MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 93

June 20, 2016

The dangerous streets of ancient Rome

History Extra

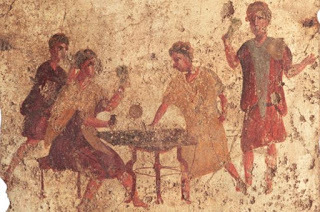

A fresco painting of game players in a tavern on the Via di Mercurio in Pompeii. (Corbis)

Ancient Rome after dark was a dangerous place. Most of us can easily imagine the bright shining marble spaces of the imperial city on a sunny day – that’s usually what movies and novels show us, not to mention the history books. But what happened when night fell? More to the point, what happened for the vast majority of the population of Rome, who lived in the over-crowded high-rise garrets, not in the spacious mansions of the rich?

Remember that, by the first century BC, the time of Julius Caesar, ancient Rome was a city of a million inhabitants – rich and poor, slaves and ex-slaves, free and foreign. It was the world’s first multicultural metropolis, complete with slums, multiple-occupancy tenements and sink estates – all of which we tend to forget when we concentrate on its great colonnades and plazas. So what was backstreet Rome – the real city – like after the lights went out? Can we possibly recapture it?

The best place to start is the satire of that grumpy old Roman man, Juvenal, who conjured up a nasty picture of daily life in Rome around AD 100. The inspiration behind every satirist from Dr Johnson to Stephen Fry, Juvenal reminds us of the dangers of walking around the streets after dark: the waste (that is, chamber pot plus contents) that might come down on your head from the upper floors; not to mention the toffs (the blokes in scarlet cloaks, with their whole retinue of hangers on) who might bump into you on your way through town, and rudely push you out of the way:

“And now think of the different and diverse perils of the night. See what a height it is to that towering roof from which a pot comes crack upon my head every time that some broken or leaky vessel is pitched out of the window! See with what a smash it strikes and dints the pavement! There’s death in every open window as you pass along at night; you may well be deemed a fool, improvident of sudden accident, if you go out to dinner without having made your will… Yet however reckless the fellow may be, however hot with wine and young blood, he gives a wide berth to one whose scarlet cloak and long retinue of attendants, with torches and brass lamps in their hands, bid him keep his distance. But to me, who am wont to be escorted home by the moon, or by the scant light of a candle he pays no respect.” (Juvenal /Satire/ 3)

Juvenal himself was actually pretty rich. All Roman poets were relatively well heeled (the leisure you needed for writing poetry required money, even if you pretended to be poor). His self-presentation as a ‘man of the people’ was a bit of a journalistic facade. But how accurate was his nightmare vision of Rome at night? Was it really a place where chamber pots crashed on your head, the rich and powerful stamped all over you, and where (as Juvenal observes elsewhere) you risked being mugged and robbed by any group of thugs that came along?

Probably yes.

Outside the splendid civic centre, Rome was a place of narrow alleyways, a labyrinth of lanes and passageways. There was no street lighting, nowhere to throw your excrement and no police force. After dark, ancient Rome must have been a threatening place. Most rich people, I’m sure, didn’t go out – at least, not without their private security team of slaves or their “long retinue of attendants” – and the only public protection you could hope for was the paramilitary force of the night watch, the vigiles.

Exactly what these watchmen did, and how effective they were, is a moot point. They were split into battalions across the city and their main job was to look out for fires breaking out (a frequent occurrence in the jerry-built tenement blocks, with open braziers burning on the top floors). But they had little equipment to deal with a major outbreak, beyond a small supply of vinegar and a few blankets to douse the flames, and poles to pull down neighbouring buildings to make a fire break.

Part of the Palatine Hill, one of the most ancient areas of the city. (Bridgeman Art Library)

While Rome burnedSometimes these men were heroes. In fact, a touching memorial survives to a soldier, acting as a night watchman at Ostia, Rome’s port. He had tried to rescue people stranded in a fire, had died in the process and was given a burial at public expense. But they weren’t always so altruistic. In the great fire of Rome in AD 64 one story was that the vigiles actually joined in the looting of the city while it burned. The firemen had inside knowledge of where to go and where the rich pickings were.

Certainly the vigiles were not a police force, and had little authority when petty crimes at night escalated into something much bigger. They might well give a young offender a clip round the ear. But did they do more than that? There wasn’t much they could do, and mostly they weren’t around anyway.

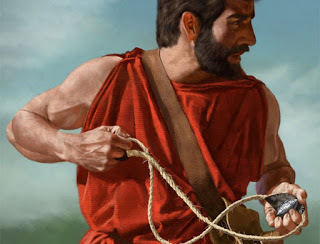

If you were a crime victim, it was a matter of self-help – as one particularly tricky case discussed in an ancient handbook on Roman law proves. The case concerns a shop-keeper who kept his business open at night and left a lamp on the counter, which faced onto the street. A man came down the street and pinched the lamp, and the man in the shop went after him, and a brawl ensued. The thief was carrying a weapon – a piece of rope with a lump of metal at the end – and he coshed the shop-keeper, who retaliated and knocked out the eye of the thief.

This presented Roman lawyers with a tricky question: was the shopkeeper liable for the injury? In a debate that echoes some of our own dilemmas about how far a property owner should go in defending himself against a burglar, they decided that, as the thief had been armed with a nasty piece of metal and had struck the first blow, he had to take responsibility for the loss of his eye.

But, wherever the buck stopped (and not many cases like this would ever have come to court, except in the imagination of some academic Roman lawyers), the incident is a good example for us of what could happen to you on the streets of Rome after dark, where petty crime could soon turn into a brawl that left someone half-blind.

And it wasn’t just in Rome itself. One case, from a town on the west coast of modern Turkey, at the turn of the first centuries BC and AD, came to the attention of the emperor Augustus himself. There had been a series of night-time scuffles between some wealthy householders and a gang that was attacking their house (whether they were some young thugs who deserved the ancient equivalent of an ASBO, or a group of political rivals trying to unsettle their enemies, we have no clue). Finally, one of the slaves inside the house, who was presumably trying to empty a pile of excrement from a chamber pot onto the head of a marauder, actually let the pot fall – and the result was that the marauder was mortally injured.

The case, and question of where guilt for the death lay, was obviously so tricky that it went all the way up to the emperor himself, who decided (presumably on ‘self-defence’ grounds) to exonerate the householders under attack. And it was presumably those householders who had the emperor’s judgment inscribed on stone and put on display back home. But, for all the slightly puzzling details of the case, it’s another nice illustration that the streets of the Roman world could be dangerous after dark; and that Juvenal might not have been wrong about those falling chamber pots.

But night-time Rome wasn’t just dangerous. There was also fun to be had in the clubs, taverns and bars late at night. You might live in a cramped flat in a high-rise block, but, for men at least, there were places to go to drink, to gamble and (let’s be honest) to flirt with the barmaids.

The remains of a tavern in the Roman port town of Ostia. (Copyright Alamy)

The Roman elite were pretty sniffy about these places. Gambling was a favourite activity right through Roman society. The emperor Claudius was even said to have written a handbook on the subject. But, of course, this didn’t prevent the upper classes decrying the bad habits of the poor, and their addiction to games of chance. One snobbish Roman writer even complained about the nasty snorting noises that you would hear late at night in a Roman bar – the noises that came from a combination of snotty noses and intense concentration on the board game in question.

Happily, though, we do have a few glimpses into the fun of the Roman bar from the point of view of the ordinary users themselves. That is, we can still see some of the paintings that decorated the walls of the ordinary, slightly seedy bars of Pompeii – showing typical scenes of bar life. These focus on the pleasures of drink (we see groups of men sitting around bar tables, ordering another round from the waitress), we see flirtation (and more) going on between customers and barmaids, and we see a good deal of board gaming.

Interestingly, even from this bottom-up perspective, there is a hint of violence. In the paintings from one Pompeian bar (now in the Archaeological Museum at Naples), the final scene in a series shows a couple of gamblers having a row over the game, and the landlord being reduced to threatening to throw his customers out. In a speech bubble coming out of the landlord’s mouth, he is saying (as landlords always have) “Look, if you want a fight, guys, get outside”.

