MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 67

February 7, 2017

History’s most surprising statistics

History Extra

Illustrations by James Albon.

4: The number of years' wages that a pound of wool – twice dyed in best quality Tyrian purple – would cost a Roman soldier during the first century AD

Since c1500 BC, purple – a dye produced from the gland secretions of types of shellfish – was the colour of kings, priests, magistrates and emperors, with the highest quality dye originating in Tyre, in ancient Phoenicia (now modern Lebanon).

Its cost was phenomenal. In the first century AD, a pound of wool, twice dyed in best quality Tyrian purple, cost around 1,000 denarii – more than four times the annual wage of a Roman soldier. The AD 301 Edict of Diocletian (also know as the Edict of Maximum Prices), which attempted to control runaway inflation in the empire, lists the most expensive dyed silk as costing 150,000 denarii per pound! Meanwhile the, admittedly satirical, poet Martial claimed that a praetor’s purple cloak actually cost 100 times more than a soldier’s pay.

The reasons behind the astronomical cost lie in the obtaining of the dye itself. This procedure involved a lengthy process of fishing – using wicker traps primed with bait – followed by the extraction of minute quantities of the dye by a long, laborious and smelly process from thousands of shellfish. Pliny the Elder explained the process and gave production statistics which indicate the vast number of shells required.

Pliny stated that if a mollusc gland weighed a gram (in modern weights), more than 3.5m molluscs would produce just 500 pounds of dye. Pliny the Elder was not exaggerating. In modern times, Tyrian purple has been recreated, at great expense. When the German chemist Paul Friedander tried to recreate the colour in 1909, he needed 12,000 molluscs to produce just 1.4 ounces of dye, enough to colour a handkerchief. In 2000, a gram of Tyrian purple, made from 10,000 molluscs according to the original formula, cost 2,000 euros. Peter Jones is author of Veni, Vidi, Vici (Atlantic Books, 2013)

10 million: The number of fleeces exported annually from England by c1300

England has often been referred to as the Australia of the Middle Ages, a reference to its booming wool trade (something that Australia experienced in the 19th century). By the 14th century, English farmers had developed breeds of sheep that produced fleeces of varying weight and quality, some of which were among the best in Europe.

English wool was widely sought after by the cloth-makers of Flanders and Italy who needed fine wool to produce the rich scarlet cloths worn by kings, nobles and bishops. The 14th century had seen a huge growth in the cloth trade, particularly in Ypres, Ghent and Bruges.

To keep up with the high demand, English wool producers expanded their flocks, often going to great trouble to keep them from harm. Many kept their sheep on hill pastures during the summer, moving them to sheltered valleys in the winter. Others built sheep houses or sheepcotes where the animals could shelter in the worst weather and where food, such as peas in straw, was kept.

It is often assumed that monasteries such as Fountains Abbey in North Yorkshire, which kept thousands of sheep, met Europe’s increasing demand for wool, but in fact the combined flocks of peasants, each of whom kept 30–50 animals, outnumbered those of the great estates. To gather the fleeces of these scattered flocks needed organisation – a role that was filled by entrepreneurs, woolmen or woolmongers who bought the wool and sent it to the ports. Some of the big producers – monasteries and lay landlords – often acted as middlemen, collecting the local peasant wool and sending it with their own.

Finances, too, were complicated, and there was much use of credit during the period. An Italian or Flemish merchant would often advance money to a producer, such as a monastery, on the condition that he would buy their wool, sometimes quite cheaply. These contracts usually stretched into the future, so that a monastery might have sold its wool four years in advance.

Chris Dyer is emeritus professor of regional and local history at the University of Leicester

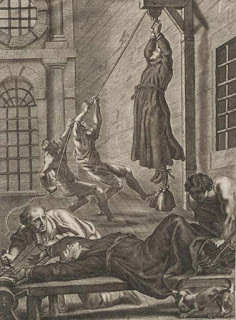

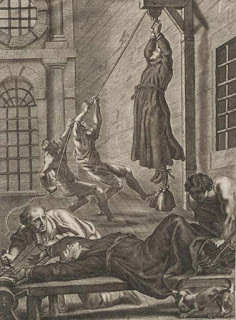

25: The percentage of English men believed to have served in arms for king or parliament at one time or another during the Civil War

The Civil War of the 17th century saw huge numbers of men leave their towns and villages to go and fight, as England, Scotland and Ireland were torn apart by the bitter conflict between the crown and parliament. The historian Charles Carlton has calculated that, proportionately, more of the English population died in the Civil War than in the First World War, and some 25 per cent of English men are thought to have served in arms for king or parliament at one time or another.

The village of Myddle in Shropshire is the only parish in England for which we know exactly how many people went to war. This is thanks to the writings of yeoman Richard Gough, whose History of Myddle, written between 1700 and 1706, tells us that “out of these three towns – that’s to say the hamlets of Myddle parish – of Myddle, Marton and Newton, there went no less than 20 men, of which number 13 were killed in the wars...”

Gough then proceeds to name the Myddle men who went to fight, along with their occupations and whether they lived or died. “Richard Chalenor of Myddle”, he writes, “being a big lad went to Shrewsbury and there listed, and went to Edgehill Fight which was on October 23rd 1642, and was never heard of afterwards in this country...”

The experience of Myddle in the Civil War is by no means unique: it is remarkable simply for the information recorded by Gough. What’s more, his description of one John Mould – who “was shot through the leg with a musket bullet which broke the master bone of his leg” so that it remained “very crooked as long as he lived” – reminds us that, just as in modern wars, huge numbers of men returned to their daily lives physically scarred by the events of the Civil War.

In the wake of the conflict, parliament, which was now in power, provided pensions for wounded parliamentarian soldiers, but offered nothing for those who had fought for the king. In 1660, however, when the monarchy was restored in the form of Charles II, the situation was turned on its head and injured royalists received financial help. Others had to rely on the assistance of their charitable neighbours.

Gough’s writings give historians a wonderful insight into the lives of ordinary soldiers in an era that is so often recorded by the gentry alone. And, to quote Gough himself, who was a young boy during the Civil War: “If so many died out of these three [hamlets], we may reasonably guess that many thousands died in England in that war.” Gough’s History of Myddle is a fitting tribute to those men.

Professor Mark Stoyle is author of The Black Legend of Prince Rupert’s Dog: Witchcraft and Propaganda during the English Civil War (Exeter, 2011)

6: The life expectancy in weeks for newly arrived horses in South Africa during the Anglo-Boer War

Horses played an essential role in the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902), but paid a terrible price: of the 518,704 horses and 150,781 mules and donkeys sent to British forces in South Africa during the conflict, around two thirds (347,007 horses, 53,339 mules and donkeys) never made it home.

At the start of the war, British units travelled from a northern hemisphere winter to a South African summer, meaning that cavalry horses still had their winter coats and suffered severely from the heat. What’s more, the animals endured a long sea voyage of up to six weeks before they even reached South Africa. On arrival, horses were often given no time to recover from the voyage or acclimatise to South African conditions; instead they were rushed into action right away. What’s more, some 13,144 horses and 2,816 mules and donkeys were lost on the outward voyage.

The constant demand for fresh animals meant that additional horses had to be imported but, in contrast to the ponies of the Boers, these imported horses could not eat South African foliage. It proved almost impossible to provide enough food for the animals, especially as Boer guerrillas constantly attacked British supply lines.

After the war, cavalry officer Michael Rimington recalled that the process of bringing animals to the front was “thirty days’ voyage, followed by a five or six days’ railway journey, then semi-starvation at the end of a line of communication, then some quick work followed by two or three days’ total starvation, then more work...”. Ignorance in horse care did not help either: one newly arrived soldier asked Rimington whether he should feed his horse beef or mutton, and the animals were often ridden until they simply collapsed. Little surprise, then, that the average life expectancy of a newly arrived horse in South Africa was just six weeks.

Dr Spencer Jones is author of Stemming the Tide: Officers and Leadership in the British Expeditionary Force 1914 (Helion & Co, 2013)

$1,000: The price per ounce that the US government was paying for penicillin in 1943

In 1940, a team of scientists, led by pharmacologist Howard Florey, discovered the means of extracting penicillin from the very dilute solution produced by penicillium mould. After proving that the substance could cure infections in mice, the Oxford team tested penicillin on human patients – with remarkable results.

But despite taking a small sample of the mould to America and discussing production methods with the US government laboratory and several US companies, by 1943, penicillin was being produced at scarcely more than the laboratory scale previously seen at Oxford.

