MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 83

September 10, 2016

Everything you know about 17th-century London is wrong

History Extra

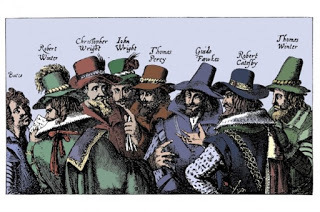

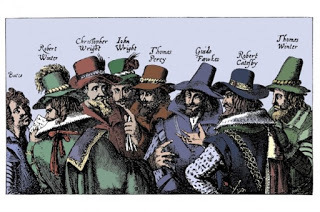

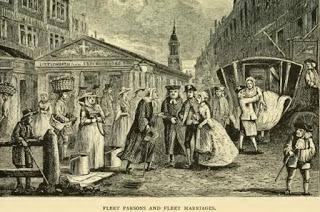

Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plotters, 1605. Contrary to popular belief, Guy Fawkes was not executed for masterminding the Gunpowder Plot. (Photo by Print Collector/Getty Images)

Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plotters, 1605. Contrary to popular belief, Guy Fawkes was not executed for masterminding the Gunpowder Plot. (Photo by Print Collector/Getty Images)

In a city as historically dense as London, facts and faces can get jumbled as readily as oats in a box of muesli. Take the statue of Lady Justice on top of the Old Bailey [the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales], for example: many believe that she is blindfolded; she is not. Tourists look for the Union Flag above Buckingham Palace as a sign that the queen is at home; in fact it means she’s away. Even cast-iron ‘truths’ can turn out to be distortions: while the Tower of London did indeed see famous beheadings in the Tudor period, more than half of all executions in the fortress were conducted in the 20th century.

Of all eras, the 17th century seems to have generated more mistruths than most. This was a period that saw the beginnings of the press (newspapers), the first stirrings of scientific discourse and the city’s great chroniclers such as Pepys, Evelyn and, latterly, Defoe. It was also a time of tumultuous events, with plague, war, fire and political upheaval striking the nation as rarely before. Many of us carry around a working knowledge of these heady days, but how much of it is accurate? Here are four myths busted…

Guy Fawkes was not executed for masterminding the Gunpowder PlotThe century began with a bang. Almost. Guy Fawkes and co-conspirators famously plotted to blow up the Houses of Parliament, and the king with them. But it didn’t quite happen as many of us believe...

Every year, thousands of people make life-size effigies of the Catholic Yorkshireman, then set him on fire for the delight of their children. This is the man who plotted not just to bring down the system, but to blow up the king and his government too. In 1605, his actions were branded as treachery and treason. Today, we would call him a terrorist. But does Fawkes truly deserve the animosity of centuries?

His story is well known to every British school child. Guy Fawkes, real name Guido Fawkes, was angry at the state for its anti-Catholic prejudice. He brought together a team of conspirators intent on killing King James and his cronies during the State Opening of Parliament. Under the cover of night they broke into the House of Lords and loaded the cellar with barrels of gunpowder. The plot was, however, discovered on the eve of success, thanks to an anonymous tip-off. Fawkes was arrested, tortured and eventually gave the names of his auxiliaries. All were eventually captured and executed.

But this story is wrong in almost every respect.

Fawkes was not the ringleader. He was merely the first to be captured when the guards caught him red-handed and alone in the gunpowder cellar. The true mastermind was Robert Catesby. He led the team of 13 conspirators – Fawkes had no special place in the hierarchy, but was chosen to light the fuse at the assassination attempt. Nor was he born as Guido. That was a nickname he adopted while fighting for the Catholic Spanish in the Eighty Years’ War. Plain old Guy was his birth name.

And contrary to popular belief, the conspirators did not break into the Houses of Parliament. In fact, they took a lease out on the undercroft and had lawful access to the space. The gunpowder stash was built up over a number of months before the plague-delayed opening of Parliament on 5 November.

Fawkes did indeed receive the death penalty for High Treason, and was dragged to the gallows in Old Palace Yard to be hanged, drawn and quartered. This terrifying procedure would first see the condemned man dangle by the neck until barely conscious. After being cut down, his genitals would be sliced off and his belly opened. His entrails would then be scooped out and burnt with his testicles. Finally, the fading man would be chopped into parts, which would, in gory sequel, be displayed in public locations as a warning to others.

It didn’t quite happen like that, though. Before the executioner could begin the gruesome act, Fawkes leapt from the gallows, breaking his neck and sparing himself the excruciating fate the law had set out for him. In short, he was not executed, but took his own life.

Other conspirators also escaped the chop. Ringleader Robert Catesby and several others were killed in a gunfight with authorities in Staffordshire, while another plotter died from illness at the Tower of London before he could stand trial.

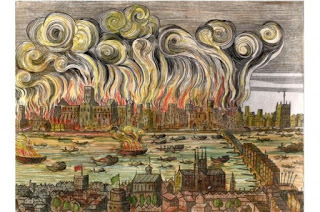

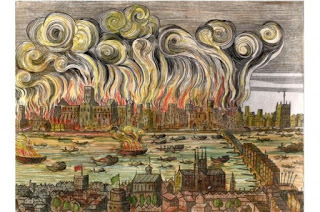

The Great Fire of London was not the greatest of all London’s firesSeptember 1666, and it seemed to Londoners that the whole world was aflame. Samuel Pepys described the scene:

“We stayed till, it being darkish, we saw the fire as only one entire arch of fire from this to the other side the bridge, and in a bow up the hill for an arch of above a mile long: it made me weep to see it. The churches, houses, and all on fire and flaming at once; and a horrid noise the flames made, and the cracking of houses at their ruin.”

The Great Fire of London, as it came to be known, certainly devastated the City of London. An estimated 80,000 people lived there; 70,000 became homeless. Almost all the City of London’s churches were destroyed, including the medieval St Paul’s Cathedral. To those who bore witness, it must have felt like the greatest calamity in the city’s history.

In many ways, however, the Great Fire was just another of many such tragedies, because London has fallen to conflagration on numerous occasions. The earliest came at the hands of Boudica in around 60 AD, less than 20 years after the founding of the Roman town. Suetonius, the Governor of Britain, had to decide where to make his stand against Boudica’s rebellion. London was not ideal as a battleground and he pulled all troops out of the town. The city was defenceless, and the Queen of the Iceni was merciless. If Roman accounts are to be believed, she slaughtered thousands of inhabitants and set the town ablaze. If you dig deep enough, anywhere in the City of London you can still find a thick destruction layer of ash and red debris from this conflagration.

Other fires followed. Archaeology suggests another great Roman fire around 125 AD, in which all but the most sturdy buildings were consumed. We do not know the death toll. 1087, the year that William the Conqueror died, also saw a mighty blaze comparable to the Great Fire. It, too, destroyed St Paul’s Cathedral, wrecking “other churches and the largest and fairest part of the whole city”. The calamity was repeated just two generations later in the great fire of 1135. In fact, fires were such a common occurrence that the medieval city must have remained as pockmarked as its disease-ravaged denizens.

Samuel Pepys. Colourised version of the painting by John Hayls. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

The most tragic blaze occurred in 1212. It started in Southwark, taking hold of St Mary Overie (what today we call Southwark Cathedral). Londoners rushed from the city onto the newly built London Bridge to lend assistance, and to gawp. Alas, the wind was up. Sparks from the fire arced across the Thames to the northern end of the bridge, where they took hold. Trapped between the two fires, the horrified onlookers succumbed to smoke inhalation, or jumped to their ends in the treacherous Thames. Later accounts put the subsequent death toll as high as 3,000. Although likely to be an exaggeration, there is no doubt that this incident ranks as one of London’s worst disasters. By comparison, the Great Fire of 1666 is thought to have claimed just six lives, according to official records (but amid such confusion, and with the limitations of 17th century communication, it would be impossible to accurately account for everybody. Many more people surely lost their lives in the crowded tenements of the City of London).

The early fires of London are mostly obscure today. We remember the 1666 conflagration partly because it was so well recorded by Pepys and others, but also because it served as the fountainhead for so much of the modern city. The cathedral and churches of Sir Christopher Wren soon arose like gleaming white phoenixes. Brick and stone replaced wood and straw as the chief building materials. The fire also accelerated the growth of what would become the West End. The fields of Covent Garden and Holborn had already disappeared beneath a tide of development. The fire served as a fillip for more house building around the periphery of the City of London. In the years immediately following the fire, districts such as Soho and Bloomsbury began to spread out as wealthy merchants and nobles sought new housing away from the ancient centre. Like a rose bush pruned, London must be disfigured before it can grow.

