MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 92

June 25, 2016

Amateurs Find Largest Ever Viking Gold Hoard in Denmark

Ancient Origins

Three amateur archaeologists recently found the largest Viking gold hoard ever discovered in Denmark. At 900 grams (1.948 pounds), the hoard consists of seven beautifully worked bracelets, six of gold and one of silver. The silver piece weighs about 90 grams.

Three amateur archaeologists recently found the largest Viking gold hoard ever discovered in Denmark. At 900 grams (1.948 pounds), the hoard consists of seven beautifully worked bracelets, six of gold and one of silver. The silver piece weighs about 90 grams.

At Sønderskov Museum we are extremely excited about six gold bracelets that were recently handed in to the museum. They were discovered by Poul, Kristen and Marie that make up the metal detector group Team Rainbow,” says the museum’s Facebook page. Their full names are Poul Nørgaard Pedersen, Marie Aagaard Larsen and Kristen Dreiøe.

The group Team Rainbow Power includes Poul Nørgaard Pedersen, Marie Aagaard Larsen and Kristen Dreiøe (Photo by Jørn Larsen)

The group Team Rainbow Power includes Poul Nørgaard Pedersen, Marie Aagaard Larsen and Kristen Dreiøe (Photo by Jørn Larsen)

“We really felt that we had found the gold at the end of the rainbow when we found the first ring, but as there appeared more up, it was almost unreal,” Ms. Larsen told the museum. Her husband is Dreiøe, and Pedersen is their friend.

Sønderskov Museum curator and archaeologist Lars Grundvad said: “At the museum we had talked about that it could be interesting to explore the area with a metal detector, because a gold chain of 67 grams was found in 1911. But that amateur archaeologists in the course of a few days would find seven Viking bangles, I had in my wildest dreams never imagined.”

He said the seven bracelets are likely connected to the one found in 1911.

The Denmark National Museum’s Viking expert, Peter Pentz said: “To find just one of these rings is huge, so it is something special to find seven. The Viking Age is actually the ‘silver age’ when it comes to hoards. The vast majority of them contain only silver. If there is gold, it is always a small part, not like here, the majority.”

One of the bracelets; note the dragon heads. (Photo by Arnold Mikkelsen of

the Denmark National Museum

)Mr. Pentz said there’s no doubt in his mind the treasure belonged to Viking elite, and the bracelets may have been used by a chief as alliance gifts, or as rewards or oath rings for his men.

One of the bracelets; note the dragon heads. (Photo by Arnold Mikkelsen of

the Denmark National Museum

)Mr. Pentz said there’s no doubt in his mind the treasure belonged to Viking elite, and the bracelets may have been used by a chief as alliance gifts, or as rewards or oath rings for his men.

According to Hurstwic.org in an article on Viking social classes, their society was divided into three groups: the middle class karls, the noble jarls and the slaves or bondsmen þræll. People could move from one class to another, the article states, adding:

Above [the karls] were the jarls, the noble class. The stories indicate that jarls lived in fine halls and led refined lives filled with a myriad of activities. But archaeological evidence to back up these details is lacking.Jarls were distinguished by their wealth, measured in terms of followers, treasure, ships, and estates. The eldest son of the jarl was on the fast track to becoming the next jarl. But, by gaining enough fame and wealth, a karl could become a jarl. The power of a jarl depended upon the goodwill of his supporters. The jarl's essential task was to uphold the security, prosperity, and honor of his followers.But why did such fabulous wealth end up in the ground? both Pentz and Grundvad ask. Mr. Pentz said perhaps someone buried it with the intent to go back and retrieve it later, but for some reason was unable to.

“It would be interesting to examine the wreck site closer as it might enlighten us as to why this valuable treasure has ended up in the ground,” Mr. Pentz said.

Mr. Grundvad agreed an archaeological survey would gives clues as to why the treasure was buried. He hopes the news of the find will help archaeologists raise money for an excavation, perhaps this fall, of the site, which is being kept secret for now.

Another find, of 750 grams (1.65 pounds), from Vester Vestad in south Jutland, was the largest Viking gold hoard found previously.

Team Rainbow Power will be compensated before the hoard goes on display at the Denmark National Museum.

Featured image: The seven bracelets likely belonged to a Viking nobleman and may have been used as oath rings for his men. (Denmark National Museum photo)

By Mark Miller

Three amateur archaeologists recently found the largest Viking gold hoard ever discovered in Denmark. At 900 grams (1.948 pounds), the hoard consists of seven beautifully worked bracelets, six of gold and one of silver. The silver piece weighs about 90 grams.

Three amateur archaeologists recently found the largest Viking gold hoard ever discovered in Denmark. At 900 grams (1.948 pounds), the hoard consists of seven beautifully worked bracelets, six of gold and one of silver. The silver piece weighs about 90 grams.At Sønderskov Museum we are extremely excited about six gold bracelets that were recently handed in to the museum. They were discovered by Poul, Kristen and Marie that make up the metal detector group Team Rainbow,” says the museum’s Facebook page. Their full names are Poul Nørgaard Pedersen, Marie Aagaard Larsen and Kristen Dreiøe.

The group Team Rainbow Power includes Poul Nørgaard Pedersen, Marie Aagaard Larsen and Kristen Dreiøe (Photo by Jørn Larsen)

The group Team Rainbow Power includes Poul Nørgaard Pedersen, Marie Aagaard Larsen and Kristen Dreiøe (Photo by Jørn Larsen)“One of the bracelets was decorated in the Jelling style – an art style that is thought to be closely related to the upper class in Viking society. This could mean that some of those closest to the king were based in Vejen Municipality.”The group found the pieces in a field in Vejen, which is in Jutland. Ms. Larsen told the Danish National Museum (press release in Danish) that she was using her metal detector for just 10 minutes when she struck gold. The Danish National Museum said the “bangles” date to the 900s AD.

“We really felt that we had found the gold at the end of the rainbow when we found the first ring, but as there appeared more up, it was almost unreal,” Ms. Larsen told the museum. Her husband is Dreiøe, and Pedersen is their friend.

Sønderskov Museum curator and archaeologist Lars Grundvad said: “At the museum we had talked about that it could be interesting to explore the area with a metal detector, because a gold chain of 67 grams was found in 1911. But that amateur archaeologists in the course of a few days would find seven Viking bangles, I had in my wildest dreams never imagined.”

He said the seven bracelets are likely connected to the one found in 1911.

The Denmark National Museum’s Viking expert, Peter Pentz said: “To find just one of these rings is huge, so it is something special to find seven. The Viking Age is actually the ‘silver age’ when it comes to hoards. The vast majority of them contain only silver. If there is gold, it is always a small part, not like here, the majority.”

One of the bracelets; note the dragon heads. (Photo by Arnold Mikkelsen of

the Denmark National Museum

)Mr. Pentz said there’s no doubt in his mind the treasure belonged to Viking elite, and the bracelets may have been used by a chief as alliance gifts, or as rewards or oath rings for his men.

