MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 104

April 28, 2016

History Trivia - Emperor Constantius II visits Rome

April 28

357 Emperor Constantius II, after dealing with the Franks, visited Rome before moving his army north to campaign against the Sarmatians, Suevi and the Quadi along the Danube. Constantius spent most of his reign quelling uprisings throughout the Roman Empire, succumbing to a fever in the winter of 361 at Mopsucrene (central Turkey).

357 Emperor Constantius II, after dealing with the Franks, visited Rome before moving his army north to campaign against the Sarmatians, Suevi and the Quadi along the Danube. Constantius spent most of his reign quelling uprisings throughout the Roman Empire, succumbing to a fever in the winter of 361 at Mopsucrene (central Turkey).

Published on April 28, 2016 01:00

April 27, 2016

History Trivia - Battle of Dunbar

April 27

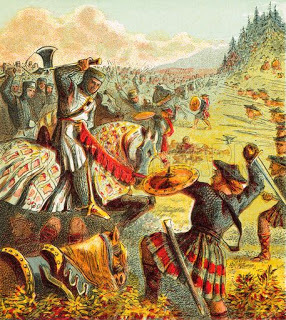

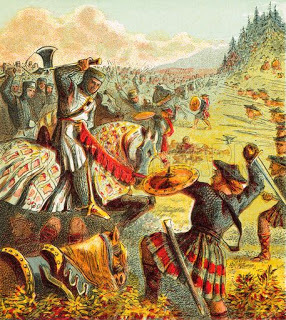

1296 Battle of Dunbar: The Scots were defeated by Edward I of England. This battle was the only significant field action in the campaign of 1296 when King Edward I of England had invaded Scotland to punish King John Balliol for his refusal to support English military action in France.

1296 Battle of Dunbar: The Scots were defeated by Edward I of England. This battle was the only significant field action in the campaign of 1296 when King Edward I of England had invaded Scotland to punish King John Balliol for his refusal to support English military action in France.

Published on April 27, 2016 06:00

Have we completely misinterpreted Shakespeare’s Richard III?

History Extra

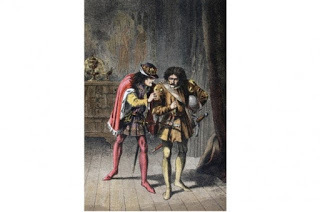

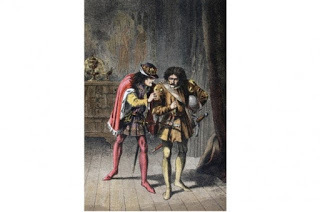

King Richard speaks to James Tyrrell (portrayed by Shakespeare as the man who organises the murder of the princes in the Tower) in Shakespeare’s ‘Richard III’. From ‘The Illustrated Library Shakespeare’, published in London in 1890. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

King Richard speaks to James Tyrrell (portrayed by Shakespeare as the man who organises the murder of the princes in the Tower) in Shakespeare’s ‘Richard III’. From ‘The Illustrated Library Shakespeare’, published in London in 1890. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of King Richard the Third is a masterpiece: the depiction of evil that dares us to like the villain and question, as we laugh along with his jokes, why we find such a man attractive.

The play is believed to have been written in around 1593 and its political context gives it a wider meaning. Queen Elizabeth I was ageing and obviously not going to produce an heir. The question of the succession grew like a weed, untended by all (at least in public), yet the identity of the next monarch was of huge importance to the entire country. Religious tensions ran high and the swings between the Protestant Edward VI, the Catholic Mary I and the Protestant Elizabeth I were still causing turmoil 60 years after Henry VIII’s reformation.

Portrait of Elizabeth I of England c1593. Found in the collection of Elizabethan Gardens, Manteo. Artist anonymous. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

Shakespeare is believed by some to have been a devout Catholic all of his life, hiding his faith and working for sponsors such as the earls of Essex and Southampton, whose sympathies were also with the old faith. Opposed to those keen for a return to Catholicism was the powerful Cecil family. William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, had been Elizabeth’s constant supporter and advisor throughout her reign and was, by the early 1590s, as old age crept up on him, paving the way for his son to take on the same role. The Cecils favoured a Protestant succession by James VI of Scotland. It is against this backdrop that Shakespeare wrote his play and his real villain may have been a very contemporary player.

The Tragedy of King Richard the Third is replete with demonstrable errors of fact, chronology and geography. The first edition reversed the locations of Northampton and Stony Stratford to allow Richard to ambush the party of Edward V (one of the princes in the Tower) party rather than have them travel beyond the meeting place. Early in the play Richard tells his audience “I’ll marry Warwick’s youngest daughter./ What, though I kill’d her husband and her father?’” Accounts of both the battles of Barnet (April 1471) and Tewkesbury (May 1471) make it almost certain neither Warwick nor Edward of Westminster was killed by Richard.

The ending of the play is also misinterpreted. The infamous “A horse, a horse! My kingdom for a horse!” is often mistaken for a cowardly plea to flee the field. Read in context, it is in fact Richard demanding a fresh horse to re-enter the fray and seek out Richmond (Henry Tudor). Even Shakespeare did not deny Richard his valiant end.

Illumination of the 1471 battle of Tewkesbury, dated 15th century. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

Shakespeare’s Richard delights in arranging the murder of his brother Clarence by their other brother Edward IV through trickery when in fact Edward’s execution of Clarence was believed by contemporaries to have driven a wedge between them that kept Richard away from Edward’s court. The seed of this misdirection is sown much earlier in the cycle of history plays too. In Henry VI, Part II Richard kills the Duke of Somerset at the battle of St Albans in 1455, when in fact he was just two-and-a-half years old.

The revelation at the beginning of the play that King Edward fears a prophesy that ‘G’ will disinherit his sons is perhaps another signpost to misdirection. Edward and Richard’s brother George, Duke of Clarence tells Richard “He hearkens after prophecies and dreams./ And from the cross-row plucks the letter G./ And says a wizard told him that by G/ His issue disinherited should be./ And, for my name of George begins with G./ It follows in his thought that I am he.”

George is therefore assumed to be the threat, ignoring the fact the Richard’s title, Duke of Gloucester, also marks him as a ‘G’. Before Clarence arrives, Richard appears to know of the prophesy and that George will be the target of Edward’s fear, suggesting that he had a hand in the trick and that a thin veil is being drawn over the obvious within the play. The true villain is slipping past unseen as signs are misread or ignored.

The language of the play’s famous opening soliloquy is interesting in the context of when it was written. In autumn 1592, Thomas Nashe’s play Summer’s Last Will and Testament was first performed in Croydon. Narrated by the ghost of Will Summer, Henry VIII’s famous court jester, it tells the story of the seasons and their adherents. Summer is king but lacks an heir, lamenting “Had I some issue to sit on my throne,/ My grief would die, death should not hear me grone”. Summer adopts Autumn as his heir but Winter will then follow – and his rule is not to be looked forward to. When Richard tells us “Now is the winter of our discontent/ Made glorious summer by this sun of York” it is perhaps not, at least not only, a clever reference to Edward IV’s badge of the sunne in splendour.

Elizabeth I, great-granddaughter of Edward IV, could be the “sun of York”, and this might explain the use of “sun” rather than “son”. Using Nashe’s allegory, Elizabeth is made summer by her lack of an heir that allows winter, his real villain, in during the autumn of her reign. The very first word of the play might be a hint that Shakespeare expected his audience to understand that the relevance of the play is very much “Now”.

Richard was able to perform this role for Shakespeare because of his unique position as a figure who could be abused but who also provided the moral tale and political parallels the playwright needed. The Yorkist family of Edward IV were direct ancestors of Elizabeth I and attacking them would have been a very bad move. Richard stood outside this protection. By imbuing Richard with the deeds of his father at St Albans, there is a link between the actions and sins of father and son, the son eventually causing the catastrophic downfall of his house. Here, Shakespeare returns to the father and son team now leading England toward a disaster – the Cecils.

I suspect that Shakespeare meant his audience to recognise, in the play’s Richard III character, Robert Cecil, William’s son – and that in the 1590s they would very clearly have done so. Motley’s History of the Netherlands (published in 1888) described Robert’s appearance in 1588 as “A slight, crooked, hump-backed young gentleman, dwarfish in stature” and later remarked on the “massive dissimulation” that would “constitute a portion of his own character”. Robert Cecil had kyphosis – in Shakespeare’s crude parlance, a hunchback – and a reputation for dissimulation. I imagine Shakespeare’s first audience nudging each other as Richard hobbled onto the stage and whispering that it was plainly Robert Cecil.

