MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 85

August 23, 2016

Remnants of Gigantic Wooden Henge Found Two Miles from Stonehenge

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists carrying out excavations at the Durrington Walls earthworks, just two miles from the world-famous stone circle of Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England, have discovered evidence of an enormous 500-meter diameter circle of timber posts. Experts have said the finding is of international significance.

In a world exclusive, The Independent has revealed that the newly-discovered wooden henge at Durrington Walls consisted of 200-300 timber posts measuring 6-7 meters in height and 60 – 70 centimeters in diameter. The posts were buried in 1.5-meter-deep holes, two of which have been fully excavated so far.

The discovery was made just two miles from the world-famous stone circle of Stonehenge (

public domain

)Durrington Walls is the name given to a giant earthwork measuring around 1,640 feet (500 meters) in diameter and surrounded by a ditch of up to 54ft (16 meters) wide and a bank of more than three foot (1 meter) high. It is built on the same summer solstice alignment as Stonehenge. The enormous structure is believed to have formed a gigantic ceremonial complex in the Stonehenge landscape.

The discovery was made just two miles from the world-famous stone circle of Stonehenge (

public domain

)Durrington Walls is the name given to a giant earthwork measuring around 1,640 feet (500 meters) in diameter and surrounded by a ditch of up to 54ft (16 meters) wide and a bank of more than three foot (1 meter) high. It is built on the same summer solstice alignment as Stonehenge. The enormous structure is believed to have formed a gigantic ceremonial complex in the Stonehenge landscape.

The most intriguing aspect of the finding is that the construction of the wooden circle stopped abruptly before it was finished, around 2460 BC. The posts were removed from the holes, which were then filled in with blocks of chalk and then covered by a bank made of chalk rubble. In the bottom of one of the excavated post holes, archaeologists found a spade made from a cow’s shoulder blade.

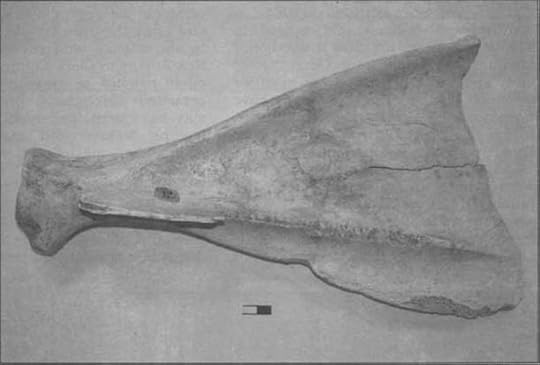

A tool made from a bison shoulder blade, which would be similar to the spade found in the bottom of one of the post holes. (

foresthistory.org

)According to The Independent, researchers believe this sudden cessation in construction is indicative of a dramatic change in religious and/or political direction, possibly due to the arrival in Britain around this time of the Beaker culture (2800 – 1800 BC). The Beaker culture is thought to have originated in either the Iberian Peninsula, the Netherlands or Central Europe and subsequently spread out across Western Europe. They are known for a particular pottery type they developed, but also a complex cultural phenomenon involving shared ideological, cultural and religious ideas.

A tool made from a bison shoulder blade, which would be similar to the spade found in the bottom of one of the post holes. (

foresthistory.org

)According to The Independent, researchers believe this sudden cessation in construction is indicative of a dramatic change in religious and/or political direction, possibly due to the arrival in Britain around this time of the Beaker culture (2800 – 1800 BC). The Beaker culture is thought to have originated in either the Iberian Peninsula, the Netherlands or Central Europe and subsequently spread out across Western Europe. They are known for a particular pottery type they developed, but also a complex cultural phenomenon involving shared ideological, cultural and religious ideas.

The distinctive Bell Beaker pottery drinking vessels shaped like an inverted bell (

public domain

)“It was as if the religious "revolutionaries" were trying, quite literally, to bury the past,” reports The Independent. “The question archaeologists will now seek to answer is whether it was the revolutionaries’ own past they were seeking to bury – or whether it was another group or cultural tradition’s past that was being consigned to the dustbin of prehistory.”

The distinctive Bell Beaker pottery drinking vessels shaped like an inverted bell (

public domain

)“It was as if the religious "revolutionaries" were trying, quite literally, to bury the past,” reports The Independent. “The question archaeologists will now seek to answer is whether it was the revolutionaries’ own past they were seeking to bury – or whether it was another group or cultural tradition’s past that was being consigned to the dustbin of prehistory.”

“The new discoveries at Durrington Walls reveal the previously unsuspected complexity of events in the area during the period when Stonehenge’s largest stones were being erected – and show just how politically and ideologically dynamic British society was at that particularly crucial stage in prehistory,” said Dr Nick Snashall, the senior National Trust archaeologist for the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site [via The Independent].

Top image: Main: An aerial photograph of Durrington Walls. In the North, West and South, a line of trees handily outlines the shape of the bank, a faint impression can be seen in the East, however, to the right of the road. The River Avon, and the area where the avenue connected it to Durrington Walls, can be seen in the bottom-right ( pegasusarchive.org ). Inset: An illustration of a similar wooden henge located at Cairnpapple Hill, Scotland .

By April Holloway

By April Holloway

Archaeologists carrying out excavations at the Durrington Walls earthworks, just two miles from the world-famous stone circle of Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England, have discovered evidence of an enormous 500-meter diameter circle of timber posts. Experts have said the finding is of international significance.

In a world exclusive, The Independent has revealed that the newly-discovered wooden henge at Durrington Walls consisted of 200-300 timber posts measuring 6-7 meters in height and 60 – 70 centimeters in diameter. The posts were buried in 1.5-meter-deep holes, two of which have been fully excavated so far.

The discovery was made just two miles from the world-famous stone circle of Stonehenge (

public domain

)Durrington Walls is the name given to a giant earthwork measuring around 1,640 feet (500 meters) in diameter and surrounded by a ditch of up to 54ft (16 meters) wide and a bank of more than three foot (1 meter) high. It is built on the same summer solstice alignment as Stonehenge. The enormous structure is believed to have formed a gigantic ceremonial complex in the Stonehenge landscape.

The discovery was made just two miles from the world-famous stone circle of Stonehenge (

public domain

)Durrington Walls is the name given to a giant earthwork measuring around 1,640 feet (500 meters) in diameter and surrounded by a ditch of up to 54ft (16 meters) wide and a bank of more than three foot (1 meter) high. It is built on the same summer solstice alignment as Stonehenge. The enormous structure is believed to have formed a gigantic ceremonial complex in the Stonehenge landscape.The most intriguing aspect of the finding is that the construction of the wooden circle stopped abruptly before it was finished, around 2460 BC. The posts were removed from the holes, which were then filled in with blocks of chalk and then covered by a bank made of chalk rubble. In the bottom of one of the excavated post holes, archaeologists found a spade made from a cow’s shoulder blade.

A tool made from a bison shoulder blade, which would be similar to the spade found in the bottom of one of the post holes. (

foresthistory.org

)According to The Independent, researchers believe this sudden cessation in construction is indicative of a dramatic change in religious and/or political direction, possibly due to the arrival in Britain around this time of the Beaker culture (2800 – 1800 BC). The Beaker culture is thought to have originated in either the Iberian Peninsula, the Netherlands or Central Europe and subsequently spread out across Western Europe. They are known for a particular pottery type they developed, but also a complex cultural phenomenon involving shared ideological, cultural and religious ideas.

A tool made from a bison shoulder blade, which would be similar to the spade found in the bottom of one of the post holes. (

foresthistory.org

)According to The Independent, researchers believe this sudden cessation in construction is indicative of a dramatic change in religious and/or political direction, possibly due to the arrival in Britain around this time of the Beaker culture (2800 – 1800 BC). The Beaker culture is thought to have originated in either the Iberian Peninsula, the Netherlands or Central Europe and subsequently spread out across Western Europe. They are known for a particular pottery type they developed, but also a complex cultural phenomenon involving shared ideological, cultural and religious ideas. The distinctive Bell Beaker pottery drinking vessels shaped like an inverted bell (

public domain

)“It was as if the religious "revolutionaries" were trying, quite literally, to bury the past,” reports The Independent. “The question archaeologists will now seek to answer is whether it was the revolutionaries’ own past they were seeking to bury – or whether it was another group or cultural tradition’s past that was being consigned to the dustbin of prehistory.”

The distinctive Bell Beaker pottery drinking vessels shaped like an inverted bell (

public domain

)“It was as if the religious "revolutionaries" were trying, quite literally, to bury the past,” reports The Independent. “The question archaeologists will now seek to answer is whether it was the revolutionaries’ own past they were seeking to bury – or whether it was another group or cultural tradition’s past that was being consigned to the dustbin of prehistory.”“The new discoveries at Durrington Walls reveal the previously unsuspected complexity of events in the area during the period when Stonehenge’s largest stones were being erected – and show just how politically and ideologically dynamic British society was at that particularly crucial stage in prehistory,” said Dr Nick Snashall, the senior National Trust archaeologist for the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site [via The Independent].

Top image: Main: An aerial photograph of Durrington Walls. In the North, West and South, a line of trees handily outlines the shape of the bank, a faint impression can be seen in the East, however, to the right of the road. The River Avon, and the area where the avenue connected it to Durrington Walls, can be seen in the bottom-right ( pegasusarchive.org ). Inset: An illustration of a similar wooden henge located at Cairnpapple Hill, Scotland .

By April Holloway

By April Holloway

Published on August 23, 2016 03:00

August 22, 2016

Q&A: When did Italian replace Latin as the language of Italy?

