MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 61

April 8, 2017

2,000-year-old Warrior Armor Made of Reindeer Antlers Found on the Arctic Circle

Ancient Origins

By: The Siberian Times Reporter

The ceremonial suit was embellished with decorations and left as a sacrifice for the gods by ancient bear cult polar people, say archeologists. The discovery is the oldest evidence of armor found in the north of western Siberia, and was located at the rich Ust-Polui site, dating to between the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD.

Earlier discoveries at the site indicate a bear cult among these ancient people.

Archeologist Andrey Gusev, from the Scientific Research Centre of the Arctic in Salekhard, said the plates of armor found at the site are all made from reindeer antlers.

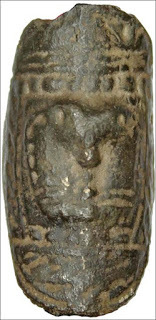

'The largest were 23-25 centimetres in length (pictured upper left). Others are 12-14 centimetres in length, thinner and richly ornamented (pictured upper right and bottom).' Pictures: Andrey Gusev

'There are about 30 plates in the collection of Ust-Polui,' he said. 'They differ regarding the degree of preservation, as well as the size, location of mounting holes, and the presence or absence of ornamentation.'

The largest were 23-25 centimetres in length. In ancient times, they would have been fixed to a leather base and offered a reliable means of protection.

The largest were 23-25 centimetres in length. In ancient times, they would have been fixed to a leather base and offered a reliable means of protection.

Others are 12-14 centimetres in length, thinner and richly ornamented.

'I'm writing still under the impression, as I've just seen these things. This is literally a world scale discovery'. Picture: Bear ring, bronze, finding of 2013, by Andrey Gusev

'The ornamentation on the plates can be individual, that is after the thorough analysis we could say how many warriors left armor here, judging by the style of decorations.'

Other conical shaped armor is seen as plates on helmets worn by the ancient warriors. 'In the taiga zone of Western Siberia, finds of real iron helmets were extremely rare,' he said. 'But in the middle of the first millennium AD, bronze images appeared of people wearing headdresses clearly resembling helmets. '

A likely explanation may be a long tradition of making antler helmets.'

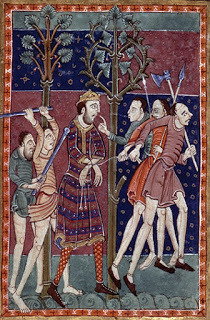

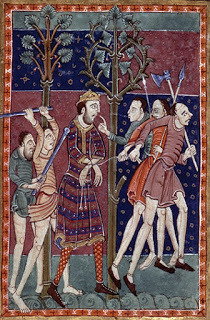

According to Gusev Yamal, the armor resembled the design used by Kulai peole. Picture: Alexander Soloviev

Gusev said the armor resembled the warrior picture here, which relates to designs used by the Kualai people, hunters and fishermen native to the taiga.

He believes the armor was deliberately left at Ust-Polui, an ancient sacred place, as a gift or sacrifice to the gods.

As previously revealed by The Siberian Times, a 2,000 year old ring found at the same site is seen as proof of a bear cult among these ancient polar people who left no written records.

Made of high quality bronze, this ancient Arctic jewellery features an image of a bear's head and paws. 'The ring is tiny in diameter so even a young girl, let alone a woman, cannot wear it,' he said. 'We concluded that it was used in a ritual connected with a bear cult and was put on the bear claw.'

[image error]

A 2,000 year old ring found at the same site is seen as proof of a bear cult among these ancient polar people who left no written records. Pictures: Andrey Gusev

The theory is that the ring was fitted to the claw of a slain bear, an animal worshipped by ancient Khanty tribes as an ancestor and a sacred animal. 'After killing the bear they had a bear festival to honor the animal's memory. The head and front paws a bear was adorned with a handkerchief, rings, and a few days lying in the house.’

'This combination of images on the ring and the fact that it was found in the sanctuary of Ust-Polui led us to believe that a bear cult was also practiced there.'

Top Image: 'The ornamentation on the plates can be individual, that is after the thorough analysis we could say how many warriors left armor here.' Picture: Andrey Gusev Insert: According to Gusev Yamal armor resembled the design used by Kulai peole. Picture: Alexander Soloviev

The article ‘2,000-year-old Warrior Armour Made of Reindeer Antlers Found on the Arctic Circle’ originally appeared on The Siberian Times and has been republished with permission.

By: The Siberian Times Reporter

The ceremonial suit was embellished with decorations and left as a sacrifice for the gods by ancient bear cult polar people, say archeologists. The discovery is the oldest evidence of armor found in the north of western Siberia, and was located at the rich Ust-Polui site, dating to between the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD.

Earlier discoveries at the site indicate a bear cult among these ancient people.

Archeologist Andrey Gusev, from the Scientific Research Centre of the Arctic in Salekhard, said the plates of armor found at the site are all made from reindeer antlers.

'The largest were 23-25 centimetres in length (pictured upper left). Others are 12-14 centimetres in length, thinner and richly ornamented (pictured upper right and bottom).' Pictures: Andrey Gusev

'There are about 30 plates in the collection of Ust-Polui,' he said. 'They differ regarding the degree of preservation, as well as the size, location of mounting holes, and the presence or absence of ornamentation.'

The largest were 23-25 centimetres in length. In ancient times, they would have been fixed to a leather base and offered a reliable means of protection.

The largest were 23-25 centimetres in length. In ancient times, they would have been fixed to a leather base and offered a reliable means of protection.Others are 12-14 centimetres in length, thinner and richly ornamented.

'I'm writing still under the impression, as I've just seen these things. This is literally a world scale discovery'. Picture: Bear ring, bronze, finding of 2013, by Andrey Gusev

'The ornamentation on the plates can be individual, that is after the thorough analysis we could say how many warriors left armor here, judging by the style of decorations.'

Other conical shaped armor is seen as plates on helmets worn by the ancient warriors. 'In the taiga zone of Western Siberia, finds of real iron helmets were extremely rare,' he said. 'But in the middle of the first millennium AD, bronze images appeared of people wearing headdresses clearly resembling helmets. '

A likely explanation may be a long tradition of making antler helmets.'

According to Gusev Yamal, the armor resembled the design used by Kulai peole. Picture: Alexander Soloviev

Gusev said the armor resembled the warrior picture here, which relates to designs used by the Kualai people, hunters and fishermen native to the taiga.

He believes the armor was deliberately left at Ust-Polui, an ancient sacred place, as a gift or sacrifice to the gods.

As previously revealed by The Siberian Times, a 2,000 year old ring found at the same site is seen as proof of a bear cult among these ancient polar people who left no written records.

Made of high quality bronze, this ancient Arctic jewellery features an image of a bear's head and paws. 'The ring is tiny in diameter so even a young girl, let alone a woman, cannot wear it,' he said. 'We concluded that it was used in a ritual connected with a bear cult and was put on the bear claw.'

[image error]

A 2,000 year old ring found at the same site is seen as proof of a bear cult among these ancient polar people who left no written records. Pictures: Andrey Gusev

The theory is that the ring was fitted to the claw of a slain bear, an animal worshipped by ancient Khanty tribes as an ancestor and a sacred animal. 'After killing the bear they had a bear festival to honor the animal's memory. The head and front paws a bear was adorned with a handkerchief, rings, and a few days lying in the house.’

'This combination of images on the ring and the fact that it was found in the sanctuary of Ust-Polui led us to believe that a bear cult was also practiced there.'

Top Image: 'The ornamentation on the plates can be individual, that is after the thorough analysis we could say how many warriors left armor here.' Picture: Andrey Gusev Insert: According to Gusev Yamal armor resembled the design used by Kulai peole. Picture: Alexander Soloviev

The article ‘2,000-year-old Warrior Armour Made of Reindeer Antlers Found on the Arctic Circle’ originally appeared on The Siberian Times and has been republished with permission.

Published on April 08, 2017 02:00

April 7, 2017

In profile: the British princess who scandalised the royal family

History Extra

Here, Laurie Graham, the author of The Grand Duchess of Nowhere, tells you everything you need to know about the famous British princess…

Born: 25 November 1876, San Antonio Palace, Valletta, Malta

Died: 2 March 1936, Schloss Amorbach, Bavaria

Family:

Ducky was the daughter of Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg and Grand Duchess Marie Alexandrovna of Russia. She therefore had two illustrious grandparents: Queen Victoria and Tsar Alexander II.

