MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 80

October 8, 2016

7 surprising Ancient Rome facts

History Extra

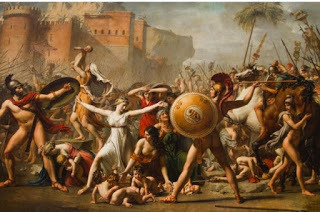

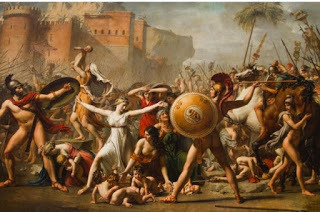

The Intervention of the Sabine Women, painting by the French painter Jacques-Louis David, 1799. Musee Du Louvre, Paris, France. (Photo by Exotica.im/UIG via Getty Images)

The Intervention of the Sabine Women, painting by the French painter Jacques-Louis David, 1799. Musee Du Louvre, Paris, France. (Photo by Exotica.im/UIG via Getty Images)

1) The Roman’s couldn’t decide on their originsThe legend of Romulus and Remus tells the story of twin brothers raised by wolves who become the founding fathers of Rome.

The boys’ mother, Rhea Silvia, had been forced into becoming a Vestal Virgin (priestesses who attended to the sacred fire of Vesta) by the usurper Amulius. Rhea Silvia then had a miraculous conception, either by the god Mars or by Hercules (there are variations on the myth). When Amulius heard of this, he ordered the infant twins to be taken to the river Tiber where they were left to die.

In the event they were saved and nourished by a she-wolf and later taken in by a shepherd and his family until they grew to manhood, unaware of their origins. Eventually they heard the story of the treachery of Amulius, after which they confronted and killed the tyrant. Then, because Romulus wanted to found their new city on the Palatine Hill and Remus preferred the Aventine Hill, they agreed to see a soothsayer. However, each brother interpreted the results in his own favour. This led to a fight in which Romulus killed Remus, and that founded the new city of Rome in 753 BC.

What’s stranger still is that there was a later ‘founding of Rome’ story. Written around the 8th century BC, Homer’s Iliad recalls the story of the Trojan War but Rome's origins are linked to the second telling of this same story by another giant of ancient writing, Virgil, in his book The Aeneid. As well as enhancing Homer’s earlier story, The Aeneid also postdates the tale of Romulus and Remus. This is important because, according to Virgil, Troy’s population wasn’t completely destroyed. Instead, a prince called Aeneas escaped with a small group of Trojans and sailed the Mediterranean until he found an area he liked the look of. So this ancient and noble civilisation transplanted itself in Italy and founded Rome.

Both tales are revealing. The first shows us that the Romans were explaining where their predatory and argumentative attitudes came from: they are all the children of wolves. The second story was created at the time of emperors, so there is a demand for respectability and heritage. The Trojan War was as famous then as now, so why not connect this new empire to a very old and familiar tale?

A stone plate of Rome's founders, Romulus and Remus, suckled by a female wolf, seen at the National Historical Museum, Sofia, Bulgaria, in April 2011. (Photo by Nikolay Doychinov/AFP/Getty Images)

A stone plate of Rome's founders, Romulus and Remus, suckled by a female wolf, seen at the National Historical Museum, Sofia, Bulgaria, in April 2011. (Photo by Nikolay Doychinov/AFP/Getty Images)

2) Rome was a bad neighbourBy the 5th century BC, Rome was one of many tiny states on the Italian peninsula. If you were a gambler in 480 BC you would probably have put your money on an eventual Etruscan empire. The Etruscsns were after all the biggest power on the Italian peninsula at that time. Over the centuries the realm had grown substantially, and while Rome’s central and southern towns had thrown off Etruscan dominance, it was still the largest power in an area populated by numerous other Italic peoples, many of their names barely remembered by history.

It's a forgotten fact that the Romans had to conquer the rest of Italy, and one of the first tribes to fall was the Sabines. According to a famous legend, oft repeated in ancient texts (and a popular subject with Renaissance artists), the Romans abducted the Sabine women for breeding purposes, in order to increase the population of Rome. Whether this was true or not is impossible to say, but the Romans were consistently avid slavers, and what is uncontested is that by the dawn of the 4th century BC the Sabine kingdom had been absorbed into Roman lands.

10 things you didn't know about the Romans Romans and Italians were never the same thing. It’s just that the Roman city state was more aggressive, with a better army, or luckier than the other kingdoms of Italy. It wouldn’t have taken much to snuff out Rome at this time, in which case this article you are reading could have been about the empire of the Frentani, yet another Italic people then located on the east coast of the peninsula.

Although geographically close to each other, these realms were so diverse that they didn’t even speak the same language. Etruscan is still, frustratingly, one of the languages that has yet to be satisfactorily translated. The Sabines, similarly, were not Latin speakers. The Hellenic colonies in the toe of Italy spoke Greek. To these people the Romans were not fellow countrymen carrying out a hostile takeover that was always inevitable and perhaps a tiny bit yearned for. Instead, this was an invasion by a foreign nation of terrifying men who spoke an alien tongue.

3) The first sacking of Rome nearly finished the cityThe traditional date for the first sacking of Rome is 390 BC, but modern historians agree that a date of 387 BC is more likely. When a tribe of Gauls, called the Senones, came over the Alps into Italy in search of lands to settle, the first people they met were the Etruscans. Unsurprisingly, they didn’t want to cede any of their lands to these foreigners, so they asked for military assistance from the rising military power of Rome.

Rome gathered together a large army and sent it north to help its neighbour fight this alien threat. Meanwhile, the diplomacy wasn’t going well. Even in this ancient era there was a general rule that ambassadors and messengers were to be left unharmed, but one of the Roman diplomats killed one of the Gaulish chieftains. The Gauls (not unreasonably) demanded that the perpetrators be brought to justice, and some in Rome agreed. However, the Roman masses did not, and this provocation led to the meeting of both sides at the Allia River, both ready for battle.

The Romans had amassed a mighty army; the Senones had an army of about half the size. However, as battle ensued, the Gauls shattered the two flanks of the Roman army and surrounded the elite central force. Now outmanoeuvred and tired from fighting, this Roman army was completely annihilated. The road to Rome was open to the Gauls, who were led by the terrifying figure of Brennus.

What happened next is described in a series of fables and legends, none of which dispute that the Gauls fell on Rome and destroyed much of it. Indeed, they did such a good job that contemporary histories of Rome prior to and during this period are sketchy because of the scale of destruction.

Why the Gauls didn’t settle in the conquered city is unknown. One Roman source claims they were chased away by another Roman army, but this was most likely an explanation created to give the Romans something of a face-saving ending to an otherwise total defeat. What is more probable is that like many northern armies that had tried to settle around Rome, the Gauls found the climate distinctly unhealthy, and it’s probable that disease spread through Brennus’ men. Either way, the Gauls retreated into the mists of legend and hearsay.

Rome was so completely destroyed that there was serious debate about re-founding the capital in the nearby (and completely forgotten town) of Veii. Instead, the Senate decided to stay and authorised the building of the first major stone walls to defend the city.

Battle between Romans and Gauls. (Photo by Leemage/UIG via Getty Images)

4) The battle of Adrianople was the beginning of the endBy the 4th century AD, Germanic invasions were starting to become a serious problem for the Roman empire. It was during this period that a number of new groups began to appear in the Roman hinterlands. Some of these people were known as the Goths.

Initially the Goths agreed to join the empire, settle as farmers and, in essence, merge with the local population. But the Goths were hardly welcomed with open arms, and heavy-handedness by local Roman governors led to Goth resentments and uprisings. Exactly who was to blame for the resulting conflict is hard to say.

The Gothic War lasted from AD 376 to 382. This new wave of barbarians was running amok, and there were frequent clashes with the forces of the western Roman emperor Gratian. However, it was the eastern Roman emperor Valens who went personally to deal with them.

The two sides met near Adrianople (modern day Edirne in Turkey). The Roman writer Ammianus Marcellinus claims that Valens had around 25,000 men against a horde of 80,000 (as is often the case with ancient texts, these numbers are probably exaggerated).

The Romans had marched for seven or eight hours over rough terrain; they were tired and out of formation when they arrived in front of the Gothic army. The 4thcentury legions were, by now, clad in mail armour and had large round shields, all of which were an added burden under the hot August sun. Some of the Roman army attacked without orders and were easily pushed back. The Roman soldier’s rash actions meant he had no option but to engage in battle.