So where were the rich when this edgy night life was going on in the streets? Well most of them were comfortably tucked up in their beds, in their plush houses, guarded by slaves and guard dogs. Those mosaics in the forecourts of the houses of Pompeii, showing fierce canines and branded Cave Canem (‘Beware of the Dog’), are probably a good guide to what you would have found greeting you if you had tried to get into one of these places.

Inside the doors, peace reigned (unless the place was being attacked of course!), and the rough life of the streets was barely audible. But there is an irony here. Perhaps it isn’t surprising that some of the Roman rich, who ought to have been tucked up in bed in their mansions, thought that the life of the street was extremely exciting in comparison. And – never mind all those snobbish sneers about the snorting of the bar gamblers – that’s exactly where they wanted to be.

A man refills his cup from a wine cask in this first-century AD Roman relief. (akg-images)

Rome’s mean streets were where you could apparently find the Emperor Nero on his evenings off. After dark, so his biographer Suetonius tells us, he would disguise himself with a cap and wig, visit the city bars and roam around the streets, running riot with his mates. When he met men making their way home after dinner, he’d beat them up; he’d even break into closed shops, steal some of the stock and sell it in the palace. He would get into brawls – and apparently often ran the risk of having an eye put out (like the thief with the lamp), or even of ending up dead.

So while many of the city’s richest residents would have avoided the streets of Rome after dark at all costs – or only ventured onto them accompanied by their security guard – others would not just be pushing innocent pedestrians out of the way, they’d be prowling around, giving a very good pretence of being muggers. And, if Suetonius is to be believed, the last person you’d want to bump into late at night in downtown Rome would be the Emperor Nero.

Published on June 20, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Battle of Chalons

June 20

451 Battle of Chalons: Flavius Aetius' defeated Attila the Hun at Catalarinische Fields. Theodorid, King of the Visigoths was mortally wounded in this battle.

451 Battle of Chalons: Flavius Aetius' defeated Attila the Hun at Catalarinische Fields. Theodorid, King of the Visigoths was mortally wounded in this battle.

Published on June 20, 2016 02:00

June 19, 2016

Evidence Accumulates for Ancient Transoceanic Voyages, Says Geographer

Ancient Origins

Theories on the fringe of science sometimes slowly work their way into the core as the evidence accumulates.

Theories on the fringe of science sometimes slowly work their way into the core as the evidence accumulates.“A classic example is the continental drift [theory],” said cultural geographer Stephen C. Jett, professor emeritus at the University of California–Davis. “In 1955, if you believed in continental drift, you were laughed at. In 1965, if you didn’t believe in continental drift, you were laughed at.”He was a geography student while this dramatic change in opinion occurred, and he took the example to heart. Encouraged by a professor of his at Johns Hopkins University, Jett started a decades-long investigation into another controversial theory.

DiffusionismMainstream anthropology and archaeology holds that Norse expeditions around 1000 A.D. were the only ones to make it to the New World before Christopher Columbus landed in the 15th century. But on the fringes are multiple theories about other successful pre-Columbian expeditions. These theories are placed under the umbrella of “diffusionism.”

“At the outset, I supposed that accumulating the evidence and … putting it out there would change the point of view, at least gradually,” Jett said. “But there hasn’t seemed to have been a lot of that. There’s a good deal of inertia, a good deal of resistance to the whole concept.”According to Jett, one of the reasons it has been difficult for the concept of early transoceanic voyages to penetrate mainstream history is that it requires a multidisciplinary perspective.

“If you confine yourself to one field, you won’t see it,” he said.

Jett has a multidisciplinary perspective. “Geography is a very broad discipline,” he explained. For example, physical geography gives insight into climate, oceans, landforms, and other elements relevant to long-distance travel. Cultural geography, Jett’s specialty, has helped him see many similarities between ancient Old and New World cultures. But, he said, more biological evidence is emerging to supplement the cultural evidence.

As a graduate student, he discovered precise similarities of blowgun construction in various cultures. The similarities could not, in his opinion, have arisen independently; they clearly point to transoceanic contact and influence. But, he said, more biological evidence is emerging to supplement the cultural evidence. Research into the spread of diseases and plant species, for example, suggests ancient transoceanic contact.

Jett outlined what he calls “six evidentiary revolutions” across several fields that have greatly boosted the diffusionist theories. “We’re getting close to what could be a turning point,” he said.

It is beyond the scope of this article to explore every “evidentiary revolution” in depth, but we will briefly look at each as discussed by Jett.

‘Evidentiary Revolution’ No. 1: Maritime Archaeology and Navigation TraditionsA major objection raised against the so-called diffusionist theories is that transoceanic travel would not have been possible with the watercraft and navigation techniques available to ancient peoples who supposedly made it to the New World.

But many replica boats have made the journey in modern times, successfully using only the technology available in antiquity. One famous example is that of Dr. Thor Heyerdahl, who built a boat similar to those used by ancient Egyptians, made of papyrus, and sailed it from Morocco to Barbados in 1970.

Hokule’a (

Phil Uhl/CC BY-SA

)Some 20 or more similar, successful voyages have been made, Jett said. He cited as another example the 1985 voyage of Hokule’a, a reconstructed ancient double canoe, from Hawai’i to New Zealand using traditional methods of navigation.

Hokule’a (

Phil Uhl/CC BY-SA

)Some 20 or more similar, successful voyages have been made, Jett said. He cited as another example the 1985 voyage of Hokule’a, a reconstructed ancient double canoe, from Hawai’i to New Zealand using traditional methods of navigation.‘Evidentiary Revolution’ No. 2: Parasites and PathogensThe swapping of parasites and diseases between the Old and New Worlds may have occurred before Columbus. For example, researchers at the National School of Public Health (Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública-Fiocruz) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, conducted a review in 2003 of documented parasites found at archaeological sites.

The study, “Human Intestinal Parasites in the Past,” states: “Ancylostomids [hookworms] have been found in archaeological sites from both New and Old Worlds. … Human infection has been present in Amerindians far before Columbus. It strongly suggests some kind of transoceanic contact before 7230 ± 80 years ago. … Ancylostomids … require warm and moist conditions to complete their life cycles outside their host, [and] could not have survived during human migration by land through Bering Strait during the last ice age.”

A hookworm (

Fernand Olive/Public Domain

)Jett mentioned that tuberculosis and syphilis are among the diseases apparently present in both the Old and New World in antiquity. The theory that they were spread by pre-Columbian human contact remains controversial.

A hookworm (

Fernand Olive/Public Domain

)Jett mentioned that tuberculosis and syphilis are among the diseases apparently present in both the Old and New World in antiquity. The theory that they were spread by pre-Columbian human contact remains controversial.The spread of tuberculosis has been said to have taken place via seals. As for syphilis, it was long thought to have been brought to the Old World by Columbus’ crewmen, who contracted it in the New World. Some evidence in Old World skeletal remains has suggested, however, that it was present in the Old World before Columbus.

Researchers at the University of Vienna, for example, published a paper titled “A probable case of congenital syphilis from pre-Columbian Austria,” in 2015, after studying the remains of a child. The paper states: “Our findings contribute to the pre-Columbian theory, offering counterevidence to the assumption that syphilis was carried from Columbus’ crew from the New to the Old World.”

But many experts say the evidence for pre-Columbian syphilis in the Old World is inconclusive, that the symptoms evident in these skeletal remains may have been left by conditions other than syphilis.

‘Evidentiary Revolution’ No. 3: DomesticatesJett said: “Now we have archaeological remains of cultivated plants, probably around 20 of them, that have been found in the wrong hemisphere—that is to say, New World domesticates found in archaeological sites in South Asia and here and there.”

“A lot of it has been published in overseas journals that most Americans don’t read,” Jett said.For example, custard apple (Annona squamosa) seeds found at an archaeological site in north-central India were analyzed by Anil Kumar Pokharia at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany and other Indian researchers in 2009. The custard apple, native to South America and the West Indies, was previously thought to have been brought to India by the Portuguese in the 16th century.

Pokharia wrote, however, in his study published in the journal Radiocarbon: “Dates of the samples push back the antiquity of custard apple on Indian soil to the 2nd millennium B.C., favoring a group of specialists proposing diverse arguments for Asian-American transoceanic contacts before the discovery of America by Columbus in 1492 A.D.”

