MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 102

May 8, 2016

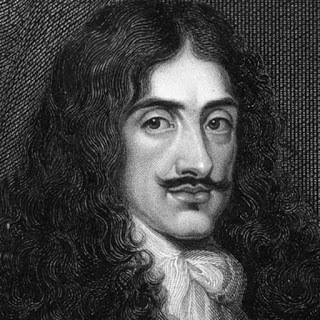

History Trivia - Charles II proclaimed King of England

May 8

1660 Parliament proclaimed Charles II king of England, restoring the monarchy after more than a decade.

1660 Parliament proclaimed Charles II king of England, restoring the monarchy after more than a decade.

Published on May 08, 2016 02:00

May 7, 2016

Star Wars: why did the film make history?

History Extra

Peter Mayhew, Harrison Ford, Alec Guinness and Mark Hamill, on-set of the film Star Wars, 1977. © Glasshouse Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Peter Mayhew, Harrison Ford, Alec Guinness and Mark Hamill, on-set of the film Star Wars, 1977. © Glasshouse Images/Alamy Stock Photo

There is a moment in the first Star Wars film when the mystic Obi Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness) detects across at great distance of space the destruction of a planet and remarks: “I felt a great disturbance in the Force… as if as if millions of voices suddenly cried out in terror and were suddenly silenced.”

The release of the seventh installment of the Star Wars saga today therefore prompts the question of exactly what the particular “disturbance in the Force” associated with the release of the first film in the series back in May 1977 might mean historically. What does it say about the time in which it was made and the people who so took it to their hearts? And what does the ongoing success of the franchise say about us?

At one level, Star Wars was – and is – a commercial commodity: a milestone in the evolution of the film industry. Its creator, George Lucas, demonstrated that films could be made for families; that spectacular effects could help film to claw back some territory from the small-screen entertainment; and profits could be swollen to astonishing proportions though tie-in merchandise.

Other films of the era attempted similar synergies, but there was plainly something about Star Wars that struck a particular chord. Reports of initial audiences in the US stressed how hungry they seemed for what Star Wars offered: the film was fundamentally not like so many other elements of the culture in which it landed – a world that was only too happy to embrace the film’s escapism because it had so much that it wished to escape from.

For the initial audiences in America and beyond, the experience of viewing Star Wars was a curious mixture of watching something completely new and something incredibly familiar. It was a paradox, illustrated in the film’s opening declaration that it was set “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away”.

The familiar components in the film were the incorporation of multiple elements of beloved genres that were out of step with the cynical post-Watergate, post-Vietnam War, energy crisis world of the mid-1970s. Star Wars’ abstract and distant location with absolutely no point of reference to humanity or earth culture enabled favourite tropes of the screen to be revisited without the necessity of apology or self-examination or of any danger of alienating a nationality or ethnic group at home or abroad.

Star Wars was the product of and for an American society yearning to be free of its own bonds of history and be good again. It was the perfect transferable product in which everyone could find themselves, not just within the US, but worldwide. It helped that the film’s heroic structure was borrowed from the myths common to all human cultures: Star Wars recovered the energy and zest of the old Flash Gordon serials; it borrowed characters and settings from the classic western, which by the 1970s was burdened in its explicit form by America’s awareness of the moral ugliness of the historical reality.

Star Wars’ location allowed much play and humour at the expense of ethnic and racial differences that would have been impossible (and tasteless) in the wake of the Civil Rights movement. Various characters seemed to fill the role of the ethnic ‘other’: the droids experience segregation in the bar scene, and Chewbacca is cast as a noble, ethnic side-kick, providing heroic support and comic relief.

Peter Mayhew as Chewbacca and Harrison Ford as Han Solo in Star Wars, 1977. © Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

Two genres had particular significance within Star Wars: the war film and the religious epic. Star Wars enabled the representation of a war without having to worry about that war’s consequences; the merits of its antagonists; or that any participant might be offended. Much of it channelled the Second World War with Imperial uniforms and the terminology of Storm Troopers borrowed from the Third Reich; however, it was also swiftly noticed that in Star Wars a country that had just been defeated by an army of guerillas was able to happily identify with a rebel alliance. So, much of the film’s look could be borrowed from Asia, in particular the Vietnam War, without audiences having to recall who firebombed Tokyo or dropped Agent Orange on the Ho Chi Minh trail.

The elements of Star Wars lifted from religious epics functioned in much the same way: the film recovered a genre that had been an immense part of 20th-century cinema, reaching its apogee in the late fifties with wildly successful films like The Ten Commandments or Ben-Hur (its chariot race scene was the model for the pod-race in Episode I: The Phantom Menace). By creating its universe of right and wrong, and its religion of The Force, George Lucas was able to tell an essentially religious story of awakening, sacrifice, temptation and redemption, and it so doing he could touch his viewers’ sense of wonder and the infinite. The setting in space enabled maximum engagement with minimal alienation, and enabled visual wonders every bit as impressive as the parting of the Red Sea.

Overall, then, in 1977 Star Wars was a mechanism to culturally have your cake and eat it at a time of great uncertainty in America and the west. It allowed its viewer to luxuriate in the triumphalism, ethnic voyeurism and religiosity without apology.

Of course, it didn’t take long for people in America and many other parts of the world to outgrow the uncertainty of mid 1970s; to trade Jimmy Carter for Ronald Reagan or James Callaghan for Margaret Thatcher, and reconnect with the self-confidence that allowed triumphalism, ethnocentrism and religiosity to flourish openly.

It turned out that audiences weren’t too alienated anyway. The Rambo cycle had the political sensitivity of a sledgehammer and did well around the world. By the time the original trilogy was re-released in the late 1990s (with up-dated effects), the Second World War’s Allied victory was a cause for celebration again, and did not have to be evoked by proxy.

In the meantime, Star Wars itself had become a cultural reference point: Ronald Reagan could tap into its language when he called Russia an ‘evil empire’; Ted Kennedy did the same when he dubbed Reagan’s pet strategic defense initiative the ‘Star Wars program’; and the Oklahoma City bomber, Tim McVeigh, compared himself to Luke Skywalker destroying the Death Star. In the end, the cultural phenomenon struck back. Comments on the decline of democracy and evils of “with us or against us” language in the script for Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, were unmistakable barbs from the liberal Lucas aimed at the George W Bush administration.

Looking back, it is plain that in its nearly 40-year (and counting) career, the Star Wars franchise has evolved. The films still turn on a twin drive to escape and to remember, but the direction of the remembrance has changed. In the beginning, audiences were remembering a film culture that had become unfashionable or untenable. Today we watch Star Wars to remember Star Wars. Given that the need for both remembrance and escapism remains undiminished, the new films should do very well indeed.

Nicholas John Cull is Professor of Communication at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School. He is the author (with James Chapman) of Projecting Tomorrow: Science Fiction and Popular Cinema (I B Tauris, 2012) which includes an extended discussion of the making and reception of Star Wars. To find out more, click here.

Peter Mayhew, Harrison Ford, Alec Guinness and Mark Hamill, on-set of the film Star Wars, 1977. © Glasshouse Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Peter Mayhew, Harrison Ford, Alec Guinness and Mark Hamill, on-set of the film Star Wars, 1977. © Glasshouse Images/Alamy Stock Photo There is a moment in the first Star Wars film when the mystic Obi Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness) detects across at great distance of space the destruction of a planet and remarks: “I felt a great disturbance in the Force… as if as if millions of voices suddenly cried out in terror and were suddenly silenced.”

The release of the seventh installment of the Star Wars saga today therefore prompts the question of exactly what the particular “disturbance in the Force” associated with the release of the first film in the series back in May 1977 might mean historically. What does it say about the time in which it was made and the people who so took it to their hearts? And what does the ongoing success of the franchise say about us?

At one level, Star Wars was – and is – a commercial commodity: a milestone in the evolution of the film industry. Its creator, George Lucas, demonstrated that films could be made for families; that spectacular effects could help film to claw back some territory from the small-screen entertainment; and profits could be swollen to astonishing proportions though tie-in merchandise.

Other films of the era attempted similar synergies, but there was plainly something about Star Wars that struck a particular chord. Reports of initial audiences in the US stressed how hungry they seemed for what Star Wars offered: the film was fundamentally not like so many other elements of the culture in which it landed – a world that was only too happy to embrace the film’s escapism because it had so much that it wished to escape from.

