MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 98

May 27, 2016

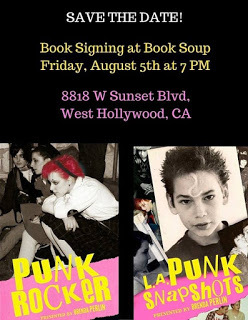

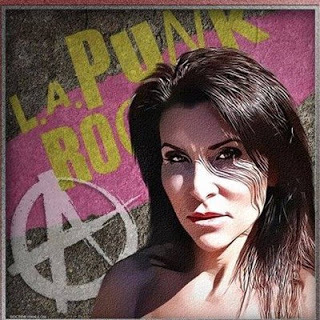

Book signing - meet Author Brenda Perlin at Book Soup on Friday August 5th at 7pm!

SAVE THE DATE!

Book Signing for PUNK ROCKER & unreleased L.A. PUNK SNAPSHOTS at Book Soup Friday August 5th at 7pm!

8818 W Sunset Blvd, West Hollywood, CA · (310) 659-3110

Punk Rocker is the much anticipated sequel to “L.A. Punk Rocker”: top author Brenda Perlin’s best-selling punk anthology. Here you will find a collection of short stories from those who were there in the early days. Hard core musical anarchists who saw it all, heard it all, did it all - and survived to tell their stories. Along with Brenda and the West Coast punks, Punk Rocker features rebels, writers, commentators and street kids from all over America – talking about the music, the fashion, the attitude, the passion, the lifestyle and, of course, the bands who made it all happen. Meet people who discovered punk’s new dawn – and those who were there for its sunset, in the ramshackle mausoleum of the Chelsea Hotel. Backstage, in the clubs, in the gigs, in hotel rooms with the band, on the streets –Brenda was there. She saw it all. And so did her friends. Punk Rocker. If you missed it…what are you waiting for?Available in print and digital formatsPurchase on Amazon

Punk Rocker is the much anticipated sequel to “L.A. Punk Rocker”: top author Brenda Perlin’s best-selling punk anthology. Here you will find a collection of short stories from those who were there in the early days. Hard core musical anarchists who saw it all, heard it all, did it all - and survived to tell their stories. Along with Brenda and the West Coast punks, Punk Rocker features rebels, writers, commentators and street kids from all over America – talking about the music, the fashion, the attitude, the passion, the lifestyle and, of course, the bands who made it all happen. Meet people who discovered punk’s new dawn – and those who were there for its sunset, in the ramshackle mausoleum of the Chelsea Hotel. Backstage, in the clubs, in the gigs, in hotel rooms with the band, on the streets –Brenda was there. She saw it all. And so did her friends. Punk Rocker. If you missed it…what are you waiting for?Available in print and digital formatsPurchase on Amazon

Purchase on Smashwords

Purchase on Barnes and Noble

Purchase on iTunes

Book Signing for PUNK ROCKER & unreleased L.A. PUNK SNAPSHOTS at Book Soup Friday August 5th at 7pm!

8818 W Sunset Blvd, West Hollywood, CA · (310) 659-3110

Punk Rocker is the much anticipated sequel to “L.A. Punk Rocker”: top author Brenda Perlin’s best-selling punk anthology. Here you will find a collection of short stories from those who were there in the early days. Hard core musical anarchists who saw it all, heard it all, did it all - and survived to tell their stories. Along with Brenda and the West Coast punks, Punk Rocker features rebels, writers, commentators and street kids from all over America – talking about the music, the fashion, the attitude, the passion, the lifestyle and, of course, the bands who made it all happen. Meet people who discovered punk’s new dawn – and those who were there for its sunset, in the ramshackle mausoleum of the Chelsea Hotel. Backstage, in the clubs, in the gigs, in hotel rooms with the band, on the streets –Brenda was there. She saw it all. And so did her friends. Punk Rocker. If you missed it…what are you waiting for?Available in print and digital formatsPurchase on Amazon

Punk Rocker is the much anticipated sequel to “L.A. Punk Rocker”: top author Brenda Perlin’s best-selling punk anthology. Here you will find a collection of short stories from those who were there in the early days. Hard core musical anarchists who saw it all, heard it all, did it all - and survived to tell their stories. Along with Brenda and the West Coast punks, Punk Rocker features rebels, writers, commentators and street kids from all over America – talking about the music, the fashion, the attitude, the passion, the lifestyle and, of course, the bands who made it all happen. Meet people who discovered punk’s new dawn – and those who were there for its sunset, in the ramshackle mausoleum of the Chelsea Hotel. Backstage, in the clubs, in the gigs, in hotel rooms with the band, on the streets –Brenda was there. She saw it all. And so did her friends. Punk Rocker. If you missed it…what are you waiting for?Available in print and digital formatsPurchase on AmazonPurchase on Smashwords

Purchase on Barnes and Noble

Purchase on iTunes

Published on May 27, 2016 12:07

A New Lead in the Search for Elusive Norse Settlements

Ancient Origins

By Tara MacIsaac, Epoch Times

CODROY VALLEY, Canada – A story passed down in my family for generations may be the clue to finding a lost Norse settlement.

The only Norse settlement in the New World thus far confirmed by archaeologists is in L’Anse aux Meadows at the northern tip of Newfoundland, Canada. But the Norse sagas tell of other colonizing expeditions.

Last summer, archaeologists announced they found evidence of a Norse presence–a hearth used for roasting bog iron ore, which is the first step in the production of iron–at Point Rosee in southern Newfoundland. My uncle, Wayne MacIsaac, was so excited he said he didn’t sleep for three days. He felt vindicated in his long-cherished, but long-ignored, theory that he had found an ancient Norse site in the nearby Codroy Valley where he lives.

His previous attempts to attract the interest of archaeologists to the site had met with failure, but that has now changed. An international team of archaeologists are due to investigate in July.

Wayne MacIsaac stands near what he believes may be the remnants of a Norse fortification wall. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)A Strange BoatMy great-grandfather, MacIsaac’s grandfather, used to tell of a strange boat that was found in the Codroy Valley when he was a child. A storm had shifted a sandbar at the mouth of the Little Codroy River, revealing a plank-built boat that did not match any shipbuilding style known to the locals.

Wayne MacIsaac stands near what he believes may be the remnants of a Norse fortification wall. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)A Strange BoatMy great-grandfather, MacIsaac’s grandfather, used to tell of a strange boat that was found in the Codroy Valley when he was a child. A storm had shifted a sandbar at the mouth of the Little Codroy River, revealing a plank-built boat that did not match any shipbuilding style known to the locals.

Three tall human skeletons were found underneath it, along with a stone arrowhead.

In that day, no one considered preserving it as an archaeological artifact. But when MacIsaac took an interest in the Norse sagas, he began to see astounding parallels between the descriptions of a Norse settlement and the area the boat was found.

Three Norsemen at the settlement were said to have been killed by natives. MacIsaac wondered whether the three skeletons were those settlers. The stone arrowhead could suggest they were killed by native bowmen.

Local natives only made boats of animal hide or birch bark, suggesting the plank-built boat was of European origin. Yet it didn’t resemble anything known by the local French, Irish, Scottish, or English settlers of my great-grandfather’s time.

MacIsaac found that the sagas describe a mountain range extending north from the settlement. The Long Range mountains indeed extend north from the Codroy Valley. The sagas also describe a river that flows into a lake, which then flows into the sea, and a sandbar that could only be crossed at high tide.

All of this, as well as other details in the sagas, describe a part of the Codroy Valley. MacIsaac went to the spot he felt best matched the description and found what he believes could be remnants of the settlement.

The view from part of what Wayne MacIsaac believes to be a Norse settlement, looking out on a sandbar where a boat that may be of Norse origin was found by locals more than a century ago. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)

The view from part of what Wayne MacIsaac believes to be a Norse settlement, looking out on a sandbar where a boat that may be of Norse origin was found by locals more than a century ago. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times) The Little Codroy River, with the Long Range mountains in the background and the potential site of a Norse settlement visible in the middle-ground, to the left. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)MacIsaac has not disclosed the precise location publicly for fear that amateur archaeologists may disturb the site. But he took me there.

The Little Codroy River, with the Long Range mountains in the background and the potential site of a Norse settlement visible in the middle-ground, to the left. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)MacIsaac has not disclosed the precise location publicly for fear that amateur archaeologists may disturb the site. But he took me there.

He first showed me what he believes may have been a fortifying wall mentioned in the sagas. After 1,000 years, it would be hard for my untrained eye to identify with any certainty a wall possibly built with organic materials.

What I saw was a long, narrow elevation in the ground that extended for dozens of yards, and was some four or more feet high. If it was once a wall, it has been covered with earth and vegetation to the extent that it was difficult to take a photograph of it that conveyed the shape discernible on site.

