the Roman presence in Pompeii, when the Samnites occupied the area. Evidence suggests the Romans knew of the burial site and chose not to build on it, allowing the site to survive undisturbed for more than two millennia. Scholars hope the find will give important insight into the Samnite people, an Italic people who once fought against the Romans.

Inside the tomb, archaeologists found amphorae or earthenware jugs, still with substances in them. The clay jars were found to come from various parts of Italy, showing that the Samnite people had contact outside their own area on the western coast of Italy. Researchers will examine the contents of the jars, but an initial examinations revealed food, wine and cosmetics, providing a fascinating insight into Samnite diet and culture.

A French archaeological team based in Naples discovered the tomb by surprise.

“The burial objects will show us much about the role of women in Samnite society and can provide us with a useful social insight,” Massimo Osanna, the archaeological superintendent of Pompeii said , according to theLocal.it .

After the Samnite Wars in the 4 th century BC, the town became subject to Rome while still retaining administrative and linguistic autonomy. Osanna said little is known about Pompeii before Rome annexed it.

The Samnite inhabitants of early Pompeii took part in the wars against Rome along with other towns of the Campania region in 89 BC. Rome laid siege to the town but did not subdue it until 80 BC.''

Top image: Digital reconstruction of a Pompeii home. Credit: Swedish Pompeii Project .

By Natalia Klimzcak

Published on October 16, 2016 03:00

October 15, 2016

Secrets of the Four Gold Rings from the Tomb of the Griffin Warrior Revealed

Ancient Origins

The story behind four magnificent ancient Greek gold signet rings is finally coming to light. One year after they were found in the grave of a Bronze Age Greek warrior, the rings are now taking center stage for both their craftsmanship and the tales that accompany their designs. The researchers studying the artifacts say that they are some of the best examples of Mycenaean-Minoan cultural transfer and early Greek society.

EurekAlert! reports that the rings were crafted with multiple sheets of gold by a highly skilled person. The researchers were astounded by the individual’s abilities in making the rings. As Shari Stocker, co-discoverer of the tomb and a senior research associate in the University of Cincinnati's Department of Classics, said, “They're carving these before the microscope and electric tools. This is exquisite workmanship for something so tiny and old and really shows the skill of Minoan craftsmen.”

The images depicted on the rings show highly detailed Minoan iconography. One ring depicts the iconic Minoan scene of leaping bull. Interestingly, the others all show female figures as the main characters. One of these is an image of a probable goddess holding a staff with two birds accompanying here on a mountain.

A ring showing a bull which was found in the tomb of the Griffin Warrior. (

Jennifer Stephens/University of Cincinnati

)Another ring shows five women around a shrine by the water. According to Eurekalert! this is the largest known gold signet ring from the Aegean world. The last of the four rings depicts a woman making a bull’s horn offering to a goddess. The goddess in the image is seated on a throne and holding a mirror.

A ring showing a bull which was found in the tomb of the Griffin Warrior. (

Jennifer Stephens/University of Cincinnati

)Another ring shows five women around a shrine by the water. According to Eurekalert! this is the largest known gold signet ring from the Aegean world. The last of the four rings depicts a woman making a bull’s horn offering to a goddess. The goddess in the image is seated on a throne and holding a mirror.

At first, it was believed that the rings and some of the other artifacts showing Minoan themes were loot from a raid of Crete. However, other grave goods which can be linked to the images shown on the rings suggested to the researchers that they were something more than simple loot.

3,500-Year-Old Unplundered Warrior Tomb with Huge Treasure Hoard found in Greece The Woman Behind the Man: Celtic Warrior Scathach, Teacher of WarriorsApril Holloway discussed some of the other artifacts found last year in the tomb of the so-called “Griffin Warrior.” Apart of his weapons - a bronze sword with a gold and ivory handle and a gold-hilted dagger, the archaeologists found the four gold rings and “an ornate string of pearls, 50 Minoan seal stones carved with imagery of goddesses, silver vases, gold cups, a bronze mirror, ivory combs, an ivory plaque carved with a griffin [from which the tomb received its name], and Minoan-style gold jewelry decorated with figures of deities, animals, and floral motifs.”

Specifically, one can see similarities between the mirror which was found with the warrior’s skeleton and that held by the goddess in the fourth ring. The sacred Minoan symbol of the bull, which EurekAlert! points out is also seen in Mycenaean imagery, is depicted in the rings with the bull-leaping scene and the bull horn offering. The researchers also told EurekAlert! that “it is no coincidence that the Griffin Warrior was found buried with a bronze bull's head staff capped by prominent horns, which were likely a symbol of his power and authority.”

