MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 88

July 26, 2016

Stonehenge and Nearby Stone Circles Were Newcomers to Landscape worked by Ice Age hunters

Ancient Origins

About 5,000 years ago, not far from Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain in England, some people built a stone circle smaller than its more famous counterpart. But for some reason, sometime after they built it, they dismantled the circle of bluestones and removed them.

Stonehenge and “Bluestonehenge,” as researchers have dubbed it, and other manmade features within a mile or two of the famous site were newcomers among some very ancient human-worked features in the landscape, a group of researchers says.

The archaeologists published an article this month about Bluestonehenge in the journal Antiquity (closed access) that says it and Stonehenge, a third stone circle several hundred meters away known as Amesbury henge and another at Durrington Walls came much later than when Stone Age hunter-gatherers began building features in wood in the area.

A digital reconstruction of Bluestonehenge by Henry Rothwell (

Wikimedia Commons

)About 9,000 years ago, some people built wooden features that may have been ceremonial or ritual in nature—possibly aligned to solstice sunsets. Chemical traces of the pinewood are still detectable in the postholes in the soil near Stonehenge.

A digital reconstruction of Bluestonehenge by Henry Rothwell (

Wikimedia Commons

)About 9,000 years ago, some people built wooden features that may have been ceremonial or ritual in nature—possibly aligned to solstice sunsets. Chemical traces of the pinewood are still detectable in the postholes in the soil near Stonehenge.

Prehistoric people built Bluestonehenge out of bluestones that came from far away and later removed those stones to Stonehenge, the researchers think. The smaller Bluestonehenge monument was connected to its more famous counterpart by a feature called the Avenue—a broad road leading from Stonehenge to the River Avon about 500 meters (1640.4 feet) away.

“Stonehenge has long been known to form part of a larger prehistoric landscape,” write archaeologist Michael J. Allen and his colleagues. “In particular, it is part of a composite monument that includes the Stonehenge Avenue and the newly discovered West Amesbury henge, which is situated at the eastern end of the Avenue beside the River Avon. Inside that henge lies an earlier circle of stoneholes, formerly holding small standing stones; this is known as ‘Bluestonehenge’.”

Features of the immediate landscape of Stonehenge include three stone circles, at Stonehenge itself, at the Neolithic village of Durrington Walls, which are still standing, and another that was taken down—Bluestonehenge. (Drawn by Joshua Pollard for Antiquity)The researchers said the Avenue has been known for centuries, but in 2008 and 2009 the Stonehenge Riverside Project did more explorations and dug new trenches and ascertained that the road reached the River Avon.

Features of the immediate landscape of Stonehenge include three stone circles, at Stonehenge itself, at the Neolithic village of Durrington Walls, which are still standing, and another that was taken down—Bluestonehenge. (Drawn by Joshua Pollard for Antiquity)The researchers said the Avenue has been known for centuries, but in 2008 and 2009 the Stonehenge Riverside Project did more explorations and dug new trenches and ascertained that the road reached the River Avon.

“The aim was to establish whether the Avenue was built in more than one phase, and whether it actually reached the river, thereby addressing the theory that Stonehenge was part of a larger complex linked by the river to Durrington Walls henge and its newly discovered avenue, two miles upstream,” they wrote.

All along from 1719 AD through to the present day, researchers have been analyzing the Avenue and digging in it to determine its parameters and purposes. Scholars have proposed theories about the prehistoric banks, ruts, ditches and ridges and stripes in the soil of the Avenue. There has been speculation that the ancient people dug the ditches of the Avenue and built other monuments in the area to align with the winter and summer solstice sunsets.

The Avenue, a road leading from Stonehenge to Bluestonehenge at the River Avon, was part of a larger network of monuments in the area, including stone circles at West Amesbury and Durrington Walls. (Photograph by Adam Stanford in Antiquity)Stonehenge is near three Early Mesolithic postholes that held pine posts 1 meter (3.1 feet) in diameter. These postholes are 250 meters (820.2 feet) west of the Avenue and hint “at the possibility that this unusual solstitial alignment, formed by the ridges and stripes, was recognised long before the Neolithic. These vertical pine posts or tree-trunks were erected, probably one after the other, in the centuries around 7000 BC by hunter-gatherers, three millennia before the beginning of agriculture in Britain. Monuments built by hunter-gatherers are generally rare; although large pits are known from this period, the Stonehenge postholes are unparalleled anywhere for the Early Mesolithic of Northern Europe.”

The Avenue, a road leading from Stonehenge to Bluestonehenge at the River Avon, was part of a larger network of monuments in the area, including stone circles at West Amesbury and Durrington Walls. (Photograph by Adam Stanford in Antiquity)Stonehenge is near three Early Mesolithic postholes that held pine posts 1 meter (3.1 feet) in diameter. These postholes are 250 meters (820.2 feet) west of the Avenue and hint “at the possibility that this unusual solstitial alignment, formed by the ridges and stripes, was recognised long before the Neolithic. These vertical pine posts or tree-trunks were erected, probably one after the other, in the centuries around 7000 BC by hunter-gatherers, three millennia before the beginning of agriculture in Britain. Monuments built by hunter-gatherers are generally rare; although large pits are known from this period, the Stonehenge postholes are unparalleled anywhere for the Early Mesolithic of Northern Europe.”

Also, along the River Avon researchers have found activity from the 8th millennium BC through the 5th millennium BC, “making it, potentially, an unusually ‘persistent place’ within the early Holocene,” the authors wrote. The Holocene was the most recent Ice Age that began around 10,000 years ago.

Stonehenge is situated among a number of nearby prehistoric monuments, including the newly discovered Bluestonehenge, a smaller circle that was 500 meters away at the end of a road leading to the River Avon. (

Wikimedia Commons photo

/Michael Osmenda)As for the bluestones of Bluestonehenge, which are missing, the researchers speculate they were taken to Stonehenge. They say they are uncertain of the date of construction of Bluestonehenge, but it occurred about the same time the people were digging the ditches of the Avenue, building West Amesbury henge and rearranging some other bluestones at Stonehenge.

Stonehenge is situated among a number of nearby prehistoric monuments, including the newly discovered Bluestonehenge, a smaller circle that was 500 meters away at the end of a road leading to the River Avon. (

Wikimedia Commons photo

/Michael Osmenda)As for the bluestones of Bluestonehenge, which are missing, the researchers speculate they were taken to Stonehenge. They say they are uncertain of the date of construction of Bluestonehenge, but it occurred about the same time the people were digging the ditches of the Avenue, building West Amesbury henge and rearranging some other bluestones at Stonehenge.

These works were possibly carried out by people of the Beakers culture, the authors wrote.

“The arrival of Beakers and accompanying continental European styles of mortuary practice and material culture signalled a major social and cultural transition in Britain, including the decline of large-scale labour mobilisation for megalith-building,” their paper states.

One of the authors, archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson, has speculated that stone henges were meant for the dead, and wood henges found in the vicinity were features meant for living people.

Top image: Stonehenge England ( public domain )

By Mark Miller

About 5,000 years ago, not far from Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain in England, some people built a stone circle smaller than its more famous counterpart. But for some reason, sometime after they built it, they dismantled the circle of bluestones and removed them.

Stonehenge and “Bluestonehenge,” as researchers have dubbed it, and other manmade features within a mile or two of the famous site were newcomers among some very ancient human-worked features in the landscape, a group of researchers says.

The archaeologists published an article this month about Bluestonehenge in the journal Antiquity (closed access) that says it and Stonehenge, a third stone circle several hundred meters away known as Amesbury henge and another at Durrington Walls came much later than when Stone Age hunter-gatherers began building features in wood in the area.

A digital reconstruction of Bluestonehenge by Henry Rothwell (

Wikimedia Commons

)About 9,000 years ago, some people built wooden features that may have been ceremonial or ritual in nature—possibly aligned to solstice sunsets. Chemical traces of the pinewood are still detectable in the postholes in the soil near Stonehenge.

