MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 107

April 13, 2016

A guide to ancient gardening

History Extra

Roman garden at the House of the Golden Cupids, Pompeii. (Linda Farrar)

Roman garden at the House of the Golden Cupids, Pompeii. (Linda Farrar)

The art of gardening and horticulture can be said to have its beginning with the first farmers, when they started to cultivate vegetables as opposed to field crops. Vegetable plots tended to be located close to the home, as these plants needed more watering and special care. More often than not the plot would have had an enclosing barrier to prevent livestock from eating the plants growing inside it. While there may initially have been a need for self-sufficiency, over time gardens have also been a way for people to enhance their surroundings. The art of gardening can be found in the ancient literature, art and archaeology of most early societies, from Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome and Byzantium to the early Islamic and medieval worlds. There are even hints of the existence of Minoan and Etruscan gardens. Actual evidence for horticulture and gardening, as opposed to agriculture, can be dated back to the third or fourth millennium BC at least, to the early civilisations of Mesopotamia and Egypt. In countries with hot summer climates, measures were necessary to ensure that the fierce sun would not scorch plants. One solution – as mentioned in an early Mesopotamian myth – was for the gardener to plant a wide branching tree to create vital shade, allowing more delicate plants to grow below its ample canopy. Trees became an integral part of a garden. In ancient Egypt, trees were planted to make sacred groves around royal tombs. One of the earliest was created in the Old Kingdom, fourth dynasty, for Pharaoh Sneferu at Dahshur (c2613–2589 BC). Trees were also used in urban gardens to provide shade, and there was a conscious preference to included fruit- or nut-bearing trees. The most favoured trees in Egypt were three species of palm tree (the date palm, doum palm & argun – phoenix dactylifera, hyphaene thebaic and medemia argun respectively), the sycomore fig (ficus sycomorus) and the beautiful persea (mimusops laurifolia). One tomb owner called Ineni, architect and royal gardener of pharaoh Tuthmosis I (c1504–1492 BC), mentions having 540 trees, from over 15 species, in what must have been a large garden or orchard. Meanwhile, the tomb of high-ranking Egyptian official Meketre (c2055–2004 BC) contained a remarkable wooden model of a smaller domestic walled garden, featuring a large rectangular pool surrounded by seven large fruiting trees. A range of trees and plants, such as pomegranates, were introduced into Egypt over the years. Pharaoh Tuthmosis III even had images of notable plants that he had brought back from a military campaign carved onto the walls of a room in the temple at Karnak. This room is now usually called the Botanical Garden.

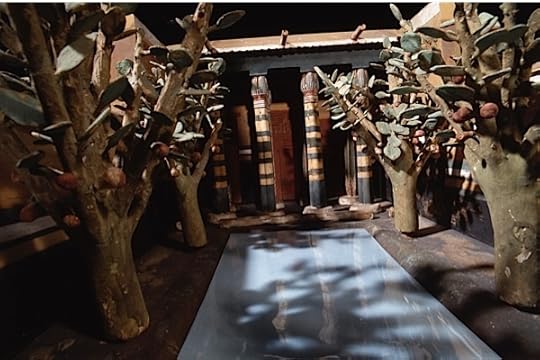

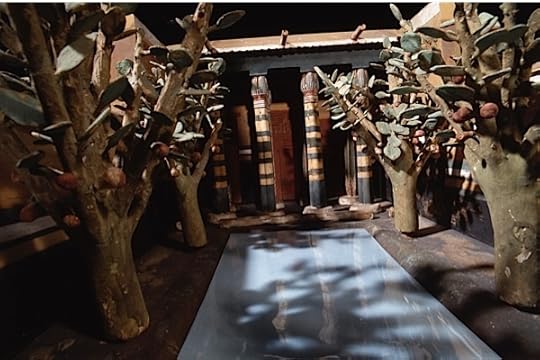

Model of a walled garden with central pool and columned portico, from the tomb of ancient Egyptian nobleman Meketre. (Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images) Some Assyrian kings in Mesopotamia extracted a tribute of fruit trees from the cities they conquered in more northerly regions and were known to have created large gardens, orchards and game parks. Images of both Sargon II and Sennacherib's gardens were carved on reliefs in palaces (at Khorsabad and Nineveh respectively). Despite being stylised, they give an indication of the possible layout and features that the gardens may have contained, such as pathways, pavilions and altars. In each ancient culture we find a variety of deities responsible for fertility and agriculture, including specific ones intended to protect plants and crops. Gardens also featured frequently in ancient mythology. Many myths were woven to explain the features of a particular plant, such as the Greek tales of Daphne or Nárkissos (narcissus). There were also tales of rivalry between competitive plants to determine which was the most useful or beautiful. The Mesopotamian tale of the tamarisk and the date-palm is perhaps the earliest of these, but the theme is also found in myths about the one-upmanship of the olive and bay tree in later cultures. Legends about beautiful gardens were popular, from the fabled Homeric Garden of Alkinoös and the Garden of the Hesperides with its famous golden apples, to the Biblical Garden of Eden, or the Islamic Garden of Eram. Favoured gardens could be seen as a paradise on earth and on occasion, garden owners in several ancient societies compared their own gardens with mythical ones. In some places, traces of a garden’s design are discernable. In the Roman period, plant beds and pools were not always rectangular: straight lines were often alleviated by semi-circular or rectangular recesses. Topiary (invented by the Romans) was carefully clipped and hedges were given architectural recesses to soften the lines of a pathway, as at Fishbourne Palace in southern England. Design is especially noticeable at Pompeii and Herculaneum, where volcanic ash and tufaceous mud from the eruption of mount Vesuvius in AD 79 covered and preserved gardens. Evidence of both large and small gardens has been discovered in these Roman towns. Some were surrounded by a peristyle of columns (such as in the House of the Golden Cupids), while in others only a narrow strip was available to be planted. For the latter, the house owner was often found to have painted the wall behind the plants with a suitable verdant scene. This would have given a wonderful trompe l'oeil effect, enlarging the appearance of the garden.

Peristyle of columns round a garden in the House of the Golden Cupids. (DeAgostini/Getty Images) The gardeners who toiled in gardens are often depicted on Egyptian tomb walls, and in mosaics and illuminated manuscripts of later periods. Ancient texts reveal the nature of the work they carried out. Fortunately, because agrihorticultural manuals were considered so important, several have survived. Each society had a name for a gardener, sometimes differentiated by the specific tasks they performed, such as water carrier, vegetable gardener, ornamental gardener (landscape gardener) or head gardener. The hard work of gardeners was often highly thought of and in some cases individual gardener's names have survived. There are even instances of several generations of gardeners. Garden plants are mentioned in the contemporary literature of each period, and in surviving herbal and agricultural manuals. Literary plant descriptions can be compared with botanical discoveries made through archaeology, and this data has been collated to provide a plant list for the major cultures of the past. It is interesting to see how many ancient plant names have survived, in an adapted form, into our modern Linnaean Latin botanical naming system. In ancient Egypt, flowers were cultivated in order to make bouquets, not just for gardens’ owners but also to honour the gods. Tomb paintings show offerings of foodstuffs and garden produce including vegetables and fruit, on top of which bouquets of flowers were placed. Flowers were also grown to make garlands and floral crowns, and there were even court florists. Archaeologists found that Tutankhamun's innermost coffin had been decorated with a floral collar made from numerous flower petals sewn together. Garlands, wreathes and floral crowns were also made by people of later cultures. The Achaemenid Persians employed numerous garland makers, and the Minoans, Etruscans, Greeks and Romans also enjoyed wearing these ephemeral items. In one section of his ancient work Deipnosophistae, Athenaeus of Naucratis names the various plants used to make specific types of garland, revealing those in favour at the time. In most societies, the rose was the most admired flower of all, followed by the lily, sweet violet and narcissus. However, the climate of different regions would have had a bearing on the plants that they were able to cultivate, leading to differences in the range of plant species available. Over the centuries plants were introduced and propagated by ancient societies, first by the Egyptians, Assyrians and Achaemenid Persians, then later by the Romans, who disseminated a wide variety of plants throughout their provinces. Early Islamic gardeners and botanists in southern Spain continued this process, in turn introducing more plants to medieval Europe. Each period had its own characteristics, but it is clear that, across ancient cultures, gardens were seen as amenities that could also give pleasure to the people who used them. Although they required work and maintenance, they were still viewed as areas for relaxation and contemplation. As in the present day, the gardens of the past fulfilled a need to nurture and to enhance people’s surroundings. Linda Farrar is author of Gardens and Gardeners of the Ancient World (Windgather, January 2016).

