MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 86

August 13, 2016

Researchers Unearth 6th Century Palace from the Legendary Birthplace of King Arthur

Ancient Origins

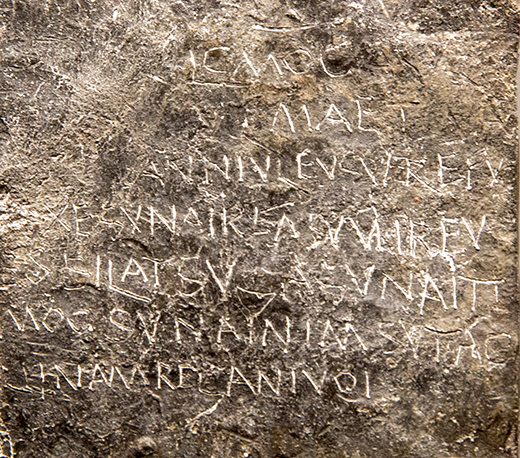

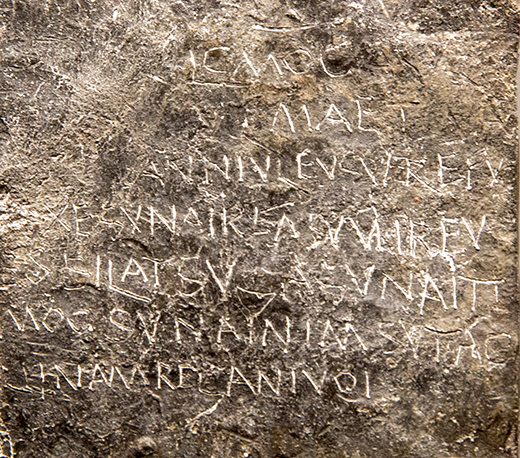

Researchers working in Cornwall have unearthed the remains of walls from a palace they believe dates to the 6th century. These walls may share a connection with the legendary King Arthur, as they are located on the site of Tintagel Castle, a dwelling that folklore associates with his birthplace

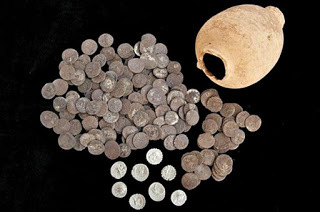

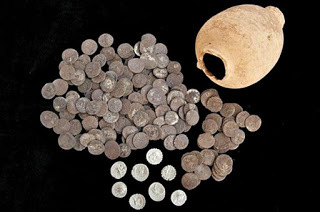

The Telegraph reports that the uncovered structure was likely the home of powerful and wealthy rulers of the ancient British kingdom of Dumnonia. Evidence supporting this idea comes in the form of approximately 150 fragments of pottery and glassware that hail from various locations mostly from the Mediterranean region. Two artifacts the team has uncovered so far are pieces of an amphora and fragments of a Phoenician red-slip bowl or large dish which was thought to have passed around during ancient feasts.

Ryan Smith (trench supervisor) holding a Phoenician red slip water from Western Turkey. (

Emily Whitfield-Wicks

)

Ryan Smith (trench supervisor) holding a Phoenician red slip water from Western Turkey. (

Emily Whitfield-Wicks

)

The excavations are a part of an English Heritage five-year project that is delving into the mysterious story of the famous Cornwall archaeological site from the 5th-7th centuries. The location is best known for the 13th century Tintagel Castle.

The ruins of the upper mainland courtyards of Tintagel Castle, Cornwall. (

Kerry Garratt/CC BY SA 2.0

)Some historical texts state that King Arthur was born at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall. This king is often remembered from tales involving his sword Excalibur, the knights of the round table , and his teacher/mentor (or possible enemy) Merlin the magician .

The ruins of the upper mainland courtyards of Tintagel Castle, Cornwall. (

Kerry Garratt/CC BY SA 2.0

)Some historical texts state that King Arthur was born at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall. This king is often remembered from tales involving his sword Excalibur, the knights of the round table , and his teacher/mentor (or possible enemy) Merlin the magician .

More than a Dozen Mysterious Prehistoric Tunnels in Cornwall, England, Mystify Researchers

Historians Draw Closer to the Tomb of the Legendary King Arthur The Grail Cypher: A radical reassessment of Arthurian history Although many people are enthralled with Arthurian legends, researchers such as Ralph Ellis have argued that :

Illustration from page 16 of ‘The Boy's King Arthur.’ (

Public Domain

)Thus, the legends behind King Arthur have yet to be fully understood as myth or fact (or a combination of the two). Moreover, there have also been doubts raised recently about the general perception of his birthplace as well. For example, Graham Phillips seems to believe that the king existed, but that a lot of the legends surrounding his life are wrong, including his place of birth, which Phillips says was Shropshire - not South West England.

Illustration from page 16 of ‘The Boy's King Arthur.’ (

Public Domain

)Thus, the legends behind King Arthur have yet to be fully understood as myth or fact (or a combination of the two). Moreover, there have also been doubts raised recently about the general perception of his birthplace as well. For example, Graham Phillips seems to believe that the king existed, but that a lot of the legends surrounding his life are wrong, including his place of birth, which Phillips says was Shropshire - not South West England.

Regardless of if it was in fact the site of the legendary king’s birth, Tintagel is seen as one of Europe’s most important archaeological sites.

As the Telegraph says: “The remains of the castle, built in the 1230s and 1240s by Richard, Earl of Cornwall, brother of Henry III, stand on the site of an early Medieval settlement, where experts believe high-status leaders may have lived and traded with far-off shores, importing exotic goods and trading tin.”

Ruins of the Norman castle at Tintagel. (

CC BY SA 3.0

)Win Scutt, one of English Heritage’s properties curators, is hopeful that more finds are on the horizon for the well-known site. He told the Telegraph:

Ruins of the Norman castle at Tintagel. (

CC BY SA 3.0

)Win Scutt, one of English Heritage’s properties curators, is hopeful that more finds are on the horizon for the well-known site. He told the Telegraph:

Excavations at Tintagel Castle (

Emily Whitfield-Wicks

)Top Image: Tintagel Castle archeology dig. Source:

Emily Whitfield-Wicks

Excavations at Tintagel Castle (

Emily Whitfield-Wicks

)Top Image: Tintagel Castle archeology dig. Source:

Emily Whitfield-Wicks

By Alicia McDermott

Researchers working in Cornwall have unearthed the remains of walls from a palace they believe dates to the 6th century. These walls may share a connection with the legendary King Arthur, as they are located on the site of Tintagel Castle, a dwelling that folklore associates with his birthplace

The Telegraph reports that the uncovered structure was likely the home of powerful and wealthy rulers of the ancient British kingdom of Dumnonia. Evidence supporting this idea comes in the form of approximately 150 fragments of pottery and glassware that hail from various locations mostly from the Mediterranean region. Two artifacts the team has uncovered so far are pieces of an amphora and fragments of a Phoenician red-slip bowl or large dish which was thought to have passed around during ancient feasts.

Ryan Smith (trench supervisor) holding a Phoenician red slip water from Western Turkey. (

Emily Whitfield-Wicks

)

Ryan Smith (trench supervisor) holding a Phoenician red slip water from Western Turkey. (

Emily Whitfield-Wicks

)

The excavations are a part of an English Heritage five-year project that is delving into the mysterious story of the famous Cornwall archaeological site from the 5th-7th centuries. The location is best known for the 13th century Tintagel Castle.

The ruins of the upper mainland courtyards of Tintagel Castle, Cornwall. (

Kerry Garratt/CC BY SA 2.0

)Some historical texts state that King Arthur was born at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall. This king is often remembered from tales involving his sword Excalibur, the knights of the round table , and his teacher/mentor (or possible enemy) Merlin the magician .

The ruins of the upper mainland courtyards of Tintagel Castle, Cornwall. (

Kerry Garratt/CC BY SA 2.0

)Some historical texts state that King Arthur was born at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall. This king is often remembered from tales involving his sword Excalibur, the knights of the round table , and his teacher/mentor (or possible enemy) Merlin the magician . More than a Dozen Mysterious Prehistoric Tunnels in Cornwall, England, Mystify Researchers

Historians Draw Closer to the Tomb of the Legendary King Arthur The Grail Cypher: A radical reassessment of Arthurian history Although many people are enthralled with Arthurian legends, researchers such as Ralph Ellis have argued that :

“The story of King Arthur and his gallant knights that this semi-mythical Walter Kayo eventually crafted is complex, frustrating and fraught with contradictions and impossibilities. In the hands of subsequent Arthurian authors it became a compilation of two histories blended together in such a clumsy manner that it betrays confusion in both its broad outline and finer detail. Very few of the names and events recorded in these chronicles exist in the historical record […]”

Illustration from page 16 of ‘The Boy's King Arthur.’ (

Public Domain

)Thus, the legends behind King Arthur have yet to be fully understood as myth or fact (or a combination of the two). Moreover, there have also been doubts raised recently about the general perception of his birthplace as well. For example, Graham Phillips seems to believe that the king existed, but that a lot of the legends surrounding his life are wrong, including his place of birth, which Phillips says was Shropshire - not South West England.