A digital reconstruction of Bluestonehenge by Henry Rothwell (

Wikimedia Commons

)About 9,000 years ago, some people built wooden features that may have been ceremonial or ritual in nature—possibly aligned to solstice sunsets. Chemical traces of the pinewood are still detectable in the postholes in the soil near Stonehenge.Prehistoric people built Bluestonehenge out of bluestones that came from far away and later removed those stones to Stonehenge, the researchers think. The smaller Bluestonehenge monument was connected to its more famous counterpart by a feature called the Avenue—a broad road leading from Stonehenge to the River Avon about 500 meters (1640.4 feet) away.

“Stonehenge has long been known to form part of a larger prehistoric landscape,” write archaeologist Michael J. Allen and his colleagues. “In particular, it is part of a composite monument that includes the Stonehenge Avenue and the newly discovered West Amesbury henge, which is situated at the eastern end of the Avenue beside the River Avon. Inside that henge lies an earlier circle of stoneholes, formerly holding small standing stones; this is known as ‘Bluestonehenge’.”

Features of the immediate landscape of Stonehenge include three stone circles, at Stonehenge itself, at the Neolithic village of Durrington Walls, which are still standing, and another that was taken down—Bluestonehenge. (Drawn by Joshua Pollard for Antiquity)The researchers said the Avenue has been known for centuries, but in 2008 and 2009 the Stonehenge Riverside Project did more explorations and dug new trenches and ascertained that the road reached the River Avon.

Features of the immediate landscape of Stonehenge include three stone circles, at Stonehenge itself, at the Neolithic village of Durrington Walls, which are still standing, and another that was taken down—Bluestonehenge. (Drawn by Joshua Pollard for Antiquity)The researchers said the Avenue has been known for centuries, but in 2008 and 2009 the Stonehenge Riverside Project did more explorations and dug new trenches and ascertained that the road reached the River Avon.“The aim was to establish whether the Avenue was built in more than one phase, and whether it actually reached the river, thereby addressing the theory that Stonehenge was part of a larger complex linked by the river to Durrington Walls henge and its newly discovered avenue, two miles upstream,” they wrote.

All along from 1719 AD through to the present day, researchers have been analyzing the Avenue and digging in it to determine its parameters and purposes. Scholars have proposed theories about the prehistoric banks, ruts, ditches and ridges and stripes in the soil of the Avenue. There has been speculation that the ancient people dug the ditches of the Avenue and built other monuments in the area to align with the winter and summer solstice sunsets.

The Avenue, a road leading from Stonehenge to Bluestonehenge at the River Avon, was part of a larger network of monuments in the area, including stone circles at West Amesbury and Durrington Walls. (Photograph by Adam Stanford in Antiquity)Stonehenge is near three Early Mesolithic postholes that held pine posts 1 meter (3.1 feet) in diameter. These postholes are 250 meters (820.2 feet) west of the Avenue and hint “at the possibility that this unusual solstitial alignment, formed by the ridges and stripes, was recognised long before the Neolithic. These vertical pine posts or tree-trunks were erected, probably one after the other, in the centuries around 7000 BC by hunter-gatherers, three millennia before the beginning of agriculture in Britain. Monuments built by hunter-gatherers are generally rare; although large pits are known from this period, the Stonehenge postholes are unparalleled anywhere for the Early Mesolithic of Northern Europe.”

The Avenue, a road leading from Stonehenge to Bluestonehenge at the River Avon, was part of a larger network of monuments in the area, including stone circles at West Amesbury and Durrington Walls. (Photograph by Adam Stanford in Antiquity)Stonehenge is near three Early Mesolithic postholes that held pine posts 1 meter (3.1 feet) in diameter. These postholes are 250 meters (820.2 feet) west of the Avenue and hint “at the possibility that this unusual solstitial alignment, formed by the ridges and stripes, was recognised long before the Neolithic. These vertical pine posts or tree-trunks were erected, probably one after the other, in the centuries around 7000 BC by hunter-gatherers, three millennia before the beginning of agriculture in Britain. Monuments built by hunter-gatherers are generally rare; although large pits are known from this period, the Stonehenge postholes are unparalleled anywhere for the Early Mesolithic of Northern Europe.”Also, along the River Avon researchers have found activity from the 8th millennium BC through the 5th millennium BC, “making it, potentially, an unusually ‘persistent place’ within the early Holocene,” the authors wrote. The Holocene was the most recent Ice Age that began around 10,000 years ago.

Stonehenge is situated among a number of nearby prehistoric monuments, including the newly discovered Bluestonehenge, a smaller circle that was 500 meters away at the end of a road leading to the River Avon. (

Wikimedia Commons photo

/Michael Osmenda)As for the bluestones of Bluestonehenge, which are missing, the researchers speculate they were taken to Stonehenge. They say they are uncertain of the date of construction of Bluestonehenge, but it occurred about the same time the people were digging the ditches of the Avenue, building West Amesbury henge and rearranging some other bluestones at Stonehenge.

Stonehenge is situated among a number of nearby prehistoric monuments, including the newly discovered Bluestonehenge, a smaller circle that was 500 meters away at the end of a road leading to the River Avon. (

Wikimedia Commons photo

/Michael Osmenda)As for the bluestones of Bluestonehenge, which are missing, the researchers speculate they were taken to Stonehenge. They say they are uncertain of the date of construction of Bluestonehenge, but it occurred about the same time the people were digging the ditches of the Avenue, building West Amesbury henge and rearranging some other bluestones at Stonehenge.These works were possibly carried out by people of the Beakers culture, the authors wrote.

“The arrival of Beakers and accompanying continental European styles of mortuary practice and material culture signalled a major social and cultural transition in Britain, including the decline of large-scale labour mobilisation for megalith-building,” their paper states.

One of the authors, archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson, has speculated that stone henges were meant for the dead, and wood henges found in the vicinity were features meant for living people.

Top image: Stonehenge England ( public domain )

By Mark Miller

Published on July 26, 2016 03:00

July 25, 2016

Ancient Egyptian Logbook of Inspector Who Helped Construct the Great Pyramid Revealed

Ancient Origins

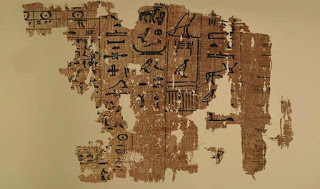

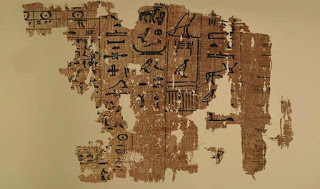

Some of the details of the construction of the Egyptian Great Pyramid are revealed to the public for the first time when they go on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The information comes in the form of a papyri logbook written by an inspector named Merer. While much about the building of the pyramids remains unknown and speculative, the precious text sheds at least some light on the later aspects of the building process.

According to Live Science, Merer wrote in hieroglyphics how he was in charge of about 200 men and gave some information about the construction process while he was working on it in the 27th year of Khufu's reign.

Statue of Khufu in the Cairo Museum. (

Public Domain

)Writing on the document in 2014 (it was unearthed in 2013), the archaeologists Pierre Tallet and Gregory Marouard said that the pyramid was nearing completion when the text was written. Merer wrote that the work at that time was focused on creating the limestone casing to cover the pyramid.

Statue of Khufu in the Cairo Museum. (

Public Domain

)Writing on the document in 2014 (it was unearthed in 2013), the archaeologists Pierre Tallet and Gregory Marouard said that the pyramid was nearing completion when the text was written. Merer wrote that the work at that time was focused on creating the limestone casing to cover the pyramid.

4,600-year-old step pyramid uncovered in Egypt and its purpose is a mysteryDiscovery of 5,000-year-old Hieroglyphs Change the Story of a Queen, a Pharaoh, and an Ancient CityThe archaeologists’ research on the logbook was published as an article in the journal Near Eastern Archaeology. They explained in their article that the document is comprised of more than 300 fragments of varying sizes and provides details on the inspector’s daily activities over several months.

Concentration of papyri in the rubble on which the logbook was written. (

P. Tallet

)The logbook was discovered at the Red Sea harbor of Wadi al-Jarf and Live Science reports that “It dates back about 4,500 years, making it the oldest papyrus document ever discovered in Egypt.”

