MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 100

May 18, 2016

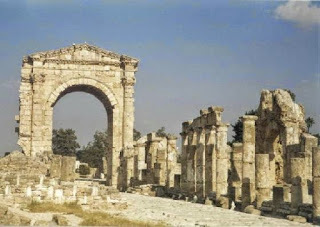

History Trivia - Crusaders abandon Tyre

May 18

1291 the Crusaders abandoned Tyre to the Moslems, the prelude to the end of the final Crusade.

1291 the Crusaders abandoned Tyre to the Moslems, the prelude to the end of the final Crusade.

Published on May 18, 2016 02:00

May 17, 2016

Romans, quaking in their Sandals After an Attack by Boudica, built a Massive Fort to Defend London

Ancient Origins

Around 60 AD Queen Boudica of the Iceni (a Celtic clan) attacked and razed London, a Roman city of ancient Britain. Now, researchers have just announced that in response to Boudica and her warriors’ wild revolution, the terrified and shamed Romans built a fort with ditches 10 feet (3.05 meters) deep, walls 10 feet high, palisades, and a platform from which to repel attacks.

Boudica (also spelt Boudicca and Boadicea) was an imposing, even terrifying sight, according to the Roman historian Cassius Dio, who described her and the destruction her forces wrought:

The Snettisham Torc (a golden necklace) like one Boudica might have worn. (

U. of Chicago

)No wonder the terrified Romans built such a massive fort.

The Snettisham Torc (a golden necklace) like one Boudica might have worn. (

U. of Chicago

)No wonder the terrified Romans built such a massive fort.

“Positioned over the main road into London, commanding the route into the town from London Bridge and overlooking the river, the fort would have dominated the town at this time, perhaps reflecting the absence of civilian life and the utter destruction wrought by the native Britons on Roman London,” says the Museum of London Archaeology in a short article.

Boudicca, the Celtic Queen that unleashed fury on the RomansIs Celtic Birdlip Grave the Final Resting Place of Queen Boudicca?The British government, in excavations at Plantation Palace on Fenchurch Street, uncovered the wooden and earthwork fort, which covered 3.7 acres. It measured 3 meters (9.84 ft.) high and was reinforced with growing turf and interlacing timbers. There was a fighting platform with palisade and towers at the gateway on the top of the bank.

For extra protection, the fort was enclosed by double ditches, 1.9 (6.2 feet) meters wide and 3 meters (9.84 ft.) deep. A press release from the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) called the ditches “an impressive obstacle for would be attackers.”

Reconstruction of a Roman defensive position. (

MOLA

)Apparently, the fort was a temporary, emergency structure that was not meant to be occupied long-term and was used to re-establish and reconstruct the important trading post. MOLA says researchers found evidence of tent use in the fort as opposed to permanent barracks. It was in use for only 10 years.

Reconstruction of a Roman defensive position. (

MOLA

)Apparently, the fort was a temporary, emergency structure that was not meant to be occupied long-term and was used to re-establish and reconstruct the important trading post. MOLA says researchers found evidence of tent use in the fort as opposed to permanent barracks. It was in use for only 10 years.

Julian Hill, Roman London Expert at MOLA, said in a press release: “The discovery of this early Roman fort provides precious new information about how the Romans re-established control of Britain following Boudica’s damaging blow. It also demonstrates the strategic importance of London at this time.”

‘Boadicea Haranguing the Britons’ by John Opie. (

Public Domain

)The museum’s website about the find states:

‘Boadicea Haranguing the Britons’ by John Opie. (

Public Domain

)The museum’s website about the find states:

Militaria from Plantation Place Roman fort. (

MOLA

)“A number of major infrastructure projects contemporary with the fort point to the army playing a crucial role in this rebuilding, providing labour and engineering expertise for roads, a new quay and a water lifting machine, all vital for trading and civilian life to thrive once again,” the article states.

Militaria from Plantation Place Roman fort. (

MOLA

)“A number of major infrastructure projects contemporary with the fort point to the army playing a crucial role in this rebuilding, providing labour and engineering expertise for roads, a new quay and a water lifting machine, all vital for trading and civilian life to thrive once again,” the article states.

About 60 years after Boudica’s attack, the Romans built Cripplegate fort, then in the 3rd century a big wall was built around London. Archaeologists are searching for forts or other defensive structures from the intervening periods.

Timber lacework from vallum of the fort. (

MOLA

)Featured Image: Reconstruction of Plantation Place Fort. Source:

MOLA

Timber lacework from vallum of the fort. (

MOLA

)Featured Image: Reconstruction of Plantation Place Fort. Source:

MOLA

By Mark Miller

Around 60 AD Queen Boudica of the Iceni (a Celtic clan) attacked and razed London, a Roman city of ancient Britain. Now, researchers have just announced that in response to Boudica and her warriors’ wild revolution, the terrified and shamed Romans built a fort with ditches 10 feet (3.05 meters) deep, walls 10 feet high, palisades, and a platform from which to repel attacks.

Boudica (also spelt Boudicca and Boadicea) was an imposing, even terrifying sight, according to the Roman historian Cassius Dio, who described her and the destruction her forces wrought:

“...a terrible disaster occurred in Britain. Two cities were sacked, eighty thousand of the Romans and of their allies perished, and the island was lost to Rome. Moreover, all this ruin was brought upon the Romans by a woman, a fact which in itself caused them the greatest shame....But the person who was chiefly instrumental in rousing the natives and persuading them to fight the Romans, the person who was thought worthy to be their leader and who directed the conduct of the entire war, was Buduica, a Briton woman of the royal family and possessed of greater intelligence than often belongs to women....In stature she was very tall, in appearance most terrifying, in the glance of her eye most fierce, and her voice was harsh; a great mass of the tawniest hair fell to her hips; around her neck was a large golden necklace ; and she wore a tunic of diverse colours over which a thick mantle was fastened with a brooch. This was her invariable attire.”

The Snettisham Torc (a golden necklace) like one Boudica might have worn. (

U. of Chicago

)No wonder the terrified Romans built such a massive fort.

The Snettisham Torc (a golden necklace) like one Boudica might have worn. (

U. of Chicago

)No wonder the terrified Romans built such a massive fort.“Positioned over the main road into London, commanding the route into the town from London Bridge and overlooking the river, the fort would have dominated the town at this time, perhaps reflecting the absence of civilian life and the utter destruction wrought by the native Britons on Roman London,” says the Museum of London Archaeology in a short article.

Boudicca, the Celtic Queen that unleashed fury on the RomansIs Celtic Birdlip Grave the Final Resting Place of Queen Boudicca?The British government, in excavations at Plantation Palace on Fenchurch Street, uncovered the wooden and earthwork fort, which covered 3.7 acres. It measured 3 meters (9.84 ft.) high and was reinforced with growing turf and interlacing timbers. There was a fighting platform with palisade and towers at the gateway on the top of the bank.

For extra protection, the fort was enclosed by double ditches, 1.9 (6.2 feet) meters wide and 3 meters (9.84 ft.) deep. A press release from the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) called the ditches “an impressive obstacle for would be attackers.”

Reconstruction of a Roman defensive position. (

MOLA

)Apparently, the fort was a temporary, emergency structure that was not meant to be occupied long-term and was used to re-establish and reconstruct the important trading post. MOLA says researchers found evidence of tent use in the fort as opposed to permanent barracks. It was in use for only 10 years.

Reconstruction of a Roman defensive position. (

MOLA

)Apparently, the fort was a temporary, emergency structure that was not meant to be occupied long-term and was used to re-establish and reconstruct the important trading post. MOLA says researchers found evidence of tent use in the fort as opposed to permanent barracks. It was in use for only 10 years.Julian Hill, Roman London Expert at MOLA, said in a press release: “The discovery of this early Roman fort provides precious new information about how the Romans re-established control of Britain following Boudica’s damaging blow. It also demonstrates the strategic importance of London at this time.”

‘Boadicea Haranguing the Britons’ by John Opie. (

Public Domain

)The museum’s website about the find states:

‘Boadicea Haranguing the Britons’ by John Opie. (

Public Domain

)The museum’s website about the find states:“The Roman army were experts in construction; proficiently sourcing local materials from nearby woods and even using debris from buildings burnt in the revolt. It is estimated that a fort of this size would have housed a cohort of approximately 500 men but could have been built by hand in a matter of weeks, perhaps with the help of captive Britons. Archaeologists uncovered a pick axe and a hammer, tools that would have been available to the army for building projects.”Tomoe Gozen - A fearsome Japanese Female Warrior of the 12th CenturyMetal detectorist uncovers Roman treasure hoard in EnglandThe fort had roads, storage and administrative facilities, a cookhouse, a granary, and a latrine. Very few artifacts were found, though archaeologists did turn up part of a helmet and some mounts from horse harnesses.