For the initial audiences in America and beyond, the experience of viewing Star Wars was a curious mixture of watching something completely new and something incredibly familiar. It was a paradox, illustrated in the film’s opening declaration that it was set “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away”.

The familiar components in the film were the incorporation of multiple elements of beloved genres that were out of step with the cynical post-Watergate, post-Vietnam War, energy crisis world of the mid-1970s. Star Wars’ abstract and distant location with absolutely no point of reference to humanity or earth culture enabled favourite tropes of the screen to be revisited without the necessity of apology or self-examination or of any danger of alienating a nationality or ethnic group at home or abroad.

Star Wars was the product of and for an American society yearning to be free of its own bonds of history and be good again. It was the perfect transferable product in which everyone could find themselves, not just within the US, but worldwide. It helped that the film’s heroic structure was borrowed from the myths common to all human cultures: Star Wars recovered the energy and zest of the old Flash Gordon serials; it borrowed characters and settings from the classic western, which by the 1970s was burdened in its explicit form by America’s awareness of the moral ugliness of the historical reality.

Star Wars’ location allowed much play and humour at the expense of ethnic and racial differences that would have been impossible (and tasteless) in the wake of the Civil Rights movement. Various characters seemed to fill the role of the ethnic ‘other’: the droids experience segregation in the bar scene, and Chewbacca is cast as a noble, ethnic side-kick, providing heroic support and comic relief.

Peter Mayhew as Chewbacca and Harrison Ford as Han Solo in Star Wars, 1977. © Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

Two genres had particular significance within Star Wars: the war film and the religious epic. Star Wars enabled the representation of a war without having to worry about that war’s consequences; the merits of its antagonists; or that any participant might be offended. Much of it channelled the Second World War with Imperial uniforms and the terminology of Storm Troopers borrowed from the Third Reich; however, it was also swiftly noticed that in Star Wars a country that had just been defeated by an army of guerillas was able to happily identify with a rebel alliance. So, much of the film’s look could be borrowed from Asia, in particular the Vietnam War, without audiences having to recall who firebombed Tokyo or dropped Agent Orange on the Ho Chi Minh trail.

The elements of Star Wars lifted from religious epics functioned in much the same way: the film recovered a genre that had been an immense part of 20th-century cinema, reaching its apogee in the late fifties with wildly successful films like The Ten Commandments or Ben-Hur (its chariot race scene was the model for the pod-race in Episode I: The Phantom Menace). By creating its universe of right and wrong, and its religion of The Force, George Lucas was able to tell an essentially religious story of awakening, sacrifice, temptation and redemption, and it so doing he could touch his viewers’ sense of wonder and the infinite. The setting in space enabled maximum engagement with minimal alienation, and enabled visual wonders every bit as impressive as the parting of the Red Sea.

Overall, then, in 1977 Star Wars was a mechanism to culturally have your cake and eat it at a time of great uncertainty in America and the west. It allowed its viewer to luxuriate in the triumphalism, ethnic voyeurism and religiosity without apology.

Of course, it didn’t take long for people in America and many other parts of the world to outgrow the uncertainty of mid 1970s; to trade Jimmy Carter for Ronald Reagan or James Callaghan for Margaret Thatcher, and reconnect with the self-confidence that allowed triumphalism, ethnocentrism and religiosity to flourish openly.

It turned out that audiences weren’t too alienated anyway. The Rambo cycle had the political sensitivity of a sledgehammer and did well around the world. By the time the original trilogy was re-released in the late 1990s (with up-dated effects), the Second World War’s Allied victory was a cause for celebration again, and did not have to be evoked by proxy.

In the meantime, Star Wars itself had become a cultural reference point: Ronald Reagan could tap into its language when he called Russia an ‘evil empire’; Ted Kennedy did the same when he dubbed Reagan’s pet strategic defense initiative the ‘Star Wars program’; and the Oklahoma City bomber, Tim McVeigh, compared himself to Luke Skywalker destroying the Death Star. In the end, the cultural phenomenon struck back. Comments on the decline of democracy and evils of “with us or against us” language in the script for Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, were unmistakable barbs from the liberal Lucas aimed at the George W Bush administration.

Looking back, it is plain that in its nearly 40-year (and counting) career, the Star Wars franchise has evolved. The films still turn on a twin drive to escape and to remember, but the direction of the remembrance has changed. In the beginning, audiences were remembering a film culture that had become unfashionable or untenable. Today we watch Star Wars to remember Star Wars. Given that the need for both remembrance and escapism remains undiminished, the new films should do very well indeed.

Nicholas John Cull is Professor of Communication at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School. He is the author (with James Chapman) of Projecting Tomorrow: Science Fiction and Popular Cinema (I B Tauris, 2012) which includes an extended discussion of the making and reception of Star Wars. To find out more, click here.

Published on May 07, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Charles University in Prague founded

May 7

1348 Charles University in Prague (Universitas Carolina/Univerzita Karlova) was established as the first university in Central Europe

1348 Charles University in Prague (Universitas Carolina/Univerzita Karlova) was established as the first university in Central Europe

Published on May 07, 2016 02:00

May 6, 2016

New Interpretation of the Rok Runestone Inscription Changes View of Viking Age

Ancient Origins

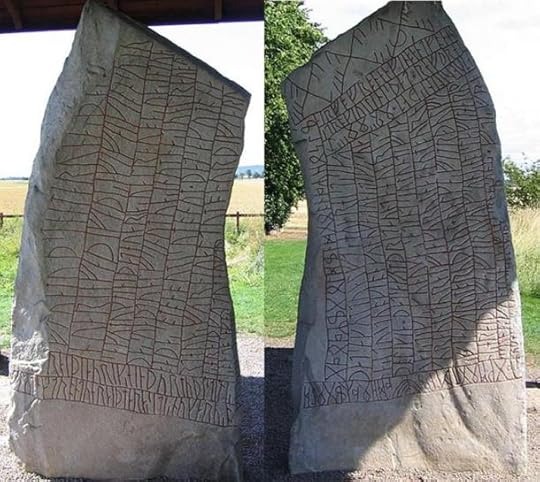

The Rök Runestone, erected in the late 800s in the Swedish province of Östergötland, is the world's most well-known runestone. Its long inscription has seemed impossible to understand, despite the fact that it is relatively easy to read. A new interpretation of the inscription has now been presented -- an interpretation that breaks completely with a century-old interpretative tradition. What has previously been understood as references to heroic feats, kings and wars in fact seems to refer to the monument itself.

'The inscription on the Rök Runestone is not as hard to understand as previously thought,' says Per Holmberg, associate professor of Scandinavian languages at the University of Gothenburg. 'The riddles on the front of the stone have to do with the daylight that we need to be able to read the runes, and on the back are riddles that probably have to do with the carving of the runes and the runic alphabet, the so called futhark.'

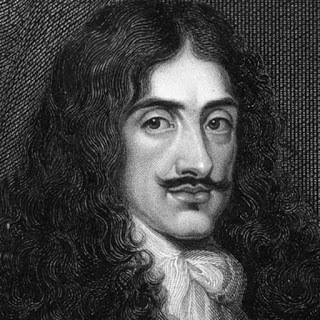

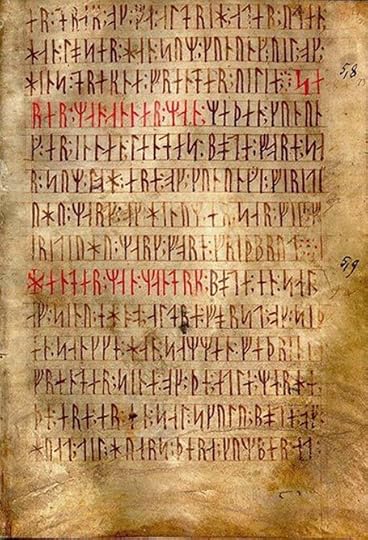

Codex runicus, a vellum manuscript from c. 1300 containing one of the oldest and best preserved texts of the Scanian law (Skånske lov), written entirely in runes. ( Public Domain )Previous research has treated the Rök Runestone as a unique runestone that gives accounts of long forgotten acts of heroism. This understanding has sparked speculations about how Varin, who made the inscriptions on the stone, was related to Gothic kings. In his research, Holmberg shows that the Rök Runestone can be understood as more similar to other runestones from the Viking Age. In most cases, runestone inscriptions say something about themselves.