The Great Fire of London did not wipe out the Great PlagueWhich brings us on to one of the great canards in London’s history. Did the 1666 fire really put an end to the Great Plague? It’s a claim that’s tempted educators for centuries. The timing looks perfect: everybody falls ill in 1665, then a vast, cleansing fire wipes out the disease in 1666. A neat and tidy ‘just-so’ story, but correlation does not always imply causation.

For starters, the plague had eased considerably by September 1666, the month of the fire. Already by February that year the Royal Court and entourage had moved back to the capital. In March, the Lord Chancellor deemed London as crowded as it had ever been seen. When the Great Fire swept through London half a year later, it struck a city that was already well on the road to recovery. It should also be remembered that the fire only damaged the City proper. The suburbs, including plague-intensive regions such as St Giles, were completely untouched by the blaze. The fire had no direct effect on the disease in these quarters.

While the Great Fire did not wipe out the plague, it did help bring about conditions that would be less favourable to further outbreaks. The city was rebuilt to better standards, and (slightly) more sanitary conditions prevailed. These improvements were no doubt a contributory factor in keeping plague at bay in the centuries since.

'The Pestilence 1665’. Illustration of figures burying bodies in the aftermath of the plague. (Photo by Guildhall Library & Art Gallery/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

A few other myths persist about the Great Plague of 1665–66. It was by no means the only disease to ravage England, nor the worst. The so-called Black Death of 1348–1350 wiped out a much higher percentage of the population – perhaps a third of England. By contrast, the 1665 plague was largely centred on London. It killed 15 per cent of those in the capital, and therefore an even smaller percentage across the country as a whole.

Earlier 17th century epidemics, notably in 1603 and 1625, were not quite so virulent as the Great Plague of 1665, but they weren’t far off. The 1665 epidemic gets more attention for several reasons. It was the last big outbreak of plague in this country. Many contemporary accounts survive, unlike earlier medieval plagues. And it just so happened to occur at a time when plenty of other major events were taking place. That the plague struck London not long after the restoration of the monarchy and just before the Great Fire of 1666 helps secure its place in our historical memory.

Plague doctors did not go about their business in beaked masksFinally, we can also pooh-pooh one of the most terrifying icons of the plague: the beaked helmet. Visual depictions of the disease often show sinister figures roaming the streets in these eccentric headpieces. They served as a kind of primitive gas mask for plague doctors. The beak-like appendage would be stuffed with lavender and other sweet smelling aromatics in a bid to ward off the foul odours often blamed for the plague. Accentuating the macabre look, the doctors would also sport a broad-brimmed hat and ankle-length overcoat. A wooden cane completed the costume, and allowed physicians to examine patients without the need for personal contact.

A plague doctor in protective clothing, c1656. Engraving by Paul Furst after J Colombina. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

While this protective gear is well documented on the continent, particularly in Italy, there is no good evidence that the costume was ever worn in London. It can’t be entirely ruled out, but one would have thought that such a distinctive ensemble would have made it onto the pages of Pepys’s diary, or some other first-hand account of the plague.

Matt Brown is the author of Everything You Know About London Is Wrong (Batsford, 2016).

Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plotters, 1605. Contrary to popular belief, Guy Fawkes was not executed for masterminding the Gunpowder Plot. (Photo by Print Collector/Getty Images)

Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plotters, 1605. Contrary to popular belief, Guy Fawkes was not executed for masterminding the Gunpowder Plot. (Photo by Print Collector/Getty Images) In a city as historically dense as London, facts and faces can get jumbled as readily as oats in a box of muesli. Take the statue of Lady Justice on top of the Old Bailey [the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales], for example: many believe that she is blindfolded; she is not. Tourists look for the Union Flag above Buckingham Palace as a sign that the queen is at home; in fact it means she’s away. Even cast-iron ‘truths’ can turn out to be distortions: while the Tower of London did indeed see famous beheadings in the Tudor period, more than half of all executions in the fortress were conducted in the 20th century.

Of all eras, the 17th century seems to have generated more mistruths than most. This was a period that saw the beginnings of the press (newspapers), the first stirrings of scientific discourse and the city’s great chroniclers such as Pepys, Evelyn and, latterly, Defoe. It was also a time of tumultuous events, with plague, war, fire and political upheaval striking the nation as rarely before. Many of us carry around a working knowledge of these heady days, but how much of it is accurate? Here are four myths busted…

Guy Fawkes was not executed for masterminding the Gunpowder PlotThe century began with a bang. Almost. Guy Fawkes and co-conspirators famously plotted to blow up the Houses of Parliament, and the king with them. But it didn’t quite happen as many of us believe...

Every year, thousands of people make life-size effigies of the Catholic Yorkshireman, then set him on fire for the delight of their children. This is the man who plotted not just to bring down the system, but to blow up the king and his government too. In 1605, his actions were branded as treachery and treason. Today, we would call him a terrorist. But does Fawkes truly deserve the animosity of centuries?

His story is well known to every British school child. Guy Fawkes, real name Guido Fawkes, was angry at the state for its anti-Catholic prejudice. He brought together a team of conspirators intent on killing King James and his cronies during the State Opening of Parliament. Under the cover of night they broke into the House of Lords and loaded the cellar with barrels of gunpowder. The plot was, however, discovered on the eve of success, thanks to an anonymous tip-off. Fawkes was arrested, tortured and eventually gave the names of his auxiliaries. All were eventually captured and executed.

But this story is wrong in almost every respect.

Fawkes was not the ringleader. He was merely the first to be captured when the guards caught him red-handed and alone in the gunpowder cellar. The true mastermind was Robert Catesby. He led the team of 13 conspirators – Fawkes had no special place in the hierarchy, but was chosen to light the fuse at the assassination attempt. Nor was he born as Guido. That was a nickname he adopted while fighting for the Catholic Spanish in the Eighty Years’ War. Plain old Guy was his birth name.

And contrary to popular belief, the conspirators did not break into the Houses of Parliament. In fact, they took a lease out on the undercroft and had lawful access to the space. The gunpowder stash was built up over a number of months before the plague-delayed opening of Parliament on 5 November.

Fawkes did indeed receive the death penalty for High Treason, and was dragged to the gallows in Old Palace Yard to be hanged, drawn and quartered. This terrifying procedure would first see the condemned man dangle by the neck until barely conscious. After being cut down, his genitals would be sliced off and his belly opened. His entrails would then be scooped out and burnt with his testicles. Finally, the fading man would be chopped into parts, which would, in gory sequel, be displayed in public locations as a warning to others.

It didn’t quite happen like that, though. Before the executioner could begin the gruesome act, Fawkes leapt from the gallows, breaking his neck and sparing himself the excruciating fate the law had set out for him. In short, he was not executed, but took his own life.

Other conspirators also escaped the chop. Ringleader Robert Catesby and several others were killed in a gunfight with authorities in Staffordshire, while another plotter died from illness at the Tower of London before he could stand trial.

The Great Fire of London was not the greatest of all London’s firesSeptember 1666, and it seemed to Londoners that the whole world was aflame. Samuel Pepys described the scene:

“We stayed till, it being darkish, we saw the fire as only one entire arch of fire from this to the other side the bridge, and in a bow up the hill for an arch of above a mile long: it made me weep to see it. The churches, houses, and all on fire and flaming at once; and a horrid noise the flames made, and the cracking of houses at their ruin.”

The Great Fire of London, as it came to be known, certainly devastated the City of London. An estimated 80,000 people lived there; 70,000 became homeless. Almost all the City of London’s churches were destroyed, including the medieval St Paul’s Cathedral. To those who bore witness, it must have felt like the greatest calamity in the city’s history.

In many ways, however, the Great Fire was just another of many such tragedies, because London has fallen to conflagration on numerous occasions. The earliest came at the hands of Boudica in around 60 AD, less than 20 years after the founding of the Roman town. Suetonius, the Governor of Britain, had to decide where to make his stand against Boudica’s rebellion. London was not ideal as a battleground and he pulled all troops out of the town. The city was defenceless, and the Queen of the Iceni was merciless. If Roman accounts are to be believed, she slaughtered thousands of inhabitants and set the town ablaze. If you dig deep enough, anywhere in the City of London you can still find a thick destruction layer of ash and red debris from this conflagration.

