MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 101

May 13, 2016

History Trivia - Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia) excommunicates Girolamo Savonarola

May 13

1497 Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia) excommunicated Girolamo Savonarola (Italian Dominican friar and an influential contributor to the politics of Florence. He vehemently preached against the moral corruption of much of the clergy at the time, and his main opponent was Rodrigo Borgia).

1497 Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia) excommunicated Girolamo Savonarola (Italian Dominican friar and an influential contributor to the politics of Florence. He vehemently preached against the moral corruption of much of the clergy at the time, and his main opponent was Rodrigo Borgia).

Published on May 13, 2016 02:00

May 12, 2016

Second Anglo-Saxon cemetery with fascinating grave goods unearthed near Stonehenge

Ancient Origins

For the second time in one month archaeologists have found an Anglo-Saxon cemetery near the prehistoric Stonehenge monument on the Salisbury Plain in England. The cemetery is about 1,300 years old. Stonehenge is believed to be much older, and researchers have speculated that later people wanted to be buried near the gigantic, ancient wonder.

The Anglo-Saxon cemetery has about 55 skeletons buried in it. Most of the graves contain personal items placed with the bodies upon their burial to accompany them into the afterlife.

Archaeologists have found beads, combs, coins, bone pins and spearheads. Some of the coins were perforated, and it’s believed they were used in necklaces. The most common item in the graves were little iron knives, according to an article about the dig in the Daily Mail.

A decorated bone comb found during the excavation of a grave. (Wessex Archaeology)The researchers have narrowed down the dates of the cemetery to between the late 7th and early 8th century AD. It is near the modern village of Tidworth.

A decorated bone comb found during the excavation of a grave. (Wessex Archaeology)The researchers have narrowed down the dates of the cemetery to between the late 7th and early 8th century AD. It is near the modern village of Tidworth.

The cemetery was discovered when archaeologists did a survey to prepare for a subdivision of homes for military personnel. In England as in many other countries, developers must commission archaeological surveys before construction to determine whether there are significant historic features that must be preserved.

“The earliest documentary evidence we have for Saxon settlement at Tidworth dates to 975 AD,” Simon Flaherty, site director for Wessex Archaeology, told the Daily Mail. “This excavation potentially pushes the history of the town back a further 300 years.”

Just last month (April 2016), archaeologists uncovered the other Anglo-Saxon cemetery in Bulford, Wiltshire. It had about 150 graves and beautiful grave goods.

Archaeologists will have now have an opportunity to compare the burial practices of two neighboring communities whose members likely knew each other, project manager Bruce Eaton told the Daily Mail.

Some of the Tidworth graves contained goods that pointed to their occupants’ occupations or social status. For example, one grave of an apparent warrior contained a man who had stood 1.8 meters (6 feet), who had with him an unusually large spearhead and a conical shield.

Another burial, of a woman, had beads, a bone comb, jewelry, a decorative belt and a fine bronze work box.

A workbox found in the grave of a woman. (Wessex Archaeology)Some of these small cylindrical boxes have been found at other Anglo-Saxon graves in the British Isles and Rhineland, but their use has confounded experts.

A workbox found in the grave of a woman. (Wessex Archaeology)Some of these small cylindrical boxes have been found at other Anglo-Saxon graves in the British Isles and Rhineland, but their use has confounded experts.

The objects have been dubbed variously as work boxes, thread boxes or relic boxes. Some earlier researchers thought they had practical applications, such as for sewing items. A few of the boxes had pins, pieces of fabric or threads in them.

But others have speculated they were used to hold magic spells, drugs or Christian relics, says the Daily Mail. A scan of the small, cylindrical container showed it has traces of copper-alloy fragments.

The graves at Bulworth had burials dating from the mid-Anglo Saxon period of 660 to 780 AD and is also being excavated. Archaeologists also found Bronze Age or Neolithic monuments nearby, though no evidence of houses nearby where the buried people may have lived.

In the April case too archaeologists were called in to investigate the site before homes were built. Wessex Archaeology issued a statement last month that said:

A further phase of excavation is planned to examine the two adjacent prehistoric monuments beside which the Saxon cemetery was established. These appear to consist of Early Bronze Age round barrows that may have earlier, Neolithic origins. They are to be granted scheduled monument protection by Historic England and will be preserved in situ in a part of the site that will remain undeveloped.The people in this cemetery were buried with personal items and grave goods giving indications of their social status, including jewelry of glass beads and brooches, knives, and cowrie shells from the Red Sea, which indicate far-reaching trade. One grave had a large comb made of antlers and decorated with dots, rings and chevrons.

Featured image: Skeleton found near Stonehenge. Credit: Wessex Archaeology

By Mark Miller

For the second time in one month archaeologists have found an Anglo-Saxon cemetery near the prehistoric Stonehenge monument on the Salisbury Plain in England. The cemetery is about 1,300 years old. Stonehenge is believed to be much older, and researchers have speculated that later people wanted to be buried near the gigantic, ancient wonder.

The Anglo-Saxon cemetery has about 55 skeletons buried in it. Most of the graves contain personal items placed with the bodies upon their burial to accompany them into the afterlife.

Archaeologists have found beads, combs, coins, bone pins and spearheads. Some of the coins were perforated, and it’s believed they were used in necklaces. The most common item in the graves were little iron knives, according to an article about the dig in the Daily Mail.

A decorated bone comb found during the excavation of a grave. (Wessex Archaeology)The researchers have narrowed down the dates of the cemetery to between the late 7th and early 8th century AD. It is near the modern village of Tidworth.

A decorated bone comb found during the excavation of a grave. (Wessex Archaeology)The researchers have narrowed down the dates of the cemetery to between the late 7th and early 8th century AD. It is near the modern village of Tidworth.The cemetery was discovered when archaeologists did a survey to prepare for a subdivision of homes for military personnel. In England as in many other countries, developers must commission archaeological surveys before construction to determine whether there are significant historic features that must be preserved.

“The earliest documentary evidence we have for Saxon settlement at Tidworth dates to 975 AD,” Simon Flaherty, site director for Wessex Archaeology, told the Daily Mail. “This excavation potentially pushes the history of the town back a further 300 years.”

Just last month (April 2016), archaeologists uncovered the other Anglo-Saxon cemetery in Bulford, Wiltshire. It had about 150 graves and beautiful grave goods.

Archaeologists will have now have an opportunity to compare the burial practices of two neighboring communities whose members likely knew each other, project manager Bruce Eaton told the Daily Mail.

Some of the Tidworth graves contained goods that pointed to their occupants’ occupations or social status. For example, one grave of an apparent warrior contained a man who had stood 1.8 meters (6 feet), who had with him an unusually large spearhead and a conical shield.

Another burial, of a woman, had beads, a bone comb, jewelry, a decorative belt and a fine bronze work box.

A workbox found in the grave of a woman. (Wessex Archaeology)Some of these small cylindrical boxes have been found at other Anglo-Saxon graves in the British Isles and Rhineland, but their use has confounded experts.

A workbox found in the grave of a woman. (Wessex Archaeology)Some of these small cylindrical boxes have been found at other Anglo-Saxon graves in the British Isles and Rhineland, but their use has confounded experts.The objects have been dubbed variously as work boxes, thread boxes or relic boxes. Some earlier researchers thought they had practical applications, such as for sewing items. A few of the boxes had pins, pieces of fabric or threads in them.

But others have speculated they were used to hold magic spells, drugs or Christian relics, says the Daily Mail. A scan of the small, cylindrical container showed it has traces of copper-alloy fragments.

The graves at Bulworth had burials dating from the mid-Anglo Saxon period of 660 to 780 AD and is also being excavated. Archaeologists also found Bronze Age or Neolithic monuments nearby, though no evidence of houses nearby where the buried people may have lived.

In the April case too archaeologists were called in to investigate the site before homes were built. Wessex Archaeology issued a statement last month that said:

A further phase of excavation is planned to examine the two adjacent prehistoric monuments beside which the Saxon cemetery was established. These appear to consist of Early Bronze Age round barrows that may have earlier, Neolithic origins. They are to be granted scheduled monument protection by Historic England and will be preserved in situ in a part of the site that will remain undeveloped.The people in this cemetery were buried with personal items and grave goods giving indications of their social status, including jewelry of glass beads and brooches, knives, and cowrie shells from the Red Sea, which indicate far-reaching trade. One grave had a large comb made of antlers and decorated with dots, rings and chevrons.

