MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 76

November 13, 2016

Mein Tanz mit Rommel - Elisabeth Marrion

Buchverlosung zu "Mein Tanz mit Rommel" von Elisabeth Marrion

German edition of the historical novel, The Night I Danced with Rommel is based upon Elisabeth Marrion's family history.

Worum geht es in dem Buch: Lesen sie doch die Synopsis

Deutschland in den Jahren von 1926 bis 1945: Ihre Kindheit, geprägt von den Nachwehen des Ersten Weltkriegs, verbringt Hilde im beschaulichen Tilsit. Mit vierzehn Jahren muss sie sich alleine aufmachen in die weite Welt – nach Berlin – und kämpft fortan um das eigene Überleben und das ihrer Familie. Elisabeth Marrion, in Hildesheim geboren, zeichnet das Schicksal ihrer Mutter in diesem Tatsachenroman ergreifend nach. Der Leser erfährt, wie Hilde von einem schüchternen jungen Mädchen zu einer couragierten Frau heranwächst – und wie ein Tanz mit Generalfeldmarschall Rommel, dem „Wüstenfuchs“, der jungen Frau und ihrer Familie neue Hoffnung schenkt. Ein aufrüttelndes Zeugnis über Liebe, Freundschaft und Leid.

Wir verlosen 5 Buecher bei Lovelybooks.de Verlosung ends November Lovely Books Link

Hello lieber Leser - Leserinnen, meine familie wollte eigentlich nicht das ich dieses Buch ( das erste eine Triology ) schreibe. Hier im ersten Buch geht es hauptsaechlich um meine Mutter. Ihre Jugend und Leben und um Freundschaft, Liebe, Mut und Verlusst. Ich schreibe meine Buecher in englisch und es dauert immer eine Weile bis sie mit hilfe meiner Freunden uebersetzt sind. Aber das zweite uebersetzte Buch geht schon diese Woche an meinen wuderbaren Verleger in Hannover. Dann dauert es nicht mehr lange.

Aber zurueck auf 'Mein Tanz mit Rommel' Es beruht sich auf Wahrheit und ist so wie es meine Mutter mir erzaehlt hat.

Ich wuerde mich ueber Fragen sehr freuen

Auf Deutsch erhaeltlich bei Amazon DE link

Amazon US link

Amazon UK link

German edition of the historical novel, The Night I Danced with Rommel is based upon Elisabeth Marrion's family history.

Worum geht es in dem Buch: Lesen sie doch die Synopsis

Deutschland in den Jahren von 1926 bis 1945: Ihre Kindheit, geprägt von den Nachwehen des Ersten Weltkriegs, verbringt Hilde im beschaulichen Tilsit. Mit vierzehn Jahren muss sie sich alleine aufmachen in die weite Welt – nach Berlin – und kämpft fortan um das eigene Überleben und das ihrer Familie. Elisabeth Marrion, in Hildesheim geboren, zeichnet das Schicksal ihrer Mutter in diesem Tatsachenroman ergreifend nach. Der Leser erfährt, wie Hilde von einem schüchternen jungen Mädchen zu einer couragierten Frau heranwächst – und wie ein Tanz mit Generalfeldmarschall Rommel, dem „Wüstenfuchs“, der jungen Frau und ihrer Familie neue Hoffnung schenkt. Ein aufrüttelndes Zeugnis über Liebe, Freundschaft und Leid.

Wir verlosen 5 Buecher bei Lovelybooks.de Verlosung ends November Lovely Books Link

Hello lieber Leser - Leserinnen, meine familie wollte eigentlich nicht das ich dieses Buch ( das erste eine Triology ) schreibe. Hier im ersten Buch geht es hauptsaechlich um meine Mutter. Ihre Jugend und Leben und um Freundschaft, Liebe, Mut und Verlusst. Ich schreibe meine Buecher in englisch und es dauert immer eine Weile bis sie mit hilfe meiner Freunden uebersetzt sind. Aber das zweite uebersetzte Buch geht schon diese Woche an meinen wuderbaren Verleger in Hannover. Dann dauert es nicht mehr lange.

Aber zurueck auf 'Mein Tanz mit Rommel' Es beruht sich auf Wahrheit und ist so wie es meine Mutter mir erzaehlt hat.

Ich wuerde mich ueber Fragen sehr freuen

Auf Deutsch erhaeltlich bei Amazon DE link

Amazon US link

Amazon UK link

Published on November 13, 2016 15:44

Striking Pictish Dragon Carving Discovered During Storms in Orkney

Ancient Origins

An 8th century carving of a Pictish dragon (also called a Pictish beast) has been discovered on an eroding cliff face in Orkney, Scotland. The stone decoration is one of the most beautiful Pictish artifacts discovered in recent years.

The BBC reports that the stone is a rare find. The carving was created by a Pictish artist. The Picts were especially active in these lands between the 3rd and 8th centuries AD.

Kristy Owen, HES Senior Archaeology Manager, believes that the proper excavation of the stone provides archaeologists with a great opportunity to better understand the site’s development. The discovery may also help researchers understand other stones made by the Picts, and the symbols depicted upon them.

Three carvings of the Pictish dragon: Martin's Stone (Val Vannet/

CC BY SA 2.0

), Maiden Stone (

CC BY SA 3.0

), and Strathmartine Castle stone. (Catfish Jim and the soapdish/

CC BY SA 3.0

)Discussing the discovery, The Archaeology Institute, University of the Highlands and Islands wrote:

Three carvings of the Pictish dragon: Martin's Stone (Val Vannet/

CC BY SA 2.0

), Maiden Stone (

CC BY SA 3.0

), and Strathmartine Castle stone. (Catfish Jim and the soapdish/

CC BY SA 3.0

)Discussing the discovery, The Archaeology Institute, University of the Highlands and Islands wrote:

The discovery was made by archaeologist Dr. Hugo Anderson-Whymark while he was examining the site of the East Mainland coast after it had been hit by a storm. During his explorations, he saw the stone, which had been ''excavated'' by the sea.

The stone discovered at the site. (

UHI Archaeology Institute

)Nick Card, Senior Projects Manager at ORCA told the Scotsman more about the stone’s importance. He said:

The stone discovered at the site. (

UHI Archaeology Institute

)Nick Card, Senior Projects Manager at ORCA told the Scotsman more about the stone’s importance. He said:

Discovery of Pictish Fort Reveals Iron Age Look-Out post for Sea RaidersArchaeologists in Scotland investigate the mystery of the Rhynie Man An illustration of an archaeological "Pictish Beast" symbol from Scotland. (Struthious Bandersnatch/

CC BY SA 1.0

)Researchers find fascinating items related to the Picts every archaeological season. Knowledge about this mysterious culture is also increasing with the intensified work. Another great discovery related to Picts was made this past June. As Natalia Klimczak reported for Ancient Origins:

An illustration of an archaeological "Pictish Beast" symbol from Scotland. (Struthious Bandersnatch/

CC BY SA 1.0

)Researchers find fascinating items related to the Picts every archaeological season. Knowledge about this mysterious culture is also increasing with the intensified work. Another great discovery related to Picts was made this past June. As Natalia Klimczak reported for Ancient Origins:

Archaeologists discovered a hoard of 100 silver items, including coins and jewelry, which come from the 4th and 5th centuries AD. The treasure belongs to the period of the Roman Empire’s domination in Scotland, or perhaps later.

Almost 200 years ago, a team of Scottish laborers cleared a rocky field with dynamite. They discovered three magnificent silver artifacts: a chain, a spiral bangle, and a hand pin. However, they didn't search any deeper to check if there were any more treasures. They turned the field into farmland and excavations were forgotten.

The surviving objects from the nineteenth-century Gaulcross hoard find. (

National Museums Scotland

)Archaeologists returned to the site and discovered a hoard (a group of valuable objects that is sometimes purposely buried underground) of 100 silver items. According to Live Science, the treasure is called the Gaulcross hoard. The artifacts belonged to the Pict people who lived in Scotland before, during, and after the Roman era.

The surviving objects from the nineteenth-century Gaulcross hoard find. (

National Museums Scotland

)Archaeologists returned to the site and discovered a hoard (a group of valuable objects that is sometimes purposely buried underground) of 100 silver items. According to Live Science, the treasure is called the Gaulcross hoard. The artifacts belonged to the Pict people who lived in Scotland before, during, and after the Roman era.

The artifacts were found by a team led by Gordon Noble, head of archaeology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. When they started work in the field, they didn't think to search for more artifacts, but were trying to learn more about the context of the discovery made nearly two centuries ago. The researchers claim that the field also contained two man-made stone circles - one dating to the Neolithic period and the other the Bronze Age (1670 – 1500 BC).

