MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 108

April 8, 2016

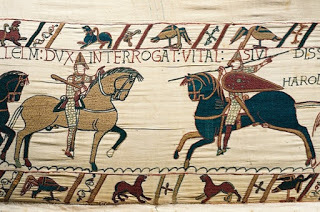

How England rode the Viking storm

History Extra

Alexander Dreymon plays Uhtred in The Last Kingdom. The drama – based on Bernard Cornwell’s Saxon novels – depicts Anglo-Saxons and their Viking ‘foes’ learning to co-operate. But was this scenario played out for real in ninth-century Wessex? © BBC

Alexander Dreymon plays Uhtred in The Last Kingdom. The drama – based on Bernard Cornwell’s Saxon novels – depicts Anglo-Saxons and their Viking ‘foes’ learning to co-operate. But was this scenario played out for real in ninth-century Wessex? © BBC

An early scene in the new BBC TV series The Last Kingdom sees the hero (or anti-hero) Uhtred, dispossessed claimant to the Northumbrian fortress of Bamburgh, entering the city of Winchester for the first time. Uhtred and his companion, both raised in a Danish household and in many ways more habituated to Danish customs than Anglo-Saxon ones, gain rapid access to the royal court of Alfred of Wessex. At the heart of the court, the pagan Uhtred is granted an audience with the Christian prince – and their discussions range from knowledge of the world to military strategies. From this, we get an insight into Alfred’s relationship with Uhtred, how each sees the other – and, crucially, how each intends to use the other.

Could such a scene have played out in ninth-century Winchester? Why was a prince of the West Saxons extending the hand of friendship to a pagan – a Dane, no less – at some point in the early 870s? The stereotypes dictate that a Danish Viking was too intent on pillaging to engage in any communication but violence. Received opinion also has it that the West Saxons were far too pious to accept Scandinavians as anything but the scourge of God, to be resisted by warriors and suffered by holy men.

Viking onslaughtIn many ways, the West Saxons’ attempts to defend their realm in the face of the Viking onslaught – particularly under Alfred ‘the Great’ in the final decades of the ninth century – is a story of conflict, of battles and stratagems, peace treaties made and broken, and of military leaders straining for victory in the direst of circumstances.

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Life of King Alfred – the West Saxons’ main courtly products telling the story of these years – that military leadership was provided by Alfred himself. But no matter whether Alfred can really be personally credited with the successes of the West Saxon kingdom in repelling the Viking threat, there is more to the story than conflict and the imposition of a West Saxon peace. Compromise, trust and understanding between the two peoples – as portrayed by the fictional Uhtred and Alfred in The Last Kingdom – was also at the heart of what it meant to be English in the 9th and early 10th centuries.

Where early medieval ‘Englishness’ was once regarded as binary – either you were English or you weren’t – and the West Saxons’ defence against the Vikings was seen as a part of the making of that Englishness, there is now room for a more nuanced story. The Vikings who came to England in the ninth century were woven into this story in a way that made them so much more than the pagan ‘other’.

That is not to say that Danes did not represent an existential threat to Anglo-Saxon rulers and their kingdoms, particularly Wessex. During the later part of the ninth century, the West Saxon kingdom was defined by its difference to the Danish-held territories – and the need to defend themselves against the Danish threat drove much of the West Saxons’ policy forward. The Danes launched numerous attacks on Wessex, and the kingdom itself was almost lost to at least one well-organised incursion.

From the introduction of military service to the building of ‘burhs’ (fortifications), the character of the West Saxon kingdom was determined by a Scandinavian threat outside it.

One of the terms that Christian writers most often employed to describe the pirates who exploded upon the western European scene in the late eighth and early ninth centuries was ‘Northmen’, a word that, while (mostly) being more geographically accurate, recalled the apocalyptic idea, trumpeted in the Book of Jeremiah, that evil would come from the north. To many religious writers, it must have seemed that these ‘Northmen’ indeed did herald the end-time. But by the late ninth century, we see fewer ‘Northmen’ in Anglo-Saxon sources, as the term gave way to ‘Dane’. And the reason for this may lie in the increasing representation of Vikings as people who you could do business with.

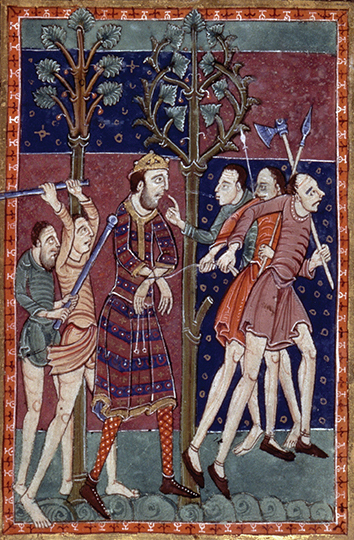

St Edmund is captured by Danes in a c1130 illumination. His death in 869 would go down in infamy yet, despite this, Vikings and Anglo-Saxons would learn to co-operate. © Topfoto

Danes and NorthmenIt seems that this was a meaningful distinction – and one that may have been reflected in the pages of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. While an early English text had labelled the instigators of an attack on Dorset in c789 as ‘Northmen’, a later account of the very same incident in the Chronicle refers to the aggressors as ‘Danes’. It was perhaps a telling editorial modification.

This important, if tentative, change in attitude was reflected in the growing number of peace agreements that the two sides signed in the late ninth century. The most important of these was the ‘Alfred-Guthrum’ treaty, sealed following Alfred’s 878 victory at the battle of Ethandun (Edington, Wiltshire) which shattered the Vikings’ ambition of conquering Wessex . The surviving document that records Alfred’s triumph probably represents a renegotiation of the territory between the two leaders.

In many ways, this treaty recognised how ‘Danes’ and ‘Englishmen’ were separated and subjected to different legal systems. However, the fact that both groups were subject to the same law – which was agreed by two sets of leaders, “confirmed with oaths, for themselves and for their subjects, both for the living and for the unborn” – created a sort of unified identity that had not before existed in the area that is now referred to as England.

That sense of peace was important. The Venerable Bede, the eighth-century Northumbrian author of a work long recognised as providing Alfred’s ‘blueprint’ for the idea of an Angelcynn (English realm), had reported that an early Anglo-Saxon king, Edwin, had provided the conditions in which a woman could travel with a newborn child from sea to sea without fear. Whether the conditions in late ninth-century England really allowed for such journeys is immaterial. Alfred’s allusion to those “unborn” might have been intended with Bede’s sense of peace in mind; a king who provided peace for an Angelcynn was one who recognised ‘Danes’ as potential subjects. There was precedent to be followed here, but it was not an English precedent. Instead it came from across the Channel, in the land of the Franks (roughly equivalent to modern-day France).

Historians have largely debunked the old myth of there being a great chasm between the dealings of the Western Franks and Alfred with the Vikings – the former traditionally damned as a failure; the latter hailed as a spectacular success. In fact, Frankish treaties with Vikings not only worked but also enhanced the standing of a number of rulers – these were not embarrassing episodes of compromise but moments to be celebrated. And they may have influenced Alfred – who had visited the court of Charles the Bald in West Francia as a young boy in the 850s – for he, too, was aware of the value of bringing Vikings into the Christian fold.

Although not particularly successful in the long term, the baptism by Charles the Bald’s father, Emperor Louis the Pious, of the Danish ruler Harald Klak in 826 had been a seminal event in the Carolingian court. Here we might trace the transformation from ‘Northmen’ to ‘Danes’, as Frankish authors took the event to their hearts as a means of depicting the imperial idea of Frankish kingship.

Around this time, Frankish writers started to take a serious interest in who ‘Danes’ were, and, given the Anglo-Saxons’ preoccupation with Frankish affairs, it is perhaps not surprising that this is echoed in England a generation or two later. Charles the Bald had been a young boy at the ceremony and it evidently had a major effect on him, just as Alfred’s visit to the Frankish court had an impact on the Anglo-Saxon ruler’s life.

Moment of triumphAn example of how a spirit of compromise had permeated Alfred’s Wessex is provided by the fact that Vikings were serving in the community of the Somerset monastery of Athelney, a site founded to celebrate Alfred’s great moment of triumph in 878. The famous biographer of Alfred’s life, Asser of St David’s, described them as “pagans” (pagani). Yet clearly they were not really pagans in the religious sense – they were, after all, part of a Christian community.