Militaria from Plantation Place Roman fort. (

MOLA

)“A number of major infrastructure projects contemporary with the fort point to the army playing a crucial role in this rebuilding, providing labour and engineering expertise for roads, a new quay and a water lifting machine, all vital for trading and civilian life to thrive once again,” the article states.

Militaria from Plantation Place Roman fort. (

MOLA

)“A number of major infrastructure projects contemporary with the fort point to the army playing a crucial role in this rebuilding, providing labour and engineering expertise for roads, a new quay and a water lifting machine, all vital for trading and civilian life to thrive once again,” the article states.About 60 years after Boudica’s attack, the Romans built Cripplegate fort, then in the 3rd century a big wall was built around London. Archaeologists are searching for forts or other defensive structures from the intervening periods.

Timber lacework from vallum of the fort. (

MOLA

)Featured Image: Reconstruction of Plantation Place Fort. Source:

MOLA

Timber lacework from vallum of the fort. (

MOLA

)Featured Image: Reconstruction of Plantation Place Fort. Source:

MOLA

By Mark Miller

Published on May 17, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - King Henry III of England second coronation

May 17

1220 King Henry III of England Crowned for a second time. Henry, who had been crowned at age nine four years earlier, underwent a second coronation at Westminster.

1220 King Henry III of England Crowned for a second time. Henry, who had been crowned at age nine four years earlier, underwent a second coronation at Westminster.

Published on May 17, 2016 02:00

May 16, 2016

The princes in the Tower: why was their fate never explained?

History Extra

Paul Delaroche's 19th-century painting of the princes in the Tower. (Bridgeman Art Library)

Paul Delaroche's 19th-century painting of the princes in the Tower. (Bridgeman Art Library)

Locked in the Tower in June 1483 with his younger brother, the 12-year-old Edward V was certain “that death was facing him”. Two overthrown kings had died in suspicious circumstances already that century. Yet it was still possible their uncle, Richard III, would spare them. The princes were so very young, and if it were accepted that they were bastards, as their uncle claimed, they would pose little threat. The innocent Richard, Duke of York, only nine years old, remained “joyous” and full of “frolics”, even as the last of their servants were dismissed. But the boys were spotted behind the Tower windows less and less often, and by the summer’s end they had vanished. It is the fact of their disappearance that lies at the heart of the many conspiracy theories over what happened to the princes. Murder was suspected, but without bodies no one could be certain even that they were dead. Many different scenarios have been put forward in the years since. In the nearest surviving contemporary accounts, Richard is accused of ordering their deaths, with the boys either suffocated with their bedding, or drowned, or killed by having their arteries cut. There were also theories that one or both of the princes escaped. In more modern times, some have come to believe that Richard III was innocent of ordering the children’s deaths and instead spirited his nephews abroad or to a safe place nearer home, only for them to be killed later by Henry VII who feared the boys’ rival claims to the throne. None of these theories, however, has provided a satisfactory answer to the riddle at the heart of this mystery: the fact the boys simply vanished. If the princes were alive, why did Richard not say so in October 1483, when the rumours he had ordered them killed were fuelling a rebellion? If they were dead, why had he not followed earlier examples of royal killings? The bodies of deposed kings were displayed and claims made that they had died of natural causes, so that loyalties could be transferred to the new king. That the answer to these questions lies in the 15th century seems obvious, but it can be hard to stop thinking like 21st-century detectives and start thinking like contemporaries. To the modern mind, if Richard III was a religious man and a good king, as many believe he was, then he could not have ordered the deaths of two children. But even good people do bad things if they’re given the right motivation. In the 15th century it was a primary duty of good kingship to ensure peace and national harmony. After his coronation, Richard III continued to employ many of his brother Edward IV’s former servants, but by the end of July 1483 it was already clear that some did not accept that Edward IV’s sons were illegitimate and judged Richard to be a usurper. The fact the princes remained a focus of opposition gave Richard a strong motive for having them killed – just as his brother had killed the king he deposed. The childlike, helpless, Lancastrian Henry VI was found dead in the Tower in 1471, after more than a decade of conflict between the rival royal Houses of Lancaster and York. It was said he was killed by grief and rage over the death in battle of his son, but few can have doubted that Edward IV ordered Henry’s murder. Henry VI’s death extirpated the House of Lancaster. Only Henry VI’s half nephew, Henry Tudor, a descendent of John of Gaunt, founder of the Lancastrian House, through his mother’s illegitimate Beaufort line, was left to represent their cause. Trapped in European exile, Henry Tudor posed a negligible threat to Edward IV. However, Richard was acutely aware of an unexpected sequel to Henry VI’s death. The murdered king was acclaimed as a saint, with rich and poor alike venerating him as an innocent whose troubled life gave him some insight into their own difficulties. Miracles were reported at the site of his modest grave in Chertsey Abbey, Surrey. One man claimed that the dead king had even deigned to help him when he had a bean trapped in his ear, with said bean popping out after he prayed to the deposed king. Edward IV failed to put a halt to the popular cult and Richard III shared his late brother’s anxieties about its ever-growing power. It had a strong following in his home city of York, where a statue of ‘Henry the saint’ was built on the choir screen at York Minster. In 1484 Richard attempted to take control of the cult with an act of reconciliation, moving Henry VI’s body to St George’s Chapel, Windsor. In the meantime, there was a high risk the dead princes too would attract a cult, for in them the religious qualities attached to royalty were combined with the purity of childhood.

Richard III. (National Portrait Gallery) An insecure kingIn England we have no equivalent today to the shrine at Lourdes in France, visited by thousands of pilgrims every year looking for healing or spiritual renewal. But we can recall the vast crowds outside Buckingham Palace after the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. Imagine that feeling and enthusiasm in pilgrims visiting the tombs of two young princes and greatly magnified by the closeness people then felt with the dead. It would have been highly dangerous to the king who had taken their throne. The vanishing of the princes was for Richard a case of least said, soonest mended, for without a grave for them, there could be no focus for a cult. Without a body or items belonging to the dead placed on display, there would be no relics either. Nevertheless, Richard needed the princes’ mother, Elizabeth Woodville, and others who might follow Edward V, to know the boys were dead, in order to forestall plots raised in their name. According to the Tudor historian Polydore Vergil, Elizabeth Woodville fainted when she was told her sons had been killed. As she came round, “She wept, she cryed out loud, and with lamentable shrieks made all the house ring, she struck her breast, tore and cut her hair.” She also called for vengeance. Elizabeth Woodville made an agreement with Henry Tudor’s mother, Margaret Beaufort, that Henry should marry her daughter, Elizabeth of York, and called on Edwardian loyalists to back their cause. The rebellion that followed in October 1483 proved Richard had failed to restore peace. While he defeated these risings, less than two years later at the battle of Bosworth, in August 1485, he was betrayed by part of his own army and was killed, sword in hand. The princes were revenged, but it soon became evident that Henry VII was in no hurry to investigate their fate. It is possible that the new monarch feared such an investigation would draw attention to a role in their fate played by someone close to his cause – most likely Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham. The duke, who came from a Lancastrian family, was a close ally of Richard in the overthrow of Edward V, but later turned against the king. Known as a “sore and hard dealing man”, it is possible he encouraged Richard to have the princes murdered, planning then to see Richard killed and the House of York overthrown. Richard executed Buckingham for treason in November 1483, but Buckingham’s name remained associated at home and abroad with the princes’ disappearance. What is certain, however, is that Henry, like Richard, had good reasons for wishing to forestall a cult of the princes. Henry’s blood claim to the throne was extremely weak and he was fearful of being seen as a mere king consort to Elizabeth of York. To counter this, Henry claimed the throne in his own right, citing divine providence – God’s intervention on earth – as evidence that he was a true king (for only God made kings). A key piece of vidence used in support of this idea was a story that, a few months before his murder, ‘the saint’ Henry VI had prophesised Henry Tudor’s reign.