One of the bracelets; note the dragon heads. (Photo by Arnold Mikkelsen of

the Denmark National Museum

)Mr. Pentz said there’s no doubt in his mind the treasure belonged to Viking elite, and the bracelets may have been used by a chief as alliance gifts, or as rewards or oath rings for his men.According to Hurstwic.org in an article on Viking social classes, their society was divided into three groups: the middle class karls, the noble jarls and the slaves or bondsmen þræll. People could move from one class to another, the article states, adding:

Above [the karls] were the jarls, the noble class. The stories indicate that jarls lived in fine halls and led refined lives filled with a myriad of activities. But archaeological evidence to back up these details is lacking.Jarls were distinguished by their wealth, measured in terms of followers, treasure, ships, and estates. The eldest son of the jarl was on the fast track to becoming the next jarl. But, by gaining enough fame and wealth, a karl could become a jarl. The power of a jarl depended upon the goodwill of his supporters. The jarl's essential task was to uphold the security, prosperity, and honor of his followers.But why did such fabulous wealth end up in the ground? both Pentz and Grundvad ask. Mr. Pentz said perhaps someone buried it with the intent to go back and retrieve it later, but for some reason was unable to.

“It would be interesting to examine the wreck site closer as it might enlighten us as to why this valuable treasure has ended up in the ground,” Mr. Pentz said.

Mr. Grundvad agreed an archaeological survey would gives clues as to why the treasure was buried. He hopes the news of the find will help archaeologists raise money for an excavation, perhaps this fall, of the site, which is being kept secret for now.

Another find, of 750 grams (1.65 pounds), from Vester Vestad in south Jutland, was the largest Viking gold hoard found previously.

Team Rainbow Power will be compensated before the hoard goes on display at the Denmark National Museum.

Featured image: The seven bracelets likely belonged to a Viking nobleman and may have been used as oath rings for his men. (Denmark National Museum photo)

By Mark Miller

Published on June 25, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Battle of Fontenay-en-Puisaye

June 25

841 In the Battle of Fontenay-en-Puisaye, forces led by Charles the Bald and Louis the German defeated the armies of Lothair I of Italy and Pepin II of Aquitaine.

841 In the Battle of Fontenay-en-Puisaye, forces led by Charles the Bald and Louis the German defeated the armies of Lothair I of Italy and Pepin II of Aquitaine.

Published on June 25, 2016 02:00

June 24, 2016

Egyptologists Set to Unravel the Identity of Mystery Pharaoh from Tomb KV55

Ancient Origins

An ancient Eygptian tomb excavated in 1907 still holds mysteries. Chief among them: Who exactly was buried there? Was it Akhenaten, a radical pharaoh who overturned all the Egyptians knew about their many deities and elevated one “true” god above all others—Aten? A new study will explore this question and try to answer once and for all who was the occupant of the mystery sarcophagus in tomb KV55 of the Valley of Kings.

No one has ever presented any definitive evidence that the sarcophagus had contained Akhenaten’s remains, AhramOnline quotes Elham Salah, head of the Antiquities Ministry’s Museums Department, as saying. Dr. Salah added that the sarcophagus is one of the most controversial among Egypt’s many known ancient burials.

Bust of Pharaoh Akhenaton (

Wikimedia Commons

)The Ministry of Antiquities will continue a study of the sarcophagus begun in 2015 with help of a $28,500 grant from the American Research Center in Egypt.

Bust of Pharaoh Akhenaton (

Wikimedia Commons

)The Ministry of Antiquities will continue a study of the sarcophagus begun in 2015 with help of a $28,500 grant from the American Research Center in Egypt.“Salah … told Ahram Online that the study is being carried out on a collection of 500 gold sheets found in a box in storage at the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir along with the remains of a skull and a handwritten note in French,” the newspaper states.

Pieces of the skull found in the sarcophagus in KV55 (AhramOnline photo)The note dates to the opening of KV55. It says the 500 gold sheets were in a sarcophagus in the tomb, but doesn’t specify which sarcophagus, AhramOnline states. The initial phase of the study determined the gold sheets could have been in sarcophagus in question.

Pieces of the skull found in the sarcophagus in KV55 (AhramOnline photo)The note dates to the opening of KV55. It says the 500 gold sheets were in a sarcophagus in the tomb, but doesn’t specify which sarcophagus, AhramOnline states. The initial phase of the study determined the gold sheets could have been in sarcophagus in question. The gold sheets that were in a sarcophagus in the tomb (Photo by

AhramOnline

)Islam Ezat, a staffer with the ministry’s scientific office, said the study is being done by skilled Egyptian archaeologists and restorers. He told AhramOnline the study may answer once and for all who the owner of the sarcophagus and tomb was.

The gold sheets that were in a sarcophagus in the tomb (Photo by

AhramOnline

)Islam Ezat, a staffer with the ministry’s scientific office, said the study is being done by skilled Egyptian archaeologists and restorers. He told AhramOnline the study may answer once and for all who the owner of the sarcophagus and tomb was.KV55 contained a variety of artifacts and a single body, as Ancient Origins reported in January 2015. Identification of the body has been complicated by the fact that the artifacts appear to belong to several different individuals. It has been speculated that the tomb was created in a hurry, and that the individual buried there had been previously laid to rest elsewhere. With many different possibilities for the identity of the mummy – ranging from Queen Tiye (Akhenaten’s mother), to King Smenkhkare – researchers who set out to identify the mummy were presented with a puzzling challenge.

In January 1907, financier Theodore M. Davis hired archaeologist Edward R. Ayrton and his team to conduct excavations in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. The Valley of the Kings is an area in Egypt located on the West bank of the Nile River, across from the city of Thebes. Almost all of the pharaohs from Egypt’s Golden Age are buried in this famous valley.

The KV55 tomb is small and simple. The entrance includes a flight of 20 stairs. At the time of the discovery, the entrance and stairs were covered by rubble. A sloping corridor leads to the tomb, which contains a single chamber and a small niche. Within the tomb, at the time of discovery, were four canopic jars, a gilded wooden shrine, remains of boxes, seal impressions and a vase stand. It also had pieces of furniture, a silver goose head, two clay bricks, and a single coffin. The coffin had been desecrated, with parts of the beautifully decorated face having been removed.

One of the four Egyptian alabaster canopic jars found in KV55, depicting what is thought to be the likeness of Queen Kiya. Wikimedia,

CC BY-SA 2.5

Overall, the physical appearance of the tomb is unremarkable. However, the contents became more puzzling and mysterious as they were examined, as each piece appeared to be connected to different individuals. This made efforts to identify the remains within the tomb more difficult. According to some researchers, the presence of this variety of items indicates that whoever was entombed here was done so in a hurry, or possibly the individual was buried somewhere else, and then relocated to KV55 at a later date.

One of the four Egyptian alabaster canopic jars found in KV55, depicting what is thought to be the likeness of Queen Kiya. Wikimedia,

CC BY-SA 2.5

Overall, the physical appearance of the tomb is unremarkable. However, the contents became more puzzling and mysterious as they were examined, as each piece appeared to be connected to different individuals. This made efforts to identify the remains within the tomb more difficult. According to some researchers, the presence of this variety of items indicates that whoever was entombed here was done so in a hurry, or possibly the individual was buried somewhere else, and then relocated to KV55 at a later date.While identifying the remains in the tomb has been challenging, there are many clues in the items found within the tomb. Many of these items have been linked to King Akhenaten. The four canopic jars within the tomb were all empty. They contained effigies of four women, believed to be the daughters of Akhenaten, and may have been created for Kiya, one of Akhenaten’s wives. The gilded shrine appeared to have been created for Akhenaten’s mother, Queen Tiye. And Akhenaten’s name was on the two clay bricks.