The mirror found in the grave. (

University of Cincinnati

)Jack Davis, co-discoverer of the tomb and the University of Cincinnati's Carl W. Blegen chair in Greek archaeology, told EurekAlert!:

The mirror found in the grave. (

University of Cincinnati

)Jack Davis, co-discoverer of the tomb and the University of Cincinnati's Carl W. Blegen chair in Greek archaeology, told EurekAlert!:

An ivory comb which was found in the grave last year. (

Department of Classics/University of Cincinnati

)Davis told the New York Times that they are uncertain if the warrior was buried by Minoans or Mycenaeans who had adopted elements of Minoan culture. He said, “Whoever they are, they are the people introducing Minoan ways to the mainland and forging Mycenaean culture. They were probably dressing like Minoans and building their houses according to styles used on Crete, using Minoan building techniques.”

An ivory comb which was found in the grave last year. (

Department of Classics/University of Cincinnati

)Davis told the New York Times that they are uncertain if the warrior was buried by Minoans or Mycenaeans who had adopted elements of Minoan culture. He said, “Whoever they are, they are the people introducing Minoan ways to the mainland and forging Mycenaean culture. They were probably dressing like Minoans and building their houses according to styles used on Crete, using Minoan building techniques.”

Photo of Nestor’s Palace taken in 2010. (

Public Domain

)The University of Cincinnati’s team's findings from the "Griffin Warrior" grave will be revealed on Thursday, October 6, 2016 at The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Greece.

Photo of Nestor’s Palace taken in 2010. (

Public Domain

)The University of Cincinnati’s team's findings from the "Griffin Warrior" grave will be revealed on Thursday, October 6, 2016 at The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Greece.

Top Image: One of the gold rings recovered from the tomb of the Griffin Warrior. Source: Chronis Papanikolopoulos/University of Cincinnati

By Alicia McDermott

The story behind four magnificent ancient Greek gold signet rings is finally coming to light. One year after they were found in the grave of a Bronze Age Greek warrior, the rings are now taking center stage for both their craftsmanship and the tales that accompany their designs. The researchers studying the artifacts say that they are some of the best examples of Mycenaean-Minoan cultural transfer and early Greek society.

EurekAlert! reports that the rings were crafted with multiple sheets of gold by a highly skilled person. The researchers were astounded by the individual’s abilities in making the rings. As Shari Stocker, co-discoverer of the tomb and a senior research associate in the University of Cincinnati's Department of Classics, said, “They're carving these before the microscope and electric tools. This is exquisite workmanship for something so tiny and old and really shows the skill of Minoan craftsmen.”

The images depicted on the rings show highly detailed Minoan iconography. One ring depicts the iconic Minoan scene of leaping bull. Interestingly, the others all show female figures as the main characters. One of these is an image of a probable goddess holding a staff with two birds accompanying here on a mountain.

A ring showing a bull which was found in the tomb of the Griffin Warrior. (

Jennifer Stephens/University of Cincinnati

)Another ring shows five women around a shrine by the water. According to Eurekalert! this is the largest known gold signet ring from the Aegean world. The last of the four rings depicts a woman making a bull’s horn offering to a goddess. The goddess in the image is seated on a throne and holding a mirror.

A ring showing a bull which was found in the tomb of the Griffin Warrior. (

Jennifer Stephens/University of Cincinnati

)Another ring shows five women around a shrine by the water. According to Eurekalert! this is the largest known gold signet ring from the Aegean world. The last of the four rings depicts a woman making a bull’s horn offering to a goddess. The goddess in the image is seated on a throne and holding a mirror.At first, it was believed that the rings and some of the other artifacts showing Minoan themes were loot from a raid of Crete. However, other grave goods which can be linked to the images shown on the rings suggested to the researchers that they were something more than simple loot.

3,500-Year-Old Unplundered Warrior Tomb with Huge Treasure Hoard found in Greece The Woman Behind the Man: Celtic Warrior Scathach, Teacher of WarriorsApril Holloway discussed some of the other artifacts found last year in the tomb of the so-called “Griffin Warrior.” Apart of his weapons - a bronze sword with a gold and ivory handle and a gold-hilted dagger, the archaeologists found the four gold rings and “an ornate string of pearls, 50 Minoan seal stones carved with imagery of goddesses, silver vases, gold cups, a bronze mirror, ivory combs, an ivory plaque carved with a griffin [from which the tomb received its name], and Minoan-style gold jewelry decorated with figures of deities, animals, and floral motifs.”