After testing the substance on patients, the US government purchased penicillin from its manufacturers at a price of $200 for a million units. This was equivalent to $1,000 an ounce at a time when gold cost just $35 an ounce.

The big breakthrough for the drug came with developments in manufacturing techniques, which saw pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer producing penicillin on a massive scale in huge vats. This meant that a single tank of 10,000 gallons could produce the equivalent amount of penicillin as would fill 60,000–70,000 two-litre bottles. The impact of this engineering triumph was intensified by the discovery in 1943 of a new strain of penicillium mould that was much more suitable for growing in the deep vats than the original British strain. This new strain was first found on a melon in Peoria, Illinois, by a technician who later came to be known as Moldy Mary.

By 1945, the American pharmaceutical company Merck was selling penicillin at $6,000 per billion units at a time when penicillin in Europe was still scarce. Three years later, the price had halved and Procaine penicillin, which was metabolised more slowly (meaning fewer injections), had been introduced.

Although two large processing plants were built in Britain after the Second World War, demand for penicillin was so great and so unexpected that its cost – and that of other new drugs including streptomycin and cortisone – forced the new NHS to charge for medicines.

Robert Bud is keeper of science and medicine at the Science Museum, London

17: The number of women candidates who stood for election to parliament in 1918

Thousands of women during the Edwardian era became politicised during the campaign for the parliamentary vote, so at first glance it may seem surprising that only 17 women stood for election in 1918 – the first in which women could participate in the representative process, both as voters and as parliamentary candidates.

The Representation of the People Act, which received Royal Assent on 6 February 1918, was unclear as to whether women could stand as parliamentary candidates and opinions on the issue were divided. When the coalition government rushed through the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Bill, which became law on 21 November 1918, a general election for 14 December had already been announced, with 4 December given as the date when nominations for parliamentary candidates had to be received. This gave women who wished to stand for election just three weeks in which to find a seat, enter a nomination, choose an election agent, draw up election policy, secure the support of unpaid helpers, raise funds, organise meetings and publicity – and, perhaps most importantly of all, decide whether they would stand as an independent or seek the nomination of one of the main, male-oriented political parties of the day: Conservative, Liberal or Labour.

Of the 17 women who stood as parliamentary candidates contesting 706 seats, only nine were adopted by the three main political parties. Christabel Pankhurst was the most well-known, but she stood for the Women’s Party, an organisation that she and her mother had founded in 1917. Christabel was the only woman candidate to receive the support of the coalition government, but lost out to her Labour rival by just 775 votes.

Only one woman was elected to parliament in 1918 – Constance Markievicz. But, as a member of Sinn Fein, she refused to swear allegiance to the British crown and never took her seat in the Commons.

June Purvis is professor of women’s and gender history at the University of Portsmouth

500,000: The estimated number of German civilian deaths from strategic bombing during the Second World War

The Blitz was the biggest thing to happen to Britain during the Second World War, and in many ways has come to define the whole of Britain’s experience of war on the home front. But what many people tend to overlook is that, inflicting 50,000 deaths, strategic bombings on Britain by German aircraft killed around a tenth of the number of those who died in similar attacks on Germany. Many of these attacks were carried out by Britain’s Bomber Command, which itself lost some 50,000 crew in the conflict.

The story of Britain during the Second World War needs to be less fixated on the Blitz, and recognise that Britain was itself the perpetrator of far heavier bombing raids on Germany. This was not an aberration, or a response to the Blitz, but rather a long-standing policy of the British state to use machines to wreck the German war economy.

David Edgerton is professor of modern British history at King’s College London

1,138: The number of London children recorded as dying of “teeth” in 1685

This statistic is taken from a 1685 London Bill of Mortality, which listed causes of death in London parishes. Poor women called ‘searchers’ were responsible for collecting the data; they were paid small sums to knock on doors to find out causes of death. Searchers were widely feared because they were associated with infection.

The diseases listed are bizarre: they include things like “frighted”, “suddenly” and “teeth”. The latter was short for “the breeding of teeth” – or teething as we would know it today. It was considered a major cause of infant disease and death in the early modern period: in 1664 the physician J.S. declared that teething “is alwayes dangerous by reason of the grievous Symptomes it produces, as Convulsions, Feavers, and other evils”.

But how did teething cause disease? It was believed that living beings were made up of special substances called humours, which contained different amounts of heat and moisture. When the humours were balanced, the body was healthy, but when they became imbalanced, disease resulted. Teething was dangerous because it caused “sharp Pain like the pricking of needles”, which in turn generated “great heat”, and heat brought diseases caused by hot humours, such as fevers. In childhood, bodies were especially warm; ageing was deemed a cooling process. Thus, any extra warmth in children was believed to spell trouble health-wise.

Doctors and parents went to great lengths to mitigate the hazards of teething. The most popular treatment was to “annoint the gummes with the braynes of a hare”. The midwifery expert François Mauriceau suggested giving children “a little stick of Liquorish to chomp on”, or “a Silver Coral, furnish’d with small Bells”, to “divert the Child from the Pain”. More extreme measures included cutting the gums with a lancet, or hanging a “Viper’s Tooth about the child’s Neck”, which by a “certayne hidden propertie, have vertue to ease the payne”.

Dr Hannah Newton is author of The Sick Child in Early Modern England, 1580–1720 (Oxford University Press, 2012)

Illustrations by James Albon.

4: The number of years' wages that a pound of wool – twice dyed in best quality Tyrian purple – would cost a Roman soldier during the first century AD

Since c1500 BC, purple – a dye produced from the gland secretions of types of shellfish – was the colour of kings, priests, magistrates and emperors, with the highest quality dye originating in Tyre, in ancient Phoenicia (now modern Lebanon).

Its cost was phenomenal. In the first century AD, a pound of wool, twice dyed in best quality Tyrian purple, cost around 1,000 denarii – more than four times the annual wage of a Roman soldier. The AD 301 Edict of Diocletian (also know as the Edict of Maximum Prices), which attempted to control runaway inflation in the empire, lists the most expensive dyed silk as costing 150,000 denarii per pound! Meanwhile the, admittedly satirical, poet Martial claimed that a praetor’s purple cloak actually cost 100 times more than a soldier’s pay.

The reasons behind the astronomical cost lie in the obtaining of the dye itself. This procedure involved a lengthy process of fishing – using wicker traps primed with bait – followed by the extraction of minute quantities of the dye by a long, laborious and smelly process from thousands of shellfish. Pliny the Elder explained the process and gave production statistics which indicate the vast number of shells required.

Pliny stated that if a mollusc gland weighed a gram (in modern weights), more than 3.5m molluscs would produce just 500 pounds of dye. Pliny the Elder was not exaggerating. In modern times, Tyrian purple has been recreated, at great expense. When the German chemist Paul Friedander tried to recreate the colour in 1909, he needed 12,000 molluscs to produce just 1.4 ounces of dye, enough to colour a handkerchief. In 2000, a gram of Tyrian purple, made from 10,000 molluscs according to the original formula, cost 2,000 euros. Peter Jones is author of Veni, Vidi, Vici (Atlantic Books, 2013)

10 million: The number of fleeces exported annually from England by c1300

England has often been referred to as the Australia of the Middle Ages, a reference to its booming wool trade (something that Australia experienced in the 19th century). By the 14th century, English farmers had developed breeds of sheep that produced fleeces of varying weight and quality, some of which were among the best in Europe.

English wool was widely sought after by the cloth-makers of Flanders and Italy who needed fine wool to produce the rich scarlet cloths worn by kings, nobles and bishops. The 14th century had seen a huge growth in the cloth trade, particularly in Ypres, Ghent and Bruges.

To keep up with the high demand, English wool producers expanded their flocks, often going to great trouble to keep them from harm. Many kept their sheep on hill pastures during the summer, moving them to sheltered valleys in the winter. Others built sheep houses or sheepcotes where the animals could shelter in the worst weather and where food, such as peas in straw, was kept.

It is often assumed that monasteries such as Fountains Abbey in North Yorkshire, which kept thousands of sheep, met Europe’s increasing demand for wool, but in fact the combined flocks of peasants, each of whom kept 30–50 animals, outnumbered those of the great estates. To gather the fleeces of these scattered flocks needed organisation – a role that was filled by entrepreneurs, woolmen or woolmongers who bought the wool and sent it to the ports. Some of the big producers – monasteries and lay landlords – often acted as middlemen, collecting the local peasant wool and sending it with their own.

