MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 97

June 1, 2016

Cnut's invasion of England: setting the scene for the Norman conquest

History Extra

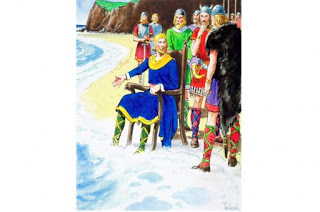

King Cnut (Canute) failing to hold back the waves, early 11th century (c1900). Artist: Trelleek. © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy

King Cnut (Canute) failing to hold back the waves, early 11th century (c1900). Artist: Trelleek. © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy

In the summer of 1013, the Danish king Svein, accompanied by his son Cnut, launched an invasion of England – the first of the two successful conquests England would witness in the 11th century, but by far the less well known.

Scandinavian armies had been raiding in England on and off for more than 30 years, extracting huge sums of money from the country and putting King Æthelred under ever-increasing pressure, but Svein’s arrival in 1013 seems to have been something different – a carefully-planned, full-scale invasion. After years of raiding England, Svein knew enough about the English political situation to exploit its weaknesses: Æthelred's court was fractured by internal rivalries, a poisonous atmosphere attributed to the influence of his untrustworthy advisor Eadric, and Svein was able to make a strategic alliance with some of those who had fallen from the king's favour.

The invasion progressed with devastating speed: within a few weeks all the country north of Watling Street – the ancient dividing-line between the north and south of England – had submitted to the Danish king. Next the south was subdued by violence, and before the end of the year Æthelred and his family had been forced to flee to Normandy.

Svein, now king of England and Denmark, ruled from Christmas to Candlemas, but died suddenly on 3 February 1014. The Danish fleet chose Cnut to succeed him, but the English nobles had other ideas: they contacted Æthelred, still in refuge in Normandy, and invited him to come back as king. They said, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us, “that no lord could be dearer to them than their natural lord, if he would govern more justly than he had done before”. In response, Æthelred promised to be a better king, to forgive those who had deserted him, and to “remedy all the things of which they disapproved”. On these terms the agreement was made, and Æthelred returned to England. This time he managed to drive out Cnut, and the fleet went back to Denmark.

But a year later the young Danish king was back, hoping to repeat his father’s conquest. Despite his promises, Æthelred did not forgive those who had sided with the Danes: he viciously punished the northern leaders who had made an alliance with Svein, and in doing so caused his son, Edmund Ironside, to rebel against him. When Cnut returned in 1015, Æthelred was ill and England was divided: large parts of the country submitted to the Danes, while Edmund struggled to put an army together.

Only after Æthelred died in April 1016 did southern England finally unite behind Edmund, and six months of war followed, with the two armies fighting battles all over the south. The last was fought at a place called Assandun in Essex on 18 October 1016 – by strange coincidence, 50 years almost to the day before the battle of Hastings – and there the Danes were victorious. Edmund died six weeks later (likely by wounds received in battle or by disease, but some sources say he was murdered), and Cnut was finally sole king of England.

The immediate aftermath of Cnut's conquest was violent, although not much more so than the last years of Æthelred's reign. Potential opponents were summarily killed, and the remaining members of the royal family were driven into exile. Cnut married Æthelred's widow, Emma, sister of the duke of Normandy, and between them they founded a new dynasty – part Danish, part Norman, but presenting itself as English. There had been Danish kings ruling in England before, some of them famous Vikings whose names were still something to conjure with in the 11th century: Cnut's poets, extolling his conquest in Old Norse verse, compared him to the fearsome Ivar the Boneless and the sons of Ragnar Lothbrok, and in one sense, Cnut was heir to the conquests of these larger-than-life Danish kings.

But at the same time Cnut presented himself as a conciliatory conqueror, eager to learn from the land he had captured: by gifts to churches and monasteries he made amends for the damage his father and previous Danish kings had done, and he ruled in English and through English laws – even as his poets praised him for driving Æthelred's family out of England. When he made a diplomatic visit to Rome in 1027, he was welcomed as the Christian ruler of a new North Sea empire. Almost the only thing many people know about Cnut is that he made a grand display of his inability to control the tide, and this story – first recorded in the 12th century – is not quite as silly as it is sometimes assumed to be: power over the sea was the very basis of Cnut's authority, and a story in which Cnut yields that sea-power to God might have helped to explain the remarkable transformation of a Viking king into a Christian monarch.

When Cnut died in 1035, after ruling for nearly 20 years, he was buried in Winchester, the traditional seat of power of the kings of Wessex. His empire did not long survive him. After the early death of Harthacnut, Cnut’s son by Emma, Æthelred's son Edward regained the English throne – “as was his natural right”, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says. During his reign Edward had to deal with those, like Earl Godwine and his sons, who had risen to power under Cnut, but before long the impact of the Danish Conquest was to be overshadowed by the second, more famous conquest of the 11th century.

Compared to the Norman victory in 1066 – perhaps the single most famous date in medieval English history – the Danish Conquest has always seemed less important, with few enduring consequences. But the story of Svein’s well-planned invasion and Cnut’s successful reign tells us some interesting things about regional divisions within England, and England’s relationship with Scandinavia and the rest of Europe in the 11th century: in many ways – not least by destabilising the English monarchy and driving Edward into exile in Normandy – the Danish Conquest set the stage for much of what happened in 1066.

Dr Eleanor Parker is Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Anglo-Norman England at the University of Oxford. She blogs about medieval England at www.aclerkofoxford.blogspot.co.uk. You can follow her on Twitter @ClerkofOxford

King Cnut (Canute) failing to hold back the waves, early 11th century (c1900). Artist: Trelleek. © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy

King Cnut (Canute) failing to hold back the waves, early 11th century (c1900). Artist: Trelleek. © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy In the summer of 1013, the Danish king Svein, accompanied by his son Cnut, launched an invasion of England – the first of the two successful conquests England would witness in the 11th century, but by far the less well known.

Scandinavian armies had been raiding in England on and off for more than 30 years, extracting huge sums of money from the country and putting King Æthelred under ever-increasing pressure, but Svein’s arrival in 1013 seems to have been something different – a carefully-planned, full-scale invasion. After years of raiding England, Svein knew enough about the English political situation to exploit its weaknesses: Æthelred's court was fractured by internal rivalries, a poisonous atmosphere attributed to the influence of his untrustworthy advisor Eadric, and Svein was able to make a strategic alliance with some of those who had fallen from the king's favour.

The invasion progressed with devastating speed: within a few weeks all the country north of Watling Street – the ancient dividing-line between the north and south of England – had submitted to the Danish king. Next the south was subdued by violence, and before the end of the year Æthelred and his family had been forced to flee to Normandy.

Svein, now king of England and Denmark, ruled from Christmas to Candlemas, but died suddenly on 3 February 1014. The Danish fleet chose Cnut to succeed him, but the English nobles had other ideas: they contacted Æthelred, still in refuge in Normandy, and invited him to come back as king. They said, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us, “that no lord could be dearer to them than their natural lord, if he would govern more justly than he had done before”. In response, Æthelred promised to be a better king, to forgive those who had deserted him, and to “remedy all the things of which they disapproved”. On these terms the agreement was made, and Æthelred returned to England. This time he managed to drive out Cnut, and the fleet went back to Denmark.

But a year later the young Danish king was back, hoping to repeat his father’s conquest. Despite his promises, Æthelred did not forgive those who had sided with the Danes: he viciously punished the northern leaders who had made an alliance with Svein, and in doing so caused his son, Edmund Ironside, to rebel against him. When Cnut returned in 1015, Æthelred was ill and England was divided: large parts of the country submitted to the Danes, while Edmund struggled to put an army together.

