MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 109

April 3, 2016

Ramesses III was Murdered by Multiple Assailants Then Received Postmortem Cosmetic Surgery to Hide it

Ancient Origins

A theory about the assassination of Ramesses III has been confirmed by researchers at the University in Cairo. They say that he was killed by multiple assailants and given postmortem cosmetic surgery to hide this fact.

A theory about the assassination of Ramesses III has been confirmed by researchers at the University in Cairo. They say that he was killed by multiple assailants and given postmortem cosmetic surgery to hide this fact.

[image error]Ramesses III (ruled 1186 BC – 1155 BC) was a pharaoh of the New Kingdom Period. Some revealing information about his death has been published in a new book by Egyptologist Zahi Hawas and the Cairo University radiologist Sahar Saleem. Their work is entitled Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies (American University in Cairo Press, 2016).

According to Live Science, Hawass and Saleem studied royal mummies from the 18th to 20th dynasties of Egypt, spanning from about 1543 BC to 1064 BC. They examined the mummies of famous pharaohs like Hatshepsut, Tutankhamun, Thutmose III, Seti I, etc. All of the mummies were from the collection of the Cairo Museum. With new technology the remains of the ancient royals became a priceless source of information.

CT imaging shows a detailed view of King Tut’s mummified skull – including the resin embalmers filled it with. (

Sahar Saleem

)Details have been discovered about the medical conditions from which they may have suffered, as well as the mummification processes they underwent, their age, and causes of their death. Using Multi-Detector Computed Tomography and DNA analysis, Hawass and Saleem completed research which has provided more information on the mummies than ever before. Moreover, utilizing 3D images, the anatomy of each face has been discerned for a more accurate interpretation of facial features.

CT imaging shows a detailed view of King Tut’s mummified skull – including the resin embalmers filled it with. (

Sahar Saleem

)Details have been discovered about the medical conditions from which they may have suffered, as well as the mummification processes they underwent, their age, and causes of their death. Using Multi-Detector Computed Tomography and DNA analysis, Hawass and Saleem completed research which has provided more information on the mummies than ever before. Moreover, utilizing 3D images, the anatomy of each face has been discerned for a more accurate interpretation of facial features.

The Battle of the Delta: Ramses III saves Egypt from the People of the SeaArchaeological dig at ancient fortress site in Egypt reveals massive gate and graves of fallen warriorsThe Discovery of Nedjmet and the Secret Cache of MummiesThe recent research has also uncovered new information connected to the genealogy and relationship between people whose mummified bodies are a part of the exhibition in Cairo. One of the most surprising stories appeared during the scanning of the mummy of Ramesses III.

The mummy of pharaoh Ramesses III. (Theban Royal Mummy Project)Previously, the same team reported that Ramesses III's throat was slit, likely killing him instantly. Now, they have made a new discovery connected with his assassination. The toe of the pharaoh was hacked off, likely with an ax - suggesting that he was set upon by multiple assailants with different weapons.

The mummy of pharaoh Ramesses III. (Theban Royal Mummy Project)Previously, the same team reported that Ramesses III's throat was slit, likely killing him instantly. Now, they have made a new discovery connected with his assassination. The toe of the pharaoh was hacked off, likely with an ax - suggesting that he was set upon by multiple assailants with different weapons.

As Saleem wrote in an email to Live Science:

A three-dimensional CT scan of the feet of Ramesses III, showing the thick linen wrappings.

A three-dimensional CT scan of the feet of Ramesses III, showing the thick linen wrappings.

(Sahar Saleem and Zahi Hawass)The body of Ramesses III was mummified, but before it happened, ancient specialists of mummification conducted cosmetic surgery on the body. They placed packing materials under his skin to "plump out" the corpse and make him look more attractive for his journey to the afterlife. They also tried to hide cuts on his body. He received a postmortem prosthesis to allow him to have a complete body in the Afterlife as well.

The Life and Death of Ramesses IIMaat: The Ancient Egyptian Goddess of Truth, Justice and MoralityThe Fierce Amorites and the First King of the Babylonian Empire"This hid the big secret beneath the wrappings. It seems to me that this was the intention of the ancient Egyptian embalmers, to deliberately pour large amounts of resin to glue the layers of linen wrappings to the body and feet." Saleem said to Live Science.

Sarcophagus box of Ramesses III. (Public Domain)There is an ancient papyrus which documents the plot of killing Ramesses III. The court document tells the tale of a harem conspiracy, which cost Ramesses III his life. The story says that he was murdered by his wives, or at least one of them – Tiye. It is believed that she did it because of succession issues. Tiye was the mother of Pentawere, who was in line for the throne after his half-brother, known later as Ramesses IV. It seems that Tiye and other members of the royal harem decided to kill the pharaoh and install Pentawere as the ruler.

Sarcophagus box of Ramesses III. (Public Domain)There is an ancient papyrus which documents the plot of killing Ramesses III. The court document tells the tale of a harem conspiracy, which cost Ramesses III his life. The story says that he was murdered by his wives, or at least one of them – Tiye. It is believed that she did it because of succession issues. Tiye was the mother of Pentawere, who was in line for the throne after his half-brother, known later as Ramesses IV. It seems that Tiye and other members of the royal harem decided to kill the pharaoh and install Pentawere as the ruler.

What's more interesting is that some researchers, including Zahi Hawass and Bob Brier, believe the so-called “Screaming Mummy,” also known as Unknown Man E, is Pentawere. This may be evidence that he helped his mother in a fight for his succession.

The mummy of Unknown Man E. (

National Geographic Society

)According to the researchers, he looks like he was poisoned. They are convinced, however, that he died of suffocation or strangulation. Moreover, the mummy was found without a grave marking, which would have prevented him from reaching the afterlife. This action was a typical way for the ancient Egyptians to punish a person who committed a horrible crime. However, he was well mummified, which suggests that this man had a strong position on the court.

The mummy of Unknown Man E. (

National Geographic Society

)According to the researchers, he looks like he was poisoned. They are convinced, however, that he died of suffocation or strangulation. Moreover, the mummy was found without a grave marking, which would have prevented him from reaching the afterlife. This action was a typical way for the ancient Egyptians to punish a person who committed a horrible crime. However, he was well mummified, which suggests that this man had a strong position on the court.

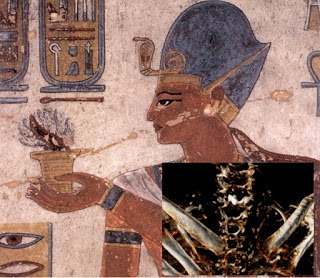

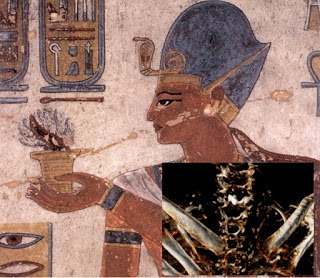

The uninscribed coffin of Unknown Man E with inset photo of interior. (Pat Remler/www.archeology.org)Featured Image: Ramesses III offering incense, wall painting in KV11. (

Public Domain

) Detail: A CT scan depicting a sharp knife wound in Ramesses III’s neck with an amulet placed within to promote healing. (

Sahar Saleem

)

The uninscribed coffin of Unknown Man E with inset photo of interior. (Pat Remler/www.archeology.org)Featured Image: Ramesses III offering incense, wall painting in KV11. (

Public Domain

) Detail: A CT scan depicting a sharp knife wound in Ramesses III’s neck with an amulet placed within to promote healing. (

Sahar Saleem

)

By Natalia Klimczak

A theory about the assassination of Ramesses III has been confirmed by researchers at the University in Cairo. They say that he was killed by multiple assailants and given postmortem cosmetic surgery to hide this fact.

A theory about the assassination of Ramesses III has been confirmed by researchers at the University in Cairo. They say that he was killed by multiple assailants and given postmortem cosmetic surgery to hide this fact.[image error]Ramesses III (ruled 1186 BC – 1155 BC) was a pharaoh of the New Kingdom Period. Some revealing information about his death has been published in a new book by Egyptologist Zahi Hawas and the Cairo University radiologist Sahar Saleem. Their work is entitled Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies (American University in Cairo Press, 2016).

