MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 91

June 30, 2016

Great Pyramid of Giza Was Lopsided Due to Construction Error

Ancient Origins

Research carried out by engineer Glen Dash and Egyptologist Mark Lehner has revealed that the Great Pyramid of Giza is not as perfect as once believed. Results of testing showed that its base was built lopsided.

According to LiveScience, the builders of the Great Pyramid made a small mistake while constructing it. The new research reveals that the west side of the pyramid is slightly longer than the east side. It means that the long lasting myth about the perfection of this construction is not true. Dash and Lehner detected the small flaw in a new measuring project carried out with the support of Glen Dash Research Foundation and Ancient Egypt Research Associates (AERA). Mapping and excavating the Giza plateau by AERA took about 30 years.

As Glen Dash wrote in his report:

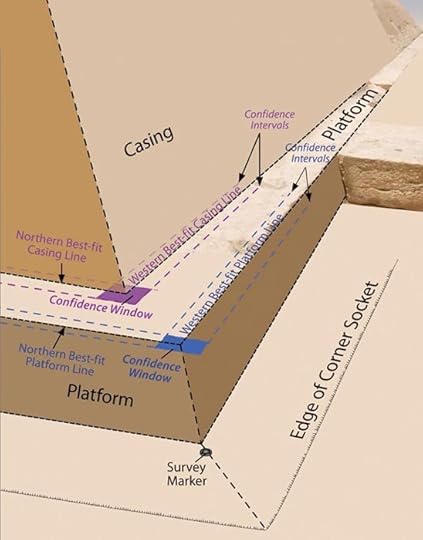

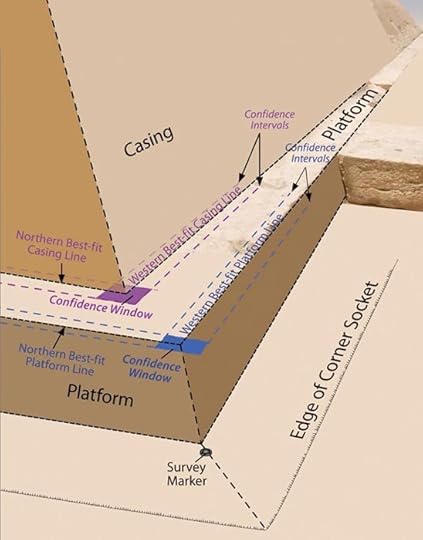

Researchers took measurements of the Great Pyramid's edges and platform, showing what one of the corners may have looked like when built. Researchers noticed a "corner socket," or a cutting in the rock, whose purpose remains unclear. Credit: Image courtesy of Glen DashLehner undertook research to determine the lengths of the original pyramid sides. His team looked for surviving casing stones situated at the foot of the pyramid's platform, and which would have formed the pyramid's original casing baseline. They found 84 points along 155 meters (508 feet) of the original edges of the pyramid, which were marked on a grid system. It was used for mapping all of the features on the Giza Plateau. The obtained data was then processed to receive the most precise outline of the Great Pyramid, which allowed the projection of the original lengths of the pyramid's base.

Researchers took measurements of the Great Pyramid's edges and platform, showing what one of the corners may have looked like when built. Researchers noticed a "corner socket," or a cutting in the rock, whose purpose remains unclear. Credit: Image courtesy of Glen DashLehner undertook research to determine the lengths of the original pyramid sides. His team looked for surviving casing stones situated at the foot of the pyramid's platform, and which would have formed the pyramid's original casing baseline. They found 84 points along 155 meters (508 feet) of the original edges of the pyramid, which were marked on a grid system. It was used for mapping all of the features on the Giza Plateau. The obtained data was then processed to receive the most precise outline of the Great Pyramid, which allowed the projection of the original lengths of the pyramid's base.

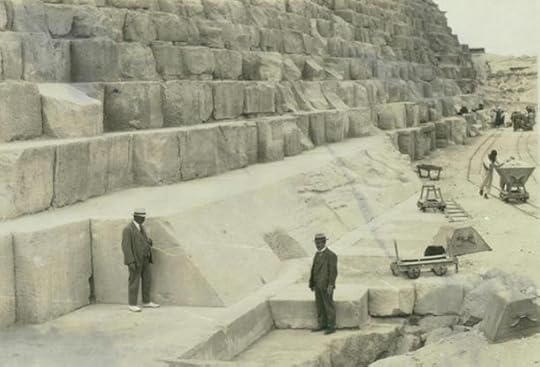

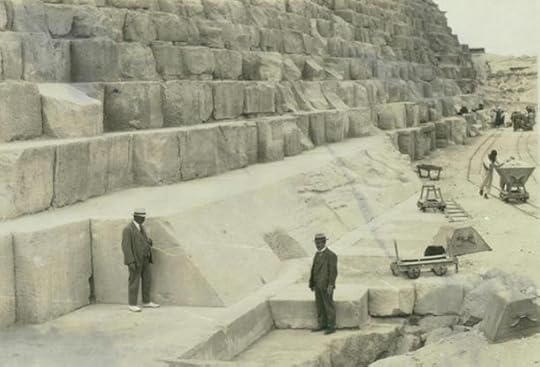

The Casing Stones can be seen here at the base of the pyramid (

Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library / Flickr

)The results surprised the researchers, who proved that the pyramid originally measured between 230.3 and 230.4 meters (755.6 and 755.8 feet), while the west side of the pyramid originally measured somewhere between 230.4 to 230.4 meters (755.8 and 756.0 feet). It means that the west side was 5.55 inches (14.1 centimeters) longer than the east side. The researchers claimed that the previous measurements of the Great Pyramid were not exactly correct, and the error in construction comes from ancient times.

The Casing Stones can be seen here at the base of the pyramid (

Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library / Flickr

)The results surprised the researchers, who proved that the pyramid originally measured between 230.3 and 230.4 meters (755.6 and 755.8 feet), while the west side of the pyramid originally measured somewhere between 230.4 to 230.4 meters (755.8 and 756.0 feet). It means that the west side was 5.55 inches (14.1 centimeters) longer than the east side. The researchers claimed that the previous measurements of the Great Pyramid were not exactly correct, and the error in construction comes from ancient times.

According to Dash, the ancient Egyptians laid out the pyramid on a grid. The north-south meridian of the pyramid runs 3 minutes 54 seconds west of due north while its east-west axis runs 3 minutes 51 seconds north of due east. Moreover, the east-west meridian runs through the center of the temple built on the east side of the pyramid too. The measurements by Dash and Lehner prove that the Great Pyramid is oriented slightly away from the cardinal directions. The analysis of the data gathered by the team led by Dash and Lehner will be continued.

In January 2014, April Holloway from Ancient Origins reported about a different discovery of Mark Lehner. His team made some new discoveries ''including the remains of a bustling port, as well as barracks for sailors or military troops near the Giza pyramids. The findings shed new light on what life was like in the region thousands of years ago.

Archaeologist Mark Lehner, director of Ancient Egypt Research Associates, has said that the discoveries suggest Giza was a thriving port, at least 4,500 years ago. Lehner's team discovered a basin, which may be an extension of a harbour, near the Khentkawes town just 1 kilometre from the nearest Nile River channel.

"Giza was the central port then for three generations, Khufu, Khafre, Menkaure," said Lehner, referring to the three pharaohs who built pyramids at Giza.

Archaeologists also discovered a series of long buildings, called ‘galleries’, which they believe were used as barracks, either for sailors or for soldiers. The buildings were about 7 metres high and 35 metres long and could have held about 40 troops in each one. These troops may have been participating in voyages from the port to the Levant, or soldiers who may have been used for guarding kings and queens while at Giza.''

Top image: The Great Pyramid of Egypt. Source: BigStockPhoto

By Natalia Klimzcak

Research carried out by engineer Glen Dash and Egyptologist Mark Lehner has revealed that the Great Pyramid of Giza is not as perfect as once believed. Results of testing showed that its base was built lopsided.

According to LiveScience, the builders of the Great Pyramid made a small mistake while constructing it. The new research reveals that the west side of the pyramid is slightly longer than the east side. It means that the long lasting myth about the perfection of this construction is not true. Dash and Lehner detected the small flaw in a new measuring project carried out with the support of Glen Dash Research Foundation and Ancient Egypt Research Associates (AERA). Mapping and excavating the Giza plateau by AERA took about 30 years.

As Glen Dash wrote in his report:

''Originally, the Great Pyramid was clad in more than 21 acres of hard, white casing stones that the Egyptians had hauled over from quarries at Tura across the Nile. Most of those casing stones were removed centuries ago for building material, leaving the pyramid as we see it today, without most of its original shell. The photo below was taken along the pyramid’s north side. In it, we see some of the pyramid’s few remaining casing stones still in place. These sit on a platform that originally extended out 39 to 47 centimeters (15–19 inches) beyond the outer, lower edge (the “foot”) of the casing. Behind the casing stones in the photo we can see the rougher masonry that makes up the bulk of the pyramid as it stands today.''