A file photo of a custard apple. (

Elijah van der Giessen/CC BY

)Carl Johannessen, a retired University of Oregon geography professor, and John Sorenson, an emeritus professor of anthropology at Brigham Young University, have also collected many biological references, Jett noted.

A file photo of a custard apple. (

Elijah van der Giessen/CC BY

)Carl Johannessen, a retired University of Oregon geography professor, and John Sorenson, an emeritus professor of anthropology at Brigham Young University, have also collected many biological references, Jett noted.The chicken is one domesticate that has received a lot of attention even in American media, Jett said.

In 2007, anthropologist Alice A. Storey at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, led a study titled “Radiocarbon and DNA evidence for a pre-Columbian introduction of Polynesian chickens to Chile.”

Chicken bones found in Chile seemed to prove Polynesians introduced chickens to the Americas before Columbus. In 2014, a study led by Alan Cooper, director of the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA, took a different approach to DNA analysis of the chicken bones and suggested they were genetically distinct from Polynesian chickens.

But Storey stands by her analysis and criticizes Cooper’s study for using DNA from modern South American chickens in its comparison.

She told National Geographic: “The bulk of their research focuses on modern DNA. Using modern DNA to understand what people were doing in the past is like sampling a group of commuters at a London Tube station at rush hour. The DNA you get is unlikely to provide much useful information on the pre-Roman population of London.”

Research on other domesticates found at archaeological sites in South America and elsewhere continues to tantalize experts.

David Burley, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University in Canada, has no doubt Polynesians reached the New World. He told National Geographic: “The evidence for Polynesian contact with the New World prior to Columbus is substantial. We have the sweet potato, the bottle gourd, all this New World stuff that has been firmly documented as being out here pre-Columbian. If the Polynesians could find Easter Island, which is just this tiny speck, don’t you think they could have found an entire continent?”

‘Evidentiary Revolution’ No. 4: Human GeneticsHuman genetic evidence for transoceanic contact, found in indigenous New World populations, is often dismissed as being contaminated by colonial European genetic material coming in after Columbus.

“But the patterns, especially those characteristic of South or East Asia, do not closely match those of the sources of the colonizers,” Jett said, “because there wasn’t any significant colonization from those areas in colonial times.”He also pointed out that the genetic markers are found in the same areas there are cultural manifestations that suggest early transoceanic contact.

Dr. Donald Panther Yates has analyzed Cherokee DNA and culture to find links with the Old World he says must have been forged long before Columbus arrived.

In a paper titled “Anomalous Mitochondrial DNA Lineages in the Cherokee,” Yates discussed two genetic groups, known as haplogroups T and X, in the Cherokee.

He wrote: “The level of haplogroup T in the Cherokee (26.9 percent) approximates the percentage for Egypt (25 percent), one of the only lands where T attains a major position among the various mitochondrial lineages.”

Of haplogroup X, he wrote: “The only other place on Earth where X is found at an elevated level apart from other American Indian groups like the Ojibwe is among the Druze in the Hills of Galilee in northern Israel and Lebanon.”

Yates also observed parallels between Cherokee language and ancient Old World languages. For example, the Cherokee word, karioi—meaning “leisure” or “ease”—is literally the same word in Greek for “amusements.”

‘Evidentiary Revolutions’ No. 5 and No. 6: Linguistics and Calendar SystemsJett referenced the work of Brian Stubbs—a linguist at Utah State University Eastern, Blanding Campus—as suggesting a link between the Old World and the New. Stubbs recently published a volume showing an overlap between Uto-Aztecan languages of the New World and Afro-Asiatic languages, such as ancient Egyptian and Semitic languages.

Many other connections have been made but haven’t received much professional attention yet, Jett said. He hopes linguists will follow some of these promising leads.

Jett edits a journal titled Pre-Columbiana. In the forthcoming issue, he will publish an article written 30 years ago (but which has remained unpublished until now) by the late prominent archaeologist and epigrapher David H. Kelley that shows similarities between the Mayan and Eurasian calendar systems. Kelley argued that these similarities would not have arisen independently. Kelley earned fame in the 1960s for major contributions toward deciphering Mayan script.

ObstaclesThough some of the objections to diffusionist theories have been evidentiary—that is, questioning the validity of the evidence—Jett has seen other kinds of obstacles as these theories work their way into the mainstream.

Some people feel that diffusionists belittle indigenous American populations by suggesting that those cultures would not have formed independently, but instead required input from the Old World. Some diffusionist studies are also not sufficiently rigorous, marring the reputation of diffusionists in general, Jett said.

Furthermore, diffusionism calls into question scientists’ efforts to make generalizations about how cultures develop. If all civilizations are historically related, then there are no independent examples to compare to one another in order to formulate generalizations. This acts as a psychological obstacle in the minds of anthropologists, Jett said. It undermines much of the seeming progress made in this field of study.

As evidence continues to accumulate, and with a continual influx of young scientists replacing the old, Jett feels we’re on the cusp of an overall breakthrough for the diffusionist perspective. Jett’s book, “Ancient Ocean Crossings” is in press at the University of Alabama Press and is expected early next year.

Top image: Credit: April Holloway

The article ‘ Evidence Accumulates for Ancient Transoceanic Voyages, Says Geographer’ was originally published on The Epoch Times and has been republished with permission

Published on June 19, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Magna Carta sealed

June 19

1215 Magna Carta sealed: Following a revolt by the English nobility against his rule, King John puts his royal seal on the Magna Carta, or "Great Charter."

1215 Magna Carta sealed: Following a revolt by the English nobility against his rule, King John puts his royal seal on the Magna Carta, or "Great Charter."

Published on June 19, 2016 02:00

June 18, 2016

Evidence Found for Secret Terror Weapon of the Romans

Ancient Origins

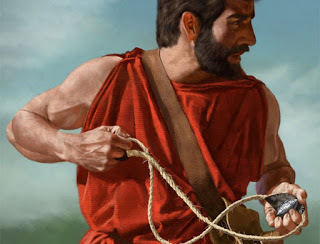

Archeologists have unearthed a set of Roman lead sling bullets which were used against the barbarian foes in Scotland. The bullets were found to make a piercing whistle noise when hurled through the air, a sound thought to have been used to strike terror in their enemies 1,800 years ago.

According to an article published recently by LiveScience, the bullets were discovered at Burnswark Hill in southwestern Scotland. The find was made during the excavation of a field where a massive attack of the Roman army took a place in the 2nd century AD.

Burnswark Hill, Scotland (

geograph.co.uk

)The excavation work was led by John Reid of the Trimontium Trust, a Scottish historical society which is directing the first major archaeological investigation of Burnswark Hill site in 50 years. The bullets weigh about 1 ounce (30 grams) and had been drilled with a 0.2-inch (5 millimeters) hole. The researchers believe that it was designed to give the soaring bullets a sharp buzzing or whistling noise in flight, making them what they called a real ''terror weapon''.

Burnswark Hill, Scotland (

geograph.co.uk

)The excavation work was led by John Reid of the Trimontium Trust, a Scottish historical society which is directing the first major archaeological investigation of Burnswark Hill site in 50 years. The bullets weigh about 1 ounce (30 grams) and had been drilled with a 0.2-inch (5 millimeters) hole. The researchers believe that it was designed to give the soaring bullets a sharp buzzing or whistling noise in flight, making them what they called a real ''terror weapon''.

John Reid said to LiveScience:

Some of the Roman sling bullets found at the Burnswark Hill battle site in Scotland. The two smallest bullets, shown at the bottom of this image, are drilled with a hole that makes them whistle in flight. Credit: John Reid/Trimontium TrustAbout 20 percent of the lead sling bullets discovered at Burnswark Hill had been drilled with the holes. They were also smaller than the typical bullets, so the researchers pinpointed that the soldiers may have used several of them with one throw. The size of the bullets gave the ability to fire them in groups of three or four, so the soldiers could receive a scattergun effect. The researchers believe that they were for ''close-quarter skirmishing''.

Some of the Roman sling bullets found at the Burnswark Hill battle site in Scotland. The two smallest bullets, shown at the bottom of this image, are drilled with a hole that makes them whistle in flight. Credit: John Reid/Trimontium TrustAbout 20 percent of the lead sling bullets discovered at Burnswark Hill had been drilled with the holes. They were also smaller than the typical bullets, so the researchers pinpointed that the soldiers may have used several of them with one throw. The size of the bullets gave the ability to fire them in groups of three or four, so the soldiers could receive a scattergun effect. The researchers believe that they were for ''close-quarter skirmishing''.