The Gothic force’s centre was a defensive circle of wagons, which the Romans failed to penetrate. However, while the Romans were busy attacking this defensive position, the Goth cavalry crept in from the sides and outflanked Valens’ forces. The heavily armoured Romans were not as nimble or agile as the Goths, and while they managed to break out from the enveloping moves by the Goth cavalry, they were now fighting in small groups and not as a unified army. In the ensuing chaos most of the Roman troops were slaughtered, including the emperor, Valens.

Valens’ successor, Theodosius, was forced to turn the Goths from enemies into allies, but at the cost of land. This was a turning point from which the Roman empire never recovered.

5) The capital of the late Roman empire wasn’t RomeThe Roman empire got its name from its founding city. Therefore, when Rome finally fell forever from the power of the emperors, the change in circumstances must mark the end of the Roman empire, right?

However, while it is often recognised that in the late Roman era Constantinople was the more important city, what almost nobody realises is that by the early 5th century AD, the western Roman emperors had moved the capital from the ancient and illustrious city of Rome.

By AD 402 the terrible emperor Honorius felt that Rome was no longer defensible and decided to move the capital to Ravenna. This was a large town with a population of around 50,000, and had been part of the empire since the 2nd century BC. Despite receiving regular investment funds (emperor Trajan built a massive aqueduct), it was never one of the most important urban areas of the empire and had been in decline in recent times. However, Ravenna had a large and easily defendable port and became the base for Rome’s naval fleet in the Adriatic Sea. As it was also surrounded by marshland, it was regarded as a place of safety, with guaranteed connections to the stronger eastern empire.

The move to Ravenna was an admission by Honorius that Rome could no longer hold back the barbarian invasions. It remained the capital of the empire until its eventual fall in AD 476. It was recaptured by the eastern Roman empire in AD 584 and was part of those lands until 751.

6) The last western emperor shared a name with the founder of RomeRomulus Augustus, better known as Romulus Augustulus, ‘little Augustus’, was a boy who ‘ruled’ for about 10 months from AD 475–476. He was little more than a figurehead for his father Orestes, a Roman aristocrat (of Germanic ancestry), who had manoeuvred his way into a position of power in the court in Ravenna.

By now the title of western Roman emperor was virtually meaningless. The only remaining areas of the empire were the Italian peninsula, along with some fragmentary lands in Gaul, Spain and Croatia. Barbarian groups had already sacked Rome twice, and any real power was held by these tribes and not by the Roman court in Ravenna.

Little is known about the teenage Romulus Augustulus. Coins were minted with his face, but he led no armies and no monuments were built for him. He was an irrelevance.

The 8 bloodiest Roman emperors The Germanic leader Odoacer knew this and, in AD 476, marched on Ravenna. Odoacer had been leading the foederati, the barbarian contingents that by now made up almost the entire ‘Roman’ army. He had all the real power and he knew it.

On arriving in Ravenna and finding no resistance, Odoacer met face-to-face with the so-called emperor, Romulus Augustus. However, the chronicles then say that Odoacer, “taking pity on his youth”, spared Romulus' life. Odoacer carried out no bloody coup, nor did he take the imperial title, because he knew that it had ceased to have any significance. Instead, he recast himself as the first king of Italy, after which he granted Romulus an annual pension and sent him to live with relatives in southern Italy.

Odoacer then got on with reshaping Italy, not in the mould of the old empire, but in the form of a new kingdom. The transformation was long overdue, and as a result, Odoacer was able to bring more stability to the time of his reign than the previous emperors had managed during the past 80 years.

The last western Roman emperor did not go down in a battle, nor did he commit suicide. He was deposed and sent home like a naughty schoolboy. This was final humiliation for a title that, from Scotland to Iraq, had once put fear in men’s hearts.

c475 AD, last Roman emperor of the west, Romulus Augustulus. (Photo by Spencer Arnold/Getty Images)

7) When the Roman empire ended is up for debateWhat determines the final demise of the empire is notoriously difficult. The easiest date to use is the fall of Rome… but which one? 410 doesn’t mark the end of the list of western Roman emperors, nor does 455. The other problem is that while Rome was the cradle of the empire, by the 5th century it was neither the most important city (Constantinople), nor the capital of the Western Roman Empire (Ravenna).

The second date that could be used is 476, when Romulus Augutulus was deposed. Again, this doesn’t work because the eastern Roman emperor was still the most powerful person in the world (except for the emperor of China). His empire might have become known as the Byzantine empire, and its inhabitants might have begun speaking Greek, but they considered themselves to be as Roman as Julius Caesar – right up until the bitter end – an ending that happened twice.

The Byzantine empire was the victim of the Fourth Crusade and was conquered in 1204. This was the end of the empire then, surely?

However, just a couple of generations later, it threw off its western overlords, and the emperors returned. These were to last until the Ottoman conquest of 1453 (where the last eastern Roman emperor, unlike the last western one, did go down in a blaze of glory on the city’s battlements).

So does 1453 count as the end of the empire? This is an even harder date to use because the 15th-century world was very different to that of the Roman empire at its peak. Worse still, since Charlemagne was crowned emperor of the Romans in 800, there had been a number of Germanic rulers who would, by the Middle Ages, claim to be ‘holy Roman emperors’. They were no such thing, but the title was still in play.

And yet, still later dates could be used: when Constantinople fell to the Ottomans, two very different dynasties took up the title of Roman emperor and Caesar. Firstly the Ottoman sultan took the title because he had just conquered the old eastern capital. Secondly, as Constantinople had been the capital of Orthodox Christianity, the Russian rulers, as defenders of the Orthodox faith, took the title Caesar (‘tsar’ in Russian).

None of these dates are satisfactory, so the last fact is really a question. Which date would you choose?

Jem Duducu is the author of The Romans in 100 Facts (Amberley Publishing, 2015).

The Intervention of the Sabine Women, painting by the French painter Jacques-Louis David, 1799. Musee Du Louvre, Paris, France. (Photo by Exotica.im/UIG via Getty Images)

The Intervention of the Sabine Women, painting by the French painter Jacques-Louis David, 1799. Musee Du Louvre, Paris, France. (Photo by Exotica.im/UIG via Getty Images) 1) The Roman’s couldn’t decide on their originsThe legend of Romulus and Remus tells the story of twin brothers raised by wolves who become the founding fathers of Rome.

The boys’ mother, Rhea Silvia, had been forced into becoming a Vestal Virgin (priestesses who attended to the sacred fire of Vesta) by the usurper Amulius. Rhea Silvia then had a miraculous conception, either by the god Mars or by Hercules (there are variations on the myth). When Amulius heard of this, he ordered the infant twins to be taken to the river Tiber where they were left to die.

In the event they were saved and nourished by a she-wolf and later taken in by a shepherd and his family until they grew to manhood, unaware of their origins. Eventually they heard the story of the treachery of Amulius, after which they confronted and killed the tyrant. Then, because Romulus wanted to found their new city on the Palatine Hill and Remus preferred the Aventine Hill, they agreed to see a soothsayer. However, each brother interpreted the results in his own favour. This led to a fight in which Romulus killed Remus, and that founded the new city of Rome in 753 BC.

What’s stranger still is that there was a later ‘founding of Rome’ story. Written around the 8th century BC, Homer’s Iliad recalls the story of the Trojan War but Rome's origins are linked to the second telling of this same story by another giant of ancient writing, Virgil, in his book The Aeneid. As well as enhancing Homer’s earlier story, The Aeneid also postdates the tale of Romulus and Remus. This is important because, according to Virgil, Troy’s population wasn’t completely destroyed. Instead, a prince called Aeneas escaped with a small group of Trojans and sailed the Mediterranean until he found an area he liked the look of. So this ancient and noble civilisation transplanted itself in Italy and founded Rome.

Both tales are revealing. The first shows us that the Romans were explaining where their predatory and argumentative attitudes came from: they are all the children of wolves. The second story was created at the time of emperors, so there is a demand for respectability and heritage. The Trojan War was as famous then as now, so why not connect this new empire to a very old and familiar tale?