Roman garden at the House of the Golden Cupids, Pompeii. (Linda Farrar)

Roman garden at the House of the Golden Cupids, Pompeii. (Linda Farrar) The art of gardening and horticulture can be said to have its beginning with the first farmers, when they started to cultivate vegetables as opposed to field crops. Vegetable plots tended to be located close to the home, as these plants needed more watering and special care. More often than not the plot would have had an enclosing barrier to prevent livestock from eating the plants growing inside it. While there may initially have been a need for self-sufficiency, over time gardens have also been a way for people to enhance their surroundings. The art of gardening can be found in the ancient literature, art and archaeology of most early societies, from Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome and Byzantium to the early Islamic and medieval worlds. There are even hints of the existence of Minoan and Etruscan gardens. Actual evidence for horticulture and gardening, as opposed to agriculture, can be dated back to the third or fourth millennium BC at least, to the early civilisations of Mesopotamia and Egypt. In countries with hot summer climates, measures were necessary to ensure that the fierce sun would not scorch plants. One solution – as mentioned in an early Mesopotamian myth – was for the gardener to plant a wide branching tree to create vital shade, allowing more delicate plants to grow below its ample canopy. Trees became an integral part of a garden. In ancient Egypt, trees were planted to make sacred groves around royal tombs. One of the earliest was created in the Old Kingdom, fourth dynasty, for Pharaoh Sneferu at Dahshur (c2613–2589 BC). Trees were also used in urban gardens to provide shade, and there was a conscious preference to included fruit- or nut-bearing trees. The most favoured trees in Egypt were three species of palm tree (the date palm, doum palm & argun – phoenix dactylifera, hyphaene thebaic and medemia argun respectively), the sycomore fig (ficus sycomorus) and the beautiful persea (mimusops laurifolia). One tomb owner called Ineni, architect and royal gardener of pharaoh Tuthmosis I (c1504–1492 BC), mentions having 540 trees, from over 15 species, in what must have been a large garden or orchard. Meanwhile, the tomb of high-ranking Egyptian official Meketre (c2055–2004 BC) contained a remarkable wooden model of a smaller domestic walled garden, featuring a large rectangular pool surrounded by seven large fruiting trees. A range of trees and plants, such as pomegranates, were introduced into Egypt over the years. Pharaoh Tuthmosis III even had images of notable plants that he had brought back from a military campaign carved onto the walls of a room in the temple at Karnak. This room is now usually called the Botanical Garden.

Model of a walled garden with central pool and columned portico, from the tomb of ancient Egyptian nobleman Meketre. (Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images) Some Assyrian kings in Mesopotamia extracted a tribute of fruit trees from the cities they conquered in more northerly regions and were known to have created large gardens, orchards and game parks. Images of both Sargon II and Sennacherib's gardens were carved on reliefs in palaces (at Khorsabad and Nineveh respectively). Despite being stylised, they give an indication of the possible layout and features that the gardens may have contained, such as pathways, pavilions and altars. In each ancient culture we find a variety of deities responsible for fertility and agriculture, including specific ones intended to protect plants and crops. Gardens also featured frequently in ancient mythology. Many myths were woven to explain the features of a particular plant, such as the Greek tales of Daphne or Nárkissos (narcissus). There were also tales of rivalry between competitive plants to determine which was the most useful or beautiful. The Mesopotamian tale of the tamarisk and the date-palm is perhaps the earliest of these, but the theme is also found in myths about the one-upmanship of the olive and bay tree in later cultures. Legends about beautiful gardens were popular, from the fabled Homeric Garden of Alkinoös and the Garden of the Hesperides with its famous golden apples, to the Biblical Garden of Eden, or the Islamic Garden of Eram. Favoured gardens could be seen as a paradise on earth and on occasion, garden owners in several ancient societies compared their own gardens with mythical ones. In some places, traces of a garden’s design are discernable. In the Roman period, plant beds and pools were not always rectangular: straight lines were often alleviated by semi-circular or rectangular recesses. Topiary (invented by the Romans) was carefully clipped and hedges were given architectural recesses to soften the lines of a pathway, as at Fishbourne Palace in southern England. Design is especially noticeable at Pompeii and Herculaneum, where volcanic ash and tufaceous mud from the eruption of mount Vesuvius in AD 79 covered and preserved gardens. Evidence of both large and small gardens has been discovered in these Roman towns. Some were surrounded by a peristyle of columns (such as in the House of the Golden Cupids), while in others only a narrow strip was available to be planted. For the latter, the house owner was often found to have painted the wall behind the plants with a suitable verdant scene. This would have given a wonderful trompe l'oeil effect, enlarging the appearance of the garden.

Peristyle of columns round a garden in the House of the Golden Cupids. (DeAgostini/Getty Images) The gardeners who toiled in gardens are often depicted on Egyptian tomb walls, and in mosaics and illuminated manuscripts of later periods. Ancient texts reveal the nature of the work they carried out. Fortunately, because agrihorticultural manuals were considered so important, several have survived. Each society had a name for a gardener, sometimes differentiated by the specific tasks they performed, such as water carrier, vegetable gardener, ornamental gardener (landscape gardener) or head gardener. The hard work of gardeners was often highly thought of and in some cases individual gardener's names have survived. There are even instances of several generations of gardeners. Garden plants are mentioned in the contemporary literature of each period, and in surviving herbal and agricultural manuals. Literary plant descriptions can be compared with botanical discoveries made through archaeology, and this data has been collated to provide a plant list for the major cultures of the past. It is interesting to see how many ancient plant names have survived, in an adapted form, into our modern Linnaean Latin botanical naming system. In ancient Egypt, flowers were cultivated in order to make bouquets, not just for gardens’ owners but also to honour the gods. Tomb paintings show offerings of foodstuffs and garden produce including vegetables and fruit, on top of which bouquets of flowers were placed. Flowers were also grown to make garlands and floral crowns, and there were even court florists. Archaeologists found that Tutankhamun's innermost coffin had been decorated with a floral collar made from numerous flower petals sewn together. Garlands, wreathes and floral crowns were also made by people of later cultures. The Achaemenid Persians employed numerous garland makers, and the Minoans, Etruscans, Greeks and Romans also enjoyed wearing these ephemeral items. In one section of his ancient work Deipnosophistae, Athenaeus of Naucratis names the various plants used to make specific types of garland, revealing those in favour at the time. In most societies, the rose was the most admired flower of all, followed by the lily, sweet violet and narcissus. However, the climate of different regions would have had a bearing on the plants that they were able to cultivate, leading to differences in the range of plant species available. Over the centuries plants were introduced and propagated by ancient societies, first by the Egyptians, Assyrians and Achaemenid Persians, then later by the Romans, who disseminated a wide variety of plants throughout their provinces. Early Islamic gardeners and botanists in southern Spain continued this process, in turn introducing more plants to medieval Europe. Each period had its own characteristics, but it is clear that, across ancient cultures, gardens were seen as amenities that could also give pleasure to the people who used them. Although they required work and maintenance, they were still viewed as areas for relaxation and contemplation. As in the present day, the gardens of the past fulfilled a need to nurture and to enhance people’s surroundings. Linda Farrar is author of Gardens and Gardeners of the Ancient World (Windgather, January 2016).

Published on April 13, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Edict of Nantes issued

April 13

1598 Henry IV of France issued the Edict of Nantes, allowing freedom of religion to the Huguenots.

(Edict repealed in 1685.)

1598 Henry IV of France issued the Edict of Nantes, allowing freedom of religion to the Huguenots.

(Edict repealed in 1685.)

Published on April 13, 2016 01:30

April 12, 2016

7 Victorian recipes

History Extra

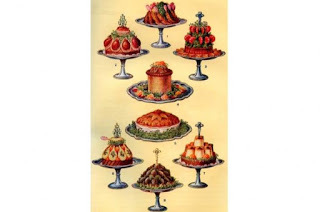

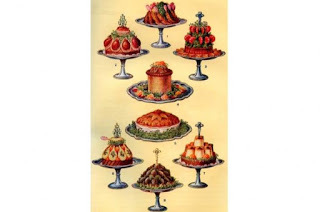

Illustrations of decorative pies from Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management, 1861. (Credit: Culture Club/Getty Images)

Illustrations of decorative pies from Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management, 1861. (Credit: Culture Club/Getty Images)

1) Brown bread ice creamMade from a mixture of vanilla ice cream and caramelised wholemeal breadcrumbs, brown bread ice cream was a popular treat among the upper-class in the late 19th century.

To read the Cook it! recipe in full, click here.

2) Classic Victoria sandwichPossibly the most popular teatime treat in Britain, the Victoria sandwich is made of two simple sponges, with lashings of strawberry jam and cream layered in-between.

To read the BBC Good Food recipe in full, click here.

