MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 96

June 6, 2016

Deep in a Cave in France Neanderthals Constructed Mysterious Ring Structures 176,000 Years Ago

Ancient Origins

Not a lot is known about the Neanderthals, but researchers say circular arrangements of 176,000-year-old stalagmites in a cave in France shows they were carrying out some kind of cultural or geometric representations tens of thousands of years before modern Homo sapiens entered Europe. These structures are unlike anything found previously by archaeologists or anything known from history.

A team of researchers analyzed stalagmites and burnt bones from Bruniquel Cave in France’s Averyron region and found they dated to about 140,000 years before their cousins (we modern humans) arrived on the scene.

Rock Shelter, Bruniquel. Antique wood engraved print. Date of printing 1890. From

'Peoples of the world

' by Robert Brown, published by Cassel & Co. Led by Jacques Jaubert of the University of Bordeaux, the large group of researchers reported their findings in the journal Nature.

Rock Shelter, Bruniquel. Antique wood engraved print. Date of printing 1890. From

'Peoples of the world

' by Robert Brown, published by Cassel & Co. Led by Jacques Jaubert of the University of Bordeaux, the large group of researchers reported their findings in the journal Nature.

“The regular geometry of the stalagmite circles, the arrangement of broken stalagmites and several traces of fire demonstrate the anthropogenic origin of these constructions,” they wrote. “What was the function of these structures at such a great distance from the cave entrance? Why are most of the fireplaces found on the structures rather than directly on the cave floor? Based on most Upper Palaeolithic cave incursions, we could assume that they represent some kind of symbolic or ritual behavior, but could they rather have served for an unknown domestic use or simply as a refuge? Future research will try to answer these questions.”

Bruniquel Cave closed naturally during the Pleistocene Epoch, which ended about 10,000 years ago, and had not been disturbed since people discovered it in 1990. The cave is in southwest France. Spelunkers dug a narrow chamber through 30 meters (about 100 feet) of earth at the entrance to reach the cave’s interior.

The Cavern of Bruniquel, briefly noticed by Marcel de Serres in the subjoined passage from his work 'Sur les Cavernes a Ossemens', is situated in a grand escarpment of the Jurassic limestone bordering the river Aveyron, opposite the village of Bruniquel. Image and text:

Owen (1864)

The stalagmite arrangements are 336 meters (1,100 feet) from the entrance. The cave has many speleothems, or minerals deposited by the action of water.

The Cavern of Bruniquel, briefly noticed by Marcel de Serres in the subjoined passage from his work 'Sur les Cavernes a Ossemens', is situated in a grand escarpment of the Jurassic limestone bordering the river Aveyron, opposite the village of Bruniquel. Image and text:

Owen (1864)

The stalagmite arrangements are 336 meters (1,100 feet) from the entrance. The cave has many speleothems, or minerals deposited by the action of water.

“The regular geometry of the stalagmite circles, the arrangement of broken stalagmites and several traces of fire demonstrate the anthropogenic origin of these constructions,” the authors wrote. They said they are among the oldest-known human-arranged structures.

The two rings and six piles of stalagmites range from a diameter of a half-meter (1.8 feet) to 2.6 m (8.53 feet). The stalagmites, about 400 of them, are both whole and broken and are close in size, ranging from 29.5 to 34.4 cm (11.614 inches to 13.543 inches). Altogether, the stalagmites weigh about 2.4 tons.

The scientists made a 3D reconstruction of the manmade structures.The Neanderthals burned fires inside the stalagmite rings only, not outside, a practice that puzzled the researchers. But the extinct Neanderthals were the first to use fire, about 800,000 years ago. The article states:

The scientists made a 3D reconstruction of the manmade structures.The Neanderthals burned fires inside the stalagmite rings only, not outside, a practice that puzzled the researchers. But the extinct Neanderthals were the first to use fire, about 800,000 years ago. The article states:

Another thing that is different about this find as opposed to others from the Paleolithic is that people, even in Africa, have not been known to live deep in caves, though during the Late Stone Age various people were living in cave entrances. The earliest known use of deep cave use previously, also in France in Chauvet Cave, was about 36,000 years ago. There, hominids of some type made beautiful cave paintings.

Chauvet cave paintings (

public domain

)Neanderthals are modern humans’ closest extinct relatives. They evolved about 400,000 years ago and died out around 40,000 years ago, scientists have estimated. They lived in Europe and western and central Asia. Their brains were about equal in size to or even a bit larger than Homo sapiens’ brains.

Chauvet cave paintings (

public domain

)Neanderthals are modern humans’ closest extinct relatives. They evolved about 400,000 years ago and died out around 40,000 years ago, scientists have estimated. They lived in Europe and western and central Asia. Their brains were about equal in size to or even a bit larger than Homo sapiens’ brains.

Neanderthals used tools, lived in shelters and made clothing. They hunted large animals and also ate plants. They also fashioned ornamental or symbolic artifacts.

“There is evidence that Neanderthals deliberately buried their dead and occasionally even marked their graves with offerings, such as flowers. No other primates, and no earlier human species, had ever practiced this sophisticated and symbolic behavior,” says the Smithsonian.

The U.S. government’s National Institutes of Health genome department finished sequencing the entire Neanderthal genome in 2010 (article).

Top image: Archaeologists say the circular structures discovered deep in a cave in southwestern France were constructed by Neanderthals 176,000 years ago. (Etienne Fabre / SSAC)

By Mark Miller

Not a lot is known about the Neanderthals, but researchers say circular arrangements of 176,000-year-old stalagmites in a cave in France shows they were carrying out some kind of cultural or geometric representations tens of thousands of years before modern Homo sapiens entered Europe. These structures are unlike anything found previously by archaeologists or anything known from history.

A team of researchers analyzed stalagmites and burnt bones from Bruniquel Cave in France’s Averyron region and found they dated to about 140,000 years before their cousins (we modern humans) arrived on the scene.

Rock Shelter, Bruniquel. Antique wood engraved print. Date of printing 1890. From

'Peoples of the world

' by Robert Brown, published by Cassel & Co. Led by Jacques Jaubert of the University of Bordeaux, the large group of researchers reported their findings in the journal Nature.

Rock Shelter, Bruniquel. Antique wood engraved print. Date of printing 1890. From

'Peoples of the world

' by Robert Brown, published by Cassel & Co. Led by Jacques Jaubert of the University of Bordeaux, the large group of researchers reported their findings in the journal Nature.“The regular geometry of the stalagmite circles, the arrangement of broken stalagmites and several traces of fire demonstrate the anthropogenic origin of these constructions,” they wrote. “What was the function of these structures at such a great distance from the cave entrance? Why are most of the fireplaces found on the structures rather than directly on the cave floor? Based on most Upper Palaeolithic cave incursions, we could assume that they represent some kind of symbolic or ritual behavior, but could they rather have served for an unknown domestic use or simply as a refuge? Future research will try to answer these questions.”

Bruniquel Cave closed naturally during the Pleistocene Epoch, which ended about 10,000 years ago, and had not been disturbed since people discovered it in 1990. The cave is in southwest France. Spelunkers dug a narrow chamber through 30 meters (about 100 feet) of earth at the entrance to reach the cave’s interior.

The Cavern of Bruniquel, briefly noticed by Marcel de Serres in the subjoined passage from his work 'Sur les Cavernes a Ossemens', is situated in a grand escarpment of the Jurassic limestone bordering the river Aveyron, opposite the village of Bruniquel. Image and text:

Owen (1864)

The stalagmite arrangements are 336 meters (1,100 feet) from the entrance. The cave has many speleothems, or minerals deposited by the action of water.

The Cavern of Bruniquel, briefly noticed by Marcel de Serres in the subjoined passage from his work 'Sur les Cavernes a Ossemens', is situated in a grand escarpment of the Jurassic limestone bordering the river Aveyron, opposite the village of Bruniquel. Image and text:

Owen (1864)

The stalagmite arrangements are 336 meters (1,100 feet) from the entrance. The cave has many speleothems, or minerals deposited by the action of water.“The regular geometry of the stalagmite circles, the arrangement of broken stalagmites and several traces of fire demonstrate the anthropogenic origin of these constructions,” the authors wrote. They said they are among the oldest-known human-arranged structures.