According to Live Science, Hawass and Saleem studied royal mummies from the 18th to 20th dynasties of Egypt, spanning from about 1543 BC to 1064 BC. They examined the mummies of famous pharaohs like Hatshepsut, Tutankhamun, Thutmose III, Seti I, etc. All of the mummies were from the collection of the Cairo Museum. With new technology the remains of the ancient royals became a priceless source of information.

CT imaging shows a detailed view of King Tut’s mummified skull – including the resin embalmers filled it with. (

Sahar Saleem

)Details have been discovered about the medical conditions from which they may have suffered, as well as the mummification processes they underwent, their age, and causes of their death. Using Multi-Detector Computed Tomography and DNA analysis, Hawass and Saleem completed research which has provided more information on the mummies than ever before. Moreover, utilizing 3D images, the anatomy of each face has been discerned for a more accurate interpretation of facial features.

CT imaging shows a detailed view of King Tut’s mummified skull – including the resin embalmers filled it with. (

Sahar Saleem

)Details have been discovered about the medical conditions from which they may have suffered, as well as the mummification processes they underwent, their age, and causes of their death. Using Multi-Detector Computed Tomography and DNA analysis, Hawass and Saleem completed research which has provided more information on the mummies than ever before. Moreover, utilizing 3D images, the anatomy of each face has been discerned for a more accurate interpretation of facial features.The Battle of the Delta: Ramses III saves Egypt from the People of the SeaArchaeological dig at ancient fortress site in Egypt reveals massive gate and graves of fallen warriorsThe Discovery of Nedjmet and the Secret Cache of MummiesThe recent research has also uncovered new information connected to the genealogy and relationship between people whose mummified bodies are a part of the exhibition in Cairo. One of the most surprising stories appeared during the scanning of the mummy of Ramesses III.

The mummy of pharaoh Ramesses III. (Theban Royal Mummy Project)Previously, the same team reported that Ramesses III's throat was slit, likely killing him instantly. Now, they have made a new discovery connected with his assassination. The toe of the pharaoh was hacked off, likely with an ax - suggesting that he was set upon by multiple assailants with different weapons.

The mummy of pharaoh Ramesses III. (Theban Royal Mummy Project)Previously, the same team reported that Ramesses III's throat was slit, likely killing him instantly. Now, they have made a new discovery connected with his assassination. The toe of the pharaoh was hacked off, likely with an ax - suggesting that he was set upon by multiple assailants with different weapons.As Saleem wrote in an email to Live Science:

"The site of foot injury is anatomically far from the neck-cut wound; also the shape of the fractured toe bones indicate that it was induced by a different weapon than that used to induce the neck cut. So there must have been an assailant with an ax/sword attacking the king from the front, and another one with a knife or a dagger attacking the king from his back, both attacking at the same time."

A three-dimensional CT scan of the feet of Ramesses III, showing the thick linen wrappings.

A three-dimensional CT scan of the feet of Ramesses III, showing the thick linen wrappings.(Sahar Saleem and Zahi Hawass)The body of Ramesses III was mummified, but before it happened, ancient specialists of mummification conducted cosmetic surgery on the body. They placed packing materials under his skin to "plump out" the corpse and make him look more attractive for his journey to the afterlife. They also tried to hide cuts on his body. He received a postmortem prosthesis to allow him to have a complete body in the Afterlife as well.

The Life and Death of Ramesses IIMaat: The Ancient Egyptian Goddess of Truth, Justice and MoralityThe Fierce Amorites and the First King of the Babylonian Empire"This hid the big secret beneath the wrappings. It seems to me that this was the intention of the ancient Egyptian embalmers, to deliberately pour large amounts of resin to glue the layers of linen wrappings to the body and feet." Saleem said to Live Science.

Sarcophagus box of Ramesses III. (Public Domain)There is an ancient papyrus which documents the plot of killing Ramesses III. The court document tells the tale of a harem conspiracy, which cost Ramesses III his life. The story says that he was murdered by his wives, or at least one of them – Tiye. It is believed that she did it because of succession issues. Tiye was the mother of Pentawere, who was in line for the throne after his half-brother, known later as Ramesses IV. It seems that Tiye and other members of the royal harem decided to kill the pharaoh and install Pentawere as the ruler.

Sarcophagus box of Ramesses III. (Public Domain)There is an ancient papyrus which documents the plot of killing Ramesses III. The court document tells the tale of a harem conspiracy, which cost Ramesses III his life. The story says that he was murdered by his wives, or at least one of them – Tiye. It is believed that she did it because of succession issues. Tiye was the mother of Pentawere, who was in line for the throne after his half-brother, known later as Ramesses IV. It seems that Tiye and other members of the royal harem decided to kill the pharaoh and install Pentawere as the ruler.What's more interesting is that some researchers, including Zahi Hawass and Bob Brier, believe the so-called “Screaming Mummy,” also known as Unknown Man E, is Pentawere. This may be evidence that he helped his mother in a fight for his succession.

The mummy of Unknown Man E. (

National Geographic Society

)According to the researchers, he looks like he was poisoned. They are convinced, however, that he died of suffocation or strangulation. Moreover, the mummy was found without a grave marking, which would have prevented him from reaching the afterlife. This action was a typical way for the ancient Egyptians to punish a person who committed a horrible crime. However, he was well mummified, which suggests that this man had a strong position on the court.

The mummy of Unknown Man E. (

National Geographic Society

)According to the researchers, he looks like he was poisoned. They are convinced, however, that he died of suffocation or strangulation. Moreover, the mummy was found without a grave marking, which would have prevented him from reaching the afterlife. This action was a typical way for the ancient Egyptians to punish a person who committed a horrible crime. However, he was well mummified, which suggests that this man had a strong position on the court. The uninscribed coffin of Unknown Man E with inset photo of interior. (Pat Remler/www.archeology.org)Featured Image: Ramesses III offering incense, wall painting in KV11. (

Public Domain

) Detail: A CT scan depicting a sharp knife wound in Ramesses III’s neck with an amulet placed within to promote healing. (

Sahar Saleem

)

The uninscribed coffin of Unknown Man E with inset photo of interior. (Pat Remler/www.archeology.org)Featured Image: Ramesses III offering incense, wall painting in KV11. (

Public Domain

) Detail: A CT scan depicting a sharp knife wound in Ramesses III’s neck with an amulet placed within to promote healing. (

Sahar Saleem

)By Natalia Klimczak

Published on April 03, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Edward the Confessor crowned King of England

April 3

1043 Edward the Confessor was crowned King of England. Elected by popular acclamation, Edward (known as "the Confessor" for his piety) had Norman sympathies and had supposedly named William the Conqueror his successor, before choosing Harold Godwinson on his death-bed.

1043 Edward the Confessor was crowned King of England. Elected by popular acclamation, Edward (known as "the Confessor" for his piety) had Norman sympathies and had supposedly named William the Conqueror his successor, before choosing Harold Godwinson on his death-bed.

Published on April 03, 2016 01:00

April 2, 2016

A brief history of how people communicated in the Middle Ages

History Extra

c1500: a medieval friar preaches to his congregation in the open air from a moveable pulpit. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

c1500: a medieval friar preaches to his congregation in the open air from a moveable pulpit. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Official speechIn 14th and 15th-century England, as the Hundred Years’ War raged in France, towns and villages heard about events through official speech – primarily through their priests. The church communicated the successes (or setbacks) of their king to the populace: they required masses or procession for thanksgiving in light of a victory, and prayers and invocations for hopes of a success at the start of campaigns. This helped to build public support for wars and the taxes to pay for them.

Official news could be delivered in both written and oral form. The towns of the late medieval Low Countries (modern Belgium and the Netherlands) were ruled by the powerful Dukes of Burgundy. Charters issued by the dukes were written communications, setting out new rights, laws or taxes, but they also carried a significant aural quality: charters would have been read out at specific places in towns, known as bretèches, or in churches or at important civic events.

