MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 58

May 8, 2017

Latest Thornton Abbey Discovery: Did the Great Famine take a Medieval Priest and Leave an Elaborate Grave?

Ancient Origins

The remains of a Medieval priest who died 700 years ago has been uncovered at Thornton Abbey in Lincolnshire. Research shows he could have been a victim of the Great Famine.

Archaeologists from the University of Sheffield uncovered the rare find at Thornton Abbey in Lincolnshire, which was founded as a monastery in 1139 and went onto become one of the richest religious houses in England.

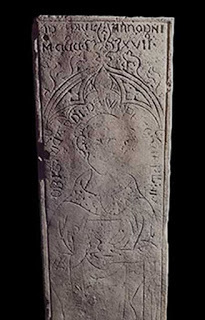

The priest's gravestone was discovered close to the altar of a former hospital chapel. Unusually for the period, it displayed an inscription of the deceased's name, Richard de W'Peton -- abbreviated from 'Wispeton', a medieval incarnation of modern Wispington in Lincolnshire -- and his date of death, 17 April 1317.

The slab also contained an extract from the Bible, specifically Philippians 2:10, which reads; "that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, of those in heaven, and of those on earth, and of those under the earth."

The coffin lid for the Medieval priest Richard de W'Peton. (University of Sheffield)

The discovery of Richard's grave was made by University of Sheffield PhD student Emma Hook, who found his skeletal remains surrounded by the decayed fragments of a wooden coffin. "After taking Richard's skeleton back to the laboratory, despite poor preservation, we were able to establish Richard was around 35-45 years-old at the time of his death and that he had stood around 5ft 4ins tall," said Emma.

"Although he ended his days in the priesthood, there is also some suggestion that he might have had humbler origins in more worldly work; his bones show the marks of robust muscle attachments, indicating that strenuous physical labour had been a regular part of his life at some stage. Nor had his childhood been easy; his teeth show distinctive lines known as dental enamel hypoplasia, indicating that his early years had been marked by a period of malnutrition or illness."

The medieval priest’s bones. (University of Sheffield)

In order to further investigate Richard's health, researchers in the Department of Archaeology produced a 3D scan of his skull. The model produced enables detailed features of the skull to be seen with much more ease than with the naked eye.

This revealed a potentially violent episode in the priest's past: a slight depression in the back of his skull shows evidence of an extremely well-healed blunt force trauma suffered many years before Richard's death.

The 3d image of Richard's skull. (University of Sheffield)

None of the investigations shed light on the cause of his demise at a relatively young age, however there is one possibility that researchers are exploring.

Dr. Hugh Willmott from the University of Sheffield's Department of Archaeology, who has been working on the excavation site at Thornton Abbey since 2011, said: "2017 marks not only the 700th anniversary of Richard's death, but also that of a catastrophic event that is now largely forgotten, but caused years of suffering for the whole of Europe: The Great Famine of 1315-1317.

"Triggered by a whole spring and summer of relentlessly heavy rain that caused widespread crop failures -- which vastly depleted the availability of grain for humans and hay or straw for animals -- this was a period of mass starvation. Although not on the same scale as the Black Death, which devastated Europe from 1346-1353 and which also left its mark at Thornton Abbey, these hungry times struck rich and poor alike, killing millions across the continent."

Ruins of Thornton Abbey, Lincolnshire. (David Wright/CC BY SA 2.0)

He added: "By spring 1317, when Richard died, the crisis was at its peak and its events would undoubtedly have affected medieval hospitals like Thornton Abbey, and the priests who served there.

"These institutions traditionally cared for the poor and hungry as well as the sick, so during the Great Famine sites like Thornton would have found themselves on the front line. Richard would have ministered to the starving, working in the face of desperately limited resources -- and perhaps despite these efforts, he too succumbed to the natural disaster that was unfolding around him. For now, such a narrative can only be a matter of speculation, but it does seem clear that -- whatever caused his death -- at the end of his days Richard was held in high regard, afforded an elaborate burial in the most prestigious part of the hospital chapel, in the very place he would have spent his final years working among the poor and dying."

This is the latest significant archaeological find at Thornton Abbey in Lincolnshire. Last year a mass burial of bodies, known to be victims of the Black Death, was discovered at the hospital. A total of 48 skeletons, many of which were children, were found by the excavation team including PhD and undergraduate archaeology students.

Excavating the site where the Medieval priest Richard de W'Peton was found. (University of Sheffield)

Top image: The recently unearthed medieval priest’s skull and coffin lid. Source: University of Sheffield

Source: Sheffield, University of. "Medieval priest discovered in elaborate grave 700 years after his death." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 17 April 2017.

The remains of a Medieval priest who died 700 years ago has been uncovered at Thornton Abbey in Lincolnshire. Research shows he could have been a victim of the Great Famine.

Archaeologists from the University of Sheffield uncovered the rare find at Thornton Abbey in Lincolnshire, which was founded as a monastery in 1139 and went onto become one of the richest religious houses in England.

The priest's gravestone was discovered close to the altar of a former hospital chapel. Unusually for the period, it displayed an inscription of the deceased's name, Richard de W'Peton -- abbreviated from 'Wispeton', a medieval incarnation of modern Wispington in Lincolnshire -- and his date of death, 17 April 1317.

The slab also contained an extract from the Bible, specifically Philippians 2:10, which reads; "that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, of those in heaven, and of those on earth, and of those under the earth."

The coffin lid for the Medieval priest Richard de W'Peton. (University of Sheffield)

The discovery of Richard's grave was made by University of Sheffield PhD student Emma Hook, who found his skeletal remains surrounded by the decayed fragments of a wooden coffin. "After taking Richard's skeleton back to the laboratory, despite poor preservation, we were able to establish Richard was around 35-45 years-old at the time of his death and that he had stood around 5ft 4ins tall," said Emma.

"Although he ended his days in the priesthood, there is also some suggestion that he might have had humbler origins in more worldly work; his bones show the marks of robust muscle attachments, indicating that strenuous physical labour had been a regular part of his life at some stage. Nor had his childhood been easy; his teeth show distinctive lines known as dental enamel hypoplasia, indicating that his early years had been marked by a period of malnutrition or illness."

The medieval priest’s bones. (University of Sheffield)

In order to further investigate Richard's health, researchers in the Department of Archaeology produced a 3D scan of his skull. The model produced enables detailed features of the skull to be seen with much more ease than with the naked eye.

This revealed a potentially violent episode in the priest's past: a slight depression in the back of his skull shows evidence of an extremely well-healed blunt force trauma suffered many years before Richard's death.

The 3d image of Richard's skull. (University of Sheffield)

None of the investigations shed light on the cause of his demise at a relatively young age, however there is one possibility that researchers are exploring.

Dr. Hugh Willmott from the University of Sheffield's Department of Archaeology, who has been working on the excavation site at Thornton Abbey since 2011, said: "2017 marks not only the 700th anniversary of Richard's death, but also that of a catastrophic event that is now largely forgotten, but caused years of suffering for the whole of Europe: The Great Famine of 1315-1317.

"Triggered by a whole spring and summer of relentlessly heavy rain that caused widespread crop failures -- which vastly depleted the availability of grain for humans and hay or straw for animals -- this was a period of mass starvation. Although not on the same scale as the Black Death, which devastated Europe from 1346-1353 and which also left its mark at Thornton Abbey, these hungry times struck rich and poor alike, killing millions across the continent."

Ruins of Thornton Abbey, Lincolnshire. (David Wright/CC BY SA 2.0)

He added: "By spring 1317, when Richard died, the crisis was at its peak and its events would undoubtedly have affected medieval hospitals like Thornton Abbey, and the priests who served there.

"These institutions traditionally cared for the poor and hungry as well as the sick, so during the Great Famine sites like Thornton would have found themselves on the front line. Richard would have ministered to the starving, working in the face of desperately limited resources -- and perhaps despite these efforts, he too succumbed to the natural disaster that was unfolding around him. For now, such a narrative can only be a matter of speculation, but it does seem clear that -- whatever caused his death -- at the end of his days Richard was held in high regard, afforded an elaborate burial in the most prestigious part of the hospital chapel, in the very place he would have spent his final years working among the poor and dying."