Profile view of a skull recovered from KV55.

Public Domain

In 2010, some experts had concluded they were nearly certain the remains were of Akhenaten, but the identity is now being studied further.

Profile view of a skull recovered from KV55.

Public Domain

In 2010, some experts had concluded they were nearly certain the remains were of Akhenaten, but the identity is now being studied further.Featured image: The desecrated royal coffin found in Tomb KV55. Wikimedia, CC BY 2.0

By Mark Miller

Published on June 24, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Aqua Traiana inaugurated

June 24

109 The Aqua Traiana was inaugurated by Emperor Trajan, the aqueduct channeled water from Lake Bracciano, 25 miles north-west of Rome.

109 The Aqua Traiana was inaugurated by Emperor Trajan, the aqueduct channeled water from Lake Bracciano, 25 miles north-west of Rome.

Published on June 24, 2016 02:00

June 23, 2016

The Impressive Gaulcross Hoard: 100 Roman-Era Silver Pieces Unearthed in Scotland

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists discovered a hoard of 100 silver items, including coins and jewelry, which come from the 4th and 5th centuries AD. The treasure belongs to the period of the Roman Empire’s domination in Scotland, or perhaps later.

Almost 200 years ago, a team of Scottish laborers cleared a rocky field with dynamite. They discovered three magnificent silver artifacts : a chain, a spiral bangle, and a hand pin. However, they didn't search any deeper to check if there were any more treasures. They turned the field into a farmland and excavations were forgotten.

Now, archaeologists have returned to the site and discovered a hoard (a group of valuable objects that is sometimes purposely buried underground) of 100 silver items. According to Live Science , the treasure is called the Gaulcross hoard. The artifacts belonged to the Pict people who lived in Scotland before, during, and after the Roman era.

Silver plaque from the Norrie's Law hoard (7th-century Pictish silver hoard), Fife, with double disc and Z-rod symbol. (

CC BY SA 3.0

)The artifacts were found by a team led by Gordon Noble, head of archaeology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. When they started work in the field, they didn't think to search for more artifacts, but were trying to learn more about the context of the discovery made nearly two centuries ago. The researchers claim that the field also contained two man-made stone circles - one dating to the Neolithic period and the other the Bronze Age (1670 – 1500 BC).

Silver plaque from the Norrie's Law hoard (7th-century Pictish silver hoard), Fife, with double disc and Z-rod symbol. (

CC BY SA 3.0

)The artifacts were found by a team led by Gordon Noble, head of archaeology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. When they started work in the field, they didn't think to search for more artifacts, but were trying to learn more about the context of the discovery made nearly two centuries ago. The researchers claim that the field also contained two man-made stone circles - one dating to the Neolithic period and the other the Bronze Age (1670 – 1500 BC).

The three previously discovered pieces were given to Banff Museum in Aberdeenshire, and are now on loan and display at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.

The surviving objects from the nineteenth-century Gaulcross hoard find. (

National Museums Scotland

)In 2013, two groups of researchers studied the field in northeastern Scotland with the help of metal detectors. It was the first time when researchers explored the field after such a long time. During the second day of work, they uncovered three Late-Roman-era silver "siliquae," or coins, that dated to the 4th or 5th century AD.

The surviving objects from the nineteenth-century Gaulcross hoard find. (

National Museums Scotland

)In 2013, two groups of researchers studied the field in northeastern Scotland with the help of metal detectors. It was the first time when researchers explored the field after such a long time. During the second day of work, they uncovered three Late-Roman-era silver "siliquae," or coins, that dated to the 4th or 5th century AD.

They also found a part of a silver bracelet, silver strap-end, and several pieces of folded hacksilver (pieces of cut or bent silver). They examined the field over the next 18 months, and as a result, they unearthed 100 pieces of silver all together.

3,000-year-old broken weapons found in Scotland loch reveal ancient ritual offerings to gods The Missing Pieces: Unraveling the history of the Lewis Chessmen The silver was not mined in Scotland during the Roman period, and instead came from somewhere else in the Roman world. During the '' Late Roman period, silver was recycled and recast into high-status objects that underpinned the development of elite society in the post-Roman period''. The researchers believe that some of these silver pieces, such as the chunks of silver called ingots, may have served as currency, much as a gold bar did in more modern times.

The recent discoveries help shed light on the date of the Gaulcross hoard. It seems that some of the objects were connected with the elites. The silver hand pins and bracelets are very rare finds, so the researchers concluded that the objects would have belonged to some of the most powerful members of the post-Roman society.

Some of the finds from Gaulcross: A) the lunate/crescent-shaped pendant with two double-loops; B) silver hemispheres; C) a small, zoomorphic penannular brooch; D) one of the bracelet fragments with a Late Roman siliquae pinched inside (

National Museums Scotland

)Another important hoard has previously been uncovered in Scotland. Actually, on October 13, 2014, April Holloway of Ancient Origins reported on the discovery of one of the most significant Viking hoards found there to date. She wrote:

Some of the finds from Gaulcross: A) the lunate/crescent-shaped pendant with two double-loops; B) silver hemispheres; C) a small, zoomorphic penannular brooch; D) one of the bracelet fragments with a Late Roman siliquae pinched inside (

National Museums Scotland

)Another important hoard has previously been uncovered in Scotland. Actually, on October 13, 2014, April Holloway of Ancient Origins reported on the discovery of one of the most significant Viking hoards found there to date. She wrote:

[image error]Detail of the Carolingian vessel of the famous Viking hoard. (

Historic Environment Scotland

)Holloway wrote that the Vikings “conducted numerous raids on Carolingian lands between 8th and 10th century AD” and explained that in a “few records, the Vikings are thought to have led their first raids in Scotland on the island of Iona in 794.”

[image error]Detail of the Carolingian vessel of the famous Viking hoard. (

Historic Environment Scotland

)Holloway wrote that the Vikings “conducted numerous raids on Carolingian lands between 8th and 10th century AD” and explained that in a “few records, the Vikings are thought to have led their first raids in Scotland on the island of Iona in 794.”

The Vikings attacks led to the downfall of the Picts. As Holloway reported:

The Aberlemno Serpent Stone, Class I Pictish stone with Pictish symbols, showing (top to bottom) the serpent, the double disc and Z-rod and the mirror and comb. (Catfish Jim and the soapdish/

CC BY SA 3.0

)Top Image: The Gaulcross silver hoard, including a silver ingot, Hacksilber and folded bracelets. Source:

National Museums Scotland

The Aberlemno Serpent Stone, Class I Pictish stone with Pictish symbols, showing (top to bottom) the serpent, the double disc and Z-rod and the mirror and comb. (Catfish Jim and the soapdish/

CC BY SA 3.0

)Top Image: The Gaulcross silver hoard, including a silver ingot, Hacksilber and folded bracelets. Source:

National Museums Scotland

By Natalia Klimzcak

Archaeologists discovered a hoard of 100 silver items, including coins and jewelry, which come from the 4th and 5th centuries AD. The treasure belongs to the period of the Roman Empire’s domination in Scotland, or perhaps later.