The monument to Henry VII and Elizabeth of York at Westminster Abbey. (Alamy) It would not have been wise to allow Yorkist royal saints to compete with the memory of Henry VI, whose cult Henry VII now wished to encourage. In 1485, therefore, nothing was said of the princes’ disappearance, beyond a vague accusation in parliament during the autumn that Richard III was guilty of “treasons, homicides and murders in shedding of infants’ blood”. No search was made for the boys’ bodies and they were given no rite of burial. Indeed even the fate of their souls was, seemingly, abandoned. I have not found any evidence of endowments set up to pay for prayers for the princes that century. Henry may well have feared the churches where these so-called ‘chantries’ might be established would become centres for the kind of cult he wanted to avoid. But their absence would have struck people as very strange. Praying for the dead was a crucial part of medieval religion. In December 1485 when Henry issued a special charter refounding his favourite religious order, the Observant Friars, at Greenwich, he noted that offering masses for the dead was, “the greatest work of piety and mercy, for through it souls would be purged”. It was unthinkable not to help the souls of your loved ones pass from purgatory to heaven with prayers and masses. On the other hand, it was akin to a curse to say a requiem for a living person – you were effectively praying for their death. A surviving prince?The obvious question posed by the lack of public prayers for the princes was, were they still alive? And, as Vergil recalled, in 1491 there appeared in Ireland, as if “raised from the dead one of the sons of King Edward… a youth by the name of Richard”. Henry VII said the man claiming to be the younger of the princes was, in fact, a Dutchman called Perkin Warbeck – but who could be sure? Henry was more anxious than ever that the princes be forgotten and when their mother, Elizabeth Woodville, died in June 1492, she was buried “privily… without any solemn dirge done for her obit”. It has been suggested this may have reflected her dying wishes to be buried “without pomp”. But Henry VII also asked to be buried without pomp. He still expected, and got, one of the most stately funerals of the Middle Ages. Elizabeth Woodville emphatically did not receive the same treatment. Much has been made of this in conspiracy theories concerning the princes (especially on the question of whether she believed them to be alive) but Henry’s motives become clear when recalled in the context of the period. This was an era of visual symbols and display: kings projected their power and significance in palaces decorated with their badges, in rich clothes and elaborate ceremonies. Elizabeth Woodville, like her sons, was being denied the images of a great funeral with its effigies, banners and grand ceremonial. This caused negative comment at the time. But with Warbeck’s appearance, Henry wanted to avoid any nostalgia for the past glories of the House of York. It was 1497 before Perkin Warbeck was captured. Henry then kept him alive because he wanted Warbeck publicly and repeatedly to confess his modest birth. Warbeck was eventually executed in 1499. Yet even then Henry continued to fear the power of the vanished princes. Three years later, it was given out that condemned traitor Sir James Tyrell had, before his execution, confessed to arranging their murder on Richard’s orders. Henry VIII’s chancellor, Thomas More, claimed he was told the murdered boys had been buried at the foot of some stairs in the Tower, but that Richard had asked for their bodies to be reburied with dignity and that those involved had subsequently died so the boys’ final resting place was unknown – a most convenient outcome for Henry. While the princes’ graves remained unmarked, the tomb of Henry VI came to rival the internationally famous tomb of Thomas Becket at Canterbury as a site of mass pilgrimage. Henry ran a campaign to have his half-uncle beatified by the pope, which continued even after Henry’s death, ending only with Henry VIII’s break with Rome. The Reformation then brought to a close the cult of saints in England. Our cultural memories of their power faded away, which explains why we overlook the significance of the cult of Henry VI in the fate of the princes. In 1674, long after the passing of the Tudors, two skeletons were recovered in the Tower, in a place that resembled More’s description of the princes’ first burial place. They were interred at Westminster Abbey, not far from where Henry VII lies. In 1933, they were removed and examined by two doctors. Broken and incomplete, the skeletons were judged to be two children, one aged between seven and 11 and the other between 11 and 13. The little bones were returned to the abbey, and whoever they were, remain a testament to the failure of Richard and Henry to bury the princes in eternal obscurity. The players in the princes’ downfallHenry VI (1421–71) Succeeding his father, Henry V, who died when he was a few months old, Henry VI’s reign was challenged by political and economic crises. It was interrupted by his mental and physical breakdown in 1453 during which time Richard, 3rd Duke of York, was appointed protector of the realm. Both men were direct descendants of Edward III and in 1455 Richard’s own claim to the throne resulted in the first clashes of the Wars of the Roses – fought between supporters of the dynastic houses of Lancaster and York over the succession. Richard died at the battle of Wakefield in 1460 but his family claim to the throne survived him and his eldest son became king the following year – as Edward IV. Richard’s younger son would also be king, as Richard III. Henry VI was briefly restored to the throne in 1470 but the Lancastrians were finally defeated at Tewkesbury in 1471 and Henry was probably put to death in the Tower of London a few days later. Edward IV (1442–83) Edward succeeded where his father Richard, the third Duke of York failed – in overthrowing Henry VI during the Wars of the Roses. He was declared king in March 1461, securing his throne with a victory at the battle of Towton. Edward’s younger brother Richard became Duke of Gloucester. Later, in Edward’s second reign, Richard played an important role in government. Edward married Elizabeth Woodville in 1463 and they had 10 children: seven daughters and three sons. The eldest, Elizabeth, was born in 1466. Two of the three sons were alive at the time of Edward’s death – Edward, born in 1470, and Richard, born 1473. Edward is credited with being financially astute and restoring law and order. He died unexpectedly of natural causes on 9 April 1483. Elizabeth, Queen Consort (c1437–92) Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, a widow with children, took place in secret in 1464 and met with political disapproval. The king’s brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, was among those allegedly hostile to it. The preference the Woodville family received caused resentment at court, and there was friction between Elizabeth’s family and the king’s powerful advisor, Hastings. On Edward IV’s death in 1483, Gloucester’s distrust of the Woodvilles was apparently a factor in his decision to seize control of the heir, his nephew. Elizabeth sought sanctuary in Westminster, from where her younger son, Richard, Duke of York, was later removed. The legitimacy of her marriage and her children was one of Gloucester’s justifications for usurping the throne on 26 June. Once parliament confirmed his title as Richard III, Elizabeth submitted in exchange for protection for herself and her daughters – an arrangement he honoured. After Richard III’s death at the battle of Bosworth, her children were declared legitimate. Her eldest, Elizabeth of York, was married to Henry VII, strengthening his claim to the throne. Edward V (1470–83) & Richard, Duke of York (1473–83) Edward IV’s heir was his eldest son, also named Edward. When the king died unexpectedly, his will, which has not survived, reportedly named his previously loyal brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, as lord protector. On hearing of his father’s death, the young Edward and his entourage began a journey from Ludlow to the capital. Gloucester intercepted the party in Buckinghamshire. Gloucester, who claimed the Woodvilles were planning to take power by force, seized the prince. On 4 May 1983, Edward entered London in the charge of Gloucester. Edward’s coronation was scheduled for 22 June. On 16 June, Elizabeth was persuaded to surrender Edward’s younger brother, Richard, apparently to attend the ceremony. With both princes in his hands, Gloucester publicised his claim to the throne. He was crowned as Richard III on 6 July and a conspiracy to rescue the princes failed that month. By September, rebels were seeing Henry Tudor as a candidate for the throne, suggesting the princes were already believed to be dead. Richard III (1452–85) Richard was the youngest surviving son of Richard, 3rd Duke of York, and was still a child when his 18-year-old brother became Edward IV after Yorkist victories. Unlike his brother George (executed for treason in the Tower in 1478 – allegedly drowned in a butt of malmsey wine), Richard was loyal to Edward during his lifetime. On his brother’s death, he moved swiftly to wrest control of his nephew Edward from the boy’s maternal family, the Woodvilles. At some point in June 1483 his role moved from that of protector to usurper. He arrested several of the previous king’s loyal advisors, postponed the coronation and claimed Edward IV’s children were illegitimate because their father had been pre-contracted to marry another woman at the time of his secret marriage to Elizabeth. Richard was crowned, but he faced rebellion that year and further unrest the next. Support for the king decreased as it grew for Henry Tudor, the rival claimant who returned from exile and triumphed at the battle of Bosworth in 1485. Henry VII (1457–1509) Henry Tudor was the son of Margaret Beaufort (great-great-granddaughter of Edward III) and Edmund Tudor, half-brother of Henry VI. In 1471, after Edward IV regained the throne, Henry fled to Brittany, where he avoided the king’s attempts to have him returned. As a potential candidate for the throne through his mother’s side, Henry became the focus for opposition to Richard III. After the failed 1483 rebellion against the king, rebels, including relatives of the Woodvilles and loyal former members of Edward IV’s household, joined him in Brittany. In 1485 Henry Tudor invaded, landing first in Wales, and triumphed over Richard III at Bosworth on 22 August. Henry was crowned on the battlefield with Richard’s crown. The following year he further legitimised his right to rule by marrying Elizabeth of York. When the king died in 1509, his and Elizabeth’s son came to the throne as Henry VIII. Leanda de Lisle is a historian and writer. She is the author of Tudor: The Family Story (1437–1603) (Chatto and Windus, 2013).