Famous for:

Her prowess as a horsewoman, her scandalous divorce, and her position in the crumbling House of Romanov in 1917.

Life:

At the time of Ducky’s birth, her father was serving in the Royal Navy. Her childhood was spent at various naval bases and in a rented house, Eastwell Park, in Kent. She and her siblings also travelled with their mother to her native Russia, where Ducky fell in love with one of her cousins, Cyril Vladimirovich Romanov.

Queen Victoria, always planning advantageous marriages for her grandchildren, thought the Romanovs too foreign for consideration. The husband she chose for Ducky was another cousin, Grand Duke Ernest of Hesse. He and Ducky were married on 19 April 1894.

Ernest was a reluctant bridegroom, and on the day of the wedding, his sister Alix rather stole the couple’s thunder by announcing her own engagement, to Tsesarevich Nicholas, soon to be Tsar Nicholas II. The marriage of her sister-in-law to the next Russian Emperor was to shape much of Ducky’s future life.

Cyril Vladimirovich was aware of Ducky’s feelings for him and reciprocated them, but he held out no hope for their future. He was a serving officer in the Russian Navy, travelling the world. She was married to Ernest, and divorce was unthinkable.

To the amazement of those who knew Ernest’s sexual preferences (it was common knowledge that he was attracted to men), Ducky became pregnant. Their daughter, Elisabeth, was born in March 1895, and Ernie proved to be a besotted father.

Nevertheless, Ducky’s misery and loneliness in the marriage prompted her to beg Grandma Queen for permission to divorce – her plea was denied.

On 22 January 1901, Queen Victoria died. Freed of her grandmother’s iron rule, Ducky left Ernest and demanded a divorce. Cyril, all too aware of the ramifications of marrying a divorced cousin, kept a low profile. Ernie’s sister Alix, now Empress of Russia, was appalled by the divorce and the insinuations about her brother’s sexuality. She became Ducky’s avowed enemy.

In autumn 1903, tragedy struck: Ducky and Ernie’s eight-year-old daughter died of typhoid. Ducky’s grief finally brought Cyril to her side. They were married, quietly and without the tsar’s permission, on 8 October 1905.

Empress Alix’s revenge was swift: Cyril was stripped of his title, expelled from the navy, and banished from Russia.

Ducky and Cyril began their married life in happy exile in Paris. Two daughters were born – Masha in 1907, and Kira in 1909.

In Russia, Tsar Nicholas was beginning to feel isolated. His brother, Grand Duke Michael, had also been banished for marrying a divorcee. Cyril’s father, a pillar of the Romanov family, was dying, and the young tsesarevich, Alexis, was stricken with haemophilia.

Nicholas invited Cyril to return to Russia and bring with him his wife and young family. Overnight Ducky became the Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna.

But time failed to soften Empress Alix’s antipathy to Ducky. Even as civil unrest intensified and the tsar became increasingly beleaguered, the Imperial family kept their distance.

When war broke out August 1914, Ducky formed an ambulance unit and travelled with it to the Polish front.

At the end of 1916, following the murder of the Empress’s controversial favourite, Grigori Rasputin, the Romanov dynasty began to splinter. Some believed Tsar Nicholas could be persuaded to make reforms, while others felt it was a lost cause.

Ducky’s husband was one of the first to declare himself. In March 1917, after a mutiny at the Kronstadt garrison, Cyril broke with the tsar and pledged allegiance to the new government.

As the Revolution gathered momentum and the prospects of the Romanovs became clear, Cyril and Ducky (40 years old and heavily pregnant with her third child) escaped to Finland. They spent the rest of their lives in exile, principally in France, where Cyril continued to use his imperial title and to plot for the eventual restoration of the Romanov monarchy.

In late January 1936 Ducky was in Germany at a granddaughter’s christening when she suffered a stroke. She died just over four weeks later, and was buried in her family vault in Coburg. Cyril survived her by less than three years.

The torch of restoration passed to their son, Vladimir, born in exile in Finland, and is still carried today by his daughter, Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna.

Laurie Graham is a historical novelist and journalist. Her novel about Ducky, The Grand Duchess of Nowhere, is published by Quercus, hardback £19.99.

Here, Laurie Graham, the author of The Grand Duchess of Nowhere, tells you everything you need to know about the famous British princess…

Born: 25 November 1876, San Antonio Palace, Valletta, Malta

Died: 2 March 1936, Schloss Amorbach, Bavaria

Family:

Ducky was the daughter of Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg and Grand Duchess Marie Alexandrovna of Russia. She therefore had two illustrious grandparents: Queen Victoria and Tsar Alexander II.

Famous for:

Her prowess as a horsewoman, her scandalous divorce, and her position in the crumbling House of Romanov in 1917.

Life:

At the time of Ducky’s birth, her father was serving in the Royal Navy. Her childhood was spent at various naval bases and in a rented house, Eastwell Park, in Kent. She and her siblings also travelled with their mother to her native Russia, where Ducky fell in love with one of her cousins, Cyril Vladimirovich Romanov.

Queen Victoria, always planning advantageous marriages for her grandchildren, thought the Romanovs too foreign for consideration. The husband she chose for Ducky was another cousin, Grand Duke Ernest of Hesse. He and Ducky were married on 19 April 1894.

Ernest was a reluctant bridegroom, and on the day of the wedding, his sister Alix rather stole the couple’s thunder by announcing her own engagement, to Tsesarevich Nicholas, soon to be Tsar Nicholas II. The marriage of her sister-in-law to the next Russian Emperor was to shape much of Ducky’s future life.

Cyril Vladimirovich was aware of Ducky’s feelings for him and reciprocated them, but he held out no hope for their future. He was a serving officer in the Russian Navy, travelling the world. She was married to Ernest, and divorce was unthinkable.

To the amazement of those who knew Ernest’s sexual preferences (it was common knowledge that he was attracted to men), Ducky became pregnant. Their daughter, Elisabeth, was born in March 1895, and Ernie proved to be a besotted father.

Nevertheless, Ducky’s misery and loneliness in the marriage prompted her to beg Grandma Queen for permission to divorce – her plea was denied.

On 22 January 1901, Queen Victoria died. Freed of her grandmother’s iron rule, Ducky left Ernest and demanded a divorce. Cyril, all too aware of the ramifications of marrying a divorced cousin, kept a low profile. Ernie’s sister Alix, now Empress of Russia, was appalled by the divorce and the insinuations about her brother’s sexuality. She became Ducky’s avowed enemy.

In autumn 1903, tragedy struck: Ducky and Ernie’s eight-year-old daughter died of typhoid. Ducky’s grief finally brought Cyril to her side. They were married, quietly and without the tsar’s permission, on 8 October 1905.

Empress Alix’s revenge was swift: Cyril was stripped of his title, expelled from the navy, and banished from Russia.

Ducky and Cyril began their married life in happy exile in Paris. Two daughters were born – Masha in 1907, and Kira in 1909.

In Russia, Tsar Nicholas was beginning to feel isolated. His brother, Grand Duke Michael, had also been banished for marrying a divorcee. Cyril’s father, a pillar of the Romanov family, was dying, and the young tsesarevich, Alexis, was stricken with haemophilia.

Nicholas invited Cyril to return to Russia and bring with him his wife and young family. Overnight Ducky became the Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna.

But time failed to soften Empress Alix’s antipathy to Ducky. Even as civil unrest intensified and the tsar became increasingly beleaguered, the Imperial family kept their distance.

When war broke out August 1914, Ducky formed an ambulance unit and travelled with it to the Polish front.

At the end of 1916, following the murder of the Empress’s controversial favourite, Grigori Rasputin, the Romanov dynasty began to splinter. Some believed Tsar Nicholas could be persuaded to make reforms, while others felt it was a lost cause.

Ducky’s husband was one of the first to declare himself. In March 1917, after a mutiny at the Kronstadt garrison, Cyril broke with the tsar and pledged allegiance to the new government.

As the Revolution gathered momentum and the prospects of the Romanovs became clear, Cyril and Ducky (40 years old and heavily pregnant with her third child) escaped to Finland. They spent the rest of their lives in exile, principally in France, where Cyril continued to use his imperial title and to plot for the eventual restoration of the Romanov monarchy.

In late January 1936 Ducky was in Germany at a granddaughter’s christening when she suffered a stroke. She died just over four weeks later, and was buried in her family vault in Coburg. Cyril survived her by less than three years.

The torch of restoration passed to their son, Vladimir, born in exile in Finland, and is still carried today by his daughter, Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna.