Researchers took measurements of the Great Pyramid's edges and platform, showing what one of the corners may have looked like when built. Researchers noticed a "corner socket," or a cutting in the rock, whose purpose remains unclear. Credit: Image courtesy of Glen DashLehner undertook research to determine the lengths of the original pyramid sides. His team looked for surviving casing stones situated at the foot of the pyramid's platform, and which would have formed the pyramid's original casing baseline. They found 84 points along 155 meters (508 feet) of the original edges of the pyramid, which were marked on a grid system. It was used for mapping all of the features on the Giza Plateau. The obtained data was then processed to receive the most precise outline of the Great Pyramid, which allowed the projection of the original lengths of the pyramid's base.

Researchers took measurements of the Great Pyramid's edges and platform, showing what one of the corners may have looked like when built. Researchers noticed a "corner socket," or a cutting in the rock, whose purpose remains unclear. Credit: Image courtesy of Glen DashLehner undertook research to determine the lengths of the original pyramid sides. His team looked for surviving casing stones situated at the foot of the pyramid's platform, and which would have formed the pyramid's original casing baseline. They found 84 points along 155 meters (508 feet) of the original edges of the pyramid, which were marked on a grid system. It was used for mapping all of the features on the Giza Plateau. The obtained data was then processed to receive the most precise outline of the Great Pyramid, which allowed the projection of the original lengths of the pyramid's base. The Casing Stones can be seen here at the base of the pyramid (

Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library / Flickr

)The results surprised the researchers, who proved that the pyramid originally measured between 230.3 and 230.4 meters (755.6 and 755.8 feet), while the west side of the pyramid originally measured somewhere between 230.4 to 230.4 meters (755.8 and 756.0 feet). It means that the west side was 5.55 inches (14.1 centimeters) longer than the east side. The researchers claimed that the previous measurements of the Great Pyramid were not exactly correct, and the error in construction comes from ancient times.

The Casing Stones can be seen here at the base of the pyramid (

Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library / Flickr

)The results surprised the researchers, who proved that the pyramid originally measured between 230.3 and 230.4 meters (755.6 and 755.8 feet), while the west side of the pyramid originally measured somewhere between 230.4 to 230.4 meters (755.8 and 756.0 feet). It means that the west side was 5.55 inches (14.1 centimeters) longer than the east side. The researchers claimed that the previous measurements of the Great Pyramid were not exactly correct, and the error in construction comes from ancient times.According to Dash, the ancient Egyptians laid out the pyramid on a grid. The north-south meridian of the pyramid runs 3 minutes 54 seconds west of due north while its east-west axis runs 3 minutes 51 seconds north of due east. Moreover, the east-west meridian runs through the center of the temple built on the east side of the pyramid too. The measurements by Dash and Lehner prove that the Great Pyramid is oriented slightly away from the cardinal directions. The analysis of the data gathered by the team led by Dash and Lehner will be continued.

In January 2014, April Holloway from Ancient Origins reported about a different discovery of Mark Lehner. His team made some new discoveries ''including the remains of a bustling port, as well as barracks for sailors or military troops near the Giza pyramids. The findings shed new light on what life was like in the region thousands of years ago.

Archaeologist Mark Lehner, director of Ancient Egypt Research Associates, has said that the discoveries suggest Giza was a thriving port, at least 4,500 years ago. Lehner's team discovered a basin, which may be an extension of a harbour, near the Khentkawes town just 1 kilometre from the nearest Nile River channel.

"Giza was the central port then for three generations, Khufu, Khafre, Menkaure," said Lehner, referring to the three pharaohs who built pyramids at Giza.

Archaeologists also discovered a series of long buildings, called ‘galleries’, which they believe were used as barracks, either for sailors or for soldiers. The buildings were about 7 metres high and 35 metres long and could have held about 40 troops in each one. These troops may have been participating in voyages from the port to the Levant, or soldiers who may have been used for guarding kings and queens while at Giza.''

Top image: The Great Pyramid of Egypt. Source: BigStockPhoto

By Natalia Klimzcak

Published on June 30, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - St Marcellinus elected Pope

June 30

296 St Marcellinus began his reign as Catholic Pope. The violent persecution of Roman Emperor Diocletian dominated his papacy. Also the papal archives were seized and destroyed, but the famous Cemetery of Calixtus was saved by the Christians when they blocked its entrance.

296 St Marcellinus began his reign as Catholic Pope. The violent persecution of Roman Emperor Diocletian dominated his papacy. Also the papal archives were seized and destroyed, but the famous Cemetery of Calixtus was saved by the Christians when they blocked its entrance.

Published on June 30, 2016 02:00

June 29, 2016

Richard the Lionheart: King of war

History Extra

Richard the Lionheart (right) demonstrated his military acumen during clashes with the French king Philip Augustus at the key strategic stronghold of Gisors in the 1190s. © Bridgeman

Richard the Lionheart (right) demonstrated his military acumen during clashes with the French king Philip Augustus at the key strategic stronghold of Gisors in the 1190s. © Bridgeman

On 25 March 1194, Richard I, the Lionheart, laid siege to Nottingham Castle. Intent upon reasserting his authority over England, the king directed the full force of his military genius and martial resources against this supposedly impregnable, rebel-held fortress.

Eleven days earlier, Richard had landed at Sandwich in Kent, setting foot on English soil for the first time in more than four years. During his prolonged absence – first waging a gruelling crusade in the Holy Land, then enduring imprisonment at the hands of political rivals in Austria and Germany – the Lionheart’s devious younger brother, John, had sought to seize power. Richard thus returned to a realm threatened by insurrection and, though John himself soon scuttled across the Channel, Nottingham remained an outpost of those championing his dubious cause.

King Richard I fell upon the stronghold with chilling efficiency. He arrived at the head of a sizeable military force, and possessed the requisite tools to crack Nottingham’s stout defences, having summoned siege machines and stone-throwing trebuchets from Leicester, 22 carpenters from Northampton, and his master engineer, Urric, from London. The castle’s garrison offered stern resistance, but on the first day of fighting the outer battlements fell. As had become his custom, Richard threw himself into the fray wearing only light mail armour and an iron cap, but was protected from a rain of arrows and crossbow bolts by a number of heavy shields borne by his bodyguards. By evening, we are told, many of the defenders were left “wounded and crushed” and a number of prisoners had been taken.

Having made a clear statement of intent, the Lionheart sent messengers to the garrison in the morning, instructing them to capitulate to their rightful king. At first they refused, apparently unconvinced that Richard had indeed returned. In response, the Lionheart deployed his trebuchets, then ordered gibbets to be raised and hanged a number of his captives in full sight of the fortress. Surrender followed shortly thereafter. Accounts vary as to the treatment subsequently meted out to the rebels: one chronicler maintained that they were spared by the “compassionate” king because he was “so gentle and full of mercy”, but other sources make it clear that at least two of John’s hated lackeys met their deaths soon after (one being imprisoned and starved, the other flayed alive).

With this victory Richard reaffirmed the potent legitimacy of his kingship, and support for John’s cause in England collapsed. The work of repairing the grave damage inflicted by John’s machinations upon his family’s extensive continental lands would take years – the majority of Richard’s remaining life in fact – but the Lionhearted monarch had returned to the west in spectacular fashion. Few could doubt that he was now the warrior-king par excellence; a fearsome opponent, unrivalled among the crowned monarchs of Europe.

Rex bellicosusRichard I’s skills as a warrior and a general have long been recognised, though, for much of the 20th century, it was his supposedly intemperate and bloodthirsty brutality that was emphasised, with one scholar describing him as a “peerless killing machine”. In recent decades a strong case has been made for the Lionheart’s more clinical mastery of the science of medieval warfare, and today he is often portrayed as England’s ‘rex bellicosus’ (warlike king).

Current assessments of Richard’s military achievements generally present his early years as Duke of Aquitaine (from 1172) as the decisive and formative phase in his development as a commander. Having acquired and honed his skills, it is argued, the Lionheart was perfectly placed to make his mark on the Third Crusade, waging a holy war to recover Palestine from the Muslim sultan Saladin. The contest for control of Jerusalem between these two titans of medieval history is presented as the high point of Richard I’s martial career – the moment at which he forged his legend.

However, this approach understates some issues, while overplaying others. He embarked upon the crusade on 4 July 1190 as a recently crowned and relatively untested king. Years of intermittent campaigning had given him a solid grounding in the business of war – particularly in the gritty realities of raiding and siege-craft – but to begin with at least, no one would have expected Richard to lead in the holy war. That role naturally fell to Emperor Frederick Barbarossa of Germany, Europe’s elder statesmen and veteran campaigner, and it was only Barbarossa’s unfortunate death through drowning en route to the Levant that opened the door for the Lionheart.