The two rings and six piles of stalagmites range from a diameter of a half-meter (1.8 feet) to 2.6 m (8.53 feet). The stalagmites, about 400 of them, are both whole and broken and are close in size, ranging from 29.5 to 34.4 cm (11.614 inches to 13.543 inches). Altogether, the stalagmites weigh about 2.4 tons.

The scientists made a 3D reconstruction of the manmade structures.The Neanderthals burned fires inside the stalagmite rings only, not outside, a practice that puzzled the researchers. But the extinct Neanderthals were the first to use fire, about 800,000 years ago. The article states:

The scientists made a 3D reconstruction of the manmade structures.The Neanderthals burned fires inside the stalagmite rings only, not outside, a practice that puzzled the researchers. But the extinct Neanderthals were the first to use fire, about 800,000 years ago. The article states:“A critical review of all known remains of fire in Europe concluded that Neanderthals were the first to commonly use fire, and in particular at the end of the Middle Pleistocene when they began to cook and produce new materials such as organic glue and haft tools.”The article said that the Neanderthals carried out tasks to arrange the circles, which points to social organization. The elaborateness of the circles, plus the fact that the stalagmites are partially calibrated (deliberately sized), plus the heated zones, indicate a level of social organization that researchers did not think Neanderthals were capable of, the article states.

Another thing that is different about this find as opposed to others from the Paleolithic is that people, even in Africa, have not been known to live deep in caves, though during the Late Stone Age various people were living in cave entrances. The earliest known use of deep cave use previously, also in France in Chauvet Cave, was about 36,000 years ago. There, hominids of some type made beautiful cave paintings.

Chauvet cave paintings (

public domain

)Neanderthals are modern humans’ closest extinct relatives. They evolved about 400,000 years ago and died out around 40,000 years ago, scientists have estimated. They lived in Europe and western and central Asia. Their brains were about equal in size to or even a bit larger than Homo sapiens’ brains.

Chauvet cave paintings (

public domain

)Neanderthals are modern humans’ closest extinct relatives. They evolved about 400,000 years ago and died out around 40,000 years ago, scientists have estimated. They lived in Europe and western and central Asia. Their brains were about equal in size to or even a bit larger than Homo sapiens’ brains.Neanderthals used tools, lived in shelters and made clothing. They hunted large animals and also ate plants. They also fashioned ornamental or symbolic artifacts.

“There is evidence that Neanderthals deliberately buried their dead and occasionally even marked their graves with offerings, such as flowers. No other primates, and no earlier human species, had ever practiced this sophisticated and symbolic behavior,” says the Smithsonian.

The U.S. government’s National Institutes of Health genome department finished sequencing the entire Neanderthal genome in 2010 (article).

Top image: Archaeologists say the circular structures discovered deep in a cave in southwestern France were constructed by Neanderthals 176,000 years ago. (Etienne Fabre / SSAC)

By Mark Miller

Published on June 06, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Battle of Novara

June 6

1513 Italian Wars: Battle of Novara. Swiss troops defeated the French under Louis de la Tremoille, forcing the French to abandon Milan. Duke Massimiliano Sforza was restored.

1513 Italian Wars: Battle of Novara. Swiss troops defeated the French under Louis de la Tremoille, forcing the French to abandon Milan. Duke Massimiliano Sforza was restored.

Published on June 06, 2016 02:00

June 5, 2016

Archaeologists Claim to have Found Long Lost Tomb of Aristotle

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists in Greece made a surprising announcement today at the International Conference ‘Aristotle 2400 Years’ – the discovery of his long lost tomb. Following a 20-year excavation at the ancient Macedonian city of Stagira, researchers have now concluded that the important tomb belonged to the famous Greek philosopher, who was born in the same city in 384 BC.

Archaeologists in Greece made a surprising announcement today at the International Conference ‘Aristotle 2400 Years’ – the discovery of his long lost tomb. Following a 20-year excavation at the ancient Macedonian city of Stagira, researchers have now concluded that the important tomb belonged to the famous Greek philosopher, who was born in the same city in 384 BC.

Archaeologists Kostas Sismanidis said that, based on the architecture and location of the tomb, as well as other supporting evidence, he can now say with “almost certainty” that the 2,400-year-old tomb belonged to Aristotle. Literary sources also suggest that Aristotle’s ashes were transferred to Stagira, his birthplace.

Village of Olymbiada, Chalkidiki, Greece. View from the northwest including site of ancient Stagira. (

public domain

)

Village of Olymbiada, Chalkidiki, Greece. View from the northwest including site of ancient Stagira. (

public domain

)

The Guardian says that the remains of the ancient complex were first unearthed in 1996 when they were accidentally discovered during construction work ahead of a planned new museum of modern art, and excavations at the site have been ongoing ever since.

Ancient Origins’ writer Natalia Klimczak reports on the famous philosopher:

“Aristotle was born in 384 BC in the city of Stagira, Chalkidice, on the northern periphery of Classical Greece. His father was Nicomachus, who was a doctor, and his mother was Phaestia, who was probably also connected with medicine (although details are unknown.) Apart from Aristotle they had a son named Arimnestus and a daughter named Arimneste. Aristotle’s parents died when he was very young, but he had a guardian who took care of him. Proxenus of Atarneus educated Aristotle for a couple of years before sending him to Athens to Plato's Academy.

Head of Aristotle. Copy of the Imperial era (1st or 2nd century) lost bronze sculpture made by Lysippos. (

public domain

)When Aristotle was eighteen, he joined Plato's Academy in Athens and remained there until the age of thirty-seven. When he left it 347 BC, he became very popular in the capital city of Pella and amongst the nobles.

Head of Aristotle. Copy of the Imperial era (1st or 2nd century) lost bronze sculpture made by Lysippos. (

public domain

)When Aristotle was eighteen, he joined Plato's Academy in Athens and remained there until the age of thirty-seven. When he left it 347 BC, he became very popular in the capital city of Pella and amongst the nobles.

In the beginning, Aristotle contributed to his views of Platonism, but after the death of Plato, he immersed himself in empirical studies and shifted from Platonism to empiricism.

Aristotle believed in concepts and that the knowledge was ultimately based on perception. His views on the natural sciences represent the groundwork underlying many of his philosophies. The writings by Aristotle covered many subjects, including: biology, zoology, metaphysics, psychology, physics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, poetry, theater, music, rhetoric, linguistics, and politics. The results of his analysis created a view on the physical sciences which profoundly shaped medieval scholarship, and the influence of which extended into the Renaissance.

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), a detail of

The School of Athens

, a fresco by

Raphael

. Aristotle gestures to the earth, representing his belief in knowledge through empirical observation and experience, while holding a copy of his

Nicomachean Ethics

in his hand, whilst Plato gestures to the heavens, representing his belief in

The Forms

, while holding a copy of Timaeus (

public domain

)Moreover, they were not replaced systematically until the Enlightenment and theories such as classical mechanics. Many of Aristotle's zoological observations, such as on the reproductive arm of the octopus, were not even confirmed or refuted until the 19th century. Some of his works also contain the earliest known formal study of logic, which in the 19th century became a base for the modern formal logic.”

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), a detail of

The School of Athens

, a fresco by

Raphael

. Aristotle gestures to the earth, representing his belief in knowledge through empirical observation and experience, while holding a copy of his

Nicomachean Ethics

in his hand, whilst Plato gestures to the heavens, representing his belief in

The Forms

, while holding a copy of Timaeus (

public domain

)Moreover, they were not replaced systematically until the Enlightenment and theories such as classical mechanics. Many of Aristotle's zoological observations, such as on the reproductive arm of the octopus, were not even confirmed or refuted until the 19th century. Some of his works also contain the earliest known formal study of logic, which in the 19th century became a base for the modern formal logic.”

Top image: The excavated tomb in Stagira that archaeologists say belongs to Aristotle. Source: Greek Reporter .

Extract included from ‘ Caves in Paradise: The Elite School of Aristotle’ by Natalia Klimczak.

By April Holloway

Archaeologists in Greece made a surprising announcement today at the International Conference ‘Aristotle 2400 Years’ – the discovery of his long lost tomb. Following a 20-year excavation at the ancient Macedonian city of Stagira, researchers have now concluded that the important tomb belonged to the famous Greek philosopher, who was born in the same city in 384 BC.