This is the latest significant archaeological find at Thornton Abbey in Lincolnshire. Last year a mass burial of bodies, known to be victims of the Black Death, was discovered at the hospital. A total of 48 skeletons, many of which were children, were found by the excavation team including PhD and undergraduate archaeology students.

Excavating the site where the Medieval priest Richard de W'Peton was found. (University of Sheffield)

Top image: The recently unearthed medieval priest’s skull and coffin lid. Source: University of Sheffield

Source: Sheffield, University of. "Medieval priest discovered in elaborate grave 700 years after his death." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 17 April 2017.

Published on May 08, 2017 02:00

May 7, 2017

Golden Crown on A Coffin Leads the Way to Discovery of Five ‘Lost’ Archbishops of Canterbury

Ancient Origins

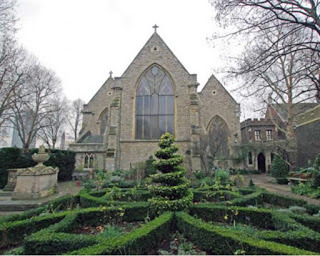

Construction workers have stumbled across the tombs of five archbishops of Canterbury, dating back to the 17th century during Garden museum’s refurbishment. The museum is located in a deconsecrated medieval parish church next to Lambeth Palace, the Archbishop of Canterbury’s official London residence. The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury.

Use of Mobile Phone Leads to the Lucky Discovery

Last year, during the refurbishment of the Garden Museum, construction builders working in the site made an incredible discovery, finding a cache of thirty lead coffins that were hiding underground for centuries. Closer examination uncovered metal plates bearing the names of five former Archbishops of Canterbury, going back to the early 1600s. Building site managers, Karl Patten and Craig Dick, discovered the coffins accidentally as the former chancel at St Mary-at-Lambeth was being converted into an exhibition space. With the use of a mobile phone on a stick to film a flight of stairs leading down to a hidden vault, they spotted the coffins lying on top of each other alongside an archbishop's mitre. Karl Patten told BBC News: "We discovered numerous coffins - and one of them had a gold crown on top of it.”

The Garden Museum at St Mary-at-Lambeth (CC by SA 3.0)

Some Coffins Include Nameplates and Reveal Valuable Information

Two coffins had nameplates, which belonged to Richard Bancroft, who served as archbishop from 1604 to 1610, and John Moore, archbishop from 1783 to 1805. Additionally, Moore’s wife, Catherine Moore, has a coffin plate as well. It’s important to mention here that Richard Bancroft was the lead supervisor of the publication of a new English translation of the Bible, known as the “King James Bible”, which was first published in 1611.

Also identified from his coffin plate is John Bettesworth (1677-1751), the Dean of Arches, the judge who sits at the ecclesiastical court of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Archbishop Richard Bancroft (public domain)

According to Harry Mount, a Sunday Telegraph's journalist and the first person who wasn’t involved directly to the discovery but was granted access, St Mary-at-Lambeth’s records suggest that three more archbishops were most likely buried in the secret vault: Thomas Tenison, archbishop from 1695 to 1715, Matthew Hutton, archbishop from 1757 to 1758, and Frederick Cornwallis, who served as archbishop from 1768 to 1783. A sixth archbishop (1758 to 1768), named Thomas Secker had his viscera buried in a canister in the churchyard. “It was amazing seeing the coffins. We’ve come across lots of bones on this job. But we knew this was different when we saw the Archbishop’s crown,” an excited Patten tells The Sunday Telegraph.

The archbishops' lead coffins in the hidden crypt CREDIT: HEATHCLIFF O'MALLEY

Mystery Surrounds the Identify of the Rest Bodies

Garden Museum Director Christopher Woodward confesses that when he first received the call from the builders he worried that something was wrong with the project and couldn’t imagine that such an important discovery would’ve taken place. “I didn’t know what to expect,” Woodward tells The Sunday Telegraph and continues, “I knew there had been 20,000 bodies buried in the churchyard. But I thought the burial places had been cleared from the nave and aisles, and the vaults under the church had been filled with earth.”

The good news though, made him more than happy, “Wow, it was the crown - it's the mitre of an archbishop, glowing in the dark,” he told BBC News. However, he suggests that there are many more things we don’t know about the church’s history, “Still, we don't know who else is down there,” he said. And continues, "This church had two lives: it was the parish church of Lambeth, this little village by the river…but it was also a kind of annex to Lambeth Palace itself. And over the centuries a significant number of the archbishops' families and archbishops themselves chose to worship here, and chose to be buried here."

Deconsecrated back in the early seventies, St Mary's was due to be wrecked before becoming the Garden Museum. In October 2015, the museum closed for nearly a year and half to go through a € 8,8 million redevelopment project and is due to reopen in May 2017.

Top image: Archbishops were buried with painted, gilded, funerary mitres placed on their coffins CREDIT: GARDEN MUSEUM

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Construction workers have stumbled across the tombs of five archbishops of Canterbury, dating back to the 17th century during Garden museum’s refurbishment. The museum is located in a deconsecrated medieval parish church next to Lambeth Palace, the Archbishop of Canterbury’s official London residence. The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury.

Use of Mobile Phone Leads to the Lucky Discovery

Last year, during the refurbishment of the Garden Museum, construction builders working in the site made an incredible discovery, finding a cache of thirty lead coffins that were hiding underground for centuries. Closer examination uncovered metal plates bearing the names of five former Archbishops of Canterbury, going back to the early 1600s. Building site managers, Karl Patten and Craig Dick, discovered the coffins accidentally as the former chancel at St Mary-at-Lambeth was being converted into an exhibition space. With the use of a mobile phone on a stick to film a flight of stairs leading down to a hidden vault, they spotted the coffins lying on top of each other alongside an archbishop's mitre. Karl Patten told BBC News: "We discovered numerous coffins - and one of them had a gold crown on top of it.”

The Garden Museum at St Mary-at-Lambeth (CC by SA 3.0)

Some Coffins Include Nameplates and Reveal Valuable Information

Two coffins had nameplates, which belonged to Richard Bancroft, who served as archbishop from 1604 to 1610, and John Moore, archbishop from 1783 to 1805. Additionally, Moore’s wife, Catherine Moore, has a coffin plate as well. It’s important to mention here that Richard Bancroft was the lead supervisor of the publication of a new English translation of the Bible, known as the “King James Bible”, which was first published in 1611.

Also identified from his coffin plate is John Bettesworth (1677-1751), the Dean of Arches, the judge who sits at the ecclesiastical court of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Archbishop Richard Bancroft (public domain)

According to Harry Mount, a Sunday Telegraph's journalist and the first person who wasn’t involved directly to the discovery but was granted access, St Mary-at-Lambeth’s records suggest that three more archbishops were most likely buried in the secret vault: Thomas Tenison, archbishop from 1695 to 1715, Matthew Hutton, archbishop from 1757 to 1758, and Frederick Cornwallis, who served as archbishop from 1768 to 1783. A sixth archbishop (1758 to 1768), named Thomas Secker had his viscera buried in a canister in the churchyard. “It was amazing seeing the coffins. We’ve come across lots of bones on this job. But we knew this was different when we saw the Archbishop’s crown,” an excited Patten tells The Sunday Telegraph.

The archbishops' lead coffins in the hidden crypt CREDIT: HEATHCLIFF O'MALLEY

Mystery Surrounds the Identify of the Rest Bodies

Garden Museum Director Christopher Woodward confesses that when he first received the call from the builders he worried that something was wrong with the project and couldn’t imagine that such an important discovery would’ve taken place. “I didn’t know what to expect,” Woodward tells The Sunday Telegraph and continues, “I knew there had been 20,000 bodies buried in the churchyard. But I thought the burial places had been cleared from the nave and aisles, and the vaults under the church had been filled with earth.”

The good news though, made him more than happy, “Wow, it was the crown - it's the mitre of an archbishop, glowing in the dark,” he told BBC News. However, he suggests that there are many more things we don’t know about the church’s history, “Still, we don't know who else is down there,” he said. And continues, "This church had two lives: it was the parish church of Lambeth, this little village by the river…but it was also a kind of annex to Lambeth Palace itself. And over the centuries a significant number of the archbishops' families and archbishops themselves chose to worship here, and chose to be buried here."