Arguably, the extent and significance of Richard’s achievements in the Holy Land also have been exaggerated. True, he brought the crusader siege of Acre to a swift and successful conclusion in July 1191, but he did so only in alliance with his sometime-rival King Philip Augustus of France (of the Capetian dynasty). The victory over Saladin’s forces later that year at the battle of Arsuf, on 7 September, appears on closer inspection to have been an unplanned and inconclusive encounter, while Richard’s decision to twice advance to within 12 miles of Jerusalem (only to retreat on both occasions without mounting an assault) suggests that he had failed to grasp, much less harness, the distinctive devotional impulse that drove crusading armies.

A manuscript thought to depict Richard I fighting Saladin during the Third Crusade, where the Lionheart honed the military skills for which he became famous. © AKG Images

This is not to suggest that Richard’s expedition should be regarded as a failure, nor to deny that his campaign was punctuated by moments of inspired generalship – most notably in leading his army on a fighting march through Muslim-held territory between Acre and Jaffa. Rather, it is to point out that the Lionheart was still sharpening his skills in Palestine. The Third Crusade ended in stalemate in September 1192, but it was in the fires of this holy war, as Richard and Saladin fought one another to a standstill, that the English king tempered his martial genius.

He returned to the west having acquired a new depth of experience and insight, and proved only too capable of putting the lessons learned in the Levant to good use as he strove first to subdue England, and then to reclaim the likes of Normandy and Anjou from Philip of France. It is this period, between 1194 and 1198, which rightly should be recognised as the pinnacle of Richard I’s military career.

By the time he reached England in March 1194, the 36-year-old Richard had matured into an exceptionally well-rounded commander. As a meticulous logician and a cool-headed, visionary strategist, the Lionheart could out-think his enemy; but he also loved frontline combat and possessed an exuberant self-confidence and inspirational charisma, allied to a grim, but arguably necessary, streak of ruthlessness.

All of these qualities were immediately apparent when Richard marched on rebel-held Nottingham. This veteran of the siege of Acre – one of the hardest-fought investments of the Middle Ages – understood the value of careful planning, the decisive capability of heavy siege machinery and the morale-sapping impact of calculated violence. Though one contemporary claimed Nottingham Castle was “so well fortified by nature and artifice” that it seemed “unconquerable”, Richard brought its garrison to the point of surrender in less than two days. Other striking successes in siege warfare followed, not least when the Lionheart captured the mighty fortress of Loches (in Touraine) in just three hours through a blistering frontal assault.

Sparring with the enemyWhile campaigning on the continent to recover Angevin territory from Philip Augustus, Richard also demonstrated a remarkably acute appreciation of the precepts governing military manoeuvres and engagements. During the crusade he had sparred with Saladin’s forces on numerous occasions, through fighting marches, exploratory raids and in the course of the first, incremental advance inland towards Jerusalem conducted in the autumn of 1191.

This hard-won familiarity with the subtleties of troop movements and martial incursion served the Lionheart well when, in the early summer of 1194, Philip Augustus advanced west towards the town of Vendôme (on the border between the Angevin realm and Capetian territory) and began to threaten the whole of the Loire Valley.

The seal of Richard the Lionheart depicts the ultimate medieval warrior-king, who eagerly threw himself into the heat of battle. © Bridgeman

Richard responded by marching into the region in early July. Vendôme itself was not fortified, so the Angevin king threw up a defensive camp in front of the town. The two armies, seemingly well-matched in numerical terms, were now separated by only a matter of miles. Though Philip initially remained blissfully unaware, from the moment that the Lionheart took up a position before Vendôme, the Capetians (French) were in grave danger. Should the French king attempt to initiate a frontal assault on the Angevin encampment, he would have to lead his troops south-west down the road to Vendôme, leaving the Capetian host exposed to flanking and encircling manoeuvres. However, any move by the French to retreat from the frontline would be an equally risky proposition, as they would be prone to attack from the rear and might easily be routed.

At first, King Philip sought to intimidate Richard, dispatching an envoy on 3 July to warn that a French offensive would soon be launched. Displaying a disconcerting confidence, the Lionheart apparently replied that he would happily await the Capetians’ arrival, adding that, should they not appear, he would pay them a visit in the morning. Unsettled by this brazen retort, Philip wavered over his next step.

When the Angevins initiated an advance the following day, the French king’s nerve broke and he ordered a hurried withdrawal north-east, along the road to Fréteval (12 miles from Vendôme). Though eager to harry his fleeing opponent, Richard shrewdly recognised that he could ill-afford a headlong pursuit that might leave his own troops in disarray, perilously exposed to counterattack. The Lionheart therefore placed one of his most trusted field lieutenants, William Marshal, in command of a reserve force, with orders to shadow the main advance, yet hold back from the hunt itself and thus be ready to counter any lingering Capetian resistance.

Having readied his men, Richard began his chase around midday on 4 July. Towards dusk, Richard caught up with the French rear guard and wagon train near Fréteval, and as the Angevins fell on the broken Capetian ranks, hundreds of routing enemy troops were slain or taken prisoner. All manner of plunder was seized, from “pavilions, all kinds of tents, cloth of scarlet and silk, plate and coin” according to one chronicler, to “horses, palfreys, pack-horses, sumptuous garments and money”. Many of Philip Augustus’s personal possessions were appropriated, including a portion of the Capetian royal archives. It was a desperately humiliating defeat.

Richard hunted the fleeing French king through the night, using a string of horses to speed his pursuit, but when Philip pulled off the road to hide in a small church, Richard rode by. It was a shockingly narrow escape for the Capetian. The Angevins returned to Vendôme near midnight, laden with booty and leading a long line of prisoners.

The power of a castleBy the end of 1198, after long years of tireless campaigning and adept diplomacy, Richard had recovered most of the Angevin dynasty’s territorial holdings on the continent. One crucial step in the process of restoration was the battle for dominion over the Norman Vexin – the long-contested border zone between the duchy of Normandy and the Capetian-held Ile-de-France. Philip Augustus had seized this region in 1193-94, while Richard still remained in captivity, occupying a number of castles, including the stronghold at Gisors. Long regarded as the linchpin of the entire Vexin, this fortress was all-but impregnable. It boasted a fearsome inner-keep enclosed within an imposing circuit of outer-battlements and, even more importantly, could rely upon swift reinforcement by French troops should it ever be subjected to enemy assault.

The Lionheart was uniquely qualified to attempt the Vexin’s reconquest. In the Holy Land, he had painstakingly developed a line of defensible fortifications along the route linking Jaffa and Jerusalem. Later, he dedicated himself to re-establishing the battlements at Ascalon because the port was critical to the balance of power between Palestine and Egypt. Richard might already have possessed a fairly shrewd appreciation of a castle’s use and value before the crusade, but by the time he returned to Europe there can have been few commanders with a better grasp of this dimension of medieval warfare.

Drawing upon this expertise, Richard immediately recognised that, in practical terms, Gisors was invulnerable to direct attack. As a result, he formulated an inspired, two-fold strategy, designed to neutralise Gisors and reassert Angevin influence over the Vexin. First, he built a vast new military complex on the Seine at Les Andelys (on the Vexin’s western edge) that included a fortified island, a dock that made the site accessible to shipping from England and a looming fortress christened ‘Chateau Gaillard’ – the ‘Castle of Impudence’ or ‘Cheeky-Castle’. Built in just two years, 1196–98, the project cost an incredible £12,000, far more than Richard spent on fortifications in all of England over the course of his entire reign.

Richard’s Chateau Gaillard (meaning ‘Castle of Impudence’) allowed him to neutralise his enemies in the Norman Vexin. © Rex Features

Les Andelys protected the approaches to the ducal capital of Rouen, but more importantly it also functioned as a staging post for offensive incursions into the Vexin. For the first time, it allowed large numbers of Angevin troops to be billeted on the fringe of this border zone in relative safety and the Lionheart set about using these forces to dominate the surrounding region. Though the Capetians retained control of Gisors, alongside a number of other strongholds in the Vexin, their emasculated garrisons were virtually unable to venture beyond their gates, because the Angevins based out of Les Andelys were constantly ranging across the landscape.

One chronicler observed that the French were “so pinned down [in their] castles that they could not take anything outside”, and troops in Gisors itself were unable even to draw water from their local spring. By these steps, King Richard reaffirmed Angevin dominance in northern France, shifting the balance of power back in his favour.

In the end, Richard’s penchant for siege warfare and frontline skirmishing cost him his life. One of the greatest warrior-kings of the Middle Ages was cut down in 1199 by a crossbow bolt while investing an insignificant Aquitanean fortress. The Lionheart’s death, aged just 41, seemed to contemporaries, as it does today, a shocking and pointless waste. Nonetheless, he was the foremost military commander of his generation – a rex bellicosus whose martial gifts were refined in the Holy Land.