Codex runicus, a vellum manuscript from c. 1300 containing one of the oldest and best preserved texts of the Scanian law (Skånske lov), written entirely in runes. ( Public Domain )Previous research has treated the Rök Runestone as a unique runestone that gives accounts of long forgotten acts of heroism. This understanding has sparked speculations about how Varin, who made the inscriptions on the stone, was related to Gothic kings. In his research, Holmberg shows that the Rök Runestone can be understood as more similar to other runestones from the Viking Age. In most cases, runestone inscriptions say something about themselves.

'Already 10 years ago, the linguist Professor Bo Ralph proposed that the old idea that the Rök Runestone says mentions the Gothic emperor Theodoric is based on a minor reading error and a major portion of nationalistic wishful thinking. What has been missing is an interpretation of the whole inscription that is unaffected by such fantasies.'

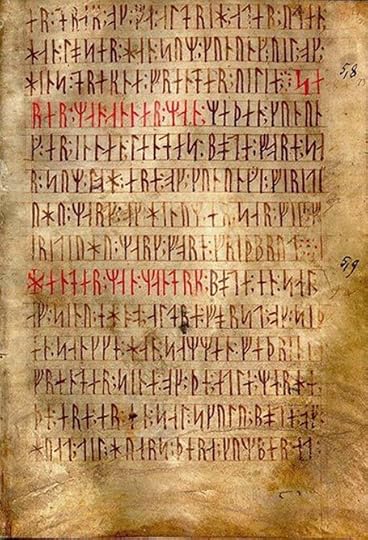

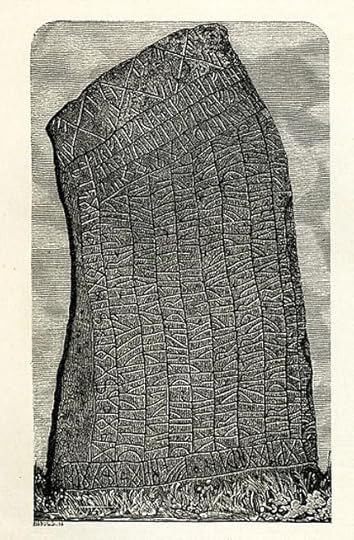

An 1877 image of the Rök runestone from Östergötland, Sweden. ( Public Domain )Holmberg's study is based on social semiotics, a theory about how language is a potential for realizing meaning in different types of texts and contexts.

An 1877 image of the Rök runestone from Östergötland, Sweden. ( Public Domain )Holmberg's study is based on social semiotics, a theory about how language is a potential for realizing meaning in different types of texts and contexts.

The Kensington Runestone & Other Out Of Place Artifacts In America Tracing the Paths of the Vikings Through Their Graffiti The true meaning of Paganism 'Without a modern text theory, it would not have been possible to explore which meanings are the most important for runestones. Nor would it have been possible to test the hypothesis that the Rök Runestone expresses similar meanings as other runestones, despite the fact that its inscription is unusually long.'

One feature of the Rök Runestone that researchers have struggled with is that its inscription begins by listing in numerical order what it wants the reader to guess ('Secondly, say who...'), but then seems to skip all the way to 'twelfth, ...'. Previous research has assumed there was an oral version of the message that included the missing nine riddles. Holmberg reaches a surprising conclusion:

'If you let the inscription lead you step by step around the stone, the twelfth actually appears as the twelfth thing the reader is supposed to consider. It's not the inscription that skips over something. It's the researchers that have taken a wrong way through the inscription, in order to make it be about heroic deeds.'

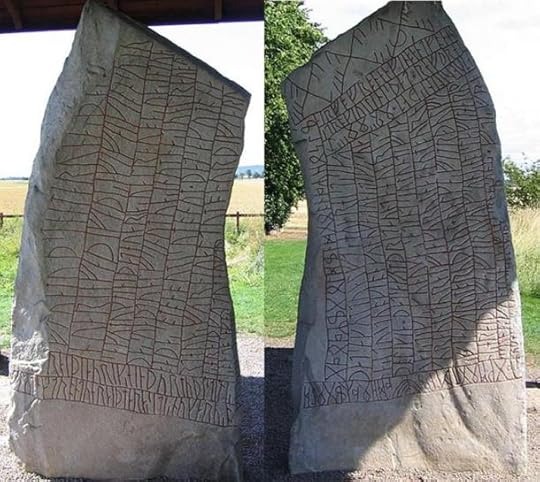

The Front ( CC BY SA 3.0 ) and Back ( CC BY SA 3.0 ) of the Rök runestone. For over a century, the traditional interpretation has contributed to our understanding of the Viking Age. With the new interpretation, the Rök Runestone does not carry a message of honour and vengeance. Instead the message concerns how the technology of writing gives us an opportunity to commemorate those who have passed away.

The Front ( CC BY SA 3.0 ) and Back ( CC BY SA 3.0 ) of the Rök runestone. For over a century, the traditional interpretation has contributed to our understanding of the Viking Age. With the new interpretation, the Rök Runestone does not carry a message of honour and vengeance. Instead the message concerns how the technology of writing gives us an opportunity to commemorate those who have passed away.

Featured Image: The Rök Runestone in Rök, Sweden. Source: CC BY SA 3.0

The article ‘ New interpretation of the Rök runestone inscription changes view of Viking Age.’ was originally published on Science Daily.

Source: University of Gothenburg. "New interpretation of the Rök runestone inscription changes view of Viking Age." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 2 May 2016.

The Rök Runestone, erected in the late 800s in the Swedish province of Östergötland, is the world's most well-known runestone. Its long inscription has seemed impossible to understand, despite the fact that it is relatively easy to read. A new interpretation of the inscription has now been presented -- an interpretation that breaks completely with a century-old interpretative tradition. What has previously been understood as references to heroic feats, kings and wars in fact seems to refer to the monument itself.

'The inscription on the Rök Runestone is not as hard to understand as previously thought,' says Per Holmberg, associate professor of Scandinavian languages at the University of Gothenburg. 'The riddles on the front of the stone have to do with the daylight that we need to be able to read the runes, and on the back are riddles that probably have to do with the carving of the runes and the runic alphabet, the so called futhark.'

Codex runicus, a vellum manuscript from c. 1300 containing one of the oldest and best preserved texts of the Scanian law (Skånske lov), written entirely in runes. ( Public Domain )Previous research has treated the Rök Runestone as a unique runestone that gives accounts of long forgotten acts of heroism. This understanding has sparked speculations about how Varin, who made the inscriptions on the stone, was related to Gothic kings. In his research, Holmberg shows that the Rök Runestone can be understood as more similar to other runestones from the Viking Age. In most cases, runestone inscriptions say something about themselves.

Codex runicus, a vellum manuscript from c. 1300 containing one of the oldest and best preserved texts of the Scanian law (Skånske lov), written entirely in runes. ( Public Domain )Previous research has treated the Rök Runestone as a unique runestone that gives accounts of long forgotten acts of heroism. This understanding has sparked speculations about how Varin, who made the inscriptions on the stone, was related to Gothic kings. In his research, Holmberg shows that the Rök Runestone can be understood as more similar to other runestones from the Viking Age. In most cases, runestone inscriptions say something about themselves. 'Already 10 years ago, the linguist Professor Bo Ralph proposed that the old idea that the Rök Runestone says mentions the Gothic emperor Theodoric is based on a minor reading error and a major portion of nationalistic wishful thinking. What has been missing is an interpretation of the whole inscription that is unaffected by such fantasies.'

An 1877 image of the Rök runestone from Östergötland, Sweden. ( Public Domain )Holmberg's study is based on social semiotics, a theory about how language is a potential for realizing meaning in different types of texts and contexts.

An 1877 image of the Rök runestone from Östergötland, Sweden. ( Public Domain )Holmberg's study is based on social semiotics, a theory about how language is a potential for realizing meaning in different types of texts and contexts. The Kensington Runestone & Other Out Of Place Artifacts In America Tracing the Paths of the Vikings Through Their Graffiti The true meaning of Paganism 'Without a modern text theory, it would not have been possible to explore which meanings are the most important for runestones. Nor would it have been possible to test the hypothesis that the Rök Runestone expresses similar meanings as other runestones, despite the fact that its inscription is unusually long.'

