MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 82

September 19, 2016

Mistaken Identity? Mosaic in Israel Purported to Show Alexander the Great, but Some Not So Sure

Ancient Origins

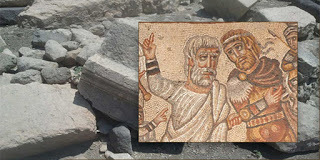

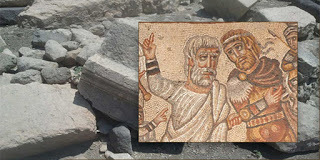

According to NationalGeographic.com, archaeologists have discovered an interesting and unusual mosaic at the Huqoq archaeological site west of the Sea of Galilee. The most recent and most interesting find dates from the 5th century, and shows a king in military attire and a troop of soldiers, offering a calf to a group of white-robed priests. But the meeting is obviously fractious, as the priests are drawing their swords, while the bottom of the scene shows the solders lying defeated and dying.

The scene has been compared to the semi-legendary meeting between Alexander the Great and the Jerusalem priesthood, in the 4th century BC. While other historians have suggested the mosaic represents the attack on Jerusalem by Antiochus VII in the 2nd century BC. But the characters are not named, which is unusual for mosaics in this era, and there are a number of problems with these interpretations. The main problem is that the king is bearded, which Antiochus and Alexander were not. And the meeting between Alexander and the Judaic priesthood was supposed to have been friendly, not antagonistic. And neither Alexander nor Antiochus were defeated, as the bottom of the mosaic appears to show.

Archaeological site of Huqoq, Israel, where the new mosaic has been revealed. (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)

Archaeological site of Huqoq, Israel, where the new mosaic has been revealed. (

CC BY-SA 3.0

) Detail of mosaic. (

Source:

NationalGeographic/Mark Thiessen)Mistaken IdentitySince traditional academia have been unable to satisfactorily decypher what this mosaic represents, perhaps we should rework these interpretations using the new religio-historical framework that has been constructed in 'The King Jesus Trilogy'. This radical new theory, which is fully supported by all the original texts, suggests that the gospel era and story refers to the late AD 60s, and the tragic events of the Jewish Revolt. And if we use this new framework, we can immediately see that this mosaic does not depict Alexander the Great or Antiochus. The classical interpretations are wrong.

Detail of mosaic. (

Source:

NationalGeographic/Mark Thiessen)Mistaken IdentitySince traditional academia have been unable to satisfactorily decypher what this mosaic represents, perhaps we should rework these interpretations using the new religio-historical framework that has been constructed in 'The King Jesus Trilogy'. This radical new theory, which is fully supported by all the original texts, suggests that the gospel era and story refers to the late AD 60s, and the tragic events of the Jewish Revolt. And if we use this new framework, we can immediately see that this mosaic does not depict Alexander the Great or Antiochus. The classical interpretations are wrong.

More intriguingly, this is actually a depiction of an obscure scene from the Talmud, where bar Kamza offers a sacrificial calf on behalf of the Romans, to rabbi Zechariah Abkulas (see Gittin 55-57). This was in about AD 68, just prior to the Jewish Revolt. But bar Kamza was being devious here, because he had cut the calf's lip (you can see the mark on the mosaic), knowing that Zechariah would have to reject the blemished Roman offering - and thereby offend the Romans, and in turn precipitate the Jewish Revolt. This was one of the ways by which the Jewish Revolt was deliberately contrived.

Eden in Egypt – Part 1 The Surprising Links Between Alexander the Great and Christianity Does newly-translated Hebrew text reveal insights into King Solomon’s treasures? So who was this mysterious and largely unknown character called bar Kamza? Well, in actual fact, Kamza is merely a witty hypocorism meaning 'locust'. And there was a royal family in Syria who were similarly disparaged as being locusts, one of whom was Agabus (meaning locust) who appears in Acts of the Apostles (Acts 11:27). This Syrian Agabus in Acts prophesied the great Judaean famine of AD 47 and gave famine relief-money, just as did the more famous Queen Helena. And this confirms that this royal family of 'locusts' was actually the Syrian monarchy of King Abgarus V of Edessa, because he was married to this very same Queen Helena. Yes, the famous 1st century Queen Helena was the queen of Edessa in northern Syria. (Note - Agabus and Agbarus are the Roman and Syriac pronunciations of this king's name.)

According to the account, King Abgarus received the Image of Edessa, a likeness of Jesus. (

Public Domain

)And all the Edessan royalty, including King Abgarus, were bearded, a detail which suits the king in this mosaic much better than does Alexander or Antiochus. In fact, Josephus Flavius calls the Edessan monarchy the 'barbarians beyond the Euphrates', because they were bearded and lived across the Euphrates ('barbarian' being derived from 'barber' meaning 'hair', rather than from a foreign language). And all the Edessan kings wore the diadema headband, the same as in this mosaic, which was the symbol of both the Greek and the Greco-Persian royalty.

According to the account, King Abgarus received the Image of Edessa, a likeness of Jesus. (

Public Domain

)And all the Edessan royalty, including King Abgarus, were bearded, a detail which suits the king in this mosaic much better than does Alexander or Antiochus. In fact, Josephus Flavius calls the Edessan monarchy the 'barbarians beyond the Euphrates', because they were bearded and lived across the Euphrates ('barbarian' being derived from 'barber' meaning 'hair', rather than from a foreign language). And all the Edessan kings wore the diadema headband, the same as in this mosaic, which was the symbol of both the Greek and the Greco-Persian royalty.

So it is possible that this mosaic depicts King Abgar V of Edessa. But we are actually looking for the son of King Abgarus here (bar Kamza, not Kamza), and he was called King Izas Manu VI of Edessa. And we know that the Talmud's enigmatic character called bar Kamza was King Izas Manu of Edessa, because both are said to have lived in Antioch-Edessa, and both are said to have started the Jewish Revolt (see: Gittin 55-57, and Josephus Flavius). But who was this relatively unknown King Izas Manu? (who was almost completely deleted from the works of Josephus Flavius.) Believe it or not, King Izas Manu was the biblical King Jesus Em Manu-el, which is why the king on this mosaic wears a Judaic side-lock of hair. (These 'two' monarchs share many, many similarities, including their near-identical names and a ceremonial Crown of Thorns.)

King Solomon’s Mines Discovered: Kings and Pharaohs - Part I The Tomb of Alexander the Great - Part 1 Use of unique pyramid-shaped podium in Jerusalem baffles archaeologists Note that the character in this mosaic is dressed in military uniform and is wearing a purple cloak, which was the sole prerogative of the Roman Emperor, and so we know this king was claiming the throne of Rome. However, in a very similar fashion the biblical Jesus (King Izas Manu) was also pointedly said to have been dressed in a purple cloak (Mark 15:7). Why? Because the Jewish Revolt was primarily a revolt against Rome, rather than against Judaea, and King Izas Manu (the biblical Jesus) wanted to become the next emperor of Rome. Which is why both of these kings wore a purple cloak, and why their army is depicted as being defeated at the bottom of the mosaic. King Izas Manu of Edessa started and lost the Jewish Revolt, and according to Josephus Flavius he was crucified in the Kidron Valley alongside two others, but survived.

The Siege and Destruction of Jerusalem during Jewish-Roman war. (

Public Domain

)So the upper register of this mosaic depicts bar Kamza giving a sacrificial calf to the priests of Jerusalem, to start the Jewish Revolt, while the bottom register depicts his eventual defeat. And so we see here the start and the end of the Jewish Revolt - an event that plays a large role not just in Josephus Flavius' history of the Jews, but also in the Talmudic and Gospel accounts. And so this mosaic confirms that bar Kamza was King Izas Manu of Edessa, and confirms that King Izas Manu was the biblical King Jesus Manu-el. Which is, in turn, a complete confirmation of the new religio-historical framework discovered, explored, and explained in 'The King Jesus Trilogy'.

The Siege and Destruction of Jerusalem during Jewish-Roman war. (

Public Domain

)So the upper register of this mosaic depicts bar Kamza giving a sacrificial calf to the priests of Jerusalem, to start the Jewish Revolt, while the bottom register depicts his eventual defeat. And so we see here the start and the end of the Jewish Revolt - an event that plays a large role not just in Josephus Flavius' history of the Jews, but also in the Talmudic and Gospel accounts. And so this mosaic confirms that bar Kamza was King Izas Manu of Edessa, and confirms that King Izas Manu was the biblical King Jesus Manu-el. Which is, in turn, a complete confirmation of the new religio-historical framework discovered, explored, and explained in 'The King Jesus Trilogy'.