Almost 200 years ago, a team of Scottish laborers cleared a rocky field with dynamite. They discovered three magnificent silver artifacts : a chain, a spiral bangle, and a hand pin. However, they didn't search any deeper to check if there were any more treasures. They turned the field into a farmland and excavations were forgotten.

Now, archaeologists have returned to the site and discovered a hoard (a group of valuable objects that is sometimes purposely buried underground) of 100 silver items. According to Live Science , the treasure is called the Gaulcross hoard. The artifacts belonged to the Pict people who lived in Scotland before, during, and after the Roman era.

Silver plaque from the Norrie's Law hoard (7th-century Pictish silver hoard), Fife, with double disc and Z-rod symbol. (

CC BY SA 3.0

)The artifacts were found by a team led by Gordon Noble, head of archaeology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. When they started work in the field, they didn't think to search for more artifacts, but were trying to learn more about the context of the discovery made nearly two centuries ago. The researchers claim that the field also contained two man-made stone circles - one dating to the Neolithic period and the other the Bronze Age (1670 – 1500 BC).

Silver plaque from the Norrie's Law hoard (7th-century Pictish silver hoard), Fife, with double disc and Z-rod symbol. (

CC BY SA 3.0

)The artifacts were found by a team led by Gordon Noble, head of archaeology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. When they started work in the field, they didn't think to search for more artifacts, but were trying to learn more about the context of the discovery made nearly two centuries ago. The researchers claim that the field also contained two man-made stone circles - one dating to the Neolithic period and the other the Bronze Age (1670 – 1500 BC). The three previously discovered pieces were given to Banff Museum in Aberdeenshire, and are now on loan and display at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.

The surviving objects from the nineteenth-century Gaulcross hoard find. (

National Museums Scotland

)In 2013, two groups of researchers studied the field in northeastern Scotland with the help of metal detectors. It was the first time when researchers explored the field after such a long time. During the second day of work, they uncovered three Late-Roman-era silver "siliquae," or coins, that dated to the 4th or 5th century AD.

The surviving objects from the nineteenth-century Gaulcross hoard find. (

National Museums Scotland

)In 2013, two groups of researchers studied the field in northeastern Scotland with the help of metal detectors. It was the first time when researchers explored the field after such a long time. During the second day of work, they uncovered three Late-Roman-era silver "siliquae," or coins, that dated to the 4th or 5th century AD. They also found a part of a silver bracelet, silver strap-end, and several pieces of folded hacksilver (pieces of cut or bent silver). They examined the field over the next 18 months, and as a result, they unearthed 100 pieces of silver all together.

3,000-year-old broken weapons found in Scotland loch reveal ancient ritual offerings to gods The Missing Pieces: Unraveling the history of the Lewis Chessmen The silver was not mined in Scotland during the Roman period, and instead came from somewhere else in the Roman world. During the '' Late Roman period, silver was recycled and recast into high-status objects that underpinned the development of elite society in the post-Roman period''. The researchers believe that some of these silver pieces, such as the chunks of silver called ingots, may have served as currency, much as a gold bar did in more modern times.

The recent discoveries help shed light on the date of the Gaulcross hoard. It seems that some of the objects were connected with the elites. The silver hand pins and bracelets are very rare finds, so the researchers concluded that the objects would have belonged to some of the most powerful members of the post-Roman society.

Some of the finds from Gaulcross: A) the lunate/crescent-shaped pendant with two double-loops; B) silver hemispheres; C) a small, zoomorphic penannular brooch; D) one of the bracelet fragments with a Late Roman siliquae pinched inside (

National Museums Scotland

)Another important hoard has previously been uncovered in Scotland. Actually, on October 13, 2014, April Holloway of Ancient Origins reported on the discovery of one of the most significant Viking hoards found there to date. She wrote:

Some of the finds from Gaulcross: A) the lunate/crescent-shaped pendant with two double-loops; B) silver hemispheres; C) a small, zoomorphic penannular brooch; D) one of the bracelet fragments with a Late Roman siliquae pinched inside (

National Museums Scotland

)Another important hoard has previously been uncovered in Scotland. Actually, on October 13, 2014, April Holloway of Ancient Origins reported on the discovery of one of the most significant Viking hoards found there to date. She wrote: ''An amateur treasure hunter equipped with a metal detector has unearthed a massive hoard of Viking artifacts in Dumfries and Galloway, in what has been described as one of the most significant archaeological finds in Scottish history. According to the Herald Scotland , more than 100 Viking relics were found, including silver ingots, armbands, brooches, and gold objects.”Treasure hunter uncovers one of the most significant Viking hoards ever found in Scotland Treasures Found Within Very Valuable Viking Hoard Finally Revealed The findings also included “an early Christian cross from the 9th or 10 century AD made from solid silver, described as having unique and unusual decorations. There was also a rare Carolingian vessel, believed to be the largest Carolingian pot ever discovered.”

[image error]Detail of the Carolingian vessel of the famous Viking hoard. (

Historic Environment Scotland

)Holloway wrote that the Vikings “conducted numerous raids on Carolingian lands between 8th and 10th century AD” and explained that in a “few records, the Vikings are thought to have led their first raids in Scotland on the island of Iona in 794.”

[image error]Detail of the Carolingian vessel of the famous Viking hoard. (

Historic Environment Scotland

)Holloway wrote that the Vikings “conducted numerous raids on Carolingian lands between 8th and 10th century AD” and explained that in a “few records, the Vikings are thought to have led their first raids in Scotland on the island of Iona in 794.” The Vikings attacks led to the downfall of the Picts. As Holloway reported:

“In 839, a large Norse fleet invaded via the River Tay and River Earn, both of which were highly navigable, and reached into the heart of the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu. They defeated the king of the Picts, and the king of the Scots of Dál Riata, along with many members of the Pictish aristocracy in battle. The sophisticated kingdom that had been built fell apart, as did the Pictish leadership.''

The Aberlemno Serpent Stone, Class I Pictish stone with Pictish symbols, showing (top to bottom) the serpent, the double disc and Z-rod and the mirror and comb. (Catfish Jim and the soapdish/

CC BY SA 3.0

)Top Image: The Gaulcross silver hoard, including a silver ingot, Hacksilber and folded bracelets. Source:

National Museums Scotland

The Aberlemno Serpent Stone, Class I Pictish stone with Pictish symbols, showing (top to bottom) the serpent, the double disc and Z-rod and the mirror and comb. (Catfish Jim and the soapdish/

CC BY SA 3.0

)Top Image: The Gaulcross silver hoard, including a silver ingot, Hacksilber and folded bracelets. Source:

National Museums Scotland

By Natalia Klimzcak

Published on June 23, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - The Battle of Bannockburn

June 23

1314 The Battle of Bannockburn. This significant battle helped the Scots regain independence from England and secured the throne of Scotland for Robert the Bruce.