One feature of the Rök Runestone that researchers have struggled with is that its inscription begins by listing in numerical order what it wants the reader to guess ('Secondly, say who...'), but then seems to skip all the way to 'twelfth, ...'. Previous research has assumed there was an oral version of the message that included the missing nine riddles. Holmberg reaches a surprising conclusion:

'If you let the inscription lead you step by step around the stone, the twelfth actually appears as the twelfth thing the reader is supposed to consider. It's not the inscription that skips over something. It's the researchers that have taken a wrong way through the inscription, in order to make it be about heroic deeds.'

The Front ( CC BY SA 3.0 ) and Back ( CC BY SA 3.0 ) of the Rök runestone. For over a century, the traditional interpretation has contributed to our understanding of the Viking Age. With the new interpretation, the Rök Runestone does not carry a message of honour and vengeance. Instead the message concerns how the technology of writing gives us an opportunity to commemorate those who have passed away.

The Front ( CC BY SA 3.0 ) and Back ( CC BY SA 3.0 ) of the Rök runestone. For over a century, the traditional interpretation has contributed to our understanding of the Viking Age. With the new interpretation, the Rök Runestone does not carry a message of honour and vengeance. Instead the message concerns how the technology of writing gives us an opportunity to commemorate those who have passed away. Featured Image: The Rök Runestone in Rök, Sweden. Source: CC BY SA 3.0

The article ‘ New interpretation of the Rök runestone inscription changes view of Viking Age.’ was originally published on Science Daily.

Source: University of Gothenburg. "New interpretation of the Rök runestone inscription changes view of Viking Age." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 2 May 2016.

Published on May 06, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Spanish and German troops sack Rome

Published on May 06, 2016 02:00

May 5, 2016

Rome Reopens its Historical Imperial Port to the Public

Ancient Origins

Roman rule meant the control of Rome on ports and marine and land trade routes. In fact, Roman maritime commercial traffic was so important that they improved and expanded existing land routes, creating a vast road network in many regions, which was in service until the 18th century. This allowed them to develop and consolidate areas of commercial influence on some ports - transforming them into centers for very important economic activity.

Now, according to reports in the Spanish publication El Diario , the archaeological remains of the imperial port of Claudius and Trajan has just reopened to the public, and will be accesible for at least six months of this year.

The history of this great port complex started around the year 100 AD, when Rome’s high population of close to a million and a half inhabitants - equivalent to a current concentration of 50 million people, demanded an infrastructure that could ensure sufficient supplies.

The port of Rome built about 2,000 years ago was the most important center of ancient world operations for nearly half a millennium. It was the place for transiting goods from the ends of the earth to supply the entire empire with Greek wines, Andalusian oils, Egyptian cereals, textiles, metals, and wild animals for circuses. In addition, it also served as a defensive base for the ships of the Imperial Navy and as a starting point for their many military campaigns.

Digital recreation of the ancient imperial port of Rome. ( Listín Diario )Once in port, all the goods were deposited in the port warehouses, which today form the best preserved part of the site and attest to the measurement system used and the distribution of the products. Halls and courtyards of its foundations, where ancient deals took place, still remain as well.

Different products were transferred to smaller ships that were responsible for distributing them via the Tiber River through a complex system of canals. These canals managed to save ships from the inconvenience that the Mediterranean was, as a sea which basically was only sailed in summer - just when the flow of the Tiber river declined considerably.

As indicated by the information published by the Listín Diario , an understanding of the functioning and structures of this great site requires an intense exercise in imagination today because where the sea was before, today there is an immense park lined with eucalyptus, pine, and oak trees: the sediment caused the waterfront to gain about four kilometers (2.49 miles) of the sea, and during the first decades of the 20th century the area was reclassified and finally turned into a nature reserve.

Marks can still be seen on the walls where water emerged in some areas near the old docks. The location of the piers is also easy to guess as several flights of stairs and bollards for mooring boats still stand.

Researcher won’t render unto Caesar his claim of transforming Rome to marble King Alaric: His Famous Sacking of Rome and Secretive Burial .Mosaic representing a ship arriving in the ancient Roman port of Ostia. (Roburq/

CC BY-SA 3.0

)While only two ships could dock in the previous port of Ostia , 200 boats could be accommodated in the new complex of Trajan, since its hexagonal basin of 32 hectares, became the largest center of trade in the ancient world. That space is now a huge artificial lake, which still retains its original six-sided shape.

.Mosaic representing a ship arriving in the ancient Roman port of Ostia. (Roburq/

CC BY-SA 3.0

)While only two ships could dock in the previous port of Ostia , 200 boats could be accommodated in the new complex of Trajan, since its hexagonal basin of 32 hectares, became the largest center of trade in the ancient world. That space is now a huge artificial lake, which still retains its original six-sided shape.

The preparation and reopening of the port is being carried out with funding from public bodies and private patrons, such as the Benetton Foundation and Consortium Airports in Rome . In fact, Fiumicino Airport, located near the site, has even set up a system of free buses to this interesting archaeological feature.

Featured Image: The old imperial port of Rome reveals its archaeological remains. (El Diario/EFE )

By Mariló T.A.

Roman rule meant the control of Rome on ports and marine and land trade routes. In fact, Roman maritime commercial traffic was so important that they improved and expanded existing land routes, creating a vast road network in many regions, which was in service until the 18th century. This allowed them to develop and consolidate areas of commercial influence on some ports - transforming them into centers for very important economic activity.

Now, according to reports in the Spanish publication El Diario , the archaeological remains of the imperial port of Claudius and Trajan has just reopened to the public, and will be accesible for at least six months of this year.

The history of this great port complex started around the year 100 AD, when Rome’s high population of close to a million and a half inhabitants - equivalent to a current concentration of 50 million people, demanded an infrastructure that could ensure sufficient supplies.

The port of Rome built about 2,000 years ago was the most important center of ancient world operations for nearly half a millennium. It was the place for transiting goods from the ends of the earth to supply the entire empire with Greek wines, Andalusian oils, Egyptian cereals, textiles, metals, and wild animals for circuses. In addition, it also served as a defensive base for the ships of the Imperial Navy and as a starting point for their many military campaigns.

Digital recreation of the ancient imperial port of Rome. ( Listín Diario )Once in port, all the goods were deposited in the port warehouses, which today form the best preserved part of the site and attest to the measurement system used and the distribution of the products. Halls and courtyards of its foundations, where ancient deals took place, still remain as well.

Different products were transferred to smaller ships that were responsible for distributing them via the Tiber River through a complex system of canals. These canals managed to save ships from the inconvenience that the Mediterranean was, as a sea which basically was only sailed in summer - just when the flow of the Tiber river declined considerably.

As indicated by the information published by the Listín Diario , an understanding of the functioning and structures of this great site requires an intense exercise in imagination today because where the sea was before, today there is an immense park lined with eucalyptus, pine, and oak trees: the sediment caused the waterfront to gain about four kilometers (2.49 miles) of the sea, and during the first decades of the 20th century the area was reclassified and finally turned into a nature reserve.

Marks can still be seen on the walls where water emerged in some areas near the old docks. The location of the piers is also easy to guess as several flights of stairs and bollards for mooring boats still stand.

Researcher won’t render unto Caesar his claim of transforming Rome to marble King Alaric: His Famous Sacking of Rome and Secretive Burial

.Mosaic representing a ship arriving in the ancient Roman port of Ostia. (Roburq/

CC BY-SA 3.0

)While only two ships could dock in the previous port of Ostia , 200 boats could be accommodated in the new complex of Trajan, since its hexagonal basin of 32 hectares, became the largest center of trade in the ancient world. That space is now a huge artificial lake, which still retains its original six-sided shape.

.Mosaic representing a ship arriving in the ancient Roman port of Ostia. (Roburq/

CC BY-SA 3.0

)While only two ships could dock in the previous port of Ostia , 200 boats could be accommodated in the new complex of Trajan, since its hexagonal basin of 32 hectares, became the largest center of trade in the ancient world. That space is now a huge artificial lake, which still retains its original six-sided shape. The preparation and reopening of the port is being carried out with funding from public bodies and private patrons, such as the Benetton Foundation and Consortium Airports in Rome . In fact, Fiumicino Airport, located near the site, has even set up a system of free buses to this interesting archaeological feature.

Featured Image: The old imperial port of Rome reveals its archaeological remains. (El Diario/EFE )

By Mariló T.A.