3) KedgereeBritish colonials based in India first created kedgeree during the 19th century. After they passed on their recipe to their friends back home, kedgeree became the staple of many breakfast tables across Britain. The dish is made of rice, smoked haddock and plenty of spice.

To read the Cook it! recipe in full, click here.

4) SyllabubSyllabub is a boozy yet creamy dessert, popular among the elite during the 17th and 18th centuries. Usually made with fortified wines such as sherry, this sweet treat also featured at high society banquets during the Victorian period.

To read Mrs Beeton's recipe on the BBC, click here.

5) Spotted dickMade from suet pastry, dried currants and raisins, spotted dick first appeared in The Modern Housewife cookbook by French chef Alexis Soyer in 1849. Serve this pudding with lashings of hot custard.

To read the BBC Good Food recipe in full, click here.

6) TeacakesThe perfect accompaniment to a strong cup of tea, teacakes are sweet buns filled with dried fruit. Usually toasted and smothered in butter, a recipe for teacakes is mentioned in Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management – the bestselling guide to running a home in the 19th century.

To read Mrs Beeton's recipe on the BBC, click here.

7) GruelMade out of a thin mixture of oats and water or milk, gruel is famously affiliated with the Victorian workhouse, as seen in Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist.

To read the Cook it! recipe in full, click here.

Illustrations of decorative pies from Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management, 1861. (Credit: Culture Club/Getty Images)

Illustrations of decorative pies from Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management, 1861. (Credit: Culture Club/Getty Images) 1) Brown bread ice creamMade from a mixture of vanilla ice cream and caramelised wholemeal breadcrumbs, brown bread ice cream was a popular treat among the upper-class in the late 19th century.

To read the Cook it! recipe in full, click here.

2) Classic Victoria sandwichPossibly the most popular teatime treat in Britain, the Victoria sandwich is made of two simple sponges, with lashings of strawberry jam and cream layered in-between.

To read the BBC Good Food recipe in full, click here.

3) KedgereeBritish colonials based in India first created kedgeree during the 19th century. After they passed on their recipe to their friends back home, kedgeree became the staple of many breakfast tables across Britain. The dish is made of rice, smoked haddock and plenty of spice.

To read the Cook it! recipe in full, click here.

4) SyllabubSyllabub is a boozy yet creamy dessert, popular among the elite during the 17th and 18th centuries. Usually made with fortified wines such as sherry, this sweet treat also featured at high society banquets during the Victorian period.

To read Mrs Beeton's recipe on the BBC, click here.

5) Spotted dickMade from suet pastry, dried currants and raisins, spotted dick first appeared in The Modern Housewife cookbook by French chef Alexis Soyer in 1849. Serve this pudding with lashings of hot custard.

To read the BBC Good Food recipe in full, click here.

6) TeacakesThe perfect accompaniment to a strong cup of tea, teacakes are sweet buns filled with dried fruit. Usually toasted and smothered in butter, a recipe for teacakes is mentioned in Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management – the bestselling guide to running a home in the 19th century.

To read Mrs Beeton's recipe on the BBC, click here.

7) GruelMade out of a thin mixture of oats and water or milk, gruel is famously affiliated with the Victorian workhouse, as seen in Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist.

To read the Cook it! recipe in full, click here.

Published on April 12, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Battle of Carthage

April 12

238 Gordian II lost the Battle of Carthage against the Numidian forces loyal to Maximinus Thrax and was killed. Gordian I, his father, committed suicide

238 Gordian II lost the Battle of Carthage against the Numidian forces loyal to Maximinus Thrax and was killed. Gordian I, his father, committed suicide

Published on April 12, 2016 01:30

April 11, 2016

How the Vikings ruled the waves

History Extra

A depiction of Cnut the Great in a 14th-century genealogical roll of the kings and queens of England. Was Roskilde 6 built for this powerful Norse king? © AKG-British Library

A depiction of Cnut the Great in a 14th-century genealogical roll of the kings and queens of England. Was Roskilde 6 built for this powerful Norse king? © AKG-British Library

One of the most enduring images of the Viking Age in the popular imagination is the longship, with its dragonhead, row of shields, and large square sail. Unlike the equally popular horned helmet (a Romantic fabrication of the 19th century), the longship is a fitting symbol for the Norsemen. The 250 years between AD 800 and 1050 saw a remarkable expansion from the Scandinavian homelands of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, involving a combination of raiding, conquest, peaceful settlement and long-distance trade.

That same period saw the Vikings develop a remarkable network of international contacts that spread from eastern Canada in the west to central Asia in the east, and north Africa in the south. Many of these contacts were peaceful, and in recent years the Vikings have become known for more than just their established reputation as violent, devious raiders.

Having said that, this reputation was far from unfounded, and would have been all-too familiar to contemporaries around the Viking world. The Persian geographer Ibn Rusta’s assessment of the Vikings in Russia is damning: “Treachery is endemic, and a poor man can be envied by a comrade, who will not hesitate to kill him and rob him.” Meanwhile, you can almost feel an anonymous ninth-century Irish monk’s relief as he notes:

“The wind is sharp tonight,

It tosses the white hair of the sea,

I do not fear the crossing of the Clear Sea

[Irish Sea],

by the wild warriors of Lothlind [Vikings].”

This quotation reminds us of how far the Viking expansion relied on their ships: remarkable vessels that could carry settlers across the Atlantic, trade goods along the river systems of Russia, and be used with devastating effect in raids around Europe.

A memorial stone from Gotland, Sweden, depicts a Viking ship. Artwork celebrating Viking seamanship has been found everywhere from Dublin to Istanbul. © AKG Images

Charlemagne’s biographer Einhard tells us that the mighty Frankish emperor ordered fortifications to be built in every port and at the mouth of every navigable river to prevent Viking raids. If he did this, it was ineffective, and the ninth century saw repeated coastal raids, such as on Dorestad (in the modern-day Netherlands), and up the great rivers such as the Rhine, Loire and the Seine, with Vikings even attacking Paris.

Across the Channel, Vikings were able to sail their ships as far inland as Repton in Derbyshire, about as far from the sea as it is possible to get in Britain. They could do this because their ships were light and fast, with a shallow draft (the distance between the waterline and bottom of the hull). This could have unexpected benefits, as King Alfred the Great discovered to his cost in 896 when Viking and English fleets clashed in the mouth of an estuary in Dorset. During the battle, the ships of both sides ran aground or were beached, but when the tide returned, the less heavy Viking fleet was able to float off and escape Alfred’s clutches.

Vulnerable targetsIt wasn’t just the nature of the Vikings’ ships that set them apart though. It was also their ability to use their ships strategically – both along coasts and on rivers – that made them so effective as raiders. It was this, rather than any superior skills in battle (which they often avoided, preferring to hit softer, more vulnerable targets) that made them such a potent force in the early medieval world.

Not only could Vikings arrive and disappear suddenly, but the carrying capacity of their ships meant that they could be used as mobile supply dumps for provisions or loot, without the need for slow-moving and vulnerable supply trains on land. This enabled Viking forces to remain on campaign in hostile territory for years at a time. The ‘Great Raiding Army’ employed this advantage to devastating effect between 865 and 874, when it conquered the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of East Anglia, Northumbria and Mercia, and came close to subjugating the last surviving Anglo-Saxon kingdom, Wessex, in 877–78.

The Vikings’ skilled use of ships allowed them to be year-round campaigners, unlike some of their contemporaries, even attacking in the bleakest conditions. The notorious attack on Lindisfarne in 793 – in which Viking raiders apparently burned buildings, stole treasures and murdered monks – was recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as having taken place in January. Later editors found it so hard to believe that they could have launched this attack in the middle of winter and so changed the date to June, assuming that that was what the original had meant. In fact it had been January, a time when their assault would provide the maximum surprise.

All the same, Viking ships were vulnerable to bad weather. In 876 a Viking ‘ship army’ from East Anglia on their way to rendezvous with a ‘land army’ near Exeter “met with a great storm at sea, and all their ships were lost”. Even the discovery of America in the late 10th century, often lauded as one of the Vikings’ greatest navigational achievements, occurred when the Icelander Bjarni Herjolfsson was blown off course during a storm on his way to Greenland. According to later saga tradition, he did not land, but managed to work his way back to Greenland, where he sold his ship and never went to sea again.

If the Vikings could not control the weather – and Thor, whose hammer created thunder and lightning, seems to have been one of the most widely worshipped gods – they nevertheless had skills in shipbuilding and seamanship that went beyond those of most of their contemporaries. This is not surprising when you consider the landscape of the Viking homelands. With the exception of the Jutland peninsula, Denmark is an archipelago, and Norway is one long coastline, divided inland by the mountains.