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury (1563–1612). (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

The warnings of the play are clear: Richard upturns the natural order, supplanting a rightful heir for his own gain, and Shakespeare’s Catholic sponsors may well have viewed Cecil in the same light as he planned a Protestant succession. We almost like Richard, and we are supposed to. Elizabeth called Robert Cecil her “little imp” and showed him great favour. Richard tells us that he is “determined to prove a villain” and Shakespeare was warning his audience that Robert Cecil similarly used a veil of amiability to hide his dangerous intentions.

Robert Cecil got his Protestant succession. William Shakespeare became a legend. Richard III entered the collective consciousness as a villain. Perhaps it was by accident and the time has come to look more closely at the man rather than the myth.

Matthew Lewis is the author of Richard, Duke of York: King by Right (Amberley Publishing, 2016).

King Richard speaks to James Tyrrell (portrayed by Shakespeare as the man who organises the murder of the princes in the Tower) in Shakespeare’s ‘Richard III’. From ‘The Illustrated Library Shakespeare’, published in London in 1890. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

King Richard speaks to James Tyrrell (portrayed by Shakespeare as the man who organises the murder of the princes in the Tower) in Shakespeare’s ‘Richard III’. From ‘The Illustrated Library Shakespeare’, published in London in 1890. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images) William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of King Richard the Third is a masterpiece: the depiction of evil that dares us to like the villain and question, as we laugh along with his jokes, why we find such a man attractive.

The play is believed to have been written in around 1593 and its political context gives it a wider meaning. Queen Elizabeth I was ageing and obviously not going to produce an heir. The question of the succession grew like a weed, untended by all (at least in public), yet the identity of the next monarch was of huge importance to the entire country. Religious tensions ran high and the swings between the Protestant Edward VI, the Catholic Mary I and the Protestant Elizabeth I were still causing turmoil 60 years after Henry VIII’s reformation.

Portrait of Elizabeth I of England c1593. Found in the collection of Elizabethan Gardens, Manteo. Artist anonymous. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

Shakespeare is believed by some to have been a devout Catholic all of his life, hiding his faith and working for sponsors such as the earls of Essex and Southampton, whose sympathies were also with the old faith. Opposed to those keen for a return to Catholicism was the powerful Cecil family. William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, had been Elizabeth’s constant supporter and advisor throughout her reign and was, by the early 1590s, as old age crept up on him, paving the way for his son to take on the same role. The Cecils favoured a Protestant succession by James VI of Scotland. It is against this backdrop that Shakespeare wrote his play and his real villain may have been a very contemporary player.

The Tragedy of King Richard the Third is replete with demonstrable errors of fact, chronology and geography. The first edition reversed the locations of Northampton and Stony Stratford to allow Richard to ambush the party of Edward V (one of the princes in the Tower) party rather than have them travel beyond the meeting place. Early in the play Richard tells his audience “I’ll marry Warwick’s youngest daughter./ What, though I kill’d her husband and her father?’” Accounts of both the battles of Barnet (April 1471) and Tewkesbury (May 1471) make it almost certain neither Warwick nor Edward of Westminster was killed by Richard.

The ending of the play is also misinterpreted. The infamous “A horse, a horse! My kingdom for a horse!” is often mistaken for a cowardly plea to flee the field. Read in context, it is in fact Richard demanding a fresh horse to re-enter the fray and seek out Richmond (Henry Tudor). Even Shakespeare did not deny Richard his valiant end.

Illumination of the 1471 battle of Tewkesbury, dated 15th century. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

Shakespeare’s Richard delights in arranging the murder of his brother Clarence by their other brother Edward IV through trickery when in fact Edward’s execution of Clarence was believed by contemporaries to have driven a wedge between them that kept Richard away from Edward’s court. The seed of this misdirection is sown much earlier in the cycle of history plays too. In Henry VI, Part II Richard kills the Duke of Somerset at the battle of St Albans in 1455, when in fact he was just two-and-a-half years old.

The revelation at the beginning of the play that King Edward fears a prophesy that ‘G’ will disinherit his sons is perhaps another signpost to misdirection. Edward and Richard’s brother George, Duke of Clarence tells Richard “He hearkens after prophecies and dreams./ And from the cross-row plucks the letter G./ And says a wizard told him that by G/ His issue disinherited should be./ And, for my name of George begins with G./ It follows in his thought that I am he.”

George is therefore assumed to be the threat, ignoring the fact the Richard’s title, Duke of Gloucester, also marks him as a ‘G’. Before Clarence arrives, Richard appears to know of the prophesy and that George will be the target of Edward’s fear, suggesting that he had a hand in the trick and that a thin veil is being drawn over the obvious within the play. The true villain is slipping past unseen as signs are misread or ignored.

The language of the play’s famous opening soliloquy is interesting in the context of when it was written. In autumn 1592, Thomas Nashe’s play Summer’s Last Will and Testament was first performed in Croydon. Narrated by the ghost of Will Summer, Henry VIII’s famous court jester, it tells the story of the seasons and their adherents. Summer is king but lacks an heir, lamenting “Had I some issue to sit on my throne,/ My grief would die, death should not hear me grone”. Summer adopts Autumn as his heir but Winter will then follow – and his rule is not to be looked forward to. When Richard tells us “Now is the winter of our discontent/ Made glorious summer by this sun of York” it is perhaps not, at least not only, a clever reference to Edward IV’s badge of the sunne in splendour.

Elizabeth I, great-granddaughter of Edward IV, could be the “sun of York”, and this might explain the use of “sun” rather than “son”. Using Nashe’s allegory, Elizabeth is made summer by her lack of an heir that allows winter, his real villain, in during the autumn of her reign. The very first word of the play might be a hint that Shakespeare expected his audience to understand that the relevance of the play is very much “Now”.

Richard was able to perform this role for Shakespeare because of his unique position as a figure who could be abused but who also provided the moral tale and political parallels the playwright needed. The Yorkist family of Edward IV were direct ancestors of Elizabeth I and attacking them would have been a very bad move. Richard stood outside this protection. By imbuing Richard with the deeds of his father at St Albans, there is a link between the actions and sins of father and son, the son eventually causing the catastrophic downfall of his house. Here, Shakespeare returns to the father and son team now leading England toward a disaster – the Cecils.

I suspect that Shakespeare meant his audience to recognise, in the play’s Richard III character, Robert Cecil, William’s son – and that in the 1590s they would very clearly have done so. Motley’s History of the Netherlands (published in 1888) described Robert’s appearance in 1588 as “A slight, crooked, hump-backed young gentleman, dwarfish in stature” and later remarked on the “massive dissimulation” that would “constitute a portion of his own character”. Robert Cecil had kyphosis – in Shakespeare’s crude parlance, a hunchback – and a reputation for dissimulation. I imagine Shakespeare’s first audience nudging each other as Richard hobbled onto the stage and whispering that it was plainly Robert Cecil.

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury (1563–1612). (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

The warnings of the play are clear: Richard upturns the natural order, supplanting a rightful heir for his own gain, and Shakespeare’s Catholic sponsors may well have viewed Cecil in the same light as he planned a Protestant succession. We almost like Richard, and we are supposed to. Elizabeth called Robert Cecil her “little imp” and showed him great favour. Richard tells us that he is “determined to prove a villain” and Shakespeare was warning his audience that Robert Cecil similarly used a veil of amiability to hide his dangerous intentions.

Robert Cecil got his Protestant succession. William Shakespeare became a legend. Richard III entered the collective consciousness as a villain. Perhaps it was by accident and the time has come to look more closely at the man rather than the myth.

Matthew Lewis is the author of Richard, Duke of York: King by Right (Amberley Publishing, 2016).

Published on April 27, 2016 03:00

April 26, 2016

A seventh wife for Henry VIII?

History Extra

Katherine Willoughby in an 18th-century engraving after a Hans Holbein the Younger portrait. In 1546 the prospect of her marrying England’s ageing king was causing tongues to wag in diplomatic circles. (© National Portrait Gallery)

Katherine Willoughby in an 18th-century engraving after a Hans Holbein the Younger portrait. In 1546 the prospect of her marrying England’s ageing king was causing tongues to wag in diplomatic circles. (© National Portrait Gallery)

In February 1546, the imperial ambassador François van der Delft wrote to his master, Holy Roman emperor Charles V, to acquaint him with a story he had heard circulating in aristocratic and diplomatic circles. “Sire, I am confused and apprehensive to inform your majesty,” he began apologetically, “that there are rumours here of a new queen, although I do not know why, or how true it may be. Some people attribute it to the sterility of the present queen [Katherine Parr] whilst others say that there will be no change whilst the present war [with France] lasts. Madame Suffolk is much talked about, and is in great favour; but the king shows no alteration in his demeanour towards the queen, though the latter, as I am informed, is somewhat annoyed at the rumours.”