Paul Delaroche's 19th-century painting of the princes in the Tower. (Bridgeman Art Library)

Paul Delaroche's 19th-century painting of the princes in the Tower. (Bridgeman Art Library) Locked in the Tower in June 1483 with his younger brother, the 12-year-old Edward V was certain “that death was facing him”. Two overthrown kings had died in suspicious circumstances already that century. Yet it was still possible their uncle, Richard III, would spare them. The princes were so very young, and if it were accepted that they were bastards, as their uncle claimed, they would pose little threat. The innocent Richard, Duke of York, only nine years old, remained “joyous” and full of “frolics”, even as the last of their servants were dismissed. But the boys were spotted behind the Tower windows less and less often, and by the summer’s end they had vanished. It is the fact of their disappearance that lies at the heart of the many conspiracy theories over what happened to the princes. Murder was suspected, but without bodies no one could be certain even that they were dead. Many different scenarios have been put forward in the years since. In the nearest surviving contemporary accounts, Richard is accused of ordering their deaths, with the boys either suffocated with their bedding, or drowned, or killed by having their arteries cut. There were also theories that one or both of the princes escaped. In more modern times, some have come to believe that Richard III was innocent of ordering the children’s deaths and instead spirited his nephews abroad or to a safe place nearer home, only for them to be killed later by Henry VII who feared the boys’ rival claims to the throne. None of these theories, however, has provided a satisfactory answer to the riddle at the heart of this mystery: the fact the boys simply vanished. If the princes were alive, why did Richard not say so in October 1483, when the rumours he had ordered them killed were fuelling a rebellion? If they were dead, why had he not followed earlier examples of royal killings? The bodies of deposed kings were displayed and claims made that they had died of natural causes, so that loyalties could be transferred to the new king. That the answer to these questions lies in the 15th century seems obvious, but it can be hard to stop thinking like 21st-century detectives and start thinking like contemporaries. To the modern mind, if Richard III was a religious man and a good king, as many believe he was, then he could not have ordered the deaths of two children. But even good people do bad things if they’re given the right motivation. In the 15th century it was a primary duty of good kingship to ensure peace and national harmony. After his coronation, Richard III continued to employ many of his brother Edward IV’s former servants, but by the end of July 1483 it was already clear that some did not accept that Edward IV’s sons were illegitimate and judged Richard to be a usurper. The fact the princes remained a focus of opposition gave Richard a strong motive for having them killed – just as his brother had killed the king he deposed. The childlike, helpless, Lancastrian Henry VI was found dead in the Tower in 1471, after more than a decade of conflict between the rival royal Houses of Lancaster and York. It was said he was killed by grief and rage over the death in battle of his son, but few can have doubted that Edward IV ordered Henry’s murder. Henry VI’s death extirpated the House of Lancaster. Only Henry VI’s half nephew, Henry Tudor, a descendent of John of Gaunt, founder of the Lancastrian House, through his mother’s illegitimate Beaufort line, was left to represent their cause. Trapped in European exile, Henry Tudor posed a negligible threat to Edward IV. However, Richard was acutely aware of an unexpected sequel to Henry VI’s death. The murdered king was acclaimed as a saint, with rich and poor alike venerating him as an innocent whose troubled life gave him some insight into their own difficulties. Miracles were reported at the site of his modest grave in Chertsey Abbey, Surrey. One man claimed that the dead king had even deigned to help him when he had a bean trapped in his ear, with said bean popping out after he prayed to the deposed king. Edward IV failed to put a halt to the popular cult and Richard III shared his late brother’s anxieties about its ever-growing power. It had a strong following in his home city of York, where a statue of ‘Henry the saint’ was built on the choir screen at York Minster. In 1484 Richard attempted to take control of the cult with an act of reconciliation, moving Henry VI’s body to St George’s Chapel, Windsor. In the meantime, there was a high risk the dead princes too would attract a cult, for in them the religious qualities attached to royalty were combined with the purity of childhood.

Richard III. (National Portrait Gallery) An insecure kingIn England we have no equivalent today to the shrine at Lourdes in France, visited by thousands of pilgrims every year looking for healing or spiritual renewal. But we can recall the vast crowds outside Buckingham Palace after the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. Imagine that feeling and enthusiasm in pilgrims visiting the tombs of two young princes and greatly magnified by the closeness people then felt with the dead. It would have been highly dangerous to the king who had taken their throne. The vanishing of the princes was for Richard a case of least said, soonest mended, for without a grave for them, there could be no focus for a cult. Without a body or items belonging to the dead placed on display, there would be no relics either. Nevertheless, Richard needed the princes’ mother, Elizabeth Woodville, and others who might follow Edward V, to know the boys were dead, in order to forestall plots raised in their name. According to the Tudor historian Polydore Vergil, Elizabeth Woodville fainted when she was told her sons had been killed. As she came round, “She wept, she cryed out loud, and with lamentable shrieks made all the house ring, she struck her breast, tore and cut her hair.” She also called for vengeance. Elizabeth Woodville made an agreement with Henry Tudor’s mother, Margaret Beaufort, that Henry should marry her daughter, Elizabeth of York, and called on Edwardian loyalists to back their cause. The rebellion that followed in October 1483 proved Richard had failed to restore peace. While he defeated these risings, less than two years later at the battle of Bosworth, in August 1485, he was betrayed by part of his own army and was killed, sword in hand. The princes were revenged, but it soon became evident that Henry VII was in no hurry to investigate their fate. It is possible that the new monarch feared such an investigation would draw attention to a role in their fate played by someone close to his cause – most likely Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham. The duke, who came from a Lancastrian family, was a close ally of Richard in the overthrow of Edward V, but later turned against the king. Known as a “sore and hard dealing man”, it is possible he encouraged Richard to have the princes murdered, planning then to see Richard killed and the House of York overthrown. Richard executed Buckingham for treason in November 1483, but Buckingham’s name remained associated at home and abroad with the princes’ disappearance. What is certain, however, is that Henry, like Richard, had good reasons for wishing to forestall a cult of the princes. Henry’s blood claim to the throne was extremely weak and he was fearful of being seen as a mere king consort to Elizabeth of York. To counter this, Henry claimed the throne in his own right, citing divine providence – God’s intervention on earth – as evidence that he was a true king (for only God made kings). A key piece of vidence used in support of this idea was a story that, a few months before his murder, ‘the saint’ Henry VI had prophesised Henry Tudor’s reign.