Other fires followed. Archaeology suggests another great Roman fire around 125 AD, in which all but the most sturdy buildings were consumed. We do not know the death toll. 1087, the year that William the Conqueror died, also saw a mighty blaze comparable to the Great Fire. It, too, destroyed St Paul’s Cathedral, wrecking “other churches and the largest and fairest part of the whole city”. The calamity was repeated just two generations later in the great fire of 1135. In fact, fires were such a common occurrence that the medieval city must have remained as pockmarked as its disease-ravaged denizens.

Samuel Pepys. Colourised version of the painting by John Hayls. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

The most tragic blaze occurred in 1212. It started in Southwark, taking hold of St Mary Overie (what today we call Southwark Cathedral). Londoners rushed from the city onto the newly built London Bridge to lend assistance, and to gawp. Alas, the wind was up. Sparks from the fire arced across the Thames to the northern end of the bridge, where they took hold. Trapped between the two fires, the horrified onlookers succumbed to smoke inhalation, or jumped to their ends in the treacherous Thames. Later accounts put the subsequent death toll as high as 3,000. Although likely to be an exaggeration, there is no doubt that this incident ranks as one of London’s worst disasters. By comparison, the Great Fire of 1666 is thought to have claimed just six lives, according to official records (but amid such confusion, and with the limitations of 17th century communication, it would be impossible to accurately account for everybody. Many more people surely lost their lives in the crowded tenements of the City of London).

The early fires of London are mostly obscure today. We remember the 1666 conflagration partly because it was so well recorded by Pepys and others, but also because it served as the fountainhead for so much of the modern city. The cathedral and churches of Sir Christopher Wren soon arose like gleaming white phoenixes. Brick and stone replaced wood and straw as the chief building materials. The fire also accelerated the growth of what would become the West End. The fields of Covent Garden and Holborn had already disappeared beneath a tide of development. The fire served as a fillip for more house building around the periphery of the City of London. In the years immediately following the fire, districts such as Soho and Bloomsbury began to spread out as wealthy merchants and nobles sought new housing away from the ancient centre. Like a rose bush pruned, London must be disfigured before it can grow.

The Great Fire of London did not wipe out the Great PlagueWhich brings us on to one of the great canards in London’s history. Did the 1666 fire really put an end to the Great Plague? It’s a claim that’s tempted educators for centuries. The timing looks perfect: everybody falls ill in 1665, then a vast, cleansing fire wipes out the disease in 1666. A neat and tidy ‘just-so’ story, but correlation does not always imply causation.

For starters, the plague had eased considerably by September 1666, the month of the fire. Already by February that year the Royal Court and entourage had moved back to the capital. In March, the Lord Chancellor deemed London as crowded as it had ever been seen. When the Great Fire swept through London half a year later, it struck a city that was already well on the road to recovery. It should also be remembered that the fire only damaged the City proper. The suburbs, including plague-intensive regions such as St Giles, were completely untouched by the blaze. The fire had no direct effect on the disease in these quarters.

While the Great Fire did not wipe out the plague, it did help bring about conditions that would be less favourable to further outbreaks. The city was rebuilt to better standards, and (slightly) more sanitary conditions prevailed. These improvements were no doubt a contributory factor in keeping plague at bay in the centuries since.

'The Pestilence 1665’. Illustration of figures burying bodies in the aftermath of the plague. (Photo by Guildhall Library & Art Gallery/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

A few other myths persist about the Great Plague of 1665–66. It was by no means the only disease to ravage England, nor the worst. The so-called Black Death of 1348–1350 wiped out a much higher percentage of the population – perhaps a third of England. By contrast, the 1665 plague was largely centred on London. It killed 15 per cent of those in the capital, and therefore an even smaller percentage across the country as a whole.

Earlier 17th century epidemics, notably in 1603 and 1625, were not quite so virulent as the Great Plague of 1665, but they weren’t far off. The 1665 epidemic gets more attention for several reasons. It was the last big outbreak of plague in this country. Many contemporary accounts survive, unlike earlier medieval plagues. And it just so happened to occur at a time when plenty of other major events were taking place. That the plague struck London not long after the restoration of the monarchy and just before the Great Fire of 1666 helps secure its place in our historical memory.

Plague doctors did not go about their business in beaked masksFinally, we can also pooh-pooh one of the most terrifying icons of the plague: the beaked helmet. Visual depictions of the disease often show sinister figures roaming the streets in these eccentric headpieces. They served as a kind of primitive gas mask for plague doctors. The beak-like appendage would be stuffed with lavender and other sweet smelling aromatics in a bid to ward off the foul odours often blamed for the plague. Accentuating the macabre look, the doctors would also sport a broad-brimmed hat and ankle-length overcoat. A wooden cane completed the costume, and allowed physicians to examine patients without the need for personal contact.

A plague doctor in protective clothing, c1656. Engraving by Paul Furst after J Colombina. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

While this protective gear is well documented on the continent, particularly in Italy, there is no good evidence that the costume was ever worn in London. It can’t be entirely ruled out, but one would have thought that such a distinctive ensemble would have made it onto the pages of Pepys’s diary, or some other first-hand account of the plague.

Matt Brown is the author of Everything You Know About London Is Wrong (Batsford, 2016).

Published on September 10, 2016 03:00

September 9, 2016

Big Ben blown up: the radio sketch that sent Britain into panic

History Extra

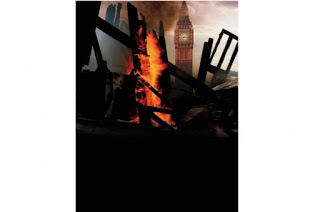

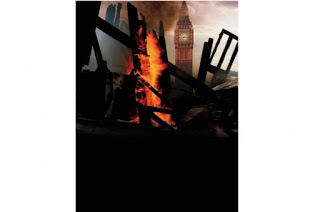

In 1926 a short, and seemingly innocuous, radio sketch sparked panic in Britain. (Getty Images)

In 1926 a short, and seemingly innocuous, radio sketch sparked panic in Britain. (Getty Images)

The politics of fear has become central to statecraft, and the modern world is badly scared. In the past, as well, full-blown panic seems to have flared up with almost ludicrous ease. On the wintry evening of 16 January 1926, for instance, many people in Britain panicked after listening to a short, and seemingly innocuous, radio sketch.

Its author was 38-year-old Father Ronald Arbuthnott Knox, a convivial priest with a taste for New Testament commentary, Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, and detective stories. Father Ronald Knox’s play, Broadcasting from the Barricades was transmitted at 7.40pm on Saturday evening, 16 January, from the George Street Studios of the BBC in Edinburgh. After being prefaced by a statement informing listeners that it was a work of humour, the play took the form of a news broadcast, interrupted by music from the Savoy Hotel, in which Father Knox described an unemployed crowd that went wild.

The newsreader announced that the unemployed, stirred to action by troublemakers such as Mr Popplebury, the Secretary of the National Movement for Abolishing Theatre Queues, had rioted. The red tide of revolution had swept over the great landmarks of London: Trafalgar Square had been overrun; the National Gallery sacked; and Big Ben had been reduced to a heap of rubble by mortar attack. Henceforth, Greenwich time would be tolled by the repeating watch of Uncle Leslie, a popular children’s storyteller from Edinburgh.

There was murder, too. The newsreader reported that Sir Theophilus Gooch of the Committee for the Inspection of Insanitary Dwellings had been roasted alive in Trafalgar Square. Mr Wotherspoon, Minister of Transport (a position of huge importance, then as now), had been hung from a lamp post in the Vauxhall Bridge Road. A moment later, the BBC issued a formal apology: Wotherspoon had not been hung from a lamp post but from a tramway post.

The play’s author Father Ronald Knox (second from right) as a guest on the BBC’s Brains Trust in 1941. (BBC Picture Archives)

The play’s author Father Ronald Knox (second from right) as a guest on the BBC’s Brains Trust in 1941. (BBC Picture Archives)

Fiddling while the city burnsThe listeners were once again serenaded with the Savoy Band but this was suddenly interrupted with news that the crowd had blown up the Savoy Hotel. Finally, the crowd was reported to be moving toward BBC London offices. The final words uttered were: “One moment please ... Mr Popplebury, secretary of the National Movement for Abolishing Theatre Queues, with several other members of the crowd, is now in the waiting room. They are reading copies of the Radio Times. Good-night everybody; good-night.”