We moved to another spot, where MacIsaac had found mounds, and particularly a mound that appears unnaturally square in shape.

A square mound believed by Wayne MacIsaac to be evidence of a Norse structure. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)MacIsaac said that, while some of the mounds in the area could be natural, some, including this one, lead him to believe Norse structures existed there. He asked local elderly residents, in their 80s and 90s, whether they knew of any structures built in the area since the Scottish and French had settled there in the early 19th century.

A square mound believed by Wayne MacIsaac to be evidence of a Norse structure. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)MacIsaac said that, while some of the mounds in the area could be natural, some, including this one, lead him to believe Norse structures existed there. He asked local elderly residents, in their 80s and 90s, whether they knew of any structures built in the area since the Scottish and French had settled there in the early 19th century.

They said the land hadn’t been used, suggesting any remnants of structures on the site are not modern.

Contradictory InterpretationsDouglas Bolender, an archaeologist at the University of Massachusetts Boston, investigated the Point Rosee site last summer and talked to MacIsaac at that time. He was intrigued by MacIsaac’s theory.

The settlement the sagas describe was started by Thorfinn Karlsefni (980–1007), who led a colonizing expedition to the New World following its discovery by Leif Eriksson.

A statue of Thorfinn Karlsefni in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (

public domain

)Karlsefni’s settlement is described in the Saga of Eirik the Red:

A statue of Thorfinn Karlsefni in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (

public domain

)Karlsefni’s settlement is described in the Saga of Eirik the Red:

Karlsefni headed south around the coast, with Snorri and Bjarni and the rest of their company. They sailed a long time, until they came to a river which flowed into a lake and from there into the sea. There were wide sandbars stretching out across the mouth of the river and they could only sail into the river at high tide. Karlsefni and his company sailed into the lagoon and called the land Hop (Tidal Pool). There they found fields of self-grown wheat in the low-lying areas and vines growing on the hills. Every stream was teeming with fish. They dug trenches along the high-water mark and when they tide ebbed there were halibut in them. There were a great number of deer of all kinds in the forest.

This passage is from the Keneva Kunz translation in the 1997 Hreinsson volume, Bolender said, which is the main account of Karlsefni’s secondary settlement.

I asked botanists at the Atlantic Canada Conservation Data Centre what they thought of the grape reference. Could it have described a plant existing in Newfoundland 1,000 years ago, particularly in the Codroy Valley area?

Botanist David Mazerolle replied via email: “Our native grape (Riverbank grape, Vitis riparia) does not occur in Newfoundland and, in my opinion, it is highly unlikely that the species would have occurred there 1,000 years ago.

MacIsaac awaits further investigation by archaeologists this summer. He would like to see satellite imagery used in the investigation.

That is how the Point Rosse site was identified. TED awarded archaeologist Sarah Parcak a $1 million prize to use satellite surveillance to discover and monitor ancient sites.

I asked MacIsaac how he will feel if the Codroy Valley site turns out not to have been a Norse settlement after all. He replied: “I will be very disappointed, but I’m trying to be prepared for that, because it is possible it is not what I think it is–despite all the parallels in the sagas, despite the evidence that I see on the site itself, and despite its close proximity to what’s been pretty much confirmed as Norse iron-working.

The article ‘ A New Lead in the Search for Elusive Norse Settlements ’ was originally published on The Epoch Times and has been republished with permission.

By Tara MacIsaac, Epoch Times

CODROY VALLEY, Canada – A story passed down in my family for generations may be the clue to finding a lost Norse settlement.

The only Norse settlement in the New World thus far confirmed by archaeologists is in L’Anse aux Meadows at the northern tip of Newfoundland, Canada. But the Norse sagas tell of other colonizing expeditions.

Last summer, archaeologists announced they found evidence of a Norse presence–a hearth used for roasting bog iron ore, which is the first step in the production of iron–at Point Rosee in southern Newfoundland. My uncle, Wayne MacIsaac, was so excited he said he didn’t sleep for three days. He felt vindicated in his long-cherished, but long-ignored, theory that he had found an ancient Norse site in the nearby Codroy Valley where he lives.

His previous attempts to attract the interest of archaeologists to the site had met with failure, but that has now changed. An international team of archaeologists are due to investigate in July.

Wayne MacIsaac stands near what he believes may be the remnants of a Norse fortification wall. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)A Strange BoatMy great-grandfather, MacIsaac’s grandfather, used to tell of a strange boat that was found in the Codroy Valley when he was a child. A storm had shifted a sandbar at the mouth of the Little Codroy River, revealing a plank-built boat that did not match any shipbuilding style known to the locals.

Wayne MacIsaac stands near what he believes may be the remnants of a Norse fortification wall. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)A Strange BoatMy great-grandfather, MacIsaac’s grandfather, used to tell of a strange boat that was found in the Codroy Valley when he was a child. A storm had shifted a sandbar at the mouth of the Little Codroy River, revealing a plank-built boat that did not match any shipbuilding style known to the locals.Three tall human skeletons were found underneath it, along with a stone arrowhead.

In that day, no one considered preserving it as an archaeological artifact. But when MacIsaac took an interest in the Norse sagas, he began to see astounding parallels between the descriptions of a Norse settlement and the area the boat was found.

Three Norsemen at the settlement were said to have been killed by natives. MacIsaac wondered whether the three skeletons were those settlers. The stone arrowhead could suggest they were killed by native bowmen.

Local natives only made boats of animal hide or birch bark, suggesting the plank-built boat was of European origin. Yet it didn’t resemble anything known by the local French, Irish, Scottish, or English settlers of my great-grandfather’s time.

MacIsaac found that the sagas describe a mountain range extending north from the settlement. The Long Range mountains indeed extend north from the Codroy Valley. The sagas also describe a river that flows into a lake, which then flows into the sea, and a sandbar that could only be crossed at high tide.

All of this, as well as other details in the sagas, describe a part of the Codroy Valley. MacIsaac went to the spot he felt best matched the description and found what he believes could be remnants of the settlement.

The view from part of what Wayne MacIsaac believes to be a Norse settlement, looking out on a sandbar where a boat that may be of Norse origin was found by locals more than a century ago. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)

The view from part of what Wayne MacIsaac believes to be a Norse settlement, looking out on a sandbar where a boat that may be of Norse origin was found by locals more than a century ago. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times) The Little Codroy River, with the Long Range mountains in the background and the potential site of a Norse settlement visible in the middle-ground, to the left. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)MacIsaac has not disclosed the precise location publicly for fear that amateur archaeologists may disturb the site. But he took me there.

The Little Codroy River, with the Long Range mountains in the background and the potential site of a Norse settlement visible in the middle-ground, to the left. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)MacIsaac has not disclosed the precise location publicly for fear that amateur archaeologists may disturb the site. But he took me there.He first showed me what he believes may have been a fortifying wall mentioned in the sagas. After 1,000 years, it would be hard for my untrained eye to identify with any certainty a wall possibly built with organic materials.

What I saw was a long, narrow elevation in the ground that extended for dozens of yards, and was some four or more feet high. If it was once a wall, it has been covered with earth and vegetation to the extent that it was difficult to take a photograph of it that conveyed the shape discernible on site.

We moved to another spot, where MacIsaac had found mounds, and particularly a mound that appears unnaturally square in shape.

A square mound believed by Wayne MacIsaac to be evidence of a Norse structure. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)MacIsaac said that, while some of the mounds in the area could be natural, some, including this one, lead him to believe Norse structures existed there. He asked local elderly residents, in their 80s and 90s, whether they knew of any structures built in the area since the Scottish and French had settled there in the early 19th century.

A square mound believed by Wayne MacIsaac to be evidence of a Norse structure. (Tara MacIsaac/Epoch Times)MacIsaac said that, while some of the mounds in the area could be natural, some, including this one, lead him to believe Norse structures existed there. He asked local elderly residents, in their 80s and 90s, whether they knew of any structures built in the area since the Scottish and French had settled there in the early 19th century.They said the land hadn’t been used, suggesting any remnants of structures on the site are not modern.

Contradictory InterpretationsDouglas Bolender, an archaeologist at the University of Massachusetts Boston, investigated the Point Rosee site last summer and talked to MacIsaac at that time. He was intrigued by MacIsaac’s theory.

“There may be a Norse colony in the Codroy Valley (more work definitely needs to be done),” he wrote to me in an email. “But I wouldn’t base that on the saga descriptions. They’re too vague and contradictory,” he said.MacIsaac said of the sagas: “There are several different versions and different translations, some of them have details the others don’t have.” The details he found to match the Codroy Valley site were picked out of various versions.