A stone plate of Rome's founders, Romulus and Remus, suckled by a female wolf, seen at the National Historical Museum, Sofia, Bulgaria, in April 2011. (Photo by Nikolay Doychinov/AFP/Getty Images)

A stone plate of Rome's founders, Romulus and Remus, suckled by a female wolf, seen at the National Historical Museum, Sofia, Bulgaria, in April 2011. (Photo by Nikolay Doychinov/AFP/Getty Images)2) Rome was a bad neighbourBy the 5th century BC, Rome was one of many tiny states on the Italian peninsula. If you were a gambler in 480 BC you would probably have put your money on an eventual Etruscan empire. The Etruscsns were after all the biggest power on the Italian peninsula at that time. Over the centuries the realm had grown substantially, and while Rome’s central and southern towns had thrown off Etruscan dominance, it was still the largest power in an area populated by numerous other Italic peoples, many of their names barely remembered by history.

It's a forgotten fact that the Romans had to conquer the rest of Italy, and one of the first tribes to fall was the Sabines. According to a famous legend, oft repeated in ancient texts (and a popular subject with Renaissance artists), the Romans abducted the Sabine women for breeding purposes, in order to increase the population of Rome. Whether this was true or not is impossible to say, but the Romans were consistently avid slavers, and what is uncontested is that by the dawn of the 4th century BC the Sabine kingdom had been absorbed into Roman lands.

10 things you didn't know about the Romans Romans and Italians were never the same thing. It’s just that the Roman city state was more aggressive, with a better army, or luckier than the other kingdoms of Italy. It wouldn’t have taken much to snuff out Rome at this time, in which case this article you are reading could have been about the empire of the Frentani, yet another Italic people then located on the east coast of the peninsula.

Although geographically close to each other, these realms were so diverse that they didn’t even speak the same language. Etruscan is still, frustratingly, one of the languages that has yet to be satisfactorily translated. The Sabines, similarly, were not Latin speakers. The Hellenic colonies in the toe of Italy spoke Greek. To these people the Romans were not fellow countrymen carrying out a hostile takeover that was always inevitable and perhaps a tiny bit yearned for. Instead, this was an invasion by a foreign nation of terrifying men who spoke an alien tongue.

3) The first sacking of Rome nearly finished the cityThe traditional date for the first sacking of Rome is 390 BC, but modern historians agree that a date of 387 BC is more likely. When a tribe of Gauls, called the Senones, came over the Alps into Italy in search of lands to settle, the first people they met were the Etruscans. Unsurprisingly, they didn’t want to cede any of their lands to these foreigners, so they asked for military assistance from the rising military power of Rome.

Rome gathered together a large army and sent it north to help its neighbour fight this alien threat. Meanwhile, the diplomacy wasn’t going well. Even in this ancient era there was a general rule that ambassadors and messengers were to be left unharmed, but one of the Roman diplomats killed one of the Gaulish chieftains. The Gauls (not unreasonably) demanded that the perpetrators be brought to justice, and some in Rome agreed. However, the Roman masses did not, and this provocation led to the meeting of both sides at the Allia River, both ready for battle.

The Romans had amassed a mighty army; the Senones had an army of about half the size. However, as battle ensued, the Gauls shattered the two flanks of the Roman army and surrounded the elite central force. Now outmanoeuvred and tired from fighting, this Roman army was completely annihilated. The road to Rome was open to the Gauls, who were led by the terrifying figure of Brennus.

What happened next is described in a series of fables and legends, none of which dispute that the Gauls fell on Rome and destroyed much of it. Indeed, they did such a good job that contemporary histories of Rome prior to and during this period are sketchy because of the scale of destruction.

Why the Gauls didn’t settle in the conquered city is unknown. One Roman source claims they were chased away by another Roman army, but this was most likely an explanation created to give the Romans something of a face-saving ending to an otherwise total defeat. What is more probable is that like many northern armies that had tried to settle around Rome, the Gauls found the climate distinctly unhealthy, and it’s probable that disease spread through Brennus’ men. Either way, the Gauls retreated into the mists of legend and hearsay.

Rome was so completely destroyed that there was serious debate about re-founding the capital in the nearby (and completely forgotten town) of Veii. Instead, the Senate decided to stay and authorised the building of the first major stone walls to defend the city.

Battle between Romans and Gauls. (Photo by Leemage/UIG via Getty Images)

4) The battle of Adrianople was the beginning of the endBy the 4th century AD, Germanic invasions were starting to become a serious problem for the Roman empire. It was during this period that a number of new groups began to appear in the Roman hinterlands. Some of these people were known as the Goths.

Initially the Goths agreed to join the empire, settle as farmers and, in essence, merge with the local population. But the Goths were hardly welcomed with open arms, and heavy-handedness by local Roman governors led to Goth resentments and uprisings. Exactly who was to blame for the resulting conflict is hard to say.

The Gothic War lasted from AD 376 to 382. This new wave of barbarians was running amok, and there were frequent clashes with the forces of the western Roman emperor Gratian. However, it was the eastern Roman emperor Valens who went personally to deal with them.

The two sides met near Adrianople (modern day Edirne in Turkey). The Roman writer Ammianus Marcellinus claims that Valens had around 25,000 men against a horde of 80,000 (as is often the case with ancient texts, these numbers are probably exaggerated).

The Romans had marched for seven or eight hours over rough terrain; they were tired and out of formation when they arrived in front of the Gothic army. The 4thcentury legions were, by now, clad in mail armour and had large round shields, all of which were an added burden under the hot August sun. Some of the Roman army attacked without orders and were easily pushed back. The Roman soldier’s rash actions meant he had no option but to engage in battle.

The Gothic force’s centre was a defensive circle of wagons, which the Romans failed to penetrate. However, while the Romans were busy attacking this defensive position, the Goth cavalry crept in from the sides and outflanked Valens’ forces. The heavily armoured Romans were not as nimble or agile as the Goths, and while they managed to break out from the enveloping moves by the Goth cavalry, they were now fighting in small groups and not as a unified army. In the ensuing chaos most of the Roman troops were slaughtered, including the emperor, Valens.

Valens’ successor, Theodosius, was forced to turn the Goths from enemies into allies, but at the cost of land. This was a turning point from which the Roman empire never recovered.

5) The capital of the late Roman empire wasn’t RomeThe Roman empire got its name from its founding city. Therefore, when Rome finally fell forever from the power of the emperors, the change in circumstances must mark the end of the Roman empire, right?

However, while it is often recognised that in the late Roman era Constantinople was the more important city, what almost nobody realises is that by the early 5th century AD, the western Roman emperors had moved the capital from the ancient and illustrious city of Rome.

By AD 402 the terrible emperor Honorius felt that Rome was no longer defensible and decided to move the capital to Ravenna. This was a large town with a population of around 50,000, and had been part of the empire since the 2nd century BC. Despite receiving regular investment funds (emperor Trajan built a massive aqueduct), it was never one of the most important urban areas of the empire and had been in decline in recent times. However, Ravenna had a large and easily defendable port and became the base for Rome’s naval fleet in the Adriatic Sea. As it was also surrounded by marshland, it was regarded as a place of safety, with guaranteed connections to the stronger eastern empire.

The move to Ravenna was an admission by Honorius that Rome could no longer hold back the barbarian invasions. It remained the capital of the empire until its eventual fall in AD 476. It was recaptured by the eastern Roman empire in AD 584 and was part of those lands until 751.

6) The last western emperor shared a name with the founder of RomeRomulus Augustus, better known as Romulus Augustulus, ‘little Augustus’, was a boy who ‘ruled’ for about 10 months from AD 475–476. He was little more than a figurehead for his father Orestes, a Roman aristocrat (of Germanic ancestry), who had manoeuvred his way into a position of power in the court in Ravenna.

By now the title of western Roman emperor was virtually meaningless. The only remaining areas of the empire were the Italian peninsula, along with some fragmentary lands in Gaul, Spain and Croatia. Barbarian groups had already sacked Rome twice, and any real power was held by these tribes and not by the Roman court in Ravenna.

Little is known about the teenage Romulus Augustulus. Coins were minted with his face, but he led no armies and no monuments were built for him. He was an irrelevance.

The 8 bloodiest Roman emperors The Germanic leader Odoacer knew this and, in AD 476, marched on Ravenna. Odoacer had been leading the foederati, the barbarian contingents that by now made up almost the entire ‘Roman’ army. He had all the real power and he knew it.

On arriving in Ravenna and finding no resistance, Odoacer met face-to-face with the so-called emperor, Romulus Augustus. However, the chronicles then say that Odoacer, “taking pity on his youth”, spared Romulus' life. Odoacer carried out no bloody coup, nor did he take the imperial title, because he knew that it had ceased to have any significance. Instead, he recast himself as the first king of Italy, after which he granted Romulus an annual pension and sent him to live with relatives in southern Italy.