Ralph Ellis is author of Jesus, King of Edessa . You can find out more at Edfu-Books.com

The full mosaic can be seen here:

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/09/mysterious-mosaic-alexander-the-great-israel/

--

Top Image: Architectural elements and ruins at the archaeological site of Huqoq, Israel (CC BY-SA 3.0). Inset, decorated mosaic floor uncovered in the buried ruins of a synagogue at Huqoq. (National Geographic)

By Ralph Ellis

According to NationalGeographic.com, archaeologists have discovered an interesting and unusual mosaic at the Huqoq archaeological site west of the Sea of Galilee. The most recent and most interesting find dates from the 5th century, and shows a king in military attire and a troop of soldiers, offering a calf to a group of white-robed priests. But the meeting is obviously fractious, as the priests are drawing their swords, while the bottom of the scene shows the solders lying defeated and dying.

The scene has been compared to the semi-legendary meeting between Alexander the Great and the Jerusalem priesthood, in the 4th century BC. While other historians have suggested the mosaic represents the attack on Jerusalem by Antiochus VII in the 2nd century BC. But the characters are not named, which is unusual for mosaics in this era, and there are a number of problems with these interpretations. The main problem is that the king is bearded, which Antiochus and Alexander were not. And the meeting between Alexander and the Judaic priesthood was supposed to have been friendly, not antagonistic. And neither Alexander nor Antiochus were defeated, as the bottom of the mosaic appears to show.

Archaeological site of Huqoq, Israel, where the new mosaic has been revealed. (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)

Archaeological site of Huqoq, Israel, where the new mosaic has been revealed. (

CC BY-SA 3.0

) Detail of mosaic. (

Source:

NationalGeographic/Mark Thiessen)Mistaken IdentitySince traditional academia have been unable to satisfactorily decypher what this mosaic represents, perhaps we should rework these interpretations using the new religio-historical framework that has been constructed in 'The King Jesus Trilogy'. This radical new theory, which is fully supported by all the original texts, suggests that the gospel era and story refers to the late AD 60s, and the tragic events of the Jewish Revolt. And if we use this new framework, we can immediately see that this mosaic does not depict Alexander the Great or Antiochus. The classical interpretations are wrong.

Detail of mosaic. (

Source:

NationalGeographic/Mark Thiessen)Mistaken IdentitySince traditional academia have been unable to satisfactorily decypher what this mosaic represents, perhaps we should rework these interpretations using the new religio-historical framework that has been constructed in 'The King Jesus Trilogy'. This radical new theory, which is fully supported by all the original texts, suggests that the gospel era and story refers to the late AD 60s, and the tragic events of the Jewish Revolt. And if we use this new framework, we can immediately see that this mosaic does not depict Alexander the Great or Antiochus. The classical interpretations are wrong.More intriguingly, this is actually a depiction of an obscure scene from the Talmud, where bar Kamza offers a sacrificial calf on behalf of the Romans, to rabbi Zechariah Abkulas (see Gittin 55-57). This was in about AD 68, just prior to the Jewish Revolt. But bar Kamza was being devious here, because he had cut the calf's lip (you can see the mark on the mosaic), knowing that Zechariah would have to reject the blemished Roman offering - and thereby offend the Romans, and in turn precipitate the Jewish Revolt. This was one of the ways by which the Jewish Revolt was deliberately contrived.

Eden in Egypt – Part 1 The Surprising Links Between Alexander the Great and Christianity Does newly-translated Hebrew text reveal insights into King Solomon’s treasures? So who was this mysterious and largely unknown character called bar Kamza? Well, in actual fact, Kamza is merely a witty hypocorism meaning 'locust'. And there was a royal family in Syria who were similarly disparaged as being locusts, one of whom was Agabus (meaning locust) who appears in Acts of the Apostles (Acts 11:27). This Syrian Agabus in Acts prophesied the great Judaean famine of AD 47 and gave famine relief-money, just as did the more famous Queen Helena. And this confirms that this royal family of 'locusts' was actually the Syrian monarchy of King Abgarus V of Edessa, because he was married to this very same Queen Helena. Yes, the famous 1st century Queen Helena was the queen of Edessa in northern Syria. (Note - Agabus and Agbarus are the Roman and Syriac pronunciations of this king's name.)

According to the account, King Abgarus received the Image of Edessa, a likeness of Jesus. (

Public Domain

)And all the Edessan royalty, including King Abgarus, were bearded, a detail which suits the king in this mosaic much better than does Alexander or Antiochus. In fact, Josephus Flavius calls the Edessan monarchy the 'barbarians beyond the Euphrates', because they were bearded and lived across the Euphrates ('barbarian' being derived from 'barber' meaning 'hair', rather than from a foreign language). And all the Edessan kings wore the diadema headband, the same as in this mosaic, which was the symbol of both the Greek and the Greco-Persian royalty.

According to the account, King Abgarus received the Image of Edessa, a likeness of Jesus. (

Public Domain

)And all the Edessan royalty, including King Abgarus, were bearded, a detail which suits the king in this mosaic much better than does Alexander or Antiochus. In fact, Josephus Flavius calls the Edessan monarchy the 'barbarians beyond the Euphrates', because they were bearded and lived across the Euphrates ('barbarian' being derived from 'barber' meaning 'hair', rather than from a foreign language). And all the Edessan kings wore the diadema headband, the same as in this mosaic, which was the symbol of both the Greek and the Greco-Persian royalty.So it is possible that this mosaic depicts King Abgar V of Edessa. But we are actually looking for the son of King Abgarus here (bar Kamza, not Kamza), and he was called King Izas Manu VI of Edessa. And we know that the Talmud's enigmatic character called bar Kamza was King Izas Manu of Edessa, because both are said to have lived in Antioch-Edessa, and both are said to have started the Jewish Revolt (see: Gittin 55-57, and Josephus Flavius). But who was this relatively unknown King Izas Manu? (who was almost completely deleted from the works of Josephus Flavius.) Believe it or not, King Izas Manu was the biblical King Jesus Em Manu-el, which is why the king on this mosaic wears a Judaic side-lock of hair. (These 'two' monarchs share many, many similarities, including their near-identical names and a ceremonial Crown of Thorns.)

King Solomon’s Mines Discovered: Kings and Pharaohs - Part I The Tomb of Alexander the Great - Part 1 Use of unique pyramid-shaped podium in Jerusalem baffles archaeologists Note that the character in this mosaic is dressed in military uniform and is wearing a purple cloak, which was the sole prerogative of the Roman Emperor, and so we know this king was claiming the throne of Rome. However, in a very similar fashion the biblical Jesus (King Izas Manu) was also pointedly said to have been dressed in a purple cloak (Mark 15:7). Why? Because the Jewish Revolt was primarily a revolt against Rome, rather than against Judaea, and King Izas Manu (the biblical Jesus) wanted to become the next emperor of Rome. Which is why both of these kings wore a purple cloak, and why their army is depicted as being defeated at the bottom of the mosaic. King Izas Manu of Edessa started and lost the Jewish Revolt, and according to Josephus Flavius he was crucified in the Kidron Valley alongside two others, but survived.

The Siege and Destruction of Jerusalem during Jewish-Roman war. (

Public Domain

)So the upper register of this mosaic depicts bar Kamza giving a sacrificial calf to the priests of Jerusalem, to start the Jewish Revolt, while the bottom register depicts his eventual defeat. And so we see here the start and the end of the Jewish Revolt - an event that plays a large role not just in Josephus Flavius' history of the Jews, but also in the Talmudic and Gospel accounts. And so this mosaic confirms that bar Kamza was King Izas Manu of Edessa, and confirms that King Izas Manu was the biblical King Jesus Manu-el. Which is, in turn, a complete confirmation of the new religio-historical framework discovered, explored, and explained in 'The King Jesus Trilogy'.