Reading this satire today, it seems unbelievable that many radio listeners panicked. But that is what happened. The 20-minute programme was scarcely over before listeners all over the country became agitated. JCS MacGregor had been involved creating realistic sound effects (an unusual development in the 1920s) for the broadcast. It fell to him to explain that the show had been satire, not news. In his words: “Knox and the producer had scarcely left the building, and the debris of the Savoy Hotel was still lying about in the studio, when the telephone rang. Was it really true, asked an agitated voice, that revolution had broken out in London? I gave reassurances ... The next caller was more difficult. His wife had a weak heart, and had fainted at the news; and when he gathered from me that the whole thing was fictitious, he exploded. What, he asked with some vigour, did the BBC mean by it? Did we realise that we had grossly misled the country, and were playing into the hands of the Bolshevists?”

Other listeners began besieging local police stations, radio stations, newspaper offices, and the Savoy Hotel, demanding “how soon the tide of civil war might be expected to sweep in [our] direction”. The manager of the Savoy calculated that in addition to around 200 local calls, the hotel answered hundreds of trunk calls from all parts of the country, including Ireland, Scotland, Hull, Manchester, Newcastle and Leeds, asking whether they should cancel their room bookings. Others sought reassurance about the safety of friends staying at the hotel.

The Savoy Hotel – a BBC radio broadcast in 1926 reported that it had been blown up. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

In Newcastle, the sheriff was nervously uncertain about what precautions he should be taking to ensure that anarchy did not spread to his part of the country, while the wife of the lord mayor of Newcastle was reported to have been “greatly upset” at being unable to contact her husband (who was out at dinner) to inform him about the rising “red tide of revolution”. The Irish Telegraph could not restrain from reporting that numerous listeners rang their offices, breathlessly enquiring: “Is it true that the House of Commons is blown up?”

Luckily, it was a short-lived panic, over within 24 hours. Those responsible for the broadcast were amazed that listeners had been fooled by tales of revolution led by a Mr Popplebury, Secretary of the National Movement for Abolishing Theatre Queues. The idea that the children’s character, Uncle Leslie, would take over sounding the time after Big Ben’s demise was also clearly ludicrous. But the BBC was forced to apologise: “London is safe, Big Ben is still chiming and all is well”, it announced. The apology added, however, that it was “hardly credible that if we were giving out news of such a national crisis we should intersperse snatches of dance music”. Nevertheless, it bowed to pressure to “take no risks with its public’s average standard of intelligence” in the future and Knox refused to speak on radio again until 1930.

Why might such a satirical programme prove so frightening? In part, the panic caused by the broadcast reflected wider economic and political insecurities ravaging the nation. Left-wing papers were quick to identify class-based fears to be at the heart of the panic. “Supposing the imaginary news announcer told his listeners that a Tory mob had marched on Eccleston Square and blown up the offices of the TUC!”, exclaimed the Daily Herald.

The Leeds Weekly Citizen was also queasy about “this kind of allusion to the unemployed, at a time when so many are suffering so badly from the failure of our social system to provide them with work and sustenance”. By 1926, an estimated 12.5 per cent of workers were unemployed, and the numbers were rising. Furthermore, a few months before Knox’s broadcast, miners had risen up with the cry “enough is enough”, striking against bosses who threatened their already precarious livelihoods.

Unemployment demonstration c1920: radio listeners were receptive to the broadcast in the era’s climate of social unrest. (Getty Images)

Unemployment demonstration c1920: radio listeners were receptive to the broadcast in the era’s climate of social unrest. (Getty Images)

Another development alarming the middle class was the polarisation of politics in Britain, with the establishment in 1920 of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Although the Communist Party was feared out of all proportion to its membership, “Red internationalism” rendered the Communists a threat to “British values”. The Daily Herald reported that the broadcast incited the “political passions” of listeners. The paper disclosed that at one dinner party, the broadcast inflamed the “violent anti-Labour convictions” of the host, at which point he began to angrily lecture his guests about the pernicious events allegedly taking place in London. Might “the left” have succeeded in mobilising disaffected workers?

Media coverage of Father Knox’s Broadcast from the Barricades was quick to link the broadcast to an alleged Communist threat. For instance, on the same page that the Daily Mail published its account of the panic, it printed a column entitled “Lying Propaganda”. This informed readers that around 250,000 broadsheets “full of illiterate Communist violence and shameful perversions of truth” were being distributed weekly throughout the United Kingdom. “Their only object is to create hatred and discontent and to bring about a state of affairs which may give the disgusting tyranny of Communism a chance to seize upon this country”, the paper warned.

The fact that the news of a riotous crowd in London was broadcast on the radio was also crucial. BBC monopoly of the radio waves and its government-guaranteed political neutrality made radio news profoundly authoritative. As one panic-stricken person hoarsely maintained on the telephone to a journalist for a Liberal Welsh paper immediately after being informed that the broadcast was a hoax: “No ... there must be something in it, we have heard it over the wireless”.

When this call was followed by many others, even the journalist answering the telephone began to have his doubts, wondering if, after all, “there was not something in it”. Similarly, the Daily Mail reported that when people were told it was a hoax, they refused to believe it: “We have heard it on the wireless”, they reminded the sceptical newspaper reporters, “Why, we have even heard the explosions!” In 1926, radio had a unique ability to spark intense panic in its hapless listeners.

Joanna Bourke is professor of history at Birkbeck College and the author of Fear: A Cultural History (Virago, 2005).

In 1926 a short, and seemingly innocuous, radio sketch sparked panic in Britain. (Getty Images)

In 1926 a short, and seemingly innocuous, radio sketch sparked panic in Britain. (Getty Images) The politics of fear has become central to statecraft, and the modern world is badly scared. In the past, as well, full-blown panic seems to have flared up with almost ludicrous ease. On the wintry evening of 16 January 1926, for instance, many people in Britain panicked after listening to a short, and seemingly innocuous, radio sketch.

Its author was 38-year-old Father Ronald Arbuthnott Knox, a convivial priest with a taste for New Testament commentary, Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, and detective stories. Father Ronald Knox’s play, Broadcasting from the Barricades was transmitted at 7.40pm on Saturday evening, 16 January, from the George Street Studios of the BBC in Edinburgh. After being prefaced by a statement informing listeners that it was a work of humour, the play took the form of a news broadcast, interrupted by music from the Savoy Hotel, in which Father Knox described an unemployed crowd that went wild.

The newsreader announced that the unemployed, stirred to action by troublemakers such as Mr Popplebury, the Secretary of the National Movement for Abolishing Theatre Queues, had rioted. The red tide of revolution had swept over the great landmarks of London: Trafalgar Square had been overrun; the National Gallery sacked; and Big Ben had been reduced to a heap of rubble by mortar attack. Henceforth, Greenwich time would be tolled by the repeating watch of Uncle Leslie, a popular children’s storyteller from Edinburgh.

There was murder, too. The newsreader reported that Sir Theophilus Gooch of the Committee for the Inspection of Insanitary Dwellings had been roasted alive in Trafalgar Square. Mr Wotherspoon, Minister of Transport (a position of huge importance, then as now), had been hung from a lamp post in the Vauxhall Bridge Road. A moment later, the BBC issued a formal apology: Wotherspoon had not been hung from a lamp post but from a tramway post.

The play’s author Father Ronald Knox (second from right) as a guest on the BBC’s Brains Trust in 1941. (BBC Picture Archives)

The play’s author Father Ronald Knox (second from right) as a guest on the BBC’s Brains Trust in 1941. (BBC Picture Archives)Fiddling while the city burnsThe listeners were once again serenaded with the Savoy Band but this was suddenly interrupted with news that the crowd had blown up the Savoy Hotel. Finally, the crowd was reported to be moving toward BBC London offices. The final words uttered were: “One moment please ... Mr Popplebury, secretary of the National Movement for Abolishing Theatre Queues, with several other members of the crowd, is now in the waiting room. They are reading copies of the Radio Times. Good-night everybody; good-night.”