Featured image: Skeleton found near Stonehenge. Credit: Wessex Archaeology

By Mark Miller

Published on May 12, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Richard the Lionhearted marries

Published on May 12, 2016 02:00

May 11, 2016

Moving to medieval England

History Extra

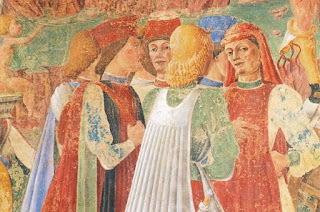

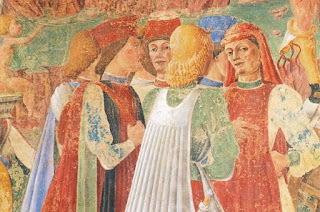

A group of merchants in a c1470 painting. By the mid-15th century, increasing numbers of foreign merchants were setting up home in England’s major cities. (AKG)

A group of merchants in a c1470 painting. By the mid-15th century, increasing numbers of foreign merchants were setting up home in England’s major cities. (AKG)

Reading the name ‘Reginald Newport’ in the English records of the 14th century does not immediately lead one to suppose that its holder was a foreigner. To all intents and purposes, the man in question was a full and active subject of the English crown, a minor functionary in the royal household of Edward III, a property-holder in the city of London and rural Berkshire, and an influential public official as regulator of fisheries along the Thames basin. And yet, when the city of London challenged Reginald’s powers in 1377, it quite deliberately chose to undermine his authority by naming him as “Reginald Newport, Fleming”. Suddenly, we open up a whole new aspect of the life and career of Reynauld Nieuport, as we might now call him. In the middle years of the 14th century, immigrants from Flanders had a particularly high profile in England. They came over, in quite significant numbers, as agricultural labourers, as skilled cloth weavers, and as merchants involved in international trade. By the 1370s, however, they were increasingly seen as abusing their special privileges and enjoying unfair economic advantages over their English-born neighbours and co-workers. Reginald survived the backlash, but the Flemish communities in London and other English towns were to be the butt of particularly violent popular hatred during the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. England, we often observe, is a nation of immigrants. The standard story is that of a sequence of early invasions by the Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings and Normans, followed by the arrival of the Huguenots as refugees from continental Europe during the Reformation, and then the rich mix of ethnicities and cultures brought on by the legacy of empire in the 19th and 20th centuries. An important part of this story concerns migration within the British Isles and the evidence for the movement and interaction of the English, Welsh, Irish and Scots. Much less appreciated are the individual stories of people like Reynauld Nieuport who, in every generation, moved to England from all parts of Europe and further afield. It is only in recent years, with the free movement of people within the European Community, that we have begun to consider the possibility that immigration was a constant reality in pre-modern England. Finding these everyday immigrants is no easy task. The English state had no comprehensive way of regulating immigration in the Middle Ages, and although it often used the labels ‘denizen’ and ‘alien’, it had no standard means of defining these categories. In the 14th century, the crown began to develop a formal process known as denization, by which an immigrant of good standing in his or her community could renounce allegiance to their former ruler and be given all the rights of an English-born subject. Denization became quite big business by the Tudor period, but because of the costs involved, it tended only to be sought by relatively prosperous and influential immigrants: craftsmen, merchants, clergymen, wealthy landholders, and so on. The records therefore miss an important part of the story by omitting the little people who were much more numerous, more widely dispersed, and ultimately often more influential in determining popular attitudes to immigration.