Deconsecrated back in the early seventies, St Mary's was due to be wrecked before becoming the Garden Museum. In October 2015, the museum closed for nearly a year and half to go through a € 8,8 million redevelopment project and is due to reopen in May 2017.

Top image: Archbishops were buried with painted, gilded, funerary mitres placed on their coffins CREDIT: GARDEN MUSEUM

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on May 07, 2017 01:30

May 6, 2017

How Old Are the Most Ancient Houses in a Prominent Cypriot City?

Ancient Origins

Polish archaeologists working on Cyprus have discovered the oldest-known homes in Nea Paphos, a prominent capital city and harbor of the ancient Greeks.

The homes date back an impressive 2,400 years and shed new light on the earliest days of an important city. Teams of Polish archaeologists have been working in the city since 1965 but have so far excavated just 10 percent of it, so they expect to excavate many more great finds. The homes were in use for about 1,000 years, from 400 BC until about the 7th century AD, says a press release about the find on the website Science & Scholarship in Poland, or PAP.

During the last excavation season we managed to reach some of the first buildings erected in this ancient city,” Dr. Henryk Meyza of the Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures of the Polish Academy of Sciences told PAP. His team does research in the city’s residential district.

Another team also works in the vicinity—the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw, also headed by Dr. Meyza. Speaking on the discovery, Dr. Meyza said:

"From the beginning, they [the houses] were erected on a regular grid of streets, which cut the area into about 100 by 35 m [328 feet by 115 feet] lots. The houses were rebuilt and erected in a similar way in successive decades. This was also because the construction of this district was preceded by the construction of water drainage system in the stone substrate that was used throughout the history of the city.”

The remnants of a water tank in Nea Paphos; the founders of the town built a water system before building the homes. (Photo: Dr. Henryk Meyza)

The city of Nea (New) Paphos was founded because Palea (Old) Paphos’ harbor was no longer accessible. Nea Paphos had a convenient harbor on which were built large piers. The last independent king of the state of Paphos founded the new city, Dr. Meyza said.

The capital called Nea Paphos would become the largest Greek fleet town after Alexandria in Egypt. Cyprus had much timber, mainly cedar, for the construction of ships back then. As such, it was a valuable asset to the Egyptians of the Ptolemy dynasty. They made the city bigger and more important. "However, the majority of visible relics come from later times," said Dr. Meyza.

Excavations have been ongoing in the area since 1965. (Photo: Dr. Henryk Meyza)

In recent years, the archaeologists have been working to excavate a house they call Hellenistic because it dates to the 4th century BC. It has a simple layout. Several homes are centered around three courtyards, the press release states. The central courtyard was a square with colonnades around it and a garden in the middle. As Dr. Meyza told PAP:

“The house has been researched since the 1980s, but because of its large stylistic heterogeneity it has always been a mystery to us. It was only in recent years that we learned how many redevelopments and changes in its layout had taken place. The central part housed pools of different sizes, and the largest, square pool had a side length of about 7 m. The last phase of development, with the garden, was built only in the late 1st or early 2nd century AD, already in the Roman period.”

The researchers try not to disturb later walls while also getting to the deepest layers to excavate the oldest buildings. These buildings date back to the city’s founding the 4th or 3rd century BC. Archaeologists have independent knowledge of when it was founded from ancient written sources.

Dr. Meyza added that the oldest houses are not that impressive aesthetically. They have clay floors, unlike the newer homes which had beautiful mosaic floors or stone slabs. But they do give insight into the way residences were constructed in that era.

To prevent the destruction of the ruins of the ancient city, the archaeologists dig only where they can look under the earth’s surface. This prevents them from damaging well-preserved relics of walls from more recent times. But even with this extra care, the archaeologists have been able to make some conclusions about the city’s importance.

Top image: A house and villa in Nea Paphos, a town of vital importance to Greek and Egyptian rulers for its harbor and nearby timber for ship construction. (Photo: Dr. Henryk Meyza)

By Mark Miller

Polish archaeologists working on Cyprus have discovered the oldest-known homes in Nea Paphos, a prominent capital city and harbor of the ancient Greeks.

The homes date back an impressive 2,400 years and shed new light on the earliest days of an important city. Teams of Polish archaeologists have been working in the city since 1965 but have so far excavated just 10 percent of it, so they expect to excavate many more great finds. The homes were in use for about 1,000 years, from 400 BC until about the 7th century AD, says a press release about the find on the website Science & Scholarship in Poland, or PAP.

During the last excavation season we managed to reach some of the first buildings erected in this ancient city,” Dr. Henryk Meyza of the Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures of the Polish Academy of Sciences told PAP. His team does research in the city’s residential district.

Another team also works in the vicinity—the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw, also headed by Dr. Meyza. Speaking on the discovery, Dr. Meyza said:

"From the beginning, they [the houses] were erected on a regular grid of streets, which cut the area into about 100 by 35 m [328 feet by 115 feet] lots. The houses were rebuilt and erected in a similar way in successive decades. This was also because the construction of this district was preceded by the construction of water drainage system in the stone substrate that was used throughout the history of the city.”

The remnants of a water tank in Nea Paphos; the founders of the town built a water system before building the homes. (Photo: Dr. Henryk Meyza)

The city of Nea (New) Paphos was founded because Palea (Old) Paphos’ harbor was no longer accessible. Nea Paphos had a convenient harbor on which were built large piers. The last independent king of the state of Paphos founded the new city, Dr. Meyza said.

The capital called Nea Paphos would become the largest Greek fleet town after Alexandria in Egypt. Cyprus had much timber, mainly cedar, for the construction of ships back then. As such, it was a valuable asset to the Egyptians of the Ptolemy dynasty. They made the city bigger and more important. "However, the majority of visible relics come from later times," said Dr. Meyza.

Excavations have been ongoing in the area since 1965. (Photo: Dr. Henryk Meyza)

In recent years, the archaeologists have been working to excavate a house they call Hellenistic because it dates to the 4th century BC. It has a simple layout. Several homes are centered around three courtyards, the press release states. The central courtyard was a square with colonnades around it and a garden in the middle. As Dr. Meyza told PAP:

“The house has been researched since the 1980s, but because of its large stylistic heterogeneity it has always been a mystery to us. It was only in recent years that we learned how many redevelopments and changes in its layout had taken place. The central part housed pools of different sizes, and the largest, square pool had a side length of about 7 m. The last phase of development, with the garden, was built only in the late 1st or early 2nd century AD, already in the Roman period.”

The researchers try not to disturb later walls while also getting to the deepest layers to excavate the oldest buildings. These buildings date back to the city’s founding the 4th or 3rd century BC. Archaeologists have independent knowledge of when it was founded from ancient written sources.

Dr. Meyza added that the oldest houses are not that impressive aesthetically. They have clay floors, unlike the newer homes which had beautiful mosaic floors or stone slabs. But they do give insight into the way residences were constructed in that era.

To prevent the destruction of the ruins of the ancient city, the archaeologists dig only where they can look under the earth’s surface. This prevents them from damaging well-preserved relics of walls from more recent times. But even with this extra care, the archaeologists have been able to make some conclusions about the city’s importance.

Top image: A house and villa in Nea Paphos, a town of vital importance to Greek and Egyptian rulers for its harbor and nearby timber for ship construction. (Photo: Dr. Henryk Meyza)

By Mark Miller

Published on May 06, 2017 01:30

May 5, 2017

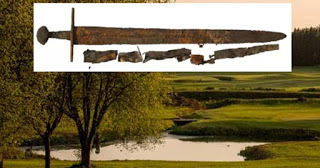

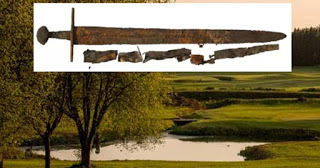

12th Century Inscribed Sword Found on English Golf Course is Remnant of a Deadly Battle

Ancient Origins

A digger team dredging a pond on the golf course where the bloody Battle of Fornham took place in England, discovered an old sword engraved with words, birds and animals inlaid in silver. It is believed that the Medieval sword is a remnant of the deadly battle where forces loyal to Henry II drove the rebel Earl of Leicester’s mercenaries into a marsh and slaughtered them.