The Siege and Destruction of Jerusalem during Jewish-Roman war. (

Public Domain

)So the upper register of this mosaic depicts bar Kamza giving a sacrificial calf to the priests of Jerusalem, to start the Jewish Revolt, while the bottom register depicts his eventual defeat. And so we see here the start and the end of the Jewish Revolt - an event that plays a large role not just in Josephus Flavius' history of the Jews, but also in the Talmudic and Gospel accounts. And so this mosaic confirms that bar Kamza was King Izas Manu of Edessa, and confirms that King Izas Manu was the biblical King Jesus Manu-el. Which is, in turn, a complete confirmation of the new religio-historical framework discovered, explored, and explained in 'The King Jesus Trilogy'.Ralph Ellis is author of Jesus, King of Edessa . You can find out more at Edfu-Books.com

The full mosaic can be seen here:

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/09/mysterious-mosaic-alexander-the-great-israel/

--

Top Image: Architectural elements and ruins at the archaeological site of Huqoq, Israel (CC BY-SA 3.0). Inset, decorated mosaic floor uncovered in the buried ruins of a synagogue at Huqoq. (National Geographic)

By Ralph Ellis

Published on September 19, 2016 03:00

September 18, 2016

How naughty was the past? The hidden depths of the medieval church

History Extra

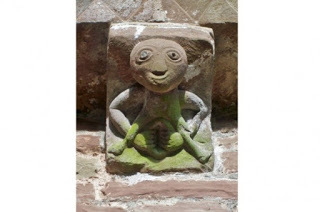

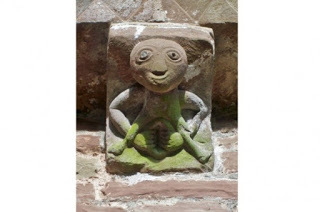

Sheela-na-gig. © Poliphilo (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

Sheela-na-gig. © Poliphilo (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

1) Monkeying aroundIn the north nave aisle of York Minster is the famous Pilgrimage Window (dated c1330). The window is named after the depiction of the crucifixion in its main lights, which is sited above male and female pilgrims flanking St Peter. St Peter is portrayed not only with his usual attribute of the key [of heaven] but also by the less familiar image of a church held within his hand – very fitting considering he was the patron saint of the cathedral.

Structured much like an illuminated manuscript page, the most intriguing element of the window’s composition is the amusing animal imagery in the lower margins. Among these scenes is a funeral procession of monkeys with a bell-ringer; cross-bearer; four pall-bearers carrying a bier to which another monkey clings and a monkey doctor examines his sick ape patient; while along the vertical borders are further squirrels and monkeys, some investigating urine flasks. There is also a fox preaching to a cock; a parody of a hunt with a stag chasing a hound; a fox stealing a goose pursued by a woman, while an archer and other animals complete the border scene. But, as Bernard of Clairvaux asked in 1125, “to what purpose are those unclean apes?” And how should they be ‘read’?

Animals in medieval art need to be seen within their wider context, instead of ascribing each single motif with a meaning. Not only in stained glass, but more commonly in manuscripts, borders were decorated with exotic animals, grotesque hybrids, animals mimicking humans, humans in animal form, and mythical creatures performing lewd and humorous antics. In fact, animals are used throughout medieval art as iconographical representations or portraying allegorical qualities.

Many, including lions, were used because of their proximity to people. This could be due to their bestial human nature. An example of this can be found within the presbytery of Exeter Cathedral where a 14th-century roof boss depicts a lion standing on his rear legs, twisting his head around to face a male figure, likely Samson from the biblical tale, who is forcing the jaws of the creature apart.

Lions were also employed as representations of Christ and as the evangelist, St Mark. A great example of Mark and his winged lion attribute can be found in the 12th-century ‘Worms Bible’, housed at the British Library.

One of the more curious marginal motifs was the use of monkeys. Monkeys were often represented doing human-like activities, including playing instruments and games, hunting, eating and drinking, but the overall purpose was to suggest the folly of man. In the Christian tradition apes were seen as thoughtless, compulsive imitators of human actions, parodies of humanity, displaying gluttony, vanity and foolishness – powerful reminders of the potential within all medieval men and women to engage in depraved acts and sin.

The inclusion of monkeys in the Pilgrimage Window, then, was therefore both a deliberate and conscious choice by the York stained-glass artist. It was believed that apes were so-called as they were said to ‘ape’ the behaviour of human beings – hence the scene is thought to be an apocryphal story or parody of the funeral of the Virgin enacted by monkeys. The monkeys are included to make a serious point and a connection to the broader iconography on the window. The monkey’s funeral ‘apes’ the humility and charity of St Peter overhead, as the devotee’s eye travels between ‘the world’ in the lower margins (that filled with man and sin) and the devotional space of the main lights above (the kingdom of Heaven).

The monkey physicians also mimic the medical profession, combining satire with a serious underlying moral – they echoed the widespread suspicion and disdain for ‘Doctours of Physik’ because it was felt that ultimately only Christ could cure the souls of man. The fox stories, too, have similar allegorical meanings, most commonly highlighting the consequences of lapses in devotion and often appearing in bestiaries and art as a symbol of the sly and sophisticated devil.

2) The Mooning ManThe 12th-century Parish Church of All Saints in Easton-on-the-Hill, just outside Stamford in Northamptonshire, features a wealth of architectural styles from Norman through to neo-Gothic. Yet, as you approach the south porch you may be shocked by the 15th-century stone gargoyle perched on the side of the tower: a ‘mooning’ man! Local legend has it that his proud posterior is pointing in the direction of the stonemason of Peterborough Cathedral, in protest at not being paid.

These types of carvings can be found adorning the exteriors of churches across the country in the form of gargoyles, grotesques and also as ornamental frieze fixtures. Before continuing, here is a short explanation of the differences between their functions: though the word ‘gargoyle’ is often misused as a generic term for grotesque carvings on churches, a true gargoyle is a decorative waterspout that preserves stonework by diverting the flow of rainwater away from the roof and walls of a church to the ground below. On the other hand, ‘grotesques’, while they are similarly stone carvings or sculptures, serve only an ornamental or artistic function, and do not include a spout.

Although it is not entirely clear when this bold ‘artwork’ first emerged, it appears to have coincided with the emergence of the Gothic style or, more specifically, the Perpendicular era (1375–1530), with the majority dating to the 14th century – these include several other examples of male contortionist gargoyles, such as those at Lyndon (Rutland), Colsterworth and Sleaford (Lincs), and at Glinton (Cambs).

Several other mooning grotesques can be found across the British Isles, again dating from the same period. The example at Easton features a rather brazen pose: bent over, bottom in the air, legs spread apart but with his head peering round from the right and the strategically placed hole inserted for the practical purpose of diverting rainwater, rather than to illustrate any anatomical features (of course!), and so his proud posterior officially serves its purpose. It is hardly surprising that mischievous masons could not resist the urge to use such orifices for this purpose and that, by the time of the Easton carving in the 15th century, they were certainly embracing the humour of the secular world without feeling affront.

Yet, explaining the general purpose of these impish figures is a rather tricky task. There is certainly ample evidence that people mooned each other during the Middle Ages as a sign of insult – for example, in ‘The Miller’s Tale’ from Geoffrey Chaucer’s late 14th-century Canterbury Tales, characters Alison and Nicholas trick Absolon into kissing her behind – though admittedly this gesture is not quite the same as mooning.

Many therefore believe the Easton carvings to be ultimately protective or apotropaic – to reflect the contrast between a world outside the church beset by the devil and sin as opposed to the sanctity contained within its walls. The idea is that they were placed to deflect the evil spirits by drawing their attention to these insulting characters. So, perhaps the mooner is proudly cocking a snook at the Devil, though he may equally be intended to shock, amuse, or act as a counter and balance to the religious.

© Lionel Wall www.greatenglishchurches.co.uk

3) Kiss me quick!Among the 14th-century misericords at Chichester Cathedral is an energetically captured carved scene of a musician with a citole (an instrument popular between the late 13th and 14th century, formerly known as a gittern, later remodelled as a violin) who is in the midst of stealing a kiss from a dancing woman or posture maker.

Misericords are the carved timber (usually oak) undersides or ledges of tip-up seats on which ecclesiastics could rest their bottoms in the choirs of English cathedrals and collegiate churches during the Divine Office (this particular seat at Chichester was reserved for the Prebend of Somerley). They first appeared in churches in the early 13th century, with the majority dating from the mid-13th to the late 15th centuries. From the Latin word meaning pity, the name literally translates to their function: a demonstration of mercy, as they were designed to support the sitter in an upright position.