While Sweden has more in the way of passable land, the 11th-century chronicler Adam of Bremen notes that it was possible to travel by ship from southern Sweden to Sigtuna on Lake Mälaren in eastern Sweden in five days, while the same journey overland would take a month. The Franks and Anglo-Saxons may have relied predominately on land travel, but it was the rivers and seas that kept the Vikings connected with each other and offered the best opportunities for wealth and expansion.

As a result, ships played a vital role in Scandinavian society in the Viking Age. Graffiti of Viking ships have been found everywhere from Dublin to Istanbul, and ship designs adorn coins, jewellery and monumental carvings. Even children too young to go on long voyages would be familiar with ships and boats for short journeys, and toy or model ships have been found at Viking sites in Scandinavia and overseas.

The Vikings also celebrated great sailors such as Bjorn Ironside and his brother Hastein, who supposedly led a remarkable raid down the Mediterranean in the mid-ninth century.

However, not all ships in the Viking Age matched the stereotypical image of the ‘longship’. As time went on, the Vikings became increasingly specialised as shipbuilders, creating vessels that were well adapted for particular circumstances. Archaeologists have discovered a wide variety of ship forms, including purpose-built warships (long and narrow) and cargo-ships (deep and broad), as well as others that could have combined the two functions.

This last group includes what probably remain the most famous – and certainly the most intact – ships excavated so far: the Oseberg ship (buried 832) and the Gokstad ship (buried c910), both of which hail from southern Norway. Both could carry a large number of men, but also boasted substantial storage space, which could be used for cargo, stores or loot.

These early ninth-century coins depicting Viking longships were probably minted in Hedeby, Denmark. © Bridgeman Art Library

So were the Vikings raiders or traders? The discovery of the Oseberg and Gokstad ships suggests that they were both. However, although it’s possible to distinguish – from the 10th century onwards, at least – between ships built for war and those built for commerce, raiding and trading were by no means mutually exclusive. This is nowhere more apparent than in the slave trade. Anglo-Saxon, Irish and Frankish sources reveal extensive raiding not just for loot, but for prisoners, who could then be either ransomed or sold as slaves. In 821, Vikings seized “a great number of women” from the Howth peninsula, north of Dublin, and took them into captivity. Fifty years later, in 871, Viking raiders from Dublin returned from the British kingdom of Strathclyde with “a great prey of Angles, Britons and Picts”.

The same Vikings might well be pirates or peaceful traders as circumstances demanded. The legitimacy of Viking activity (or the lack of it) probably depended in part on perspective, not least because the Vikings’ activities took them not just across the borders of different kingdoms but across the boundaries of different legal practices and social customs.

There are similarities here with Elizabethan sea captains such as Ralegh and Drake – romantic heroes to the English, heretic pirates to the Spanish. There are also echoes of the Vikings’ exploits in the China traders of the 19th century, another group of adventurers who trod the line between legal and illegal activity, and whose remarkable seamanship enabled them to develop trading links across the globe.

Status symbolsIf you’re looking for evidence of the sheer geographical scale of the Vikings’ maritime influence, then the discovery of vast numbers of Islamic coins in their hoards – along with whalebone from the North Atlantic and fragments of silk, both found in Viking towns such as Dublin and York – is surely it.

Viking ships were not, however, simply functional means of navigating the world’s oceans. Among a people who prized the virtues of seamanship so highly – and who loved to flaunt their riches – they were also a major symbol of wealth and status.

Even relatively small boats required a significant investment in labour. But the resources needed for building large ships were massive, including not just a combination of unskilled labour and large quantities of timber, but iron for rivets, wool or linen for sails, horse-hair, hide and flax or lime-bast for cordage. Ships were also routinely decorated with elaborate carvings or ornamented with precious metal, as this passage from the Encomium Emmae Reginae (1041–42) reveals: “Such, also, was the decoration of the ships, that… to those who were looking from afar they seemed [to be made] more of flame than of wood… Here shone the gleam of weapons, but there the flame of hanging shields. Gold burned on the prows, silver also shone on ships of various shapes.”

Individual vessels became famous in their own right, as well as providing a reflection of their owner’s spending power and status. For example, the Long Serpent, boasting 34 rowing benches, was built for King Olaf Tryggvasson of Norway just before AD 1000, and was long remembered as the largest ship ever built. The Icelandic saga compiler Snorri Sturluson, writing around 230 years later, noted that the stocks on which the ship had been built were still visible in his own time.

During the building of this ship, the prow-wright Thorberg Shave-stroke had been so disappointed with the design that one night he vandalised it, hacking wedges out of the planks. When King Olaf discovered the damage he threatened to kill the perpetrator. Shave-stroke owned up to the king, explaining that he felt the planking had been executed poorly and requesting the chance to fix it, on pain of death if his work did not please Olaf. In the end the king was so impressed with Shave-stroke’s changes that he was put in charge of completing the Long Serpent and went on to become a ‘celebrity’ shipbuilder.

Even more impressive than the Long Serpent was the longship known as Roskilde 6. At over 37 metres, this is the longest Viking ship yet discovered. It was excavated in 1996–97 (along with eight later ships) during the construction, as chance would have it, of an extension of the Viking Ship Museum at Roskilde.

Anything over 30 pairs of oars was considered large in the Viking Age. With 39 or 40, Roskilde 6 was exceptional, and there is also evidence that the ship was decorated with ornamental carving.

Both the size and the ornamentation suggest a very high-status vessel, and possibly one built for a king, or at least for the royal fleet. Intriguingly, analysis of the timbers shows that the ship was constructed in southern Norway around AD 1025. Cnut the Great conquered England in 1016, and ruled both England and Denmark until his death in 1035. In 1028 he also conquered Norway, driving his rival Olaf Haraldsson (later St Olaf) into exile, and creating a North Sea empire unparalleled before or since. Roskilde 6 may have been built by Olaf in an attempt to resist Cnut’s expansion, but it could also have been made for Cnut to celebrate his conquest of the timber resources around the Oslo Fjord.

For the British Museum exhibition we have reassembled the surviving timbers of Roskilde 6, which is appearing in Britain for the first time. It is a magnificent sight and there can be little better confirmation of the Vikings’ skills in shipbuilding and the importance of the sea to their colourful history.

Going down with the ship: the importance of boats to Viking burialsIf ships were important in life for the Vikings, they also had a symbolic importance in death. Ships were used in a variety of funerary practices, although there is some debate among scholars as to whether they simply reflected the wealth of the deceased – ship burials typically feature other expensive grave goods – or whether they represented the voyage to the afterlife.

Stones depict the outline of a ship in this Viking burial near Aalborg in Jutland. © Rex Features

The latter can perhaps be seen in the stones from Gotland in the Baltic. Designs vary but a widespread combination of motifs on the stones shows a ship below a mounted figure arriving at a hall, sometimes being greeted by a woman bearing a horn of mead or ale. This is usually interpreted as a representation of the voyage to the afterlife, and the arrival of the deceased at Valhöll, the ‘Hall of the Slain’.

There were three separate funerary practices in which ships were directly associated with burial. The first is ship burial itself. Some of these were richly furnished, but others were on a less lavish scale, with smaller boat burials recorded around the Viking world, including examples from Scotland and the Isle of Man. These were the graves of chieftains rather than kings or queens, but still represent significant wealth.

Burial in actual ships was not always practicable. An alternative burial practice was to symbolise the ship by erecting stones in the shape of a ship around the grave, sometimes with larger stones representing the stem and stern.

A longship in flames at an Up Helly Aa festival – marking the end of the Yule season – in Shetland. For many, the image of a burning ship is synonymous with the Vikings. © Alamy

A final burial rite involving ships is understandably more difficult to substantiate archaeologically, but has captured the popular imagination more than any other. The idea of burning a ship with its owner in it is recorded in a late and mythological account of the funeral of the god Baldr, who was cremated in his ship Hringhorni along with his heartbroken wife, Nanna, and a dwarf who was accidentally kicked into the flames.

This story has some parallels with an account by the 10th-century Arab traveller Ahmad ibn Fadlãn, who describes the funeral of a Viking chieftain on the Volga c922. In this account the chieftain was cremated in his ship along with a slave girl, who was sacrificed so that she could accompany her master. This is consistent with the presence in the boat burial of a wealthy man at Balladoole, Isle of Man, of a female skeleton showing signs of a violent death.

Raised from the dead: evidence of the Vikings’ mastery of the seas1) The longest longship

A section of the bottom of Roskilde 6 is shown below, during its excavation in Zealand, Denmark in 1997. This is the longest Viking ship yet discovered and boasted 39 or 40 pairs of oars, when anything over 30 was considered large.