Newly Found Sword Sticking Up Just Like Excalibur

The site where the Battle of Fornham took place back in 1173 is nowadays a golf course at All Saints in Fornham St Genevieve, a village and civil parish in the St Edmundsbury district of Suffolk in eastern England. So, it came as a pleasant surprise to the diggers who were working in the area to bring up a bucket from the pond they were dredging and see an ancient sword sticking up just like Excalibur. “It was sticking out of the digger bucket with the cross handle upwards – it was weird, really,” Mr. Weakes told Bury Free Press. David Weakes of Weakes Construction was the banksman to digger driver Dominic Corcoran when they found the sword and couldn’t hide his excitement for being part of such a historic discovery, “It’s lucky the digger bucket didn’t break it. I’ve found coins, old bottles, things like that, before but nothing like this. It’s very rare for something that old to be in that condition after all those years,” he said.

The sword was found sticking out of the digger bucket with cross handle upwards, like King Arthur’s legendary Excalibur sword (parsons.peggy / flickr)

The Bloody Battle of Fornham

The Battle of Fornham took place during the Revolt of 1173–74, a rebellion against King Henry II of England by three of his sons, his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, and their rebel supporters, after the king attempted to conquer new lands for his youngest son, Prince John. John's three older brothers, obviously insulted by their father’s act, fled to the court of King Louis VII of France, where they raised a rebellion. The rebelling sons and the French king gathered a respectable amount of allies and invaded Normandy, while the Scottish king invaded England. These invasions didn’t go well and negotiations between the rebels and the English king didn’t produce any peace. In the autumn of 1173 a third battle took place when the Earl of Leicester landed a large Flemish mercenary force at Walton near Felixstowe, quickly uniting with troops under the Earl of Norwich to push inland after resting at Framlingham .

That combined force mainly comprised foot-soldiers. When the rebels reached Fornham about three miles north of Bury St Edmunds, a small royalist force led by the man Henry left in charge of England in his absence, Richard de Lucy, along with the Royal Constable Humphrey de Bohun, seized the opportunity to attack them in the flank. This was a bold move given the loyalists fielded perhaps fewer than a thousand men, but those men included around four hundred trained cavalry against some eighty mounted warriors on the rebel side.

Action on the initial field of battle may have been brief, the Earl of Leicester was rapidly captured and the loyalist cavalry charges dispersed the inexperienced foot-soldiers. The small groups of Flemish fighters fleeing the fight were easy prey for the local peasantry whose motivation must have been in part a desire to rob those who had come to plunder them, and in part a furious drive to prevent a return to the anarchy of Stephen’s reign just a generation earlier. The invaders were slaughtered in droves.

Sword Has Stunning Silver Engravings

Fast forward to 2017, David Harris, who is in charge of the work at the hotel, said that the sword was sent to a conservator for further examination. During its cleaning, the conservator found engravings of words, birds and animals inlaid in silver. That means the sword, complete with parts of its scabbard, will now go through the Treasure Act process and will be subject of an inquest, while it is currently held by Suffolk County Council’s Archaeological Service.

Inscribed words in inlaid silver. Credit: Suffolk County Council

“It’s wonderful – you can see all the silver emblems over it,” Harris told Bury Free Press. He added, “We would like to retain the sword on the premises. Our restaurant, The View, looks out over the battlefield so people could see it and look out over where it was found while they drink their coffee. Museums are great but it would be nice to have it here on the site where it was found.”

According to Bury Free Press, if an inquest concludes that the sword was riches hidden by someone intending to reclaim it, then it automatically becomes Crown property. However, the finders and land owner of the land are entitled to a reward based on a British Museum valuation.

This is the second 12th century sword to have been found from the Battle of Fornham. The first one, called ‘The Fornham Sword’. It was found in 1933 in mud at the bottom of a ditch in Fornham Park. The Fornham Sword is also engraved with inlaid silver and translates to ‘Be thou blessed’ on one side and ‘In the name of the Lord’ on the other.

The Fornham sword discovered in 1933, currently displayed in Moyse’s Hall Museum.

Top image: Main: The Fornham All Saints golf course. Inset: The newly-discovered Medieval sword. Credit: Suffolk County Council.

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A digger team dredging a pond on the golf course where the bloody Battle of Fornham took place in England, discovered an old sword engraved with words, birds and animals inlaid in silver. It is believed that the Medieval sword is a remnant of the deadly battle where forces loyal to Henry II drove the rebel Earl of Leicester’s mercenaries into a marsh and slaughtered them.

Newly Found Sword Sticking Up Just Like Excalibur

The site where the Battle of Fornham took place back in 1173 is nowadays a golf course at All Saints in Fornham St Genevieve, a village and civil parish in the St Edmundsbury district of Suffolk in eastern England. So, it came as a pleasant surprise to the diggers who were working in the area to bring up a bucket from the pond they were dredging and see an ancient sword sticking up just like Excalibur. “It was sticking out of the digger bucket with the cross handle upwards – it was weird, really,” Mr. Weakes told Bury Free Press. David Weakes of Weakes Construction was the banksman to digger driver Dominic Corcoran when they found the sword and couldn’t hide his excitement for being part of such a historic discovery, “It’s lucky the digger bucket didn’t break it. I’ve found coins, old bottles, things like that, before but nothing like this. It’s very rare for something that old to be in that condition after all those years,” he said.

The sword was found sticking out of the digger bucket with cross handle upwards, like King Arthur’s legendary Excalibur sword (parsons.peggy / flickr)

The Bloody Battle of Fornham

The Battle of Fornham took place during the Revolt of 1173–74, a rebellion against King Henry II of England by three of his sons, his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, and their rebel supporters, after the king attempted to conquer new lands for his youngest son, Prince John. John's three older brothers, obviously insulted by their father’s act, fled to the court of King Louis VII of France, where they raised a rebellion. The rebelling sons and the French king gathered a respectable amount of allies and invaded Normandy, while the Scottish king invaded England. These invasions didn’t go well and negotiations between the rebels and the English king didn’t produce any peace. In the autumn of 1173 a third battle took place when the Earl of Leicester landed a large Flemish mercenary force at Walton near Felixstowe, quickly uniting with troops under the Earl of Norwich to push inland after resting at Framlingham .

That combined force mainly comprised foot-soldiers. When the rebels reached Fornham about three miles north of Bury St Edmunds, a small royalist force led by the man Henry left in charge of England in his absence, Richard de Lucy, along with the Royal Constable Humphrey de Bohun, seized the opportunity to attack them in the flank. This was a bold move given the loyalists fielded perhaps fewer than a thousand men, but those men included around four hundred trained cavalry against some eighty mounted warriors on the rebel side.

Action on the initial field of battle may have been brief, the Earl of Leicester was rapidly captured and the loyalist cavalry charges dispersed the inexperienced foot-soldiers. The small groups of Flemish fighters fleeing the fight were easy prey for the local peasantry whose motivation must have been in part a desire to rob those who had come to plunder them, and in part a furious drive to prevent a return to the anarchy of Stephen’s reign just a generation earlier. The invaders were slaughtered in droves.

Sword Has Stunning Silver Engravings

Fast forward to 2017, David Harris, who is in charge of the work at the hotel, said that the sword was sent to a conservator for further examination. During its cleaning, the conservator found engravings of words, birds and animals inlaid in silver. That means the sword, complete with parts of its scabbard, will now go through the Treasure Act process and will be subject of an inquest, while it is currently held by Suffolk County Council’s Archaeological Service.

Inscribed words in inlaid silver. Credit: Suffolk County Council

“It’s wonderful – you can see all the silver emblems over it,” Harris told Bury Free Press. He added, “We would like to retain the sword on the premises. Our restaurant, The View, looks out over the battlefield so people could see it and look out over where it was found while they drink their coffee. Museums are great but it would be nice to have it here on the site where it was found.”