Specifically, one can see similarities between the mirror which was found with the warrior’s skeleton and that held by the goddess in the fourth ring. The sacred Minoan symbol of the bull, which EurekAlert! points out is also seen in Mycenaean imagery, is depicted in the rings with the bull-leaping scene and the bull horn offering. The researchers also told EurekAlert! that “it is no coincidence that the Griffin Warrior was found buried with a bronze bull's head staff capped by prominent horns, which were likely a symbol of his power and authority.”

The mirror found in the grave. (

University of Cincinnati

)Jack Davis, co-discoverer of the tomb and the University of Cincinnati's Carl W. Blegen chair in Greek archaeology, told EurekAlert!:

The mirror found in the grave. (

University of Cincinnati

)Jack Davis, co-discoverer of the tomb and the University of Cincinnati's Carl W. Blegen chair in Greek archaeology, told EurekAlert!:“People have suggested that the findings in the grave are treasure, like Blackbeard's treasure, that was just buried along with the dead as impressive contraband. We think that already in this period the people on the mainland already understood much of the religious iconography on these rings, and they were already buying into religious concepts on the island of Crete. This isn't just loot […] it may be loot, but they're specifically selecting loot that transmits messages that are understandable to them.”

An ivory comb which was found in the grave last year. (

Department of Classics/University of Cincinnati

)Davis told the New York Times that they are uncertain if the warrior was buried by Minoans or Mycenaeans who had adopted elements of Minoan culture. He said, “Whoever they are, they are the people introducing Minoan ways to the mainland and forging Mycenaean culture. They were probably dressing like Minoans and building their houses according to styles used on Crete, using Minoan building techniques.”

An ivory comb which was found in the grave last year. (

Department of Classics/University of Cincinnati

)Davis told the New York Times that they are uncertain if the warrior was buried by Minoans or Mycenaeans who had adopted elements of Minoan culture. He said, “Whoever they are, they are the people introducing Minoan ways to the mainland and forging Mycenaean culture. They were probably dressing like Minoans and building their houses according to styles used on Crete, using Minoan building techniques.” Photo of Nestor’s Palace taken in 2010. (

Public Domain

)The University of Cincinnati’s team's findings from the "Griffin Warrior" grave will be revealed on Thursday, October 6, 2016 at The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Greece.

Photo of Nestor’s Palace taken in 2010. (

Public Domain

)The University of Cincinnati’s team's findings from the "Griffin Warrior" grave will be revealed on Thursday, October 6, 2016 at The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Greece.Top Image: One of the gold rings recovered from the tomb of the Griffin Warrior. Source: Chronis Papanikolopoulos/University of Cincinnati

By Alicia McDermott

Published on October 15, 2016 03:00

October 14, 2016

Shakespeare: 7 burning questions about his life

History Extra

The Cobbe portrait, which dates from c1610. This image’s “provenance and claim to be painted from life make a compelling case” for it being an accurate likeness of William Shakespeare, says Paul Edmondson. © Getty

The Cobbe portrait, which dates from c1610. This image’s “provenance and claim to be painted from life make a compelling case” for it being an accurate likeness of William Shakespeare, says Paul Edmondson. © Getty

1) How do we know when he was born?It seems that England’s greatest poet first appeared on the world’s stage on the feast day of England’s patron saint: St George’s Day, Sunday 23 April 1564.

The parish register of Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon records Shakespeare’s baptism on 26 April. According to the Book of Common Prayer, babies had to be baptised either on the next saint’s day after their birth or on the following Sunday. In baby Shakespeare’s case, the next saint’s day was St Mark’s Day, the stolen patron saint of Venice, just two days after his birth. However, Elizabethan folk superstition considered this day to be unlucky, so Shakespeare was baptised after morning or evening prayer on the following day.

For corroborative evidence that Shakespeare was born on 23 April we can look to his monument on the north chancel wall of Holy Trinity Church. This tells us that he died on 23 April 1616, aged 53 – that is at the beginning of his 53rd year. Hence the assumption that he was born and died on the same date.

Shakespeare’s baptismal entry tells us that he is “Gulielmus filius Johannes Shakespeare”: William, the son of John Shakespeare. Only one person of that name lived in the town.

The master bedroom of the house now presented as Shakespeare’s Birthplace was upstairs, overlooking the street – the same room that people have been visiting in homage to Shakespeare since the 18th century.