Top Image: The front face of the Pictish Cross Slab. Source: Dr. Hugo Anderson-Whymark

An 8th century carving of a Pictish dragon (also called a Pictish beast) has been discovered on an eroding cliff face in Orkney, Scotland. The stone decoration is one of the most beautiful Pictish artifacts discovered in recent years.

The BBC reports that the stone is a rare find. The carving was created by a Pictish artist. The Picts were especially active in these lands between the 3rd and 8th centuries AD.

Kristy Owen, HES Senior Archaeology Manager, believes that the proper excavation of the stone provides archaeologists with a great opportunity to better understand the site’s development. The discovery may also help researchers understand other stones made by the Picts, and the symbols depicted upon them.

Three carvings of the Pictish dragon: Martin's Stone (Val Vannet/

CC BY SA 2.0

), Maiden Stone (

CC BY SA 3.0

), and Strathmartine Castle stone. (Catfish Jim and the soapdish/

CC BY SA 3.0

)Discussing the discovery, The Archaeology Institute, University of the Highlands and Islands wrote:

Three carvings of the Pictish dragon: Martin's Stone (Val Vannet/

CC BY SA 2.0

), Maiden Stone (

CC BY SA 3.0

), and Strathmartine Castle stone. (Catfish Jim and the soapdish/

CC BY SA 3.0

)Discussing the discovery, The Archaeology Institute, University of the Highlands and Islands wrote:“A dragon motif tantalizingly peered out from the emerging stone slab and pointed to a possible Pictish (3rd-8th centuries AD) origin, but further examination was difficult due to the location. This carved stone was clearly significant and needed to be quickly recovered before the next forecast storms that were due to hit the following weekend.”The Golden Age of the Christian Picts: Evidence for Religious Production at PortmahomackThe Impressive Gaulcross Hoard: 100 Roman-Era Silver Pieces Unearthed in ScotlandPictish Cross Slab, East Mainland, Orkney by Dr Hugo Anderson-Whymark on SketchfabTime was short, but the erosion of the cliff caused by the stormy sea which surrounds Orkney made the archaeological site very dangerous. Nonetheless, the Orkney Research Centre for Archaeology (ORCA), with support from Historic Environment Scotland, completed the difficult mission of recovering the artifact. The archaeologists needed to follow weather changes and track storms while carefully working to extract the unique stone.

The discovery was made by archaeologist Dr. Hugo Anderson-Whymark while he was examining the site of the East Mainland coast after it had been hit by a storm. During his explorations, he saw the stone, which had been ''excavated'' by the sea.

The stone discovered at the site. (

UHI Archaeology Institute

)Nick Card, Senior Projects Manager at ORCA told the Scotsman more about the stone’s importance. He said:

The stone discovered at the site. (

UHI Archaeology Institute

)Nick Card, Senior Projects Manager at ORCA told the Scotsman more about the stone’s importance. He said:“Carved Pictish Cross Slabs are rare across Scotland with only 2 having been discovered in Orkney. This is therefore a significant find and allows us to examine a piece of art from a period when Orkney society was beginning to embrace Christianity. Now that the piece is recorded and removed from site, we can concentrate on conserving the delicate stone carving and perhaps re-evaluate the site itself.”The stone has been removed from the coastline and is currently scheduled for conservation. It may be put on display in the future, but this is uncertain. Archaeologists are seeking funding to re-evaluate the site and they hope that future discoveries will help to fill in the blanks in the history of this artifact.

Discovery of Pictish Fort Reveals Iron Age Look-Out post for Sea RaidersArchaeologists in Scotland investigate the mystery of the Rhynie Man

An illustration of an archaeological "Pictish Beast" symbol from Scotland. (Struthious Bandersnatch/

CC BY SA 1.0

)Researchers find fascinating items related to the Picts every archaeological season. Knowledge about this mysterious culture is also increasing with the intensified work. Another great discovery related to Picts was made this past June. As Natalia Klimczak reported for Ancient Origins:

An illustration of an archaeological "Pictish Beast" symbol from Scotland. (Struthious Bandersnatch/

CC BY SA 1.0

)Researchers find fascinating items related to the Picts every archaeological season. Knowledge about this mysterious culture is also increasing with the intensified work. Another great discovery related to Picts was made this past June. As Natalia Klimczak reported for Ancient Origins:Archaeologists discovered a hoard of 100 silver items, including coins and jewelry, which come from the 4th and 5th centuries AD. The treasure belongs to the period of the Roman Empire’s domination in Scotland, or perhaps later.

Almost 200 years ago, a team of Scottish laborers cleared a rocky field with dynamite. They discovered three magnificent silver artifacts: a chain, a spiral bangle, and a hand pin. However, they didn't search any deeper to check if there were any more treasures. They turned the field into farmland and excavations were forgotten.

The surviving objects from the nineteenth-century Gaulcross hoard find. (

National Museums Scotland

)Archaeologists returned to the site and discovered a hoard (a group of valuable objects that is sometimes purposely buried underground) of 100 silver items. According to Live Science, the treasure is called the Gaulcross hoard. The artifacts belonged to the Pict people who lived in Scotland before, during, and after the Roman era.

The surviving objects from the nineteenth-century Gaulcross hoard find. (

National Museums Scotland

)Archaeologists returned to the site and discovered a hoard (a group of valuable objects that is sometimes purposely buried underground) of 100 silver items. According to Live Science, the treasure is called the Gaulcross hoard. The artifacts belonged to the Pict people who lived in Scotland before, during, and after the Roman era.The artifacts were found by a team led by Gordon Noble, head of archaeology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. When they started work in the field, they didn't think to search for more artifacts, but were trying to learn more about the context of the discovery made nearly two centuries ago. The researchers claim that the field also contained two man-made stone circles - one dating to the Neolithic period and the other the Bronze Age (1670 – 1500 BC).

Top Image: The front face of the Pictish Cross Slab. Source: Dr. Hugo Anderson-Whymark

Published on November 13, 2016 03:00

November 12, 2016

Paleolithic Jewelry: Still Eye-catching After 50,000 Years

Ancient Origins

By Tamara Zubchuk | The Siberian Times

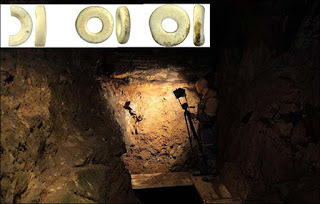

Beads made from ostrich eggs buried in the Siberian cave around 2,000 generations ago reveal amazing artistic (and drilling) skills of our long-ago ancestors.

The fascinating collection of jewelry made of ostrich eggshells is being assembled by archeologists working in the world famous Denisova cave in Altai region. Ostriches in Siberia? 50,000 years ago?

Yes, it seems so. Or, at least, their eggshells made it here somehow.

In a month that has seen disclosures of the fossil of a tropical parrot in Siberia from at least five million years ago in the Miocene era, this elegant Paleolithic chic shows that our deep history (some 2,000 generations ago, give or take) contains many unexpected surprises.

Pictured here are finds from a collection of beads in the Denisova cave, perfectly drilled, and archeologists say they have now found one more close by, with full details to be revealed soon in a scientific journal. They are in no doubt that the beads are between 45,000 and 50,000 years old in the Upper Paleolithic era, making them older than strikingly similar finds 11,500 kilometers away in South Africa.

Beads found inside Denisova Cave in the Altai mountains. Pictures: Maksim KozlikinMaksim Kozlikin, researcher at the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography, Novosibirsk, said of the Siberian ostrich egg beads: 'This is no ordinary find. Our team got quite excited when we found the bead.

Beads found inside Denisova Cave in the Altai mountains. Pictures: Maksim KozlikinMaksim Kozlikin, researcher at the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography, Novosibirsk, said of the Siberian ostrich egg beads: 'This is no ordinary find. Our team got quite excited when we found the bead.

'This is an amazing piece of work. The ostrich egg shell is quite robust material, but the holes in the beads must have been made with a fine stone drill.

Did Neanderthals make jewelry 130,000 years go? Eagle claws provide cluesThe skills and techniques used some 45,000 to 50,000 years ago are remarkable and more akin to the Neolithic era, dozens of millennia later.

He believes the beads may have been sewn into clothing - or formed part of a bracelet or necklace.

The Denisova Cave. Pictures: Vera SalnitskayaThe latest discovery 'is one centimetre in diameter, with a hole inside that is slightly wider than a millimetre,' he said.

The Denisova Cave. Pictures: Vera SalnitskayaThe latest discovery 'is one centimetre in diameter, with a hole inside that is slightly wider than a millimetre,' he said.

Yet he admits: 'As of now, there is much more that we do not know about these beads than we do know. For example, we do not know where the beads were made.

'One version is that the egg shells could have been exported from Trans-Baikal or Mongolia with the beads manufactured here.

'Another possibility is that the beads were purchased elsewhere and delivered to the Altai Mountains perhaps in an exchange.