The settlement the sagas describe was started by Thorfinn Karlsefni (980–1007), who led a colonizing expedition to the New World following its discovery by Leif Eriksson.

A statue of Thorfinn Karlsefni in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (

public domain

)Karlsefni’s settlement is described in the Saga of Eirik the Red:

A statue of Thorfinn Karlsefni in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (

public domain

)Karlsefni’s settlement is described in the Saga of Eirik the Red:Karlsefni headed south around the coast, with Snorri and Bjarni and the rest of their company. They sailed a long time, until they came to a river which flowed into a lake and from there into the sea. There were wide sandbars stretching out across the mouth of the river and they could only sail into the river at high tide. Karlsefni and his company sailed into the lagoon and called the land Hop (Tidal Pool). There they found fields of self-grown wheat in the low-lying areas and vines growing on the hills. Every stream was teeming with fish. They dug trenches along the high-water mark and when they tide ebbed there were halibut in them. There were a great number of deer of all kinds in the forest.

This passage is from the Keneva Kunz translation in the 1997 Hreinsson volume, Bolender said, which is the main account of Karlsefni’s secondary settlement.

“People have used this text to situate the colony almost anywhere on the American east coast,” Bolender said. “Carl Refn placed these spots in Cape Cod and Rhode Island back in the 1830s. Others have placed them near Boston, in Maine, Nova Scotia, and even on the Pacific coast in British Columbia!”He also noted that the vines mentioned in the story refer to grapes, which don’t grow in Newfoundland.

I asked botanists at the Atlantic Canada Conservation Data Centre what they thought of the grape reference. Could it have described a plant existing in Newfoundland 1,000 years ago, particularly in the Codroy Valley area?

Botanist David Mazerolle replied via email: “Our native grape (Riverbank grape, Vitis riparia) does not occur in Newfoundland and, in my opinion, it is highly unlikely that the species would have occurred there 1,000 years ago.

“A few months ago, I heard of a similar theory, concerning that same mention of a [Norse] settlement in a river valley which had ‘grapes.’ The theory was that this may have been in New Brunswick’s Miramichi River Valley, which does support Riverbank grape.”Botanist Alain Belliveau added to Mazerolle’s response: “Groundnut (Apios americana) is another vine from Atlantic Canada that was an important food source for First Nations and would’ve been grown in river valleys, but its distribution is similar to that of Riverbank grape and it’s highly unlikely that it was in Newfoundland 1,000 years ago.”

MacIsaac awaits further investigation by archaeologists this summer. He would like to see satellite imagery used in the investigation.

That is how the Point Rosse site was identified. TED awarded archaeologist Sarah Parcak a $1 million prize to use satellite surveillance to discover and monitor ancient sites.

I asked MacIsaac how he will feel if the Codroy Valley site turns out not to have been a Norse settlement after all. He replied: “I will be very disappointed, but I’m trying to be prepared for that, because it is possible it is not what I think it is–despite all the parallels in the sagas, despite the evidence that I see on the site itself, and despite its close proximity to what’s been pretty much confirmed as Norse iron-working.

“Maybe it is just natural formations, but I really don’t think it is,” he said.If it turns out to be a Norse site, it would have a substantial impact on the Codroy Valley, a town of some 2,000 residents. Archaeological digs would certainly stir up this small town, and the find could draw tourists.

“I want to see all of that. I have no problem with that whatsoever,” MacIsaac said. “Archaeology is my main interest, but … this place could certainly use some economic spin-off from [tourism].”Top image: Norse explorers. ‘Summer on the Greenland coast circa year 1000’ by Jens Erik Carl Rasmussen (1841–1893) ( public domain )

The article ‘ A New Lead in the Search for Elusive Norse Settlements ’ was originally published on The Epoch Times and has been republished with permission.

Published on May 27, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Procopius executed

May 27

366 Procopius, Roman usurper against Valens, and member of the Constantinian dynasty was executed.

366 Procopius, Roman usurper against Valens, and member of the Constantinian dynasty was executed.

Published on May 27, 2016 02:00

May 26, 2016

Burial Sites Show How Nubians, Egyptians Integrated Communities Thousands of Years Ago

Ancient Origins

New bioarchaeological evidence shows that Nubians and Egyptians integrated into a community, and even married, in ancient Sudan, according to new research from a Purdue University anthropologist.

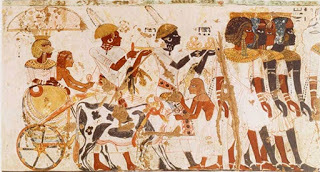

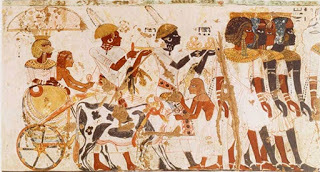

"There are not many archaeological sites that date to this time period, so we have not known what people were doing or what happened to these communities when the Egyptians withdrew," said Michele Buzon, an associate professor of anthropology, who is excavating Nubian burial sites in the Nile River Valley to better understand the relationship between Nubians and Egyptians during the New Kingdom Empire. The findings are published in American Anthropologist, and this work has been funded by the National Science Foundation and the National Geographic Society's Committee for Research and Exploration. Buzon also collaborated with Stuart Tyson Smith from the University of California, Santa Barbara, on this UCSB-Purdue led project. Antonio Simonetti from the University of Notre Dame also is a study co-author. Michele Buzon, a Purdue University associate professor of anthropology, is excavating pyramid tombs in Tombos, Sudan to study Egyptian and Nubian cultures from thousands of years ago in the Nile River Valley. Image credit: Purdue University photo/Charles Jischke Egyptians colonized the area in 1500 BCE to gain access to trade routes on the Nile River. This is known as the New Kingdom Empire, and most research focuses on the Egyptians and their legacy. The Mystery of the Miniature Pyramids of Sudan Tomb of Huy, ruler of Nubia under Tutankhamun, to be opened to the public Location of New Kingdom (CC BY-SA 3.0) "It's been presumed that Nubians absorbed Egyptian cultural features because they had to, but we found cultural entanglement? That there was a new identity that combined aspects of their Nubian and Egyptian heritages. And based on biological and isotopic features, we believe they were interacting, intermarrying and eventually becoming a community of Egyptians and Nubians," said Buzon, who just returned from the excavation site. During the New Kingdom Period, from about 1400-1050 BCE, Egyptians ruled Tombos in the Nile River Valley's Nubian Desert in the far north of Sudan. In about 1050 BCE, the Egyptians lost power during the Third Intermediate Period. At the end of this period, Nubia gained power again and defeated Egypt to rule as the 25th dynasty. Nubian Pharaohs. (Public Domain) "We now have a sense of what happened when the New Kingdom Empire fell apart, and while there had been assumptions that Nubia didn't function very well without the Egyptian administration, the evidence from our site says otherwise," said Buzon, who has been working at this site since 2000, focusing on the burial features and skeletal health analysis. "We found that Tombos continued to be a prosperous community. We have the continuation of an Egyptian Nubian community that is successful even when Egypt is playing no political role there anymore." Human remains and burial practices from 24 units were analyzed for this study. The tombs, known as tumulus graves, show how the cultures merged. The tombs' physical structure, which are mounded, round graves with stones and a shaft underneath, reflect Nubian culture. Ancient Tomb Reveals Cultural Entanglement between Egypt and Nubia The rich history of the ancient Nubian Kingdom of Dongola "They are Nubian in superstructure, but inside the tombs reflect Egyptian cultural features, such as the way the body is positioned," Buzon said. "Egyptians are buried in an extended position; on their back with their arms and legs extended. Nubians are generally on their side with their arms and legs flexed. We found some that combine a mixture of traditions. For instance, bodies were placed on a wooden bed, a Nubian tradition, and then placed in an Egyptian pose in an Egyptian coffin." Aerial view at Nubian pyramids, Meroe (CC BY-SA 1.0) Skeletal markers also supported that the two cultures merged. "This community developed over a few hundred years and people living there were the descendants of that community that started with Egyptian immigrants and local Nubians," Buzon said."They weren't living separately at same site, but living together in the community."

Top image: Nubians bringing tribute to the Pharaoh, from the tomb of Huy. Photo Source: (Exploring Africa)

The article ‘Burial sites show how Nubians, Egyptians integrated communities thousands of years ago ‘was originally published on Science Daily.

Source: Purdue University. "Burial sites show how Nubians, Egyptians integrated communities thousands of years ago." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 18 May 2016. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/05...

New bioarchaeological evidence shows that Nubians and Egyptians integrated into a community, and even married, in ancient Sudan, according to new research from a Purdue University anthropologist.