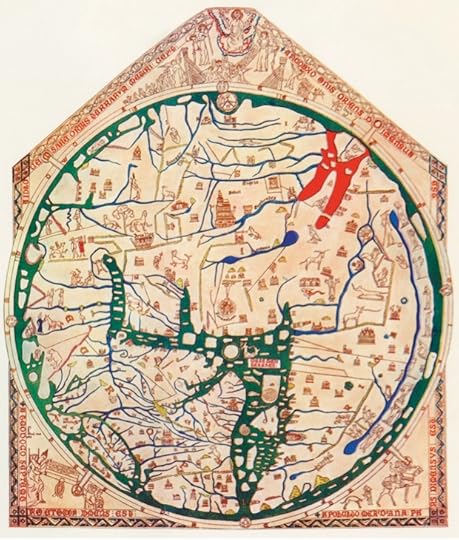

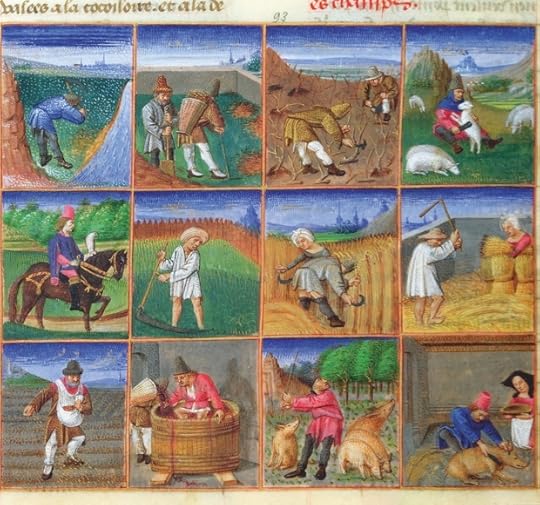

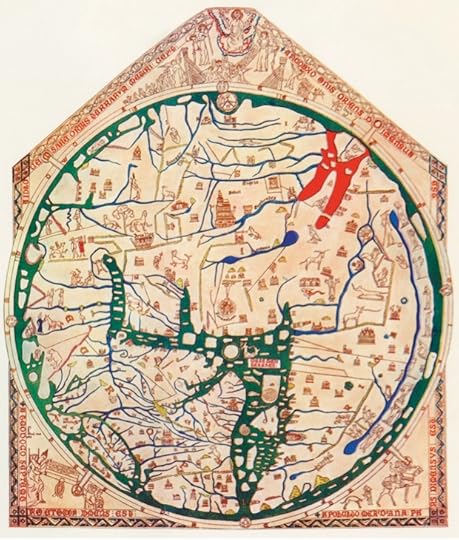

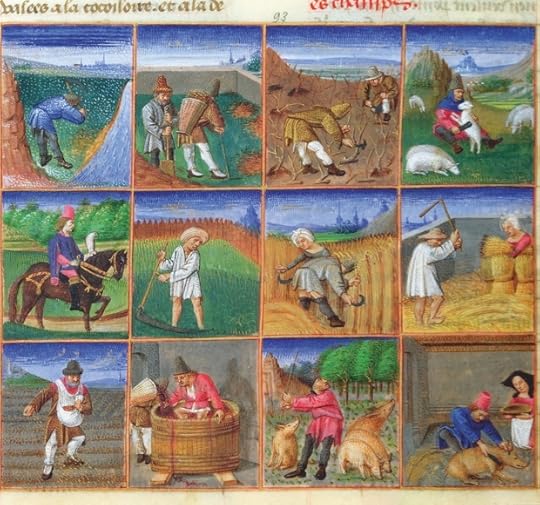

The Hereford Mappa Mundi of c1300, showing Jerusalem in the centre, Europe lower left and Africa lower right. By the late Middle Ages, people from France, the Low Countries, the eastern Mediterranean and north Africa were living and working in England. (AKG) National securityFortunately (for us), in 1440, the English parliament inadvertently shone a light into the gloom by imposing a new tax on resident foreigners. Immigrants had paid taxes before this time – the difference was simply that aliens were now to be a special fiscal category. The motivation was ostensibly about finding new funds for the final, faltering stages of the Hundred Years’ War. In reality, the initiative was just as much about regulation. Taking a census of resident foreigners could be a first step to greater controls at a time when there were significant political misgivings both about aliens’ economic power and about national security. In the end, the wider potential of the census was not exploited. For modern historians, however, it provides an amazingly detailed survey of the geographical distribution, numbers, social status and occupations of foreigners living and working in England in 1440. It also gives us a tantalising glimpse of the human interactions between the native-born and the alien residents of the realm. How were immigrants identified? Certainly not by the scrutiny of anything akin to passports and official papers. Rather, local juries of English-born men were asked to provide lists of all known aliens living in their communities. In some places, such as London, this was done with great thoroughness; in others, like rural Lancashire, it was hardly applied at all. In general, though, the local jurors were quite assiduous. Parliament had taken the view that all those born outside the realm of England should be included, even if, as in the case of Ireland and Gascony, their homeland was under the dominion of the English crown. In Langley Marsh, Buckinghamshire, one of the jurors, Thomas Fisher, was reported as having both an alien servant, named Gelam, and an Irish neighbour – though he could not name the latter. The jurors were not required to give a place of origin for each person named. Sometimes the identity is obvious: “John [the] Frenchman” and “John [the] Scot” are common names in the surviving assessments. At other times, the categories carried rather different connotations from now. At Elmswell in Suffolk, “James [of] Denmark” was firmly labelled “Dutch”, a term that often simply denotes the speaking of some form of northern European language. In other cases, though, the designations are more specific: alongside the generic ‘French’, we get references to people from Picardy, Normandy and Brittany. And there are many references to minor principalities that were then scattered across the Low Countries and Germany. While the largest number of those identified by place of origin in 1440 came from Scotland, Ireland and the areas directly linked to England by sea routes across the Channel and the North Sea, there were also significant numbers of people from Iberia and Italy and a small number from the eastern Mediterranean. Interestingly, the labels used by the jurors and enumerators were linguistic and/or geographical, and ethnicity was not explicitly mentioned. We know from other evidence that there were north Africans and Middle Easterners in England in the Middle Ages, so the fact that the 1440s records are ‘colour-blind’ does not mean that they do not include some members of racial and religious minorities. A husband and wife in London were labelled as coming from “Inde”, which could mean anywhere east of the Holy Land. The fact that their names, Benedict and Antonia, were explicitly Christian suggests that, in most cases, original ethnicity was obscured by identities acceptable to English Catholic culture. The 1440 records also provide a fascinating glimpse of foreigners’ family and household structures. If the dependants of alien householders – wives, adult children, apprentices and servants – had been born abroad, they too were assessed for the tax. Herman Blakke, who came originally from Munster in Westphalia, appears in Huntingdon in 1440 with his wife and a servant, Adrian. And even when the head of the household was English, foreign dependants could still be liable. Sir John Cressy, one of the MPs at the very parliament that granted the new tax on aliens, kept several foreign servants at his residence in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, who had presumably been recruited during Cressy’s career as a soldier in the French wars. There is also much that can be gleaned about the occupations of England’s foreign residents in 1440. In major cities and towns such as London, York, Bristol, Southampton and Norwich, we find high concentrations of foreigners, including prominent merchants from the great trading towns of Flanders and northern Italy. But the foreign influence was not only to be found in metropolitan contexts. At Bildeston in Suffolk there were two Aragonese doctors, perhaps drawn to this corner of East Anglia by the large immigrant workforce in the nearby towns of Lavenham, Sudbury and Hadleigh. The tax records also give us rare glimpses of the influence of foreign artists in England: Henry Phelypp, a Flemish sculptor, was living in the household of John Clopton while carrying out work on the rebuilding of the famous parish church at Long Melford in Suffolk. Across the country we find unskilled labourers from Scotland, Ireland, France and the Low Countries eking out a living in the agricultural economy. Many in this latter category were casual or seasonal workers. In Northumberland, they were actually described as ‘vagabonds’. Here lies one of the reasons why so many people assessed for the tax actually managed to avoid paying it. One of the hallmarks of the resident alien population was its mobility. All in all, the survey of 1440 produced around 20,000 named persons of foreign birth. This number may look tiny in comparison with the record of immigration in later centuries, but we have to remember that the estimated population of England at this time was not greatly in excess of 2 million people. As late as the 1901 census, immigrants counted for about 1 per cent of the total population of the United Kingdom. That there was a comparable level in 1440 allows us to consider later medieval England not as an insular culture but as a genuinely multicultural society. To see things thus is also necessarily to admit the resulting stresses and strains. There is every sign that the taxpayers of 1440 were identified most readily in terms of the languages they spoke and the accents with which they attempted to communicate in English. A story circulated in late medieval England that the rebels of 1381, in seeking out the hated Flemings, had attacked anyone who could not say ‘bread and cheese’ in English. Here is a powerful reminder of the complicated and sometimes perilous existence that foreign-born residents could experience in England. From the 1440s to the 1480s, parliament continued to impose taxes on aliens, and the Tudor regime included the category in the new, comprehensive subsidies developed from the 1520s. In none of these cases, however, did the numbers of persons assessed reach anything approaching the levels of 1440. This was partly a matter of definition: the Irish and the Gascons successfully made their case for immunity after 1440, and the crown offered a series of exemptions to prominent aliens in later taxes. But it was also a sign of the real tension that the tax created, and of the sharper differences that it set up between the native and foreign-born populations. In the longer term, the 1440 tax experiment stands as a serious reminder of the high risks involved when governments attempt to grapple with the question of immigration, and of the trail of administrative failure and political disillusionment that so often results. Pietro de Crescenzi’s calendar shows labourers throughout the year. A 1440 tax on England’s foreign residents suggests that many were employed in casual, seasonal work. (Bridgeman) Meet the ‘aliens’From the Scandinavian academic to the prominent merchant, five foreigners who called England home in the 15th century... The Irish spinner Alice Spynner, an Irish woman living and working in England, was assessed for the tax on resident aliens at Narborough in Leicestershire in 1440. Alice’s occupation is evident from her surname. She was a spinner of wool, a job that was vital to the prosperity of the emergent English cloth industry. Many of Alice’s compatriots made their way into south-western and north-western England, though fewer Irish people are found in the east Midlands. She provides a reminder of the importance of women in England’s late medieval economy; indeed, her own trade made the word ‘spinster’ a synonym for the single, independent woman. The Scottish chaplain William Pulayn was a chaplain working in the rural parish of Sledmere in the East Riding of Yorkshire in 1440, where the local jurors identified him as a Scot. Since Scotland was a separate kingdom, and often at war with England, those born there were consistently treated as aliens by the English state. Chaplains were jobbing priests who made a living by saying masses; other foreign chaplains in the tax records of 1440 included confessors and schoolmasters employed in gentry households. William was among his own kind: Scots were the largest minority group in the north of England. The Swedish student Benedict Nicoll is one of the few people specifically identified in the tax records of 1440 as coming from Sweden. He and five others, including a Magnus and an Olaf, are described as staying with the University of Cambridge. Medieval seats of higher learning were always international in their membership and influence, but those who were full members of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge generally enjoyed exemption from taxation. Whatever Benedict’s status and purpose in Cambridge, he was evidently only a temporary resident, for he had disappeared from the record by the time the second instalment of the 1440 tax was collected. The Dutch artist John Danyell was from Holland, in the modern Netherlands, and appeared in England in 1440 as a painter living in the city of Lincoln. The occupation of painter had the same ambiguity in the 15th century as it does today: it could mean a house-painter, or a maker of fine art. John’s presence in one of the most important cathedral cities of England is a vital clue to the patronage of artists from the Low Countries and of their influence on the northern Renaissance. The Italian trader Alexander Plaustrell, or Palestrelli, was a prominent Italian merchant living in London in the mid-15th century. Originally from Piacenza, he had trading connections across northern Italy, including in Lucca and Genoa. His house was in the Board Street area of London. In 1456, at a moment of high tension, he was physically assaulted in an affray at Cheapside, and the episode set off a series of attacks on Italians across the city. It provides us with one of many examples of the tensions between native Londoners and their international business rivals, as well as showing the readiness with which London mobs could target the foreigners in their midst. Mark Ormrod is professor of medieval history at the University of York, and specialises in the political and cultural history of later medieval England.

Pietro de Crescenzi’s calendar shows labourers throughout the year. A 1440 tax on England’s foreign residents suggests that many were employed in casual, seasonal work. (Bridgeman) Meet the ‘aliens’From the Scandinavian academic to the prominent merchant, five foreigners who called England home in the 15th century... The Irish spinner Alice Spynner, an Irish woman living and working in England, was assessed for the tax on resident aliens at Narborough in Leicestershire in 1440. Alice’s occupation is evident from her surname. She was a spinner of wool, a job that was vital to the prosperity of the emergent English cloth industry. Many of Alice’s compatriots made their way into south-western and north-western England, though fewer Irish people are found in the east Midlands. She provides a reminder of the importance of women in England’s late medieval economy; indeed, her own trade made the word ‘spinster’ a synonym for the single, independent woman. The Scottish chaplain William Pulayn was a chaplain working in the rural parish of Sledmere in the East Riding of Yorkshire in 1440, where the local jurors identified him as a Scot. Since Scotland was a separate kingdom, and often at war with England, those born there were consistently treated as aliens by the English state. Chaplains were jobbing priests who made a living by saying masses; other foreign chaplains in the tax records of 1440 included confessors and schoolmasters employed in gentry households. William was among his own kind: Scots were the largest minority group in the north of England. The Swedish student Benedict Nicoll is one of the few people specifically identified in the tax records of 1440 as coming from Sweden. He and five others, including a Magnus and an Olaf, are described as staying with the University of Cambridge. Medieval seats of higher learning were always international in their membership and influence, but those who were full members of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge generally enjoyed exemption from taxation. Whatever Benedict’s status and purpose in Cambridge, he was evidently only a temporary resident, for he had disappeared from the record by the time the second instalment of the 1440 tax was collected. The Dutch artist John Danyell was from Holland, in the modern Netherlands, and appeared in England in 1440 as a painter living in the city of Lincoln. The occupation of painter had the same ambiguity in the 15th century as it does today: it could mean a house-painter, or a maker of fine art. John’s presence in one of the most important cathedral cities of England is a vital clue to the patronage of artists from the Low Countries and of their influence on the northern Renaissance. The Italian trader Alexander Plaustrell, or Palestrelli, was a prominent Italian merchant living in London in the mid-15th century. Originally from Piacenza, he had trading connections across northern Italy, including in Lucca and Genoa. His house was in the Board Street area of London. In 1456, at a moment of high tension, he was physically assaulted in an affray at Cheapside, and the episode set off a series of attacks on Italians across the city. It provides us with one of many examples of the tensions between native Londoners and their international business rivals, as well as showing the readiness with which London mobs could target the foreigners in their midst. Mark Ormrod is professor of medieval history at the University of York, and specialises in the political and cultural history of later medieval England.