Illustration from page 16 of ‘The Boy's King Arthur.’ (

Public Domain

)Thus, the legends behind King Arthur have yet to be fully understood as myth or fact (or a combination of the two). Moreover, there have also been doubts raised recently about the general perception of his birthplace as well. For example, Graham Phillips seems to believe that the king existed, but that a lot of the legends surrounding his life are wrong, including his place of birth, which Phillips says was Shropshire - not South West England. Regardless of if it was in fact the site of the legendary king’s birth, Tintagel is seen as one of Europe’s most important archaeological sites.

As the Telegraph says: “The remains of the castle, built in the 1230s and 1240s by Richard, Earl of Cornwall, brother of Henry III, stand on the site of an early Medieval settlement, where experts believe high-status leaders may have lived and traded with far-off shores, importing exotic goods and trading tin.”

Ruins of the Norman castle at Tintagel. (

CC BY SA 3.0

)Win Scutt, one of English Heritage’s properties curators, is hopeful that more finds are on the horizon for the well-known site. He told the Telegraph:

Ruins of the Norman castle at Tintagel. (

CC BY SA 3.0

)Win Scutt, one of English Heritage’s properties curators, is hopeful that more finds are on the horizon for the well-known site. He told the Telegraph: “This is the most significant archaeological project at Tintagel since the 1990s. The three-week dig is the first step in a five year research programme to answer some key questions about Tintagel and Cornwall’s past. The discovery of high-status buildings – potentially a royal palace complex – at Tintagel is transforming our understanding of the site. We’re cutting a small window into the site’s history, to guide wider excavations next year. We’ll also be gathering samples for analysis. It’s when these samples are studied in the laboratory that the fun really starts, and we’ll begin to unearth Tintagel’s secrets.”Jacky Nowakowski, archaeologist at the Cambridge Archaeology Unit and head of the current excavations, shares Scutt’s hope and excitement about recent and future findings at the site. She said :

"It is a great opportunity to shed new light on a familiar yet infinitely complex site where there is still much to learn and to contribute to active research of a major site of international significance in Cornwall. Our excavations are underway now, and will run both this summer and next, giving visitors the chance to see and hear at first hand new discoveries being made and share in the excitement of the excavations.”What further mysteries are waiting to be unravelled at the Tintagel archaeological site in Cornwall?

Excavations at Tintagel Castle (

Emily Whitfield-Wicks

)Top Image: Tintagel Castle archeology dig. Source:

Emily Whitfield-Wicks

Excavations at Tintagel Castle (

Emily Whitfield-Wicks

)Top Image: Tintagel Castle archeology dig. Source:

Emily Whitfield-Wicks

By Alicia McDermott

Published on August 13, 2016 03:00

August 12, 2016

Vikings Brutally Slain in 750 AD May Have Been on a Peaceful Mission

Ancient Origins

When people think of Vikings going on voyages, many imagine a bloodthirsty crew bent on evil and domination, and armed to the teeth for the looting and pillaging of helpless villagers. That may have been true of some Viking missions, but perhaps not all.

Researchers analyzing two apparent Viking ship burials from more than 1,000 years ago in the Baltic Sea have published a new article in the journal Antiquity. The authors speculate that this crew, who died violent deaths, was intent on more a more peaceful mission.

The men aboard the two ships were carefully buried on their ships, says an article about the research in USA Today:

These elaborate, gilded sword handle parts found aboard the ships show the weapons may have been more for show than for battle. Photo by Reet MaldreThe remains of the men on the larger ship had stab wounds, decapitation signs and the arm bone of one man and another man’s leg bone were cut by a blade. Their fancy weapons may have been more ceremonial than practical war-making implements. Warriors of the Viking era usually used spears and battle axes instead of swords, co-author Jüri Peet told USA Today. Peet, who headed the excavations, is with Estonia’s Tallinn University.

These elaborate, gilded sword handle parts found aboard the ships show the weapons may have been more for show than for battle. Photo by Reet MaldreThe remains of the men on the larger ship had stab wounds, decapitation signs and the arm bone of one man and another man’s leg bone were cut by a blade. Their fancy weapons may have been more ceremonial than practical war-making implements. Warriors of the Viking era usually used spears and battle axes instead of swords, co-author Jüri Peet told USA Today. Peet, who headed the excavations, is with Estonia’s Tallinn University.

Workers laying electrical cables discovered the first ship, the smaller one, on the shore of Saaremaa Island in the Baltic Sea in 2008. Officials called a halt to work, and Peet began excavations.

This modern Google map show Saaremaa Island off Estonia’s coast.In 2010 the larger of the two ships was found. Researchers assumed the men died a-viking—plundering or conquering. USA Today says the evidence provided by the artifacts didn’t jibe. Whatever they were doing, they apparently were involved in a wild battle in which they were overpowered.

This modern Google map show Saaremaa Island off Estonia’s coast.In 2010 the larger of the two ships was found. Researchers assumed the men died a-viking—plundering or conquering. USA Today says the evidence provided by the artifacts didn’t jibe. Whatever they were doing, they apparently were involved in a wild battle in which they were overpowered.

If they truly were Viking vessels, they are the oldest known Viking ships found in the region, says an article on World-Archaeology.com. They are about 100 years older than the Osenberg boat of Norway.

Prow of the Osenberg Viking ship in a museum in Oslo, Norway (

Wikimedia Commons photo

/Grzegorz Wysocki)Carbon-14 dating of the human and animal remains placed them in life about 1,250 years ago.

Prow of the Osenberg Viking ship in a museum in Oslo, Norway (

Wikimedia Commons photo

/Grzegorz Wysocki)Carbon-14 dating of the human and animal remains placed them in life about 1,250 years ago.

The men were buried in a sitting position within the ships. Animal bones from the site showed butchering. “Perhaps they were part of a funerary feast, or supplies the crew had brought along for themselves,” says World Archaeology. “Interestingly, several decapitated goshawks and a sparrowhawk were also found. These birds of prey would have been used for hunting fresh food for the crew as they travelled along the shoreline.”

Usually horse and dog bones are found in boat burials of prominent Vikings, but there were none of those at this one. “These, men were buried far from home, with only the possessions they carried aboard ship with them during their lifetime,” the article states.

Whoever they were and whoever killed them, their remains, the artifacts and the ships are providing researchers with vital information about the early Viking age.

Top image: Some of the skeletons found on one of the two Viking ships. Photo by Jaanus Valt

By Mark Miller

When people think of Vikings going on voyages, many imagine a bloodthirsty crew bent on evil and domination, and armed to the teeth for the looting and pillaging of helpless villagers. That may have been true of some Viking missions, but perhaps not all.

Researchers analyzing two apparent Viking ship burials from more than 1,000 years ago in the Baltic Sea have published a new article in the journal Antiquity. The authors speculate that this crew, who died violent deaths, was intent on more a more peaceful mission.

The men aboard the two ships were carefully buried on their ships, says an article about the research in USA Today:

Whoever interred the dead aboard two ships in what is now Salme, Estonia, in about 750 AD went about their work with great care and respect. Many of the 41 bodies were carefully positioned, and valuables were scattered among the remains. Researchers found swords bedecked with gold and jewels and hundreds of elaborate pieces from a chess-like strategy game called Hnefatafl, or The King's Table. They also found two decapitated hawks and the skeleton of a large dog, which had been cut in half.They were young, tall men. One stood nearly 6 feet—which was much taller than average for the time. Chemical analysis of their teeth and the design of the rich artifacts they were buried with makes the researchers think the men were from central Sweden, according to archaeologist and co-author T. Douglas Price, an emeritus professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

These elaborate, gilded sword handle parts found aboard the ships show the weapons may have been more for show than for battle. Photo by Reet MaldreThe remains of the men on the larger ship had stab wounds, decapitation signs and the arm bone of one man and another man’s leg bone were cut by a blade. Their fancy weapons may have been more ceremonial than practical war-making implements. Warriors of the Viking era usually used spears and battle axes instead of swords, co-author Jüri Peet told USA Today. Peet, who headed the excavations, is with Estonia’s Tallinn University.