History Extra

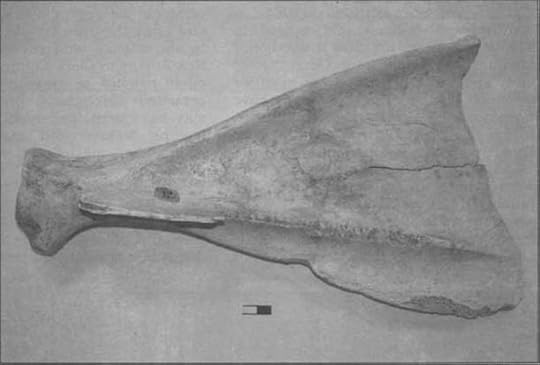

Venice in 1338. (Bridgeman Art Library)

Venice in 1338. (Bridgeman Art Library) Languages can literally die overnight when the last of their speakers dies, but the death of Latin was very different. After the fall of the Roman empire in the west in AD 476, Latin evolved into a wide variety of regional dialects now known as Romance vernaculars. In the early 14th century the Florentine poet Dante Alighieri reckoned that more than 1,000 such dialects were spoken in Italy. At the time of Dante, Latin was still used in literature, philosophy, medicine and other cultural or legal written documents. Dialects were spoken, but also used in writing: the earliest examples of vernacular writing in Italy date from the ninth century. The early 16th century saw the dialect used by Dante in his work replace Latin as the language of culture. We can thus say that modern Italian descends from 14th-century literary Florentine. Italy did not become a single nation until 1861, at which time less than 10 per cent of its citizens spoke the national language, Italian. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, Italy was a ‘diglossic country’ – one where a local dialect such as Neapolitan or Milanese was spoken at home while Italian was learned at school and used for official purposes. The First World War helped foster linguistic unification when, for the first time, soldiers from all over Italy met and talked to each other. The rise in literacy levels after the Second World War and the spread of mass media changed Italy into a bilingual nation, where Italian, increasingly the mother tongue of all Italians, coexists and interacts with the dialects of Italy.

Answered by Delia Bentley, senior lecturer at the University of Manchester.

Published on August 22, 2016 03:00

August 21, 2016

The hunt for the Tudor hitman

History Extra

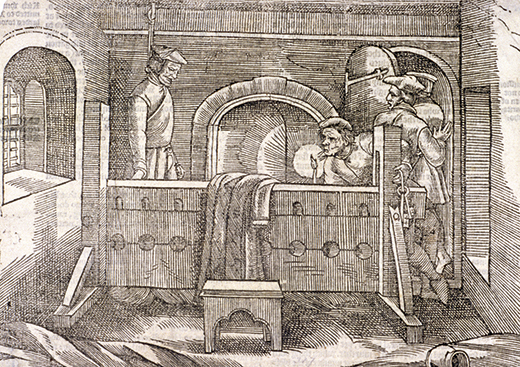

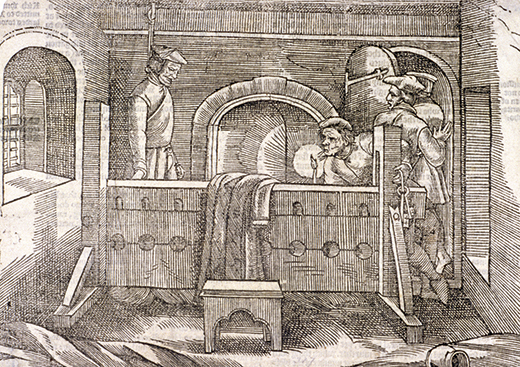

A contemporary illustration shows a man firing a gun. In 1530s England, the arquebus was the only firearm in general use – yet it was way too cumbersome to be the weapon employed in Robert Packington’s murder. © Mercer's Company

At around 6am on Monday 13 November 1536, Robert Packington left his house in London’s Cheapside – or just around the corner in Sopers Lane – to attend early Mass in the Mercers’ Chapel on the north side of West Cheap. His journey was a short one but, in all likelihood, Packington carried a lantern: the night was dark and smoke from a thousand chimneys, mingling with a mist from the Thames, reduced visibility to a few paces.

Packington’s route took him past the Great Conduit, a square building in the middle of Cheapside containing the fountain that provided the nearby houses with their water supply. As he crossed the thoroughfare, only a few metres from his destination, a single shot rang out and he fell dead upon the instant.

Almost as soon as Packington’s body hit the floor, the crowd that rapidly gathered around his corpse was asking questions. Why would someone want to eliminate one of London’s most respectable figures – Packington was not only a prominent merchant, and a leading light in the Worshipful Mercers’ Company, but also a member of parliament. Why did the assassin select such a busy part of London – a daily gathering point for unemployed men hoping to be hired as day labourers – to commit the crime?

And why did no one notice the gunman or his weapon? The only firearms in general use at the time were matchlock arquebuses – and these were hardly tailor-made for assassins wishing to carry out a swift, surgical strike. Arquebuses were more than a metre long and had to be held using both hands. The powder was ignited by means of a glowing match which would show up in the dark.

Even in the gloom of that November pre-dawn, anyone carrying, let alone using, such an unwieldy firearm would have attracted attention. Yet this assassin, apparently, stood a mere matter of yards from a crowd, put the gun to his shoulder, and pulled the trigger. There was a flash and an explosion. And yet no one saw him.

A wheellock pistol, the lethal new weapon used in a 1536 killing that seemed to be a professional 'hit'. © Bridgeman

The reason that the murderer was able to melt into the darkness was, as it transpires, that he wasn’t using an arquebus at all, but the much smaller, more discreet wheellock pistol. In fact, poor Robert Packington probably holds the dubious distinction of being the first person in England to be killed with a handgun.

By the time the autumn sun had dispelled the early mist, the shocking news of the merchant’s murder was all over town. And, by now, one more question was on everyone’s lips – and, four days later, that question was still unanswered. Writing to his master, Viscount Lisle, in Calais, Francis Hall reported: “The murderer that slew Mr Packington with a gun in Cheapside cannot be yet known.” Despite the offer of a large reward by the lord mayor, no one was brought to book for the crime.

But this did not mean that there were no suspicions. John Bale, the Protestant controversialist, writing a decade later, was sure that the instigators of the killing were the Catholic bishops – the “byfurked ordinaries”. Soon Edward Hall’s history of England from the reigns of Henry IV to Henry VIII – the Union of the Two Illustre Families of Lancaster and York (commonly called Hall’s Chronicle) – was on the bookstalls, containing a more detailed account of the incident. It added that because Packington had denounced “the covetousness and cruelty of the clergy” it was most likely that “by one of them [he was] thus shamefully murdered”.

Cruelty of the clergyBy the time Foxe wrote his Acts and Monuments of the Christian Religion (commonly known as the Book of Martyrs – first Latin edition 1559) specific perpetrators were in the frame.

But before we come onto those, we should consider the background to the murder. The year 1536 was an annus horribilis, the most tense and turbulent of Henry VIII’s reign.

The first ominous event was the death, in January, of Catharine of Aragon, the former queen, still much loved by many of Henry’s subjects. Scarcely had the memory of her passing begun to fade when news came that the king’s second wife, Anne Boleyn, had been arrested and was going to be executed.

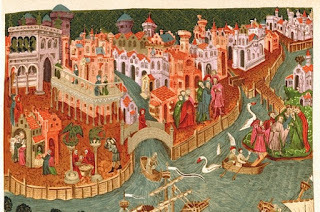

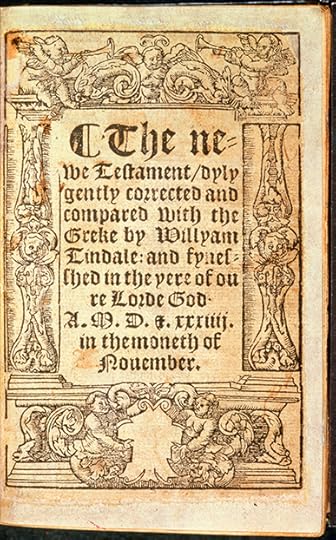

A copy of the New Testament translated into English by William Tyndale. Was Robert Packington targeted because he smuggled this banned text into England? © Bridgeman

Few mourned the death of the ‘French whore’ but many were troubled by the manner of her demise. The king had done so many terrible things, including making himself pope in England. What might he do next?

The answer was: begin dismantling the fabric of the nation’s religion by closing the smaller monasteries. Government preachers were put up in the pulpits to denounce Catholic practices. In response, bold spirits stood up in other churches to attack the ‘heretics’ now exercising power over the king – particularly Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s closest adviser, and archbishop Thomas Cranmer.

A rabid pamphlet war broke out between traditionalist and reformist parties. Neighbour accused neighbour of being a ‘papist’ or a ‘heretic’. There was widespread fear that insults would give way to violence. Cromwell even ordered that all priests must surrender any weapons they possessed.

Then, in October, the looming storm broke. News reached London that men in the Midlands and the north had risen in revolt against religious change and would soon be marching south. Henry and his court shut themselves up in Windsor Castle. Citizens feared that blood would soon be running in their streets. And so it was.

But why was it Robert Packington’s? A clue surely lies in the fact that he was a senior member of the Mercers’ Company, had studied at the Inns of Court and regularly sat at the House of Commons.

Now, if any Londoners resented the power of the clergy, it was the city’s merchants, lawyers and parliamentarians. Packington was an outspoken critic. But, in all probability, he was more – an evangelical activist engaged in smuggling William Tyndale’s banned translation of the New Testament and other heretical books into England. He was also, it seems, an associate of Cromwell, and carried messages between the minister and evangelical activists in Antwerp.

So, when Packington was brutally murdered few people were in any doubt that he was a victim of Catholic reactionaries, and that his death was a shot across Protestant bows fired by the senior clergy or even the bishop of London himself, John Stokesley.