Odoacer then got on with reshaping Italy, not in the mould of the old empire, but in the form of a new kingdom. The transformation was long overdue, and as a result, Odoacer was able to bring more stability to the time of his reign than the previous emperors had managed during the past 80 years.

The last western Roman emperor did not go down in a battle, nor did he commit suicide. He was deposed and sent home like a naughty schoolboy. This was final humiliation for a title that, from Scotland to Iraq, had once put fear in men’s hearts.

c475 AD, last Roman emperor of the west, Romulus Augustulus. (Photo by Spencer Arnold/Getty Images)

7) When the Roman empire ended is up for debateWhat determines the final demise of the empire is notoriously difficult. The easiest date to use is the fall of Rome… but which one? 410 doesn’t mark the end of the list of western Roman emperors, nor does 455. The other problem is that while Rome was the cradle of the empire, by the 5th century it was neither the most important city (Constantinople), nor the capital of the Western Roman Empire (Ravenna).

The second date that could be used is 476, when Romulus Augutulus was deposed. Again, this doesn’t work because the eastern Roman emperor was still the most powerful person in the world (except for the emperor of China). His empire might have become known as the Byzantine empire, and its inhabitants might have begun speaking Greek, but they considered themselves to be as Roman as Julius Caesar – right up until the bitter end – an ending that happened twice.

The Byzantine empire was the victim of the Fourth Crusade and was conquered in 1204. This was the end of the empire then, surely?

However, just a couple of generations later, it threw off its western overlords, and the emperors returned. These were to last until the Ottoman conquest of 1453 (where the last eastern Roman emperor, unlike the last western one, did go down in a blaze of glory on the city’s battlements).

So does 1453 count as the end of the empire? This is an even harder date to use because the 15th-century world was very different to that of the Roman empire at its peak. Worse still, since Charlemagne was crowned emperor of the Romans in 800, there had been a number of Germanic rulers who would, by the Middle Ages, claim to be ‘holy Roman emperors’. They were no such thing, but the title was still in play.

And yet, still later dates could be used: when Constantinople fell to the Ottomans, two very different dynasties took up the title of Roman emperor and Caesar. Firstly the Ottoman sultan took the title because he had just conquered the old eastern capital. Secondly, as Constantinople had been the capital of Orthodox Christianity, the Russian rulers, as defenders of the Orthodox faith, took the title Caesar (‘tsar’ in Russian).

None of these dates are satisfactory, so the last fact is really a question. Which date would you choose?

Jem Duducu is the author of The Romans in 100 Facts (Amberley Publishing, 2015).

Published on October 08, 2016 03:00

October 7, 2016

Discovery of a Medieval Well Raises New Questions About Nazis and a Polish Castle

Ancient Origins

A team of Polish researchers has discovered a well which dates back to medieval times. It is located in the famous castle of Książ in Wałbrzych, Lower Silesia, Poland. Although they previously believed that it may have been a part of a system of tunnels created by Nazis, the real story of the well may be even more fascinating.

According to Gazeta Wyborcza, the well was found under the floor of a tower discovered last July. It is quadrilateral and without any visible damages. One side of the well is 2.5 meters (8.2 ft.) wide, and it is about 50 meters (164 ft.) deep. The tower which covered the mysterious well was discovered while cleaning the road area near the castle. It is dated back to the 18th century and was depicted on drawings of the castle. The well was examined with a camera, which confirmed that the discovery is very rare and will bring much more information after it is further explored by the researchers.

A photo taken inside of the well at Książ Castle in Wałbrzych, Poland. (

ZWIK Łódź

)However, the future works will be demanding, and it's necessary to apply more analysis before the team will be able to continue. During the first exploration, they found chisels, but it is unknown what period they come from. It is possible that the medieval well was closed after the18th century, which makes the discovery extremely interesting.

A photo taken inside of the well at Książ Castle in Wałbrzych, Poland. (

ZWIK Łódź

)However, the future works will be demanding, and it's necessary to apply more analysis before the team will be able to continue. During the first exploration, they found chisels, but it is unknown what period they come from. It is possible that the medieval well was closed after the18th century, which makes the discovery extremely interesting.

Polish Pyramids: Ruins of Megalithic Tombs from the Time of Stonehenge Discovered in PolandArchaeologists unearth Vampire burial in Poland The Castle of Książ is one of the most iconic in Poland. Originally built in the early medieval period, it was destroyed in 1263. The new castle was created at the end of the 13th century, and through history it had many different owners, including the famous Hochberg family. During World War II, the castle was held by the Nazis. Nowadays, Książ Castle is considered one of the pearls of the region. In this area there are more stories about hidden chests, trains, and chambers where Nazis could have hidden treasures than places for them to actually have hidden it.

A decorated room inside Książ Castle. (

Dariusz Cierpiał

/

CC BY SA 3.0

)Essentially, every Polish city which belonged to the Germans in the past has stories related to lost loot. One of the most interesting tales is about the precious treasures of Daisy of Pless and her possible lover Emperor Wilhelm II. However, it's only a legend. The treasures from this story were stolen by the Russian army, and any that survived are currently exhibited in a museum.

A decorated room inside Książ Castle. (

Dariusz Cierpiał

/

CC BY SA 3.0

)Essentially, every Polish city which belonged to the Germans in the past has stories related to lost loot. One of the most interesting tales is about the precious treasures of Daisy of Pless and her possible lover Emperor Wilhelm II. However, it's only a legend. The treasures from this story were stolen by the Russian army, and any that survived are currently exhibited in a museum.

Wałbrzych, like many other places in Silesia, still hides many secrets. Recently, another group of researchers was trying to find the legendary Nazi train that is said to be filled with treasures. As April Holloway wrote on November 9, 2015:

Hand-colored photograph of the original Amber Room, 1931. (

Public Domain

)

Hand-colored photograph of the original Amber Room, 1931. (

Public Domain

)

Holloway continued:

By Natalia Klimczak

A team of Polish researchers has discovered a well which dates back to medieval times. It is located in the famous castle of Książ in Wałbrzych, Lower Silesia, Poland. Although they previously believed that it may have been a part of a system of tunnels created by Nazis, the real story of the well may be even more fascinating.

According to Gazeta Wyborcza, the well was found under the floor of a tower discovered last July. It is quadrilateral and without any visible damages. One side of the well is 2.5 meters (8.2 ft.) wide, and it is about 50 meters (164 ft.) deep. The tower which covered the mysterious well was discovered while cleaning the road area near the castle. It is dated back to the 18th century and was depicted on drawings of the castle. The well was examined with a camera, which confirmed that the discovery is very rare and will bring much more information after it is further explored by the researchers.

A photo taken inside of the well at Książ Castle in Wałbrzych, Poland. (

ZWIK Łódź

)However, the future works will be demanding, and it's necessary to apply more analysis before the team will be able to continue. During the first exploration, they found chisels, but it is unknown what period they come from. It is possible that the medieval well was closed after the18th century, which makes the discovery extremely interesting.

A photo taken inside of the well at Książ Castle in Wałbrzych, Poland. (

ZWIK Łódź

)However, the future works will be demanding, and it's necessary to apply more analysis before the team will be able to continue. During the first exploration, they found chisels, but it is unknown what period they come from. It is possible that the medieval well was closed after the18th century, which makes the discovery extremely interesting.Polish Pyramids: Ruins of Megalithic Tombs from the Time of Stonehenge Discovered in PolandArchaeologists unearth Vampire burial in Poland The Castle of Książ is one of the most iconic in Poland. Originally built in the early medieval period, it was destroyed in 1263. The new castle was created at the end of the 13th century, and through history it had many different owners, including the famous Hochberg family. During World War II, the castle was held by the Nazis. Nowadays, Książ Castle is considered one of the pearls of the region. In this area there are more stories about hidden chests, trains, and chambers where Nazis could have hidden treasures than places for them to actually have hidden it.

A decorated room inside Książ Castle. (

Dariusz Cierpiał

/

CC BY SA 3.0

)Essentially, every Polish city which belonged to the Germans in the past has stories related to lost loot. One of the most interesting tales is about the precious treasures of Daisy of Pless and her possible lover Emperor Wilhelm II. However, it's only a legend. The treasures from this story were stolen by the Russian army, and any that survived are currently exhibited in a museum.