Published on May 05, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Rebel barons renounce allegiance to King John

May 5

1215 Rebel barons renounced their allegiance to King John of England, which led to the signing of the Magna Carta

1215 Rebel barons renounced their allegiance to King John of England, which led to the signing of the Magna Carta

Published on May 05, 2016 02:00

May 4, 2016

Inside the mind of Richard III

History Extra

(Illustration by Jonty Clark.)

(Illustration by Jonty Clark.)

Richard liked the finer things in lifeDetails that survive from Richard’s court suggest that the king was no po-faced ascetic but a spendthrift who enjoyed life’s luxuries.

Richard had his own troupe of players and minstrels, while he ordered that one of Edward V’s own servants be retained, for “his expert ability and cunning in the science of music,” ordering that he “take and seize for us and in our name all such singing men and children”.

Richard also seems to have appreciated good fashion sense. In 1484 he sent the Irish Earl of Desmond a parcel including gowns of velvet and cloth of gold “to show unto you… our intent and pleasure for to have you to use the manner of our English habit and clothing”.

The king’s extravagance excited comment from the most unlikely of sources. Thomas Langton – who served as bishop of St David’s, Salisbury and Winchester – praised the king in a letter written shortly after his accession to the throne in the summer of 1483, describing how “he contents the people where he goes best that ever did prince… on my troth I liked never the conditions of any prince so well as his: God hath sent him to us for the weal of us all”. However, in the final line, the bishop added a note of caution: “Sensual pleasure holds sway to an increasing extent, but I do not consider that this detracts from what I have said.”

He was generous (when the mood took him)The Crowland Chronicle – written in Lincolnshire’s Crowland Abbey from the 7th to 15th centuries – describes how Richard intended to “pass over the pomp of Christmas” in 1483. Yet this terse assessment contradicts surviving contemporary records, which tell us that the king spent £764 17s 6d (the equivalent of over £380,000 today) for “certain plate… for our year’s gifts against Christmas last past and for other jewels,” while he gave £100 (£50,000) to “our welbeloved servants the grooms and pages of our chamber… for a reward against the Feast of Christmas”.

At a Whitehall banquet to mark the epiphany celebrations of 6 January 1484, Richard gave the mayor and aldermen of London a gold cup “garnished with pearls and other precious stones” to be used in the chamber of the Guildhall. These were displayed at a council meeting a week later, where it was also declared how Richard “for the very great favour he bears towards this city, intended to bestow and make the borough of Southwark part of the liberty of the City, and also to give £10,000 (£5m) towards the building of walls and ditches around the said borough”.

Intriguingly, this huge financial gift never materialised – and the aldermen of London failed to raise the matter again. Did the evening’s festivities inspire Richard to make this magnanimous gesture – only to conveniently forget about it in the cold light of day?

He regarded himself as a man of YorkThe dispute over where Richard’s remains should be interred has made it all the way to the high court this year. But can contemporary sources shed any light on where the king himself wished to be buried?

Perhaps they can. Though the king is known to have supported several religious institutions – including St George’s Chapel at Windsor, and his own foundations at Middleham in Yorkshire and Queen’s College, Cambridge – he does seem to have placed particular emphasis on his relationship with York, and its famous Minster.

In one document, Richard described the “great zeal and tender affection that we bear in our heart unto our faithful and true subjects the mayor, sheriffs and citizens of the city of York”.

Shortly after his coronation, he travelled northwards to the city, holding a spectacular ceremony in the Minster, to which he donated a “great cross standing on six bases… with images of the crucifixion and the two thieves, together with other images near the foot and many precious stones, rubies and sapphires”.

Richard’s greatest display of affection to the city came on 23 September 1484, when he unveiled plans for a chantry foundation at York Minster, which would house a hundred priests to support the Minster, and practise the “worship of God, our Lady, Saint George and Saint Ninian”. The massive project involved the construction of six altars for the king’s chaplains, together with a separate building to house them.

Several months after his original grant, however, Richard was forced to write a letter to the authorities of the Duchy of Lancaster. Unpublished and unremarked upon by historians who have written on Richard’s plans for a foundation at York, the letter states that in spite of giving to the dean of the Minster and its authorities “our special power and authority to ask, gather and levy all and any sum of money for the time” in order to “sustain and bear the charge of the finding of a hundred priests now being of our foundation,” the priests still remained unpaid for their services.

Richard now demanded that they be paid from the Duchy of Lancaster. “We not willing our said priests to be unpaid of their wages, seeing by their prayers we trust to be made the more acceptable to God and his saints.” The connection between Richard’s establishment of the foundation at York and the salvation of his own soul could hardly be any clearer. Could this indicate that Richard’s real intention in creating this new religious institution was to follow the growing trend for 15th-century aristocrats across Europe to establish their own chantry foundations and ultimately mausoleums? Richard, Duke of York, had done just that at Fotheringay, Northamptonshire, and Edward IV was to follow suit at Windsor.

After Richard’s death, the archbishop there remembered fondly how “our most Christian prince, King Richard III… founded and ordained a most celebrated college of a hundred chaplains, primarily at his own expense”. The foundation was not to last long, however. By 1493, “timber from the house constructed by King Richard III from the establishing of chantry priests” had been broken up and sold.

(Illustration by Jonty Clark.)

He loved his wife (at least, that’s what he claimed)Unlike his brother Edward IV, famed for his debauchery and mistresses, Richard seems to have been a devout family man. He was fond of his only legitimate son, Edward, whom he described as “our dearest first born son Edward, whose outstanding qualities, with which he is singularly endowed for his age, give great and, by the favour of God, undoubted hope of future uprightness”.

Edward’s premature death in April 1484 proved devastating to both Richard and his wife, Anne. The news clearly came unexpectedly, for, according to the Crowland Chronicle, “on hearing news of this, at Nottingham, where they were then residing, you might have seen his father and mother in a state almost bordering on madness, by reason of their sudden grief”.

Several months later, in September 1484, when wrapping up payments for the prince’s disbanded household, Richard continued to describe Edward as “our dearest son the prince”. When Anne herself died on 16 March 1485, rumours swirled that Richard had planned to poison his wife. Yet the records show a very different side to the king who, just days before her death, refers to her as “our most dear wife the queen”.

The king professed in his proclamations his distaste of “horrible adultery and bawds, provoking the high indignation and displeasure of God,” instead preferring “the way of truth and virtue,” and even declared to his bishops that “our principal intent and fervent desire is to see virtue and cleanness of living to be advanced, increased and multiplied, and vices and all other things repugnant to virtue… to be repressed and annulled”.

Yet this did not prevent Richard himself from fathering at least two illegitimate children. One was John of Gloucester, whom Richard evidently thought highly of, appointing him captain of Calais, on account of his “liveliness of mind, activity of body and inclination to all good customs”. The other was Katherine Plantagenet, who Richard married off to William, Earl of Huntingdon, making a generous financial provision to the couple.

He was convinced of his right to ruleUpon the birth of Edward IV’s eldest son, Edward, in 1470, Richard had sworn publicly that the young baby, “first begotten son of our sovereign lord,” was “to be very and undoubted heir to our said lord as to the crowns and realms of England and France and lordship of Ireland… In case hereafter it happen you by God’s disposition to overlive our sovereign lord; I shall then take and accept you for the very true and rightwise king of England.”

Richard was, of course, to break this solemn vow in spectacular style – but how did he justify going back on his word to himself and his peers? The archives provide some clues.

According to a lengthy explanation set down in parliament in 1484, Richard proved that Edward IV had already been contracted to marry Lady Eleanor Talbot before his union with Queen Elizabeth Woodville. As a result, his son Edward V was in fact illegitimate, so unable to take the throne. Two days after he had seized the crown, Richard wrote how men had wrongly sworn an oath to Edward V that had been “ignorantly given”.

In early January 1484, Richard had no qualms in repaying a Cambridgeshire bailiff for wildfowl purchased for Edward V’s aborted coronation, merely describing the planned ceremony as “the time we stood protector of this our realm while Edward bastard son unto our entirely beloved brother Edward IV was called king of this realm”.

In another document in the archives, Richard merely described how he was now the “true and undoubted king of this realm of England by divine and human right,” having “taken the royal dignity and power and the rule and governance of the same realm for himself… from Edward the Bastard, formerly called Edward the fifth… the same Edward legitimately having been removed by usurpation”. It seems that Richard, for one, was absolutely convinced of his right to rule.