The monument to Henry VII and Elizabeth of York at Westminster Abbey. (Alamy) It would not have been wise to allow Yorkist royal saints to compete with the memory of Henry VI, whose cult Henry VII now wished to encourage. In 1485, therefore, nothing was said of the princes’ disappearance, beyond a vague accusation in parliament during the autumn that Richard III was guilty of “treasons, homicides and murders in shedding of infants’ blood”. No search was made for the boys’ bodies and they were given no rite of burial. Indeed even the fate of their souls was, seemingly, abandoned. I have not found any evidence of endowments set up to pay for prayers for the princes that century. Henry may well have feared the churches where these so-called ‘chantries’ might be established would become centres for the kind of cult he wanted to avoid. But their absence would have struck people as very strange. Praying for the dead was a crucial part of medieval religion. In December 1485 when Henry issued a special charter refounding his favourite religious order, the Observant Friars, at Greenwich, he noted that offering masses for the dead was, “the greatest work of piety and mercy, for through it souls would be purged”. It was unthinkable not to help the souls of your loved ones pass from purgatory to heaven with prayers and masses. On the other hand, it was akin to a curse to say a requiem for a living person – you were effectively praying for their death. A surviving prince?The obvious question posed by the lack of public prayers for the princes was, were they still alive? And, as Vergil recalled, in 1491 there appeared in Ireland, as if “raised from the dead one of the sons of King Edward… a youth by the name of Richard”. Henry VII said the man claiming to be the younger of the princes was, in fact, a Dutchman called Perkin Warbeck – but who could be sure? Henry was more anxious than ever that the princes be forgotten and when their mother, Elizabeth Woodville, died in June 1492, she was buried “privily… without any solemn dirge done for her obit”. It has been suggested this may have reflected her dying wishes to be buried “without pomp”. But Henry VII also asked to be buried without pomp. He still expected, and got, one of the most stately funerals of the Middle Ages. Elizabeth Woodville emphatically did not receive the same treatment. Much has been made of this in conspiracy theories concerning the princes (especially on the question of whether she believed them to be alive) but Henry’s motives become clear when recalled in the context of the period. This was an era of visual symbols and display: kings projected their power and significance in palaces decorated with their badges, in rich clothes and elaborate ceremonies. Elizabeth Woodville, like her sons, was being denied the images of a great funeral with its effigies, banners and grand ceremonial. This caused negative comment at the time. But with Warbeck’s appearance, Henry wanted to avoid any nostalgia for the past glories of the House of York. It was 1497 before Perkin Warbeck was captured. Henry then kept him alive because he wanted Warbeck publicly and repeatedly to confess his modest birth. Warbeck was eventually executed in 1499. Yet even then Henry continued to fear the power of the vanished princes. Three years later, it was given out that condemned traitor Sir James Tyrell had, before his execution, confessed to arranging their murder on Richard’s orders. Henry VIII’s chancellor, Thomas More, claimed he was told the murdered boys had been buried at the foot of some stairs in the Tower, but that Richard had asked for their bodies to be reburied with dignity and that those involved had subsequently died so the boys’ final resting place was unknown – a most convenient outcome for Henry. While the princes’ graves remained unmarked, the tomb of Henry VI came to rival the internationally famous tomb of Thomas Becket at Canterbury as a site of mass pilgrimage. Henry ran a campaign to have his half-uncle beatified by the pope, which continued even after Henry’s death, ending only with Henry VIII’s break with Rome. The Reformation then brought to a close the cult of saints in England. Our cultural memories of their power faded away, which explains why we overlook the significance of the cult of Henry VI in the fate of the princes. In 1674, long after the passing of the Tudors, two skeletons were recovered in the Tower, in a place that resembled More’s description of the princes’ first burial place. They were interred at Westminster Abbey, not far from where Henry VII lies. In 1933, they were removed and examined by two doctors. Broken and incomplete, the skeletons were judged to be two children, one aged between seven and 11 and the other between 11 and 13. The little bones were returned to the abbey, and whoever they were, remain a testament to the failure of Richard and Henry to bury the princes in eternal obscurity. The players in the princes’ downfallHenry VI (1421–71) Succeeding his father, Henry V, who died when he was a few months old, Henry VI’s reign was challenged by political and economic crises. It was interrupted by his mental and physical breakdown in 1453 during which time Richard, 3rd Duke of York, was appointed protector of the realm. Both men were direct descendants of Edward III and in 1455 Richard’s own claim to the throne resulted in the first clashes of the Wars of the Roses – fought between supporters of the dynastic houses of Lancaster and York over the succession. Richard died at the battle of Wakefield in 1460 but his family claim to the throne survived him and his eldest son became king the following year – as Edward IV. Richard’s younger son would also be king, as Richard III. Henry VI was briefly restored to the throne in 1470 but the Lancastrians were finally defeated at Tewkesbury in 1471 and Henry was probably put to death in the Tower of London a few days later. Edward IV (1442–83) Edward succeeded where his father Richard, the third Duke of York failed – in overthrowing Henry VI during the Wars of the Roses. He was declared king in March 1461, securing his throne with a victory at the battle of Towton. Edward’s younger brother Richard became Duke of Gloucester. Later, in Edward’s second reign, Richard played an important role in government. Edward married Elizabeth Woodville in 1463 and they had 10 children: seven daughters and three sons. The eldest, Elizabeth, was born in 1466. Two of the three sons were alive at the time of Edward’s death – Edward, born in 1470, and Richard, born 1473. Edward is credited with being financially astute and restoring law and order. He died unexpectedly of natural causes on 9 April 1483. Elizabeth, Queen Consort (c1437–92) Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, a widow with children, took place in secret in 1464 and met with political disapproval. The king’s brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, was among those allegedly hostile to it. The preference the Woodville family received caused resentment at court, and there was friction between Elizabeth’s family and the king’s powerful advisor, Hastings. On Edward IV’s death in 1483, Gloucester’s distrust of the Woodvilles was apparently a factor in his decision to seize control of the heir, his nephew. Elizabeth sought sanctuary in Westminster, from where her younger son, Richard, Duke of York, was later removed. The legitimacy of her marriage and her children was one of Gloucester’s justifications for usurping the throne on 26 June. Once parliament confirmed his title as Richard III, Elizabeth submitted in exchange for protection for herself and her daughters – an arrangement he honoured. After Richard III’s death at the battle of Bosworth, her children were declared legitimate. Her eldest, Elizabeth of York, was married to Henry VII, strengthening his claim to the throne. Edward V (1470–83) & Richard, Duke of York (1473–83) Edward IV’s heir was his eldest son, also named Edward. When the king died unexpectedly, his will, which has not survived, reportedly named his previously loyal brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, as lord protector. On hearing of his father’s death, the young Edward and his entourage began a journey from Ludlow to the capital. Gloucester intercepted the party in Buckinghamshire. Gloucester, who claimed the Woodvilles were planning to take power by force, seized the prince. On 4 May 1983, Edward entered London in the charge of Gloucester. Edward’s coronation was scheduled for 22 June. On 16 June, Elizabeth was persuaded to surrender Edward’s younger brother, Richard, apparently to attend the ceremony. With both princes in his hands, Gloucester publicised his claim to the throne. He was crowned as Richard III on 6 July and a conspiracy to rescue the princes failed that month. By September, rebels were seeing Henry Tudor as a candidate for the throne, suggesting the princes were already believed to be dead. Richard III (1452–85) Richard was the youngest surviving son of Richard, 3rd Duke of York, and was still a child when his 18-year-old brother became Edward IV after Yorkist victories. Unlike his brother George (executed for treason in the Tower in 1478 – allegedly drowned in a butt of malmsey wine), Richard was loyal to Edward during his lifetime. On his brother’s death, he moved swiftly to wrest control of his nephew Edward from the boy’s maternal family, the Woodvilles. At some point in June 1483 his role moved from that of protector to usurper. He arrested several of the previous king’s loyal advisors, postponed the coronation and claimed Edward IV’s children were illegitimate because their father had been pre-contracted to marry another woman at the time of his secret marriage to Elizabeth. Richard was crowned, but he faced rebellion that year and further unrest the next. Support for the king decreased as it grew for Henry Tudor, the rival claimant who returned from exile and triumphed at the battle of Bosworth in 1485. Henry VII (1457–1509) Henry Tudor was the son of Margaret Beaufort (great-great-granddaughter of Edward III) and Edmund Tudor, half-brother of Henry VI. In 1471, after Edward IV regained the throne, Henry fled to Brittany, where he avoided the king’s attempts to have him returned. As a potential candidate for the throne through his mother’s side, Henry became the focus for opposition to Richard III. After the failed 1483 rebellion against the king, rebels, including relatives of the Woodvilles and loyal former members of Edward IV’s household, joined him in Brittany. In 1485 Henry Tudor invaded, landing first in Wales, and triumphed over Richard III at Bosworth on 22 August. Henry was crowned on the battlefield with Richard’s crown. The following year he further legitimised his right to rule by marrying Elizabeth of York. When the king died in 1509, his and Elizabeth’s son came to the throne as Henry VIII. Leanda de Lisle is a historian and writer. She is the author of Tudor: The Family Story (1437–1603) (Chatto and Windus, 2013).

Published on May 16, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Eleanor of Aquitaine marries Henry Anjou

Published on May 16, 2016 02:00

May 15, 2016

7 surprising Ancient Rome facts

History Extra

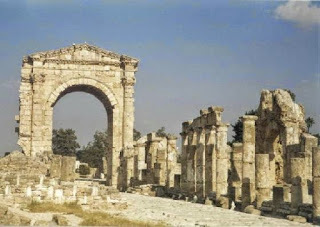

The Intervention of the Sabine Women, painting by the French painter Jacques-Louis David, 1799. Musee Du Louvre, Paris, France. (Photo by Exotica.im/UIG via Getty Images) 1) The Roman’s couldn’t decide on their originsThe legend of Romulus and Remus tells the story of twin brothers raised by wolves who become the founding fathers of Rome.