A decorated room inside Książ Castle. (

Dariusz Cierpiał

/

CC BY SA 3.0

)Essentially, every Polish city which belonged to the Germans in the past has stories related to lost loot. One of the most interesting tales is about the precious treasures of Daisy of Pless and her possible lover Emperor Wilhelm II. However, it's only a legend. The treasures from this story were stolen by the Russian army, and any that survived are currently exhibited in a museum.Wałbrzych, like many other places in Silesia, still hides many secrets. Recently, another group of researchers was trying to find the legendary Nazi train that is said to be filled with treasures. As April Holloway wrote on November 9, 2015:

''Headlines were made around the world as treasure hunters identified a legendary Nazi train packed with weapons, gold, money, and archives hidden in a long-forgotten tunnel in the Polish mountains. It is believed that the train may also contain the long-lost Amber Room of Charlottenburg Palace, an early 1700s room crafted from amber, gold, and precious jewels, estimated to now be worth $385 million.”Sigrid the Haughty, Queen Consort of Four Countries and Owner of a Strong PersonalityTimeless Stories Built on Grains of Salt: Examining the Masterpieces within a Polish Salt Mine

Hand-colored photograph of the original Amber Room, 1931. (

Public Domain

)

Hand-colored photograph of the original Amber Room, 1931. (

Public Domain

)Holloway continued:

“Poland’s Culture Ministry announced that the location of the Nazi train was revealed to Piotr Koper of Poland and Andreas Richter of Germany through a deathbed confession. The Telegraph reported that two treasure-hunters found the 100-meter-long armored train and immediately submitted a claim to the Polish government – under Polish law those who find treasures can keep 10 per cent of the value of their find. The Polish Ministry has confirmed the location of the train using ground-penetrating radar. The train is said to be located in an underground tunnel constructed by the Nazis along a 4km stretch of track on the Wroclaw-Walbrzych line. However, its exact location is being kept hidden, not least because it is believed to be booby trapped or mined and will need to be investigated through a careful operation conducted by the Army, Police, and Fire Brigade.''Researchers still haven’t been lucky enough to find the legendary train and its rich contents. However, they have already announced that the search will continue.

Top Image: Książ castle in Wałbrzych, Lower Silesia, Poland. (Piotr Bieniecki/ CC BY SA 4.0) Detail: A photo taken inside the newly discovered well. (ZWIK Łódź)

By Natalia Klimczak

Published on October 07, 2016 03:00

October 6, 2016

A Polish Stonehenge? Discovery of New Burial Mounds May Rewrite History

Ancient Origins

A group of previously unknown burial mounds has been discovered near Czaplinek in north-western Poland. The most interesting feature found so far is a stone ring, which is shaped similar to the world-famous site of Stonehenge. The complex sheds a new light on the history of these lands.

The team of Polish archaeologists from the Koszalin city museum unearthed a complex in an area previously known to have had an Iron Age site. According to RMF24.pl, the team of researchers found an urn burial with cremated remains inside. Apart from this, several precious artifacts were discovered inside the urn, including a bronze buckle, bone pin, and a clay spindle whorl - which allowed them to conclude that the burial contains a woman’s ashes.

The first artifacts from the site. (

Muzeum w Koszalinie

)The site also contains burial mounds which were enclosed with stone rings. The researchers claim that the rings may be similar to the sequence of stones used in Stonehenge – with larger stones connected with a row of smaller ones.

The first artifacts from the site. (

Muzeum w Koszalinie

)The site also contains burial mounds which were enclosed with stone rings. The researchers claim that the rings may be similar to the sequence of stones used in Stonehenge – with larger stones connected with a row of smaller ones.

Polish Pyramids: Ruins of Megalithic Tombs from the Time of Stonehenge Discovered in PolandMysterious medieval fortifications buried in Poland detected with advanced imaging technologyThe large stones were overturned through the ages, but it is still possible to find their original location. Archaeologists were able to identify the layout of the stone ring with the large stone in its center. The scientists believe that it was a place for religious ceremonies and ritual burials. The mounds were dated back to a period between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD.

The mound under investigation near Czaplinek. (

Muzeum w Koszalinie

)The complex near Czaplinek is one of a few big complexes of mounds and megaliths in Poland. One famous complex is located in Odry, a small village in Pomerania in the north of Poland. This location became famous with the discovery of the second biggest site of stone circles in Europe. It is also known to be the home of at least 600 Neolithic burials. The site was discovered in 1915 by Paul Stephan, who identified various stellar alignments on the assumption that the construction dates back to the 8th century BC.

The mound under investigation near Czaplinek. (

Muzeum w Koszalinie

)The complex near Czaplinek is one of a few big complexes of mounds and megaliths in Poland. One famous complex is located in Odry, a small village in Pomerania in the north of Poland. This location became famous with the discovery of the second biggest site of stone circles in Europe. It is also known to be the home of at least 600 Neolithic burials. The site was discovered in 1915 by Paul Stephan, who identified various stellar alignments on the assumption that the construction dates back to the 8th century BC.

Archaeologists still debate the origins of the huge burial center amongst the Odry stone rings. It is difficult to agree upon one explanation for the stone circles’ roots. It is also almost impossible to find out how old the constructions discovered in Odry really are. It is known that the area was settled by the Goths at one point in time, but the earlier history of the region has never been confirmed.

Long Hidden Scythian Treasure Site Located at Ceremonial Spring in PolandThe Nazi Temple of Pomerania: Exploring the Mysterious Odry Stone CirclesFor many centuries, these kinds of places were damaged in Poland. The worst devastation took place during the 19th century, when people destroyed old kurgans (prehistoric burial mounds or barrows), stone circles, and other Neolithic constructions to prepare farmers’ fields. Thus, it is not surprising that most of the Neolithic sites that have been found are located in the forest. It could be said that the caring tree roots saved them and protected them over the centuries.

This is another discovery of megalithic tombs made in Poland this year. During the last few years, every few months has brought a new discovery. For example, Natalia Klimczak reported on March 2, 2016 for Ancient Origins that more than a dozen monumental megalithic tombs were discovered in Western Pomerania in Poland. Because of the enormous character of the structures, they are often called the ‘Polish pyramids.’ The site is located near Dolice, Western Pomerania. She writes:

An example of a Funnel Beaker Culture Dolmen (single-chamber megalithic tomb) in Lancken-Granitz, Germany. (Skäpperöd/

CC BY SA 3.0

)In that discovery “the mounds contain single burials. According to the researchers, the people who were buried in the tombs were important elders of the tribe. Other information may be available after the researchers summarize more data and explore the sites further. Until now, the research has been based on non-invasive methods.”

An example of a Funnel Beaker Culture Dolmen (single-chamber megalithic tomb) in Lancken-Granitz, Germany. (Skäpperöd/

CC BY SA 3.0

)In that discovery “the mounds contain single burials. According to the researchers, the people who were buried in the tombs were important elders of the tribe. Other information may be available after the researchers summarize more data and explore the sites further. Until now, the research has been based on non-invasive methods.”

Top Image: Part of the recently discovered site in Czaplinek, Poland. Source: Muzeum w Koszalinie

By Natalia Klimczak

A group of previously unknown burial mounds has been discovered near Czaplinek in north-western Poland. The most interesting feature found so far is a stone ring, which is shaped similar to the world-famous site of Stonehenge. The complex sheds a new light on the history of these lands.

The team of Polish archaeologists from the Koszalin city museum unearthed a complex in an area previously known to have had an Iron Age site. According to RMF24.pl, the team of researchers found an urn burial with cremated remains inside. Apart from this, several precious artifacts were discovered inside the urn, including a bronze buckle, bone pin, and a clay spindle whorl - which allowed them to conclude that the burial contains a woman’s ashes.

The first artifacts from the site. (

Muzeum w Koszalinie

)The site also contains burial mounds which were enclosed with stone rings. The researchers claim that the rings may be similar to the sequence of stones used in Stonehenge – with larger stones connected with a row of smaller ones.