The speculation had reached Europe by early March when Stephen Vaughan, the king’s agent in Antwerp, advised lord chancellor Thomas Wriothesley and diplomat William Paget that: “This day came to my lodging a… merchant of this town, saying that he had dined with certain friends, one of whom offered to lay a wager with him that the king’s majesty would have another wife; and he prayed me to show him the truth. He would not tell me who offered the wager, and I said that I never heard of any such thing, and that there was no such thing. Many folks talk of this matter, and from whence it comes I cannot learn.”

Better humour‘Madame Suffolk’ was Katherine Willoughby, Duchess of Suffolk, the widow of King Henry’s closest friend, Charles Brandon, who had died in August 1545. Married to Brandon in 1533 when she was 14 and he nearly 50, Katherine had many opportunities to meet the king socially in the 1530s and 1540s. Henry undoubtedly liked her – they began exchanging new year gifts in 1534 – and Eustace Chapuys, van der Delft’s predecessor as imperial ambassador, noted that he had been “masking and visiting” with her in March 1538, only months after Jane Seymour’s death.

“The king,” wrote Chapuys, “has been in much better humour than ever he was, making musicians play on their instruments all day along. He went to dine at a splendid house of his, where he had collected all his musicians, and, after giving orders for the erection of certain sumptuous buildings therein, returned home by water, surrounded by musicians, and went straight to visit the Duchess of Suffolk… and ever since cannot be one single moment without masks.”

So did Katherine and Henry become lovers at this period, and did Charles Brandon, who owed everything to his royal master, turn a diplomatically blind eye? The question is ultimately unanswerable, but Katherine’s appointment as a lady-in-waiting to Anne of Cleves, Catherine Howard and Katherine Parr would have allowed her to be constantly about the court without attracting comment.

William Carey had been recompensed for tolerating the king’s affair with his wife, Mary Boleyn, and it is possible to speculate that the rewards Brandon received were for more than his own good service. Perhaps Henry would have wed Katherine in the years after Jane Seymour’s death if she had been single, but Brandon’s longevity denied him the chance.

It’s possible that Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk (shown here), was recompensed for holding his tongue while King Henry pursued his wife. (© Topfoto)

By February 1546, when the rumours about a new wife were swirling, Henry had been married to Katherine Parr for two and a half years, and their relationship was not always amicable. Any hopes that she would give him a second son remained unrealised, and he sometimes found her forthright Protestant opinions too challenging for his liking. According to the martyrologist John Foxe, he was heard to complain that “a good hearing it is when women become such clerks; and a thing much to my comfort, to come in mine old days to be taught by my wife”; and the conservative bishop Stephen Gardiner offered to obtain evidence that the queen’s views were “treason cloaked with the cloak of heresy” and merited death.

But matters turned out rather differently. Foxe says that Henry confided his intentions to his physician Dr Wendy (who also attended Queen Katherine), and the bill detailing the charges against his wife was left where a friend of hers would find it. Forewarned, she seized the initiative, begging Henry to accept that she had disputed with him only to divert his mind from his infirmities, and in the hope that she would herself “profit from his learned discourse”. The king was mollified, and embraced her with the words: “And is it even so sweet heart? And tended your arguments to no worse end? Then perfect friends we are now again, as ever at any time heretofore.”

Queen and courtiersSeveral interpretations could be placed on these events, but perhaps the most obvious is that Katherine Parr was being warned and at the same time given an opportunity to redeem herself. Perhaps Henry was toying with his queen and his courtiers, playing off the reformers against the conservatives while showing both parties that he alone was in control of the situation.

Unfortunately, no one told Lord Chancellor Wriothesley what had happened, and when he came to arrest Katherine next morning he found her walking in the garden with her husband. He was sent packing with Henry’s curses ringing in his ears.

On the other hand, it is possible that the capricious monarch had seriously considered changing his wife again but had decided against it at the last moment.

A Hans Holbein drawing of Henry VIII. By February 1546 rumours were doing the rounds that the king was tiring of his sixth wife, Katherine Parr, and her strident Protestantism. (© AKG)

Katherine Willoughby was attractive and vivacious, but she shared Katherine Parr’s devotion to Protestantism and was also markedly self-opinionated. In later years she had to apologise to William Cecil for what she herself called her “foolish choler” and “brawling”, and while these characteristics may have amused Henry in small doses her feistiness could have made her less appealing as a seventh consort. Katherine may have felt disappointment, or perhaps relief that she had not had to make an equally difficult choice.

King Henry’s life was now almost over – he died in January 1547 – but Katherine still had many years to live. After losing her two sons by Brandon to the ‘sweating sickness’ in 1551, she married Richard Bertie, her gentleman-usher, and had another son and a daughter. She avoided involvement in the conspiracy built around her step-granddaughter, Lady Jane Grey, but still spent four years in exile in Europe while the Catholic queen Mary ruled England. She returned when Elizabeth succeeded, but disagreed profoundly – and vocally – with the queen’s more tolerant approach to religious matters. She died in 1580, and her magnificent monument can still be seen at Spilsby, Lincolnshire today.

Henry’s Last Years6 January 1540

Henry marries Anne of Cleves but their union is annulled on the grounds of non-consummation and an alleged pre-contract, on 9 July.

18 April 1540

Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s chief minister, is created Earl of Essex. However, he is executed, ostensibly for religious transgressions, on 28 July.

8 August 1540

Henry marries Catherine Howard. His union with a Catholic is widely seen as a victory for the religious conservatives over their evangelical opponents.

13 February 1542

Catherine Howard is executed after admitting to affairs with the courtiers Francis Dereham and Thomas Culpepper, the latter after her marriage to the king.

12 July 1543

Henry weds the twice-widowed Katherine Parr. Her preferred suitor, Thomas Seymour, the late Queen Jane’s brother, prudently stands aside.

Katherine Parr. (© Bridgeman)

1544

The third Act of Succession of Henry’s reign is passed in the spring. The ‘illegitimate’ princesses Mary and Elizabeth are restored to their places in the succession. Henry visits Boulogne after it surrenders to English forces on 13 September. But six years later the town is restored to the French.

19 January 1547

Henry Howard, the poet Earl of Surrey, is executed for foolishly misappropriating the royal arms. He defends himself brilliantly, but his fate is already sealed.

Henry Howard. (© Bridgeman)

David Baldwin’s books include a biography of Richard III (Amberley, 2013).

Katherine Willoughby in an 18th-century engraving after a Hans Holbein the Younger portrait. In 1546 the prospect of her marrying England’s ageing king was causing tongues to wag in diplomatic circles. (© National Portrait Gallery)

Katherine Willoughby in an 18th-century engraving after a Hans Holbein the Younger portrait. In 1546 the prospect of her marrying England’s ageing king was causing tongues to wag in diplomatic circles. (© National Portrait Gallery) In February 1546, the imperial ambassador François van der Delft wrote to his master, Holy Roman emperor Charles V, to acquaint him with a story he had heard circulating in aristocratic and diplomatic circles. “Sire, I am confused and apprehensive to inform your majesty,” he began apologetically, “that there are rumours here of a new queen, although I do not know why, or how true it may be. Some people attribute it to the sterility of the present queen [Katherine Parr] whilst others say that there will be no change whilst the present war [with France] lasts. Madame Suffolk is much talked about, and is in great favour; but the king shows no alteration in his demeanour towards the queen, though the latter, as I am informed, is somewhat annoyed at the rumours.”

The speculation had reached Europe by early March when Stephen Vaughan, the king’s agent in Antwerp, advised lord chancellor Thomas Wriothesley and diplomat William Paget that: “This day came to my lodging a… merchant of this town, saying that he had dined with certain friends, one of whom offered to lay a wager with him that the king’s majesty would have another wife; and he prayed me to show him the truth. He would not tell me who offered the wager, and I said that I never heard of any such thing, and that there was no such thing. Many folks talk of this matter, and from whence it comes I cannot learn.”