The undersides depict an assortment of figural carvings that could be displayed or concealed depending on the position of the seat. This may explain why, although only seen by medieval clerics, the carvings seldom displayed sacred images of Christ, biblical scenes or the saints, but rather vernacular subjects – scenes from daily life, customs, humour and beliefs that included some crudity but also a great sense of fun, freedom and vigour. Subjects vary widely, but we again see many of the same ‘naughty’ yet allegorical representations occurring here as elsewhere in this article, such as temptations of lust, apes with urine flasks, the Green Man (usually a carving or sculpture of a man’s face surrounded by or made from foliage), birds and beasts, abstract foliate designs and medieval folk tales and legends.

What’s more, many scenes can be interpreted as sermons ‘come to life’, used to instruct common folk on principles of doctrine. While certain figural scenes may at first appear secular, they were actually reminders to their ecclesiastical viewer of his professional responsibility to educate the masses against temptations to sin. The profane and debauched images of the sexual lives of laypeople would prompt the medieval cleric to shun women, have self-control and fear the wrath of God.

© www.misericords.co.uk

4) Full-frontal exposureAlthough the 12th-century Church of St Mary and St David at Kilpeck, Herefordshire, comprises fairly typical architecture, it also hides some extraordinary carvings including writhing snakes and mysterious beasts. But, most extraordinary of all, is one of England’s best-preserved examples of a Sheela-na-gig.

Sheela-na-gigs are figurative stone carvings (occasionally appearing in wood-form on misericords) depicting a naked woman in a seated position with her legs wide, openly exposing her genitalia. The name likely derives from the Irish to mean ‘Sheela of the breasts’. Examples are most often found above doorways and windows on medieval churches and castles in northern Europe, predominantly Ireland and Britain, but also in a few locations elsewhere in Europe, such as the contortionist capital example at the monastery of San Pedro de Cervatos in Cantabria, Spain. Determining their date and place of origin has proved difficult, with many scholars disagreeing over the origins of the figures, as many are believed to have been reused from previous, older structures. However, they appear on churches across the 11th to 17th centuries and were likely first carved in France or Spain.

A fairly strange image to find on a church, you might suggest? Well, though Sheela-na-gigs may seem erotic in nature, it is doubtful these carvings were ever intended to arouse and were actually pagan symbols of fertility as well as warnings against lust and warders or protectors from evil – hence their positions over entranceways. Other opinions are that, given their crude form, Sheela-na-gigs were produced by local amateur carvers and therefore represent folk deities that were associated with life-giving powers, birth, death and the renewal of life. Even so, throughout the past, embarrassed or high-minded churchgoers and clerics often removed, covered or destroyed what they viewed as offensive carvings.

5) Word vomitKnown as the greatest medieval graffiti church in England (and it is, at least, the most extensively studied), the 14th-century Church of St Mary’s at Ashwell in Hertfordshire contains an etching that is believed to be one of the only surviving depictions of Old St Paul’s Cathedral. It records the arrival of the Black Death and Peasants’ Revolt, but it is the Latin inscriptions scrawled across the pillars to which this entry refers.

Varying from popular sayings to pithy comments, one seems likely to have been written by a disgruntled architect: Cornua non sunt arto compugenta sputuo (‘The corners are not jointed correctly. I spit on them’) and seems to date to between 1350 and 1400. Another is a less-than-flattering view of the local archdeacon: Archi(di)aconus Asemnes (‘The Archdeacon is an ass’). Finally, no doubt in a spate of sobriety, a wise-old drunk etched: Ebrietas frangit quicquid sapienta tangit (‘Drunkenness breaks whatever wisdom touches’).

Modern visitors are often captivated by these ‘naughty’ writings on the wall because we expect the medieval era to be more conservative when compared to our own society – but do the things that make us chuckle ever really change…?

Cornua non sunt arto compugenta sputuo (‘The corners are not jointed correctly. I spit on them’). © Matthew Champion

Cornua non sunt arto compugenta sputuo (‘The corners are not jointed correctly. I spit on them’). © Matthew Champion

6) “Look out below – men at stool!”The Church of St Mary in Redcliffe, Bristol boasts a remarkable collection of more than 1,100 ceiling bosses dating from 1330 to 1446 (when much of the vault had to be rebuilt after the spire collapsed) and features a variety of symbolic and mythological subjects including the famous ‘maze’ boss that is actually a model of the church’s transept roof.

Ceiling or roof bosses are carvings crafted in wood or stone specifically to cover the intersection between the stone ribs of vaulted ceilings or where the roof timbers join or meet at an angle. Again, this medieval art form depicts many of the contemporary craftsmen’s favourite subjects: biblical scenes, animals, leaves, flowers and heraldry, but with crude humour often casually sited alongside scenes of everyday life. Curiously, though, very few bosses actually carry a date.

The boss sited under Redcliffe’s tower is the most fascinating of all: it depicts a rather bizarre male exhibitionist with his posterior waving in the air, proudly defecating on all who walk beneath him.

Their purpose was to signal the especially holy parts of the church such as the position of important altars, shrines or chapels. Due to the fact that they are located among the less immediately visible parts of the church building, some scholars have argued that these unseen areas became dens of artistic iniquity for marginalised subjects – they certainly offer a curious commentary on the mentality of medieval craftsmen! Accordingly, there is little doubt that the Redcliffe ‘man at stool’ was located closer to eye-level than some of the other bosses for shock value – to inspire reflection, the withholding of temptation and to illustrate that the repetition of such incongruous behaviour would lead to one’s own spiritual distortion. Reader, take note!

7) Drinking with the enemySituated above the chancel arch of the Church of St Thomas and St Edmund in Salisbury is a powerful mural that catches the eye of visitors immediately upon entry. Executed in 1475 as an offering of thanks for a safely returned pilgrim, this depiction is believed to be the largest Doom in England.

Doom or Last Judgment paintings were the most commonly painted subject of the medieval parish church and are thought to have once adorned the wall above the chancel arches of most churches across the entire country from the late 11th century. The reason for this was that they were sited at the symbolic point at which the nave of the laity, sphere of the parishioners and world of sin met the holy and consecrated sanctuary reserved for the priest. They present the final judgment of humanity, drawing on imagery from a range of scripture, particularly the Parable of the Sheep and Goats.

A most interesting feature of the Salisbury composition is down in the right-hand corner where a dishonest alewife with a jug in hand hugs a demon, leading to her serving short measures. As a result, her ‘naughty’ act has doomed her to hell for all eternity. It was believed at the time that alewives encompassed a multitude of sins: encouraging idleness and overindulgence, tempting with provocative clothing, and overt displays of wealth, greed and excess, not to mention corruption – ie over-charging customers and watering down the ale (sinful!). They occur on many doom paintings, often giving their tormentors seductive glances, as if looking forward to a diabolical party. They were also standard characters of the medieval mystery plays – again, figures of ridicule, the buxom wench.

An obvious yet literal interpretation of the scene is to emphasise that rank or position counts for nothing on the day of judgment, as all are judged equally according to our sins in the eyes of God. A scroll towards the bottom of the painting reads: Nulla est Redemptio or ‘There is no escape for the wicked’/ ‘There is no redemption’.

Amanda Miller @ Amanda’s Arcadia

Amanda Miller @ Amanda’s Arcadia

Dr Emma J Wells is associate lecturer and programme director in parish church studies at the University of York and an historic buildings consultant. She is the author of the forthcoming Pilgrim Routes of the British Isles (Robert Hale, out 11 October 2016).

Sheela-na-gig. © Poliphilo (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

Sheela-na-gig. © Poliphilo (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons 1) Monkeying aroundIn the north nave aisle of York Minster is the famous Pilgrimage Window (dated c1330). The window is named after the depiction of the crucifixion in its main lights, which is sited above male and female pilgrims flanking St Peter. St Peter is portrayed not only with his usual attribute of the key [of heaven] but also by the less familiar image of a church held within his hand – very fitting considering he was the patron saint of the cathedral.

Structured much like an illuminated manuscript page, the most intriguing element of the window’s composition is the amusing animal imagery in the lower margins. Among these scenes is a funeral procession of monkeys with a bell-ringer; cross-bearer; four pall-bearers carrying a bier to which another monkey clings and a monkey doctor examines his sick ape patient; while along the vertical borders are further squirrels and monkeys, some investigating urine flasks. There is also a fox preaching to a cock; a parody of a hunt with a stag chasing a hound; a fox stealing a goose pursued by a woman, while an archer and other animals complete the border scene. But, as Bernard of Clairvaux asked in 1125, “to what purpose are those unclean apes?” And how should they be ‘read’?