Crusader to war king8 September 1157

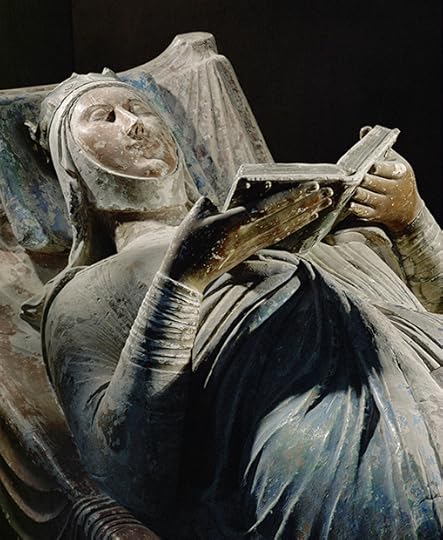

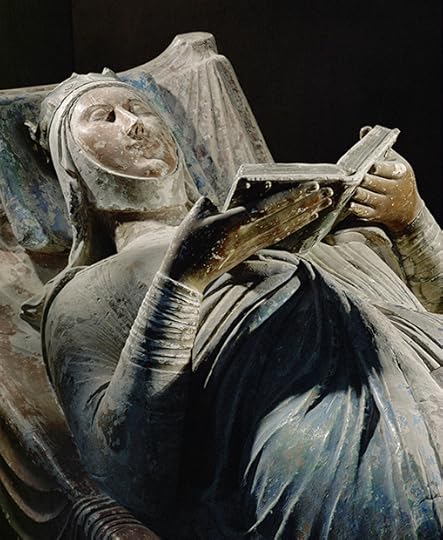

Richard is born, son of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine (below), founders of the Angevin dynasty

© AKG Images

June 1172

Invested as Duke of Aquitaine in the abbey church of St Hilary in Poitiers

11 June 1183

His elder brother dies. Richard becomes heir to the English crown and Angevin realm (including Normandy and Anjou

Autumn 1187

Saladin reconquers Jerusalem. Richard is the first nobleman north of the Alps to take the cross for the Third Crusade

3 September 1189

Having rebelled against his father Henry’s authority and hounded the old king to his death, Richard is crowned king

4 July 1190

Sets out on crusade to the Holy Land, leaving younger brother, John, in Europe

Summer 1191

Richard seizes Acre from Saladin’s forces. He marches to Jaffa, defeating the Muslim army at Arsuf en route

2 September 1192

After abortive attempts on Jerusalem, Richard agrees peace with Saladin

December 1192

Travelling home, Richard is seized by Leopold of Austria, then held by Henry VI of Germany until 1194

26 March 1194

Richard takes Nottingham Castle. His brother John’s cause in England collapses

1196–98

Richard spends £12,000 on ‘Chateau Gaillard’ which helps him reassert Angevin dominance in northern France

6 April 1199

Richard dies during the siege of Chalus

Dr Thomas Asbridge is reader in medieval history at Queen Mary, University of London. He is currently writing a new biography of Richard I for the Penguin Monarchs series.

Richard the Lionheart (right) demonstrated his military acumen during clashes with the French king Philip Augustus at the key strategic stronghold of Gisors in the 1190s. © Bridgeman

Richard the Lionheart (right) demonstrated his military acumen during clashes with the French king Philip Augustus at the key strategic stronghold of Gisors in the 1190s. © Bridgeman On 25 March 1194, Richard I, the Lionheart, laid siege to Nottingham Castle. Intent upon reasserting his authority over England, the king directed the full force of his military genius and martial resources against this supposedly impregnable, rebel-held fortress.

Eleven days earlier, Richard had landed at Sandwich in Kent, setting foot on English soil for the first time in more than four years. During his prolonged absence – first waging a gruelling crusade in the Holy Land, then enduring imprisonment at the hands of political rivals in Austria and Germany – the Lionheart’s devious younger brother, John, had sought to seize power. Richard thus returned to a realm threatened by insurrection and, though John himself soon scuttled across the Channel, Nottingham remained an outpost of those championing his dubious cause.

King Richard I fell upon the stronghold with chilling efficiency. He arrived at the head of a sizeable military force, and possessed the requisite tools to crack Nottingham’s stout defences, having summoned siege machines and stone-throwing trebuchets from Leicester, 22 carpenters from Northampton, and his master engineer, Urric, from London. The castle’s garrison offered stern resistance, but on the first day of fighting the outer battlements fell. As had become his custom, Richard threw himself into the fray wearing only light mail armour and an iron cap, but was protected from a rain of arrows and crossbow bolts by a number of heavy shields borne by his bodyguards. By evening, we are told, many of the defenders were left “wounded and crushed” and a number of prisoners had been taken.

Having made a clear statement of intent, the Lionheart sent messengers to the garrison in the morning, instructing them to capitulate to their rightful king. At first they refused, apparently unconvinced that Richard had indeed returned. In response, the Lionheart deployed his trebuchets, then ordered gibbets to be raised and hanged a number of his captives in full sight of the fortress. Surrender followed shortly thereafter. Accounts vary as to the treatment subsequently meted out to the rebels: one chronicler maintained that they were spared by the “compassionate” king because he was “so gentle and full of mercy”, but other sources make it clear that at least two of John’s hated lackeys met their deaths soon after (one being imprisoned and starved, the other flayed alive).

With this victory Richard reaffirmed the potent legitimacy of his kingship, and support for John’s cause in England collapsed. The work of repairing the grave damage inflicted by John’s machinations upon his family’s extensive continental lands would take years – the majority of Richard’s remaining life in fact – but the Lionhearted monarch had returned to the west in spectacular fashion. Few could doubt that he was now the warrior-king par excellence; a fearsome opponent, unrivalled among the crowned monarchs of Europe.

Rex bellicosusRichard I’s skills as a warrior and a general have long been recognised, though, for much of the 20th century, it was his supposedly intemperate and bloodthirsty brutality that was emphasised, with one scholar describing him as a “peerless killing machine”. In recent decades a strong case has been made for the Lionheart’s more clinical mastery of the science of medieval warfare, and today he is often portrayed as England’s ‘rex bellicosus’ (warlike king).

Current assessments of Richard’s military achievements generally present his early years as Duke of Aquitaine (from 1172) as the decisive and formative phase in his development as a commander. Having acquired and honed his skills, it is argued, the Lionheart was perfectly placed to make his mark on the Third Crusade, waging a holy war to recover Palestine from the Muslim sultan Saladin. The contest for control of Jerusalem between these two titans of medieval history is presented as the high point of Richard I’s martial career – the moment at which he forged his legend.

However, this approach understates some issues, while overplaying others. He embarked upon the crusade on 4 July 1190 as a recently crowned and relatively untested king. Years of intermittent campaigning had given him a solid grounding in the business of war – particularly in the gritty realities of raiding and siege-craft – but to begin with at least, no one would have expected Richard to lead in the holy war. That role naturally fell to Emperor Frederick Barbarossa of Germany, Europe’s elder statesmen and veteran campaigner, and it was only Barbarossa’s unfortunate death through drowning en route to the Levant that opened the door for the Lionheart.

Arguably, the extent and significance of Richard’s achievements in the Holy Land also have been exaggerated. True, he brought the crusader siege of Acre to a swift and successful conclusion in July 1191, but he did so only in alliance with his sometime-rival King Philip Augustus of France (of the Capetian dynasty). The victory over Saladin’s forces later that year at the battle of Arsuf, on 7 September, appears on closer inspection to have been an unplanned and inconclusive encounter, while Richard’s decision to twice advance to within 12 miles of Jerusalem (only to retreat on both occasions without mounting an assault) suggests that he had failed to grasp, much less harness, the distinctive devotional impulse that drove crusading armies.

A manuscript thought to depict Richard I fighting Saladin during the Third Crusade, where the Lionheart honed the military skills for which he became famous. © AKG Images

This is not to suggest that Richard’s expedition should be regarded as a failure, nor to deny that his campaign was punctuated by moments of inspired generalship – most notably in leading his army on a fighting march through Muslim-held territory between Acre and Jaffa. Rather, it is to point out that the Lionheart was still sharpening his skills in Palestine. The Third Crusade ended in stalemate in September 1192, but it was in the fires of this holy war, as Richard and Saladin fought one another to a standstill, that the English king tempered his martial genius.

He returned to the west having acquired a new depth of experience and insight, and proved only too capable of putting the lessons learned in the Levant to good use as he strove first to subdue England, and then to reclaim the likes of Normandy and Anjou from Philip of France. It is this period, between 1194 and 1198, which rightly should be recognised as the pinnacle of Richard I’s military career.

By the time he reached England in March 1194, the 36-year-old Richard had matured into an exceptionally well-rounded commander. As a meticulous logician and a cool-headed, visionary strategist, the Lionheart could out-think his enemy; but he also loved frontline combat and possessed an exuberant self-confidence and inspirational charisma, allied to a grim, but arguably necessary, streak of ruthlessness.