Around the same time, Alfred received the Scandinavian sea captain, Óttarr (Anglicised as Ohthere), at court. Óttarr is described in an Old English text as “most northern of the North-men”. Just as the fictional Uhtred comes to the West Saxon court in The Last Kingdom, this ninth-century view of Alfred has the king using Óttarr to discover more about the lands and peoples of Scandinavia. This provides further evidence that, though the Viking threat had by no means disappeared, these ‘North-men’ were very different from those who had perpetrated the apocalyptic attacks of a few decades earlier.

The lands they lived in were no longer mysterious. The understanding of them was more subtle, more complex, and far more human. Indeed, an object similar to the so-called ‘Alfred Jewel’, an artefact described by an Old English text as an æstel, has been found during excavations of a chieftain’s complex at Borg on the Lofoten Islands in northern Norway. Did Óttarr carry the ‘Borg Æstel’ back home after his stay at the West Saxon court? If so, it showed that a symbol of Alfred’s lordship – these objects were, after all, closely linked with Alfred’s court – had huge resonance in Scandinavia.

Óttarr was not an ‘Englishman’ but in some respects his relationship with “his lord Alfred” demonstrates that relationships between peoples were about more than just ties of blood and clearly-defined nationhood.

This remained the case well into the 10th century. For though the West Saxons’ expansion in the early 900s saw English Christians forcing Danes and other Vikings into submission through strongarm tactics, ‘Danes’ and ‘English’ continued to make agreements and negotiate over territory in a way that mirrored their predecessors’ diplomacy.

In fact, the descendants of ninth-century Scandinavian lords became the ‘men’ of English rulers – particularly Edward the Elder (899–924) and Æthelstan (924–39) – who allowed their new subjects to keep their lands in return for a submission to lordship.

So this was not purely a story of nationhood or of the triumph of one group over another. Instead, the Vikings’ role in the making of ‘England’ demonstrated that different peoples’ dealings with one another needed to be defined by flexibility as much as by factionalism and conflict.

“I became a historical helpline”

Being the historical advisor on The Last Kingdom meant working fast and remembering that the story comes first, says Ryan Lavelle...

I have been a fan of Bernard Cornwell’s books on early medieval England since my student days, so it was a great pleasure – and an honour – to work with Carnival Films on The Last Kingdom, their adaptation of his Saxon novels.

Cornwell often uses an outsider to tell a story, like his famous Napoleonic creation, the working-class British Army officer Sharpe. In The Last Kingdom, it is the Saxon Uhtred, whose Danish upbringing creates a conflict of identity that propels the storyline. It’s been fascinating to witness the production developing as the book’s first-person narrative and biographical storyline has had to pick up a pace for a series of TV episodes.

Alexander Dreymon and Emily Cox star as Uhtred and Brida in the “entertaining, interesting and thought-provoking” The Last Kingdom. © BBC

While I would love to take some credit for that, my own role meant leaving the storytelling to the experts, and simply being available to respond when needed to provide some costume advice, comment on scripts, and make occasional set visits. In many ways I became a historical helpline, getting questions like “tell us how a marriage would be arranged”, “what could happen at a coronation?”, “how should this name be spelt/pronounced in Old English?”

To answer such questions meant putting what I’ve learned about the early Middle Ages beyond rarefied academia into a ‘real’ world of creative imagination populated by such real historical characters as Alfred ‘the Great’ (not always a likeable fellow, it appears). I’ve had to avoid the historian’s temptation to respond to questions with a list of footnotes and caveats leading into a range of other possibilities based on the slimness of the surviving evidence. That sort of thing cuts no ice in a multi-million-pound production.

I quickly learned that, because what happens in one version of the script can change quickly – and change again a dozen times before it is shot – clear and concise answers are essential.

I have also had to keep reminding myself that The Last Kingdom is not a historical documentary series. The overriding principle has always been to drive the story forward, but I’ve constantly had to think: “Is this possible – does it work on screen?”

What the team came up with didn’t always match my interpretation of Anglo-Saxon history, but that usually needs footnotes! However, the production is a valid interpretation: it’s entertaining, interesting and, for me as a historian of the period, it’s thought-provoking. To that end, I couldn’t have asked for more.

Living in the shadow of the Vikings

From Cornish rebellions to puppet kings, our map shows how the Norsemen’s raids impacted on the kingdoms of Britain in the ninth century…

Strathclyde

A Welsh (‘British’) kingdom whose territory ranged across modern-day Scotland and Cumbria in north-western England, it was dealt a blow when Dumbarton Rock was besieged by Dublin Vikings in 870. With Govan (now in Glasgow) as its likely religious centre, Strathclyde still continued as a political force well into the 10th century.

Welsh kingdoms

A range of kings with a variety of extents of power and layers of lordship appears to have been the order in early Wales, with Gwynedd in the north-west coming to the fore. Although Rhodri Mawr (‘the Great’) suffered at Viking and English hands, probably killed by Mercians in 878, his successors asserted dominance over many of the neighbouring kingdoms, making alliances with Vikings and Anglo-Saxons according to circumstances.

Cornwall

Cornwall was coming under the West Saxons’ direct control in the ninth century. At least some Cornishmen resisted, including allying with Vikings in 838. The death of the last known Cornish king is recorded in a Welsh annal in 875 but the survival of Celtic place-names in Cornwall shows how the old kingdom never became a full part of the Anglo-Saxon world.

Alba

By the late ninth century, the areas controlled by kings of the Picts and Scots were beginning to be referred to as Alba, the Gaelic word for ‘Britain’, suggesting change was in the air. The kingdom of Alba was controlled by a line of rulers, of the house of Alpín, who emerged during the ninth-century upheaval of Viking attacks to assert domination over large swathes of territory which would form the core of a later Scottish kingdom.

Northumbria and the Kingdom of York

The kingdom of the Northumbrians had been created by the merging of the southern kingdom of Deira, focused on York, and the northern kingdom of Bernicia. Vikings controlled York from the 860s and settled soon after, while Bamburgh remained a seat of continuing Anglo-Saxon power in the north.

Mercia

Kings of Mercia had held overlordship over other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms during the eighth century, but remained a force to be reckoned with in the ninth. Years of hard campaigning led to the replacement of the Mercians’ king in 874 by a ruler who may have been a Viking ‘puppet’, then by Æthelred, an ealdorman (governor) likely to have been subordinate to King Alfred.

East Anglia

The last independent Anglo-Saxon king of the East Angles was killed by Vikings in 869 and is remembered as St Edmund. East Anglia became a Viking kingdom under the control of Guthrum, christened Æthelstan in 878. A decade of peace led to control by other Vikings after Guthrum’s death, but their coins bearing the name of St Edmund reveal how they ‘bought into’ Anglo-Saxon politics.

Wessex

Ruled by the descendants of Ecgberht, who had seized power at the start of the ninth century, the West Saxon kingdom controlled much of the south of England by the time of Alfred the Great (reigned 871–99), who managed to hold onto his throne in the face of Viking attacks.

Ryan Lavelle is reader in medieval history at the University of Winchester. He has co-edited Danes in Wessex (Oxbow), which is out later this year.

Alexander Dreymon plays Uhtred in The Last Kingdom. The drama – based on Bernard Cornwell’s Saxon novels – depicts Anglo-Saxons and their Viking ‘foes’ learning to co-operate. But was this scenario played out for real in ninth-century Wessex? © BBC

Alexander Dreymon plays Uhtred in The Last Kingdom. The drama – based on Bernard Cornwell’s Saxon novels – depicts Anglo-Saxons and their Viking ‘foes’ learning to co-operate. But was this scenario played out for real in ninth-century Wessex? © BBC An early scene in the new BBC TV series The Last Kingdom sees the hero (or anti-hero) Uhtred, dispossessed claimant to the Northumbrian fortress of Bamburgh, entering the city of Winchester for the first time. Uhtred and his companion, both raised in a Danish household and in many ways more habituated to Danish customs than Anglo-Saxon ones, gain rapid access to the royal court of Alfred of Wessex. At the heart of the court, the pagan Uhtred is granted an audience with the Christian prince – and their discussions range from knowledge of the world to military strategies. From this, we get an insight into Alfred’s relationship with Uhtred, how each sees the other – and, crucially, how each intends to use the other.