The first artifacts from the site. (

Muzeum w Koszalinie

)The site also contains burial mounds which were enclosed with stone rings. The researchers claim that the rings may be similar to the sequence of stones used in Stonehenge – with larger stones connected with a row of smaller ones.Polish Pyramids: Ruins of Megalithic Tombs from the Time of Stonehenge Discovered in PolandMysterious medieval fortifications buried in Poland detected with advanced imaging technologyThe large stones were overturned through the ages, but it is still possible to find their original location. Archaeologists were able to identify the layout of the stone ring with the large stone in its center. The scientists believe that it was a place for religious ceremonies and ritual burials. The mounds were dated back to a period between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD.

The mound under investigation near Czaplinek. (

Muzeum w Koszalinie

)The complex near Czaplinek is one of a few big complexes of mounds and megaliths in Poland. One famous complex is located in Odry, a small village in Pomerania in the north of Poland. This location became famous with the discovery of the second biggest site of stone circles in Europe. It is also known to be the home of at least 600 Neolithic burials. The site was discovered in 1915 by Paul Stephan, who identified various stellar alignments on the assumption that the construction dates back to the 8th century BC.

The mound under investigation near Czaplinek. (

Muzeum w Koszalinie

)The complex near Czaplinek is one of a few big complexes of mounds and megaliths in Poland. One famous complex is located in Odry, a small village in Pomerania in the north of Poland. This location became famous with the discovery of the second biggest site of stone circles in Europe. It is also known to be the home of at least 600 Neolithic burials. The site was discovered in 1915 by Paul Stephan, who identified various stellar alignments on the assumption that the construction dates back to the 8th century BC.Archaeologists still debate the origins of the huge burial center amongst the Odry stone rings. It is difficult to agree upon one explanation for the stone circles’ roots. It is also almost impossible to find out how old the constructions discovered in Odry really are. It is known that the area was settled by the Goths at one point in time, but the earlier history of the region has never been confirmed.

Long Hidden Scythian Treasure Site Located at Ceremonial Spring in PolandThe Nazi Temple of Pomerania: Exploring the Mysterious Odry Stone CirclesFor many centuries, these kinds of places were damaged in Poland. The worst devastation took place during the 19th century, when people destroyed old kurgans (prehistoric burial mounds or barrows), stone circles, and other Neolithic constructions to prepare farmers’ fields. Thus, it is not surprising that most of the Neolithic sites that have been found are located in the forest. It could be said that the caring tree roots saved them and protected them over the centuries.

This is another discovery of megalithic tombs made in Poland this year. During the last few years, every few months has brought a new discovery. For example, Natalia Klimczak reported on March 2, 2016 for Ancient Origins that more than a dozen monumental megalithic tombs were discovered in Western Pomerania in Poland. Because of the enormous character of the structures, they are often called the ‘Polish pyramids.’ The site is located near Dolice, Western Pomerania. She writes:

“The ground structures were made in a shape of an elongated triangle, surrounded by big stone blocks. The structures stood 3 meters (9.8 feet) tall, and were 150 meters (492.1 feet) long, and 6-15 meters (19.7-49.2 feet) wide. The place where they are located is difficult to examine. The surface is covered by an old forest. On small sites archaeologists have discovered fragments of pottery and other artifacts. The tombs were created by the Funnel Beaker Culture community which lived on the land from the 5th to the 3rd millennium BC.”

An example of a Funnel Beaker Culture Dolmen (single-chamber megalithic tomb) in Lancken-Granitz, Germany. (Skäpperöd/

CC BY SA 3.0

)In that discovery “the mounds contain single burials. According to the researchers, the people who were buried in the tombs were important elders of the tribe. Other information may be available after the researchers summarize more data and explore the sites further. Until now, the research has been based on non-invasive methods.”

An example of a Funnel Beaker Culture Dolmen (single-chamber megalithic tomb) in Lancken-Granitz, Germany. (Skäpperöd/

CC BY SA 3.0

)In that discovery “the mounds contain single burials. According to the researchers, the people who were buried in the tombs were important elders of the tribe. Other information may be available after the researchers summarize more data and explore the sites further. Until now, the research has been based on non-invasive methods.”Top Image: Part of the recently discovered site in Czaplinek, Poland. Source: Muzeum w Koszalinie

By Natalia Klimczak

Published on October 06, 2016 03:00

October 5, 2016

Ancient Rome – 6 burning questions

History Extra

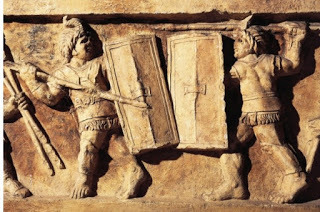

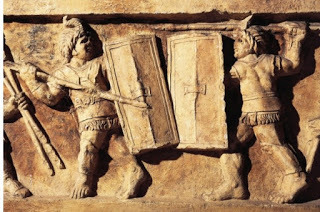

Relief portraying a gladiator fight, 1st century AD. From Preturo, L'Aquila Province. (Photo By DEA /A DAGLI ORTI/De Agostini/Getty Images)

Relief portraying a gladiator fight, 1st century AD. From Preturo, L'Aquila Province. (Photo By DEA /A DAGLI ORTI/De Agostini/Getty Images)

Who founded Ancient Rome?Like all ancient societies, the Romans possessed a heroic foundation story. What made the Romans different, however, is that they created two distinct creation myths for themselves.

In the first it was claimed that they were descended from the royal Trojan refugee Aeneas (himself the son of the goddess Venus). In the second it was stated that the city of Rome was founded by, and ultimately named after, Romulus, son of a union between an earthly princess and the god Mars.

Both myths helped establish the Romans as a divinely chosen people whose ancestry could be traced back to Troy and the Hellenistic world. Roman tradition had Romulus’ foundling city established on the Palatine Hill in what became, for Rome, ‘Year One’ (or 753 BC in the Christian calendar of the West). Archaeological excavation on the hill has found settlement here dating back to at least 1000 BC.

Who ruled in Ancient Rome?Rome made much of the fact that it was a republic, ruled by the people and not by kings.

Rome had overthrown its monarchy in 509 BC, and legislative power was thereafter vested in the people’s assemblies: political power in the senate, and military power with two annually elected magistrates known as consuls.

The acronym ‘SPQR’, for Senatus Populusque Romanus (‘the Senate and People of Rome’) was proudly emblazoned across inscriptions and military standards throughout the Mediterranean – a reminder that Rome’s people (theoretically) had the last word.

By the late 1st century BC, the combination of power-hungry politicians and large overseas territories resulted in the breakdown of traditional systems of government. Even after the rise of the emperors – kings in all but name, who ‘guided’ the Roman political system in the 1st century AD – ‘SPQR’ continued to be used in order to sustain the fiction that Rome was a state governed by purely republican principles.

Who were gladiators in ancient Rome?Gladiatorial games were organised by the elite throughout the Roman empire in order to distract the population from the reality of daily life.

Most gladiators were purchased from slave markets, being chosen for their strength, stamina and good looks. Although taken from the lowest elements of society, the gladiator was a breed apart from the ‘normal’ slave or prisoner of war, being well-trained combatants whose one role in life was to fight and occasionally to kill for the amusement of the Roman mob.

Not all those who fought as gladiators were slaves or convicts, however. Some were citizens down on their luck (or heavily in debt) while some, like the emperor Commodus, simply did it for ‘fun’.

Whatever their reasons for ending up in the arena, gladiators were adored by the Roman public for their bravery and spirit. Their images appeared frequently in mosaics, wall paintings and on glassware and pottery.

In Ancient Rome, what was the law of the twelve tables?The Twelve Tables was the primary legislative basis for Rome’s republican constitution, protecting the working classes from arbitrary punishment and excessive treatment by the ruling elite (patricians).

Created around 450 BC, the tables were a code that set out the rights and obligations of the people in areas such as marriage, divorce, burial, inheritance, property and ownership, injury, compensation, debt and slavery.

Key provisions included the establishment of burial grounds outside the limits of the city walls, the control of property if the stakeholder was decreed insane, the continual guardianship of women (passing from father to husband), the treatment of children and of slaves (as property), and the settling of compensation claims for injuries sustained at work.

Although the power of the ruling classes was not really constrained by the plebs, the twelve tables were never repealed – they formed the cornerstone of Roman law until well into the 5th century AD.

What did they eat in Ancient Rome?The Romans ate pretty much everything they could lay their hands on. Meat, especially pork and fish, however, were expensive commodities, and so the bulk of the population survived on cereals (wheat, emmer and barley) mixed with chickpeas, lentils, turnips, lettuce, leek, cabbage and fenugreek.