According to Bury Free Press, if an inquest concludes that the sword was riches hidden by someone intending to reclaim it, then it automatically becomes Crown property. However, the finders and land owner of the land are entitled to a reward based on a British Museum valuation.

This is the second 12th century sword to have been found from the Battle of Fornham. The first one, called ‘The Fornham Sword’. It was found in 1933 in mud at the bottom of a ditch in Fornham Park. The Fornham Sword is also engraved with inlaid silver and translates to ‘Be thou blessed’ on one side and ‘In the name of the Lord’ on the other.

The Fornham sword discovered in 1933, currently displayed in Moyse’s Hall Museum.

Top image: Main: The Fornham All Saints golf course. Inset: The newly-discovered Medieval sword. Credit: Suffolk County Council.

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on May 05, 2017 01:30

May 4, 2017

Remnants of a Revolt: What Did Israeli Archaeologists Find Hidden Under Second Temple Period Homes?

Ancient Origins

Some Israeli high school students have excavated a hiding place for Jews who rebelled against the Romans about 1,860 years ago in the town of Ramat Bet Shemesh. The complex includes cisterns, ritual baths attached to every home, and hidden rebel hideouts underneath the settlement.

The Jewish people rose up against the occupying, overbearing Romans three times between 66 AD, two years after Rome conquered Judea, and 132 AD. The hideouts recently excavated were from the last uprising, called the Bar Kokhba Revolt. After the Romans put down this last uprising, they committed a terrible genocide against the Jews and banned their religion, Judaism.

A press release from the Israel Antiquities Authority states that students from Boyer High School working with the Israel Antiquities Authority unearthed several archaeological features. The settlement dates to the Second Temple period. Sarah Hirshberg, Shua Kisilevitz, and Sarah Levevi-Eilat, excavation directors on behalf of the authority say in the press release:

“The settlement’s extraordinary significance lies in its imposing array of private ritual baths, which were incorporated in the residential buildings. Each household had its own ritual bath and a cistern. Some of the baths uncovered are simple and others are more complex and include an otzar, or collecting basin, into which the rainwater would drain. It is interesting to note that the local inhabitants adhered strictly to the rules regarding purity and impurity.”

Ritual baths that Jews used to cleanse themselves ritually and physically. (Assaf Peretz/Israel Antiquities Authority)

In the ground below the homes and the ritual baths, the students found a labyrinth of refuges dating to the 2nd century. They are connected to elaborate complexes. In some of the hideouts, it is believed the rebels breached cisterns to obtain water. One of the rock-hewn caves had intact ceramic jars and pots that the rebels may have used. The archaeologists believe the town was used after the razing of Jerusalem in 70 AD.

The press release also explains the importance of ritual baths, or mikvas:

“In antiquity, Judaism was already unique in its strict adherence to bodily cleanliness, as commanded in the Bible: “And bathe his body in water, and he shall be clean” (Leviticus 14:9). The act of bathing for purification purposes is also referred to in Hebrew as tvila, or ‘immersion’. The ritual bath is a water installation that is unique to the people of Israel. In order to fulfill their religious and spiritual purpose and cleanse a person of any impurities, the baths were installed according to Jewish religious rules. The bath has to be hewn in the bedrock or connected to the ground; it must be sealed so that its water will not seep out; and only rainwater or spring water must be used, as opposed to ‘drawn’ water.”

In addition to the settlement and hideouts, the Israel Antiquities Authority announced earlier it had found a roadway dating back 2,000 years in Ramat Bet Shemesh. The road was 6 meters (almost 20 feet) wide and went on for about 1.5 kilometers (4,921 feet).

The road, possibly built for Roman Emperor Hadrian, ran for about 1.5 kilometers and was about 6 meters wide. (Israel Antiquities Authority)

The road connected the town of Eleutheropolis (Bet Guvrin) and Jerusalem. Archaeologists think it was built when Roman Emperor Hadrian visited around 130 AD or right after the suppression of the Bar Kokhba uprising in the years 132 to 135. In the past, a milestone inscribed with the name Hadrian was found near the road. Archaeologists unearth huge entryway with frescoes and rebel tunnels in Herod's palace Immense 1,900-Year-Old Slab Found Underwater Names Forgotten Roman Ruler During Bloody Jewish Revolt

Several ancient coins were found between the paving rocks of the road, including a coin from the second year of the Great Revolt in 67 AD (an earlier revolt than the Bar Kokhba revolt); a coin of the Umayyad era; a coin bearing the name of Pontius Pilate from 29 AD; and a coin minted in Jerusalem in 41 AD bearing the name of Agrippa I. This is one of the first developed roads in Israel, the authority’s press release states. Earlier there were simply improvised trails there. The release says:

“However, during the Roman period, as a result of military and other campaigns, the national and international road network started to be developed in an unprecedented manner. The Roman government was well aware of the importance of the roads for the proper running of the empire.”

The Jewish people eventually recovered from the grievous losses of the final revolt, but they would face pogroms through their history and yet another terrible genocide in Europe during World War II.

Top image: An archaeologist collects material in an underground chamber that may have been a hideout for rebels during the Bar Kokhba Revolt of the 2nd century AD. Source: Assaf Peretz/Israel Antiquities Authority

By Mark Miller

Some Israeli high school students have excavated a hiding place for Jews who rebelled against the Romans about 1,860 years ago in the town of Ramat Bet Shemesh. The complex includes cisterns, ritual baths attached to every home, and hidden rebel hideouts underneath the settlement.

The Jewish people rose up against the occupying, overbearing Romans three times between 66 AD, two years after Rome conquered Judea, and 132 AD. The hideouts recently excavated were from the last uprising, called the Bar Kokhba Revolt. After the Romans put down this last uprising, they committed a terrible genocide against the Jews and banned their religion, Judaism.

A press release from the Israel Antiquities Authority states that students from Boyer High School working with the Israel Antiquities Authority unearthed several archaeological features. The settlement dates to the Second Temple period. Sarah Hirshberg, Shua Kisilevitz, and Sarah Levevi-Eilat, excavation directors on behalf of the authority say in the press release:

“The settlement’s extraordinary significance lies in its imposing array of private ritual baths, which were incorporated in the residential buildings. Each household had its own ritual bath and a cistern. Some of the baths uncovered are simple and others are more complex and include an otzar, or collecting basin, into which the rainwater would drain. It is interesting to note that the local inhabitants adhered strictly to the rules regarding purity and impurity.”

Ritual baths that Jews used to cleanse themselves ritually and physically. (Assaf Peretz/Israel Antiquities Authority)

In the ground below the homes and the ritual baths, the students found a labyrinth of refuges dating to the 2nd century. They are connected to elaborate complexes. In some of the hideouts, it is believed the rebels breached cisterns to obtain water. One of the rock-hewn caves had intact ceramic jars and pots that the rebels may have used. The archaeologists believe the town was used after the razing of Jerusalem in 70 AD.

The press release also explains the importance of ritual baths, or mikvas:

“In antiquity, Judaism was already unique in its strict adherence to bodily cleanliness, as commanded in the Bible: “And bathe his body in water, and he shall be clean” (Leviticus 14:9). The act of bathing for purification purposes is also referred to in Hebrew as tvila, or ‘immersion’. The ritual bath is a water installation that is unique to the people of Israel. In order to fulfill their religious and spiritual purpose and cleanse a person of any impurities, the baths were installed according to Jewish religious rules. The bath has to be hewn in the bedrock or connected to the ground; it must be sealed so that its water will not seep out; and only rainwater or spring water must be used, as opposed to ‘drawn’ water.”

In addition to the settlement and hideouts, the Israel Antiquities Authority announced earlier it had found a roadway dating back 2,000 years in Ramat Bet Shemesh. The road was 6 meters (almost 20 feet) wide and went on for about 1.5 kilometers (4,921 feet).