He was a formidable warriorThe records reveal that Richard had begun his military training at an early age. In March 1465, his brother Edward IV spent over £20 (£10,000) for “sheaves of arrows” and bows, “to the use of our brethren the dukes of Clarence and Gloucester”.

Richard first saw military action in the battles of Barnet – where one source indicates he was wounded – and Tewkesbury. His fighting skills were praised by one poet, who described Richard as a young Hector. In 1480, Richard wrote to the French king Louis XI, thanking him for “the great bombard which you caused to be presented to me, for I have always taken and still take great pleasure in artillery and I assure you it will be a special treasure to me”.

Richard later took a leading role in the defence of the Scottish borders, and by 1483 the Italian visitor Dominic Mancini was stating that “such was his renown in warfare, that whenever a difficult and dangerous policy had to be undertaken, it would be entrusted to his discretion and generalship”.

The records of Richard’s reign are littered with payments for military weapons and equipment: for instance, he spent £560 (£280,000) on 157 complete suits of armour, and a further £64 19s 1d (£32,000) on 2,228lbs of saltpetre for making gunpowder.

In 1485 Richard ordered that Edward Benstead, a gentleman usher of the chamber, was sent to the Tower to “shoot certain our guns we have been making there for their prove and assay”. Richard also ordered that a “long scaling bridge” under construction at the Tower be put through its paces.

(Illustration by Jonty Clark.)

He threw a good partyDetails of the receipts for Richard III’s coronation banquet survive, and they suggest that the king’s accession to the throne in the summer of 1483 was celebrated in some style. The banquet comprised 75 different dishes over three courses, to be served to 1,200 “messes” (shared tables) that would feed around 3,000 people in total.

The guests tucked into 30 bulls, 140 sheep, 100 calves, six boars, 12 fatted pigs, 200 suckling pigs, eight hart deer, 140 bucks, eight roe deer and fawns. In addition, the lower ranks at the banquet would be treated to 288 marrow bones, 72 ox feet, and 144 calves’ feet.

For the fish dishes, the caterer ordered 400 lampreys, 350 pikes, four porpoises, 40 bream, 30 salmon cut into thin slices, 100 trout, 40 carp, 480 freshwater crayfish, 200 cod and salt fish, another 36 other ‘sea fish’, 100 tench, and 200 mullet.

The banquet also included 1,000 geese, 800 rabbits, 800 chickens, with another 400 chickens ‘to stew’, in addition to 300 sparrows or larks, 2,400 pigeons, 1,000 capons, 800 rails (a large, fat bird), 40 cygnets, 16 dozen heron, 48 peacocks, eight dozen of both cranes and pheasants, six dozen bitterns, 240 quails, three dozen egrets, 12 dozen curlews and 120 ‘piper chicks’ – probably young pigeons.

To spice the dishes, 28lbs of pepper, 8lbs of saffron costing 48 shillings, 28lbs of cinnamon costing 60 shillings, 4lbs of fresh ginger and 12lbs of powdered ginger were employed, though the most popular seasoning seems to have been the sweet variety, with 150lbs of Madeira sugar imported from Portugal, 150lbs of almonds and 200lbs of raisins making up the largest of the orders for spices in the kitchen. Dessert included 300lbs of dates, 100lbs of prunes, 1,000 oranges and 12 gallons of strawberries, decorated with 100 leaves of “pure gold”.

He was hell-bent on crushing his foesThe most detailed description of Richard III and his court comes from an eyewitness account left to us by Niclas von Popplau, a Silesian knight who visited the king while he was staying at Middleham Castle in North Yorkshire in May 1484. Popplau’s text, still only available in its original German, deserves a full English translation, as it gives us our best understanding of Richard by someone who met him face to face. Popplau suggested that Richard was “three fingers taller than I, but a bit slimmer and not as thickset as I am, and much more lightly built. He has quite slender arms and thighs, and also a great heart”.

Popplau was entertained by the king in his royal tent, where he witnessed Richard’s bed, “decorated from top to bottom with red Samite [luxurious silk fabric] and a gold piece” with a table “covered all around with silk cloths of gold embroidered with gold. The king set himself at the table and he wore a collar of an order set with many large pearls, almost like strawberries, and diamonds. The collar was quite as wide as a man’s hand,” Popplau noted.

Richard requested that his German visitor sit next to him at dinner, where the king was so engrossed in conversation that “he hardly touched his food, but talked with me all the time. He asked me about his imperial majesty [Maxmillian I], all kings and princes of the empire whom I knew well, about their habits, fortune, actions and virtues. To which I answered everything that could add to their honour and high standing. Then the king was silent for a while, and then he began again to ask me questions, about many matters and deeds.”

When Popplau began to discuss a recent defeat of the Ottoman Turks in Hungary, Richard suddenly became “very pleased” and answered: “I would like my kingdom and land to lie where the land and kingdom of the king of Hungary lies, on the Turkish frontier itself. Then I would certainly, with my own people alone, without the help of other kings, princes or lords, properly drive away not only the Turks, but all my enemies and opponents.” For Richard, it was a dream that proved impossible to fulfil.

Chris Skidmore MP is an author and historian who also serves as Conservative MP for Kingswood.

(Illustration by Jonty Clark.)

(Illustration by Jonty Clark.) Richard liked the finer things in lifeDetails that survive from Richard’s court suggest that the king was no po-faced ascetic but a spendthrift who enjoyed life’s luxuries.

Richard had his own troupe of players and minstrels, while he ordered that one of Edward V’s own servants be retained, for “his expert ability and cunning in the science of music,” ordering that he “take and seize for us and in our name all such singing men and children”.

Richard also seems to have appreciated good fashion sense. In 1484 he sent the Irish Earl of Desmond a parcel including gowns of velvet and cloth of gold “to show unto you… our intent and pleasure for to have you to use the manner of our English habit and clothing”.

The king’s extravagance excited comment from the most unlikely of sources. Thomas Langton – who served as bishop of St David’s, Salisbury and Winchester – praised the king in a letter written shortly after his accession to the throne in the summer of 1483, describing how “he contents the people where he goes best that ever did prince… on my troth I liked never the conditions of any prince so well as his: God hath sent him to us for the weal of us all”. However, in the final line, the bishop added a note of caution: “Sensual pleasure holds sway to an increasing extent, but I do not consider that this detracts from what I have said.”

He was generous (when the mood took him)The Crowland Chronicle – written in Lincolnshire’s Crowland Abbey from the 7th to 15th centuries – describes how Richard intended to “pass over the pomp of Christmas” in 1483. Yet this terse assessment contradicts surviving contemporary records, which tell us that the king spent £764 17s 6d (the equivalent of over £380,000 today) for “certain plate… for our year’s gifts against Christmas last past and for other jewels,” while he gave £100 (£50,000) to “our welbeloved servants the grooms and pages of our chamber… for a reward against the Feast of Christmas”.

At a Whitehall banquet to mark the epiphany celebrations of 6 January 1484, Richard gave the mayor and aldermen of London a gold cup “garnished with pearls and other precious stones” to be used in the chamber of the Guildhall. These were displayed at a council meeting a week later, where it was also declared how Richard “for the very great favour he bears towards this city, intended to bestow and make the borough of Southwark part of the liberty of the City, and also to give £10,000 (£5m) towards the building of walls and ditches around the said borough”.

Intriguingly, this huge financial gift never materialised – and the aldermen of London failed to raise the matter again. Did the evening’s festivities inspire Richard to make this magnanimous gesture – only to conveniently forget about it in the cold light of day?

He regarded himself as a man of YorkThe dispute over where Richard’s remains should be interred has made it all the way to the high court this year. But can contemporary sources shed any light on where the king himself wished to be buried?

Perhaps they can. Though the king is known to have supported several religious institutions – including St George’s Chapel at Windsor, and his own foundations at Middleham in Yorkshire and Queen’s College, Cambridge – he does seem to have placed particular emphasis on his relationship with York, and its famous Minster.

In one document, Richard described the “great zeal and tender affection that we bear in our heart unto our faithful and true subjects the mayor, sheriffs and citizens of the city of York”.

Shortly after his coronation, he travelled northwards to the city, holding a spectacular ceremony in the Minster, to which he donated a “great cross standing on six bases… with images of the crucifixion and the two thieves, together with other images near the foot and many precious stones, rubies and sapphires”.

