MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 105

April 23, 2016

History Trivia - Battle of Contarf Brian Boru

April 23

1014 Battle of Clontarf Brian Boru (High King of Ireland in 1002) defeated Viking invaders, but was killed during the battle

1014 Battle of Clontarf Brian Boru (High King of Ireland in 1002) defeated Viking invaders, but was killed during the battle

Published on April 23, 2016 01:00

April 22, 2016

Game of Thrones season six: the real-life medieval history

History Extra

Maisie Williams as Arya Stark in the sixth season of Game of Thrones, which airs on Sunday (Monday morning in Britain). © 2016 Home Box Office, Inc.

Maisie Williams as Arya Stark in the sixth season of Game of Thrones, which airs on Sunday (Monday morning in Britain). © 2016 Home Box Office, Inc. George RR Martin, author of the books upon which the Game of Thrones television show is based, notes that the battle for the Iron Throne is loosely based on the 15th-century Wars of the Roses; the chime of Stark and York and Lannister and Lancaster suggests as much. But Martin draws much more eclectically on medieval cultures, as the following examples demonstrate.

Queen CerseiCersei has been compared to a good number of medieval queens, such as Margaret of Anjou (d1482), wife of Henry VI. To my mind, though, Cersei, the “green-eyed lioness” of the Lannisters, is much more like Edward II’s queen Isabella, the ‘She-Wolf of France’. Daughter of King Philip IV (the Fair) of France, Isabella was sister of his three successors. She was married, probably aged 12, to Edward II of England in 1308. Edward gave her four children, but, notoriously, he neglected her for his good-looking male favourites.

His barons forced Edward to give up one of these favourites, Piers Gaveston, 1st Earl of Cornwall, who was executed in 1312, but by 1320 Edward was deeply involved with Hugh Despenser the Younger. As a consequence of Isabella’s hostility to the Despenser faction, her lands in England were taken from her, as were her children, and her household was broken up.

Cersei Lannister played by Lena Headey and Jaime Lannister played by Nikolaj Coster-Waldau. ©2015 Home Box Office, Inc.

Isabella and Edward had effectively separated. When, in 1325, her eldest son, the future Edward III, went to France to do homage for the province of Gascony, which the English crown held from the French king, the queen seized her chance. In Paris Isabella took the exiled English lord Roger Mortimer as her lover, and they plotted against her husband.

Young Edward was promised in marriage to Philippa, daughter of William, Count of Hainault, in the Low Countries. In return William provided men and an advance on Philippa’s dowry. Borrowing heavily from Italian banking houses, Isabella, her son and Mortimer invaded England in 1326 and Edward II was overthrown. How far Isabella was complicit in her husband’s horrible death in 1327 isn’t clear, but she and Mortimer ruled England for the next four years.

In 1330 her son, Edward III, took charge of the kingdom, imprisoning his mother and executing her lover. Perhaps King Tommen will similarly assert himself against his mother in this sixth season?

Isabella of France, aka the 'She-Wolf of France', queen consort of Edward II of England. From the book ‘Our Queen Mothers’ by Elizabeth Villiers, c1800. (Photo by Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

The Iron Bank of Braavos and the SparrowsThe parallels between Isabella and Cersei are striking: adultery, complicity in their husbands’ deaths and attempts to rule through their sons. Isabella and Mortimer were able to raise funds for their expedition from the Italian bankers because Edward II had defaulted on his debts to them; Isabella and Edward III promised to resume repayments.

Just so, the Iron Bank of Braavos was ready to support Stannis against Tommen, once Cersei had defaulted on the huge sums owed to the Bank. The Crown’s financial crisis also drove Cersei to strike a deal with the Sparrows, the fanatical grassroots movement that has taken over the Faith, and to allow them to arm themselves in return for forgetting the money the Crown had borrowed.

The Sparrows resemble the Franciscan movement, founded by St Francis in around 1209. The Franciscans sought to return to a simpler, less money-obsessed form of Christianity. Franciscan brothers (friars) were sworn to poverty and wandered from place to place preaching the Gospel to ordinary folk in language they could understand. The Sparrows of the Faith, however, combine their contempt for riches with a strict sexual morality and with the power, like that of the Inquisition, to compel sinners into religious courts and to punish them for their offences – as Cersei and Margaery have discovered.

c1220, a portrait of Saint Francis of Assisi kneeling at an rock altar to pray with a skull in his hand. (Photo by Archive Photos/Getty Images)

The IronbornWe haven’t seen much of the Ironborn, the Westerosi sea-borne warriors, since season four. Fierce piratical fighters, depending on their swift, stable and beautifully designed longships for speed and manoeuvrability, the Ironborn live by raiding their neighbours and by selling their captives into slavery in Volantis. So too the Vikings (9th-11th centuries) depended on their longships to raid along the coasts of Europe, journeying down the rivers of Russia to the Black Sea, around the Mediterranean, and of course across the North Sea to the British Isles.

We tend to think of the Vikings as mostly interested in easily portable plunder, but in fact they were active in the European slave trade. One Icelandic saga relates how a beautiful slave-woman was acquired by an Icelander at the market on an island off southern Sweden. Melkorka turned out to be the daughter of an Irish king and her son became one of the richest men in Iceland.

Vikings exploited the market for blond-haired, well-educated slaves in the Greek empire. They raided in the Baltic territories and sold their Slav captives in Constantinople: the origin of our word ‘slave’. Vikings were also farmers and traders as well as raiders; the Word of House Greyjoy, ‘We Do Not Sow’, would not have resonated with those Vikings who lived long enough to settle with a wife and family wherever they could find land, in Scandinavia, northern Britain, Ireland or Iceland.

Viking ships arriving in Britain, c1130. Found in the collection of Pierpont Morgan Library. Artist: Abbo of Fleury. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

The DothrakiAfter a long absence from Game of Thrones the Dothraki are set to return. Loosely based on the central Asian Mongol peoples, these copper-skinned nomadic warriors are also involved in slaving and raiding around the grasslands of the Dothraki Sea.

The Mongols ruled over the largest land empire the world has ever seen, from the Pacific Ocean to Hungary. Western churchmen often visited them during the 13th century, bringing letters from western kings and from the pope. The friars wrote detailed accounts of their journeys, relating how difficult the weather was and how strange the food and drink. Fermented mare’s milk, or kumiss, was a poor substitute for wine, though they liked the spicy horsemeat sausages.

Genghis Khan, Mongol ruler, originally named Temujin, 1683 Woodcut. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

The Mongols held all other peoples in contempt, reports one writer. Hearing about the kingdom of France, they asked “whether there were many sheep and cattle and horses there, and whether they had not better go there at once and take it all”. Will the Dothraki who have captured Daenerys be quite so ambitious? Khal Drogo swore to take his men in the “wooden horses” (ships) to attack Westeros and capture the Iron Throne for his beloved wife, but traditionally the Dothraki have never sailed across the Narrow Sea.

Overall, then, Game of Thrones’ extraordinary hold on people’s imaginations has much to do with the way it harnesses mythology and legend: archetypes such as the dragons and the Three-Eyed Raven; the tales of lost children and reanimated corpses. Yet it’s the realness of the re-imagined medieval pasts it brings so vividly to life that makes viewers believe in Essos, the Seven Kingdoms and the battle for the Iron Throne.

Carolyne Larrington teaches medieval English literature at St John’s College, Oxford. She is the author of Winter is Coming: The Medieval World of Game of Thrones (IB Tauris, November 2015).

The first episode of the sixth season of Game of Thrones airs in Britain on Sky Atlantic at 2am on Monday 25 April (and in America on HBO at 9pm EST on Sunday 24 April).

Published on April 22, 2016 05:49

7 things you (probably) didn’t know about William Shakespeare

History Extra

Title page from the first folio edition of Shakespeare's plays, published in 1623. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

1) ‘William Shakespeare’ was ‘a weakish speller’One of the most curious facts about William Shakespeare is that his name can be reshuffled to create the sentence ‘I am a weakish speller’. We might wish for a more heroic anagram for one of our nation’s greatest playwrights, but unfortunately ‘I am a weakish speller’ does in fact ring true when applied to Shakespeare.

It was a man named Donald L Holmes who first discovered the anagram, possibly while musing about the frivolity of early modern orthography (the art of writing words with the proper letters). Shakespeare was writing in the era before Samuel Johnson’s dictionary – which started the process of standardising English spelling – so he was rather relaxed about words. Indeed, he could not even decide how to spell his own name. Consider the following variants on his signature when he was finalising legal documents such as the mortgage deeds on property in Blackfriars, and his will: Shaksper, Shakespe, Shakespere, and Shakspeare.