William Shakespeare was born on the site of this Stratford-upon-Avon building on St George’s Day, 1564. © Alamy

On John’s death in 1601, William inherited the whole of his estate (John had left no will). William allowed his sister, Joan Hart, and her family to live in part of the building (as her descendants did until 1806) and leased another part to become a pub, the Swan and Maidenhead.

The house today is a Victorian renovation of the site and buildings purchased by public subscription in 1847. The Birthplace and four other houses associated with Shakespeare’s life are cared for and conserved by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

2) Where did young Shakespeare learn to read and write?From the ages of 8 to 15, William Shakespeare would have found himself at Stratford-upon-Avon’s grammar school, which had been established under Edward VI to offer a free education to all of the town’s boys.

Founded in 1553 and based on Humanist ideals, Tudor grammar schools were a key element of the government’s stated aim of ensuring that “good literature and discipline might be diffused and propagated throughout all parts of our kingdom, as wherein the best government and administration of affairs consists”.

Shakespeare the schoolboy would have done his studies using a hornbook like this. © Topfoto

These were establishments that took education very seriously indeed. Shakespeare would have gone to school six days a week throughout the year, starting at 6am in the summer and 7am in winter, and staying until dusk (though there were half days on Thursdays and Saturdays). The major Christian festivals provided the few annual holidays.

There was little respite, even in the playground, where the boys were expected to talk to each other in Latin. The emphasis of the whole educational enterprise, in light of the teachings of the 16th-century Dutch scholar Desiderius Erasmus (1469–1536), was on the development of eloquence in speech and writing. A key textbook was William Lily’s Short Introduction of Grammar (1540), through which Shakespeare became familiar with a vast range of rhetorical devices.

The curriculum was highly demanding. The pupils studied Terence, Virgil, Tully, Sallust, Palingenius, Mantuanus, Cicero, Susenbrotus, Erasmus, Quintilian, Horace, Juvenal and Ovid in their original Latin. The latter’s Metamorphoses seems to have been Shakespeare’s favourite book from his school days, and he alluded to it many times in his work. The only writing in Greek to feature on the syllabus was the New Testament. Shakespeare’s grammar-school education is writ large across the whole body of his work. Above all, it taught him eloquence. As an education it was rigorous but limited and did not, for example, include numeracy.

3) Was he trapped in a loveless marriage?Questions about Shakespeare’s marriage and sexuality have divided generations of scholars and critics, and continue to do so.

When he was just 18, William married Anne or Agnes Hathaway (those first names were interchangeable). She was 26 and already pregnant. It has been estimated that around a quarter of late 16th-century women were pregnant before marriage.

Another illuminating statistic has been deduced by local historian Jeanne Jones from records curated by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Between 1570 and 1630 the average age for men to marry in Stratford-upon-Avon was 24. In that 60-year period, and out of 106 cases, there were only three men who married under the age of 20. Of those three, Shakespeare was the youngest and the only one whose wife was already pregnant. They had three children: Susanna (born 1582) and then boy-and-girl twins Hamnet and Judith (born 1585; Hamnet died in 1596).

We don’t know what Anne Shakespeare looked like, but here is an 18th-century artist’s impression. © Topfoto

But were William and Anne happily married? Katherine Duncan-Jones thinks not. In her Ungentle Shakespeare: Scenes from His Life (2001), she presents a Shakespeare who is trapped in his marriage. In Shakespeare’s Wife (2007), Germaine Greer describes the Shakespeares’ relationship as “a demanding and difficult way of life”. Certainly Shakespeare spent long periods of time in London, but that does not mean that he never saw his wife and children. Townsmen frequently travelled between Stratford-upon-Avon and London. The commute took three days by horseback.

Some commentators have pounced upon Shakespeare’s decision to leave Anne his “second best bed with the furniture” to question the state of his marriage. True, this bequest could have been a put-down. But it could also have been a romantic souvenir, or even, perhaps, a codified permit for Anne to remain resident in the family home, New Place.

Most of the speculation on Shakespeare’s sexuality has been based on his works – for example, the same-sex relationships in his plays. Evidence from his life reveals little. In fact, the only surviving contemporary anecdote of Shakespeare’s personal life is to be found in the diary of John Manningham, a trainee lawyer at Middle Temple. The diary relates how Shakespeare arranged to meet a woman with his fellow actor Richard Burbage, yet got there early to have sex with her before Burbage arrived: “Shakespeare caused return to be made that William the Conqueror was before Richard the Third.”