These elaborate, gilded sword handle parts found aboard the ships show the weapons may have been more for show than for battle. Photo by Reet MaldreThe remains of the men on the larger ship had stab wounds, decapitation signs and the arm bone of one man and another man’s leg bone were cut by a blade. Their fancy weapons may have been more ceremonial than practical war-making implements. Warriors of the Viking era usually used spears and battle axes instead of swords, co-author Jüri Peet told USA Today. Peet, who headed the excavations, is with Estonia’s Tallinn University.“Game pieces and animals seem impractical for a military expedition but would’ve provided welcome amusement on a diplomatic trip,” USA Today says. “The men may have been on a voyage to forge an alliance or establish kinship ties, Peets says, when unknown parties set upon them.”But another expert on the Viking era, Jan Bill of the Norway Museum of Cultural History, told USA Today that gaming to pass the time was probably habitual on Viking battle voyages. “Whether this group was on a diplomatic mission, or raiding, or both, I don't think we can decide from the evidence of what was used as grave goods,” Bill is quoted as saying.

Workers laying electrical cables discovered the first ship, the smaller one, on the shore of Saaremaa Island in the Baltic Sea in 2008. Officials called a halt to work, and Peet began excavations.

This modern Google map show Saaremaa Island off Estonia’s coast.In 2010 the larger of the two ships was found. Researchers assumed the men died a-viking—plundering or conquering. USA Today says the evidence provided by the artifacts didn’t jibe. Whatever they were doing, they apparently were involved in a wild battle in which they were overpowered.

This modern Google map show Saaremaa Island off Estonia’s coast.In 2010 the larger of the two ships was found. Researchers assumed the men died a-viking—plundering or conquering. USA Today says the evidence provided by the artifacts didn’t jibe. Whatever they were doing, they apparently were involved in a wild battle in which they were overpowered.If they truly were Viking vessels, they are the oldest known Viking ships found in the region, says an article on World-Archaeology.com. They are about 100 years older than the Osenberg boat of Norway.

Prow of the Osenberg Viking ship in a museum in Oslo, Norway (

Wikimedia Commons photo

/Grzegorz Wysocki)Carbon-14 dating of the human and animal remains placed them in life about 1,250 years ago.

Prow of the Osenberg Viking ship in a museum in Oslo, Norway (

Wikimedia Commons photo

/Grzegorz Wysocki)Carbon-14 dating of the human and animal remains placed them in life about 1,250 years ago.The men were buried in a sitting position within the ships. Animal bones from the site showed butchering. “Perhaps they were part of a funerary feast, or supplies the crew had brought along for themselves,” says World Archaeology. “Interestingly, several decapitated goshawks and a sparrowhawk were also found. These birds of prey would have been used for hunting fresh food for the crew as they travelled along the shoreline.”

Usually horse and dog bones are found in boat burials of prominent Vikings, but there were none of those at this one. “These, men were buried far from home, with only the possessions they carried aboard ship with them during their lifetime,” the article states.

Whoever they were and whoever killed them, their remains, the artifacts and the ships are providing researchers with vital information about the early Viking age.

Top image: Some of the skeletons found on one of the two Viking ships. Photo by Jaanus Valt

By Mark Miller

Published on August 12, 2016 03:00

August 11, 2016

The reluctant ambassador: the life and times of Tudor diplomat Sir Thomas Chaloner

History Extra

Sir Thomas Chaloner aged 28. (Private collection, courtesy of Richard Chaloner, Lord Gisborough. Photograph by Peter Morgan)

Sir Thomas Chaloner aged 28. (Private collection, courtesy of Richard Chaloner, Lord Gisborough. Photograph by Peter Morgan) Here, writing for History Extra, O'Sullivan introduces you to the reluctant ambassador who longed for his home in England… This story is set in one of the most turbulent periods of English history, when the government's religious and political policies seemed to change from year to year, and ambitious courtiers and diplomats needed to watch their balance on fortune's slippery wheel. Those who fell off could easily end their lives on the block, as did so many of Thomas Chaloner's patrons and colleagues. But he himself was a survivor because, as he once wrote to a friend, he knew how to keep his opinions to himself. In 1541 the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, ruler of Spain, the Netherlands and much else, collected a large army to deal once and for all with a pressing problem – the Barbary pirates, who were supported by the Turkish sultan and constituted a permanent hazard for all who sailed in the Mediterranean. Charles did not have the manpower to launch a full-scale attack on Constantinople itself but he reckoned that once his army had landed near the pirates' main base in Algiers, resistance would crumble. Then Algiers would fall and thousands of Christians, enslaved by the pirates, could be rescued. Unfortunately, from the start things went very wrong. Opposition was fiercer than expected, the weather was brutal to troops that had to spend nights in the open, and to cap it all Charles's fleet of war ships and transports, on which his soldiers relied for food and also for an eventual withdrawal, was shattered by a violent storm while at anchor. In less than an hour half the fleet had been sunk, with the loss of 8,000 men. Accompanying Charles on his expedition was a small group of Englishmen, of whom the youngest was the 20-year-old Thomas Chaloner, who was experiencing his first taste of foreign travel. When the storm struck he was on board a galley that soon lost its anchor, along with its neighbours. William Hakluyt, chronicler of Tudor voyages, takes up the story: “Thomas Chaloner escaped most wonderfully with his life. For the galley wherein he was, being either dashed against the rocks or shaken with mighty storms and so cast away, after he had saved himself a long while by swimming, when his strength failed him, his arms & hands being faint and weary, with great difficulty laying hold with his teeth on a cable, which was cast out of the next galley, not without breaking and loss of certain of his teeth, at length [he] recovered himself, and returned home into his country in safety.” Thus it was that Chaloner's career very nearly came to an end before it had properly started. One might remark that it was lucky he could swim – an unusual skill in those days, even for professional sailors. He had other accomplishments too. His father, Roger, a successful London mercer, had seen him through grammar school and Cambridge, and had then found him a place in the household of Thomas Cromwell – a position seen as a stepping stone towards the higher ranks of government service. By the time of his near drowning Chaloner was already fluent in Latin – essential at university where all the lectures were in Latin. At his college, thought to be St John's, the students were even expected to talk to each other in that language. More unusually, Chaloner also had a grasp of French and Italian, implying that Roger had hired private tutors to teach him these languages, which were not on the school or university curriculum. Something else that was to turn out an asset for him was that he had made friends at university with a certain William Cecil, later Lord Burghley. Many years later Cecil would become Elizabeth I's secretary of state, and the most powerful man in England. After the failure to capture Algiers, Charles V's depleted and demoralised army sailed home in the transports that had survived the storm. Chaloner and the other Englishmen accompanied the emperor to Spain. They were no doubt shocked to learn that during their absence Henry VIII's recently married young wife, Catherine Howard, had been accused of adultery, and was now in the Tower, shortly to be executed. Soon after Chaloner finally returned home he was able to make his first real step up the ladder of promotion. He was appointed one of the two clerks to the Privy Council, the body that, under the monarch, effectively ran the country. The council dealt with all kinds of matter, from private requests and punishments to issues of national finance, diplomacy and war. The clerks were well paid but expected to work hard for their money. They kept detailed minutes of council meetings, wrote dozens of letters, and were often dispatched far and wide on council business.