'Whichever way we look at it, it shows that the people populating the Denisova Cave at the time were advanced in technologies and had very well-established contacts with the outside world.'

Denisova Cave marked on the world map. Picture: The Siberian TimesToday ostriches are an exotic import into a couple of areas in Siberia, but were they endemic 50,000 years ago, or were they brought from afar?

Denisova Cave marked on the world map. Picture: The Siberian TimesToday ostriches are an exotic import into a couple of areas in Siberia, but were they endemic 50,000 years ago, or were they brought from afar?

Kozlikin acknowledged there are far more questions than answers.

'We don't know if they (prehistoric people) decorated elements of men, or women, or children or their clothing with these beads,' he said. 'We do not know where the beads were sewn on the clothing, if they were. Did they only decorate wealthy members of society? Were they a sign of a special religious status, or did they signify that the person had more authority than the others?

1,500-Year-Old Tomb Found in China with Incredible Golden JewelryArchaeologists Unearth Thracian Princess Grave Rich with Jewelry and Mythic MeaningOldest known Gold Jewelry in Europe Discovered at Bronze Age Bulgarian site'How did the beads, or the material for them get to Siberia? How much did they cost?

'What we do know for sure is that the beads were found in the Denisova Cave's 'lucky' eleventh layer, the same one where we found the world's oldest bracelet made from rare dark green stone. All finds from that layer have been dated as being 45,000 to 50,000 years old.

'We had three other beads found in 2005, 2006 and 2008. All the beads were discovered lying within six metres in the excavation in the eastern gallery of the cave.

'We cannot say if they all belonged to one person, but visually these beads look identical.'

Ostich eggshell beads from Border Cave in South Africa, dated 44,856-41,010. Picture: Lucinda BackwellYet they also appear similar to ostrich egg beads found in an area called Border Cave in South Africa that have been dated up to 44,000 years old. The site is in the foothills of the Lebombo Mountains in KwaZulu-Natal.

Ostich eggshell beads from Border Cave in South Africa, dated 44,856-41,010. Picture: Lucinda BackwellYet they also appear similar to ostrich egg beads found in an area called Border Cave in South Africa that have been dated up to 44,000 years old. The site is in the foothills of the Lebombo Mountains in KwaZulu-Natal.

Dr. Lucinda Backwell, senior researcher in the palaeo-anthropology department at Wits University, has previously highlighted how this African proto-civilisation 'adorned themselves with ostrich egg and marine shell beads'.

The Siberian beads is the latest discovery from the Denisova Cave which is possibly the finest natural repository of sequential early human history so far discovered anywhere on the planet.

The cave was occupied by Homo sapiens along with now extinct early humans - Neanderthals and Denisovans - for at least 288,000 years, and excavations have been underway here for three decades, with the prospect of many exciting finds to come in future.

Archeologists working inside the eastern gallery of the Denisova Cave. Pictures: The Siberian TimesIn August, we revealed the discovery of the world's oldest needle in the cave - still useable after 50,000 years.

Archeologists working inside the eastern gallery of the Denisova Cave. Pictures: The Siberian TimesIn August, we revealed the discovery of the world's oldest needle in the cave - still useable after 50,000 years.

Crafted from the bone of an ancient bird, it was made not by Homo sapiens or even Neanderthals, but by Denisovans.

Professor Mikhail Shunkov, head of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography in Novosibirsk, said: 'It is the most unique find of this season, which can even be called sensational. It is a needle made of bone.

'As of today it is the most ancient needle in the word. It is about 50,000 years old.'

Denisova Cave, pictures by Vera SalnitskayaThe article ‘

Paleolithic jewellery: still eye-catching after 50,000 years

’ originally appeared on The

Siberian Times

and has been republished with permission

Denisova Cave, pictures by Vera SalnitskayaThe article ‘

Paleolithic jewellery: still eye-catching after 50,000 years

’ originally appeared on The

Siberian Times

and has been republished with permission

By Tamara Zubchuk | The Siberian Times

Beads made from ostrich eggs buried in the Siberian cave around 2,000 generations ago reveal amazing artistic (and drilling) skills of our long-ago ancestors.

The fascinating collection of jewelry made of ostrich eggshells is being assembled by archeologists working in the world famous Denisova cave in Altai region. Ostriches in Siberia? 50,000 years ago?

Yes, it seems so. Or, at least, their eggshells made it here somehow.

In a month that has seen disclosures of the fossil of a tropical parrot in Siberia from at least five million years ago in the Miocene era, this elegant Paleolithic chic shows that our deep history (some 2,000 generations ago, give or take) contains many unexpected surprises.

Pictured here are finds from a collection of beads in the Denisova cave, perfectly drilled, and archeologists say they have now found one more close by, with full details to be revealed soon in a scientific journal. They are in no doubt that the beads are between 45,000 and 50,000 years old in the Upper Paleolithic era, making them older than strikingly similar finds 11,500 kilometers away in South Africa.

Beads found inside Denisova Cave in the Altai mountains. Pictures: Maksim KozlikinMaksim Kozlikin, researcher at the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography, Novosibirsk, said of the Siberian ostrich egg beads: 'This is no ordinary find. Our team got quite excited when we found the bead.

Beads found inside Denisova Cave in the Altai mountains. Pictures: Maksim KozlikinMaksim Kozlikin, researcher at the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography, Novosibirsk, said of the Siberian ostrich egg beads: 'This is no ordinary find. Our team got quite excited when we found the bead.'This is an amazing piece of work. The ostrich egg shell is quite robust material, but the holes in the beads must have been made with a fine stone drill.

Did Neanderthals make jewelry 130,000 years go? Eagle claws provide cluesThe skills and techniques used some 45,000 to 50,000 years ago are remarkable and more akin to the Neolithic era, dozens of millennia later.

He believes the beads may have been sewn into clothing - or formed part of a bracelet or necklace.

The Denisova Cave. Pictures: Vera SalnitskayaThe latest discovery 'is one centimetre in diameter, with a hole inside that is slightly wider than a millimetre,' he said.

The Denisova Cave. Pictures: Vera SalnitskayaThe latest discovery 'is one centimetre in diameter, with a hole inside that is slightly wider than a millimetre,' he said.Yet he admits: 'As of now, there is much more that we do not know about these beads than we do know. For example, we do not know where the beads were made.

'One version is that the egg shells could have been exported from Trans-Baikal or Mongolia with the beads manufactured here.

'Another possibility is that the beads were purchased elsewhere and delivered to the Altai Mountains perhaps in an exchange.

'Whichever way we look at it, it shows that the people populating the Denisova Cave at the time were advanced in technologies and had very well-established contacts with the outside world.'

Denisova Cave marked on the world map. Picture: The Siberian TimesToday ostriches are an exotic import into a couple of areas in Siberia, but were they endemic 50,000 years ago, or were they brought from afar?

Denisova Cave marked on the world map. Picture: The Siberian TimesToday ostriches are an exotic import into a couple of areas in Siberia, but were they endemic 50,000 years ago, or were they brought from afar?Kozlikin acknowledged there are far more questions than answers.

'We don't know if they (prehistoric people) decorated elements of men, or women, or children or their clothing with these beads,' he said. 'We do not know where the beads were sewn on the clothing, if they were. Did they only decorate wealthy members of society? Were they a sign of a special religious status, or did they signify that the person had more authority than the others?

1,500-Year-Old Tomb Found in China with Incredible Golden JewelryArchaeologists Unearth Thracian Princess Grave Rich with Jewelry and Mythic MeaningOldest known Gold Jewelry in Europe Discovered at Bronze Age Bulgarian site'How did the beads, or the material for them get to Siberia? How much did they cost?

'What we do know for sure is that the beads were found in the Denisova Cave's 'lucky' eleventh layer, the same one where we found the world's oldest bracelet made from rare dark green stone. All finds from that layer have been dated as being 45,000 to 50,000 years old.

'We had three other beads found in 2005, 2006 and 2008. All the beads were discovered lying within six metres in the excavation in the eastern gallery of the cave.

'We cannot say if they all belonged to one person, but visually these beads look identical.'

Ostich eggshell beads from Border Cave in South Africa, dated 44,856-41,010. Picture: Lucinda BackwellYet they also appear similar to ostrich egg beads found in an area called Border Cave in South Africa that have been dated up to 44,000 years old. The site is in the foothills of the Lebombo Mountains in KwaZulu-Natal.

Ostich eggshell beads from Border Cave in South Africa, dated 44,856-41,010. Picture: Lucinda BackwellYet they also appear similar to ostrich egg beads found in an area called Border Cave in South Africa that have been dated up to 44,000 years old. The site is in the foothills of the Lebombo Mountains in KwaZulu-Natal.Dr. Lucinda Backwell, senior researcher in the palaeo-anthropology department at Wits University, has previously highlighted how this African proto-civilisation 'adorned themselves with ostrich egg and marine shell beads'.