1314 The Battle of Bannockburn. This significant battle helped the Scots regain independence from England and secured the throne of Scotland for Robert the Bruce.

Published on June 23, 2016 02:00

June 22, 2016

Pig-chickens, beavers’ tails and turtle soup: 8 weird foods through history

History Extra

A Plantagenet king of England dining. (Credit: Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

From the Romans to the Normans, through the medieval period and up to the reign of Elizabeth I, our foods were influenced by European trends, and heavily affected by the seasons. In the 17th century, glasshouse technology [the use of glass to control temperature and humidity for the cultivation or protection of plants] enabled the rich to buck the seasons, and products from the New World began to be imported. The rich could choose to eat almost anything they fancied, and the range of animals and birds consumed in Georgian Britain was astounding – nothing that moved was safe from the cooking pot.

With that in mind, here is a selection of foods from history at which we might balk today…

1) DormiceYes, the Romans really did eat dormice. At least, some people did, but we don’t really know how many, or how popular dormice were. The dormice the Romans ate weren’t the tiny, huge-eyed things we are familiar with today, but a much larger type called – unsurprisingly – the edible dormouse. They are common across the Mediterranean and most of Western Europe, and there’s a British colony around Tring in the Chilterns – they escaped from a Victorian gentleman’s menagerie and have procreated there ever since.

The Romans would capture the mice and fatten them for the table, much in the same way turkeys are fattened up for Christmas today. They would either keep them in pens or in large jars studded with airholes and feed them walnuts, chestnuts and acorns. They were then either roasted with honey or stuffed with pine nuts, pork and spices and baked – this was a fiddly job.

As with so many of the dishes eaten by the rich in history, the show-off factor lay, not in consuming vast quantities of meat or food in general, but by taking something apparently pointless to eat, and making it delicious. Lavishing time and expense on something so small showed that the person serving it had the money to find, keep, and prepare the mice, as well as the good taste to showcase a delicate titbit instead of a gargantuan mountain of flesh.

2) Cockentryce The rich in medieval England would have eaten a wide variety of animals and birds, usually served intact, with heads, feet and tails all indicating what the meat was, and adding to its visual appeal. A decapitated roast bird would probably have seemed as strange to the average 15th-century knight as one with its head intact to us today.

Medieval feasts could comprise tens of different dishes, roughly grouped together into courses that could be interspersed with entertainment, including amazing edible concoctions. Sotelties, as they were called, were often sugar work, but there was another type of extravagant medieval culinary diversion: fantastic beasts.

The cockentryce is probably the best known of these, and comprised half a pig sewn to half of a capon (a castrated and fattened chicken). Modern recreations often involve the front of the bird and back of the pig, but both were done. Once sewn and stuffed, it was roasted and covered with batter. It was almost certainly then decorated richly with anything the inventive medieval cook could lay his (and professional medieval cooks were always men) hands on.

There are also recipes in medieval manuscripts for capons [a castrated domestic cock] riding suckling pig steeds, and ‘yrchouns’ (hedgehogs) made of pigs’ stomachs stuffed with spiced pork, with almonds to resemble spines. Again, these dishes would have been time-consuming to make and required a lot of skill (and space).

3) Beavers’ tails Until the Reformation in 1533, many of England’s eating habits were dictated by the rules laid down by the Catholic Church. For Catholics in the Middle Ages – that is, most of western Europe – around half of the year was set aside as fast days. This included, as we might imagine, Lent, but it also included Advent, along with Fridays, Wednesdays and various other days.

Fast days didn’t simply mean no eating – it meant no animal products. Fish was acceptable, however, and some exquisite fish recipes were served on fast days. However, there also developed some extremely broad definitions of fish, with beavers’ tails among them. They were scaly, often in the water, and the flesh was also said to taste like fish.

An antique print of a beaver from the illustrated book The Natural History of Animals, 1859. (Credit: Graphica Artis/Getty Images)

4) Tansy Common garden plants such as scabious [aka the butterfly blue or the pincushion flower], comfrey [a popular herb], hawthorn [a shrub] and tansy [a plant with yellow, button-like flowers] were all eaten in previous centuries, both for their taste and their perceived medicinal value.

Tansy, which is today usually seen as an invasive weed, was in the 17th century used as an insect repellent and as a ‘strewing herb’ to freshen the air in musty rooms. If you smell the crushed leaf, you can see why: it is a bitter herb with a very distinctive smell.

In the 17th century it was popular to add flavour to a set of dishes called ‘tansies’, which were usually either a sort of baked sweet omelette, a boiled or baked biscuit, or bread-based pudding. Spinach juice was also often added, to give the final dish a green tinge – something we’d probably find very off-putting today.

Tansy is mildly toxic, or can be (the same applies to comfrey), and too much of it can add an eye-watering flavour to the final dish. Tansy was also said to aid the digestion of salt fish.

5) AmbergrisA solid, waxy, dull grey substance produced in the digestive system of sperm whales, ambergris only reaches the table after it’s been either vomited or excreted out. It then has to survive months or even years in the sea, before being washed up on shore or recovered by a lucky passing boat.

Ambergris has a delicate, musky flavour, and is incredibly scarce. Like most rare and relatively tasty, edible products, it gained a reputation as an aphrodisiac and a much-sought-after food for the super-rich in the 17th century. Charles II was said to enjoy ambergris with eggs, and it was used to flavour pies and cakes.

Ambergris is largely banned today, as part of attempts to curb the exploitation of whales for human consumption. Where it is sold, it commands extortionate prices.

6) Mock turtle soupTurtle soup became popular in Britain in the 18th century. Most recipes start with instructions on how to kill and butcher the turtle, which would have been brought in live from the West Indies. The most elaborate way to serve it was as calipash and calipee: two soups, served in the upper and lower shell, one with the upper (green) and the other with the lower (yellow) meat. It was popular for banquets, and became something of a craze in late Georgian Britain. It was incredibly time-consuming and expensive to prepare, and by the 19th century tinned or dried turtle was often used instead.

Another 19th-century alternative was the peculiarly British mock turtle soup, which used a calf’s head. The character of the mock turtle in Alice in Wonderland, which has the body of a turtle and the head of a calf, sums this up nicely.

It was an ingenious substitute for turtle – affordable, available, and not dissimilar in flavour – and was typical of the way in which British cookery book writers at the time democratised haute cuisine. By the end of the 19th century, mock turtle soup was so closely associated with the upper and middle classes that French cooks called it turtle soup ‘à l’anglaise’.

A close-up of a tin of Heinz ready-to-serve mock turtle soup in 1961. (Credit: Chaloner Woods/Getty Images)

7) MedlarsThe range of fruit and vegetables we eat today is tiny compared to that available at various times in the past. The Victorians, especially, were avid plant-breeders. There were around 1,500 varieties of apples alone available to the late Victorian gardener – compare that to the five or so commonly on sale in shops today. The Victorians were also more adventurous when it came to fruit – much of which would be unsellable in the modern world.