Roskilde 6. © National Museum of Denmark

2) Fit for a queen?

The Oseberg ship (below), is widely regarded as one of the finest finds from the Viking Age. The ship was buried in the 830s, and discovered in 1904. The burial contained two women, with a variety of expensive grave goods, suggesting that at least one of the women was of royal status.

3) In prime condition

The Gokstad ship (pictured below). Along with the Oseberg ship, this is one of the two best-preserved, and most celebrated, Viking boats in existence. It was built in the mid-890s and buried in c910 in southern Norway.

4) The face of power

Viking ships were often adorned with elaborate carvings, designed to draw attention to the owner’s wealth and status. Contemporary accounts suggest that the finest warships had dragon-head prows. None have survived intact, but they probably resembled the carved post from the Oseberg burial, pictured below.

Carved dragon head from the Oseberg burial. © Bridgeman Art Library

Gareth Williams was the curator of the 2014 Exhibition Vikings: Life and Legend at the British Museum.

A depiction of Cnut the Great in a 14th-century genealogical roll of the kings and queens of England. Was Roskilde 6 built for this powerful Norse king? © AKG-British Library

A depiction of Cnut the Great in a 14th-century genealogical roll of the kings and queens of England. Was Roskilde 6 built for this powerful Norse king? © AKG-British Library One of the most enduring images of the Viking Age in the popular imagination is the longship, with its dragonhead, row of shields, and large square sail. Unlike the equally popular horned helmet (a Romantic fabrication of the 19th century), the longship is a fitting symbol for the Norsemen. The 250 years between AD 800 and 1050 saw a remarkable expansion from the Scandinavian homelands of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, involving a combination of raiding, conquest, peaceful settlement and long-distance trade.

That same period saw the Vikings develop a remarkable network of international contacts that spread from eastern Canada in the west to central Asia in the east, and north Africa in the south. Many of these contacts were peaceful, and in recent years the Vikings have become known for more than just their established reputation as violent, devious raiders.

Having said that, this reputation was far from unfounded, and would have been all-too familiar to contemporaries around the Viking world. The Persian geographer Ibn Rusta’s assessment of the Vikings in Russia is damning: “Treachery is endemic, and a poor man can be envied by a comrade, who will not hesitate to kill him and rob him.” Meanwhile, you can almost feel an anonymous ninth-century Irish monk’s relief as he notes:

“The wind is sharp tonight,

It tosses the white hair of the sea,

I do not fear the crossing of the Clear Sea

[Irish Sea],

by the wild warriors of Lothlind [Vikings].”

This quotation reminds us of how far the Viking expansion relied on their ships: remarkable vessels that could carry settlers across the Atlantic, trade goods along the river systems of Russia, and be used with devastating effect in raids around Europe.

A memorial stone from Gotland, Sweden, depicts a Viking ship. Artwork celebrating Viking seamanship has been found everywhere from Dublin to Istanbul. © AKG Images

Charlemagne’s biographer Einhard tells us that the mighty Frankish emperor ordered fortifications to be built in every port and at the mouth of every navigable river to prevent Viking raids. If he did this, it was ineffective, and the ninth century saw repeated coastal raids, such as on Dorestad (in the modern-day Netherlands), and up the great rivers such as the Rhine, Loire and the Seine, with Vikings even attacking Paris.

Across the Channel, Vikings were able to sail their ships as far inland as Repton in Derbyshire, about as far from the sea as it is possible to get in Britain. They could do this because their ships were light and fast, with a shallow draft (the distance between the waterline and bottom of the hull). This could have unexpected benefits, as King Alfred the Great discovered to his cost in 896 when Viking and English fleets clashed in the mouth of an estuary in Dorset. During the battle, the ships of both sides ran aground or were beached, but when the tide returned, the less heavy Viking fleet was able to float off and escape Alfred’s clutches.

Vulnerable targetsIt wasn’t just the nature of the Vikings’ ships that set them apart though. It was also their ability to use their ships strategically – both along coasts and on rivers – that made them so effective as raiders. It was this, rather than any superior skills in battle (which they often avoided, preferring to hit softer, more vulnerable targets) that made them such a potent force in the early medieval world.

Not only could Vikings arrive and disappear suddenly, but the carrying capacity of their ships meant that they could be used as mobile supply dumps for provisions or loot, without the need for slow-moving and vulnerable supply trains on land. This enabled Viking forces to remain on campaign in hostile territory for years at a time. The ‘Great Raiding Army’ employed this advantage to devastating effect between 865 and 874, when it conquered the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of East Anglia, Northumbria and Mercia, and came close to subjugating the last surviving Anglo-Saxon kingdom, Wessex, in 877–78.

The Vikings’ skilled use of ships allowed them to be year-round campaigners, unlike some of their contemporaries, even attacking in the bleakest conditions. The notorious attack on Lindisfarne in 793 – in which Viking raiders apparently burned buildings, stole treasures and murdered monks – was recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as having taken place in January. Later editors found it so hard to believe that they could have launched this attack in the middle of winter and so changed the date to June, assuming that that was what the original had meant. In fact it had been January, a time when their assault would provide the maximum surprise.

All the same, Viking ships were vulnerable to bad weather. In 876 a Viking ‘ship army’ from East Anglia on their way to rendezvous with a ‘land army’ near Exeter “met with a great storm at sea, and all their ships were lost”. Even the discovery of America in the late 10th century, often lauded as one of the Vikings’ greatest navigational achievements, occurred when the Icelander Bjarni Herjolfsson was blown off course during a storm on his way to Greenland. According to later saga tradition, he did not land, but managed to work his way back to Greenland, where he sold his ship and never went to sea again.

If the Vikings could not control the weather – and Thor, whose hammer created thunder and lightning, seems to have been one of the most widely worshipped gods – they nevertheless had skills in shipbuilding and seamanship that went beyond those of most of their contemporaries. This is not surprising when you consider the landscape of the Viking homelands. With the exception of the Jutland peninsula, Denmark is an archipelago, and Norway is one long coastline, divided inland by the mountains.

While Sweden has more in the way of passable land, the 11th-century chronicler Adam of Bremen notes that it was possible to travel by ship from southern Sweden to Sigtuna on Lake Mälaren in eastern Sweden in five days, while the same journey overland would take a month. The Franks and Anglo-Saxons may have relied predominately on land travel, but it was the rivers and seas that kept the Vikings connected with each other and offered the best opportunities for wealth and expansion.

As a result, ships played a vital role in Scandinavian society in the Viking Age. Graffiti of Viking ships have been found everywhere from Dublin to Istanbul, and ship designs adorn coins, jewellery and monumental carvings. Even children too young to go on long voyages would be familiar with ships and boats for short journeys, and toy or model ships have been found at Viking sites in Scandinavia and overseas.

The Vikings also celebrated great sailors such as Bjorn Ironside and his brother Hastein, who supposedly led a remarkable raid down the Mediterranean in the mid-ninth century.

However, not all ships in the Viking Age matched the stereotypical image of the ‘longship’. As time went on, the Vikings became increasingly specialised as shipbuilders, creating vessels that were well adapted for particular circumstances. Archaeologists have discovered a wide variety of ship forms, including purpose-built warships (long and narrow) and cargo-ships (deep and broad), as well as others that could have combined the two functions.

This last group includes what probably remain the most famous – and certainly the most intact – ships excavated so far: the Oseberg ship (buried 832) and the Gokstad ship (buried c910), both of which hail from southern Norway. Both could carry a large number of men, but also boasted substantial storage space, which could be used for cargo, stores or loot.

These early ninth-century coins depicting Viking longships were probably minted in Hedeby, Denmark. © Bridgeman Art Library

So were the Vikings raiders or traders? The discovery of the Oseberg and Gokstad ships suggests that they were both. However, although it’s possible to distinguish – from the 10th century onwards, at least – between ships built for war and those built for commerce, raiding and trading were by no means mutually exclusive. This is nowhere more apparent than in the slave trade. Anglo-Saxon, Irish and Frankish sources reveal extensive raiding not just for loot, but for prisoners, who could then be either ransomed or sold as slaves. In 821, Vikings seized “a great number of women” from the Howth peninsula, north of Dublin, and took them into captivity. Fifty years later, in 871, Viking raiders from Dublin returned from the British kingdom of Strathclyde with “a great prey of Angles, Britons and Picts”.

The same Vikings might well be pirates or peaceful traders as circumstances demanded. The legitimacy of Viking activity (or the lack of it) probably depended in part on perspective, not least because the Vikings’ activities took them not just across the borders of different kingdoms but across the boundaries of different legal practices and social customs.