John Foxe went a stage further in his Acts and Monuments of the Christian Religion. Stokesley, he averred, had paid someone 60 gold coins to undertake the murder. However, in his 1570 edition of the book, Foxe changed the name of the instigator. Now, he identified John Incent, canon of St Paul’s (and later dean), as the paymaster – a crime to which Incent had allegedly confessed on his deathbed in 1545. The actual hitman was now identified as an Italian.

To confuse the issue yet further, Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577) attributed the crime to an unnamed felon subsequently hanged at Banbury for an unrelated offence. Can we, 478 years later, make any sense of the conflicting evidence?

The attack has all the hallmarks of a professional ‘hit’. The weapon, the location, the timing all indicate a carefully planned assassination.

Hitmen do not come cheap. The early reports of a considerable fee having been paid certainly make sense. If the villain who actually pulled the trigger was the one who later paid for his crime at Banbury, we are left with two suspects as possible instigators of the atrocity. Foxe was – eventually – convinced about Incent’s deathbed confession. It was, he declared, attested “by men both of great credit and worshipful estimation”.

Dean John Incent allegedly confessed to the murder on his deathbed. © Getty Images

But was this middle-ranking priest capable of thinking up and putting into operation a cold-blooded murder?

Time, perhaps, for a little psychological profiling. Incent was a conservative and given to ecclesiastical in-fighting with more evangelically minded colleagues. But he had no reputation as a persecutor and he did not allow mere theology to stand in the way of his promotion: later he was one of the commissioners sent by Cromwell to dissolve monasteries. Moreover, if Incent believed that Packington was a dangerous heretic, why would his conscience be troubled about ridding the world of him?

Bishop Stokesley was a horse of a very different colour. He already had blood on his hands and actually boasted of having consigned over 30 heretics to the flames. He openly quarrelled with Cromwell and was particularly opposed to the minister’s pet project of promoting an English Bible. He was active in hunting down William Tyndale and having him arrested in Antwerp. The translator was burned as a heretic just five weeks before Packington’s death.

Here, I think, we may be at the crux of the matter. Stokesley believed passionately that the vernacular Bible should not be available in England. For years he had been fighting a losing battle against the illegal import of Tyndale’s New Testament. Anger and frustration could well have driven him to extreme measures. The bishop was clever enough, rich enough, powerful enough and ruthless enough to organise an attack on a Bible smuggler who was a confidant of that loathsome creature, Thomas Cromwell. Perhaps Foxe’s first impression was correct.

But then, what are we to make of Incent’s confession? Well, we are not obliged to believe that Stokesley acted alone. On the contrary, he would have needed trusted accomplices to help fine-tune the crime. If Incent was a mere sidekick who had supported his bishop’s plan to murder a prominent London citizen, he might well have felt the need to cleanse his soul before it followed that of Robert Packington into the presence of the Great Judge.

The assassin's weapon of choice

The pistol that killed Robert Packington made Europe's rulers decidely jumpy

The one fact mentioned in every early account of Robert Packington’s murder is that it was perpetrated “with a gun”. It was this that made the act shocking, cowardly and diabolical. The weapon referred to, and the only one that can have been used to kill Packington, was a wheellock pistol. Such a firearm was much shorter than an arquebus. It needed no lighted match because the powder was ignited by a spark struck from a flint. The weapon could be hidden beneath a cloak, brought out, fired one-handedly at close range, then as quickly concealed.

The wheellock introduced a new era of political assassination. Invented in the early 16th century, its potential was quickly recognised by European rulers. In 1518 the Holy Roman Emperor Maximillian I banned the manufacture and carrying of “self-igniting handguns that set themselves to firing”. Other heads of state were not slow to follow suit. By the 1530s wheellocks were still rare. They were complex and expensive pieces of kit carried by well-to-do, macho braggarts. Few people in London would ever have seen one. Small wonder that it was commonly believed that the murderer was a foreigner.

Did the clergy have form?

Those who held churchmen responsible for Packington's death were quick to call attention to a similar killing in 1514

An illustration shows the hanging of merchant Richard Hunne at St Paul’s Cathedral. © Robin Mcmorran

Shortly after Robert Packington was slain on the streets of Cheapside, stories began circulating of another killing in England’s capital 22 years earlier.

In early 1537 an anonymous pamphlet, printed in Antwerp, was being avidly read on the streets of London, telling how one Richard Hunne had been locked up in the Lollards’ Tower of St Paul’s Cathedral and brutally murdered.

The pamphlet was no mere Protestant diatribe. It made public for the first time the complete coroner’s report and named three henchmen of Richard Fitzjames, then bishop of London, who had “feloniously strangled and smothered, and also the neck they did break of the said Richard Hunne… afterward… with the same girdle of the same Richard Hunne… after his death, upon a hook driven into… the wall of the prison… and so hanged him”.

Why was the story of this sensational crime revived more than two decades later? Why did it arouse fresh interest at this particular time? Because Hunne, like Packington, was a prominent merchant (a member of the Merchant Taylors’ Company) and an outspoken critic of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. He too, so it was alleged, had been violently silenced at the behest of the clergy.

The timing of the publication was no coincidence, and readers could not help remarking upon the parallels between the two killings.

Derek Wilson is the author of The First Horseman, a novel based upon the Packington affair, written under the name DK Wilson.

els between the two killings.

written under the name DK Wilson.

A contemporary illustration shows a man firing a gun. In 1530s England, the arquebus was the only firearm in general use – yet it was way too cumbersome to be the weapon employed in Robert Packington’s murder. © Mercer's Company

At around 6am on Monday 13 November 1536, Robert Packington left his house in London’s Cheapside – or just around the corner in Sopers Lane – to attend early Mass in the Mercers’ Chapel on the north side of West Cheap. His journey was a short one but, in all likelihood, Packington carried a lantern: the night was dark and smoke from a thousand chimneys, mingling with a mist from the Thames, reduced visibility to a few paces.

Packington’s route took him past the Great Conduit, a square building in the middle of Cheapside containing the fountain that provided the nearby houses with their water supply. As he crossed the thoroughfare, only a few metres from his destination, a single shot rang out and he fell dead upon the instant.

Almost as soon as Packington’s body hit the floor, the crowd that rapidly gathered around his corpse was asking questions. Why would someone want to eliminate one of London’s most respectable figures – Packington was not only a prominent merchant, and a leading light in the Worshipful Mercers’ Company, but also a member of parliament. Why did the assassin select such a busy part of London – a daily gathering point for unemployed men hoping to be hired as day labourers – to commit the crime?

And why did no one notice the gunman or his weapon? The only firearms in general use at the time were matchlock arquebuses – and these were hardly tailor-made for assassins wishing to carry out a swift, surgical strike. Arquebuses were more than a metre long and had to be held using both hands. The powder was ignited by means of a glowing match which would show up in the dark.

Even in the gloom of that November pre-dawn, anyone carrying, let alone using, such an unwieldy firearm would have attracted attention. Yet this assassin, apparently, stood a mere matter of yards from a crowd, put the gun to his shoulder, and pulled the trigger. There was a flash and an explosion. And yet no one saw him.

A wheellock pistol, the lethal new weapon used in a 1536 killing that seemed to be a professional 'hit'. © Bridgeman

The reason that the murderer was able to melt into the darkness was, as it transpires, that he wasn’t using an arquebus at all, but the much smaller, more discreet wheellock pistol. In fact, poor Robert Packington probably holds the dubious distinction of being the first person in England to be killed with a handgun.

By the time the autumn sun had dispelled the early mist, the shocking news of the merchant’s murder was all over town. And, by now, one more question was on everyone’s lips – and, four days later, that question was still unanswered. Writing to his master, Viscount Lisle, in Calais, Francis Hall reported: “The murderer that slew Mr Packington with a gun in Cheapside cannot be yet known.” Despite the offer of a large reward by the lord mayor, no one was brought to book for the crime.

But this did not mean that there were no suspicions. John Bale, the Protestant controversialist, writing a decade later, was sure that the instigators of the killing were the Catholic bishops – the “byfurked ordinaries”. Soon Edward Hall’s history of England from the reigns of Henry IV to Henry VIII – the Union of the Two Illustre Families of Lancaster and York (commonly called Hall’s Chronicle) – was on the bookstalls, containing a more detailed account of the incident. It added that because Packington had denounced “the covetousness and cruelty of the clergy” it was most likely that “by one of them [he was] thus shamefully murdered”.

Cruelty of the clergyBy the time Foxe wrote his Acts and Monuments of the Christian Religion (commonly known as the Book of Martyrs – first Latin edition 1559) specific perpetrators were in the frame.

But before we come onto those, we should consider the background to the murder. The year 1536 was an annus horribilis, the most tense and turbulent of Henry VIII’s reign.

The first ominous event was the death, in January, of Catharine of Aragon, the former queen, still much loved by many of Henry’s subjects. Scarcely had the memory of her passing begun to fade when news came that the king’s second wife, Anne Boleyn, had been arrested and was going to be executed.

A copy of the New Testament translated into English by William Tyndale. Was Robert Packington targeted because he smuggled this banned text into England? © Bridgeman

Few mourned the death of the ‘French whore’ but many were troubled by the manner of her demise. The king had done so many terrible things, including making himself pope in England. What might he do next?

The answer was: begin dismantling the fabric of the nation’s religion by closing the smaller monasteries. Government preachers were put up in the pulpits to denounce Catholic practices. In response, bold spirits stood up in other churches to attack the ‘heretics’ now exercising power over the king – particularly Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s closest adviser, and archbishop Thomas Cranmer.

A rabid pamphlet war broke out between traditionalist and reformist parties. Neighbour accused neighbour of being a ‘papist’ or a ‘heretic’. There was widespread fear that insults would give way to violence. Cromwell even ordered that all priests must surrender any weapons they possessed.