Richard’s greatest display of affection to the city came on 23 September 1484, when he unveiled plans for a chantry foundation at York Minster, which would house a hundred priests to support the Minster, and practise the “worship of God, our Lady, Saint George and Saint Ninian”. The massive project involved the construction of six altars for the king’s chaplains, together with a separate building to house them.

Several months after his original grant, however, Richard was forced to write a letter to the authorities of the Duchy of Lancaster. Unpublished and unremarked upon by historians who have written on Richard’s plans for a foundation at York, the letter states that in spite of giving to the dean of the Minster and its authorities “our special power and authority to ask, gather and levy all and any sum of money for the time” in order to “sustain and bear the charge of the finding of a hundred priests now being of our foundation,” the priests still remained unpaid for their services.

Richard now demanded that they be paid from the Duchy of Lancaster. “We not willing our said priests to be unpaid of their wages, seeing by their prayers we trust to be made the more acceptable to God and his saints.” The connection between Richard’s establishment of the foundation at York and the salvation of his own soul could hardly be any clearer. Could this indicate that Richard’s real intention in creating this new religious institution was to follow the growing trend for 15th-century aristocrats across Europe to establish their own chantry foundations and ultimately mausoleums? Richard, Duke of York, had done just that at Fotheringay, Northamptonshire, and Edward IV was to follow suit at Windsor.

After Richard’s death, the archbishop there remembered fondly how “our most Christian prince, King Richard III… founded and ordained a most celebrated college of a hundred chaplains, primarily at his own expense”. The foundation was not to last long, however. By 1493, “timber from the house constructed by King Richard III from the establishing of chantry priests” had been broken up and sold.

(Illustration by Jonty Clark.)

He loved his wife (at least, that’s what he claimed)Unlike his brother Edward IV, famed for his debauchery and mistresses, Richard seems to have been a devout family man. He was fond of his only legitimate son, Edward, whom he described as “our dearest first born son Edward, whose outstanding qualities, with which he is singularly endowed for his age, give great and, by the favour of God, undoubted hope of future uprightness”.

Edward’s premature death in April 1484 proved devastating to both Richard and his wife, Anne. The news clearly came unexpectedly, for, according to the Crowland Chronicle, “on hearing news of this, at Nottingham, where they were then residing, you might have seen his father and mother in a state almost bordering on madness, by reason of their sudden grief”.

Several months later, in September 1484, when wrapping up payments for the prince’s disbanded household, Richard continued to describe Edward as “our dearest son the prince”. When Anne herself died on 16 March 1485, rumours swirled that Richard had planned to poison his wife. Yet the records show a very different side to the king who, just days before her death, refers to her as “our most dear wife the queen”.

The king professed in his proclamations his distaste of “horrible adultery and bawds, provoking the high indignation and displeasure of God,” instead preferring “the way of truth and virtue,” and even declared to his bishops that “our principal intent and fervent desire is to see virtue and cleanness of living to be advanced, increased and multiplied, and vices and all other things repugnant to virtue… to be repressed and annulled”.

Yet this did not prevent Richard himself from fathering at least two illegitimate children. One was John of Gloucester, whom Richard evidently thought highly of, appointing him captain of Calais, on account of his “liveliness of mind, activity of body and inclination to all good customs”. The other was Katherine Plantagenet, who Richard married off to William, Earl of Huntingdon, making a generous financial provision to the couple.

He was convinced of his right to ruleUpon the birth of Edward IV’s eldest son, Edward, in 1470, Richard had sworn publicly that the young baby, “first begotten son of our sovereign lord,” was “to be very and undoubted heir to our said lord as to the crowns and realms of England and France and lordship of Ireland… In case hereafter it happen you by God’s disposition to overlive our sovereign lord; I shall then take and accept you for the very true and rightwise king of England.”

Richard was, of course, to break this solemn vow in spectacular style – but how did he justify going back on his word to himself and his peers? The archives provide some clues.

According to a lengthy explanation set down in parliament in 1484, Richard proved that Edward IV had already been contracted to marry Lady Eleanor Talbot before his union with Queen Elizabeth Woodville. As a result, his son Edward V was in fact illegitimate, so unable to take the throne. Two days after he had seized the crown, Richard wrote how men had wrongly sworn an oath to Edward V that had been “ignorantly given”.

In early January 1484, Richard had no qualms in repaying a Cambridgeshire bailiff for wildfowl purchased for Edward V’s aborted coronation, merely describing the planned ceremony as “the time we stood protector of this our realm while Edward bastard son unto our entirely beloved brother Edward IV was called king of this realm”.

In another document in the archives, Richard merely described how he was now the “true and undoubted king of this realm of England by divine and human right,” having “taken the royal dignity and power and the rule and governance of the same realm for himself… from Edward the Bastard, formerly called Edward the fifth… the same Edward legitimately having been removed by usurpation”. It seems that Richard, for one, was absolutely convinced of his right to rule.

He was a formidable warriorThe records reveal that Richard had begun his military training at an early age. In March 1465, his brother Edward IV spent over £20 (£10,000) for “sheaves of arrows” and bows, “to the use of our brethren the dukes of Clarence and Gloucester”.

Richard first saw military action in the battles of Barnet – where one source indicates he was wounded – and Tewkesbury. His fighting skills were praised by one poet, who described Richard as a young Hector. In 1480, Richard wrote to the French king Louis XI, thanking him for “the great bombard which you caused to be presented to me, for I have always taken and still take great pleasure in artillery and I assure you it will be a special treasure to me”.

Richard later took a leading role in the defence of the Scottish borders, and by 1483 the Italian visitor Dominic Mancini was stating that “such was his renown in warfare, that whenever a difficult and dangerous policy had to be undertaken, it would be entrusted to his discretion and generalship”.

The records of Richard’s reign are littered with payments for military weapons and equipment: for instance, he spent £560 (£280,000) on 157 complete suits of armour, and a further £64 19s 1d (£32,000) on 2,228lbs of saltpetre for making gunpowder.

In 1485 Richard ordered that Edward Benstead, a gentleman usher of the chamber, was sent to the Tower to “shoot certain our guns we have been making there for their prove and assay”. Richard also ordered that a “long scaling bridge” under construction at the Tower be put through its paces.

(Illustration by Jonty Clark.)

He threw a good partyDetails of the receipts for Richard III’s coronation banquet survive, and they suggest that the king’s accession to the throne in the summer of 1483 was celebrated in some style. The banquet comprised 75 different dishes over three courses, to be served to 1,200 “messes” (shared tables) that would feed around 3,000 people in total.

The guests tucked into 30 bulls, 140 sheep, 100 calves, six boars, 12 fatted pigs, 200 suckling pigs, eight hart deer, 140 bucks, eight roe deer and fawns. In addition, the lower ranks at the banquet would be treated to 288 marrow bones, 72 ox feet, and 144 calves’ feet.

For the fish dishes, the caterer ordered 400 lampreys, 350 pikes, four porpoises, 40 bream, 30 salmon cut into thin slices, 100 trout, 40 carp, 480 freshwater crayfish, 200 cod and salt fish, another 36 other ‘sea fish’, 100 tench, and 200 mullet.

The banquet also included 1,000 geese, 800 rabbits, 800 chickens, with another 400 chickens ‘to stew’, in addition to 300 sparrows or larks, 2,400 pigeons, 1,000 capons, 800 rails (a large, fat bird), 40 cygnets, 16 dozen heron, 48 peacocks, eight dozen of both cranes and pheasants, six dozen bitterns, 240 quails, three dozen egrets, 12 dozen curlews and 120 ‘piper chicks’ – probably young pigeons.

To spice the dishes, 28lbs of pepper, 8lbs of saffron costing 48 shillings, 28lbs of cinnamon costing 60 shillings, 4lbs of fresh ginger and 12lbs of powdered ginger were employed, though the most popular seasoning seems to have been the sweet variety, with 150lbs of Madeira sugar imported from Portugal, 150lbs of almonds and 200lbs of raisins making up the largest of the orders for spices in the kitchen. Dessert included 300lbs of dates, 100lbs of prunes, 1,000 oranges and 12 gallons of strawberries, decorated with 100 leaves of “pure gold”.

He was hell-bent on crushing his foesThe most detailed description of Richard III and his court comes from an eyewitness account left to us by Niclas von Popplau, a Silesian knight who visited the king while he was staying at Middleham Castle in North Yorkshire in May 1484. Popplau’s text, still only available in its original German, deserves a full English translation, as it gives us our best understanding of Richard by someone who met him face to face. Popplau suggested that Richard was “three fingers taller than I, but a bit slimmer and not as thickset as I am, and much more lightly built. He has quite slender arms and thighs, and also a great heart”.