Sling bullets are a very common find at excavation sites related to Roman army battles in Europe. The largest ones are shaped like lemons and weigh up to 2 ounces (60 grams). The smaller bullets, shaped like acorns, are a common find on the site in Scotland. Apart from Romans, Greeks also used them during battles. However, the researchers suggest that the holes in Greek bullets were reservoirs for poison. Some of the bullets contain written messages intended to taunt their enemy. As Ancient Origins writer, Mark Miller, explained in his article:

''Writing messages on bullets and missiles goes back at least to Biblical times and continues to modern times among Israelis, Jordanians, Americans and others. The practice became industrial to ancient Greeks and Romans, who manufactured lead sling bullets in molds with taunting messages in bas-relief, such as ‘Ouch!’, ‘Be lodged well’, and ‘Here’s a sugar plum for you!’.

Ancient Greek sling bullets with engravings. One side depicts a winged thunderbolt, and the other, the Greek inscription “take that” in high relief. (

Wikimedia Commons

)The ancient Greeks and Romans produced lead bullets for use in slings in mass quantities, sometimes in molds and sometimes just by digging a hole into sand and pouring molten lead into it. The messages that ancient Romans put on lead sling bullets ranged from naming the leader of the sling unit, the commander of the troops or messages invoking a god or wishing injury upon or insulting the targets.

Ancient Greek sling bullets with engravings. One side depicts a winged thunderbolt, and the other, the Greek inscription “take that” in high relief. (

Wikimedia Commons

)The ancient Greeks and Romans produced lead bullets for use in slings in mass quantities, sometimes in molds and sometimes just by digging a hole into sand and pouring molten lead into it. The messages that ancient Romans put on lead sling bullets ranged from naming the leader of the sling unit, the commander of the troops or messages invoking a god or wishing injury upon or insulting the targets.

Bullets launched with a sling traveled farther than an arrow and caused devastating though subtle injuries to the people they struck, according to ancient sources. Lead made a very good missile because it is heavy and could remain small and because they were very hard to see and avoid.''

When the Romans attacked at Burnswark Hill, the slings were used mainly by specialized units of auxiliary troops ("auxilia") recruited to fight alongside the Roman legions. In ancient times, the Balearic Islands, an archipelago near Spain in the western Mediterranean, was famous for the best Roman slingers. They supported Julius Caesar during his unsuccessful invasions of Britain in 55 BC and 54 BC.

The work of a slinger wasn't easy, but their strategy was very effective. According to Current Archeology, the 50g bullets could be cast at least 200 meters and reach speeds of up to 100 mph (160 km/h). This means that a Roman bullet propelled from a sling has only slightly less kinetic energy than a shot from a 44 Magnum gun.

The Brunswark Hill site lies a few miles away from the line of Roman forts and Hadrian's Wall. The attack of the Romans was perhaps a part of the military campaign by Antonius Pius, the successor of Hadrian. The war with Scottish tribes took about 20 years, until 158 AD, when the Romans gave up their plans to conquer those lands.

Top image: A Spartan using a sling. Credit: Shumate

By Natalia Klimzcak

Archeologists have unearthed a set of Roman lead sling bullets which were used against the barbarian foes in Scotland. The bullets were found to make a piercing whistle noise when hurled through the air, a sound thought to have been used to strike terror in their enemies 1,800 years ago.

According to an article published recently by LiveScience, the bullets were discovered at Burnswark Hill in southwestern Scotland. The find was made during the excavation of a field where a massive attack of the Roman army took a place in the 2nd century AD.

Burnswark Hill, Scotland (

geograph.co.uk

)The excavation work was led by John Reid of the Trimontium Trust, a Scottish historical society which is directing the first major archaeological investigation of Burnswark Hill site in 50 years. The bullets weigh about 1 ounce (30 grams) and had been drilled with a 0.2-inch (5 millimeters) hole. The researchers believe that it was designed to give the soaring bullets a sharp buzzing or whistling noise in flight, making them what they called a real ''terror weapon''.

Burnswark Hill, Scotland (

geograph.co.uk

)The excavation work was led by John Reid of the Trimontium Trust, a Scottish historical society which is directing the first major archaeological investigation of Burnswark Hill site in 50 years. The bullets weigh about 1 ounce (30 grams) and had been drilled with a 0.2-inch (5 millimeters) hole. The researchers believe that it was designed to give the soaring bullets a sharp buzzing or whistling noise in flight, making them what they called a real ''terror weapon''.John Reid said to LiveScience:

"You don't just have these silent but deadly bullets flying over; you've got a sound effect coming off them that would keep the defenders' heads down. Every army likes an edge over its opponents, so this was an ingenious edge on the permutation of sling bullets."

Some of the Roman sling bullets found at the Burnswark Hill battle site in Scotland. The two smallest bullets, shown at the bottom of this image, are drilled with a hole that makes them whistle in flight. Credit: John Reid/Trimontium TrustAbout 20 percent of the lead sling bullets discovered at Burnswark Hill had been drilled with the holes. They were also smaller than the typical bullets, so the researchers pinpointed that the soldiers may have used several of them with one throw. The size of the bullets gave the ability to fire them in groups of three or four, so the soldiers could receive a scattergun effect. The researchers believe that they were for ''close-quarter skirmishing''.

Some of the Roman sling bullets found at the Burnswark Hill battle site in Scotland. The two smallest bullets, shown at the bottom of this image, are drilled with a hole that makes them whistle in flight. Credit: John Reid/Trimontium TrustAbout 20 percent of the lead sling bullets discovered at Burnswark Hill had been drilled with the holes. They were also smaller than the typical bullets, so the researchers pinpointed that the soldiers may have used several of them with one throw. The size of the bullets gave the ability to fire them in groups of three or four, so the soldiers could receive a scattergun effect. The researchers believe that they were for ''close-quarter skirmishing''.Sling bullets are a very common find at excavation sites related to Roman army battles in Europe. The largest ones are shaped like lemons and weigh up to 2 ounces (60 grams). The smaller bullets, shaped like acorns, are a common find on the site in Scotland. Apart from Romans, Greeks also used them during battles. However, the researchers suggest that the holes in Greek bullets were reservoirs for poison. Some of the bullets contain written messages intended to taunt their enemy. As Ancient Origins writer, Mark Miller, explained in his article:

''Writing messages on bullets and missiles goes back at least to Biblical times and continues to modern times among Israelis, Jordanians, Americans and others. The practice became industrial to ancient Greeks and Romans, who manufactured lead sling bullets in molds with taunting messages in bas-relief, such as ‘Ouch!’, ‘Be lodged well’, and ‘Here’s a sugar plum for you!’.

Ancient Greek sling bullets with engravings. One side depicts a winged thunderbolt, and the other, the Greek inscription “take that” in high relief. (

Wikimedia Commons

)The ancient Greeks and Romans produced lead bullets for use in slings in mass quantities, sometimes in molds and sometimes just by digging a hole into sand and pouring molten lead into it. The messages that ancient Romans put on lead sling bullets ranged from naming the leader of the sling unit, the commander of the troops or messages invoking a god or wishing injury upon or insulting the targets.

Ancient Greek sling bullets with engravings. One side depicts a winged thunderbolt, and the other, the Greek inscription “take that” in high relief. (

Wikimedia Commons

)The ancient Greeks and Romans produced lead bullets for use in slings in mass quantities, sometimes in molds and sometimes just by digging a hole into sand and pouring molten lead into it. The messages that ancient Romans put on lead sling bullets ranged from naming the leader of the sling unit, the commander of the troops or messages invoking a god or wishing injury upon or insulting the targets.Bullets launched with a sling traveled farther than an arrow and caused devastating though subtle injuries to the people they struck, according to ancient sources. Lead made a very good missile because it is heavy and could remain small and because they were very hard to see and avoid.''

When the Romans attacked at Burnswark Hill, the slings were used mainly by specialized units of auxiliary troops ("auxilia") recruited to fight alongside the Roman legions. In ancient times, the Balearic Islands, an archipelago near Spain in the western Mediterranean, was famous for the best Roman slingers. They supported Julius Caesar during his unsuccessful invasions of Britain in 55 BC and 54 BC.