The road, possibly built for Roman Emperor Hadrian, ran for about 1.5 kilometers and was about 6 meters wide. (Israel Antiquities Authority)

The road connected the town of Eleutheropolis (Bet Guvrin) and Jerusalem. Archaeologists think it was built when Roman Emperor Hadrian visited around 130 AD or right after the suppression of the Bar Kokhba uprising in the years 132 to 135. In the past, a milestone inscribed with the name Hadrian was found near the road. Archaeologists unearth huge entryway with frescoes and rebel tunnels in Herod's palace Immense 1,900-Year-Old Slab Found Underwater Names Forgotten Roman Ruler During Bloody Jewish Revolt

Several ancient coins were found between the paving rocks of the road, including a coin from the second year of the Great Revolt in 67 AD (an earlier revolt than the Bar Kokhba revolt); a coin of the Umayyad era; a coin bearing the name of Pontius Pilate from 29 AD; and a coin minted in Jerusalem in 41 AD bearing the name of Agrippa I. This is one of the first developed roads in Israel, the authority’s press release states. Earlier there were simply improvised trails there. The release says:

“However, during the Roman period, as a result of military and other campaigns, the national and international road network started to be developed in an unprecedented manner. The Roman government was well aware of the importance of the roads for the proper running of the empire.”

The Jewish people eventually recovered from the grievous losses of the final revolt, but they would face pogroms through their history and yet another terrible genocide in Europe during World War II.

Top image: An archaeologist collects material in an underground chamber that may have been a hideout for rebels during the Bar Kokhba Revolt of the 2nd century AD. Source: Assaf Peretz/Israel Antiquities Authority

By Mark Miller

Published on May 04, 2017 01:30

May 3, 2017

Why was a Newly Discovered Irish Ringfort Surrounded by Bizarre Burials and Unfinished Jewelry?

Ancient Origins

A medieval ringfort that contained a jewelry workshop and substantial farming has been unearthed in an eye-opener archaeological discovery during a road project about a mile north of Roscommon town in Ireland. More importantly, however, 793 bodies were found during the excavation - and the archaeologists expect their analysis will reveal the whole tale of the ringfort.

The Majority of the Bodies are Intact

With no antecedent record of any occupancy on the site, it was only apparent that there were important archaeological features in the area after the testing results conducted by experienced geophysicists came back. Following an excavation that lasted for over a year and ended last October, the archaeologists exploring the site had a clearer picture of the settlement and concluded that it was inhabited between the 6th and 11th centuries. Experts are optimistic that the dating techniques that will be used during the detailed analysis of the 793 found bodies will reveal the exact period of occupation. Interestingly, nearly 75% of the bodies were completely undamaged, while the rest were obviously distorted.

An archaeologist examining a skeleton found at the ringfort at Ranelagh, Co. Roscommon, Ireland. (Irish Archaeological Consultancy)

More Ringforts are “Hiding” Not Far Away

The excavation, led by archaeologist Shane Delaney, has already showed that the site was not likely inhabited during its later period of use, but instead it served as an administrative and industrial center for the civilians who lived in the surrounding areas.

The earliest ringfort enclosure at the site was around 40 meters (131.23 ft.) in diameter, but there was no confirmation on any maps to propose any significance before the site was tested by archaeologists. According to Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII) project archaeologist Martin Jones, supervising the excavation, there are at least three more ringforts within a 500-meter (1640.42 ft.) distance, “The working theory is that this was originally inhabited by a family that rose to some relative prominence in the area. They may have then constructed a number of other ringforts around this one, which became a centre for industrial activity,” he said, as Irish Examiner reports.

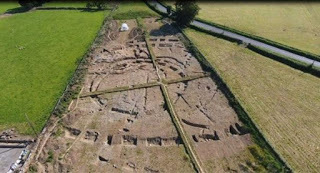

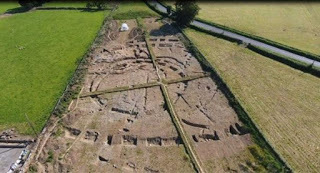

Aerial photograph of the Multivallate Ringfort at Rathrá, Co Roscommon, Ireland. (West Lothian Archaeological Trust (Jim Knowles, Frank Scott and John Wells)/CC BY SA 4.0)

A Large Amount of Unfinished Jewelry Was Found as Well as More Burials

A respectable amount of unfinished jewelry was found by the archaeologists, which indicates that they were designed in a workshop at the site, most likely for commercial purposes. The jewelry objects and fragments found, some of them associated with the burials, include amber and jet beads, a lignite bracelet, and a brooch panel with an enamel stud. A fragment of a copper alloy bracelet has been dated by its decoration to around 350 to 550 AD.

A few crouched burials were also found, with their knees pushed up to their chest, probably suggesting that these were strangers who were buried according to their own traditions. Some of the bodies have clear signs of punishment, including two in which feet and hands may have been bound, one of them buried face down. Additionally, two other buried bodies were decapitated, and several children, or adolescents, were positioned in the ground in embracing positions.

With the excavation work now finished, the analysis of the artifacts and DNA testing of the human remains will provide a clearer picture of the site’s history. Some tests which are scheduled to launch soon will use the latest techniques in order to provide further evidence, such as the diets of the people buried at Ranelagh, and their geographical origins. “When we have the results of radiocarbon dating and all the other analysis, we will have a huge amount of additional information. That’s when the real detective work begins,” Mr. Jones told Irish Examiner, implying that there’s much more work to do before they can make any solid conclusions about the ringfort’s background.

Aerial view of excavations at the site of a medieval ringfort found at Ranelagh in Ireland. (Irish Archaeological Consultancy Ltd.)

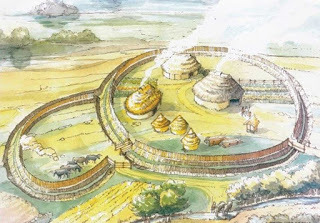

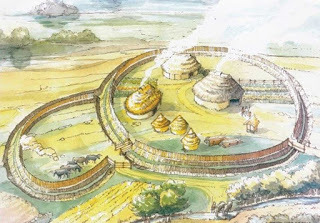

Top Image: Reconstruction of a ringfort at Curraheen, Co Cork, Ireland - the kind of enclosure that would have been built first at the ringfort in Ranelagh, Co Roscommon. Source: Transport Infrastructure Ireland

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A medieval ringfort that contained a jewelry workshop and substantial farming has been unearthed in an eye-opener archaeological discovery during a road project about a mile north of Roscommon town in Ireland. More importantly, however, 793 bodies were found during the excavation - and the archaeologists expect their analysis will reveal the whole tale of the ringfort.

The Majority of the Bodies are Intact

With no antecedent record of any occupancy on the site, it was only apparent that there were important archaeological features in the area after the testing results conducted by experienced geophysicists came back. Following an excavation that lasted for over a year and ended last October, the archaeologists exploring the site had a clearer picture of the settlement and concluded that it was inhabited between the 6th and 11th centuries. Experts are optimistic that the dating techniques that will be used during the detailed analysis of the 793 found bodies will reveal the exact period of occupation. Interestingly, nearly 75% of the bodies were completely undamaged, while the rest were obviously distorted.

An archaeologist examining a skeleton found at the ringfort at Ranelagh, Co. Roscommon, Ireland. (Irish Archaeological Consultancy)

More Ringforts are “Hiding” Not Far Away

The excavation, led by archaeologist Shane Delaney, has already showed that the site was not likely inhabited during its later period of use, but instead it served as an administrative and industrial center for the civilians who lived in the surrounding areas.

The earliest ringfort enclosure at the site was around 40 meters (131.23 ft.) in diameter, but there was no confirmation on any maps to propose any significance before the site was tested by archaeologists. According to Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII) project archaeologist Martin Jones, supervising the excavation, there are at least three more ringforts within a 500-meter (1640.42 ft.) distance, “The working theory is that this was originally inhabited by a family that rose to some relative prominence in the area. They may have then constructed a number of other ringforts around this one, which became a centre for industrial activity,” he said, as Irish Examiner reports.

Aerial photograph of the Multivallate Ringfort at Rathrá, Co Roscommon, Ireland. (West Lothian Archaeological Trust (Jim Knowles, Frank Scott and John Wells)/CC BY SA 4.0)

A Large Amount of Unfinished Jewelry Was Found as Well as More Burials

A respectable amount of unfinished jewelry was found by the archaeologists, which indicates that they were designed in a workshop at the site, most likely for commercial purposes. The jewelry objects and fragments found, some of them associated with the burials, include amber and jet beads, a lignite bracelet, and a brooch panel with an enamel stud. A fragment of a copper alloy bracelet has been dated by its decoration to around 350 to 550 AD.