Medlars, which are related to the rose and the apple, were known to the Greeks and Romans, but were really exploited by the Victorians. The fruit is small, brown, and open at the bottom – the French call it cul de chien, or ‘dog’s bottom fruit’. It’s rock hard and inedible unless it’s left to ‘blet’, or partially rot, either on the tree or in bran. The Victorians would serve them in the bran and scrape out the flesh to eat with sugar and cream. They would also make tarts and fruit cheese with it.

You can still buy medlar jelly and it is exquisite.

8) Vegetarian hamVegetarianism has a long history, though the word itself is comparatively new. Early vegetarians were called pythagoreans, after the Greek mathematician Pythagoras (b 571 BC).

Until the 19th century, giving up meat voluntarily was largely associated with religious belief. It was often said by non-meat eaters that those who ate meat ingested with it notions of slaughter and blood-letting, and that meat-eating contributed to wars and violence. For some, giving up meat was a form of protest against societal norms, which valued meat eating as prestigious and as a mark of the ruling elite.

In the late 19th century, vegetarianism finally became a movement, associated closely with animal welfare. Its proponents were often women and, for that reason, it became associated for a while with suffrage. Vegetarian restaurants opened to cater for the growing numbers of non-meat eaters, and provided a safe haven for women wishing to meet in socially acceptable surroundings.

There was in the Victorian period a leap forward in developing vegetarian food, which was delicious and creative in its own right, and not merely a collection of side dishes or meat-based dishes with the meat removed. Furthermore, those who ate them were proud to show their adherence to a vegetarian diet.

To Victorians, our modern ideas of making protein into something that looks and tries to taste like meat would probably seem decidedly weird.

Dr Annie Gray is a research associate at the University of York and a freelance food history consultant.

A Plantagenet king of England dining. (Credit: Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

From the Romans to the Normans, through the medieval period and up to the reign of Elizabeth I, our foods were influenced by European trends, and heavily affected by the seasons. In the 17th century, glasshouse technology [the use of glass to control temperature and humidity for the cultivation or protection of plants] enabled the rich to buck the seasons, and products from the New World began to be imported. The rich could choose to eat almost anything they fancied, and the range of animals and birds consumed in Georgian Britain was astounding – nothing that moved was safe from the cooking pot.

With that in mind, here is a selection of foods from history at which we might balk today…

1) DormiceYes, the Romans really did eat dormice. At least, some people did, but we don’t really know how many, or how popular dormice were. The dormice the Romans ate weren’t the tiny, huge-eyed things we are familiar with today, but a much larger type called – unsurprisingly – the edible dormouse. They are common across the Mediterranean and most of Western Europe, and there’s a British colony around Tring in the Chilterns – they escaped from a Victorian gentleman’s menagerie and have procreated there ever since.

The Romans would capture the mice and fatten them for the table, much in the same way turkeys are fattened up for Christmas today. They would either keep them in pens or in large jars studded with airholes and feed them walnuts, chestnuts and acorns. They were then either roasted with honey or stuffed with pine nuts, pork and spices and baked – this was a fiddly job.

As with so many of the dishes eaten by the rich in history, the show-off factor lay, not in consuming vast quantities of meat or food in general, but by taking something apparently pointless to eat, and making it delicious. Lavishing time and expense on something so small showed that the person serving it had the money to find, keep, and prepare the mice, as well as the good taste to showcase a delicate titbit instead of a gargantuan mountain of flesh.

2) Cockentryce The rich in medieval England would have eaten a wide variety of animals and birds, usually served intact, with heads, feet and tails all indicating what the meat was, and adding to its visual appeal. A decapitated roast bird would probably have seemed as strange to the average 15th-century knight as one with its head intact to us today.

Medieval feasts could comprise tens of different dishes, roughly grouped together into courses that could be interspersed with entertainment, including amazing edible concoctions. Sotelties, as they were called, were often sugar work, but there was another type of extravagant medieval culinary diversion: fantastic beasts.

The cockentryce is probably the best known of these, and comprised half a pig sewn to half of a capon (a castrated and fattened chicken). Modern recreations often involve the front of the bird and back of the pig, but both were done. Once sewn and stuffed, it was roasted and covered with batter. It was almost certainly then decorated richly with anything the inventive medieval cook could lay his (and professional medieval cooks were always men) hands on.

There are also recipes in medieval manuscripts for capons [a castrated domestic cock] riding suckling pig steeds, and ‘yrchouns’ (hedgehogs) made of pigs’ stomachs stuffed with spiced pork, with almonds to resemble spines. Again, these dishes would have been time-consuming to make and required a lot of skill (and space).

3) Beavers’ tails Until the Reformation in 1533, many of England’s eating habits were dictated by the rules laid down by the Catholic Church. For Catholics in the Middle Ages – that is, most of western Europe – around half of the year was set aside as fast days. This included, as we might imagine, Lent, but it also included Advent, along with Fridays, Wednesdays and various other days.

Fast days didn’t simply mean no eating – it meant no animal products. Fish was acceptable, however, and some exquisite fish recipes were served on fast days. However, there also developed some extremely broad definitions of fish, with beavers’ tails among them. They were scaly, often in the water, and the flesh was also said to taste like fish.

An antique print of a beaver from the illustrated book The Natural History of Animals, 1859. (Credit: Graphica Artis/Getty Images)

4) Tansy Common garden plants such as scabious [aka the butterfly blue or the pincushion flower], comfrey [a popular herb], hawthorn [a shrub] and tansy [a plant with yellow, button-like flowers] were all eaten in previous centuries, both for their taste and their perceived medicinal value.

Tansy, which is today usually seen as an invasive weed, was in the 17th century used as an insect repellent and as a ‘strewing herb’ to freshen the air in musty rooms. If you smell the crushed leaf, you can see why: it is a bitter herb with a very distinctive smell.

In the 17th century it was popular to add flavour to a set of dishes called ‘tansies’, which were usually either a sort of baked sweet omelette, a boiled or baked biscuit, or bread-based pudding. Spinach juice was also often added, to give the final dish a green tinge – something we’d probably find very off-putting today.

Tansy is mildly toxic, or can be (the same applies to comfrey), and too much of it can add an eye-watering flavour to the final dish. Tansy was also said to aid the digestion of salt fish.

5) AmbergrisA solid, waxy, dull grey substance produced in the digestive system of sperm whales, ambergris only reaches the table after it’s been either vomited or excreted out. It then has to survive months or even years in the sea, before being washed up on shore or recovered by a lucky passing boat.

Ambergris has a delicate, musky flavour, and is incredibly scarce. Like most rare and relatively tasty, edible products, it gained a reputation as an aphrodisiac and a much-sought-after food for the super-rich in the 17th century. Charles II was said to enjoy ambergris with eggs, and it was used to flavour pies and cakes.

Ambergris is largely banned today, as part of attempts to curb the exploitation of whales for human consumption. Where it is sold, it commands extortionate prices.