Sir Thomas Chaloner aged 38. (Private collection, courtesy of Richard Chaloner, Lord Gisborough. Photograph by Peter Morgan) Because of his ability to speak Italian and French, Chaloner often found himself sent to meet foreigners – for instance, to deliver funds to bands of mercenaries hired to fight England's wars. As he became more experienced he was trusted with more delicate missions. To take one example, there was the case of Robert Holgate, archbishop of York, who, at the age of 68 had caused some scandal by marrying Barbara Wentworth who was more than 40 years his junior. Then a young man appeared who claimed that the marriage was invalid because he and Barbara had been betrothed when they were both children. Chaloner was sent up to York along with an ecclesiastical lawyer to investigate. After the death of Henry VIII in 1547 the country was run by Edward Seymour, duke of Somerset, as protector for the nine-year-old Edward VI. Somerset had an ambitious policy to unite England and Scotland by betrothing Edward to the young Mary, Queen of Scots, and when the Scots objected to this plan he decided to use force. He led an army across the border towards Edinburgh, defeating an ill-trained and out-of-date Scottish force at the battle of Pinkie Cleugh. Chaloner played a major part in Somerset's campaign by organising and paying the various mercenary bands that accompanied the English. As reward he was knighted by Somerset – another important step up the ladder. By now Chaloner had married a wealthy widow, Joan Leigh, and on the death of his father found himself the head of an extended family that included two younger brothers, two unmarried sisters and various elderly relatives. He had a house in London and lands to look after in different parts of the country, and consequently spent many hours on horseback, either on missions for the council or to oversee his estates in the north of England. Somehow he also found the time to write poetry, and to translate works from Latin – one of these being the well-known satire by Erasmus, In Praise of Folly. This period of his life is fairly well documented because an account book of his income and expenditure has survived. On Edward VI’s early death in 1553 – probably from tuberculosis – he was succeeded as monarch by his Catholic sister Mary. Chaloner composed, but of course did not publish, a poem about Lady Jane Grey in which he berates “cruel and pitiless Mary” for executing her young rival. While many others, such as his friend William Cecil, chose to leave the country during Mary's reign, the cautious Chaloner not only stayed but managed to remain in government service. Mary even sent him to Scotland to meet the regent, Mary of Guise, and complain about Scottish involvement in anti-English rebellion in Northern Ireland. When Elizabeth I succeeded Mary in 1558, Chaloner was sent to the new emperor of the Holy Roman Empire to discuss the possibility that one of his sons, the archduke Ferdinand, might marry the queen. Chaloner came home with a portrait of the young Ferdinand I to present to Elizabeth, and for a short time marriage seemed on the cards. But then it became known that Ferdinand was already secretly married to a German woman, so attention shifted to his brother, the archduke Charles, as a possible suitor.

A portrait of Queen Elizabeth I from around 1575. (Imagno/Getty Images) Cecil sent Chaloner to the Netherlands in June 1559 to be a fully-fledged ambassador to Philip II, who was then holding court at Ghent. When Philip decided to return to Spain there was a discussion about whether or not England needed a permanent ambassador at his court in Madrid. Chaloner suggested a few names to Cecil but was horrified to learn that he himself had been picked. He had known for some time that he would hate Spain, “that country of heat and inquisition”. When he finally landed at Bilbao in February 1562 he found that all his fears were justified. His luggage was taken away to be searched for heretical books, and when he complained to Philip, no apology was forthcoming. After a difficult journey he reached Madrid, only to be advised by the previous ambassador to start requesting his recall home straight away. Chaloner proved to be a cautious and careful ambassador but, judging by his letters home, he was also a worrier. He worried about his lack of funds and the high cost of living in Madrid; about his difficulties in obtaining interviews with Philip; and his failure to penetrate the aura of secrecy that hung about the Spanish court. He worried about not receiving his due wage as ambassador, and whether this might be due to its having been stolen en route. An important part of Chaloner’s job was to obtain and send home the latest news from Spain, and also to deliver the latest news from England, and this was sometimes difficult. For example, Chaloner was caused a good deal of embarrassment when in the summer of 1562 Elizabeth took the decision to send military aid to the Huguenots in France who were engaged in a civil war against the French government. William Cecil told Chaloner to deny that any such decision had been taken, which he did – until he heard from other sources that an English army had actually been sent to fight in France, thus completely contradicting what he had told everybody at court. Above all, Chaloner worried about his own health. He put down his “quartan agues” (bouts of fever every few days) and his inability to sleep at night to Spanish weather and Spanish food. During those sleepless nights he occupied himself by composing reams of Latin verse that remained unpublished until several years after his death. Reading his letters to Cecil and his other friends, one would put him down as a dedicated hypochondriac, except for the fact that when he was finally allowed to quit Spain some four years later he had to take to his bed, and died within a few months. His ‘agues’ were probably due to malaria, but according to Andreas Vesalius, Philip's court physician, he also suffered from kidney stones brought on by drinking Spanish wines that had been adulterated with lime or chalk to make them look whiter. A couple of years after Chaloner first arrived in Madrid, relations between England and Spain, not brilliant in the first place, suddenly darkened. This was because when Elizabeth I joined in the French wars of religion it became possible for English sea captains to obtain ‘letters of marque’ allowing them to attack French shipping, or to confiscate cargoes bound for France. This was a lucrative business, and soon there were dozens of these freebooters at large, many of them not considering it necessary to distinguish too closely between French and other foreign ships. The Spanish authorities saw them as pirates, and Philip retaliated by ordering all English ships trading in Spanish waters to be seized, and their crews imprisoned. In most cases these sailors were treated extremely roughly, and had to subsist on a diet of bread and water. It was Chaloner's duty as ambassador to intercede for these unfortunates. He received information from his contacts up and down Spain as well as numerous messages from the prisoners themselves. He pulled every string he could think of, worrying all the time that he was not doing enough. Always he was up against the rigid Spanish bureaucracy. Officials were never in a hurry to help, especially in cases concerning ‘heretics’. All this did nothing to improve the ambassador's health and peace of mind. Nevertheless, he did succeed in certain cases in achieving the release of sailors who would otherwise have died in prison. A final worry for Chaloner was that he had no heir to carry on his name and look after his estates. His wife, Joan, had died childless many years earlier, and now he was isolated in a foreign land where he was unlikely to meet any eligible women – the ones he did meet being Catholics and therefore for him unmarriageable. However, before he became an ambassador, Chaloner had as a young widower enjoyed a full social life, and it seems that he was able to persuade a lady whom he had known at that time to visit him in Spain with a view to matrimony. Audrey Frodsham, aged about 35 and unmarried, was from a gentry family of Cheshire. We do not know exactly when she and her servants arrived at Bilbao, but we do know from oblique phrases in Chaloner's letters that she must have left in June 1564, just when Chaloner was embroiled in the issue of the imprisoned sailors. Audrey's trip is important because by the time she left she must have been pregnant with Chaloner’s future son, another Thomas. Some historians who have written about Chaloner have assumed that Thomas Chaloner junior must have been Chaloner's stepson, but this now seems unlikely [the baby was likely conceived sometime before June 1564]. In any case, when Chaloner did retire home, more than a year after Audrey's visit, he found her and her baby in his house to welcome him. In September 1565 the couple were married, and a month after that Chaloner died, having made a will leaving everything to his son and his widow. As ambassador Chaloner was unlucky because relations between Spain and England were starting to deteriorate during his time in office. Nevertheless, Sir Thomas performed his task with skill and discretion. One could say he was a man who dedicated his life to duty. Dan O'Sullivan is author of The Reluctant Ambassador: The Life and Times of Sir Thomas Chaloner, a Tudor Diplomat (Amberley Publishing, 2016).

Published on August 11, 2016 03:00

August 10, 2016

The Spanish Armada: England's lucky escape

History Extra

English ships clash with enemy vessels off Gravelines (now northern France) in a theatrical interpretation of the “defeat of the Spanish Armada”. Tudor spin portrayed the events of August 1588 as a glorious English victory but, argues Robert Hutchinson, bad weather and bad tactics had more to do with the Spanish fleet’s failure than Elizabethan derring-do. (National Maritime Museum)