A few crouched burials were also found, with their knees pushed up to their chest, probably suggesting that these were strangers who were buried according to their own traditions. Some of the bodies have clear signs of punishment, including two in which feet and hands may have been bound, one of them buried face down. Additionally, two other buried bodies were decapitated, and several children, or adolescents, were positioned in the ground in embracing positions.

With the excavation work now finished, the analysis of the artifacts and DNA testing of the human remains will provide a clearer picture of the site’s history. Some tests which are scheduled to launch soon will use the latest techniques in order to provide further evidence, such as the diets of the people buried at Ranelagh, and their geographical origins. “When we have the results of radiocarbon dating and all the other analysis, we will have a huge amount of additional information. That’s when the real detective work begins,” Mr. Jones told Irish Examiner, implying that there’s much more work to do before they can make any solid conclusions about the ringfort’s background.

Aerial view of excavations at the site of a medieval ringfort found at Ranelagh in Ireland. (Irish Archaeological Consultancy Ltd.)

Top Image: Reconstruction of a ringfort at Curraheen, Co Cork, Ireland - the kind of enclosure that would have been built first at the ringfort in Ranelagh, Co Roscommon. Source: Transport Infrastructure Ireland

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on May 03, 2017 01:30

May 2, 2017

Researchers Discover Gladiator Fans Had Souvenirs, Fast Food, and Fresh-Baked Treats at Their Fingertips

Ancient Origins

A team of archaeologists from Austria claim that they have uncovered the remnants of bakeries, fast-food stands, and shops that once served the Gladiator spectators of the ancient Roman city of Carnuntum in modern-day Austria. The team also created impressive digital reconstructions of what the area would have looked like at its heyday.

Ancient Ruins Reveal the Habits of Roman Spectators

A new discovery in Carnuntum, Austria, shows once again how much the Greco-Roman culture has influenced and shaped Western civilization. Just like most spectators do nowadays when they attend a sporting event, Roman “sports fans” also used to buy souvenirs of their favorite and most popular gladiators. The bakeries, fast-food stands, and shops detected in the area indicate that spectators back then would eat before, during, or after the gladiator or chariot events - even though we’re pretty sure that hamburgers and hot dogs weren’t on the menu back then.

Gladiator school and shops. ( LBI ArchPro/7reasons )

Modern Carnuntum

The quiet town of Carnuntum which exists today, just a few miles outside Vienna, doesn’t look anything like the fervid city it once used to be (it was the fourth largest city of the Roman Empire during the 2nd century AD), even though there are certain ruins, such as the monumental Heathen's Gate and the amphitheater, that designate the city’s rich cultural past. Most of the city’s remains are laying underground beneath pastures, while the site has recently been the target of treasure hunters.

Carnuntum reconstructed. ( LBI ArchPro/7reasons )

In 2011, Wolfgang Neubauer, director of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology (LBI ArchPro), with the help of his colleagues, identified a gladiator school at Carnuntum , complete with training grounds, baths, and cells where hundreds of gladiators spent their lives as prisoners. Neubauer has been studying the underground city for a long time, but without disturbing it, with the help of noninvasive practices, such as aerial photography, ground-penetrating radar systems, and magnetometers.

Last Research Reveals City’s “Entertainment District”

During the most recent research, Neubauer’s team discovered Carnuntum's "entertainment district," unconnected from the rest of the city, outside the amphitheater, which could welcome around thirteen thousand people. The archaeologists of the team identified a broad, shop-lined boulevard directing to the amphitheater. After comparing the newly identified structures to known buildings found at other popular Roman cities, such as Pompeii, Neubauer and his colleagues concluded that many of those buildings along the street had most likely served as ancient businesses, "Oil lamps with depictions of gladiators were sold all around this area," Neubauer told Live Science .

In addition to the souvenir shops, the researchers also discovered a string of taverns and "thermopolia" where people bought food at a counter, "It was like a fast-food stand. You can imagine a bar, where the cauldrons with the food were kept warm," Neubauer told Live Science.

Research Also Reveals Another Amphitheater

The researchers also found a storehouse for threshed grain with a huge oven, which was probably used for baking bread. Objects that are usually exposed to such high temperatures have a distinguishable geophysical signature, so when Neubauer's team found a large, rectangular structure with that signature, they concluded that it must have been an oven for baking as Live Science reports

A carbonized loaf of ancient Roman bread from Pompeii. ( CC BY SA 2.0 )

More importantly, however, the latest research also revealed another, older wooden amphitheater, almost 400 meters (1,300 feet) from the main amphitheater, covered under the later wall of the civilian city. Finally, the team announced that they plan to publish the results in an academic journal.

Top Image: Carnuntum reconstructed. Source: LBI ArchPro/7reasons

By Theodoros Karasavvas

A team of archaeologists from Austria claim that they have uncovered the remnants of bakeries, fast-food stands, and shops that once served the Gladiator spectators of the ancient Roman city of Carnuntum in modern-day Austria. The team also created impressive digital reconstructions of what the area would have looked like at its heyday.

Ancient Ruins Reveal the Habits of Roman Spectators

A new discovery in Carnuntum, Austria, shows once again how much the Greco-Roman culture has influenced and shaped Western civilization. Just like most spectators do nowadays when they attend a sporting event, Roman “sports fans” also used to buy souvenirs of their favorite and most popular gladiators. The bakeries, fast-food stands, and shops detected in the area indicate that spectators back then would eat before, during, or after the gladiator or chariot events - even though we’re pretty sure that hamburgers and hot dogs weren’t on the menu back then.

Gladiator school and shops. ( LBI ArchPro/7reasons )

Modern Carnuntum

The quiet town of Carnuntum which exists today, just a few miles outside Vienna, doesn’t look anything like the fervid city it once used to be (it was the fourth largest city of the Roman Empire during the 2nd century AD), even though there are certain ruins, such as the monumental Heathen's Gate and the amphitheater, that designate the city’s rich cultural past. Most of the city’s remains are laying underground beneath pastures, while the site has recently been the target of treasure hunters.

Carnuntum reconstructed. ( LBI ArchPro/7reasons )

In 2011, Wolfgang Neubauer, director of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology (LBI ArchPro), with the help of his colleagues, identified a gladiator school at Carnuntum , complete with training grounds, baths, and cells where hundreds of gladiators spent their lives as prisoners. Neubauer has been studying the underground city for a long time, but without disturbing it, with the help of noninvasive practices, such as aerial photography, ground-penetrating radar systems, and magnetometers.

Last Research Reveals City’s “Entertainment District”

During the most recent research, Neubauer’s team discovered Carnuntum's "entertainment district," unconnected from the rest of the city, outside the amphitheater, which could welcome around thirteen thousand people. The archaeologists of the team identified a broad, shop-lined boulevard directing to the amphitheater. After comparing the newly identified structures to known buildings found at other popular Roman cities, such as Pompeii, Neubauer and his colleagues concluded that many of those buildings along the street had most likely served as ancient businesses, "Oil lamps with depictions of gladiators were sold all around this area," Neubauer told Live Science .

In addition to the souvenir shops, the researchers also discovered a string of taverns and "thermopolia" where people bought food at a counter, "It was like a fast-food stand. You can imagine a bar, where the cauldrons with the food were kept warm," Neubauer told Live Science.

Research Also Reveals Another Amphitheater

The researchers also found a storehouse for threshed grain with a huge oven, which was probably used for baking bread. Objects that are usually exposed to such high temperatures have a distinguishable geophysical signature, so when Neubauer's team found a large, rectangular structure with that signature, they concluded that it must have been an oven for baking as Live Science reports

A carbonized loaf of ancient Roman bread from Pompeii. ( CC BY SA 2.0 )

More importantly, however, the latest research also revealed another, older wooden amphitheater, almost 400 meters (1,300 feet) from the main amphitheater, covered under the later wall of the civilian city. Finally, the team announced that they plan to publish the results in an academic journal.