See also the spelling in the 1599 edition of Romeo and Juliet:

Two households, both alike in dignitie,

(In faire Verona where we lay our Scene),

From auncient grudge, break to new mutinie,

Where civill bloud makes civill hands uncleane.[image error]

Title page of 'Romeo and Juliet’, 1599 edition. (© Mary Evans Picture Library/Alamy Stock Photo)

2) Had it not been for a fatal brawl in 1587 we may never have heard of William ShakespeareNobody really knows how young Shakespeare made his way from his childhood home of Stratford-upon-Avon to the bustle of Elizabethan London and playhouse glory. There are several theories about what he did when he first arrived in the capital, including the famous story that he was employed as a kind of valet – looking after playgoers’ horses while they enjoyed the show. Whether or not this is true – and there is no reason why it should not be – we still don’t know how Shakespeare was first introduced into theatrical society, or the circumstances in which he left Stratford.

The best theory I have heard involves two angry men and a sharp sword. It was the year 1587. The Queen’s Men [a major acting company whose patron was Queen Elizabeth] were on a summer tour, bringing the latest hit plays to the provinces. Life on the road for a troupe of players cannot have been easy and tempers were beginning to fray. On the night of 13 June, the actor William Knell attacked his colleague John Towne with a sword. Towne fled but was cornered and struck back, inflicting a fatal stab wound on Knell.

The Queen’s Men were now officially short-staffed. A few days later they arrived in Stratford-upon-Avon where fate may have united them with William Shakespeare. Nobody knows exactly how they first met, but Shakespeare would have seen the Queen’s Men perform in Stratford.

3) The character Emilia in Othello may have been based on a real-life loverGenerations of Shakespeare biographers have portrayed Shakespeare’s love life as being a rather colourful one. His purported lovers include figures such as Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton; a brothel keeper called Lucy Morgan, and the courtier Emilia Lanier.

Emilia is one of the candidates for Shakespeare’s ‘dark lady’, that shadowy figure who inspired some of his most passionate sonnets. Lanier was a poet in her own right, producing some of the earliest feminist work in the English language. With titles including Eve’s Apologie in Defence of Women, she exposes double standards, asking mutinously: “Why are poore women blam’d, or by more faultie men defam’d?”

Some scholars believe that Shakespeare had Lanier in mind when he wrote the character Emilia in Othello. Indeed, Emilia has some of the most feminist lines in the whole of Shakespeare:

Let husbands know

Their wives have sense like them: they see and smell

And have their palates both for sweet and sour

As husbands have.Emilia Lanier’s father was also a Venetian, so it may not be a coincidence that Othello is partially set in Venice.

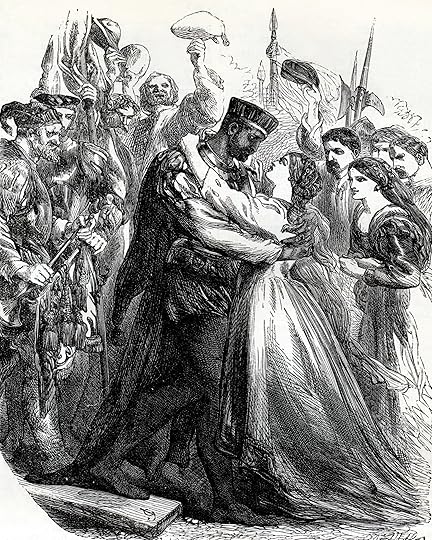

An engraving from William Shakespeare's play ‘Othello’ depicting the character Iago embracing his wife, Emilia. (© Lebrecht Music and Arts Photo Library/Alamy Stock Photo)

4) Shakespeare has been translated into 80 languages, including Klingon and EsperantoIf Shakespeare knew how far his work has travelled in the 400 years since his death, he would be amazed. His original audiences included people from all walks of life, from kings and queens to prostitutes and fish mongers, but they all had one thing in common: the English language. Shakespeare was writing in the Elizabethan ‘golden age’ of exploration, but his world was essentially limited to the confines of our island.

Like the English language itself, Shakespeare’s work has since broken free of its restraints to travel across the globe – and even beyond. In 2000, Star Trek fans produced a translation of Hamlet in Klingon, in an effort to restore Shakespeare to its ‘original’ language. The Prince of Denmark begins his most famous speech not with “to be or not to be”, but with “taH pagh taHbe”. Unsurprisingly, most people prefer the earthling version and the Klingon Hamlet is rarely, if ever, performed.

Shakespeare has also been translated into Esperanto, the artificial language based on the structure of major European tongues. Translations include Reĝo Lear, Rikardo Tria and La Komedio de Eraroj.

It should also be remembered that Shakespeare himself enjoyed languages and wrote a whole scene in French for the play Henry V.

5) William was not the only Shakespeare working in the playhouses of LondonAt some point, William’s younger brother Edmund followed him down to London. Edmund is one of those intriguing characters in history whose name appears in one or two documents and then disappears from view. We have therefore only the barest details of his short life, but with a bit of imagination it is just about possible to sketch an idea of who he was.

Born in 1580, Edmund lived in the Cripplegate area of London, just outside the city walls. It was a short stroll away from William’s lodgings on Silver Street, so the two brothers would have found it easy to maintain contact with each other. Yet despite the proximity of their lodgings and Edmund’s profession as an actor, there is no record that the pair ever worked together. While William was forging a dazzling career at the Globe on Bankside, it is likely that Edmund worked with Edward Alleyn at the Fortune near Shoreditch.

Edward Alleyn, an English actor and a major figure of the Elizabethan theatre, c1615. (Photo by Kean Collection/Getty Images)

The year 1607 was bitter-sweet for the Shakespeare clan. Edmund fathered an illegitimate son, baptised Edward, but sadly the infant died and Edmund followed him to the grave months later aged 27. We do not know how he died but William ensured he was buried with dignity at the church of St Saviour’s (now Southwark Cathedral).

6) The longest word in Shakespeare is honorificabilitudinitatibusAlthough he showed off his French skills in Henry V, Shakespeare was sparing when it came to the use of Latin. With such diverse audiences, he needed to ensure that everyone could understand what was going on in his plays. His friend and rival Ben Jonson scattered Latin liberally throughout his own plays and sneered that Shakespeare had “small Latin and little Greek”. Jonson’s slur was not entirely correct, however. Witness Shakespeare’s use of the word honorificabilitudinitatibus in the play Love’s Labour’s Lost. The Collins English Dictionary definition of the word is “invincible glorious honorableness. It is the ablative plural of the Latin contrived honorificabilitudinitas…”

The word is spoken by the clown Costard in a scene that contains plenty of jokes about unnecessary wordiness: “I marvel thy master hath not eaten thee for a word; for thou art not so long by the head as honorificabilitundinitatibus: thou art easier swallowed than a flap-dragon.”

It was a comic scene and precedes one in which several characters try out their Latin on each other and make fun of Armado for his over-blown speech patterns. It is tempting to imagine the Latin-mad Ben Jonson seeing his reflection in Armado.

7) He caused an ecological disaster in New YorkShakespeare may be wildly popular all over the world but there was a time when the people of New York may have cursed his name. In 1890 a German-American named Eugene Scheiffelin took the extraordinary step of importing 60 starlings from England to New York (and a further 40 the following year). As an avid Shakespeare fan and zoologist it was Scheiffelin’s dream for America to be the home of each bird species featured in the works of the bard. As well as the romance of bringing a little bit of England to New York, Scheiffelin wanted to see if non-native species could thrive there, so duly released the starlings into Central Park.

Unfortunately for the American eco-system the starlings thrived a little too well and bred rapidly, out-competing the local fauna for food and habitat. It is currently one of only three birds in the US not afforded any state protection (the other two being the house sparrow and the pigeon) and is treated as a pest. Ironically, the starling only appears in one line in the whole of Shakespeare. In the play Henry IV, Part I, Hotspur fantasises about using one of them to plague his enemy: “Nay, I’ll have a starling shall be taught to speak nothing but ‘Mortimer’, and give it him to keep his anger still in motion.”

Zoe Bramley is the author of William Shakespeare in 100 Facts (Amberley Publishing, 2016).

Title page from the first folio edition of Shakespeare's plays, published in 1623. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

1) ‘William Shakespeare’ was ‘a weakish speller’One of the most curious facts about William Shakespeare is that his name can be reshuffled to create the sentence ‘I am a weakish speller’. We might wish for a more heroic anagram for one of our nation’s greatest playwrights, but unfortunately ‘I am a weakish speller’ does in fact ring true when applied to Shakespeare.