Archaeologists in Greece made a surprising announcement today at the International Conference ‘Aristotle 2400 Years’ – the discovery of his long lost tomb. Following a 20-year excavation at the ancient Macedonian city of Stagira, researchers have now concluded that the important tomb belonged to the famous Greek philosopher, who was born in the same city in 384 BC.Archaeologists Kostas Sismanidis said that, based on the architecture and location of the tomb, as well as other supporting evidence, he can now say with “almost certainty” that the 2,400-year-old tomb belonged to Aristotle. Literary sources also suggest that Aristotle’s ashes were transferred to Stagira, his birthplace.

Village of Olymbiada, Chalkidiki, Greece. View from the northwest including site of ancient Stagira. (

public domain

)

Village of Olymbiada, Chalkidiki, Greece. View from the northwest including site of ancient Stagira. (

public domain

)“The mounded domed tomb has a marble floor dated to the Hellenistic period,” states the Greek Reporter. “It is located in the center of Stagira, near the Agora, with 360-degree views. The public character of the tomb is evident by its location alone, however archaeologists also point to a hurried construction that was later topped with quality materials. There is an altar outside the tomb and a square-shaped floor. The top of the dome is at 10 meters and there is a square floor surrounding a Byzantine tower. A semi-circle wall stands at two-meters in height. A pathway leads to the tomb’s entrance for those that wished to pay their respects. Other findings included ceramics from the royal pottery workshops and fifty coins dated to the time of Alexander the Great.”Visit the Greek Reporter article for more photographs of the tomb.

The Guardian says that the remains of the ancient complex were first unearthed in 1996 when they were accidentally discovered during construction work ahead of a planned new museum of modern art, and excavations at the site have been ongoing ever since.

Ancient Origins’ writer Natalia Klimczak reports on the famous philosopher:

“Aristotle was born in 384 BC in the city of Stagira, Chalkidice, on the northern periphery of Classical Greece. His father was Nicomachus, who was a doctor, and his mother was Phaestia, who was probably also connected with medicine (although details are unknown.) Apart from Aristotle they had a son named Arimnestus and a daughter named Arimneste. Aristotle’s parents died when he was very young, but he had a guardian who took care of him. Proxenus of Atarneus educated Aristotle for a couple of years before sending him to Athens to Plato's Academy.

Head of Aristotle. Copy of the Imperial era (1st or 2nd century) lost bronze sculpture made by Lysippos. (

public domain

)When Aristotle was eighteen, he joined Plato's Academy in Athens and remained there until the age of thirty-seven. When he left it 347 BC, he became very popular in the capital city of Pella and amongst the nobles.

Head of Aristotle. Copy of the Imperial era (1st or 2nd century) lost bronze sculpture made by Lysippos. (

public domain

)When Aristotle was eighteen, he joined Plato's Academy in Athens and remained there until the age of thirty-seven. When he left it 347 BC, he became very popular in the capital city of Pella and amongst the nobles.In the beginning, Aristotle contributed to his views of Platonism, but after the death of Plato, he immersed himself in empirical studies and shifted from Platonism to empiricism.

Aristotle believed in concepts and that the knowledge was ultimately based on perception. His views on the natural sciences represent the groundwork underlying many of his philosophies. The writings by Aristotle covered many subjects, including: biology, zoology, metaphysics, psychology, physics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, poetry, theater, music, rhetoric, linguistics, and politics. The results of his analysis created a view on the physical sciences which profoundly shaped medieval scholarship, and the influence of which extended into the Renaissance.

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), a detail of

The School of Athens

, a fresco by

Raphael

. Aristotle gestures to the earth, representing his belief in knowledge through empirical observation and experience, while holding a copy of his

Nicomachean Ethics

in his hand, whilst Plato gestures to the heavens, representing his belief in

The Forms

, while holding a copy of Timaeus (

public domain

)Moreover, they were not replaced systematically until the Enlightenment and theories such as classical mechanics. Many of Aristotle's zoological observations, such as on the reproductive arm of the octopus, were not even confirmed or refuted until the 19th century. Some of his works also contain the earliest known formal study of logic, which in the 19th century became a base for the modern formal logic.”

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), a detail of

The School of Athens

, a fresco by

Raphael

. Aristotle gestures to the earth, representing his belief in knowledge through empirical observation and experience, while holding a copy of his

Nicomachean Ethics

in his hand, whilst Plato gestures to the heavens, representing his belief in

The Forms

, while holding a copy of Timaeus (

public domain

)Moreover, they were not replaced systematically until the Enlightenment and theories such as classical mechanics. Many of Aristotle's zoological observations, such as on the reproductive arm of the octopus, were not even confirmed or refuted until the 19th century. Some of his works also contain the earliest known formal study of logic, which in the 19th century became a base for the modern formal logic.”Top image: The excavated tomb in Stagira that archaeologists say belongs to Aristotle. Source: Greek Reporter .

Extract included from ‘ Caves in Paradise: The Elite School of Aristotle’ by Natalia Klimczak.

By April Holloway

Published on June 05, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Siege of Jerusalem

June 5

70 Titus and his Roman legions breached the middle wall of Jerusalem in the Siege of Jerusalem.

70 Titus and his Roman legions breached the middle wall of Jerusalem in the Siege of Jerusalem.

Published on June 05, 2016 02:00

June 4, 2016

A brief history of the Vikings

History Extra

Coins depicting Viking longships, probably minted at Hedeby, Denmark, found in the Viking marketplace at Birka, Sweden. (Photo by Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images) In 793, terror descended on the coast of Northumbria as armed raiders attacked the defenceless monastery of St Cuthbert on Lindisfarne. The terrified monks watched helplessly as the invaders made off with a haul of treasure and a clutch of captives. It was the first recorded raid by the Vikings, seaborne pirates from Scandinavia who would prey on coastal communities in north-western Europe for more than two centuries and create for themselves a reputation as fierce and pitiless warriors.

That image was magnified by those who wrote about the Viking attacks – in other words, their victims. The Anglo-Saxon cleric Alcuin of York wrote dramatically of the Lindisfarne raid that the “church was spattered with the blood of the priests of God, despoiled of all its ornaments… given as a prey to pagan peoples” and subsequent (mainly Christian) writers and chroniclers lost few opportunities to demonise the (mainly pagan) Vikings.

Yet, though they undeniably carried out very destructive and violent attacks, from small-scale raids against churches to major campaigns involving thousands of warriors, the Vikings formed part of a complex and often sophisticated Scandinavian culture. As well as raiders they were traders, reaching as far east as the rivers of Russia and the Caspian Sea; explorers, sending ships far across the Atlantic to land on the coastline of North America five centuries before Columbus; poets, composing verse and prose sagas of great power, and artists, creating works of astonishing beauty.

Viking originsThe Vikings originated in what is now Denmark, Norway and Sweden (although centuries before they became unified countries). Their homeland was overwhelmingly rural, with almost no towns. The vast majority earned a meagre living through agriculture, or along the coast, by fishing. Advances in shipping technology in the 7th and 8th centuries meant that boats were powered by sails rather than solely by oars. These were then added to vessels made of overlapping planks (‘clinker-built’) to create longships, swift shallow-drafted boats that could navigate coastal and inland waters and land on beaches.

Exactly what first compelled bands of men to follow their local chieftain across the North Sea in these longships is unclear. It may have been localised overpopulation, as plots became subdivided to the point where families could barely eke out a living; it may have been political instability, as chieftains fought for dominance; or it may have been news brought home by merchants of the riches to be found in trading settlements further west. Probably it was a combination of all three. But in 793 that first raiding party hit Lindisfarne and within a few years further Viking bands had struck Scotland (794), Ireland (795) and France (799).

Their victims did not refer to them as Vikings. That name came later, becoming popularised by the 11th century and possibly deriving from the word vik, which in the Old Norse language the Vikings spoke means ‘bay’ or ‘inlet’. Instead they were called Dani (‘Danes’) – there was no sense at the time that this should refer only to the inhabitants of what we now call Denmark – pagani (‘pagans’) or simply Normanni (‘Northmen’).

The remains of a Viking longship found at Gokstad in South Norway, c1920. (Photo by Rischgitz/Getty Images)

RaidsAt first the raids were small-scale affairs, a matter of a few boatloads of men who would return home once they had collected sufficient plunder or if the resistance they encountered was too strong. But in the 850s they began to overwinter in southern England, in Ireland and along the Seine in France, establishing bases from which they began to dominate inland areas.