Rumour and subversive communicationCommunication of legislation was important for medieval rulers, but, as today, people were also able to spread rumours and gossip. It is not always clear where medieval, or indeed modern, rumours began, but there is no doubt that they could spread quickly.

In the second half of the 14th century, England saw great upheaval and challenges: the war with France was going badly, and at home the Black Death, beginning in 1348–9, had killed at least a third of the population. Survivors might have hoped for better conditions, as a smaller work force tried to demand higher wages, but this was stopped by the Ordinance and Statute of Labourers setting wages at the pre-plague level.

In 1381 this famously erupted into the violence of the Peasants’ Revolt, but in 1377 there were already signs of discontent, manifested in the ‘Great Rumour’. This social movement, spread by word of mouth across southern England, saw rural labourers refusing to work, arguing that the Domesday Book granted them exemptions form their feudal services.

Messengers and networksIn 12th-century England, kings did not stay in London – rather, they travelled around their lands. This necessitated an organised and efficient messenger service, ensuring that correspondence reached the king, and that royal letters, grants, patents and orders arrived at their intended destination. Messengers therefore became a permanent royal expenditure, paid continuously and travelling the kingdom to carry the king’s word.

The English system was efficient, allowing news to be carried quickly: in 1290 Edward I summoned a parliament to grant new taxes. The order, or writ, for the taxes was issued on 22 September at Edward’s hunting lodge in King’s Clipstone, in the Midlands. This was carried to the Privy Seal Office and then to the Barons of the Exchequer, in Westminster. The Exchequer then issued its own writs on 6 October to the sheriffs, ordering them to begin collections between the 18th and 29th of the month.

Thus, less than a month after Edward’s order, his messages had been transmitted to London and then out to the counties, and commissioners had begun their task.

Visual communicationAs well as sending written messages, hearing official news from their priests, or listening to rumours spread form village to village, medieval people could also see messages. Late medieval clothing carried layers of meaning, and can be considered a potent means of communication – this is to an extent true also of the modern world, with black for funerals or badges and wrist bands to support causes.

On the battlefield, banners and coats of arms showed armies’ friend from foe, and royal standards enabled soldiers to see where their king was located. Coats of arms further marked out who was of a noble rank, and so worth taking prisoner, and who was not, meaning that being well dressed was about far more than vanity.

The wearing of badges and livery – clothes that bore a symbol, or particular colours or designs – marked out allegiance and community. Though their survival is rare, pilgrim badges were very common: they marked out those who had been on a religious journey, and acted as a souvenir, worn to show that one was devout and had visited Canterbury, or even Rome.

Guilds used badges or liveries to mark out their members, ensuring that anyone looking to buy goods or services in the medieval town would recognise a guild members from less reputable trades – visual forms of identification showed belonging and communicated identify and status.

Laura Crombie is a lecturer in late medieval history at the University of York.

c1500: a medieval friar preaches to his congregation in the open air from a moveable pulpit. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

c1500: a medieval friar preaches to his congregation in the open air from a moveable pulpit. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Official speechIn 14th and 15th-century England, as the Hundred Years’ War raged in France, towns and villages heard about events through official speech – primarily through their priests. The church communicated the successes (or setbacks) of their king to the populace: they required masses or procession for thanksgiving in light of a victory, and prayers and invocations for hopes of a success at the start of campaigns. This helped to build public support for wars and the taxes to pay for them.

Official news could be delivered in both written and oral form. The towns of the late medieval Low Countries (modern Belgium and the Netherlands) were ruled by the powerful Dukes of Burgundy. Charters issued by the dukes were written communications, setting out new rights, laws or taxes, but they also carried a significant aural quality: charters would have been read out at specific places in towns, known as bretèches, or in churches or at important civic events.

Rumour and subversive communicationCommunication of legislation was important for medieval rulers, but, as today, people were also able to spread rumours and gossip. It is not always clear where medieval, or indeed modern, rumours began, but there is no doubt that they could spread quickly.

In the second half of the 14th century, England saw great upheaval and challenges: the war with France was going badly, and at home the Black Death, beginning in 1348–9, had killed at least a third of the population. Survivors might have hoped for better conditions, as a smaller work force tried to demand higher wages, but this was stopped by the Ordinance and Statute of Labourers setting wages at the pre-plague level.

In 1381 this famously erupted into the violence of the Peasants’ Revolt, but in 1377 there were already signs of discontent, manifested in the ‘Great Rumour’. This social movement, spread by word of mouth across southern England, saw rural labourers refusing to work, arguing that the Domesday Book granted them exemptions form their feudal services.

Messengers and networksIn 12th-century England, kings did not stay in London – rather, they travelled around their lands. This necessitated an organised and efficient messenger service, ensuring that correspondence reached the king, and that royal letters, grants, patents and orders arrived at their intended destination. Messengers therefore became a permanent royal expenditure, paid continuously and travelling the kingdom to carry the king’s word.

The English system was efficient, allowing news to be carried quickly: in 1290 Edward I summoned a parliament to grant new taxes. The order, or writ, for the taxes was issued on 22 September at Edward’s hunting lodge in King’s Clipstone, in the Midlands. This was carried to the Privy Seal Office and then to the Barons of the Exchequer, in Westminster. The Exchequer then issued its own writs on 6 October to the sheriffs, ordering them to begin collections between the 18th and 29th of the month.

Thus, less than a month after Edward’s order, his messages had been transmitted to London and then out to the counties, and commissioners had begun their task.

Visual communicationAs well as sending written messages, hearing official news from their priests, or listening to rumours spread form village to village, medieval people could also see messages. Late medieval clothing carried layers of meaning, and can be considered a potent means of communication – this is to an extent true also of the modern world, with black for funerals or badges and wrist bands to support causes.

On the battlefield, banners and coats of arms showed armies’ friend from foe, and royal standards enabled soldiers to see where their king was located. Coats of arms further marked out who was of a noble rank, and so worth taking prisoner, and who was not, meaning that being well dressed was about far more than vanity.

The wearing of badges and livery – clothes that bore a symbol, or particular colours or designs – marked out allegiance and community. Though their survival is rare, pilgrim badges were very common: they marked out those who had been on a religious journey, and acted as a souvenir, worn to show that one was devout and had visited Canterbury, or even Rome.

Guilds used badges or liveries to mark out their members, ensuring that anyone looking to buy goods or services in the medieval town would recognise a guild members from less reputable trades – visual forms of identification showed belonging and communicated identify and status.

Laura Crombie is a lecturer in late medieval history at the University of York.

Published on April 02, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Edmund Rich becomes Archbishop of Canterbury

April 2

1234 Edmund Rich became Archbishop of Canterbury. Raised to the Archbishopric by Pope Gregory IX, Edmund was an outspoken figure who clashed with King Henry III of England and preached for the Sixth Crusade.

1234 Edmund Rich became Archbishop of Canterbury. Raised to the Archbishopric by Pope Gregory IX, Edmund was an outspoken figure who clashed with King Henry III of England and preached for the Sixth Crusade.