Animals in medieval art need to be seen within their wider context, instead of ascribing each single motif with a meaning. Not only in stained glass, but more commonly in manuscripts, borders were decorated with exotic animals, grotesque hybrids, animals mimicking humans, humans in animal form, and mythical creatures performing lewd and humorous antics. In fact, animals are used throughout medieval art as iconographical representations or portraying allegorical qualities.

Many, including lions, were used because of their proximity to people. This could be due to their bestial human nature. An example of this can be found within the presbytery of Exeter Cathedral where a 14th-century roof boss depicts a lion standing on his rear legs, twisting his head around to face a male figure, likely Samson from the biblical tale, who is forcing the jaws of the creature apart.

Lions were also employed as representations of Christ and as the evangelist, St Mark. A great example of Mark and his winged lion attribute can be found in the 12th-century ‘Worms Bible’, housed at the British Library.

One of the more curious marginal motifs was the use of monkeys. Monkeys were often represented doing human-like activities, including playing instruments and games, hunting, eating and drinking, but the overall purpose was to suggest the folly of man. In the Christian tradition apes were seen as thoughtless, compulsive imitators of human actions, parodies of humanity, displaying gluttony, vanity and foolishness – powerful reminders of the potential within all medieval men and women to engage in depraved acts and sin.

The inclusion of monkeys in the Pilgrimage Window, then, was therefore both a deliberate and conscious choice by the York stained-glass artist. It was believed that apes were so-called as they were said to ‘ape’ the behaviour of human beings – hence the scene is thought to be an apocryphal story or parody of the funeral of the Virgin enacted by monkeys. The monkeys are included to make a serious point and a connection to the broader iconography on the window. The monkey’s funeral ‘apes’ the humility and charity of St Peter overhead, as the devotee’s eye travels between ‘the world’ in the lower margins (that filled with man and sin) and the devotional space of the main lights above (the kingdom of Heaven).

The monkey physicians also mimic the medical profession, combining satire with a serious underlying moral – they echoed the widespread suspicion and disdain for ‘Doctours of Physik’ because it was felt that ultimately only Christ could cure the souls of man. The fox stories, too, have similar allegorical meanings, most commonly highlighting the consequences of lapses in devotion and often appearing in bestiaries and art as a symbol of the sly and sophisticated devil.

2) The Mooning ManThe 12th-century Parish Church of All Saints in Easton-on-the-Hill, just outside Stamford in Northamptonshire, features a wealth of architectural styles from Norman through to neo-Gothic. Yet, as you approach the south porch you may be shocked by the 15th-century stone gargoyle perched on the side of the tower: a ‘mooning’ man! Local legend has it that his proud posterior is pointing in the direction of the stonemason of Peterborough Cathedral, in protest at not being paid.

These types of carvings can be found adorning the exteriors of churches across the country in the form of gargoyles, grotesques and also as ornamental frieze fixtures. Before continuing, here is a short explanation of the differences between their functions: though the word ‘gargoyle’ is often misused as a generic term for grotesque carvings on churches, a true gargoyle is a decorative waterspout that preserves stonework by diverting the flow of rainwater away from the roof and walls of a church to the ground below. On the other hand, ‘grotesques’, while they are similarly stone carvings or sculptures, serve only an ornamental or artistic function, and do not include a spout.

Although it is not entirely clear when this bold ‘artwork’ first emerged, it appears to have coincided with the emergence of the Gothic style or, more specifically, the Perpendicular era (1375–1530), with the majority dating to the 14th century – these include several other examples of male contortionist gargoyles, such as those at Lyndon (Rutland), Colsterworth and Sleaford (Lincs), and at Glinton (Cambs).

Several other mooning grotesques can be found across the British Isles, again dating from the same period. The example at Easton features a rather brazen pose: bent over, bottom in the air, legs spread apart but with his head peering round from the right and the strategically placed hole inserted for the practical purpose of diverting rainwater, rather than to illustrate any anatomical features (of course!), and so his proud posterior officially serves its purpose. It is hardly surprising that mischievous masons could not resist the urge to use such orifices for this purpose and that, by the time of the Easton carving in the 15th century, they were certainly embracing the humour of the secular world without feeling affront.

Yet, explaining the general purpose of these impish figures is a rather tricky task. There is certainly ample evidence that people mooned each other during the Middle Ages as a sign of insult – for example, in ‘The Miller’s Tale’ from Geoffrey Chaucer’s late 14th-century Canterbury Tales, characters Alison and Nicholas trick Absolon into kissing her behind – though admittedly this gesture is not quite the same as mooning.

Many therefore believe the Easton carvings to be ultimately protective or apotropaic – to reflect the contrast between a world outside the church beset by the devil and sin as opposed to the sanctity contained within its walls. The idea is that they were placed to deflect the evil spirits by drawing their attention to these insulting characters. So, perhaps the mooner is proudly cocking a snook at the Devil, though he may equally be intended to shock, amuse, or act as a counter and balance to the religious.

© Lionel Wall www.greatenglishchurches.co.uk

3) Kiss me quick!Among the 14th-century misericords at Chichester Cathedral is an energetically captured carved scene of a musician with a citole (an instrument popular between the late 13th and 14th century, formerly known as a gittern, later remodelled as a violin) who is in the midst of stealing a kiss from a dancing woman or posture maker.

Misericords are the carved timber (usually oak) undersides or ledges of tip-up seats on which ecclesiastics could rest their bottoms in the choirs of English cathedrals and collegiate churches during the Divine Office (this particular seat at Chichester was reserved for the Prebend of Somerley). They first appeared in churches in the early 13th century, with the majority dating from the mid-13th to the late 15th centuries. From the Latin word meaning pity, the name literally translates to their function: a demonstration of mercy, as they were designed to support the sitter in an upright position.

The undersides depict an assortment of figural carvings that could be displayed or concealed depending on the position of the seat. This may explain why, although only seen by medieval clerics, the carvings seldom displayed sacred images of Christ, biblical scenes or the saints, but rather vernacular subjects – scenes from daily life, customs, humour and beliefs that included some crudity but also a great sense of fun, freedom and vigour. Subjects vary widely, but we again see many of the same ‘naughty’ yet allegorical representations occurring here as elsewhere in this article, such as temptations of lust, apes with urine flasks, the Green Man (usually a carving or sculpture of a man’s face surrounded by or made from foliage), birds and beasts, abstract foliate designs and medieval folk tales and legends.

What’s more, many scenes can be interpreted as sermons ‘come to life’, used to instruct common folk on principles of doctrine. While certain figural scenes may at first appear secular, they were actually reminders to their ecclesiastical viewer of his professional responsibility to educate the masses against temptations to sin. The profane and debauched images of the sexual lives of laypeople would prompt the medieval cleric to shun women, have self-control and fear the wrath of God.

© www.misericords.co.uk

4) Full-frontal exposureAlthough the 12th-century Church of St Mary and St David at Kilpeck, Herefordshire, comprises fairly typical architecture, it also hides some extraordinary carvings including writhing snakes and mysterious beasts. But, most extraordinary of all, is one of England’s best-preserved examples of a Sheela-na-gig.

Sheela-na-gigs are figurative stone carvings (occasionally appearing in wood-form on misericords) depicting a naked woman in a seated position with her legs wide, openly exposing her genitalia. The name likely derives from the Irish to mean ‘Sheela of the breasts’. Examples are most often found above doorways and windows on medieval churches and castles in northern Europe, predominantly Ireland and Britain, but also in a few locations elsewhere in Europe, such as the contortionist capital example at the monastery of San Pedro de Cervatos in Cantabria, Spain. Determining their date and place of origin has proved difficult, with many scholars disagreeing over the origins of the figures, as many are believed to have been reused from previous, older structures. However, they appear on churches across the 11th to 17th centuries and were likely first carved in France or Spain.

A fairly strange image to find on a church, you might suggest? Well, though Sheela-na-gigs may seem erotic in nature, it is doubtful these carvings were ever intended to arouse and were actually pagan symbols of fertility as well as warnings against lust and warders or protectors from evil – hence their positions over entranceways. Other opinions are that, given their crude form, Sheela-na-gigs were produced by local amateur carvers and therefore represent folk deities that were associated with life-giving powers, birth, death and the renewal of life. Even so, throughout the past, embarrassed or high-minded churchgoers and clerics often removed, covered or destroyed what they viewed as offensive carvings.