Then, in October, the looming storm broke. News reached London that men in the Midlands and the north had risen in revolt against religious change and would soon be marching south. Henry and his court shut themselves up in Windsor Castle. Citizens feared that blood would soon be running in their streets. And so it was.

But why was it Robert Packington’s? A clue surely lies in the fact that he was a senior member of the Mercers’ Company, had studied at the Inns of Court and regularly sat at the House of Commons.

Now, if any Londoners resented the power of the clergy, it was the city’s merchants, lawyers and parliamentarians. Packington was an outspoken critic. But, in all probability, he was more – an evangelical activist engaged in smuggling William Tyndale’s banned translation of the New Testament and other heretical books into England. He was also, it seems, an associate of Cromwell, and carried messages between the minister and evangelical activists in Antwerp.

So, when Packington was brutally murdered few people were in any doubt that he was a victim of Catholic reactionaries, and that his death was a shot across Protestant bows fired by the senior clergy or even the bishop of London himself, John Stokesley.

John Foxe went a stage further in his Acts and Monuments of the Christian Religion. Stokesley, he averred, had paid someone 60 gold coins to undertake the murder. However, in his 1570 edition of the book, Foxe changed the name of the instigator. Now, he identified John Incent, canon of St Paul’s (and later dean), as the paymaster – a crime to which Incent had allegedly confessed on his deathbed in 1545. The actual hitman was now identified as an Italian.

To confuse the issue yet further, Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577) attributed the crime to an unnamed felon subsequently hanged at Banbury for an unrelated offence. Can we, 478 years later, make any sense of the conflicting evidence?

The attack has all the hallmarks of a professional ‘hit’. The weapon, the location, the timing all indicate a carefully planned assassination.

Hitmen do not come cheap. The early reports of a considerable fee having been paid certainly make sense. If the villain who actually pulled the trigger was the one who later paid for his crime at Banbury, we are left with two suspects as possible instigators of the atrocity. Foxe was – eventually – convinced about Incent’s deathbed confession. It was, he declared, attested “by men both of great credit and worshipful estimation”.

Dean John Incent allegedly confessed to the murder on his deathbed. © Getty Images

But was this middle-ranking priest capable of thinking up and putting into operation a cold-blooded murder?

Time, perhaps, for a little psychological profiling. Incent was a conservative and given to ecclesiastical in-fighting with more evangelically minded colleagues. But he had no reputation as a persecutor and he did not allow mere theology to stand in the way of his promotion: later he was one of the commissioners sent by Cromwell to dissolve monasteries. Moreover, if Incent believed that Packington was a dangerous heretic, why would his conscience be troubled about ridding the world of him?

Bishop Stokesley was a horse of a very different colour. He already had blood on his hands and actually boasted of having consigned over 30 heretics to the flames. He openly quarrelled with Cromwell and was particularly opposed to the minister’s pet project of promoting an English Bible. He was active in hunting down William Tyndale and having him arrested in Antwerp. The translator was burned as a heretic just five weeks before Packington’s death.

Here, I think, we may be at the crux of the matter. Stokesley believed passionately that the vernacular Bible should not be available in England. For years he had been fighting a losing battle against the illegal import of Tyndale’s New Testament. Anger and frustration could well have driven him to extreme measures. The bishop was clever enough, rich enough, powerful enough and ruthless enough to organise an attack on a Bible smuggler who was a confidant of that loathsome creature, Thomas Cromwell. Perhaps Foxe’s first impression was correct.

But then, what are we to make of Incent’s confession? Well, we are not obliged to believe that Stokesley acted alone. On the contrary, he would have needed trusted accomplices to help fine-tune the crime. If Incent was a mere sidekick who had supported his bishop’s plan to murder a prominent London citizen, he might well have felt the need to cleanse his soul before it followed that of Robert Packington into the presence of the Great Judge.

The assassin's weapon of choice

The pistol that killed Robert Packington made Europe's rulers decidely jumpy

The one fact mentioned in every early account of Robert Packington’s murder is that it was perpetrated “with a gun”. It was this that made the act shocking, cowardly and diabolical. The weapon referred to, and the only one that can have been used to kill Packington, was a wheellock pistol. Such a firearm was much shorter than an arquebus. It needed no lighted match because the powder was ignited by a spark struck from a flint. The weapon could be hidden beneath a cloak, brought out, fired one-handedly at close range, then as quickly concealed.

The wheellock introduced a new era of political assassination. Invented in the early 16th century, its potential was quickly recognised by European rulers. In 1518 the Holy Roman Emperor Maximillian I banned the manufacture and carrying of “self-igniting handguns that set themselves to firing”. Other heads of state were not slow to follow suit. By the 1530s wheellocks were still rare. They were complex and expensive pieces of kit carried by well-to-do, macho braggarts. Few people in London would ever have seen one. Small wonder that it was commonly believed that the murderer was a foreigner.

Did the clergy have form?

Those who held churchmen responsible for Packington's death were quick to call attention to a similar killing in 1514

An illustration shows the hanging of merchant Richard Hunne at St Paul’s Cathedral. © Robin Mcmorran

Shortly after Robert Packington was slain on the streets of Cheapside, stories began circulating of another killing in England’s capital 22 years earlier.

In early 1537 an anonymous pamphlet, printed in Antwerp, was being avidly read on the streets of London, telling how one Richard Hunne had been locked up in the Lollards’ Tower of St Paul’s Cathedral and brutally murdered.

The pamphlet was no mere Protestant diatribe. It made public for the first time the complete coroner’s report and named three henchmen of Richard Fitzjames, then bishop of London, who had “feloniously strangled and smothered, and also the neck they did break of the said Richard Hunne… afterward… with the same girdle of the same Richard Hunne… after his death, upon a hook driven into… the wall of the prison… and so hanged him”.

Why was the story of this sensational crime revived more than two decades later? Why did it arouse fresh interest at this particular time? Because Hunne, like Packington, was a prominent merchant (a member of the Merchant Taylors’ Company) and an outspoken critic of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. He too, so it was alleged, had been violently silenced at the behest of the clergy.

The timing of the publication was no coincidence, and readers could not help remarking upon the parallels between the two killings.

Derek Wilson is the author of The First Horseman, a novel based upon the Packington affair, written under the name DK Wilson.

els between the two killings.

written under the name DK Wilson.

Published on August 21, 2016 03:00

August 20, 2016

Paid Sick Days and Physicians at Work: Ancient Egyptians had State-Supported Health Care

Ancient Origins

We might think of state supported health care as an innovation of the 20th century, but it’s a much older tradition than that. In fact, texts from a village dating back to Egypt’s New Kingdom period, about 3,100-3,600 years ago, suggest that in ancient Egypt there was a state-supported health care network designed to ensure that workers making the king’s tomb were productive.

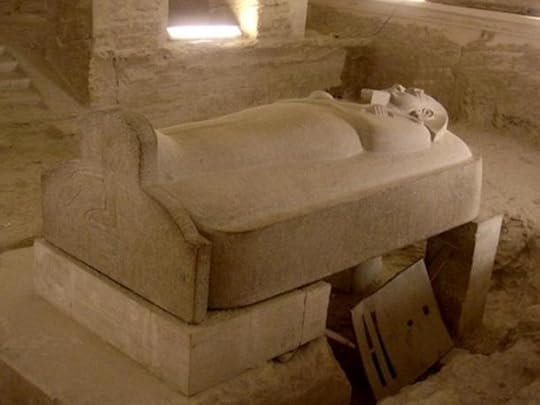

Health care boosted productivity on the royal tombsThe village of Deir el-Medina was built for the workmen who made the royal tombs during the New Kingdom (1550-1070 BCE). During this period, kings were buried in the Valley of the Kings in a series of rock-cut tombs, not the enormous pyramids of the past. The village was purposely built close enough to the royal tomb to ensure that workers could hike there on a weekly basis.

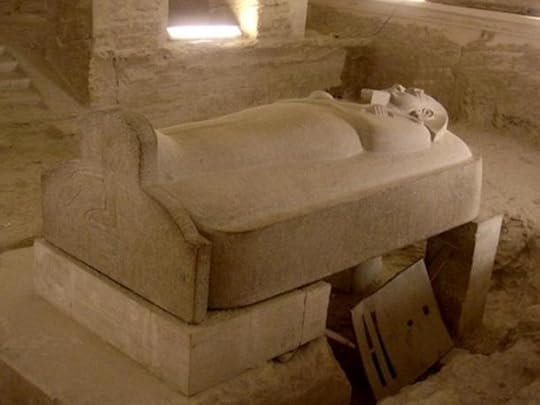

Stone sarcophagus of Merneptah in KV8. (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)These workmen were not what we normally picture when we think about the men who built and decorated ancient Egyptian royal tombs – they were highly skilled craftsmen. The workmen at Deir el-Medina were given a variety of amenities afforded only to those with the craftsmanship and knowledge necessary to work on something as important as the royal tomb.

Stone sarcophagus of Merneptah in KV8. (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)These workmen were not what we normally picture when we think about the men who built and decorated ancient Egyptian royal tombs – they were highly skilled craftsmen. The workmen at Deir el-Medina were given a variety of amenities afforded only to those with the craftsmanship and knowledge necessary to work on something as important as the royal tomb.

New study sheds light into ancient Egyptian health care system at Deir el-MedinaPolish Archaeologists Discover Rare Gift from Father of CleopatraThe village was allotted extra support: The Egyptian state paid them monthly wages in the form of grain and provided them with housing and servants to assist with tasks like washing laundry, grinding grain and porting water. Their families lived with them in the village, and their wives and children could also benefit from these provisions from the state.