Better humour‘Madame Suffolk’ was Katherine Willoughby, Duchess of Suffolk, the widow of King Henry’s closest friend, Charles Brandon, who had died in August 1545. Married to Brandon in 1533 when she was 14 and he nearly 50, Katherine had many opportunities to meet the king socially in the 1530s and 1540s. Henry undoubtedly liked her – they began exchanging new year gifts in 1534 – and Eustace Chapuys, van der Delft’s predecessor as imperial ambassador, noted that he had been “masking and visiting” with her in March 1538, only months after Jane Seymour’s death.

“The king,” wrote Chapuys, “has been in much better humour than ever he was, making musicians play on their instruments all day along. He went to dine at a splendid house of his, where he had collected all his musicians, and, after giving orders for the erection of certain sumptuous buildings therein, returned home by water, surrounded by musicians, and went straight to visit the Duchess of Suffolk… and ever since cannot be one single moment without masks.”

So did Katherine and Henry become lovers at this period, and did Charles Brandon, who owed everything to his royal master, turn a diplomatically blind eye? The question is ultimately unanswerable, but Katherine’s appointment as a lady-in-waiting to Anne of Cleves, Catherine Howard and Katherine Parr would have allowed her to be constantly about the court without attracting comment.

William Carey had been recompensed for tolerating the king’s affair with his wife, Mary Boleyn, and it is possible to speculate that the rewards Brandon received were for more than his own good service. Perhaps Henry would have wed Katherine in the years after Jane Seymour’s death if she had been single, but Brandon’s longevity denied him the chance.

It’s possible that Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk (shown here), was recompensed for holding his tongue while King Henry pursued his wife. (© Topfoto)

By February 1546, when the rumours about a new wife were swirling, Henry had been married to Katherine Parr for two and a half years, and their relationship was not always amicable. Any hopes that she would give him a second son remained unrealised, and he sometimes found her forthright Protestant opinions too challenging for his liking. According to the martyrologist John Foxe, he was heard to complain that “a good hearing it is when women become such clerks; and a thing much to my comfort, to come in mine old days to be taught by my wife”; and the conservative bishop Stephen Gardiner offered to obtain evidence that the queen’s views were “treason cloaked with the cloak of heresy” and merited death.

But matters turned out rather differently. Foxe says that Henry confided his intentions to his physician Dr Wendy (who also attended Queen Katherine), and the bill detailing the charges against his wife was left where a friend of hers would find it. Forewarned, she seized the initiative, begging Henry to accept that she had disputed with him only to divert his mind from his infirmities, and in the hope that she would herself “profit from his learned discourse”. The king was mollified, and embraced her with the words: “And is it even so sweet heart? And tended your arguments to no worse end? Then perfect friends we are now again, as ever at any time heretofore.”

Queen and courtiersSeveral interpretations could be placed on these events, but perhaps the most obvious is that Katherine Parr was being warned and at the same time given an opportunity to redeem herself. Perhaps Henry was toying with his queen and his courtiers, playing off the reformers against the conservatives while showing both parties that he alone was in control of the situation.

Unfortunately, no one told Lord Chancellor Wriothesley what had happened, and when he came to arrest Katherine next morning he found her walking in the garden with her husband. He was sent packing with Henry’s curses ringing in his ears.

On the other hand, it is possible that the capricious monarch had seriously considered changing his wife again but had decided against it at the last moment.

A Hans Holbein drawing of Henry VIII. By February 1546 rumours were doing the rounds that the king was tiring of his sixth wife, Katherine Parr, and her strident Protestantism. (© AKG)

Katherine Willoughby was attractive and vivacious, but she shared Katherine Parr’s devotion to Protestantism and was also markedly self-opinionated. In later years she had to apologise to William Cecil for what she herself called her “foolish choler” and “brawling”, and while these characteristics may have amused Henry in small doses her feistiness could have made her less appealing as a seventh consort. Katherine may have felt disappointment, or perhaps relief that she had not had to make an equally difficult choice.

King Henry’s life was now almost over – he died in January 1547 – but Katherine still had many years to live. After losing her two sons by Brandon to the ‘sweating sickness’ in 1551, she married Richard Bertie, her gentleman-usher, and had another son and a daughter. She avoided involvement in the conspiracy built around her step-granddaughter, Lady Jane Grey, but still spent four years in exile in Europe while the Catholic queen Mary ruled England. She returned when Elizabeth succeeded, but disagreed profoundly – and vocally – with the queen’s more tolerant approach to religious matters. She died in 1580, and her magnificent monument can still be seen at Spilsby, Lincolnshire today.

Henry’s Last Years6 January 1540

Henry marries Anne of Cleves but their union is annulled on the grounds of non-consummation and an alleged pre-contract, on 9 July.

18 April 1540

Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s chief minister, is created Earl of Essex. However, he is executed, ostensibly for religious transgressions, on 28 July.

8 August 1540

Henry marries Catherine Howard. His union with a Catholic is widely seen as a victory for the religious conservatives over their evangelical opponents.

13 February 1542

Catherine Howard is executed after admitting to affairs with the courtiers Francis Dereham and Thomas Culpepper, the latter after her marriage to the king.

12 July 1543

Henry weds the twice-widowed Katherine Parr. Her preferred suitor, Thomas Seymour, the late Queen Jane’s brother, prudently stands aside.

Katherine Parr. (© Bridgeman)

1544

The third Act of Succession of Henry’s reign is passed in the spring. The ‘illegitimate’ princesses Mary and Elizabeth are restored to their places in the succession. Henry visits Boulogne after it surrenders to English forces on 13 September. But six years later the town is restored to the French.

19 January 1547

Henry Howard, the poet Earl of Surrey, is executed for foolishly misappropriating the royal arms. He defends himself brilliantly, but his fate is already sealed.

Henry Howard. (© Bridgeman)

David Baldwin’s books include a biography of Richard III (Amberley, 2013).

Published on April 26, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - birth of Marcus Aurelius

April 26

121 Marcus Aurelius (Roman Emperor 161-180) was born. He was the last of the "Five Good Emperors", and is also considered one of the most important Stoic philosophers.

121 Marcus Aurelius (Roman Emperor 161-180) was born. He was the last of the "Five Good Emperors", and is also considered one of the most important Stoic philosophers.

Published on April 26, 2016 01:30

April 25, 2016

Behaving badly: Henry V's misspent youth

History Extra

Henry V: dithering also-ran or medieval hero? (Credit: Bridgeman Images)

Henry V: dithering also-ran or medieval hero? (Credit: Bridgeman Images)

On Friday 25 October 1415, in a muddy field in Picardy, the reputation of Henry V as a great warrior king was sealed. His victory over the French at Agincourt had a major effect on his position both at home and abroad. Even before he returned to England, a grateful parliament had granted him all revenue from customs duties – a sizeable income – for life. As for the French, they never again dared to face him in battle. So Henry was able to conquer the whole of Normandy and advance on Paris, exploiting the divisions in France – between the Burgundian and Armagnac factions – that the defeat at Agincourt had exacerbated. The treaty of Troyes, signed in May 1420, sealed Henry’s acceptance as regent to Charles VI (‘The Mad’) and – through marriage to Charles’s daughter Katherine – heir to the throne of France. It seemed only a matter of time before he would rule over both England and France. At the parliament held at Westminster in December 1420, the chancellor explained why the English had “special cause to honour and thank God” for the deeds and victories of the king. He had recovered the ancient rights of the English crown in France. He had destroyed heresy in the realm – a reference to his actions against Sir John Oldcastle and the Lollards (critics of the established church) in 1414. And, in his youth, he had put down rebellion in Wales. In short, though Henry’s untimely death in 1422 curtailed the fulfilment of his plans, his career was, on the face of it, a complete success. As Thomas Walsingham, author of The St Albans Chronicle, expressed in a panegyric for the dead king: “He was a warrior, famous and blessed with good fortune who, in every war he undertook, always came away with victory.” But had Henry always been so successful? Let us reflect on Henry’s life before he became king.