Finances, too, were complicated, and there was much use of credit during the period. An Italian or Flemish merchant would often advance money to a producer, such as a monastery, on the condition that he would buy their wool, sometimes quite cheaply. These contracts usually stretched into the future, so that a monastery might have sold its wool four years in advance.

Chris Dyer is emeritus professor of regional and local history at the University of Leicester

25: The percentage of English men believed to have served in arms for king or parliament at one time or another during the Civil War

The Civil War of the 17th century saw huge numbers of men leave their towns and villages to go and fight, as England, Scotland and Ireland were torn apart by the bitter conflict between the crown and parliament. The historian Charles Carlton has calculated that, proportionately, more of the English population died in the Civil War than in the First World War, and some 25 per cent of English men are thought to have served in arms for king or parliament at one time or another.

The village of Myddle in Shropshire is the only parish in England for which we know exactly how many people went to war. This is thanks to the writings of yeoman Richard Gough, whose History of Myddle, written between 1700 and 1706, tells us that “out of these three towns – that’s to say the hamlets of Myddle parish – of Myddle, Marton and Newton, there went no less than 20 men, of which number 13 were killed in the wars...”

Gough then proceeds to name the Myddle men who went to fight, along with their occupations and whether they lived or died. “Richard Chalenor of Myddle”, he writes, “being a big lad went to Shrewsbury and there listed, and went to Edgehill Fight which was on October 23rd 1642, and was never heard of afterwards in this country...”

The experience of Myddle in the Civil War is by no means unique: it is remarkable simply for the information recorded by Gough. What’s more, his description of one John Mould – who “was shot through the leg with a musket bullet which broke the master bone of his leg” so that it remained “very crooked as long as he lived” – reminds us that, just as in modern wars, huge numbers of men returned to their daily lives physically scarred by the events of the Civil War.

In the wake of the conflict, parliament, which was now in power, provided pensions for wounded parliamentarian soldiers, but offered nothing for those who had fought for the king. In 1660, however, when the monarchy was restored in the form of Charles II, the situation was turned on its head and injured royalists received financial help. Others had to rely on the assistance of their charitable neighbours.

Gough’s writings give historians a wonderful insight into the lives of ordinary soldiers in an era that is so often recorded by the gentry alone. And, to quote Gough himself, who was a young boy during the Civil War: “If so many died out of these three [hamlets], we may reasonably guess that many thousands died in England in that war.” Gough’s History of Myddle is a fitting tribute to those men.

Professor Mark Stoyle is author of The Black Legend of Prince Rupert’s Dog: Witchcraft and Propaganda during the English Civil War (Exeter, 2011)

6: The life expectancy in weeks for newly arrived horses in South Africa during the Anglo-Boer War

Horses played an essential role in the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902), but paid a terrible price: of the 518,704 horses and 150,781 mules and donkeys sent to British forces in South Africa during the conflict, around two thirds (347,007 horses, 53,339 mules and donkeys) never made it home.

At the start of the war, British units travelled from a northern hemisphere winter to a South African summer, meaning that cavalry horses still had their winter coats and suffered severely from the heat. What’s more, the animals endured a long sea voyage of up to six weeks before they even reached South Africa. On arrival, horses were often given no time to recover from the voyage or acclimatise to South African conditions; instead they were rushed into action right away. What’s more, some 13,144 horses and 2,816 mules and donkeys were lost on the outward voyage.

The constant demand for fresh animals meant that additional horses had to be imported but, in contrast to the ponies of the Boers, these imported horses could not eat South African foliage. It proved almost impossible to provide enough food for the animals, especially as Boer guerrillas constantly attacked British supply lines.

After the war, cavalry officer Michael Rimington recalled that the process of bringing animals to the front was “thirty days’ voyage, followed by a five or six days’ railway journey, then semi-starvation at the end of a line of communication, then some quick work followed by two or three days’ total starvation, then more work...”. Ignorance in horse care did not help either: one newly arrived soldier asked Rimington whether he should feed his horse beef or mutton, and the animals were often ridden until they simply collapsed. Little surprise, then, that the average life expectancy of a newly arrived horse in South Africa was just six weeks.

Dr Spencer Jones is author of Stemming the Tide: Officers and Leadership in the British Expeditionary Force 1914 (Helion & Co, 2013)

$1,000: The price per ounce that the US government was paying for penicillin in 1943

In 1940, a team of scientists, led by pharmacologist Howard Florey, discovered the means of extracting penicillin from the very dilute solution produced by penicillium mould. After proving that the substance could cure infections in mice, the Oxford team tested penicillin on human patients – with remarkable results.

But despite taking a small sample of the mould to America and discussing production methods with the US government laboratory and several US companies, by 1943, penicillin was being produced at scarcely more than the laboratory scale previously seen at Oxford.

After testing the substance on patients, the US government purchased penicillin from its manufacturers at a price of $200 for a million units. This was equivalent to $1,000 an ounce at a time when gold cost just $35 an ounce.

The big breakthrough for the drug came with developments in manufacturing techniques, which saw pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer producing penicillin on a massive scale in huge vats. This meant that a single tank of 10,000 gallons could produce the equivalent amount of penicillin as would fill 60,000–70,000 two-litre bottles. The impact of this engineering triumph was intensified by the discovery in 1943 of a new strain of penicillium mould that was much more suitable for growing in the deep vats than the original British strain. This new strain was first found on a melon in Peoria, Illinois, by a technician who later came to be known as Moldy Mary.

By 1945, the American pharmaceutical company Merck was selling penicillin at $6,000 per billion units at a time when penicillin in Europe was still scarce. Three years later, the price had halved and Procaine penicillin, which was metabolised more slowly (meaning fewer injections), had been introduced.

Although two large processing plants were built in Britain after the Second World War, demand for penicillin was so great and so unexpected that its cost – and that of other new drugs including streptomycin and cortisone – forced the new NHS to charge for medicines.

Robert Bud is keeper of science and medicine at the Science Museum, London

17: The number of women candidates who stood for election to parliament in 1918

Thousands of women during the Edwardian era became politicised during the campaign for the parliamentary vote, so at first glance it may seem surprising that only 17 women stood for election in 1918 – the first in which women could participate in the representative process, both as voters and as parliamentary candidates.

The Representation of the People Act, which received Royal Assent on 6 February 1918, was unclear as to whether women could stand as parliamentary candidates and opinions on the issue were divided. When the coalition government rushed through the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Bill, which became law on 21 November 1918, a general election for 14 December had already been announced, with 4 December given as the date when nominations for parliamentary candidates had to be received. This gave women who wished to stand for election just three weeks in which to find a seat, enter a nomination, choose an election agent, draw up election policy, secure the support of unpaid helpers, raise funds, organise meetings and publicity – and, perhaps most importantly of all, decide whether they would stand as an independent or seek the nomination of one of the main, male-oriented political parties of the day: Conservative, Liberal or Labour.

Of the 17 women who stood as parliamentary candidates contesting 706 seats, only nine were adopted by the three main political parties. Christabel Pankhurst was the most well-known, but she stood for the Women’s Party, an organisation that she and her mother had founded in 1917. Christabel was the only woman candidate to receive the support of the coalition government, but lost out to her Labour rival by just 775 votes.

Only one woman was elected to parliament in 1918 – Constance Markievicz. But, as a member of Sinn Fein, she refused to swear allegiance to the British crown and never took her seat in the Commons.

June Purvis is professor of women’s and gender history at the University of Portsmouth

500,000: The estimated number of German civilian deaths from strategic bombing during the Second World War

The Blitz was the biggest thing to happen to Britain during the Second World War, and in many ways has come to define the whole of Britain’s experience of war on the home front. But what many people tend to overlook is that, inflicting 50,000 deaths, strategic bombings on Britain by German aircraft killed around a tenth of the number of those who died in similar attacks on Germany. Many of these attacks were carried out by Britain’s Bomber Command, which itself lost some 50,000 crew in the conflict.

The story of Britain during the Second World War needs to be less fixated on the Blitz, and recognise that Britain was itself the perpetrator of far heavier bombing raids on Germany. This was not an aberration, or a response to the Blitz, but rather a long-standing policy of the British state to use machines to wreck the German war economy.