Reading this satire today, it seems unbelievable that many radio listeners panicked. But that is what happened. The 20-minute programme was scarcely over before listeners all over the country became agitated. JCS MacGregor had been involved creating realistic sound effects (an unusual development in the 1920s) for the broadcast. It fell to him to explain that the show had been satire, not news. In his words: “Knox and the producer had scarcely left the building, and the debris of the Savoy Hotel was still lying about in the studio, when the telephone rang. Was it really true, asked an agitated voice, that revolution had broken out in London? I gave reassurances ... The next caller was more difficult. His wife had a weak heart, and had fainted at the news; and when he gathered from me that the whole thing was fictitious, he exploded. What, he asked with some vigour, did the BBC mean by it? Did we realise that we had grossly misled the country, and were playing into the hands of the Bolshevists?”

Other listeners began besieging local police stations, radio stations, newspaper offices, and the Savoy Hotel, demanding “how soon the tide of civil war might be expected to sweep in [our] direction”. The manager of the Savoy calculated that in addition to around 200 local calls, the hotel answered hundreds of trunk calls from all parts of the country, including Ireland, Scotland, Hull, Manchester, Newcastle and Leeds, asking whether they should cancel their room bookings. Others sought reassurance about the safety of friends staying at the hotel.

The Savoy Hotel – a BBC radio broadcast in 1926 reported that it had been blown up. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

In Newcastle, the sheriff was nervously uncertain about what precautions he should be taking to ensure that anarchy did not spread to his part of the country, while the wife of the lord mayor of Newcastle was reported to have been “greatly upset” at being unable to contact her husband (who was out at dinner) to inform him about the rising “red tide of revolution”. The Irish Telegraph could not restrain from reporting that numerous listeners rang their offices, breathlessly enquiring: “Is it true that the House of Commons is blown up?”

Luckily, it was a short-lived panic, over within 24 hours. Those responsible for the broadcast were amazed that listeners had been fooled by tales of revolution led by a Mr Popplebury, Secretary of the National Movement for Abolishing Theatre Queues. The idea that the children’s character, Uncle Leslie, would take over sounding the time after Big Ben’s demise was also clearly ludicrous. But the BBC was forced to apologise: “London is safe, Big Ben is still chiming and all is well”, it announced. The apology added, however, that it was “hardly credible that if we were giving out news of such a national crisis we should intersperse snatches of dance music”. Nevertheless, it bowed to pressure to “take no risks with its public’s average standard of intelligence” in the future and Knox refused to speak on radio again until 1930.

Why might such a satirical programme prove so frightening? In part, the panic caused by the broadcast reflected wider economic and political insecurities ravaging the nation. Left-wing papers were quick to identify class-based fears to be at the heart of the panic. “Supposing the imaginary news announcer told his listeners that a Tory mob had marched on Eccleston Square and blown up the offices of the TUC!”, exclaimed the Daily Herald.

The Leeds Weekly Citizen was also queasy about “this kind of allusion to the unemployed, at a time when so many are suffering so badly from the failure of our social system to provide them with work and sustenance”. By 1926, an estimated 12.5 per cent of workers were unemployed, and the numbers were rising. Furthermore, a few months before Knox’s broadcast, miners had risen up with the cry “enough is enough”, striking against bosses who threatened their already precarious livelihoods.

Unemployment demonstration c1920: radio listeners were receptive to the broadcast in the era’s climate of social unrest. (Getty Images)

Unemployment demonstration c1920: radio listeners were receptive to the broadcast in the era’s climate of social unrest. (Getty Images)Another development alarming the middle class was the polarisation of politics in Britain, with the establishment in 1920 of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Although the Communist Party was feared out of all proportion to its membership, “Red internationalism” rendered the Communists a threat to “British values”. The Daily Herald reported that the broadcast incited the “political passions” of listeners. The paper disclosed that at one dinner party, the broadcast inflamed the “violent anti-Labour convictions” of the host, at which point he began to angrily lecture his guests about the pernicious events allegedly taking place in London. Might “the left” have succeeded in mobilising disaffected workers?

Media coverage of Father Knox’s Broadcast from the Barricades was quick to link the broadcast to an alleged Communist threat. For instance, on the same page that the Daily Mail published its account of the panic, it printed a column entitled “Lying Propaganda”. This informed readers that around 250,000 broadsheets “full of illiterate Communist violence and shameful perversions of truth” were being distributed weekly throughout the United Kingdom. “Their only object is to create hatred and discontent and to bring about a state of affairs which may give the disgusting tyranny of Communism a chance to seize upon this country”, the paper warned.

The fact that the news of a riotous crowd in London was broadcast on the radio was also crucial. BBC monopoly of the radio waves and its government-guaranteed political neutrality made radio news profoundly authoritative. As one panic-stricken person hoarsely maintained on the telephone to a journalist for a Liberal Welsh paper immediately after being informed that the broadcast was a hoax: “No ... there must be something in it, we have heard it over the wireless”.

When this call was followed by many others, even the journalist answering the telephone began to have his doubts, wondering if, after all, “there was not something in it”. Similarly, the Daily Mail reported that when people were told it was a hoax, they refused to believe it: “We have heard it on the wireless”, they reminded the sceptical newspaper reporters, “Why, we have even heard the explosions!” In 1926, radio had a unique ability to spark intense panic in its hapless listeners.

Joanna Bourke is professor of history at Birkbeck College and the author of Fear: A Cultural History (Virago, 2005).

Published on September 09, 2016 03:00

September 8, 2016

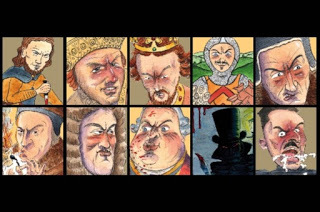

Murder, conspiracy and execution: six centuries of scandalous royal deaths

History Extra

The execution of Charles I, 30 January 1649. Charles’s death signalled the abolition of the monarchy, and the establishment of a republic in England. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The execution of Charles I, 30 January 1649. Charles’s death signalled the abolition of the monarchy, and the establishment of a republic in England. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Royal status brings with it privilege and power – but also danger, particularly the risk of assassination by those craving that power. From the Norman conquest to Charles’s execution in 1649, many British men, women and children of royal blood died in extraordinary circumstances. Deaths early in that period were often shrouded in mystery, but by the 17th century circumstances had changed to an extraordinary extent – for the first time an executioner severed the head of a king of England: Charles I, condemned by his own people…

William II meets his fate in the forestOn 2 August 1100 King William II, third son of William the Conqueror, was hunting in the New Forest. The chronicler William of Malmesbury reported that after dinner the king, nicknamed ‘Rufus’, went into the forest “attended by few persons”, notably a gentleman named Walter Tirel. While most of the king’s party “employed in the chase, were dispersed as chance directed,” Tirel remained with the king. As the sun began to set, William spotted a stag and “drawing his bow and letting fly an arrow, slightly wounded” it.

In his excitement the king began to run towards the injured target, and at that point Tirel, “conceiving a noble exploit” in that the king’s attention was occupied elsewhere, “pierced his breast with a fatal arrow”. William fell to the ground and Tirel, seeing that the king was dead, immediately “leaped swiftly upon his horse, and escaped by spurring him to his utmost speed”.

Upon discovering William’s body, the rest of his party fled and, in an attempt to protect their own interests, readied themselves to declare their allegiance to the next king. It was left to a few countrymen to convey the dead king’s corpse to Winchester Cathedral by cart, “the blood dripping from it all the way”.

Was William’s death an accident, or was it murder? An accident was possible, but there were many who believed otherwise. William’s younger brother immediately assumed the throne and swiftly had himself crowned Henry I. Henry had much to gain from his brother’s death, and Tirel may have been in his employ. William had, however, been an unpopular king, and his death was “lamented by few”.

King William II of England, aka William Rufus, c1100. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The Lionheart and eyeless ArtAlmost 100 years later, Henry I’s great-grandson, Richard I, also met a violent end at the point of an arrow, but in very different circumstances. Richard had spent the majority of his 10-year reign fighting abroad on crusade; he was a brave solider who inspired loyalty in his men. In 1199, while he was besieging the Château de Châlus-Chabrol, a crossbow bolt struck him in the shoulder. Though the shot did not kill him, it penetrated deep into his body. Though removal of the bolt by a surgeon was a painful ordeal, Richard survived – but before long the wound became infected and gangrene set in. It became clear that the king’s days were numbered, and on 6 April, 11 days after he was shot, “the man devoted to martial deeds, breathed his last.”