The raids reached a crescendo in the second half of the ninth century. In Ireland the Vikings established longphorts – fortified ports – including at Dublin, from which they dominated much of the eastern part of the island. In France they grew in strength as a divided Frankish kingdom fractured politically and in 885 a Viking army besieged and almost captured Paris.

In Scotland they established an earldom in the Orkneys and overran the Shetlands and the Hebrides. And in England an enormous Viking host, the micel here (‘great army’) arrived in 865. Led by a pair of warrior brothers, Halfdan and Ivar the Boneless, they picked off the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England one by one. First Northumbria, with its capital at York, fell to them in 866, then East Anglia, followed by the central English kingdom of Mercia. Finally, only Wessex, ruled by Alfred, remained. A pious bookworm, Alfred had only become king because his three more martial older brothers had sickened or died in battle in previous Viking invasions.

In early January 878 a section of the Great Army led by Guthrum crossed the frontier and caught Alfred by surprise at the royal estate at Chippenham. Alfred barely managed to escape and spent months skulking in the Somerset marshes at Athelney. It looked like the independence of Wessex – and that of England generally – might be at an end. But against the odds Alfred gathered a new army, defeated the Vikings at Edington and forced Guthrum to accept baptism as a Christian. For his achievement in saving his kingdom he became the only native English ruler to gain the nickname ‘the Great’.

For 80 years England was divided between the land controlled by the kings of Wessex in the south and south-west and a Viking-controlled area in the Midlands and the north. Viking kings ruled this region until the last of them, Erik Bloodaxe, was expelled and killed in 954 and the kings of Wessex became rulers of a united England. Even so, Viking (and especially Danish) customs long persisted there and traces of Scandinavian DNA can still be found in a region that for centuries was known as the Danelaw.

By the mid-11th century united kingdoms had appeared in Denmark, Norway and Sweden and the raids had finally begun to subside. There was a final burst of activity in the early 11th century when royal-sponsored expeditions succeeded in conquering England again and placing Danish kings on the throne there (including, most notably, Canute, who ruled an empire in England, Denmark and Norway, but who almost certainly did not command the tide to go out, as a folk tale alleges). Vikings remained in control of large parts of Scotland (especially Orkney), an area around Dublin and Normandy in France (where in 911 King Charles the Simple had granted land to a Norwegian chieftain, Rollo, the ancestor of William the Conqueror). They also controlled a large part of modern Ukraine and Russia, where Swedish Vikings had penetrated in the ninth century and established states based around Novgorod and Kiev.

Silver penny of King Alfred. The reverse of this coin bears a monogram made up of the letters of LVNDONIA (London), possibly to commemorate the recovery or restoration of London after its occupation by the Danes. (Photo by Museum of London/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

SettlementsThis was not the full extent of the Viking world, however. The same maritime aggression that had caused them to plunder (and ultimately conquer) settled lands also led them to venture in search of unknown shores on which to settle. Vikings probably arrived in the Faroes in the eighth century and they used this as a stepping-stone to sail further west across the Atlantic.

In the mid-ninth century a series of Viking voyages came across Iceland and in the year 872 colonists led by Ingólf Arnarson settled on the island. They established a unique society, fiercely independent and owing no formal allegiance to the kings of Norway. It was a republic whose supreme governing body was, from 930, the Althing, an assembly made up of Iceland’s chief men which met each summer in a plain beside a massive cleft in a ring of hills in the centre of the island. It has a strong claim to be the world’s oldest parliament.

From Iceland, too, we have other vital pieces of evidence of the inventiveness of Viking societies. These include the earliest pieces of history written by Vikings themselves in the form of a 12th-century history of Iceland, the Íslendingabók, and the Landnámabók, an account of the original settlement of the island (with the names of each of the first settlers and the land they took).

But more important – and surprising for those who view of the Vikings is as one-dimensional warriors – is the collection of sagas known as the Íslendingasögur or Icelandic Family Sagas. Their setting is the first 150 years of the Viking colony in Iceland and they tell of often-troubled relations between the main Icelandic families. Alliances, betrayals, feuds and murders play out against the backdrop of a landscape in which features can still often be identified today. At their best, in tales such as Njál’s Saga or Egil’s Saga, they are powerful pieces of literature in their own right, and among the most important writing to survive from any European country in the Middle Ages.

ReligionIceland was the location of another drama that highlights the transition of Viking societies away from warrior chieftainships. Christianity came later to Scandinavian Viking societies than to many other parts of Europe. Whereas France’s kings had accepted Christianity by the early sixth century and the Anglo-Saxon kings of England largely in the seventh, Christian missionaries only appeared in southern Scandinavia in the ninth century and made little headway there until Harald Bluetooth of Denmark accepted baptism in around 960. Harald had become Christian after a typical piece of Viking theatre: a drunken argument around the feasting table as to which was more powerful – Odin and Thor, or the new Christian God and his son, Jesus.

Iceland remained resolutely pagan, loyal to old gods such as Odin; the All Father; a one-eyed god who had sacrificed the other eye in exchange for knowledge of runes; and Thor, the thunder-god with his great hammer Mjölnir, who was also especially popular with warriors.

Iceland became Christian to avoid a civil war. Competing pagan and Christian factions threatened to tear the Althing apart and dissolve Iceland into separate, religiously hostile, states. At the Althing’s meeting in the year 1000 the rival factions appealed to Iceland’s most important official, the lawspeaker Thorgeir Thorkelsson. As a pagan he might have been expected to favour the old gods but, after an entire day spent agonising over the decision, he concluded that henceforth all Icelanders would be Christian. A few exceptions were made – for example the eating of horsemeat, a favoured delicacy that was also associated with pagan sacrifices, was to be permitted.

Detail of a stone relief representing the divine triad: Odin (the chief god in Norse mythology), Thor (god of thunder) and Freyr (god of fertility). Gotland, Sweden. Image c1987. (Photo By DEA/G DAGLI ORTI/De Agostini/Getty Images)

ExplorationsIceland, too, was the platform from which the Vikings launched their furthest-flung explorations. In 982 a fiery tempered chieftain, Erik the Red, who had already been exiled from Norway for his father’s part in a homicide, was then exiled from Iceland for involvement in another murder. He had heard rumours of land to the west and, with a small group of companions, sailed in search of it. What he found was beyond his wildest imaginings. Only 300 kilometres west of Iceland, Greenland is the world’s largest island, and its south and south-west tip had fjords [deep, narrow and elongated sea or lakedrain, with steep land on three sides] and lush pastures that must have reminded Erik of his Scandinavian homeland. He returned back to Iceland, gathered 25 ship-loads of settlers and established a new Viking colony in Greenland that survived into the 15th century.

Erik’s son, Leif, outdid his father. Having heard from another Viking Greenlander, Bjarni Herjolfsson, that he had sighted land even further west, Leif went to see for himself. In around 1002 he and his crew found themselves sailing somewhere along the coast of North America. They found a glacial, mountainous coast, then a wooded one, and finally a country of fertile pastures that they named Vinland. Although they resolved to start a new colony there, it was – unlike either Iceland or Greenland – already settled and hostility from native Americans and their own small numbers (Greenland at the time probably had about 3,000 Viking inhabitants) meant that it was soon abandoned. They had, though, become the first Europeans to land in (and settle in) the Americas, almost five centuries before Christopher Columbus.

For centuries Erik’s achievement lived on only in a pair of sagas, The Saga of the Greenlanders and Erik the Red’s Saga. The location of Vinland, despite attempts to work out where it lay from information contained in the sagas, remained elusive. It was even unclear if the Vikings really had reached North America. Then, in the early 1960s, a Norwegian explorer Helge Ingstad and his archaeologist wife, Anne Stine, found the remains of ancient houses at L’Anse aux Meadows on Newfoundland in Canada. Fragments of worked iron (many of them nails, probably from a ship), which the native population did not possess the technology to produce, meant that it was soon clear this was a Viking settlement. Although perhaps too small to be the main Vinland colony, it was still astonishing confirmation of what the sagas had said. Leif Erikson’s reputation as a great explorer and discoverer of new lands was confirmed without doubt.

This might well have pleased him, for a man’s reputation was everything to a Viking. Quick wit, bravery and action were among the key attributes for a Viking warrior, but to be remembered for great deeds was the most important of all. The Hávamál, a collection of Viking aphorisms, contains much apt advice such as “Never let a bad man know your own bad fortune”, but most famous of all is the saying “Cattle die, kindred die, we ourselves shall die, but I know one thing that never dies: the reputations of each one dead”.