David Edgerton is professor of modern British history at King’s College London

1,138: The number of London children recorded as dying of “teeth” in 1685

This statistic is taken from a 1685 London Bill of Mortality, which listed causes of death in London parishes. Poor women called ‘searchers’ were responsible for collecting the data; they were paid small sums to knock on doors to find out causes of death. Searchers were widely feared because they were associated with infection.

The diseases listed are bizarre: they include things like “frighted”, “suddenly” and “teeth”. The latter was short for “the breeding of teeth” – or teething as we would know it today. It was considered a major cause of infant disease and death in the early modern period: in 1664 the physician J.S. declared that teething “is alwayes dangerous by reason of the grievous Symptomes it produces, as Convulsions, Feavers, and other evils”.

But how did teething cause disease? It was believed that living beings were made up of special substances called humours, which contained different amounts of heat and moisture. When the humours were balanced, the body was healthy, but when they became imbalanced, disease resulted. Teething was dangerous because it caused “sharp Pain like the pricking of needles”, which in turn generated “great heat”, and heat brought diseases caused by hot humours, such as fevers. In childhood, bodies were especially warm; ageing was deemed a cooling process. Thus, any extra warmth in children was believed to spell trouble health-wise.

Doctors and parents went to great lengths to mitigate the hazards of teething. The most popular treatment was to “annoint the gummes with the braynes of a hare”. The midwifery expert François Mauriceau suggested giving children “a little stick of Liquorish to chomp on”, or “a Silver Coral, furnish’d with small Bells”, to “divert the Child from the Pain”. More extreme measures included cutting the gums with a lancet, or hanging a “Viper’s Tooth about the child’s Neck”, which by a “certayne hidden propertie, have vertue to ease the payne”.

Dr Hannah Newton is author of The Sick Child in Early Modern England, 1580–1720 (Oxford University Press, 2012)

Published on February 07, 2017 02:30

February 6, 2017

5 things you (probably) didn’t know about the Dark Ages

History Extra

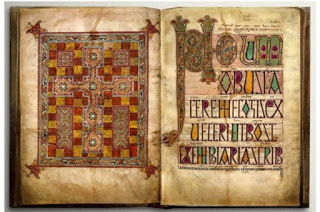

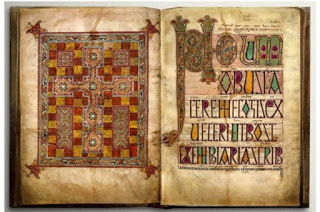

The Lindisfarne Gospels, carpet page and incipit, c700-20. (British Library)

1. Why is the period known as ‘dark’?

The term ‘Dark Age’ was used by the Italian scholar and poet Petrarch in the 1330s to describe the decline in later Latin literature following the collapse of the Western Roman empire. In the 20th century, scholars used the term more specifically in relation to the 5th-10th centuries, but now it is largely seen as a derogatory term, concerned with contrasting periods of perceived enlightenment with cultural ignorance. A very quick glance at the remarkable manuscripts, metalwork, texts, buildings and individuals that saturate the early medieval period reveals that ‘Dark Age’ is now very much an out-of-date term. It’s best used as a point of reference against which to show how vibrant the time in fact was.

Gold, garnet and glass shoulder clasps from the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial, c 625AD. (British Museum)

2. It was religiously diverse

The early medieval period was characterised by widespread adherence to Christianity. However, there was a great deal of religious variety, and even the Christian church itself was a diverse and complicated entity. In the north, Scandinavia and parts of Germany adhered to Germanic paganism, with Iceland converting to Christianity in 1000 AD. Folk religious practices continued. Late in the 8th century, an Anglo-Saxon monk called Alcuin questioned why heroic legend still fascinated Christians, asking: “What has Ingeld to do with Christ?” Within the church there were many lines of divisions. For example, Monophysitism divided society and the church, arguing that Jesus had just one nature, rather than two: human and divine, which caused division to the level of emperors, states and nations.

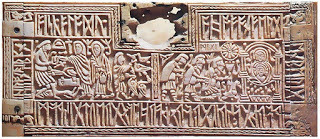

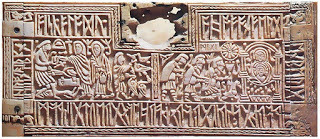

The Franks Casket, carved on whale bone, with runic poetry and showing scenes of the nativity and Weland’s revenge, c700. (British Museum)

3. It was not a time of illiteracy and ignorance

The connection between illiteracy and ignorance is a relatively modern phenomenon. For most of the medieval period and beyond, the majority of information was transmitted orally and retained through memory. Societies such as that of the early Anglo-Saxons could recall everything from land deeds, marital associations and epic poetry. The ‘scop’ or minstrel could recite a single epic over many days, indicating hugely sophisticated mental retention. With the establishment of monasteries, literacy was largely confined within their walls. Yet in places like the holy community at Lindisfarne, the monks were able to create sophisticated theological texts, and extraordinary manuscripts.

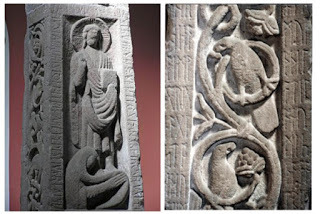

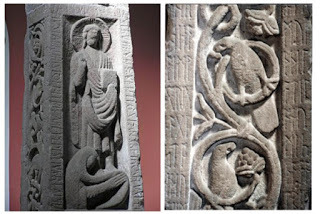

Panels from the Ruthwell Cross showing Jesus with Mary Magdalene, and runic passages from ‘The Dream of the Rood’, 8th century, Ruthwell Church, Dumfriesshire.

4. This was a high point for British art

Far from a ‘dark’ time when all the lights went out, the early medieval period saw the creation of some of the nation’s finest artworks. The discovery of the Sutton Hoo ship burial on the eve of the Second World War redefined how the Anglo-Saxons were perceived. The incredible beauty of the jewellery, together with the sophisticated trade links indicated by the array of finds, revealed a court that was well connected and influential. After the arrival of Christian missionaries in 597 AD, Anglo-Saxons had to get to grips with completely new technologies. Although having never made books before, within a generation or two they were creating remarkable manuscripts such as the Lindisfarne Gospels and the earliest surviving single copy of the Vulgate Bible, the Codex Amiatinus. They also invented a new form of art: the standing stone high cross. Arguably the most expressive is the Ruthwell Cross, where the cross itself speaks of Christ’s passion, through the runic poetry carved on its sides.

Finds from the Staffordshire Hoard which was discovered in 2009, the largest hoard of Anglo-Saxon gold and silver metalwork yet found. (Birmingham Museum)

5. There is still so much to discover

With many periods in history, it can be difficult to find something new to explore or write about. Not so with the early medieval period. There are relatively few early medievalists, and a wealth of research still to be done. What’s more, advances in archaeology are only recently bringing information to light about how people in this period lived. When societies build more in timber than in stone, it can be hard to find evidence in the archaeological record, but more is coming to light now than ever before. There are the surprise discoveries: manuscripts long hidden in archives, hoards concealed in fields, references only recently translated. There is still so much to be done, and this is a rich and rewarding period to immerse yourself in.

Dr Janina Ramirez is a British art and cultural historian and television presenter.

The Lindisfarne Gospels, carpet page and incipit, c700-20. (British Library)

1. Why is the period known as ‘dark’?

The term ‘Dark Age’ was used by the Italian scholar and poet Petrarch in the 1330s to describe the decline in later Latin literature following the collapse of the Western Roman empire. In the 20th century, scholars used the term more specifically in relation to the 5th-10th centuries, but now it is largely seen as a derogatory term, concerned with contrasting periods of perceived enlightenment with cultural ignorance. A very quick glance at the remarkable manuscripts, metalwork, texts, buildings and individuals that saturate the early medieval period reveals that ‘Dark Age’ is now very much an out-of-date term. It’s best used as a point of reference against which to show how vibrant the time in fact was.

Gold, garnet and glass shoulder clasps from the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial, c 625AD. (British Museum)

2. It was religiously diverse

The early medieval period was characterised by widespread adherence to Christianity. However, there was a great deal of religious variety, and even the Christian church itself was a diverse and complicated entity. In the north, Scandinavia and parts of Germany adhered to Germanic paganism, with Iceland converting to Christianity in 1000 AD. Folk religious practices continued. Late in the 8th century, an Anglo-Saxon monk called Alcuin questioned why heroic legend still fascinated Christians, asking: “What has Ingeld to do with Christ?” Within the church there were many lines of divisions. For example, Monophysitism divided society and the church, arguing that Jesus had just one nature, rather than two: human and divine, which caused division to the level of emperors, states and nations.