A group of merchants in a c1470 painting. By the mid-15th century, increasing numbers of foreign merchants were setting up home in England’s major cities. (AKG)

A group of merchants in a c1470 painting. By the mid-15th century, increasing numbers of foreign merchants were setting up home in England’s major cities. (AKG) Reading the name ‘Reginald Newport’ in the English records of the 14th century does not immediately lead one to suppose that its holder was a foreigner. To all intents and purposes, the man in question was a full and active subject of the English crown, a minor functionary in the royal household of Edward III, a property-holder in the city of London and rural Berkshire, and an influential public official as regulator of fisheries along the Thames basin. And yet, when the city of London challenged Reginald’s powers in 1377, it quite deliberately chose to undermine his authority by naming him as “Reginald Newport, Fleming”. Suddenly, we open up a whole new aspect of the life and career of Reynauld Nieuport, as we might now call him. In the middle years of the 14th century, immigrants from Flanders had a particularly high profile in England. They came over, in quite significant numbers, as agricultural labourers, as skilled cloth weavers, and as merchants involved in international trade. By the 1370s, however, they were increasingly seen as abusing their special privileges and enjoying unfair economic advantages over their English-born neighbours and co-workers. Reginald survived the backlash, but the Flemish communities in London and other English towns were to be the butt of particularly violent popular hatred during the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. England, we often observe, is a nation of immigrants. The standard story is that of a sequence of early invasions by the Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings and Normans, followed by the arrival of the Huguenots as refugees from continental Europe during the Reformation, and then the rich mix of ethnicities and cultures brought on by the legacy of empire in the 19th and 20th centuries. An important part of this story concerns migration within the British Isles and the evidence for the movement and interaction of the English, Welsh, Irish and Scots. Much less appreciated are the individual stories of people like Reynauld Nieuport who, in every generation, moved to England from all parts of Europe and further afield. It is only in recent years, with the free movement of people within the European Community, that we have begun to consider the possibility that immigration was a constant reality in pre-modern England. Finding these everyday immigrants is no easy task. The English state had no comprehensive way of regulating immigration in the Middle Ages, and although it often used the labels ‘denizen’ and ‘alien’, it had no standard means of defining these categories. In the 14th century, the crown began to develop a formal process known as denization, by which an immigrant of good standing in his or her community could renounce allegiance to their former ruler and be given all the rights of an English-born subject. Denization became quite big business by the Tudor period, but because of the costs involved, it tended only to be sought by relatively prosperous and influential immigrants: craftsmen, merchants, clergymen, wealthy landholders, and so on. The records therefore miss an important part of the story by omitting the little people who were much more numerous, more widely dispersed, and ultimately often more influential in determining popular attitudes to immigration.

The Hereford Mappa Mundi of c1300, showing Jerusalem in the centre, Europe lower left and Africa lower right. By the late Middle Ages, people from France, the Low Countries, the eastern Mediterranean and north Africa were living and working in England. (AKG) National securityFortunately (for us), in 1440, the English parliament inadvertently shone a light into the gloom by imposing a new tax on resident foreigners. Immigrants had paid taxes before this time – the difference was simply that aliens were now to be a special fiscal category. The motivation was ostensibly about finding new funds for the final, faltering stages of the Hundred Years’ War. In reality, the initiative was just as much about regulation. Taking a census of resident foreigners could be a first step to greater controls at a time when there were significant political misgivings both about aliens’ economic power and about national security. In the end, the wider potential of the census was not exploited. For modern historians, however, it provides an amazingly detailed survey of the geographical distribution, numbers, social status and occupations of foreigners living and working in England in 1440. It also gives us a tantalising glimpse of the human interactions between the native-born and the alien residents of the realm. How were immigrants identified? Certainly not by the scrutiny of anything akin to passports and official papers. Rather, local juries of English-born men were asked to provide lists of all known aliens living in their communities. In some places, such as London, this was done with great thoroughness; in others, like rural Lancashire, it was hardly applied at all. In general, though, the local jurors were quite assiduous. Parliament had taken the view that all those born outside the realm of England should be included, even if, as in the case of Ireland and Gascony, their homeland was under the dominion of the English crown. In Langley Marsh, Buckinghamshire, one of the jurors, Thomas Fisher, was reported as having both an alien servant, named Gelam, and an Irish neighbour – though he could not name the latter. The jurors were not required to give a place of origin for each person named. Sometimes the identity is obvious: “John [the] Frenchman” and “John [the] Scot” are common names in the surviving assessments. At other times, the categories carried rather different connotations from now. At Elmswell in Suffolk, “James [of] Denmark” was firmly labelled “Dutch”, a term that often simply denotes the speaking of some form of northern European language. In other cases, though, the designations are more specific: alongside the generic ‘French’, we get references to people from Picardy, Normandy and Brittany. And there are many references to minor principalities that were then scattered across the Low Countries and Germany. While the largest number of those identified by place of origin in 1440 came from Scotland, Ireland and the areas directly linked to England by sea routes across the Channel and the North Sea, there were also significant numbers of people from Iberia and Italy and a small number from the eastern Mediterranean. Interestingly, the labels used by the jurors and enumerators were linguistic and/or geographical, and ethnicity was not explicitly mentioned. We know from other evidence that there were north Africans and Middle Easterners in England in the Middle Ages, so the fact that the 1440s records are ‘colour-blind’ does not mean that they do not include some members of racial and religious minorities. A husband and wife in London were labelled as coming from “Inde”, which could mean anywhere east of the Holy Land. The fact that their names, Benedict and Antonia, were explicitly Christian suggests that, in most cases, original ethnicity was obscured by identities acceptable to English Catholic culture. The 1440 records also provide a fascinating glimpse of foreigners’ family and household structures. If the dependants of alien householders – wives, adult children, apprentices and servants – had been born abroad, they too were assessed for the tax. Herman Blakke, who came originally from Munster in Westphalia, appears in Huntingdon in 1440 with his wife and a servant, Adrian. And even when the head of the household was English, foreign dependants could still be liable. Sir John Cressy, one of the MPs at the very parliament that granted the new tax on aliens, kept several foreign servants at his residence in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, who had presumably been recruited during Cressy’s career as a soldier in the French wars. There is also much that can be gleaned about the occupations of England’s foreign residents in 1440. In major cities and towns such as London, York, Bristol, Southampton and Norwich, we find high concentrations of foreigners, including prominent merchants from the great trading towns of Flanders and northern Italy. But the foreign influence was not only to be found in metropolitan contexts. At Bildeston in Suffolk there were two Aragonese doctors, perhaps drawn to this corner of East Anglia by the large immigrant workforce in the nearby towns of Lavenham, Sudbury and Hadleigh. The tax records also give us rare glimpses of the influence of foreign artists in England: Henry Phelypp, a Flemish sculptor, was living in the household of John Clopton while carrying out work on the rebuilding of the famous parish church at Long Melford in Suffolk. Across the country we find unskilled labourers from Scotland, Ireland, France and the Low Countries eking out a living in the agricultural economy. Many in this latter category were casual or seasonal workers. In Northumberland, they were actually described as ‘vagabonds’. Here lies one of the reasons why so many people assessed for the tax actually managed to avoid paying it. One of the hallmarks of the resident alien population was its mobility. All in all, the survey of 1440 produced around 20,000 named persons of foreign birth. This number may look tiny in comparison with the record of immigration in later centuries, but we have to remember that the estimated population of England at this time was not greatly in excess of 2 million people. As late as the 1901 census, immigrants counted for about 1 per cent of the total population of the United Kingdom. That there was a comparable level in 1440 allows us to consider later medieval England not as an insular culture but as a genuinely multicultural society. To see things thus is also necessarily to admit the resulting stresses and strains. There is every sign that the taxpayers of 1440 were identified most readily in terms of the languages they spoke and the accents with which they attempted to communicate in English. A story circulated in late medieval England that the rebels of 1381, in seeking out the hated Flemings, had attacked anyone who could not say ‘bread and cheese’ in English. Here is a powerful reminder of the complicated and sometimes perilous existence that foreign-born residents could experience in England. From the 1440s to the 1480s, parliament continued to impose taxes on aliens, and the Tudor regime included the category in the new, comprehensive subsidies developed from the 1520s. In none of these cases, however, did the numbers of persons assessed reach anything approaching the levels of 1440. This was partly a matter of definition: the Irish and the Gascons successfully made their case for immunity after 1440, and the crown offered a series of exemptions to prominent aliens in later taxes. But it was also a sign of the real tension that the tax created, and of the sharper differences that it set up between the native and foreign-born populations. In the longer term, the 1440 tax experiment stands as a serious reminder of the high risks involved when governments attempt to grapple with the question of immigration, and of the trail of administrative failure and political disillusionment that so often results.