Laurie Graham is a historical novelist and journalist. Her novel about Ducky, The Grand Duchess of Nowhere, is published by Quercus, hardback £19.99.

Published on April 07, 2017 02:00

April 6, 2017

Quarrying and Blasting May Destroy 2100-Year-Old Castle Site and Statue of Mother Goddess in Turkey

Ancient Origins

Blasting and quarrying of rock at a site near the ancient Kurul Castle in Turkey have endangered the structure and a precious statue of the ancient goddess Cybele.

The castle, which dates back about 2,100 years, is located in the northern province of Ordu near the Black Sea. King Mithridates VI of Armenia Minor and Pontus had the castle built during his reign, which spanned from 120 to 63 BC.

Kurul Rock archaeological site, Ordu, Turkey. ( Black Sea-silk Road Corridor )

The explosions going on daily near the castle have threatened the sculpture of Cybele, an ancient mother goddess of the region, says an article about the situation in Hurriyet Daily News online. The castle is situated on the peak of the mountain in Bayadi village.

The digs carried out there since 2010 are being conducted under the supervision of professor Yücel Şenyurt.

When the discovery of the statue of Cybele was made known to the world, about 15,000 people visited the castle to see it.

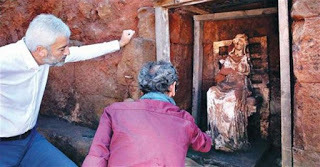

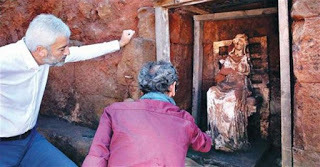

Examining the Cybele statue in Ordu, Turkey. ( Hurriyet Daily News )

Now, the archaeological excavations are still going on at the same time as the quarrying and blasting with dynamite, on the slopes of the Kurul Rocks above the Melet River. This quarrying could spell the end of, or great damage to, what remains of the Kurul Castle.

Governmental authorities, the quarrying company, and archaeologists are trying to sort out the situation and see to the protection of the site.

As Ancient Origins reported in January 2017, Cybele was a goddess of ecstatic and chthonic reproductive mysteries, the primary mother goddess of ancient Anatolia, and Phrygia's only known goddess thus far. She was a "Mistress of Animals," "Great Mother" and "Mother of the Mountain" and it appears that Cybele was adopted by the Greeks in Asia Minor (modern day Turkey), and then adapted as she spread from there to mainland Greece, followed by Rome.

Cybele protects from Vesuvius the towns of Stabiae, Herculaneum, Pompeii and Resina (1832) by François-Édouard Picot. ( Public Domain )

A statue of this important goddess is under threat by blasting and quarrying in Turkey.

In Phrygia, no records remain concerning her cult and worship, though there are numerous statues of overweight, seated women that archaeologists believe represent Cybele. Often she is also portrayed giving birth, indicative of her Mother Goddess status.

Cybele has components of various mother goddesses in ancient Greece: Gaia, Rhea, and Demeter, each notable in their own aspects. Gaia is the ancient Greek mother goddess, responsible for birthing the gods and various aspects of the cosmos with Uranus. Rhea plays a similar role in the universe as the mother of the Olympians, with ancient roots in Minoan and Mycenaean traditions. And Demeter is directly responsible for the changing of the seasons and thus the fertility of the earth.

Figurine of a seated Mother Goddess flanked by two lionesses found at Çatalhöyük, Turkey (about 6000-5500 BC), Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara. ( CC BY SA 2.5 ) Many say this is one of the earliest representations of Cybele.

Ancient Origins also reported on the king who built Kurul castle, Mithridates (spelled also as Mithradates) VI. His full name is Mithridates VI Eupator Dionysius. He was a famous king of Pontus, a Hellenistic kingdom in Asia Minor of Persian origin. Mithridates is best known for his conflict with the Roman Republic in the three Mithridatic Wars, in which the Pontic king fought against three prominent Roman generals – Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Lucius Licinius Lucullus, and Gnaeus Pompey Magnus.

A bust of the king of Pontus Mithridates VI as Heracles. Marble, Roman imperial period (1st century). ( CC BY 3.0 ) Mithridates VI built Kurul castle, which is now in danger in Turkey.

Top image: The Kurul Rock archaeological site ( @eslidemirel/imgrum) and this statue of Cybele ( T24) are in danger of being destroyed by nearby blasting and quarrying in Turkey.

By Mark Miller

Blasting and quarrying of rock at a site near the ancient Kurul Castle in Turkey have endangered the structure and a precious statue of the ancient goddess Cybele.

The castle, which dates back about 2,100 years, is located in the northern province of Ordu near the Black Sea. King Mithridates VI of Armenia Minor and Pontus had the castle built during his reign, which spanned from 120 to 63 BC.

Kurul Rock archaeological site, Ordu, Turkey. ( Black Sea-silk Road Corridor )

The explosions going on daily near the castle have threatened the sculpture of Cybele, an ancient mother goddess of the region, says an article about the situation in Hurriyet Daily News online. The castle is situated on the peak of the mountain in Bayadi village.

The digs carried out there since 2010 are being conducted under the supervision of professor Yücel Şenyurt.

When the discovery of the statue of Cybele was made known to the world, about 15,000 people visited the castle to see it.

Examining the Cybele statue in Ordu, Turkey. ( Hurriyet Daily News )

Now, the archaeological excavations are still going on at the same time as the quarrying and blasting with dynamite, on the slopes of the Kurul Rocks above the Melet River. This quarrying could spell the end of, or great damage to, what remains of the Kurul Castle.

Governmental authorities, the quarrying company, and archaeologists are trying to sort out the situation and see to the protection of the site.

As Ancient Origins reported in January 2017, Cybele was a goddess of ecstatic and chthonic reproductive mysteries, the primary mother goddess of ancient Anatolia, and Phrygia's only known goddess thus far. She was a "Mistress of Animals," "Great Mother" and "Mother of the Mountain" and it appears that Cybele was adopted by the Greeks in Asia Minor (modern day Turkey), and then adapted as she spread from there to mainland Greece, followed by Rome.

Cybele protects from Vesuvius the towns of Stabiae, Herculaneum, Pompeii and Resina (1832) by François-Édouard Picot. ( Public Domain )

A statue of this important goddess is under threat by blasting and quarrying in Turkey.

In Phrygia, no records remain concerning her cult and worship, though there are numerous statues of overweight, seated women that archaeologists believe represent Cybele. Often she is also portrayed giving birth, indicative of her Mother Goddess status.

Cybele has components of various mother goddesses in ancient Greece: Gaia, Rhea, and Demeter, each notable in their own aspects. Gaia is the ancient Greek mother goddess, responsible for birthing the gods and various aspects of the cosmos with Uranus. Rhea plays a similar role in the universe as the mother of the Olympians, with ancient roots in Minoan and Mycenaean traditions. And Demeter is directly responsible for the changing of the seasons and thus the fertility of the earth.

Figurine of a seated Mother Goddess flanked by two lionesses found at Çatalhöyük, Turkey (about 6000-5500 BC), Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara. ( CC BY SA 2.5 ) Many say this is one of the earliest representations of Cybele.

Ancient Origins also reported on the king who built Kurul castle, Mithridates (spelled also as Mithradates) VI. His full name is Mithridates VI Eupator Dionysius. He was a famous king of Pontus, a Hellenistic kingdom in Asia Minor of Persian origin. Mithridates is best known for his conflict with the Roman Republic in the three Mithridatic Wars, in which the Pontic king fought against three prominent Roman generals – Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Lucius Licinius Lucullus, and Gnaeus Pompey Magnus.

A bust of the king of Pontus Mithridates VI as Heracles. Marble, Roman imperial period (1st century). ( CC BY 3.0 ) Mithridates VI built Kurul castle, which is now in danger in Turkey.

Top image: The Kurul Rock archaeological site ( @eslidemirel/imgrum) and this statue of Cybele ( T24) are in danger of being destroyed by nearby blasting and quarrying in Turkey.

By Mark Miller

Published on April 06, 2017 02:00

April 5, 2017

Why Do We Ignore the Ancient Treasures on top of Mediterranean Mountains?

Ancient Origiins

Jason König /The Conversation

The mountains of the Mediterranean are permanent reminders of the past. The ancient Greeks climbed to their summits to offer sacrifices to the gods for centuries, even millennia, and handed down stories from generation to generation of the battles and myths which played out on their slopes – Zeus’s defeat of the Titans on Mt Olympus in northern Greece, for instance; or the legendary cave on Crete’s Mt Ida where the goddess Rhea concealed the infant Zeus from his father Cronus to prevent him from being eaten.