Concentration of papyri in the rubble on which the logbook was written. (

P. Tallet

)The logbook was discovered at the Red Sea harbor of Wadi al-Jarf and Live Science reports that “It dates back about 4,500 years, making it the oldest papyrus document ever discovered in Egypt.”

Apart from the information on daily activities, Merer’s log (and others found at the site) also provide additional interesting tidbits of data. The archaeologists wrote in their articles that:

Sarcophagus of Egyptian High Priest Unearthed with Hieroglyphic Inscriptions and Scenes of Offerings Analysis Begins on Cosmic Particles in the Egyptian Bent Pyramid – Will This Help Explain How the Pyramids Were Built? The Great Pyramid, also known as the Pyramid of Cheops and Pyramid of Khufu, is comprised of more than 2 million limestone blocks weighing from 2 to 70 tons. Thus, it is interesting to note that Merer’s logbook explains from where this material was quarried and how it was transported towards the pyramid’s site. Tallet and Marouard’s article says that the logbook:

Left: Part of a papyrus inscribed with an account dating to the reign of Khufu (13th cattle count). (

G. Pollin

) Right: Account on a papyrus (A) and a detail of one page of inspector Merer's “diary” (B), mentioning the “Horizon of Khufu.” (

G. Pollin

)The Great Pyramid is the only Giza pyramid that has air shafts . This pyramid was built with such precision that it has been said that it would be difficult to replicate it even with today’s technology. This point is one of the reasons why so many people are fascinated by the pyramid’s construction.

Left: Part of a papyrus inscribed with an account dating to the reign of Khufu (13th cattle count). (

G. Pollin

) Right: Account on a papyrus (A) and a detail of one page of inspector Merer's “diary” (B), mentioning the “Horizon of Khufu.” (

G. Pollin

)The Great Pyramid is the only Giza pyramid that has air shafts . This pyramid was built with such precision that it has been said that it would be difficult to replicate it even with today’s technology. This point is one of the reasons why so many people are fascinated by the pyramid’s construction.

Within the Great Pyramid, there are areas that are called the King's Chamber, the Queen's Chamber, and the Subterranean Chamber. It should be noted however that there is much debate over these names and the purpose of the pyramid itself. Mainstream archaeology accepts that the pyramid was built around 2500 BC and commissioned by King Khufu for his tomb. However, much controversy surrounds these conclusions. For example, German archaeologists in 2013, argued that the Great Pyramid is much older and served a different purpose .

The debate over the pyramid’s construction and use continues to enthrall many researchers and, although work continues at the site, many of the questions behind this fascinating ancient structure remain unanswered.

The Great Pyramid of Giza. Source: BigStockPhoto Top Image: One of the papyri in the ancient logbook which documented some details on the later construction period of the Great Pyramid of Giza. Source:

Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities

The Great Pyramid of Giza. Source: BigStockPhoto Top Image: One of the papyri in the ancient logbook which documented some details on the later construction period of the Great Pyramid of Giza. Source:

Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities

By Alicia McDermott

Some of the details of the construction of the Egyptian Great Pyramid are revealed to the public for the first time when they go on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The information comes in the form of a papyri logbook written by an inspector named Merer. While much about the building of the pyramids remains unknown and speculative, the precious text sheds at least some light on the later aspects of the building process.

According to Live Science, Merer wrote in hieroglyphics how he was in charge of about 200 men and gave some information about the construction process while he was working on it in the 27th year of Khufu's reign.

Statue of Khufu in the Cairo Museum. (

Public Domain

)Writing on the document in 2014 (it was unearthed in 2013), the archaeologists Pierre Tallet and Gregory Marouard said that the pyramid was nearing completion when the text was written. Merer wrote that the work at that time was focused on creating the limestone casing to cover the pyramid.

Statue of Khufu in the Cairo Museum. (

Public Domain

)Writing on the document in 2014 (it was unearthed in 2013), the archaeologists Pierre Tallet and Gregory Marouard said that the pyramid was nearing completion when the text was written. Merer wrote that the work at that time was focused on creating the limestone casing to cover the pyramid.4,600-year-old step pyramid uncovered in Egypt and its purpose is a mysteryDiscovery of 5,000-year-old Hieroglyphs Change the Story of a Queen, a Pharaoh, and an Ancient CityThe archaeologists’ research on the logbook was published as an article in the journal Near Eastern Archaeology. They explained in their article that the document is comprised of more than 300 fragments of varying sizes and provides details on the inspector’s daily activities over several months.

Concentration of papyri in the rubble on which the logbook was written. (

P. Tallet

)The logbook was discovered at the Red Sea harbor of Wadi al-Jarf and Live Science reports that “It dates back about 4,500 years, making it the oldest papyrus document ever discovered in Egypt.”

Concentration of papyri in the rubble on which the logbook was written. (

P. Tallet

)The logbook was discovered at the Red Sea harbor of Wadi al-Jarf and Live Science reports that “It dates back about 4,500 years, making it the oldest papyrus document ever discovered in Egypt.”Apart from the information on daily activities, Merer’s log (and others found at the site) also provide additional interesting tidbits of data. The archaeologists wrote in their articles that:

“Merer's journal also mentions his passage at an important logistic and administrative center, ‘Ro-She Khufu’ - which seems to have functioned as a stopping point near by the Giza plateau. It is especially specified that this site is under the authority of a high rank official, Ankhhaef, half-brother of Khufu, who was his vizier and “chief for all the works of the king” at the end of the reign. Other logs found in the same archive also give information about others missions accomplished by the same team of sailors during the same year, notably the building of a Harbor on the Mediterranean Sea coast.”

Bust of Prince Ankhhaef, Khufu’s half-brother and vizier. ( Keith Schengili-Roberts/CC BY SA 2.5 ) Live Science reports that it is uncertain how long the logbook will be on display at the Egyptian Museum.

Sarcophagus of Egyptian High Priest Unearthed with Hieroglyphic Inscriptions and Scenes of Offerings Analysis Begins on Cosmic Particles in the Egyptian Bent Pyramid – Will This Help Explain How the Pyramids Were Built? The Great Pyramid, also known as the Pyramid of Cheops and Pyramid of Khufu, is comprised of more than 2 million limestone blocks weighing from 2 to 70 tons. Thus, it is interesting to note that Merer’s logbook explains from where this material was quarried and how it was transported towards the pyramid’s site. Tallet and Marouard’s article says that the logbook:

“records a period over the course of several months – in the form of a timetable with two columns per day – with many operations related to the construction of the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza and the work at the limestone quarries on the opposite bank of the Nile. On a regular basis, there are also descriptions concerning the transportation, on the Nile and connected canals, of stone blocks, which had been extracted from the northern and southern quarries of Tura. These blocks were delivered within two or three days at the pyramid construction site, called the ‘Horizon of Khufu’.”Some researchers say that the ’Horizon of Khufu’ refers to the pharaoh Khufu’s name for his necropolis.

Left: Part of a papyrus inscribed with an account dating to the reign of Khufu (13th cattle count). (

G. Pollin

) Right: Account on a papyrus (A) and a detail of one page of inspector Merer's “diary” (B), mentioning the “Horizon of Khufu.” (

G. Pollin

)The Great Pyramid is the only Giza pyramid that has air shafts . This pyramid was built with such precision that it has been said that it would be difficult to replicate it even with today’s technology. This point is one of the reasons why so many people are fascinated by the pyramid’s construction.

Left: Part of a papyrus inscribed with an account dating to the reign of Khufu (13th cattle count). (

G. Pollin

) Right: Account on a papyrus (A) and a detail of one page of inspector Merer's “diary” (B), mentioning the “Horizon of Khufu.” (

G. Pollin

)The Great Pyramid is the only Giza pyramid that has air shafts . This pyramid was built with such precision that it has been said that it would be difficult to replicate it even with today’s technology. This point is one of the reasons why so many people are fascinated by the pyramid’s construction.Within the Great Pyramid, there are areas that are called the King's Chamber, the Queen's Chamber, and the Subterranean Chamber. It should be noted however that there is much debate over these names and the purpose of the pyramid itself. Mainstream archaeology accepts that the pyramid was built around 2500 BC and commissioned by King Khufu for his tomb. However, much controversy surrounds these conclusions. For example, German archaeologists in 2013, argued that the Great Pyramid is much older and served a different purpose .