Published on April 02, 2016 01:30

April 1, 2016

7 of England’s best medieval buildings

History Extra

Aerial view of Westminster Abbey at night. (Pawel Libera/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Aerial view of Westminster Abbey at night. (Pawel Libera/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Westminster Abbey London’s iconic Westminster Abbey has since the medieval period held a significant place in royal history. It has been the setting of every royal coronation since 1066, seen 16 royal weddings and is the final resting place of 17 English monarchs. The stunning Gothic structure that stands today was constructed by Henry III between 1245 and 1272, and his motivations for undertaking the mammoth building project are intriguing. Writing for History Extra in 2011, historian David Carpenter has argued that Henry built the spectacular abbey to win the favour of the dead Anglo-Saxon king, Edward the Confessor, who had established a church on the site almost 200 years earlier, in 1065. According to Carpenter, Henry was “passionately devoted to Edward”, who had been canonised in 1161, adopting him as his patron saint. He says Henry believed that “if he won the dead king’s saintly favour by building the magnificent abbey as an offering to him, Edward would support him in this life and shepherd him into the next. The Abbey was a very clear statement that Henry was backed by his saintly predecessor”. Westminster Abbey is home to some remarkable medieval art, including England’s oldest altarpiece, the 13th-century Westminster Retable [a panel painted with religious imagery, including an image of Westminster Abbey’s patron saint St Peter]. After surviving the dissolution of the monasteries, the Reformation and the Civil War, this precious altarpiece was rediscovered 1725, covered in paint and being used as a cupboard door in the Abbey’s storage. Another of Westminster Abbey’s outstanding medieval artefacts is the coronation chair, in which every monarch since Edward II (apart from Edward V and Edward VIII) has been crowned. During the Second World War the coronation chair was evacuated to Gloucester Cathedral, however, like the Westminster Retable, it has not always received such good care. Its back is marked with graffiti, carved by mischievous Westminster schoolboys in the 18th and 19th centuries. Dover Castle Known as ‘the key to England’, the defensive fortress of Dover Castle has a long and turbulent history. Standing at the site of the shortest sea crossing between England and the continent, Dover has always been a key strategic spot in the defence of the kingdom, and over the centuries its castle has witnessed several bloody conflicts. The medieval structure that remains at Dover today was mostly constructed by King Henry II in the 1180s. Henry spent a vast fortune on the castle, which was not only intended to defend the British coast but also to entertain and impress distinguished guests. Between 1179 and his death in 1189, Henry spent £5,991 on Dover Castle – the greatest concentration of money spent on a single castle in English history. Writing for History Extra, John Gillingham has argued that Henry poured such vast sums into the impressive structure in order to “save face” following the brutal killing of Thomas Becket in 1170. The archbishop had been murdered in Henry’s name, significantly damaging Henry’s reputation. According to Gillingham, constructing the imposing castle was “a visible assertion of Henry’s power in the face of a developing anti-monarchical cult.” It served as stopping point a for high-status pilgrims visiting Beckets’s tomb at Canterbury Cathedral and Henry dedicated its chapel to the canonised Archbishop. During the reign of King John (r1199–1216), the castle defences were put to the test when it came under siege by French troops led by Prince Louis in 1216–17. It withstood 10 months of bombardment as the invasion forces targeted it with siege engines, tunneling and face-to-face combat.

Dover Castle. (Photo by Olaf Protze/LightRocket via Getty Images) Rievaulx Abbey A dramatic ruin set in the beautiful surroundings of rural North Yorkshire, Rievaulx Abbey was once a template for medieval monastic architecture across Europe. The Abbey underwent many stages of architectural development from the 12th to 15th centuries, reflecting the social and economic changes monastic communities underwent during the period. Rievaulx was first established as a Cistercian monastery in 1132. The Cisterian order (founded by St Bernard of Clairvaux in 1098 in an attempt to reform monastic life in Europe) aimed to return holy communities to an austere life, abiding to strict religious guidelines set down by St Benedict in the sixth century. After the foundation of Britain’s first Cistercian abbey in 1128 (Waverley Abbey in Surrey) the waves of reform quickly spread, and other Cistercian communities such as Rievaulx were established across the country. By the middle of the 12th century Rievaulx was a large and thriving self-sufficient community. In 1167 the Abbey’s community numbered around 140 monks and around 500 lay brothers. A larger site was needed to accommodate this growing community, leading to the building of a new chapter house and a dramatic, imposing church. The Abbey site was designed to facilitate both religious and practical aspects of life. In addition to a great cloister where the monks could study and read, the Abbey also contained private quarters for more senior monks, as well as a parlour, dormitory and kitchen. Rievaulx also holds the earliest surviving infirmary complex on any British Cistercian site, built in the 1150s to care for sick and elderly members of the monastic community. Like many abbeys, Rievaulx was targeted by Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s. However, the Abbey’s religious population had dwindled over the centuries and by the time it was shut down and dismantled in 1538 only 23 monks remained there.

The ruins of Rievaulx Abbey, North Yorkshire. (English Heritage/Heritage Images/Getty Images) York MinsterFrom humble beginnings as a small wooden church, York Minster underwent several transformations during the medieval period before evolving into the spectacular Gothic cathedral that stands today. The first Christian church on the site was a modest wooden structure dating back to AD 627. By AD 640 King Oswald had replaced this with a small stone church. After surviving the Viking invasion in AD 866, York’s Anglo-Saxon church was ransacked by William the Conqueror’s forces in the Harrying of the North in 1069. After destroying the Anglo-Saxon church, William appointed his own Norman archbishop of York, who went about constructing a grand Norman Cathedral on the site. In the 13th century Walter De Gray (archbishop of York between 1215 and 1255) decided to rebuild the cathedral for the final time. He embarked on a mammoth project to redesign it in a dramatic Gothic style, with a monumental arching roof, intended to convey a sense of soaring upwards towards the sky. Constructed between 1220 and 1472, the magnificent Gothic-style minster took more than 250 years to complete. Its Great East Window, glazed by John Thornton of Coventry between 1405 and 1408, is now the largest expanse of medieval glass to have survived in Europe. York Minster has suffered many misfortunes over the centuries. In 1407 the central tower collapsed due to soft soil, and four fires [in 1753, 1829, 1840 and 1984] have wreaked significant damage. York Minster is now one of only seven cathedrals in the world to boast its own police force [a small, specialized cathedral constabulary who continue to operate independently of the rest of the city’s police force].

York Minster at night. (Rod Lawton/Digital Camera Magazine via Getty Images) The White TowerThe imposing White Tower at the heart of the Tower of London complex dates back to the late 11th century. Built by William the Conqueror to secure his hold on London, it was designed to awe and subdue the local population. The exact construction dates of the White Tower are unclear, but building was certainly underway in the 1070s and was completed by 1100. A key example of Norman architecture, the White Tower was the first building of its kind in England. William employed Norman masons and even had stone imported from Normandy for its construction. At 27.5m tall the Tower would have been visible for miles around. Intended as a fortress and stronghold rather than a royal palace, the White Tower’s design favoured defence over hospitality. Its fortifications were updated throughout the medieval period and during the reign of Richard the Lionheart they doubled in size. This proved to be a wise move, as in Richard’s absence his brother John besieged the White Tower in an attempt to seize the throne. The Tower’s defences held fast but the forces defending it [led by Richard’s Chancellor William Longchamp] were compelled to surrender owing to a lack of supplies. For those who fell from royal favour, the White Tower was a place of imprisonment and execution. From its foundation it was used as a prison – the first recorded prisoner held in the White Tower was Ranulf Flambard, bishop of Durham, in 1100. Under Edward III, the captured kings of Scotland and France were kept at the White Tower and it is believed that, centuries later, Guy Fawkes was tortured and interrogated in the White Tower’s basement. Even monarchs were not immune to imprisonment at the White Tower: in 1399 Richard II was imprisoned there after being forced to renounce his throne by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke.

The White Tower at the Tower of London. (Arcaid/UIG via Getty)

Westminster Hall, Houses of Parliament As the oldest building on the parliamentary estate, Westminster Hall has been central to the government of England since the 11th century. Built in 1097 by the Norman king William II (the son of William the Conqueror and known as Rufus), the Hall was a symbol of Norman majesty intended to impress the king’s new subjects. Rufus’s construction project was remarkably ambitious. Covering a floor space of 1,547 square metres (with walls two metres thick), Westminster Hall was by far the largest hall in England at the time. It was so large that when surveying the vast hall just after its construction, one of Rufus’s attendants reportedly remarked it was far bigger than it needed to be. However, Rufus himself was less than impressed – he replied it was not half large enough, a mere bedchamber compared to what he had in mind. Recent archaeological explorations at Westminster Hall have prompted some fascinating theories about the groundbreaking nature of its original construction. No evidence of columns used to support the vast roof has been uncovered, suggesting that it may have been self-supporting. This engineering would have been remarkably ahead of its time, as self-supporting roofs of this size were not seen elsewhere until the 13th and 14th centuries. Writing for History Extra, Paul Binski suggests that the “miracle” of Westminster Hall “is not just its survival, but its courage. The builders of these great structures had brilliant know-how, but also guts”.