There are still traces of these ancient places of worship today. We know of about ten mountaintop sanctuaries with surviving material in mainland Greece and the Aegean, and many more in other parts of the eastern Mediterranean, including dozens on Crete. You might think that these reminders of European life from thousands of years ago would be among the most cherished and protected sites in the world. Instead they are mostly neglected, unloved and ignored.

Not long ago I climbed Mt Zagaras at the eastern end of the Helikon range, a couple of hours north-west of Athens. In ancient times this was a place of tourism and pilgrimage in honour of the Muses, the goddesses of artistic inspiration. The climb starts from the Valley of the Muses, near to the site of the village of Askra, where the Greek poet Hesiod lived. At the head of the valley are lots of columns scattered around the ground, with goats wandering in and out. For centuries this was the site of the great festival of the Muses, whose competitions attracted poets and musicians from all over ancient Greece.

Valley of the Muses. (Der Wunderbare Mandarin/CC BY NC ND 2.0)

Climbing a wide track to the east, you see beehives everywhere, and you can hear bees buzzing in the trees. After a couple of miles you turn uphill very steeply – about a 500m climb. Just below the summit ridge at the edge of a steeply sloping pasture is the sacred Hippocrene spring, which is famously said to have been formed by the hooves of Pegasus. It runs three or four metres below a gap in the rocks, with clouds of flies buzzing above. Fixed to the rock is a rusty chain and a plastic bucket: I had a small sip for inspiration.

From here it’s an hour west to the summit, scrambling along the big outcrops of rock which line the ridge. You can see for miles from the top. There are also the remains of a small building, which may originally have been an altar of Zeus, though some think it’s more likely to have been a watch post.

The summit of Mt Zagaras north of Athens. Jason König

I didn’t see another walker anywhere on Mt Helikon, or on any of the other mountains I climbed in Greece on that trip. But of all the ancient sites I have visited, I find it hard to think of any more memorable.

Conflicting Priorities

The lack of interest in these treasures is well illustrated by Mt Arachnaion in the Peloponnese region in southern Greece. Its highest point is home to the ruins of altars to Zeus and also Hera, queen of the Greek gods. It was a place for ritual and sacrifice dating back to the time of the Mycenaeans, Greece’s first ancient civilisation (1600 BC to 1100 BC). Now it is the site of a wind farm. If you stand by the ruins, with just the ravens and swifts for company, huge turbines stretch both ways along the ridge. While they have been kept away from the summit itself, it feels precarious to have permitted them so close to the site.

Turbines on Arachnaion. (Dan Diffendale/ CC BY NC SA 2.0)

This lack of interest can occasionally pose a much greater threat. Mountain archaeological sites are usually too inconspicuous to be targets for the deliberate destruction we have seen at Palmyra in Syria, but accidental damage is another matter. The summit of the great mountain of Jebel Aqra on the Turkish border with Syria is the site of the biggest surviving ash altar from the ancient world, 55 metres wide and eight metres deep, containing the remains of countless sacrifices. It now stands within a Turkish militarised zone, inaccessible to archaeologists. And last November, Turkish forces were accused of firing mortars from the mountain over the border into Syria.

While I don’t want to suggest that the Mediterranean’s mountain archaeology is urgently under threat, the wider neglect is disheartening. In some cases the sites are inaccessible, partly because many Greek mountains are topped by military installations. This makes these ritual places more difficult to detect and excavate, which may be one reason why many others referred to in the ancient sources have never been found.

For the sites that we do know about, this looks like an enormous missed tourism opportunity. One model for how to do better is Mt Lykaion and the surrounding territory in Arkadia in the centre of Greece’s Peloponnese region. This is the birthplace of Zeus and the legendary home of Pelasgus, the first of the Pelasgians, the mythical inhabitants of Greece.

Ruins below the summit of Mt Lykaion. Jason König

With the help of both local communities and archaeologists, it has recently been turned into the Parrhasian heritage park. The plan is to attract tourists and spread awareness through walking trails and a website. The first information boards and route markers were set up last year, with more to follow in the coming months. You can still see fragments of burned animal bones scattered all over the ground on the summit, the remnants of sacrifices many centuries ago.

Especially at a time of economic hardship in Greece, this kind of approach could point the way forward. These precious sites are among the world’s oldest treasures. Looking down from their summits, it is hard not to be overwhelmed by the feeling that people enjoyed the same view thousands of years earlier. It is difficult to understand why they are so ignored.

Top Image: Mountains on an autumn sunrise. Source: Public Domain

The article ‘Why Do We Ignore the Ancient Treasures on top of Mediterranean Mountains?’ by Jason König was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Jason König /The Conversation

The mountains of the Mediterranean are permanent reminders of the past. The ancient Greeks climbed to their summits to offer sacrifices to the gods for centuries, even millennia, and handed down stories from generation to generation of the battles and myths which played out on their slopes – Zeus’s defeat of the Titans on Mt Olympus in northern Greece, for instance; or the legendary cave on Crete’s Mt Ida where the goddess Rhea concealed the infant Zeus from his father Cronus to prevent him from being eaten.

There are still traces of these ancient places of worship today. We know of about ten mountaintop sanctuaries with surviving material in mainland Greece and the Aegean, and many more in other parts of the eastern Mediterranean, including dozens on Crete. You might think that these reminders of European life from thousands of years ago would be among the most cherished and protected sites in the world. Instead they are mostly neglected, unloved and ignored.

Not long ago I climbed Mt Zagaras at the eastern end of the Helikon range, a couple of hours north-west of Athens. In ancient times this was a place of tourism and pilgrimage in honour of the Muses, the goddesses of artistic inspiration. The climb starts from the Valley of the Muses, near to the site of the village of Askra, where the Greek poet Hesiod lived. At the head of the valley are lots of columns scattered around the ground, with goats wandering in and out. For centuries this was the site of the great festival of the Muses, whose competitions attracted poets and musicians from all over ancient Greece.

Valley of the Muses. (Der Wunderbare Mandarin/CC BY NC ND 2.0)

Climbing a wide track to the east, you see beehives everywhere, and you can hear bees buzzing in the trees. After a couple of miles you turn uphill very steeply – about a 500m climb. Just below the summit ridge at the edge of a steeply sloping pasture is the sacred Hippocrene spring, which is famously said to have been formed by the hooves of Pegasus. It runs three or four metres below a gap in the rocks, with clouds of flies buzzing above. Fixed to the rock is a rusty chain and a plastic bucket: I had a small sip for inspiration.

From here it’s an hour west to the summit, scrambling along the big outcrops of rock which line the ridge. You can see for miles from the top. There are also the remains of a small building, which may originally have been an altar of Zeus, though some think it’s more likely to have been a watch post.

The summit of Mt Zagaras north of Athens. Jason König

I didn’t see another walker anywhere on Mt Helikon, or on any of the other mountains I climbed in Greece on that trip. But of all the ancient sites I have visited, I find it hard to think of any more memorable.

Conflicting Priorities

The lack of interest in these treasures is well illustrated by Mt Arachnaion in the Peloponnese region in southern Greece. Its highest point is home to the ruins of altars to Zeus and also Hera, queen of the Greek gods. It was a place for ritual and sacrifice dating back to the time of the Mycenaeans, Greece’s first ancient civilisation (1600 BC to 1100 BC). Now it is the site of a wind farm. If you stand by the ruins, with just the ravens and swifts for company, huge turbines stretch both ways along the ridge. While they have been kept away from the summit itself, it feels precarious to have permitted them so close to the site.

Turbines on Arachnaion. (Dan Diffendale/ CC BY NC SA 2.0)

This lack of interest can occasionally pose a much greater threat. Mountain archaeological sites are usually too inconspicuous to be targets for the deliberate destruction we have seen at Palmyra in Syria, but accidental damage is another matter. The summit of the great mountain of Jebel Aqra on the Turkish border with Syria is the site of the biggest surviving ash altar from the ancient world, 55 metres wide and eight metres deep, containing the remains of countless sacrifices. It now stands within a Turkish militarised zone, inaccessible to archaeologists. And last November, Turkish forces were accused of firing mortars from the mountain over the border into Syria.

While I don’t want to suggest that the Mediterranean’s mountain archaeology is urgently under threat, the wider neglect is disheartening. In some cases the sites are inaccessible, partly because many Greek mountains are topped by military installations. This makes these ritual places more difficult to detect and excavate, which may be one reason why many others referred to in the ancient sources have never been found.