Out sick? You’ll need a note Deir el-Medina, the place the workers called home. (

CC BY 3.0

)Among these texts are numerous daily records detailing when and why individual workmen were absent from work. Nearly one-third of these absences occur when a workman was too sick to work. Yet, monthly ration distributions from Deir el-Medina are consistent enough to indicate that these workmen were paid even if they were out sick for several days.

Deir el-Medina, the place the workers called home. (

CC BY 3.0

)Among these texts are numerous daily records detailing when and why individual workmen were absent from work. Nearly one-third of these absences occur when a workman was too sick to work. Yet, monthly ration distributions from Deir el-Medina are consistent enough to indicate that these workmen were paid even if they were out sick for several days.

These texts also identify a workman on the crew designated as the swnw, physician. The physician was given an assistant and both were allotted days off to prepare medicine and take care of colleagues. The Egyptian state even gave the physician extra rations as payment for his services to the community of Deir el-Medina.

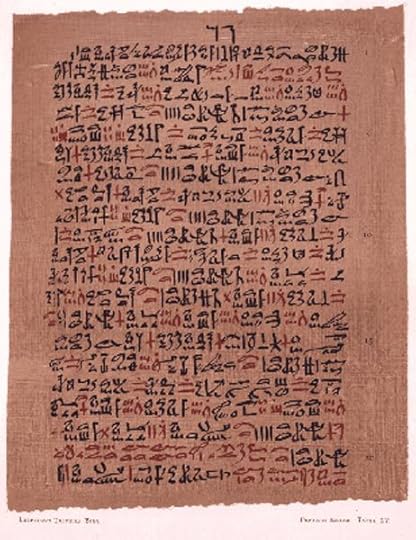

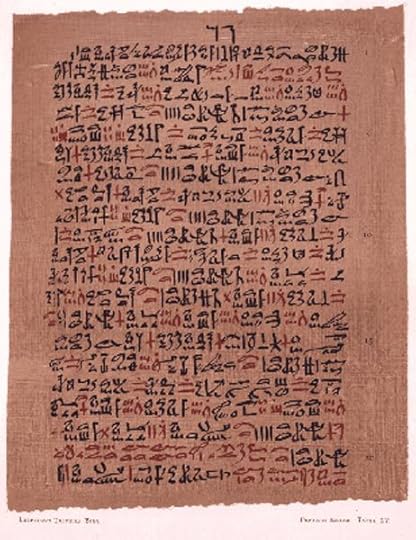

This physician would have most likely treated the workmen with remedies and incantations found in his medical papyrus. About a dozen extensive medical papyri have been identified from ancient Egypt, including one set from Deir el-Medina.

These texts were a kind of reference book for the ancient Egyptian medical practitioner, listing individual treatments for a variety of ailments. The longest of these, Papyrus Ebers, contains over 800 treatments covering anything from eye problems to digestive disorders. As an example, one treatment for intestinal worms requires the physician to cook the cores of dates and colocynth, a desert plant, together in sweet beer. He then sieved the warm liquid and gave it to the patient to drink for four days.

A sample of the Papyrus Ebers. (

Public Domain

)Just like today, some of these ancient Egyptian medical treatments required expensive and rare ingredients that limited who could actually afford to be treated, but the most frequent ingredients found in these texts tended to be common household items like honey and grease. One text from Deir el-Medina indicates that the state rationed out common ingredients to a few men in the workforce so that they could be shared among the workers.

A sample of the Papyrus Ebers. (

Public Domain

)Just like today, some of these ancient Egyptian medical treatments required expensive and rare ingredients that limited who could actually afford to be treated, but the most frequent ingredients found in these texts tended to be common household items like honey and grease. One text from Deir el-Medina indicates that the state rationed out common ingredients to a few men in the workforce so that they could be shared among the workers.

Despite paid sick leave, medical rations and a state-supported physician, it is clear that in some cases the workmen were actually working through their illnesses.

Leaving a Mark: Elaborate Tattoos Found on 3,000-Year-Old Egyptian MummyThe Turin Papyrus: The Oldest Topographical and Geological Egyptian MapThe Egyptian Dream BookFor example, in one text, the workman Merysekhmet attempted to go to work after being sick. The text tells us that he descended to the King’s Tomb on two consecutive days, but was unable to work. He then hiked back to the village of Deir el-Medina where he stayed for the next ten days until he was able to work again. Though short, these hikes were steep: the trip from Deir el-Medina to the royal tomb involved an ascent greater than climbing to the top of the Great Pyramid. Merysekhmet’s movements across the Theban valleys were likely at the expense of his own health.

This suggests that sick days and medical care were not magnanimous gestures of the Egyptian state, but were rather calculated health care provisions designed to ensure that men like Merysekhmet were healthy enough to work.

Family was a social safety netIn cases where these provisions from the state were not enough, the residents of Deir el-Medina turned to each other. Personal letters from the site indicate that family members were expected to take care of each other by providing clothing and food, especially when a relative was sick. These documents show us that caretaking was a reciprocal relationship between direct family members, regardless of gender or age. Children were expected to take care of both parents just as parents were expected to take care of all of their children.

Ancient Egyptian workmans village "deir el-medina (

CC BY-SA 3.0

) When family members neglected these responsibilities, there were fiscal and social consequences. In her will, the villager Naunakhte indicates that even though she was a dedicated mother to all of her children, four of them abandoned her in her old age. She admonishes them and disinherits them from her will, punishing them financially, but also shaming them in a public document made in front of the most senior members of the Deir el-Medina community.

Ancient Egyptian workmans village "deir el-medina (

CC BY-SA 3.0

) When family members neglected these responsibilities, there were fiscal and social consequences. In her will, the villager Naunakhte indicates that even though she was a dedicated mother to all of her children, four of them abandoned her in her old age. She admonishes them and disinherits them from her will, punishing them financially, but also shaming them in a public document made in front of the most senior members of the Deir el-Medina community.

This shows us that health care at Deir el-Medina was a system with overlying networks of care provided through the state and the community. While workmen counted on the state for paid sick leave, a physician, and even medical ingredients, they were equally dependent on their loved ones for the care necessary to thrive in ancient Egypt.

Top image: The village of Deir el-Medina in the West Bank of Luxor, Egypt. Anne Austin, Author provided

The article ‘ Paid sick days and physicians at work: ancient Egyptians had state-supported health care ’ by Anne Austin was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license

We might think of state supported health care as an innovation of the 20th century, but it’s a much older tradition than that. In fact, texts from a village dating back to Egypt’s New Kingdom period, about 3,100-3,600 years ago, suggest that in ancient Egypt there was a state-supported health care network designed to ensure that workers making the king’s tomb were productive.

Health care boosted productivity on the royal tombsThe village of Deir el-Medina was built for the workmen who made the royal tombs during the New Kingdom (1550-1070 BCE). During this period, kings were buried in the Valley of the Kings in a series of rock-cut tombs, not the enormous pyramids of the past. The village was purposely built close enough to the royal tomb to ensure that workers could hike there on a weekly basis.

Stone sarcophagus of Merneptah in KV8. (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)These workmen were not what we normally picture when we think about the men who built and decorated ancient Egyptian royal tombs – they were highly skilled craftsmen. The workmen at Deir el-Medina were given a variety of amenities afforded only to those with the craftsmanship and knowledge necessary to work on something as important as the royal tomb.

Stone sarcophagus of Merneptah in KV8. (

CC BY-SA 3.0

)These workmen were not what we normally picture when we think about the men who built and decorated ancient Egyptian royal tombs – they were highly skilled craftsmen. The workmen at Deir el-Medina were given a variety of amenities afforded only to those with the craftsmanship and knowledge necessary to work on something as important as the royal tomb.New study sheds light into ancient Egyptian health care system at Deir el-MedinaPolish Archaeologists Discover Rare Gift from Father of CleopatraThe village was allotted extra support: The Egyptian state paid them monthly wages in the form of grain and provided them with housing and servants to assist with tasks like washing laundry, grinding grain and porting water. Their families lived with them in the village, and their wives and children could also benefit from these provisions from the state.

Out sick? You’ll need a note

Deir el-Medina, the place the workers called home. (

CC BY 3.0

)Among these texts are numerous daily records detailing when and why individual workmen were absent from work. Nearly one-third of these absences occur when a workman was too sick to work. Yet, monthly ration distributions from Deir el-Medina are consistent enough to indicate that these workmen were paid even if they were out sick for several days.

Deir el-Medina, the place the workers called home. (

CC BY 3.0

)Among these texts are numerous daily records detailing when and why individual workmen were absent from work. Nearly one-third of these absences occur when a workman was too sick to work. Yet, monthly ration distributions from Deir el-Medina are consistent enough to indicate that these workmen were paid even if they were out sick for several days.These texts also identify a workman on the crew designated as the swnw, physician. The physician was given an assistant and both were allotted days off to prepare medicine and take care of colleagues. The Egyptian state even gave the physician extra rations as payment for his services to the community of Deir el-Medina.

This physician would have most likely treated the workmen with remedies and incantations found in his medical papyrus. About a dozen extensive medical papyri have been identified from ancient Egypt, including one set from Deir el-Medina.

These texts were a kind of reference book for the ancient Egyptian medical practitioner, listing individual treatments for a variety of ailments. The longest of these, Papyrus Ebers, contains over 800 treatments covering anything from eye problems to digestive disorders. As an example, one treatment for intestinal worms requires the physician to cook the cores of dates and colocynth, a desert plant, together in sweet beer. He then sieved the warm liquid and gave it to the patient to drink for four days.

A sample of the Papyrus Ebers. (

Public Domain

)Just like today, some of these ancient Egyptian medical treatments required expensive and rare ingredients that limited who could actually afford to be treated, but the most frequent ingredients found in these texts tended to be common household items like honey and grease. One text from Deir el-Medina indicates that the state rationed out common ingredients to a few men in the workforce so that they could be shared among the workers.