The Intervention of the Sabine Women, painting by the French painter Jacques-Louis David, 1799. Musee Du Louvre, Paris, France. (Photo by Exotica.im/UIG via Getty Images) 1) The Roman’s couldn’t decide on their originsThe legend of Romulus and Remus tells the story of twin brothers raised by wolves who become the founding fathers of Rome.The boys’ mother, Rhea Silvia, had been forced into becoming a Vestal Virgin (priestesses who attended to the sacred fire of Vesta) by the usurper Amulius. Rhea Silvia then had a miraculous conception, either by the god Mars or by Hercules (there are variations on the myth). When Amulius heard of this, he ordered the infant twins to be taken to the river Tiber where they were left to die.

In the event they were saved and nourished by a she-wolf and later taken in by a shepherd and his family until they grew to manhood, unaware of their origins. Eventually they heard the story of the treachery of Amulius, after which they confronted and killed the tyrant. Then, because Romulus wanted to found their new city on the Palatine Hill and Remus preferred the Aventine Hill, they agreed to see a soothsayer. However, each brother interpreted the results in his own favour. This led to a fight in which Romulus killed Remus, and that founded the new city of Rome in 753 BC.

What’s stranger still is that there was a later ‘founding of Rome’ story. Written around the 8th century BC, Homer’s Iliad recalls the story of the Trojan War but Rome's origins are linked to the second telling of this same story by another giant of ancient writing, Virgil, in his book The Aeneid. As well as enhancing Homer’s earlier story, The Aeneid also postdates the tale of Romulus and Remus. This is important because, according to Virgil, Troy’s population wasn’t completely destroyed. Instead, a prince called Aeneas escaped with a small group of Trojans and sailed the Mediterranean until he found an area he liked the look of. So this ancient and noble civilisation transplanted itself in Italy and founded Rome.

Both tales are revealing. The first shows us that the Romans were explaining where their predatory and argumentative attitudes came from: they are all the children of wolves. The second story was created at the time of emperors, so there is a demand for respectability and heritage. The Trojan War was as famous then as now, so why not connect this new empire to a very old and familiar tale?

A stone plate of Rome's founders, Romulus and Remus, suckled by a female wolf, seen at the National Historical Museum, Sofia, Bulgaria, in April 2011. (Photo by Nikolay Doychinov/AFP/Getty Images)

A stone plate of Rome's founders, Romulus and Remus, suckled by a female wolf, seen at the National Historical Museum, Sofia, Bulgaria, in April 2011. (Photo by Nikolay Doychinov/AFP/Getty Images)2) Rome was a bad neighbourBy the 5th century BC, Rome was one of many tiny states on the Italian peninsula. If you were a gambler in 480 BC you would probably have put your money on an eventual Etruscan empire. The Etruscsns were after all the biggest power on the Italian peninsula at that time. Over the centuries the realm had grown substantially, and while Rome’s central and southern towns had thrown off Etruscan dominance, it was still the largest power in an area populated by numerous other Italic peoples, many of their names barely remembered by history.

It's a forgotten fact that the Romans had to conquer the rest of Italy, and one of the first tribes to fall was the Sabines. According to a famous legend, oft repeated in ancient texts (and a popular subject with Renaissance artists), the Romans abducted the Sabine women for breeding purposes, in order to increase the population of Rome. Whether this was true or not is impossible to say, but the Romans were consistently avid slavers, and what is uncontested is that by the dawn of the 4th century BC the Sabine kingdom had been absorbed into Roman lands.

10 things you didn't know about the Romans Romans and Italians were never the same thing. It’s just that the Roman city state was more aggressive, with a better army, or luckier than the other kingdoms of Italy. It wouldn’t have taken much to snuff out Rome at this time, in which case this article you are reading could have been about the empire of the Frentani, yet another Italic people then located on the east coast of the peninsula.

Although geographically close to each other, these realms were so diverse that they didn’t even speak the same language. Etruscan is still, frustratingly, one of the languages that has yet to be satisfactorily translated. The Sabines, similarly, were not Latin speakers. The Hellenic colonies in the toe of Italy spoke Greek. To these people the Romans were not fellow countrymen carrying out a hostile takeover that was always inevitable and perhaps a tiny bit yearned for. Instead, this was an invasion by a foreign nation of terrifying men who spoke an alien tongue.

3) The first sacking of Rome nearly finished the cityThe traditional date for the first sacking of Rome is 390 BC, but modern historians agree that a date of 387 BC is more likely. When a tribe of Gauls, called the Senones, came over the Alps into Italy in search of lands to settle, the first people they met were the Etruscans. Unsurprisingly, they didn’t want to cede any of their lands to these foreigners, so they asked for military assistance from the rising military power of Rome.

Rome gathered together a large army and sent it north to help its neighbour fight this alien threat. Meanwhile, the diplomacy wasn’t going well. Even in this ancient era there was a general rule that ambassadors and messengers were to be left unharmed, but one of the Roman diplomats killed one of the Gaulish chieftains. The Gauls (not unreasonably) demanded that the perpetrators be brought to justice, and some in Rome agreed. However, the Roman masses did not, and this provocation led to the meeting of both sides at the Allia River, both ready for battle.

The Romans had amassed a mighty army; the Senones had an army of about half the size. However, as battle ensued, the Gauls shattered the two flanks of the Roman army and surrounded the elite central force. Now outmanoeuvred and tired from fighting, this Roman army was completely annihilated. The road to Rome was open to the Gauls, who were led by the terrifying figure of Brennus.

What happened next is described in a series of fables and legends, none of which dispute that the Gauls fell on Rome and destroyed much of it. Indeed, they did such a good job that contemporary histories of Rome prior to and during this period are sketchy because of the scale of destruction.

Why the Gauls didn’t settle in the conquered city is unknown. One Roman source claims they were chased away by another Roman army, but this was most likely an explanation created to give the Romans something of a face-saving ending to an otherwise total defeat. What is more probable is that like many northern armies that had tried to settle around Rome, the Gauls found the climate distinctly unhealthy, and it’s probable that disease spread through Brennus’ men. Either way, the Gauls retreated into the mists of legend and hearsay.

Rome was so completely destroyed that there was serious debate about re-founding the capital in the nearby (and completely forgotten town) of Veii. Instead, the Senate decided to stay and authorised the building of the first major stone walls to defend the city.

Battle between Romans and Gauls. (Photo by Leemage/UIG via Getty Images)

4) The battle of Adrianople was the beginning of the endBy the 4th century AD, Germanic invasions were starting to become a serious problem for the Roman empire. It was during this period that a number of new groups began to appear in the Roman hinterlands. Some of these people were known as the Goths.

Initially the Goths agreed to join the empire, settle as farmers and, in essence, merge with the local population. But the Goths were hardly welcomed with open arms, and heavy-handedness by local Roman governors led to Goth resentments and uprisings. Exactly who was to blame for the resulting conflict is hard to say.

The Gothic War lasted from AD 376 to 382. This new wave of barbarians was running amok, and there were frequent clashes with the forces of the western Roman emperor Gratian. However, it was the eastern Roman emperor Valens who went personally to deal with them.

The two sides met near Adrianople (modern day Edirne in Turkey). The Roman writer Ammianus Marcellinus claims that Valens had around 25,000 men against a horde of 80,000 (as is often the case with ancient texts, these numbers are probably exaggerated).

The Romans had marched for seven or eight hours over rough terrain; they were tired and out of formation when they arrived in front of the Gothic army. The 4thcentury legions were, by now, clad in mail armour and had large round shields, all of which were an added burden under the hot August sun. Some of the Roman army attacked without orders and were easily pushed back. The Roman soldier’s rash actions meant he had no option but to engage in battle.

The Gothic force’s centre was a defensive circle of wagons, which the Romans failed to penetrate. However, while the Romans were busy attacking this defensive position, the Goth cavalry crept in from the sides and outflanked Valens’ forces. The heavily armoured Romans were not as nimble or agile as the Goths, and while they managed to break out from the enveloping moves by the Goth cavalry, they were now fighting in small groups and not as a unified army. In the ensuing chaos most of the Roman troops were slaughtered, including the emperor, Valens.

Valens’ successor, Theodosius, was forced to turn the Goths from enemies into allies, but at the cost of land. This was a turning point from which the Roman empire never recovered.