"There are not many archaeological sites that date to this time period, so we have not known what people were doing or what happened to these communities when the Egyptians withdrew," said Michele Buzon, an associate professor of anthropology, who is excavating Nubian burial sites in the Nile River Valley to better understand the relationship between Nubians and Egyptians during the New Kingdom Empire. The findings are published in American Anthropologist, and this work has been funded by the National Science Foundation and the National Geographic Society's Committee for Research and Exploration. Buzon also collaborated with Stuart Tyson Smith from the University of California, Santa Barbara, on this UCSB-Purdue led project. Antonio Simonetti from the University of Notre Dame also is a study co-author. Michele Buzon, a Purdue University associate professor of anthropology, is excavating pyramid tombs in Tombos, Sudan to study Egyptian and Nubian cultures from thousands of years ago in the Nile River Valley. Image credit: Purdue University photo/Charles Jischke Egyptians colonized the area in 1500 BCE to gain access to trade routes on the Nile River. This is known as the New Kingdom Empire, and most research focuses on the Egyptians and their legacy. The Mystery of the Miniature Pyramids of Sudan Tomb of Huy, ruler of Nubia under Tutankhamun, to be opened to the public Location of New Kingdom (CC BY-SA 3.0) "It's been presumed that Nubians absorbed Egyptian cultural features because they had to, but we found cultural entanglement? That there was a new identity that combined aspects of their Nubian and Egyptian heritages. And based on biological and isotopic features, we believe they were interacting, intermarrying and eventually becoming a community of Egyptians and Nubians," said Buzon, who just returned from the excavation site. During the New Kingdom Period, from about 1400-1050 BCE, Egyptians ruled Tombos in the Nile River Valley's Nubian Desert in the far north of Sudan. In about 1050 BCE, the Egyptians lost power during the Third Intermediate Period. At the end of this period, Nubia gained power again and defeated Egypt to rule as the 25th dynasty. Nubian Pharaohs. (Public Domain) "We now have a sense of what happened when the New Kingdom Empire fell apart, and while there had been assumptions that Nubia didn't function very well without the Egyptian administration, the evidence from our site says otherwise," said Buzon, who has been working at this site since 2000, focusing on the burial features and skeletal health analysis. "We found that Tombos continued to be a prosperous community. We have the continuation of an Egyptian Nubian community that is successful even when Egypt is playing no political role there anymore." Human remains and burial practices from 24 units were analyzed for this study. The tombs, known as tumulus graves, show how the cultures merged. The tombs' physical structure, which are mounded, round graves with stones and a shaft underneath, reflect Nubian culture. Ancient Tomb Reveals Cultural Entanglement between Egypt and Nubia The rich history of the ancient Nubian Kingdom of Dongola "They are Nubian in superstructure, but inside the tombs reflect Egyptian cultural features, such as the way the body is positioned," Buzon said. "Egyptians are buried in an extended position; on their back with their arms and legs extended. Nubians are generally on their side with their arms and legs flexed. We found some that combine a mixture of traditions. For instance, bodies were placed on a wooden bed, a Nubian tradition, and then placed in an Egyptian pose in an Egyptian coffin." Aerial view at Nubian pyramids, Meroe (CC BY-SA 1.0) Skeletal markers also supported that the two cultures merged. "This community developed over a few hundred years and people living there were the descendants of that community that started with Egyptian immigrants and local Nubians," Buzon said."They weren't living separately at same site, but living together in the community."

Top image: Nubians bringing tribute to the Pharaoh, from the tomb of Huy. Photo Source: (Exploring Africa)

The article ‘Burial sites show how Nubians, Egyptians integrated communities thousands of years ago ‘was originally published on Science Daily.

Source: Purdue University. "Burial sites show how Nubians, Egyptians integrated communities thousands of years ago." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 18 May 2016. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/05...

Published on May 26, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - St Augustine dies

May 26

604 St Augustine died. The Benedictine monk became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597. He is considered the "Apostle to the English" and a founder of the English Church.

604 St Augustine died. The Benedictine monk became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597. He is considered the "Apostle to the English" and a founder of the English Church.

Published on May 26, 2016 02:00

May 25, 2016

3,600-Year-Old Town of Treasures Excavated in Gaza

Ancient Origins

A rich trading town dating back about 3,600 years has been under excavation in the Gaza Strip on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Archaeologists have uncovered stunning gold jewelry, scarabs and Cypriot pottery in the town, Tell el-Ajjul, which was on one of the ancient world’s major trade highways.

A rich trading town dating back about 3,600 years has been under excavation in the Gaza Strip on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Archaeologists have uncovered stunning gold jewelry, scarabs and Cypriot pottery in the town, Tell el-Ajjul, which was on one of the ancient world’s major trade highways.

Sponsored by Revenue.com Various peoples fought major wars along the route over the millennia, though it appears the people of Tell el-Ajjul were peaceful.

William M. Flanders Petrie first excavated the town from 1930 to 1934 and found large amounts of pottery, gold objects and other jewelry, many of which are on display in the British Museum.

Gold falcon earring jewelry found at Tell el-Ajjul (

studentreader.com

)Ha’aretz reports (subscription required), that recent excavations have shown that there were more than 500 years of trade between Tell el-Ajjul and other people around the Mediterranean. More than 200 potsherds of a type rarely found outside Cyprus have been uncovered from the ruins, indicating close ties between the people of the town and the island.

Gold falcon earring jewelry found at Tell el-Ajjul (

studentreader.com

)Ha’aretz reports (subscription required), that recent excavations have shown that there were more than 500 years of trade between Tell el-Ajjul and other people around the Mediterranean. More than 200 potsherds of a type rarely found outside Cyprus have been uncovered from the ruins, indicating close ties between the people of the town and the island.

“I was aware of the Cypriot imports from Petrie’s excavations, but when I realised the actual amount of Cypriot imports, I came to the conclusion that Tell el-Ajjul was a trading centre with tight connections to Cyprus, sanctioned by the Egyptian overlord,” Gothenburg University Professor Peter Fischer, head of excavations, told Haaretz.

After arriving in Tell el-Ajjul, Cypriot pottery and copper and bronze items were redistributed in the Levant, including in Transjordan, Ha’aretz says.

Fischer told the Israeli newspaper he believes the great wealth of the tell was from trade surpluses because there are few natural resources in the area except, perhaps, from the fruits of agriculture, including olive oil and wine.

Fischer said he thinks Tell el-Ajjul was the main trading town in the area and it may have had a monopoly on commerce with major trade centers in Cyprus from the Middle through Late Bronze ages. Imports of rich items from Syria, the Jordan Valley, Egypt and Mycenae are evidence of the importance of the trading post from about 1650 to 1300 BC, Ha’aretz says.

The site of Tell el-Ajjul (Google Earth)The tell is situated on the trade route, one of the world’s oldest, called the Via Maris or King’s Highway that connected North Africa with the Levant. It was a site of battles from the time of ancient Egyptian rule, conquest by Philistia, through Alexander the Great’s conquest, the Crusades and up to nearly modern times with Napoleon’s excursions into the region, says Ha’aretz, adding that the list is not exhaustive.

The site of Tell el-Ajjul (Google Earth)The tell is situated on the trade route, one of the world’s oldest, called the Via Maris or King’s Highway that connected North Africa with the Levant. It was a site of battles from the time of ancient Egyptian rule, conquest by Philistia, through Alexander the Great’s conquest, the Crusades and up to nearly modern times with Napoleon’s excursions into the region, says Ha’aretz, adding that the list is not exhaustive.

The famous Via Maris road running between the empires of the Fertile Crescent to the north and east and Egypt to the south and west (

saffold.com

)It is unknown who ruled the trade town. Experts have speculated that during the Middle Bronze Age the rulers were sovereign kings or governors, Ha’artez says, dispatched from the Egyptian Hyksos capital of Avaris in the Nile Delta. But later, around 1500 BC when the Hyksos Dynasty was overthrown, it seems Egyptian governors of the 18th and 19th dynasties may have assumed control.

The famous Via Maris road running between the empires of the Fertile Crescent to the north and east and Egypt to the south and west (

saffold.com

)It is unknown who ruled the trade town. Experts have speculated that during the Middle Bronze Age the rulers were sovereign kings or governors, Ha’artez says, dispatched from the Egyptian Hyksos capital of Avaris in the Nile Delta. But later, around 1500 BC when the Hyksos Dynasty was overthrown, it seems Egyptian governors of the 18th and 19th dynasties may have assumed control.

“Fischer believes Tell el-Ajjul is identical with Sharuhen, where according to Egyptian sources the Hyksos fled after being expelled from Egypt by Pharaoh Ahmose I,” Ha’aretz states.

Fischer said: “Most of the more than 1300 scarabs from Tell el-Ajjul were locally produced and represent trading goods which one can find everywhere in the Levant, including Transjordan. However, there are also genuine Egyptian scarabs at Tell el Ajjul.”