The reputation of the Vikings simply as raiders and plunderers has long been established. Restoring their fame as traders, storytellers, explorers, missionaries, artists and rulers is long overdue.

Philip Parker is author of The Northmen’s Fury: A History of the Viking World (Vintage, 2015).

Published on June 04, 2016 03:00

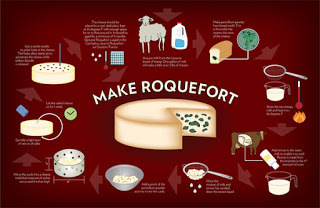

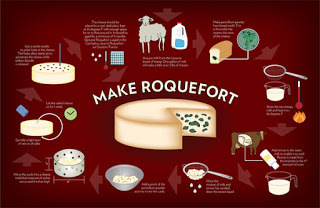

History Trivia - process of making Roquefort cheese discovered

June 4

1070 the process of making Roquefort cheese was discovered by an anonymous shepherd in a cave near Roquefort, France.

1070 the process of making Roquefort cheese was discovered by an anonymous shepherd in a cave near Roquefort, France.

Published on June 04, 2016 02:00

June 3, 2016

8 Vikings you should know about

History Extra

Silver penny of Cnut, who Gareth Williams describes as "the ultimate Viking success story". (Photo by CM Dixon/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Ivarr the BonelessIvarr spans the gap between history and legend. He was a famous warrior and one of the leaders of the ‘Great Heathen Army’ that landed in East Anglia in 865, and that went on to conquer the kingdoms of Northumbria and East Anglia. Ivarr also went on to lead a raid on Dumbarton on the Clyde, and in Ireland.

Later saga tradition makes Ivarr one of the sons of Ragnar Hairy-breeches. According to this account, Ivarr and his brothers invaded Northumbria to take a bloody revenge on its king, Ælle, for the killing of their father.

Although the Great Army continued to campaign in England, Ivarr is not mentioned in English sources after 870 and probably spent the remainder of his career around the Irish Sea. His death is recorded in Irish annals in 873. He was remembered as the founding father of the royal dynasty of the Viking kingdom of Dublin, and his descendants at various points also ruled in other parts of Ireland, Northumbria and the Isle of Man.

The reason for Ivarr’s curious nickname is unknown. One suggestion is simply that he was particularly flexible, giving the illusion of bonelessness, while others have preferred to see it as a metaphor for impotence. Another interpretation is that Ivarr suffered from ‘brittle bone disease’, which seems less plausible given his reputation as a warrior. However, the nickname beinlausi could also be translated as ‘legless’, which might indicate lameness, the loss of a leg in battle, or simple drunkenness.

Illuminated manuscript from the ‘Life of Edmund’, unknown artist, c1130, depicting AD 865 when Ivarr Ragnarsson (nicknamed ‘the Boneless’) with his brothers invaded Northumbria. (Photo Researchers/Alamy Stock Photo)

Aud the Deep-mindedAud the Deep-Minded (alternatively known as the Deep-Wealthy) was the daughter of Ketil Flatnose, a Norwegian chieftain. For much of her life Aud is best known in the traditional female roles of wife and mother. She married Olaf the White, king of Dublin in the mid-ninth century, and following his death moved to Scotland with her son, Thorstein the Red. Thorstein became a great warrior and established himself as king of a large part of northern and western Scotland, before being killed in battle.

It was at this point, late in life, that Aud decided to uproot herself and make a new life in Iceland, taking her grandchildren with her. She saw little chance of maintaining or recovering her importance in Scotland, but the settlement of Iceland in the 870s offered new opportunities. Aud had a ship built and sailed first to Orkney, where she married off one of her granddaughters, and then on to Iceland, where she laid claim to a large area in the west. Aud was accompanied by friends and family, as well as Scottish and Irish slaves. She gave this last group their freedom, granting each man a small piece of land within her larger claim, thereby encouraging loyalty from their descendants to hers.

Aud was remembered as one of the great founding settlers of Iceland. Her large number of grandchildren meant that many of the greatest families in medieval Iceland looked back to her as an ancestor. Although her wealth may partly have been acquired through her father, husband and son, Aud’s success in Iceland is a reminder of how powerful a strong woman could be in Viking society.

Eirik BloodaxeEirik Bloodaxe has an archetypal Viking nickname and was renowned as a fierce warrior. From his early teens onwards he was involved in raiding around the British Isles and in the Baltic, and at different points in his career he was king in both western Norway and in Northumbria, where he still has a legacy in York’s Viking-based tourist industry.

Despite all this, Eirik is a less impressive figure than first appearances suggest. Despite his success in battle, his nickname came from his involvement in the killing of several of his brothers. Eirik and his wife, Gunnhild (according to different accounts either a Danish princess or a witch from northern Norway), were between them responsible for the deaths of five brothers. Their growing unpopularity in Norway meant that when another brother, Håkon the Good, challenged Eirik for the kingship of Norway he was unable to muster support and fled without a fight.

Although Eirik was strong and brave and willing to give even his enemies a fair hearing if left to his own devices, he was said to have been completely under the thumb of his dominating wife and “too easily persuaded”. He comes across more like the cartoon character Hagar the Horrible than as a real Viking hero.

Image of Eirik Bloodaxe (aka Eric Bloodaxe) projected on to Clifford’s Tower at the Jorvik Viking Festival York 2006. In front of the tower stands a group Viking re-enactors. (Tony Wright/earthscapes/Alamy Stock Photo)

Einar Buttered-BreadEinar Buttered-Bread was the grandson of Thorfinn Skullsplitter, the earl of Orkney, and Groa, a granddaughter of Aud the Deep-Minded. According to the Orkneyinga saga, Einar became caught up in a web of treachery and rivalry over the Orkney earldom, in which Ragnhild, daughter of Eirik Bloodaxe, played a central part.

Ragnhild was married first to Thorfinn’s son and heir Arnfinn but had him killed at Murkle in Caithness and married his brother Havard Harvest-Happy, who became earl in his place. Ragnhild then conspired with Einar Buttered-Bread – he was to kill his uncle Havard, her husband, and replace him. Einar Buttered-Bread killed Havard in a battle near Stenness on mainland Orkney.

But that was not the end of the story. Einar Buttered-Bread was then killed by another cousin, Einar Hard-mouth, apparently also at Ragnhild’s instigation. Einar Hard-mouth was then killed by Ljot (another brother of Arnfinn and Havard), who then married Ragnhild and became earl.

Nothing more is known of Einar Buttered-Bread and he earns his place on this list primarily for his intriguing nickname. Whereas it is easy to imagine how his grandfather Thorfinn Skullsplitter gained his name, we don’t know why Einar was called Buttered-Bread, and we probably never will.

Ragnvald of EdRagnvald is known only from a rune-stone that he commissioned in memory of his mother at Ed near Stockholm, probably in the early 11th century. The runic inscription reads simply “Ragnvald had the runes cut in memory of Fastvi, his mother, Onäm’s daughter. She died in Ed. God help her soul. Ragnvald let the runes be cut, who was in Greek-land, and leader of the host”.

Despite being such a short inscription, this provides a variety of information about Ragnvald. Despite being a successful warrior he was a respectful son who went to the trouble of having a stone carved in memory of his mother. Like many Vikings in the 11th century, the invocation to God suggests that Ragnvald (if not necessarily his mother) was Christian.

Ragnvald may have become Christian as a result of his experiences in ‘Greek-land’. This refers not just to Greece but to the whole of the Byzantine Empire, which had its capital at modern Istanbul, known to the Vikings as Miklagard (‘the great city’). Ragnvald travelled all the way to Turkey, a reminder that the Vikings travelled east as well as west, and from his description probably served as an officer in the Varangian Guard. This was a unit in the Byzantine army, often used as the palace guard, and composed primarily of Viking warriors. The existence of such a unit shows the reputation of Viking warriors as far away as the eastern Mediterranean.

Bjarni HerjolfssonBjarni Herjolfsson was the captain of the first ship of Europeans known to have discovered North America. Credit is more often given – especially in America – to Leif Eiriksson, known as Leif the Lucky. Leif was the son of Eirik the Red, who led the settlement of Greenland and himself led an attempt in around AD 1000 to settle in ‘Vinland’, somewhere on the east coast of Canada. However, according to the Saga of the Greenlanders Eirik travelled in the ship formerly owned by Bjarni, and made use of Bjarni’s description of the lands that he had already seen.