The work of a slinger wasn't easy, but their strategy was very effective. According to Current Archeology, the 50g bullets could be cast at least 200 meters and reach speeds of up to 100 mph (160 km/h). This means that a Roman bullet propelled from a sling has only slightly less kinetic energy than a shot from a 44 Magnum gun.

The Brunswark Hill site lies a few miles away from the line of Roman forts and Hadrian's Wall. The attack of the Romans was perhaps a part of the military campaign by Antonius Pius, the successor of Hadrian. The war with Scottish tribes took about 20 years, until 158 AD, when the Romans gave up their plans to conquer those lands.

Top image: A Spartan using a sling. Credit: Shumate

By Natalia Klimzcak

Published on June 18, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Canterbury monks report explosion on the moon

June 18

1178 Proposed time of origin of the lunar crater Giordano Bruno - five Canterbury monks reported an explosion on the moon (only known observation).

1178 Proposed time of origin of the lunar crater Giordano Bruno - five Canterbury monks reported an explosion on the moon (only known observation).

Published on June 18, 2016 02:00

June 17, 2016

Lambert Simnel: Richard III’s heir who 'had a stronger claim to the throne than Henry VII'

History Extra

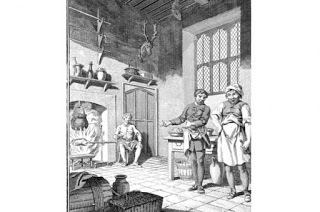

Lambert Simnel working in King Henry VII's kitchens. Simnel claimed to be Richard III’s heir and the rightful king of England, but was dismissed by the Tudor government as an imposter and he reputedly spent his teenage years as Henry VII’s prisoner in the Tower of London. (© SOTK2011/Alamy) Claiming to be Richard III’s heir and the rightful king of England, this boy – supposedly Edward Earl of Warwick, the son of Richard III’s brother, George, Duke of Clarence – was crowned king of England in Dublin Cathedral, despite the Tudor government insisting that his real name was Lambert Simnel and that he was an imposter. Now, in his new book, author and historian John Ashdown-Hill questions the generally accepted Tudor view that this boy was a mere pretender to the throne.

Lambert Simnel working in King Henry VII's kitchens. Simnel claimed to be Richard III’s heir and the rightful king of England, but was dismissed by the Tudor government as an imposter and he reputedly spent his teenage years as Henry VII’s prisoner in the Tower of London. (© SOTK2011/Alamy) Claiming to be Richard III’s heir and the rightful king of England, this boy – supposedly Edward Earl of Warwick, the son of Richard III’s brother, George, Duke of Clarence – was crowned king of England in Dublin Cathedral, despite the Tudor government insisting that his real name was Lambert Simnel and that he was an imposter. Now, in his new book, author and historian John Ashdown-Hill questions the generally accepted Tudor view that this boy was a mere pretender to the throne.In The Dublin King, Ashdown-Hill uses previously unpublished information to uncover the true identity of the Yorkist heir, who he concludes had a stronger claim to the throne than Henry VII. He also debunks the belief by some that the so-called ‘Dublin King’ himself claimed to be one of the ‘princes in the Tower’.

Here, Ashdown-Hill reveals the two conflicting life stories of Edward, 17th Earl of Warwick…

Born: 25 February 1475, Warwick Castle

Died: officially beheaded for treason, Tower Hill, 28 November 1499 – but his conflicting life story disputes this

Family: the third of four children of George, Duke of Clarence and his wife, Isabel Neville. Edward’s maternal grandfather was the famous ‘Kingmaker’ Earl of Warwick. His father’s brothers were the Yorkist kings, Edward IV and Richard III. Edward’s eldest sibling, Anne, and his younger brother, Richard, both died soon after being born. His mother, Isabel Duchess of Clarence, also died soon after Richard’s birth

Famous for: Reputedly spending his teenage years as Henry VII’s prisoner in the Tower of London, and suffering from a mental disability

Life: Edward’s father, George, believed his enemy Elizabeth Woodville (consort of his brother, Edward IV) was behind the poisoning of his wife and younger son. He became scared about the future of his surviving children – and himself.

Fear for his children led to plans to smuggle Edward out of the country - and to contacts with Ireland. Fear for his own future prompted George’s campaign against Elizabeth Woodville and her children. This resulted in George’s imprisonment and execution. Thus, as his third birthday approached, Edward Earl of Warwick found himself orphaned.

His uncle, Edward IV, sent for him. But King Edward IV had not seen his nephew and namesake for three years. Could the king have recognised the little boy who was handed over to him and then brought up as Earl of Warwick at the Tower of London?

In 1483, following the death of Edward IV, Richard III was offered the crown on the grounds that Edward IV had been legally married to Eleanor Talbot, daughter of Lord Shrewsbury. Thus Edward IV’s subsequent marriage to Elizabeth Woodville was bigamous and their children were illegitimate.

Richard III assumed care of young Warwick (then aged eight). He housed him at Sheriff Hutton Castle near York, with other Yorkist princes and princesses, and began training Warwick for a future position of power and influence.

In 1485 Richard III was killed at the battle of Bosworth. The usurper Henry VII had no real claim to the throne. To improve his weak position Henry decided to marry Elizabeth of York (eldest daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville). He revoked the act of Parliament which stated that Edward IV’s real wife had been Eleanor Talbot, and then represented Elizabeth to the nation as the Yorkist heiress.

But Henry VII was worried about Warwick. In 1470 King Henry VI had recognised George Duke of Clarence as the next Lancastrian heir to the throne after his own son. As Henry VI and his son had died in 1471, and George had died in 1478, by 1485 Warwick was the legitimate Lancastrian heir – a claim arguably unaffected by his father’s execution at the hands of a Yorkist king.

So Henry VII took charge of Warwick. First he was placed under the guardianship of Henry VII’s own mother, and later he was consigned to the Tower of London.

But curiously, at the same time an alternative ‘son of Clarence’ was being entertained in Mechelen, at the palace of his putative aunt, Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy: Margaret’s Edward Earl of Warwick had apparently been brought up in Ireland. Had George’s plot to smuggle his son and heir abroad in 1476 therefore succeeded?

Henry VII’s prisoner, or Margaret of York’s guest – which of the two Earls of Warwick was genuine?

Margaret’s ‘Warwick’ returned to Ireland with an army and key Yorkist supporters, led by Warwick’s cousin, the Earl of Lincoln. In Ireland they combined forces with the great Earl of Kildare – former friend and deputy of Warwick’s father.

On 24 May 1487, Margaret’s ‘Warwick’ was crowned ‘Edward VI, King of England’ at Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin. Henry VII’s anxious government sent servants to inspect the new king. They hoped to prove the boy a fraud, but when the servants met ‘Edward VI’ they were confused.

Later, Henry VII’s government announced that the boy crowned in Dublin was an impostor, named either ‘John [BLANK]’ or ‘Lambert Simnel’. But the government’s accounts of the ‘pretender’ were also confused. Fortunately for Henry VII, when ‘Edward VI’ invaded England, he was defeated at the battle of Stoke – and possibly captured – although one account says he escaped! The young prisoner became a servant in Henry VII’s kitchen under the name of ‘Lambert Simnel’.

Meanwhile, the official Earl of Warwick remained in the Tower. In 1499 he was condemned to death, to clear the path for the projected marriage of Henry VII’s son, Arthur, Prince of Wales, to the Spanish princess, Catherine of Aragon. His body was buried at Bisham Priory.

So which is the true story of Edward Earl of Warwick?

If the remains of the young man executed by Henry VII in 1499 could be rediscovered on the site of Bisham Priory, DNA research (similar to my 2004 discovery which prompted the search for, and subsequent identification of, the remains of Richard III) could potentially be used to clarify the truth.

John Ashdown-Hill is a freelance historian with a PhD in history. His book, The Dublin King: The True Story of Edward Earl of Warwick, Lambert Simnel and the 'Princes in the Tower' is published by The History Press.