All of these qualities were immediately apparent when Richard marched on rebel-held Nottingham. This veteran of the siege of Acre – one of the hardest-fought investments of the Middle Ages – understood the value of careful planning, the decisive capability of heavy siege machinery and the morale-sapping impact of calculated violence. Though one contemporary claimed Nottingham Castle was “so well fortified by nature and artifice” that it seemed “unconquerable”, Richard brought its garrison to the point of surrender in less than two days. Other striking successes in siege warfare followed, not least when the Lionheart captured the mighty fortress of Loches (in Touraine) in just three hours through a blistering frontal assault.

Sparring with the enemyWhile campaigning on the continent to recover Angevin territory from Philip Augustus, Richard also demonstrated a remarkably acute appreciation of the precepts governing military manoeuvres and engagements. During the crusade he had sparred with Saladin’s forces on numerous occasions, through fighting marches, exploratory raids and in the course of the first, incremental advance inland towards Jerusalem conducted in the autumn of 1191.

This hard-won familiarity with the subtleties of troop movements and martial incursion served the Lionheart well when, in the early summer of 1194, Philip Augustus advanced west towards the town of Vendôme (on the border between the Angevin realm and Capetian territory) and began to threaten the whole of the Loire Valley.

The seal of Richard the Lionheart depicts the ultimate medieval warrior-king, who eagerly threw himself into the heat of battle. © Bridgeman

Richard responded by marching into the region in early July. Vendôme itself was not fortified, so the Angevin king threw up a defensive camp in front of the town. The two armies, seemingly well-matched in numerical terms, were now separated by only a matter of miles. Though Philip initially remained blissfully unaware, from the moment that the Lionheart took up a position before Vendôme, the Capetians (French) were in grave danger. Should the French king attempt to initiate a frontal assault on the Angevin encampment, he would have to lead his troops south-west down the road to Vendôme, leaving the Capetian host exposed to flanking and encircling manoeuvres. However, any move by the French to retreat from the frontline would be an equally risky proposition, as they would be prone to attack from the rear and might easily be routed.

At first, King Philip sought to intimidate Richard, dispatching an envoy on 3 July to warn that a French offensive would soon be launched. Displaying a disconcerting confidence, the Lionheart apparently replied that he would happily await the Capetians’ arrival, adding that, should they not appear, he would pay them a visit in the morning. Unsettled by this brazen retort, Philip wavered over his next step.

When the Angevins initiated an advance the following day, the French king’s nerve broke and he ordered a hurried withdrawal north-east, along the road to Fréteval (12 miles from Vendôme). Though eager to harry his fleeing opponent, Richard shrewdly recognised that he could ill-afford a headlong pursuit that might leave his own troops in disarray, perilously exposed to counterattack. The Lionheart therefore placed one of his most trusted field lieutenants, William Marshal, in command of a reserve force, with orders to shadow the main advance, yet hold back from the hunt itself and thus be ready to counter any lingering Capetian resistance.

Having readied his men, Richard began his chase around midday on 4 July. Towards dusk, Richard caught up with the French rear guard and wagon train near Fréteval, and as the Angevins fell on the broken Capetian ranks, hundreds of routing enemy troops were slain or taken prisoner. All manner of plunder was seized, from “pavilions, all kinds of tents, cloth of scarlet and silk, plate and coin” according to one chronicler, to “horses, palfreys, pack-horses, sumptuous garments and money”. Many of Philip Augustus’s personal possessions were appropriated, including a portion of the Capetian royal archives. It was a desperately humiliating defeat.

Richard hunted the fleeing French king through the night, using a string of horses to speed his pursuit, but when Philip pulled off the road to hide in a small church, Richard rode by. It was a shockingly narrow escape for the Capetian. The Angevins returned to Vendôme near midnight, laden with booty and leading a long line of prisoners.

The power of a castleBy the end of 1198, after long years of tireless campaigning and adept diplomacy, Richard had recovered most of the Angevin dynasty’s territorial holdings on the continent. One crucial step in the process of restoration was the battle for dominion over the Norman Vexin – the long-contested border zone between the duchy of Normandy and the Capetian-held Ile-de-France. Philip Augustus had seized this region in 1193-94, while Richard still remained in captivity, occupying a number of castles, including the stronghold at Gisors. Long regarded as the linchpin of the entire Vexin, this fortress was all-but impregnable. It boasted a fearsome inner-keep enclosed within an imposing circuit of outer-battlements and, even more importantly, could rely upon swift reinforcement by French troops should it ever be subjected to enemy assault.

The Lionheart was uniquely qualified to attempt the Vexin’s reconquest. In the Holy Land, he had painstakingly developed a line of defensible fortifications along the route linking Jaffa and Jerusalem. Later, he dedicated himself to re-establishing the battlements at Ascalon because the port was critical to the balance of power between Palestine and Egypt. Richard might already have possessed a fairly shrewd appreciation of a castle’s use and value before the crusade, but by the time he returned to Europe there can have been few commanders with a better grasp of this dimension of medieval warfare.

Drawing upon this expertise, Richard immediately recognised that, in practical terms, Gisors was invulnerable to direct attack. As a result, he formulated an inspired, two-fold strategy, designed to neutralise Gisors and reassert Angevin influence over the Vexin. First, he built a vast new military complex on the Seine at Les Andelys (on the Vexin’s western edge) that included a fortified island, a dock that made the site accessible to shipping from England and a looming fortress christened ‘Chateau Gaillard’ – the ‘Castle of Impudence’ or ‘Cheeky-Castle’. Built in just two years, 1196–98, the project cost an incredible £12,000, far more than Richard spent on fortifications in all of England over the course of his entire reign.

Richard’s Chateau Gaillard (meaning ‘Castle of Impudence’) allowed him to neutralise his enemies in the Norman Vexin. © Rex Features

Les Andelys protected the approaches to the ducal capital of Rouen, but more importantly it also functioned as a staging post for offensive incursions into the Vexin. For the first time, it allowed large numbers of Angevin troops to be billeted on the fringe of this border zone in relative safety and the Lionheart set about using these forces to dominate the surrounding region. Though the Capetians retained control of Gisors, alongside a number of other strongholds in the Vexin, their emasculated garrisons were virtually unable to venture beyond their gates, because the Angevins based out of Les Andelys were constantly ranging across the landscape.

One chronicler observed that the French were “so pinned down [in their] castles that they could not take anything outside”, and troops in Gisors itself were unable even to draw water from their local spring. By these steps, King Richard reaffirmed Angevin dominance in northern France, shifting the balance of power back in his favour.

In the end, Richard’s penchant for siege warfare and frontline skirmishing cost him his life. One of the greatest warrior-kings of the Middle Ages was cut down in 1199 by a crossbow bolt while investing an insignificant Aquitanean fortress. The Lionheart’s death, aged just 41, seemed to contemporaries, as it does today, a shocking and pointless waste. Nonetheless, he was the foremost military commander of his generation – a rex bellicosus whose martial gifts were refined in the Holy Land.

Crusader to war king8 September 1157

Richard is born, son of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine (below), founders of the Angevin dynasty

© AKG Images

June 1172

Invested as Duke of Aquitaine in the abbey church of St Hilary in Poitiers

11 June 1183

His elder brother dies. Richard becomes heir to the English crown and Angevin realm (including Normandy and Anjou

Autumn 1187

Saladin reconquers Jerusalem. Richard is the first nobleman north of the Alps to take the cross for the Third Crusade

3 September 1189

Having rebelled against his father Henry’s authority and hounded the old king to his death, Richard is crowned king

4 July 1190

Sets out on crusade to the Holy Land, leaving younger brother, John, in Europe

Summer 1191

Richard seizes Acre from Saladin’s forces. He marches to Jaffa, defeating the Muslim army at Arsuf en route

2 September 1192

After abortive attempts on Jerusalem, Richard agrees peace with Saladin

December 1192

Travelling home, Richard is seized by Leopold of Austria, then held by Henry VI of Germany until 1194

26 March 1194

Richard takes Nottingham Castle. His brother John’s cause in England collapses

1196–98

Richard spends £12,000 on ‘Chateau Gaillard’ which helps him reassert Angevin dominance in northern France

6 April 1199

Richard dies during the siege of Chalus

Dr Thomas Asbridge is reader in medieval history at Queen Mary, University of London. He is currently writing a new biography of Richard I for the Penguin Monarchs series.