6) Mock turtle soupTurtle soup became popular in Britain in the 18th century. Most recipes start with instructions on how to kill and butcher the turtle, which would have been brought in live from the West Indies. The most elaborate way to serve it was as calipash and calipee: two soups, served in the upper and lower shell, one with the upper (green) and the other with the lower (yellow) meat. It was popular for banquets, and became something of a craze in late Georgian Britain. It was incredibly time-consuming and expensive to prepare, and by the 19th century tinned or dried turtle was often used instead.

Another 19th-century alternative was the peculiarly British mock turtle soup, which used a calf’s head. The character of the mock turtle in Alice in Wonderland, which has the body of a turtle and the head of a calf, sums this up nicely.

It was an ingenious substitute for turtle – affordable, available, and not dissimilar in flavour – and was typical of the way in which British cookery book writers at the time democratised haute cuisine. By the end of the 19th century, mock turtle soup was so closely associated with the upper and middle classes that French cooks called it turtle soup ‘à l’anglaise’.

A close-up of a tin of Heinz ready-to-serve mock turtle soup in 1961. (Credit: Chaloner Woods/Getty Images)

7) MedlarsThe range of fruit and vegetables we eat today is tiny compared to that available at various times in the past. The Victorians, especially, were avid plant-breeders. There were around 1,500 varieties of apples alone available to the late Victorian gardener – compare that to the five or so commonly on sale in shops today. The Victorians were also more adventurous when it came to fruit – much of which would be unsellable in the modern world.

Medlars, which are related to the rose and the apple, were known to the Greeks and Romans, but were really exploited by the Victorians. The fruit is small, brown, and open at the bottom – the French call it cul de chien, or ‘dog’s bottom fruit’. It’s rock hard and inedible unless it’s left to ‘blet’, or partially rot, either on the tree or in bran. The Victorians would serve them in the bran and scrape out the flesh to eat with sugar and cream. They would also make tarts and fruit cheese with it.

You can still buy medlar jelly and it is exquisite.

8) Vegetarian hamVegetarianism has a long history, though the word itself is comparatively new. Early vegetarians were called pythagoreans, after the Greek mathematician Pythagoras (b 571 BC).

Until the 19th century, giving up meat voluntarily was largely associated with religious belief. It was often said by non-meat eaters that those who ate meat ingested with it notions of slaughter and blood-letting, and that meat-eating contributed to wars and violence. For some, giving up meat was a form of protest against societal norms, which valued meat eating as prestigious and as a mark of the ruling elite.

In the late 19th century, vegetarianism finally became a movement, associated closely with animal welfare. Its proponents were often women and, for that reason, it became associated for a while with suffrage. Vegetarian restaurants opened to cater for the growing numbers of non-meat eaters, and provided a safe haven for women wishing to meet in socially acceptable surroundings.

There was in the Victorian period a leap forward in developing vegetarian food, which was delicious and creative in its own right, and not merely a collection of side dishes or meat-based dishes with the meat removed. Furthermore, those who ate them were proud to show their adherence to a vegetarian diet.

To Victorians, our modern ideas of making protein into something that looks and tries to taste like meat would probably seem decidedly weird.

Dr Annie Gray is a research associate at the University of York and a freelance food history consultant.

Published on June 22, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Battle of Pydna

June 22

168 BC Battle of Pydna: Romans under Lucius Aemilius Paullus defeated and captured Macedonian King Perseus ending the Third Macedonian War.

168 BC Battle of Pydna: Romans under Lucius Aemilius Paullus defeated and captured Macedonian King Perseus ending the Third Macedonian War.

Published on June 22, 2016 02:00

June 21, 2016

More than a Dozen Mysterious Prehistoric Tunnels in Cornwall, England, Mystify Researchers

Ancient Origins

More than a dozen tunnels have been found in Cornwall, England, that are unique in the British Isles. No one knows why Iron Age people created them. The fact that the ancients supported their tops and sides with stone, suggests that they wanted them to endure, and that they have, for about 2,400 years.

Many of the fogous, as they’re called in Cornish after their word for cave, ogo, were excavated by antiquarians who didn’t keep records, so their purpose is hard to fathom, says a BBC Travel story on the mysterious structures.

The landscape of Cornwall is covered with hundreds of ancient, stone, man-made features, including enclosures, cliff castles, roundhouses, ramparts and forts. In terms of stone monuments, the Cornwall countryside has barrows, menhirs, dolmens, cairns and of course stone circles. In addition, there are 13 inscribed stones.

The Cornish landscape is dotted with ancient megalithic structures like this Lanyon Quoit Megalith (

public domain

)“Obviously, all of this monument building did not take place at the same time. Man has been leaving his mark on the surface of the planet for thousands of years and each civilisation has had its own method of honouring their dead and/or their deities,” says the site Cornwall in Focus.

The Cornish landscape is dotted with ancient megalithic structures like this Lanyon Quoit Megalith (

public domain

)“Obviously, all of this monument building did not take place at the same time. Man has been leaving his mark on the surface of the planet for thousands of years and each civilisation has had its own method of honouring their dead and/or their deities,” says the site Cornwall in Focus.

The site says Cornwall has 74 Bronze Age structures, 80 from the Iron Age, 55 from the Neolithic and one from the Mesolithic. In addition, there are nine Roman sites and 24 post-Roman. The Mesolithic dates from 8000 to 4500 BC, so people have been occupying this southwestern peninsula of Britain for a long, long time.

About 150 generations of people worked the land there. But it’s believed the fogous date to the Iron Age, which lasted from about 700 BC to 43 AD. Though they’re unique, the fogou tunnels of Cornwall are similar to souterrains in Scotland, Ireland, Normandy and Brittany, says the BBC.

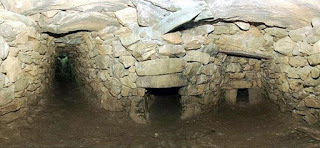

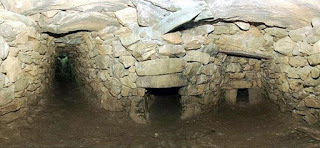

Carn Euny fogou in Cornwall (

public domain

)The fogous required considerable investment of time and resources “and no one knows why they would have done so,” says the BBC. It’s interesting to note that all 14 of the fogous have been found within the confines of prehistoric settlements.

Carn Euny fogou in Cornwall (

public domain

)The fogous required considerable investment of time and resources “and no one knows why they would have done so,” says the BBC. It’s interesting to note that all 14 of the fogous have been found within the confines of prehistoric settlements.

Because the society was preliterate, there are no written records that explain the enigmatic structures.

“There are only a couple that have been excavated in modern times – and they don’t seem to be structures that really easily give up their secrets,” Susan Greaney, head properties historian of English Heritage, told the BBC.

The mystery of their construction is amplified at Halliggye Fogou, the best-preserved such tunnel in Cornwall. It measures 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) high. The 8.4 -meter-long (27.6 feet) passage narrows at its end in a tunnel 4 meters (13.124 feet) long and .75 meter (2.46 feet) tall.

Main chamber of the Halliggye Fogou (

public domain

)Another tunnel 27 meters (88.6 feet) long branches off to the left of the main chamber and gets darker the farther in one goes. There is what the BBC calls a “final creep” at the end of this passage that has stone lip upon which one could trip.