A royal event at Westminster Hall in 2012. (Ben Stansall/WPA Pool/Getty)

Norwich Guildhall Situated in the centre of the medieval city, the Norwich Guildhall is a remarkable example of late medieval secular architecture. Built primarily between 1407 and 1412, its grandeur reflects the growing power and wealth of a new elite of merchants, traders and government agents during the period. By the 15th century Norwich had become one of the wealthiest and most important towns in England. Following a 1404 charter granting the city greater self–governing powers it was decided that a Guildhall should be built in order to administer the powers more effectively. The Guildhall fulfilled a role similar to that of a modern town hall, performing all the administrative functions the city required to govern the everyday lives of the city’s residents. The Guildhall served multiple purposes as a court, a tax collection hub and administrative centre. The Guildhall also contained an assembly chamber for council meetings, was equipped to hold prisoners and had a large ‘sword room’ used for storing weapons. Today the Guildhall is the largest surviving medieval building intended for a civic purpose outside of London.

Aerial view of Westminster Abbey at night. (Pawel Libera/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Aerial view of Westminster Abbey at night. (Pawel Libera/LightRocket via Getty Images) Westminster Abbey London’s iconic Westminster Abbey has since the medieval period held a significant place in royal history. It has been the setting of every royal coronation since 1066, seen 16 royal weddings and is the final resting place of 17 English monarchs. The stunning Gothic structure that stands today was constructed by Henry III between 1245 and 1272, and his motivations for undertaking the mammoth building project are intriguing. Writing for History Extra in 2011, historian David Carpenter has argued that Henry built the spectacular abbey to win the favour of the dead Anglo-Saxon king, Edward the Confessor, who had established a church on the site almost 200 years earlier, in 1065. According to Carpenter, Henry was “passionately devoted to Edward”, who had been canonised in 1161, adopting him as his patron saint. He says Henry believed that “if he won the dead king’s saintly favour by building the magnificent abbey as an offering to him, Edward would support him in this life and shepherd him into the next. The Abbey was a very clear statement that Henry was backed by his saintly predecessor”. Westminster Abbey is home to some remarkable medieval art, including England’s oldest altarpiece, the 13th-century Westminster Retable [a panel painted with religious imagery, including an image of Westminster Abbey’s patron saint St Peter]. After surviving the dissolution of the monasteries, the Reformation and the Civil War, this precious altarpiece was rediscovered 1725, covered in paint and being used as a cupboard door in the Abbey’s storage. Another of Westminster Abbey’s outstanding medieval artefacts is the coronation chair, in which every monarch since Edward II (apart from Edward V and Edward VIII) has been crowned. During the Second World War the coronation chair was evacuated to Gloucester Cathedral, however, like the Westminster Retable, it has not always received such good care. Its back is marked with graffiti, carved by mischievous Westminster schoolboys in the 18th and 19th centuries. Dover Castle Known as ‘the key to England’, the defensive fortress of Dover Castle has a long and turbulent history. Standing at the site of the shortest sea crossing between England and the continent, Dover has always been a key strategic spot in the defence of the kingdom, and over the centuries its castle has witnessed several bloody conflicts. The medieval structure that remains at Dover today was mostly constructed by King Henry II in the 1180s. Henry spent a vast fortune on the castle, which was not only intended to defend the British coast but also to entertain and impress distinguished guests. Between 1179 and his death in 1189, Henry spent £5,991 on Dover Castle – the greatest concentration of money spent on a single castle in English history. Writing for History Extra, John Gillingham has argued that Henry poured such vast sums into the impressive structure in order to “save face” following the brutal killing of Thomas Becket in 1170. The archbishop had been murdered in Henry’s name, significantly damaging Henry’s reputation. According to Gillingham, constructing the imposing castle was “a visible assertion of Henry’s power in the face of a developing anti-monarchical cult.” It served as stopping point a for high-status pilgrims visiting Beckets’s tomb at Canterbury Cathedral and Henry dedicated its chapel to the canonised Archbishop. During the reign of King John (r1199–1216), the castle defences were put to the test when it came under siege by French troops led by Prince Louis in 1216–17. It withstood 10 months of bombardment as the invasion forces targeted it with siege engines, tunneling and face-to-face combat.

Dover Castle. (Photo by Olaf Protze/LightRocket via Getty Images) Rievaulx Abbey A dramatic ruin set in the beautiful surroundings of rural North Yorkshire, Rievaulx Abbey was once a template for medieval monastic architecture across Europe. The Abbey underwent many stages of architectural development from the 12th to 15th centuries, reflecting the social and economic changes monastic communities underwent during the period. Rievaulx was first established as a Cistercian monastery in 1132. The Cisterian order (founded by St Bernard of Clairvaux in 1098 in an attempt to reform monastic life in Europe) aimed to return holy communities to an austere life, abiding to strict religious guidelines set down by St Benedict in the sixth century. After the foundation of Britain’s first Cistercian abbey in 1128 (Waverley Abbey in Surrey) the waves of reform quickly spread, and other Cistercian communities such as Rievaulx were established across the country. By the middle of the 12th century Rievaulx was a large and thriving self-sufficient community. In 1167 the Abbey’s community numbered around 140 monks and around 500 lay brothers. A larger site was needed to accommodate this growing community, leading to the building of a new chapter house and a dramatic, imposing church. The Abbey site was designed to facilitate both religious and practical aspects of life. In addition to a great cloister where the monks could study and read, the Abbey also contained private quarters for more senior monks, as well as a parlour, dormitory and kitchen. Rievaulx also holds the earliest surviving infirmary complex on any British Cistercian site, built in the 1150s to care for sick and elderly members of the monastic community. Like many abbeys, Rievaulx was targeted by Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s. However, the Abbey’s religious population had dwindled over the centuries and by the time it was shut down and dismantled in 1538 only 23 monks remained there.

The ruins of Rievaulx Abbey, North Yorkshire. (English Heritage/Heritage Images/Getty Images) York MinsterFrom humble beginnings as a small wooden church, York Minster underwent several transformations during the medieval period before evolving into the spectacular Gothic cathedral that stands today. The first Christian church on the site was a modest wooden structure dating back to AD 627. By AD 640 King Oswald had replaced this with a small stone church. After surviving the Viking invasion in AD 866, York’s Anglo-Saxon church was ransacked by William the Conqueror’s forces in the Harrying of the North in 1069. After destroying the Anglo-Saxon church, William appointed his own Norman archbishop of York, who went about constructing a grand Norman Cathedral on the site. In the 13th century Walter De Gray (archbishop of York between 1215 and 1255) decided to rebuild the cathedral for the final time. He embarked on a mammoth project to redesign it in a dramatic Gothic style, with a monumental arching roof, intended to convey a sense of soaring upwards towards the sky. Constructed between 1220 and 1472, the magnificent Gothic-style minster took more than 250 years to complete. Its Great East Window, glazed by John Thornton of Coventry between 1405 and 1408, is now the largest expanse of medieval glass to have survived in Europe. York Minster has suffered many misfortunes over the centuries. In 1407 the central tower collapsed due to soft soil, and four fires [in 1753, 1829, 1840 and 1984] have wreaked significant damage. York Minster is now one of only seven cathedrals in the world to boast its own police force [a small, specialized cathedral constabulary who continue to operate independently of the rest of the city’s police force].

York Minster at night. (Rod Lawton/Digital Camera Magazine via Getty Images) The White TowerThe imposing White Tower at the heart of the Tower of London complex dates back to the late 11th century. Built by William the Conqueror to secure his hold on London, it was designed to awe and subdue the local population. The exact construction dates of the White Tower are unclear, but building was certainly underway in the 1070s and was completed by 1100. A key example of Norman architecture, the White Tower was the first building of its kind in England. William employed Norman masons and even had stone imported from Normandy for its construction. At 27.5m tall the Tower would have been visible for miles around. Intended as a fortress and stronghold rather than a royal palace, the White Tower’s design favoured defence over hospitality. Its fortifications were updated throughout the medieval period and during the reign of Richard the Lionheart they doubled in size. This proved to be a wise move, as in Richard’s absence his brother John besieged the White Tower in an attempt to seize the throne. The Tower’s defences held fast but the forces defending it [led by Richard’s Chancellor William Longchamp] were compelled to surrender owing to a lack of supplies. For those who fell from royal favour, the White Tower was a place of imprisonment and execution. From its foundation it was used as a prison – the first recorded prisoner held in the White Tower was Ranulf Flambard, bishop of Durham, in 1100. Under Edward III, the captured kings of Scotland and France were kept at the White Tower and it is believed that, centuries later, Guy Fawkes was tortured and interrogated in the White Tower’s basement. Even monarchs were not immune to imprisonment at the White Tower: in 1399 Richard II was imprisoned there after being forced to renounce his throne by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke.