Only after Æthelred died in April 1016 did southern England finally unite behind Edmund, and six months of war followed, with the two armies fighting battles all over the south. The last was fought at a place called Assandun in Essex on 18 October 1016 – by strange coincidence, 50 years almost to the day before the battle of Hastings – and there the Danes were victorious. Edmund died six weeks later (likely by wounds received in battle or by disease, but some sources say he was murdered), and Cnut was finally sole king of England.

The immediate aftermath of Cnut's conquest was violent, although not much more so than the last years of Æthelred's reign. Potential opponents were summarily killed, and the remaining members of the royal family were driven into exile. Cnut married Æthelred's widow, Emma, sister of the duke of Normandy, and between them they founded a new dynasty – part Danish, part Norman, but presenting itself as English. There had been Danish kings ruling in England before, some of them famous Vikings whose names were still something to conjure with in the 11th century: Cnut's poets, extolling his conquest in Old Norse verse, compared him to the fearsome Ivar the Boneless and the sons of Ragnar Lothbrok, and in one sense, Cnut was heir to the conquests of these larger-than-life Danish kings.

But at the same time Cnut presented himself as a conciliatory conqueror, eager to learn from the land he had captured: by gifts to churches and monasteries he made amends for the damage his father and previous Danish kings had done, and he ruled in English and through English laws – even as his poets praised him for driving Æthelred's family out of England. When he made a diplomatic visit to Rome in 1027, he was welcomed as the Christian ruler of a new North Sea empire. Almost the only thing many people know about Cnut is that he made a grand display of his inability to control the tide, and this story – first recorded in the 12th century – is not quite as silly as it is sometimes assumed to be: power over the sea was the very basis of Cnut's authority, and a story in which Cnut yields that sea-power to God might have helped to explain the remarkable transformation of a Viking king into a Christian monarch.

When Cnut died in 1035, after ruling for nearly 20 years, he was buried in Winchester, the traditional seat of power of the kings of Wessex. His empire did not long survive him. After the early death of Harthacnut, Cnut’s son by Emma, Æthelred's son Edward regained the English throne – “as was his natural right”, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says. During his reign Edward had to deal with those, like Earl Godwine and his sons, who had risen to power under Cnut, but before long the impact of the Danish Conquest was to be overshadowed by the second, more famous conquest of the 11th century.

Compared to the Norman victory in 1066 – perhaps the single most famous date in medieval English history – the Danish Conquest has always seemed less important, with few enduring consequences. But the story of Svein’s well-planned invasion and Cnut’s successful reign tells us some interesting things about regional divisions within England, and England’s relationship with Scandinavia and the rest of Europe in the 11th century: in many ways – not least by destabilising the English monarchy and driving Edward into exile in Normandy – the Danish Conquest set the stage for much of what happened in 1066.

Dr Eleanor Parker is Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Anglo-Norman England at the University of Oxford. She blogs about medieval England at www.aclerkofoxford.blogspot.co.uk. You can follow her on Twitter @ClerkofOxford

Published on June 01, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - first known batch of Scotch Whisky recorded

June 1

1495 Friar John Cor (Lindores Abbey, Scotland) recorded the first known batch of Scotch Whisky.

1495 Friar John Cor (Lindores Abbey, Scotland) recorded the first known batch of Scotch Whisky.

Published on June 01, 2016 02:00

May 31, 2016

Viking women: raiders, traders and settlers

History Extra

A detail of the decorative carving on the side of the Oseberg cart depicting a woman with streaming hair apparently restraining a man's sword-arm as he strikes at a horseman accompanied by a dog. Below is a frieze of intertwined serpentine beasts. c850 AD. Viking Ship Museum, Bygdoy. (Werner Forman Archive/Bridgeman Images)

In the long history of Scandinavia, the period that saw the greatest transformation was the Viking Age (AD 750–1100). This great movement of peoples from Denmark, Norway and Sweden, heading both east and west, and the social, religious, political and cultural changes that resulted from it, affected the lives and roles of women as well as the male warriors and traders whom we more usually associate with ‘Viking’ activities.

Scandinavian society was hierarchical, with slaves at the bottom, a large class of the free in the middle, and a top level of wealthy local and regional leaders, some of whom eventually sowed the seeds of the medieval Scandinavian monarchies. The slaves and the free lived a predominantly rural and agricultural life, while the upper levels of the hierarchy derived their wealth from the control and export of natural resources. The desire to increase such wealth was a major motivating factor of the Viking Age expansion.

One way to acquire wealth was to raid the richer countries to the south and west. The Scandinavians burst on the scene in the eighth century as feared warriors attacking parts of the British Isles and the European continent. Such raiding parties were mainly composed of men, but there is contemporary evidence from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that some warbands were accompanied by women and, inevitably, children, particularly if they had been away from Scandinavia for some time. The sources do not reveal whether these women had come from Scandinavia with the men or joined them along the way, but both are likely.

Despite popular misconceptions, however, there is no convincing evidence that women participated directly in fighting and raiding – indeed, the Chronicle describes women and children being put in a place of safety. The Viking mind, a product of a militarised culture, could certainly imagine women warriors, as evidenced by their art and mythology, but this was not an option for real women.

SettlementIn parts of Britain and Ireland and on the north-western coasts of the European continent, these raids were succeeded by settlement, as recorded in contemporary documents and shown by language, place-names and archaeology. An interesting question is whether these warriors-turned-settlers established families with Scandinavian wives or whether they integrated more quickly by taking local partners. There is strong evidence in many parts of Britain for whole communities speaking Scandinavian as the everyday language of the home, implying the presence of Scandinavian-speaking women.

Metal-detectorist finds show that Scandinavian-style jewellery was imported into England in considerable numbers on the clothing of the female settlers themselves. In the north and west of Scotland, Scandinavian speech and culture persisted well into the Middle Ages, and genetic evidence suggests that Scandinavian families and communities emigrated to places such as Orkney and Shetland en masse.

Not all of these settlers stayed in the British Isles, however. From both the Norwegian homeland and the British Isles, ambitious emigrants relocated to the previously uninhabited Faroe Islands and Iceland and, somewhat later, to Greenland and even North America. The Icelandic Book of Settlements, written in the 13th century, catalogues more than 400 Viking-Age settlers of Iceland. Thirteen of these were women, remembered as leading their households to a new life in a new land. One of them was Aud (also known as Unn), the deep-minded who, having lost her father, husband and son in the British Isles, took it on herself to have a ship built and move the rest of her household to Iceland, where the Book of the Icelanders lists her as one of the four most prominent Norwegian founders of Iceland. As a widow, Aud had complete control of the resources of her household and was wealthy enough to give both land and freedom to her slaves once they arrived in Iceland.

SlaveryOther women were, however, taken to Iceland as slaves. Studies of the genetic make-up of the modern Icelandic population have been taken to suggest that up to two-thirds of its female founding population had their origins in the British Isles, while only one third came from Norway (the situation is, however, the reverse for the male founding population).

The Norwegian women were the wives of leading Norwegian chieftains who established large estates in Iceland, while the British women may have been taken there as slaves to work on these estates. But the situation was complex and it is likely that some of the British women were wives legally married to Scandinavian men who had spent a generation or two in Scotland or Ireland before moving on to Iceland. The written sources also show that some of the British slaves taken to Iceland were male, as in the case of Aud, discussed above.

These pioneer women, both chieftains’ wives and slaves, endured the hardships of travel across the North Atlantic in an open boat along with their children and all their worldly goods, including their cows, sheep, horses and other animals. Women of all classes were essential to the setting up of new households in unknown and uninhabited territories, not only in Iceland but also in Greenland, where the Norse settlement lasted for around 500 years.