There was a large amount of deluxe pottery at Tell el-Ajjul, most of it imported from Cyprus, one of the major pottery manufacturers of the Eastern Aegean. It appears the people of Tell el-Ajjul traded Canaanite jars with wine, oil and incense for the luxury pottery of Cyprus, Ha’aretz states.

Unfortunately, says the article in Ha’aretz homes are now being constructed on the ruins of the ancient town, which threatens efforts to do proper excavations and may even destroy it. The population of Gaza is 1.87 million as of 2015. The people live on 141 square miles, so space is cramped, and they don’t have enough money to build high-rise apartment buildings.

Fischer told Ha’aretz he fears the entire tell may be destroyed by the new construction. And excavations of the tell were halted in 2011 because of Egyptian and Israeli restrictions.

"There are new houses everywhere on the tell. In consequence, I am very pessimistic that Tell el-Ajjul can be saved for future generations. Believe me, I have tried,” he told the newspaper.

Top image: Main: Excavating at Tel el-Ajjul, Gaza. Credit: Peter M. Fischer . Inset: Gold crescent shaped earring jewelry found at Tell el-Ajjul.

By Mark Miller

A rich trading town dating back about 3,600 years has been under excavation in the Gaza Strip on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Archaeologists have uncovered stunning gold jewelry, scarabs and Cypriot pottery in the town, Tell el-Ajjul, which was on one of the ancient world’s major trade highways.

A rich trading town dating back about 3,600 years has been under excavation in the Gaza Strip on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Archaeologists have uncovered stunning gold jewelry, scarabs and Cypriot pottery in the town, Tell el-Ajjul, which was on one of the ancient world’s major trade highways.Sponsored by Revenue.com Various peoples fought major wars along the route over the millennia, though it appears the people of Tell el-Ajjul were peaceful.

William M. Flanders Petrie first excavated the town from 1930 to 1934 and found large amounts of pottery, gold objects and other jewelry, many of which are on display in the British Museum.

Gold falcon earring jewelry found at Tell el-Ajjul (

studentreader.com

)Ha’aretz reports (subscription required), that recent excavations have shown that there were more than 500 years of trade between Tell el-Ajjul and other people around the Mediterranean. More than 200 potsherds of a type rarely found outside Cyprus have been uncovered from the ruins, indicating close ties between the people of the town and the island.

Gold falcon earring jewelry found at Tell el-Ajjul (

studentreader.com

)Ha’aretz reports (subscription required), that recent excavations have shown that there were more than 500 years of trade between Tell el-Ajjul and other people around the Mediterranean. More than 200 potsherds of a type rarely found outside Cyprus have been uncovered from the ruins, indicating close ties between the people of the town and the island.“I was aware of the Cypriot imports from Petrie’s excavations, but when I realised the actual amount of Cypriot imports, I came to the conclusion that Tell el-Ajjul was a trading centre with tight connections to Cyprus, sanctioned by the Egyptian overlord,” Gothenburg University Professor Peter Fischer, head of excavations, told Haaretz.

After arriving in Tell el-Ajjul, Cypriot pottery and copper and bronze items were redistributed in the Levant, including in Transjordan, Ha’aretz says.

Fischer told the Israeli newspaper he believes the great wealth of the tell was from trade surpluses because there are few natural resources in the area except, perhaps, from the fruits of agriculture, including olive oil and wine.

Fischer said he thinks Tell el-Ajjul was the main trading town in the area and it may have had a monopoly on commerce with major trade centers in Cyprus from the Middle through Late Bronze ages. Imports of rich items from Syria, the Jordan Valley, Egypt and Mycenae are evidence of the importance of the trading post from about 1650 to 1300 BC, Ha’aretz says.

The site of Tell el-Ajjul (Google Earth)The tell is situated on the trade route, one of the world’s oldest, called the Via Maris or King’s Highway that connected North Africa with the Levant. It was a site of battles from the time of ancient Egyptian rule, conquest by Philistia, through Alexander the Great’s conquest, the Crusades and up to nearly modern times with Napoleon’s excursions into the region, says Ha’aretz, adding that the list is not exhaustive.

The site of Tell el-Ajjul (Google Earth)The tell is situated on the trade route, one of the world’s oldest, called the Via Maris or King’s Highway that connected North Africa with the Levant. It was a site of battles from the time of ancient Egyptian rule, conquest by Philistia, through Alexander the Great’s conquest, the Crusades and up to nearly modern times with Napoleon’s excursions into the region, says Ha’aretz, adding that the list is not exhaustive. The famous Via Maris road running between the empires of the Fertile Crescent to the north and east and Egypt to the south and west (

saffold.com

)It is unknown who ruled the trade town. Experts have speculated that during the Middle Bronze Age the rulers were sovereign kings or governors, Ha’artez says, dispatched from the Egyptian Hyksos capital of Avaris in the Nile Delta. But later, around 1500 BC when the Hyksos Dynasty was overthrown, it seems Egyptian governors of the 18th and 19th dynasties may have assumed control.

The famous Via Maris road running between the empires of the Fertile Crescent to the north and east and Egypt to the south and west (

saffold.com

)It is unknown who ruled the trade town. Experts have speculated that during the Middle Bronze Age the rulers were sovereign kings or governors, Ha’artez says, dispatched from the Egyptian Hyksos capital of Avaris in the Nile Delta. But later, around 1500 BC when the Hyksos Dynasty was overthrown, it seems Egyptian governors of the 18th and 19th dynasties may have assumed control.“Fischer believes Tell el-Ajjul is identical with Sharuhen, where according to Egyptian sources the Hyksos fled after being expelled from Egypt by Pharaoh Ahmose I,” Ha’aretz states.

Fischer said: “Most of the more than 1300 scarabs from Tell el-Ajjul were locally produced and represent trading goods which one can find everywhere in the Levant, including Transjordan. However, there are also genuine Egyptian scarabs at Tell el Ajjul.”

There was a large amount of deluxe pottery at Tell el-Ajjul, most of it imported from Cyprus, one of the major pottery manufacturers of the Eastern Aegean. It appears the people of Tell el-Ajjul traded Canaanite jars with wine, oil and incense for the luxury pottery of Cyprus, Ha’aretz states.

Unfortunately, says the article in Ha’aretz homes are now being constructed on the ruins of the ancient town, which threatens efforts to do proper excavations and may even destroy it. The population of Gaza is 1.87 million as of 2015. The people live on 141 square miles, so space is cramped, and they don’t have enough money to build high-rise apartment buildings.

Fischer told Ha’aretz he fears the entire tell may be destroyed by the new construction. And excavations of the tell were halted in 2011 because of Egyptian and Israeli restrictions.

"There are new houses everywhere on the tell. In consequence, I am very pessimistic that Tell el-Ajjul can be saved for future generations. Believe me, I have tried,” he told the newspaper.

Top image: Main: Excavating at Tel el-Ajjul, Gaza. Credit: Peter M. Fischer . Inset: Gold crescent shaped earring jewelry found at Tell el-Ajjul.

By Mark Miller

Published on May 25, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Thales of Greece predicts solar eclipse

Published on May 25, 2016 02:00

May 24, 2016

Why did Anne Boleyn have to die?

History Extra

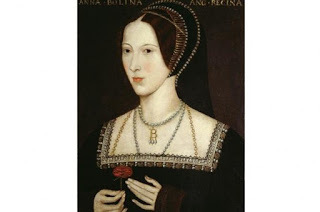

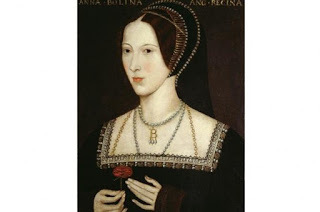

The most familiar depictions of Anne Boleyn are various reproductions of this glamorous portrait, in which she wears the famous B-pendant. The earliest dates from 50–60 years after Anne’s death, though they may derive from a portrait, now missing, produced in her lifetime. (Copyright NPG)

The most familiar depictions of Anne Boleyn are various reproductions of this glamorous portrait, in which she wears the famous B-pendant. The earliest dates from 50–60 years after Anne’s death, though they may derive from a portrait, now missing, produced in her lifetime. (Copyright NPG)

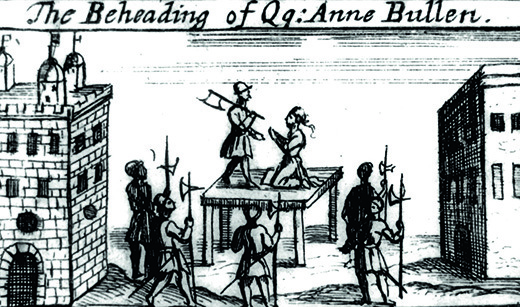

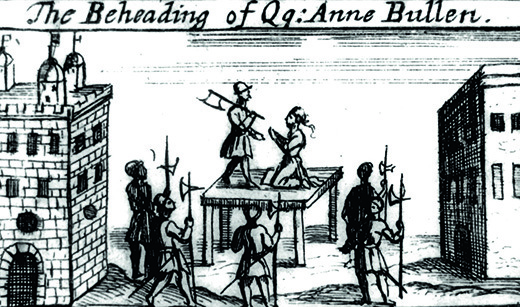

On the morning of 19 May 1536, Anne Boleyn climbed the scaffold erected on Tower Green, within the walls of the Tower of London. She gave a speech praising the goodness and mercy of the king, and asked those gathered to pray for her. Then she removed her fine, ermine-trimmed gown, and knelt down – and the expensive French executioner that Henry VIII had ordered swung his sword and “divided her neck at a blow”.