Pietro de Crescenzi’s calendar shows labourers throughout the year. A 1440 tax on England’s foreign residents suggests that many were employed in casual, seasonal work. (Bridgeman) Meet the ‘aliens’From the Scandinavian academic to the prominent merchant, five foreigners who called England home in the 15th century... The Irish spinner Alice Spynner, an Irish woman living and working in England, was assessed for the tax on resident aliens at Narborough in Leicestershire in 1440. Alice’s occupation is evident from her surname. She was a spinner of wool, a job that was vital to the prosperity of the emergent English cloth industry. Many of Alice’s compatriots made their way into south-western and north-western England, though fewer Irish people are found in the east Midlands. She provides a reminder of the importance of women in England’s late medieval economy; indeed, her own trade made the word ‘spinster’ a synonym for the single, independent woman. The Scottish chaplain William Pulayn was a chaplain working in the rural parish of Sledmere in the East Riding of Yorkshire in 1440, where the local jurors identified him as a Scot. Since Scotland was a separate kingdom, and often at war with England, those born there were consistently treated as aliens by the English state. Chaplains were jobbing priests who made a living by saying masses; other foreign chaplains in the tax records of 1440 included confessors and schoolmasters employed in gentry households. William was among his own kind: Scots were the largest minority group in the north of England. The Swedish student Benedict Nicoll is one of the few people specifically identified in the tax records of 1440 as coming from Sweden. He and five others, including a Magnus and an Olaf, are described as staying with the University of Cambridge. Medieval seats of higher learning were always international in their membership and influence, but those who were full members of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge generally enjoyed exemption from taxation. Whatever Benedict’s status and purpose in Cambridge, he was evidently only a temporary resident, for he had disappeared from the record by the time the second instalment of the 1440 tax was collected. The Dutch artist John Danyell was from Holland, in the modern Netherlands, and appeared in England in 1440 as a painter living in the city of Lincoln. The occupation of painter had the same ambiguity in the 15th century as it does today: it could mean a house-painter, or a maker of fine art. John’s presence in one of the most important cathedral cities of England is a vital clue to the patronage of artists from the Low Countries and of their influence on the northern Renaissance. The Italian trader Alexander Plaustrell, or Palestrelli, was a prominent Italian merchant living in London in the mid-15th century. Originally from Piacenza, he had trading connections across northern Italy, including in Lucca and Genoa. His house was in the Board Street area of London. In 1456, at a moment of high tension, he was physically assaulted in an affray at Cheapside, and the episode set off a series of attacks on Italians across the city. It provides us with one of many examples of the tensions between native Londoners and their international business rivals, as well as showing the readiness with which London mobs could target the foreigners in their midst. Mark Ormrod is professor of medieval history at the University of York, and specialises in the political and cultural history of later medieval England.

Pietro de Crescenzi’s calendar shows labourers throughout the year. A 1440 tax on England’s foreign residents suggests that many were employed in casual, seasonal work. (Bridgeman) Meet the ‘aliens’From the Scandinavian academic to the prominent merchant, five foreigners who called England home in the 15th century... The Irish spinner Alice Spynner, an Irish woman living and working in England, was assessed for the tax on resident aliens at Narborough in Leicestershire in 1440. Alice’s occupation is evident from her surname. She was a spinner of wool, a job that was vital to the prosperity of the emergent English cloth industry. Many of Alice’s compatriots made their way into south-western and north-western England, though fewer Irish people are found in the east Midlands. She provides a reminder of the importance of women in England’s late medieval economy; indeed, her own trade made the word ‘spinster’ a synonym for the single, independent woman. The Scottish chaplain William Pulayn was a chaplain working in the rural parish of Sledmere in the East Riding of Yorkshire in 1440, where the local jurors identified him as a Scot. Since Scotland was a separate kingdom, and often at war with England, those born there were consistently treated as aliens by the English state. Chaplains were jobbing priests who made a living by saying masses; other foreign chaplains in the tax records of 1440 included confessors and schoolmasters employed in gentry households. William was among his own kind: Scots were the largest minority group in the north of England. The Swedish student Benedict Nicoll is one of the few people specifically identified in the tax records of 1440 as coming from Sweden. He and five others, including a Magnus and an Olaf, are described as staying with the University of Cambridge. Medieval seats of higher learning were always international in their membership and influence, but those who were full members of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge generally enjoyed exemption from taxation. Whatever Benedict’s status and purpose in Cambridge, he was evidently only a temporary resident, for he had disappeared from the record by the time the second instalment of the 1440 tax was collected. The Dutch artist John Danyell was from Holland, in the modern Netherlands, and appeared in England in 1440 as a painter living in the city of Lincoln. The occupation of painter had the same ambiguity in the 15th century as it does today: it could mean a house-painter, or a maker of fine art. John’s presence in one of the most important cathedral cities of England is a vital clue to the patronage of artists from the Low Countries and of their influence on the northern Renaissance. The Italian trader Alexander Plaustrell, or Palestrelli, was a prominent Italian merchant living in London in the mid-15th century. Originally from Piacenza, he had trading connections across northern Italy, including in Lucca and Genoa. His house was in the Board Street area of London. In 1456, at a moment of high tension, he was physically assaulted in an affray at Cheapside, and the episode set off a series of attacks on Italians across the city. It provides us with one of many examples of the tensions between native Londoners and their international business rivals, as well as showing the readiness with which London mobs could target the foreigners in their midst. Mark Ormrod is professor of medieval history at the University of York, and specialises in the political and cultural history of later medieval England.

Published on May 11, 2016 03:00

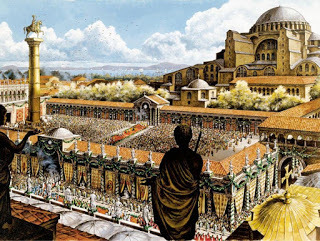

History Trivia - Constantinople dedicated new capital of Roman Empire

May 11

330 Constantinople was dedicated as the new capital of the Roman Empire during the reign of Constantine the Great

330 Constantinople was dedicated as the new capital of the Roman Empire during the reign of Constantine the Great

Published on May 11, 2016 02:00

May 10, 2016

Leaving a Mark: Elaborate Tattoos Found on 3,000-Year-Old Egyptian Mummy

Ancient Origins

A bioarchaeologist studying mummies found in Deir el-Medina, Egypt has discovered a special kind of ancient tattoo. While most Egyptian mummies with tattoos only have patterns of dots and dashes, those present on the remains of a woman from 3,000 years ago are said to be the first example of a mummy from dynastic Egypt to depict actual objects.

The study comes from Anne Austin of Stanford University who presented her findings last month at a meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. By using infrared lighting and an infrared sensor, Austin found that the mummy has over 30 tattoos – although many of them are not visible to the naked eye.

As the mummy's skin is distorted and covered in resin, it is difficult to see many of the tattoos, such as these Hathor cows, with the naked eye. (

Anne Austin

)And speaking of eyes, one of the symbols found on the woman are wadjet eyes, which an article in the journal Nature says are “possible symbols of protection against evil that adorn the mummy’s neck, shoulders and back.” As Austin told Nature, “Any angle that you look at this woman, you see a pair of divine eyes looking back at you.”

As the mummy's skin is distorted and covered in resin, it is difficult to see many of the tattoos, such as these Hathor cows, with the naked eye. (

Anne Austin

)And speaking of eyes, one of the symbols found on the woman are wadjet eyes, which an article in the journal Nature says are “possible symbols of protection against evil that adorn the mummy’s neck, shoulders and back.” As Austin told Nature, “Any angle that you look at this woman, you see a pair of divine eyes looking back at you.” A blue faience Wadjet amulet with the sacred eye outlined in black. (Harrogate Museums and Arts service/

CC BY SA 4.0

)Along with the wadjet eyes, Austin also found baboons on the mummy’s neck, cows on her arm, and lotus blossoms on her hips. Austin explained that the size and location of the designs (many not within her own reach), show that they held a special significance. She also said that the tattooing “would’ve been very time consuming, and in some areas of the body, extremely painful.” She added that the fact that the woman received such a quantity also demonstrates “not only her belief in their importance, but others around her as well”.

A blue faience Wadjet amulet with the sacred eye outlined in black. (Harrogate Museums and Arts service/

CC BY SA 4.0

)Along with the wadjet eyes, Austin also found baboons on the mummy’s neck, cows on her arm, and lotus blossoms on her hips. Austin explained that the size and location of the designs (many not within her own reach), show that they held a special significance. She also said that the tattooing “would’ve been very time consuming, and in some areas of the body, extremely painful.” She added that the fact that the woman received such a quantity also demonstrates “not only her belief in their importance, but others around her as well”.The Tattooed Priestesses of HathorAncient Ink: How Tattoos Can Reveal Hidden Stories of Past CulturesScientists discover new tattoos on 5,300-year-old Otzi the Iceman mummySpecifically, the tattoos are thought to have a strong religious meaning. For example, the cows are associated with the goddess Hathor. According to Nature, “The symbols on the throat and arms may have been intended to give the woman a jolt of magical power as she sang or played music during rituals for Hathor.”