This 15th-century illustration depicts Henry, then Prince of Wales, paying homage to the French king Charles VI. The Treaty of Troyes, signed in 1420, saw Henry named Charles’s regent; by marrying the latter’s daughter, Katherine, Henry secured his position as heir to the French throne. (Credit: Bridgeman Images)

There are ample reasons to believe that Henry the prince was a far cry from Henry the king. In Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2, Shakespeare portrays him as a medieval ‘hooray Henry’. In those plays, the prince chooses bad company; though wealthy, he prefers the low life and petty criminality; and it is only at his father’s deathbed and his own subsequent coronation that he reforms himself – becoming as excessively ‘correct’ as he was once so ‘incorrect’ for his social and political position. But was this fact as well as Shakespearean fiction? The first ‘published’ comments on Henry’s bad behaviour so far unearthed appear in the Latin lives written about him in the late 1430s. In the anonymous Vita et Gesta Henrici Quinti (often called the Pseudo-Elmham), Henry is described as being in his youth “an assiduous cultivator of lasciviousness…passing the bounds of modesty he was the fervent soldier of Venus as well as Mars; youthlike he was fired by her torches and in the midst of worthy works of war found leisure for excesses common to ungoverned age”. The work devotes much space to his last-minute repentance to his father for his bad behaviour. We could dismiss all of this as simply a good story – except that it was dealt with at great length, and in a work known to have drawn information from one of Henry’s courtiers: Walter, Lord Hungerford. In another work, the Vita Henrici Quinti by Tito Livio Frulovisi (now believed to have been derived from the Vita et Gesta), stories of a misspent youth and late change of heart are shorter, but remain. Given this work’s links with Henry’s last surviving brother, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, and the status of both works as eulogies for Henry V, we have to assume that the accounts of his youth are basically true – as are those of the well-publicised change of character at his accession. There are many intriguing facets to Prince Henry. For one thing, he had not been born to be king. Until just after his 13th birthday, in September 1399, he was merely the eldest son of the eldest son of a collateral line of King Richard II . He stood to inherit, in time, the duchy of Lancaster created for his grandfather John of Gaunt (d1399), the third son of Edward III. He was also to be bequeathed the earldom of Derby held by his father, Henry Bolingbroke (d1413), and the titles brought to the family by his co-heiress mother, Mary (d1394), daughter of Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Northampton, Essex and Hereford (d1373). So the career that lay ahead for the “young lord Henry” or “Lord Henry, son of the Earl of Derby”, as he is described in the financial records of his father and grandfather, was that of a peer – but at the time it seemed that he might have to wait many years for his inheritance. Tom Mison plays Prince Hal, with David Yelland as the old king, in a performance of Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part I. The play portrays Hal as a medieval ‘hooray Henry’. (Credit: Rex)

Tom Mison plays Prince Hal, with David Yelland as the old king, in a performance of Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part I. The play portrays Hal as a medieval ‘hooray Henry’. (Credit: Rex)

As it was, his life was completely transformed – first, in October 1398, by the exile of his father by Richard II; and then, the following September, by Bolingbroke’s return to England and usurpation of the throne as Henry IV. On 15 October 1399, two days after his father’s coronation, Henry was created Prince of Wales, Duke of Cornwall and Earl of Chester, and was acknowledged as heir to the throne. Later in October, the title Duke of Aquitaine was added and, on 10 November, that of Duke of Lancaster. Given the fragile political position of the new dynasty, Prince Henry was a vital cog in its establishment and, as such, shared in its problems – indeed, he experienced them even before the usurpation. In May 1399 the young Henry was taken to Ireland by Richard II , seemingly in an attempt to ensure his father’s good behaviour. It failed: in the king’s absence, Bolingbroke invaded England. Education in armsHenry was then 12 years old, an age at which it was customary for noble boys to begin gaining experience of military service, though they were not expected to actually participate in the fighting. So in the summer of 1400 he was assigned a company of troops within the huge army – over 13,000 strong – that his father took to Scotland. Then, as the army returned to England, the Welsh revolt began. The historian Adam Chapman has observed that it was no coincidence that Owain Glyndŵr declared himself Prince of Wales on 16 September 1400 – the 14th birthday of the formal holder of the title, Prince Henry. Only six months later, the latter found himself involved in his first siege, at Conwy. It is not surprising that the teenage prince learned under the tutelage of advisors appointed by his father. The young Henry held a number of nominal commands but was always guided by others, including Henry Hotspur, son of the Earl of Northumberland, and Hotspur’s uncle, Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester, who was appointed Prince Henry’s governor at the end of 1401. Yet these were the very men who, in 1403, rebelled against Henry IV and his son. So the battle of Shrewsbury on 21 July, when he faced his erstwhile mentors, must have been a chastening experience for the prince – not least because he was wounded by an arrow that pierced his left cheek. The surgeon John Bradmore removed the arrowhead, but the wound put the prince out of action for a year or so. Even as Henry entered his late teens, his father was reluctant to give him complete authority in the Welsh wars. The young prince was neither wholly committed nor effective, and constantly complained of being kept short of funds. Alongside praise for the prince’s good heart and courage, the speaker of the parliament of March 1406 also urged that he should maintaincontinual residence in Wales for the sake of the wars – an indication that he had not been attentive to his duties. All did not go well with the prince’s campaigns. In 1407, at the siege of Aberystwyth, Henry theatrically negotiated its peaceful surrender, withdrawing his troops; Glyndwˆ r, though, simply occupied the castle. Aberystwyth remained in rebel hands until September 1408 and was recovered, as was Harlech in 1409, not by the prince in person but by those to whom he delegated. This late 15th century illustration shows prisoners being taken at Agincourt. Some of Henry’s earlier military endeavours had not met with such success. (Credit: Alamy)

This late 15th century illustration shows prisoners being taken at Agincourt. Some of Henry’s earlier military endeavours had not met with such success. (Credit: Alamy)

Sickly and sexed upAs the late Welsh historian Rees Davies observed, the prince’s personal role in Wales was limited. Chroniclers of the wars scarcely mention him at all. He seems to have preferred to stay in the relative safety of the English border towns and, increasingly, to spend his time in and around London. In 1409 he was appointed constable of Dover Castle and warden of the Cinque Ports but so far no evidence has been found to show that he went to Dover or Calais, the captaincy of which he gained in March 1410. Yet in 1412, the prince was investigated for misappropriating the garrison’s wages. The overall impression formed from the sources is that King Henry IV was slow to let his son have his head, but that, as the prince grew up, his father could not hold him back. It is notable how, once he turned 21, Prince Henry began to build up his own support. Fifty-one new grants of annuities were made in the year following Michaelmas 1407, a big increase on the average for the previous six years of less than ten. Many of Henry’s circle were nonentities, which fans the notion that he associated with unsuitable people. It also seems that he promoted favourites such as Thomas, Earl of Arundel, and Richard Courtenay, whom Henry had appointed as bishop of Norwich after his accession. Comments made by Courtenay in 1415 tell us that Henry suffered from being overweight and in bad health, and that he was of the opinion that there were no decent doctors in England. There’s more evidence for a sickly Prince Henry in his household accounts listing purchases of medicines. These records also suggest that he may have lived beyond his means, partly because of the large payments he made to retainers. Thomas Walsingham speaks of his retinue in 1412 being “larger than any seen before these days”. Intriguingly, too, in 1415 Courtenay observed that Henry had not had sexual relations with any woman since he came to the throne – the implication being that, as the Vita et Gesta suggests, he had been notably promiscuous before his accession. As prince and heir, we would expect Henry to have had a place on the royal council. This was the case from at least the end of 1406, when he was 20. As the medievalist Christopher Allmand observes, Prince Henry attended a good proportion of meetings but was increasingly advancing the interests of key friends and relations – including his father’s half-brother, Henry Beaufort – and challenging the power of the chancellor, Thomas Arundel, archbishop of Canterbury. Indeed, Henry’s growing influence may have contributed to Arundel’s decision to resign from the chancellorship in December 1409. Henry married Katherine of Valois, daughter of Charles VI of France, on 2 June 1420. This painting of 1487 is from the Chroniques de France ou de Saint Denis. (Credit: AKG images)

Henry married Katherine of Valois, daughter of Charles VI of France, on 2 June 1420. This painting of 1487 is from the Chroniques de France ou de Saint Denis. (Credit: AKG images)

Yet, in November 1411, it seems that the prince’s influence over the council abruptly ended. There is no doubt that Henry’s relations with his father, and with his brother, Thomas, were bad: there were major differences of opinion on foreign policy, and a study of diplomatic relations with Burgundy suggests that the prince was making offers he was simply not entitled to issue. He was also outraged not to be chosen to lead an expedition to Aquitaine in the summer of 1412. The seriousness of the situation is reflected in a letter sent by Prince Henry from Coventry on 17 June 1412, a missive that was clearly intended to reach a wide audience. It addressed rumours accusing him of plotting to rebel against his father and seize the throne. Father and son became reconciled but, according to the chronicler Thomas Walsingham, Henry IV refused to punish immediately those who had spread the rumours; instead, he ordered that sanctions should wait until the next parliament, when they could be tried by their peers. This could only mean that the prince’s detractors were noblemen. Interestingly, the Latin lives made much of Henry’s last-minute reform and confession to his father – does this suggest that, despite his protestations, he might have had a guilty conscience? Henry the prince emerges as a complex character: not always living up to expectations, making enemies and choosing unsuitable friends. He was brave but flawed, and always prioritised his own desires. Six centuries after he assumed the throne, it’s worth remembering that the road to his achievement as all-conquering hero of Agincourt was often a rocky one. Professor Anne Curry is the dean of the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Southampton.