5) Word vomitKnown as the greatest medieval graffiti church in England (and it is, at least, the most extensively studied), the 14th-century Church of St Mary’s at Ashwell in Hertfordshire contains an etching that is believed to be one of the only surviving depictions of Old St Paul’s Cathedral. It records the arrival of the Black Death and Peasants’ Revolt, but it is the Latin inscriptions scrawled across the pillars to which this entry refers.

Varying from popular sayings to pithy comments, one seems likely to have been written by a disgruntled architect: Cornua non sunt arto compugenta sputuo (‘The corners are not jointed correctly. I spit on them’) and seems to date to between 1350 and 1400. Another is a less-than-flattering view of the local archdeacon: Archi(di)aconus Asemnes (‘The Archdeacon is an ass’). Finally, no doubt in a spate of sobriety, a wise-old drunk etched: Ebrietas frangit quicquid sapienta tangit (‘Drunkenness breaks whatever wisdom touches’).

Modern visitors are often captivated by these ‘naughty’ writings on the wall because we expect the medieval era to be more conservative when compared to our own society – but do the things that make us chuckle ever really change…?

Cornua non sunt arto compugenta sputuo (‘The corners are not jointed correctly. I spit on them’). © Matthew Champion

Cornua non sunt arto compugenta sputuo (‘The corners are not jointed correctly. I spit on them’). © Matthew Champion6) “Look out below – men at stool!”The Church of St Mary in Redcliffe, Bristol boasts a remarkable collection of more than 1,100 ceiling bosses dating from 1330 to 1446 (when much of the vault had to be rebuilt after the spire collapsed) and features a variety of symbolic and mythological subjects including the famous ‘maze’ boss that is actually a model of the church’s transept roof.

Ceiling or roof bosses are carvings crafted in wood or stone specifically to cover the intersection between the stone ribs of vaulted ceilings or where the roof timbers join or meet at an angle. Again, this medieval art form depicts many of the contemporary craftsmen’s favourite subjects: biblical scenes, animals, leaves, flowers and heraldry, but with crude humour often casually sited alongside scenes of everyday life. Curiously, though, very few bosses actually carry a date.

The boss sited under Redcliffe’s tower is the most fascinating of all: it depicts a rather bizarre male exhibitionist with his posterior waving in the air, proudly defecating on all who walk beneath him.

Their purpose was to signal the especially holy parts of the church such as the position of important altars, shrines or chapels. Due to the fact that they are located among the less immediately visible parts of the church building, some scholars have argued that these unseen areas became dens of artistic iniquity for marginalised subjects – they certainly offer a curious commentary on the mentality of medieval craftsmen! Accordingly, there is little doubt that the Redcliffe ‘man at stool’ was located closer to eye-level than some of the other bosses for shock value – to inspire reflection, the withholding of temptation and to illustrate that the repetition of such incongruous behaviour would lead to one’s own spiritual distortion. Reader, take note!

7) Drinking with the enemySituated above the chancel arch of the Church of St Thomas and St Edmund in Salisbury is a powerful mural that catches the eye of visitors immediately upon entry. Executed in 1475 as an offering of thanks for a safely returned pilgrim, this depiction is believed to be the largest Doom in England.

Doom or Last Judgment paintings were the most commonly painted subject of the medieval parish church and are thought to have once adorned the wall above the chancel arches of most churches across the entire country from the late 11th century. The reason for this was that they were sited at the symbolic point at which the nave of the laity, sphere of the parishioners and world of sin met the holy and consecrated sanctuary reserved for the priest. They present the final judgment of humanity, drawing on imagery from a range of scripture, particularly the Parable of the Sheep and Goats.

A most interesting feature of the Salisbury composition is down in the right-hand corner where a dishonest alewife with a jug in hand hugs a demon, leading to her serving short measures. As a result, her ‘naughty’ act has doomed her to hell for all eternity. It was believed at the time that alewives encompassed a multitude of sins: encouraging idleness and overindulgence, tempting with provocative clothing, and overt displays of wealth, greed and excess, not to mention corruption – ie over-charging customers and watering down the ale (sinful!). They occur on many doom paintings, often giving their tormentors seductive glances, as if looking forward to a diabolical party. They were also standard characters of the medieval mystery plays – again, figures of ridicule, the buxom wench.

An obvious yet literal interpretation of the scene is to emphasise that rank or position counts for nothing on the day of judgment, as all are judged equally according to our sins in the eyes of God. A scroll towards the bottom of the painting reads: Nulla est Redemptio or ‘There is no escape for the wicked’/ ‘There is no redemption’.

Amanda Miller @ Amanda’s Arcadia

Amanda Miller @ Amanda’s ArcadiaDr Emma J Wells is associate lecturer and programme director in parish church studies at the University of York and an historic buildings consultant. She is the author of the forthcoming Pilgrim Routes of the British Isles (Robert Hale, out 11 October 2016).

Published on September 18, 2016 03:00

September 17, 2016

Period dramas should not be judged on historical accuracy, say historians

History Extra

Aidan Turner as Ross Poldark in BBC One drama 'Poldark'. Fictional interpretations of the past should be rewarded, says the show’s historical adviser and historian Hannah Greig. (BBC/Adrian Rogers)

Aidan Turner as Ross Poldark in BBC One drama 'Poldark'. Fictional interpretations of the past should be rewarded, says the show’s historical adviser and historian Hannah Greig. (BBC/Adrian Rogers)

In a podcast interview with History Extra, Poldark’s historical adviser, the historian Hannah Greig and Horrible Histories consultant Greg Jenner said dramatists should have the freedom to fictionally interpret the past.

“I don’t think dramatists need to be historians; I don’t think it’s their job,” said Jenner. “I think drama is there to entertain us. Dramatists are there to spellbind us, to make us laugh and cry and fear for our favourite characters.”

Hannah agreed: “In some ways the most important thing is to have great story. That has to be the priority. A historical adviser can help to drive that story forward, informed by what we know about the past, but Greg is probably right that we shouldn’t try to determine what that story is.”

Hannah continued: “The discussion of accuracy is something that crops up a lot on Twitter and in newspapers – it’s a way in which lots of [historical] dramas are judged. As a historian involved in the process I’m always asking myself ‘what does that mean? What are we trying to achieve by creating something that’s accurate?’ Because history is continually being made by new scholarship and by historians.

“So we can think about things being well informed by historical knowledge, but that’s not quite the same issue as ‘have they got everything right?’ And I’m not sure that the second part of that is particularly helpful – ‘oh, is that the exactly the right piece of clothing; is that the perfect period-precise room?’

“For me what’s important are ‘is the narrative meaningful for the time in which it’s set? Are the characters’ motivations informed by the choices that I would understand as being the choices that were faced by the people at the time? Does it carry me emotionally in the way that I might think about the historical past?’

“Those are the issues that really matter to me as a historian, and less so about whether we’ve sourced exactly the right wine glass”.

Drawing a distinction between historical dramas, Greg said: “I tend to think there are different categories for history on television as drama: you have the actual historical events that happened and you’re trying to dramatise those – I think that’s where perhaps there’s more of a burden to get it right or at least be pretty respectful of the truth – or what you think is the truth. And then you have the literary adaptations or the entirely fictional where you invent historical scenarios. For example, Poldark is a literary adaptation from the 1940s.

“So if you’re making a drama about, say the Titanic or the First World War – something where real lives were lost or real stories were felt, where there’s that potency of the real human story – I think then perhaps that’s when there is more of a responsibility to be at least engaging with history.”

Hannah agreed: “Poldark is adapted from a novel so in some ways the burden of responsibility for the production is to make sure that it’s as close an adaptation of that novel as possible. Whereas the Victoria series [on ITV] is about a British monarch, so there’s a responsibility there with the history to ensure that that is a fair interpretation of those real and incredibly important characters in the British past and to tell that history in a significant and informed way.”

Greg went on to say: “History doesn’t fall into three-act structures. Life is complex and difficult to dramatise in such a simplistic ways. Stories have to have very rigid structures and I’m not sure history fits that well sometimes into those structures”.

Hannah agreed: “I think there should be space for us to acknowledge and reward fictional interpretations [of the past] more. I think if we continually have the conversation of accuracy and ‘everything must be accurate’ then it weighs down dramas to become less creative”.

To listen to the podcast interview in full, click here.

Aidan Turner as Ross Poldark in BBC One drama 'Poldark'. Fictional interpretations of the past should be rewarded, says the show’s historical adviser and historian Hannah Greig. (BBC/Adrian Rogers)

Aidan Turner as Ross Poldark in BBC One drama 'Poldark'. Fictional interpretations of the past should be rewarded, says the show’s historical adviser and historian Hannah Greig. (BBC/Adrian Rogers) In a podcast interview with History Extra, Poldark’s historical adviser, the historian Hannah Greig and Horrible Histories consultant Greg Jenner said dramatists should have the freedom to fictionally interpret the past.