Both the Icelandic sagas and archaeology show that women participated in the voyages from Greenland to some parts of North America (known to them as Vinland). An Icelandic woman named Gudrid Thorbjarnardottir is particularly remembered for having been to Vinland (where she gave birth to a son), but also for having in later life gone on pilgrimage to Rome and become a nun.

A page from the 'Anglo-Saxon Chronicle' in Anglo-Saxon or Old English, telling of King Aethelred I of Wessex and his brother, the future King Alfred the Great, and their battles with the Viking invaders at Reading and Ashdown in AD 871 (c1950). (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Mistress of the houseThese new settlements in the west were, like those of the homelands, rural and agricultural, and the roles of women were the traditional ones of running the household. Although free women did not by convention participate in public life, it is clear that the mistress of the household had absolute authority in the most important matters of daily life within its four walls, and also in many aspects of farm work.

Runic inscriptions show that women were highly valued for this. On a commemorative stone from Hassmyra, in Sweden, the deceased Odindisa is praised in runic verse by her husband for her role as mistress of that farm. The rune stones of the Isle of Man include a particularly high proportion commemorating women.

Those women who remained in Scandinavia also felt the effects of the Viking Age. The evidence of burials shows that women, at least those of the wealthier classes, were valued and respected. Much precious metalwork from the British Isles found its way into the graves of Norwegian women, usually presumed to be gifts from men who went west, but some were surely acquired abroad by the women themselves.

At the top level of society, women’s graves were as rich as those of men – the grave goods of a wealthy woman buried with her servant at Oseberg in Norway included a large and beautiful ship, several horses and many other valuable objects. Such a woman clearly had power and influence to be remembered in this way. With the establishment of the monarchies of Denmark, Norway and Sweden towards the end of the Viking Age, it is clear that queens could have significant influence, such as Astrid, the widow of St Olaf, who ensured the succession of her stepson Magnus to the Norwegian throne in the year 1035.

Urbanisation and ChristianityAnother of the major changes affecting Viking Age Scandinavia was that of urbanisation. While trade had long been an important aspect of Scandinavian wealth creation, the development of emporia – town-like centres – such as Hedeby in Denmark, Kaupang in Norway, Birka in Sweden, or trading centres at York and Dublin, provided a new way of life for many.

The town-like centres plugged into wide-ranging international networks stretching both east and west. Towns brought many new opportunities for women as well as men in both craft and trade. The fairly standard layouts of the buildings in these towns show that the wealth-creating activities practised there were family affairs, involving the whole household, just as farming was in rural areas. In Russia, finds of scales and balances in Scandinavian female graves indicate that women took part in trading activities there.

Along with urbanisation, another major change was the adoption of Christianity. The rune stones of Scandinavia date largely from the period of Christianisation and show that women adopted the new religion with enthusiasm. As family memorials, the inscriptions are still dominated by men, but with Christianity, more and more of them were dedicated to women. Those associated with women were also more likely to be overtly Christian, such as a stone in memory of a certain Ingirun who went from central Sweden on pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

The Viking Age, then, was not just a masculine affair. Women played a full part in the voyages of raiding, trading and settlement, and the new settlements in the North Atlantic would not have survived very long had it not been for their contribution. This mobile and expansive age provided women with new opportunities, and sagas, rune stones and archaeology show that many of them were honoured and remembered accordingly.

Judith Jesch is professor of Viking studies at the University of Nottingham. Her publications include The Viking Diaspora (Routledge, 2015). You can follow her on Twitter @JudithJesch

A detail of the decorative carving on the side of the Oseberg cart depicting a woman with streaming hair apparently restraining a man's sword-arm as he strikes at a horseman accompanied by a dog. Below is a frieze of intertwined serpentine beasts. c850 AD. Viking Ship Museum, Bygdoy. (Werner Forman Archive/Bridgeman Images)

In the long history of Scandinavia, the period that saw the greatest transformation was the Viking Age (AD 750–1100). This great movement of peoples from Denmark, Norway and Sweden, heading both east and west, and the social, religious, political and cultural changes that resulted from it, affected the lives and roles of women as well as the male warriors and traders whom we more usually associate with ‘Viking’ activities.

Scandinavian society was hierarchical, with slaves at the bottom, a large class of the free in the middle, and a top level of wealthy local and regional leaders, some of whom eventually sowed the seeds of the medieval Scandinavian monarchies. The slaves and the free lived a predominantly rural and agricultural life, while the upper levels of the hierarchy derived their wealth from the control and export of natural resources. The desire to increase such wealth was a major motivating factor of the Viking Age expansion.

One way to acquire wealth was to raid the richer countries to the south and west. The Scandinavians burst on the scene in the eighth century as feared warriors attacking parts of the British Isles and the European continent. Such raiding parties were mainly composed of men, but there is contemporary evidence from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that some warbands were accompanied by women and, inevitably, children, particularly if they had been away from Scandinavia for some time. The sources do not reveal whether these women had come from Scandinavia with the men or joined them along the way, but both are likely.

Despite popular misconceptions, however, there is no convincing evidence that women participated directly in fighting and raiding – indeed, the Chronicle describes women and children being put in a place of safety. The Viking mind, a product of a militarised culture, could certainly imagine women warriors, as evidenced by their art and mythology, but this was not an option for real women.

SettlementIn parts of Britain and Ireland and on the north-western coasts of the European continent, these raids were succeeded by settlement, as recorded in contemporary documents and shown by language, place-names and archaeology. An interesting question is whether these warriors-turned-settlers established families with Scandinavian wives or whether they integrated more quickly by taking local partners. There is strong evidence in many parts of Britain for whole communities speaking Scandinavian as the everyday language of the home, implying the presence of Scandinavian-speaking women.

Metal-detectorist finds show that Scandinavian-style jewellery was imported into England in considerable numbers on the clothing of the female settlers themselves. In the north and west of Scotland, Scandinavian speech and culture persisted well into the Middle Ages, and genetic evidence suggests that Scandinavian families and communities emigrated to places such as Orkney and Shetland en masse.

Not all of these settlers stayed in the British Isles, however. From both the Norwegian homeland and the British Isles, ambitious emigrants relocated to the previously uninhabited Faroe Islands and Iceland and, somewhat later, to Greenland and even North America. The Icelandic Book of Settlements, written in the 13th century, catalogues more than 400 Viking-Age settlers of Iceland. Thirteen of these were women, remembered as leading their households to a new life in a new land. One of them was Aud (also known as Unn), the deep-minded who, having lost her father, husband and son in the British Isles, took it on herself to have a ship built and move the rest of her household to Iceland, where the Book of the Icelanders lists her as one of the four most prominent Norwegian founders of Iceland. As a widow, Aud had complete control of the resources of her household and was wealthy enough to give both land and freedom to her slaves once they arrived in Iceland.

SlaveryOther women were, however, taken to Iceland as slaves. Studies of the genetic make-up of the modern Icelandic population have been taken to suggest that up to two-thirds of its female founding population had their origins in the British Isles, while only one third came from Norway (the situation is, however, the reverse for the male founding population).

The Norwegian women were the wives of leading Norwegian chieftains who established large estates in Iceland, while the British women may have been taken there as slaves to work on these estates. But the situation was complex and it is likely that some of the British women were wives legally married to Scandinavian men who had spent a generation or two in Scotland or Ireland before moving on to Iceland. The written sources also show that some of the British slaves taken to Iceland were male, as in the case of Aud, discussed above.

These pioneer women, both chieftains’ wives and slaves, endured the hardships of travel across the North Atlantic in an open boat along with their children and all their worldly goods, including their cows, sheep, horses and other animals. Women of all classes were essential to the setting up of new households in unknown and uninhabited territories, not only in Iceland but also in Greenland, where the Norse settlement lasted for around 500 years.