Could such a scene have played out in ninth-century Winchester? Why was a prince of the West Saxons extending the hand of friendship to a pagan – a Dane, no less – at some point in the early 870s? The stereotypes dictate that a Danish Viking was too intent on pillaging to engage in any communication but violence. Received opinion also has it that the West Saxons were far too pious to accept Scandinavians as anything but the scourge of God, to be resisted by warriors and suffered by holy men.

Viking onslaughtIn many ways, the West Saxons’ attempts to defend their realm in the face of the Viking onslaught – particularly under Alfred ‘the Great’ in the final decades of the ninth century – is a story of conflict, of battles and stratagems, peace treaties made and broken, and of military leaders straining for victory in the direst of circumstances.

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Life of King Alfred – the West Saxons’ main courtly products telling the story of these years – that military leadership was provided by Alfred himself. But no matter whether Alfred can really be personally credited with the successes of the West Saxon kingdom in repelling the Viking threat, there is more to the story than conflict and the imposition of a West Saxon peace. Compromise, trust and understanding between the two peoples – as portrayed by the fictional Uhtred and Alfred in The Last Kingdom – was also at the heart of what it meant to be English in the 9th and early 10th centuries.

Where early medieval ‘Englishness’ was once regarded as binary – either you were English or you weren’t – and the West Saxons’ defence against the Vikings was seen as a part of the making of that Englishness, there is now room for a more nuanced story. The Vikings who came to England in the ninth century were woven into this story in a way that made them so much more than the pagan ‘other’.

That is not to say that Danes did not represent an existential threat to Anglo-Saxon rulers and their kingdoms, particularly Wessex. During the later part of the ninth century, the West Saxon kingdom was defined by its difference to the Danish-held territories – and the need to defend themselves against the Danish threat drove much of the West Saxons’ policy forward. The Danes launched numerous attacks on Wessex, and the kingdom itself was almost lost to at least one well-organised incursion.

From the introduction of military service to the building of ‘burhs’ (fortifications), the character of the West Saxon kingdom was determined by a Scandinavian threat outside it.

One of the terms that Christian writers most often employed to describe the pirates who exploded upon the western European scene in the late eighth and early ninth centuries was ‘Northmen’, a word that, while (mostly) being more geographically accurate, recalled the apocalyptic idea, trumpeted in the Book of Jeremiah, that evil would come from the north. To many religious writers, it must have seemed that these ‘Northmen’ indeed did herald the end-time. But by the late ninth century, we see fewer ‘Northmen’ in Anglo-Saxon sources, as the term gave way to ‘Dane’. And the reason for this may lie in the increasing representation of Vikings as people who you could do business with.

St Edmund is captured by Danes in a c1130 illumination. His death in 869 would go down in infamy yet, despite this, Vikings and Anglo-Saxons would learn to co-operate. © Topfoto

Danes and NorthmenIt seems that this was a meaningful distinction – and one that may have been reflected in the pages of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. While an early English text had labelled the instigators of an attack on Dorset in c789 as ‘Northmen’, a later account of the very same incident in the Chronicle refers to the aggressors as ‘Danes’. It was perhaps a telling editorial modification.

This important, if tentative, change in attitude was reflected in the growing number of peace agreements that the two sides signed in the late ninth century. The most important of these was the ‘Alfred-Guthrum’ treaty, sealed following Alfred’s 878 victory at the battle of Ethandun (Edington, Wiltshire) which shattered the Vikings’ ambition of conquering Wessex . The surviving document that records Alfred’s triumph probably represents a renegotiation of the territory between the two leaders.

In many ways, this treaty recognised how ‘Danes’ and ‘Englishmen’ were separated and subjected to different legal systems. However, the fact that both groups were subject to the same law – which was agreed by two sets of leaders, “confirmed with oaths, for themselves and for their subjects, both for the living and for the unborn” – created a sort of unified identity that had not before existed in the area that is now referred to as England.

That sense of peace was important. The Venerable Bede, the eighth-century Northumbrian author of a work long recognised as providing Alfred’s ‘blueprint’ for the idea of an Angelcynn (English realm), had reported that an early Anglo-Saxon king, Edwin, had provided the conditions in which a woman could travel with a newborn child from sea to sea without fear. Whether the conditions in late ninth-century England really allowed for such journeys is immaterial. Alfred’s allusion to those “unborn” might have been intended with Bede’s sense of peace in mind; a king who provided peace for an Angelcynn was one who recognised ‘Danes’ as potential subjects. There was precedent to be followed here, but it was not an English precedent. Instead it came from across the Channel, in the land of the Franks (roughly equivalent to modern-day France).

Historians have largely debunked the old myth of there being a great chasm between the dealings of the Western Franks and Alfred with the Vikings – the former traditionally damned as a failure; the latter hailed as a spectacular success. In fact, Frankish treaties with Vikings not only worked but also enhanced the standing of a number of rulers – these were not embarrassing episodes of compromise but moments to be celebrated. And they may have influenced Alfred – who had visited the court of Charles the Bald in West Francia as a young boy in the 850s – for he, too, was aware of the value of bringing Vikings into the Christian fold.

Although not particularly successful in the long term, the baptism by Charles the Bald’s father, Emperor Louis the Pious, of the Danish ruler Harald Klak in 826 had been a seminal event in the Carolingian court. Here we might trace the transformation from ‘Northmen’ to ‘Danes’, as Frankish authors took the event to their hearts as a means of depicting the imperial idea of Frankish kingship.

Around this time, Frankish writers started to take a serious interest in who ‘Danes’ were, and, given the Anglo-Saxons’ preoccupation with Frankish affairs, it is perhaps not surprising that this is echoed in England a generation or two later. Charles the Bald had been a young boy at the ceremony and it evidently had a major effect on him, just as Alfred’s visit to the Frankish court had an impact on the Anglo-Saxon ruler’s life.

Moment of triumphAn example of how a spirit of compromise had permeated Alfred’s Wessex is provided by the fact that Vikings were serving in the community of the Somerset monastery of Athelney, a site founded to celebrate Alfred’s great moment of triumph in 878. The famous biographer of Alfred’s life, Asser of St David’s, described them as “pagans” (pagani). Yet clearly they were not really pagans in the religious sense – they were, after all, part of a Christian community.

Around the same time, Alfred received the Scandinavian sea captain, Óttarr (Anglicised as Ohthere), at court. Óttarr is described in an Old English text as “most northern of the North-men”. Just as the fictional Uhtred comes to the West Saxon court in The Last Kingdom, this ninth-century view of Alfred has the king using Óttarr to discover more about the lands and peoples of Scandinavia. This provides further evidence that, though the Viking threat had by no means disappeared, these ‘North-men’ were very different from those who had perpetrated the apocalyptic attacks of a few decades earlier.

The lands they lived in were no longer mysterious. The understanding of them was more subtle, more complex, and far more human. Indeed, an object similar to the so-called ‘Alfred Jewel’, an artefact described by an Old English text as an æstel, has been found during excavations of a chieftain’s complex at Borg on the Lofoten Islands in northern Norway. Did Óttarr carry the ‘Borg Æstel’ back home after his stay at the West Saxon court? If so, it showed that a symbol of Alfred’s lordship – these objects were, after all, closely linked with Alfred’s court – had huge resonance in Scandinavia.

Óttarr was not an ‘Englishman’ but in some respects his relationship with “his lord Alfred” demonstrates that relationships between peoples were about more than just ties of blood and clearly-defined nationhood.

This remained the case well into the 10th century. For though the West Saxons’ expansion in the early 900s saw English Christians forcing Danes and other Vikings into submission through strongarm tactics, ‘Danes’ and ‘English’ continued to make agreements and negotiate over territory in a way that mirrored their predecessors’ diplomacy.

In fact, the descendants of ninth-century Scandinavian lords became the ‘men’ of English rulers – particularly Edward the Elder (899–924) and Æthelstan (924–39) – who allowed their new subjects to keep their lands in return for a submission to lordship.