The Siberian beads is the latest discovery from the Denisova Cave which is possibly the finest natural repository of sequential early human history so far discovered anywhere on the planet.

The cave was occupied by Homo sapiens along with now extinct early humans - Neanderthals and Denisovans - for at least 288,000 years, and excavations have been underway here for three decades, with the prospect of many exciting finds to come in future.

Archeologists working inside the eastern gallery of the Denisova Cave. Pictures: The Siberian TimesIn August, we revealed the discovery of the world's oldest needle in the cave - still useable after 50,000 years.

Archeologists working inside the eastern gallery of the Denisova Cave. Pictures: The Siberian TimesIn August, we revealed the discovery of the world's oldest needle in the cave - still useable after 50,000 years.Crafted from the bone of an ancient bird, it was made not by Homo sapiens or even Neanderthals, but by Denisovans.

Professor Mikhail Shunkov, head of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography in Novosibirsk, said: 'It is the most unique find of this season, which can even be called sensational. It is a needle made of bone.

'As of today it is the most ancient needle in the word. It is about 50,000 years old.'

Denisova Cave, pictures by Vera SalnitskayaThe article ‘

Paleolithic jewellery: still eye-catching after 50,000 years

’ originally appeared on The

Siberian Times

and has been republished with permission

Denisova Cave, pictures by Vera SalnitskayaThe article ‘

Paleolithic jewellery: still eye-catching after 50,000 years

’ originally appeared on The

Siberian Times

and has been republished with permission

Published on November 12, 2016 03:00

November 11, 2016

Over 120 Carvings of Egyptian Boats Dating Back 3,800 Years Discovered in Abydos Building

Ancient Origins

Over 120 detailed images of ancient Egyptian boats dating back 3,800 years have been discovered carved into the wall of a building in Abydos, Egypt. The recent research has greatly expanded earlier knowledge of the site that derived from a brief, exploratory phase of work conducted in 1901–1903 by Arthur Weigall and Charles Currelly on behalf of the Egypt Exploration Fund. During that time Weigall discovered the tomb of Senwosret III, the fifth monarch of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom, who ruled from 1878 BC to 1839 BC during a time of great power and prosperity. According to contemporary archaeologists, the building is nearly four millennia old.

In a report recently published in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, Josef Wegner, a decorated Egyptologist and Associate Professor in Egyptology at the University of Pennsylvania and leader of the excavation, wrote that the series of images, known as a tableau, would have overlooked a real wooden boat, as evidenced by fragments from the boat’s structure that are still being excavated. In ancient Egypt, boats being buried near a pharaoh’s tomb wasn’t an uncommon custom, a fact that makes Wegner believe that the very few remaining planks of the wooden boat, were most likely constructed at Abydos, or could have possibly been dragged across the desert.

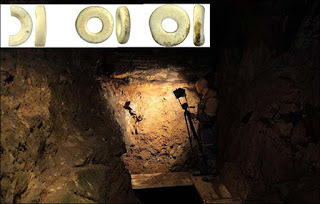

The interior of the boat building (J. Wegner)The unparalleled nature of this royal tomb enclosure has necessitated systematic examination of its component elements in order to understand the overall functions of the enclosure and the subterranean tomb located within it. Archaeologists recently found that the tableau was incised on the white plaster walls of the building. The occurrence of remnants of plaster and paint on a number of the wood fragments documented in 2014 and 2016 is intriguing. However, the most impressive feature of the South Abydos boat building is undoubtedly its decoration with numerous incised images of more than 120 individual boats, creating an informally arranged tableau extending over a total length of 82 feet (25m) on the side walls and end wall. The largest images are nearly 5 feet (152cm) in length and depict large, well-rendered boats depicted with masts, sails, rigging, deckhouses/cabins, rudders, oars and in some cases rowers.

The interior of the boat building (J. Wegner)The unparalleled nature of this royal tomb enclosure has necessitated systematic examination of its component elements in order to understand the overall functions of the enclosure and the subterranean tomb located within it. Archaeologists recently found that the tableau was incised on the white plaster walls of the building. The occurrence of remnants of plaster and paint on a number of the wood fragments documented in 2014 and 2016 is intriguing. However, the most impressive feature of the South Abydos boat building is undoubtedly its decoration with numerous incised images of more than 120 individual boats, creating an informally arranged tableau extending over a total length of 82 feet (25m) on the side walls and end wall. The largest images are nearly 5 feet (152cm) in length and depict large, well-rendered boats depicted with masts, sails, rigging, deckhouses/cabins, rudders, oars and in some cases rowers. Examples of boat images incised on the better-preserved north side of the building. (J. Wegner)Wegner reports that in addition to the boats, the tableau contains incised images of gazelle, cattle and flowers. Further, near the entranceway of the building, archaeologists discovered more than 145 pottery vessels, many of which are buried with their necks facing toward the building’s entrance. According to Wegner, the vessels are necked, liquid-storage jars, usually termed “beer jars” although probably used for storage and transport of a variety of liquids.

Examples of boat images incised on the better-preserved north side of the building. (J. Wegner)Wegner reports that in addition to the boats, the tableau contains incised images of gazelle, cattle and flowers. Further, near the entranceway of the building, archaeologists discovered more than 145 pottery vessels, many of which are buried with their necks facing toward the building’s entrance. According to Wegner, the vessels are necked, liquid-storage jars, usually termed “beer jars” although probably used for storage and transport of a variety of liquids.Although, the documentation of the building itself is now complete with a significant set of evidence regarding the building's function, there are still many questions to be answered. The archaeologists can’t be sure about who drew the tableau or why they created it. Wegner adds,

“We can’t conclusively answer that on the basis of what’s preserved. We could speculate that the people who built the boat also created the tableau. Or, perhaps, a group of people taking part in a funerary ceremony after the death of pharaoh Senwosret III etched the images onto the building walls. Yet another possibility is that a group of people gained access to the building after the pharaoh died and created the tableau. Archaeologists found that a group of individuals entered the building at some point after the pharaoh’s death and took the boat apart, reusing the planks.”

Aerial view taken by the British Royal Air Force, c.1924 showing the environs of the Senwosret III tomb enclosure. (Image courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society)Archaeologists are also curious about all the pottery found near the entrance of the building and the motivation behind the jar deposit and liquid offerings remains open to interpretation. Wegner says in his paper:

Aerial view taken by the British Royal Air Force, c.1924 showing the environs of the Senwosret III tomb enclosure. (Image courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society)Archaeologists are also curious about all the pottery found near the entrance of the building and the motivation behind the jar deposit and liquid offerings remains open to interpretation. Wegner says in his paper:“Liquid offerings form an integral part of the personal funerary cult in Egyptian mortuary practice, but are not normally associated with inanimate objects. In this case there may be some other level of symbolism. Potentially a massive decanting of liquid, likely predominantly water, at the entrance of the building was a way of magically floating the boat, now housed within its subterranean desert bunker, so that it might symbolically sail into the netherworld along with the king whose funerary ceremonies it may have just recently accompanied. Such an act would be consistent with the otherwise incongruous practice of burying watercraft in the desert, and the need to symbolically bridge the transition between the desert environment and a perceived use for the vessel in an afterlife existence where boats were as central to travel and transport as they were in the living world.”The only certain thing, according to Wegner, is that the evidence at the site adds further evidence that may eventually help solve the various mysteries and unsolved puzzles. He reassures us that his team plans to carry out excavations in the future to get all the answers the archaeological circles seek.

Wegner’s team, in cooperation with Egypt’s Ministryof State for Antiquities, carried out the excavations of the building between 2014 and 2016.

Top image: 3,800-year-old building containing 120 carvings of Egyptian boats. Credit: Josef Wegner.By Theodoros II

Published on November 11, 2016 03:00

November 10, 2016

8 things you (probably) didn’t know about Tutankhamun

History Extra

Golden funeral mask of Tutankhamun. Egyptian National Museum, Cairo. (Photo by Leemage/Corbis via Getty Images)

Golden funeral mask of Tutankhamun. Egyptian National Museum, Cairo. (Photo by Leemage/Corbis via Getty Images)

1) His original name was not TutankhamunTutankhamun was originally named Tutankhaten. This name, which literally means “living image of the Aten”, reflected the fact that Tutankhaten’s parents worshipped a sun god known as “the Aten”. After a few years on the throne the young king changed his religion, abandoned the Aten, and started to worship the god Amun [who was revered as king of the gods]. This caused him to change his name to Tutankhamun, or “living image of Amun”.