Henry V: dithering also-ran or medieval hero? (Credit: Bridgeman Images)

Henry V: dithering also-ran or medieval hero? (Credit: Bridgeman Images) On Friday 25 October 1415, in a muddy field in Picardy, the reputation of Henry V as a great warrior king was sealed. His victory over the French at Agincourt had a major effect on his position both at home and abroad. Even before he returned to England, a grateful parliament had granted him all revenue from customs duties – a sizeable income – for life. As for the French, they never again dared to face him in battle. So Henry was able to conquer the whole of Normandy and advance on Paris, exploiting the divisions in France – between the Burgundian and Armagnac factions – that the defeat at Agincourt had exacerbated. The treaty of Troyes, signed in May 1420, sealed Henry’s acceptance as regent to Charles VI (‘The Mad’) and – through marriage to Charles’s daughter Katherine – heir to the throne of France. It seemed only a matter of time before he would rule over both England and France. At the parliament held at Westminster in December 1420, the chancellor explained why the English had “special cause to honour and thank God” for the deeds and victories of the king. He had recovered the ancient rights of the English crown in France. He had destroyed heresy in the realm – a reference to his actions against Sir John Oldcastle and the Lollards (critics of the established church) in 1414. And, in his youth, he had put down rebellion in Wales. In short, though Henry’s untimely death in 1422 curtailed the fulfilment of his plans, his career was, on the face of it, a complete success. As Thomas Walsingham, author of The St Albans Chronicle, expressed in a panegyric for the dead king: “He was a warrior, famous and blessed with good fortune who, in every war he undertook, always came away with victory.” But had Henry always been so successful? Let us reflect on Henry’s life before he became king.

This 15th-century illustration depicts Henry, then Prince of Wales, paying homage to the French king Charles VI. The Treaty of Troyes, signed in 1420, saw Henry named Charles’s regent; by marrying the latter’s daughter, Katherine, Henry secured his position as heir to the French throne. (Credit: Bridgeman Images)

There are ample reasons to believe that Henry the prince was a far cry from Henry the king. In Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2, Shakespeare portrays him as a medieval ‘hooray Henry’. In those plays, the prince chooses bad company; though wealthy, he prefers the low life and petty criminality; and it is only at his father’s deathbed and his own subsequent coronation that he reforms himself – becoming as excessively ‘correct’ as he was once so ‘incorrect’ for his social and political position. But was this fact as well as Shakespearean fiction? The first ‘published’ comments on Henry’s bad behaviour so far unearthed appear in the Latin lives written about him in the late 1430s. In the anonymous Vita et Gesta Henrici Quinti (often called the Pseudo-Elmham), Henry is described as being in his youth “an assiduous cultivator of lasciviousness…passing the bounds of modesty he was the fervent soldier of Venus as well as Mars; youthlike he was fired by her torches and in the midst of worthy works of war found leisure for excesses common to ungoverned age”. The work devotes much space to his last-minute repentance to his father for his bad behaviour. We could dismiss all of this as simply a good story – except that it was dealt with at great length, and in a work known to have drawn information from one of Henry’s courtiers: Walter, Lord Hungerford. In another work, the Vita Henrici Quinti by Tito Livio Frulovisi (now believed to have been derived from the Vita et Gesta), stories of a misspent youth and late change of heart are shorter, but remain. Given this work’s links with Henry’s last surviving brother, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, and the status of both works as eulogies for Henry V, we have to assume that the accounts of his youth are basically true – as are those of the well-publicised change of character at his accession. There are many intriguing facets to Prince Henry. For one thing, he had not been born to be king. Until just after his 13th birthday, in September 1399, he was merely the eldest son of the eldest son of a collateral line of King Richard II . He stood to inherit, in time, the duchy of Lancaster created for his grandfather John of Gaunt (d1399), the third son of Edward III. He was also to be bequeathed the earldom of Derby held by his father, Henry Bolingbroke (d1413), and the titles brought to the family by his co-heiress mother, Mary (d1394), daughter of Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Northampton, Essex and Hereford (d1373). So the career that lay ahead for the “young lord Henry” or “Lord Henry, son of the Earl of Derby”, as he is described in the financial records of his father and grandfather, was that of a peer – but at the time it seemed that he might have to wait many years for his inheritance.

Tom Mison plays Prince Hal, with David Yelland as the old king, in a performance of Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part I. The play portrays Hal as a medieval ‘hooray Henry’. (Credit: Rex)

Tom Mison plays Prince Hal, with David Yelland as the old king, in a performance of Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part I. The play portrays Hal as a medieval ‘hooray Henry’. (Credit: Rex)As it was, his life was completely transformed – first, in October 1398, by the exile of his father by Richard II; and then, the following September, by Bolingbroke’s return to England and usurpation of the throne as Henry IV. On 15 October 1399, two days after his father’s coronation, Henry was created Prince of Wales, Duke of Cornwall and Earl of Chester, and was acknowledged as heir to the throne. Later in October, the title Duke of Aquitaine was added and, on 10 November, that of Duke of Lancaster. Given the fragile political position of the new dynasty, Prince Henry was a vital cog in its establishment and, as such, shared in its problems – indeed, he experienced them even before the usurpation. In May 1399 the young Henry was taken to Ireland by Richard II , seemingly in an attempt to ensure his father’s good behaviour. It failed: in the king’s absence, Bolingbroke invaded England. Education in armsHenry was then 12 years old, an age at which it was customary for noble boys to begin gaining experience of military service, though they were not expected to actually participate in the fighting. So in the summer of 1400 he was assigned a company of troops within the huge army – over 13,000 strong – that his father took to Scotland. Then, as the army returned to England, the Welsh revolt began. The historian Adam Chapman has observed that it was no coincidence that Owain Glyndŵr declared himself Prince of Wales on 16 September 1400 – the 14th birthday of the formal holder of the title, Prince Henry. Only six months later, the latter found himself involved in his first siege, at Conwy. It is not surprising that the teenage prince learned under the tutelage of advisors appointed by his father. The young Henry held a number of nominal commands but was always guided by others, including Henry Hotspur, son of the Earl of Northumberland, and Hotspur’s uncle, Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester, who was appointed Prince Henry’s governor at the end of 1401. Yet these were the very men who, in 1403, rebelled against Henry IV and his son. So the battle of Shrewsbury on 21 July, when he faced his erstwhile mentors, must have been a chastening experience for the prince – not least because he was wounded by an arrow that pierced his left cheek. The surgeon John Bradmore removed the arrowhead, but the wound put the prince out of action for a year or so. Even as Henry entered his late teens, his father was reluctant to give him complete authority in the Welsh wars. The young prince was neither wholly committed nor effective, and constantly complained of being kept short of funds. Alongside praise for the prince’s good heart and courage, the speaker of the parliament of March 1406 also urged that he should maintaincontinual residence in Wales for the sake of the wars – an indication that he had not been attentive to his duties. All did not go well with the prince’s campaigns. In 1407, at the siege of Aberystwyth, Henry theatrically negotiated its peaceful surrender, withdrawing his troops; Glyndwˆ r, though, simply occupied the castle. Aberystwyth remained in rebel hands until September 1408 and was recovered, as was Harlech in 1409, not by the prince in person but by those to whom he delegated.