Published on June 29, 2016 03:00

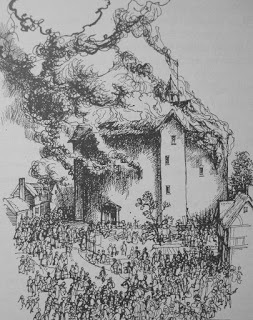

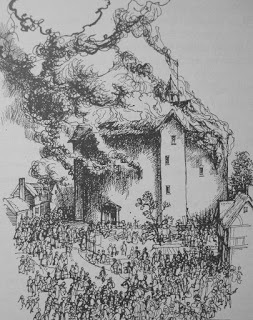

History Trivia - London's Globe Theatre burns

June 29

1613 London's Globe Theatre burns down when a theatrical canon is fired during the play 'All Is True'.

1613 London's Globe Theatre burns down when a theatrical canon is fired during the play 'All Is True'.

Published on June 29, 2016 02:00

June 28, 2016

10 facts about Stonehenge

History Extra

Built in several stages, Stonehenge began about 5,000 years ago as a simple earthwork enclosure where prehistoric people buried their cremated dead. The stone circle was erected in the centre of the monument in the late Neolithic period, around 2500 BC

• Two types of stone are used at Stonehenge: the larger sarsens, and the smaller bluestones. There are 83 stones in total

• There were originally only two entrances to the enclosure, English Heritage explains – a wide one to the north east, and a smaller one on the southern side. Today there are many more gaps – this is mainly the result of later tracks that once crossed the monument

• A circle of 56 pits, known as the Aubrey Holes (named after John Aubrey, who identified them in 1666), sits inside the enclosure. Its purpose remains unknown, but some believe the pits once held stones or posts

• The stone settings at Stonehenge were built at a time of “great change in prehistory,” says English Heritage, “just as new styles of ‘Beaker’ pottery and the knowledge of metalworking, together with a transition to the burial of individuals with grave goods, were arriving from Europe. From about 2400 BC, well furnished Beaker graves such as that of the Amesbury Arche are found nearby”

• Roman pottery, stone, metal items and coins have been found during various excavations at Stonehenge. An English Heritage report in 2010 said that considerably fewer medieval artefacts have been discovered, which suggests the site was used more sporadically during the period

• Stonehenge has a long relationship with astronomers, the report explains. In 1720, Dr Halley used magnetic deviation and the position of the rising sun to estimate the age of Stonehenge. He concluded the date was 460 BC. And, in 1771, John Smith mused that the estimated total of 30 sarsen stones multiplied by 12 astrological signs equalled 360 days of the year, while the inner circle represented the lunar month

• The first mention of Stonehenge – or ‘Stanenges’ – appears in the archaeological study of Henry of Huntingdon in about AD 1130, and that of Geoffrey of Monmouth six years later. In 1200 and 1250 it appeared as ‘Stanhenge’ and ‘Stonhenge’; as ‘Stonheng’ in 1297, and ‘the stone hengles’ in 1470. It became known as ‘Stonehenge’ in 1610, says English Heritage

• In the 1880s, after carrying out some of the first scientifically recorded excavations at the site, Charles Darwin concluded that earthworms were largely to blame for the Stonehenge stones sinking through the soil

• By the beginning of the 20th century there had been more than 10 recorded excavations, and the site was considered to be in a “sorry state”, says English Heritage – several sarsens were leaning. Consequently the Society of Antiquaries lobbied the site’s owner, Sir Edmond Antrobus, and offered to assist with conservation

To read more about Stonehenge, click here.

Built in several stages, Stonehenge began about 5,000 years ago as a simple earthwork enclosure where prehistoric people buried their cremated dead. The stone circle was erected in the centre of the monument in the late Neolithic period, around 2500 BC

• Two types of stone are used at Stonehenge: the larger sarsens, and the smaller bluestones. There are 83 stones in total

• There were originally only two entrances to the enclosure, English Heritage explains – a wide one to the north east, and a smaller one on the southern side. Today there are many more gaps – this is mainly the result of later tracks that once crossed the monument

• A circle of 56 pits, known as the Aubrey Holes (named after John Aubrey, who identified them in 1666), sits inside the enclosure. Its purpose remains unknown, but some believe the pits once held stones or posts

• The stone settings at Stonehenge were built at a time of “great change in prehistory,” says English Heritage, “just as new styles of ‘Beaker’ pottery and the knowledge of metalworking, together with a transition to the burial of individuals with grave goods, were arriving from Europe. From about 2400 BC, well furnished Beaker graves such as that of the Amesbury Arche are found nearby”

• Roman pottery, stone, metal items and coins have been found during various excavations at Stonehenge. An English Heritage report in 2010 said that considerably fewer medieval artefacts have been discovered, which suggests the site was used more sporadically during the period

• Stonehenge has a long relationship with astronomers, the report explains. In 1720, Dr Halley used magnetic deviation and the position of the rising sun to estimate the age of Stonehenge. He concluded the date was 460 BC. And, in 1771, John Smith mused that the estimated total of 30 sarsen stones multiplied by 12 astrological signs equalled 360 days of the year, while the inner circle represented the lunar month

• The first mention of Stonehenge – or ‘Stanenges’ – appears in the archaeological study of Henry of Huntingdon in about AD 1130, and that of Geoffrey of Monmouth six years later. In 1200 and 1250 it appeared as ‘Stanhenge’ and ‘Stonhenge’; as ‘Stonheng’ in 1297, and ‘the stone hengles’ in 1470. It became known as ‘Stonehenge’ in 1610, says English Heritage

• In the 1880s, after carrying out some of the first scientifically recorded excavations at the site, Charles Darwin concluded that earthworms were largely to blame for the Stonehenge stones sinking through the soil

• By the beginning of the 20th century there had been more than 10 recorded excavations, and the site was considered to be in a “sorry state”, says English Heritage – several sarsens were leaning. Consequently the Society of Antiquaries lobbied the site’s owner, Sir Edmond Antrobus, and offered to assist with conservation

To read more about Stonehenge, click here.

Published on June 28, 2016 03:00

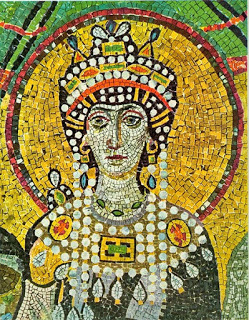

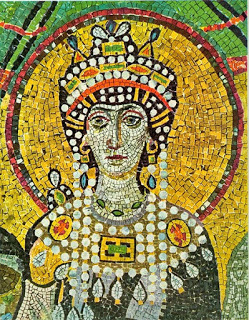

History Trivia - Byzantine Empress Theodora dies

June 28

548 Byzantine Empress Theodora, wife of Emperor Justinian I, and thought to be the most influential and powerful woman in the Roman Empire's history, died.

548 Byzantine Empress Theodora, wife of Emperor Justinian I, and thought to be the most influential and powerful woman in the Roman Empire's history, died.

Published on June 28, 2016 02:00

June 27, 2016

In case you missed it... Top 10 historical Cornish words

History Extra

c1870: the busy fishing port of Newlyn in Penzance, Cornwall. (Photo by Gibson/Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Cornish, or Kernowek – a descendant of the language spoken by the British population before the Anglo-Saxons arrived – has survived and resisted over the centuries.

c1870: the busy fishing port of Newlyn in Penzance, Cornwall. (Photo by Gibson/Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Cornish, or Kernowek – a descendant of the language spoken by the British population before the Anglo-Saxons arrived – has survived and resisted over the centuries.In 1549, during the Reformation, the Act of Uniformity decreed that the Book of Common Prayer in English should be used by everyone in place of Latin worship. This proved so unpopular with the speakers of Cornish that there was a massive uprising – the Prayer Book Rebellion. Thousands of rebels died, striking a massive blow to the already dwindling language.

However, Cornish struggled through until the 19th century when – entirely replaced by English – it was declared a dead language. Famously, the last native speaker of Cornish was Dolly Pentreath of Mousehole, who died in 1777.

As Cornish declined and was replaced with English, the two intermingled to develop a rich Cornish dialect of English. This dialect, while English, has elements of Cornish grammar, and lots of Cornish vocabulary.

In the mid-19th century there was a resurgence of interest in the Cornish Language and dialect, despite the fact it had been in decline some years earlier. In an effort to record and preserve it, several scholars wrote grammars, dictionaries and glossaries.

The language preserved in these books shows a Cornwall that is pragmatic and occasionally bawdy; hardworking, and dependent on the landscape.

Cornish still survives today and is now an official minority language, although it is notably stronger in the older generations. There is a growing number of bilingual native speakers, and Cornish-language books and films are being made.

Let’s look back at some notable 19th-century Cornish dialect words:

EGGY-HOT – Hot beer whisked with eggs and sugar, sometimes flavoured with rum.

TIDDLEYWINKS or KIDDLIWINKS – A pub. Innkeepers would keep smuggled brandy hidden from the law in a kettle. Those in the know would then WINK at the kettle when they wanted some. It’s likely that after an evening’s hard winking at the kettle, it didn’t stay secret for long.

VESTRY – When a baby smiles in its sleep.

EAR-BOSOMS – Glands in the neck. When they’re swollen, you say “my ear-bosoms are down”.

POKEMON – Clumsy. Unrelated to the Japanese POKEMON, which is a contraction of Pocket Monsters.