Her death is so familiar to us that it is hard to imagine how shocking it would have been: the queen of England executed on charges of adultery, incest and conspiring the king’s death. And not just any queen: this was the woman for whom Henry VIII had abandoned his wife of nearly 24 years, waited seven long years to wed, and even revolutionised his country’s church. Yet just three years later her head was off – and the reason for her death remains one of the great mysteries of English history.

To this day, historians cannot agree why she had to die. Had Henry and Anne’s relationship gone into terminal decline, prompting Henry to invent the charges against his wife? Was Thomas Cromwell responsible for Anne’s demise? Or was she indeed guilty of the charges laid against her? Evidence is limited – but there is enough to appear to support several very different conclusions.

There are a number of undisputed facts relating to Anne’s fall. On Sunday 30 April 1536 Mark Smeaton, a musician from the queen’s household, was arrested; he was then interrogated at Cromwell’s house in Stepney. On the same evening the king postponed a trip with Anne to Calais, planned for 2 May.

The next day, 1 May, Smeaton was moved to the Tower. Henry attended the May Day jousts at Greenwich but left abruptly on horseback with a small group of intimates. These included Sir Henry Norris, a personal body servant and one of his closest friends, whom he questioned throughout the journey. At dawn the next day Norris was taken to the Tower. Anne and her brother George, Lord Rochford, were also arrested.

On 4 and 5 May, more courtiers from the king’s privy chamber – William Brereton, Richard Page, Francis Weston, Thomas Wyatt and Francis Bryan – were arrested. The latter was questioned and released, but the others were imprisoned in the Tower. On 10 May, a grand jury indicted all of the accused, apart from Page and Wyatt.

On 12 May, Smeaton, Brereton, Weston and Norris were tried and found guilty of adultery with the queen, and of conspiring the king’s death. On 15 May, Anne and Rochford were tried within the Tower by a court of 26 peers presided over by their uncle, the Duke of Norfolk. Both were found guilty of high treason. On 17 May Archbishop Thomas Cranmer declared the marriage of Henry and Anne null, and by 19 May, all six convicted had been executed. Later that day, Cranmer issued a dispensation allowing Henry and Jane Seymour to marry; they were betrothed on 20 May and married 10 days later.

What could explain this rapid and surprising turn of events? The first theory, argued by Boleyn biographer and scholar GW Bernard, is simply that Anne was guilty of the charges against her. Yet even he is equivocal, suggesting the Scottish legal verdict of ‘not proven’ – he concludes that, though the evidence is insufficient to prove definitively that Anne and those accused with her were guilty, neither does it prove their innocence.

Anne’s guilt was, naturally, the official line. Writing to the bishop of Winchester, Stephen Gardiner, Cromwell stated with certainty – before Anne’s trial – that “the queen’s incontinent living was so rank and common that the ladies of her privy chamber could not conceal it.”

The key piece of evidence was undoubtedly the confession by the first man accused, Smeaton, that he had had sexual intercourse with the queen three times. Though it was probably obtained under torture (the accounts vary), he never retracted his confession. Unlikely as it was to be true, it catapulted the investigation to a different, far more serious level. All subsequent evidence was tainted with a presumption of guilt. Henry VIII’s intimate questioning of Norris, and his promise of “pardon in case he would utter the truth”, must be understood in this light: whatever Norris said, or refused to say, it reinforced Henry’s conviction of his guilt.

Other evidence for Anne’s guilt is unclear – the trial documents do not survive. Her indictment, however, states that Anne “did falsely and traitoroysly procure by base conversations and kisses, touchings, gifts and other infamous incitations, divers of the king’s daily and familiar servants to be her adulterers and concubines, so that several… yielded to her vile provocations”. She even, it charges, “procured and incited her own natural brother… to violate her, alluring him with her tongue in the said George’s mouth, and the said George’s tongue in hers”. Yet, as another Boleyn biographer Eric Ives noted, three-quarters of the specific accusations of adulterous liaisons made in the indictment can be discredited, even 500 years later.

True wedded wifeCertainly, Anne maintained her innocence. During her imprisonment Sir William Kingston, constable of the Tower, reported Anne’s remarks to Cromwell. His first letter details Anne’s ardent declaration of innocence: “I am as clear from the company of man, as for sin… as I am clear from you, and the king’s true wedded wife.”

A few days later, Anne comforted herself that she would have justice: “She said if any man accuse me I can say but nay, and they can bring no witness.” Crucially, the night before her execution, she swore “on peril of her soul’s damnation”, before and after receiving the Eucharist, that she was innocent – a serious act in that religious age.

Édouard Cibot’s painting of 1835 depicts Anne imprisoned in the Tower of London. The queen protested her innocence until the end. (Copyright Bridgeman Art Library)

Anne was not alone in professing her innocence. As Sir Edward Baynton put it: “No man will confess any thing against her, but only Mark of any actual thing.” And even Eustace Chapuys, ambassador for the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and Anne’s arch-enemy, would finally conclude that everyone besides Smeaton was “condemned upon presumption and certain indications, without valid proof or confession”.

Another set of historians have favoured the explanation that Anne was the victim of a conspiracy by Thomas Cromwell and a court faction involving the Seymours. This rests upon a view of Henry as a pliable king whose courtiers could “bounce” him into action and tip him “by a crisis” into rejecting Anne. But why should Anne and Cromwell, erstwhile allies of a reformist bent, fall out? Differences of opinion are thought to have arisen over the use of funds from the dissolution of the monasteries, as well as matters of foreign policy – seemingly slender motives for destroying a queen.

It has been suggested that Cromwell’s court faction intended to replace Anne with Jane Seymour. Chapuys mentioned Jane in a letter of 10 February 1536, reporting that Henry had sent her a gift of a purse full of sovereigns, accompanied by a letter. She did not open the letter, which – Ives speculated – contained a summons to the royal bed. Instead, she kissed it and returned it, asking the messenger to tell the king that “there was no treasure in this world that she valued as much as her honour,” and that if the king wanted to give her a present, she begged it might be at “such a time as God would be pleased to send her some advantageous marriage”.

Such a calculated reply is reminiscent of Anne during the days of her courtship with Henry. In response to Jane’s coyness, Henry’s love for her was said to have “marvellously increased”. Yet she was described as a lady whom the king “serves” – a telling word implying that he sought her as his ‘courtly love’ mistress. There is little evidence that, before Anne was accused of adultery, Henry had planned to make Jane his wife. Marriage to Jane was, surely, a symptom and a product of Anne’s downfall, not a cause.

The pivotal piece of evidence for a conspiracy is a remark made by Cromwell to Chapuys after Anne’s death. In a letter to Charles V, Chapuys wrote that Cromwell had told him “il se mist a fantasier et conspirer le dict affaire,” which has been translated as “he set himself to devise and conspire the said affair,” suggesting that Cromwell plotted against Anne.

Crucially, however, this phrase is often used out of context. The previous sentence states that “he himself [Cromwell] had been authorised and commissioned by the king to prosecute and bring to an end the mistress’s trial, to do which he had taken considerable trouble.” If we accept this account, it is impossible to dismiss Henry VIII from the picture – Cromwell claimed not to be acting alone.

It has been proposed, therefore, that Henry asked Cromwell to get rid of Anne. David Starkey suggested that “Anne’s proud and abrasive character soon became intolerable to her husband”. JJ Scarisbrick, author of the authoritative volume Henry VIII, agreed: “What had once been devastating infatuation turned into bloodthirsty loathing, for reasons we will never completely know.”

Lovers’ quarrelsEvidence for this view is taken from the writings of the ever-hopeful Chapuys. As a Catholic and a supporter of Catherine of Aragon, he referred to Anne as “the concubine” or “the she-devil”, and had made bitter assertions about the doomed state of Henry and Anne’s relationship even at the height of their happiness in late summer 1533. But Chapuys himself recognised that Henry and Anne had always been prone to “lovers’ quarrels”, and that the king’s character was very “changeable”.