The Franks Casket, carved on whale bone, with runic poetry and showing scenes of the nativity and Weland’s revenge, c700. (British Museum)

3. It was not a time of illiteracy and ignorance

The connection between illiteracy and ignorance is a relatively modern phenomenon. For most of the medieval period and beyond, the majority of information was transmitted orally and retained through memory. Societies such as that of the early Anglo-Saxons could recall everything from land deeds, marital associations and epic poetry. The ‘scop’ or minstrel could recite a single epic over many days, indicating hugely sophisticated mental retention. With the establishment of monasteries, literacy was largely confined within their walls. Yet in places like the holy community at Lindisfarne, the monks were able to create sophisticated theological texts, and extraordinary manuscripts.

Panels from the Ruthwell Cross showing Jesus with Mary Magdalene, and runic passages from ‘The Dream of the Rood’, 8th century, Ruthwell Church, Dumfriesshire.

4. This was a high point for British art

Far from a ‘dark’ time when all the lights went out, the early medieval period saw the creation of some of the nation’s finest artworks. The discovery of the Sutton Hoo ship burial on the eve of the Second World War redefined how the Anglo-Saxons were perceived. The incredible beauty of the jewellery, together with the sophisticated trade links indicated by the array of finds, revealed a court that was well connected and influential. After the arrival of Christian missionaries in 597 AD, Anglo-Saxons had to get to grips with completely new technologies. Although having never made books before, within a generation or two they were creating remarkable manuscripts such as the Lindisfarne Gospels and the earliest surviving single copy of the Vulgate Bible, the Codex Amiatinus. They also invented a new form of art: the standing stone high cross. Arguably the most expressive is the Ruthwell Cross, where the cross itself speaks of Christ’s passion, through the runic poetry carved on its sides.

Finds from the Staffordshire Hoard which was discovered in 2009, the largest hoard of Anglo-Saxon gold and silver metalwork yet found. (Birmingham Museum)

5. There is still so much to discover

With many periods in history, it can be difficult to find something new to explore or write about. Not so with the early medieval period. There are relatively few early medievalists, and a wealth of research still to be done. What’s more, advances in archaeology are only recently bringing information to light about how people in this period lived. When societies build more in timber than in stone, it can be hard to find evidence in the archaeological record, but more is coming to light now than ever before. There are the surprise discoveries: manuscripts long hidden in archives, hoards concealed in fields, references only recently translated. There is still so much to be done, and this is a rich and rewarding period to immerse yourself in.

Dr Janina Ramirez is a British art and cultural historian and television presenter.

Published on February 06, 2017 02:30

February 5, 2017

Queen Victoria's 50 inch drawers... and other items from the royal wardrobe with Lucy Worsley

History Extra

Lucy Worsley with George III's waistcoat. (BBC Silver River)

Clothes for a ‘mad’ king, George III Among the most poignant surviving garments in Historic Royal Palaces’ bizarre and brilliant Royal Ceremonial Dress Collection are some of the clothes made for George III (1738–1820) to wear during his episode of so-called ‘madness’.

Today, some people believe that it was bipolar disorder; others that it was the painful physical illness porphyria. Either way, there were long periods when the king was unable to look after himself. He was fed from a jug with a spout, and helped into his clothes by his valet.

The ‘mad’ king’s shirts have extra-wide shoulders so that servants could lift them over his head, and the waistcoat that I’m pictured with above has sleeves enlarged so that his arms could be poked in more easily. The waistcoat also bears orange-coloured stains of food, drink or dribble. When this particular item was sent by a palace servant to the souvenir-hunter who asked for it, it was accompanied by apologies. It was the only item available, the servant said – the rest of the king’s clothes were just too soiled.

George’s periods of absence from politics, through illness, caused dismay and confusion, especially when his son the Prince Regent tried to make political capital out of them. But the sheer length of his reign brought stability, and there’s no doubt that George III was a conscientious and well-intentioned king.

Pants belonging to a queen who ate “a little too much”

Queen Victoria (1819–1901) was a wand of a girl when she came to the throne at 18, with a waist measuring 22 inches. Yet she always struggled with her appetite and, as the capacious drawers pictured below show, this was to catch up with her in later life.

“She is incredibly precocious for her age and very comical,” said her grandmother. “I have never seen a more alert and forthcoming child.” However Victoria was also described as a “little princess [who] eats a little too much and almost always a little too fast”.

In 1861 came the great catastrophe of her life, the death of her husband, Albert. With this, Victoria lost the only person who’d been able to call her ‘Victoria’ instead of ‘Your Majesty’, and – crucially – the only person who could tell her ‘no’.

During the following decades, Victoria became what we would today call clinically depressed. She lost interest in life, became reclusive, and comforted herself with food. She was either indulged by her doctors (frightened of her, like everyone else) or else bullied by the politicians who wanted her to get on with being queen again.

As a widow, Victoria refused to wear any colour other than black for her bodices and skirts. These were offset only by a white widow’s cap, and white underwear threaded with black ribbons. A pair of her drawers, kept at Kensington Palace, has a waist measurement even more impressive than George IV’s, considering their relative height: 50 inches!

Queen Victoria's chemise and split drawers, which measured an ''impressive'' 50 inches. (Historic Royal Palaces)

The enormous breeches of George IV Henry VIII was, notoriously, 54 inches around the waist later on in life, and George IV (1762–1830) equalled his record. George IV’s greatest problem seems to have been mental: he lacked the toughness to stand up to a life lived in public. He wasn’t untalented – he had terrific visual flair, and his wife said he would have made a great hairdresser. It was just a shame he had to be king.

As well as over-eating, George IV became an alcoholic, and an addict of opium in the form of laudanum. The Duke of Wellington described a tremendous meal eaten later on in the king’s life: “What do you think of his breakfast yesterday? A Pidgeon and Beef Steak Pye of which he ate two Pigeons and three Beefsteaks, Three parts of a bottle of Mozelle, a Glass of Dry Champagne, two Glasses of Port [and] a Glass of Brandy.”

The failure of George’s breeches to fasten formed a key part of his image in the cutting caricatures produced by Cruikshank and others, which caused lasting damage to his reputation. George tried to reduce his stomach with what was called his ‘belt’, a kind of simple corset. A paper pattern for the original still survives at the Museum of London, and from it, a replica has been made for Brighton’s Royal Pavilion.

When George was due to be painted by Sir David Wilkie, the portraitist was kept waiting for some hours while the king’s servants trussed him into his undergarments. When the king finally appeared, Wilkie said he looked like “a great sausage stuffed into the covering”.

George IV’s declining health made him increasingly reclusive. On the one hand, his failure to act on the terrible social problems caused by the industrial revolution brought him vilification. On the other, his relative invisibility meant that no one actually took the trouble to bring him down: unlike the French monarchy, the British one survived intact.

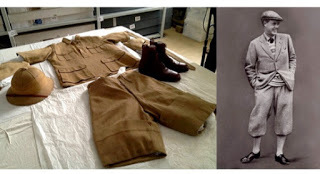

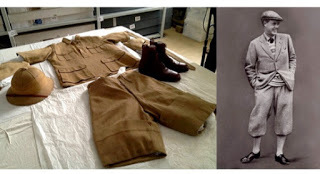

The future Edward VIII’s flashy safari suit

George V, a monarch devoted to decorum and duty, was a stickler for correct dress. From early on, the flair for fashion exhibited by his eldest son, the future Edward VIII (1894–1972), caused trouble between them, and it presaged disaster of a far more serious sort.

George V disliked Edward’s turned-up trousers, and his loud, hounds-tooth tweeds. He thought it regrettable that Edward would come to tea in his riding clothes, and fail to wear gloves at a ball. The safari suit is a typical outfit of Edward’s. Self-designed, it has adjustable arms and legs that could be altered for whichever leisure pursuit he wished to follow on any particular day of a holiday in exotic Africa.

Edward’s youthful, bareheaded style found him fame and popularity with young people all over the world. But there was something solid in George V’s misgivings. Edward’s flashy, informal clothes hinted that he wasn’t looking forward to wearing a crown, and in 1936, he finally refused to do so when he abdicated from the throne.