Published on June 17, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Battle of Deptford Bridge

June 17

1497 Cornish Rebellion - Battle of Deptford Bridge – forces under King Henry VII defeated troops led by Michael An Gof.

1497 Cornish Rebellion - Battle of Deptford Bridge – forces under King Henry VII defeated troops led by Michael An Gof.

Published on June 17, 2016 02:00

June 16, 2016

7 medieval kings you should know about

History Extra

A 13th-century manuscript illumination depicting a coronation. The king is believed to be King Edward II. (Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images) Richard I Despite being one of England’s most iconic medieval kings, Richard I (r1189–99) spent only six months of his decade-long reign on English soil and may not have even spoken English. His energies were undoubtedly focused towards international war-mongering rather than affairs within England itself. Writing for History Extra, Andrew Gimson argues that Richard’s “only use for England” was to raise money through taxes in order to wage war abroad. As his epithet ‘Lionheart’ suggests, Richard boasted a reputation as a fearless warrior king. He is best remembered for his efforts in the Third Crusade, a religious campaign to reclaim the Holy Land from the Muslim sultan and military leader Saladin. On the battlefield, Richard was a strong commander and renowned military tactician. Although he is often portrayed as the stereotypical chivalric medieval knight, Richard’s actions in the Middle East were often far from gallant and honourable by modern standards. Following a dispute over the city of Acre in 1191 he ordered the killing of 2,700 Muslim prisoners, including women and children. Yet despite several victories in the Holy Land, Richard never achieved his ultimate aim of conquering Jerusalem for the glory of western Christendom. Following infighting with other European crusade forces and a year-long stalemate, he made a truce with his opponent Saladin. After years of pouring the nation’s finances and men into the crusade, he was forced to concede failure and head back towards England. Yet the king’s route home was far from simple. On his return to Europe, Richard was captured and handed over to German king and Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI. Henry ransomed Richard, demanding a crippling payment of 150,000 marks from England for his return. This return was short-lived however, as Richard headed straight back out to the battlefields of Normandy and Aquitaine. He led successful campaigns there for a further five years before being mortally wounded by a crossbow bolt during a siege battle.

A 13th-century manuscript illumination depicting a coronation. The king is believed to be King Edward II. (Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images) Richard I Despite being one of England’s most iconic medieval kings, Richard I (r1189–99) spent only six months of his decade-long reign on English soil and may not have even spoken English. His energies were undoubtedly focused towards international war-mongering rather than affairs within England itself. Writing for History Extra, Andrew Gimson argues that Richard’s “only use for England” was to raise money through taxes in order to wage war abroad. As his epithet ‘Lionheart’ suggests, Richard boasted a reputation as a fearless warrior king. He is best remembered for his efforts in the Third Crusade, a religious campaign to reclaim the Holy Land from the Muslim sultan and military leader Saladin. On the battlefield, Richard was a strong commander and renowned military tactician. Although he is often portrayed as the stereotypical chivalric medieval knight, Richard’s actions in the Middle East were often far from gallant and honourable by modern standards. Following a dispute over the city of Acre in 1191 he ordered the killing of 2,700 Muslim prisoners, including women and children. Yet despite several victories in the Holy Land, Richard never achieved his ultimate aim of conquering Jerusalem for the glory of western Christendom. Following infighting with other European crusade forces and a year-long stalemate, he made a truce with his opponent Saladin. After years of pouring the nation’s finances and men into the crusade, he was forced to concede failure and head back towards England. Yet the king’s route home was far from simple. On his return to Europe, Richard was captured and handed over to German king and Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI. Henry ransomed Richard, demanding a crippling payment of 150,000 marks from England for his return. This return was short-lived however, as Richard headed straight back out to the battlefields of Normandy and Aquitaine. He led successful campaigns there for a further five years before being mortally wounded by a crossbow bolt during a siege battle.  Richard I unhorsing Saladin during the Third Crusade. (Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images) King John History has not been kind to King John (r1199–1216). He is most frequently remembered as the cruel and greedy villain of the Robin Hood legend, who attempted to usurp his beloved brother Richard, backtracked on Magna Carta and threw England into civil war. In 1193, John gained his reputation as a usurper by unsuccessfully attempting to seize the throne while his elder brother King Richard I was imprisoned in Germany. After this plot failed, John was subsequently banished. In 1199, following the brothers’ reconciliation and Richard’s death, John finally gained the throne by legitimate means. John’s reign was marred by rebellion and discontent, and he faced significant antagonism from both outside and inside of England. War with France cost him dearly – he lost large amounts of money and land, including Normandy, Anjou and Maine. Taxes to fund the war grew enormous and the situation significantly damaged John’s reputation. The king’s attempts to quash opposition at home proved equally unsuccessful. By 1215, discontent within England had reached breaking point, and John was forced into a civil war with rebel barons. He was consequently compelled to agree to Magna Carta, a peace treaty that would go on to be recognised as one of the founding documents of the English legal system. By sealing Magna Carta, John dealt a huge blow to the power and prestige of the monarchy, as the document asserted that no man was above the law, not even a king. However, the king was quick to backtrack on the democratic promises of the treaty, arguing he was forced to concede to its terms under duress. England was plunged back into civil war. The future French king Louis invaded at the request of the barons, and John was condemned as a coward for fleeing from the French invaders. Peace was only negotiated following John’s death in 1216.

Richard I unhorsing Saladin during the Third Crusade. (Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images) King John History has not been kind to King John (r1199–1216). He is most frequently remembered as the cruel and greedy villain of the Robin Hood legend, who attempted to usurp his beloved brother Richard, backtracked on Magna Carta and threw England into civil war. In 1193, John gained his reputation as a usurper by unsuccessfully attempting to seize the throne while his elder brother King Richard I was imprisoned in Germany. After this plot failed, John was subsequently banished. In 1199, following the brothers’ reconciliation and Richard’s death, John finally gained the throne by legitimate means. John’s reign was marred by rebellion and discontent, and he faced significant antagonism from both outside and inside of England. War with France cost him dearly – he lost large amounts of money and land, including Normandy, Anjou and Maine. Taxes to fund the war grew enormous and the situation significantly damaged John’s reputation. The king’s attempts to quash opposition at home proved equally unsuccessful. By 1215, discontent within England had reached breaking point, and John was forced into a civil war with rebel barons. He was consequently compelled to agree to Magna Carta, a peace treaty that would go on to be recognised as one of the founding documents of the English legal system. By sealing Magna Carta, John dealt a huge blow to the power and prestige of the monarchy, as the document asserted that no man was above the law, not even a king. However, the king was quick to backtrack on the democratic promises of the treaty, arguing he was forced to concede to its terms under duress. England was plunged back into civil war. The future French king Louis invaded at the request of the barons, and John was condemned as a coward for fleeing from the French invaders. Peace was only negotiated following John’s death in 1216.  A 14th-century image of King John, one of medieval England’s most unpopular monarchs, hunting on horseback. (Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images) Edward I Known as ‘Longshanks’ due to his tall stature, the Plantagenet king Edward I (r1272–1307) is often credited with beginning the unification process of the British Isles. This process was far from peaceful however – Edward led a harsh campaign of suppression in order to force Wales and Scotland to bend to English will. Edward’s troubles in Wales began when the Prince of Wales, Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, refused to pay homage to him. In response, Edward chose to force Wales and its leaders into submission, building a chain of castles along the Welsh north coast in order to block supplies into the region. Welsh hopes of independence were quashed and the country was conquered. After Llywelyn’s defeat in battle in 1282, Edward later bequeathed the title of Prince of Wales upon his own son – a tradition that still remains today. Known as the ‘Hammer of the Scots’, Edward also led major campaigns in Scotland, including a successful invasion of the country in 1296. He faced significant rebellions from the Scots, including William Wallace (whose execution he ordered in 1305) and, later, Robert the Bruce. After Edward’s death his land gains in Scotland were quickly lost by his son Edward II. Alongside this aggressive foreign policy, Longshanks was also responsible for tackling corruption and significantly reforming England’s administrative and legal systems. His extensive military ventures required considerable financial backing – money that ultimately came from the pockets of his heavily taxed subjects. One result of this increased taxation was an increase in parliamentary meetings. Another was the persecution of England’s Jewish money-lenders, and in turn, Jews in general. After executing 300 Jews in the Tower of London, in 1290 Edward expelled all Jews from the country.