The debate over the pyramid’s construction and use continues to enthrall many researchers and, although work continues at the site, many of the questions behind this fascinating ancient structure remain unanswered.

The Great Pyramid of Giza. Source: BigStockPhoto Top Image: One of the papyri in the ancient logbook which documented some details on the later construction period of the Great Pyramid of Giza. Source:

Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities

The Great Pyramid of Giza. Source: BigStockPhoto Top Image: One of the papyri in the ancient logbook which documented some details on the later construction period of the Great Pyramid of Giza. Source:

Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities

By Alicia McDermott

Published on July 25, 2016 03:00

July 24, 2016

The 8 bloodiest Roman emperors in history

History Extra

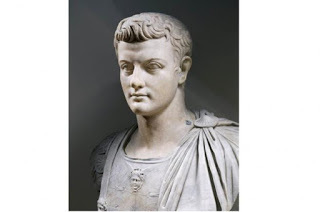

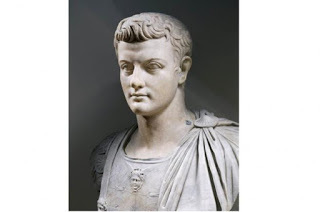

Marble bust of Roman emperor Gaius, known as Caligula, in AD 23. (Photo by DEA/A DAGLI ORTI/De Agostini/Getty Images)

We all know about the Roman Emperors, don't we? Mad, bad and decidedly dangerous to know. Who can forget Peter Ustinov's Nero in the 1951 epic Quo Vadis?, or John Hurt's tortured and murderous Caligula in the BBC's I, Claudius?

In fact, as historians point out (to anyone who will listen), many of the emperors on the list below were competent – even gifted – administrators, and the sources for some of the more lurid stories about them are not always above suspicion of exaggeration or invention. And some of the crimes that most shocked their contemporaries, like a penchant for performing in public, would not necessarily offend us so much today.

Some emperors, like Nero or Domitian, have passed into history as models of erratic, paranoid tyrants; others, like Diocletian, were able administrators, providing good government (unless you happened to be a Christian, in which case you were in great peril). Even under the worst emperors Rome continued to function, but involvement in public life could become a decidedly dangerous business.

Tiberius (ruled AD 14–37)Tiberius was the successor to Augustus, though Augustus did not particularly want Tiberius to succeed him, and it was only the untimely death of the emperor's grandsons Gaius and Lucius, and Augustus's decision to exile their younger brother, Agrippa Postumus, that put Tiberius in line for the imperial throne.

Tiberius was a gifted military commander and respected the authority of the senate. However, he had a gloomy and increasingly suspicious outlook that won him few friends and led him into a bitter dispute with Agrippina, the widow of his war hero nephew Germanicus. Fatally, Tiberius relied heavily on the ambitious and ruthless Aelius Sejanus, who instituted a reign of terror until Tiberius, learning that Sejanus planned to seize power himself, had him arrested and executed.

Tiberius sank into morbid suspicion of everyone around him: he retreated to the island of Capri and revived the ancient accusation of maiestas (treason) and used it to sentence to death anyone he suspected. Roman historians Suetonius and Tacitus give us a picture of Tiberius living on Capri as a depraved sexual predator, which may owe more to colourful imagination than to fact, though he certainly made use of a sheer drop into the sea to dispose of anyone he took issue with. Tiberius was not a monster in the mould of some of his successors, but he certainly set the tone for what was to come.

Bust of the Roman emperor Tiberius. (Photo by Art Media/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Gaius (Caligula) (ruled AD 37–41)Gaius (‘Caligula, or ‘little bootee’ – a childhood nickname given him by his father's troops) is best known for a series of eccentric actions, such as declaring war on the sea and proclaiming himself a god.

His reign actually began quite promisingly, but after a serious bout of illness he developed paranoia that led him into alarmingly erratic behaviour, possibly including incest with his sister, Julia Drusilla, whom he named as his heir.

Gaius took particular delight in humiliating the senate, claiming that he could make anyone consul, even his horse (though, contrary to the popular story, he didn't actually go through with this). As the son of Germanicus [a prominent general], Gaius was keen to establish his military credentials, though his campaign in Germany achieved little and his abortive invasion of Britain had to be turned into a battle with the sea god Neptune: he is said to have told his troops to attack the waves with their swords and gather seashells as booty.

Gaius declared himself a god and used his divine status to establish what was, in effect, an absolutist monarchy in Rome. He followed Tiberius's example of using treason trials to eliminate enemies, real or imagined. In the end it was his rather childish taunting of Cassius Chaerea, a member of the Praetorian guard, which brought Gaius down. Chaerea arranged for his assassination at the Palatine Games. He is supposed to have protested that he couldn't be killed because he was an immortal god, but he turned out to be rather less immortal than he thought.

Nero (ruled AD 54–68)Nero is the Roman Emperor we all love to hate, and not without reason. He was actually a competent administrator, and he was aided by some very able men, including his tutor – the writer Seneca. However, he was also unquestionably a murderer, starting with his step-brother Britannicus, with whom he had been supposed to share power, and progressing through his wife Octavia, whom he deserted for his lover, Poppeaea, and then had executed on a trumped-up charge of adultery.

Probably on Poppaea's prompting he had his own mother murdered, though the initial attempt, using a collapsible boat, went wrong, and she had to be beaten to death instead. He then kicked Poppaea to death in a fit of anger while she was pregnant with his child.

Roman emperor Nero. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Contrary to the myth, Nero did not start the great fire of Rome, nor did he ‘fiddle’ (nor even play the lyre), while the city burned – in fact, he organised relief work for its victims and planned the rebuilding. But Nero’s fondness for his own music and poetry, which made him force senators to sit through his own interminable and talentless recitals, meant people could easily believe it of him.

Nero was much hated for building his huge, tasteless ‘golden house’ complex [aka the Domus Aurea, a large landscaped portico villa] in the ruins of what had been the public area of central Rome. He undoubtedly persecuted Christians in large numbers, and his childish insistence on winning the laurels at the Olympic Games in Greece – whether or not he actually won, or indeed finished the race – brought the whole empire into disrepute.

Nero was toppled by an army revolt that sunk into a destructive three-way civil war.

Domitian (ruled AD 81–96)Domitian was the younger son of Vespasian, the general who had emerged from the chaos after Nero's fall and restored a certain element of stability and normality to Roman public life.

Domitian inherited none of his father's charm and, like others on this list, he suffered from deep suspicion of those around him, amounting to paranoia, possibly a result of his narrow escape from being killed during the civil war. He was particularly suspicious of the senate and had a number of leading citizens executed for conspiracy against him, including 12 ex-consuls and two of his own cousins.

Domitian’s rule became steadily more autocratic, and he demanded to be treated like a god. He turned against philosophers, sending many of them into exile, and he arranged the judicial murder of the chief vestal virgin, having her buried alive in a specially constructed tomb.

Domitian was eventually brought down by a conspiracy arranged by his wife, Domitia, and was somewhat inexpertly stabbed by a palace servant. Some historians think Domitian's tyranny has been overstated; others have compared him to Saddam Hussein at his most vengeful.

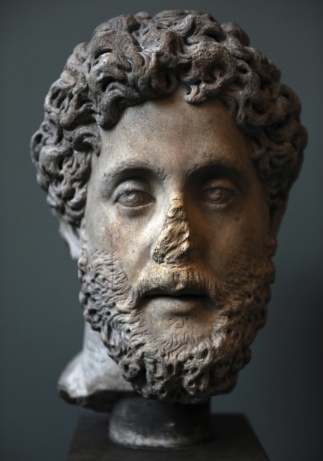

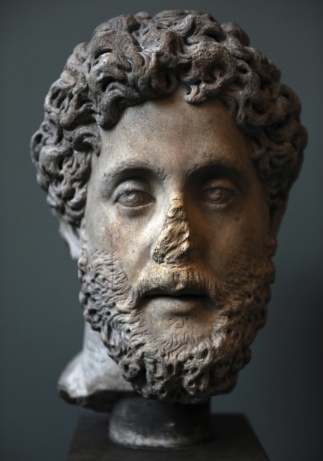

Commodus (ruled AD 180–192)Commodus was the emperor immortalised by Joaquin Phoenix in Ridley Scott's Gladiator (2000). Commodus was indeed a passionate follower of gladiatorial combat, and himself fought in the arena, sometimes dressed as Hercules, for which he awarded himself divine honours, declaring that he was a Roman Hercules.