Both the Icelandic sagas and archaeology show that women participated in the voyages from Greenland to some parts of North America (known to them as Vinland). An Icelandic woman named Gudrid Thorbjarnardottir is particularly remembered for having been to Vinland (where she gave birth to a son), but also for having in later life gone on pilgrimage to Rome and become a nun.

A page from the 'Anglo-Saxon Chronicle' in Anglo-Saxon or Old English, telling of King Aethelred I of Wessex and his brother, the future King Alfred the Great, and their battles with the Viking invaders at Reading and Ashdown in AD 871 (c1950). (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Mistress of the houseThese new settlements in the west were, like those of the homelands, rural and agricultural, and the roles of women were the traditional ones of running the household. Although free women did not by convention participate in public life, it is clear that the mistress of the household had absolute authority in the most important matters of daily life within its four walls, and also in many aspects of farm work.

Runic inscriptions show that women were highly valued for this. On a commemorative stone from Hassmyra, in Sweden, the deceased Odindisa is praised in runic verse by her husband for her role as mistress of that farm. The rune stones of the Isle of Man include a particularly high proportion commemorating women.

Those women who remained in Scandinavia also felt the effects of the Viking Age. The evidence of burials shows that women, at least those of the wealthier classes, were valued and respected. Much precious metalwork from the British Isles found its way into the graves of Norwegian women, usually presumed to be gifts from men who went west, but some were surely acquired abroad by the women themselves.

At the top level of society, women’s graves were as rich as those of men – the grave goods of a wealthy woman buried with her servant at Oseberg in Norway included a large and beautiful ship, several horses and many other valuable objects. Such a woman clearly had power and influence to be remembered in this way. With the establishment of the monarchies of Denmark, Norway and Sweden towards the end of the Viking Age, it is clear that queens could have significant influence, such as Astrid, the widow of St Olaf, who ensured the succession of her stepson Magnus to the Norwegian throne in the year 1035.

Urbanisation and ChristianityAnother of the major changes affecting Viking Age Scandinavia was that of urbanisation. While trade had long been an important aspect of Scandinavian wealth creation, the development of emporia – town-like centres – such as Hedeby in Denmark, Kaupang in Norway, Birka in Sweden, or trading centres at York and Dublin, provided a new way of life for many.

The town-like centres plugged into wide-ranging international networks stretching both east and west. Towns brought many new opportunities for women as well as men in both craft and trade. The fairly standard layouts of the buildings in these towns show that the wealth-creating activities practised there were family affairs, involving the whole household, just as farming was in rural areas. In Russia, finds of scales and balances in Scandinavian female graves indicate that women took part in trading activities there.

Along with urbanisation, another major change was the adoption of Christianity. The rune stones of Scandinavia date largely from the period of Christianisation and show that women adopted the new religion with enthusiasm. As family memorials, the inscriptions are still dominated by men, but with Christianity, more and more of them were dedicated to women. Those associated with women were also more likely to be overtly Christian, such as a stone in memory of a certain Ingirun who went from central Sweden on pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

The Viking Age, then, was not just a masculine affair. Women played a full part in the voyages of raiding, trading and settlement, and the new settlements in the North Atlantic would not have survived very long had it not been for their contribution. This mobile and expansive age provided women with new opportunities, and sagas, rune stones and archaeology show that many of them were honoured and remembered accordingly.

Judith Jesch is professor of Viking studies at the University of Nottingham. Her publications include The Viking Diaspora (Routledge, 2015). You can follow her on Twitter @JudithJesch

Published on May 31, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Big Ben rings for first time

May 31

1859 Big Ben, located atop St. Stephen's tower, went into operation in London, ringing out over the Houses of Parliament in Westminster, London for the first time.

1859 Big Ben, located atop St. Stephen's tower, went into operation in London, ringing out over the Houses of Parliament in Westminster, London for the first time.

Published on May 31, 2016 02:00

May 30, 2016

Historians Draw Closer to the Tomb of the Legendary King Arthur

Ancient Origins

For many decades, researchers have tried to confirm the existence of King Arthur of Camelot, the legendary ruler that was said to have led the defense of Britain against the Saxons in the 5th century AD, and to find his final resting place. After years of speculations, the British researcher and writer Graham Philips believes he is closer than ever before.

According to the legend, King Arthur, after the battle with his enemy Mordred, was transported to the Isle of Avalon. Now, new research suggests that location may lie in a field in Shropshire, England.

Graham Phillips has been researching the life of King Arthur for many years. According to the Daily Mail, Phillips believes he has discovered evidence confirming that the medieval ruler was buried outside the village of Baschurch in Shropshire. In his latest book The Lost Tomb of King Arthur, he suggests that the most probable location of the tomb is outside the village in the old fort, dubbed ''The Berth'' or at the site of the former chapel.

The deceased King Arthur before being taken to the Isle of Avalon (

public domain

)Phillips is calling on English Heritage for permission to start archeological works at The Berth, and in the former chapel nearby the Baschurch village. Phillips has already located a pit containing a large piece of metal, which Phillips believes may be remnants of King Arthur’s shield.

The deceased King Arthur before being taken to the Isle of Avalon (

public domain

)Phillips is calling on English Heritage for permission to start archeological works at The Berth, and in the former chapel nearby the Baschurch village. Phillips has already located a pit containing a large piece of metal, which Phillips believes may be remnants of King Arthur’s shield.

Phillips told the Daily Mail:

Does the final resting place of King Arthur lie here at “The Berth” in Shropshire? (

BBC

)According to Phillip’s previous book, King Arthur lived in the Roman fortress at Wroxeter, a small village in Shropshire. Historical texts state that Arthur was born at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, and later became a famous character of many legends, related to for example his sword – the Excalibur. However, Phillips believes that a lot of the legends about Arthur are wrong, including his place of birth, which Phillips says was Shropshire, and not South West England.

Does the final resting place of King Arthur lie here at “The Berth” in Shropshire? (

BBC

)According to Phillip’s previous book, King Arthur lived in the Roman fortress at Wroxeter, a small village in Shropshire. Historical texts state that Arthur was born at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, and later became a famous character of many legends, related to for example his sword – the Excalibur. However, Phillips believes that a lot of the legends about Arthur are wrong, including his place of birth, which Phillips says was Shropshire, and not South West England.

Apart from the sites nearby the Baschurch, Phillips claims that King Arthur could also be buried in a country lane in Birch Grove village. In the 1930s, archeologists discovered part of a gravestone there with the inscription in Latin ''Here Lies…''.

At the same time as Phillips is searching for the grave of Arthur, archeologist Dr Richard Brunning, from South West Heritage, started excavations at Beckery Chapel, near Glastonbury in Somerset. The aim of the work is to accurately date an early Christian chapel. It is hoped that the investigations may shed new light on King Arthur, who is said to have visited this place, and according to the legend had a vision of Mary Magdalene and the baby Jesus there. It is the first time since 1968 that archeologists have investigated the site. Moreover, the place is also famous as a part of the stories related to the Irish saint Bridget, who visited the site in 488 AD. Previous works suggested that before the chapel, a Saxon mastery had been present on the site. The most recent works will allow the precise dating of the monastic cemetery.

Sketch of Beckery Chapel, Somerset (

geomancy.org

)The history of King Arthur is also connected with Glastonbury Abbey, which has been believed to be a place of burial of King Arthur and his wife Guinevere since the 12th century. According to an article by Jason Urbanus and archeologist Roberta Gilchrist, who head up the Glastonbury Archaeological Archive Project, the site may indeed date back to the 5th century, the time of King Arthur, but they say there is no evidence of any connection with the king. Moreover, Urbanus explained in Archaeology magazine that the burial actually belongs to 12th century monks. It seems that the legend about the burial of Arthur being at Glastonbury Abbey was created by monks of the Abbey who needed an attraction to raise money.