Richard was succeeded by his younger brother, John. However, though John was accepted as king of England he had a rival for his French lands: Arthur of Brittany, son of John’s brother, Geoffrey, who had died over a decade earlier. In 1202, John’s forces captured Arthur at Mirebeau, where the latter had been attempting to besiege the castle in which his grandmother (John’s mother), Eleanor of Aquitaine, was sheltering. Arthur was taken to Falaise, where – it was later claimed – John gave orders for his 16-year-old nephew to be “deprived of his eyes and genitals”, but the jailer refused to obey such a cruel command. Shortly afterwards, the boy was moved to Rouen where, on the evening of 3 April 1203, it seems that John himself, “drunk with wine and possessed of the Devil”, killed Arthur personally. The young boy’s lifeless body was reputedly weighed down with a heavy stone and thrown into the river Seine.

In the two centuries after the murder of Arthur of Brittany, both Edward II and Richard II were deposed. The latter was almost certainly starved to death in Pontefract Castle, but controversy still surrounds the end of Edward II – he may have been murdered in Berkeley Castle, but several modern historians are of the opinion that he escaped abroad.

Richard I, aka ‘Richard the Lionheart’, depicted plunging his fist into a lion's throat, c1180. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The bloody Wars of the RosesIn the middle of the 15th century, the Wars of the Roses broke out, causing a profusion of bloodshed that did not exclude royal or noble families. After a struggle that saw the Lancastrian King Henry VI deposed in favour of the Yorkist Edward IV, and a brief period of restoration for Henry VI (commonly referred to as the readeption), on 4 May 1471 the armies of Lancaster and York met at Tewkesbury, where Edward IV won “a famous victory”. It was a fierce battle during which around 2,000 Lancastrians were slain, and the battlefield is still referred to as ‘Bloody Meadow.’

For Henry’s son and heir, the 18-year-old Prince Edward of Lancaster, Tewkesbury had been his first experience of war, and one that he would not survive. Reports of the precise manner of the prince’s death vary: most sources state that the he was killed in the field, whereas the Yorkist author of the Arrivall of Edward IV, who claimed to be a servant of Edward IV’s and a witness to many of the events about which he wrote, asserts that Edward “was taken fleeing to the townwards, and slain in the field”. Later Tudor historians, however, implied that the prince had been murdered “by the avenging hands of certain persons,” on the orders of Edward IV. Whatever the circumstances, the Lancastrian heir had been removed; now all that remained was for his father to be eliminated.

While the battle of Tewkesbury raged, Henry VI was a prisoner in the Tower of London. Following his victory, Edward IV travelled to London in triumph, arriving on 21 May. That same evening, Henry VI was reportedly praying in his oratory within the Wakefield Tower when he “was put to death”. Though the author of the Arrivall stated that Henry died of “pure displeasure and melancholy” as a result of being told of the death of his son, there is little doubt that he died violently. The examination of his skull in 1911 revealed that to one piece “there was still attached some of the hair, which was brown in colour, save in one place, where it was much darker and apparently matted with blood,” consistent with a blow to the head. Many believed that Henry had been murdered at the hands of the king’s brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, but though Richard may have been present, the order undoubtedly came from Edward IV.

Henry VI , c1450. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The slaughter also extended to Edward’s own family. The relationship Edward shared with his younger brother George, Duke of Clarence, was tumultuous, to say the least. After several estrangements and reconciliations, in 1477 Clarence finally went too far. Convinced that his brother was conspiring against him, Edward had Clarence arrested; at the beginning of February 1478, he was tried and condemned to death. On 18 February Clarence was executed within the confines of the Tower of London. According to several contemporary sources, at his own request the duke was drowned after being “plunged into a jar of sweet wine” in the Bowyer Tower. Clarence’s daughter, Margaret Pole, was later painted wearing a bracelet with a barrel charm, which appears to support this story. The duke’s death orphaned both Margaret and her younger brother Edward, Earl of Warwick. Like their father, both would meet violent ends.

The princes in the TowerEdward IV died unexpectedly on 9 April 1483, leaving as successor his 12-year-old son, also Edward, at that time staying at Ludlow Castle. After his father’s death, the young Prince Edward set out for London but was intercepted en route by his uncle Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who lodged Edward and his brother Prince Richard in the Tower of London. Having been declared illegitimate, on 26 June Edward was deposed in favour of his uncle, who took the throne as Richard III.

Rumours about the fate of the ‘princes in the Tower’ soon began to circulate. Many believe that they were murdered “lying in their beds” on the orders of Richard III, and the skeletons of two youths discovered in the Tower in 1674 seems to support this theory. Some, however, insist that the boys did not die in the Tower but managed to escape. Though their ultimate fate is still obscure, one thing is certain: after the coronation of Richard III on 6 July, neither boy was seen alive again.

‘The Young Princes in the Tower', 1831. After a painting by Hippolyte De La Roche (1797–1856), commonly known as Paul Delaroche. From the Connoisseur VOL XXVII, 1910. (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Richard III did not hold his throne for long. In 1485 his army was confronted by the forces of the Lancastrian Henry Tudor at Bosworth in Leicestershire. Richard fought bravely in his attempt to defend his crown, but was “pierced with many mortal wounds”, and became the last king of England to be killed on the battlefield. Thanks to the discovery of his skeleton in Leicester, we now know that a blow to the head killed Richard, and that his body was subjected to a number of “humiliation” wounds after his death.

Richard’s successor, Henry VII, ordered the execution of the Duke of Clarence’s son, the Earl of Warwick, beheaded In 1499 for conspiring with the pretender Perkin Warbeck to overthrow the king. Warwick’s sister, Margaret Pole, was executed in 1541 by command of Henry VIII on charges of treason. In her late sixties and condemned on evidence that was almost certainly falsified, Margaret’s death shocked her contemporaries, one of whom observed that her execution was conducted by “a wretched and blundering youth” who “literally hacked her head and shoulders to pieces in the most pitiful manner” so that she bled to death.

Henry VIII’s wivesHenry VIII also notoriously executed two of his wives. Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard were both condemned on charges of adultery, treason, and, in Anne’s case, incest with her own brother. Anne was almost certainly innocent of the crimes of which she was accused; nevertheless, on the morning of 19 May 1536 she became the first queen of England to be executed. Although her death within the confines of the Tower of London was intended to be a private affair, conducted away from the eyes of curious Londoners, around 1,000 people watched as her head was struck from her body with one strike of a French executioner’s sword.

In 1554 Lady Jane Grey also met her fate at the headsman’s axe. So, too, did Mary, Queen of Scots, executed in February 1587 on the orders of Elizabeth I. The first queen regnant to be beheaded, Mary was decapitated at Fotheringhay Castle in a bloody scene: it took three strokes of the axe to remove her head.

The execution of Mary, Queen of Scots at Fotheringhay Castle, 1587. From ‘The Island Race’, a book written by Sir Winston Churchill and published in 1964 that covers the history of the British Isles from pre-Roman times to the Victorian era. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

Mary’s grandson was to suffer a similar ignominious end the following century. Having been defeated in the Civil War, in January 1649 Charles I became the first English monarch to be tried and condemned for treason – there was no precedent for the lawful killing of a king. On the date of his execution, 30 January, Charles stepped out of Banqueting House in Whitehall on to a public scaffold. His head was removed amid a great groan from the crowd, and it was observed that many of those who attended dipped their handkerchiefs in the late king’s blood as a memento.

Charles’s death signalled the abolition of the monarchy, and the establishment of a republic in England. In a public display of contempt for the monarchy, he became the only king of England to be murdered by his subjects. It was a far cry from the dark and mysterious circumstances surrounding the death of William ‘Rufus’ and those other ill-fated royals who came before.

Nicola Tallis is a British historian and author. Her new book Crown of Blood: The Deadly Inheritance of Lady Jane Grey is published by Michael O’Mara Books on 3 November 2016.