DUMBLEDORE – A thorn or bramble. This word, which also appears in early modern English meaning a bumblebee, inspired JK Rowling.

BOWLDACIOUS – Brazen or impudent, as in “You bowldacious hussy”.

GOD’S COW – A ladybird. Because what is a ladybird if not a tiny, red, holy cow?

AIRYMOUSE – A bat. A more modern Cornish dialect word for bat is LEATHERWING, which is equally lovely.

NESTLE-BIRD, CHOOGY-PIG and PIGGY-WHIDDEN – The smallest and weakest pig in a litter. The number of words for this demonstrates how important animals were in daily life.

Published on June 27, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - St. Agatho elected Pope

June 27

678 St Agatho began his reign as Catholic Pope. The great event of this pontificate was the Sixth General Council, the Third of Constantinople which extinguished the Monothelite heresy and reunited Constantinople to Rome.

678 St Agatho began his reign as Catholic Pope. The great event of this pontificate was the Sixth General Council, the Third of Constantinople which extinguished the Monothelite heresy and reunited Constantinople to Rome.

Published on June 27, 2016 02:00

June 26, 2016

Prehistoric Calendar Revealed at Stonehenge

Ancient Origins

Summer solstice is fast approaching, and on the 20th June over 20,000 people are expected to gather at the world-famous Stonehenge to celebrate and watch the sun rise above the Heel Stone and shine on the central altar. For those of us in the northern hemisphere, this is a time when the sun's path stops moving northward in the sky, the days stop growing longer and will soon begin to shorten again.

Over 5000 years old, Stonehenge was built in three phases between 3,000 B.C. and 1,600 B.C. Its full purpose remains unknown yet the mystery that surrounds Stonehenge is so enduring and popular that last year over 1.3 million visitors flocked to this ancient monument. There are even several man-made copies of the world-famous heritage site have been built around the world, including an impressive full-scale replica at the Maryhill Museum in Washington, USA.

Painting of the Maryhill replica of Stonehenge (

Michael D Martin / Flickr

)Stonehenge famously aligns to the solstices, but for the rest of the year it seems strange that these ancient builders would not be aware of the current day, or for that matter how many days remained to the next solstice event. However, a new theory has been presented that suggests Stonehenge was used for more than just marking the winter and summer solstices, or as a sacred burial site.

Painting of the Maryhill replica of Stonehenge (

Michael D Martin / Flickr

)Stonehenge famously aligns to the solstices, but for the rest of the year it seems strange that these ancient builders would not be aware of the current day, or for that matter how many days remained to the next solstice event. However, a new theory has been presented that suggests Stonehenge was used for more than just marking the winter and summer solstices, or as a sacred burial site.

Recently, Lloyd Matthews (scale modelling expert based in the UK) and Joan Rankin (a retired historian living in Canada), have made an ambitious attempt to rethink the purpose of Stonehenge. Their conclusion, after three years of extensive and laborious research, is that the entire structure was, in fact, a complex and significant prehistoric calendar that could actually count the individual days in a year. Not only did Stonehenge act as a solar calendar, similar to the western calendar used today, but it also acted as a lunar calendar and was important for a developing agricultural society to successfully plan for the seasons.

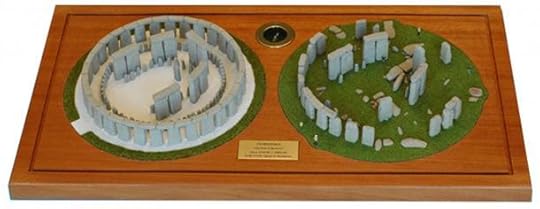

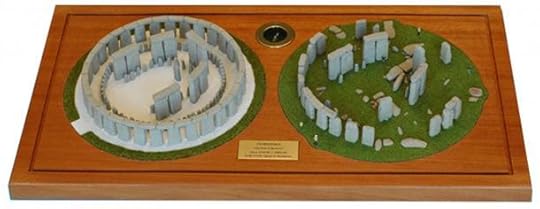

Lloyd Matthews spent 6 years meticulously researching and constructing two scale models of Stonehenge for display at The Maryhill Museum of Art. The models show Stonehenge as it stands today and as it would have originally looked when built.

Lloyd Matthew’s models showing Stonehenge as it stands today and as it would have originally looked. Credit:

Lloyd Matthews

During its construction, Mr Matthews identified three distinct carvings on three of the large stones known as Trilithons (shown below). Curiosity piqued, Mr Matthews approached several experts at the time who were unable to provide an explanation as to what these symbols meant. Dissatisfied with the responses, Mr Matthews decided to continue his research into this ancient puzzle with the help of Joan Rankin, an authority in prehistory.

Lloyd Matthew’s models showing Stonehenge as it stands today and as it would have originally looked. Credit:

Lloyd Matthews

During its construction, Mr Matthews identified three distinct carvings on three of the large stones known as Trilithons (shown below). Curiosity piqued, Mr Matthews approached several experts at the time who were unable to provide an explanation as to what these symbols meant. Dissatisfied with the responses, Mr Matthews decided to continue his research into this ancient puzzle with the help of Joan Rankin, an authority in prehistory.

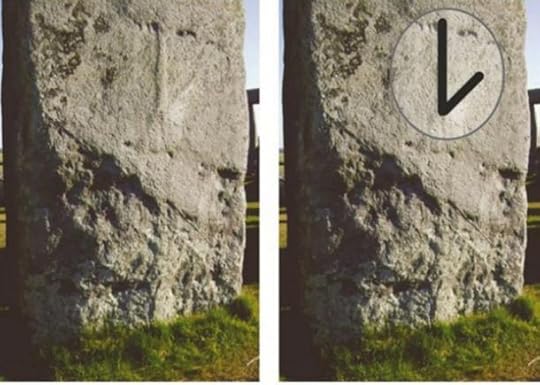

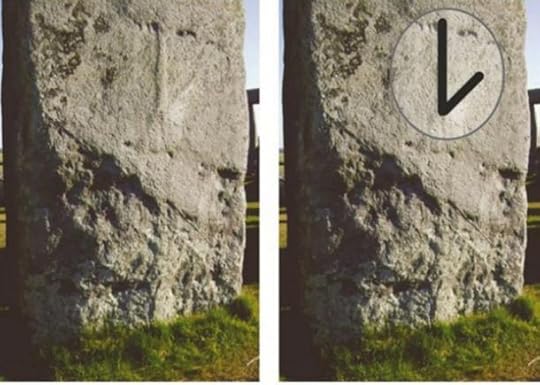

Stone 52 with ‘The Eye’ symbol. From Left: Stone 52 today (Credit: Lloyd Matthews), Replica of Stone 52 (Credit: Lloyd Matthews), Stone 52 in 1867.

Stone 52 with ‘The Eye’ symbol. From Left: Stone 52 today (Credit: Lloyd Matthews), Replica of Stone 52 (Credit: Lloyd Matthews), Stone 52 in 1867.  Stone 53 with ‘The Dividers’ symbol. Credit: Lloyd Matthews

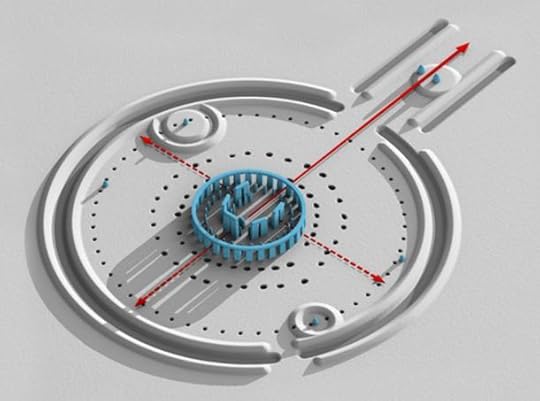

Stone 53 with ‘The Dividers’ symbol. Credit: Lloyd Matthews Stone 59 with ‘The Parallels’. Left: Stone 59 today. Right: Replica of Stone 59 as it would have once stood. Credit: Lloyd MatthewsTogether, they may have not only successfully cracked the mystery of these three symbols but also discovered the original purpose of 56 unusual holes that were dug around Stonehenge during the very first phase of its construction, famously known as the Aubrey Holes. It appears that these holes could likely have been used as a calendar counting system used to keep track of each passing day, with six and a half revolutions around Stonehenge marking a full year, and using the rising of the Summer Solstice sun as a way of astronomically marking the starting point of each new year.

Stone 59 with ‘The Parallels’. Left: Stone 59 today. Right: Replica of Stone 59 as it would have once stood. Credit: Lloyd MatthewsTogether, they may have not only successfully cracked the mystery of these three symbols but also discovered the original purpose of 56 unusual holes that were dug around Stonehenge during the very first phase of its construction, famously known as the Aubrey Holes. It appears that these holes could likely have been used as a calendar counting system used to keep track of each passing day, with six and a half revolutions around Stonehenge marking a full year, and using the rising of the Summer Solstice sun as a way of astronomically marking the starting point of each new year.