So this was not purely a story of nationhood or of the triumph of one group over another. Instead, the Vikings’ role in the making of ‘England’ demonstrated that different peoples’ dealings with one another needed to be defined by flexibility as much as by factionalism and conflict.

“I became a historical helpline”

Being the historical advisor on The Last Kingdom meant working fast and remembering that the story comes first, says Ryan Lavelle...

I have been a fan of Bernard Cornwell’s books on early medieval England since my student days, so it was a great pleasure – and an honour – to work with Carnival Films on The Last Kingdom, their adaptation of his Saxon novels.

Cornwell often uses an outsider to tell a story, like his famous Napoleonic creation, the working-class British Army officer Sharpe. In The Last Kingdom, it is the Saxon Uhtred, whose Danish upbringing creates a conflict of identity that propels the storyline. It’s been fascinating to witness the production developing as the book’s first-person narrative and biographical storyline has had to pick up a pace for a series of TV episodes.

Alexander Dreymon and Emily Cox star as Uhtred and Brida in the “entertaining, interesting and thought-provoking” The Last Kingdom. © BBC

While I would love to take some credit for that, my own role meant leaving the storytelling to the experts, and simply being available to respond when needed to provide some costume advice, comment on scripts, and make occasional set visits. In many ways I became a historical helpline, getting questions like “tell us how a marriage would be arranged”, “what could happen at a coronation?”, “how should this name be spelt/pronounced in Old English?”

To answer such questions meant putting what I’ve learned about the early Middle Ages beyond rarefied academia into a ‘real’ world of creative imagination populated by such real historical characters as Alfred ‘the Great’ (not always a likeable fellow, it appears). I’ve had to avoid the historian’s temptation to respond to questions with a list of footnotes and caveats leading into a range of other possibilities based on the slimness of the surviving evidence. That sort of thing cuts no ice in a multi-million-pound production.

I quickly learned that, because what happens in one version of the script can change quickly – and change again a dozen times before it is shot – clear and concise answers are essential.

I have also had to keep reminding myself that The Last Kingdom is not a historical documentary series. The overriding principle has always been to drive the story forward, but I’ve constantly had to think: “Is this possible – does it work on screen?”

What the team came up with didn’t always match my interpretation of Anglo-Saxon history, but that usually needs footnotes! However, the production is a valid interpretation: it’s entertaining, interesting and, for me as a historian of the period, it’s thought-provoking. To that end, I couldn’t have asked for more.

Living in the shadow of the Vikings

From Cornish rebellions to puppet kings, our map shows how the Norsemen’s raids impacted on the kingdoms of Britain in the ninth century…

Strathclyde

A Welsh (‘British’) kingdom whose territory ranged across modern-day Scotland and Cumbria in north-western England, it was dealt a blow when Dumbarton Rock was besieged by Dublin Vikings in 870. With Govan (now in Glasgow) as its likely religious centre, Strathclyde still continued as a political force well into the 10th century.

Welsh kingdoms

A range of kings with a variety of extents of power and layers of lordship appears to have been the order in early Wales, with Gwynedd in the north-west coming to the fore. Although Rhodri Mawr (‘the Great’) suffered at Viking and English hands, probably killed by Mercians in 878, his successors asserted dominance over many of the neighbouring kingdoms, making alliances with Vikings and Anglo-Saxons according to circumstances.

Cornwall

Cornwall was coming under the West Saxons’ direct control in the ninth century. At least some Cornishmen resisted, including allying with Vikings in 838. The death of the last known Cornish king is recorded in a Welsh annal in 875 but the survival of Celtic place-names in Cornwall shows how the old kingdom never became a full part of the Anglo-Saxon world.

Alba

By the late ninth century, the areas controlled by kings of the Picts and Scots were beginning to be referred to as Alba, the Gaelic word for ‘Britain’, suggesting change was in the air. The kingdom of Alba was controlled by a line of rulers, of the house of Alpín, who emerged during the ninth-century upheaval of Viking attacks to assert domination over large swathes of territory which would form the core of a later Scottish kingdom.

Northumbria and the Kingdom of York

The kingdom of the Northumbrians had been created by the merging of the southern kingdom of Deira, focused on York, and the northern kingdom of Bernicia. Vikings controlled York from the 860s and settled soon after, while Bamburgh remained a seat of continuing Anglo-Saxon power in the north.

Mercia

Kings of Mercia had held overlordship over other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms during the eighth century, but remained a force to be reckoned with in the ninth. Years of hard campaigning led to the replacement of the Mercians’ king in 874 by a ruler who may have been a Viking ‘puppet’, then by Æthelred, an ealdorman (governor) likely to have been subordinate to King Alfred.

East Anglia

The last independent Anglo-Saxon king of the East Angles was killed by Vikings in 869 and is remembered as St Edmund. East Anglia became a Viking kingdom under the control of Guthrum, christened Æthelstan in 878. A decade of peace led to control by other Vikings after Guthrum’s death, but their coins bearing the name of St Edmund reveal how they ‘bought into’ Anglo-Saxon politics.

Wessex

Ruled by the descendants of Ecgberht, who had seized power at the start of the ninth century, the West Saxon kingdom controlled much of the south of England by the time of Alfred the Great (reigned 871–99), who managed to hold onto his throne in the face of Viking attacks.

Ryan Lavelle is reader in medieval history at the University of Winchester. He has co-edited Danes in Wessex (Oxbow), which is out later this year.

Published on April 08, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Charles V crowned King of France

April 8

1364 Charles V crowned King of France. He led France in recovery from the devastation of the first part of the Hundred Years' War.

1364 Charles V crowned King of France. He led France in recovery from the devastation of the first part of the Hundred Years' War.

Published on April 08, 2016 02:00

April 7, 2016

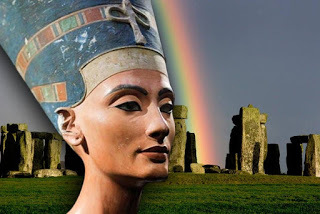

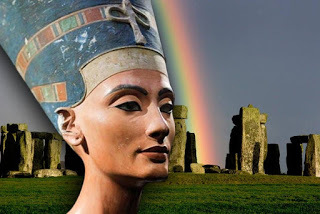

From Stonehenge to Nefertiti: How High-Tech Archaeology is transforming our view of History

Ancient Origins

A recent discovery could radically change our views of one of the world’s most famous archaeological sites, Tutankhamun’s tomb. Scans of the complex in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings revealed it may still include undiscovered chambers – perhaps even the resting place of Queen Nefertiti – even though we have been studying the tomb for almost 100 years.

A recent discovery could radically change our views of one of the world’s most famous archaeological sites, Tutankhamun’s tomb. Scans of the complex in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings revealed it may still include undiscovered chambers – perhaps even the resting place of Queen Nefertiti – even though we have been studying the tomb for almost 100 years.

It’s common to get excited about high-profile archaeological discoveries, but it’s the slower, ongoing research that shows the real potential of new technology to change our understanding of history.

The latest findings touch on the mystery and conjecture around the tomb of the Egyptian queen consort Nefertiti, who died around 1330 BC. Some scholars believe that she was buried in a chamber in her stepson Tutankhamun’s tomb (known as KV62), although others have urged caution over this hypothesis.

Screenshot from a Factum Arte scan of King Tutankhamun's burial chamber, behind which, a researcher says, may lie the tomb of Queen Nefertiti. (

Factum-arte.org scan

)Nefertiti is a pivotal figure in Egyptology. She and her husband Pharaoh Akhenaten helped bring about a religious revolution in ancient Egypt, and she may have even briefly ruled the country after his death. But we have little solid information about her life or death and her remains have never been found.

Screenshot from a Factum Arte scan of King Tutankhamun's burial chamber, behind which, a researcher says, may lie the tomb of Queen Nefertiti. (

Factum-arte.org scan

)Nefertiti is a pivotal figure in Egyptology. She and her husband Pharaoh Akhenaten helped bring about a religious revolution in ancient Egypt, and she may have even briefly ruled the country after his death. But we have little solid information about her life or death and her remains have never been found.