5) The capital of the late Roman empire wasn’t RomeThe Roman empire got its name from its founding city. Therefore, when Rome finally fell forever from the power of the emperors, the change in circumstances must mark the end of the Roman empire, right?

However, while it is often recognised that in the late Roman era Constantinople was the more important city, what almost nobody realises is that by the early 5th century AD, the western Roman emperors had moved the capital from the ancient and illustrious city of Rome.

By AD 402 the terrible emperor Honorius felt that Rome was no longer defensible and decided to move the capital to Ravenna. This was a large town with a population of around 50,000, and had been part of the empire since the 2nd century BC. Despite receiving regular investment funds (emperor Trajan built a massive aqueduct), it was never one of the most important urban areas of the empire and had been in decline in recent times. However, Ravenna had a large and easily defendable port and became the base for Rome’s naval fleet in the Adriatic Sea. As it was also surrounded by marshland, it was regarded as a place of safety, with guaranteed connections to the stronger eastern empire.

The move to Ravenna was an admission by Honorius that Rome could no longer hold back the barbarian invasions. It remained the capital of the empire until its eventual fall in AD 476. It was recaptured by the eastern Roman empire in AD 584 and was part of those lands until 751.

6) The last western emperor shared a name with the founder of RomeRomulus Augustus, better known as Romulus Augustulus, ‘little Augustus’, was a boy who ‘ruled’ for about 10 months from AD 475–476. He was little more than a figurehead for his father Orestes, a Roman aristocrat (of Germanic ancestry), who had manoeuvred his way into a position of power in the court in Ravenna.

By now the title of western Roman emperor was virtually meaningless. The only remaining areas of the empire were the Italian peninsula, along with some fragmentary lands in Gaul, Spain and Croatia. Barbarian groups had already sacked Rome twice, and any real power was held by these tribes and not by the Roman court in Ravenna.

Little is known about the teenage Romulus Augustulus. Coins were minted with his face, but he led no armies and no monuments were built for him. He was an irrelevance.

The 8 bloodiest Roman emperors The Germanic leader Odoacer knew this and, in AD 476, marched on Ravenna. Odoacer had been leading the foederati, the barbarian contingents that by now made up almost the entire ‘Roman’ army. He had all the real power and he knew it.

On arriving in Ravenna and finding no resistance, Odoacer met face-to-face with the so-called emperor, Romulus Augustus. However, the chronicles then say that Odoacer, “taking pity on his youth”, spared Romulus' life. Odoacer carried out no bloody coup, nor did he take the imperial title, because he knew that it had ceased to have any significance. Instead, he recast himself as the first king of Italy, after which he granted Romulus an annual pension and sent him to live with relatives in southern Italy.

Odoacer then got on with reshaping Italy, not in the mould of the old empire, but in the form of a new kingdom. The transformation was long overdue, and as a result, Odoacer was able to bring more stability to the time of his reign than the previous emperors had managed during the past 80 years.

The last western Roman emperor did not go down in a battle, nor did he commit suicide. He was deposed and sent home like a naughty schoolboy. This was final humiliation for a title that, from Scotland to Iraq, had once put fear in men’s hearts.

c475 AD, last Roman emperor of the west, Romulus Augustulus. (Photo by Spencer Arnold/Getty Images)

7) When the Roman empire ended is up for debateWhat determines the final demise of the empire is notoriously difficult. The easiest date to use is the fall of Rome… but which one? 410 doesn’t mark the end of the list of western Roman emperors, nor does 455. The other problem is that while Rome was the cradle of the empire, by the 5th century it was neither the most important city (Constantinople), nor the capital of the Western Roman Empire (Ravenna).

The second date that could be used is 476, when Romulus Augutulus was deposed. Again, this doesn’t work because the eastern Roman emperor was still the most powerful person in the world (except for the emperor of China). His empire might have become known as the Byzantine empire, and its inhabitants might have begun speaking Greek, but they considered themselves to be as Roman as Julius Caesar – right up until the bitter end – an ending that happened twice.

The Byzantine empire was the victim of the Fourth Crusade and was conquered in 1204. This was the end of the empire then, surely?

However, just a couple of generations later, it threw off its western overlords, and the emperors returned. These were to last until the Ottoman conquest of 1453 (where the last eastern Roman emperor, unlike the last western one, did go down in a blaze of glory on the city’s battlements).

So does 1453 count as the end of the empire? This is an even harder date to use because the 15th-century world was very different to that of the Roman empire at its peak. Worse still, since Charlemagne was crowned emperor of the Romans in 800, there had been a number of Germanic rulers who would, by the Middle Ages, claim to be ‘holy Roman emperors’. They were no such thing, but the title was still in play.

And yet, still later dates could be used: when Constantinople fell to the Ottomans, two very different dynasties took up the title of Roman emperor and Caesar. Firstly the Ottoman sultan took the title because he had just conquered the old eastern capital. Secondly, as Constantinople had been the capital of Orthodox Christianity, the Russian rulers, as defenders of the Orthodox faith, took the title Caesar (‘tsar’ in Russian).

None of these dates are satisfactory, so the last fact is really a question. Which date would you choose?

Jem Duducu is the author of The Romans in 100 Facts (Amberley Publishing, 2015).

Published on May 15, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Stephen Langton named Archbishop of Canterbury

May 15

1213 King John named Stephen Langton Archbishop of Canterbury after submitting to the Pope's authority and offering to make England and Ireland papal fiefs, which resulted in Pope Innocent III lifting the interdict of 1208.

1213 King John named Stephen Langton Archbishop of Canterbury after submitting to the Pope's authority and offering to make England and Ireland papal fiefs, which resulted in Pope Innocent III lifting the interdict of 1208.

Published on May 15, 2016 02:00

May 14, 2016

Archaeologists Discover Remains of Viking Parliament of Medieval Norse King in Scotland

Ancient Origins

A place where Vikings settled disputes, made key political decisions, and decided laws has been unearthed on the Isle of Bute, in Scotland.

The history of the Isle of Bute is connected with the Norse King Ketill Flatnose, whose descendants were the earliest settlers of Iceland. The site which was recently discovered has been identified as the location of a Norse parliament, known as a ''thing''.

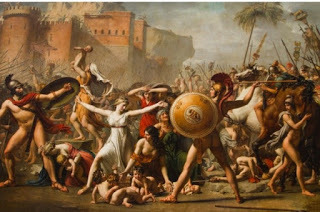

'Althing in Session' (19th century) by W. G. Collingwood. (Public Domain)Although in our times this word is mostly related to unimportant objects, in Viking times this term had a different meaning. According to specialists in old Scandinavian languages, the word ''thing'' came from the old Norse word ''ping'', meaning assembly.

'Althing in Session' (19th century) by W. G. Collingwood. (Public Domain)Although in our times this word is mostly related to unimportant objects, in Viking times this term had a different meaning. According to specialists in old Scandinavian languages, the word ''thing'' came from the old Norse word ''ping'', meaning assembly.

The mound site at Cnoc an Rath has been an interesting archaeological site since the 1950s, but it has never been fully researched. The recent series of excavations was started due to the suggestion that it could have been a farm site dating back to the prehistoric or medieval period.

The Herald reports that archaeologists uncovered samples of a preserved surface during excavations, which was analyzed with the use of radiocarbon dating. The results were clear; the area was an important land for the Vikings during their stay in Scotland.

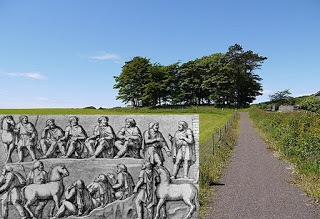

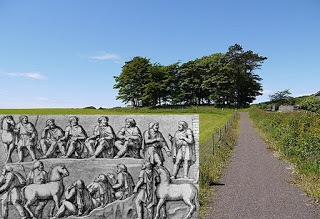

Cnoc an Rath on the Isle of Bute, Scotland. (

Discover Bute, Youtube Screenshot

)The discovery was presented at the beginning of May at the Scottish Place-Name Society Conference, held in Rothesay on the Isle of Bute. According to the researchers, the discovered site contains important evidence of human activity and a possible location for the headquarters of the Gall-Gaidheil, meaning ''Foreign Gaels''.

Cnoc an Rath on the Isle of Bute, Scotland. (

Discover Bute, Youtube Screenshot

)The discovery was presented at the beginning of May at the Scottish Place-Name Society Conference, held in Rothesay on the Isle of Bute. According to the researchers, the discovered site contains important evidence of human activity and a possible location for the headquarters of the Gall-Gaidheil, meaning ''Foreign Gaels''.