The White Tower at the Tower of London. (Arcaid/UIG via Getty)

Westminster Hall, Houses of Parliament As the oldest building on the parliamentary estate, Westminster Hall has been central to the government of England since the 11th century. Built in 1097 by the Norman king William II (the son of William the Conqueror and known as Rufus), the Hall was a symbol of Norman majesty intended to impress the king’s new subjects. Rufus’s construction project was remarkably ambitious. Covering a floor space of 1,547 square metres (with walls two metres thick), Westminster Hall was by far the largest hall in England at the time. It was so large that when surveying the vast hall just after its construction, one of Rufus’s attendants reportedly remarked it was far bigger than it needed to be. However, Rufus himself was less than impressed – he replied it was not half large enough, a mere bedchamber compared to what he had in mind. Recent archaeological explorations at Westminster Hall have prompted some fascinating theories about the groundbreaking nature of its original construction. No evidence of columns used to support the vast roof has been uncovered, suggesting that it may have been self-supporting. This engineering would have been remarkably ahead of its time, as self-supporting roofs of this size were not seen elsewhere until the 13th and 14th centuries. Writing for History Extra, Paul Binski suggests that the “miracle” of Westminster Hall “is not just its survival, but its courage. The builders of these great structures had brilliant know-how, but also guts”.

A royal event at Westminster Hall in 2012. (Ben Stansall/WPA Pool/Getty)

Norwich Guildhall Situated in the centre of the medieval city, the Norwich Guildhall is a remarkable example of late medieval secular architecture. Built primarily between 1407 and 1412, its grandeur reflects the growing power and wealth of a new elite of merchants, traders and government agents during the period. By the 15th century Norwich had become one of the wealthiest and most important towns in England. Following a 1404 charter granting the city greater self–governing powers it was decided that a Guildhall should be built in order to administer the powers more effectively. The Guildhall fulfilled a role similar to that of a modern town hall, performing all the administrative functions the city required to govern the everyday lives of the city’s residents. The Guildhall served multiple purposes as a court, a tax collection hub and administrative centre. The Guildhall also contained an assembly chamber for council meetings, was equipped to hold prisoners and had a large ‘sword room’ used for storing weapons. Today the Guildhall is the largest surviving medieval building intended for a civic purpose outside of London.

Published on April 01, 2016 03:00

April Fools' Day - April 1st

InfoPlease

The uncertain origins of a foolish dayby David Johnson and Shmuel RossApril Fools' Day, sometimes called All Fools' Day, is one of the most light-hearted days of the year. Its origins are uncertain. Some see it as a celebration related to the turn of the seasons, while others believe it stems from the adoption of a new calendar.

Ancient cultures, including those of the Romans and Hindus, celebrated New Year's Day on or around April 1. It closely follows the vernal equinox (March 20th or March 21st.) In medieval times, much of Europe celebrated March 25, the Feast of Annunciation, as the beginning of the new year.

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII ordered a new calendar (the Gregorian Calendar) to replace the old Julian Calendar. The new calendar called for New Year's Day to be celebrated Jan. 1. That year, France adopted the reformed calendar and shifted New Year's day to Jan. 1. According to a popular explanation, many people either refused to accept the new date, or did not learn about it, and continued to celebrate New Year's Day on April 1. Other people began to make fun of these traditionalists, sending them on "fool's errands" or trying to trick them into believing something false. Eventually, the practice spread throughout Europe.

Problems With This ExplanationThere are at least two difficulties with this explanation. The first is that it doesn't fully account for the spread of April Fools' Day to other European countries. The Gregorian calendar was not adopted by England until 1752, for example, but April Fools' Day was already well established there by that point. The second is that we have no direct historical evidence for this explanation, only conjecture, and that conjecture appears to have been made more recently.

Constantine and KugelAnother explanation of the origins of April Fools' Day was provided by Joseph Boskin, a professor of history at Boston University. He explained that the practice began during the reign of Constantine, when a group of court jesters and fools told the Roman emperor that they could do a better job of running the empire. Constantine, amused, allowed a jester named Kugel to be king for one day. Kugel passed an edict calling for absurdity on that day, and the custom became an annual event.

"In a way," explained Prof. Boskin, "it was a very serious day. In those times fools were really wise men. It was the role of jesters to put things in perspective with humor."

This explanation was brought to the public's attention in an Associated Press article printed by many newspapers in 1983. There was only one catch: Boskin made the whole thing up. It took a couple of weeks for the AP to realize that they'd been victims of an April Fools' joke themselves.

Spring FeverIt is worth noting that many different cultures have had days of foolishness around the start of April, give or take a couple of weeks. The Romans had a festival named Hilaria on March 25, rejoicing in the resurrection of Attis. The Hindu calendar has Holi, and the Jewish calendar has Purim. Perhaps there's something about the time of year, with its turn from winter to spring, that lends itself to lighthearted celebrations.

Observances Around the WorldApril Fools' Day is observed throughout the Western world. Practices include sending someone on a "fool's errand," looking for things that don't exist; playing pranks; and trying to get people to believe ridiculous things.

The French call April 1 Poisson d'Avril, or "April Fish." French children sometimes tape a picture of a fish on the back of their schoolmates, crying "Poisson d'Avril" when the prank is discovered.

The uncertain origins of a foolish dayby David Johnson and Shmuel RossApril Fools' Day, sometimes called All Fools' Day, is one of the most light-hearted days of the year. Its origins are uncertain. Some see it as a celebration related to the turn of the seasons, while others believe it stems from the adoption of a new calendar.

Ancient cultures, including those of the Romans and Hindus, celebrated New Year's Day on or around April 1. It closely follows the vernal equinox (March 20th or March 21st.) In medieval times, much of Europe celebrated March 25, the Feast of Annunciation, as the beginning of the new year.

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII ordered a new calendar (the Gregorian Calendar) to replace the old Julian Calendar. The new calendar called for New Year's Day to be celebrated Jan. 1. That year, France adopted the reformed calendar and shifted New Year's day to Jan. 1. According to a popular explanation, many people either refused to accept the new date, or did not learn about it, and continued to celebrate New Year's Day on April 1. Other people began to make fun of these traditionalists, sending them on "fool's errands" or trying to trick them into believing something false. Eventually, the practice spread throughout Europe.

Problems With This ExplanationThere are at least two difficulties with this explanation. The first is that it doesn't fully account for the spread of April Fools' Day to other European countries. The Gregorian calendar was not adopted by England until 1752, for example, but April Fools' Day was already well established there by that point. The second is that we have no direct historical evidence for this explanation, only conjecture, and that conjecture appears to have been made more recently.

Constantine and KugelAnother explanation of the origins of April Fools' Day was provided by Joseph Boskin, a professor of history at Boston University. He explained that the practice began during the reign of Constantine, when a group of court jesters and fools told the Roman emperor that they could do a better job of running the empire. Constantine, amused, allowed a jester named Kugel to be king for one day. Kugel passed an edict calling for absurdity on that day, and the custom became an annual event.

"In a way," explained Prof. Boskin, "it was a very serious day. In those times fools were really wise men. It was the role of jesters to put things in perspective with humor."

This explanation was brought to the public's attention in an Associated Press article printed by many newspapers in 1983. There was only one catch: Boskin made the whole thing up. It took a couple of weeks for the AP to realize that they'd been victims of an April Fools' joke themselves.