Olives, grapes, apples, plums and figs provided welcome relief from the traditional forms of thick, cereal-based porridge (tomatoes and potatoes were a much later introduction to the Mediterranean), while milk, cheese, eggs and bread were also daily staples.

The Romans liked to vary their cooking with sweet (honey) and sour (fermented fish) sauces, which often helpfully disguised the taste of rotten meat.

Dining as entertainment was practised within elite society – lavish dinner parties were the ideal way to show off wealth and status. Recipes compiled in the 4th century supply us with details of tasty treats such as pickled sow’s udders and stuffed dormice.

Why did Ancient Rome fall?A whole variety of reasons can be suggested to explain the fall of the Roman Empire in the west: disease, invasion, civil war, social unrest, inflation, economic collapse. In fact all were contributory factors, although key to the collapse of Roman authority was the prolonged period of imperial in-fighting during the 3rd and 4th century.

Conflict between multiple emperors severely weakened the military, eroded the economy and put a huge strain upon local populations. When Germanic migrants arrived, many western landowners threw their support behind the new ‘barbarian’ elite rather than continuing to back the emperor.

Reduced income from the provinces meant that Rome could no longer pay or feed its military and civil administration, making the imperial system of government redundant. The western half of the Roman empire mutated into a variety of discrete kingdoms while the east, which largely avoided both the in-fighting and barbarian migrations, survived until the 15th century.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication. These Q&As were taken from our ‘History Extra explains’ series, which answers burning questions about ancient Rome, the Tudors, ancient Egypt and the First World War.

Relief portraying a gladiator fight, 1st century AD. From Preturo, L'Aquila Province. (Photo By DEA /A DAGLI ORTI/De Agostini/Getty Images)

Relief portraying a gladiator fight, 1st century AD. From Preturo, L'Aquila Province. (Photo By DEA /A DAGLI ORTI/De Agostini/Getty Images) Who founded Ancient Rome?Like all ancient societies, the Romans possessed a heroic foundation story. What made the Romans different, however, is that they created two distinct creation myths for themselves.

In the first it was claimed that they were descended from the royal Trojan refugee Aeneas (himself the son of the goddess Venus). In the second it was stated that the city of Rome was founded by, and ultimately named after, Romulus, son of a union between an earthly princess and the god Mars.

Both myths helped establish the Romans as a divinely chosen people whose ancestry could be traced back to Troy and the Hellenistic world. Roman tradition had Romulus’ foundling city established on the Palatine Hill in what became, for Rome, ‘Year One’ (or 753 BC in the Christian calendar of the West). Archaeological excavation on the hill has found settlement here dating back to at least 1000 BC.

Who ruled in Ancient Rome?Rome made much of the fact that it was a republic, ruled by the people and not by kings.

Rome had overthrown its monarchy in 509 BC, and legislative power was thereafter vested in the people’s assemblies: political power in the senate, and military power with two annually elected magistrates known as consuls.

The acronym ‘SPQR’, for Senatus Populusque Romanus (‘the Senate and People of Rome’) was proudly emblazoned across inscriptions and military standards throughout the Mediterranean – a reminder that Rome’s people (theoretically) had the last word.

By the late 1st century BC, the combination of power-hungry politicians and large overseas territories resulted in the breakdown of traditional systems of government. Even after the rise of the emperors – kings in all but name, who ‘guided’ the Roman political system in the 1st century AD – ‘SPQR’ continued to be used in order to sustain the fiction that Rome was a state governed by purely republican principles.

Who were gladiators in ancient Rome?Gladiatorial games were organised by the elite throughout the Roman empire in order to distract the population from the reality of daily life.

Most gladiators were purchased from slave markets, being chosen for their strength, stamina and good looks. Although taken from the lowest elements of society, the gladiator was a breed apart from the ‘normal’ slave or prisoner of war, being well-trained combatants whose one role in life was to fight and occasionally to kill for the amusement of the Roman mob.

Not all those who fought as gladiators were slaves or convicts, however. Some were citizens down on their luck (or heavily in debt) while some, like the emperor Commodus, simply did it for ‘fun’.

Whatever their reasons for ending up in the arena, gladiators were adored by the Roman public for their bravery and spirit. Their images appeared frequently in mosaics, wall paintings and on glassware and pottery.

In Ancient Rome, what was the law of the twelve tables?The Twelve Tables was the primary legislative basis for Rome’s republican constitution, protecting the working classes from arbitrary punishment and excessive treatment by the ruling elite (patricians).

Created around 450 BC, the tables were a code that set out the rights and obligations of the people in areas such as marriage, divorce, burial, inheritance, property and ownership, injury, compensation, debt and slavery.

Key provisions included the establishment of burial grounds outside the limits of the city walls, the control of property if the stakeholder was decreed insane, the continual guardianship of women (passing from father to husband), the treatment of children and of slaves (as property), and the settling of compensation claims for injuries sustained at work.

Although the power of the ruling classes was not really constrained by the plebs, the twelve tables were never repealed – they formed the cornerstone of Roman law until well into the 5th century AD.

What did they eat in Ancient Rome?The Romans ate pretty much everything they could lay their hands on. Meat, especially pork and fish, however, were expensive commodities, and so the bulk of the population survived on cereals (wheat, emmer and barley) mixed with chickpeas, lentils, turnips, lettuce, leek, cabbage and fenugreek.

Olives, grapes, apples, plums and figs provided welcome relief from the traditional forms of thick, cereal-based porridge (tomatoes and potatoes were a much later introduction to the Mediterranean), while milk, cheese, eggs and bread were also daily staples.

The Romans liked to vary their cooking with sweet (honey) and sour (fermented fish) sauces, which often helpfully disguised the taste of rotten meat.

Dining as entertainment was practised within elite society – lavish dinner parties were the ideal way to show off wealth and status. Recipes compiled in the 4th century supply us with details of tasty treats such as pickled sow’s udders and stuffed dormice.

Why did Ancient Rome fall?A whole variety of reasons can be suggested to explain the fall of the Roman Empire in the west: disease, invasion, civil war, social unrest, inflation, economic collapse. In fact all were contributory factors, although key to the collapse of Roman authority was the prolonged period of imperial in-fighting during the 3rd and 4th century.

Conflict between multiple emperors severely weakened the military, eroded the economy and put a huge strain upon local populations. When Germanic migrants arrived, many western landowners threw their support behind the new ‘barbarian’ elite rather than continuing to back the emperor.

Reduced income from the provinces meant that Rome could no longer pay or feed its military and civil administration, making the imperial system of government redundant. The western half of the Roman empire mutated into a variety of discrete kingdoms while the east, which largely avoided both the in-fighting and barbarian migrations, survived until the 15th century.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication. These Q&As were taken from our ‘History Extra explains’ series, which answers burning questions about ancient Rome, the Tudors, ancient Egypt and the First World War.

Published on October 05, 2016 03:00

October 4, 2016

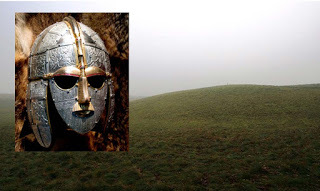

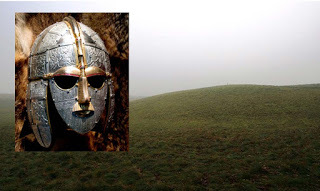

Anglo-Saxon Royal Palace Unearthed Near Famous Burial Site

Ancient Origins

A team of archeologists believe they have unearthed a lost Anglo-Saxon royal palace, located only 6 km (four miles) from the famous Sutton Hoo burial site.

According to BBC, the researchers have been working in the area of Rendlesham, which is located close to the Sutton Hoo burial site, known for its undisturbed ship burial, magnificent Anglo-Saxon helmet, and the hoard of ornate artifacts of outstanding historical and archaeological significance. It is one of the most famous discoveries ever made in Britain.

Replica of Anglo-Saxon mask discovered at Sutton Hoo (

Bill Tyne / Flickr

)The project co-ordinator, Faye Minter, reported that her team discovered the remains of a 23m (75ft) by 9m (30ft) structure, which could have once been a royal hall or palace. She concluded that it was possible that there are other royal burials similar to Sutton Hoo, which was excavated for the first time in 1939 and dated back to the 7th century. It consists of about 20 burial mounds and the excavations revealed many fascinating and impressive treasures. This time the researchers hope to find even more burials, which could have been placed along the River Deben. Ms Minter, of Suffolk County Council's archaeological unit, suggested that the discovered ''palace'' may be the place described by The Venerable Bede dated back to the 8th century.