A sample of the Papyrus Ebers. (

Public Domain

)Just like today, some of these ancient Egyptian medical treatments required expensive and rare ingredients that limited who could actually afford to be treated, but the most frequent ingredients found in these texts tended to be common household items like honey and grease. One text from Deir el-Medina indicates that the state rationed out common ingredients to a few men in the workforce so that they could be shared among the workers.Despite paid sick leave, medical rations and a state-supported physician, it is clear that in some cases the workmen were actually working through their illnesses.

Leaving a Mark: Elaborate Tattoos Found on 3,000-Year-Old Egyptian MummyThe Turin Papyrus: The Oldest Topographical and Geological Egyptian MapThe Egyptian Dream BookFor example, in one text, the workman Merysekhmet attempted to go to work after being sick. The text tells us that he descended to the King’s Tomb on two consecutive days, but was unable to work. He then hiked back to the village of Deir el-Medina where he stayed for the next ten days until he was able to work again. Though short, these hikes were steep: the trip from Deir el-Medina to the royal tomb involved an ascent greater than climbing to the top of the Great Pyramid. Merysekhmet’s movements across the Theban valleys were likely at the expense of his own health.

This suggests that sick days and medical care were not magnanimous gestures of the Egyptian state, but were rather calculated health care provisions designed to ensure that men like Merysekhmet were healthy enough to work.

Family was a social safety netIn cases where these provisions from the state were not enough, the residents of Deir el-Medina turned to each other. Personal letters from the site indicate that family members were expected to take care of each other by providing clothing and food, especially when a relative was sick. These documents show us that caretaking was a reciprocal relationship between direct family members, regardless of gender or age. Children were expected to take care of both parents just as parents were expected to take care of all of their children.

Ancient Egyptian workmans village "deir el-medina (

CC BY-SA 3.0

) When family members neglected these responsibilities, there were fiscal and social consequences. In her will, the villager Naunakhte indicates that even though she was a dedicated mother to all of her children, four of them abandoned her in her old age. She admonishes them and disinherits them from her will, punishing them financially, but also shaming them in a public document made in front of the most senior members of the Deir el-Medina community.

Ancient Egyptian workmans village "deir el-medina (

CC BY-SA 3.0

) When family members neglected these responsibilities, there were fiscal and social consequences. In her will, the villager Naunakhte indicates that even though she was a dedicated mother to all of her children, four of them abandoned her in her old age. She admonishes them and disinherits them from her will, punishing them financially, but also shaming them in a public document made in front of the most senior members of the Deir el-Medina community.This shows us that health care at Deir el-Medina was a system with overlying networks of care provided through the state and the community. While workmen counted on the state for paid sick leave, a physician, and even medical ingredients, they were equally dependent on their loved ones for the care necessary to thrive in ancient Egypt.

Top image: The village of Deir el-Medina in the West Bank of Luxor, Egypt. Anne Austin, Author provided

The article ‘ Paid sick days and physicians at work: ancient Egyptians had state-supported health care ’ by Anne Austin was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license

Published on August 20, 2016 03:00

August 19, 2016

Putting the Horse Before the Chariot: Gorgeous Ancient Roman Mosaics Unearthed in Cyprus

Ancient Origins

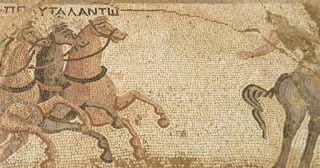

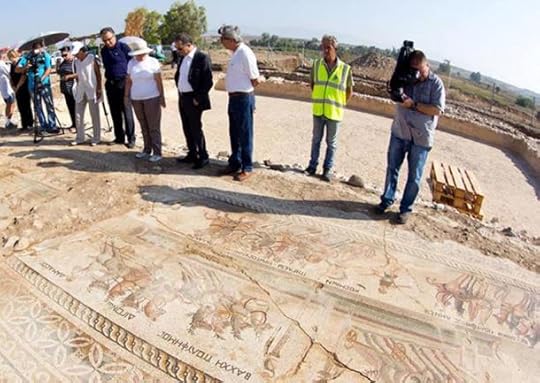

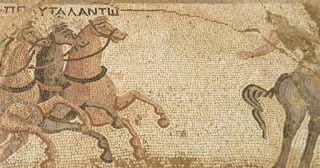

A mosaic floor dating back to the 4th century AD has been unearthed in Cyprus. It illustrates scenes from chariot races in the hippodrome. Previously, another team working on the island found a mosaic showing scenes from the labors of Hercules. That mosaic is two centuries older than the one that was just excavated. Together, these mosaics provide a fascinating glimpse into the interests of ancient Romans that once lived on the Mediterranean island.

The chariot race mosaic was discovered in Akaki village, 19 miles (30.58 km) from the capital city of Cyprus – Nicosia. The mosaic’s existence had been known since 1938 when farmers discovered a small piece of the floor. However, it took 80 years until researchers decided to unearth the whole thing. This magnificent find made the village world famous. The mosaic is the only one of its kind in Cyprus and one of just seven in the world.

According to the Daily Mail, the floor is 11 meters (36 ft.) long and 4 meters (13 ft.) wide. It probably belonged to a nobleman who lived there during the Roman domination on Cyprus. The mosaic is stunningly detailed, decorated with complete race scenes of four charioteers, each being drawn by a team of four horses.

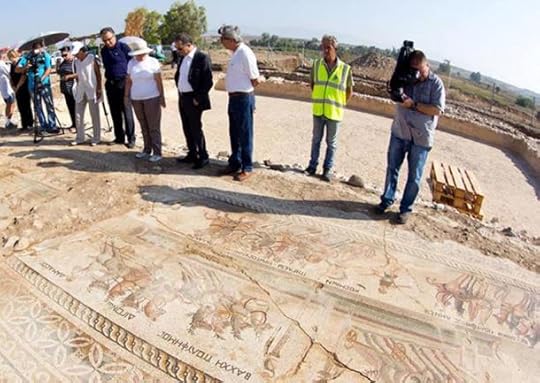

Officials examining part of the mosaic found in Akaki village. (

Cyprus Mail

)The researchers believe that the mosaic shows different factions that competed in ancient Rome. They say that the hippodrome was a very meaningful place in ancient Roman times and it was a center for many events. It was not only a place for sports competitions, but also where the emperor appeared in front of the people and projected his power.

Officials examining part of the mosaic found in Akaki village. (

Cyprus Mail

)The researchers believe that the mosaic shows different factions that competed in ancient Rome. They say that the hippodrome was a very meaningful place in ancient Roman times and it was a center for many events. It was not only a place for sports competitions, but also where the emperor appeared in front of the people and projected his power.

The name “hippodrome” comes from the Greek words hippos ('horse') and dromos ('course'). It was sort of an open-air stadium, used in ancient Greece, Rome, and Byzantine civilizations. The hippodrome was used for many different purposes, but the most spectacular ones were the chariot and horse races.

Discovery Reveals Cyprus was part of Neolithic Revolution3,500-Year-Old Tomb with Remains of 17 Elites and Precious Artifacts Found in Cyprus4,000-year-old cosmetics shop found in Cyprus Ruins of a Roman hippodrome in Tyre, Lebanon. (

Peripitus

/CC BY SA 3.0

)

Inscriptions are seen near the four charioteers depicted in the mosaic which are believed to be their names and the name of one of the horses as well.

Ruins of a Roman hippodrome in Tyre, Lebanon. (

Peripitus

/CC BY SA 3.0

)

Inscriptions are seen near the four charioteers depicted in the mosaic which are believed to be their names and the name of one of the horses as well.

Three cones can also be seen along the circular arena. According to Daily Mail, each one of them is “topped with egg-shaped objects, and three columns seen in the distance hold up dolphin figures with what appears like water flowing from them.”

As Marina Ieronymidou, the director of the Department of Antiquities told journalists during a press conference: “It is an extremely important finding, because of the technique and because of the theme. It is unique in Cyprus since the presence of this mosaic floor in a remote inland area provides important new information on that period in Cyprus and adds to our knowledge of the use of mosaic floors on the island.''

The floor reveals some information about the interests of the upper classes during the 4th century AD. It sheds light on the ancient past of the island's interior and shows that the Roman nobles still cultivated Roman cultural traditions in the 4th century.