There are similarities here with Elizabethan sea captains such as Ralegh and Drake – romantic heroes to the English, heretic pirates to the Spanish. There are also echoes of the Vikings’ exploits in the China traders of the 19th century, another group of adventurers who trod the line between legal and illegal activity, and whose remarkable seamanship enabled them to develop trading links across the globe.

Status symbolsIf you’re looking for evidence of the sheer geographical scale of the Vikings’ maritime influence, then the discovery of vast numbers of Islamic coins in their hoards – along with whalebone from the North Atlantic and fragments of silk, both found in Viking towns such as Dublin and York – is surely it.

Viking ships were not, however, simply functional means of navigating the world’s oceans. Among a people who prized the virtues of seamanship so highly – and who loved to flaunt their riches – they were also a major symbol of wealth and status.

Even relatively small boats required a significant investment in labour. But the resources needed for building large ships were massive, including not just a combination of unskilled labour and large quantities of timber, but iron for rivets, wool or linen for sails, horse-hair, hide and flax or lime-bast for cordage. Ships were also routinely decorated with elaborate carvings or ornamented with precious metal, as this passage from the Encomium Emmae Reginae (1041–42) reveals: “Such, also, was the decoration of the ships, that… to those who were looking from afar they seemed [to be made] more of flame than of wood… Here shone the gleam of weapons, but there the flame of hanging shields. Gold burned on the prows, silver also shone on ships of various shapes.”

Individual vessels became famous in their own right, as well as providing a reflection of their owner’s spending power and status. For example, the Long Serpent, boasting 34 rowing benches, was built for King Olaf Tryggvasson of Norway just before AD 1000, and was long remembered as the largest ship ever built. The Icelandic saga compiler Snorri Sturluson, writing around 230 years later, noted that the stocks on which the ship had been built were still visible in his own time.

During the building of this ship, the prow-wright Thorberg Shave-stroke had been so disappointed with the design that one night he vandalised it, hacking wedges out of the planks. When King Olaf discovered the damage he threatened to kill the perpetrator. Shave-stroke owned up to the king, explaining that he felt the planking had been executed poorly and requesting the chance to fix it, on pain of death if his work did not please Olaf. In the end the king was so impressed with Shave-stroke’s changes that he was put in charge of completing the Long Serpent and went on to become a ‘celebrity’ shipbuilder.

Even more impressive than the Long Serpent was the longship known as Roskilde 6. At over 37 metres, this is the longest Viking ship yet discovered. It was excavated in 1996–97 (along with eight later ships) during the construction, as chance would have it, of an extension of the Viking Ship Museum at Roskilde.

Anything over 30 pairs of oars was considered large in the Viking Age. With 39 or 40, Roskilde 6 was exceptional, and there is also evidence that the ship was decorated with ornamental carving.

Both the size and the ornamentation suggest a very high-status vessel, and possibly one built for a king, or at least for the royal fleet. Intriguingly, analysis of the timbers shows that the ship was constructed in southern Norway around AD 1025. Cnut the Great conquered England in 1016, and ruled both England and Denmark until his death in 1035. In 1028 he also conquered Norway, driving his rival Olaf Haraldsson (later St Olaf) into exile, and creating a North Sea empire unparalleled before or since. Roskilde 6 may have been built by Olaf in an attempt to resist Cnut’s expansion, but it could also have been made for Cnut to celebrate his conquest of the timber resources around the Oslo Fjord.

For the British Museum exhibition we have reassembled the surviving timbers of Roskilde 6, which is appearing in Britain for the first time. It is a magnificent sight and there can be little better confirmation of the Vikings’ skills in shipbuilding and the importance of the sea to their colourful history.

Going down with the ship: the importance of boats to Viking burialsIf ships were important in life for the Vikings, they also had a symbolic importance in death. Ships were used in a variety of funerary practices, although there is some debate among scholars as to whether they simply reflected the wealth of the deceased – ship burials typically feature other expensive grave goods – or whether they represented the voyage to the afterlife.

Stones depict the outline of a ship in this Viking burial near Aalborg in Jutland. © Rex Features

The latter can perhaps be seen in the stones from Gotland in the Baltic. Designs vary but a widespread combination of motifs on the stones shows a ship below a mounted figure arriving at a hall, sometimes being greeted by a woman bearing a horn of mead or ale. This is usually interpreted as a representation of the voyage to the afterlife, and the arrival of the deceased at Valhöll, the ‘Hall of the Slain’.

There were three separate funerary practices in which ships were directly associated with burial. The first is ship burial itself. Some of these were richly furnished, but others were on a less lavish scale, with smaller boat burials recorded around the Viking world, including examples from Scotland and the Isle of Man. These were the graves of chieftains rather than kings or queens, but still represent significant wealth.

Burial in actual ships was not always practicable. An alternative burial practice was to symbolise the ship by erecting stones in the shape of a ship around the grave, sometimes with larger stones representing the stem and stern.

A longship in flames at an Up Helly Aa festival – marking the end of the Yule season – in Shetland. For many, the image of a burning ship is synonymous with the Vikings. © Alamy

A final burial rite involving ships is understandably more difficult to substantiate archaeologically, but has captured the popular imagination more than any other. The idea of burning a ship with its owner in it is recorded in a late and mythological account of the funeral of the god Baldr, who was cremated in his ship Hringhorni along with his heartbroken wife, Nanna, and a dwarf who was accidentally kicked into the flames.

This story has some parallels with an account by the 10th-century Arab traveller Ahmad ibn Fadlãn, who describes the funeral of a Viking chieftain on the Volga c922. In this account the chieftain was cremated in his ship along with a slave girl, who was sacrificed so that she could accompany her master. This is consistent with the presence in the boat burial of a wealthy man at Balladoole, Isle of Man, of a female skeleton showing signs of a violent death.

Raised from the dead: evidence of the Vikings’ mastery of the seas1) The longest longship

A section of the bottom of Roskilde 6 is shown below, during its excavation in Zealand, Denmark in 1997. This is the longest Viking ship yet discovered and boasted 39 or 40 pairs of oars, when anything over 30 was considered large.

Roskilde 6. © National Museum of Denmark

2) Fit for a queen?

The Oseberg ship (below), is widely regarded as one of the finest finds from the Viking Age. The ship was buried in the 830s, and discovered in 1904. The burial contained two women, with a variety of expensive grave goods, suggesting that at least one of the women was of royal status.

3) In prime condition

The Gokstad ship (pictured below). Along with the Oseberg ship, this is one of the two best-preserved, and most celebrated, Viking boats in existence. It was built in the mid-890s and buried in c910 in southern Norway.

4) The face of power

Viking ships were often adorned with elaborate carvings, designed to draw attention to the owner’s wealth and status. Contemporary accounts suggest that the finest warships had dragon-head prows. None have survived intact, but they probably resembled the carved post from the Oseberg burial, pictured below.

Carved dragon head from the Oseberg burial. © Bridgeman Art Library

Gareth Williams was the curator of the 2014 Exhibition Vikings: Life and Legend at the British Museum.

Published on April 11, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Llywelyn ap Iorweth, Prince of Gwynedd, dies

April 11

1240 Llywelyn ap Iorweth, Prince of Gwynedd, died. Llywelyn the Great managed to unite most of Wales under his control, but most of his reign was marked by conflict with King John of England, whose illegitimate daughter Joan was Llywelyn's wife.

1240 Llywelyn ap Iorweth, Prince of Gwynedd, died. Llywelyn the Great managed to unite most of Wales under his control, but most of his reign was marked by conflict with King John of England, whose illegitimate daughter Joan was Llywelyn's wife.

Published on April 11, 2016 01:00

April 10, 2016

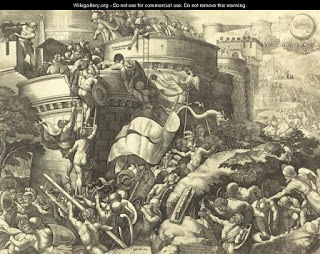

Evidence for Vikings in Canada Grows with Surprising Find of Ironworking Site in Newfoundland

Ancient Origins

Ancient OriginsExperts are “cautiously optimistic” that a hearth where people worked iron about 1,000 years ago in Newfoundland, Northeast Canada, was the site of a Viking settlement, says National Geographic.

[image error][image error]This site, at Point Rosee, is the second where there is strong evidence of Viking settlements in the New World. The first, at L’Anse aux Meadows, also in Newfoundland but hundreds of miles north of Point Rosee, was discovered in 1960.The hearth at Point Rosee is surrounded by the remnants of a rectangular turf wall, says the National Geographic article announcing the find. The hearth itself is just a boulder with a depression in front of it, surrounded by smaller rocks.