Sketch of Beckery Chapel, Somerset (

geomancy.org

)The history of King Arthur is also connected with Glastonbury Abbey, which has been believed to be a place of burial of King Arthur and his wife Guinevere since the 12th century. According to an article by Jason Urbanus and archeologist Roberta Gilchrist, who head up the Glastonbury Archaeological Archive Project, the site may indeed date back to the 5th century, the time of King Arthur, but they say there is no evidence of any connection with the king. Moreover, Urbanus explained in Archaeology magazine that the burial actually belongs to 12th century monks. It seems that the legend about the burial of Arthur being at Glastonbury Abbey was created by monks of the Abbey who needed an attraction to raise money.

Top image: Illustration from page 16 of ‘The Boy's King Arthur’ ( public domain )

By Natalia Klimzcak

For many decades, researchers have tried to confirm the existence of King Arthur of Camelot, the legendary ruler that was said to have led the defense of Britain against the Saxons in the 5th century AD, and to find his final resting place. After years of speculations, the British researcher and writer Graham Philips believes he is closer than ever before.

According to the legend, King Arthur, after the battle with his enemy Mordred, was transported to the Isle of Avalon. Now, new research suggests that location may lie in a field in Shropshire, England.

Graham Phillips has been researching the life of King Arthur for many years. According to the Daily Mail, Phillips believes he has discovered evidence confirming that the medieval ruler was buried outside the village of Baschurch in Shropshire. In his latest book The Lost Tomb of King Arthur, he suggests that the most probable location of the tomb is outside the village in the old fort, dubbed ''The Berth'' or at the site of the former chapel.

The deceased King Arthur before being taken to the Isle of Avalon (

public domain

)Phillips is calling on English Heritage for permission to start archeological works at The Berth, and in the former chapel nearby the Baschurch village. Phillips has already located a pit containing a large piece of metal, which Phillips believes may be remnants of King Arthur’s shield.

The deceased King Arthur before being taken to the Isle of Avalon (

public domain

)Phillips is calling on English Heritage for permission to start archeological works at The Berth, and in the former chapel nearby the Baschurch village. Phillips has already located a pit containing a large piece of metal, which Phillips believes may be remnants of King Arthur’s shield.Phillips told the Daily Mail:

''In the Oxford University Library there is a poem from the Dark Ages which refers to the kings from Wroxeter who were buried at the Churches of Bassa - and when you think about anywhere in Shropshire that sounds similar, you think of Baschurch. There is a place that matches the description just outside the village, an earthworks known as The Berth, which were two islands in a lake, though obviously the lake has now gone.''

Does the final resting place of King Arthur lie here at “The Berth” in Shropshire? (

BBC

)According to Phillip’s previous book, King Arthur lived in the Roman fortress at Wroxeter, a small village in Shropshire. Historical texts state that Arthur was born at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, and later became a famous character of many legends, related to for example his sword – the Excalibur. However, Phillips believes that a lot of the legends about Arthur are wrong, including his place of birth, which Phillips says was Shropshire, and not South West England.

Does the final resting place of King Arthur lie here at “The Berth” in Shropshire? (

BBC

)According to Phillip’s previous book, King Arthur lived in the Roman fortress at Wroxeter, a small village in Shropshire. Historical texts state that Arthur was born at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, and later became a famous character of many legends, related to for example his sword – the Excalibur. However, Phillips believes that a lot of the legends about Arthur are wrong, including his place of birth, which Phillips says was Shropshire, and not South West England.Apart from the sites nearby the Baschurch, Phillips claims that King Arthur could also be buried in a country lane in Birch Grove village. In the 1930s, archeologists discovered part of a gravestone there with the inscription in Latin ''Here Lies…''.

At the same time as Phillips is searching for the grave of Arthur, archeologist Dr Richard Brunning, from South West Heritage, started excavations at Beckery Chapel, near Glastonbury in Somerset. The aim of the work is to accurately date an early Christian chapel. It is hoped that the investigations may shed new light on King Arthur, who is said to have visited this place, and according to the legend had a vision of Mary Magdalene and the baby Jesus there. It is the first time since 1968 that archeologists have investigated the site. Moreover, the place is also famous as a part of the stories related to the Irish saint Bridget, who visited the site in 488 AD. Previous works suggested that before the chapel, a Saxon mastery had been present on the site. The most recent works will allow the precise dating of the monastic cemetery.

Sketch of Beckery Chapel, Somerset (

geomancy.org

)The history of King Arthur is also connected with Glastonbury Abbey, which has been believed to be a place of burial of King Arthur and his wife Guinevere since the 12th century. According to an article by Jason Urbanus and archeologist Roberta Gilchrist, who head up the Glastonbury Archaeological Archive Project, the site may indeed date back to the 5th century, the time of King Arthur, but they say there is no evidence of any connection with the king. Moreover, Urbanus explained in Archaeology magazine that the burial actually belongs to 12th century monks. It seems that the legend about the burial of Arthur being at Glastonbury Abbey was created by monks of the Abbey who needed an attraction to raise money.

Sketch of Beckery Chapel, Somerset (

geomancy.org

)The history of King Arthur is also connected with Glastonbury Abbey, which has been believed to be a place of burial of King Arthur and his wife Guinevere since the 12th century. According to an article by Jason Urbanus and archeologist Roberta Gilchrist, who head up the Glastonbury Archaeological Archive Project, the site may indeed date back to the 5th century, the time of King Arthur, but they say there is no evidence of any connection with the king. Moreover, Urbanus explained in Archaeology magazine that the burial actually belongs to 12th century monks. It seems that the legend about the burial of Arthur being at Glastonbury Abbey was created by monks of the Abbey who needed an attraction to raise money.Top image: Illustration from page 16 of ‘The Boy's King Arthur’ ( public domain )

By Natalia Klimzcak

Published on May 30, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Siege of Jerusalem

May 30

70 Siege of Jerusalem: Titus and his Roman legions breached the Second Wall of Jerusalem. The Jewish wars financed the construction of the Flavian Amphitheater, which took ten years to build.

70 Siege of Jerusalem: Titus and his Roman legions breached the Second Wall of Jerusalem. The Jewish wars financed the construction of the Flavian Amphitheater, which took ten years to build.

Published on May 30, 2016 01:30

May 29, 2016

Vikings: A land without kings

History Extra

A view of Þingvellir National Park in western Iceland. It was here, in AD 930, that Viking settlers established the first pan-Icelandic assembly – possibly the oldest parliamentary body in the world. © Dreamstime

About 50 years after their raids first spread terror along the coastlines of north-western Europe, the Vikings struck westward. This time some of them sailed not in search of treasure or slaves but as land-hungry warriors seeking safe havens in which to found colonies away from increasingly powerful Scandinavian kings.

Using the Faroe Islands as a stepping stone, the Vikings could reduce the risks of long voyages across the open waters of the Atlantic. By the 830s a territory in the North Atlantic had been discovered by pioneers including Flóki Vilgerðarson, who dubbed it Ísland (Iceland), in memory of the chilly winter he spent there.

However, these were strictly exploratory voyages. The first successful colonising expedition arrived later, in AD 874, led by the Norwegian Ingólf Arnarson. The following decades saw streams of settlers from Norway and the Viking colonies in the British Isles arrive in a great landnám (‘taking of the land’), and within 60 years almost all of the available territory had been claimed.