Tutankhamun was not, however, the name by which his people knew him. Like all of Egypt’s kings, Tutankhamun actually had five royal names. These took the form of short sentences that outlined the focus of his reign. Officially, he was:

(1) Horus Name: Image of births

(2) Two Ladies Name: Beautiful of laws who quells the Two Lands/who makes content all the gods

(3) Golden Horus Name: Elevated of appearances for the god/his father Re

(4) Prenomen: Nebkheperure

(5) Nomen: Tutankhamun

His last two names, known today as the prenomen and the nomen, are the names that we see written in cartouches (oval loops) on his monuments. We know him by his nomen, Tutankhamun. His people, however, knew him by his prenomen, Nebkheperure, which literally translates as “[the sun god] Re is the lord of manifestations”.

2) Tutankhamun has the smallest royal tomb in the Valley of the KingsThe first pharaohs built highly conspicuous pyramids in Egypt’s northern deserts. However, by the time of the New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC), this fashion had ended. Most kings were now buried in relative secrecy in rock-cut tombs tunnelled into the Valley of the Kings on the west bank of the Nile at the southern city of Thebes (modern-day Luxor). These tombs had inconspicuous doors, but were both spacious and well decorated inside.

Cemeteries carried their own potent magic, and dead kings were thought to have powerful spirits that might benefit others. Burial amongst his ancestors would have helped Tutankhamun to achieve his own afterlife. It therefore seems likely that Tutankhamun would have wished to be buried in a splendid tomb in either the main valley or in an offshoot, the Western Valley, where his grandfather, Amenhotep III, was buried. But, whatever he may have had intended, we know that Tutankhamun was actually buried in a cramped tomb cut into the floor of the main valley.

It may be that Tutankhamun simply died too young to complete his ambitious plans. His own tomb was unfinished, and so he had to be buried in a substitute, non-royal tomb. However, this seems unlikely, as other kings managed to build suitable tombs in just two or three years. It seems far more likely that Tutankhamun’s successor, Ay, a king who inherited the throne as an elderly man, made a strategic swap. Just four years after Tutankhamun’s death, Ay himself was buried in a splendid tomb in the Western Valley, close by the tomb of Amenhotep III.

The unexpectedly small size of Tutankhamun’s tomb has led to recent suggestions that there may be parts as yet undiscovered. Currently Egyptologists are investigating the possibility that there may be secret chambers hidden behind the plastered wall of his burial chamber.

British archaeologist and Egyptologist Howard Carter (left) and his assistant Arthur Callender opening the entrance to Tutankhamun's tomb, 1922. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

3) He was buried in a second-hand coffinTutankhamun’s mummy lay within a nest of three golden coffins, which fitted snugly one inside another like a set of Russian dolls. During the funeral ritual the combined coffins were placed in a rectangular stone sarcophagus. Unfortunately, the outer coffin proved to be slightly too big, and its toes peeked over the edge of the sarcophagus, preventing the lid from closing. Carpenters were quickly summoned and the coffin’s toes were cut away. More than 3,000 years later Howard Carter would find the fragments lying in the base of the sarcophagus.

All three of Tutankhamun’s coffins were similar in style: they were “anthropoid”, or human-form coffins, shaped to look like the god of the dead, Osiris, lying on his back and holding the crook and flail in his crossed arms. But the middle coffin had a slightly different style and its face did not look like the faces on other two coffins. Nor did it look like the face on Tutankhamun’s death mask. Many Egyptologists now believe that this middle coffin – along with some of Tutankhamun’s other grave goods – was originally made for the mysterious “Neferneferuaten” – an enigmatic individual whose name is recorded in inscriptions and who may have been Tutankhamun’s immediate predecessor. We do not know what happened to Neferneferuaten, nor how Tutankhamun came to be buried in his or her coffin.

Howard Carter removing oils from the coffin of Tutankhamun, 1922. (Photo by Mansell/Mansell/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

Howard Carter removing oils from the coffin of Tutankhamun, 1922. (Photo by Mansell/Mansell/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

4) Tutankhamun loved to hunt ostrichesTutankhamun’s ostrich-feather fan was discovered lying in his burial chamber, close by the king’s body. Originally the fan consisted of a long golden handle topped by a semi-circular ‘palm’ that supported 42 alternating brown and white feathers. These feathers crumbled away long ago, but their story is preserved in writing on the fan handle. This tells us that that the feathers were taken from ostriches captured by the king himself while hunting in the desert to the east of Heliopolis (near modern-day Cairo). The embossed scene on the palm shows, on one face, Tutankhamun setting off in his chariot to hunt ostrich, and on the reverse, the king returning in triumph with his prey.

Ostriches were important birds in ancient Egypt, and their feathers and eggs were prized as luxury items. Hunting ostriches was a royal sport that allowed the king to demonstrate his control over nature. It was a substitute for battle and, as such, was a dangerous occupation. We can see that Tutankhamun’s body was badly damaged before he was mummified. Is the placement of his ostrich fan so close to his body significant? Is this, perhaps, someone’s way of telling us that the young king died following a fatal accident on an ostrich hunt?

Howard Carter (left) and Arthur Callender systematically remove objects from the antechamber of the tomb of Tutankhamun with the assistance of an Egyptian labourer. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Howard Carter (left) and Arthur Callender systematically remove objects from the antechamber of the tomb of Tutankhamun with the assistance of an Egyptian labourer. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

5) His heart is missingThe ancient Egyptians believed that it was possible to live again after death, but thought that this could only be achieved if the body was preserved in a lifelike condition. This led them to develop the science of artificial mummification.

Essentially, mummification involved desiccating the body in natron salt, then wrapping it in many layers of bandages to preserve a lifelike shape. The body’s internal organs were removed at the start of the mummification process and preserved separately. The brain, its function then unknown, was simply thrown away – the heart, rather than the brain, was regarded as the organ of reasoning. As such, the heart would be required in the afterlife. It was therefore left in place and, if accidentally removed, immediately sewn back; though not always in its original location.

Tutankhamun, however, has no heart. Instead he was provided with an amuletic scarab inscribed with a funerary spell. This may have happened simply because the undertakers were careless, but it could also be a sign that Tutankhamun died far from home. By the time his body arrived at the undertakers’ workshop, his heart may have been too decayed to be preserved.

The mask of Tutankhamun, seen at the British Museum, London, January 1972. (Photo by Kean Collection/Getty Images)

6) One of Tutankhamun’s favourite possessions was an iron daggerHoward Carter discovered two daggers carefully wrapped inside Tutankhamun’s mummy bandages. One dagger had a gold blade, while the other had a blade made of iron. Each dagger had a gold sheath. Of the two, the iron dagger was by far the more valuable because, during Tutankhamun’s lifetime (he reigned from c1336–27 BC), iron, or “iron from the sky” as it was known, was a rare and precious metal. As its name suggests, Egypt’s “iron from the sky” was almost entirely obtained from meteorites.

Several other iron objects were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb: 16 miniature blades, a tiny headrest and an amulet. The fact that these pieces are not particularly well made, combined with their small size, suggest that they were made by local craftsmen who struggled to work the rare meteorite iron. The dagger blade, however, is very different. Beautifully crafted, it is likely to have been imported to Egypt from a region accustomed to working iron. The royal diplomatic archives tell us that, several years before Tutankhamun’s birth, king Tushratta of Mitanni sent a metal dagger to Egypt as a gift to his new son-in-law, Amenhotep III. Given the rarity of good quality iron artefacts at this time, it is possible that Amenhotep’s dagger was inherited by his grandson, Tutankhamun, and eventually buried with him. Given its prominent location within the mummy bandages, it may even be that Tushratta’s dagger was used in Tutankhamun’s mummification ritual.

Tutankhamun’s daggers, one with a blade of gold, the other of iron. (Robert Harding/Alamy Stock Photo)

Tutankhamun’s daggers, one with a blade of gold, the other of iron. (Robert Harding/Alamy Stock Photo)

7) His trumpets have entertained an audience of more than 150 millionTutankhamun’s grave goods included a small collection of musical instruments: one pair of ivory clappers, two sistra (rattles) and two trumpets, one made from silver with a gold mouthpiece and the other made of bronze partially overlaid by gold. This would not have made a very satisfactory orchestra, and it seems that music was not high on Tutankhamun’s list of priorities for his afterlife. In fact, his trumpets should more properly be classified as military equipment, while his clappers and sistra are likely to have had a ritual purpose.

On 16 April 1939, the two trumpets were played in a BBC live radio broadcast from Cairo Museum, which reached an estimated 150 million listeners. Bandsman James Tappern used a modern mouthpiece, which caused damage to the silver trumpet. In 1941 the bronze trumpet was played again, this time without a modern mouthpiece.

Some, influenced by the myth of “Tutankhamun’s curse”, have claimed that the trumpets have the power to summon war. They have suggested that it was the 1939 broadcast which caused Britain to enter the Second World War.

To listen to a clip of the broadcast, click here.