The Elusive Tomb of Queen Nefertiti may lie behind the walls of Tutankhamun's Burial ChamberThe Search Continues: Scientists to Use Radar in Hunt for the Tomb of NefertitiSpanish Leak Reveals Hidden Chamber in Tutankhamun Tomb is Full of TreasuresSo the discovery of her tomb could be instrumental in revealing more about this critical period in history, and even change our views on how powerful and important she was. Nicholas Reeves, the director of the research, believes that the size and layout of KV62 means that it may have originally been designed for a queen. He has also used a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey to look for possible hidden antechambers that may contain Nefertiti’s remains after reassessment of the relationship between Nefertiti and Tutankhamun led to renewed interest in the tomb.

Ground penetrating radar. University of Southampton, Author providedUnderground archaeologyThe geophysical survey techniques used to study the tomb have been applied in archaeology since the 1970s. GPR involves emitting electromagnetic radar waves through a structure and measuring how long it takes for them to be reflected by the different objects and elements that comprise it. Different materials reflect the radar waves at different velocity so it’s possible to use this information to build a 3D map of the structure. For KV62, the map suggests there are spaces beyond the standing walls of the tomb, which could be undiscovered antechambers.

Ground penetrating radar. University of Southampton, Author providedUnderground archaeologyThe geophysical survey techniques used to study the tomb have been applied in archaeology since the 1970s. GPR involves emitting electromagnetic radar waves through a structure and measuring how long it takes for them to be reflected by the different objects and elements that comprise it. Different materials reflect the radar waves at different velocity so it’s possible to use this information to build a 3D map of the structure. For KV62, the map suggests there are spaces beyond the standing walls of the tomb, which could be undiscovered antechambers.

The problem with such surveys is that the high hopes of the initial conclusions released to the public may not match the reality of later findings. The data can often be interpreted in different ways. For example, natural breaks and fissures in the rock may produce responses similar to undiscovered chambers. Scanning the relatively small area of the walls of an individual chamber can make it difficult to place the results in a broader context.

By gathering a wider range of data, we can slowly build up a clearer picture of the history of a site. While not as dramatic as uncovering a forgotten tomb, the process of using technology to gradually study a site can, directly and indirectly, significantly change our view of it or the people associated with it.

Other geophysical techniques tend to be used to study more open sites or landscapes. Magnetometry measures the variations in the Earth’s magnetic field that are caused by many forms of buried archaeological material, from fired material such as kilns to building material and filled ditches. Earth resistance measures how easily electrical current passes through the ground. Features such as walls, paving and rubble have a high resistance to current, while filled ditches and pits tend to have a low resistance.

Hidden landscape. Stonehenge Hidden Landscape Project LBIArchPROUncovering the real StonehengePutting such techniques to use at Stonehenge, for example, has completely transformed the way we think about how the landscape was used, and the forms of worship used by Neolithic society. Prior to the survey only a handful of ritual monuments were known around the impressive remains of Stonehenge, meaning that archaeologists could not easily evaluate the way in which the landscape was used.

Hidden landscape. Stonehenge Hidden Landscape Project LBIArchPROUncovering the real StonehengePutting such techniques to use at Stonehenge, for example, has completely transformed the way we think about how the landscape was used, and the forms of worship used by Neolithic society. Prior to the survey only a handful of ritual monuments were known around the impressive remains of Stonehenge, meaning that archaeologists could not easily evaluate the way in which the landscape was used.

The geophysical survey revealed hundreds of archaeological features, including 17 major ritual monuments. For the first time archaeologists were able to map every single possible buried monument in the landscape, including henges, pits, barrows and ditches. This means we can start to fully appreciate the way in which the ritual landscape was organised. For example, the new monuments reveal astronomical alignments that were previously unknown or only partly recognised.

Architect presents radical new theory that Stonehenge was a two-storey, wooden feasting and performance hallResearch Decodes Ancient Celtic Astronomy Symbols and Links them to Jungian ArchetypesResearchers Say Stonehenge had More Gender Equality than Commonly BelievedSimilar geophysical survey work at Ostia Antica in Italy has completely altered our theories about the layout of the city and its harbour. A magnetometer survey conducted across the area between Portus and Ostia between 2008 and 2011, discovered the presence of buried warehouses and associated structures. These were enclosed by the line of a defensive wall, showing that the extent of the ancient city included both banks of the river Tiber. This crucial fact changes the potential size of the city and alters our plan of its harbour area. This suggests much more of the city was used for storage, perhaps making it even more important as a port for nearby Rome than previously thought.

Sarum revealed. University of Southampton, Author providedAn ongoing survey at Old Sarum in Wiltshire in the UK has been studying the area surrounding the remains of the Iron-age hillfort and medieval town. Using GPR, magnetometry and earth resistance together has uncovered an unprecedented number of Roman and medieval structures, courtyards and other remains. This indicates that there was a much more substantial and complex settlement at Old Sarum much earlier than previously thought. Further work in 2016 may even prove claims of a late Saxon settlement and mint at the site.

Sarum revealed. University of Southampton, Author providedAn ongoing survey at Old Sarum in Wiltshire in the UK has been studying the area surrounding the remains of the Iron-age hillfort and medieval town. Using GPR, magnetometry and earth resistance together has uncovered an unprecedented number of Roman and medieval structures, courtyards and other remains. This indicates that there was a much more substantial and complex settlement at Old Sarum much earlier than previously thought. Further work in 2016 may even prove claims of a late Saxon settlement and mint at the site.

These kinds of discoveries show that geophysical technology has a huge role to play in archaeology, both through investigation of sites and landscapes, and also of smaller monuments such as buildings and tombs. But we need to look beyond the more sensational aspects of such research and understand the role it plays in the bigger picture of uncovering the past.

Featured image: The iconic bust of Nefertiti, discovered by Ludwig Borchardt, is part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection, currently on display in the Altes Museum. ( The Red List ), Stonehenge with a rainbow. ( CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 )

The article ‘ From Stonehenge to Nefertiti: how high-tech archaeology is transforming our view of history ’ by Kristian Strutt was originally published on The Conversation and has republished under a Creative Commons license.

A recent discovery could radically change our views of one of the world’s most famous archaeological sites, Tutankhamun’s tomb. Scans of the complex in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings revealed it may still include undiscovered chambers – perhaps even the resting place of Queen Nefertiti – even though we have been studying the tomb for almost 100 years.

A recent discovery could radically change our views of one of the world’s most famous archaeological sites, Tutankhamun’s tomb. Scans of the complex in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings revealed it may still include undiscovered chambers – perhaps even the resting place of Queen Nefertiti – even though we have been studying the tomb for almost 100 years.It’s common to get excited about high-profile archaeological discoveries, but it’s the slower, ongoing research that shows the real potential of new technology to change our understanding of history.

The latest findings touch on the mystery and conjecture around the tomb of the Egyptian queen consort Nefertiti, who died around 1330 BC. Some scholars believe that she was buried in a chamber in her stepson Tutankhamun’s tomb (known as KV62), although others have urged caution over this hypothesis.

Screenshot from a Factum Arte scan of King Tutankhamun's burial chamber, behind which, a researcher says, may lie the tomb of Queen Nefertiti. (

Factum-arte.org scan

)Nefertiti is a pivotal figure in Egyptology. She and her husband Pharaoh Akhenaten helped bring about a religious revolution in ancient Egypt, and she may have even briefly ruled the country after his death. But we have little solid information about her life or death and her remains have never been found.

Screenshot from a Factum Arte scan of King Tutankhamun's burial chamber, behind which, a researcher says, may lie the tomb of Queen Nefertiti. (

Factum-arte.org scan

)Nefertiti is a pivotal figure in Egyptology. She and her husband Pharaoh Akhenaten helped bring about a religious revolution in ancient Egypt, and she may have even briefly ruled the country after his death. But we have little solid information about her life or death and her remains have never been found.The Elusive Tomb of Queen Nefertiti may lie behind the walls of Tutankhamun's Burial ChamberThe Search Continues: Scientists to Use Radar in Hunt for the Tomb of NefertitiSpanish Leak Reveals Hidden Chamber in Tutankhamun Tomb is Full of TreasuresSo the discovery of her tomb could be instrumental in revealing more about this critical period in history, and even change our views on how powerful and important she was. Nicholas Reeves, the director of the research, believes that the size and layout of KV62 means that it may have originally been designed for a queen. He has also used a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey to look for possible hidden antechambers that may contain Nefertiti’s remains after reassessment of the relationship between Nefertiti and Tutankhamun led to renewed interest in the tomb.