Left image: The future Edward VIII's safari suit, with arms and legs that could be altered for different leisure pursuits. (BBC Silver River) Right image: Edward sporting a casual tweed suit, which was guaranteed to raise his father's ire, c1920. (Mary Evans)

William III’s vest and socks With his small stature and twisted spine, William III and II (1650–1702) wasn’t a king in the charismatic, physically impressive mould of Henry VIII. He rebuilt the countryside palace at Hampton Court partly because of his asthma: he needed fresh air because he couldn’t breathe in the damp, smoky, urban palace of Whitehall. This is all evident from his underwear, which looks like it was intended for a 12-year-old. These are tiny clothes for a tiny king, including green royal socks with clocks topped by a little crown.

William had deposed his father-in-law, James II and VII, to become joint ruler with his wife (and James’s daughter) Mary II. And in fact he was the ideal king to make a complicated, ambivalent and lashed-up succession work. William compensated for his physical weakness through political nous and the pragmatism that he’d developed during earlier years as a leader of the various, and sometimes unruly, states of the Netherlands.

With his hooked nose and opaque personality, William’s new British subjects found him distinctly unregal: hard to read, as well as physically puny. But today his achievements in seizing a throne with little bloodshed and achieving stability make him appear an exceptionally able king.

Lucy Worsley is a writer, presenter and chief curator of the Historic Royal Palaces.

Lucy Worsley with George III's waistcoat. (BBC Silver River)

Clothes for a ‘mad’ king, George III Among the most poignant surviving garments in Historic Royal Palaces’ bizarre and brilliant Royal Ceremonial Dress Collection are some of the clothes made for George III (1738–1820) to wear during his episode of so-called ‘madness’.

Today, some people believe that it was bipolar disorder; others that it was the painful physical illness porphyria. Either way, there were long periods when the king was unable to look after himself. He was fed from a jug with a spout, and helped into his clothes by his valet.

The ‘mad’ king’s shirts have extra-wide shoulders so that servants could lift them over his head, and the waistcoat that I’m pictured with above has sleeves enlarged so that his arms could be poked in more easily. The waistcoat also bears orange-coloured stains of food, drink or dribble. When this particular item was sent by a palace servant to the souvenir-hunter who asked for it, it was accompanied by apologies. It was the only item available, the servant said – the rest of the king’s clothes were just too soiled.

George’s periods of absence from politics, through illness, caused dismay and confusion, especially when his son the Prince Regent tried to make political capital out of them. But the sheer length of his reign brought stability, and there’s no doubt that George III was a conscientious and well-intentioned king.

Pants belonging to a queen who ate “a little too much”

Queen Victoria (1819–1901) was a wand of a girl when she came to the throne at 18, with a waist measuring 22 inches. Yet she always struggled with her appetite and, as the capacious drawers pictured below show, this was to catch up with her in later life.

“She is incredibly precocious for her age and very comical,” said her grandmother. “I have never seen a more alert and forthcoming child.” However Victoria was also described as a “little princess [who] eats a little too much and almost always a little too fast”.

In 1861 came the great catastrophe of her life, the death of her husband, Albert. With this, Victoria lost the only person who’d been able to call her ‘Victoria’ instead of ‘Your Majesty’, and – crucially – the only person who could tell her ‘no’.

During the following decades, Victoria became what we would today call clinically depressed. She lost interest in life, became reclusive, and comforted herself with food. She was either indulged by her doctors (frightened of her, like everyone else) or else bullied by the politicians who wanted her to get on with being queen again.

As a widow, Victoria refused to wear any colour other than black for her bodices and skirts. These were offset only by a white widow’s cap, and white underwear threaded with black ribbons. A pair of her drawers, kept at Kensington Palace, has a waist measurement even more impressive than George IV’s, considering their relative height: 50 inches!

Queen Victoria's chemise and split drawers, which measured an ''impressive'' 50 inches. (Historic Royal Palaces)

The enormous breeches of George IV Henry VIII was, notoriously, 54 inches around the waist later on in life, and George IV (1762–1830) equalled his record. George IV’s greatest problem seems to have been mental: he lacked the toughness to stand up to a life lived in public. He wasn’t untalented – he had terrific visual flair, and his wife said he would have made a great hairdresser. It was just a shame he had to be king.

As well as over-eating, George IV became an alcoholic, and an addict of opium in the form of laudanum. The Duke of Wellington described a tremendous meal eaten later on in the king’s life: “What do you think of his breakfast yesterday? A Pidgeon and Beef Steak Pye of which he ate two Pigeons and three Beefsteaks, Three parts of a bottle of Mozelle, a Glass of Dry Champagne, two Glasses of Port [and] a Glass of Brandy.”

The failure of George’s breeches to fasten formed a key part of his image in the cutting caricatures produced by Cruikshank and others, which caused lasting damage to his reputation. George tried to reduce his stomach with what was called his ‘belt’, a kind of simple corset. A paper pattern for the original still survives at the Museum of London, and from it, a replica has been made for Brighton’s Royal Pavilion.

When George was due to be painted by Sir David Wilkie, the portraitist was kept waiting for some hours while the king’s servants trussed him into his undergarments. When the king finally appeared, Wilkie said he looked like “a great sausage stuffed into the covering”.

George IV’s declining health made him increasingly reclusive. On the one hand, his failure to act on the terrible social problems caused by the industrial revolution brought him vilification. On the other, his relative invisibility meant that no one actually took the trouble to bring him down: unlike the French monarchy, the British one survived intact.

The future Edward VIII’s flashy safari suit

George V, a monarch devoted to decorum and duty, was a stickler for correct dress. From early on, the flair for fashion exhibited by his eldest son, the future Edward VIII (1894–1972), caused trouble between them, and it presaged disaster of a far more serious sort.

George V disliked Edward’s turned-up trousers, and his loud, hounds-tooth tweeds. He thought it regrettable that Edward would come to tea in his riding clothes, and fail to wear gloves at a ball. The safari suit is a typical outfit of Edward’s. Self-designed, it has adjustable arms and legs that could be altered for whichever leisure pursuit he wished to follow on any particular day of a holiday in exotic Africa.

Edward’s youthful, bareheaded style found him fame and popularity with young people all over the world. But there was something solid in George V’s misgivings. Edward’s flashy, informal clothes hinted that he wasn’t looking forward to wearing a crown, and in 1936, he finally refused to do so when he abdicated from the throne.

Left image: The future Edward VIII's safari suit, with arms and legs that could be altered for different leisure pursuits. (BBC Silver River) Right image: Edward sporting a casual tweed suit, which was guaranteed to raise his father's ire, c1920. (Mary Evans)

William III’s vest and socks With his small stature and twisted spine, William III and II (1650–1702) wasn’t a king in the charismatic, physically impressive mould of Henry VIII. He rebuilt the countryside palace at Hampton Court partly because of his asthma: he needed fresh air because he couldn’t breathe in the damp, smoky, urban palace of Whitehall. This is all evident from his underwear, which looks like it was intended for a 12-year-old. These are tiny clothes for a tiny king, including green royal socks with clocks topped by a little crown.

William had deposed his father-in-law, James II and VII, to become joint ruler with his wife (and James’s daughter) Mary II. And in fact he was the ideal king to make a complicated, ambivalent and lashed-up succession work. William compensated for his physical weakness through political nous and the pragmatism that he’d developed during earlier years as a leader of the various, and sometimes unruly, states of the Netherlands.

With his hooked nose and opaque personality, William’s new British subjects found him distinctly unregal: hard to read, as well as physically puny. But today his achievements in seizing a throne with little bloodshed and achieving stability make him appear an exceptionally able king.

Lucy Worsley is a writer, presenter and chief curator of the Historic Royal Palaces.

Published on February 05, 2017 01:30

February 4, 2017

A murder of crows: 10 collective nouns you didn’t realise originate from the Middle Ages

History Extra

Aesop's fables: The Fox and The Crow. Illustration after 1485 edition printed in Naples by German printers for Francesco del Tuppo. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images

Why are geese in a gaggle? And are crows really murderous? Collective nouns are one of the most charming oddities of the English language, often with seemingly bizarre connections to the groups they identify. But have you ever stopped to wonder where these peculiar terms actually came from?

Many of them were first recorded in the 15th century in publications known as Books of Courtesy – manuals on the various aspects of noble living, designed to prevent young aristocrats from embarrassing themselves by saying the wrong thing at court.

The earliest of these documents to survive to the present day was The Egerton Manuscript, dating from around 1450, which featured a list of 106 collective nouns. Several other manuscripts followed, the most influential of which appeared in 1486 in The Book of St Albans – a treatise on hunting, hawking and heraldry, written mostly in verse and attributed to the nun Dame Juliana Barnes (sometimes written Berners), prioress of the Priory of St Mary of Sopwell, near the town of St Albans.