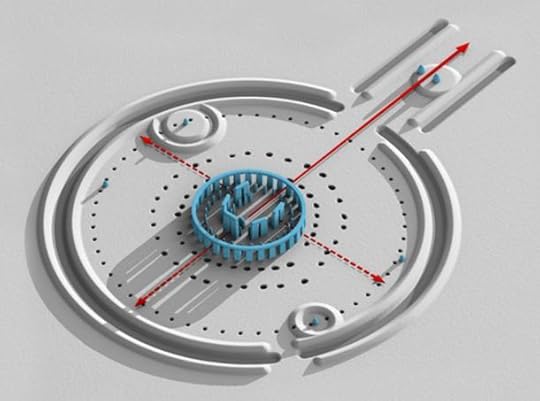

Replica of Stonehenge showing the Aubrey holes (

public domain

)As for the mysterious shapes carved into the Trilithons, they have shown how these symbols may have been deliberately positioned to allow the ancient astronomers at Stonehenge keep track of other significant astronomical cycles, including its use not only as a solar calendar but also as a lunar calendar.

Replica of Stonehenge showing the Aubrey holes (

public domain

)As for the mysterious shapes carved into the Trilithons, they have shown how these symbols may have been deliberately positioned to allow the ancient astronomers at Stonehenge keep track of other significant astronomical cycles, including its use not only as a solar calendar but also as a lunar calendar.

Dr Derek Cunningham, an established archaeological expert has even embraced this new theory himself, saying that "the idea is based on some solid observations. Not only can Lloyd now explain his three shapes, Joan's ideas help explain the layout and also the number of Aubrey Holes seen at the site. Neither had been satisfactorily explained before."

Dr Cunningham goes on to say, "Further work is expected, but it now appears that Stonehenge may finally be giving up some of its secrets."

Article source: Rankin, J., Matthews, J., Matthews, L., & Cunningham, D. The Aubrey Hole Calendar – Why 56 Holes. Available from: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B0_ibtG78fjRdzlkQUc3OHNvdGM/view

Original Source Material: Rankin, J., Matthews, J., & Matthews, L. (2015). The Stonehenge Carvings. Available from: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B4I_JxBys-S1bUN2ZVVuTk9CaGc/view

SOURCE The Office of Lloyd Matthews

Top image: Image of Stonehenge.

By James Matthews

Summer solstice is fast approaching, and on the 20th June over 20,000 people are expected to gather at the world-famous Stonehenge to celebrate and watch the sun rise above the Heel Stone and shine on the central altar. For those of us in the northern hemisphere, this is a time when the sun's path stops moving northward in the sky, the days stop growing longer and will soon begin to shorten again.

Over 5000 years old, Stonehenge was built in three phases between 3,000 B.C. and 1,600 B.C. Its full purpose remains unknown yet the mystery that surrounds Stonehenge is so enduring and popular that last year over 1.3 million visitors flocked to this ancient monument. There are even several man-made copies of the world-famous heritage site have been built around the world, including an impressive full-scale replica at the Maryhill Museum in Washington, USA.

Painting of the Maryhill replica of Stonehenge (

Michael D Martin / Flickr

)Stonehenge famously aligns to the solstices, but for the rest of the year it seems strange that these ancient builders would not be aware of the current day, or for that matter how many days remained to the next solstice event. However, a new theory has been presented that suggests Stonehenge was used for more than just marking the winter and summer solstices, or as a sacred burial site.

Painting of the Maryhill replica of Stonehenge (

Michael D Martin / Flickr

)Stonehenge famously aligns to the solstices, but for the rest of the year it seems strange that these ancient builders would not be aware of the current day, or for that matter how many days remained to the next solstice event. However, a new theory has been presented that suggests Stonehenge was used for more than just marking the winter and summer solstices, or as a sacred burial site.Recently, Lloyd Matthews (scale modelling expert based in the UK) and Joan Rankin (a retired historian living in Canada), have made an ambitious attempt to rethink the purpose of Stonehenge. Their conclusion, after three years of extensive and laborious research, is that the entire structure was, in fact, a complex and significant prehistoric calendar that could actually count the individual days in a year. Not only did Stonehenge act as a solar calendar, similar to the western calendar used today, but it also acted as a lunar calendar and was important for a developing agricultural society to successfully plan for the seasons.

Lloyd Matthews spent 6 years meticulously researching and constructing two scale models of Stonehenge for display at The Maryhill Museum of Art. The models show Stonehenge as it stands today and as it would have originally looked when built.

Lloyd Matthew’s models showing Stonehenge as it stands today and as it would have originally looked. Credit:

Lloyd Matthews

During its construction, Mr Matthews identified three distinct carvings on three of the large stones known as Trilithons (shown below). Curiosity piqued, Mr Matthews approached several experts at the time who were unable to provide an explanation as to what these symbols meant. Dissatisfied with the responses, Mr Matthews decided to continue his research into this ancient puzzle with the help of Joan Rankin, an authority in prehistory.

Lloyd Matthew’s models showing Stonehenge as it stands today and as it would have originally looked. Credit:

Lloyd Matthews

During its construction, Mr Matthews identified three distinct carvings on three of the large stones known as Trilithons (shown below). Curiosity piqued, Mr Matthews approached several experts at the time who were unable to provide an explanation as to what these symbols meant. Dissatisfied with the responses, Mr Matthews decided to continue his research into this ancient puzzle with the help of Joan Rankin, an authority in prehistory. Stone 52 with ‘The Eye’ symbol. From Left: Stone 52 today (Credit: Lloyd Matthews), Replica of Stone 52 (Credit: Lloyd Matthews), Stone 52 in 1867.

Stone 52 with ‘The Eye’ symbol. From Left: Stone 52 today (Credit: Lloyd Matthews), Replica of Stone 52 (Credit: Lloyd Matthews), Stone 52 in 1867.  Stone 53 with ‘The Dividers’ symbol. Credit: Lloyd Matthews

Stone 53 with ‘The Dividers’ symbol. Credit: Lloyd Matthews Stone 59 with ‘The Parallels’. Left: Stone 59 today. Right: Replica of Stone 59 as it would have once stood. Credit: Lloyd MatthewsTogether, they may have not only successfully cracked the mystery of these three symbols but also discovered the original purpose of 56 unusual holes that were dug around Stonehenge during the very first phase of its construction, famously known as the Aubrey Holes. It appears that these holes could likely have been used as a calendar counting system used to keep track of each passing day, with six and a half revolutions around Stonehenge marking a full year, and using the rising of the Summer Solstice sun as a way of astronomically marking the starting point of each new year.

Stone 59 with ‘The Parallels’. Left: Stone 59 today. Right: Replica of Stone 59 as it would have once stood. Credit: Lloyd MatthewsTogether, they may have not only successfully cracked the mystery of these three symbols but also discovered the original purpose of 56 unusual holes that were dug around Stonehenge during the very first phase of its construction, famously known as the Aubrey Holes. It appears that these holes could likely have been used as a calendar counting system used to keep track of each passing day, with six and a half revolutions around Stonehenge marking a full year, and using the rising of the Summer Solstice sun as a way of astronomically marking the starting point of each new year. Replica of Stonehenge showing the Aubrey holes (

public domain

)As for the mysterious shapes carved into the Trilithons, they have shown how these symbols may have been deliberately positioned to allow the ancient astronomers at Stonehenge keep track of other significant astronomical cycles, including its use not only as a solar calendar but also as a lunar calendar.

Replica of Stonehenge showing the Aubrey holes (

public domain

)As for the mysterious shapes carved into the Trilithons, they have shown how these symbols may have been deliberately positioned to allow the ancient astronomers at Stonehenge keep track of other significant astronomical cycles, including its use not only as a solar calendar but also as a lunar calendar.Dr Derek Cunningham, an established archaeological expert has even embraced this new theory himself, saying that "the idea is based on some solid observations. Not only can Lloyd now explain his three shapes, Joan's ideas help explain the layout and also the number of Aubrey Holes seen at the site. Neither had been satisfactorily explained before."

Dr Cunningham goes on to say, "Further work is expected, but it now appears that Stonehenge may finally be giving up some of its secrets."

Article source: Rankin, J., Matthews, J., Matthews, L., & Cunningham, D. The Aubrey Hole Calendar – Why 56 Holes. Available from: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B0_ibtG78fjRdzlkQUc3OHNvdGM/view

Original Source Material: Rankin, J., Matthews, J., & Matthews, L. (2015). The Stonehenge Carvings. Available from: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B4I_JxBys-S1bUN2ZVVuTk9CaGc/view

SOURCE The Office of Lloyd Matthews

Top image: Image of Stonehenge.

By James Matthews

Published on June 26, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Pied Piper leads children out of Hamelin

Published on June 26, 2016 02:00