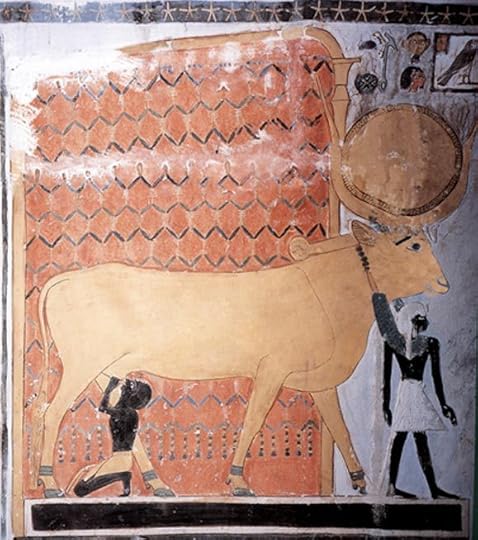

Hathor as a cow suckling a pharaoh. (

CC BY NC SA 2.0

)In the late 19th century several other tattooed female mummies related to Hathor were discovered in Deir el-Bahari, the site of royal and high status burials. The women have been called ‘The Tattooed Priestesses of Hathor’ and the most famous is Amunet, Priestess of the Goddess Hathor. The women have tattoos comprised of dots and dashes and it has been suggested that the markings were likely therapeutic in nature.

Hathor as a cow suckling a pharaoh. (

CC BY NC SA 2.0

)In the late 19th century several other tattooed female mummies related to Hathor were discovered in Deir el-Bahari, the site of royal and high status burials. The women have been called ‘The Tattooed Priestesses of Hathor’ and the most famous is Amunet, Priestess of the Goddess Hathor. The women have tattoos comprised of dots and dashes and it has been suggested that the markings were likely therapeutic in nature.In comparison, Emily teeter, an Egyptologist at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute in Illinois, told Nature that she believes the tattoos on the mummy from Deir el-Medina could be a sign of the woman’s religious nature. As some of the marks are more faded than others, Austin agreed that that the woman’s religious status may have grown with age.

Teeter also revealed that the discovery left her and some other Egyptologists “dumbfounded”. She said, “We didn’t know about this sort of expression before.” While rare, the tattooed woman is not one of a kind, however, and Nature reports that Austin “has already found three more tattooed mummies at Deir el-Medina, and hopes that modern techniques will uncover more elsewhere.”

Anthropologist Ghada Darwish Al-Khafif uses infrared imaging to examine tattoos on the mummy's back. (

Anne Austin

)Featured Image: The mummy's tattoos include two seated baboons depicted between a wadjet eye (top row), a symbol of protection. Source:

Anne Austin

Anthropologist Ghada Darwish Al-Khafif uses infrared imaging to examine tattoos on the mummy's back. (

Anne Austin

)Featured Image: The mummy's tattoos include two seated baboons depicted between a wadjet eye (top row), a symbol of protection. Source:

Anne Austin

By Alicia McDermott

Published on May 10, 2016 03:00

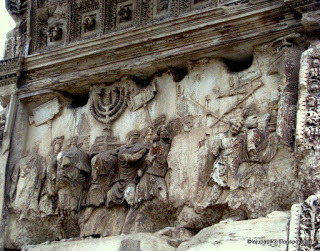

History Trivia - Siege of Jerusalem

May 10

70 Siege of Jerusalem: Titus, son of Emperor Vespasian, opened a full-scale assault on Jerusalem and attacked the city's Third Wall to the northwest.

70 Siege of Jerusalem: Titus, son of Emperor Vespasian, opened a full-scale assault on Jerusalem and attacked the city's Third Wall to the northwest.

Published on May 10, 2016 02:00

May 9, 2016

Archaeologists Say They Have Found an Important Medieval Site Linked to Scottish Hero William Wallace

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists think they’ve confirmed the site where William Wallace was dubbed Guardian of Scotland but are restricted from excavating more because of so many graves in the churchyard.

The site, Auld Kirk in Selkirk, is the same place where tradition says the national hero Wallace, who led a famous rebellion against England, was confirmed as guardian by priests and the nobility in 1297 AD, says an article in The National. Kirk is an old word for church.

A geophysical analysis of the ruins of Auld Kirk revealed an even older church underneath the current structure, possibly a medieval building that archaeologists say strengthens the claim that it was the Kirk o’ the Forest. In that church, officials held the ceremony appointing Wallace and Sir Andrew Moray to the joint guardianship of the country.

It wasn’t long after that Moray died and Wallace was the sole guardian, but he served in that capacity only until the following year, when the English defeated his forces in 1298 at Falkirk.

Scota: Mother of Scotland and Daughter of a Pharaoh Mysterious Underground Labyrinth in Scotland May Have Originally Been a Druid Temple But Wallace continued to serve the Scottish people, including was a warrior.

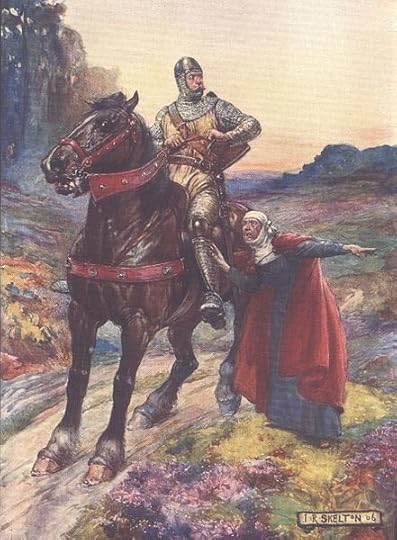

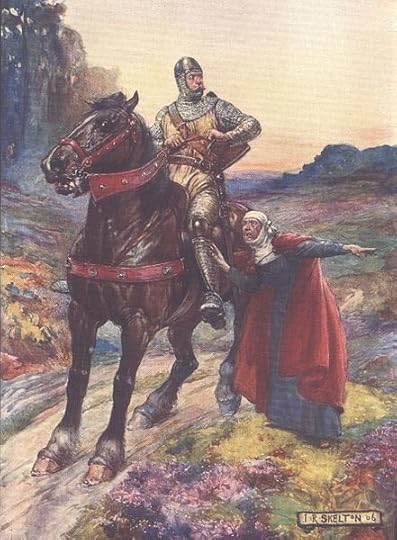

A 1906 depiction of William Wallace in H.E. Marshall’s ‘Scotland's Story.’ (

Public Domain

)In 1299, Wallace went on a diplomatic mission to the French, trying to get them to help in the war against England. French King Phillip the Fair recommended Wallace to Pope Boniface VII, who had been handed John Balliol, a claimant to the Scottish throne. Wallace had hoped to have Balliol restored, but it didn’t happen, though Balliol was allowed to go into exile in France.

A 1906 depiction of William Wallace in H.E. Marshall’s ‘Scotland's Story.’ (

Public Domain

)In 1299, Wallace went on a diplomatic mission to the French, trying to get them to help in the war against England. French King Phillip the Fair recommended Wallace to Pope Boniface VII, who had been handed John Balliol, a claimant to the Scottish throne. Wallace had hoped to have Balliol restored, but it didn’t happen, though Balliol was allowed to go into exile in France.

Wallace returned to Scotland, and historians believe he fought at the 1303 Battle of Rosslyn, in which the Scots defeated three English armies in one day.

On August 3, 1305, the English captured Wallace in Robroyston. He was taken to Carlisle and then paraded to London on foot and in shackles.

Wallace faced trial on August 23 in Westminster Hall, where he was charged with murder and treason. He denied the treason, saying he hadn’t sworn fealty to Edward. It’s said the guilty verdict and his punishment—hanging, drawing, and quartering—were decided beforehand. This was to be a traitor’s death.

‘The Trial of William Wallace at Westminster’ (pre-1870) by Daniel Maclise. (

Public Domain

)“William Wallace was strapped to a wooden hurdle. He was dragged though the streets to the Elms at Smithfield. There he was hanged from a gallows but cut down while he still lived. He was disemboweled before his head was hacked off and his body was cut into pieces,” says an article on the site Scotland History .

‘The Trial of William Wallace at Westminster’ (pre-1870) by Daniel Maclise. (

Public Domain

)“William Wallace was strapped to a wooden hurdle. He was dragged though the streets to the Elms at Smithfield. There he was hanged from a gallows but cut down while he still lived. He was disemboweled before his head was hacked off and his body was cut into pieces,” says an article on the site Scotland History .

Wallace’s place in the history of Scotland is second to none. A biography at ElectricScotland.com says:

16th-century illustration of King Edward I presiding over Parliament. The scene depicts Alexander III of Scotland and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Wales beside Edward; an episode that never actually occurred. (

Public Domain

)Archaeologists working at the Auld Kirk had originally been hoping to find a 16th century church, but they found one from medieval or Norman times instead, The National reports.

16th-century illustration of King Edward I presiding over Parliament. The scene depicts Alexander III of Scotland and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Wales beside Edward; an episode that never actually occurred. (

Public Domain

)Archaeologists working at the Auld Kirk had originally been hoping to find a 16th century church, but they found one from medieval or Norman times instead, The National reports.

The Curious Disappearance of the Eilean Mor Lighthouse Keepers – A Scottish Mystery New Language Dating Back to Iron Age Discovered in Scotland Chris Bowles, the Scottish Borders Council’s archaeologist, commissioned the University of Durham’s geophysical survey along with Selkirk Conversation Regeneration Scheme.