Ground penetrating radar. University of Southampton, Author providedUnderground archaeologyThe geophysical survey techniques used to study the tomb have been applied in archaeology since the 1970s. GPR involves emitting electromagnetic radar waves through a structure and measuring how long it takes for them to be reflected by the different objects and elements that comprise it. Different materials reflect the radar waves at different velocity so it’s possible to use this information to build a 3D map of the structure. For KV62, the map suggests there are spaces beyond the standing walls of the tomb, which could be undiscovered antechambers.

Ground penetrating radar. University of Southampton, Author providedUnderground archaeologyThe geophysical survey techniques used to study the tomb have been applied in archaeology since the 1970s. GPR involves emitting electromagnetic radar waves through a structure and measuring how long it takes for them to be reflected by the different objects and elements that comprise it. Different materials reflect the radar waves at different velocity so it’s possible to use this information to build a 3D map of the structure. For KV62, the map suggests there are spaces beyond the standing walls of the tomb, which could be undiscovered antechambers.The problem with such surveys is that the high hopes of the initial conclusions released to the public may not match the reality of later findings. The data can often be interpreted in different ways. For example, natural breaks and fissures in the rock may produce responses similar to undiscovered chambers. Scanning the relatively small area of the walls of an individual chamber can make it difficult to place the results in a broader context.

By gathering a wider range of data, we can slowly build up a clearer picture of the history of a site. While not as dramatic as uncovering a forgotten tomb, the process of using technology to gradually study a site can, directly and indirectly, significantly change our view of it or the people associated with it.

Other geophysical techniques tend to be used to study more open sites or landscapes. Magnetometry measures the variations in the Earth’s magnetic field that are caused by many forms of buried archaeological material, from fired material such as kilns to building material and filled ditches. Earth resistance measures how easily electrical current passes through the ground. Features such as walls, paving and rubble have a high resistance to current, while filled ditches and pits tend to have a low resistance.

Hidden landscape. Stonehenge Hidden Landscape Project LBIArchPROUncovering the real StonehengePutting such techniques to use at Stonehenge, for example, has completely transformed the way we think about how the landscape was used, and the forms of worship used by Neolithic society. Prior to the survey only a handful of ritual monuments were known around the impressive remains of Stonehenge, meaning that archaeologists could not easily evaluate the way in which the landscape was used.

Hidden landscape. Stonehenge Hidden Landscape Project LBIArchPROUncovering the real StonehengePutting such techniques to use at Stonehenge, for example, has completely transformed the way we think about how the landscape was used, and the forms of worship used by Neolithic society. Prior to the survey only a handful of ritual monuments were known around the impressive remains of Stonehenge, meaning that archaeologists could not easily evaluate the way in which the landscape was used.The geophysical survey revealed hundreds of archaeological features, including 17 major ritual monuments. For the first time archaeologists were able to map every single possible buried monument in the landscape, including henges, pits, barrows and ditches. This means we can start to fully appreciate the way in which the ritual landscape was organised. For example, the new monuments reveal astronomical alignments that were previously unknown or only partly recognised.

Architect presents radical new theory that Stonehenge was a two-storey, wooden feasting and performance hallResearch Decodes Ancient Celtic Astronomy Symbols and Links them to Jungian ArchetypesResearchers Say Stonehenge had More Gender Equality than Commonly BelievedSimilar geophysical survey work at Ostia Antica in Italy has completely altered our theories about the layout of the city and its harbour. A magnetometer survey conducted across the area between Portus and Ostia between 2008 and 2011, discovered the presence of buried warehouses and associated structures. These were enclosed by the line of a defensive wall, showing that the extent of the ancient city included both banks of the river Tiber. This crucial fact changes the potential size of the city and alters our plan of its harbour area. This suggests much more of the city was used for storage, perhaps making it even more important as a port for nearby Rome than previously thought.

Sarum revealed. University of Southampton, Author providedAn ongoing survey at Old Sarum in Wiltshire in the UK has been studying the area surrounding the remains of the Iron-age hillfort and medieval town. Using GPR, magnetometry and earth resistance together has uncovered an unprecedented number of Roman and medieval structures, courtyards and other remains. This indicates that there was a much more substantial and complex settlement at Old Sarum much earlier than previously thought. Further work in 2016 may even prove claims of a late Saxon settlement and mint at the site.

Sarum revealed. University of Southampton, Author providedAn ongoing survey at Old Sarum in Wiltshire in the UK has been studying the area surrounding the remains of the Iron-age hillfort and medieval town. Using GPR, magnetometry and earth resistance together has uncovered an unprecedented number of Roman and medieval structures, courtyards and other remains. This indicates that there was a much more substantial and complex settlement at Old Sarum much earlier than previously thought. Further work in 2016 may even prove claims of a late Saxon settlement and mint at the site.These kinds of discoveries show that geophysical technology has a huge role to play in archaeology, both through investigation of sites and landscapes, and also of smaller monuments such as buildings and tombs. But we need to look beyond the more sensational aspects of such research and understand the role it plays in the bigger picture of uncovering the past.

Featured image: The iconic bust of Nefertiti, discovered by Ludwig Borchardt, is part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection, currently on display in the Altes Museum. ( The Red List ), Stonehenge with a rainbow. ( CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 )

The article ‘ From Stonehenge to Nefertiti: how high-tech archaeology is transforming our view of history ’ by Kristian Strutt was originally published on The Conversation and has republished under a Creative Commons license.

Published on April 07, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - birth of St. Francis Xavier

April 7

1506 St. Francis Xavier was born. A passionate missionary of Catholicism, Francis was instrumental in establishing Christianity in India and Japan. He was also one of the earliest members of the Society of Jesus.

1506 St. Francis Xavier was born. A passionate missionary of Catholicism, Francis was instrumental in establishing Christianity in India and Japan. He was also one of the earliest members of the Society of Jesus.

Published on April 07, 2016 01:30

April 6, 2016

Treasures Found Within Very Valuable Viking Hoard Finally Revealed -

Ancient Origins

Around the time the Irish were stamping out the Viking presence in their country, local lore says the Scots and Vikings also fought a battle near Galloway, Scotland. In 2014, a metal detectorist took that legend, swept the area, and discovered a hoard of 100 “strange and wonderful objects” that were about 1,000 years old.

Around the time the Irish were stamping out the Viking presence in their country, local lore says the Scots and Vikings also fought a battle near Galloway, Scotland. In 2014, a metal detectorist took that legend, swept the area, and discovered a hoard of 100 “strange and wonderful objects” that were about 1,000 years old.

[image error]No one knows how the person who buried the hoard came across the spectacular stuff or why it was buried. One can only speculate that perhaps there was a battle, and perhaps the items were buried beforehand or during the course of it in case the one who hid the hoard had to flee.

Conservators are just now releasing images of the Galloway hoard, showing items found in a Carolingian vessel or pot. The pot itself, from Western Europe, is very rare and is one of only six of the type ever found.

The Carolingian vessel. (

Historic Environment Scotland

) “The hoard is the most important Viking discovery in Scotland for over 100 years. The items from within the vessel, which may have been accumulated over a number of generations, reveal objects from across Europe and from other cultures with non-Viking origins,” says a press release from Historic Scotland.

The Carolingian vessel. (

Historic Environment Scotland

) “The hoard is the most important Viking discovery in Scotland for over 100 years. The items from within the vessel, which may have been accumulated over a number of generations, reveal objects from across Europe and from other cultures with non-Viking origins,” says a press release from Historic Scotland.