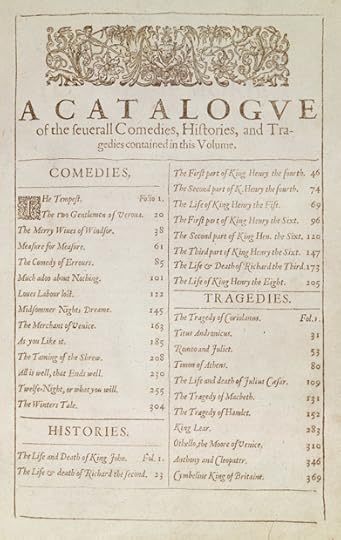

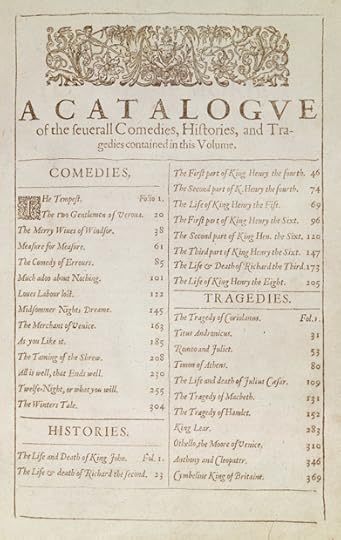

4) Of the numerous portraits of Shakespeare, which is the most accurate?Two images are widely accepted as being accurate depictions of Shakespeare, both of them posthumous: the engraving by the artist Martin Droeshout on the title-page of Master William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies of 1623, and the memorial bust in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon. This was installed some time between 1616, when Shakespeare died, and 1623, when it is first mentioned in Leonard Digges’s commendatory verse in a collected edition of Shakespeare’s work.

Shakespeare’s memorial bust in Stratford-upon-Avon’s Holy Trinity Church. © Alamy

It is possible that both the engraving and the bust were approved by Shakespeare’s widow, family and friends. The playwright Ben Jonson, in his verse printed opposite the engraving, describes it as a good likeness. The bust was made by Gerard Janssen who, in 1614, had also carved the Stratford-upon-Avon tomb effigy for Shakespeare’s friend John Coombe. Janssen’s workshop was in Southwark, near the Globe, so he too probably knew what Shakespeare looked like.

Two portraits of Shakespeare have good provenance and may have been painted from life. One is the Chandos portrait; the other is the Cobbe portrait, which won the support of the world’s leading Shakespeare scholar, Stanley Wells, in 2009.

It has been suggested that the Chandos portrait was painted by John Taylor (an actor from Shakespeare’s period), and was bequeathed to William Davenant, who liked to say he was Shakespeare’s illegitimate son. From here it eventually came into the possession of the Duke of Chandos.

The Chandos portrait may have been painted from life, perhaps by the actor John Taylor. © National Portrait Gallery

The Cobbe portrait passed through the descendants of Shakespeare’s only known literary patron, Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton. It spawned a succession of near-contemporary copies, the majority of which independently identify the sitter as Shakespeare.

The Cobbe portrait has compositional similarities to the Droeshout engraving and may have been its source, possibly through one of the early copies. X-ray analysis has shown that the earliest of these copies is the one now in the possession of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

The Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC has another early copy but does not accept that the sitter is Shakespeare. Shakespeare scholar Katherine Duncan-Jones is among those who have suggested that the portrait represents Sir Thomas Overbury, based on a perceived visual resemblance. Yet none of the many versions and copies of the Cobbe portrait has ever carried an Overbury identification.

What’s more, research at Cambridge University has established that the Cobbe portrait and the undoubted Overbury portrait are unrelated and unlikely to depict the same sitter.

Of all the portraits that might represent Shakespeare, the Cobbe portrait is the most intimate and its provenance and claim to be painted from life make a compelling case.

5) How did a humble writer grow so rich?Shakespeare’s will includes numerous bequests that show that he died a wealthy man. But he cannot have owed his riches simply to his plays. A theatre company would pay a freelance writer a few pounds for a new play, but that wasn’t enough to support and sustain a wife and family.

A writer could boost his income by acting as well – and Shakespeare, Ben Jonson (early in his career) and a handful of others appear to have done just that. Yet, all the same, none of the other playwrights of the period were able to invest in the way Shakespeare did.

Shakespeare was wealthy because he was, from 1594, a shareholder in the theatre company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, in which he was also the leading dramatist. Their patron was the lord chamberlain and they performed at court as well as at the Inns of Court, for which they were paid handsomely.