The failure of the Spanish Armada campaign of 1588 changed the course of European history. If the Duke of Parma’s 27,000-strong invasion force had safely crossed the narrow seas from Flanders, the survival of Elizabeth I’s government and Protestant England would have looked doubtful indeed. If those battle-hardened Spanish troops had landed, as planned, near Margate on the Kent coast, it is likely that they would have been in the poorly defended streets of London within a week, and that the queen and her ministers would have been captured or killed. England would have reverted to the Catholic faith and there may have been no British empire. It was bad luck, bad tactics and bad weather that defeated the Spanish Armada – not the derring-do displayed on the high seas by Elizabeth’s intrepid sea dogs. But it was a near-run thing. Because of Elizabeth’s parsimony, driven by an embarrassingly empty exchequer, the English ships were starved of gunpowder and ammunition and so failed to land a killer blow on the ‘Great and Most Fortunate Navy’ during nine days of skirmishing up the English Channel in July and August 1588. Only six Spanish ships out of the 129 that sailed against England were destroyed as a direct result of naval combat. However, a minimum of 50 Armada ships (probably as many as 64) were lost through accident or during the Atlantic storms that scattered the fleet en route to England and as it limped, badly battered, back to northern Spain. More than 13,500 sailors and soldiers did not come home – the vast majority victims not of English cannon fire, but of lack of food and water, virulent disease and incompetent organisation. Thirty years before, when Philip II of Spain had been such an unenthusiastic husband to Mary I, he had observed: “The kingdom of England is and must always remain strong at sea, since upon this the safety of the realm depends.” Elizabeth knew this full well and gambled that her navy, reinforced by hired armed merchantmen and volunteer ships, could destroy the invasion force at sea. Her warships, she maintained, were the walls of her realm, and they became the first and arguably her last line of defence. Decades of neglect had rendered most of England’s land defences almost useless against an experienced and determined enemy. In March 1587, the counties along the English Channel had just six cannon each. A breach in the coastal fortifications at Bletchington Hill, Sussex, caused 43 years before in a French raid, was still unrepaired. England had no standing army of fully armed and trained soldiers, other than small garrisons in Berwick on the Scottish borders, and in Dover Castle on the Channel coast. Moreover, Elizabeth’s nation was divided by religious dissent – almost half were still Catholic and fears of them rebelling in support of the Spanish haunted her government. Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, was appointed to command Elizabeth’s armies “in the south parts” to fight not only the invaders but any “rebels and traitors and other offenders and their adherents attempting anything against us, our crown and dignity…” and to “repress and subdue, slay or kill and put to death by all ways and means” any such insurgents “for the conservation of our person and peace”. Some among Elizabeth’s subjects placed profit ahead of patriotism. In 1587, 12 English merchants – mostly from Bristol – were discovered supplying the Armada “to the hurt of her majesty and undoing of the realm, if not redressed”. Nine cargoes of contraband, valued between £300 and £2,000, contained not just provisions but also ammunition, gunpowder, muskets and ordnance. What happened to these traders (were they Catholics?) is unknown, but in those edgy times, it’s unlikely they enjoyed the queen’s mercy. Elsewhere, Sir John Gilbert, half-brother to Sir Walter Ralegh, refused permission for his ships to join Sir Francis Drake’s western squadron and allowed them to sail on their planned voyage in March 1588 in defiance of naval orders. If that wasn’t bad enough, Elizabeth’s military advisers – unaware that Parma planned to land on the Kent coast – decided on Essex as the most likely spot where the Spanish would storm ashore.

A contemporary painting of English ships and the Spanish Armada, which, so one Tudor verse had it, bore sailors “that were full of the pox”. (Bridgeman)

A contemporary painting of English ships and the Spanish Armada, which, so one Tudor verse had it, bore sailors “that were full of the pox”. (Bridgeman)Breaking barriers The Thames estuary had a wide channel leading straight to the heart of the capital, bordered by mud flats that posed a major obstacle to a vessel of any draught. Therefore, defensive plans included the installation of an iron chain across the river’s fairway at Gravesend in Kent, designed by the Italian engineer Fedrigo Giambelli. This boom, supported by 120 ship’s masts (costing £6 each) driven into the riverbed and attached to anchored lighters, was intended to stop enemy vessels penetrating upriver to London. Yet it would do no such thing – for it was broken by the first flood tide. A detailed survey of potential invasion beaches along the English Channel produced an alarming catalogue of vulnerability. In Dorset alone, 11 bays were listed, with comments such as: “Chideock and Charmouth are two beaches to land boats but it must be very fair weather and the wind northerly.” Swanage Bay could “hold 100 ships and [the anchorage is able] to land men with 200 boats and to retire again without danger of low water at any time.” Lacking time, money and resources, Elizabeth’s government could only defend the most dangerous beaches by ramming wooden stakes into the sand and shingle as boat obstacles, or by digging deep trenches above the high water mark. Mud ramparts were thrown up to protect the few cannon available, or troops armed with arquebuses (an early type of musket) or bows and arrows. Fortifications on the strategically vital Isle of Wight were to be at least four feet (1.22m) high and eight feet (2.44m) thick, with sharpened poles driven into their face and a wide ditch dug in front. But its governor, Sir George Carey, had just four guns and gunpowder enough for only one day’s use. Portsmouth’s freshly built ramparts protecting its land approaches had been severely criticised by Ralegh and were demolished, much to Elizabeth’s chagrin. New earth walls were built in just four months, bolstered by five stone arrow-head-shaped bastions behind a flooded ditch. Yet, more than half Portsmouth’s garrison were rated “by age and impotency by no way serviceable”, and the Earl of Sussex escaped unhurt when an old iron gun (supposedly one of his best cannon), blew into smithereens. In November 1587, Sussex complained that the town’s seaward tower was “so old and rotten” that he dared not fire one gun to mark the anniversary of the queen’s accession. The network of warning beacons located throughout southern England since at least the early 14th century was overhauled. The iron fire baskets mounted atop a tall wooden structure on earth mounds were set around 15 miles (24km) apart. Kent and Devon had 43 beacon sites, and there were 24 each in Sussex and Hampshire. These were normally manned during the kinder weather of March to October by two “wise, vigilant and discreet” men in 12-hour shifts. Surprise inspections ensured their diligence, and they were prohibited from having dogs with them, for fear of distraction. It was a tedious and uncomfortable patriotic duty. A new shelter was built near one Kent beacon when a old wooden hut fell down. This was intended to protect the sentinels only from bad weather and had no “seats or place of ease lest they should fall asleep. [They] should stand upright in… a hole [looking] towards the beacons.” Not everyone spent their time scanning the horizon for enemy ships: two watchers at Stanway beacon in Essex preferred catching partridges in a cornfield and were hauled up in court.

An English chart shows the Spanish fleet off the coast of Cornwall. Much of the local militia slunk away when the Armada cleared the county. (National Maritime Museum)

An English chart shows the Spanish fleet off the coast of Cornwall. Much of the local militia slunk away when the Armada cleared the county. (National Maritime Museum)Malicious firing In July 1586, five men were accused of plotting to maliciously fire the Hampshire beacons “upon a [false] report of the appearance of the Spanish fleet” and in the ensuing tumult, to steal food “to redress the current dearth of corn”; engage in a little light burglary of gentlemen’s houses and liberate imprisoned recusants at Winchester. Most were gaoled but some were sent to London for further interrogation, for fear of a wider conspiracy. Elizabeth’s militia makes the enthusiastic Local Defence Volunteers of ‘Dad’s Army’ during the Nazi invasion scare of 1940 look like a finely honed war machine. A census in 1588 revealed only 100 experienced “martial men” were available for military service and, as some had fought in Henry VIII’s French and Scottish wars of 40 years before, these old sweats were considered hors d’combat. Infantry and cavalry were drawn from the trained bands and county militia. A thousand unpaid veterans from the English army in the Netherlands were recalled but they soon deserted to hide in the tenements of Kent’s Cinque Ports. Militia officers were noblemen and gentry whose motivation was not only defence of their country, but protection of their own property too. Many living near the coast believed it more prudent to move their households inland than stay and fight on the beaches but were ordered to return “on pain of her majesty’s indignation, besides forfeiture of [their] lands and goods…” The main army was divided into two groups. The first, under Leicester, with 27,000 infantry and 2,418 cavalry, would engage the enemy once he had landed in force. The second and larger formation, commanded by the queen’s cousin Lord Hunsdon, totalled 28,900 infantry and 4,400 cavalry. They were recruited solely to defend the sacred person of Elizabeth herself, who probably planned to remain in London, with Windsor Castle as a handy bolt hole if the capital fell. An anonymous correspondent suggested to Elizabeth’s ministers that the best means to resist invasion was “our natural weapon” – the bow and arrow. It had defeated the French at Agincourt in 1415; why not the Spanish in 1588? One can imagine an old buffer, bristling at this threat to hearth and home, insisting that the bow and crossbow were “terrible weapons” which Parma’s mercenaries had not faced before. After further reflection, he concluded that “the most powerful weapon of all against this enemy was the fear of God”. In the event, despite strenuous efforts to buy weapons in Germany, and arquebuses from Holland at 23s 4d (£1.17p) each, many militiamen were armed only with bows and arrows. A large proportion was unarmed and untrained. To avoid the dangers of fifth-columnist recusants in the militia ranks, every man had to swear an oath of loyalty to Elizabeth in front of their muster-masters. Captain Nicholas Dawtrey, sent to train the Hampshire militia, warned that if 3,000 infantry crossed the Solent to defend the Isle of Wight, the Marquis of Winchester would be left “utterly without force of footmen other than a few billmen (with pole arms) to guard and answer all dangerous places”. However, local people complained about being posted away from home, they and their servants being compelled “to go either to Portsmouth or Wight upon every sudden alarm, whereby their houses, wives and children shall be left without guard and left open by their universal absence to all manner of spoil”. Hampshire eventually raised 9,088 men but Dawtrey pointed out that “many… [were] very poorly furnished; some lack a head-piece [helmet], some a sword, some one thing or other that is evil, unfit or unseemly about him”. Discipline was also problematic: the commander of the 3,159-strong Dorset militia (1,800 totally untrained) firmly believed they would “sooner kill one another than annoy the enemy”. When the Armada eventually cleared Cornwall, some of the Cornish militia, ordered to reinforce neighbouring counties, thought they had done more than enough to serve queen and country. Their minds were on the harvest and these reluctant soldiers decided to slink away from their commanders and their colours. The Spanish were now someone else’s problem.