For the sites that we do know about, this looks like an enormous missed tourism opportunity. One model for how to do better is Mt Lykaion and the surrounding territory in Arkadia in the centre of Greece’s Peloponnese region. This is the birthplace of Zeus and the legendary home of Pelasgus, the first of the Pelasgians, the mythical inhabitants of Greece.

Ruins below the summit of Mt Lykaion. Jason König

With the help of both local communities and archaeologists, it has recently been turned into the Parrhasian heritage park. The plan is to attract tourists and spread awareness through walking trails and a website. The first information boards and route markers were set up last year, with more to follow in the coming months. You can still see fragments of burned animal bones scattered all over the ground on the summit, the remnants of sacrifices many centuries ago.

Especially at a time of economic hardship in Greece, this kind of approach could point the way forward. These precious sites are among the world’s oldest treasures. Looking down from their summits, it is hard not to be overwhelmed by the feeling that people enjoyed the same view thousands of years earlier. It is difficult to understand why they are so ignored.

Top Image: Mountains on an autumn sunrise. Source: Public Domain

The article ‘Why Do We Ignore the Ancient Treasures on top of Mediterranean Mountains?’ by Jason König was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Published on April 05, 2017 01:30

April 4, 2017

Will It Work? Greece Is Willing to Loan Archaeological Treasures in Exchange for the Parthenon Marbles

Ancient Origins

Despite a strong desire to return the Parthenon Marbles to their rightful home in Athens atop the Acropolis, the Greek government decided against taking legal action against the UK last year. Some probably though the battle for the marbles was lost, but now Greece is using another approach – they are offering ancient archaeological “jewels” in exchange for the Parthenon Marbles.

Greece Proposes a Generous Offer to the UK

In another attempt to find a peaceful solution, Greece has invited the British Museum to return the Parthenon Marbles, also known as Elgin Marbles, as a parabolic act in the battle against the anti-democratic forces that keep rising all over Europe, seeking the dissolution of the continent’s unity. The Greek government has the magnanimous offer to consistently loan some of Ancient Greece’s archaeological wonders to British institutions in exchange of the precious Parthenon Marbles.

The Parthenon Marbles on display in the British Museum, London. (public domain)

How the Controversy Began and the Parthenon Marbles Became Known as the “Elgin Marbles”

As Ancient Origin’s writer Mark Miller thoroughly analyzed in a previous article, when the British Empire’s power was at its peak and Greece was under Ottoman rule, many artifacts and artworks, including reliefs and statues from the Parthenon in Athens were taken to Britain. For years, Greece has been trying to get those valuable artifacts back.

In the opinion of very few historians (mostly British), Thomas Bruce, the Earl of Elgin, took those marbles legally when he was ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1799 to 1803. He claimed that he got permission from the Ottomans to take the artwork. However, few historians agree that such an act was legal during periods of slavery and occupation, so the question is: how moral and ethical would this be considered in our contemporary Western World that supposedly values freedom and democracy more than anything?

An idealized view of the Temporary Elgin Room at the Museum in 1819, with portraits of staff, a trustee and visitors. (Public Domain)

Almost two hundred years after Elgin’s act, the Parthenon Marbles remain some of the most controversial artifacts in the British Museum, with more and more British people suggesting that the Parthenon Marbles should return to Greece. Similarly, opinion is divided regarding Lord Elgin. For some he was the savior of the endangered Parthenon sculptures, while others say he was a looter and pillager of Greek antiquities.

The Parthenon in Athens, Greece, from where the marble friezes were taken. (public domain)

Between 1930 and 1940, the Parthenon sculptures were cleaned with wire brush and acid in the British Museum, causing permanent damage of their ancient surface. In 1983, Melina Mercouri, Minister of Culture for Greece, requested the return of the sculptures, and the debate over their return has raged ever since. The controversy around the Parthenon marbles is just one among many concerning artifacts the British took, or some say stole, during the British Empire’s reign.

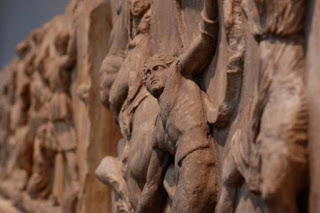

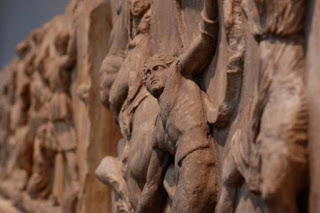

Detail from the Parthenon Marbles. (Chris Devers /CC BY NC ND 2.0)

A Solution Said to Help Western Culture’s Democratic Values

Lydia Koniordou, the Greek Minister of Culture and Sport, thinks that a civilized and democratic solution on this long-lasting controversy would send a message about Europe’s devotion to democracy during a time that many European countries – including Greece and England – are witnessing the uncontrollable rise of far-right forces and nationalistic parties. As Ms. Koniordou told Independent:

“The reunification of the Parthenon Marbles will be a symbolic act that will highlight the fight against the forces that undermine the values and foundations of the European case against those seeking the dissolution of Europe. The Parthenon monument represents a symbol of Western civilization. It is the emblem of democracy, dialogue and freedom of thought.”

Greece has been restoring the Parthenon for many years now and has also constructed a new, impressive museum, specially designed to exhibit the sculptures, even though more than half of them are still held by several museums in Europe.

View of the replica west and south frieze of the Parthenon. (Acropolis Museum)

Professor Louis Godart, the newly elected chairman of the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures (IARPS), made a statement, as Independent reports, where he pointed out the imperative need of these precious artifacts to finally go back home:

“It’s unthinkable that a monument which has been torn apart 200 years ago, which represents the struggle of the world's first democracy for its own survival, is divided into two. We must consider that the Parthenon is a monument that represents our democratic Europe so it is vital that this monument be returned to its former glory.”

It is also worth noting that during Elgin’s years in Greece his staff removed the sculptures so violently and inelegantly that the heads of a centaur and a human in a dramatic fight scene are in Athens, while their bodies are in London. Preservation of art? Probably not the best words to describe this act.

Top Image: The left-hand group of surviving figures from the East Pediment of the Parthenon, exhibited as part of the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum. Source: Andrew Dunn/CC BY SA 2.0

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Despite a strong desire to return the Parthenon Marbles to their rightful home in Athens atop the Acropolis, the Greek government decided against taking legal action against the UK last year. Some probably though the battle for the marbles was lost, but now Greece is using another approach – they are offering ancient archaeological “jewels” in exchange for the Parthenon Marbles.

Greece Proposes a Generous Offer to the UK

In another attempt to find a peaceful solution, Greece has invited the British Museum to return the Parthenon Marbles, also known as Elgin Marbles, as a parabolic act in the battle against the anti-democratic forces that keep rising all over Europe, seeking the dissolution of the continent’s unity. The Greek government has the magnanimous offer to consistently loan some of Ancient Greece’s archaeological wonders to British institutions in exchange of the precious Parthenon Marbles.

The Parthenon Marbles on display in the British Museum, London. (public domain)

How the Controversy Began and the Parthenon Marbles Became Known as the “Elgin Marbles”

As Ancient Origin’s writer Mark Miller thoroughly analyzed in a previous article, when the British Empire’s power was at its peak and Greece was under Ottoman rule, many artifacts and artworks, including reliefs and statues from the Parthenon in Athens were taken to Britain. For years, Greece has been trying to get those valuable artifacts back.

In the opinion of very few historians (mostly British), Thomas Bruce, the Earl of Elgin, took those marbles legally when he was ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1799 to 1803. He claimed that he got permission from the Ottomans to take the artwork. However, few historians agree that such an act was legal during periods of slavery and occupation, so the question is: how moral and ethical would this be considered in our contemporary Western World that supposedly values freedom and democracy more than anything?

An idealized view of the Temporary Elgin Room at the Museum in 1819, with portraits of staff, a trustee and visitors. (Public Domain)

Almost two hundred years after Elgin’s act, the Parthenon Marbles remain some of the most controversial artifacts in the British Museum, with more and more British people suggesting that the Parthenon Marbles should return to Greece. Similarly, opinion is divided regarding Lord Elgin. For some he was the savior of the endangered Parthenon sculptures, while others say he was a looter and pillager of Greek antiquities.