A c1600 portrait of Shakespeare’s benefactor Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton. © Bridgeman Art Library

Shakespeare was rich enough to buy a house in 1597, which it has been estimated probably cost him around £120. In 1599, he invested in a tripartite lease on the new Globe Theatre. This meant he would receive a share of the box-office takings which, partly because of the popularity of his plays, were high.

He carried on investing heavily in Stratford-upon-Avon. He bought a massive 107 acres of land for £320 in 1602. Only three years later, he spent £440 on a 50 per cent share in the annual tithes payable to the church. This brought him back around £60 a year. In 1613 he bought a gatehouse at Blackfriars for £140.

A story from William Davenant first published in Nicholas Rowe’s biographical account of 1709 suggests that Henry Wriothesley, the Earl of Southampton, gave Shakespeare £1,000 “to enable him to go through with a purchase which he heard he had a mind to”. We’ll probably never know whether he did or not, but it would explain how Shakespeare could afford the shares in the Lord Chamberlain’s Men and how he was able to buy his grand residence, New Place. And all this at a time when a local schoolmaster’s salary was £20 a year.

6) Where did Shakespeare call home?When he was first married, Shakespeare would have had little choice but to live in the family home on Henley Street, Stratford-upon-Avon. He saved money by lodging in London at various places including (in order of residence): the parishes of St Giles Cripplegate; St Helen’s Bishopgate (where he was fined for defaulting on his taxes in 1597 and 1598); St Saviour’s near the Clink, Southwark; and with the Mountjoy family on the corner of Monkswell and Silver Streets, again in the Cripplegate ward.

The site that was occupied by Shakespeare’s New Place until 1759. © Alamy

Shakespeare’s family home from 1597 was New Place, the largest house in the centre of Stratford-upon-Avon. The theatres were closed during Lent and Advent, which would have given him plenty of time to spend at home with his family and to get some writing done in relative peace and quiet.

Between 2010 and 2013, the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust commissioned an archaeological dig of the site (New Place was demolished in 1759), which confirmed it to be a grand manor house, designed for someone of considerable means and social status.

Shakespeare was a commuter who lodged in London and whose grandest living space was in Stratford-upon-Avon.

7) Did he agonise over his plays or dash them off?Defining the way in which Shakespeare went about his work is no easy task because canons of literary work develop over time, as do an author’s mode of writing. What complicates matters is the fact that much of Shakespeare’s writings were published after his death. The Sonnets, a few occasional poems and about half of his plays first appeared during his lifetime. The rest (with the exception of Pericles and The Two Noble Kinsmen) appeared for the first time in a collected edition of his work in 1623.

In 1986, The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works attempted to cast some light on the issue by putting forward two of the most radical theories to emerge in the past 30 years. The first was that Shakespeare regularly revised what he wrote because of practical theatrical considerations. The second suggested that he collaborated on several plays, most significantly at the beginning and end of his career.

A catalogue page from a 1623 listing of all the plays of William Shakespeare. © Getty

Collaboration was absolutely a standard practice among playwrights of Shakespeare’s time. In 2013 Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen published William Shakespeare and Others: Collaborative Plays, a collection of little-known works in which Shakespeare may or may not have had a hand. There are also some apparently lost plays including Love’s Labour’s Won and Cardenio.

Collaboration alone should be enough to put paid to any theory that suggests the plays were the handiwork of a lone aristocrat or an alternative single author operating undercover. The way in which the plays are written shows that Shakespeare had a profound knowledge of theatrical practice and knew the actors for whom he was writing.

He didn’t dash off his plays, as the film Shakespeare in Love might like us to believe. Instead, he adapted the sources and stories on which he based his work, reading extensively before putting quill to paper.

Dr Paul Edmondson is head of research and knowledge, the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

The Cobbe portrait, which dates from c1610. This image’s “provenance and claim to be painted from life make a compelling case” for it being an accurate likeness of William Shakespeare, says Paul Edmondson. © Getty

The Cobbe portrait, which dates from c1610. This image’s “provenance and claim to be painted from life make a compelling case” for it being an accurate likeness of William Shakespeare, says Paul Edmondson. © Getty 1) How do we know when he was born?It seems that England’s greatest poet first appeared on the world’s stage on the feast day of England’s patron saint: St George’s Day, Sunday 23 April 1564.

The parish register of Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon records Shakespeare’s baptism on 26 April. According to the Book of Common Prayer, babies had to be baptised either on the next saint’s day after their birth or on the following Sunday. In baby Shakespeare’s case, the next saint’s day was St Mark’s Day, the stolen patron saint of Venice, just two days after his birth. However, Elizabethan folk superstition considered this day to be unlucky, so Shakespeare was baptised after morning or evening prayer on the following day.