True, Henry and Anne were direct with each other: they got angry, shouted and became jealous. But they were also frequently described as being “merry” together; it was an epithet still being applied to them during the autumn of 1535 – and one that was appended to their marriage more often than to any of Henry’s other unions. Bernard has described theirs as a “tumultuous relationship of sunshine and storms”.

Some have proposed that the miscarriage of a male foetus suffered by Anne in January 1536 led inexorably to her downfall. Did it cause Henry to believe that Anne would never be able to bear him an heir, and thus to consider the marriage doomed? Certainly, the king was reported to have shown “great disappointment and sorrow”. Chapuys wrote that Henry, during his visit to Anne’s chamber after the tragedy, said very little except: “I see that God will not give me male children.”

Henry then left Anne at Greenwich to convalesce while he went to Whitehall to mark the feast day of St Matthew. Chapuys, rather maliciously, interpreted this as showing that Henry had abandoned Anne, “whereas in former times he could hardly be one hour without her”. Clearly, the miscarriage was a great blow to both Henry and Anne – yet another four months were to pass before Anne’s death, so demonstrating a direct link between the events would be problematic.

Another story, reported third-hand by Chapuys, quotes Henry as telling an unidentified courtier that he had married Anne “seduced and constrained by sortilèges”. That last word translates as ‘sorcery, spells, charms’, and has given rise to the suggestion that Anne Boleyn dabbled in witchcraft. Though this is regularly cited as one of the charges of which she was found guilty, it is not mentioned in the indictment.

Ives, though, pointed out that the primary English meaning of sortilèges at this time was ‘divination’, a translation that changes the meaning of Henry’s comment. It could imply that he was induced to marry Anne by premarital prophecies that she would bear sons, or could refer simply to Henry’s earlier infatuation or ‘bewitchment’ by Anne.

The idea that Henry had been “seduced by witchcraft” has become attached to another theory, which holds that the real reason for Anne’s ruin was that the foetus miscarried in January 1536 was deformed. According to Tudor specialist Retha Warnicke, the delivery of a “shapeless mass of flesh” proved in Henry’s mind that Anne was both a witch and adulterously promiscuous. But this description comes from a Catholic propagandist, Nicholas Sander, writing 50 years later; there is no contemporary evidence to sustain this salacious theory.

Anne receives the news of her death sentence in an 1814 painting by Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret, now in the Louvre. (Copyright AKG)

Diplomatic coupAn event in April 1536 suggests that, just weeks before Anne was executed, Henry was still committed to his marriage. In the early months of 1536, Henry was increasing the pressure on Charles V to recognise Anne as his wife. On 18 April he invited Chapuys to the court. Events that day were very deliberately staged: the ambassador attended mass and, as Henry and Anne descended from the royal pew to the chapel, she stopped and bowed to Chapuys.

Etiquette dictated that he return the gesture – a significant diplomatic coup, because it implied recognition by the ambassador and, by extension, his emperor. It would, as Bernard has argued, have been extraordinarily capricious of Henry to seek to have Anne recognised as his wife if he already harboured intentions of ridding himself of her soon after.

So was it not guilt, nor a court coup, nor Henry’s hatred of Anne that led to her downfall but, rather, a terrible combination of malicious gossip and her own indiscretions?

A poetic account written in June 1536 by Lancelot de Carles, secretary to the French ambassador, relates that one of Anne’s ladies-in-waiting, Elizabeth Browne, was accused of loose living. She made light of her own guilt by stating that “it was little in her case in comparison with that of the queen”. These words reached Cromwell who, according to de Carles, reported them to Henry; the king blanched and, very reluctantly, ordered him to investigate.

This certainly aligns with Cromwell’s own retelling of the events. De Carles adds a crucial, though unsubstantiated, clause, Henry telling Cromwell that “if it turns out that your report, which I do not wish to believe, is untrue, you will receive pain of death in place of [the accused]”. So Cromwell may have had reason to find evidence of Anne’s guilt.

Given that Anne was accused of conspiring the king’s death (the only charge that actually constituted treason – consensual adultery was not covered by the treason law of 1352), it seems likely that the evidence used to demonstrate her guilt was a conversation she recalled – and William Kingston reported – with Norris.

Anne had asked Norris why he did not go through with his marriage. He had replied that “he wold tary a time,” leading her to taunt him with the fateful words “you loke for ded men’s showys; for yf owth cam to the King but good, you would loke to have me.” Norris’s flustered response – that “yf he should have any such thought, he wold hys hed war of” – provoked her to retort that “she could undo him if she would,” and “ther with thay felle yowt” (“there with they fell out”.)

It might seem that this overstepped the normal boundaries of ‘courtly love’ talk only a little. But the Treasons Act of 1534 held that even imagining the death of the king was treasonous, so Anne’s conversation with Norris was charged, reckless and, arguably, fatal – useful ammunition if Cromwell were looking for dirt. Was it, as Greg Walker (author of Writing Under Tyranny) has suggested, not what Anne did but what she said that made her appear guilty?

When it comes to Anne Boleyn’s fall, historians give their ‘best guess’ answers on the basis of the available evidence – which is too sparse to be conclusive. For my part, it is the final ‘cock-up theory’ that convinces me. I believe that Anne was innocent, but caught out by her careless words. Henry was convinced by the charges against her; it was a devastating blow from which he never recovered. For Anne, of course, the consequences were far more terrible.

Timeline: The rise and fall of Anne Boleyn1501 (or possibly 1507): The birth

Anne is born at Blickling, Norfolk, to Thomas Boleyn and his wife, Elizabeth (daughter of Thomas Howard, later second Duke of Norfolk). Historians debate whether Anne was born in 1501 or 1507; the former is more plausible

1513: The first post

Anne is appointed a maid-of-honour at the court of Margaret, archduchess of Austria; she later leaves to serve Mary, queen of France, wife of Louis XII (and Henry VIII’s sister). After Louis’ death, Anne remains at the court of the new French queen, Claude, for seven years

1521: The repatriation

Anne is recalled to England by her father

1 March 1522: The court appearance

Anne makes her first recorded appearance at Henry VIII’s court, playing the part of Perseverance in a Shrove Tuesday pageant. At that time, Henry was having an affair with Anne’s sister, Mary

c1526: The object of love

Henry VIII falls in love with Anne. A letter from him, dated to 1527, states that for more than one year Henry had been “struck by the dart of love” and asks Anne to “give herself body and heart to him”

1532/33: The royal wedding

Anne marries Henry. The official wedding is held in January 1533, but they are probably married secretly at Dover in October 1532. Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon is not annulled until May 1533

7 September 1533: The birth

Anne gives birth to a daughter, Elizabeth

29 January 1536: The miscarriage

Anne miscarries a male foetus

2 May 1536: The accusations

Anne is arrested and taken to the Tower, along with her brother George Boleyn, Lord Rochford

19 May 1536: The execution

Anne is beheaded on Tower Green within the Tower of London

Suzannah Lipscomb is a leading Tudor historian, author and broadcaster.

The most familiar depictions of Anne Boleyn are various reproductions of this glamorous portrait, in which she wears the famous B-pendant. The earliest dates from 50–60 years after Anne’s death, though they may derive from a portrait, now missing, produced in her lifetime. (Copyright NPG)

The most familiar depictions of Anne Boleyn are various reproductions of this glamorous portrait, in which she wears the famous B-pendant. The earliest dates from 50–60 years after Anne’s death, though they may derive from a portrait, now missing, produced in her lifetime. (Copyright NPG) On the morning of 19 May 1536, Anne Boleyn climbed the scaffold erected on Tower Green, within the walls of the Tower of London. She gave a speech praising the goodness and mercy of the king, and asked those gathered to pray for her. Then she removed her fine, ermine-trimmed gown, and knelt down – and the expensive French executioner that Henry VIII had ordered swung his sword and “divided her neck at a blow”.

Her death is so familiar to us that it is hard to imagine how shocking it would have been: the queen of England executed on charges of adultery, incest and conspiring the king’s death. And not just any queen: this was the woman for whom Henry VIII had abandoned his wife of nearly 24 years, waited seven long years to wed, and even revolutionised his country’s church. Yet just three years later her head was off – and the reason for her death remains one of the great mysteries of English history.

To this day, historians cannot agree why she had to die. Had Henry and Anne’s relationship gone into terminal decline, prompting Henry to invent the charges against his wife? Was Thomas Cromwell responsible for Anne’s demise? Or was she indeed guilty of the charges laid against her? Evidence is limited – but there is enough to appear to support several very different conclusions.