Spring FeverIt is worth noting that many different cultures have had days of foolishness around the start of April, give or take a couple of weeks. The Romans had a festival named Hilaria on March 25, rejoicing in the resurrection of Attis. The Hindu calendar has Holi, and the Jewish calendar has Purim. Perhaps there's something about the time of year, with its turn from winter to spring, that lends itself to lighthearted celebrations.

Observances Around the WorldApril Fools' Day is observed throughout the Western world. Practices include sending someone on a "fool's errand," looking for things that don't exist; playing pranks; and trying to get people to believe ridiculous things.

The French call April 1 Poisson d'Avril, or "April Fish." French children sometimes tape a picture of a fish on the back of their schoolmates, crying "Poisson d'Avril" when the prank is discovered.

Published on April 01, 2016 02:00

March 31, 2016

How bloody was medieval life?

History Extra

A 14th-century French illustration of a brawl shows factors that could have contributed to violence: freely available alcohol and the fact that most people carried weapons. (AKG Images)

A 14th-century French illustration of a brawl shows factors that could have contributed to violence: freely available alcohol and the fact that most people carried weapons. (AKG Images)

In the 1300s in northern France, a nasty character named Jacquemon bribed a jailer to let his unwanted son-in-law die a painful death in prison. Jacquemon then, with the help of his son, killed his nephew, Colart Cordele. The impoverished Cordele had followed Jacquemon during the harvest, trying to glean the wheat from behind him, but angered his uncle by coming too close. Jacquemon grabbed his nephew by his hood, hurled him brutally to the ground and “spurred his horse to ride again and again” over the crumpled body.

It’s an episode that might have been lifted from Game of Thrones – no wonder the era has become a byword for brutality. Indeed, during a brutal scene in the film Pulp Fiction, one of the characters menaces that: “I’m gonna get medieval on your ass.” There’s no need to explain what this might involve because the stereotype of the violent, sadistic Middle Ages is well known to all of us.

But how accurate is this stereotype? As the Jacquemon episode shows, there is plenty that is shocking and disturbing in the surviving records for the later Middle Ages. But even more striking is that medieval contemporaries were also horrified by such events. Of course, we only know about this case because it provoked a legal reaction: it wasn’t seen as acceptable or even normal.

Measures of violence

Levels of interpersonal violence were certainly higher in the Middle Ages than today, but it’s very hard to quantify this precisely – even more so if we add war and the horrors of genocide into the equation. In part, this is because the changing nature of legal prosecutions means that we are not comparing like with like. Definitions of criminal violence have also changed; for example, rape and domestic violence were defined very narrowly in the Middle Ages.

The historian Laurence Stone calculated that homicide levels in medieval England were at least 10 times what they are today. Certainly, we cannot doubt that it was a dangerous time in which to live. An exceptional case, even by medieval standards, is provided by 14th‑century Oxford. Levels of violence there were considered unacceptably high by contemporaries: in the 1340s, the homicide rate was around 110 per 100,000. (In the UK in 2011, it was 1 per 100,000.)

Why were levels of interpersonal violence so high in the Middle Ages? Historians have offered various explanations. Steven Pinker has put forward a psychological theory, claiming that humankind learned only recently to tame its most savage impulses, but this doesn’t really account for the complexity of reactions to violence in the medieval period, as we shall see.

Others have pointed to the prevalence of alcohol, and the fact that many people were wandering round armed with daggers and other knives on a daily basis. There were no permanent police forces, as there are now, and in many cases the capture of a perpetrator depended on the co-operation of the community. Moreover, in an era of rudimentary medical care, many died from wounds that might today be successfully treated.

There are more complex explanations too. These were cultures in which honour was paramount and violence was recognised as a means of communicating certain messages. If you hacked off a woman’s nose, for example, most people would recognise this as a signifier of adultery. They were also profoundly unequal cultures, characterised – particularly from the 14th century – by high levels of social unrest. Sociologists and historians have been able to demonstrate a correlation between levels of inequality and levels of violence, which is particularly compelling for late medieval Europe.

Homicides varied from premeditated attacks to tavern brawls that ended in disaster. Often these were over-exuberant episodes gone horribly wrong. In 1304, for example, one Gerlach de Wetslaria, provost of a church in the diocese of Salzburg, applied for a pardon for killing a fellow student many years earlier when a playful sword fight had ended in tragedy.

Carrying out acts of violence seems to have been as much about proving oneself in front of one’s peers, and belonging to a group, as it was about the victim – which probably explains why men in gangs were responsible for much of the mayhem. This sense of fraternity characterises a group of men led by Robert Stafford. Stafford was a chaplain; perhaps because of his clerical status, he wittily named himself ‘Frere Tuk’ after the figure from the Robin Hood legends. His gang’s actions mostly took the form of poaching and offences against property, though there were more brutal undertones – apparently “they threatened the gamekeepers with death or mutilation”.

A 14th-century illustration for a section of the French poem 'Romance of the Rose' depicts a violent “crime of jealousy”. (AKG Images)

Female victims

It is much rarer to find women perpetrating violent crime; more often they were the victims. It is very difficult to assess levels of rape, because the offence was subject to changing definitions, most of which would appear far too narrow to our modern eyes. Women had to be able to physically demonstrate their lack of consent, and risked their reputations and punishment themselves in doing so. The odds were loaded against them.

Cases that were eventually reported tended to be particularly brutal. In 1438, one Thomas Elam attacked Margaret Perman. He broke into her house, attempted to rape her and “feloniously bit Margaret with his teeth so that he ripped off the nose of the said Margaret with that bite, and broke three of her ribs there”. The case came to court because she died from her wounds. Elam was condemned to be hanged.

Definitions of domestic violence were also radically different in the later Middle Ages. Most acts of aggression that we would deem to be criminal were then thought of simply as acceptable discipline. If a wife disobeyed her husband, it was thought right and proper that she should be punished. Domestic violence does, though, sometimes appear in the records of ecclesiastical courts when a wife sued for divorce, or in criminal records when the violence resulted in permanent maiming, miscarriage, or death.

How to distinguish between levels of ‘acceptable’ domestic discipline and unacceptable domestic violence was an ongoing problem. One famous solution often cited was the ‘rule of thumb’, whereby – it’s claimed – it was acceptable to beat your wife, as long as the stick you used was thinner than your thumb. However, in reality, discussions were more sophisticated and less conclusive than this.

In 1326 in Paris, one Colin le Barbier hit his wife with a billiard stick so hard that she died. He was tried in a criminal court and found guilty of murder. However, he appealed and claimed that his wife deserved her suffering because she had nagged him so relentlessly in public. He said that he had not meant to kill her: “He meant only to scare her, so that she would be quiet; however, the stick accidentally entered into her thigh a little above the knee.” The reason she had died, he added, was “because she failed to tend [the wound] properly” rather than because he had mistreated her. His subsequent acquittal tells us a lot about attitudes in this period.

Homicide, rape and domestic violence could be found across the social spectrum. However, some kinds of violence were more common in certain milieux. Violent theft was most often perpetrated by people on the economic margins of society, who stole out of desperation. It peaked during periods of particular deprivation, such as the horrific famine of the 1310s in which as much as 25 per cent of the population died.

England in the 14th and 15th centuries was also notorious for the prevalence of frightening gangs, often comprising gentry or even noblemen. These marauded around the countryside, plundering and leaving a trail of blood in their wake. In 1332, for example, the Folville gang was accused of kidnapping a royal official; they had already killed a baron of the exchequer. These were young men who quite literally thought themselves to be beyond the law, often involved in feuds and vendettas, and for whom honour was a key concept.

A French miniature from c1470 depicts knights in combat at a tournament. Knightly chivalry underpinned some of the era’s bloodiest episodes. (AKG Images)

A question of honour

Honour-driven violence was also prevalent at the top of the social tree. During periods of weak kingship, violence by noblemen could reach terrifying levels. In early 15th-century France, with a king (Charles VI, ‘the Mad’) intermittently suffering from paranoid schizophrenia and believing himself to be made of glass, powerful warring nobles were able to seize control. The result was spiralling violence that culminated in the 1407 assassination of the Duke of Orléans and, ultimately, the English entry into France.