This late 15th century illustration shows prisoners being taken at Agincourt. Some of Henry’s earlier military endeavours had not met with such success. (Credit: Alamy)

This late 15th century illustration shows prisoners being taken at Agincourt. Some of Henry’s earlier military endeavours had not met with such success. (Credit: Alamy)Sickly and sexed upAs the late Welsh historian Rees Davies observed, the prince’s personal role in Wales was limited. Chroniclers of the wars scarcely mention him at all. He seems to have preferred to stay in the relative safety of the English border towns and, increasingly, to spend his time in and around London. In 1409 he was appointed constable of Dover Castle and warden of the Cinque Ports but so far no evidence has been found to show that he went to Dover or Calais, the captaincy of which he gained in March 1410. Yet in 1412, the prince was investigated for misappropriating the garrison’s wages. The overall impression formed from the sources is that King Henry IV was slow to let his son have his head, but that, as the prince grew up, his father could not hold him back. It is notable how, once he turned 21, Prince Henry began to build up his own support. Fifty-one new grants of annuities were made in the year following Michaelmas 1407, a big increase on the average for the previous six years of less than ten. Many of Henry’s circle were nonentities, which fans the notion that he associated with unsuitable people. It also seems that he promoted favourites such as Thomas, Earl of Arundel, and Richard Courtenay, whom Henry had appointed as bishop of Norwich after his accession. Comments made by Courtenay in 1415 tell us that Henry suffered from being overweight and in bad health, and that he was of the opinion that there were no decent doctors in England. There’s more evidence for a sickly Prince Henry in his household accounts listing purchases of medicines. These records also suggest that he may have lived beyond his means, partly because of the large payments he made to retainers. Thomas Walsingham speaks of his retinue in 1412 being “larger than any seen before these days”. Intriguingly, too, in 1415 Courtenay observed that Henry had not had sexual relations with any woman since he came to the throne – the implication being that, as the Vita et Gesta suggests, he had been notably promiscuous before his accession. As prince and heir, we would expect Henry to have had a place on the royal council. This was the case from at least the end of 1406, when he was 20. As the medievalist Christopher Allmand observes, Prince Henry attended a good proportion of meetings but was increasingly advancing the interests of key friends and relations – including his father’s half-brother, Henry Beaufort – and challenging the power of the chancellor, Thomas Arundel, archbishop of Canterbury. Indeed, Henry’s growing influence may have contributed to Arundel’s decision to resign from the chancellorship in December 1409.

Henry married Katherine of Valois, daughter of Charles VI of France, on 2 June 1420. This painting of 1487 is from the Chroniques de France ou de Saint Denis. (Credit: AKG images)

Henry married Katherine of Valois, daughter of Charles VI of France, on 2 June 1420. This painting of 1487 is from the Chroniques de France ou de Saint Denis. (Credit: AKG images)Yet, in November 1411, it seems that the prince’s influence over the council abruptly ended. There is no doubt that Henry’s relations with his father, and with his brother, Thomas, were bad: there were major differences of opinion on foreign policy, and a study of diplomatic relations with Burgundy suggests that the prince was making offers he was simply not entitled to issue. He was also outraged not to be chosen to lead an expedition to Aquitaine in the summer of 1412. The seriousness of the situation is reflected in a letter sent by Prince Henry from Coventry on 17 June 1412, a missive that was clearly intended to reach a wide audience. It addressed rumours accusing him of plotting to rebel against his father and seize the throne. Father and son became reconciled but, according to the chronicler Thomas Walsingham, Henry IV refused to punish immediately those who had spread the rumours; instead, he ordered that sanctions should wait until the next parliament, when they could be tried by their peers. This could only mean that the prince’s detractors were noblemen. Interestingly, the Latin lives made much of Henry’s last-minute reform and confession to his father – does this suggest that, despite his protestations, he might have had a guilty conscience? Henry the prince emerges as a complex character: not always living up to expectations, making enemies and choosing unsuitable friends. He was brave but flawed, and always prioritised his own desires. Six centuries after he assumed the throne, it’s worth remembering that the road to his achievement as all-conquering hero of Agincourt was often a rocky one. Professor Anne Curry is the dean of the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Southampton.

Published on April 25, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Pope Leo III attacked in Rome

April 25

799 Pope Leo III was attacked during a procession in Rome due, in part, for recognizing Charlemagne as patricius of the Romans, which upset the delicate balance between the Byzantines and the west that his predecessor had established. He fled to Charlemagne, who escorted the Pope safely back to Rome where he oversaw a commission that vindicated Leo and deported his enemies. Leo would later crown Charlemagne the first Holy Roman Emperor

799 Pope Leo III was attacked during a procession in Rome due, in part, for recognizing Charlemagne as patricius of the Romans, which upset the delicate balance between the Byzantines and the west that his predecessor had established. He fled to Charlemagne, who escorted the Pope safely back to Rome where he oversaw a commission that vindicated Leo and deported his enemies. Leo would later crown Charlemagne the first Holy Roman Emperor

Published on April 25, 2016 01:00

April 24, 2016

Spanish Archaeologists Continue Works to Recover the Elaborate Villa of the Emperor Hadrian

Ancient Origins

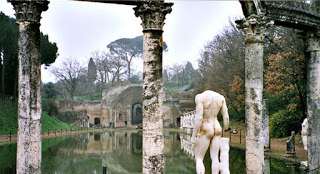

In the second century AD, the Roman Emperor Hadrian ordered the construction of a villa for his personal enjoyment as he was not content in his official palace on Palatine Hill. Located on the outskirts of Tivoli, Rome, Hadrian’s villa was actually a small town – complete with palaces, fountains, baths, and a number of buildings that imitated the different architectural styles of the Egyptians and Greeks. Now, a team of Spanish archaeologists has been excavating the site to determine the distribution of the various elements that made up Hadrian’s villa (Villa Adriana in Italian).

According to information published by the Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia , the team is a group of experts consisting of archaeologists, researchers, and students of the University Pablo de Olavide (UPO) in Seville, who have been involved in the excavations of Hadrian’s villa since 2003. With a total of 120 hectares to study, this season of excavations will focus on the area of the Palazzo.

Imperial palace of the Villa Adriana, Tivoli. (

Public Domain

)"We are in a central area of the villa, in a significant area of the villa, because it is the first residential building constructed by the Emperor Hadrian in the Villa Adriana. The area 'Palazzo' has many problems and it is not yet understood, there are many doubts about many interpretive aspects of this sector of the villa that we intend to solve with our project,” said the director of the project and professor of Archaeology at UPO, Rafael Hidalgo .

Imperial palace of the Villa Adriana, Tivoli. (

Public Domain

)"We are in a central area of the villa, in a significant area of the villa, because it is the first residential building constructed by the Emperor Hadrian in the Villa Adriana. The area 'Palazzo' has many problems and it is not yet understood, there are many doubts about many interpretive aspects of this sector of the villa that we intend to solve with our project,” said the director of the project and professor of Archaeology at UPO, Rafael Hidalgo .The Mighty Wall of Hadrian, Emperor of Rome Archaeologists discover hidden slave tunnel beneath Hadrian’s Villa Throughout the 13 years of fieldwork, they have found that there were originally three courtyards with wooden floors, marble walls of different colors in the imperial residence and, although most of the decoration was plundered, there are still some remnants which clearly show Hadrian’s passion for ostentation and luxury.

"Playing with pieces of marble that we finding in excavations, we can reconstruct what all this was before it was sacked. We know that these spaces were decorated with marble, both the floor and the walls," Rafael Hidalgo told La Vanguardia.

Black and white mosaic pavement; on the background wall: traces of frescoes and of opus reticulatum. From the Hospitalia at the Villa Adriana in Tivoli. (

Public Domain

)To date, one of the most important discoveries that the Spanish experts have brought to light in the area of the "Palazzo", has been the oldest known Roman 'stibadium' (banquet hall) - a room that became fashionable during the Roman empire, although its origin is much older.

Black and white mosaic pavement; on the background wall: traces of frescoes and of opus reticulatum. From the Hospitalia at the Villa Adriana in Tivoli. (

Public Domain

)To date, one of the most important discoveries that the Spanish experts have brought to light in the area of the "Palazzo", has been the oldest known Roman 'stibadium' (banquet hall) - a room that became fashionable during the Roman empire, although its origin is much older. They were also able to confirm that there were a number of indoor rooms in the residential palace, exclusively for the use of the emperor, that open onto a central courtyard. There was a great fountain with two individual latrines on the sides as well.

Ancient tablet dedicated to Emperor Hadrian may explain mystery of Jewish revolt Marcus Aurelius: Life of the Famous Roman Emperor and Philosopher “The individual latrine is a very important feature of the Villa Adriana because the use of latrines in the Roman world did not have the same concept of privacy that we have today, so it is very unusual that a Roman building has a latrine with a single seat” Hidalgo explained to La Vanguardia.