Commodus was the son of the philosopher emperor Marcus Aurelius and, although the film's scene in which Commodus kills his own father is invention, it is true that Commodus was the very opposite of all that his father had stood for. Vain and pleasure-seeking, Commodus virtually bankrupted the Roman treasury and he sought to fill it up again by having wealthy citizens executed for treason so he could confiscate their property.

Soon, people began plotting against him for real, including his own sister. The plots were foiled, however, and Commodus set about executing still more people, either because they were conspiring against him or because he thought they might do so in the future. Eventually the Praetorian prefect and the emperor's own court chamberlain hired a professional athlete to strangle Commodus in the bath.

Bust of the emperor Commodus. (Photo by Anderson/Alinari via Getty Images)

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus I (Caracalla) (ruled AD 211–217)Marcus Aurelius Antoninus was the son of the highly able and effective emperor Septimius Severus. ‘Caracalla’ was a nickname, derived from a hooded coat from Gaul that he introduced into Rome.

Severus named his younger son, Geta, as co-heir with Caracalla, but the two quickly fell out and civil war seemed imminent until Caracalla averted this scenario by having Geta murdered.

Caracalla dealt brutally with opponents: he set about exterminating Geta's supporters, and similarly wiped out those caught up in one of the city of Alexandria's regular local risings against Roman rule.

Caracalla is remembered for the magnificent bath complex named after him in Rome, and for extending Roman citizenship to all free men within the empire ¬– though he was probably simply trying to raise the money he needed for his own lavish spending. He certainly turned the surplus he inherited from his father into a heavy deficit.

Caracalla was a successful, if ruthless, military commander but he was assassinated by a group of ambitious army officers, including the Praetorian prefect Opellius Macrinus, who promptly proclaimed himself emperor.

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus II (Elagabalus) (ruled AD 218–222)Elagabalus was a relative of Septimius Severus's wife, put forward to challenge Macrinus for the throne after the murder of Caracalla. Elagabalus overthrew Macrinus and promptly embarked on an increasingly eccentric reign. His nickname came from his role as priest of the cult of the Syrian god Elah-Gabal, which he tried to introduce into Rome to universal consternation, even having himself circumcised to show his devotion to the cult.

Elagabalus deliberately offended Roman moral and religious principles, setting up a conical black stone fetish – a symbol of the sun god Sol Invictus Elagabalus – on the Palatine Hill and marrying the chief vestal, for which, under normal circumstances, she should have been put to death.

Romans were particularly offended by Elagabalus’s sexual behaviour – as well as a string of marriages he also openly took male lovers, and he seems to have been what would nowadays be recognised as transgender.

Few historians have much good to say about Elagablus, and eventually the Romans' patience gave out: Elagabalus was murdered in a conspiracy organised by his own grandmother.

Diocletian (AD 284–305)It may seem unfair to include Diocletian in this group, since he is best known for the risky but sensible decision to divide the government of the Roman empire in two, taking Marcus Aurelius Maximianus as his co-emperor, each with a subordinate known as a Caesar, in a four-way division of power called the tetrarchy.

Diocletian was a good administrator, and managed to hold his divided command structure together at a time when the Roman empire was coming under increasing pressure from its enemies outside its boundaries. What gets Diocletian included here, however, is his utterly ruthless persecution of Christians.

Christians had long been regarded by most Romans with a mixture of distaste and a rather amused tolerance, but Diocletian set about the total eradication of the religion. Churches were to be destroyed, scriptures publicly burnt, and Christian priests imprisoned and forced to conduct sacrifices to the emperor on pain of death. Christians who refused to give up their faith were tortured and executed.

It was an unusually vicious persecution, given that the Romans were usually accepting of other religions, and it reflects Diocletian's fear that, at a time when unity of purpose was essential for the empire's survival, Christianity represented a rejection of Roman religious values that he could not afford to allow.

Sean Lang is a senior lecturer in history at Anglia Ruskin University, and the author of publications including British History for Dummies (2004), European History for Dummies (2011) and First World War for Dummies (2014).

Marble bust of Roman emperor Gaius, known as Caligula, in AD 23. (Photo by DEA/A DAGLI ORTI/De Agostini/Getty Images)

We all know about the Roman Emperors, don't we? Mad, bad and decidedly dangerous to know. Who can forget Peter Ustinov's Nero in the 1951 epic Quo Vadis?, or John Hurt's tortured and murderous Caligula in the BBC's I, Claudius?

In fact, as historians point out (to anyone who will listen), many of the emperors on the list below were competent – even gifted – administrators, and the sources for some of the more lurid stories about them are not always above suspicion of exaggeration or invention. And some of the crimes that most shocked their contemporaries, like a penchant for performing in public, would not necessarily offend us so much today.

Some emperors, like Nero or Domitian, have passed into history as models of erratic, paranoid tyrants; others, like Diocletian, were able administrators, providing good government (unless you happened to be a Christian, in which case you were in great peril). Even under the worst emperors Rome continued to function, but involvement in public life could become a decidedly dangerous business.

Tiberius (ruled AD 14–37)Tiberius was the successor to Augustus, though Augustus did not particularly want Tiberius to succeed him, and it was only the untimely death of the emperor's grandsons Gaius and Lucius, and Augustus's decision to exile their younger brother, Agrippa Postumus, that put Tiberius in line for the imperial throne.

Tiberius was a gifted military commander and respected the authority of the senate. However, he had a gloomy and increasingly suspicious outlook that won him few friends and led him into a bitter dispute with Agrippina, the widow of his war hero nephew Germanicus. Fatally, Tiberius relied heavily on the ambitious and ruthless Aelius Sejanus, who instituted a reign of terror until Tiberius, learning that Sejanus planned to seize power himself, had him arrested and executed.

Tiberius sank into morbid suspicion of everyone around him: he retreated to the island of Capri and revived the ancient accusation of maiestas (treason) and used it to sentence to death anyone he suspected. Roman historians Suetonius and Tacitus give us a picture of Tiberius living on Capri as a depraved sexual predator, which may owe more to colourful imagination than to fact, though he certainly made use of a sheer drop into the sea to dispose of anyone he took issue with. Tiberius was not a monster in the mould of some of his successors, but he certainly set the tone for what was to come.

Bust of the Roman emperor Tiberius. (Photo by Art Media/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Gaius (Caligula) (ruled AD 37–41)Gaius (‘Caligula, or ‘little bootee’ – a childhood nickname given him by his father's troops) is best known for a series of eccentric actions, such as declaring war on the sea and proclaiming himself a god.

His reign actually began quite promisingly, but after a serious bout of illness he developed paranoia that led him into alarmingly erratic behaviour, possibly including incest with his sister, Julia Drusilla, whom he named as his heir.

Gaius took particular delight in humiliating the senate, claiming that he could make anyone consul, even his horse (though, contrary to the popular story, he didn't actually go through with this). As the son of Germanicus [a prominent general], Gaius was keen to establish his military credentials, though his campaign in Germany achieved little and his abortive invasion of Britain had to be turned into a battle with the sea god Neptune: he is said to have told his troops to attack the waves with their swords and gather seashells as booty.

Gaius declared himself a god and used his divine status to establish what was, in effect, an absolutist monarchy in Rome. He followed Tiberius's example of using treason trials to eliminate enemies, real or imagined. In the end it was his rather childish taunting of Cassius Chaerea, a member of the Praetorian guard, which brought Gaius down. Chaerea arranged for his assassination at the Palatine Games. He is supposed to have protested that he couldn't be killed because he was an immortal god, but he turned out to be rather less immortal than he thought.