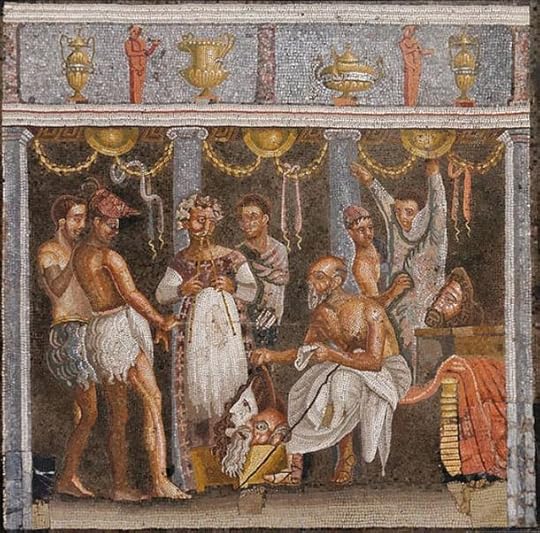

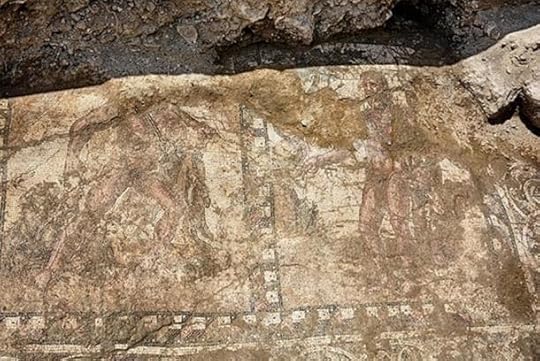

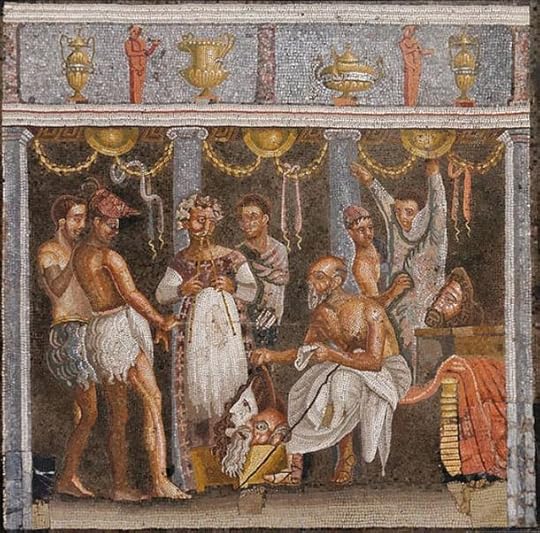

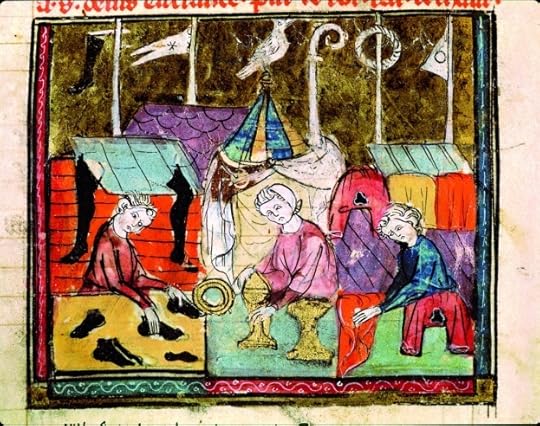

Choregos and actors, Roman mosaic. From the House of the Tragic Poet (VI, 8, 3), Pompeii. (Public Domain)In July 2016, a team of researchers working in the coastal city of Larnaca in Cyprus discovered a 2nd century floor showing the labors of Hercules. It is 20 meters (65 ft.) long and seems to be a part of some ancient baths. It depicts Hercules performing his feats of strength as penance for killing his wife and children in a rage. Larnaca was an ancient city state of Kition, and it was destroyed by earthquakes in the 4th century AD.

Choregos and actors, Roman mosaic. From the House of the Tragic Poet (VI, 8, 3), Pompeii. (Public Domain)In July 2016, a team of researchers working in the coastal city of Larnaca in Cyprus discovered a 2nd century floor showing the labors of Hercules. It is 20 meters (65 ft.) long and seems to be a part of some ancient baths. It depicts Hercules performing his feats of strength as penance for killing his wife and children in a rage. Larnaca was an ancient city state of Kition, and it was destroyed by earthquakes in the 4th century AD.

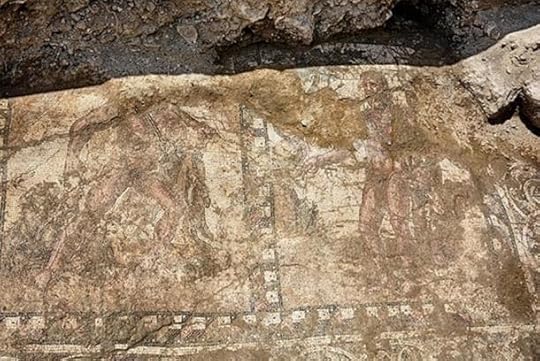

2,400-Year-Old Aristocrat Family Tomb Uncovered in Cyprus Sheds Light on Ancient SoloiThe Ancient Ruins of Salamis, the Once Thriving Port City of CyprusAncient Greek amulet with strange palindrome inscription discovered in Cyprus A 2nd century mosaic showing the labors of Hercules that was discovered in Larnaca. (Cyprus Department of Antiquities)Cyprus was a very attractive place for the nobles during the Roman Empire’s domination of the Mediterranean. Arguably, the most fascinating site on Cyprus is the ancient city of Salamis, which was settled circa 11th century BC. The motif of the chariot also appeared in tombs that were discovered there, showing a continued interest in chariot-related traditions. As April Holloway from Ancient Origins explained in her article from April 6, 2015:

A 2nd century mosaic showing the labors of Hercules that was discovered in Larnaca. (Cyprus Department of Antiquities)Cyprus was a very attractive place for the nobles during the Roman Empire’s domination of the Mediterranean. Arguably, the most fascinating site on Cyprus is the ancient city of Salamis, which was settled circa 11th century BC. The motif of the chariot also appeared in tombs that were discovered there, showing a continued interest in chariot-related traditions. As April Holloway from Ancient Origins explained in her article from April 6, 2015:

Example of mosaic found at the Roman ruins of Salamis. (John Higgins/

Flickr

)These discoveries help show how the Roman nobility’s interests transformed over the ages. While some motifs remained popular over the years, others were introduced or altered to reflect current practices.

Example of mosaic found at the Roman ruins of Salamis. (John Higgins/

Flickr

)These discoveries help show how the Roman nobility’s interests transformed over the ages. While some motifs remained popular over the years, others were introduced or altered to reflect current practices.

Top Image: Detail of the chariot race mosaic. Source: Pavlos Vrionides

By Natalia Klimczak

A mosaic floor dating back to the 4th century AD has been unearthed in Cyprus. It illustrates scenes from chariot races in the hippodrome. Previously, another team working on the island found a mosaic showing scenes from the labors of Hercules. That mosaic is two centuries older than the one that was just excavated. Together, these mosaics provide a fascinating glimpse into the interests of ancient Romans that once lived on the Mediterranean island.

The chariot race mosaic was discovered in Akaki village, 19 miles (30.58 km) from the capital city of Cyprus – Nicosia. The mosaic’s existence had been known since 1938 when farmers discovered a small piece of the floor. However, it took 80 years until researchers decided to unearth the whole thing. This magnificent find made the village world famous. The mosaic is the only one of its kind in Cyprus and one of just seven in the world.

According to the Daily Mail, the floor is 11 meters (36 ft.) long and 4 meters (13 ft.) wide. It probably belonged to a nobleman who lived there during the Roman domination on Cyprus. The mosaic is stunningly detailed, decorated with complete race scenes of four charioteers, each being drawn by a team of four horses.

Officials examining part of the mosaic found in Akaki village. (

Cyprus Mail

)The researchers believe that the mosaic shows different factions that competed in ancient Rome. They say that the hippodrome was a very meaningful place in ancient Roman times and it was a center for many events. It was not only a place for sports competitions, but also where the emperor appeared in front of the people and projected his power.

Officials examining part of the mosaic found in Akaki village. (

Cyprus Mail

)The researchers believe that the mosaic shows different factions that competed in ancient Rome. They say that the hippodrome was a very meaningful place in ancient Roman times and it was a center for many events. It was not only a place for sports competitions, but also where the emperor appeared in front of the people and projected his power.The name “hippodrome” comes from the Greek words hippos ('horse') and dromos ('course'). It was sort of an open-air stadium, used in ancient Greece, Rome, and Byzantine civilizations. The hippodrome was used for many different purposes, but the most spectacular ones were the chariot and horse races.

Discovery Reveals Cyprus was part of Neolithic Revolution3,500-Year-Old Tomb with Remains of 17 Elites and Precious Artifacts Found in Cyprus4,000-year-old cosmetics shop found in Cyprus

Ruins of a Roman hippodrome in Tyre, Lebanon. (

Peripitus

/CC BY SA 3.0

)

Inscriptions are seen near the four charioteers depicted in the mosaic which are believed to be their names and the name of one of the horses as well.

Ruins of a Roman hippodrome in Tyre, Lebanon. (

Peripitus

/CC BY SA 3.0

)

Inscriptions are seen near the four charioteers depicted in the mosaic which are believed to be their names and the name of one of the horses as well.Three cones can also be seen along the circular arena. According to Daily Mail, each one of them is “topped with egg-shaped objects, and three columns seen in the distance hold up dolphin figures with what appears like water flowing from them.”

As Marina Ieronymidou, the director of the Department of Antiquities told journalists during a press conference: “It is an extremely important finding, because of the technique and because of the theme. It is unique in Cyprus since the presence of this mosaic floor in a remote inland area provides important new information on that period in Cyprus and adds to our knowledge of the use of mosaic floors on the island.''

The floor reveals some information about the interests of the upper classes during the 4th century AD. It sheds light on the ancient past of the island's interior and shows that the Roman nobles still cultivated Roman cultural traditions in the 4th century.

Choregos and actors, Roman mosaic. From the House of the Tragic Poet (VI, 8, 3), Pompeii. (Public Domain)In July 2016, a team of researchers working in the coastal city of Larnaca in Cyprus discovered a 2nd century floor showing the labors of Hercules. It is 20 meters (65 ft.) long and seems to be a part of some ancient baths. It depicts Hercules performing his feats of strength as penance for killing his wife and children in a rage. Larnaca was an ancient city state of Kition, and it was destroyed by earthquakes in the 4th century AD.