Finally, the palace was also found to have housed, as expected, a "garden terrace", which in turn flowed into a large porch.

The UPO team during excavation work in the 'stibadium.’ (www.upo.es) Featured Image: Canopus of Hadrian’s Villa. (

Public Domain

)

The UPO team during excavation work in the 'stibadium.’ (www.upo.es) Featured Image: Canopus of Hadrian’s Villa. (

Public Domain

)By Mariló T. A.

This article was first published in Spanish at http://www.ancient-origins.es and has been translated with permission.

Published on April 24, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Saint Wilfrid dies

April 24

709 Saint Wilfrid died. A monk of Lindisfarne Abbey and later Bishop of Hexham, Wilfrid spread the Benedictine Rule and worked to establish Roman Catholicism over the influence of the Celtic Church in England.

709 Saint Wilfrid died. A monk of Lindisfarne Abbey and later Bishop of Hexham, Wilfrid spread the Benedictine Rule and worked to establish Roman Catholicism over the influence of the Celtic Church in England.

Published on April 24, 2016 01:30

April 23, 2016

Viking Invaders Struck Deep into the West of England – and May have Stuck Around

Ancient Origins

It’s well chronicled that wave after wave of Vikings from Scandinavia terrorised western Europe for 250 years from the end of the eighth century AD and wreaked particular havoc across vast areas of northern England. There’s no shortage of evidence of Viking raids from the Church historians of the time. But researchers are now uncovering evidence that the Vikings conquered more of the British Isles than was previously thought

At the time England consisted of four independent kingdoms: Wessex, to the south of the River Thames, and Mercia, East Anglia and Northumbria to the north of it. The latter three were all conquered by Scandinavian armies in the late ninth century and their kings killed or deposed – which allowed expansive Scandinavian settlement in eastern and northern England. However the kings of Wessex successfully defended their territory from the Viking intruders (and eventually went on to conquer the North, creating the unified kingdom of England).

Un-united Kingdoms, Mike Christie (

Public Domain

)But precisely because Wessex remained independent, there has never been much examination of Scandinavian influence in that part of the United Kingdom. But we’re beginning to get a different picture suggesting that Viking leaders such as Svein and his son Knut were active as far south as Devon and Cornwall in the West Country.

Un-united Kingdoms, Mike Christie (

Public Domain

)But precisely because Wessex remained independent, there has never been much examination of Scandinavian influence in that part of the United Kingdom. But we’re beginning to get a different picture suggesting that Viking leaders such as Svein and his son Knut were active as far south as Devon and Cornwall in the West Country.

Exposing the Roots of the Viking Horned Helmet MythDiscovery of Reindeer Antlers in Denmark may Rewrite Start of Viking AgeIn 838AD, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded a battle fought at Hingston Down in east Cornwall in which the local Britons joined forces with the Vikings against King Egbert of Wessex and his attempts to expand his kingdom. The fiercely independent Cornish appear to have held out against West Saxon control and presumably cast around for a strong ally in their fight. But why were Viking leaders interested in aiding the Cornish? Perhaps it was a political move, made in the hope of gaining a foothold in the peninsula in order to use it as a strategic base against Wessex. If so, it was thwarted, as the allied army was soundly defeated.

There are also records of raids for plunder in the West Country. A Viking fleet sailed up the river Tamar in 997, attacked the abbey at Tavistock and brought back treasure to their ships.

Cardinham churchyard. Len Williams, (

CC BY-SA 2.0

)There is further evidence indicating Scandinavians in the West Country in a close examination of stone sculptures in Devon and Cornwall which has revealed Scandinavian art motifs and monument forms. A Norwegian Borre ring chain ornament decorates the cross in Cardinham churchyard in east Cornwall and a mounted warrior is in one of the panels of the Copplestone Cross near Crediton, mid Devon. Both are matched by examples in northern England in the Viking Age, but seem out of place in the West. Late versions of the “hogback” memorial stones, which have a pronounced ridge and look like a small stone long house, are well known in Cornwall too – the best example is at Lanivet near Bodmin.

Cardinham churchyard. Len Williams, (

CC BY-SA 2.0

)There is further evidence indicating Scandinavians in the West Country in a close examination of stone sculptures in Devon and Cornwall which has revealed Scandinavian art motifs and monument forms. A Norwegian Borre ring chain ornament decorates the cross in Cardinham churchyard in east Cornwall and a mounted warrior is in one of the panels of the Copplestone Cross near Crediton, mid Devon. Both are matched by examples in northern England in the Viking Age, but seem out of place in the West. Late versions of the “hogback” memorial stones, which have a pronounced ridge and look like a small stone long house, are well known in Cornwall too – the best example is at Lanivet near Bodmin.

These sort of memorials were popular with the Norse settlers in Cumbria and Yorkshire and may be the work of itinerant sculptors bringing new ideas into the West, or patrons ordering forms and patterns which they had seen elsewhere. However, the possibility that the patrons may have been Scandinavian settlers cannot be excluded.

All in the namePeople with Scandinavian names such as Carla, Thurgod, Cytel, Scula, Wicing, Farman are recorded as working in the mints in Exeter and at other Devon sites from the end of the tenth century – and, although such names became popular in the general population, there is an unusual concentration in these areas. Detectorists operating in the West Country are finding increasing numbers of metal objects from the period, many with Scandinavian connections. Scandinavian dress-fittings, lead weights, coins and silver ingots – and all manner of gear for horses have been identified in the past few years. A woman’s trefoil brooch, probably made in Scandinavia, was discovered where it had been dropped in Wiltshire. This is the only example of the type yet found in Wessex, whereas 15 have been discovered in northern England.

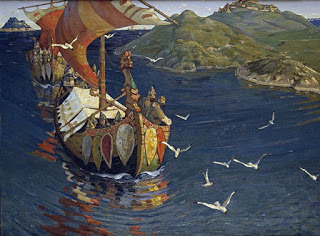

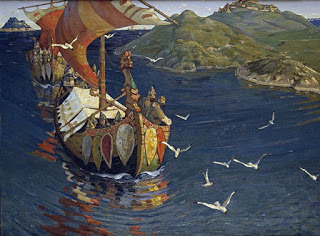

Sword of Late Viking Age Burial Unveiled Exhibiting Links Between Norway and EnglandAncient Route of Famous Anglo-Viking Battle Unearthed in EnglandLike these Viking artefacts, place names with Scandinavian links are well known in northern England – but we would not have previously expected them in the West Country. Yet the islands in the Bristol Channel: Lundy, Steepholm and Flatholme are hybrid names with Old Norse and Old English elements. Spaxton in Somerset was Spacheston in the Domesday Book, that is Spakr’s tun another hybrid. Knowstone in central Devon, recorded as Chenutdestana in Domesday Book, combines Scandinavian Knut with English stana to give Knut’s stone, perhaps named after the Danish king. More intriguing still are the 11 landholders in the Devon section of the Domesday Book with the personal name wichin which means “viking”. These names are rare in England and do not occur at all elsewhere in the West Country, so the cluster in Devon is significant. A combination of sculptural, archaeological and word usage evidence therefore points to a new appreciation of how far the Vikings travelled within the UK – and the dramatic reach of their influence. Featured image: Guests from Overseas, Nicholas Roerich (1899) (Public Domain) The article ‘Viking invaders struck deep into the west of England – and may have stuck around‘ by Derek Gore was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license. -

It’s well chronicled that wave after wave of Vikings from Scandinavia terrorised western Europe for 250 years from the end of the eighth century AD and wreaked particular havoc across vast areas of northern England. There’s no shortage of evidence of Viking raids from the Church historians of the time. But researchers are now uncovering evidence that the Vikings conquered more of the British Isles than was previously thought

At the time England consisted of four independent kingdoms: Wessex, to the south of the River Thames, and Mercia, East Anglia and Northumbria to the north of it. The latter three were all conquered by Scandinavian armies in the late ninth century and their kings killed or deposed – which allowed expansive Scandinavian settlement in eastern and northern England. However the kings of Wessex successfully defended their territory from the Viking intruders (and eventually went on to conquer the North, creating the unified kingdom of England).

Un-united Kingdoms, Mike Christie (

Public Domain

)But precisely because Wessex remained independent, there has never been much examination of Scandinavian influence in that part of the United Kingdom. But we’re beginning to get a different picture suggesting that Viking leaders such as Svein and his son Knut were active as far south as Devon and Cornwall in the West Country.

Un-united Kingdoms, Mike Christie (

Public Domain