The execution of Charles I, 30 January 1649. Charles’s death signalled the abolition of the monarchy, and the establishment of a republic in England. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The execution of Charles I, 30 January 1649. Charles’s death signalled the abolition of the monarchy, and the establishment of a republic in England. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Royal status brings with it privilege and power – but also danger, particularly the risk of assassination by those craving that power. From the Norman conquest to Charles’s execution in 1649, many British men, women and children of royal blood died in extraordinary circumstances. Deaths early in that period were often shrouded in mystery, but by the 17th century circumstances had changed to an extraordinary extent – for the first time an executioner severed the head of a king of England: Charles I, condemned by his own people…

William II meets his fate in the forestOn 2 August 1100 King William II, third son of William the Conqueror, was hunting in the New Forest. The chronicler William of Malmesbury reported that after dinner the king, nicknamed ‘Rufus’, went into the forest “attended by few persons”, notably a gentleman named Walter Tirel. While most of the king’s party “employed in the chase, were dispersed as chance directed,” Tirel remained with the king. As the sun began to set, William spotted a stag and “drawing his bow and letting fly an arrow, slightly wounded” it.

In his excitement the king began to run towards the injured target, and at that point Tirel, “conceiving a noble exploit” in that the king’s attention was occupied elsewhere, “pierced his breast with a fatal arrow”. William fell to the ground and Tirel, seeing that the king was dead, immediately “leaped swiftly upon his horse, and escaped by spurring him to his utmost speed”.

Upon discovering William’s body, the rest of his party fled and, in an attempt to protect their own interests, readied themselves to declare their allegiance to the next king. It was left to a few countrymen to convey the dead king’s corpse to Winchester Cathedral by cart, “the blood dripping from it all the way”.

Was William’s death an accident, or was it murder? An accident was possible, but there were many who believed otherwise. William’s younger brother immediately assumed the throne and swiftly had himself crowned Henry I. Henry had much to gain from his brother’s death, and Tirel may have been in his employ. William had, however, been an unpopular king, and his death was “lamented by few”.

King William II of England, aka William Rufus, c1100. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The Lionheart and eyeless ArtAlmost 100 years later, Henry I’s great-grandson, Richard I, also met a violent end at the point of an arrow, but in very different circumstances. Richard had spent the majority of his 10-year reign fighting abroad on crusade; he was a brave solider who inspired loyalty in his men. In 1199, while he was besieging the Château de Châlus-Chabrol, a crossbow bolt struck him in the shoulder. Though the shot did not kill him, it penetrated deep into his body. Though removal of the bolt by a surgeon was a painful ordeal, Richard survived – but before long the wound became infected and gangrene set in. It became clear that the king’s days were numbered, and on 6 April, 11 days after he was shot, “the man devoted to martial deeds, breathed his last.”

Richard was succeeded by his younger brother, John. However, though John was accepted as king of England he had a rival for his French lands: Arthur of Brittany, son of John’s brother, Geoffrey, who had died over a decade earlier. In 1202, John’s forces captured Arthur at Mirebeau, where the latter had been attempting to besiege the castle in which his grandmother (John’s mother), Eleanor of Aquitaine, was sheltering. Arthur was taken to Falaise, where – it was later claimed – John gave orders for his 16-year-old nephew to be “deprived of his eyes and genitals”, but the jailer refused to obey such a cruel command. Shortly afterwards, the boy was moved to Rouen where, on the evening of 3 April 1203, it seems that John himself, “drunk with wine and possessed of the Devil”, killed Arthur personally. The young boy’s lifeless body was reputedly weighed down with a heavy stone and thrown into the river Seine.

In the two centuries after the murder of Arthur of Brittany, both Edward II and Richard II were deposed. The latter was almost certainly starved to death in Pontefract Castle, but controversy still surrounds the end of Edward II – he may have been murdered in Berkeley Castle, but several modern historians are of the opinion that he escaped abroad.

Richard I, aka ‘Richard the Lionheart’, depicted plunging his fist into a lion's throat, c1180. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The bloody Wars of the RosesIn the middle of the 15th century, the Wars of the Roses broke out, causing a profusion of bloodshed that did not exclude royal or noble families. After a struggle that saw the Lancastrian King Henry VI deposed in favour of the Yorkist Edward IV, and a brief period of restoration for Henry VI (commonly referred to as the readeption), on 4 May 1471 the armies of Lancaster and York met at Tewkesbury, where Edward IV won “a famous victory”. It was a fierce battle during which around 2,000 Lancastrians were slain, and the battlefield is still referred to as ‘Bloody Meadow.’

For Henry’s son and heir, the 18-year-old Prince Edward of Lancaster, Tewkesbury had been his first experience of war, and one that he would not survive. Reports of the precise manner of the prince’s death vary: most sources state that the he was killed in the field, whereas the Yorkist author of the Arrivall of Edward IV, who claimed to be a servant of Edward IV’s and a witness to many of the events about which he wrote, asserts that Edward “was taken fleeing to the townwards, and slain in the field”. Later Tudor historians, however, implied that the prince had been murdered “by the avenging hands of certain persons,” on the orders of Edward IV. Whatever the circumstances, the Lancastrian heir had been removed; now all that remained was for his father to be eliminated.

While the battle of Tewkesbury raged, Henry VI was a prisoner in the Tower of London. Following his victory, Edward IV travelled to London in triumph, arriving on 21 May. That same evening, Henry VI was reportedly praying in his oratory within the Wakefield Tower when he “was put to death”. Though the author of the Arrivall stated that Henry died of “pure displeasure and melancholy” as a result of being told of the death of his son, there is little doubt that he died violently. The examination of his skull in 1911 revealed that to one piece “there was still attached some of the hair, which was brown in colour, save in one place, where it was much darker and apparently matted with blood,” consistent with a blow to the head. Many believed that Henry had been murdered at the hands of the king’s brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, but though Richard may have been present, the order undoubtedly came from Edward IV.

Henry VI , c1450. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The slaughter also extended to Edward’s own family. The relationship Edward shared with his younger brother George, Duke of Clarence, was tumultuous, to say the least. After several estrangements and reconciliations, in 1477 Clarence finally went too far. Convinced that his brother was conspiring against him, Edward had Clarence arrested; at the beginning of February 1478, he was tried and condemned to death. On 18 February Clarence was executed within the confines of the Tower of London. According to several contemporary sources, at his own request the duke was drowned after being “plunged into a jar of sweet wine” in the Bowyer Tower. Clarence’s daughter, Margaret Pole, was later painted wearing a bracelet with a barrel charm, which appears to support this story. The duke’s death orphaned both Margaret and her younger brother Edward, Earl of Warwick. Like their father, both would meet violent ends.

The princes in the TowerEdward IV died unexpectedly on 9 April 1483, leaving as successor his 12-year-old son, also Edward, at that time staying at Ludlow Castle. After his father’s death, the young Prince Edward set out for London but was intercepted en route by his uncle Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who lodged Edward and his brother Prince Richard in the Tower of London. Having been declared illegitimate, on 26 June Edward was deposed in favour of his uncle, who took the throne as Richard III.

Rumours about the fate of the ‘princes in the Tower’ soon began to circulate. Many believe that they were murdered “lying in their beds” on the orders of Richard III, and the skeletons of two youths discovered in the Tower in 1674 seems to support this theory. Some, however, insist that the boys did not die in the Tower but managed to escape. Though their ultimate fate is still obscure, one thing is certain: after the coronation of Richard III on 6 July, neither boy was seen alive again.

‘The Young Princes in the Tower', 1831. After a painting by Hippolyte De La Roche (1797–1856), commonly known as Paul Delaroche. From the Connoisseur VOL XXVII, 1910. (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Richard III did not hold his throne for long. In 1485 his army was confronted by the forces of the Lancastrian Henry Tudor at Bosworth in Leicestershire. Richard fought bravely in his attempt to defend his crown, but was “pierced with many mortal wounds”, and became the last king of England to be killed on the battlefield. Thanks to the discovery of his skeleton in Leicester, we now know that a blow to the head killed Richard, and that his body was subjected to a number of “humiliation” wounds after his death.

Richard’s successor, Henry VII, ordered the execution of the Duke of Clarence’s son, the Earl of Warwick, beheaded In 1499 for conspiring with the pretender Perkin Warbeck to overthrow the king. Warwick’s sister, Margaret Pole, was executed in 1541 by command of Henry VIII on charges of treason. In her late sixties and condemned on evidence that was almost certainly falsified, Margaret’s death shocked her contemporaries, one of whom observed that her execution was conducted by “a wretched and blundering youth” who “literally hacked her head and shoulders to pieces in the most pitiful manner” so that she bled to death.