Bjarni had discovered America by mistake in 986. An Icelandic trader, he had been in Norway when his father decided to join Eirik the Red’s settlement of Greenland. Attempting to join his father he was blown off course in a storm and passed Greenland to the south, discovering Vinland (vine land), Markland (forest land) and Helluland (a land of flat stones). These are normally identified as Newfoundland, Labrador and Baffin Island. Some scholars prefer to place Vinland further south and west, although a Viking settlement was discovered on the northern tip of Newfoundland.

Bjarni had only come to America in error and, realising his mistake, we are told that he decided not to land, but instead navigated his way up the coast and back to Greenland – a much greater achievement than his accidental discovery, especially since he hadn’t been there before. However inadvertent his discovery was, such achievements deserve better recognition.

The beginning of ‘The Saga of the Greenlanders’, from 'Flateyjarbok' ('The Book of Flatey’). Icelandic School, (14th century). (Arni Magnusson Institute, Reykjavik, Iceland/Bridgeman Images)

Freydis EiriksdottirFreydis was the sister of Leif Eiriksson and daughter of Eirik the Red, the first settler of Greenland. Her brother Leif attempted the first-known European settlement in North America, and a settlement of Viking-type longhouses at l’Anse aux Meadows at the northern tip of Newfoundland may well be the houses that Leif built. Leif himself chose not to stay in ‘Vinland’, but offered the use of his houses to various members of his extended family, although he insisted that the houses remained his property.

Freydis was involved in two attempts to settle Vinland, and in the process proved herself as tough and ruthless as any Viking warrior. On one trip her party established contact with the native people and initially traded peacefully. However, when the party was subsequently attacked by some of the natives, the men were inclined to flee. Freydis, however, although heavily pregnant, picked up a sword and beat it against her bare breast, as the result of which the attackers fled in fright.

On the other expedition Freydis travelled in partnership with a group led by two Icelandic brothers, Helgi and Finnbogi. Having first smuggled a larger number of men on board her ship than agreed, she incited her husband to kill Helgi and Finnbogi and all their men. When they refused to kill the women Freydis did it herself, forbidding on pain of death everyone in her group to reveal this on their return to Greenland.

Cnut the GreatCnut is the ultimate Viking success story. He was the younger son of Svein Forkbeard, king of the Danes, who conquered England in 1013 but died almost immediately. Cnut’s brother Harald inherited the Danish kingdom, so Cnut was left, probably still in his teens, to try to restore his father’s authority in England, which had reverted to the Anglo-Saxon king Ethelred II. By 1016 Cnut had conquered England in his own right, cementing his position by marriage to Ethelred’s widow. Cnut’s success in England came through victory in battle, but within a couple of years he had also become king of Denmark, apparently peacefully.

For the first time, the whole of Denmark and England were under the rule of one king, and in 1028 Cnut also conquered Norway, establishing the largest North Sea empire seen before or since, although it fragmented again following his death in 1035. Cnut also took the opportunity to borrow ideas from his English kingdom to apply in Denmark. While Cnut took – and held – England through good old-fashioned Viking warfare, Denmark now benefited from regular trade and from an influx of ideas as well as material wealth.

Under Cnut towns became more important both as economic and administrative centres, coinage was developed on a large scale, and the influence of the Christian Church became firmly established. Cnut even went on a peaceful pilgrimage to Rome to meet the Pope.

In some ways Cnut can be better understood as an Anglo-Saxon king than a Viking. However, his great success illustrates one of the strengths of the Vikings generally, which was their ability to adapt to a variety of cultures and circumstances across the Viking world. So, the very fact that many of Cnut’s achievements seem rather un-Viking makes him in some ways the quintessential Viking.

Gareth Williams is a historian specialising in the Anglo-Saxon and Viking period and a curator at the British Museum, a role he has held since 1996, with responsibility for British and European coinage.

Silver penny of Cnut, who Gareth Williams describes as "the ultimate Viking success story". (Photo by CM Dixon/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Ivarr the BonelessIvarr spans the gap between history and legend. He was a famous warrior and one of the leaders of the ‘Great Heathen Army’ that landed in East Anglia in 865, and that went on to conquer the kingdoms of Northumbria and East Anglia. Ivarr also went on to lead a raid on Dumbarton on the Clyde, and in Ireland.

Later saga tradition makes Ivarr one of the sons of Ragnar Hairy-breeches. According to this account, Ivarr and his brothers invaded Northumbria to take a bloody revenge on its king, Ælle, for the killing of their father.

Although the Great Army continued to campaign in England, Ivarr is not mentioned in English sources after 870 and probably spent the remainder of his career around the Irish Sea. His death is recorded in Irish annals in 873. He was remembered as the founding father of the royal dynasty of the Viking kingdom of Dublin, and his descendants at various points also ruled in other parts of Ireland, Northumbria and the Isle of Man.

The reason for Ivarr’s curious nickname is unknown. One suggestion is simply that he was particularly flexible, giving the illusion of bonelessness, while others have preferred to see it as a metaphor for impotence. Another interpretation is that Ivarr suffered from ‘brittle bone disease’, which seems less plausible given his reputation as a warrior. However, the nickname beinlausi could also be translated as ‘legless’, which might indicate lameness, the loss of a leg in battle, or simple drunkenness.

Illuminated manuscript from the ‘Life of Edmund’, unknown artist, c1130, depicting AD 865 when Ivarr Ragnarsson (nicknamed ‘the Boneless’) with his brothers invaded Northumbria. (Photo Researchers/Alamy Stock Photo)

Aud the Deep-mindedAud the Deep-Minded (alternatively known as the Deep-Wealthy) was the daughter of Ketil Flatnose, a Norwegian chieftain. For much of her life Aud is best known in the traditional female roles of wife and mother. She married Olaf the White, king of Dublin in the mid-ninth century, and following his death moved to Scotland with her son, Thorstein the Red. Thorstein became a great warrior and established himself as king of a large part of northern and western Scotland, before being killed in battle.

It was at this point, late in life, that Aud decided to uproot herself and make a new life in Iceland, taking her grandchildren with her. She saw little chance of maintaining or recovering her importance in Scotland, but the settlement of Iceland in the 870s offered new opportunities. Aud had a ship built and sailed first to Orkney, where she married off one of her granddaughters, and then on to Iceland, where she laid claim to a large area in the west. Aud was accompanied by friends and family, as well as Scottish and Irish slaves. She gave this last group their freedom, granting each man a small piece of land within her larger claim, thereby encouraging loyalty from their descendants to hers.

Aud was remembered as one of the great founding settlers of Iceland. Her large number of grandchildren meant that many of the greatest families in medieval Iceland looked back to her as an ancestor. Although her wealth may partly have been acquired through her father, husband and son, Aud’s success in Iceland is a reminder of how powerful a strong woman could be in Viking society.

Eirik BloodaxeEirik Bloodaxe has an archetypal Viking nickname and was renowned as a fierce warrior. From his early teens onwards he was involved in raiding around the British Isles and in the Baltic, and at different points in his career he was king in both western Norway and in Northumbria, where he still has a legacy in York’s Viking-based tourist industry.

Despite all this, Eirik is a less impressive figure than first appearances suggest. Despite his success in battle, his nickname came from his involvement in the killing of several of his brothers. Eirik and his wife, Gunnhild (according to different accounts either a Danish princess or a witch from northern Norway), were between them responsible for the deaths of five brothers. Their growing unpopularity in Norway meant that when another brother, Håkon the Good, challenged Eirik for the kingship of Norway he was unable to muster support and fled without a fight.

Although Eirik was strong and brave and willing to give even his enemies a fair hearing if left to his own devices, he was said to have been completely under the thumb of his dominating wife and “too easily persuaded”. He comes across more like the cartoon character Hagar the Horrible than as a real Viking hero.

Image of Eirik Bloodaxe (aka Eric Bloodaxe) projected on to Clifford’s Tower at the Jorvik Viking Festival York 2006. In front of the tower stands a group Viking re-enactors. (Tony Wright/earthscapes/Alamy Stock Photo)

Einar Buttered-BreadEinar Buttered-Bread was the grandson of Thorfinn Skullsplitter, the earl of Orkney, and Groa, a granddaughter of Aud the Deep-Minded. According to the Orkneyinga saga, Einar became caught up in a web of treachery and rivalry over the Orkney earldom, in which Ragnhild, daughter of Eirik Bloodaxe, played a central part.