Free from the direct control of the distant Norwegian monarchs, who were much too preoccupied with their own struggles against rival magnates to interfere with the new colony, the Icelandic Vikings were able to dispense with the authority of kings. Left to their own devices for three centuries, they created a unique form of society that came to be known as the ‘Icelandic Commonwealth’.

Much about Iceland was familiar to the settlers: it was indented with fjords, at the heads of which they could establish farms. Yet it was not as fertile as the Scandinavian lands they had left behind. Much of the interior was uninhabitable, studded with volcanoes and covered with great glaciers such as the Vatnajökull, and too cold for much of each year to support agriculture.

Though there were swathes of woodland, mostly native birch, these were soon felled for firewood and building, resulting in erosion that reduced the soil’s fertility still further. The minimal agriculture possible was, therefore, pastoral, mainly cattle herding, supplemented by fishing and seal hunting.

These settlers lived at the edge of subsistence, and a cold or wet summer could lead to famine. Population density was low: Iceland’s first census, taken in 1106, counted 4,560 free farmers, which probably equates to a total population of around 10 times that number. Settlements comprised farms clustered around the longhouses of local chieftains. Farms were constructed largely with turf, and within them families cooked, ate and slept in a single long room.

A statue of Ingólf Arnarson, the Norwegian explorer who led the first successful colonising expedition to Iceland, in AD 874. © Alamy

This way of life bred a fierce independence. The Icelandic sagas tell that the original colonisers of Iceland fled the tyranny of the Norwegian king Harald Finehair. Though several of his successors planned to force the colony's obedience to the crown, the difficulties of launching such a venture to a far-flung island meant that nothing came of the idea for almost 300 years.

With no threat of invasion, there was little need to establish a central tax-raising authority to fund defence, and no Icelandic king arose to challenge his Norwegian counterpart.

Instead, power devolved to the level of local chieftains called gooar. There were 39 of these, spread across the four quarters (or várthing) into which Iceland came to be divided. But the gooar did not rule territorial domains in the manner of European feudal aristocrats; rather, their authority rested on the allegiance of retainers (or thingmenn) whose lands often intermingled with those owing loyalty to other gooar. If a thingmann found himself at odds with his chieftain, he could transfer his loyalty to another by declaring himself ‘out of thing’ with the first.

Notable deedsThis early period of ‘taking of the land’ is described in the Landnámabók, a 13th-century compilation of earlier sources, which details the names, ancestry and notable deeds of the first settlers in each district.

Once this initial phase of settlement was over, territorial disputes inevitably erupted. The danger of uncontrollable feuds prompted the settlers to formalise what had, until then, been a somewhat haphazard political system – and so, in AD 930, they established the Althing: the first pan-Icelandic assembly.

The Althing has a good claim to being the world’s oldest parliament. It was modelled on smaller meetings held in Scandinavia, where all free men had a right of hearing.

The settlers chose a suitably spectacular setting for this assembly – a site on the Öxará river in the south-west of the island, fringed by a volcanic cleft. The location was as accessible as it was spectacular, and gooar and their thingmenn journeyed there from across the island when the assembly convened in mid-June each year.

A Viking amulet in the shape of a cross, now in the National Museum of Iceland. © Bridgeman Art Library

Local courtsAt the Althing, the chieftains gathered with their retinues, serving as lawmakers – reviewing existing laws and making new ones – and as judges, presiding over cases that could not be decided in local courts.

The gathering was overseen by the lögrétta, the legislative council led by a lögsögumaor or lawspeaker who recited one-third of the Commonwealth’s laws from a great rock at the centre of the assembly site each year. It was a very public form of parliament and judiciary.

The requirement for all the gooar to attend meant that, though feuds – often bloody – did arise, the Althing acted as a safety valve, a neutral arena where settlements could be negotiated before conflict got out of hand.

By the 12th century, Icelandic society had begun to change, swayed by external nfluences – most notably Christianity. Missionaries had earlier attempted to preach in Iceland, though with little success until a concerted effort by the Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvason led Thorgeir Thorkelsson, the lawspeaker of the Althing, to declare in AD 1000 that Iceland should be Christian.

As money and land was bequeathed to the church, much of it came under the control of local landowners, and the go␣ar grew in wealth, consolidating their power. A number of chieftaincies fell into the hands of just a few families or even single individuals so, by about 1220, political power had become the exclusive preserve of just six families.

The remaining gooar ruled over what were effectively mini-kingdoms and, as the rewards of power grew, so did the violence the gooar employed to preserve and enlarge their territories. From the late 12th century, Iceland was riven by civil wars, characterised by large- scale pitched battles quite unlike earlier feuds.

Loose alliances coalesced around two powerful families, the Oddi and the Sturlungar. The latter had close ties with the royal family of Norway, whose authority had grown far stronger in the previous three centuries and now had the resources to meddle in the Icelandic civil wars.

The long reign of King Hákon Hákonarson (1217–63) saw the Norwegians gradually increase their influence in Iceland as the Sturlungar and Oddi tore the Commonwealth apart. Among the casualties of the conflict was the great Icelandic poet and historian Snorri Sturluson, murdered in 1241 on the orders of King Hákon, reputedly for his part in a conspiracy to depose him.

Battle-weary, despairing and seeing in continued independence only continued bloodshed, the Icelandic chieftains pledged their allegiance to the Norwegian king at the Althing in 1262. It was an ignominious end to the Icelandic Commonwealth, and brought to a close the experiment of rule without kings.

So it happened that, four centuries after their ancestors had fled Norway to escape the oppression of Harald Finehair, the Icelanders found themselves firmly under the thumb of his royal descendants.

The sagas of Iceland What can epic tales of war and exploration tell us about Viking Iceland?

Among the key sources for Viking history are the sagas, tales of heroism, feuding and exploration that probably began in oral form before being written down, mainly in Iceland, around the 13th century.

Some of the sagas have a historical core, such as the Orkneyinga Saga that tells the history of the earls of Orkney, or the Vinland Sagas recounting Viking voyages of exploration in North America. Even these are distorted by the demands of storytelling and the interest of the authors in glorifying one family or group’s deeds over that of another. So, for example, it is almost impossible to determine from the evidence in the sagas exactly which parts of the Americas were visited by the Vikings.

The 14th-century manuscript Flateyjarbók shows the exploits of Olaf Tryggvason. © Bridgeman Art Library

The largest group of sagas are the Íslendingasögur, ‘Icelandic family sagas’ set mainly in the first century of the Viking colony in Iceland. They tell of conflicts between Iceland’s major families, and the often tragic outcome of feuds between larger-than-life personalities over seemingly trivial slights, with the events often unfolding over several generations.

Njál’s Saga tells how Njáll Thorgeirsson sucked into the feuds sparked by the murderous behaviour of his friend Gunnar Hámundarson. Njáll was burnt to death in his farmstead by a posse bent on revenge for the murder of one of Gunnar’s cousins by Njáll’s son.

The sagas provide a vital source of evidence about the organisation of Viking society, and offer us a unique window on those elements within it that are overlooked by more conventional history.

For example, Saga of the Greenlanders documents the story of Freydís, daughter of Erik the Red (discoverer of Greenland), who organised and led a voyage to North America; this gives us an insight into the powerful role some women played in trading missions. The role of Gunnar’s wife, Hallgero, in provoking the saga’s central feud also shows that Viking women did not play a purely passive role in the quarrels of their menfolk.

Philip Parker is a writer and historian specialising in late antiquity and early medieval Europe.