Henry VIII’s wivesHenry VIII also notoriously executed two of his wives. Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard were both condemned on charges of adultery, treason, and, in Anne’s case, incest with her own brother. Anne was almost certainly innocent of the crimes of which she was accused; nevertheless, on the morning of 19 May 1536 she became the first queen of England to be executed. Although her death within the confines of the Tower of London was intended to be a private affair, conducted away from the eyes of curious Londoners, around 1,000 people watched as her head was struck from her body with one strike of a French executioner’s sword.

In 1554 Lady Jane Grey also met her fate at the headsman’s axe. So, too, did Mary, Queen of Scots, executed in February 1587 on the orders of Elizabeth I. The first queen regnant to be beheaded, Mary was decapitated at Fotheringhay Castle in a bloody scene: it took three strokes of the axe to remove her head.

The execution of Mary, Queen of Scots at Fotheringhay Castle, 1587. From ‘The Island Race’, a book written by Sir Winston Churchill and published in 1964 that covers the history of the British Isles from pre-Roman times to the Victorian era. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

Mary’s grandson was to suffer a similar ignominious end the following century. Having been defeated in the Civil War, in January 1649 Charles I became the first English monarch to be tried and condemned for treason – there was no precedent for the lawful killing of a king. On the date of his execution, 30 January, Charles stepped out of Banqueting House in Whitehall on to a public scaffold. His head was removed amid a great groan from the crowd, and it was observed that many of those who attended dipped their handkerchiefs in the late king’s blood as a memento.

Charles’s death signalled the abolition of the monarchy, and the establishment of a republic in England. In a public display of contempt for the monarchy, he became the only king of England to be murdered by his subjects. It was a far cry from the dark and mysterious circumstances surrounding the death of William ‘Rufus’ and those other ill-fated royals who came before.

Nicola Tallis is a British historian and author. Her new book Crown of Blood: The Deadly Inheritance of Lady Jane Grey is published by Michael O’Mara Books on 3 November 2016.

Published on September 08, 2016 03:00

September 7, 2016

10 things you (probably) didn’t know about the Great Fire of London

History Extra

Great Fire of London, September 1666. (Photo by Time Life Pictures/Mansell/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

Great Fire of London, September 1666. (Photo by Time Life Pictures/Mansell/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

On 5 September 1666, the 33-year-old Samuel Pepys climbed the steeple of the ancient church of All Hallows-by-the-Tower and was met with the “the saddest sight of desolation that I ever saw; everywhere great fires, oyle-cellars, and brimstone, and other things burning”. Leaving the church, he wandered along Gracechurch Street, Fenchurch Street and Lombard Street towards the Royal Exchange, which he found to be “a sad sight” with all the pillars and statues (except one of Sir Thomas Gresham) destroyed. The ground scorched his feet and he found nothing but dust, ash and ruins. It was the fourth day of the Great Fire of London and, though some parts of the city would continue to burn for months, the worst of the destruction was finally over.

Thanks in part to Pepys’s vivid diary entries, the story of the Great Fire is well known. Alongside the fortunes of Henry VIII’s wives, the Battle of Britain and the fate of Guy Fawkes, it forms part of a scattering of familiar islands in the muddy quagmire of British history. We all know, roughly speaking, what happened: during the early hours of 2 September 1666, a fire broke out in Thomas Farriner’s bakehouse on Pudding Lane, which blazed and spread with such ferocity and speed that within a few days the old City of London was reduced to a charred ruin. More than 13,000 houses, 87 churches and 44 livery halls were destroyed, the historic city gates were wrecked, and the Guildhall, St Paul’s Cathedral, Baynard’s Castle and the Royal Exchange were severely damaged – in some cases, beyond repair.

Those with more than a passing knowledge of the crucial facts might be aware of accounts of King Charles II fighting the fire alongside his brother, the Duke of York; of Samuel Pepys taking pains to bury his prized parmesan cheese; or of the French watchmaker Robert Hubert meeting his death at Tyburn after (falsely) claiming to have started the blaze. Here are 10 more facts you may not know about the Great Fire of London…

1) It did not start on Pudding LaneThomas Farriner’s bakehouse was not located on Pudding Lane proper. Hearth Tax records created just before the fire place Farriner’s bakehouse on Fish Yard, a small enclave off Pudding Lane. His immediate neighbours included a waterbearer named Henry More, a sexton [a person who looks after a church and churchyard] named Thomas Birt, the parish ‘clearke’, a plasterer named George Porter, one Alice Spencer, a widow named Mrs Mary Whittacre, and a turner named John Bibie.

Billingsgate, London, pictured in 1598. Until boundary changes in 2003, the ward included Pudding Lane. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

Billingsgate, London, pictured in 1598. Until boundary changes in 2003, the ward included Pudding Lane. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

2) The Great Fire of London was not Thomas Farriner’s first brush with troubleIn 1627, the then 10- or 11-year-old Thomas Farriner was discovered by a city constable wandering alone within the city walls, having run away from his master [it is not known why he had a master at this time]. He was detained at Bridewell Prison, where the incident was recorded in the book of minutes.

During the 17th century, Bridewell (a former Tudor palace) was a kind of proto-correctional facility where young waifs and strays would often be sent to receive a rudimentary education, many of them then cherry-picked to become apprentices to the prison’s patrons.

During the boy’s hearing, it transpired that he had attempted to run away from his master three or four times previously. Farriner was released, only to be detained once more in 1628 for the same reason. A year later he was apprenticed as a baker under one Thomas Dodson.

3) Far from levelling the city, the Great Fire of London scorched the skin and flesh from the city’s buildings – but their skeletons remainedThe ruins of many of London’s buildings had to be demolished before rebuilding work could begin. A sketch from 1673 by Thomas Wyck shows the extent of the ruins of St Paul’s Cathedral that remained. John Evelyn described the remaining stones as standing upright, fragile and “calcined”.

What’s more, the burning lasted months, not days: Pepys recorded that cellars were still burning in March of the following year. With plenty of nooks and crannies to commandeer, gangs operated among the ruins, pretending to offer travellers a ‘link’ (escorted passage) – only to rob them blind and leave them for dead. Many of those who lost their homes and livelihood to the fire built temporary shacks on the ruins of their former homes and shops until this was prohibited.

Old St Paul's Cathedral burning in the Great Fire of London, 1666. By Wenceslaus Hollar. (Photo by Guildhall Library & Art Gallery/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

Old St Paul's Cathedral burning in the Great Fire of London, 1666. By Wenceslaus Hollar. (Photo by Guildhall Library & Art Gallery/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

4) At the time of the Great Fire, England was engaged in a costly war with the Dutch Republic and was gearing up for one last battleThe conflict, known as the Second Anglo-Dutch War, was the second of three 17th-century maritime wars to be fought between the English and the Dutch over transatlantic trade supremacy. By September 1666 there had already been five major engagements: the battle of Lowestoft (1665); the battle of Vågen (1665); the Four Days’ Battle (1666); St James’s Day Battle (1666); and Holmes’s Bonfire (1666).

In the confusion of the blaze, some believed that the Great Fire of London had been started by Dutch merchants in retaliation for the last of these engagements – a vicious raid on the Dutch islands of Vlieland and Terschelling – which had occurred barely a month earlier. That attack had been orchestrated by Sir Robert Holmes (renowned for his short fuse and unpredictable nature) and resulted in the destruction of an estimated 150 Dutch merchant ships and, crucially, the torching of the town of West-Terschelling.

While the attack was celebrated with bonfires and bells in London, it appalled the Dutch, and there was rioting in Amsterdam. Aphra Behn – at that time an English spy stationed in Antwerp – wrote how she had seen a letter from a merchant’s wife “that desires her husband to com [sic] to Amsterdam home for that theare [sic] never was so great a desolation & mourning”. Behn was supposed to travel to Dort to continue her espionage, but declared that she “dare as well be hang’d as go”.

5) Though we do not know exactly how many people died as a result of the Great Fire of London, it was almost certainly more than commonly accepted figuresIn the traditional telling of the Great Fire story, the human cost is negligible. Indeed, only a few years after the blaze, Edward Chamberlayne claimed that “not above six or eight persons were burnt,” and an Essex vicar named Ralph Josselin noted that “few perished in the flames.” There was undoubtedly enough warning to ensure that a large proportion of London’s population vacated hazardous areas, but for every sick person helped out of their house, there must have been others with no one to aid them. What’s more, parish records hint at a far greater death toll than previously supposed.