Nero (ruled AD 54–68)Nero is the Roman Emperor we all love to hate, and not without reason. He was actually a competent administrator, and he was aided by some very able men, including his tutor – the writer Seneca. However, he was also unquestionably a murderer, starting with his step-brother Britannicus, with whom he had been supposed to share power, and progressing through his wife Octavia, whom he deserted for his lover, Poppeaea, and then had executed on a trumped-up charge of adultery.

Probably on Poppaea's prompting he had his own mother murdered, though the initial attempt, using a collapsible boat, went wrong, and she had to be beaten to death instead. He then kicked Poppaea to death in a fit of anger while she was pregnant with his child.

Roman emperor Nero. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Contrary to the myth, Nero did not start the great fire of Rome, nor did he ‘fiddle’ (nor even play the lyre), while the city burned – in fact, he organised relief work for its victims and planned the rebuilding. But Nero’s fondness for his own music and poetry, which made him force senators to sit through his own interminable and talentless recitals, meant people could easily believe it of him.

Nero was much hated for building his huge, tasteless ‘golden house’ complex [aka the Domus Aurea, a large landscaped portico villa] in the ruins of what had been the public area of central Rome. He undoubtedly persecuted Christians in large numbers, and his childish insistence on winning the laurels at the Olympic Games in Greece – whether or not he actually won, or indeed finished the race – brought the whole empire into disrepute.

Nero was toppled by an army revolt that sunk into a destructive three-way civil war.

Domitian (ruled AD 81–96)Domitian was the younger son of Vespasian, the general who had emerged from the chaos after Nero's fall and restored a certain element of stability and normality to Roman public life.

Domitian inherited none of his father's charm and, like others on this list, he suffered from deep suspicion of those around him, amounting to paranoia, possibly a result of his narrow escape from being killed during the civil war. He was particularly suspicious of the senate and had a number of leading citizens executed for conspiracy against him, including 12 ex-consuls and two of his own cousins.

Domitian’s rule became steadily more autocratic, and he demanded to be treated like a god. He turned against philosophers, sending many of them into exile, and he arranged the judicial murder of the chief vestal virgin, having her buried alive in a specially constructed tomb.

Domitian was eventually brought down by a conspiracy arranged by his wife, Domitia, and was somewhat inexpertly stabbed by a palace servant. Some historians think Domitian's tyranny has been overstated; others have compared him to Saddam Hussein at his most vengeful.

Commodus (ruled AD 180–192)Commodus was the emperor immortalised by Joaquin Phoenix in Ridley Scott's Gladiator (2000). Commodus was indeed a passionate follower of gladiatorial combat, and himself fought in the arena, sometimes dressed as Hercules, for which he awarded himself divine honours, declaring that he was a Roman Hercules.

Commodus was the son of the philosopher emperor Marcus Aurelius and, although the film's scene in which Commodus kills his own father is invention, it is true that Commodus was the very opposite of all that his father had stood for. Vain and pleasure-seeking, Commodus virtually bankrupted the Roman treasury and he sought to fill it up again by having wealthy citizens executed for treason so he could confiscate their property.

Soon, people began plotting against him for real, including his own sister. The plots were foiled, however, and Commodus set about executing still more people, either because they were conspiring against him or because he thought they might do so in the future. Eventually the Praetorian prefect and the emperor's own court chamberlain hired a professional athlete to strangle Commodus in the bath.

Bust of the emperor Commodus. (Photo by Anderson/Alinari via Getty Images)

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus I (Caracalla) (ruled AD 211–217)Marcus Aurelius Antoninus was the son of the highly able and effective emperor Septimius Severus. ‘Caracalla’ was a nickname, derived from a hooded coat from Gaul that he introduced into Rome.

Severus named his younger son, Geta, as co-heir with Caracalla, but the two quickly fell out and civil war seemed imminent until Caracalla averted this scenario by having Geta murdered.

Caracalla dealt brutally with opponents: he set about exterminating Geta's supporters, and similarly wiped out those caught up in one of the city of Alexandria's regular local risings against Roman rule.

Caracalla is remembered for the magnificent bath complex named after him in Rome, and for extending Roman citizenship to all free men within the empire ¬– though he was probably simply trying to raise the money he needed for his own lavish spending. He certainly turned the surplus he inherited from his father into a heavy deficit.

Caracalla was a successful, if ruthless, military commander but he was assassinated by a group of ambitious army officers, including the Praetorian prefect Opellius Macrinus, who promptly proclaimed himself emperor.

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus II (Elagabalus) (ruled AD 218–222)Elagabalus was a relative of Septimius Severus's wife, put forward to challenge Macrinus for the throne after the murder of Caracalla. Elagabalus overthrew Macrinus and promptly embarked on an increasingly eccentric reign. His nickname came from his role as priest of the cult of the Syrian god Elah-Gabal, which he tried to introduce into Rome to universal consternation, even having himself circumcised to show his devotion to the cult.

Elagabalus deliberately offended Roman moral and religious principles, setting up a conical black stone fetish – a symbol of the sun god Sol Invictus Elagabalus – on the Palatine Hill and marrying the chief vestal, for which, under normal circumstances, she should have been put to death.

Romans were particularly offended by Elagabalus’s sexual behaviour – as well as a string of marriages he also openly took male lovers, and he seems to have been what would nowadays be recognised as transgender.

Few historians have much good to say about Elagablus, and eventually the Romans' patience gave out: Elagabalus was murdered in a conspiracy organised by his own grandmother.

Diocletian (AD 284–305)It may seem unfair to include Diocletian in this group, since he is best known for the risky but sensible decision to divide the government of the Roman empire in two, taking Marcus Aurelius Maximianus as his co-emperor, each with a subordinate known as a Caesar, in a four-way division of power called the tetrarchy.

Diocletian was a good administrator, and managed to hold his divided command structure together at a time when the Roman empire was coming under increasing pressure from its enemies outside its boundaries. What gets Diocletian included here, however, is his utterly ruthless persecution of Christians.

Christians had long been regarded by most Romans with a mixture of distaste and a rather amused tolerance, but Diocletian set about the total eradication of the religion. Churches were to be destroyed, scriptures publicly burnt, and Christian priests imprisoned and forced to conduct sacrifices to the emperor on pain of death. Christians who refused to give up their faith were tortured and executed.

It was an unusually vicious persecution, given that the Romans were usually accepting of other religions, and it reflects Diocletian's fear that, at a time when unity of purpose was essential for the empire's survival, Christianity represented a rejection of Roman religious values that he could not afford to allow.

Sean Lang is a senior lecturer in history at Anglia Ruskin University, and the author of publications including British History for Dummies (2004), European History for Dummies (2011) and First World War for Dummies (2014).

Published on July 24, 2016 02:30

July 23, 2016

Prehistoric village people

History Extra

Houses of the Neolithic settlement of Skara Brae. (Photo by Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert/Getty Images)