The Parthenon in Athens, Greece, from where the marble friezes were taken. (public domain)

Between 1930 and 1940, the Parthenon sculptures were cleaned with wire brush and acid in the British Museum, causing permanent damage of their ancient surface. In 1983, Melina Mercouri, Minister of Culture for Greece, requested the return of the sculptures, and the debate over their return has raged ever since. The controversy around the Parthenon marbles is just one among many concerning artifacts the British took, or some say stole, during the British Empire’s reign.

Detail from the Parthenon Marbles. (Chris Devers /CC BY NC ND 2.0)

A Solution Said to Help Western Culture’s Democratic Values

Lydia Koniordou, the Greek Minister of Culture and Sport, thinks that a civilized and democratic solution on this long-lasting controversy would send a message about Europe’s devotion to democracy during a time that many European countries – including Greece and England – are witnessing the uncontrollable rise of far-right forces and nationalistic parties. As Ms. Koniordou told Independent:

“The reunification of the Parthenon Marbles will be a symbolic act that will highlight the fight against the forces that undermine the values and foundations of the European case against those seeking the dissolution of Europe. The Parthenon monument represents a symbol of Western civilization. It is the emblem of democracy, dialogue and freedom of thought.”

Greece has been restoring the Parthenon for many years now and has also constructed a new, impressive museum, specially designed to exhibit the sculptures, even though more than half of them are still held by several museums in Europe.

View of the replica west and south frieze of the Parthenon. (Acropolis Museum)

Professor Louis Godart, the newly elected chairman of the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures (IARPS), made a statement, as Independent reports, where he pointed out the imperative need of these precious artifacts to finally go back home:

“It’s unthinkable that a monument which has been torn apart 200 years ago, which represents the struggle of the world's first democracy for its own survival, is divided into two. We must consider that the Parthenon is a monument that represents our democratic Europe so it is vital that this monument be returned to its former glory.”

It is also worth noting that during Elgin’s years in Greece his staff removed the sculptures so violently and inelegantly that the heads of a centaur and a human in a dramatic fight scene are in Athens, while their bodies are in London. Preservation of art? Probably not the best words to describe this act.

Top Image: The left-hand group of surviving figures from the East Pediment of the Parthenon, exhibited as part of the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum. Source: Andrew Dunn/CC BY SA 2.0

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on April 04, 2017 01:30

April 3, 2017

Every Curator’s Dream? 2000-Year-Old Mummy Shroud Discovered at the National Museum of Scotland

Ancient Origins

Curators at the National Museum of Scotland have made an exceptional discovery inside a World War II service envelope with a hand-written note. The writing distinguishes the contents, a remarkably preserved mummy shroud, as being from an ancient Egyptian tomb originally built around 1290 BC. The package had been forgotten in the museum’s storage since the mid-1940s.

Ancient Textile Described as a “Curator’s Dream”

The shroud, which dates to the 9 BC, was discovered during "an in-depth assessment" of Egyptian collections and it is only one of the many objects from this tomb which are in the museum’s collections. Conservators gently humidified it in order for the fibers to become less dry and brittle. This helped experts to cautiously unfold the shroud, a procedure that lasted nearly 24 hours. A hieroglyphic inscription on the shroud divulged the owner’s identity: the son of the Roman-era high-official Montsuef and his wife Tanuat. Dr. Margaret Maitland, senior curator of ancient Mediterranean collections, told BBC :

"To discover an object of this importance in our collections, and in such good condition, is a curator's dream. Before we were able to unfold the textile, tantalising glimpses of colourful painted details suggested that it might be a mummy shroud, but none of us could have imagined the remarkable figure that would greet us when we were finally able to unroll it. The shroud is a very rare object in superb condition and is executed in a highly-unusual artistic style, suggestive of Roman period Egyptian art, yet still very distinctive."

Researchers examining the shroud. ( National Museum of Scotland )

Other Remarkable Shrouds

Of course, this is not the first time an extraordinary shroud is found in great shape. A rare and exquisite funeral shroud dating back 2,000 years to the ancient Paracas culture of Peru was discovered on the Paracas Peninsula in the 1920s. The magnificent textile was described as uniquely complex, with more than 80 hues of blue, green, yellow and red woven into a pattern of 32 frames.

Yet the most notable and famous archaeological story involving a shroud consists of the notorious Shroud of Turin . Believed by many to be the burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth, but held only as a religious article of historical significance by skeptics, the Shroud of Turin has captivated scholars and scientists alike due to its mysterious nature. What’s even stranger with this case is that most recent studies and DNA tests add more fuel to the fire instead of solving the puzzle.

The renowned Shroud of Turin, religious relic and mysterious artifact. ( Public Domain )

Newly Found Shroud Comes from a Roman-Era Burial

Experts claim that the mummy shroud found in the National Museum of Scotland comes from a Roman-era burial in a tomb originally built about 2300 years ago, opposite the famed city of Thebes, modern-day Luxor. First constructed for a chief of police and his wife, it was looted and reused many times before being sealed during the early days of the 1st Century AD.

In Roman-era Egypt, shrouds became more and more significant as the use of coffins was already rare by then. Curators also speculate that because of its owner's close relationship to Montsuef and Tanuat, whose deaths were recorded in 9 BC, it is very possible to date the shroud around the same period of time.

Examining the shroud. ( National Museum of Scotland )

The shroud will be displayed for the first time in The Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Burial exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland on 31 March.

Top Image: Detail of the face on the mummy shroud from around 9 BC which was recently recovered from a hidden package in the National Museum of Scotland’s collections. Source: National Museum of Scotland

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Curators at the National Museum of Scotland have made an exceptional discovery inside a World War II service envelope with a hand-written note. The writing distinguishes the contents, a remarkably preserved mummy shroud, as being from an ancient Egyptian tomb originally built around 1290 BC. The package had been forgotten in the museum’s storage since the mid-1940s.

Ancient Textile Described as a “Curator’s Dream”

The shroud, which dates to the 9 BC, was discovered during "an in-depth assessment" of Egyptian collections and it is only one of the many objects from this tomb which are in the museum’s collections. Conservators gently humidified it in order for the fibers to become less dry and brittle. This helped experts to cautiously unfold the shroud, a procedure that lasted nearly 24 hours. A hieroglyphic inscription on the shroud divulged the owner’s identity: the son of the Roman-era high-official Montsuef and his wife Tanuat. Dr. Margaret Maitland, senior curator of ancient Mediterranean collections, told BBC :

"To discover an object of this importance in our collections, and in such good condition, is a curator's dream. Before we were able to unfold the textile, tantalising glimpses of colourful painted details suggested that it might be a mummy shroud, but none of us could have imagined the remarkable figure that would greet us when we were finally able to unroll it. The shroud is a very rare object in superb condition and is executed in a highly-unusual artistic style, suggestive of Roman period Egyptian art, yet still very distinctive."

Researchers examining the shroud. ( National Museum of Scotland )

Other Remarkable Shrouds

Of course, this is not the first time an extraordinary shroud is found in great shape. A rare and exquisite funeral shroud dating back 2,000 years to the ancient Paracas culture of Peru was discovered on the Paracas Peninsula in the 1920s. The magnificent textile was described as uniquely complex, with more than 80 hues of blue, green, yellow and red woven into a pattern of 32 frames.

Yet the most notable and famous archaeological story involving a shroud consists of the notorious Shroud of Turin . Believed by many to be the burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth, but held only as a religious article of historical significance by skeptics, the Shroud of Turin has captivated scholars and scientists alike due to its mysterious nature. What’s even stranger with this case is that most recent studies and DNA tests add more fuel to the fire instead of solving the puzzle.

The renowned Shroud of Turin, religious relic and mysterious artifact. ( Public Domain )

Newly Found Shroud Comes from a Roman-Era Burial

Experts claim that the mummy shroud found in the National Museum of Scotland comes from a Roman-era burial in a tomb originally built about 2300 years ago, opposite the famed city of Thebes, modern-day Luxor. First constructed for a chief of police and his wife, it was looted and reused many times before being sealed during the early days of the 1st Century AD.

In Roman-era Egypt, shrouds became more and more significant as the use of coffins was already rare by then. Curators also speculate that because of its owner's close relationship to Montsuef and Tanuat, whose deaths were recorded in 9 BC, it is very possible to date the shroud around the same period of time.

Examining the shroud. ( National Museum of Scotland )

The shroud will be displayed for the first time in The Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Burial exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland on 31 March.