A view of Þingvellir National Park in western Iceland. It was here, in AD 930, that Viking settlers established the first pan-Icelandic assembly – possibly the oldest parliamentary body in the world. © Dreamstime

About 50 years after their raids first spread terror along the coastlines of north-western Europe, the Vikings struck westward. This time some of them sailed not in search of treasure or slaves but as land-hungry warriors seeking safe havens in which to found colonies away from increasingly powerful Scandinavian kings.

Using the Faroe Islands as a stepping stone, the Vikings could reduce the risks of long voyages across the open waters of the Atlantic. By the 830s a territory in the North Atlantic had been discovered by pioneers including Flóki Vilgerðarson, who dubbed it Ísland (Iceland), in memory of the chilly winter he spent there.

However, these were strictly exploratory voyages. The first successful colonising expedition arrived later, in AD 874, led by the Norwegian Ingólf Arnarson. The following decades saw streams of settlers from Norway and the Viking colonies in the British Isles arrive in a great landnám (‘taking of the land’), and within 60 years almost all of the available territory had been claimed.

Free from the direct control of the distant Norwegian monarchs, who were much too preoccupied with their own struggles against rival magnates to interfere with the new colony, the Icelandic Vikings were able to dispense with the authority of kings. Left to their own devices for three centuries, they created a unique form of society that came to be known as the ‘Icelandic Commonwealth’.

Much about Iceland was familiar to the settlers: it was indented with fjords, at the heads of which they could establish farms. Yet it was not as fertile as the Scandinavian lands they had left behind. Much of the interior was uninhabitable, studded with volcanoes and covered with great glaciers such as the Vatnajökull, and too cold for much of each year to support agriculture.

Though there were swathes of woodland, mostly native birch, these were soon felled for firewood and building, resulting in erosion that reduced the soil’s fertility still further. The minimal agriculture possible was, therefore, pastoral, mainly cattle herding, supplemented by fishing and seal hunting.

These settlers lived at the edge of subsistence, and a cold or wet summer could lead to famine. Population density was low: Iceland’s first census, taken in 1106, counted 4,560 free farmers, which probably equates to a total population of around 10 times that number. Settlements comprised farms clustered around the longhouses of local chieftains. Farms were constructed largely with turf, and within them families cooked, ate and slept in a single long room.

A statue of Ingólf Arnarson, the Norwegian explorer who led the first successful colonising expedition to Iceland, in AD 874. © Alamy

This way of life bred a fierce independence. The Icelandic sagas tell that the original colonisers of Iceland fled the tyranny of the Norwegian king Harald Finehair. Though several of his successors planned to force the colony's obedience to the crown, the difficulties of launching such a venture to a far-flung island meant that nothing came of the idea for almost 300 years.

With no threat of invasion, there was little need to establish a central tax-raising authority to fund defence, and no Icelandic king arose to challenge his Norwegian counterpart.

Instead, power devolved to the level of local chieftains called gooar. There were 39 of these, spread across the four quarters (or várthing) into which Iceland came to be divided. But the gooar did not rule territorial domains in the manner of European feudal aristocrats; rather, their authority rested on the allegiance of retainers (or thingmenn) whose lands often intermingled with those owing loyalty to other gooar. If a thingmann found himself at odds with his chieftain, he could transfer his loyalty to another by declaring himself ‘out of thing’ with the first.

Notable deedsThis early period of ‘taking of the land’ is described in the Landnámabók, a 13th-century compilation of earlier sources, which details the names, ancestry and notable deeds of the first settlers in each district.

Once this initial phase of settlement was over, territorial disputes inevitably erupted. The danger of uncontrollable feuds prompted the settlers to formalise what had, until then, been a somewhat haphazard political system – and so, in AD 930, they established the Althing: the first pan-Icelandic assembly.

The Althing has a good claim to being the world’s oldest parliament. It was modelled on smaller meetings held in Scandinavia, where all free men had a right of hearing.

The settlers chose a suitably spectacular setting for this assembly – a site on the Öxará river in the south-west of the island, fringed by a volcanic cleft. The location was as accessible as it was spectacular, and gooar and their thingmenn journeyed there from across the island when the assembly convened in mid-June each year.

A Viking amulet in the shape of a cross, now in the National Museum of Iceland. © Bridgeman Art Library

Local courtsAt the Althing, the chieftains gathered with their retinues, serving as lawmakers – reviewing existing laws and making new ones – and as judges, presiding over cases that could not be decided in local courts.

The gathering was overseen by the lögrétta, the legislative council led by a lögsögumaor or lawspeaker who recited one-third of the Commonwealth’s laws from a great rock at the centre of the assembly site each year. It was a very public form of parliament and judiciary.

The requirement for all the gooar to attend meant that, though feuds – often bloody – did arise, the Althing acted as a safety valve, a neutral arena where settlements could be negotiated before conflict got out of hand.

By the 12th century, Icelandic society had begun to change, swayed by external nfluences – most notably Christianity. Missionaries had earlier attempted to preach in Iceland, though with little success until a concerted effort by the Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvason led Thorgeir Thorkelsson, the lawspeaker of the Althing, to declare in AD 1000 that Iceland should be Christian.

As money and land was bequeathed to the church, much of it came under the control of local landowners, and the go␣ar grew in wealth, consolidating their power. A number of chieftaincies fell into the hands of just a few families or even single individuals so, by about 1220, political power had become the exclusive preserve of just six families.

The remaining gooar ruled over what were effectively mini-kingdoms and, as the rewards of power grew, so did the violence the gooar employed to preserve and enlarge their territories. From the late 12th century, Iceland was riven by civil wars, characterised by large- scale pitched battles quite unlike earlier feuds.

Loose alliances coalesced around two powerful families, the Oddi and the Sturlungar. The latter had close ties with the royal family of Norway, whose authority had grown far stronger in the previous three centuries and now had the resources to meddle in the Icelandic civil wars.

The long reign of King Hákon Hákonarson (1217–63) saw the Norwegians gradually increase their influence in Iceland as the Sturlungar and Oddi tore the Commonwealth apart. Among the casualties of the conflict was the great Icelandic poet and historian Snorri Sturluson, murdered in 1241 on the orders of King Hákon, reputedly for his part in a conspiracy to depose him.

Battle-weary, despairing and seeing in continued independence only continued bloodshed, the Icelandic chieftains pledged their allegiance to the Norwegian king at the Althing in 1262. It was an ignominious end to the Icelandic Commonwealth, and brought to a close the experiment of rule without kings.

So it happened that, four centuries after their ancestors had fled Norway to escape the oppression of Harald Finehair, the Icelanders found themselves firmly under the thumb of his royal descendants.

The sagas of Iceland What can epic tales of war and exploration tell us about Viking Iceland?

Among the key sources for Viking history are the sagas, tales of heroism, feuding and exploration that probably began in oral form before being written down, mainly in Iceland, around the 13th century.

Some of the sagas have a historical core, such as the Orkneyinga Saga that tells the history of the earls of Orkney, or the Vinland Sagas recounting Viking voyages of exploration in North America. Even these are distorted by the demands of storytelling and the interest of the authors in glorifying one family or group’s deeds over that of another. So, for example, it is almost impossible to determine from the evidence in the sagas exactly which parts of the Americas were visited by the Vikings.

The 14th-century manuscript Flateyjarbók shows the exploits of Olaf Tryggvason. © Bridgeman Art Library

The largest group of sagas are the Íslendingasögur, ‘Icelandic family sagas’ set mainly in the first century of the Viking colony in Iceland. They tell of conflicts between Iceland’s major families, and the often tragic outcome of feuds between larger-than-life personalities over seemingly trivial slights, with the events often unfolding over several generations.

Njál’s Saga tells how Njáll Thorgeirsson sucked into the feuds sparked by the murderous behaviour of his friend Gunnar Hámundarson. Njáll was burnt to death in his farmstead by a posse bent on revenge for the murder of one of Gunnar’s cousins by Njáll’s son.