But in the hearth’s shallow pit archaeologists found 28 pounds of slag—a byproduct of iron roasting, the step in the ironworking process before smelting and forging. The smith burns and dries the ore in the fire so it doesn’t explode in the forge.

A blackened rock said to be the hearth. Slag was found around the boulder. (

Dan Snow

)Scholars do not believe natives of this area in the 11th century were working with iron, though there was metalworking in the New World before Europeans arrived.

A blackened rock said to be the hearth. Slag was found around the boulder. (

Dan Snow

)Scholars do not believe natives of this area in the 11th century were working with iron, though there was metalworking in the New World before Europeans arrived.The Point Rosee Viking site is the southernmost and westernmost location where evidence of ironworking has been discovered in the Americas before Columbus arrived.

Did a Native American travel with the Vikings and arrive in Iceland centuries before Columbus set sail?Norsemen transformed international culture, manufacturing, tech and trade during Viking EraNew study shows Viking women accompanied men on voyages to colonize far-flung landsThe method of the discovery is noteworthy, too. “Space archaeologist” and National Geographic fellow Sarah Parcak, working with a $1 million TED prize, used satellite imagery to find evidence of human activity in the landscape. She usually studies satellite imagery of Egypt to find signs of ancient human activity there but recently expanded her horizons.

At Point Rosee, she saw a faint difference in the vegetation in the form of a rectangle—possibly a structure. Investigations on-site showed the turf walls and hearth.

The site has bog iron, natural deposits of the metal that would have been very attractive to Vikings. It has other features, too, that may have attracted the wandering Norsemen.

The southern coast of the Point Rosee peninsula has few submerged rocks, allowing beaching of ships or anchoring in shallow water.

There was good farm land, plenty of good fishing and a lot of game they could have hunted, National Geographic says. Other things that may have attracted the Vikings include turf for constructing houses and chert for making stone tools.

The researchers found what they believe to be evidence of Norse grass walls at their dig site in Point Rosee in Newfoundland. (

BBC

)Parcak told The Washington Post that there is nothing that “absolutely confirms the site as Norse.” She said: “This is going to take years of careful excavation, and it’s going to be controversial. It raises a lot more questions than it answers. But, that’s what any new discovery is supposed to do.”

The researchers found what they believe to be evidence of Norse grass walls at their dig site in Point Rosee in Newfoundland. (

BBC

)Parcak told The Washington Post that there is nothing that “absolutely confirms the site as Norse.” She said: “This is going to take years of careful excavation, and it’s going to be controversial. It raises a lot more questions than it answers. But, that’s what any new discovery is supposed to do.”National Geographic says the most valuable resource for the site was the iron, which formed as rivers carried ore from the mountains into wetlands, where bacteria leached iron from water and left behind the metal.

A lump of what the researchers say is bog iron ore. It is one of the samples being tested from the possible Viking site at Point Rosee. (

Greg Mumford

)Instead of mining, the Vikings usually harvested iron from peat bogs, and they needed a lot of it for the nails they used to construct the ships they roamed much of the world in. One reconstructed Norse longship needed 7,000 nails—880 pounds (400 kilograms) of iron, which would have required a blacksmith to heat and smelt 30 tons of raw iron ore.

A lump of what the researchers say is bog iron ore. It is one of the samples being tested from the possible Viking site at Point Rosee. (

Greg Mumford

)Instead of mining, the Vikings usually harvested iron from peat bogs, and they needed a lot of it for the nails they used to construct the ships they roamed much of the world in. One reconstructed Norse longship needed 7,000 nails—880 pounds (400 kilograms) of iron, which would have required a blacksmith to heat and smelt 30 tons of raw iron ore.Viking Longhouse Discovery Rewrites the History of Icelandic Capital CityDid the Vikings use crystal sunstones to discover America?Archaeologist to delve into Viking presence in SpainArchaeologists say the structure found at Point Rosee is unlike native construction and also unlike the construction of Basque fishermen and whalers who visited 16th century Newfoundland. And the only people who would have been working with bog iron were the Vikings, Doug Bolender, an archaeologist and expert in Viking settlements, told National Geographic.

Bolender says there is documentary evidence for the Norse in North America:

“The sagas suggest a short period of activity and a very brief and failed colonization attempt. L’Anse aux Meadows fits well with that story but is only one site. Point Rosee could reinforce that story or completely change it if the dating is different from L’Anse aux Meadows. We could end up with a much longer period of Norse activity in the New World. A site like Point Rosee has the potential to reveal what that initial wave of Norse colonization looked like not only for Newfoundland but for the rest of the North Atlantic.”L’Anse aux Meadows showed the sagas weren’t entirely fictional, National Geographic says. The sagas and now even more physical evidence show the Norse probably did venture west from Europe and their Greenland settlements.

Archaeologists conducted small-scale dig to search for initial evidence that the site merits further study. (

Robert Clark, National Geographic

)Other evidence of Vikings in the New World include a copper coin and other artifacts of the 11th century found in the U.S. state of Maine. Scholars have speculated the things were obtained by natives trading with Norse people.

Archaeologists conducted small-scale dig to search for initial evidence that the site merits further study. (

Robert Clark, National Geographic

)Other evidence of Vikings in the New World include a copper coin and other artifacts of the 11th century found in the U.S. state of Maine. Scholars have speculated the things were obtained by natives trading with Norse people.Ms. Parcak’s documentary film Vikings Unearthed will be broadcast on American public television the week of April 3.

Featured Image: Artistic representation of a Viking ship. ( CC BY 3.0 ) Detail of Newfoundland from an 1858 map of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Island. ( Public Domain )

By Mark Miller

Published on April 10, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - birth of James V of Scotland

April 10

1512 James V of Scotland was born. His only legitimate child to survive to adulthood was Mary, Queen of Scots. His illegitimate son, the Earl of Moray, became regent of Scotland when Mary abdicated.

1512 James V of Scotland was born. His only legitimate child to survive to adulthood was Mary, Queen of Scots. His illegitimate son, the Earl of Moray, became regent of Scotland when Mary abdicated.

Published on April 10, 2016 01:00

April 9, 2016

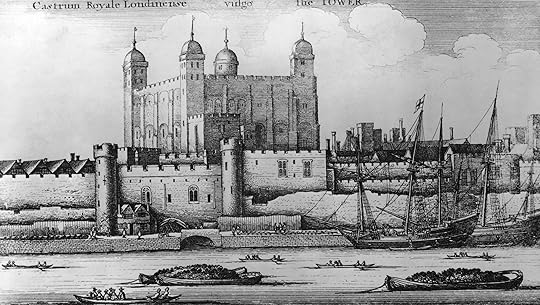

Anne Boleyn, Guy Fawkes and the princes: a brief history of the Tower of London

History Extra

'The Young Princes in the Tower', 1831. (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

'The Young Princes in the Tower', 1831. (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

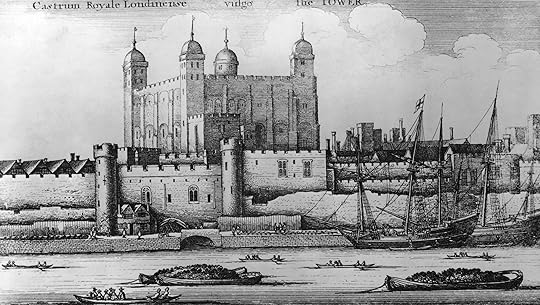

The Tower of London was founded by William the Conqueror after his famous victory at Hastings in 1066. Using part of the huge defensive Roman wall, known as London Wall, William’s men began building a mighty fortress to subdue the inhabitants of London. A wooden castle was erected at first, but in around 1075–79 work began on the gigantic keep, or ‘great tower’ (later called the White Tower), which formed the heart of what from the 12th century became known as the Tower of London.

Although it was built as a fortress and royal residence, it wasn’t long before the tower took on a number of other – more surprising – roles. In 1204, for example, King John established a royal menagerie there. Upon losing Normandy that year he had been given the bizarre consolation prize of three crate-loads of wild beasts. Having nowhere else suitable to keep them, he settled for the tower.

John’s son, Henry III, embraced this aspect of the tower’s role with enthusiasm, and it was during his reign that the royal menagerie was fully established. Most exotic of all Henry III’s animals was the ‘pale bear’ (probably a polar bear) – a gift from the King of Norway in 1252. Three years later, the bear was joined by a beast so strange that even the renowned chronicler Matthew Paris was at a loss for words. He could only say that it “eats and drinks with a trunk”. England had welcomed the first elephant in England since the invasion of Claudius.

It was also during the 13th century that the tower embraced another function that might not be expected of a fortress. Determined to keep the production of coins under closer control, Edward I moved the mint here in 1279. His choice was inspired by the need for security: after all, the mint’s workers literally held the wealth of the kingdom in their hands. So successful was the operation that it would remain at the tower until the late 18th century.