Massive Viking Hoard Unearthed by Treasure Hunter Publicly Revealed for First TimeTreasure hunter uncovers one of the most significant Viking hoards ever found in ScotlandThe Oseberg Ship Burial Astounded Archaeologists with Excellent Preservation and Hoard of ArtifactsThe items were wrapped in textiles and buried in the pot. The hoard includes:

Six silver Anglo-Saxon disc brooches dating to around the early 9th century. They are equal to another hoard of similar brooches found in England, the Pentney hoard, which was the largest such hoard found to date. The Pentney hoard is now in the British Musuem.A silver penannular brooch of Irish origin. Penannular means it is in the form of an incomplete ring.Byzantium silk from around Istanbul.A gold ingotA large number of silver ingotsSilver arm ringsA beautifully preserved crossAn ornate gold pin in the form of a birdGold and crystal objects wrapped in cloth bundles. Some of the treasures: A silver disk brooch decorated with intertwining snakes or serpents (

Historic Scotland

), a gold, bird-shaped object which may have been a decorative pin or a manuscript pointer (

Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland

), one of the many arm rings with a runic inscription (

Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland

), a large glass bead (

Santiago Arribas Pena

), and a hinged silver strap (

Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland

). Of these last, the press release says:

Some of the treasures: A silver disk brooch decorated with intertwining snakes or serpents (

Historic Scotland

), a gold, bird-shaped object which may have been a decorative pin or a manuscript pointer (

Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland

), one of the many arm rings with a runic inscription (

Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland

), a large glass bead (

Santiago Arribas Pena

), and a hinged silver strap (

Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland

). Of these last, the press release says:

The Carolingian vessel filled with artifacts. (

Historic Environment Scotland

)The process leading up to the extraction was precise yet exciting, according to Richard Welander of Historic Environment Scotland:

The Carolingian vessel filled with artifacts. (

Historic Environment Scotland

)The process leading up to the extraction was precise yet exciting, according to Richard Welander of Historic Environment Scotland:

Lucky treasure seeker unearths 1,000-year-old Viking coin hoard in WalesTop 10 Treasure, Artifact, and Valuable Finds of 2015The Controversial Origins of the Maine Penny, A Norse Coin found in a Native American SettlementThe Treasure Trove Unit will assess its value on behalf of the crown, though the finder, Derek McClennan will be eligible for the market value. (It is estimated to be worth at least £1 million.) Mr. McClennan found the hoard in a Galloway field in September 2014.

The Church of Scotland, which owns the land, has reached an agreement with Mr. McLennan about the equitable sharing of any proceeds that will eventually be awarded. The hoard is now with the Scottish Treasure Trove Unit until it has been fully examined and a decision is made about its future location.

After assessment, the hoard will be offered to Scottish museums. It will go on display in the museum that meets the market value price and buys it.

“Nothing was thrown in the vessel,” Olwyn Owen, an independent Viking scholar in Edinburgh, told National Geographic. The hoard was “wrapped with great care and packed extremely tightly together, and they are such special objects that they were clearly enormously important to their Viking owner. It’s a strange and wonderful selection of objects.”

Featured Image: A finely wrought Carolingian vessel, still encrusted with pieces of textile ( Historic Environment Scotland ), a gold pendant ( Santiago Arribas Pena ), and a silver brooch from Ireland. ( Santiago Arribas Pena )

By Mark Miller

Around the time the Irish were stamping out the Viking presence in their country, local lore says the Scots and Vikings also fought a battle near Galloway, Scotland. In 2014, a metal detectorist took that legend, swept the area, and discovered a hoard of 100 “strange and wonderful objects” that were about 1,000 years old.

Around the time the Irish were stamping out the Viking presence in their country, local lore says the Scots and Vikings also fought a battle near Galloway, Scotland. In 2014, a metal detectorist took that legend, swept the area, and discovered a hoard of 100 “strange and wonderful objects” that were about 1,000 years old.[image error]No one knows how the person who buried the hoard came across the spectacular stuff or why it was buried. One can only speculate that perhaps there was a battle, and perhaps the items were buried beforehand or during the course of it in case the one who hid the hoard had to flee.

Conservators are just now releasing images of the Galloway hoard, showing items found in a Carolingian vessel or pot. The pot itself, from Western Europe, is very rare and is one of only six of the type ever found.

The Carolingian vessel. (

Historic Environment Scotland

) “The hoard is the most important Viking discovery in Scotland for over 100 years. The items from within the vessel, which may have been accumulated over a number of generations, reveal objects from across Europe and from other cultures with non-Viking origins,” says a press release from Historic Scotland.

The Carolingian vessel. (

Historic Environment Scotland

) “The hoard is the most important Viking discovery in Scotland for over 100 years. The items from within the vessel, which may have been accumulated over a number of generations, reveal objects from across Europe and from other cultures with non-Viking origins,” says a press release from Historic Scotland.Massive Viking Hoard Unearthed by Treasure Hunter Publicly Revealed for First TimeTreasure hunter uncovers one of the most significant Viking hoards ever found in ScotlandThe Oseberg Ship Burial Astounded Archaeologists with Excellent Preservation and Hoard of ArtifactsThe items were wrapped in textiles and buried in the pot. The hoard includes:

Six silver Anglo-Saxon disc brooches dating to around the early 9th century. They are equal to another hoard of similar brooches found in England, the Pentney hoard, which was the largest such hoard found to date. The Pentney hoard is now in the British Musuem.A silver penannular brooch of Irish origin. Penannular means it is in the form of an incomplete ring.Byzantium silk from around Istanbul.A gold ingotA large number of silver ingotsSilver arm ringsA beautifully preserved crossAn ornate gold pin in the form of a birdGold and crystal objects wrapped in cloth bundles.

Some of the treasures: A silver disk brooch decorated with intertwining snakes or serpents (

Historic Scotland

), a gold, bird-shaped object which may have been a decorative pin or a manuscript pointer (

Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland

), one of the many arm rings with a runic inscription (

Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland

), a large glass bead (

Santiago Arribas Pena

), and a hinged silver strap (

Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland

). Of these last, the press release says:

Some of the treasures: A silver disk brooch decorated with intertwining snakes or serpents (

Historic Scotland

), a gold, bird-shaped object which may have been a decorative pin or a manuscript pointer (

Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland

), one of the many arm rings with a runic inscription (

Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland

), a large glass bead (

Santiago Arribas Pena

), and a hinged silver strap (

Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland

). Of these last, the press release says:At the moment their purpose remains a mystery. While it’s clear many of the objects collected have a value as precious metal, the nature of the hoard remains a mystery, and includes objects in base metals and glass beads which have no obvious value. The decision about which material to include in the vessel appears to have been based on complex and highly personal notions of how an individual valued an object as much as the bullion value the objects represented.Conservators have been working to remove the items from the pot and preserve them. They are with Historic Environment Scotland, the Treasure Trove Unit, and the Queen’s and Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer.

The Carolingian vessel filled with artifacts. (

Historic Environment Scotland

)The process leading up to the extraction was precise yet exciting, according to Richard Welander of Historic Environment Scotland:

The Carolingian vessel filled with artifacts. (

Historic Environment Scotland

)The process leading up to the extraction was precise yet exciting, according to Richard Welander of Historic Environment Scotland:Before removing the objects we took the rather unusual measure of having the pot CT scanned, in order that we could get a rough idea of what was in there and best plan the delicate extraction process. That exercise offered us a tantalising glimpse but didn’t prepare me for what was to come. These stunning objects provide us with an unparalleled insight to what was going on in the minds of the Vikings in Galloway all those years ago. They tell us about the sensibilities of the time, reveal displays of regal rivalries, and some of the objects even betray an underlying sense of humour, which the Vikings aren’t always renowned for!Stuart Campbell of the Treasure Trove Unit says in the press release that the complexity of the hoard raised more questions than it answered, and for years to come scholars and researchers will study the motivations and cultural identity of those who buried it.

Lucky treasure seeker unearths 1,000-year-old Viking coin hoard in WalesTop 10 Treasure, Artifact, and Valuable Finds of 2015The Controversial Origins of the Maine Penny, A Norse Coin found in a Native American SettlementThe Treasure Trove Unit will assess its value on behalf of the crown, though the finder, Derek McClennan will be eligible for the market value. (It is estimated to be worth at least £1 million.) Mr. McClennan found the hoard in a Galloway field in September 2014.

The Church of Scotland, which owns the land, has reached an agreement with Mr. McLennan about the equitable sharing of any proceeds that will eventually be awarded. The hoard is now with the Scottish Treasure Trove Unit until it has been fully examined and a decision is made about its future location.

After assessment, the hoard will be offered to Scottish museums. It will go on display in the museum that meets the market value price and buys it.