Map Illustration by Martin Sanders.

Map Illustration by Martin Sanders.Armada propagandaWhy it paid to vilify the perfidious Spanish The Tudor propaganda machine became strident as the Spanish fleet appeared, delivering terrifying warnings of genocide to stiffen a fearful population’s resistance. Spanish spies reported that Elizabeth’s ministers, “being in great alarm, made the people believe that the Spaniards [are] bringing a shipload of halters in the Armada to hang all Englishmen and another shipload of scourges to whip women”. As the skirmishes continued in the Channel, foreigners were placed under curfew and had their shops closed up. An Italian, harassed in the streets, maintained it was easier “to find flocks of white crows than one Englishman who loves a foreigner”. A pamphlet entitled A Skeltonical Salutation reassured its readers that fish that consumed the flesh of drowned Spaniards would not be infected by their venereal diseases. The doggerel verse asked whether: “this year it were not best to forebearOn such fish to feedWhich our coast doth breedBecause they are fedWith carcase deadHere and there in the rocksThat were full of the pox… Our Cods and CongerHave filled their hungerWith the heads and feetOf the Spanish fleetWhich to them were as sweetAs a goose to a fox…” Thomas Deloney’s A Joyful New Ballad described Spanish perfidy: “Our wealth and riches, which we enjoyed long;They do appoint their prey and spoil by cruelty and wrongTo set our houses afire on our headsAnd cursedly to cut our throatsAs we lie in our bedsOur children’s brains to dash against the ground” Another tract was said to have been found “in the chamber of Richard Leigh, a seminary priest lately executed for high treason”. In reality, his identity was stolen for propaganda purposes. The ‘tract’ claimed that English naval supremacy and the omnipotence of England’s Protestant God were undeniable. “The Spaniards did never take or sink any English ship or boat or break any mast or took any one man prisoner.” As a result, Spanish prisoners believed that “in all these fights, Christ showed himself a Lutheran”. Armada commander Medina Sidonia attracted special vilification. He spent much of his time “lodged in the bottom of his ship for his safety”. What if the Armada had got through? England’s poorly armed militia and uncompleted defences could have been overwhelmed by Spanish invaders, after landing in Kent with the heavy siege artillery carried by the Armada. Based on the progress of his 22,000 troops – when they covered 65 miles in just six days after invading Normandy in 1592 – the Duke of Parma could have been in London within a week of coming ashore. As the Spanish anchored off Calais, 4,000 militia based in Dover deserted, possibly because they were unpaid, but more probably through abject fear. The port’s defences were hastily stiffened by importing 800 Dutch musketeers, who promptly mutinied. The loyalty of the inhabitants of Kent was uncertain. Informers reported that some rejoiced “when any report was [made] of [the Spaniards’] good success and sorrowed for the contrary” while others declared the Spanish “were better than the people of this land”. As is the case in any invasion planning, the Spanish identified potential collaborators, and enemy leaders to be captured. (Elizabeth was to be detained unharmed and sent to Rome). Those “heretics and schismatics” who faced a sticky end if Spain was victorious included the Earl of Leicester, his brother the Earl of Warwick and brother-in-law the Earl of Huntingdon Lord Burghley, “Secretary Walsingham”, Sir Christopher Hatton, and Lord Hunsdon. These were “the principal devils that rule the court and are the leaders of the [Privy] Council”. The list of “Catholics and friends of his majesty in England” was headed by “the Earl of Surrey, son and heir of the Duke of Norfolk, (actually the Earl of Arundel) now a prisoner in the Tower” and “Lord Vaux of Harrowden, a good Catholic, a prisoner in the Fleet (prison)”. The four potential collaborators in Norfolk included Sir Henry Bedingfield, “formerly the guardian of Queen Elizabeth the pretended queen of England, during the whole time that his majesty was in England”. The document reported that “the greater part of Lancashire is Catholic, the common people particularly, with the exception of the Earl of Derby and the town of Liverpool”. Westmorland and Northumberland remained “really faithful to his majesty”. Amphibious landings, however, are the most risky of all military operations, with everything dependent on weather and tides. And the English fleet would have to be destroyed first. Robert Hutchinson is a historian specialising in the Tudor period. He has previously written biographies of Henry VIII and Francis Walsingham.

Published on August 10, 2016 03:00

August 9, 2016

Welcome to Britannia: Roman Britain in AD 130

History Extra

Hadrian’s Wall dissects the countryside of northern England. By AD 130, the wall’s turf sections were being rebuilt in stone and many adaptations being carried out, a sure sign that trouble was afoot. © Corbis

Hadrian’s Wall dissects the countryside of northern England. By AD 130, the wall’s turf sections were being rebuilt in stone and many adaptations being carried out, a sure sign that trouble was afoot. © Corbis

Britannia lay at the north-westernmost boundaries of an empire so vast that it encompassed “the ocean where the sun god rises to the place where he sinks”. Although an imperial province for more than 80 years, ever since the emperor Claudius, accompanied by elephants, claimed it for Rome, in AD 130 Britannia and her inhabitants remained a byword for a remote land and distant people.

For anyone making the perilous journey across to Britannia’s shores, expectations, as far as we can tell, were low. The natives were considered to be uncultured and generally unpromising, though their plain clothes were of most excellent quality wool and their hunting hounds were deemed to be effective, if unprepossessing in looks. The climate, too, left much to be desired. Here was a place where the rain fell, the sun was seldom seen, and a thick mist was said to rise from the marshes “so that the atmosphere in the country is always gloomy”.

Although the crossing from Gesoriacum (Boulogne) to Rutupiae (Richborough in Kent) was comparatively short (somewhere between six and eight hours), the symbolic distance was immense. For to set foot on a ship bound for Britannia was to venture into Oceanus, that immeasurable expanse of sea, full of monsters and perilous tides which led to a land of unfathomable people.

Although the tentacles of Roman administration via the army had, by AD 130, reached into the furthest corners of the province and the island had been scrupulously measured and recorded, in terms at least of potential revenue, Britannia represented the untamed and unknown.

Tattooed bodiesCensuses may have been carried out for tax purposes, records made of landholdings, distances measured between places, roads built to Roman standards and all rivers and crossing points marked down, but this didn’t mean that the Romans felt any more sympathetic towards the island’s inhabitants. The Britons were regarded as somewhat uncouth, their bodies tattooed with patterns and pictures of all kinds of animals.

Serving officers on Hadrian’s Wall, who referred to Britons disparagingly as Brittunculi or ‘Britlings’, clearly had not progressed very much in their outlook since the days of Cicero who, when writing about his brother on campaign in Britain during Julius Caesar’s expedition there in 54 BC, joked that none of the British were expected to be accomplished in literature or music. The stereotype persisted into the fourth century, when poets were still portraying Britannia with cheeks tattooed, “clothed in the skin of some Caledonian beast”.

By AD 130, many provincials from elsewhere in the empire had made it to the top of Roman society (two successive emperors, Trajan and Hadrian, hailed from Spanish families, the Ulpii and the Aelii) and the Gauls were making vast fortunes in trade, and clawing their way into the senate. There is no record of any Britons doing the same at this period, though many were serving as auxiliary soldiers in far-flung places, such as the cohort of Britons then in Dacia (modern Romania).

British exports tended to be rather unglamorous – tin, lead, hides and slaves. If asked what British products they had bought recently, shoppers on the streets of Rome may have been pushed for an answer. Blankets or rush baskets, perhaps? That said, anyone keen on hunting may have known of – or even possessed – one of their famously ugly but skilful hounds, and the gourmands among them tasted oysters shipped in from Kent.

Having arrived in Britannia, visitors may have had to adjust their literary preconceptions, for by AD 130 the main towns and cities of Britain conformed more or less to a Roman model with some idiosyncratic flourishes. Although houses in both the town and country were generally modest in size – the age of great villa building in Britain had yet to come – the province boasted some magnificent civic architecture.

The gateway to Britannia was the port of Rutupiae on the Kent coast, where passengers alighting on the British shore were greeted by a monumental arch, in gleaming Italian marble, one of the largest in the empire.

The legionary baths at Isca Augusta (Caerleon) also rivalled those anywhere else, while the brand new basilica in the forum at Londinium was the largest north of the Alps. These buildings were all state-sponsored – the British aristocracy did not indulge in the sort of competitive public munificence displayed elsewhere.