For corroborative evidence that Shakespeare was born on 23 April we can look to his monument on the north chancel wall of Holy Trinity Church. This tells us that he died on 23 April 1616, aged 53 – that is at the beginning of his 53rd year. Hence the assumption that he was born and died on the same date.

Shakespeare’s baptismal entry tells us that he is “Gulielmus filius Johannes Shakespeare”: William, the son of John Shakespeare. Only one person of that name lived in the town.

The master bedroom of the house now presented as Shakespeare’s Birthplace was upstairs, overlooking the street – the same room that people have been visiting in homage to Shakespeare since the 18th century.

William Shakespeare was born on the site of this Stratford-upon-Avon building on St George’s Day, 1564. © Alamy

On John’s death in 1601, William inherited the whole of his estate (John had left no will). William allowed his sister, Joan Hart, and her family to live in part of the building (as her descendants did until 1806) and leased another part to become a pub, the Swan and Maidenhead.

The house today is a Victorian renovation of the site and buildings purchased by public subscription in 1847. The Birthplace and four other houses associated with Shakespeare’s life are cared for and conserved by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

2) Where did young Shakespeare learn to read and write?From the ages of 8 to 15, William Shakespeare would have found himself at Stratford-upon-Avon’s grammar school, which had been established under Edward VI to offer a free education to all of the town’s boys.

Founded in 1553 and based on Humanist ideals, Tudor grammar schools were a key element of the government’s stated aim of ensuring that “good literature and discipline might be diffused and propagated throughout all parts of our kingdom, as wherein the best government and administration of affairs consists”.

Shakespeare the schoolboy would have done his studies using a hornbook like this. © Topfoto

These were establishments that took education very seriously indeed. Shakespeare would have gone to school six days a week throughout the year, starting at 6am in the summer and 7am in winter, and staying until dusk (though there were half days on Thursdays and Saturdays). The major Christian festivals provided the few annual holidays.

There was little respite, even in the playground, where the boys were expected to talk to each other in Latin. The emphasis of the whole educational enterprise, in light of the teachings of the 16th-century Dutch scholar Desiderius Erasmus (1469–1536), was on the development of eloquence in speech and writing. A key textbook was William Lily’s Short Introduction of Grammar (1540), through which Shakespeare became familiar with a vast range of rhetorical devices.

The curriculum was highly demanding. The pupils studied Terence, Virgil, Tully, Sallust, Palingenius, Mantuanus, Cicero, Susenbrotus, Erasmus, Quintilian, Horace, Juvenal and Ovid in their original Latin. The latter’s Metamorphoses seems to have been Shakespeare’s favourite book from his school days, and he alluded to it many times in his work. The only writing in Greek to feature on the syllabus was the New Testament. Shakespeare’s grammar-school education is writ large across the whole body of his work. Above all, it taught him eloquence. As an education it was rigorous but limited and did not, for example, include numeracy.

3) Was he trapped in a loveless marriage?Questions about Shakespeare’s marriage and sexuality have divided generations of scholars and critics, and continue to do so.

When he was just 18, William married Anne or Agnes Hathaway (those first names were interchangeable). She was 26 and already pregnant. It has been estimated that around a quarter of late 16th-century women were pregnant before marriage.

Another illuminating statistic has been deduced by local historian Jeanne Jones from records curated by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Between 1570 and 1630 the average age for men to marry in Stratford-upon-Avon was 24. In that 60-year period, and out of 106 cases, there were only three men who married under the age of 20. Of those three, Shakespeare was the youngest and the only one whose wife was already pregnant. They had three children: Susanna (born 1582) and then boy-and-girl twins Hamnet and Judith (born 1585; Hamnet died in 1596).

We don’t know what Anne Shakespeare looked like, but here is an 18th-century artist’s impression. © Topfoto

But were William and Anne happily married? Katherine Duncan-Jones thinks not. In her Ungentle Shakespeare: Scenes from His Life (2001), she presents a Shakespeare who is trapped in his marriage. In Shakespeare’s Wife (2007), Germaine Greer describes the Shakespeares’ relationship as “a demanding and difficult way of life”. Certainly Shakespeare spent long periods of time in London, but that does not mean that he never saw his wife and children. Townsmen frequently travelled between Stratford-upon-Avon and London. The commute took three days by horseback.