Ragnhild was married first to Thorfinn’s son and heir Arnfinn but had him killed at Murkle in Caithness and married his brother Havard Harvest-Happy, who became earl in his place. Ragnhild then conspired with Einar Buttered-Bread – he was to kill his uncle Havard, her husband, and replace him. Einar Buttered-Bread killed Havard in a battle near Stenness on mainland Orkney.

But that was not the end of the story. Einar Buttered-Bread was then killed by another cousin, Einar Hard-mouth, apparently also at Ragnhild’s instigation. Einar Hard-mouth was then killed by Ljot (another brother of Arnfinn and Havard), who then married Ragnhild and became earl.

Nothing more is known of Einar Buttered-Bread and he earns his place on this list primarily for his intriguing nickname. Whereas it is easy to imagine how his grandfather Thorfinn Skullsplitter gained his name, we don’t know why Einar was called Buttered-Bread, and we probably never will.

Ragnvald of EdRagnvald is known only from a rune-stone that he commissioned in memory of his mother at Ed near Stockholm, probably in the early 11th century. The runic inscription reads simply “Ragnvald had the runes cut in memory of Fastvi, his mother, Onäm’s daughter. She died in Ed. God help her soul. Ragnvald let the runes be cut, who was in Greek-land, and leader of the host”.

Despite being such a short inscription, this provides a variety of information about Ragnvald. Despite being a successful warrior he was a respectful son who went to the trouble of having a stone carved in memory of his mother. Like many Vikings in the 11th century, the invocation to God suggests that Ragnvald (if not necessarily his mother) was Christian.

Ragnvald may have become Christian as a result of his experiences in ‘Greek-land’. This refers not just to Greece but to the whole of the Byzantine Empire, which had its capital at modern Istanbul, known to the Vikings as Miklagard (‘the great city’). Ragnvald travelled all the way to Turkey, a reminder that the Vikings travelled east as well as west, and from his description probably served as an officer in the Varangian Guard. This was a unit in the Byzantine army, often used as the palace guard, and composed primarily of Viking warriors. The existence of such a unit shows the reputation of Viking warriors as far away as the eastern Mediterranean.

Bjarni HerjolfssonBjarni Herjolfsson was the captain of the first ship of Europeans known to have discovered North America. Credit is more often given – especially in America – to Leif Eiriksson, known as Leif the Lucky. Leif was the son of Eirik the Red, who led the settlement of Greenland and himself led an attempt in around AD 1000 to settle in ‘Vinland’, somewhere on the east coast of Canada. However, according to the Saga of the Greenlanders Eirik travelled in the ship formerly owned by Bjarni, and made use of Bjarni’s description of the lands that he had already seen.

Bjarni had discovered America by mistake in 986. An Icelandic trader, he had been in Norway when his father decided to join Eirik the Red’s settlement of Greenland. Attempting to join his father he was blown off course in a storm and passed Greenland to the south, discovering Vinland (vine land), Markland (forest land) and Helluland (a land of flat stones). These are normally identified as Newfoundland, Labrador and Baffin Island. Some scholars prefer to place Vinland further south and west, although a Viking settlement was discovered on the northern tip of Newfoundland.

Bjarni had only come to America in error and, realising his mistake, we are told that he decided not to land, but instead navigated his way up the coast and back to Greenland – a much greater achievement than his accidental discovery, especially since he hadn’t been there before. However inadvertent his discovery was, such achievements deserve better recognition.

The beginning of ‘The Saga of the Greenlanders’, from 'Flateyjarbok' ('The Book of Flatey’). Icelandic School, (14th century). (Arni Magnusson Institute, Reykjavik, Iceland/Bridgeman Images)

Freydis EiriksdottirFreydis was the sister of Leif Eiriksson and daughter of Eirik the Red, the first settler of Greenland. Her brother Leif attempted the first-known European settlement in North America, and a settlement of Viking-type longhouses at l’Anse aux Meadows at the northern tip of Newfoundland may well be the houses that Leif built. Leif himself chose not to stay in ‘Vinland’, but offered the use of his houses to various members of his extended family, although he insisted that the houses remained his property.

Freydis was involved in two attempts to settle Vinland, and in the process proved herself as tough and ruthless as any Viking warrior. On one trip her party established contact with the native people and initially traded peacefully. However, when the party was subsequently attacked by some of the natives, the men were inclined to flee. Freydis, however, although heavily pregnant, picked up a sword and beat it against her bare breast, as the result of which the attackers fled in fright.

On the other expedition Freydis travelled in partnership with a group led by two Icelandic brothers, Helgi and Finnbogi. Having first smuggled a larger number of men on board her ship than agreed, she incited her husband to kill Helgi and Finnbogi and all their men. When they refused to kill the women Freydis did it herself, forbidding on pain of death everyone in her group to reveal this on their return to Greenland.

Cnut the GreatCnut is the ultimate Viking success story. He was the younger son of Svein Forkbeard, king of the Danes, who conquered England in 1013 but died almost immediately. Cnut’s brother Harald inherited the Danish kingdom, so Cnut was left, probably still in his teens, to try to restore his father’s authority in England, which had reverted to the Anglo-Saxon king Ethelred II. By 1016 Cnut had conquered England in his own right, cementing his position by marriage to Ethelred’s widow. Cnut’s success in England came through victory in battle, but within a couple of years he had also become king of Denmark, apparently peacefully.

For the first time, the whole of Denmark and England were under the rule of one king, and in 1028 Cnut also conquered Norway, establishing the largest North Sea empire seen before or since, although it fragmented again following his death in 1035. Cnut also took the opportunity to borrow ideas from his English kingdom to apply in Denmark. While Cnut took – and held – England through good old-fashioned Viking warfare, Denmark now benefited from regular trade and from an influx of ideas as well as material wealth.

Under Cnut towns became more important both as economic and administrative centres, coinage was developed on a large scale, and the influence of the Christian Church became firmly established. Cnut even went on a peaceful pilgrimage to Rome to meet the Pope.

In some ways Cnut can be better understood as an Anglo-Saxon king than a Viking. However, his great success illustrates one of the strengths of the Vikings generally, which was their ability to adapt to a variety of cultures and circumstances across the Viking world. So, the very fact that many of Cnut’s achievements seem rather un-Viking makes him in some ways the quintessential Viking.

Gareth Williams is a historian specialising in the Anglo-Saxon and Viking period and a curator at the British Museum, a role he has held since 1996, with responsibility for British and European coinage.

Published on June 03, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Nepotianus enters Rome

June 3 350

Roman usurper Nepotianus, of the Constantinian dynasty, proclaimed himself Roman Emperor, entering Rome at the head of a group of gladiators.

Roman usurper Nepotianus, of the Constantinian dynasty, proclaimed himself Roman Emperor, entering Rome at the head of a group of gladiators.

Published on June 03, 2016 02:00

June 2, 2016

Alfred the Great: do we overplay his 'greatness'?

History Extra

For Anglo-Saxon England, AD 878 marked the nadir of the Viking wars. Had events played out only slightly differently the whole history of England might have been fundamentally altered. In that year the great Viking army that had been plundering and conquering Anglo-Saxon kingdoms since 865 marched on King Alfred’s Wessex.

For Anglo-Saxon England, AD 878 marked the nadir of the Viking wars. Had events played out only slightly differently the whole history of England might have been fundamentally altered. In that year the great Viking army that had been plundering and conquering Anglo-Saxon kingdoms since 865 marched on King Alfred’s Wessex.

During the previous 12 years almost all the great kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England had fallen to the Danish Vikings. In 866 they stormed York and killed the two kings of Northumbria. In 869 they martyred King Edmund of East Anglia by tying him to a tree and filling him full of arrows. And then, in 877, they divided the ancient kingdom of Mercia in two.

By 878, very roughly, England north of the A5 (or Watling Street as the Anglo-Saxons called it) lay in Danish hands. Alfred’s Wessex effectively stood alone. Now the Viking army fell upon Wessex with a vengeance. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle would remember that: “In this year [878] in midwinter after 12th night the enemy army came stealthily to Chippenham, and occupied the land of the West Saxons and settled there, and drove a great part of the people across the sea, and conquered most of the others; and the people submitted to them, except King Alfred. He journeyed in difficulties through the woods and fen-fastnesses with a small force.”