Archaeologists Discover 1,000-year-old Viking 'Parliament' in ScotlandThe Ancient Parliamentary Plains of IcelandThe Sagas of the Icelanders shed light on Golden AgeAs archaeologist Paul Duffy, who runs Brandanii Archaeology and Heritage Consultancy, said:

The main evidence which links Bute with old Viking traditions is the Irish religious manuscript Martyrology of Tallaght, which dates to around 900 AD. It refers to the bishop, St. Blane of Kingarth on Bute, who stayed in the territory of the Gall-Gaidheil. The researchers believe that the leader of the Gall-Gaidheil, Ketill Flatnose, was also connected with this place. Apart from this, medieval farms dated back to the 14th century have also been identified at the location.

The path at Cnoc an Rath on the Isle of Bute, Scotland. (Alan Reid/

CC BY SA 2.0

)It is not the first discovery like this in Scotland. On October 27, 2013, Ancient Origins informed that archaeologists discovered an 11th century Viking parliament underneath a parking lot in the town of Dingwall. It was considered as a rare finding because most Viking assemblies took place in open-air fields - so it is quite unusual to find a more permanent building that was used.

The path at Cnoc an Rath on the Isle of Bute, Scotland. (Alan Reid/

CC BY SA 2.0

)It is not the first discovery like this in Scotland. On October 27, 2013, Ancient Origins informed that archaeologists discovered an 11th century Viking parliament underneath a parking lot in the town of Dingwall. It was considered as a rare finding because most Viking assemblies took place in open-air fields - so it is quite unusual to find a more permanent building that was used.

An important parliament site was also discovered in Iceland, at Þingvellir (the ‘assembly fields’ or ‘Parliament Plains’), which is in the southwestern part of the island. Founded in 930 AD, the Althingi was initially used for the general assembly of the Icelandic Commonwealth. The gatherings typically lasted for two weeks in June, which was a period of uninterrupted daylight, and had the mildest weather.

During these meetings, the country’s most powerful leaders would decide on legislation and dispense justice. At the center of the assembly was the Lögberg, or Law Rock. This was a rocky outcrop which the Lawspeaker, the presiding official of the assembly, took his seat. Today, Þingvellir is an Icelandic national park, as well as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Lögberg, or Law Rock, at Þingvellir National Park, Iceland. (

My Iceland

)The domination of the Vikings on the seas and oceans was visible for a few centuries in the Middle Ages. The Norse people left Scandinavia, traveled to Scotland, Ireland, Iceland, Greenland, and finally landed in North America, where they created the first settlements in Canada.

The Lögberg, or Law Rock, at Þingvellir National Park, Iceland. (

My Iceland

)The domination of the Vikings on the seas and oceans was visible for a few centuries in the Middle Ages. The Norse people left Scandinavia, traveled to Scotland, Ireland, Iceland, Greenland, and finally landed in North America, where they created the first settlements in Canada.

The heritage of the people from some of the coldest parts of Europe is related not only with war but also building boats and the colonization of new lands. The Vikings had a well-organized society, which respected law and had a form of structure - which nowadays we often call a parliament.

Þorgnýr the Lawspeaker showing the power of his office to the King of Sweden at Gamla Uppsala, 1018. (Public Domain)Featured Image: The site of Cnoc an Rath on the Isle of Bute, Scotland. (

Paul Duffy

) Germanic thing, drawn after the depiction in a relief of the Column of Marcus Aurelius (AD 193) (Public Domain)

Þorgnýr the Lawspeaker showing the power of his office to the King of Sweden at Gamla Uppsala, 1018. (Public Domain)Featured Image: The site of Cnoc an Rath on the Isle of Bute, Scotland. (

Paul Duffy

) Germanic thing, drawn after the depiction in a relief of the Column of Marcus Aurelius (AD 193) (Public Domain)

By Natalia Klimczak

A place where Vikings settled disputes, made key political decisions, and decided laws has been unearthed on the Isle of Bute, in Scotland.

The history of the Isle of Bute is connected with the Norse King Ketill Flatnose, whose descendants were the earliest settlers of Iceland. The site which was recently discovered has been identified as the location of a Norse parliament, known as a ''thing''.

'Althing in Session' (19th century) by W. G. Collingwood. (Public Domain)Although in our times this word is mostly related to unimportant objects, in Viking times this term had a different meaning. According to specialists in old Scandinavian languages, the word ''thing'' came from the old Norse word ''ping'', meaning assembly.

'Althing in Session' (19th century) by W. G. Collingwood. (Public Domain)Although in our times this word is mostly related to unimportant objects, in Viking times this term had a different meaning. According to specialists in old Scandinavian languages, the word ''thing'' came from the old Norse word ''ping'', meaning assembly.The mound site at Cnoc an Rath has been an interesting archaeological site since the 1950s, but it has never been fully researched. The recent series of excavations was started due to the suggestion that it could have been a farm site dating back to the prehistoric or medieval period.

The Herald reports that archaeologists uncovered samples of a preserved surface during excavations, which was analyzed with the use of radiocarbon dating. The results were clear; the area was an important land for the Vikings during their stay in Scotland.

Cnoc an Rath on the Isle of Bute, Scotland. (

Discover Bute, Youtube Screenshot

)The discovery was presented at the beginning of May at the Scottish Place-Name Society Conference, held in Rothesay on the Isle of Bute. According to the researchers, the discovered site contains important evidence of human activity and a possible location for the headquarters of the Gall-Gaidheil, meaning ''Foreign Gaels''.

Cnoc an Rath on the Isle of Bute, Scotland. (

Discover Bute, Youtube Screenshot

)The discovery was presented at the beginning of May at the Scottish Place-Name Society Conference, held in Rothesay on the Isle of Bute. According to the researchers, the discovered site contains important evidence of human activity and a possible location for the headquarters of the Gall-Gaidheil, meaning ''Foreign Gaels''.Archaeologists Discover 1,000-year-old Viking 'Parliament' in ScotlandThe Ancient Parliamentary Plains of IcelandThe Sagas of the Icelanders shed light on Golden AgeAs archaeologist Paul Duffy, who runs Brandanii Archaeology and Heritage Consultancy, said:

“The first date from the site is between the mid-7th Century and the mid-9th century. That is the end of Dalriada and the time when the Vikings arrive at the end of the 8th Century - so it puts it firmly in the time we were looking at, although maybe a little bit early to be a 'thing' site. The second date we got back - was late 7th Century to late 9th century – which puts it quite firmly in the period when we are fairly sure Vikings are active round about the Argyll coast and Bute.''The Norse-Gael society dominated the region of the Irish Sea for a part of the medieval times. They supported the Kings of Ireland with military forces.

The main evidence which links Bute with old Viking traditions is the Irish religious manuscript Martyrology of Tallaght, which dates to around 900 AD. It refers to the bishop, St. Blane of Kingarth on Bute, who stayed in the territory of the Gall-Gaidheil. The researchers believe that the leader of the Gall-Gaidheil, Ketill Flatnose, was also connected with this place. Apart from this, medieval farms dated back to the 14th century have also been identified at the location.

The path at Cnoc an Rath on the Isle of Bute, Scotland. (Alan Reid/

CC BY SA 2.0

)It is not the first discovery like this in Scotland. On October 27, 2013, Ancient Origins informed that archaeologists discovered an 11th century Viking parliament underneath a parking lot in the town of Dingwall. It was considered as a rare finding because most Viking assemblies took place in open-air fields - so it is quite unusual to find a more permanent building that was used.

The path at Cnoc an Rath on the Isle of Bute, Scotland. (Alan Reid/

CC BY SA 2.0

)It is not the first discovery like this in Scotland. On October 27, 2013, Ancient Origins informed that archaeologists discovered an 11th century Viking parliament underneath a parking lot in the town of Dingwall. It was considered as a rare finding because most Viking assemblies took place in open-air fields - so it is quite unusual to find a more permanent building that was used.An important parliament site was also discovered in Iceland, at Þingvellir (the ‘assembly fields’ or ‘Parliament Plains’), which is in the southwestern part of the island. Founded in 930 AD, the Althingi was initially used for the general assembly of the Icelandic Commonwealth. The gatherings typically lasted for two weeks in June, which was a period of uninterrupted daylight, and had the mildest weather.