Popplau was entertained by the king in his royal tent, where he witnessed Richard’s bed, “decorated from top to bottom with red Samite [luxurious silk fabric] and a gold piece” with a table “covered all around with silk cloths of gold embroidered with gold. The king set himself at the table and he wore a collar of an order set with many large pearls, almost like strawberries, and diamonds. The collar was quite as wide as a man’s hand,” Popplau noted.

Richard requested that his German visitor sit next to him at dinner, where the king was so engrossed in conversation that “he hardly touched his food, but talked with me all the time. He asked me about his imperial majesty [Maxmillian I], all kings and princes of the empire whom I knew well, about their habits, fortune, actions and virtues. To which I answered everything that could add to their honour and high standing. Then the king was silent for a while, and then he began again to ask me questions, about many matters and deeds.”

When Popplau began to discuss a recent defeat of the Ottoman Turks in Hungary, Richard suddenly became “very pleased” and answered: “I would like my kingdom and land to lie where the land and kingdom of the king of Hungary lies, on the Turkish frontier itself. Then I would certainly, with my own people alone, without the help of other kings, princes or lords, properly drive away not only the Turks, but all my enemies and opponents.” For Richard, it was a dream that proved impossible to fulfil.

Chris Skidmore MP is an author and historian who also serves as Conservative MP for Kingswood.

Published on May 04, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - battle of Tewkesbury

Published on May 04, 2016 02:00

May 3, 2016

600 Kilos of 4th Century Roman Bronze Coins Discovered in Spain

Ancient Origins

Works being carried out in the town of Tomares in Spain have brought to light 19 Roman amphorae containing 600 kilos (1322.77 lbs.) of bronze coins from the 4th century: a finding that archaeologists consider rare in Spain and perhaps worldwide as well.

According to information published by the Spanish newspaper 20 Minutos, the amphorae – 10 complete and nine broken - do not correspond to those used at the time for wine or grain transport, but are smaller and were found in a sealed receptacle covered with broken materials. The formidable set was found during construction work in Olivar del Zaudín Park in Tomares.

The researchers’ initial hypothesis about such an accumulation of coins in one receptacle is that the money could have been destined to pay imperial taxes or the army. Sources from the Ministry of Culture explained to 20 Minutos that the coins “were deliberately hidden in an underground space and covered by some bricks and ceramic material.”

Some of the amphorae as they were discovered. (

20 Minutos

)The coins, which are now in the Archaeological Museum of Seville awaiting the necessary reports to determine their value, show the figure of an emperor on the front and various Roman symbols on the back, such as one referring to abundance. They were probably minted in the East and all have been called Fleur de Coin (essentially a perfect coin): they have not circulated and therefore do not present any wear.

Some of the amphorae as they were discovered. (

20 Minutos

)The coins, which are now in the Archaeological Museum of Seville awaiting the necessary reports to determine their value, show the figure of an emperor on the front and various Roman symbols on the back, such as one referring to abundance. They were probably minted in the East and all have been called Fleur de Coin (essentially a perfect coin): they have not circulated and therefore do not present any wear.

Farmer discovers huge hoard of more than 4,000 ancient Roman coins in SwitzerlandHidden hoard of more than 6,000 silver coins found in forest in PolandHoard of 22,000 Roman coins is among largest collections found in BritainAs reported by the Spanish newspaper El País, the councilwoman, Lola Vallejo, said that the discovery of the amphorae is "timely", so that the canalization in Olivar del Zaudín Park "will continue normally".

Nine of the 10 complete amphorae. (

20 Minutos/Ayuntamiento de Tomares/ EFE

)Lola Vallejo explained to El Pais that when work began in one of the trenches they had just gone one meter (3.28 ft.) deep when the machine detected something that was not normal, so "they stopped the work" and that was when the workers discovered the amphorae.

Nine of the 10 complete amphorae. (

20 Minutos/Ayuntamiento de Tomares/ EFE

)Lola Vallejo explained to El Pais that when work began in one of the trenches they had just gone one meter (3.28 ft.) deep when the machine detected something that was not normal, so "they stopped the work" and that was when the workers discovered the amphorae.

From there, she went on to say that "the proper protocol was activated as it is established in these cases" and the Civil Guard and archaeologists "went to determine the correct procedure." Then "archaeologists indicated that they should open a wider trench" and by "late afternoon the process was completed and they told us it was a timely discovery, so today works could continue as normal."

Some of the amphorae and coins that were unearthed in Tomares, Spain. (

Paco Puentes/El País

)Featured Image: An amphora filled with coins that was unearthed in Tomares, Spain. Source:

Paco Puentes/El País

Some of the amphorae and coins that were unearthed in Tomares, Spain. (

Paco Puentes/El País

)Featured Image: An amphora filled with coins that was unearthed in Tomares, Spain. Source:

Paco Puentes/El País

By Mariló T. A.

Works being carried out in the town of Tomares in Spain have brought to light 19 Roman amphorae containing 600 kilos (1322.77 lbs.) of bronze coins from the 4th century: a finding that archaeologists consider rare in Spain and perhaps worldwide as well.

According to information published by the Spanish newspaper 20 Minutos, the amphorae – 10 complete and nine broken - do not correspond to those used at the time for wine or grain transport, but are smaller and were found in a sealed receptacle covered with broken materials. The formidable set was found during construction work in Olivar del Zaudín Park in Tomares.

The researchers’ initial hypothesis about such an accumulation of coins in one receptacle is that the money could have been destined to pay imperial taxes or the army. Sources from the Ministry of Culture explained to 20 Minutos that the coins “were deliberately hidden in an underground space and covered by some bricks and ceramic material.”

Some of the amphorae as they were discovered. (

20 Minutos

)The coins, which are now in the Archaeological Museum of Seville awaiting the necessary reports to determine their value, show the figure of an emperor on the front and various Roman symbols on the back, such as one referring to abundance. They were probably minted in the East and all have been called Fleur de Coin (essentially a perfect coin): they have not circulated and therefore do not present any wear.

Some of the amphorae as they were discovered. (

20 Minutos

)The coins, which are now in the Archaeological Museum of Seville awaiting the necessary reports to determine their value, show the figure of an emperor on the front and various Roman symbols on the back, such as one referring to abundance. They were probably minted in the East and all have been called Fleur de Coin (essentially a perfect coin): they have not circulated and therefore do not present any wear.Farmer discovers huge hoard of more than 4,000 ancient Roman coins in SwitzerlandHidden hoard of more than 6,000 silver coins found in forest in PolandHoard of 22,000 Roman coins is among largest collections found in BritainAs reported by the Spanish newspaper El País, the councilwoman, Lola Vallejo, said that the discovery of the amphorae is "timely", so that the canalization in Olivar del Zaudín Park "will continue normally".

Nine of the 10 complete amphorae. (

20 Minutos/Ayuntamiento de Tomares/ EFE

)Lola Vallejo explained to El Pais that when work began in one of the trenches they had just gone one meter (3.28 ft.) deep when the machine detected something that was not normal, so "they stopped the work" and that was when the workers discovered the amphorae.

Nine of the 10 complete amphorae. (

20 Minutos/Ayuntamiento de Tomares/ EFE

)Lola Vallejo explained to El Pais that when work began in one of the trenches they had just gone one meter (3.28 ft.) deep when the machine detected something that was not normal, so "they stopped the work" and that was when the workers discovered the amphorae.From there, she went on to say that "the proper protocol was activated as it is established in these cases" and the Civil Guard and archaeologists "went to determine the correct procedure." Then "archaeologists indicated that they should open a wider trench" and by "late afternoon the process was completed and they told us it was a timely discovery, so today works could continue as normal."

Some of the amphorae and coins that were unearthed in Tomares, Spain. (

Paco Puentes/El País

)Featured Image: An amphora filled with coins that was unearthed in Tomares, Spain. Source:

Paco Puentes/El País

Some of the amphorae and coins that were unearthed in Tomares, Spain. (

Paco Puentes/El País

)Featured Image: An amphora filled with coins that was unearthed in Tomares, Spain. Source:

Paco Puentes/El País

By Mariló T. A.

Published on May 03, 2016 03:00