There are a number of undisputed facts relating to Anne’s fall. On Sunday 30 April 1536 Mark Smeaton, a musician from the queen’s household, was arrested; he was then interrogated at Cromwell’s house in Stepney. On the same evening the king postponed a trip with Anne to Calais, planned for 2 May.

The next day, 1 May, Smeaton was moved to the Tower. Henry attended the May Day jousts at Greenwich but left abruptly on horseback with a small group of intimates. These included Sir Henry Norris, a personal body servant and one of his closest friends, whom he questioned throughout the journey. At dawn the next day Norris was taken to the Tower. Anne and her brother George, Lord Rochford, were also arrested.

On 4 and 5 May, more courtiers from the king’s privy chamber – William Brereton, Richard Page, Francis Weston, Thomas Wyatt and Francis Bryan – were arrested. The latter was questioned and released, but the others were imprisoned in the Tower. On 10 May, a grand jury indicted all of the accused, apart from Page and Wyatt.

On 12 May, Smeaton, Brereton, Weston and Norris were tried and found guilty of adultery with the queen, and of conspiring the king’s death. On 15 May, Anne and Rochford were tried within the Tower by a court of 26 peers presided over by their uncle, the Duke of Norfolk. Both were found guilty of high treason. On 17 May Archbishop Thomas Cranmer declared the marriage of Henry and Anne null, and by 19 May, all six convicted had been executed. Later that day, Cranmer issued a dispensation allowing Henry and Jane Seymour to marry; they were betrothed on 20 May and married 10 days later.

What could explain this rapid and surprising turn of events? The first theory, argued by Boleyn biographer and scholar GW Bernard, is simply that Anne was guilty of the charges against her. Yet even he is equivocal, suggesting the Scottish legal verdict of ‘not proven’ – he concludes that, though the evidence is insufficient to prove definitively that Anne and those accused with her were guilty, neither does it prove their innocence.

Anne’s guilt was, naturally, the official line. Writing to the bishop of Winchester, Stephen Gardiner, Cromwell stated with certainty – before Anne’s trial – that “the queen’s incontinent living was so rank and common that the ladies of her privy chamber could not conceal it.”

The key piece of evidence was undoubtedly the confession by the first man accused, Smeaton, that he had had sexual intercourse with the queen three times. Though it was probably obtained under torture (the accounts vary), he never retracted his confession. Unlikely as it was to be true, it catapulted the investigation to a different, far more serious level. All subsequent evidence was tainted with a presumption of guilt. Henry VIII’s intimate questioning of Norris, and his promise of “pardon in case he would utter the truth”, must be understood in this light: whatever Norris said, or refused to say, it reinforced Henry’s conviction of his guilt.

Other evidence for Anne’s guilt is unclear – the trial documents do not survive. Her indictment, however, states that Anne “did falsely and traitoroysly procure by base conversations and kisses, touchings, gifts and other infamous incitations, divers of the king’s daily and familiar servants to be her adulterers and concubines, so that several… yielded to her vile provocations”. She even, it charges, “procured and incited her own natural brother… to violate her, alluring him with her tongue in the said George’s mouth, and the said George’s tongue in hers”. Yet, as another Boleyn biographer Eric Ives noted, three-quarters of the specific accusations of adulterous liaisons made in the indictment can be discredited, even 500 years later.

True wedded wifeCertainly, Anne maintained her innocence. During her imprisonment Sir William Kingston, constable of the Tower, reported Anne’s remarks to Cromwell. His first letter details Anne’s ardent declaration of innocence: “I am as clear from the company of man, as for sin… as I am clear from you, and the king’s true wedded wife.”

A few days later, Anne comforted herself that she would have justice: “She said if any man accuse me I can say but nay, and they can bring no witness.” Crucially, the night before her execution, she swore “on peril of her soul’s damnation”, before and after receiving the Eucharist, that she was innocent – a serious act in that religious age.

Édouard Cibot’s painting of 1835 depicts Anne imprisoned in the Tower of London. The queen protested her innocence until the end. (Copyright Bridgeman Art Library)

Anne was not alone in professing her innocence. As Sir Edward Baynton put it: “No man will confess any thing against her, but only Mark of any actual thing.” And even Eustace Chapuys, ambassador for the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and Anne’s arch-enemy, would finally conclude that everyone besides Smeaton was “condemned upon presumption and certain indications, without valid proof or confession”.

Another set of historians have favoured the explanation that Anne was the victim of a conspiracy by Thomas Cromwell and a court faction involving the Seymours. This rests upon a view of Henry as a pliable king whose courtiers could “bounce” him into action and tip him “by a crisis” into rejecting Anne. But why should Anne and Cromwell, erstwhile allies of a reformist bent, fall out? Differences of opinion are thought to have arisen over the use of funds from the dissolution of the monasteries, as well as matters of foreign policy – seemingly slender motives for destroying a queen.

It has been suggested that Cromwell’s court faction intended to replace Anne with Jane Seymour. Chapuys mentioned Jane in a letter of 10 February 1536, reporting that Henry had sent her a gift of a purse full of sovereigns, accompanied by a letter. She did not open the letter, which – Ives speculated – contained a summons to the royal bed. Instead, she kissed it and returned it, asking the messenger to tell the king that “there was no treasure in this world that she valued as much as her honour,” and that if the king wanted to give her a present, she begged it might be at “such a time as God would be pleased to send her some advantageous marriage”.

Such a calculated reply is reminiscent of Anne during the days of her courtship with Henry. In response to Jane’s coyness, Henry’s love for her was said to have “marvellously increased”. Yet she was described as a lady whom the king “serves” – a telling word implying that he sought her as his ‘courtly love’ mistress. There is little evidence that, before Anne was accused of adultery, Henry had planned to make Jane his wife. Marriage to Jane was, surely, a symptom and a product of Anne’s downfall, not a cause.

The pivotal piece of evidence for a conspiracy is a remark made by Cromwell to Chapuys after Anne’s death. In a letter to Charles V, Chapuys wrote that Cromwell had told him “il se mist a fantasier et conspirer le dict affaire,” which has been translated as “he set himself to devise and conspire the said affair,” suggesting that Cromwell plotted against Anne.

Crucially, however, this phrase is often used out of context. The previous sentence states that “he himself [Cromwell] had been authorised and commissioned by the king to prosecute and bring to an end the mistress’s trial, to do which he had taken considerable trouble.” If we accept this account, it is impossible to dismiss Henry VIII from the picture – Cromwell claimed not to be acting alone.

It has been proposed, therefore, that Henry asked Cromwell to get rid of Anne. David Starkey suggested that “Anne’s proud and abrasive character soon became intolerable to her husband”. JJ Scarisbrick, author of the authoritative volume Henry VIII, agreed: “What had once been devastating infatuation turned into bloodthirsty loathing, for reasons we will never completely know.”

Lovers’ quarrelsEvidence for this view is taken from the writings of the ever-hopeful Chapuys. As a Catholic and a supporter of Catherine of Aragon, he referred to Anne as “the concubine” or “the she-devil”, and had made bitter assertions about the doomed state of Henry and Anne’s relationship even at the height of their happiness in late summer 1533. But Chapuys himself recognised that Henry and Anne had always been prone to “lovers’ quarrels”, and that the king’s character was very “changeable”.

True, Henry and Anne were direct with each other: they got angry, shouted and became jealous. But they were also frequently described as being “merry” together; it was an epithet still being applied to them during the autumn of 1535 – and one that was appended to their marriage more often than to any of Henry’s other unions. Bernard has described theirs as a “tumultuous relationship of sunshine and storms”.

Some have proposed that the miscarriage of a male foetus suffered by Anne in January 1536 led inexorably to her downfall. Did it cause Henry to believe that Anne would never be able to bear him an heir, and thus to consider the marriage doomed? Certainly, the king was reported to have shown “great disappointment and sorrow”. Chapuys wrote that Henry, during his visit to Anne’s chamber after the tragedy, said very little except: “I see that God will not give me male children.”

Henry then left Anne at Greenwich to convalesce while he went to Whitehall to mark the feast day of St Matthew. Chapuys, rather maliciously, interpreted this as showing that Henry had abandoned Anne, “whereas in former times he could hardly be one hour without her”. Clearly, the miscarriage was a great blow to both Henry and Anne – yet another four months were to pass before Anne’s death, so demonstrating a direct link between the events would be problematic.

Another story, reported third-hand by Chapuys, quotes Henry as telling an unidentified courtier that he had married Anne “seduced and constrained by sortilèges”. That last word translates as ‘sorcery, spells, charms’, and has given rise to the suggestion that Anne Boleyn dabbled in witchcraft. Though this is regularly cited as one of the charges of which she was found guilty, it is not mentioned in the indictment.