A 14th-century image of King John, one of medieval England’s most unpopular monarchs, hunting on horseback. (Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images) Edward I Known as ‘Longshanks’ due to his tall stature, the Plantagenet king Edward I (r1272–1307) is often credited with beginning the unification process of the British Isles. This process was far from peaceful however – Edward led a harsh campaign of suppression in order to force Wales and Scotland to bend to English will. Edward’s troubles in Wales began when the Prince of Wales, Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, refused to pay homage to him. In response, Edward chose to force Wales and its leaders into submission, building a chain of castles along the Welsh north coast in order to block supplies into the region. Welsh hopes of independence were quashed and the country was conquered. After Llywelyn’s defeat in battle in 1282, Edward later bequeathed the title of Prince of Wales upon his own son – a tradition that still remains today. Known as the ‘Hammer of the Scots’, Edward also led major campaigns in Scotland, including a successful invasion of the country in 1296. He faced significant rebellions from the Scots, including William Wallace (whose execution he ordered in 1305) and, later, Robert the Bruce. After Edward’s death his land gains in Scotland were quickly lost by his son Edward II. Alongside this aggressive foreign policy, Longshanks was also responsible for tackling corruption and significantly reforming England’s administrative and legal systems. His extensive military ventures required considerable financial backing – money that ultimately came from the pockets of his heavily taxed subjects. One result of this increased taxation was an increase in parliamentary meetings. Another was the persecution of England’s Jewish money-lenders, and in turn, Jews in general. After executing 300 Jews in the Tower of London, in 1290 Edward expelled all Jews from the country.  The Great Seal of Edward I, who was also known as ‘Longshanks’ and the ‘Hammer of the Scots’. (Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images) Edward II Edward II (r1307–1327) has been widely accepted as both an unpopular king and inept military leader, whose reign was characterised by conflict and poor decision-making. Writing for History Extra, Kathryn Warner said that Edward’s reign “lurched from one crisis to another: endless conflict with his barons, constant threats of civil war, and failed military campaigns.” One of Edward’s infamous failures was losing the significant military gains his father had made in Scotland. The defeat of his forces at the hands of Robert the Bruce at the battle of Bannockburn was a humiliation that helped secure Scottish independence from English rule. Edward was an unconventional monarch personally as well as politically, reportedly revelling in the company of peasant labourers, fishermen and carpenters. Throughout his life, Edward alienated many of England’s barons by promoting unsuitable and unpopular personal favourites, who were widely believed to hold a negative influence over him. First came Piers Gaveston, whom the barons hated so much that they repeatedly banished him before executing him in 1312. Edward later shifted his favour to Hugh le Despenser and his son, sharing significant power with the pair and supporting their campaigns in Wales. This was an immensely unpopular decision that would prove fatal to Edward’s reign. Civil war broke out and Edward found himself devoid of supporters. The final nail in Edward’s coffin proved to be a coup led by his own wife, Queen Isabella of France (who despised the Despensers) and her lover Roger Mortimer. In 1326, the pair invaded England, successfully deposing Edward II and placing his teenage son (Edward III) on the throne. Following his humiliating downfall, Edward was imprisoned at Berkeley Castle in 1327, where it is generally accepted he was murdered. According to a popular and enduring myth, the former king was killed in grisly fashion with a red-hot poker.

The Great Seal of Edward I, who was also known as ‘Longshanks’ and the ‘Hammer of the Scots’. (Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images) Edward II Edward II (r1307–1327) has been widely accepted as both an unpopular king and inept military leader, whose reign was characterised by conflict and poor decision-making. Writing for History Extra, Kathryn Warner said that Edward’s reign “lurched from one crisis to another: endless conflict with his barons, constant threats of civil war, and failed military campaigns.” One of Edward’s infamous failures was losing the significant military gains his father had made in Scotland. The defeat of his forces at the hands of Robert the Bruce at the battle of Bannockburn was a humiliation that helped secure Scottish independence from English rule. Edward was an unconventional monarch personally as well as politically, reportedly revelling in the company of peasant labourers, fishermen and carpenters. Throughout his life, Edward alienated many of England’s barons by promoting unsuitable and unpopular personal favourites, who were widely believed to hold a negative influence over him. First came Piers Gaveston, whom the barons hated so much that they repeatedly banished him before executing him in 1312. Edward later shifted his favour to Hugh le Despenser and his son, sharing significant power with the pair and supporting their campaigns in Wales. This was an immensely unpopular decision that would prove fatal to Edward’s reign. Civil war broke out and Edward found himself devoid of supporters. The final nail in Edward’s coffin proved to be a coup led by his own wife, Queen Isabella of France (who despised the Despensers) and her lover Roger Mortimer. In 1326, the pair invaded England, successfully deposing Edward II and placing his teenage son (Edward III) on the throne. Following his humiliating downfall, Edward was imprisoned at Berkeley Castle in 1327, where it is generally accepted he was murdered. According to a popular and enduring myth, the former king was killed in grisly fashion with a red-hot poker.  King Edward II, who was deposed by his wife, Isabella of France. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Henry V Although he went on to become one of the most famous monarchs in English history, Henry V (r1413–1422) was not initially intended for the throne. Aged 13, his fate was transformed by the actions of his father Henry Bolingbroke, who usurped the then king, Richard II, and seized the throne for his own dynastic line. Henry began developing his promising military skills as a teenager. In 1403, he proved a strong commander, leading troops in the battle of Shrewsbury. He was just 16 at the time, and was shot in the face with an arrow that pierced his cheek. Henry also led significant campaigns to help his father tackle Welsh rebellion. His hands-on role as Prince of Wales was not all smooth sailing however, as his passionate involvement in policy-making led to heated disputes with his father. By the time Henry inherited the throne in 1413, he was itching to reclaim lost French territories – something that his father had resisted for several years. After swiftly quashing an attempted coup by rival Edmund Mortimer, his first key action as king was to launch a major attack on France. Henry’s finest hour has commonly been seen as his defeat of the French at Agincourt in 1415. It is for this victory that he is best remembered – perhaps largely due to the rousing immortalisation of this moment in Shakespeare’s Henry V. Victory at Agincourt led to further triumphs in France – Henry went on to conquer Normandy and Rouen. In 1420, these victories culminated in the Treaty of Troyes, which recognised Henry as heir to the French throne. Yet only two years later, the all-conquering king met an unpleasant end. In 1422, he died suddenly after contracting dysentery at the siege of Meaux.