“I don’t think dramatists need to be historians; I don’t think it’s their job,” said Jenner. “I think drama is there to entertain us. Dramatists are there to spellbind us, to make us laugh and cry and fear for our favourite characters.”

Hannah agreed: “In some ways the most important thing is to have great story. That has to be the priority. A historical adviser can help to drive that story forward, informed by what we know about the past, but Greg is probably right that we shouldn’t try to determine what that story is.”

Hannah continued: “The discussion of accuracy is something that crops up a lot on Twitter and in newspapers – it’s a way in which lots of [historical] dramas are judged. As a historian involved in the process I’m always asking myself ‘what does that mean? What are we trying to achieve by creating something that’s accurate?’ Because history is continually being made by new scholarship and by historians.

“So we can think about things being well informed by historical knowledge, but that’s not quite the same issue as ‘have they got everything right?’ And I’m not sure that the second part of that is particularly helpful – ‘oh, is that the exactly the right piece of clothing; is that the perfect period-precise room?’

“For me what’s important are ‘is the narrative meaningful for the time in which it’s set? Are the characters’ motivations informed by the choices that I would understand as being the choices that were faced by the people at the time? Does it carry me emotionally in the way that I might think about the historical past?’

“Those are the issues that really matter to me as a historian, and less so about whether we’ve sourced exactly the right wine glass”.

Drawing a distinction between historical dramas, Greg said: “I tend to think there are different categories for history on television as drama: you have the actual historical events that happened and you’re trying to dramatise those – I think that’s where perhaps there’s more of a burden to get it right or at least be pretty respectful of the truth – or what you think is the truth. And then you have the literary adaptations or the entirely fictional where you invent historical scenarios. For example, Poldark is a literary adaptation from the 1940s.

“So if you’re making a drama about, say the Titanic or the First World War – something where real lives were lost or real stories were felt, where there’s that potency of the real human story – I think then perhaps that’s when there is more of a responsibility to be at least engaging with history.”

Hannah agreed: “Poldark is adapted from a novel so in some ways the burden of responsibility for the production is to make sure that it’s as close an adaptation of that novel as possible. Whereas the Victoria series [on ITV] is about a British monarch, so there’s a responsibility there with the history to ensure that that is a fair interpretation of those real and incredibly important characters in the British past and to tell that history in a significant and informed way.”

Greg went on to say: “History doesn’t fall into three-act structures. Life is complex and difficult to dramatise in such a simplistic ways. Stories have to have very rigid structures and I’m not sure history fits that well sometimes into those structures”.

Hannah agreed: “I think there should be space for us to acknowledge and reward fictional interpretations [of the past] more. I think if we continually have the conversation of accuracy and ‘everything must be accurate’ then it weighs down dramas to become less creative”.

To listen to the podcast interview in full, click here.

Published on September 17, 2016 03:00

September 16, 2016

Unraveling the Mystery of the Great Pyramid Air-Shafts – Part II

Ancient Origins

The Design There are two air shafts each going out towards the North and the South direction in both King’s and Queen’s chamber. While, the King’s Chamber shafts go all the way to the external surface of the pyramid, out in the open, the Queen’ Chamber shafts are blocked some distance from the external surface. One of the reasons given is that the Queen’s Chamber was initially going to be the where Khufu would be interred but when the plan was changed to move the burial to what is the King’s Chamber, the shafts were blocked and their openings at the Queen’s Chamber were closed and sealed.

The Design There are two air shafts each going out towards the North and the South direction in both King’s and Queen’s chamber. While, the King’s Chamber shafts go all the way to the external surface of the pyramid, out in the open, the Queen’ Chamber shafts are blocked some distance from the external surface. One of the reasons given is that the Queen’s Chamber was initially going to be the where Khufu would be interred but when the plan was changed to move the burial to what is the King’s Chamber, the shafts were blocked and their openings at the Queen’s Chamber were closed and sealed.

Transparent view of Khufu's pyramid from SouthEast. (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)The shafts in the Queen’s Chamber have been up for much speculation. In 1992, an exploratory expedition into the shafts of the Queen’s Chamber was conducted by German engineer Rudolf Gatenbrink via a robotic explorer named after the ancient Egyptian god of war “Wepwawet” or alternatively called “Upuaut”. The robotic explorer found a number of artificial items in the Queen’s Chamber northern shaft such as a hexagonal iron rod with threaded end, indicating it was more recent in history, perhaps left behind by discoverers of the shafts Dixon and others. Other items found were a green grappling hook, a small grey green stone ball and a broken off piece of square wooden slat.

Transparent view of Khufu's pyramid from SouthEast. (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)The shafts in the Queen’s Chamber have been up for much speculation. In 1992, an exploratory expedition into the shafts of the Queen’s Chamber was conducted by German engineer Rudolf Gatenbrink via a robotic explorer named after the ancient Egyptian god of war “Wepwawet” or alternatively called “Upuaut”. The robotic explorer found a number of artificial items in the Queen’s Chamber northern shaft such as a hexagonal iron rod with threaded end, indicating it was more recent in history, perhaps left behind by discoverers of the shafts Dixon and others. Other items found were a green grappling hook, a small grey green stone ball and a broken off piece of square wooden slat.

Wepwawet giving scepters to Seti I, found at Temple of Seti I. Wepwawet is often depicted as a bluish or grayish haired wolf or jackal to avoid confusion with Anubis. (Roland Unger /

CC BY-SA 3.0

)The Measurements The openings of the shafts in the Queen’s Chamber have the same measurements with regards to height and depth of 21 by 21 centimeters or 8.4 inches by 8.4 inches. Flinders Petrie determined the angles of the northern and the southern shaft, using a goniometer, with northern shaft having a mean angle of 37 ° 28’ and that of the southern shaft having a mean angle 38 ° 28’. The northern shaft runs 190 centimeters or 76 inches horizontally before it turns upwards, similarly the southern shaft runs for 200 centimeters or 80 inches horizontally before turning up. The southern shaft goes up to 208.66 feet and is blocked by a limestone slate fitted with copper handles on both obverse and reverse sides with a confirmed thickness of 60 mm. “The floors of the shafts are made of flat limestone blocks, the thicknesses of which are unknown. The walls and ceilings are formed by sections of inverted u-blocks that resemble upside down gutters. Although it is uncertain what the blocks above and below the shafts look like, the shafts run at a sloping angle through the horizontal layers of the pyramid, so it is believed that the u-blocks and basal blocks rest under and on blocks that are wedge-shaped.”

Wepwawet giving scepters to Seti I, found at Temple of Seti I. Wepwawet is often depicted as a bluish or grayish haired wolf or jackal to avoid confusion with Anubis. (Roland Unger /

CC BY-SA 3.0

)The Measurements The openings of the shafts in the Queen’s Chamber have the same measurements with regards to height and depth of 21 by 21 centimeters or 8.4 inches by 8.4 inches. Flinders Petrie determined the angles of the northern and the southern shaft, using a goniometer, with northern shaft having a mean angle of 37 ° 28’ and that of the southern shaft having a mean angle 38 ° 28’. The northern shaft runs 190 centimeters or 76 inches horizontally before it turns upwards, similarly the southern shaft runs for 200 centimeters or 80 inches horizontally before turning up. The southern shaft goes up to 208.66 feet and is blocked by a limestone slate fitted with copper handles on both obverse and reverse sides with a confirmed thickness of 60 mm. “The floors of the shafts are made of flat limestone blocks, the thicknesses of which are unknown. The walls and ceilings are formed by sections of inverted u-blocks that resemble upside down gutters. Although it is uncertain what the blocks above and below the shafts look like, the shafts run at a sloping angle through the horizontal layers of the pyramid, so it is believed that the u-blocks and basal blocks rest under and on blocks that are wedge-shaped.”