8) Tutankhamun was buried in the world’s most expensive coffinTwo of Tutankhamun’s three coffins were made of wood, covered with gold sheet. But, to Howard Carter’s great surprise, the innermost coffin was made from thick sheets of beaten gold. This coffin measures 1.88m in length, and weighs 110.4kg. If it were to be scrapped today it would be worth well over £1m. But as Tutankhamun’s final resting place it is, of course, priceless.

Joyce Tyldesley teaches a suite of online courses in Egyptology at the University of Manchester. She is the author of Tutankhamen’s Curse: the Developing History of an Egyptian King (Profile 2012).

Golden funeral mask of Tutankhamun. Egyptian National Museum, Cairo. (Photo by Leemage/Corbis via Getty Images)

Golden funeral mask of Tutankhamun. Egyptian National Museum, Cairo. (Photo by Leemage/Corbis via Getty Images) 1) His original name was not TutankhamunTutankhamun was originally named Tutankhaten. This name, which literally means “living image of the Aten”, reflected the fact that Tutankhaten’s parents worshipped a sun god known as “the Aten”. After a few years on the throne the young king changed his religion, abandoned the Aten, and started to worship the god Amun [who was revered as king of the gods]. This caused him to change his name to Tutankhamun, or “living image of Amun”.

Tutankhamun was not, however, the name by which his people knew him. Like all of Egypt’s kings, Tutankhamun actually had five royal names. These took the form of short sentences that outlined the focus of his reign. Officially, he was:

(1) Horus Name: Image of births

(2) Two Ladies Name: Beautiful of laws who quells the Two Lands/who makes content all the gods

(3) Golden Horus Name: Elevated of appearances for the god/his father Re

(4) Prenomen: Nebkheperure

(5) Nomen: Tutankhamun

His last two names, known today as the prenomen and the nomen, are the names that we see written in cartouches (oval loops) on his monuments. We know him by his nomen, Tutankhamun. His people, however, knew him by his prenomen, Nebkheperure, which literally translates as “[the sun god] Re is the lord of manifestations”.

2) Tutankhamun has the smallest royal tomb in the Valley of the KingsThe first pharaohs built highly conspicuous pyramids in Egypt’s northern deserts. However, by the time of the New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC), this fashion had ended. Most kings were now buried in relative secrecy in rock-cut tombs tunnelled into the Valley of the Kings on the west bank of the Nile at the southern city of Thebes (modern-day Luxor). These tombs had inconspicuous doors, but were both spacious and well decorated inside.

Cemeteries carried their own potent magic, and dead kings were thought to have powerful spirits that might benefit others. Burial amongst his ancestors would have helped Tutankhamun to achieve his own afterlife. It therefore seems likely that Tutankhamun would have wished to be buried in a splendid tomb in either the main valley or in an offshoot, the Western Valley, where his grandfather, Amenhotep III, was buried. But, whatever he may have had intended, we know that Tutankhamun was actually buried in a cramped tomb cut into the floor of the main valley.

It may be that Tutankhamun simply died too young to complete his ambitious plans. His own tomb was unfinished, and so he had to be buried in a substitute, non-royal tomb. However, this seems unlikely, as other kings managed to build suitable tombs in just two or three years. It seems far more likely that Tutankhamun’s successor, Ay, a king who inherited the throne as an elderly man, made a strategic swap. Just four years after Tutankhamun’s death, Ay himself was buried in a splendid tomb in the Western Valley, close by the tomb of Amenhotep III.

The unexpectedly small size of Tutankhamun’s tomb has led to recent suggestions that there may be parts as yet undiscovered. Currently Egyptologists are investigating the possibility that there may be secret chambers hidden behind the plastered wall of his burial chamber.

British archaeologist and Egyptologist Howard Carter (left) and his assistant Arthur Callender opening the entrance to Tutankhamun's tomb, 1922. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

3) He was buried in a second-hand coffinTutankhamun’s mummy lay within a nest of three golden coffins, which fitted snugly one inside another like a set of Russian dolls. During the funeral ritual the combined coffins were placed in a rectangular stone sarcophagus. Unfortunately, the outer coffin proved to be slightly too big, and its toes peeked over the edge of the sarcophagus, preventing the lid from closing. Carpenters were quickly summoned and the coffin’s toes were cut away. More than 3,000 years later Howard Carter would find the fragments lying in the base of the sarcophagus.

All three of Tutankhamun’s coffins were similar in style: they were “anthropoid”, or human-form coffins, shaped to look like the god of the dead, Osiris, lying on his back and holding the crook and flail in his crossed arms. But the middle coffin had a slightly different style and its face did not look like the faces on other two coffins. Nor did it look like the face on Tutankhamun’s death mask. Many Egyptologists now believe that this middle coffin – along with some of Tutankhamun’s other grave goods – was originally made for the mysterious “Neferneferuaten” – an enigmatic individual whose name is recorded in inscriptions and who may have been Tutankhamun’s immediate predecessor. We do not know what happened to Neferneferuaten, nor how Tutankhamun came to be buried in his or her coffin.

Howard Carter removing oils from the coffin of Tutankhamun, 1922. (Photo by Mansell/Mansell/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

Howard Carter removing oils from the coffin of Tutankhamun, 1922. (Photo by Mansell/Mansell/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)4) Tutankhamun loved to hunt ostrichesTutankhamun’s ostrich-feather fan was discovered lying in his burial chamber, close by the king’s body. Originally the fan consisted of a long golden handle topped by a semi-circular ‘palm’ that supported 42 alternating brown and white feathers. These feathers crumbled away long ago, but their story is preserved in writing on the fan handle. This tells us that that the feathers were taken from ostriches captured by the king himself while hunting in the desert to the east of Heliopolis (near modern-day Cairo). The embossed scene on the palm shows, on one face, Tutankhamun setting off in his chariot to hunt ostrich, and on the reverse, the king returning in triumph with his prey.

Ostriches were important birds in ancient Egypt, and their feathers and eggs were prized as luxury items. Hunting ostriches was a royal sport that allowed the king to demonstrate his control over nature. It was a substitute for battle and, as such, was a dangerous occupation. We can see that Tutankhamun’s body was badly damaged before he was mummified. Is the placement of his ostrich fan so close to his body significant? Is this, perhaps, someone’s way of telling us that the young king died following a fatal accident on an ostrich hunt?

Howard Carter (left) and Arthur Callender systematically remove objects from the antechamber of the tomb of Tutankhamun with the assistance of an Egyptian labourer. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Howard Carter (left) and Arthur Callender systematically remove objects from the antechamber of the tomb of Tutankhamun with the assistance of an Egyptian labourer. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)5) His heart is missingThe ancient Egyptians believed that it was possible to live again after death, but thought that this could only be achieved if the body was preserved in a lifelike condition. This led them to develop the science of artificial mummification.

Essentially, mummification involved desiccating the body in natron salt, then wrapping it in many layers of bandages to preserve a lifelike shape. The body’s internal organs were removed at the start of the mummification process and preserved separately. The brain, its function then unknown, was simply thrown away – the heart, rather than the brain, was regarded as the organ of reasoning. As such, the heart would be required in the afterlife. It was therefore left in place and, if accidentally removed, immediately sewn back; though not always in its original location.

Tutankhamun, however, has no heart. Instead he was provided with an amuletic scarab inscribed with a funerary spell. This may have happened simply because the undertakers were careless, but it could also be a sign that Tutankhamun died far from home. By the time his body arrived at the undertakers’ workshop, his heart may have been too decayed to be preserved.

The mask of Tutankhamun, seen at the British Museum, London, January 1972. (Photo by Kean Collection/Getty Images)

6) One of Tutankhamun’s favourite possessions was an iron daggerHoward Carter discovered two daggers carefully wrapped inside Tutankhamun’s mummy bandages. One dagger had a gold blade, while the other had a blade made of iron. Each dagger had a gold sheath. Of the two, the iron dagger was by far the more valuable because, during Tutankhamun’s lifetime (he reigned from c1336–27 BC), iron, or “iron from the sky” as it was known, was a rare and precious metal. As its name suggests, Egypt’s “iron from the sky” was almost entirely obtained from meteorites.

Several other iron objects were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb: 16 miniature blades, a tiny headrest and an amulet. The fact that these pieces are not particularly well made, combined with their small size, suggest that they were made by local craftsmen who struggled to work the rare meteorite iron. The dagger blade, however, is very different. Beautifully crafted, it is likely to have been imported to Egypt from a region accustomed to working iron. The royal diplomatic archives tell us that, several years before Tutankhamun’s birth, king Tushratta of Mitanni sent a metal dagger to Egypt as a gift to his new son-in-law, Amenhotep III. Given the rarity of good quality iron artefacts at this time, it is possible that Amenhotep’s dagger was inherited by his grandson, Tutankhamun, and eventually buried with him. Given its prominent location within the mummy bandages, it may even be that Tushratta’s dagger was used in Tutankhamun’s mummification ritual.