It was a man named Donald L Holmes who first discovered the anagram, possibly while musing about the frivolity of early modern orthography (the art of writing words with the proper letters). Shakespeare was writing in the era before Samuel Johnson’s dictionary – which started the process of standardising English spelling – so he was rather relaxed about words. Indeed, he could not even decide how to spell his own name. Consider the following variants on his signature when he was finalising legal documents such as the mortgage deeds on property in Blackfriars, and his will: Shaksper, Shakespe, Shakespere, and Shakspeare.

See also the spelling in the 1599 edition of Romeo and Juliet:

Two households, both alike in dignitie,

(In faire Verona where we lay our Scene),

From auncient grudge, break to new mutinie,

Where civill bloud makes civill hands uncleane.[image error]

Title page of 'Romeo and Juliet’, 1599 edition. (© Mary Evans Picture Library/Alamy Stock Photo)

2) Had it not been for a fatal brawl in 1587 we may never have heard of William ShakespeareNobody really knows how young Shakespeare made his way from his childhood home of Stratford-upon-Avon to the bustle of Elizabethan London and playhouse glory. There are several theories about what he did when he first arrived in the capital, including the famous story that he was employed as a kind of valet – looking after playgoers’ horses while they enjoyed the show. Whether or not this is true – and there is no reason why it should not be – we still don’t know how Shakespeare was first introduced into theatrical society, or the circumstances in which he left Stratford.

The best theory I have heard involves two angry men and a sharp sword. It was the year 1587. The Queen’s Men [a major acting company whose patron was Queen Elizabeth] were on a summer tour, bringing the latest hit plays to the provinces. Life on the road for a troupe of players cannot have been easy and tempers were beginning to fray. On the night of 13 June, the actor William Knell attacked his colleague John Towne with a sword. Towne fled but was cornered and struck back, inflicting a fatal stab wound on Knell.

The Queen’s Men were now officially short-staffed. A few days later they arrived in Stratford-upon-Avon where fate may have united them with William Shakespeare. Nobody knows exactly how they first met, but Shakespeare would have seen the Queen’s Men perform in Stratford.

3) The character Emilia in Othello may have been based on a real-life loverGenerations of Shakespeare biographers have portrayed Shakespeare’s love life as being a rather colourful one. His purported lovers include figures such as Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton; a brothel keeper called Lucy Morgan, and the courtier Emilia Lanier.

Emilia is one of the candidates for Shakespeare’s ‘dark lady’, that shadowy figure who inspired some of his most passionate sonnets. Lanier was a poet in her own right, producing some of the earliest feminist work in the English language. With titles including Eve’s Apologie in Defence of Women, she exposes double standards, asking mutinously: “Why are poore women blam’d, or by more faultie men defam’d?”

Some scholars believe that Shakespeare had Lanier in mind when he wrote the character Emilia in Othello. Indeed, Emilia has some of the most feminist lines in the whole of Shakespeare:

Let husbands know

Their wives have sense like them: they see and smell

And have their palates both for sweet and sour

As husbands have.Emilia Lanier’s father was also a Venetian, so it may not be a coincidence that Othello is partially set in Venice.

An engraving from William Shakespeare's play ‘Othello’ depicting the character Iago embracing his wife, Emilia. (© Lebrecht Music and Arts Photo Library/Alamy Stock Photo)

4) Shakespeare has been translated into 80 languages, including Klingon and EsperantoIf Shakespeare knew how far his work has travelled in the 400 years since his death, he would be amazed. His original audiences included people from all walks of life, from kings and queens to prostitutes and fish mongers, but they all had one thing in common: the English language. Shakespeare was writing in the Elizabethan ‘golden age’ of exploration, but his world was essentially limited to the confines of our island.

Like the English language itself, Shakespeare’s work has since broken free of its restraints to travel across the globe – and even beyond. In 2000, Star Trek fans produced a translation of Hamlet in Klingon, in an effort to restore Shakespeare to its ‘original’ language. The Prince of Denmark begins his most famous speech not with “to be or not to be”, but with “taH pagh taHbe”. Unsurprisingly, most people prefer the earthling version and the Klingon Hamlet is rarely, if ever, performed.

Shakespeare has also been translated into Esperanto, the artificial language based on the structure of major European tongues. Translations include Reĝo Lear, Rikardo Tria and La Komedio de Eraroj.

It should also be remembered that Shakespeare himself enjoyed languages and wrote a whole scene in French for the play Henry V.

5) William was not the only Shakespeare working in the playhouses of LondonAt some point, William’s younger brother Edmund followed him down to London. Edmund is one of those intriguing characters in history whose name appears in one or two documents and then disappears from view. We have therefore only the barest details of his short life, but with a bit of imagination it is just about possible to sketch an idea of who he was.

Born in 1580, Edmund lived in the Cripplegate area of London, just outside the city walls. It was a short stroll away from William’s lodgings on Silver Street, so the two brothers would have found it easy to maintain contact with each other. Yet despite the proximity of their lodgings and Edmund’s profession as an actor, there is no record that the pair ever worked together. While William was forging a dazzling career at the Globe on Bankside, it is likely that Edmund worked with Edward Alleyn at the Fortune near Shoreditch.

Edward Alleyn, an English actor and a major figure of the Elizabethan theatre, c1615. (Photo by Kean Collection/Getty Images)

The year 1607 was bitter-sweet for the Shakespeare clan. Edmund fathered an illegitimate son, baptised Edward, but sadly the infant died and Edmund followed him to the grave months later aged 27. We do not know how he died but William ensured he was buried with dignity at the church of St Saviour’s (now Southwark Cathedral).

6) The longest word in Shakespeare is honorificabilitudinitatibusAlthough he showed off his French skills in Henry V, Shakespeare was sparing when it came to the use of Latin. With such diverse audiences, he needed to ensure that everyone could understand what was going on in his plays. His friend and rival Ben Jonson scattered Latin liberally throughout his own plays and sneered that Shakespeare had “small Latin and little Greek”. Jonson’s slur was not entirely correct, however. Witness Shakespeare’s use of the word honorificabilitudinitatibus in the play Love’s Labour’s Lost. The Collins English Dictionary definition of the word is “invincible glorious honorableness. It is the ablative plural of the Latin contrived honorificabilitudinitas…”

The word is spoken by the clown Costard in a scene that contains plenty of jokes about unnecessary wordiness: “I marvel thy master hath not eaten thee for a word; for thou art not so long by the head as honorificabilitundinitatibus: thou art easier swallowed than a flap-dragon.”

It was a comic scene and precedes one in which several characters try out their Latin on each other and make fun of Armado for his over-blown speech patterns. It is tempting to imagine the Latin-mad Ben Jonson seeing his reflection in Armado.

7) He caused an ecological disaster in New YorkShakespeare may be wildly popular all over the world but there was a time when the people of New York may have cursed his name. In 1890 a German-American named Eugene Scheiffelin took the extraordinary step of importing 60 starlings from England to New York (and a further 40 the following year). As an avid Shakespeare fan and zoologist it was Scheiffelin’s dream for America to be the home of each bird species featured in the works of the bard. As well as the romance of bringing a little bit of England to New York, Scheiffelin wanted to see if non-native species could thrive there, so duly released the starlings into Central Park.

Unfortunately for the American eco-system the starlings thrived a little too well and bred rapidly, out-competing the local fauna for food and habitat. It is currently one of only three birds in the US not afforded any state protection (the other two being the house sparrow and the pigeon) and is treated as a pest. Ironically, the starling only appears in one line in the whole of Shakespeare. In the play Henry IV, Part I, Hotspur fantasises about using one of them to plague his enemy: “Nay, I’ll have a starling shall be taught to speak nothing but ‘Mortimer’, and give it him to keep his anger still in motion.”

Zoe Bramley is the author of William Shakespeare in 100 Facts (Amberley Publishing, 2016).

Published on April 22, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Year of the Six Emperors

April 22

238 Year of the Six Emperors: The Roman Senate outlawed emperor Maximinus Thrax for his bloodthirsty proscriptions in Rome and nominated two of its members, Pupienus and Balbinus, to the throne.

238 Year of the Six Emperors: The Roman Senate outlawed emperor Maximinus Thrax for his bloodthirsty proscriptions in Rome and nominated two of its members, Pupienus and Balbinus, to the throne.

Published on April 22, 2016 01:30

April 21, 2016

The death of Caesar: do we know the whole story?