“Ruins of the Auld Kirk date from the 18th century, but we knew this had replaced earlier churches on the site from the 12th and 16th centuries,” Dr. Bowles said , adding:

Dr. Chris Bowles (left) and Colin Gilmour, the Selkirk Conservation Area Regeneration Scheme Project Manager, at Auld Kirk. (

Scottish Borders Council

)Wallace was one of many guardians of Scotland during his era. There were 20 or 21 guardians in total, but Wallace holds the distinction of serving as sole guardian.

Dr. Chris Bowles (left) and Colin Gilmour, the Selkirk Conservation Area Regeneration Scheme Project Manager, at Auld Kirk. (

Scottish Borders Council

)Wallace was one of many guardians of Scotland during his era. There were 20 or 21 guardians in total, but Wallace holds the distinction of serving as sole guardian.

William Wallace gained worldwide fame in the 1995 movie Braveheart, directed by and starring Mel Gibson.

Featured Image: Selkirk’s Auld Kirk, where archaeologists say that William Wallace was declared Guardian of Scotland in 1297. Source: Scottish Borders Council

By Mark Miller

Archaeologists think they’ve confirmed the site where William Wallace was dubbed Guardian of Scotland but are restricted from excavating more because of so many graves in the churchyard.

The site, Auld Kirk in Selkirk, is the same place where tradition says the national hero Wallace, who led a famous rebellion against England, was confirmed as guardian by priests and the nobility in 1297 AD, says an article in The National. Kirk is an old word for church.

A geophysical analysis of the ruins of Auld Kirk revealed an even older church underneath the current structure, possibly a medieval building that archaeologists say strengthens the claim that it was the Kirk o’ the Forest. In that church, officials held the ceremony appointing Wallace and Sir Andrew Moray to the joint guardianship of the country.

It wasn’t long after that Moray died and Wallace was the sole guardian, but he served in that capacity only until the following year, when the English defeated his forces in 1298 at Falkirk.

Scota: Mother of Scotland and Daughter of a Pharaoh Mysterious Underground Labyrinth in Scotland May Have Originally Been a Druid Temple But Wallace continued to serve the Scottish people, including was a warrior.

A 1906 depiction of William Wallace in H.E. Marshall’s ‘Scotland's Story.’ (

Public Domain

)In 1299, Wallace went on a diplomatic mission to the French, trying to get them to help in the war against England. French King Phillip the Fair recommended Wallace to Pope Boniface VII, who had been handed John Balliol, a claimant to the Scottish throne. Wallace had hoped to have Balliol restored, but it didn’t happen, though Balliol was allowed to go into exile in France.

A 1906 depiction of William Wallace in H.E. Marshall’s ‘Scotland's Story.’ (

Public Domain

)In 1299, Wallace went on a diplomatic mission to the French, trying to get them to help in the war against England. French King Phillip the Fair recommended Wallace to Pope Boniface VII, who had been handed John Balliol, a claimant to the Scottish throne. Wallace had hoped to have Balliol restored, but it didn’t happen, though Balliol was allowed to go into exile in France. Wallace returned to Scotland, and historians believe he fought at the 1303 Battle of Rosslyn, in which the Scots defeated three English armies in one day.

On August 3, 1305, the English captured Wallace in Robroyston. He was taken to Carlisle and then paraded to London on foot and in shackles.

Wallace faced trial on August 23 in Westminster Hall, where he was charged with murder and treason. He denied the treason, saying he hadn’t sworn fealty to Edward. It’s said the guilty verdict and his punishment—hanging, drawing, and quartering—were decided beforehand. This was to be a traitor’s death.

‘The Trial of William Wallace at Westminster’ (pre-1870) by Daniel Maclise. (

Public Domain

)“William Wallace was strapped to a wooden hurdle. He was dragged though the streets to the Elms at Smithfield. There he was hanged from a gallows but cut down while he still lived. He was disemboweled before his head was hacked off and his body was cut into pieces,” says an article on the site Scotland History .

‘The Trial of William Wallace at Westminster’ (pre-1870) by Daniel Maclise. (

Public Domain

)“William Wallace was strapped to a wooden hurdle. He was dragged though the streets to the Elms at Smithfield. There he was hanged from a gallows but cut down while he still lived. He was disemboweled before his head was hacked off and his body was cut into pieces,” says an article on the site Scotland History .Wallace’s place in the history of Scotland is second to none. A biography at ElectricScotland.com says:

“William Wallace is one of Scotland's greatest national heroes, undisputed leader of the Scottish resistance forces during the first years of the long and ultimately successful struggle to free Scotland from English rule at the end of the 13th Century.”English King Edward Longshanks wanted the Scottish crown for himself.

16th-century illustration of King Edward I presiding over Parliament. The scene depicts Alexander III of Scotland and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Wales beside Edward; an episode that never actually occurred. (

Public Domain

)Archaeologists working at the Auld Kirk had originally been hoping to find a 16th century church, but they found one from medieval or Norman times instead, The National reports.

16th-century illustration of King Edward I presiding over Parliament. The scene depicts Alexander III of Scotland and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Wales beside Edward; an episode that never actually occurred. (

Public Domain

)Archaeologists working at the Auld Kirk had originally been hoping to find a 16th century church, but they found one from medieval or Norman times instead, The National reports. The Curious Disappearance of the Eilean Mor Lighthouse Keepers – A Scottish Mystery New Language Dating Back to Iron Age Discovered in Scotland Chris Bowles, the Scottish Borders Council’s archaeologist, commissioned the University of Durham’s geophysical survey along with Selkirk Conversation Regeneration Scheme.

“Ruins of the Auld Kirk date from the 18th century, but we knew this had replaced earlier churches on the site from the 12th and 16th centuries,” Dr. Bowles said , adding:

“We had been expecting the geophysics survey to uncover a 16th-century church that we know to have existed and which was a replacement to the medieval church, but the only evidence in the survey is in relation to the medieval church. The association between Wallace and the local area is quite well documented, with Wallace using guerilla tactics to fight the English from the Ettrick Forest. The Scottish nobles made Wallace Guardian of Scotland in recognition of his military successes.”Bowles also noted that there is a lack of information at the site, but hopes that this may change in the future: “There has been little archaeological work carried out to date. We are very restricted by the burials in the area to allow any excavation. But in the future it may be possible to conduct limited investigations in areas where there is no evidence of burial.”

Dr. Chris Bowles (left) and Colin Gilmour, the Selkirk Conservation Area Regeneration Scheme Project Manager, at Auld Kirk. (

Scottish Borders Council

)Wallace was one of many guardians of Scotland during his era. There were 20 or 21 guardians in total, but Wallace holds the distinction of serving as sole guardian.

Dr. Chris Bowles (left) and Colin Gilmour, the Selkirk Conservation Area Regeneration Scheme Project Manager, at Auld Kirk. (

Scottish Borders Council

)Wallace was one of many guardians of Scotland during his era. There were 20 or 21 guardians in total, but Wallace holds the distinction of serving as sole guardian.William Wallace gained worldwide fame in the 1995 movie Braveheart, directed by and starring Mel Gibson.

Featured Image: Selkirk’s Auld Kirk, where archaeologists say that William Wallace was declared Guardian of Scotland in 1297. Source: Scottish Borders Council

By Mark Miller

Published on May 09, 2016 03:00

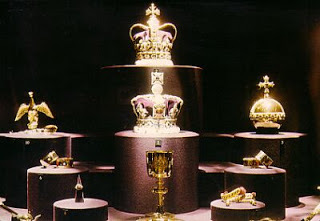

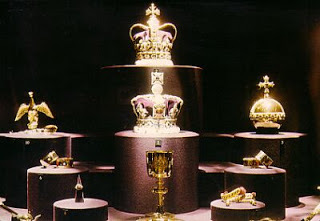

History Trivia - Crown jewels stolen from Tower of London

May 9

1671 The crown jewels were briefly stolen from the Tower of London by Irish adventurer Colonel Thomas Blood.

1671 The crown jewels were briefly stolen from the Tower of London by Irish adventurer Colonel Thomas Blood.

Published on May 09, 2016 02:00

May 8, 2016

Where history happened: the Wars of the Roses

History Extra

Bamburgh Castle. © Darren Turner | Dreamstime.com

Bamburgh Castle. © Darren Turner | Dreamstime.com

During the second half of the 15th century, the people of England witnessed three regional revolts, 13 full-scale battles, ten coups d’etats, 15 invasions, five usurpations, five kings, seven reigns, and five changes of dynasty. Little wonder then that the Wars of the Roses – the name given to the exceptional period of instability that occurred between 1450 and 1500 – have long been regarded as one of the most compelling and, above all, confusing, periods of British history.

If there’s two facts that people know about the Wars of the Roses, it is that they pitched the Red Rose of the House of Lancaster against the White Rose of the House of York – and that they dragged on for a very long time, taking almost a century to peter out.