Tutankhamun’s daggers, one with a blade of gold, the other of iron. (Robert Harding/Alamy Stock Photo)

Tutankhamun’s daggers, one with a blade of gold, the other of iron. (Robert Harding/Alamy Stock Photo)7) His trumpets have entertained an audience of more than 150 millionTutankhamun’s grave goods included a small collection of musical instruments: one pair of ivory clappers, two sistra (rattles) and two trumpets, one made from silver with a gold mouthpiece and the other made of bronze partially overlaid by gold. This would not have made a very satisfactory orchestra, and it seems that music was not high on Tutankhamun’s list of priorities for his afterlife. In fact, his trumpets should more properly be classified as military equipment, while his clappers and sistra are likely to have had a ritual purpose.

On 16 April 1939, the two trumpets were played in a BBC live radio broadcast from Cairo Museum, which reached an estimated 150 million listeners. Bandsman James Tappern used a modern mouthpiece, which caused damage to the silver trumpet. In 1941 the bronze trumpet was played again, this time without a modern mouthpiece.

Some, influenced by the myth of “Tutankhamun’s curse”, have claimed that the trumpets have the power to summon war. They have suggested that it was the 1939 broadcast which caused Britain to enter the Second World War.

To listen to a clip of the broadcast, click here.

8) Tutankhamun was buried in the world’s most expensive coffinTwo of Tutankhamun’s three coffins were made of wood, covered with gold sheet. But, to Howard Carter’s great surprise, the innermost coffin was made from thick sheets of beaten gold. This coffin measures 1.88m in length, and weighs 110.4kg. If it were to be scrapped today it would be worth well over £1m. But as Tutankhamun’s final resting place it is, of course, priceless.

Joyce Tyldesley teaches a suite of online courses in Egyptology at the University of Manchester. She is the author of Tutankhamen’s Curse: the Developing History of an Egyptian King (Profile 2012).

Published on November 10, 2016 03:00

November 9, 2016

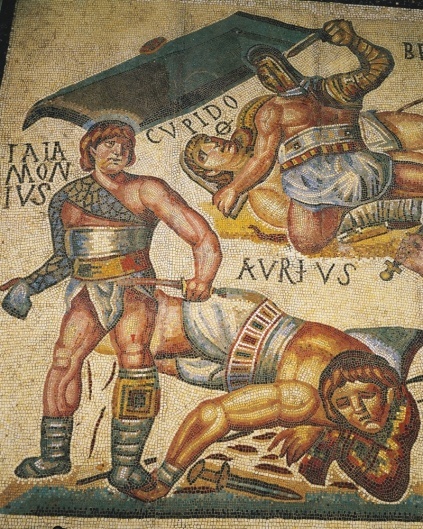

Gladiators in Ancient Rome: how did they live and die?

History Extra

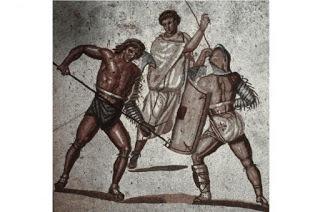

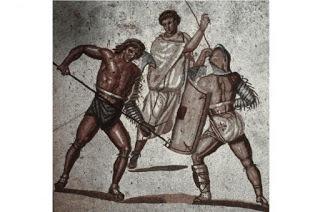

A retiarius (left) and secutor do battle in a mosaic. The former’s weapons consisted of a barbed trident and weighted net. (AKG Images)

In 1993 Austrian archaeologists working at the Roman city of Ephesus in Turkey made a spectacular discovery – a cemetery marked by the tombstones of gladiators. The stones gave the names of the men and showed their equipment – helmets, shields, the palm fronds of victory.

With the tombstones were the skeletal remains of the fighters themselves, many of which bore the marks of healed wounds as well as the injuries that caused their deaths. Perhaps the most spectacular find was a skull pierced with three neat, evenly spaced holes. This man had been slain with the barbed trident wielded by a type of gladiator called a retiarius, who also fought with a weighted net.

The gladiator has long been an iconic symbol of ancient Rome, and a popular element in any Roman epic movie, but what do we really know about the lives and deaths of these men?

Until the discovery of the cities of Vesuvius in the 18th century, virtually everything we knew about gladiators came from references in ancient texts, from random finds of stone sculptures and inscriptions, and the impressive structures of the amphitheatres dotted about all over the Roman empire.

It is difficult now to quite comprehend the impact that the discovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum (both in the 18th century) had on the classically educated of Europe, who suddenly saw the reality of Roman lives in a bewildering array of objects, graffiti and paintings.

The reality could be spectacular, and in some cases seemed to confirm the more lurid stories in the sources. In 1764 the temple of Isis at Pompeii confirmed the practise of mysterious and esoteric eastern religions. Two years later, in rooms around the courtyard of the theatre, a number of skeletons were found together with a large quantity of gladiatorial armour, identifying the rooms as a gladiator barracks. Among the dead was a woman adorned with bracelets, rings and an emerald necklace.

Ever since, this discovery has become part of the mythology not only of Pompeii, but of the arena. At the time, it seemed to confirm scandalous stories in ancient sources of wealthy and aristocratic women having sexual adventures with brawny gladiators – though we now see the 18 skeletons in this room as a group of frightened fugitives sheltering from the disaster of the volcanic eruption.

Reliefs showing gladiators in the arena. The most successful could earn fame, if not fortune, but few would survive more than a dozen fights. (Bridgeman Art Library)

From the point of view of reconstructing the gladiator, the most important discovery was the bronze gladiatorial armour and weaponry. This included 15 helmets richly ornamented with mythological scenes, and six of the curious shoulder guards known as galerus.

Gladiators were divided into categories – each armed and attired in a characteristic manner – and were then pitched against one another in pairings designed to show a variety of forms of combat. Each different type of equipment provided varying levels of protection to the body, deliberately giving the opponent the opportunity to aim for specific points of vulnerability.

All gladiator categories wore a basic subligaculm and balteus (a loincloth and broad belt). Among the most heavily armed gladiators were the thraex (Thracian) and the hoplomachus (inspired by Greek hoplite soldiers). Both wore padded leg-guards with bronze greaves (a form of armour) strapped over them on their legs (14 of such greaves were found in Pompeii).

Each carried a small shield: rectangular for the thraex, who was armed with a short, curved sword; round for the hoplomachus, who carried a spear and short sword. Both wore a padded arm-guard or manica, but only on the sword/spear arm. The shield arm was unprotected, as was the torso.

The thraex and hoplomachus wore heavy bronze helmets of the type found in Pompeii. These had broad brims, high crests and face guards. Visibility was limited to what he could see through a pair of bronze grilles.

As gladiatorial re-enactors have discovered, breathing in these helmets isn’t easy, as the wearer is forced to inhale the air trapped in the face guard. Factor in fear and exertion – which would inevitably shorten the breath anyway – and you’ve got the makings of a lung-busting experience.

[image error]

A gladiator’s helmet found in Pompeii. Breathing in these helmets wouldn’t have been easy, as the wearer was forced to inhale the air trapped in the face guard. (AKG Images)

Another type of gladiator to wear a large helmet and carry a short sword was the murmillo. He was also armed with a large rectangular shield, which he used to defend his legs. He only wore armour on one leg – though the leg on the shield side was protected with padding and greave.

Two other gladiators – the provocator and secutor – also fought with one vulnerable leg, and only carried a manica on the weapon arm. While they also carried a short sword and large shield, they wore lighter helmets than the thraex, hoplomachus and murmillo.

The secutor’s helmet fitted close to his head. Visibility was restricted to two small eye-holes, and there was no decoration. The helmet was shaped like the head of a fish – for the simple reason that the secutor’s opponent, the retiarius, was equipped as a fisherman.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Gladiators in Britain Compared with most other provinces of the Roman empire, Britain has surprisingly little evidence for gladiators. The differences between Britain’s amphitheatres may help to explain this. Those sited at the legionary fortresses of Chester and Caerleon were built in the AD 70s to serve legionaries – the citizen-soldiers of Rome. Drawn from all over the empire, they would have expected to be provided with an amphitheatre – both for entertainment and to enact games on festivals associated with the imperial cult.

The legionary amphitheatres were stone-built like many across the empire. However, at the British tribal capitals the Romans built earthwork amphitheatres. There is evidence to show that these were infrequently used, and it appears that the native population didn’t wholly embrace the Mediterranean concept of the Roman games.

Despite this, there is evidence for the presence of gladiators. In 1738, a stone relief was found near Chester amphitheatre showing a left-handed retiarius – the only such depiction from the empire. And at Caerleon, a graffito on a stone shows the trident and galerus of a retiarius flanked by victory palms. These are the only references to gladiators from any British amphitheatre, and both are from the legionary sites.