History Extra

A bust of Gaius Julius Caesar. By March 44 BC, the great general had made some powerful enemies by increasingly acting like a monarch. © Alamy

A bust of Gaius Julius Caesar. By March 44 BC, the great general had made some powerful enemies by increasingly acting like a monarch. © Alamy

What do you say, Caesar? Will someone of your stature pay attention to the dreams of a woman and the omens of foolish men?” So said Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus to Gaius Julius Caesar. The 36-year-old Decimus spoke frankly to a man his elder by nearly 20 years, a man who was not only his chief but also Rome’s Dictator for Life. Yet Caesar was fond of Decimus, a longtime comrade-in-arms and a trusted lieutenant, and so he let him speak. They met in Caesar’s official residence in the heart of Rome.

It was the morning of 15 March 44 BC – the Ides, as the Romans called the approximate middle of each month: the Ides of March. The Senate was in session that day, its members eagerly awaiting the dictator’s arrival. Yet Caesar had decided not to attend – allegedly because of bad health but, in fact, the real cause was a series of ill omens that had terrified his wife, Calpurnia.

Decimus changed Caesar’s mind. Caesar decided to go to the Senate meeting after all, if only to announce a postponement in person. What he didn’t know was that more than 60 conspirators were waiting for him there, their daggers ready. Decimus, however, was all too aware – he was one of the plots’ ringleaders, and his actions that morning were about to change the course of history.

Despite this, most historians have traditionally cast Brutus and Cassius as the brains behind the conspiracy. In doing so, they’ve followed the lead of Plutarch, who wrote 150 years after the assassination, and Shakespeare, who drew most of his story from Plutarch. They tend to omit Decimus, who Shakespeare misnames ‘Decius’ and mentions only in the scene described above. Yet Decimus was key. His motives are less opaque than most think and his behaviour shows just how well organised the conspirators were.

The earliest surviving, detailed source for Caesar’s assassination makes Decimus the leader of the conspiracy. Sometime within a few decades of the Ides of March, Nicolaus of Damascus, a scholar and bureaucrat, wrote a Life of Caesar Augustus – that is, of Augustus, Rome’s first emperor (reigned 27 BC–AD 14). A later abridgment of this work survives and it focuses on the assassination.

Until recently, scholars have tended to dismiss Nicolaus because he worked for Augustus and so had a motive to attack the conspirators. But recent work suggests that Nicolaus was a brilliant student of human nature who deserves more attention. A series of letters between Decimus and Cicero, all written after the assassination, also shed light on the plot, but they too have been neglected.

This coin, issued by Brutus, one of the plot’s ringleaders, displays the military daggers employed against Caesar. © Topfoto

Things turn sourUnlike Brutus and Cassius, Decimus was Caesar’s man. In the civil war between Caesar and the Roman general Pompey (49–45 BC), Brutus and Cassius both supported Pompey and then later changed sides. By contrast, Decimus backed Caesar from start to finish. During the conflict, Caesar appointed Decimus as his lieutenant to govern Gaul in his absence. At the war’s end in 45 BC, Decimus left Gaul and returned to Italy with Caesar.

Then things turned sour. Between September 45 BC and March 44 BC Decimus changed his mind about Caesar. We don’t know why but it probably had more to do with power than principle. Decimus’s letters to Cicero reveal a polite if terse man of action with a keen sense of honour, a nose for betrayal, and a thirst for vengeance.

Perhaps what moved Decimus was the sight of the two triumphal parades in Rome in autumn 45 BC that Caesar allowed his lieutenants in Spain to celebrate, against all custom. Caesar did not, however, grant a similar privilege to Decimus for his victory over a fierce Gallic tribe.

Or perhaps it was Caesar’s appointment of his grandnephew Octavian (as Augustus was then known) as his second-in-command in a new war in 44 BC against Parthia (roughly, ancient Iran), Rome’s rival in the eastern Mediterranean. Decimus meanwhile had to stay behind and govern Italian Gaul.

Whatever his motives, once he turned on Caesar, Decimus was indispensable. He was both the plotters’ chief of security and their leading spy. As the only conspirator in Caesar’s inner circle, Decimus was a mole, able to report on what Caesar was thinking. What’s more, Decimus controlled a troupe of gladiators, which played a key role on the Ides.

Caesar remained in Rome between October 45 and March 44 BC – his longest stay there for years. He never revealed a programme but his actions betrayed that he aimed to change Rome’s government. He behaved in ever-more dictatorial ways, summed up in his adoption of the unprecedented title of Dictator for Life.

He maintained Rome’s traditional republican magistracies but elections increasingly became mere formalities – Caesar had the real power of appointment. Consuls, praetors (magistrates) and senators saw power shifting to Caesar’s secretaries and advisors – some of them had only recently become Roman citizens; some were even freedmen (former slaves). Caesar was not a king, but he had acquired the equivalent of royal power.

There was another issue at play here – the prospect of what would happen after Caesar’s death. To his critics, the favour he showed to Octavian raised the terrifying prospect of a dynasty.

Some Romans responded to Caesar’s growing power with flattery. They voted him a long stream of honours including, most egregiously, naming him a god, with plans afoot for priests and a temple. Others, however, decided that he had to be stopped, and so they decided on assassination. True, they acted in the name of the Republic and liberty and against a budding monarchy but they also saw in his growing influence a threat to their own power and privilege.

Plans to assassinate Caesar are attested as early as the summer of 45 BC but the conspiracy that struck on the Ides of March did not gel until February 44 BC. At least 60 men joined it (of whom we can identify just 20 today – and some of them are little more than names). According to a later writer, Seneca, the majority of the conspirators were not Caesar’s enemies – former allies of Pompey – but his friends and supporters.

That certainly can’t be said for Brutus and Cassius, the best-known conspirators. Cassius was a military man and a former Pompey supporter who despised Caesar’s dictatorial ways. As for Brutus, he was hardly the friend of Caesar whom Shakespeare depicts.

Brutus’s mother was Caesar’s former mistress. However, Brutus supported Pompey until the latter lost to Caesar on the battlefield in 48 BC, at which point Brutus switched sides. He promptly betrayed his ex-chief by providing Caesar intelligence about the likely whereabouts of Pompey, who had escaped after the battle. Afterwards, Caesar rewarded Brutus with high office.

This, however, was to prove the high point of Caesar and Brutus’s relationship. In the summer of 45 BC, Brutus divorced his wife and remarried. His new bride was Porcia, his cousin and, far more pertinently to this story, daughter of Caesar’s late archenemy Cato.

Crucially, in the winter of 44 BC, Caesar’s opponents began calling on Brutus to uphold the tradition of his ancestors, who included the founder of the Roman Republic, Lucius Junius Brutus, the man who had led the expulsion of Rome’s kings hundreds of years earlier. And so, through a combination of pride, principle – and, perhaps, love for his wife – Brutus turned on Caesar.

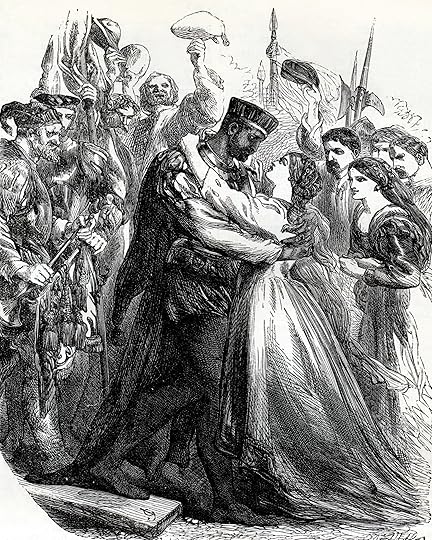

A posse of senators stab Caesar to death in Vincenzo Camuccini’s painting, completed in c1798. The plot succeeded, says Barry Strauss, because it was planned with military precision: after isolating their victim, the assassins acted rapidly and ruthlessly. © Getty

Military precisionThe plot to assassinate Caesar succeeded because it was meticulously planned, and flawlessly executed. With generals such as Decimus, Cassius and Caesar’s veteran commander Trebonius involved, one would expect nothing less than military precision. The assassins chose to end Caesar’s life themselves rather than by hiring killers – a decision that showed their seriousness of purpose. And by striking at a Senate meeting they made it a public act rather than a private vendetta – an assassination and not a murder.

That this was a professional operation is even reflected in the killers’ choice of weapon. Caesar’s assassins attacked him with daggers and not, as is sometimes imagined, with swords. The latter were too big to sneak into the Senate House and too unwieldy for use in close quarters. In particular, the killers used a military dagger (the pugio), which was becoming standard issue for legionaries.

Military daggers were not only practical weapons but also honourable ones. Caesar’s supporters later called the assassins common criminals and accused them of using sicae, a short, curved blade that had the negative connotation of a switchblade or flick knife. So, in 44 BC, Brutus issued a coin that celebrated the Ides of March with two military daggers. Again, he wanted to show that the assassins were no mere murderers.