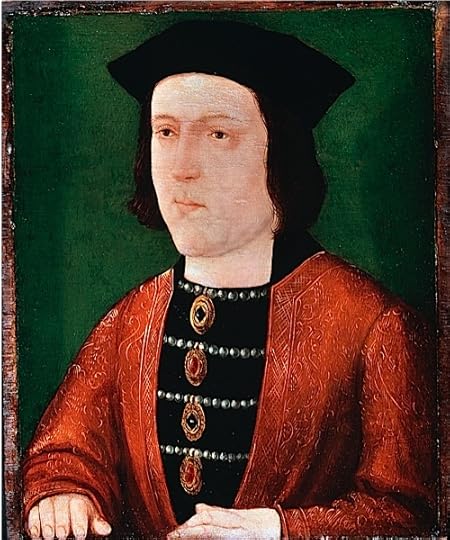

King Edward II, who was deposed by his wife, Isabella of France. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Henry V Although he went on to become one of the most famous monarchs in English history, Henry V (r1413–1422) was not initially intended for the throne. Aged 13, his fate was transformed by the actions of his father Henry Bolingbroke, who usurped the then king, Richard II, and seized the throne for his own dynastic line. Henry began developing his promising military skills as a teenager. In 1403, he proved a strong commander, leading troops in the battle of Shrewsbury. He was just 16 at the time, and was shot in the face with an arrow that pierced his cheek. Henry also led significant campaigns to help his father tackle Welsh rebellion. His hands-on role as Prince of Wales was not all smooth sailing however, as his passionate involvement in policy-making led to heated disputes with his father. By the time Henry inherited the throne in 1413, he was itching to reclaim lost French territories – something that his father had resisted for several years. After swiftly quashing an attempted coup by rival Edmund Mortimer, his first key action as king was to launch a major attack on France. Henry’s finest hour has commonly been seen as his defeat of the French at Agincourt in 1415. It is for this victory that he is best remembered – perhaps largely due to the rousing immortalisation of this moment in Shakespeare’s Henry V. Victory at Agincourt led to further triumphs in France – Henry went on to conquer Normandy and Rouen. In 1420, these victories culminated in the Treaty of Troyes, which recognised Henry as heir to the French throne. Yet only two years later, the all-conquering king met an unpleasant end. In 1422, he died suddenly after contracting dysentery at the siege of Meaux.  Henry V, famous for his victory at the battle of Agincourt. (Culture Club/Getty Images) Edward IV A major player in the Wars of the Roses, Edward IV (r1461–1470 and 1471–83) is best known for leading Yorkist efforts to claim England’s throne and for his unconventional choice of bride. Edward came from the Yorkist branch of the Plantagenet dynasty – his claim to the throne derived from the fact that his parents were descendants of Edward III. Although England had been ruled by the opposing Plantagenet faction, the Lancastrians, since 1399, Lancastrian king Henry VI’s grip over England was weakening. With the support of the Earl of Warwick, known as ‘The Kingmaker’, Edward made a bid for the throne. After a series of victories including the 1461 battle of Towton, he succeeded in overthrowing Henry VI and was crowned king. Historian Amy Licence describes the young Edward as being “charismatic, tall and handsome, renowned for his love affairs and athleticism.” Yet, one of these love affairs was to prove intensely politically problematic, ultimately plunging England back into civil war. In 1464 Edward secretly married Elizabeth Woodville. Woodville was a highly controversial choice of bride for Edward. Not only was she a Lancastrian, a widow and a mother – she was also a commoner. The marriage undermined attempts to secure a politically advantageous French match for Edward and saw Woodville’s relatives given enviable royal favour. The ramifications of Edward’s decision were huge, as it lost him the support of Warwick. The angered earl proved to be a dangerous ally to alienate – he transferred his allegiances to the exiled former king Henry VI, fuelling a strong Lancastrian revolt against Edward. Faced with deposition and death, Edward made a swift escape to the Netherlands. After six months in exile, he launched a remarkable comeback. With only a small force, he crushed his rivals, defeating Warwick in battle, imprisoning Henry in the Tower and reinstating himself on the throne. Edward’s second reign proved a much more sedate and stable period than his first. Although he was still involved in conflict, tackling a revolt by his brother and launching an invasion of France, these events passed relatively smoothly until Edward’s sudden death aged 40 in 1483.

Henry V, famous for his victory at the battle of Agincourt. (Culture Club/Getty Images) Edward IV A major player in the Wars of the Roses, Edward IV (r1461–1470 and 1471–83) is best known for leading Yorkist efforts to claim England’s throne and for his unconventional choice of bride. Edward came from the Yorkist branch of the Plantagenet dynasty – his claim to the throne derived from the fact that his parents were descendants of Edward III. Although England had been ruled by the opposing Plantagenet faction, the Lancastrians, since 1399, Lancastrian king Henry VI’s grip over England was weakening. With the support of the Earl of Warwick, known as ‘The Kingmaker’, Edward made a bid for the throne. After a series of victories including the 1461 battle of Towton, he succeeded in overthrowing Henry VI and was crowned king. Historian Amy Licence describes the young Edward as being “charismatic, tall and handsome, renowned for his love affairs and athleticism.” Yet, one of these love affairs was to prove intensely politically problematic, ultimately plunging England back into civil war. In 1464 Edward secretly married Elizabeth Woodville. Woodville was a highly controversial choice of bride for Edward. Not only was she a Lancastrian, a widow and a mother – she was also a commoner. The marriage undermined attempts to secure a politically advantageous French match for Edward and saw Woodville’s relatives given enviable royal favour. The ramifications of Edward’s decision were huge, as it lost him the support of Warwick. The angered earl proved to be a dangerous ally to alienate – he transferred his allegiances to the exiled former king Henry VI, fuelling a strong Lancastrian revolt against Edward. Faced with deposition and death, Edward made a swift escape to the Netherlands. After six months in exile, he launched a remarkable comeback. With only a small force, he crushed his rivals, defeating Warwick in battle, imprisoning Henry in the Tower and reinstating himself on the throne. Edward’s second reign proved a much more sedate and stable period than his first. Although he was still involved in conflict, tackling a revolt by his brother and launching an invasion of France, these events passed relatively smoothly until Edward’s sudden death aged 40 in 1483.  An image of Yorkist king Edward IV from 1540. (Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images) Richard III Undoubtedly the most hotly debated of all England’s medieval monarchs, Richard III (r1483–85) has continually fascinated both academics and the public alike. The discovery of the body of the ‘king in the carpark’ in September 2012 fuelled even greater debate over Richard’s reign. Was he a usurping murderer, or a misunderstood monarch? Following the death of his brother King Edward IV, Richard was appointed protector of the realm and charged with safeguarding the underage king – his 12-year-old nephew Edward V. Aspersions were cast on the legitimacy of the young king and his brother and in June 1483, Richard assumed the role of king. Shortly afterwards, the princes (later known as the ‘princes in the Tower’) mysteriously disappeared while in Richard’s care, leading to pervasive rumours that their usurping uncle had murdered them. While these claims have not been comprehensively proven, the princes’ disappearance conveniently eliminated any future threat they could pose to Richard’s rule. Nevertheless, Richard’s grip on England quickly disintegrated, as former allies began to defect. In August 1485, just two years after he had been crowned, Richard’s reign was dealt the final blow. A Lancastrian claimant to the throne, Henry Tudor, launched an attack on England. He came to blows with Richard at the battle of Bosworth. At the outset, Richard’s chances at Bosworth looked promising. He outnumbered Henry Tudor’s forces three to one and was reportedly so confident of victory that he was “overjoyed” at the chance to take on his rival. However, Richard’s advantage was undermined by the defection of several of his main supporters and he met with a devastating defeat. After reportedly refusing to flee, he was killed on the battlefield. Richard’s death at Bosworth heralded the end of the medieval era. Decades of fighting in the Wars of the Roses were drawing to a close, as a new royal dynasty came to prominence – the Tudors.

An image of Yorkist king Edward IV from 1540. (Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images) Richard III Undoubtedly the most hotly debated of all England’s medieval monarchs, Richard III (r1483–85) has continually fascinated both academics and the public alike. The discovery of the body of the ‘king in the carpark’ in September 2012 fuelled even greater debate over Richard’s reign. Was he a usurping murderer, or a misunderstood monarch? Following the death of his brother King Edward IV, Richard was appointed protector of the realm and charged with safeguarding the underage king – his 12-year-old nephew Edward V. Aspersions were cast on the legitimacy of the young king and his brother and in June 1483, Richard assumed the role of king. Shortly afterwards, the princes (later known as the ‘princes in the Tower’) mysteriously disappeared while in Richard’s care, leading to pervasive rumours that their usurping uncle had murdered them. While these claims have not been comprehensively proven, the princes’ disappearance conveniently eliminated any future threat they could pose to Richard’s rule. Nevertheless, Richard’s grip on England quickly disintegrated, as former allies began to defect. In August 1485, just two years after he had been crowned, Richard’s reign was dealt the final blow. A Lancastrian claimant to the throne, Henry Tudor, launched an attack on England. He came to blows with Richard at the battle of Bosworth. At the outset, Richard’s chances at Bosworth looked promising. He outnumbered Henry Tudor’s forces three to one and was reportedly so confident of victory that he was “overjoyed” at the chance to take on his rival. However, Richard’s advantage was undermined by the defection of several of his main supporters and he met with a devastating defeat. After reportedly refusing to flee, he was killed on the battlefield. Richard’s death at Bosworth heralded the end of the medieval era. Decades of fighting in the Wars of the Roses were drawing to a close, as a new royal dynasty came to prominence – the Tudors.  A painting of Richard III, by an anonymous artist. (Apic/Getty Images)

A painting of Richard III, by an anonymous artist. (Apic/Getty Images)

Published on June 16, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Mary, Queen of Scots, imprisoned in Lochleven Castle

June 16

1567 Mary, Queen of Scots, was imprisoned in Lochleven Castle prison Scotland since she was perceived as a threat to Elizabeth I's monarchy.

1567 Mary, Queen of Scots, was imprisoned in Lochleven Castle prison Scotland since she was perceived as a threat to Elizabeth I's monarchy.

Published on June 16, 2016 02:00