Choregos and actors, Roman mosaic. From the House of the Tragic Poet (VI, 8, 3), Pompeii. (Public Domain)In July 2016, a team of researchers working in the coastal city of Larnaca in Cyprus discovered a 2nd century floor showing the labors of Hercules. It is 20 meters (65 ft.) long and seems to be a part of some ancient baths. It depicts Hercules performing his feats of strength as penance for killing his wife and children in a rage. Larnaca was an ancient city state of Kition, and it was destroyed by earthquakes in the 4th century AD.2,400-Year-Old Aristocrat Family Tomb Uncovered in Cyprus Sheds Light on Ancient SoloiThe Ancient Ruins of Salamis, the Once Thriving Port City of CyprusAncient Greek amulet with strange palindrome inscription discovered in Cyprus

A 2nd century mosaic showing the labors of Hercules that was discovered in Larnaca. (Cyprus Department of Antiquities)Cyprus was a very attractive place for the nobles during the Roman Empire’s domination of the Mediterranean. Arguably, the most fascinating site on Cyprus is the ancient city of Salamis, which was settled circa 11th century BC. The motif of the chariot also appeared in tombs that were discovered there, showing a continued interest in chariot-related traditions. As April Holloway from Ancient Origins explained in her article from April 6, 2015:

A 2nd century mosaic showing the labors of Hercules that was discovered in Larnaca. (Cyprus Department of Antiquities)Cyprus was a very attractive place for the nobles during the Roman Empire’s domination of the Mediterranean. Arguably, the most fascinating site on Cyprus is the ancient city of Salamis, which was settled circa 11th century BC. The motif of the chariot also appeared in tombs that were discovered there, showing a continued interest in chariot-related traditions. As April Holloway from Ancient Origins explained in her article from April 6, 2015:“Salamis was a large city in ancient times. It served many dominant groups over the course of its history, including Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, and Romans. According to Homeric legend, Salamis was founded by archer Teucer from the Trojan War […] The city contains large, arched tombs, dating back to the 7th and 8th century, BC.

As with any culture, the tombs give a glimpse into the social hierarchy of the ancient residents of the city. Royalty was not buried within the tombs, as they were reserved for nobles. The tombs were constructed from large ashlars (fine cut masonry) and mud brick. When one was buried, the horse and chariot from the procession would be sacrificed in front of the tomb. The sacrifice of a horse in this method was a common ritual for funerals. Tombs also included grave good such as weapons and jewelry.”

Example of mosaic found at the Roman ruins of Salamis. (John Higgins/

Flickr

)These discoveries help show how the Roman nobility’s interests transformed over the ages. While some motifs remained popular over the years, others were introduced or altered to reflect current practices.

Example of mosaic found at the Roman ruins of Salamis. (John Higgins/

Flickr

)These discoveries help show how the Roman nobility’s interests transformed over the ages. While some motifs remained popular over the years, others were introduced or altered to reflect current practices.Top Image: Detail of the chariot race mosaic. Source: Pavlos Vrionides

By Natalia Klimczak

Published on August 19, 2016 03:00

August 18, 2016

A time traveller’s guide to medieval shopping

History Extra

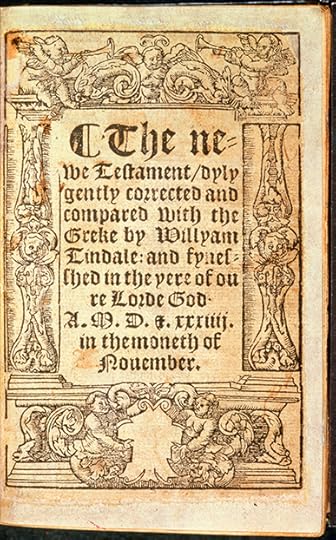

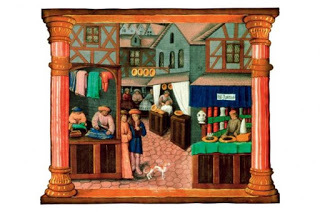

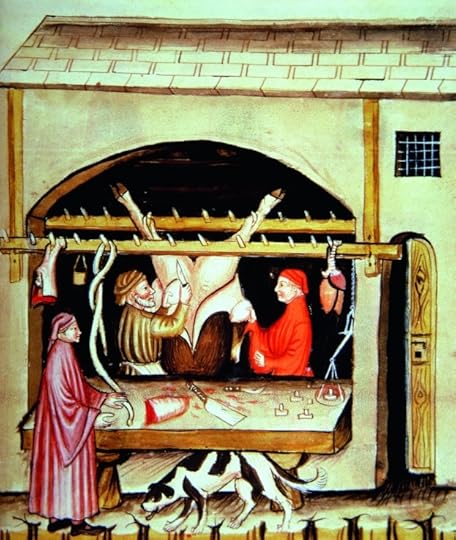

This image shows a 15th-century continental town (taken from the Livre de Gouvernement des Princes by Gilles de Rome). It shows an apothecary shop well-stocked with red and white jars of medicinal substances; a barber using a cut-throat razor; and a tailor and his apprentice working on clothes. Credit Bridgeman Art Library The poet WH Auden once suggested that, in order to understand your own country, you need to have lived in at least two others. But what about your own time? By the same reckoning, you need to have experienced at least two other centuries. This presents us with some difficulties. But through historical research, coming to terms with another century is not impossible.

This image shows a 15th-century continental town (taken from the Livre de Gouvernement des Princes by Gilles de Rome). It shows an apothecary shop well-stocked with red and white jars of medicinal substances; a barber using a cut-throat razor; and a tailor and his apprentice working on clothes. Credit Bridgeman Art Library The poet WH Auden once suggested that, in order to understand your own country, you need to have lived in at least two others. But what about your own time? By the same reckoning, you need to have experienced at least two other centuries. This presents us with some difficulties. But through historical research, coming to terms with another century is not impossible.We can approach the past as if it really is ‘a foreign country’ – somewhere we might visit. And we do not actually need to travel in time to appreciate it – just the idea of visiting the past allows us to see life differently, and more immediately. Come shopping in the late 14th century and see for yourself.

The marketplace“Ribs of beef and many a pie!” you hear someone call over your shoulder. Turning, you see a young lad walking through the crowd bearing a tray laden with wooden bowls of cooked meats from a local shop.

All around him people are moving, gesturing, talking. So many have come in from the surrounding villages that this town of about 3,000 inhabitants is today thronged with twice as many. Here are men in knee-length brown tunics driving their cattle before them. Here are their wives in long kirtles with wimples around their heads and necks. Those men in short tunics and hoods are valets in a knight’s household. Those in long gowns with high collars and beaver-fur hats are wealthy merchants. Across the marketplace more peasants are leading in their flocks of sheep, or packhorses and carts loaded with crates of chickens.

Crowds are noisy. People are talking so much that chatter could almost be the whole purpose of the market – and in many ways it is. This is the one open public area in the town where people can meet and exchange information. When a company performs a mystery play, it is to the marketplace that they will drag the cart containing their stage, set and costumes. When the town crier rings his bell to address the people of the town, it is in the marketplace that the crowd will gather to hear him. The marketplace is the heart of any town: indeed, the very definition of a town is that it has a market.

What can you buy? Let’s start at the fishmongers’ stalls. You may have heard that many sorts of freshwater and sea fish are eaten in medieval England. Indeed, more than 150 species are consumed by the nobility and churchmen, drawn from their own fishponds as well as the rivers and seas.

But in most markets it is the popular varieties which you see glistening in the wet hay-filled crates. Mackerel, herring, lampreys, cod, eels, Aberdeen fish (cured salmon and herring), and stockfish (salt cod) are the most common varieties. Crabs and lobsters are transported live, in barrels. In season you will see fresh salmon – attracting the hefty price of four or five shillings each. A fresh turbot can cost even more, up to seven shillings.

Next we come to an area set aside for corn: sacks of wheat, barley, oats and rye are piled up, ready for sale to the townsmen. Then the space given over to livestock: goats, sheep, pigs and cows. A corner is devoted to garden produce – apples, pears, vegetables, garlic and herbs – yet the emphasis of a medieval diet is on meat, cheese and cereal crops. In a large town you will find spicerers selling such exotic commodities as pepper, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, liquorice, and many different types of sugar.

These are only for the wealthy. When your average skilled workman earns only two shillings (2s) in a week, he can hardly afford to spend four shillings (4s) on a pound of cloves or 20 pence (20d) on a pound of ginger.

The rest of the marketplace performs two functions. Producers come to sell fleeces, sacks of wool, tanned hides, furs, iron, steel and tin for resale further afield. The other function is to sell manufactured commodities to local people: brass and bronze cooking vessels, candlesticks and spurs, pewterware, woollen cloth, silk, linen, canvas, carts, rushes (for hall floors), glass, faggots, coal, nails, horse shoes and planks of wood.

Planks, you ask? Consider the difficulties of transporting a tree trunk to a saw pit, and then getting two men to saw it into planks with only a handsaw between them.

Everyone in medieval society is heavily dependent on each other for such supplies, and the marketplace is where all these interdependencies meet.

A vendor removes the udders from a cow in this contemporary depiction of a 14th-century butcher’s shop. (Bridgeman Art Library)

HagglingEssential items such as ale and bread have their prices fixed by law. Yet for almost everything that’s been manufactured you will have to negotiate. Caxton’s 15th-century dialogue book is based on a 14th-century language guide, and gives the following lesson in how to haggle with a cloth vendor:

“Dame, what hold ye the ell (45 inches) of this

cloth? Or what is worth the cloth whole?

In short, so to speak, how much the ell?”

“Sire, reason; ye shall have it good and cheap.”

“Yea, truly, for cattle. Dame, ye must me win.

Take heed what I shall pay.”

“Four shillings for the ell, if it please you.”

“For so much would I have good scarlet.”

“But I have some which is not of the best

which I would not give for seven shillings.”

“But this is no such cloth, of so much money,

that know ye well!”

“Sire, what is it worth?”

“Dame, it were worth to me well three shillings.”

“That is evil-boden.”

“But say certainly how shall I have it without

a part to leave?”

“I shall give it ye at one word: ye shall pay five

shillings, certainly if ye have them for so many

ells, for I will abate nothing.”