The Roman Senate House still stands in the Roman Forum and most visitors assume that Caesar was killed there – but he was not, nor on the Capitoline Hill, as Shakespeare states. The assassination took place about half a mile away from the Forum in Pompey’s Senate House, ironically built by Caesar’s great rival. It was part of a huge complex including a theatre, a park, a covered portico, and shops and offices. Gladiatorial games took place in the theatre on the Ides of March, which gave Decimus an excuse for deploying his gladiators near Pompey’s Senate House. Their real purpose was as a backup security force.

As a general, Caesar had a bodyguard but he made a point of dismissing it after returning to civilian life in Rome. He wanted to seem accessible and fearless. What’s more, only senators could enter a Senate meeting, so most of Caesar’s retinue would have had to remain outside the building. This made the dictator uniquely vulnerable inside the Senate House. Still, Caesar had appointed many of the senators personally, and they included military men. If they came to Caesar’s aid, they could overwhelm the assassins.

The assassins’ response to this threat was to attack at speed, isolating their target before striking. Even before Caesar took his seat on the tribunal, several assassins stood behind the chair while others surrounded him as if trying to grab his attention. The truth is that they were forming a perimeter.

Then the attack sprang into action. Tillius Cimber, a hard-drinking scrapper of a soldier whom Caesar favoured, held his hands out disrespectfully and pulled at Caesar’s toga. At this signal, his co-conspirators struck, led by Publius Servilius Casca.

Caesar immediately called out to Cimber, “Why, this is violence”, and hurled an oath at Casca, labelling him either “impious” or “accursed”. However, he never said: “Et tu, Brute?” (“You too, Brutus?”) – that phrase is a Renaissance invention. Ancient authors report a rumour that Caesar said to Brutus, in Greek: “You too, child.” But they doubt that he even said that.

Caesar, the old warrior, tried to fight back. He stabbed Casca with his stylus – a small, pointed, iron writing utensil – and managed to get back up. Two of his supporters among the senators, Lucius Marcius Censorinus and Gaius Calvisius Sabinus, then attempted to reach him but the conspirators blocked their way, and forced them to flee.

Meanwhile, Trebonius had been assigned to buttonhole his old comrade Mark Antony and engage him in conversation outside the Senate’s door. Antony was a veteran soldier, strong, dangerous and loyal to Caesar. If he’d entered the Senate room, he would have sat on the tribunal with Caesar and could have come to his aid.

With Mark Antony detained by Trebonius, there was little Caesar could do to defend himself. It probably took only minutes for him to die – succumbing to what most of the sources state were 23 wounds. Before the end, he wrapped his toga around his face and, in an ironic turn of events, fell at the foot of a statue of his rival, Pompey.

For all its brilliance, the plot to kill Caesar didn’t prove the panacea that the assassins hoped. Civil war soon broke out again and, to a man, they were to suffer violent deaths. What’s more, the Republic that they aimed to defend perished and gave way to an empire. That, however, does not brand them as foolish idealists. It merely shows that their political acumen did not match the military skill they displayed on the Ides of March.

In context: CaesarBy 44 BC Gaius Julius Caesar was the most famous and controversial man in Rome. A populist political star and great writer, he excelled in the military realm as well, pulling off a lightning conquest of Gaul – roughly, France and Belgium – as well as invading Britain and Germany (58–50 BC). When his enemies, the old guard in the Senate, removed him from command, Caesar invaded Italy. He went on to total victory in a civil war (49–45 BC) that ranged across the Mediterranean. His challenge now was to reconcile his surviving enemies and to convince staunch republicans to accept his power as dictator. It was a daunting task.

Barry Strauss (@barrystrauss) is a professor of history and classics at Cornell University.

A bust of Gaius Julius Caesar. By March 44 BC, the great general had made some powerful enemies by increasingly acting like a monarch. © Alamy

A bust of Gaius Julius Caesar. By March 44 BC, the great general had made some powerful enemies by increasingly acting like a monarch. © Alamy What do you say, Caesar? Will someone of your stature pay attention to the dreams of a woman and the omens of foolish men?” So said Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus to Gaius Julius Caesar. The 36-year-old Decimus spoke frankly to a man his elder by nearly 20 years, a man who was not only his chief but also Rome’s Dictator for Life. Yet Caesar was fond of Decimus, a longtime comrade-in-arms and a trusted lieutenant, and so he let him speak. They met in Caesar’s official residence in the heart of Rome.

It was the morning of 15 March 44 BC – the Ides, as the Romans called the approximate middle of each month: the Ides of March. The Senate was in session that day, its members eagerly awaiting the dictator’s arrival. Yet Caesar had decided not to attend – allegedly because of bad health but, in fact, the real cause was a series of ill omens that had terrified his wife, Calpurnia.

Decimus changed Caesar’s mind. Caesar decided to go to the Senate meeting after all, if only to announce a postponement in person. What he didn’t know was that more than 60 conspirators were waiting for him there, their daggers ready. Decimus, however, was all too aware – he was one of the plots’ ringleaders, and his actions that morning were about to change the course of history.

Despite this, most historians have traditionally cast Brutus and Cassius as the brains behind the conspiracy. In doing so, they’ve followed the lead of Plutarch, who wrote 150 years after the assassination, and Shakespeare, who drew most of his story from Plutarch. They tend to omit Decimus, who Shakespeare misnames ‘Decius’ and mentions only in the scene described above. Yet Decimus was key. His motives are less opaque than most think and his behaviour shows just how well organised the conspirators were.

The earliest surviving, detailed source for Caesar’s assassination makes Decimus the leader of the conspiracy. Sometime within a few decades of the Ides of March, Nicolaus of Damascus, a scholar and bureaucrat, wrote a Life of Caesar Augustus – that is, of Augustus, Rome’s first emperor (reigned 27 BC–AD 14). A later abridgment of this work survives and it focuses on the assassination.

Until recently, scholars have tended to dismiss Nicolaus because he worked for Augustus and so had a motive to attack the conspirators. But recent work suggests that Nicolaus was a brilliant student of human nature who deserves more attention. A series of letters between Decimus and Cicero, all written after the assassination, also shed light on the plot, but they too have been neglected.

This coin, issued by Brutus, one of the plot’s ringleaders, displays the military daggers employed against Caesar. © Topfoto

Things turn sourUnlike Brutus and Cassius, Decimus was Caesar’s man. In the civil war between Caesar and the Roman general Pompey (49–45 BC), Brutus and Cassius both supported Pompey and then later changed sides. By contrast, Decimus backed Caesar from start to finish. During the conflict, Caesar appointed Decimus as his lieutenant to govern Gaul in his absence. At the war’s end in 45 BC, Decimus left Gaul and returned to Italy with Caesar.

Then things turned sour. Between September 45 BC and March 44 BC Decimus changed his mind about Caesar. We don’t know why but it probably had more to do with power than principle. Decimus’s letters to Cicero reveal a polite if terse man of action with a keen sense of honour, a nose for betrayal, and a thirst for vengeance.

Perhaps what moved Decimus was the sight of the two triumphal parades in Rome in autumn 45 BC that Caesar allowed his lieutenants in Spain to celebrate, against all custom. Caesar did not, however, grant a similar privilege to Decimus for his victory over a fierce Gallic tribe.

Or perhaps it was Caesar’s appointment of his grandnephew Octavian (as Augustus was then known) as his second-in-command in a new war in 44 BC against Parthia (roughly, ancient Iran), Rome’s rival in the eastern Mediterranean. Decimus meanwhile had to stay behind and govern Italian Gaul.

Whatever his motives, once he turned on Caesar, Decimus was indispensable. He was both the plotters’ chief of security and their leading spy. As the only conspirator in Caesar’s inner circle, Decimus was a mole, able to report on what Caesar was thinking. What’s more, Decimus controlled a troupe of gladiators, which played a key role on the Ides.

Caesar remained in Rome between October 45 and March 44 BC – his longest stay there for years. He never revealed a programme but his actions betrayed that he aimed to change Rome’s government. He behaved in ever-more dictatorial ways, summed up in his adoption of the unprecedented title of Dictator for Life.

He maintained Rome’s traditional republican magistracies but elections increasingly became mere formalities – Caesar had the real power of appointment. Consuls, praetors (magistrates) and senators saw power shifting to Caesar’s secretaries and advisors – some of them had only recently become Roman citizens; some were even freedmen (former slaves). Caesar was not a king, but he had acquired the equivalent of royal power.