In Britain there is but a single gladiator wall painting. Of the three gladiator mosaics left to us, the best is a frieze of cupid-gladiators at the villa of Bignor in Sussex. This features a secutor, a retiarius, and the summa rudis (referee) in a comic strip of an arena event.

Knife handles in bone and bronze are also found in the form of gladiators. An evocative piece is a potsherd discovered in Leicester in 1851, on which was scratched the words “VERECVNDA LVDIA : LVCIVS GLADIATOR”, or “Verecunda the actress, Lucius the gladiator”. This love token may relate to a couple in Britain but there is ambiguity. The pottery is of a type imported from Italy, and the graffito may have been made there as well.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The retiarius is perhaps the most extraordinary of all the gladiator classes, and his equipment shows most clearly the carefully choreographed balance between strength and vulnerability that ensured a degree of fairness and balance in gladiatorial combat.

The retiarius was almost wholly unprotected. If he was right-handed, his left arm would be protected by a padded manica, and on his left shoulder would be strapped a high shoulder-guard, the galerus. An example of a galerus was found in the Pompeii barracks, decorated with a dolphin and a trident, a crab and the anchor and rudder of a ship.

[image error]

Bronze greaves (leg protectors) discovered at Pompeii’s gladiator barracks. The discovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum transformed our knowledge of ancient Rome, and the lives of its arena-warriors. (AKG Images)

The retiarius wore no helmet, but he was armed with a long-handled trident, a short knife and a lead-weighted net or rete, after which he was named. The net could be used as a flail, but it is clear that the job of the retiarius was to throw the net over his opponent, catching the fish-like secutor, and then dispatching him with the trident.

Once he’d thrown the net the retiarius could use the trident as a pole arm. This is when the galerus comes into play: when using the trident two-handed, the left shoulder would be forward, and the galerus would prove an effective head-guard.

One tomb relief of a retiarius from Romania shows him holding what seems to be a four-bladed knife. The identity of this weapon remained a mystery until archaeologists discovered a femur at the Ephesus cemetery. This showed a healed wound just above the knee consisting of four punctures in the pattern of a four on dice.

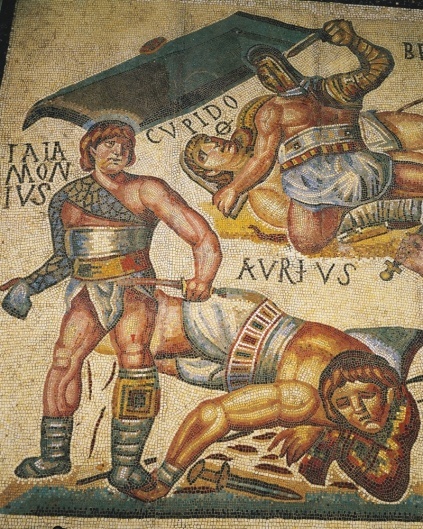

The effectiveness of the retiarius is gruesomely revealed by the punctured skull discovered in Ephesus, but he did not always get his own way. A mosaic from Rome, now in Madrid, shows two scenes from a fight between a secutor named Astanax and the retiarius Kalendio. Kalendio threw his net over Astanax, but when he caught his trident in the folds of the net, Astanax could cut his way out and defeat Kalendio, who was then killed.

The skull of one of the 68 gladiators’ skeletons found in Ephesus in 1993. The bones suggest that the fighters usually died from large, single wounds, rather than numerous smaller ones – the kind delivered in a coup de grâce. (Medical University of Vienna)

The same mosaic features another figure – an unarmed man in a tunic carrying a light wand. He is the summa rudis, the referee, reminding us that this was not a free-for-all, but a fight that must be carried out within a framework of rules and rituals. These rules would clearly be understood by the audience, who would have been at least as appreciative of the fighters’ skills as excited by pure blood-lust.

The audience would also have been fully aware who was putting on such entertainment for them. Gladiatorial shows were almost always staged by leading citizens – often to enhance their political careers by currying favour with the electorate. Thus the walls of Pompeii are daubed with painted election notices, alongside advertisements for gladiatorial spectacles.

One of many examples, found near the forum, reads: “The gladiatorial troupe of Aulus Suettius Certus will fight at Pompeii on 31 May. There will be a hunt and awnings. Good fortune to all Neronian games.”

There is little doubt about the popularity of the combats. Even tombs are covered with scratched graffiti showing the results of particular fights. A cartoon of two gladiators fighting in neighbouring Nola is captioned “Marcus Attius, novice, victor; Hilarius, Neronian, fought 14, 12 victories, reprieved.”

The tombstone of a murmillo gladiator, holding the palm of victory. His helmet lies beside him on the ground. (Alamy)

This says a lot. Attius unexpectedly beat a veteran, but, like most of the combats recorded at Pompeii, the loser was spared. Being a gladiator was not an automatic sentence of violent death. The person funding the games (the editor) would commission a troupe (familia) of gladiators run by a proprietor/trainer (lanista). One such lanista, recorded in Pompeian graffiti,was Marcus Mesonius. He would acquire gladiators from the slave market. Legally, gladiators were the lowest of the low in Roman society, but a trained gladiator was a valuable commodity to a lanista, representing a considerable investment of time and money, and it would be in his interest to keep his stable well and to minimise the death rate.

Survival ratesA graffito now in Naples Museum gives the results of a show put on by Mesonius. Of 18 gladiators who fought, we know of eight victors, five defeated and reprieved, and three killed. This kind of ratio may be typical given the records in graffiti and on tombstones. There were veterans; an unnamed retiarius on a tombstone in Rome boasted 14 victories, but few survived more than a dozen fights.

The painstaking forensic work on the Ephesus gladiator skeletons has provided startling and intimate insights into the way these men lived and died. Of the 68 bodies found, 66 were of adult males in their 20s. A rigorous training programme was attested by the enlarged muscle attachments of arms and legs. These were strong, athletic men, whose diet was dominated by grains and pulses, exactly as reported in classical texts. Yet as well as muscle and stamina, gladiators needed a good layer of fat to protect them from cuts.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The emperor who loved to fight The relationship between the emperor and the arena was complex. Emperors could get a bad reputation for showing too much enthusiasm for spectacles of death. Claudius, for example, was reputed to have keenly watched the faces of gladiators as they died, favouring the killing of the helmetless retiarii. For a member of the elite to fight in the arena was shameful – which was why Caligula, Nero and Commodus forced well-born Romans to do so.

Special contempt was reserved for those emperors who chose to fight as gladiators in the arena. Caligula liked to appear as a thraex. Commodus, however, was the most notorious for his arena appearances. He fought as a secutor, and was a scaeva – a left hander. According to Cassius Dio he substituted the head of the Colossus by the Colosseum with his own, gave it a club and bronze lion to make it look like Hercules (with whom he identified himself). He inscribed his own titles upon it, ending “champion of secutores – the only left-handed gladiator to conquer 12 times one thousand men”.

Interestingly, Aurelius Victor relates a story of Commodus refusing to fight a gladiator in the arena. The gladiator’s name was Scaeva. Perhaps Commodus was afraid to lose his usual natural advantage in fighting a fellow southpaw.

In AD 192, intending to assume the consulship of Rome in gladiatorial guise, he was strangled by an athlete. Thus he died in shame without the opportunity to take the coup de grâce with dignity like a true gladiator.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Ephesus skeletons also provided evidence for good medical treatment. Many well-healed wounds were found on the bodies, including 11 head wounds, a well-set broken arm and a professional leg amputation. On the other hand, 39 individuals exhibited single wounds sustained at or around the time of death. This suggests that these men did not die from multiple injuries but a lone wound. This provides further evidence for the enforcement of strict rules in the arena, and the delivery of a coup de grâce.

Though this mosaic from Terranova in Italy (left) shows gladiators dispatching their opponents, evidence suggests that defeated fighters were often given a reprieve. (Bridgeman Art Library)

At the end of a bout a defeated gladiator was required to wait for the life or death decision of the editor of the games. If the vote was for death, he was expected to accept it unflinchingly and calmly. It would be delivered as swiftly and effectively as possible. Cicero speaks of this: “What even mediocre gladiator ever groans, ever alters the expression on his face. And which of them, even when he does succumb, ever contracts his neck when ordered to receive the blow?”

As we have seen, gladiators were at the bottom of the heap in Roman society. This remained the case no matter how much they were feted by the people. Above most qualities, the Romans valued ‘virtus’, which meant, first and foremost, acting in a brave and soldierly fashion. In the manner of his fighting, and above all in his quiet and courageous acceptance of death, even a gladiator, a despised slave, could display this.

Tony Wilmott is a senior archaeologist and Roman specialist with English Heritage. He was joint director of the Chester Amphitheatre excavations, and is the author of The Roman Amphitheatre in Britain.