Packed with historic sites of all ages from prehistoric remains to World War II wrecks in Scapa Flow, there’s more than enough history on mainland Orkney and the outer islands to hold your interest for weeks.It’s the prehistoric remains for which Orkney is most remarkable, particularly those of the Neolithic period (around 4000–2000BC). This was when agriculture first became established in Britain, and people began to start living in permanent settlements based around farms. This was a change from the mobile lifestyle of the Mesolithic period (10000–4000BC), when they moved following the seasonal round of hunting and gathering.The Mesolithic people have left little evidence of their passing in these islands. Their settlements weren’t built to last, so the ephemeral remains of their homes can only be traced by careful archaeological excavation. With the onset of the Neolithic and the move from hunting to agriculture as the way of life, however, our ancestors began to make more of a dent on the landscape: their settlements, their monuments, and sometimes even their trackways and field systems survive.It’s generally easier to see the remains of death, burial and ritual of our Neolithic forebears than it is to see their settlements. These were the people who built long barrows, such as the well-preserved example at West Kennet in Wiltshire, as tombs for their ancestors. They are also responsible for henges and stone circles, Stonehenge being the most obvious example, and even more enigmatic ritual monuments like the massive man-made mound of Silbury Hill, again in Wiltshire.Large earthwork and stone monuments like these are easy to spot in the landscape, but it’s harder to find evidence of the places where the Neolithic people who built them lived. And that’s where Orkney comes into its own – here you can see both settlements and monuments in one place; that’s why much of the mainland island has been designated a World Heritage Site. Our voyage of discovery takes in the heart of Neolithic Orkney: Maeshowe is one of the finest examples of a prehistoric burial mound in Britain, the Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar are impressive examples of the ritual monuments of the time, whilst the villages of Skara Brae and Barnhouse are amongst the best-preserved Neolithic settlement sites in Britain. With this astonishing combination of archaeological sites, the area is one of the only places in the country where you can get a real feel for the way of life of Britain’s first farmers.Orkney archaeologist Julie Gibson knows more than most about the islands’ heritage. She sums up what you can see; “If you go to Barnhouse, you are actually in a village lived in by the people who put up the Stones of Stenness next door.”The reason you can still see Barnhouse and Skara Brae boils down to the availability of natural resources. High winds have been battering the islands for thousands of years, so trees have struggled to survive. On mainland Britain, excavations have shown that Neolithic settlements were of wood, which has since rotted away. The Orcadians lacked timber but did have a ready supply of a more permanent material: stone. Their villages survive because they are constructed of sandstone slabs, which lie ready-quarried by the sea all around the coast.“Because they built in stone, so it leaves everything in 3D,” explains Julie. “In the rest of the country you’re dealing with wooden structures in prehistory, so archaeologists are left with negative evidence and have to play the game of join-the-dots. Here you’ve got positive evidence so the past is that much clearer.”There aren’t many places in the world that can boast a practically intact 5,000-year-old village. Skara Brae was occupied from around 3100BC to 2500BC, and after that it was hidden under a sand dune until a wild storm revealed it in the winter of 1850. The village is unlike any you’ll see today. It’s a semi-subterranean place, built inside a huge mound of decomposed vegetable matter, dung, animal bones, stone and shell. The midden was built on the site first and then roundhouses and connecting passageways were dug into the massive compost heap. The homes were therefore cocooned from the excesses of Atlantic weather by a layer of insulating matter.Ten houses are visible at Skara Brae (though they were not all built and occupied at the same time). They are single-room affairs revetted with dry stone walling and each one would have had a roof supported either by timber, if it was available, or whalebone. The roofs are gone now so you look down into the houses from above, and what you see inside is amazing. All the furniture was of stone, so beds, cupboards, dressers, stone boxes, hearths and doors all survive. The interior of a Neolithic house at Skara Brae, Orkney. (Photo by Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images)Each house has about 36 square metres of floor space, more than half the average floor space of a modern two-bed house (61.5 square metres), so an estate agent would probably describe them as spacious studio apartments. Their low doorways and the winding passages prevented the wind rushing in, and with a fire in the central hearth, you can imagine a picture of cosy domesticity you wouldn’t normally associate with prehistory. As all the houses are similar in size and fittings without anything that looks like a chief’s dwelling, Skara Brae is generally thought to have been an egalitarian society where all members were roughly equal in status.Life wasn’t idyllic for the people of Skara Brae, however, as Julie explains. “If you look at the skeletal material, you became very aware of the humanity of the people you’re dealing with. Terrible arthritis, heads grooved by carrying baskets round their heads. These were people only marginally shorter than us, people who are clearly us – only a long time ago – whose thought processes you have to reach through analogy – that’s what makes it difficult to understand them.”We may not know what they thought but we do have a fair idea of what they did during the day. Archaeologists have concluded the villagers were fishermen and farmers who grew barley and wheat, kept cattle, sheep and pigs, and supplemented their diet with seafood and sea-birds. The 20 or so families that lived in the village seem to have had peaceful relations with their neighbours around the islands as Skara Brae wasn’t built for defence and no weaponry has been found. Several similar villages have been discovered in the Orkneys, including the nearby one at Barnhouse.Instead of fighting one another, the villagers appear to have devoted their spare time to building tombs and monuments. And they must have had a fair bit of time to spare; it’s estimated that it would have taken 150,000 hours to build the two stone circles of Stenness and Brodgar. The Stones of Stenness are thought to have been in existence by 3000BC, so it was contemporary with the occupation of Skara Brae (3100–2500BC). Brodgar is thought to be a little later, probably dating to the middle of the third millennium BC. The huge circular tomb of Maeshowe is also thought to be roughly contemporary – built some time after 3000BC and possibly used for centuries thereafter.The two stone circles sit on narrow promontories of land looking out over the lochs of Harray and Stenness. Brodgar is the bigger, but both occupy dramatically scenic locations. The sheer scale of Brodgar can’t fail to impress and bring home the amount of work that went into it.Maeshowe is an entirely different sort of monument. You can see its mound from the Stones of Stenness, and though it’s not much to look at on the outside, when you get inside you know you’re in a very special place.You have to shuffle through a low narrow slab-lined passage to get inside. Consider as you do that your shoulders are rubbing on the same stones that the Neolithic builders touched 5,000 years ago. Once inside, you’re standing in one of the best examples of a chambered tomb in Britain.These sorts of tombs are numerous in the Orkneys and archaeologists conjecture, from what’s been found in the others, that each of the side cells at Maeshowe would have held the bones of many members of the local population. In similar monuments, the bones of many people have been discovered, jumbled together in a pattern not comprehensible to modern eyes.We don’t know for sure what was in Maeshowe because the tomb was raided by Vikings 1,000 years ago (you can see their runic graffiti on the walls) and the place contained only a single skull fragment when excavated in the 19th century. Nevertheless, it’s a uniquely atmospheric place to visit and a supreme example of the Neolithic stonemason’s skill.Given that all these mighty monuments were built at around the same time as Skara Brae was occupied, and lie only a few miles from the settlement, it’s an obvious conclusion to make that the villagers were involved in the construction and use of the stones and tomb. To add weight to the argument, a specific type of pottery, grooved ware, has been found in excavations at all these places. As you wander round the stones at Stenness and Brodgar, or crouch down at the entrance of Maeshowe, there’s one question that springs to mind: ‘Why did the villagers of Skara Brae go to all the trouble of constructing these places?’ We’ll never know for certain. Without written records, all we can do is theorise. It is likely some ritual was carried out inside the circles, perhaps based on astronomical calculations, or on some sort of religion, but that’s as much as we can say without delving into mere conjecture.Archaeologists suggest that monuments like Maeshowe were required in the Neolithic period, because people needed, in a way they’d never felt before, to associate themselves with the land they had started to farm so others couldn’t take it away. One way to create a sense of ownership was to develop an ancestor cult, burying their forefathers’ bones near the land they considered theirs and performing ceremonies to strengthen their age-old claim to their territory.One thing is certain; it took a massive community effort to build these structures. It was certainly more than a job that just the small population of Skara Brae could have managed, and this has led to another theory; that the building of Maeshowe suggests a move from self-governing villages to a regional authority which organised people throughout the Orkneys to build the tomb.The social bonds of close-knit settlements like Skara Brae would have broken down as people began to associate more with the regional power than the old independent village structure, perhaps leaving the village to live in smaller farmsteads. It’s a reasonable explanation for why Skara Brae was abandoned; another more prosaic possibility is that the place was overwhelmed by a huge sandstorm.Either way, the magnificent remains are there to see today. If you want to get a first-hand impression of the way of life, and death, of the first farmers in the British Isles, Orkney is the closest place you’ll get to experiencing it.