There was another issue at play here – the prospect of what would happen after Caesar’s death. To his critics, the favour he showed to Octavian raised the terrifying prospect of a dynasty.

Some Romans responded to Caesar’s growing power with flattery. They voted him a long stream of honours including, most egregiously, naming him a god, with plans afoot for priests and a temple. Others, however, decided that he had to be stopped, and so they decided on assassination. True, they acted in the name of the Republic and liberty and against a budding monarchy but they also saw in his growing influence a threat to their own power and privilege.

Plans to assassinate Caesar are attested as early as the summer of 45 BC but the conspiracy that struck on the Ides of March did not gel until February 44 BC. At least 60 men joined it (of whom we can identify just 20 today – and some of them are little more than names). According to a later writer, Seneca, the majority of the conspirators were not Caesar’s enemies – former allies of Pompey – but his friends and supporters.

That certainly can’t be said for Brutus and Cassius, the best-known conspirators. Cassius was a military man and a former Pompey supporter who despised Caesar’s dictatorial ways. As for Brutus, he was hardly the friend of Caesar whom Shakespeare depicts.

Brutus’s mother was Caesar’s former mistress. However, Brutus supported Pompey until the latter lost to Caesar on the battlefield in 48 BC, at which point Brutus switched sides. He promptly betrayed his ex-chief by providing Caesar intelligence about the likely whereabouts of Pompey, who had escaped after the battle. Afterwards, Caesar rewarded Brutus with high office.

This, however, was to prove the high point of Caesar and Brutus’s relationship. In the summer of 45 BC, Brutus divorced his wife and remarried. His new bride was Porcia, his cousin and, far more pertinently to this story, daughter of Caesar’s late archenemy Cato.

Crucially, in the winter of 44 BC, Caesar’s opponents began calling on Brutus to uphold the tradition of his ancestors, who included the founder of the Roman Republic, Lucius Junius Brutus, the man who had led the expulsion of Rome’s kings hundreds of years earlier. And so, through a combination of pride, principle – and, perhaps, love for his wife – Brutus turned on Caesar.

A posse of senators stab Caesar to death in Vincenzo Camuccini’s painting, completed in c1798. The plot succeeded, says Barry Strauss, because it was planned with military precision: after isolating their victim, the assassins acted rapidly and ruthlessly. © Getty

Military precisionThe plot to assassinate Caesar succeeded because it was meticulously planned, and flawlessly executed. With generals such as Decimus, Cassius and Caesar’s veteran commander Trebonius involved, one would expect nothing less than military precision. The assassins chose to end Caesar’s life themselves rather than by hiring killers – a decision that showed their seriousness of purpose. And by striking at a Senate meeting they made it a public act rather than a private vendetta – an assassination and not a murder.

That this was a professional operation is even reflected in the killers’ choice of weapon. Caesar’s assassins attacked him with daggers and not, as is sometimes imagined, with swords. The latter were too big to sneak into the Senate House and too unwieldy for use in close quarters. In particular, the killers used a military dagger (the pugio), which was becoming standard issue for legionaries.

Military daggers were not only practical weapons but also honourable ones. Caesar’s supporters later called the assassins common criminals and accused them of using sicae, a short, curved blade that had the negative connotation of a switchblade or flick knife. So, in 44 BC, Brutus issued a coin that celebrated the Ides of March with two military daggers. Again, he wanted to show that the assassins were no mere murderers.

The Roman Senate House still stands in the Roman Forum and most visitors assume that Caesar was killed there – but he was not, nor on the Capitoline Hill, as Shakespeare states. The assassination took place about half a mile away from the Forum in Pompey’s Senate House, ironically built by Caesar’s great rival. It was part of a huge complex including a theatre, a park, a covered portico, and shops and offices. Gladiatorial games took place in the theatre on the Ides of March, which gave Decimus an excuse for deploying his gladiators near Pompey’s Senate House. Their real purpose was as a backup security force.

As a general, Caesar had a bodyguard but he made a point of dismissing it after returning to civilian life in Rome. He wanted to seem accessible and fearless. What’s more, only senators could enter a Senate meeting, so most of Caesar’s retinue would have had to remain outside the building. This made the dictator uniquely vulnerable inside the Senate House. Still, Caesar had appointed many of the senators personally, and they included military men. If they came to Caesar’s aid, they could overwhelm the assassins.

The assassins’ response to this threat was to attack at speed, isolating their target before striking. Even before Caesar took his seat on the tribunal, several assassins stood behind the chair while others surrounded him as if trying to grab his attention. The truth is that they were forming a perimeter.

Then the attack sprang into action. Tillius Cimber, a hard-drinking scrapper of a soldier whom Caesar favoured, held his hands out disrespectfully and pulled at Caesar’s toga. At this signal, his co-conspirators struck, led by Publius Servilius Casca.

Caesar immediately called out to Cimber, “Why, this is violence”, and hurled an oath at Casca, labelling him either “impious” or “accursed”. However, he never said: “Et tu, Brute?” (“You too, Brutus?”) – that phrase is a Renaissance invention. Ancient authors report a rumour that Caesar said to Brutus, in Greek: “You too, child.” But they doubt that he even said that.

Caesar, the old warrior, tried to fight back. He stabbed Casca with his stylus – a small, pointed, iron writing utensil – and managed to get back up. Two of his supporters among the senators, Lucius Marcius Censorinus and Gaius Calvisius Sabinus, then attempted to reach him but the conspirators blocked their way, and forced them to flee.

Meanwhile, Trebonius had been assigned to buttonhole his old comrade Mark Antony and engage him in conversation outside the Senate’s door. Antony was a veteran soldier, strong, dangerous and loyal to Caesar. If he’d entered the Senate room, he would have sat on the tribunal with Caesar and could have come to his aid.

With Mark Antony detained by Trebonius, there was little Caesar could do to defend himself. It probably took only minutes for him to die – succumbing to what most of the sources state were 23 wounds. Before the end, he wrapped his toga around his face and, in an ironic turn of events, fell at the foot of a statue of his rival, Pompey.

For all its brilliance, the plot to kill Caesar didn’t prove the panacea that the assassins hoped. Civil war soon broke out again and, to a man, they were to suffer violent deaths. What’s more, the Republic that they aimed to defend perished and gave way to an empire. That, however, does not brand them as foolish idealists. It merely shows that their political acumen did not match the military skill they displayed on the Ides of March.

In context: CaesarBy 44 BC Gaius Julius Caesar was the most famous and controversial man in Rome. A populist political star and great writer, he excelled in the military realm as well, pulling off a lightning conquest of Gaul – roughly, France and Belgium – as well as invading Britain and Germany (58–50 BC). When his enemies, the old guard in the Senate, removed him from command, Caesar invaded Italy. He went on to total victory in a civil war (49–45 BC) that ranged across the Mediterranean. His challenge now was to reconcile his surviving enemies and to convince staunch republicans to accept his power as dictator. It was a daunting task.

Barry Strauss (@barrystrauss) is a professor of history and classics at Cornell University.

Published on April 21, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Battle of Mutina:

April 21

43 BC Battle of Mutina: Mark Antony was again defeated in battle by Aulus Hirtius, who was killed. Antony failed to capture Mutina and Decimus Brutus was murdered shortly after.

43 BC Battle of Mutina: Mark Antony was again defeated in battle by Aulus Hirtius, who was killed. Antony failed to capture Mutina and Decimus Brutus was murdered shortly after.

Published on April 21, 2016 01:00

April 20, 2016

Impressive Mosaic and Large Roman Villa Discovered in UK… But it is Now Re-Buried

Ancient Origins

One of the largest Romans villas ever discovered in Britain and a beautiful mosaic, which was uncovered within in it, were found on a site known as Deverill Villa near Tisbury in Wiltshire, UK. It is one of the most important Roman discoveries in more than a decade.

According to The Telegraph, the villa had 20 to 25 rooms on the ground floor and was built sometime between 175 AD and 220 AD. It was repeatedly re-modeled right up until the mid- 4th century.

Exploration of the site at Deverill Villa revealed the surviving sections of walls measuring 1.5 meters (4.92 feet) in height. A mosaic formed a part of the grand villa, which is believed to have been three-storeys high, with grounds extending over 100 meters (328.08 feet) in width and length. It was accidentally discovered by Luke Irwin, a rug designer. He was installing electric cables in a barn in 2015 when he uncovered a mosaic near the foundations. It appeared to be in remarkably good condition, so Mr. Irwin called the Wiltshire Archaeology Service.