This ambush – a lightening strike launched from Gloucester (a mere 30 miles away) – was designed to capture the king while he was celebrating Christmas at the royal manor of Chippenham. Confronted with such a swift, targeted invasion, Alfred was lucky to escape. He did so with the support of a small band of men, fleeing to the seclusion of the nearby Somerset marshes.

Having regrouped, Alfred managed covertly to muster forces across the kingdom and, within the year, defeated the Viking army at Edington in Wiltshire, converted the Danish king, Guthrum, to Christianity and had him leave Wessex. Without this reversal, there would probably have been no England and no English language. Alfred would have been a mere footnote in the history of ‘Daneland’ – which would have been written in Anglo-Danish.

This was not the only time in Alfred’s life that luck played a critical role – something that’s not always been borne out by histories of the king. Although it was only in the 16th century that writers tagged him with his ‘Great’ epithet, Alfred swiftly came to be treated as the saviour – and even father – of England (even though England was not unified until the reign of his grandson, Æthelstan).

At times the reviews have been a touch too rave. The eminently bearded Victorian historian, Edward Augustus Freeman, called Alfred “the most perfect character in history”. Indeed, his reputation as a ‘great’ king has often obscured those moments in his reign where chance played more of a part than wisdom. On a number of occasions, his fate – and that of the kingdom – hung by a fortuitous thread.

A famous victoryAlfred may have succeeded in pushing the Vikings out of Wessex in 878, but the army that he faced was actually only one part of a much larger Danish force. This was not the first time this had happened. His first run-in with the Danes took place in 871 while his brother, Æthelred I, was still on the throne.

In that year he fought nine battles against the Danes and had a famous victory at Ashdown. Yet this was only half the army that had invaded Britain in 865. In 869, two years before the battle of Ashdown, the Danish host had divided into two after it had conquered the kingdoms of Northumbria and East Anglia, sending one group north and the other south. Alfred only had to fight one division of the great army that had conquered two of his neighbours – and his victory was, by all accounts, extremely close.

Similarly, in 878, when Alfred managed to overcome the Danes after they had captured Chippenham, he only had to fight one part of the full Danish force.

Although a new war band led by Guthrum joined the southern army after the battle of Ashdown in 871, causing Alfred to “make peace” (for which read ‘pay off’), it too was to split. Leaving Wessex following the clash at Ashdown, it went to London and then to Northumbria and Lincolnshire before conquering Mercia in 874.

Having driven the Mercian king Burgred into exile, it divided and sent one contingent to Northumbria while the other went to Cambridge, from where it would attack Wessex (in 876) – marching first to Wareham, then to Exeter and finally to Chippenham via Gloucester. As was to be the case in 878, Alfred found himself fighting a smaller army than that which had vanquished his neighbours – and even then, he was nearly defeated.

Had the full Danish army marched directly on Wessex in 866, or had they not divided in 874, it’s likely that – for all the tales of Alfred’s military prowess – his kingdom would have been conquered.

Welsh attacksIf anything symbolises the turnaround in Alfred’s fortunes, it’s the decision of Æthelred, the ruler of western Mercia – the part that the Danes had not conquered – to subject himself to the Wessex king’s lordship in 879.

For centuries the kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex had been arch-enemies, waging wars against each other and, on more than one occasion, nearly wiping each other out.

The union of the two kingdoms was a remarkable moment, one that would seem to underscore the dynamism of Alfred’s rule. Yet closer inspection of the sources shows that the Mercian ruler’s decision to submit to Alfred had more to do with developments on the Welsh border. The Mercians and the Welsh kingdoms had long been at odds. A few years before, the Mercians had defeated and killed the great Rhodri Mawr of Gwynedd. But then, around 879/880, Rhodri’s sons are said to have avenged their father by exacting a heavy defeat upon Æthelred of Mercia.

Æthelred was now in an extremely vulnerable position. Not only were there two deadly Danish armies marauding through the land, but he was also at risk of being overrun by a resurgent kingdom of Gwynedd on his western borders. He needed friends and he needed them quickly – Alfred, who had just secured peace with one Danish army and who was a powerful influence in Welsh politics, was simply the best port in a storm. Through no direct intervention of his own, the union with Mercia fell into Alfred’s lap.

Perhaps the greatest stroke of luck that Alfred enjoyed was becoming king at all. At the time of his birth, it must have been considered unbelievably unlikely that he would ever wear the crown. As the youngest of King Æthelwulf of Wessex’s (died 858) five sons, the odds were heavily stacked against him.

As it was, fate intervened. Alfred’s eldest brother, Æthelstan, predeceased their father. His next brother, Æthelbald, died in 860, followed by the third, Æthelberht, in 865, and, finally, the fourth, Æthelred in 871. Within 20 years, Wessex had lost four king’s sons from the same generation.

This loss was Alfred’s gain. But the profusion of royal sons – almost unparalleled in Anglo-Saxon history – was also an enormous stroke of luck for the kingdom. Had Wessex had fewer kingly scions there would undoubtedly have been a succession crisis once the last had gone the way of earthly flesh. This is something that the Vikings would have been keen to exploit – their attack on Northumbria in 866 appears to have been timed to coincide with a civil war between two claimants for the throne.

Yet, perversely, being the fifth-born, runt of the litter may also have brought with it advantages. As the last in line, it is possible that Alfred was being groomed for a career in the church. Alfred’s much celebrated love of learning and bookishness may have stemmed from an education that was priming him for a more academic career.

Alfred is the only ruler before Henry VIII whose philosophical writings survive. His translations of Pope Gregory the Great’s Pastoral Care, Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, and St Augustine’s Soliloquies into Old English are subtly infused with his personal views of kingship. These were underscored by his law code, which attached great emphasis on loyalty to the king – likening the relationship between subject and ruler to that between disciple and Christ, and declaring that no mercy could be offered for treachery: “…since Almighty God adjudged none for those who despised Him, nor did Christ, the Son of God, adjudge any for the one who betrayed Him to death; and He commanded everyone to love his lord as Himself.”

Such scholarship was typical of Alfred’s rule. He understood the power of the written word and obliged all of his nobles’ sons to learn to read. He also seems to have commissioned both the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle – which charts the West Saxons’ rise to fame – and his own biography, Bishop Asser’s Life of King Alfred which, while no hagiography, gives an extremely favourable view of the king’s career. If the picture that historians draw of Alfred is sometimes too rosy, it is because the king himself was clever enough to supply a lot of our source material.

This resourcefulness is found in spades following the Viking attack on Chippenham in 878. Such a resurgence can only have been predicated on the loyalty of countrymen, without which he could have raised no army and won no victory. His decision to convert Guthrum to Christianity bound the Viking king to him and neutralised a threat – never again would Guthrum attack Wessex.

Although a decade of fragile peace followed, Alfred did not stand idly by, and instead organised a flurry of fortification. Towns or forts – known as burhs – had their defences strengthened or established for the first time, and precise arrangements were made for their garrisoning: local landowners were obliged to provide four men to defend each ‘pole’ of wall (ie a length of 5½ yards).

So, when Danish armies again turned their attention to Wessex in the early 890s, the kingdom was ready. This defensive network and military reorganisation – partially based on earlier Anglo-Saxon systems, partially on those of Alfred’s stepmother’s father, the French king Charles the Bald (d877) – meant that his son Edward and grandson Æthelstan could conquer the Danelaw, and so establish the kingdom of England.

This is heady stuff, so it is perhaps unsurprising that historians have sometimes gotten carried away. But in their excitement, they’ve often overlooked a number of factors – not least, how much of Alfred’s success was built on luck. Recognising the role of chance in this feted reign helps bring a touch of realism to the Alfredian tale and, rather than detracting from his greatness, helps show it as it really was. Doing this is important, because it reveals just how fragile the conditions were that surrounded the birth of England – a slip-up here, a Viking raid there, a premature death or an infertile marriage and everything might very easily have been extraordinarily different.

This is not to say that Alfred was not great – by any standards his was a remarkable reign – but it is to acknowledge that his success did not derive from talent alone and that the creation of the English kingdom was anything but inevitable.

For Anglo-Saxon England, AD 878 marked the nadir of the Viking wars. Had events played out only slightly differently the whole history of England might have been fundamentally altered. In that year the great Viking army that had been plundering and conquering Anglo-Saxon kingdoms since 865 marched on King Alfred’s Wessex.