At around the same time that the mint was established, the tower also became home to the records of government. For centuries the monarch had kept these documents with them wherever they travelled, but the growing volume forced them to be stored in a permanent – and very secure – space. During Edward I’s reign, the tower became a major repository of these records. Purpose-built storage for the records was never provided there, however, so they competed for space with weapons, gunpowder, prisoners and even royalty. As with the mint, they would remain there for many centuries to come.

The Tower of London as seen from the River Thames, 1647. From an engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Rebel invadersIt was said that he who held London held the kingdom, and the tower was the key to the capital. It is for that reason that it was always the target for rebels and invaders.

One of the most notorious occasions was the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, which was prompted by the introduction of a new ‘poll’ tax by Richard II’s government. Under the leadership of the charismatic Walter (or Wat) Tyler, in June 1381 20,000 rebels marched on the capital and headed straight for the Tower of London. The king agreed to meet them, but as soon as the gates were opened to let him out, 400 rebels rushed in.

Ransacking their way to the innermost parts of the fortress, they reached the second floor of the White Tower and burst into St John’s Chapel, where they found the despised Archbishop of Canterbury, Simon Sudbury, leading prayers. Without hesitation they dragged him and his companions to Tower Hill and butchered them. It took eight blows of the amateur executioner’s axe to sever the archbishop’s head, which was then set upon a pole on London Bridge.

Meanwhile, inside the tower, the mob had ransacked the king’s bedchamber and molested his mother and her ladies. The contemporary chronicler Jean Froissart described how the rebels “arrogantly lay and sat and joked on the king’s bed, whilst several asked the king’s mother… to kiss them”. Steeled into more decisive action, her son rode out to meet the rebels again and faced down their leader, Wat Tyler, who was slain by the king’s men. Without his charismatic presence, the rebels lost the will to fight on and returned meekly to their homes.

The princes in the TowerDespite such dramatic events as this, it is the Tower of London’s history as a prison that has always held the most fascination. Between 1100 and 1952 some 8,000 people were incarcerated within its walls for crimes ranging from treason and conspiracy to murder, debt and sorcery.

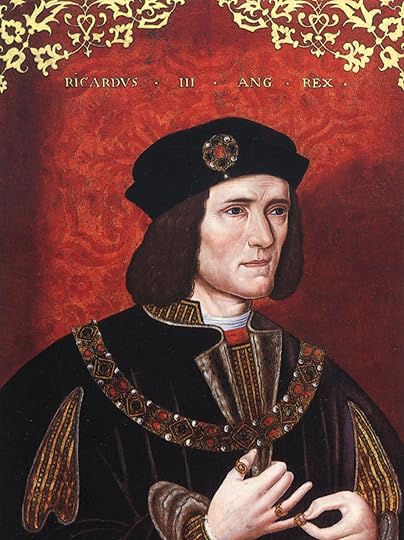

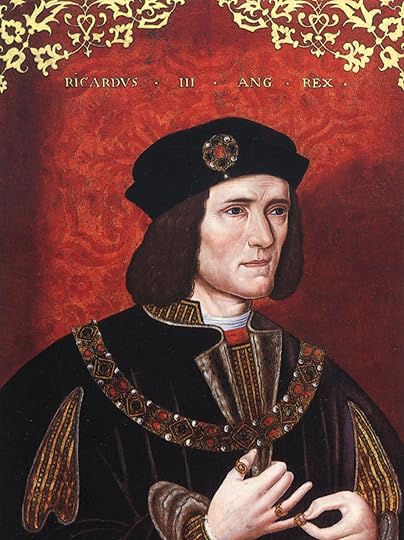

One of the most notorious episodes involved the ‘Princes in the Tower’. Upon the death of Edward IV in 1483, his son and heir Edward was just 12 years old so he appointed his brother Richard (the future Richard III) as Lord Protector. Richard wasted no time in placing the boy and his younger brother Richard in the tower, ostensibly for their protection. What happened next has been the subject of intense debate ever since.

It is now widely accepted that some time during the autumn of that year the two princes were quietly murdered. At whose hands, it will probably never be known. The prime suspect has long been Richard III, who had invalidated his nephews’ claim to the throne and had himself crowned king in July 1483. But there were others with a vested interest in getting the princes out of the way.

The two princes had apparently disappeared without trace, but in 1674 a remarkable discovery was made at the tower. The then king, Charles II, ordered the demolition of what remained of the royal palace to the south of the White Tower, including a turret that had once contained a privy staircase leading into St John’s Chapel. Beneath the foundations of the staircase the workmen were astonished to find a wooden chest containing two skeletons. They were clearly the bones of children and their height coincided with the age of the two princes when they disappeared.

Charles II eventually arranged for their reburial in Westminster Abbey. They lie there still, with a brief interruption in 1933 when a re-examination provided compelling evidence that they were the two princes. The controversy surrounding their death was reignited by the discovery of Richard III’s skeleton in Leicester in 2012 and shows no sign of abating.

Richard III, date unknown. (Photo by Apic/Getty Images)

Angry TudorsThe Tudor period witnessed more victims of royal wrath than any other. This was the era in which a staggering number of high profile statesmen, churchmen and even queens went to the block. The fortress came to epitomise the brutality of the Tudor regime, and of its most famous king, Henry VIII.

The most famous of the tower’s prisoners during the Tudor era was Henry VIII’s notorious second queen, Anne Boleyn. High-handed and “unqueenly”, Anne soon made dangerous enemies at court. Among them was the king’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, who was almost certainly responsible for her downfall. He drew inspiration from the queen’s flirtatious manner with her coterie of male favourites and convinced the king that she was conducting adulterous affairs with five of them – her own brother included.

Cromwell had them all rounded up and the queen herself was arrested on 2 May 1536. She was taken by barge to the tower, stoutly protesting her innocence all the way, and incarcerated in the same apartments that had been refurbished for her coronation in 1533.

Anne watched as her five alleged lovers were led to their deaths on Tower Hill on 17 May. Two days later she was taken from her apartments to the scaffold. After a dignified speech she knelt in the straw and closed her eyes to pray. With a clean strike, the executioner severed her head from her body. The crowd looked on aghast as the fallen queen’s eyes and lips continued to move, as if in silent prayer, when the head was held aloft.

Anne’s nemesis, Thomas Cromwell, had been among the onlookers at this macabre spectacle. His triumph would be short-lived. Four years later he was arrested on charges of treason by the captain of the royal guard and conveyed by barge to the tower. He may have been housed in the same lodgings that Anne had been kept in before her execution.

The beheading of Anne Boleyn, image dated c1754. (Photo by Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

The Gunpowder PlotThe death of Elizabeth I in 1603 signalled the end of the Tudor dynasty, but the Tower of London retained its reputation as a place of imprisonment and terror. When it became clear that the new king, James I, had no intention of following Elizabeth’s policy of religious toleration, a group of conspirators led by Robert Catesby hatched a plan to blow up the House of Lords during the state opening of parliament on 5 November 1605. It was only thanks to an anonymous letter to the authorities that the king and his Protestant regime were not wiped out. The House of Lords was searched at around midnight on 4 November, just hours before the plot was due to be executed, and Guy Fawkes was discovered with 36 barrels of gunpowder – more than enough to reduce the entire building to rubble.

Fawkes was taken straight to the tower, along with his fellow plotters. They were interrogated in the Queen’s House, close to the execution site. Fawkes eventually confessed, after suffering the agony of the rack – a torture device consisting of a frame suspended above the ground with a roller at both ends. The victim’s ankles and wrists were fastened at either end and when the axles were turned slowly the victim’s joints would be dislocated. The shaky signature on Fawkes’ confession suggests that he was barely able to hold a pen.

Fawkes and his fellow conspirators met a grisly traitor’s death at Westminster in January 1606. It is said that the gunpowder with which they had planned to obliterate James’s regime was taken to the tower for safekeeping.

The Tower of London was again at the centre of the action during the disastrous reign of James’s son, Charles I, when the country descended into civil war. After Charles’s execution, Oliver Cromwell ordered the destruction of the crown jewels – the most potent symbols of royal power – almost all of which were melted down in the Tower Mint. But upon the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Charles II commissioned a dazzling suite of new jewels that have been used by the royal family ever since. They are now the most popular attraction within the tower.

Although the Tower of London subsequently fell out of use as a royal residence, it remained key to the nation’s defence. The Duke of Wellington, who was constable of the tower during the mid-19th century, stripped away many of its non-military functions, notably the menagerie, and built impressive new accommodation for its garrison, which became known as the Waterloo Block. This is now home to the crown jewels.