The interior of a Neolithic house at Skara Brae, Orkney. (Photo by Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images)Each house has about 36 square metres of floor space, more than half the average floor space of a modern two-bed house (61.5 square metres), so an estate agent would probably describe them as spacious studio apartments. Their low doorways and the winding passages prevented the wind rushing in, and with a fire in the central hearth, you can imagine a picture of cosy domesticity you wouldn’t normally associate with prehistory. As all the houses are similar in size and fittings without anything that looks like a chief’s dwelling, Skara Brae is generally thought to have been an egalitarian society where all members were roughly equal in status.Life wasn’t idyllic for the people of Skara Brae, however, as Julie explains. “If you look at the skeletal material, you became very aware of the humanity of the people you’re dealing with. Terrible arthritis, heads grooved by carrying baskets round their heads. These were people only marginally shorter than us, people who are clearly us – only a long time ago – whose thought processes you have to reach through analogy – that’s what makes it difficult to understand them.”We may not know what they thought but we do have a fair idea of what they did during the day. Archaeologists have concluded the villagers were fishermen and farmers who grew barley and wheat, kept cattle, sheep and pigs, and supplemented their diet with seafood and sea-birds. The 20 or so families that lived in the village seem to have had peaceful relations with their neighbours around the islands as Skara Brae wasn’t built for defence and no weaponry has been found. Several similar villages have been discovered in the Orkneys, including the nearby one at Barnhouse.Instead of fighting one another, the villagers appear to have devoted their spare time to building tombs and monuments. And they must have had a fair bit of time to spare; it’s estimated that it would have taken 150,000 hours to build the two stone circles of Stenness and Brodgar. The Stones of Stenness are thought to have been in existence by 3000BC, so it was contemporary with the occupation of Skara Brae (3100–2500BC). Brodgar is thought to be a little later, probably dating to the middle of the third millennium BC. The huge circular tomb of Maeshowe is also thought to be roughly contemporary – built some time after 3000BC and possibly used for centuries thereafter.The two stone circles sit on narrow promontories of land looking out over the lochs of Harray and Stenness. Brodgar is the bigger, but both occupy dramatically scenic locations. The sheer scale of Brodgar can’t fail to impress and bring home the amount of work that went into it.Maeshowe is an entirely different sort of monument. You can see its mound from the Stones of Stenness, and though it’s not much to look at on the outside, when you get inside you know you’re in a very special place.You have to shuffle through a low narrow slab-lined passage to get inside. Consider as you do that your shoulders are rubbing on the same stones that the Neolithic builders touched 5,000 years ago. Once inside, you’re standing in one of the best examples of a chambered tomb in Britain.These sorts of tombs are numerous in the Orkneys and archaeologists conjecture, from what’s been found in the others, that each of the side cells at Maeshowe would have held the bones of many members of the local population. In similar monuments, the bones of many people have been discovered, jumbled together in a pattern not comprehensible to modern eyes.We don’t know for sure what was in Maeshowe because the tomb was raided by Vikings 1,000 years ago (you can see their runic graffiti on the walls) and the place contained only a single skull fragment when excavated in the 19th century. Nevertheless, it’s a uniquely atmospheric place to visit and a supreme example of the Neolithic stonemason’s skill.Given that all these mighty monuments were built at around the same time as Skara Brae was occupied, and lie only a few miles from the settlement, it’s an obvious conclusion to make that the villagers were involved in the construction and use of the stones and tomb. To add weight to the argument, a specific type of pottery, grooved ware, has been found in excavations at all these places. As you wander round the stones at Stenness and Brodgar, or crouch down at the entrance of Maeshowe, there’s one question that springs to mind: ‘Why did the villagers of Skara Brae go to all the trouble of constructing these places?’ We’ll never know for certain. Without written records, all we can do is theorise. It is likely some ritual was carried out inside the circles, perhaps based on astronomical calculations, or on some sort of religion, but that’s as much as we can say without delving into mere conjecture.Archaeologists suggest that monuments like Maeshowe were required in the Neolithic period, because people needed, in a way they’d never felt before, to associate themselves with the land they had started to farm so others couldn’t take it away. One way to create a sense of ownership was to develop an ancestor cult, burying their forefathers’ bones near the land they considered theirs and performing ceremonies to strengthen their age-old claim to their territory.One thing is certain; it took a massive community effort to build these structures. It was certainly more than a job that just the small population of Skara Brae could have managed, and this has led to another theory; that the building of Maeshowe suggests a move from self-governing villages to a regional authority which organised people throughout the Orkneys to build the tomb.The social bonds of close-knit settlements like Skara Brae would have broken down as people began to associate more with the regional power than the old independent village structure, perhaps leaving the village to live in smaller farmsteads. It’s a reasonable explanation for why Skara Brae was abandoned; another more prosaic possibility is that the place was overwhelmed by a huge sandstorm.Either way, the magnificent remains are there to see today. If you want to get a first-hand impression of the way of life, and death, of the first farmers in the British Isles, Orkney is the closest place you’ll get to experiencing it.

Houses of the Neolithic settlement of Skara Brae. (Photo by Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert/Getty Images)

Packed with historic sites of all ages from prehistoric remains to World War II wrecks in Scapa Flow, there’s more than enough history on mainland Orkney and the outer islands to hold your interest for weeks.It’s the prehistoric remains for which Orkney is most remarkable, particularly those of the Neolithic period (around 4000–2000BC). This was when agriculture first became established in Britain, and people began to start living in permanent settlements based around farms. This was a change from the mobile lifestyle of the Mesolithic period (10000–4000BC), when they moved following the seasonal round of hunting and gathering.The Mesolithic people have left little evidence of their passing in these islands. Their settlements weren’t built to last, so the ephemeral remains of their homes can only be traced by careful archaeological excavation. With the onset of the Neolithic and the move from hunting to agriculture as the way of life, however, our ancestors began to make more of a dent on the landscape: their settlements, their monuments, and sometimes even their trackways and field systems survive.It’s generally easier to see the remains of death, burial and ritual of our Neolithic forebears than it is to see their settlements. These were the people who built long barrows, such as the well-preserved example at West Kennet in Wiltshire, as tombs for their ancestors. They are also responsible for henges and stone circles, Stonehenge being the most obvious example, and even more enigmatic ritual monuments like the massive man-made mound of Silbury Hill, again in Wiltshire.Large earthwork and stone monuments like these are easy to spot in the landscape, but it’s harder to find evidence of the places where the Neolithic people who built them lived. And that’s where Orkney comes into its own – here you can see both settlements and monuments in one place; that’s why much of the mainland island has been designated a World Heritage Site. Our voyage of discovery takes in the heart of Neolithic Orkney: Maeshowe is one of the finest examples of a prehistoric burial mound in Britain, the Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar are impressive examples of the ritual monuments of the time, whilst the villages of Skara Brae and Barnhouse are amongst the best-preserved Neolithic settlement sites in Britain. With this astonishing combination of archaeological sites, the area is one of the only places in the country where you can get a real feel for the way of life of Britain’s first farmers.Orkney archaeologist Julie Gibson knows more than most about the islands’ heritage. She sums up what you can see; “If you go to Barnhouse, you are actually in a village lived in by the people who put up the Stones of Stenness next door.”The reason you can still see Barnhouse and Skara Brae boils down to the availability of natural resources. High winds have been battering the islands for thousands of years, so trees have struggled to survive. On mainland Britain, excavations have shown that Neolithic settlements were of wood, which has since rotted away. The Orcadians lacked timber but did have a ready supply of a more permanent material: stone. Their villages survive because they are constructed of sandstone slabs, which lie ready-quarried by the sea all around the coast.“Because they built in stone, so it leaves everything in 3D,” explains Julie. “In the rest of the country you’re dealing with wooden structures in prehistory, so archaeologists are left with negative evidence and have to play the game of join-the-dots. Here you’ve got positive evidence so the past is that much clearer.”There aren’t many places in the world that can boast a practically intact 5,000-year-old village. Skara Brae was occupied from around 3100BC to 2500BC, and after that it was hidden under a sand dune until a wild storm revealed it in the winter of 1850. The village is unlike any you’ll see today. It’s a semi-subterranean place, built inside a huge mound of decomposed vegetable matter, dung, animal bones, stone and shell. The midden was built on the site first and then roundhouses and connecting passageways were dug into the massive compost heap. The homes were therefore cocooned from the excesses of Atlantic weather by a layer of insulating matter.Ten houses are visible at Skara Brae (though they were not all built and occupied at the same time). They are single-room affairs revetted with dry stone walling and each one would have had a roof supported either by timber, if it was available, or whalebone. The roofs are gone now so you look down into the houses from above, and what you see inside is amazing. All the furniture was of stone, so beds, cupboards, dressers, stone boxes, hearths and doors all survive.