The sagas provide a vital source of evidence about the organisation of Viking society, and offer us a unique window on those elements within it that are overlooked by more conventional history.

For example, Saga of the Greenlanders documents the story of Freydís, daughter of Erik the Red (discoverer of Greenland), who organised and led a voyage to North America; this gives us an insight into the powerful role some women played in trading missions. The role of Gunnar’s wife, Hallgero, in provoking the saga’s central feud also shows that Viking women did not play a purely passive role in the quarrels of their menfolk.

Philip Parker is a writer and historian specialising in late antiquity and early medieval Europe.

Published on May 29, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Charles II arrives in London

May 29

1660 Charles II arrived in London from exile in the Netherlands to reclaim his throne. Charles II was also born on this day.

1660 Charles II arrived in London from exile in the Netherlands to reclaim his throne. Charles II was also born on this day.

Published on May 29, 2016 02:00

May 28, 2016

Why did the Vikings' violent raids begin?

History Extra

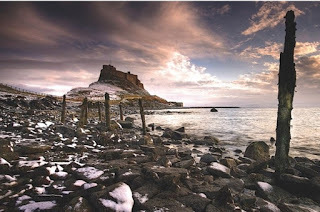

The ‘holy island’ of Lindisfarne, just off the coast of Northumberland. A savage raid on the island’s monastery in 793 heralded the start of England’s Viking era. (Steve Boote)

The ‘holy island’ of Lindisfarne, just off the coast of Northumberland. A savage raid on the island’s monastery in 793 heralded the start of England’s Viking era. (Steve Boote)

On a clear day, a Viking longship at sea could be seen some 18 nautical miles away. With a favourable wind, that distance could be covered in about an hour – which was perhaps all the time that the monks at Lindisfarne had to prepare themselves against attack on one fateful day in 793. This was the raid that signalled the start of the violence associated with the onset of the Viking age. “We and our fathers have now lived in this fair land for nearly 350 years, and never before has such an atrocity been seen in Britain as we have now suffered at the hands of a pagan people. Such a voyage was not thought possible. The church of Saint Cuthbert is spattered with the blood of the priests of God, stripped of all its furnishings, exposed to the plundering of pagans – a place more sacred than any in Britain.” The extract is from a letter, written in the wake of the attack, to King Æthelred of Northumbria by Alcuin. Alcuin had been a monk in York before accepting an invitation in 781 to join Charlemagne at his court in Aachen, where he became the Frankish king’s leading spiritual advisor. Historians have been inclined to take Alcuin’s astonishment at the raid at face value, and supposed the Vikings to be a wholly unknown quantity. Yet in the same letter Alcuin rebuked Æthelred and his courtiers for aping the fashions of the heathens: “Consider the luxurious dress, hair and behaviour of leaders and people,” he urged the king. “See how you have wanted to copy the pagan way of cutting hair and beards. Are not these the people whose terror threatens us, yet you want to copy their hair?” The obvious conclusion is that, at the time of the raid, the Northumbrians were already familiar with their Norwegian visitors. What was new was the violence. Lindisfarne turned out to be the start of a wave of similar attacks on monasteries in northern Britain. Alcuin, with his local knowledge, warned the religious communities at nearby Wearmouth and Jarrow to be on their guard: “You live by the sea from whence this plague first came.”

A picture stone depicting the Lindisfarne attack. (Getty) In 794, Vikings “ravaged in Northumbria, and plundered Ecgfrith’s monastery at Donemuthan”. The 12th‑century historian Symeon of Durham identified this as the monastery at Jarrow, and reported that its protector, Saint Cuthbert, had not let the heathens go unpunished, “for their chief was killed by the English… And these things befell them rightly, for they had gravely injured those who had not injured them.” Shetland and Orkney were probably overrun during this first wave of violence, and the indigenous population of Picts wiped out so swiftly that local place names and the names of natural phenomena such as rivers and mountains vanished, to be replaced by Scandinavian names. Ireland and the Western Isles of Scotland suffered, too. The Annals of Ulster report the burning in 795 of the monastery at Rechru, and the Isle of Skye “overwhelmed and laid waste”. Iona was attacked for a first time in 795 and again in 802. In a third raid in 806 the monastery was torched and the community of 68 wiped out. Work started the following year on a safe refuge for the revived community at Kells in Ireland. In 799 the island monastery of Noirmoutier off the north-west coast of France was attacked for the first time. By 836 it had been raided so often that its monks also abandoned the site and sought refuge in a safer location. It soon become clear, however, that there was no such thing as a safe refuge.

Charlemagne is crowned by Pope Leo III in a 14th-century French manuscript. The emperors’s violent subjugation of heathens may have provoked the Viking raids. (Getty) Best form of defence Why was there such hatred in the attacks, and why did they start in 793, rather than 743, or 843? To look for a triggering event we need to examine the political situation in northern Europe at the time. At the commencement of the Viking age, the major political powers in the world were Byzantium in the east; the Muslims, whose expansion had taken them as far as Turkistan and Asia Minor to create an Islamic barrier between the northern and southern hemispheres; and the Franks, who had become the dominant tribe among the successor states after the fall of the Roman empire in the west. Charlemagne became sole ruler of the Franks in 771. He took seriously the missionary obligations imposed on him by his position as the most powerful ruler in western Christendom, and expended a huge amount of energy on the subjugation of the heathen Saxons on his north-east border. In 772, his forces crossed into Saxon territory and destroyed Irminsul, the sacred tree that was their most holy totem. In 779, Widukind, the Saxon leader, was defeated in battle at Bocholt and Saxony taken over and divided into missionary districts. Charlemagne himself presided over a number of mass baptisms. In 782, his armies forcibly baptised and then executed 4,500 Saxon captives at Verden, on the banks of the river Aller. Campaigns of enforced resettlement followed, but resistance continued until a final insurrection was put down in 804. By this time Charlemagne had already been rewarded for his missionary activities by Pope Leo III who in Rome in AD 800 crowned him imperator – emperor not of a geographical area nor even of a collection of peoples but of the abstract conception of Christendom as a single community. With their physical subjugation complete, the cultural subjugation of the Saxons followed. Death was the penalty for eating meat during Lent; death for cremating the dead in accordance with heathen rites; death for rejecting baptism. Several times, in the course of the campaign of resistance, Widukind sought refuge across the border with his brother-in-law Sigfrid, a Danish king. News of Charlemagne’s depredations, and in particular the Verden massacre, must have travelled like a shock wave through Danish territory and beyond. How should the heathen Scandinavians react to the threat? For, whether they knew it or not, they were on Alcuin’s list of peoples to be converted. In 789 he wrote to a friend working among the Saxons: “Tell me, is there any hope of our converting the Danes?” The question for the Vikings was: should they simply wait for Charlemagne’s armies to arrive and set about the task? Or should they fight to defend their culture? A military campaign against the might of Frankish Christendom was out of the question. However, the Christian monasteries – such as Lindisfarne – dotted around the rim of northern Europe were symbolically important and, in the parlance of modern terrorist warfare, ‘soft targets’. So, with an indifference to the humanity of their victims as complete as that of Charlemagne’s towards the Saxons, these first Viking raiders were able to set off on a punishing series of attacks in the grip of a no-holds-barred rage directed at Christian ‘others’. The Christian annalists who documented Viking violence insistently saw the conflict as a battle between religious cultures. A century after the first attack on Lindisfarne, Asser, in his biography of Alfred the Great, continued to refer to the much larger bands of Vikings who had by now established themselves along the eastern seaboard of England as “the pagans” (pagani), and to their victims as “Christians” (christiani).