Main chamber of the Halliggye Fogou (

public domain

)Another tunnel 27 meters (88.6 feet) long branches off to the left of the main chamber and gets darker the farther in one goes. There is what the BBC calls a “final creep” at the end of this passage that has stone lip upon which one could trip.

“In other words, none of it seemed designed for easy access – a characteristic that’s as emblematic of fogous as it is perplexing,” wrote the BBC’s Amanda Ruggeri.

Halliggye Fogou. One of the largest and best preserved of these fogou (curious underground passages) this one originally passed under the rampart of a defended Iron Age settlement. (

geograph.org.uk

)Some have speculated they were places to hide, though the lintels of many of them are visible on the surface and Ruggeri says they would be forbidding places to stay if one sought refuge.

Halliggye Fogou. One of the largest and best preserved of these fogou (curious underground passages) this one originally passed under the rampart of a defended Iron Age settlement. (

geograph.org.uk

)Some have speculated they were places to hide, though the lintels of many of them are visible on the surface and Ruggeri says they would be forbidding places to stay if one sought refuge.

Still others have speculated they were burial chambers. An antiquarian who entered Halliggye in 1803 wrote that it had funerary urns. But others entered by the hole he made in the roof, and all the urns are gone. No bones or ashes have been discovered in the six tunnels that modern archaeologists have examined. No remnants of grains have been found, perhaps because the soil is acidic. No ingots from mining have been discovered.

This elimination of storage, mining or burial purposes has led some to speculate that they were perhaps ceremonial or religious structures where people worshiped gods.

Top image: The Halliggye Fogou ( megalithics.com )

By Mark Miller

More than a dozen tunnels have been found in Cornwall, England, that are unique in the British Isles. No one knows why Iron Age people created them. The fact that the ancients supported their tops and sides with stone, suggests that they wanted them to endure, and that they have, for about 2,400 years.

Many of the fogous, as they’re called in Cornish after their word for cave, ogo, were excavated by antiquarians who didn’t keep records, so their purpose is hard to fathom, says a BBC Travel story on the mysterious structures.

The landscape of Cornwall is covered with hundreds of ancient, stone, man-made features, including enclosures, cliff castles, roundhouses, ramparts and forts. In terms of stone monuments, the Cornwall countryside has barrows, menhirs, dolmens, cairns and of course stone circles. In addition, there are 13 inscribed stones.

The Cornish landscape is dotted with ancient megalithic structures like this Lanyon Quoit Megalith (

public domain

)“Obviously, all of this monument building did not take place at the same time. Man has been leaving his mark on the surface of the planet for thousands of years and each civilisation has had its own method of honouring their dead and/or their deities,” says the site Cornwall in Focus.

The Cornish landscape is dotted with ancient megalithic structures like this Lanyon Quoit Megalith (

public domain

)“Obviously, all of this monument building did not take place at the same time. Man has been leaving his mark on the surface of the planet for thousands of years and each civilisation has had its own method of honouring their dead and/or their deities,” says the site Cornwall in Focus. The site says Cornwall has 74 Bronze Age structures, 80 from the Iron Age, 55 from the Neolithic and one from the Mesolithic. In addition, there are nine Roman sites and 24 post-Roman. The Mesolithic dates from 8000 to 4500 BC, so people have been occupying this southwestern peninsula of Britain for a long, long time.

About 150 generations of people worked the land there. But it’s believed the fogous date to the Iron Age, which lasted from about 700 BC to 43 AD. Though they’re unique, the fogou tunnels of Cornwall are similar to souterrains in Scotland, Ireland, Normandy and Brittany, says the BBC.

Carn Euny fogou in Cornwall (

public domain

)The fogous required considerable investment of time and resources “and no one knows why they would have done so,” says the BBC. It’s interesting to note that all 14 of the fogous have been found within the confines of prehistoric settlements.

Carn Euny fogou in Cornwall (

public domain

)The fogous required considerable investment of time and resources “and no one knows why they would have done so,” says the BBC. It’s interesting to note that all 14 of the fogous have been found within the confines of prehistoric settlements.Because the society was preliterate, there are no written records that explain the enigmatic structures.

“There are only a couple that have been excavated in modern times – and they don’t seem to be structures that really easily give up their secrets,” Susan Greaney, head properties historian of English Heritage, told the BBC.

The mystery of their construction is amplified at Halliggye Fogou, the best-preserved such tunnel in Cornwall. It measures 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) high. The 8.4 -meter-long (27.6 feet) passage narrows at its end in a tunnel 4 meters (13.124 feet) long and .75 meter (2.46 feet) tall.

Main chamber of the Halliggye Fogou (

public domain

)Another tunnel 27 meters (88.6 feet) long branches off to the left of the main chamber and gets darker the farther in one goes. There is what the BBC calls a “final creep” at the end of this passage that has stone lip upon which one could trip.

Main chamber of the Halliggye Fogou (

public domain

)Another tunnel 27 meters (88.6 feet) long branches off to the left of the main chamber and gets darker the farther in one goes. There is what the BBC calls a “final creep” at the end of this passage that has stone lip upon which one could trip.“In other words, none of it seemed designed for easy access – a characteristic that’s as emblematic of fogous as it is perplexing,” wrote the BBC’s Amanda Ruggeri.

Halliggye Fogou. One of the largest and best preserved of these fogou (curious underground passages) this one originally passed under the rampart of a defended Iron Age settlement. (

geograph.org.uk

)Some have speculated they were places to hide, though the lintels of many of them are visible on the surface and Ruggeri says they would be forbidding places to stay if one sought refuge.

Halliggye Fogou. One of the largest and best preserved of these fogou (curious underground passages) this one originally passed under the rampart of a defended Iron Age settlement. (

geograph.org.uk

)Some have speculated they were places to hide, though the lintels of many of them are visible on the surface and Ruggeri says they would be forbidding places to stay if one sought refuge.Still others have speculated they were burial chambers. An antiquarian who entered Halliggye in 1803 wrote that it had funerary urns. But others entered by the hole he made in the roof, and all the urns are gone. No bones or ashes have been discovered in the six tunnels that modern archaeologists have examined. No remnants of grains have been found, perhaps because the soil is acidic. No ingots from mining have been discovered.

This elimination of storage, mining or burial purposes has led some to speculate that they were perhaps ceremonial or religious structures where people worshiped gods.

“These were lost religions,” said archaeologist James Gossip, who led Ruggeri on a tour of Halligye fogou. “We don’t know what people were worshiping. There’s no reason they couldn’t have had a ceremonial, spiritual purpose as well as, say, storage.”He added that the purpose and use of the fogous probably changed over the hundreds of years they were in use.

Top image: The Halliggye Fogou ( megalithics.com )

By Mark Miller

Published on June 21, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - battle at Lake Trasimenus

June 21

217 BC Carthaginian forces led by Hannibal destroyed a Roman army under Consul Gaius Flaminicy in a battle at Lake Trasimenus in central Italy.

217 BC Carthaginian forces led by Hannibal destroyed a Roman army under Consul Gaius Flaminicy in a battle at Lake Trasimenus in central Italy.

Published on June 21, 2016 02:00