In Britannia, London led the way in terms of wealth and fashion, and even modest shops and workshops in the city were being enhanced by reception rooms with painted walls and cement floors. Although the precise civic status of the city in AD 130 is unknown, London was the province’s undoubted epicentre, the place where all major roads passed through or originated. It was the seat of the provincial governor and the imperial procurator whose job it was to oversee the collection of revenues on behalf of the Fiscus (the emperor’s personal treasury).

Trouble aheadIn AD 130, Britannia was an imperial province, which meant that its new governor, Sextus Julius Severus, ruled it on the emperor’s behalf, taking his orders and instructions straight from Hadrian and corresponding directly with him while abroad. Severus, who came from Dalmatia but completed his education in Rome, was said to be one of Hadrian’s best generals and had also proved himself an able administrator. The fact that he had been sent to Britannia at this point may indicate that there was serious trouble there and that Hadrian planned for him either to fight a war or carry out a major reorganisation of the province.

A large number of soldiers were garrisoned in Britannia, and its governorship was one of the two most senior posts available. While no one visited Britannia for the culture, doing a stint in a tough place like this could do no harm to a military or political career.

Hadrian was determined to raise standards of morality. © Alamy

Many who came to Britannia as governors, procurators and commanding officers were able and affluent men who went on to enjoy remarkable careers. L Minicius Natalis, a slick and wealthy Spaniard, arrived here at about this time. Fresh from winning a four-horse chariot race at the Olympic Games in AD 129, he took up the command of the Legio VI Victrix based in Eboracum (York). Senior cavalry officer M Maenius Agrippa from Camerinum (in the Italian Marches), who was personally known to Julius Severus and Hadrian, was shortly to assume command of the classis Britannia, the British fleet. This was one of the most important of all provincial fleets, with bases at Gesoriacum (Boulogne) and Dubris (Dover), in addition to several (presumed) outposts around the British coast. Agrippa would excel at his new job, later being made procurator of the province.

These newcomers to Britannia would have expected to communicate in Latin but would have needed to get used to the peculiarities of the British accent. While upper-class Brits spoke very correct, textbook Latin “better than the Gauls”, some of their vowel sounds were rather affected.

British Latin also developed its own insular peculiarities – such as the use of the word hospitium to mean house or home, which ultimately derived from the word for an inn or lodging. Their native tongue was Brittonic, a Celtic language, similar to those spoken in Gaul. After the Romans arrived, the British adopted many Latin words into their vocabulary to describe aspects of daily life for which there was no existing equivalent.

Strolling around the streets, the newcomer to AD 130 Britannia would have heard many other languages, such as Gaulish, Greek and Palmyrene – spoken by the thousands of foreign soldiers, slaves and traders now based here. Observant travellers would have noticed everywhere small signs that they were somewhere far from home. They may have remarked upon how keen the British were on cleaning their nails, and how attached they were to personal grooming sets, which included scoops for cleaning out their ears.

Finest fish sauceExcellent supply networks meant that people could obtain imported food and drink in all parts of the province, such as Spanish olive oil, Gallic wine and Lucius Tettius Africanus’s “finest fish sauce from Antibes”. Men such as Tiberinius Celerianus, a merchant shipper from Gaul, clearly felt so at home here that he declared himself boldly to be Londoniensium primus – ‘first of the Londoners’ – on an altar he dedicated at Southwark.

Outside London, one of the most cosmopolitan places in the country was Hadrian’s Wall, base of thousands of Roman troops. Tensions here ran deep. Hostility simmered within and without the borders the Romans had imposed, among the unconquered tribes of Caledonia, among disaffected and uprooted peoples who had moved further north – and among those within the frontier zone itself.

The wall had hacked a brutal and in many ways unimaginative course across the country – one that severed Britons’ ancestral homes in two. Those living north of the frontier would have suddenly found their access to lands or family or markets to the south of it severely restricted.

This coin shows Hadrian inspecting his troops in Britain. © British Museum

Not only were the soldiers and their military installations all too visible in the landscape, but the taxes required to pay for the troops’ upkeep were now being extracted from people whose land had been confiscated to accommodate the garrisons.

If crack soldier and trouble-shooter Julius Severus had to be sent out to Britannia in response to recent serious unrest, then it almost certainly took place up here. The rebuilding of the turf section in stone and construction of new forts on and around the frontier at this period suggests that the situation was tense and unpredictable.

Roman soldiers could be heavy-handed, and many Britons would have felt the force of a centurion’s hobnailed boot. A letter of complaint survives from Vindolanda from a man who was outraged that he, an innocent man from overseas, had been flogged by centurions savagely enough to draw blood (the inference being that if he were a native Briton, that would be a different matter).

In Cumbria, at the wall’s western end, people continued to live in traditional roundhouse enclosures into the fourth century. Some people in the wall’s eastern sector, however, seemed to have succumbed to the blandishments of Roman life, or at least just decided to make the best of it.

By AD 130, villas and settlements similar to those of small towns in the south had begun to appear in the wall’s environs. Some provincials seem to have adopted an idiosyncratic, ‘pick and mix’ attitude to Roman culture. Down at Faverdale in County Durham, some 25 miles south of the wall, one family group continued to live in a roundhouse but had adapted Roman methods of stock-rearing, producing bigger specimens of cattle, sheep and pigs. They had acquired an impressive number of imported Samian ware drinking vessels, while continuing to use handmade pottery of an ancient, Iron Age form. They maintained ancient rituals, such as the careful burial of broken quernstones, but had acquired new ones, including a miniature bathhouse, startlingly painted in red, white, green, yellow, orange, black and pink.

Although containing two heated rooms and a waterproof (opus signinum) floor, it may have struck a visitor used to traditional baths as a little odd, as there was no sort of pool or basin here. Instead, the occupants seemed to have enjoyed intimate shellfish sauna parties – the six people who could comfortably fit into this space snacked on cockles, mussels and oysters as they soaked up the heat. Welcome to Britannia, cAD 130.

The patrons of a tavern enjoy a drink in this second-century AD relief. © Getty

In context: The Roman empire in AD 130In AD 130, Publius Aelius Hadrianus, a complex and energetic man, had been emperor for 14 years. Like his role model, the emperor Augustus, Hadrian adopted a policy of consolidation, defining the boundaries of empire, of which Hadrian’s Wall in Britannia was its most dramatic expression. The wall was begun at his instigation, during a visit to the province in AD 122, following a serious war in the north. In AD 130, Hadrian was also attempting to raise standards of morality and discipline in public life, and was keenly aware of the power of architecture in projecting a political message.

By AD 130, Hadrian’s magnificent 900-room palace at Tivoli was all but completed, as was the newly rebuilt Pantheon in Rome, its massive concrete dome an astonishing feat of engineering. While Rome was still the centre of imperial power, Hadrian was careful not to neglect the provinces and he supported building projects wherever he visited.

Hadrian travelled a great deal. He was particularly attached to Greece, where he spent much of AD 129. That winter he stayed in Antioch, before visiting Palmyra (Syria), Arabia and Judaea the following spring, and arriving in Egypt in summer AD 130 with his wife Vibia Sabina. Here, he was also accompanied by his male lover Antinous, who drowned in the river Nile in October, causing the emperor intense grief.

Ruled Britannia Nine nerve centres of Roman Britain in AD 130

1) Rutupiae (Richborough, Kent)

The port from where Claudius launched his invasion in AD 43, and still the province’s key point of entry. Glistening in Italian marble and adorned with bronzes and sculpture, a gigantic monumental arch represented the accessus Britanniae, the symbolic gateway to Britannia. It aligned with Watling Street, so connected with the network of roads penetrating the whole province.

2) Dubris (Dover)

British base of the classis Britannia (British fleet). Ships were guided into the harbour at the narrow mouth of the river Dour by two lighthouses, one on each of the headlands of the chalk cliffs. Their fire beacons were visible far out to sea – even, on a clear day, as far as Gaul.

This lighthouse guided ships into the harbour at Dover. © Getty

3) Londinium (London)

Britannia’s most important city attracted international trade and a cosmopolitan population. On the boundary of several ancient kingdoms, the city held a pivotal position at the head of a tidal river and at the intersection of key routes into the heart of the province. The provincial governor and procurator were based here.

4) Isca Augusta (Caerleon)

Headquarters of the 2nd Augusta Legion. The fortress occupied a 50-acre site on the right bank of the Usk, at the river’s lowest bridging point before it enters the Severn estuary. It boasted a superb baths complex, 41 metre open-air pool and 6,000-seater amphitheatre. Most legionaries, though, were now stationed further north, deployed on the wall.