The Roman mosaic Mr. Irwin found in his backyard. (

Youtube/Luke Irwin Rugs

)The Roman villa was found under the backyard of Mr. Irwin’s 17th century house after an eight-day archaeological dig sponsored by Historic England and the local Salisbury Museum. Apart from the mosaic and ruined walls, the researchers from Salisbury discovered many precious artifacts, which may provide more information about life in the area during the 3rd century AD.

The Roman mosaic Mr. Irwin found in his backyard. (

Youtube/Luke Irwin Rugs

)The Roman villa was found under the backyard of Mr. Irwin’s 17th century house after an eight-day archaeological dig sponsored by Historic England and the local Salisbury Museum. Apart from the mosaic and ruined walls, the researchers from Salisbury discovered many precious artifacts, which may provide more information about life in the area during the 3rd century AD.

Ruins of luxurious imperial Roman villa to share its majesty once againAncient villa ruins found to be the estate of chariot-racer and Ben-Hur rivalDr. David Roberts, an archaeologist for Historic England, said:

The child’s stone coffin. (

News.com.au

)The recently discovered villa is very similar to another one that was found in 1864 at Chedworth, in Gloucestershire. That one was fully excavated, put on display and acquired by the National Trust in 1924. The Chedworth villa was built as a dwelling around the three sides of a country yard. It had a beautiful mosaic floor, and two separate bathing suites. Like the Deverill Villa, it also belonged to a wealthy and important family.

The child’s stone coffin. (

News.com.au

)The recently discovered villa is very similar to another one that was found in 1864 at Chedworth, in Gloucestershire. That one was fully excavated, put on display and acquired by the National Trust in 1924. The Chedworth villa was built as a dwelling around the three sides of a country yard. It had a beautiful mosaic floor, and two separate bathing suites. Like the Deverill Villa, it also belonged to a wealthy and important family.

Ancient Roman Elite Made Wine When not at War1,900-Year-Old Roman Village unearthed in GermanyThe researchers from Salisbury believe that it is possible the villa could have been a private property of at least one of the Roman Emperors. As Simon Sebag Montefiore, one of Britain’s leading historians said: "This remarkable Roman villa, with its baths and mosaics uncovered by chance, is a large, important and very exciting discovery that reveals so much about the luxurious lifestyle of a rich Romano British family at the height of the empire.''

Screenshot showting the Roman villa as rendered by a video artist, based on the discoveries made at the site. (

Youtube/Luke Irwin Rugs

)Unfortunately, the excavations could not be completed, because the cost of a full excavation and preservation of such a place would be too high. The researchers would like to go back and carry out more grids, but it would cost hundreds of thousands of pounds. The Salisbury Museum decided that until they find more money, the villa and its mosaic had to be re-buried and grassed over to protect them from the elements.

Screenshot showting the Roman villa as rendered by a video artist, based on the discoveries made at the site. (

Youtube/Luke Irwin Rugs

)Unfortunately, the excavations could not be completed, because the cost of a full excavation and preservation of such a place would be too high. The researchers would like to go back and carry out more grids, but it would cost hundreds of thousands of pounds. The Salisbury Museum decided that until they find more money, the villa and its mosaic had to be re-buried and grassed over to protect them from the elements.

However, even if it became financially possible to complete the dig, Mr. Irwin does not want his garden turned into a museum.

Well preserved Roman villas have been found in many of the former domains of the Roman Empire. In southern Europe, a number of them are now open-air museums. One of the most spectacular is located in Rabaçal, Portugal, 12 kilometers (7.46 miles) away from Conimbriga. The Roman housing complex was excavated in 1984. It was inhabited until around the 6th century AD, and currently it is used as a museum, which protects the remarkable set of mosaics that decorated the villa. The designs have African and Oriental influences, something unique in the art of this period in Portugal. They present seasons, quadriga mosaics, female figures, and vegetable and geometric compositions.

Featured Image: Excavations at the site of the Roman villa. Source: Youtube/Luke Irwin Rugs

By Natalia Klimczak

One of the largest Romans villas ever discovered in Britain and a beautiful mosaic, which was uncovered within in it, were found on a site known as Deverill Villa near Tisbury in Wiltshire, UK. It is one of the most important Roman discoveries in more than a decade.

According to The Telegraph, the villa had 20 to 25 rooms on the ground floor and was built sometime between 175 AD and 220 AD. It was repeatedly re-modeled right up until the mid- 4th century.

Exploration of the site at Deverill Villa revealed the surviving sections of walls measuring 1.5 meters (4.92 feet) in height. A mosaic formed a part of the grand villa, which is believed to have been three-storeys high, with grounds extending over 100 meters (328.08 feet) in width and length. It was accidentally discovered by Luke Irwin, a rug designer. He was installing electric cables in a barn in 2015 when he uncovered a mosaic near the foundations. It appeared to be in remarkably good condition, so Mr. Irwin called the Wiltshire Archaeology Service.

The Roman mosaic Mr. Irwin found in his backyard. (

Youtube/Luke Irwin Rugs

)The Roman villa was found under the backyard of Mr. Irwin’s 17th century house after an eight-day archaeological dig sponsored by Historic England and the local Salisbury Museum. Apart from the mosaic and ruined walls, the researchers from Salisbury discovered many precious artifacts, which may provide more information about life in the area during the 3rd century AD.

The Roman mosaic Mr. Irwin found in his backyard. (

Youtube/Luke Irwin Rugs

)The Roman villa was found under the backyard of Mr. Irwin’s 17th century house after an eight-day archaeological dig sponsored by Historic England and the local Salisbury Museum. Apart from the mosaic and ruined walls, the researchers from Salisbury discovered many precious artifacts, which may provide more information about life in the area during the 3rd century AD.Ruins of luxurious imperial Roman villa to share its majesty once againAncient villa ruins found to be the estate of chariot-racer and Ben-Hur rivalDr. David Roberts, an archaeologist for Historic England, said:

''This site has not been touched since its collapse 1400 years ago and, as such, is of enormous importance. Without question, this is a hugely valuable site in terms of research, with incredible potential. The discovery of such an elaborate and extraordinarily well-preserved villa, undamaged by agriculture for over 1500 years, is unparalleled in recent years. Overall, the excellent preservation, large scale and complexity of this site present a unique opportunity to understand Roman and post-Roman Britain.''The discovery also contained a perfectly preserved Roman well, underfloor heating pipes, and the stone coffin of a Roman child. The coffin had long been used by the inhabitants of the house as a flower pot. Oyster shells were also unearthed - which were transported over 45 miles (72.42 km) from the coast. This discovery confirms that the villa was a home of an important and wealthy family.

The child’s stone coffin. (

News.com.au

)The recently discovered villa is very similar to another one that was found in 1864 at Chedworth, in Gloucestershire. That one was fully excavated, put on display and acquired by the National Trust in 1924. The Chedworth villa was built as a dwelling around the three sides of a country yard. It had a beautiful mosaic floor, and two separate bathing suites. Like the Deverill Villa, it also belonged to a wealthy and important family.

The child’s stone coffin. (

News.com.au

)The recently discovered villa is very similar to another one that was found in 1864 at Chedworth, in Gloucestershire. That one was fully excavated, put on display and acquired by the National Trust in 1924. The Chedworth villa was built as a dwelling around the three sides of a country yard. It had a beautiful mosaic floor, and two separate bathing suites. Like the Deverill Villa, it also belonged to a wealthy and important family.Ancient Roman Elite Made Wine When not at War1,900-Year-Old Roman Village unearthed in GermanyThe researchers from Salisbury believe that it is possible the villa could have been a private property of at least one of the Roman Emperors. As Simon Sebag Montefiore, one of Britain’s leading historians said: "This remarkable Roman villa, with its baths and mosaics uncovered by chance, is a large, important and very exciting discovery that reveals so much about the luxurious lifestyle of a rich Romano British family at the height of the empire.''

Screenshot showting the Roman villa as rendered by a video artist, based on the discoveries made at the site. (

Youtube/Luke Irwin Rugs

)Unfortunately, the excavations could not be completed, because the cost of a full excavation and preservation of such a place would be too high. The researchers would like to go back and carry out more grids, but it would cost hundreds of thousands of pounds. The Salisbury Museum decided that until they find more money, the villa and its mosaic had to be re-buried and grassed over to protect them from the elements.

Screenshot showting the Roman villa as rendered by a video artist, based on the discoveries made at the site. (

Youtube/Luke Irwin Rugs

)Unfortunately, the excavations could not be completed, because the cost of a full excavation and preservation of such a place would be too high. The researchers would like to go back and carry out more grids, but it would cost hundreds of thousands of pounds. The Salisbury Museum decided that until they find more money, the villa and its mosaic had to be re-buried and grassed over to protect them from the elements.However, even if it became financially possible to complete the dig, Mr. Irwin does not want his garden turned into a museum.