“Nothing was thrown in the vessel,” Olwyn Owen, an independent Viking scholar in Edinburgh, told National Geographic. The hoard was “wrapped with great care and packed extremely tightly together, and they are such special objects that they were clearly enormously important to their Viking owner. It’s a strange and wonderful selection of objects.”

Featured Image: A finely wrought Carolingian vessel, still encrusted with pieces of textile ( Historic Environment Scotland ), a gold pendant ( Santiago Arribas Pena ), and a silver brooch from Ireland. ( Santiago Arribas Pena )

By Mark Miller

Published on April 06, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Julius Caesar defeats Caecilius Metellus Scipio

April 6

46 BC – Julius Caesar defeated Caecilius Metellus Scipio and Marcus Porcius Cato in the battle of Thapsus.

46 BC – Julius Caesar defeated Caecilius Metellus Scipio and Marcus Porcius Cato in the battle of Thapsus.

Published on April 06, 2016 01:30

April 5, 2016

Ruins of a Legendary Medieval Castle Uncovered in Scotland

Ancient Origins

A legendary castle dating back to the 12th century has been relocated after being lost for more than a century. The building was uncovered during work by Scottish Water in the area of the medieval village of Partick, now Glasgow, in Scotland. The ruins of the castle were swept away by the building of a Victorian railway station..

A legendary castle dating back to the 12th century has been relocated after being lost for more than a century. The building was uncovered during work by Scottish Water in the area of the medieval village of Partick, now Glasgow, in Scotland. The ruins of the castle were swept away by the building of a Victorian railway station..

[image error] Excavation of Partick Castle walls and ditch. (

GUARD Archaeology Ltd

)For decades, archaeologists believed that the castle may have been built in Partick on the banks of the River Kelvin by a king of Strathclyde. The settlement existed from the 7th century, when the first hunting lodge in the area was built. The construction of the castle was linked to the creation of a medieval church in Govan dedicated to St. Constantine, on the other side of a ford across the River Clyde.

Excavation of Partick Castle walls and ditch. (

GUARD Archaeology Ltd

)For decades, archaeologists believed that the castle may have been built in Partick on the banks of the River Kelvin by a king of Strathclyde. The settlement existed from the 7th century, when the first hunting lodge in the area was built. The construction of the castle was linked to the creation of a medieval church in Govan dedicated to St. Constantine, on the other side of a ford across the River Clyde.

A 19th century artist's impression of the second Partick Castle on the banks of the Kelvin, looking south towards Govan. (Mitchell Library, Special Collections)According to the Scotsman, the physical remains of the legendary Partick Castle have been uncovered by construction workers carrying out improvements to the city’s waste water infrastructure. In medieval times, the castle was a country retreat for the powerful bishops of Glasgow. The results published by experts from Guard Archaeology say that they've already discovered fragments of metalwork, pottery, glass, leather, and animal bones.

A 19th century artist's impression of the second Partick Castle on the banks of the Kelvin, looking south towards Govan. (Mitchell Library, Special Collections)According to the Scotsman, the physical remains of the legendary Partick Castle have been uncovered by construction workers carrying out improvements to the city’s waste water infrastructure. In medieval times, the castle was a country retreat for the powerful bishops of Glasgow. The results published by experts from Guard Archaeology say that they've already discovered fragments of metalwork, pottery, glass, leather, and animal bones.

A variety of fragments that survived under generations of industrial use on the site. (

GUARD Archaeology

)Hugh McBrien, of West of Scotland Archaeology Service, said:

A variety of fragments that survived under generations of industrial use on the site. (

GUARD Archaeology

)Hugh McBrien, of West of Scotland Archaeology Service, said:

The excavations began due to the decisions of developers. They had planned to build student housing at the site of the Partick Castle. It is unknown if will they change their mind after this discovery, which may be an interesting tourist attraction.

Discovery of Pictish Fort Reveals Iron Age Look-Out post for Sea RaidersBody Snatchers and Tortured Spirits: The Dark History of the South Bridge Vaults of EdinburghMyth and mystery of the Blarney Stone has been shattered by new researchTogether for two millennia: Iron Age burial containing father and son weavers unearthed in ScotlandThe finding became possible after a long analysis of the plans of Partick. The history of this area is well documented on old maps. In 19th century plans it is possible to understand the industrialization of the time. The village Partick was first known as Perdyc, and was founded during the reign of King David I of Scotland, who granted parts of the area called "lands of Perdyc" to Bishop John Achaius in 1136 AD.

Govan, Scotland region (from the 1654 Blaeu map of Scotland). (

Public Domain

) Partick is found in the upper left corner of the map.However, the name Partick comes from much earlier times, during the period when the Kingdom of Strathclyde ruled the area. The territory which belonged to them also contained Govan on the opposite side of the River Clyde. The local language was a form of Cymro-Celtic, which highly influenced modern-day Welsh. The earliest name of Partick comes from the Cymro-Celtic. Per means sweet fruit, and Teq means beautiful or fair.

Govan, Scotland region (from the 1654 Blaeu map of Scotland). (

Public Domain

) Partick is found in the upper left corner of the map.However, the name Partick comes from much earlier times, during the period when the Kingdom of Strathclyde ruled the area. The territory which belonged to them also contained Govan on the opposite side of the River Clyde. The local language was a form of Cymro-Celtic, which highly influenced modern-day Welsh. The earliest name of Partick comes from the Cymro-Celtic. Per means sweet fruit, and Teq means beautiful or fair.

The Kingdom of Strathclyde collapsed in the 12th century. As mentioned before, the village of Partick became the property of bishops. It was perhaps also an important religious center during the 13th and early 14th century, but there is no archaeological evidence for that.

Partick Bridge over the Kelvin, 1846. (

Gregor Macgregor

)The final version of Partick Castle was built in 1611 for George Hutcheson, a wealthy Glasgow merchant and benefactor. Hutcheson was also one of the brothers who founded Hutchesons' Hospital and Hutchesons' Grammar School in Glasgow.

Partick Bridge over the Kelvin, 1846. (

Gregor Macgregor

)The final version of Partick Castle was built in 1611 for George Hutcheson, a wealthy Glasgow merchant and benefactor. Hutcheson was also one of the brothers who founded Hutchesons' Hospital and Hutchesons' Grammar School in Glasgow.

Historians writing in the 19th century suggested the castle was abandoned by 1770 and most of its stone was reused by locals. Partick Castle had almost completely disappeared in the early 19th century.

The remains are thought to be of two buildings, one dating back to the 12th or 13th century, and a later structure from the early 1600s. (

The Scotsman

)Now, after 800 years, the discovery of Partick Castle is described by McBrien as” the most significant archaeological discovery in Glasgow in a generation.". This castle appears as a symbol of the former power of Scotland.

The remains are thought to be of two buildings, one dating back to the 12th or 13th century, and a later structure from the early 1600s. (

The Scotsman

)Now, after 800 years, the discovery of Partick Castle is described by McBrien as” the most significant archaeological discovery in Glasgow in a generation.". This castle appears as a symbol of the former power of Scotland.

Featured Image: Partick Castle, a watercolor painting by John A. Gilfillan (1793-1864). Source: The Glasgow Story

By Natalia Klimczak

A legendary castle dating back to the 12th century has been relocated after being lost for more than a century. The building was uncovered during work by Scottish Water in the area of the medieval village of Partick, now Glasgow, in Scotland. The ruins of the castle were swept away by the building of a Victorian railway station..

A legendary castle dating back to the 12th century has been relocated after being lost for more than a century. The building was uncovered during work by Scottish Water in the area of the medieval village of Partick, now Glasgow, in Scotland. The ruins of the castle were swept away by the building of a Victorian railway station..[image error]

Excavation of Partick Castle walls and ditch. (

GUARD Archaeology Ltd

)For decades, archaeologists believed that the castle may have been built in Partick on the banks of the River Kelvin by a king of Strathclyde. The settlement existed from the 7th century, when the first hunting lodge in the area was built. The construction of the castle was linked to the creation of a medieval church in Govan dedicated to St. Constantine, on the other side of a ford across the River Clyde.

Excavation of Partick Castle walls and ditch. (

GUARD Archaeology Ltd