This list features 164 collective nouns, beginning with those describing the ‘beasts of the chase’, but extending to include a wide range of animals and birds and, intriguingly, an extensive array of human professions and types of person.

Those describing animals and birds have diverse sources of inspiration. Some are named for the characteristic behaviour of the animals (‘a leap of leopards’, ‘a busyness of ferrets’), or by the use they were put to by humans (‘a yoke of oxen’, ‘a burden of mules’). Sometimes they’re given group nouns that describe their young (‘a covert of coots’, ‘a kindle of kittens’), and others by the way they respond when flushed (‘a sord of mallards’, ‘a rout of wolves’).

Many of those describing people and professions go further still in revealing the medieval mindset of their inventors, opening a window into the past from which we can enjoy a fascinating view of the medieval world.

1) “A tabernacle of bakers”

Bread was the mainstay of a medieval peasant’s diet, with meat, fish and dairy produce too expensive to be eaten any more than once or twice a week. Strict laws governing the distribution of bread stated that no baker was allowed to sell his bread from beside his own oven, and must instead purvey his produce from a stall at one of the king’s approved markets.

These small, portable shops were known in Middle English as ‘tabernacula’, which were defined by Dutch lexicographer Junius Hadrianus in his Nomenclature, which was first translated into English in 1585, as ‘little shops made of boards’.

2) “A stalk of foresters” The role of a forester in medieval society was respectable and well paid. Geoffrey Chaucer held the position in the royal forest of North Petherton in Somerset, and records from 1394 show that he was granted an annual pension of £20 by Richard II – a sum that reflected the importance of the role to hunting-mad noblemen.

A forester’s duties included protecting the forest’s stock of game birds, deer and other animals from poachers. From time to time they also stalked criminals, who took to the forests to evade capture.

3) “A melody of harpers”

Depicted in wall paintings in Ancient Egyptian tombs, the harp is one of the oldest musical instruments in the world, and by the medieval period – the age of troubadours and minstrels – was experiencing a surge in popularity.

This was an era defined by its emphasis on knightly tradition, and the harp often accompanied songs about valiant deeds and courtly love. In great demand at the estates of the upper classes, travelling harpists often moved from town to town performing instrumental accompaniment at banquets and recitals of madrigal singing. There were high-born harpists, too: both Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn were keen players.

4) “A sentence of judges”

Up until the 12th century, the law was deeply rooted in the feudal system, whereby the lord of the manor could charge and punish perpetrators of crime – often poaching from his land – as he saw fit. But in 1166, Henry II sought to shift the power away from individual landowners and bring it more directly under his own control.

He established the courts of assizes, where a national bench of judges travelled around the country attending quarterly court sessions. These judges based their decisions on a new set of national laws that were common to all people, which is where we get the term ‘common law’.

Though more egalitarian than the manorial system, assizes judges could be harsh in the sentences they delivered, which ranged from a stint in the stocks to public execution.

5) “A faith of merchants”

Merchants lived outside the rigid structure of feudalism, and their growing success in the 15th century had an enormous impact on the structure of society. They formed guilds of fellow traders, which eventually bought charters directly from the king, allowing the towns to become independent of the lord of the manor. ‘

Faith’ as it is used here was a reference to the trustworthiness of a person, and is meant ironically, since merchants were rarely trusted. Court documents from the time record the various tricks of the trade that were used to con the public, including hiding bad grain under good, and stitching undersized coal sacks to disguise small measures of coal.

All offences were officially punishable by a stint in the pillory, but because the guilds were self-regulated, most perpetrators got off with only a fine – to the inevitable anger of the masses.

6) “An abominable sight of monks” Monks weren’t particularly popular during the 15th century. Bede’s Life of Cuthbert, dated around AD 725, is the story of a party of monks who almost drowned when their boat was caught in a storm on the River Tyne. Cuthbert pleaded with the peasants on the bank for help but “the rustics, turning on him with angry minds and angry mouths, exclaimed, ‘Nobody shall pray for them: May God spare none of them! For they have taken away from men the ancient rites and customs, and how the new ones are to be attended to, nobody knows.’”

By the 15th century this resentment of the trampling of pagan traditions had been exacerbated by a perception of monks as being well fed and comfortable while the general population starved. ‘Abominable’ is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “causing moral revulsion”, which is a fairly accurate description of the reaction this image provoked.

7) “A superfluity of nuns” Superfluity can be interpreted in two ways – the first is as historical fact. There were around 138 nunneries in England between 1270 and 1536, many of which were severely overcrowded. The convent was seen as a natural step for the daughters of the nobility who had passed marriageable age, and lords put pressure on prioresses to accept their daughters even if they were already full.

Alternatively, though, the excess of nuns referred to here could have been a comment on the emerging view among agitators for church reform that the days of the monastery and convent were over. Some 50 years after this noun appeared in print in The Book of St Albans Henry VIII ordered their closure, and the Protestant Reformation was in full swing.

8) “A stud of horses” Horses were at the absolute centre of life in the Middle Ages. Rather than the breeds we’re familiar with today, medieval horses were classified by the role they played in society. There were destriers, stallions that were used as warhorses by royalty and lords; palfreys, bred for general-purpose riding, war and travel, usually owned by the wealthy; coursers, steady cavalry horses; and rouncies – common-grade hack horses of no special breeding.

During the Middle Ages, monasteries often ran breeding centres called stud farms – ‘stud’ has its roots in the German word ‘Stute’, meaning mare. State stud farms also existed: the first was established under Louis XIV of France in 1665, by which time ‘a stud of horses’ was already established as the proper collective.

9) ‘A pack/cry/kennel of hounds’ Hunting dogs were important members of the medieval household. Every noble family kept kennels for their dogs, and these were looked after by a team of dedicated servants.

‘A cry of hounds’ is thought to derive from the hunting cry that instructs the hounds in their pursuit. The traditional English hunting call ‘Tally Ho!’ is a shortening of ‘Tallio, hoix, hark, forward,’ which, according to an 1801 edition of The Sporting Magazine, is an Anglicized version of the French terms ‘Thia-hilaud’ and ‘a qui forheur’, which appear in La Vénerie by Jacques du Fouilloux, first published at Poitiers in 1561.

This was adapted into English by George Gascoigne under the title The Noble Arte of Venerie, and became one of the pillars of a young gentleman’s hunting education.

10) “A richesse of martens” The European pine marten was considered a top prize for hunters in the Middle Ages. Of all the ‘vermin of the chase’, which included foxes, wild cats, polecats and squirrels, the marten was the most sought after because of its valuable pelt.

Tudor ‘statutes of apparel’ – strict laws governing the amount of money the people could spend on clothing – dictated the colours, cuts and materials that could be worn by each level of society, and stated which furs could be worn by which tier of the aristocracy. Only those of or above the rank of duke, marquise and earl were allowed to wear sable fur, while ermine, the white winter coat of the stoat, which could only be obtained for a few months of the year, was reserved for royalty.

Chloe Rhodes’ An Unkindness of Ravens: A Book of Collective Nouns is published by Michael O'Mara.

Aesop's fables: The Fox and The Crow. Illustration after 1485 edition printed in Naples by German printers for Francesco del Tuppo. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images

Why are geese in a gaggle? And are crows really murderous? Collective nouns are one of the most charming oddities of the English language, often with seemingly bizarre connections to the groups they identify. But have you ever stopped to wonder where these peculiar terms actually came from?

Many of them were first recorded in the 15th century in publications known as Books of Courtesy – manuals on the various aspects of noble living, designed to prevent young aristocrats from embarrassing themselves by saying the wrong thing at court.

The earliest of these documents to survive to the present day was The Egerton Manuscript, dating from around 1450, which featured a list of 106 collective nouns. Several other manuscripts followed, the most influential of which appeared in 1486 in The Book of St Albans – a treatise on hunting, hawking and heraldry, written mostly in verse and attributed to the nun Dame Juliana Barnes (sometimes written Berners), prioress of the Priory of St Mary of Sopwell, near the town of St Albans.

This list features 164 collective nouns, beginning with those describing the ‘beasts of the chase’, but extending to include a wide range of animals and birds and, intriguingly, an extensive array of human professions and types of person.