Things were not much rosier for the English. In the second half of the 15th century, the weakness of the reigning monarch, Henry VI, and the accumulation of huge retinues by hostile aristocrats were, at least in large part, responsible for the Wars of the Roses. The lines between interpersonal violence, civil war and full-blown war were indistinct.

At the other end of the social spectrum, in the later Middle Ages the growing structural inequalities created by rapid commercialisation and urbanisation, as well as competing forms of government, generated a series of riots and revolts. Plotted on a map, these are concentrated along the main trading belt of Europe, from London to Paris and the Netherlands through the markets of Champagne to the commercial heartlands of northern Italy. The most famous examples – the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 in England, the Ciompi revolt of 1378 in Florence, and the Paris rebellion and Jacquerie revolt in northern France in 1358 – all involved complex alliances of rebels from various social groups demanding greater representation, railing against corruption, and protesting their economic marginalisation.

Revolts along social lines sometimes overlapped with violence driven by religion. Famously, medieval Europe was marked by waves of popular religious persecution, with anti-Semitism rearing its ugly head with depressing frequency.

Yet perhaps the most violent dimension of medieval life was that of the law, which carried out its own gruesome rituals. Punishment was intended to be spectacular. Most serious crimes were punishable by hanging, but plenty more imaginative ways of disposing of criminals were employed.

In many areas of Europe, those found guilty of forging money were boiled alive. This obsession with providing a spectacle of violence – to emphasise the guilt of the accused, and to deter and awe observers – led to some almost farcical episodes. An old man questioned in the 1290s remembered how, when he was young, he saw a man hanged for murder. The body was cut down from the gibbet by a competing jurisdiction and rehanged – only for the original jurisdiction to construct a straw effigy that they hanged.

St Eligius pinches the devil’s nose in a 1337 French illustration from a story of the First Crusade. Religious fervour sparked widespread violence. (Bridgeman Images)

Reactions to violence

We’re left, then, with a picture of an extraordinarily violent society. Though it’s very difficult to arrive at precise numbers, it’s clear that this is not a society one would wish to visit for any length of time.

There is, though, a flip side to all of this. The evidence suggests that, though violence was common, people were not simply inured to it. On the contrary – they really cared about it. This is not to say that violence was simply deemed to be wrong: rather, it was a problem about which people worried and talked.

The ethos of chivalry represents one way in which attempts were made to channel violence. Chivalric custom suggested that one should fight only with certain kinds of weapons; that one should seek only worthy opponents; and that one should exercise mercy and generosity. The reality was that chivalry underpinned some of the most brutal and bloodiest episodes in our history (notably the Hundred Years’ War), but the point remains that this was a set of customs arising out of concern and a sense that violence can be a problem.

The most important clue that people worried about violence is the fact that they wrote about it. Medieval literature is full of descriptions of torture, but close readings of these texts show that torturers were demonised. Such a strategy would work only if people felt torture to be profoundly problematic – and they certainly did think it a problem. In 14th-century France, criminal courts usually subjected the evidence gained from torture to extra scrutiny because it was deemed unreliable.

Chronicle sources, the official histories written in the Middle Ages, tend to provide wildly exaggerated tallies of levels of violence, particularly in revolts. Again, though, the desired literary and political effect only worked because people found such violence disturbing. The majority of our evidence is in the form of legal documents. Burgeoning legal systems in this period only bothered to produce such documentation because high levels of violence were deemed unacceptable.

In literary depictions of violence, such as the entertaining stories of Renard the Fox, popular throughout Europe, violence and cruelty were omnipresent precisely because they were shocking. The horrific story of the fox raping the wife of his friend, the wolf, then urinating on her children, often provoked troubled laughter from its medieval audience.

In the poetry of the time we can also find comments about the disturbing nature of violence. In Dante’s 14th-century vision of Inferno, hell is characterised by endless cycles of violence. And in the French poet François Villon’s Le Ballade des Pendus, the decaying bodies swinging on the gibbet speak directly:

Human brothers who come after us,

Don’t harden your hearts against us...

The rain has washed away our filth,

The sun has dried and blackened us.

Magpie and crows have scratched out our eyes

And torn our beards and eyebrows.

We are never still, but sway to and fro in the wind.

Birds peck at us more than needles on a thimble...

Brothers, there’s nothing funny about this.

May God absolve us all.

It’s an arresting image – a very visual representation of the prevalence of violence in the Middle Ages, but one that also shows it was, even then, profoundly upsetting.

Outbreaks of carnage

Medieval violence was sparked by everything from social unrest and military aggression to family feuds and rowdy students...

Ciompi revolt, 1378

This revolt in Florence stands out because it was momentarily successful, leading to a radical regime change. The revolt unfolded in three stages: reform, followed by violent revolution, then by a vicious backlash. Florence was a highly developed town with a proto-industrial wool industry, but many disenfranchised workers. The revolt was driven by the desire for greater representation, fiscal discontent and ever-shifting alliances of political factions.

Chevauchées of the Black Prince, 1355–56

The Black Prince was the eldest son of Edward III. During the Hundred Years’ War, he achieved military success at Poitiers. He also led a series of chevauchées in France, armed raids involving pillaging, raping and devastation on a horrifying scale. The aim was to destroy enemy resources and morale, and to provoke battle. Tellingly, the Black Prince is still known as a great chivalric hero.

Peasants’ Revolt, 1381

In the aftermath of the Black Death, taxes were levied to fund the Hundred Years’ War – and in 1381 the peasants rose up to protest the latest poll tax. Violence ranged from burning legal documents to liberating prisoners and lynching figures of authority, notably the lord chancellor. The rebels, led by Wat Tyler, were inspired by the sermons of John Ball, who preached a message of freedom from servitude. The peasants presented their demands to Richard II but Tyler was killed and they were defeated.

Wat Tyler and John Ball, leaders of the Peasants’ Revolt, are shown meeting in a 15th-century miniature. (Getty)

St Scholastica’s Day riots, 1355

On 10 February 1355 two students took umbrage at being served watered-down wine in the Swindlestock Tavern in Oxford, throwing the wine in the tavern-keeper’s face and brutally beating him. The violence swiftly spread: some 200 more students joined the original pair, burning and robbing houses. Retribution was not slow to follow, as people from the surrounding countryside joined the townsfolk in attacking the students with bows and arrows. Two days of rioting left 63 students dead.

A servant pours wine in a 15th-century Italian illustration. Alcohol fuelled riots in Oxford. (Bridgeman)

Murder of Nicholas Radford, 1455

Nicholas Radford was a justice of the peace under Henry VI, during the period of factionalism that later escalated into the Wars of the Roses. His godson’s brother, Thomas Courtenay, came to his gates one night and brutally murdered him; Henry Courtenay, the victim’s godson, later subjected the corpse to a grotesque coroner’s inquest. This was the culmination of a private vendetta, but also a deliberate affront to royal justice.

Dr Hannah Skoda is a specialist in medieval history based at the University of Oxford.

A 14th-century French illustration of a brawl shows factors that could have contributed to violence: freely available alcohol and the fact that most people carried weapons. (AKG Images)

A 14th-century French illustration of a brawl shows factors that could have contributed to violence: freely available alcohol and the fact that most people carried weapons. (AKG Images) In the 1300s in northern France, a nasty character named Jacquemon bribed a jailer to let his unwanted son-in-law die a painful death in prison. Jacquemon then, with the help of his son, killed his nephew, Colart Cordele. The impoverished Cordele had followed Jacquemon during the harvest, trying to glean the wheat from behind him, but angered his uncle by coming too close. Jacquemon grabbed his nephew by his hood, hurled him brutally to the ground and “spurred his horse to ride again and again” over the crumpled body.

It’s an episode that might have been lifted from Game of Thrones – no wonder the era has become a byword for brutality. Indeed, during a brutal scene in the film Pulp Fiction, one of the characters menaces that: “I’m gonna get medieval on your ass.” There’s no need to explain what this might involve because the stereotype of the violent, sadistic Middle Ages is well known to all of us.