Top Image: Detail of the face on the mummy shroud from around 9 BC which was recently recovered from a hidden package in the National Museum of Scotland’s collections. Source: National Museum of Scotland

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on April 03, 2017 01:30

April 2, 2017

Scientists Solve Mystery of Iron Strap and Buckle Unearthed in Medieval Cemetery

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists digging at Gloucester Cathedral, UK, have unearthed a strap for a medieval “false leg.” The metal pieces from the prosthesis band were discovered with a skeleton in the old lay cemetery of the church. The excavation is part of the ongoing Project Pilgrim scheme to redevelop parts of the cathedral.

Clogged in Mud The pieces, including a metal buckle and a piece of the strap, were uncovered in the dig south-east of the building's South Porch. Helen Jeffrey from the cathedral told BBC , “We expected to find some burial sites and skeletons as it used to be a lay cemetery and these little pieces of iron were found in a grave with a skeleton. It was just a real puzzler and we had it taken away to be analyzed - something similar is on display in London.” Experts examining the new finds claim that traces of bone and perhaps wood, found with the band, imply that the device supported a prosthetic leg. Helen Jeffrey said, “We are astonished they found it, it was clogged in mud and looked like little pieces of stones.” The metal object is destined to go on display at the cathedral in the near future.

The Long History of Prosthetics

If you think that prosthetics are the product of contemporary science and medicine, then it’s time for you to reconsider. As DHWTY reports in a 2014 article at Ancient Origins , the origins of prosthetics has a truly ancient history. The oldest known prosthesis that is in existence is from ancient Egypt. In 2000, researchers in Cairo unearthed a prosthetic big toe made of wood and leather which was attached to the almost 3000 year old mummy of an Egyptian noblewoman. As the ancient Egyptians perceived the afterlife as a perfect version of this life, it would have been important for them to go there with their body parts intact. This is evident in the fact that a variety of prosthetic devices have been found on mummies. These include feet, legs, noses, and even penises.

A 3000-year-old prosthetic big toe. Photo source: Discovery.

Centuries later, during the zenith of the Roman Empire, we get introduced to the use of iron as a material for a prosthetic device. More specifically, Marcus Sergius was a Roman general who had lost his right hand during the second Punic War. According to the sources, Sergius had a prosthetic arm made of iron that allowed him to hold his shield. Despite these early advances in ‘prosthetics technology’, there was not much development in this area in the millennia that followed. For instance, iron prosthetic arms and legs were still in use during the Middle Ages, which was more than a thousand years after Marcus Sergius.

Artificial leg, England, 1890-1950. Credit: Science Museum, London

However, with the tremendous evolution of technology, the progress that took place during the 20 th century is undeniable. Today's devices are much lighter, made of plastic, aluminum and composite materials to provide amputees with the most functional devices. In addition to lighter, patient-molded devices, the advent of microprocessors, computer chips and robotics in today's devices are designed to return amputees to the lifestyle they were accustomed to, rather than to simply provide basic functionality or a more pleasing appearance. Prostheses are more realistic with silicone covers and are able to mimic the function of a natural limb more now than at any time before.

Modern-day prosthesis ( CC by SA 3.0 )

Top image: A buckle and part of a strap were found with the metal pieces. Credit: Border Archaeology

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Archaeologists digging at Gloucester Cathedral, UK, have unearthed a strap for a medieval “false leg.” The metal pieces from the prosthesis band were discovered with a skeleton in the old lay cemetery of the church. The excavation is part of the ongoing Project Pilgrim scheme to redevelop parts of the cathedral.

Clogged in Mud The pieces, including a metal buckle and a piece of the strap, were uncovered in the dig south-east of the building's South Porch. Helen Jeffrey from the cathedral told BBC , “We expected to find some burial sites and skeletons as it used to be a lay cemetery and these little pieces of iron were found in a grave with a skeleton. It was just a real puzzler and we had it taken away to be analyzed - something similar is on display in London.” Experts examining the new finds claim that traces of bone and perhaps wood, found with the band, imply that the device supported a prosthetic leg. Helen Jeffrey said, “We are astonished they found it, it was clogged in mud and looked like little pieces of stones.” The metal object is destined to go on display at the cathedral in the near future.

The Long History of Prosthetics

If you think that prosthetics are the product of contemporary science and medicine, then it’s time for you to reconsider. As DHWTY reports in a 2014 article at Ancient Origins , the origins of prosthetics has a truly ancient history. The oldest known prosthesis that is in existence is from ancient Egypt. In 2000, researchers in Cairo unearthed a prosthetic big toe made of wood and leather which was attached to the almost 3000 year old mummy of an Egyptian noblewoman. As the ancient Egyptians perceived the afterlife as a perfect version of this life, it would have been important for them to go there with their body parts intact. This is evident in the fact that a variety of prosthetic devices have been found on mummies. These include feet, legs, noses, and even penises.

A 3000-year-old prosthetic big toe. Photo source: Discovery.

Centuries later, during the zenith of the Roman Empire, we get introduced to the use of iron as a material for a prosthetic device. More specifically, Marcus Sergius was a Roman general who had lost his right hand during the second Punic War. According to the sources, Sergius had a prosthetic arm made of iron that allowed him to hold his shield. Despite these early advances in ‘prosthetics technology’, there was not much development in this area in the millennia that followed. For instance, iron prosthetic arms and legs were still in use during the Middle Ages, which was more than a thousand years after Marcus Sergius.

Artificial leg, England, 1890-1950. Credit: Science Museum, London

However, with the tremendous evolution of technology, the progress that took place during the 20 th century is undeniable. Today's devices are much lighter, made of plastic, aluminum and composite materials to provide amputees with the most functional devices. In addition to lighter, patient-molded devices, the advent of microprocessors, computer chips and robotics in today's devices are designed to return amputees to the lifestyle they were accustomed to, rather than to simply provide basic functionality or a more pleasing appearance. Prostheses are more realistic with silicone covers and are able to mimic the function of a natural limb more now than at any time before.

Modern-day prosthesis ( CC by SA 3.0 )

Top image: A buckle and part of a strap were found with the metal pieces. Credit: Border Archaeology

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on April 02, 2017 01:30

April 1, 2017

April Fools tradition popularized

History.com

On this day in 1700, English pranksters begin popularizing the annual tradition of April Fools’ Day by playing practical jokes on each other.

Although the day, also called All Fools’ Day, has been celebrated for several centuries by different cultures, its exact origins remain a mystery. Some historians speculate that April Fools’ Day dates back to 1582, when France switched from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar, as called for by the Council of Trent in 1563. People who were slow to get the news or failed to recognize that the start of the new year had moved to January 1 and continued to celebrate it during the last week of March through April 1 became the butt of jokes and hoaxes. These included having paper fish placed on their backs and being referred to as “poisson d’avril” (April fish), said to symbolize a young, easily caught fish and a gullible person.

Historians have also linked April Fools’ Day to ancient festivals such as Hilaria, which was celebrated in Rome at the end of March and involved people dressing up in disguises. There’s also speculation that April Fools’ Day was tied to the vernal equinox, or first day of spring in the Northern Hemisphere, when Mother Nature fooled people with changing, unpredictable weather.

April Fools’ Day spread throughout Britain during the 18th century. In Scotland, the tradition became a two-day event, starting with “hunting the gowk,” in which people were sent on phony errands (gowk is a word for cuckoo bird, a symbol for fool) and followed by Tailie Day, which involved pranks played on people’s derrieres, such as pinning fake tails or “kick me” signs on them.

In modern times, people have gone to great lengths to create elaborate April Fools’ Day hoaxes. Newspapers, radio and TV stations and Web sites have participated in the April 1 tradition of reporting outrageous fictional claims that have fooled their audiences. In 1957, the BBC reported that Swiss farmers were experiencing a record spaghetti crop and showed footage of people harvesting noodles from trees; numerous viewers were fooled. In 1985, Sports Illustrated tricked many of its readers when it ran a made-up article about a rookie pitcher named Sidd Finch who could throw a fastball over 168 miles per hour. In 1996, Taco Bell, the fast-food restaurant chain, duped people when it announced it had agreed to purchase Philadelphia’s Liberty Bell and intended to rename it the Taco Liberty Bell. In 1998, after Burger King advertised a “Left-Handed Whopper,” scores of clueless customers requested the fake sandwich.

On this day in 1700, English pranksters begin popularizing the annual tradition of April Fools’ Day by playing practical jokes on each other.