Those describing animals and birds have diverse sources of inspiration. Some are named for the characteristic behaviour of the animals (‘a leap of leopards’, ‘a busyness of ferrets’), or by the use they were put to by humans (‘a yoke of oxen’, ‘a burden of mules’). Sometimes they’re given group nouns that describe their young (‘a covert of coots’, ‘a kindle of kittens’), and others by the way they respond when flushed (‘a sord of mallards’, ‘a rout of wolves’).

Many of those describing people and professions go further still in revealing the medieval mindset of their inventors, opening a window into the past from which we can enjoy a fascinating view of the medieval world.

1) “A tabernacle of bakers”

Bread was the mainstay of a medieval peasant’s diet, with meat, fish and dairy produce too expensive to be eaten any more than once or twice a week. Strict laws governing the distribution of bread stated that no baker was allowed to sell his bread from beside his own oven, and must instead purvey his produce from a stall at one of the king’s approved markets.

These small, portable shops were known in Middle English as ‘tabernacula’, which were defined by Dutch lexicographer Junius Hadrianus in his Nomenclature, which was first translated into English in 1585, as ‘little shops made of boards’.

2) “A stalk of foresters” The role of a forester in medieval society was respectable and well paid. Geoffrey Chaucer held the position in the royal forest of North Petherton in Somerset, and records from 1394 show that he was granted an annual pension of £20 by Richard II – a sum that reflected the importance of the role to hunting-mad noblemen.

A forester’s duties included protecting the forest’s stock of game birds, deer and other animals from poachers. From time to time they also stalked criminals, who took to the forests to evade capture.

3) “A melody of harpers”

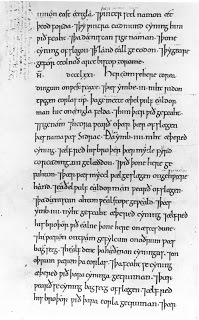

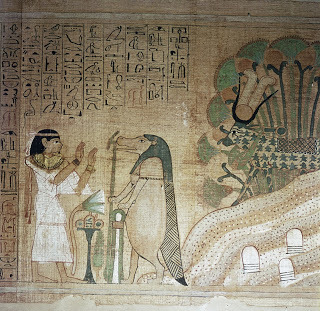

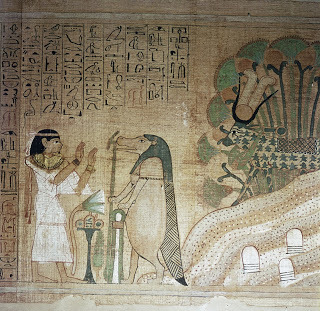

Depicted in wall paintings in Ancient Egyptian tombs, the harp is one of the oldest musical instruments in the world, and by the medieval period – the age of troubadours and minstrels – was experiencing a surge in popularity.

This was an era defined by its emphasis on knightly tradition, and the harp often accompanied songs about valiant deeds and courtly love. In great demand at the estates of the upper classes, travelling harpists often moved from town to town performing instrumental accompaniment at banquets and recitals of madrigal singing. There were high-born harpists, too: both Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn were keen players.

4) “A sentence of judges”

Up until the 12th century, the law was deeply rooted in the feudal system, whereby the lord of the manor could charge and punish perpetrators of crime – often poaching from his land – as he saw fit. But in 1166, Henry II sought to shift the power away from individual landowners and bring it more directly under his own control.

He established the courts of assizes, where a national bench of judges travelled around the country attending quarterly court sessions. These judges based their decisions on a new set of national laws that were common to all people, which is where we get the term ‘common law’.

Though more egalitarian than the manorial system, assizes judges could be harsh in the sentences they delivered, which ranged from a stint in the stocks to public execution.

5) “A faith of merchants”

Merchants lived outside the rigid structure of feudalism, and their growing success in the 15th century had an enormous impact on the structure of society. They formed guilds of fellow traders, which eventually bought charters directly from the king, allowing the towns to become independent of the lord of the manor. ‘

Faith’ as it is used here was a reference to the trustworthiness of a person, and is meant ironically, since merchants were rarely trusted. Court documents from the time record the various tricks of the trade that were used to con the public, including hiding bad grain under good, and stitching undersized coal sacks to disguise small measures of coal.

All offences were officially punishable by a stint in the pillory, but because the guilds were self-regulated, most perpetrators got off with only a fine – to the inevitable anger of the masses.

6) “An abominable sight of monks” Monks weren’t particularly popular during the 15th century. Bede’s Life of Cuthbert, dated around AD 725, is the story of a party of monks who almost drowned when their boat was caught in a storm on the River Tyne. Cuthbert pleaded with the peasants on the bank for help but “the rustics, turning on him with angry minds and angry mouths, exclaimed, ‘Nobody shall pray for them: May God spare none of them! For they have taken away from men the ancient rites and customs, and how the new ones are to be attended to, nobody knows.’”

By the 15th century this resentment of the trampling of pagan traditions had been exacerbated by a perception of monks as being well fed and comfortable while the general population starved. ‘Abominable’ is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “causing moral revulsion”, which is a fairly accurate description of the reaction this image provoked.

7) “A superfluity of nuns” Superfluity can be interpreted in two ways – the first is as historical fact. There were around 138 nunneries in England between 1270 and 1536, many of which were severely overcrowded. The convent was seen as a natural step for the daughters of the nobility who had passed marriageable age, and lords put pressure on prioresses to accept their daughters even if they were already full.

Alternatively, though, the excess of nuns referred to here could have been a comment on the emerging view among agitators for church reform that the days of the monastery and convent were over. Some 50 years after this noun appeared in print in The Book of St Albans Henry VIII ordered their closure, and the Protestant Reformation was in full swing.

8) “A stud of horses” Horses were at the absolute centre of life in the Middle Ages. Rather than the breeds we’re familiar with today, medieval horses were classified by the role they played in society. There were destriers, stallions that were used as warhorses by royalty and lords; palfreys, bred for general-purpose riding, war and travel, usually owned by the wealthy; coursers, steady cavalry horses; and rouncies – common-grade hack horses of no special breeding.

During the Middle Ages, monasteries often ran breeding centres called stud farms – ‘stud’ has its roots in the German word ‘Stute’, meaning mare. State stud farms also existed: the first was established under Louis XIV of France in 1665, by which time ‘a stud of horses’ was already established as the proper collective.

9) ‘A pack/cry/kennel of hounds’ Hunting dogs were important members of the medieval household. Every noble family kept kennels for their dogs, and these were looked after by a team of dedicated servants.

‘A cry of hounds’ is thought to derive from the hunting cry that instructs the hounds in their pursuit. The traditional English hunting call ‘Tally Ho!’ is a shortening of ‘Tallio, hoix, hark, forward,’ which, according to an 1801 edition of The Sporting Magazine, is an Anglicized version of the French terms ‘Thia-hilaud’ and ‘a qui forheur’, which appear in La Vénerie by Jacques du Fouilloux, first published at Poitiers in 1561.

This was adapted into English by George Gascoigne under the title The Noble Arte of Venerie, and became one of the pillars of a young gentleman’s hunting education.

10) “A richesse of martens” The European pine marten was considered a top prize for hunters in the Middle Ages. Of all the ‘vermin of the chase’, which included foxes, wild cats, polecats and squirrels, the marten was the most sought after because of its valuable pelt.

Tudor ‘statutes of apparel’ – strict laws governing the amount of money the people could spend on clothing – dictated the colours, cuts and materials that could be worn by each level of society, and stated which furs could be worn by which tier of the aristocracy. Only those of or above the rank of duke, marquise and earl were allowed to wear sable fur, while ermine, the white winter coat of the stoat, which could only be obtained for a few months of the year, was reserved for royalty.

Chloe Rhodes’ An Unkindness of Ravens: A Book of Collective Nouns is published by Michael O'Mara.

Published on February 04, 2017 02:00

February 3, 2017

Scientists Unravel Secrets of a Hidden Room Within a Hidden Room in English Tudor Mansion

Ancient Origins

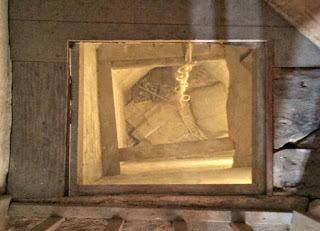

A team of scientists provided with 3D laser scanners have disclosed the secrets of a hidden room, known as a "priest hole," in the tower of an English Tudor mansion linked to the failed "Gunpowder Plot" to assassinate King James I in 1605.

New Study Reveals Secrets of the “Priest Holes”