The remains of the 6,000-seat amphitheatre at Caerleon. © Alamy

5) Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester)

First settled by an exiled Gallic chief, Calleva was the administrative centre of the Atrebates and the first major town west of London. Standing in an open landscape of pasture, hay meadows and heathland, it lay at the junction of main roads leading to other significant towns in all directions.

6) Viroconium Cornoviorum (Wroxeter, Shropshire)

Capital of the cattle-rearing Cornovii, this town’s brand new forum and basilica were possibly instigated by Hadrian’s visit to Britain in AD 122 and completed and dedicated in AD 130. At this time, plans for baths with a leisure hall were yet to get off the ground.

7) Aquae Sulis (Bath)

This was Britannia’s premiere tourist attraction. The thermal waters were hugely popular, attracting many soldiers on leave and visitors from far and wide. The steaming spring sat in a precinct with classical temple and adjoining baths dedicated to Sulis Minerva – Sulis being a Celtic deity joined with the Roman goddess Minerva.

Tourists flocked to Bath’s famed waters in the second century AD. © Rex Features

8) Banna (Birdoswald, Cumbria)

In AD 130, big changes were afoot at this fort, which sat astride Hadrian’s Wall high on top of an escarpment with magnificent views to the south over the river valley and Cold Fell. The old timber fort was about to be replaced by a large stone one with a rare basilica exercitatoria, or indoor drill hall.

9) Fanum Cocidi [?] (Bewcastle, Cumbria)

Six miles north of Banna, this outpost fort – which may have been called Fanum Cocidi – was manned by a cohort of Dacians (from modern Romania). Their job was to patrol the troubled no man’s land north of the wall.

When in Londinium… From sleeping with their hounds to gambling away their wages, how Roman Britons lived their lives in AD 130

The thrill of the chase At Hadrian’s Wall, hunting was the officers’ most eagerly anticipated pastime. They wrote to each other about their hounds and sent their friends requests for kit: “If you love me, brother, I ask that you send me hunting-nets,” wrote Flavius Cerialis from Vindolanda to his fellow officer Brocchus in the early second century.

Hunting hounds were well looked after. A contemporary writer recommended that they were fondled after a good chase and given a soft warm bed at night where, he advised: “It is best when they sleep with a man so that they become more affectionate and appreciate companionship.”

Two men carry a wild boar in an AD 300 mosaic. Hunting was among Roman army officers’ favourite pastimes. © Alamy

No-frills fashionAnyone coming from the Mediterranean, and especially from places like Egypt and Syria, would have been struck by the plainness of British clothes. Although cloth was dyed – red with imported madder or bedstraw, purple with local lichens, blue with woad, and yellow with weld – there were none of the fancy weaves or brocades to be found further east.

In these damp islands people sported eminently sensible – and excellent quality – medium-weight diamond, herringbone and plain 2/2 twill. While there were those who wore imported damask silks, diamond twill and checks were the distinctively north-west European Celtic look.

A curse be upon you“Lady Nemesis, I give thee a cloak and a pair of Gallic sandals; let him who took them not redeem them (unless) with his own blood.” This curse, written in Latin on a lead tablet in Wales, was typical of hundreds found in Britain. The British did not curse rival lovers as elsewhere in the empire but instead were obsessed with theft and property rights.

Nemesis was a goddess who could distribute both good and bad fortune, success or failure, even life and death. She is often associated with amphitheatres and the Welsh curse quoted above was found at the amphitheatre at Caerleon.

Britons beseeched the gods to punish their enemies on curse tablets like this. © Freia Turland Photography

Beer, dice and knife attacksItalian and Greek wine was available in Britain but most of it came from Gaul, imported in wooden barrels. Soldiers of the ranks enjoyed beer, and snacked on shellfish in the taverns while playing games such as ludus duodecimo scriptorium perhaps, which was a bit like backgammon but played with dice.

Taverns were louche places, where barmaids were notorious for offering more than just drinks. Buried under the clay floor in the back room of an inn at Vercovicium (Housesteads) on Hadrian’s Wall are the carefully concealed bodies of a woman and a man, the latter with the tip of the knife that killed him still wedged between his ribs.

Men play dice in a third-century AD mosaic. © Alamy

Blood sportsAlongside the crocodiles, lions and antelopes shipped to Rome to appear in the arena were bears and stags from Britain and wolfhounds from Ireland. The logistics of capturing the animals and transporting them overseas were considerable and many died en route or arrived in a miserable condition.

In the amphitheatres of Britain there is no record of imported animals but evidence for wolves (in Wales), bulls and bears. Travelling schools of gladiators, sponsored by the state, appeared in Britain while on tour through Gaul, Spain and Germany.

Bronwen Riley is a historian and author who is series editor of the English Heritage Red Guides.

Hadrian’s Wall dissects the countryside of northern England. By AD 130, the wall’s turf sections were being rebuilt in stone and many adaptations being carried out, a sure sign that trouble was afoot. © Corbis

Hadrian’s Wall dissects the countryside of northern England. By AD 130, the wall’s turf sections were being rebuilt in stone and many adaptations being carried out, a sure sign that trouble was afoot. © Corbis Britannia lay at the north-westernmost boundaries of an empire so vast that it encompassed “the ocean where the sun god rises to the place where he sinks”. Although an imperial province for more than 80 years, ever since the emperor Claudius, accompanied by elephants, claimed it for Rome, in AD 130 Britannia and her inhabitants remained a byword for a remote land and distant people.

For anyone making the perilous journey across to Britannia’s shores, expectations, as far as we can tell, were low. The natives were considered to be uncultured and generally unpromising, though their plain clothes were of most excellent quality wool and their hunting hounds were deemed to be effective, if unprepossessing in looks. The climate, too, left much to be desired. Here was a place where the rain fell, the sun was seldom seen, and a thick mist was said to rise from the marshes “so that the atmosphere in the country is always gloomy”.

Although the crossing from Gesoriacum (Boulogne) to Rutupiae (Richborough in Kent) was comparatively short (somewhere between six and eight hours), the symbolic distance was immense. For to set foot on a ship bound for Britannia was to venture into Oceanus, that immeasurable expanse of sea, full of monsters and perilous tides which led to a land of unfathomable people.

Although the tentacles of Roman administration via the army had, by AD 130, reached into the furthest corners of the province and the island had been scrupulously measured and recorded, in terms at least of potential revenue, Britannia represented the untamed and unknown.

Tattooed bodiesCensuses may have been carried out for tax purposes, records made of landholdings, distances measured between places, roads built to Roman standards and all rivers and crossing points marked down, but this didn’t mean that the Romans felt any more sympathetic towards the island’s inhabitants. The Britons were regarded as somewhat uncouth, their bodies tattooed with patterns and pictures of all kinds of animals.

Serving officers on Hadrian’s Wall, who referred to Britons disparagingly as Brittunculi or ‘Britlings’, clearly had not progressed very much in their outlook since the days of Cicero who, when writing about his brother on campaign in Britain during Julius Caesar’s expedition there in 54 BC, joked that none of the British were expected to be accomplished in literature or music. The stereotype persisted into the fourth century, when poets were still portraying Britannia with cheeks tattooed, “clothed in the skin of some Caledonian beast”.

By AD 130, many provincials from elsewhere in the empire had made it to the top of Roman society (two successive emperors, Trajan and Hadrian, hailed from Spanish families, the Ulpii and the Aelii) and the Gauls were making vast fortunes in trade, and clawing their way into the senate. There is no record of any Britons doing the same at this period, though many were serving as auxiliary soldiers in far-flung places, such as the cohort of Britons then in Dacia (modern Romania).

British exports tended to be rather unglamorous – tin, lead, hides and slaves. If asked what British products they had bought recently, shoppers on the streets of Rome may have been pushed for an answer. Blankets or rush baskets, perhaps? That said, anyone keen on hunting may have known of – or even possessed – one of their famously ugly but skilful hounds, and the gourmands among them tasted oysters shipped in from Kent.

Having arrived in Britannia, visitors may have had to adjust their literary preconceptions, for by AD 130 the main towns and cities of Britain conformed more or less to a Roman model with some idiosyncratic flourishes. Although houses in both the town and country were generally modest in size – the age of great villa building in Britain had yet to come – the province boasted some magnificent civic architecture.

The gateway to Britannia was the port of Rutupiae on the Kent coast, where passengers alighting on the British shore were greeted by a monumental arch, in gleaming Italian marble, one of the largest in the empire.