Some commentators have pounced upon Shakespeare’s decision to leave Anne his “second best bed with the furniture” to question the state of his marriage. True, this bequest could have been a put-down. But it could also have been a romantic souvenir, or even, perhaps, a codified permit for Anne to remain resident in the family home, New Place.

Most of the speculation on Shakespeare’s sexuality has been based on his works – for example, the same-sex relationships in his plays. Evidence from his life reveals little. In fact, the only surviving contemporary anecdote of Shakespeare’s personal life is to be found in the diary of John Manningham, a trainee lawyer at Middle Temple. The diary relates how Shakespeare arranged to meet a woman with his fellow actor Richard Burbage, yet got there early to have sex with her before Burbage arrived: “Shakespeare caused return to be made that William the Conqueror was before Richard the Third.”

4) Of the numerous portraits of Shakespeare, which is the most accurate?Two images are widely accepted as being accurate depictions of Shakespeare, both of them posthumous: the engraving by the artist Martin Droeshout on the title-page of Master William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies of 1623, and the memorial bust in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon. This was installed some time between 1616, when Shakespeare died, and 1623, when it is first mentioned in Leonard Digges’s commendatory verse in a collected edition of Shakespeare’s work.

Shakespeare’s memorial bust in Stratford-upon-Avon’s Holy Trinity Church. © Alamy

It is possible that both the engraving and the bust were approved by Shakespeare’s widow, family and friends. The playwright Ben Jonson, in his verse printed opposite the engraving, describes it as a good likeness. The bust was made by Gerard Janssen who, in 1614, had also carved the Stratford-upon-Avon tomb effigy for Shakespeare’s friend John Coombe. Janssen’s workshop was in Southwark, near the Globe, so he too probably knew what Shakespeare looked like.

Two portraits of Shakespeare have good provenance and may have been painted from life. One is the Chandos portrait; the other is the Cobbe portrait, which won the support of the world’s leading Shakespeare scholar, Stanley Wells, in 2009.

It has been suggested that the Chandos portrait was painted by John Taylor (an actor from Shakespeare’s period), and was bequeathed to William Davenant, who liked to say he was Shakespeare’s illegitimate son. From here it eventually came into the possession of the Duke of Chandos.

The Chandos portrait may have been painted from life, perhaps by the actor John Taylor. © National Portrait Gallery

The Cobbe portrait passed through the descendants of Shakespeare’s only known literary patron, Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton. It spawned a succession of near-contemporary copies, the majority of which independently identify the sitter as Shakespeare.

The Cobbe portrait has compositional similarities to the Droeshout engraving and may have been its source, possibly through one of the early copies. X-ray analysis has shown that the earliest of these copies is the one now in the possession of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

The Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC has another early copy but does not accept that the sitter is Shakespeare. Shakespeare scholar Katherine Duncan-Jones is among those who have suggested that the portrait represents Sir Thomas Overbury, based on a perceived visual resemblance. Yet none of the many versions and copies of the Cobbe portrait has ever carried an Overbury identification.

What’s more, research at Cambridge University has established that the Cobbe portrait and the undoubted Overbury portrait are unrelated and unlikely to depict the same sitter.

Of all the portraits that might represent Shakespeare, the Cobbe portrait is the most intimate and its provenance and claim to be painted from life make a compelling case.

5) How did a humble writer grow so rich?Shakespeare’s will includes numerous bequests that show that he died a wealthy man. But he cannot have owed his riches simply to his plays. A theatre company would pay a freelance writer a few pounds for a new play, but that wasn’t enough to support and sustain a wife and family.

A writer could boost his income by acting as well – and Shakespeare, Ben Jonson (early in his career) and a handful of others appear to have done just that. Yet, all the same, none of the other playwrights of the period were able to invest in the way Shakespeare did.

Shakespeare was wealthy because he was, from 1594, a shareholder in the theatre company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, in which he was also the leading dramatist. Their patron was the lord chamberlain and they performed at court as well as at the Inns of Court, for which they were paid handsomely.

A c1600 portrait of Shakespeare’s benefactor Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton. © Bridgeman Art Library

Shakespeare was rich enough to buy a house in 1597, which it has been estimated probably cost him around £120. In 1599, he invested in a tripartite lease on the new Globe Theatre. This meant he would receive a share of the box-office takings which, partly because of the popularity of his plays, were high.

He carried on investing heavily in Stratford-upon-Avon. He bought a massive 107 acres of land for £320 in 1602. Only three years later, he spent £440 on a 50 per cent share in the annual tithes payable to the church. This brought him back around £60 a year. In 1613 he bought a gatehouse at Blackfriars for £140.