Replica of Anglo-Saxon mask discovered at Sutton Hoo (

Bill Tyne / Flickr

)The project co-ordinator, Faye Minter, reported that her team discovered the remains of a 23m (75ft) by 9m (30ft) structure, which could have once been a royal hall or palace. She concluded that it was possible that there are other royal burials similar to Sutton Hoo, which was excavated for the first time in 1939 and dated back to the 7th century. It consists of about 20 burial mounds and the excavations revealed many fascinating and impressive treasures. This time the researchers hope to find even more burials, which could have been placed along the River Deben. Ms Minter, of Suffolk County Council's archaeological unit, suggested that the discovered ''palace'' may be the place described by The Venerable Bede dated back to the 8th century.

A burial mound at Sutton Hoo (

public domain

)

A burial mound at Sutton Hoo (

public domain

)

This LIDAR (Light Detection And Ranging) survey shows the core Anglo-Saxon areas at Rendlesham, including the main residence area. Credit: Suffolk Archaeological Service.Until now about 4,000 items, including intricate metalwork, coins and weights, have been found at Rendlesham. However, only about 1,000 of them are Anglo-Saxon. According to Dr Helen Geake of the British Museum the discovery of the palace was an ''incredibly exciting'' moment. The researchers suppose that there may be a few more palaces or halls like this dotted in this area. Those times the king would have toured his kingdom in order to show his power, magnificence, charisma and the reasons to follow him by his people. Therefore, it seems to be logical to have lots of palaces to base himself around the area which belonged to him.

This LIDAR (Light Detection And Ranging) survey shows the core Anglo-Saxon areas at Rendlesham, including the main residence area. Credit: Suffolk Archaeological Service.Until now about 4,000 items, including intricate metalwork, coins and weights, have been found at Rendlesham. However, only about 1,000 of them are Anglo-Saxon. According to Dr Helen Geake of the British Museum the discovery of the palace was an ''incredibly exciting'' moment. The researchers suppose that there may be a few more palaces or halls like this dotted in this area. Those times the king would have toured his kingdom in order to show his power, magnificence, charisma and the reasons to follow him by his people. Therefore, it seems to be logical to have lots of palaces to base himself around the area which belonged to him.

The Great Buckle found at Sutton Hoo (

public domain

)It is another surprising discovery related to Anglo-Saxons. In April 12, 2016, Natalia Klimczak from Ancient Origins reported the surprising discover of cemetery. She wrote:

The Great Buckle found at Sutton Hoo (

public domain

)It is another surprising discovery related to Anglo-Saxons. In April 12, 2016, Natalia Klimczak from Ancient Origins reported the surprising discover of cemetery. She wrote:

''A group of more than 40 skeletons was found during the building of a new toilet for the parishioners of a church in Hildersham, Cambridgeshire, UK. The remains are about 900 years old.

According to the BBC, the burials are dated to the 11th or 12th century. Some of the graves lay 45 cm (18 in) below the path outside the Holy Trinity Church. They were dug into the chalk, with the bodies laid directly in the cavity. Most of the skeletons were of adults, but five of the individuals were children. The researchers examined 19 skeletons dated to the 9th or 10th century, predating the church by several hundred years, but they left 24 graves intact.

The graves are said to be Anglo-Saxon, although Cambridge University Archaeological Unit experts who examined the site dated the bones to the 11th or 12th century. Until the discovery was made, there was no proof for the existence of a cemetery in this area. The researchers believe that the graves belonged to villagers who lived outside the walls of what was probably an Anglo-Saxon church.

During the excavations , the bones were stored in the mortuary at the village undertaker's for the night. After the end of the works, the skeletons were buried in one new grave. A funeral took place just before Christmas 2015, and the toilet was completed soon after.''

Top image: Main: Sutton Hoo burial mound ( public domain ). Inset: Replica of Anglo-Saxon mask discovered at Sutton Hoo ( Bill Tyne / Flickr )

By Natalia Klimzcak

A team of archeologists believe they have unearthed a lost Anglo-Saxon royal palace, located only 6 km (four miles) from the famous Sutton Hoo burial site.

According to BBC, the researchers have been working in the area of Rendlesham, which is located close to the Sutton Hoo burial site, known for its undisturbed ship burial, magnificent Anglo-Saxon helmet, and the hoard of ornate artifacts of outstanding historical and archaeological significance. It is one of the most famous discoveries ever made in Britain.

Replica of Anglo-Saxon mask discovered at Sutton Hoo (

Bill Tyne / Flickr

)The project co-ordinator, Faye Minter, reported that her team discovered the remains of a 23m (75ft) by 9m (30ft) structure, which could have once been a royal hall or palace. She concluded that it was possible that there are other royal burials similar to Sutton Hoo, which was excavated for the first time in 1939 and dated back to the 7th century. It consists of about 20 burial mounds and the excavations revealed many fascinating and impressive treasures. This time the researchers hope to find even more burials, which could have been placed along the River Deben. Ms Minter, of Suffolk County Council's archaeological unit, suggested that the discovered ''palace'' may be the place described by The Venerable Bede dated back to the 8th century.

Replica of Anglo-Saxon mask discovered at Sutton Hoo (

Bill Tyne / Flickr

)The project co-ordinator, Faye Minter, reported that her team discovered the remains of a 23m (75ft) by 9m (30ft) structure, which could have once been a royal hall or palace. She concluded that it was possible that there are other royal burials similar to Sutton Hoo, which was excavated for the first time in 1939 and dated back to the 7th century. It consists of about 20 burial mounds and the excavations revealed many fascinating and impressive treasures. This time the researchers hope to find even more burials, which could have been placed along the River Deben. Ms Minter, of Suffolk County Council's archaeological unit, suggested that the discovered ''palace'' may be the place described by The Venerable Bede dated back to the 8th century. A burial mound at Sutton Hoo (

public domain

)

A burial mound at Sutton Hoo (

public domain

)''We have discovered what we think is a large Anglo Saxon Hall, which could be the palace itself, if you could call it that,” said Faye Minter [via BBC]. “We're convinced we've found a royal settlement of very high status, and I suppose it would be a large hall rather than a palace as it would spring to mind to us."As the researchers announced during the conference in Bury St Edmunds, the remains of the palace cover 120-acre (50 ha) site and were discovered due to the analysis of the aerial photography and geophysical surveys.

This LIDAR (Light Detection And Ranging) survey shows the core Anglo-Saxon areas at Rendlesham, including the main residence area. Credit: Suffolk Archaeological Service.Until now about 4,000 items, including intricate metalwork, coins and weights, have been found at Rendlesham. However, only about 1,000 of them are Anglo-Saxon. According to Dr Helen Geake of the British Museum the discovery of the palace was an ''incredibly exciting'' moment. The researchers suppose that there may be a few more palaces or halls like this dotted in this area. Those times the king would have toured his kingdom in order to show his power, magnificence, charisma and the reasons to follow him by his people. Therefore, it seems to be logical to have lots of palaces to base himself around the area which belonged to him.

This LIDAR (Light Detection And Ranging) survey shows the core Anglo-Saxon areas at Rendlesham, including the main residence area. Credit: Suffolk Archaeological Service.Until now about 4,000 items, including intricate metalwork, coins and weights, have been found at Rendlesham. However, only about 1,000 of them are Anglo-Saxon. According to Dr Helen Geake of the British Museum the discovery of the palace was an ''incredibly exciting'' moment. The researchers suppose that there may be a few more palaces or halls like this dotted in this area. Those times the king would have toured his kingdom in order to show his power, magnificence, charisma and the reasons to follow him by his people. Therefore, it seems to be logical to have lots of palaces to base himself around the area which belonged to him. The Great Buckle found at Sutton Hoo (

public domain

)It is another surprising discovery related to Anglo-Saxons. In April 12, 2016, Natalia Klimczak from Ancient Origins reported the surprising discover of cemetery. She wrote:

The Great Buckle found at Sutton Hoo (

public domain

)It is another surprising discovery related to Anglo-Saxons. In April 12, 2016, Natalia Klimczak from Ancient Origins reported the surprising discover of cemetery. She wrote:''A group of more than 40 skeletons was found during the building of a new toilet for the parishioners of a church in Hildersham, Cambridgeshire, UK. The remains are about 900 years old.