Although the day, also called All Fools’ Day, has been celebrated for several centuries by different cultures, its exact origins remain a mystery. Some historians speculate that April Fools’ Day dates back to 1582, when France switched from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar, as called for by the Council of Trent in 1563. People who were slow to get the news or failed to recognize that the start of the new year had moved to January 1 and continued to celebrate it during the last week of March through April 1 became the butt of jokes and hoaxes. These included having paper fish placed on their backs and being referred to as “poisson d’avril” (April fish), said to symbolize a young, easily caught fish and a gullible person.

Historians have also linked April Fools’ Day to ancient festivals such as Hilaria, which was celebrated in Rome at the end of March and involved people dressing up in disguises. There’s also speculation that April Fools’ Day was tied to the vernal equinox, or first day of spring in the Northern Hemisphere, when Mother Nature fooled people with changing, unpredictable weather.

April Fools’ Day spread throughout Britain during the 18th century. In Scotland, the tradition became a two-day event, starting with “hunting the gowk,” in which people were sent on phony errands (gowk is a word for cuckoo bird, a symbol for fool) and followed by Tailie Day, which involved pranks played on people’s derrieres, such as pinning fake tails or “kick me” signs on them.

In modern times, people have gone to great lengths to create elaborate April Fools’ Day hoaxes. Newspapers, radio and TV stations and Web sites have participated in the April 1 tradition of reporting outrageous fictional claims that have fooled their audiences. In 1957, the BBC reported that Swiss farmers were experiencing a record spaghetti crop and showed footage of people harvesting noodles from trees; numerous viewers were fooled. In 1985, Sports Illustrated tricked many of its readers when it ran a made-up article about a rookie pitcher named Sidd Finch who could throw a fastball over 168 miles per hour. In 1996, Taco Bell, the fast-food restaurant chain, duped people when it announced it had agreed to purchase Philadelphia’s Liberty Bell and intended to rename it the Taco Liberty Bell. In 1998, after Burger King advertised a “Left-Handed Whopper,” scores of clueless customers requested the fake sandwich.

Published on April 01, 2017 01:30

March 31, 2017

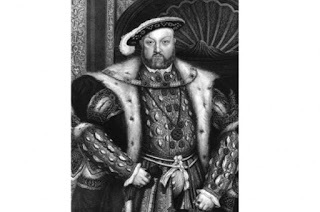

5 things you (probably) didn’t know about Henry VIII

History Extra

c1540, a portrait of King Henry VIII. An engraving by T A Dean from a painting by Hans Holbein. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

1) Henry VIII was slim and athletic for most of his life

At six feet two inches tall, Henry VIII stood head and shoulders above most of his court. He had an athletic physique and excelled at sports, regularly showing off his prowess in the jousting arena.

Having inherited the good looks of his grandfather, Edward IV, in 1515 Henry was described as “the handsomest potentate I have ever set eyes on…” and later an “Adonis”, “with an extremely fine calf to his leg, his complexion very fair…and a round face so very beautiful, that it would become a pretty woman”.

All this changed in 1536 when the king – then in his mid-forties – suffered a serious wound to his leg while jousting. This never properly healed, and instead turned ulcerous, which left Henry increasingly incapacitated.

Four years later, the king’s waist had grown from a trim 32 inches to an enormous 52 inches. By the time of his death, he had to be winched onto his horse. It is this image of the corpulent Henry VIII that has obscured the impressive figure that he cut for most of his life.

2) Henry VIII was a tidy eater

Despite the popular image of Henry VIII throwing a chicken leg over his shoulder as he devoured one of his many feasts, he was in fact a fastidious eater. Only on special occasions, such as a visit from a foreign dignitary, did he stage banquets.

Most of the time, Henry preferred to dine in his private apartments. He would take care to wash his hands before, during and after each meal, and would follow a strict order of ceremony.

Seated beneath a canopy and surrounded by senior court officers, he was served on bended knee and presented with several different dishes to choose from at each course.

3) Henry was a bit of a prude

England’s most-married monarch has a reputation as a ladies’ man – for obvious reasons. As well as his six wives, he kept several mistresses and fathered at least one child by them.

But the evidence suggests that, behind closed doors, he was no lothario. When he finally persuaded Anne Boleyn to become his mistress in body as well as in name, he was shocked by the sexual knowledge that she seemed to possess, and later confided that he believed she had been no virgin.

When she failed to give him a son, he plumped for the innocent and unsullied Jane Seymour instead.

4) Henry’s chief minister liked to party

Although often represented as a ruthless henchman, Thomas Cromwell was in fact one of the most fun-loving members of the court. His parties were legendary, and he would spend lavish sums on entertaining his guests – he once paid a tailor £4,000 to make an elaborate costume that he could wear in a masque to amuse the king.

Cromwell also kept a cage of canary birds at his house, as well as an animal described as a “strange beast”, which he gave to the king as a present.

5) Henry VIII sent more men and women to their deaths than any other monarch

During the later years of Henry’s reign, as he grew ever more paranoid and bad-tempered, the Tower of London was crowded with the terrified subjects who had been imprisoned at his orders.

One of the most brutal executions was that of the aged Margaret de la Pole, Countess of Salisbury. The 67-year-old countess was woken early on the morning of 27 May 1541 and told to prepare for death.

Although initially composed, when Margaret was told to place her head on the block, her self-control deserted her and she tried to escape. Her captors were forced to pinion her to the block, where the amateur executioner hacked at the poor woman’s head and neck, eventually severing them after the eleventh blow.

c1540, a portrait of King Henry VIII. An engraving by T A Dean from a painting by Hans Holbein. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

1) Henry VIII was slim and athletic for most of his life

At six feet two inches tall, Henry VIII stood head and shoulders above most of his court. He had an athletic physique and excelled at sports, regularly showing off his prowess in the jousting arena.

Having inherited the good looks of his grandfather, Edward IV, in 1515 Henry was described as “the handsomest potentate I have ever set eyes on…” and later an “Adonis”, “with an extremely fine calf to his leg, his complexion very fair…and a round face so very beautiful, that it would become a pretty woman”.

All this changed in 1536 when the king – then in his mid-forties – suffered a serious wound to his leg while jousting. This never properly healed, and instead turned ulcerous, which left Henry increasingly incapacitated.

Four years later, the king’s waist had grown from a trim 32 inches to an enormous 52 inches. By the time of his death, he had to be winched onto his horse. It is this image of the corpulent Henry VIII that has obscured the impressive figure that he cut for most of his life.

2) Henry VIII was a tidy eater

Despite the popular image of Henry VIII throwing a chicken leg over his shoulder as he devoured one of his many feasts, he was in fact a fastidious eater. Only on special occasions, such as a visit from a foreign dignitary, did he stage banquets.

Most of the time, Henry preferred to dine in his private apartments. He would take care to wash his hands before, during and after each meal, and would follow a strict order of ceremony.

Seated beneath a canopy and surrounded by senior court officers, he was served on bended knee and presented with several different dishes to choose from at each course.

3) Henry was a bit of a prude

England’s most-married monarch has a reputation as a ladies’ man – for obvious reasons. As well as his six wives, he kept several mistresses and fathered at least one child by them.

But the evidence suggests that, behind closed doors, he was no lothario. When he finally persuaded Anne Boleyn to become his mistress in body as well as in name, he was shocked by the sexual knowledge that she seemed to possess, and later confided that he believed she had been no virgin.

When she failed to give him a son, he plumped for the innocent and unsullied Jane Seymour instead.

4) Henry’s chief minister liked to party

Although often represented as a ruthless henchman, Thomas Cromwell was in fact one of the most fun-loving members of the court. His parties were legendary, and he would spend lavish sums on entertaining his guests – he once paid a tailor £4,000 to make an elaborate costume that he could wear in a masque to amuse the king.

Cromwell also kept a cage of canary birds at his house, as well as an animal described as a “strange beast”, which he gave to the king as a present.

5) Henry VIII sent more men and women to their deaths than any other monarch

During the later years of Henry’s reign, as he grew ever more paranoid and bad-tempered, the Tower of London was crowded with the terrified subjects who had been imprisoned at his orders.

One of the most brutal executions was that of the aged Margaret de la Pole, Countess of Salisbury. The 67-year-old countess was woken early on the morning of 27 May 1541 and told to prepare for death.

Although initially composed, when Margaret was told to place her head on the block, her self-control deserted her and she tried to escape. Her captors were forced to pinion her to the block, where the amateur executioner hacked at the poor woman’s head and neck, eventually severing them after the eleventh blow.

Published on March 31, 2017 01:30

March 30, 2017

How England rode the Viking storm

History Extra