Opening to the King’s Chamber shaft. Morton Edgar, 1910. (

Public Domain

) Almost a decade after the ambitious “Upuaut” rover project, in 2002, the much hyped “Pyramid Rover” sojourn took place. Unlike the Upuaut rover, the Pyramid Rover was equipped with a drill bit and a camera. After a laborious climb of about 45 minutes, the rendezvous between the rover the limestone slab happened. This whole program was being broadcast live across the world with audience sitting in front of their televisions, waiting with bated breath, while the rover drilled a hole in the limestone slab. Once this was done, the camera was inserted and all that was to be seen was a recess blocked by another slab of unknown proportion and thickness. While the audience were disappointed, for the experts, the seemingly uninteresting view was encouraging. The Queen chamber’s northern shaft was also explored for the first time and it was reported “The ‘door’ appears to be identical to the one in the southern shaft that was already known. The doors are equidistant (65 meters/208 feet) from the queen's chamber. It is the third such block discovered within the shafts of the pyramid.”

Opening to the King’s Chamber shaft. Morton Edgar, 1910. (

Public Domain

) Almost a decade after the ambitious “Upuaut” rover project, in 2002, the much hyped “Pyramid Rover” sojourn took place. Unlike the Upuaut rover, the Pyramid Rover was equipped with a drill bit and a camera. After a laborious climb of about 45 minutes, the rendezvous between the rover the limestone slab happened. This whole program was being broadcast live across the world with audience sitting in front of their televisions, waiting with bated breath, while the rover drilled a hole in the limestone slab. Once this was done, the camera was inserted and all that was to be seen was a recess blocked by another slab of unknown proportion and thickness. While the audience were disappointed, for the experts, the seemingly uninteresting view was encouraging. The Queen chamber’s northern shaft was also explored for the first time and it was reported “The ‘door’ appears to be identical to the one in the southern shaft that was already known. The doors are equidistant (65 meters/208 feet) from the queen's chamber. It is the third such block discovered within the shafts of the pyramid.”

The Great Pyramid of Giza as a monument of creation - Part 1: Earth Mathematical Encoding in the Great Pyramid Giza, The Time Keeper of the Ages: Alignments, Measurements, and Moon Cycles Then almost nine years later in 2011, the Djedi rover project was launched, which was a better designed robotic explorer, suitable to move in tighter confines of the southern shaft, given its articulate frame and its ability to expand and contract. The Dejdi rover was also equipped with a camera connected via a snake mount with the ability to bend and “see” behind itself. The project made discoveries such as, it imaged, in passing, what appeared to be workmen’s graffiti or glyphs of unknown meaning. It imaged the reverse side of the first blocking limestone plate, named “Gantenbrink’s Door”.

Gantenbrink’s Door. (

Image Source

)It discovered that the fractures on the roof of the shaft ran above the limestone plate and to the other side behind it. The camera also photographed some quarry marks left behind by workmen, “that have not been seen for 4500 years.”

Gantenbrink’s Door. (

Image Source

)It discovered that the fractures on the roof of the shaft ran above the limestone plate and to the other side behind it. The camera also photographed some quarry marks left behind by workmen, “that have not been seen for 4500 years.”

The Purpose Ever since the shafts were cleared of debris and the shafts in the Queen’s Chamber were discovered, claims as to the very nature and purpose of the shafts have remained dubious at best. Unfortunately, no contemporary text or evidence exists from the Khufu’s time that could explain this architectural anomaly. Like many other features in the great pyramid have baffled archaeologists, architects and engineers, the shafts continue mete out the same treatment to anyone who tries to study and interpret their function, symbolism and purpose.

Queens Pyramids and the Zep Tepi: Primary Planning During the Apex of the Golden Age Ritual Chambers of the Andes: Used in Secret, Near Death Simulations 36,400 BC: The Historical time of the Zep Tepi Theory The shafts were called “air channels” by earlier explorers such as Howard-Vyse, Piazzi Smyth and Flinders Petrie, who thought that these shafts were primitive climate control systems. Another known Egyptologist, Mark Lehner, has stated that these shafts were “gateways” to the stars, to guide the deceased king’s “Ka”. Rudolf Gantenbrink, the inventor and owner of Upuaut rover, rejects the notions of shafts being “air channels” or “gateways” to the stars. The dead have no need for proper air ventilation and the sky is not visible through the shafts from the King’s chamber so they cannot serve their purpose as gateways to the sky and the very fact that other pyramids (both preceding and succeeding the Great Pyramid) lack such shafts, casts shadows over the religious belief theory. Since the Great Pyramid has been stripped of its casing stone, it is not possible to ascertain whether the casing stone blocked the King’s Chamber shafts.

Then there are hundreds of other theories that make fantastic claims fantastic claims of shafts being conduits of power plant, a nuclear generator or an alien construction, a riddle set in stone. Until we discover an edict, a piece of papyrus that could explain the reason behind the shafts, the all theories about their purpose shall remain valid opinions of the experts and it is quite certain we may never be able to get to know their true purpose.

--

Top Image: Great Pyramid of Giza in the rays of the sun. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

By Rudra

The Design There are two air shafts each going out towards the North and the South direction in both King’s and Queen’s chamber. While, the King’s Chamber shafts go all the way to the external surface of the pyramid, out in the open, the Queen’ Chamber shafts are blocked some distance from the external surface. One of the reasons given is that the Queen’s Chamber was initially going to be the where Khufu would be interred but when the plan was changed to move the burial to what is the King’s Chamber, the shafts were blocked and their openings at the Queen’s Chamber were closed and sealed.

The Design There are two air shafts each going out towards the North and the South direction in both King’s and Queen’s chamber. While, the King’s Chamber shafts go all the way to the external surface of the pyramid, out in the open, the Queen’ Chamber shafts are blocked some distance from the external surface. One of the reasons given is that the Queen’s Chamber was initially going to be the where Khufu would be interred but when the plan was changed to move the burial to what is the King’s Chamber, the shafts were blocked and their openings at the Queen’s Chamber were closed and sealed.  Transparent view of Khufu's pyramid from SouthEast. (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)The shafts in the Queen’s Chamber have been up for much speculation. In 1992, an exploratory expedition into the shafts of the Queen’s Chamber was conducted by German engineer Rudolf Gatenbrink via a robotic explorer named after the ancient Egyptian god of war “Wepwawet” or alternatively called “Upuaut”. The robotic explorer found a number of artificial items in the Queen’s Chamber northern shaft such as a hexagonal iron rod with threaded end, indicating it was more recent in history, perhaps left behind by discoverers of the shafts Dixon and others. Other items found were a green grappling hook, a small grey green stone ball and a broken off piece of square wooden slat.

Transparent view of Khufu's pyramid from SouthEast. (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)The shafts in the Queen’s Chamber have been up for much speculation. In 1992, an exploratory expedition into the shafts of the Queen’s Chamber was conducted by German engineer Rudolf Gatenbrink via a robotic explorer named after the ancient Egyptian god of war “Wepwawet” or alternatively called “Upuaut”. The robotic explorer found a number of artificial items in the Queen’s Chamber northern shaft such as a hexagonal iron rod with threaded end, indicating it was more recent in history, perhaps left behind by discoverers of the shafts Dixon and others. Other items found were a green grappling hook, a small grey green stone ball and a broken off piece of square wooden slat.  Wepwawet giving scepters to Seti I, found at Temple of Seti I. Wepwawet is often depicted as a bluish or grayish haired wolf or jackal to avoid confusion with Anubis. (Roland Unger /

CC BY-SA 3.0

)The Measurements The openings of the shafts in the Queen’s Chamber have the same measurements with regards to height and depth of 21 by 21 centimeters or 8.4 inches by 8.4 inches. Flinders Petrie determined the angles of the northern and the southern shaft, using a goniometer, with northern shaft having a mean angle of 37 ° 28’ and that of the southern shaft having a mean angle 38 ° 28’. The northern shaft runs 190 centimeters or 76 inches horizontally before it turns upwards, similarly the southern shaft runs for 200 centimeters or 80 inches horizontally before turning up. The southern shaft goes up to 208.66 feet and is blocked by a limestone slate fitted with copper handles on both obverse and reverse sides with a confirmed thickness of 60 mm. “The floors of the shafts are made of flat limestone blocks, the thicknesses of which are unknown. The walls and ceilings are formed by sections of inverted u-blocks that resemble upside down gutters. Although it is uncertain what the blocks above and below the shafts look like, the shafts run at a sloping angle through the horizontal layers of the pyramid, so it is believed that the u-blocks and basal blocks rest under and on blocks that are wedge-shaped.”

Wepwawet giving scepters to Seti I, found at Temple of Seti I. Wepwawet is often depicted as a bluish or grayish haired wolf or jackal to avoid confusion with Anubis. (Roland Unger /

CC BY-SA 3.0