Fewer people will be aware that the conflict was sparked by a cataclysmic train of events in 1450 that saw England blighted by a massive slump, a government quite without credit, defeat abroad, a parliamentary revolt and a popular rebellion. It was an inability to resolve these issues over the following ten years that brought the Yorkists and Lancastrians to blows.

The Wars of the Roses are best conceived as three individual conflicts. The First War, from 1459–61, witnessed the Yorkist Edward IV (1461–83) overthrowing the Lancastrian Henry VI (1422–61). The Second War, from 1469–71, led to the restoration of Henry VI in 1470, but ended with Edward IV back on the throne in 1471.

The Third War, from 1483 until at least 1487, saw Edward IV’s son Edward V (1483) deposed by the new king’s uncle, Richard III (1483–5), who was himself defeated at Bosworth in 1485 by the first Tudor king, Henry VII (1485–1509). Enemies of the new Tudor dynasty continued to scheme until 1525 – though, in the eyes of the paranoic Henry VIII (1509–47), the threat remained until 1541.

The three principal wars consisted of lightning campaigns that were resolved quickly on the field of battle. Each of these battles bears a name, and we know roughly where they happened. Modern archaeological surveys have revealed scatterings of artefacts on the fields of Towton and Bosworth, but nothing much to see. There were very few sieges: London was threatened three times and the Tower of London taken twice. For long periods, 1461–69, 1471–83, and after 1485, most of the kingdom – all the south, Midlands, East Anglia and West Country – was at peace.

So how did the wars start? The clash between Henry VI and Richard Duke of York at Ludford Bridge in 1459 is sometimes cited as their opening act. Richard had long opposed the king but was routed at Ludford and died in 1460. However, his allies soon declared Henry – who had suffered mental illness – unfit to rule. In 1461 they replaced him with York’s son, Edward IV, and confined Henry to the Tower.

At first, Edward ruled through his elder cousin, Warwick (the Kingmaker), and then through a series of favourites. Prominent among them was William Herbert, the new ruler of Wales, whose power was soon seen as a threat to Warwick. In fact, it was largely to destroy Herbert that Warwick and Edward’s brother, Clarence, rebelled in 1469, deposing Edward and returning Henry to the throne.

But Edward wasn’t gone for long. He recovered his crown in 1471 – after destroying his enemies at Tewkesbury – and ruled for a further 12, relatively stable years. During this time, he moved between his palaces in the Thames Valley, settled on Windsor for his burial and embarked on the reconstruction of St George’s Chapel as the spiritual heart of the house of York.

He dispatched his eldest son, Edward Prince of Wales, to Ludlow Castle to govern Wales, and saw to it that his brother, Richard Duke of Gloucester, became lord of the north.

This period of peace was to come to an abrupt end on Edward’s death in 1483. The king’s son and successor, Edward V, was deposed and consigned to the Tower by the Duke of Gloucester, who was himself to meet a violent death as Richard III two years later.

Richard may not have reigned long but he did have time to transfer Henry VI’s body to St George’s Chapel in a symbolic act of reconciliation with the Lancastrian line. That wasn’t enough to stop the bloodshed. In 1485, at the battle of Bosworth, Richard was killed and Henry VII (nephew of Henry VI) became the first Tudor king.

Shakespeare and almost everybody since has hailed Henry VII as England’s saviour and celebrated the battle as the end of the Wars of the Roses. In doing so, however, they have merely been regurgitating Tudor propaganda, promulgated at once to deter resistance.

In reality, Henry had to contend with a host of plots and a succession of rivals – this despite the fact that he had married Elizabeth of York, the daughter of Edward IV. Their son, Henry VIII, was thus the heir of Lancaster and York, the red and the white rose.

Yet Henry VII decided not to join in death his father-in-law, Edward IV, and his uncle, Henry VI at Windsor, choosing instead to build a grand new Lady Chapel at Westminster Abbey for himself. This splendidly florid structure proclaimed that the Wars of the Roses were over and that the new Tudor dynasty had arrived.

Where history happened 1) Ludlow Castle, ShropshireThe medieval history the Crowland Chronicle claims that the Wars of the Roses started with the rout of Ludford in 1459. Faced by Henry VI’s Lancastrian army, the Yorkists deserted their troops and fled abroad.

Ludlow Castle, near to Ludford, was the principal seat of Richard Duke of York. It was here that his elder sons, Edward (the future Edward IV) and Edmund, were brought up. When York fled, his duchess was arrested and the town was sacked.

Ludlow Castle was built by Richard’s Mortimer ancestors to contest the Welsh, and still towers above the river Teme. Wales was governed from here from 1473 in the name of Prince Edward, the future Edward V, by Henry VII’s son, Prince Arthur, and by the Council of Wales.

Ludlow’s walls, keep, chapel and apartments remain intact, but it is entirely roofless. What it also lacks now are the furnishings, hangings and other decorations that made a luxurious 15th-century palace out of a rugged fortress.

Tel: 01584 873355

www.ludlowcastle.com

Ludlow Castle. © Denis Kelly | Dreamstime.com

2) Bamburgh Castle, NorthumberlandThe royal castle at Bamburgh rears up on a rocky outcrop over the North Sea and Holy Island. Built to defend the north against the Scots, Bamburgh was one of the Northumbrian castles that resisted the Yorkists after 1461.

Several times the castles of Alnwick, Bamburgh, Dunstanburgh and Warkworth were held against Edward IV, taken, and seized again by the Lancastrians. When the Earl of Warwick besieged the castle in 1464, his army was left starving, dispirited and sodden by the wintry Northumbrian rain.

After the Lancastrians’ final defeat at Hexham in 1462, Bamburgh fought on. The Yorkists bombarded it with their great guns and the garrison eventually surrendered. Its commander was excavated from the debris and suffered a traitor’s death at York. Only Harlech in north Wales held out.

Most of the buildings of Bamburgh Castle survive, albeit much restored. Visible for many miles around, this remains a glorious memorial both to the Scottish wars and to Northumbrian resistance to the Yorkists.

Tel: 01668 214515

www.bamburghcastle.com

3) Raglan Castle, MonmouthshireRaglan Castle was the seat of William Herbert, the first Welshman to rise into the nobility after the English conquest of the country. He was the right-hand man in Wales both of Richard Duke of York and his son Edward IV. It was Herbert who captured Harlech Castle for the Yorkists and he was created Earl of Pembroke for his efforts.

The new earl made himself the greatest and richest man in Wales. Onto an existing castle,

he added a prodigious tower that possessed every conceivable 15th-century mod con. However Herbert’s rise terrified the Earl of Warwick into rebellion in 1469 and, in the subsequent battle, Herbert was killed leading an army of Welshmen.

Herbert’s descendants occupied Raglan until it was slighted in the English Civil War. It now remains a splendid ruin. The great gatehouse still features impressive machicolations (through which objects could be thrown at attackers) and the great tower has large windows opening into what once was the most stately suite of rooms.

Tel: 01291 690228

www.cadw.wales.gov.uk

Raglan Castle, Monmouthshire. © Sandra Richardson | Dreamstime.com

4) Gainsborough Old Hall, LincolnshireGainsborough Old Hall was built by Sir Thomas Burgh, master of the horse to Edward IV. He made himself the greatest man in Lincolnshire during the eclipse of the local Lancastrian lords, Welles and Willoughby.

Yet the lords made their peace with Edward and were restored. They found Burgh in their way and late in 1469 they sacked his house at Gainsborough. When an angry Edward IV threatened vengeance, they rebelled in support of the Duke of Clarence. Defeated at Empingham in 1470, Lord Welles and his son were executed, leaving Burgh in charge as the king’s man in Lincolnshire.

Gainsborough Old Hall is the monument to his wealth, his eminence, and to civilian life at the heart of civil war. Certainly not defensible, it is a huge black-and-white, timber-framed house, now partly fronted with mellow red brick with a stone bay window and a tower.

Tel: 01684 850959

www.gainsborougholdhall.com

5) Tewkesbury Abbey, GloucestershireThe Benedictine abbey of Tewkesbury, one of the greatest monasteries outside royal hands, was modernised by the Younger Despenser in the 1300s. Warwick the Kingmaker’s mother-in-law, Isabel Despenser, and son-in-law, Clarence, were both laid to rest here.

It was also at Tewkesbury, in 1471, that the Lancastrian army of Queen Margaret of Anjou was caught by Edward IV and decisively defeated in the fields overlooked by the abbey. Henry VI’s son, Prince Edward of Lancaster, was killed in the field or executed immediately afterwards.

The fleeing Lancastrians who took refuge in the abbey emerged when promised their lives, but were slaughtered nevertheless. Many of them were buried with the prince in the abbey church, which had to be reconsecrated.

Of the battle itself, there is little to see, but the abbey church, one of the greatest noble mausolea, was saved at the Reformation. It still contains a semi-circle of burial chapels and the marked graves, both of Prince Edward and Clarence.

Tel: 01455 290429

www.tewkesburyabbey.org.uk

Tewkesbury Abbey. © Chrisp543 | Dreamstime.com