Well preserved Roman villas have been found in many of the former domains of the Roman Empire. In southern Europe, a number of them are now open-air museums. One of the most spectacular is located in Rabaçal, Portugal, 12 kilometers (7.46 miles) away from Conimbriga. The Roman housing complex was excavated in 1984. It was inhabited until around the 6th century AD, and currently it is used as a museum, which protects the remarkable set of mosaics that decorated the villa. The designs have African and Oriental influences, something unique in the art of this period in Portugal. They present seasons, quadriga mosaics, female figures, and vegetable and geometric compositions.

Featured Image: Excavations at the site of the Roman villa. Source: Youtube/Luke Irwin Rugs

By Natalia Klimczak

Published on April 20, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Pope Clement V dies

April 20 1314

Clement V died. Clement, who owed his election largely to King Philip IV of France, chose to move the Papacy to Avignon, where it remained for more than 60 years. He also had a hand in the trial of the Templars.

Clement V died. Clement, who owed his election largely to King Philip IV of France, chose to move the Papacy to Avignon, where it remained for more than 60 years. He also had a hand in the trial of the Templars.

Published on April 20, 2016 01:00

April 19, 2016

Anglo-Saxon Cemetery Full of Grave Goods Discovered Near Prehistoric Henge Monuments

Ancient Origins

A site in England with burials dating from the mid-Anglo Saxon period of 660 to 780 AD and other ancient features is being excavated. Archaeologists also have found Bronze Age or Neolithic monuments nearby, though no evidence of houses.

The archaeologists also found military features from both world wars at the site in Bulford, Wiltshire, where 227 new homes for British Army families are to be built.

Archaeologists from Wessex Archaeology were called in to investigate the site before construction began in case there were valuable archaeological features on the site. A press release from Wessex Archaeology states:

One of the skeletons found at the cemetery. (

BBC

)The people were buried with personal items and grave goods giving indications of their social status, including jewelry of glass beads and brooches, knives, and cowrie shells from the Red Sea, which indicate far-reaching trade. One grave had a large comb made of antlers and decorated with dots, rings and chevrons.

One of the skeletons found at the cemetery. (

BBC

)The people were buried with personal items and grave goods giving indications of their social status, including jewelry of glass beads and brooches, knives, and cowrie shells from the Red Sea, which indicate far-reaching trade. One grave had a large comb made of antlers and decorated with dots, rings and chevrons.

Archaeologists also found a “work box” that may have served as an amulet meant to ward off evil. A scan of the small, cylindrical container showed it has traces of copper-alloy fragments. Other such boxes from the era had contained metal pins, thus they are called work boxes.

“This was a status symbol, and may have had amuletic as well as functional properties,” McKinley told Archaeology.co.uk. “This grave also contained what appears to be some kind of metal net bag, although we need to do more work on this to understand what it was.”

A workbox found in the grave of a woman. (Wessex Archaeology)Still another grave, the largest on the site, contained an unusually large spear whose haft had bronze decorations. The spear may have had symbolic or ritualistic meaning and belonged to a man who apparently was of special status in his community.

A workbox found in the grave of a woman. (Wessex Archaeology)Still another grave, the largest on the site, contained an unusually large spear whose haft had bronze decorations. The spear may have had symbolic or ritualistic meaning and belonged to a man who apparently was of special status in his community.

There is no settlement of habitations near the hilltop burial ground, but archaeologists are exploring the site as a ceremonial or sacred gathering place dating from the Neolithic. The people may have lived in a nearby river valley.

Workers Building Parishioners a Toilet Unearth a Mass Anglo-Saxon GraveMedieval Medicine: 1,000-year-old Onion and Garlic Salve Kills Modern Bacterial SuperBugsArchaeology.co.uk says excavations at the site uncovered clues as to why the Anglo-Saxon people buried their dead there, including two prehistoric “hengiform” monuments not far away. Preliminary dating puts these in the Neolithic or Bronze Age.

The article speculates that the early medieval occupants of the area were drawn by the enigmatic features of the barrows and monuments and buried the dead near them, as they did at other sites in Salisbury.

Neolithic ritual or ceremonial activity was found in large pits that contained unusual objects, including sherds of pottery, antler and wild ox bones, axes and ax fragments, carved pieces of chalk in the form of a bowl, and little ball and flint hammerstones. Archaeologists also found a rare discoidal knife of flint. Only two of these are known in the area around Stonehenge.

A decorated bone comb found during the excavation of a grave. (

Wessex Archaeology

)“What stands out is that there is very little domestic activity going on here,” Phil Harding, a Wessex Archaeology prehistory expert, told Archaeology.co.uk. “You don’t see much in the way of burning, or of flint-knapping debris. The pits’ contents seem more ritual/ceremonial in nature.”

A decorated bone comb found during the excavation of a grave. (

Wessex Archaeology

)“What stands out is that there is very little domestic activity going on here,” Phil Harding, a Wessex Archaeology prehistory expert, told Archaeology.co.uk. “You don’t see much in the way of burning, or of flint-knapping debris. The pits’ contents seem more ritual/ceremonial in nature.”

Featured Image: Saxon woman buried with her workbox and cowrie shell and a reconstruction what she may have looked like when she was buried. (Wessex Archaeology)

By Mark Miller

A site in England with burials dating from the mid-Anglo Saxon period of 660 to 780 AD and other ancient features is being excavated. Archaeologists also have found Bronze Age or Neolithic monuments nearby, though no evidence of houses.

The archaeologists also found military features from both world wars at the site in Bulford, Wiltshire, where 227 new homes for British Army families are to be built.

Archaeologists from Wessex Archaeology were called in to investigate the site before construction began in case there were valuable archaeological features on the site. A press release from Wessex Archaeology states:

“Further investigations revealed an Anglo-Saxon cemetery of about 150 graves, with grave goods including spears, knives, jewellery, bone combs and other personal items. One of the burials has been radiocarbon dated to between AD 660 and 780 which falls in the mid-Anglo-Saxon period in England.”The Headless Vikings of DorsetHigh status Anglo-Saxon burials in Suffolk, England, may be linked to ancient King of East AngliaArchaeology.co.uk reports that the 150 graves contain the remains of men, women, and children laid out close together in neat rows. Wessex Archaeology osteologist Jackie McKinley told Archaeology.co.uk she believes it was a planned cemetery with graves perhaps identified with markers or a low mound.

“A further phase of excavation is planned to examine the two adjacent prehistoric monuments beside which the Saxon cemetery was established. These appear to consist of Early Bronze Age round barrows that may have earlier, Neolithic origins. They are to be granted scheduled monument protection by Historic England and will be preserved in situ in a part of the site that will remain undeveloped. Neolithic pits outside the monuments contained decorated ‘Grooved Ware’ pottery, stone and flint axes, a finely made disc-shaped flint knife, a chalk bowl, and the bones of red deer, roe deer and aurochs (wild cattle).”

One of the skeletons found at the cemetery. (

BBC

)The people were buried with personal items and grave goods giving indications of their social status, including jewelry of glass beads and brooches, knives, and cowrie shells from the Red Sea, which indicate far-reaching trade. One grave had a large comb made of antlers and decorated with dots, rings and chevrons.

One of the skeletons found at the cemetery. (

BBC

)The people were buried with personal items and grave goods giving indications of their social status, including jewelry of glass beads and brooches, knives, and cowrie shells from the Red Sea, which indicate far-reaching trade. One grave had a large comb made of antlers and decorated with dots, rings and chevrons.Archaeologists also found a “work box” that may have served as an amulet meant to ward off evil. A scan of the small, cylindrical container showed it has traces of copper-alloy fragments. Other such boxes from the era had contained metal pins, thus they are called work boxes.

“This was a status symbol, and may have had amuletic as well as functional properties,” McKinley told Archaeology.co.uk. “This grave also contained what appears to be some kind of metal net bag, although we need to do more work on this to understand what it was.”

A workbox found in the grave of a woman. (Wessex Archaeology)Still another grave, the largest on the site, contained an unusually large spear whose haft had bronze decorations. The spear may have had symbolic or ritualistic meaning and belonged to a man who apparently was of special status in his community.

A workbox found in the grave of a woman. (Wessex Archaeology)Still another grave, the largest on the site, contained an unusually large spear whose haft had bronze decorations. The spear may have had symbolic or ritualistic meaning and belonged to a man who apparently was of special status in his community.There is no settlement of habitations near the hilltop burial ground, but archaeologists are exploring the site as a ceremonial or sacred gathering place dating from the Neolithic. The people may have lived in a nearby river valley.