Top Image: Carnuntum reconstructed. Source: LBI ArchPro/7reasons

By Theodoros Karasavvas

Published on May 02, 2017 01:30

May 1, 2017

May Day

May Day is related to the Celtic festival of Beltane and the Germanic festival of Walpurgis Night. May Day falls exactly half of a year from November 1, another cross-quarter day which is also associated with various northern European pagan and neopagan festivals such as Samhain. May Day marks the end of the uncomfortable winter half of the year in the Northern hemisphere, and it has traditionally been an occasion for popular and often raucous celebrations.

As Europe became Christianized the pagan holidays lost their religious character and either changed into popular secular celebrations, as with May Day, or were merged with or replaced by new Christian holidays as with Christmas, Easter, and All Saint's Day. In the twentieth century, many neopagans began reconstructing the old traditions and celebrating May Day as a pagan religious festival again.

Published on May 01, 2017 02:00

April 30, 2017

Sam’s historical recipe corner: Tiger nut balls

History Extra

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates a healthy snack thought to have been enjoyed in Egypt around 3,500 years ago.

If you, like me, have a sweet tooth but are trying to be healthier then try tiger nut balls.

I found lots of references to this being one of the first Egyptian recipes that we know of, found written on an ancient ostraca (inscribed broken pottery) dating back to 1600 BC. Although I haven’t found a definitive source for this (or why tiger nut balls don’t contain tiger nuts!) they sounded too delicious to pass over. As your average ancient Egyptian seems to have had a very sweet tooth and often added dates and honey to desserts, I like to think that this is a sweet that would have been made thousands of years ago.

This recipe is very straightforward, requires no cooking and is a lot fun to make (ideal for younger members of the household who might want to help).

Ingredients

• 200g fresh dates (I used dried, which worked really well)

• 1 tsp cold water

• 10–15 walnut halves

• ¼ tsp of cinnamon

• small jar of runny honey

• 75g ground almonds

Method

Chop the dates finely (use seedless, or make sure to remove the stones first) and put them into a bowl. Add the water and stir. Then mix in the chopped walnuts and the cinnamon.

Shape the mixture into small balls with your hands. Dip the balls in honey (I warmed it first so the honey coating wouldn’t be quite so thick) then roll the balls in the ground almonds.

Chill them in the fridge for half an hour before serving.

BBC history Magazine team verdict:

“Like historic energy balls.”

“I think Tiger nut balls roar with flavour.”

“They’re as indulgent as a chocolate truffle!”

Difficulty: 1/10

Time: 45 mins

Recipe courtesy of Cook it!

In every issue of BBC History Magazine, picture editor Sam Nott brings you a recipe from the past. In this article, Sam recreates a healthy snack thought to have been enjoyed in Egypt around 3,500 years ago.

If you, like me, have a sweet tooth but are trying to be healthier then try tiger nut balls.

I found lots of references to this being one of the first Egyptian recipes that we know of, found written on an ancient ostraca (inscribed broken pottery) dating back to 1600 BC. Although I haven’t found a definitive source for this (or why tiger nut balls don’t contain tiger nuts!) they sounded too delicious to pass over. As your average ancient Egyptian seems to have had a very sweet tooth and often added dates and honey to desserts, I like to think that this is a sweet that would have been made thousands of years ago.

This recipe is very straightforward, requires no cooking and is a lot fun to make (ideal for younger members of the household who might want to help).

Ingredients

• 200g fresh dates (I used dried, which worked really well)

• 1 tsp cold water

• 10–15 walnut halves

• ¼ tsp of cinnamon

• small jar of runny honey

• 75g ground almonds

Method

Chop the dates finely (use seedless, or make sure to remove the stones first) and put them into a bowl. Add the water and stir. Then mix in the chopped walnuts and the cinnamon.

Shape the mixture into small balls with your hands. Dip the balls in honey (I warmed it first so the honey coating wouldn’t be quite so thick) then roll the balls in the ground almonds.

Chill them in the fridge for half an hour before serving.

BBC history Magazine team verdict:

“Like historic energy balls.”

“I think Tiger nut balls roar with flavour.”

“They’re as indulgent as a chocolate truffle!”

Difficulty: 1/10

Time: 45 mins

Recipe courtesy of Cook it!

Published on April 30, 2017 01:30

April 29, 2017

Legendary Lost City of Ucetia Has Been Found and Its Remains are Breathtaking

Ancient Origins

Through the years, people have seen tantalizing mentions of the lost ancient Roman city of Ucetia on stelae in southern France. But until now, there was no evidence that it really existed. However, when archaeologists were brought in to assess a site for a new school and canteen, they found abundant evidence of the lost city of Ucetia outside the modern town of Uzés, which is near Nimes. And what they found was simply stunning.

The team of archaeologists, led by Philippe Cayn of the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research, found footprints of several buildings, one of which had magnificent tile mosaics on the floor. It is unknown whether this building was a public or private one, but Cayn said the presence of a colonnade and the mosaic in the 250 square meter (820 square feet) building may indicate a public purpose.

Cayn told IBITimes.co.uk:

"Prior to our work, we knew that there had been a Roman city called Ucetia only because its name was mentioned on stela in Nimes, alongside 11 other names of Roman towns in the area. It was probably a secondary town, under the authority of Nimes. No artefacts had been recovered except for a few isolated fragments of mosaic.”

Cayn told the website that the mosaic is very impressive for its size, the motifs of geometric shapes and animals and because it is well-preserved. He said sophisticated mosaics were common among the Romans in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, but this one is surprising because it is much older. It goes back about 200 years earlier, to the 2nd or 1st century BC.

One of the mosaics had in one corner an eagle—a symbol of ancient Rome and many other regimes around the world through history. (Copyright Denis Gliksman of INRAP)

Overall, the site is 4,000 square meters (13,000 square feet). The team ascertained that people lived in Ucetia from around the 1st century BC until the 3rd or 4th century AD, when the city was abandoned. The reason people left Ucetia is a mystery to the researchers, but people again lived there from the 4th to the 7th centuries AD. Archaeologists also found a few ruins from the Middle Ages.

The Roman conquest of the area occurred in the late 2nd century BC. The researchers found a wall and remnants of several other structures dating to just before the Romans occupied the area. One of these ruins was a room with a bread oven. At some point the room was later converted to a space with a dolium—a large ceramic container. Dolia were made of fired clay and were up to 6 feet tall (1.83 meters) tall. People used them to store food and beverages, including grains and wine.

This is the foundation of a building dating to the 7th century AD. The entire site lies near the modern city of Uzes. Evidence of the first people first to live in Ucetia goes back to around the 2nd century BC. Authorities found the ancient town when archaeologists surveyed and excavated to find any old buildings in 2016 to prepare for construction of a school. (Photo copyright Denis Gliksman of INRAP)

Of the greatest interest to INRAP, Ibitimes.co.uk says, were the mosaics. They depicted traditional geometric shapes and medallions, including chevrons, rays and crowns. One of the medallions is adorned with images of a fawn, a duck, an eagle and an owl.

It is possible the building in which the mosaics were made was the foyer of a rich person’s home. Cayn said the mosaics and colonnades may have been meant to impress visitors.

Top image: One of the beautiful mosaics was surrounded by images of a fawn, duck, eagle and owl. (Copyright Denis Gliksman of INRAP)

By Mark Miller

Through the years, people have seen tantalizing mentions of the lost ancient Roman city of Ucetia on stelae in southern France. But until now, there was no evidence that it really existed. However, when archaeologists were brought in to assess a site for a new school and canteen, they found abundant evidence of the lost city of Ucetia outside the modern town of Uzés, which is near Nimes. And what they found was simply stunning.

The team of archaeologists, led by Philippe Cayn of the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research, found footprints of several buildings, one of which had magnificent tile mosaics on the floor. It is unknown whether this building was a public or private one, but Cayn said the presence of a colonnade and the mosaic in the 250 square meter (820 square feet) building may indicate a public purpose.

Cayn told IBITimes.co.uk:

"Prior to our work, we knew that there had been a Roman city called Ucetia only because its name was mentioned on stela in Nimes, alongside 11 other names of Roman towns in the area. It was probably a secondary town, under the authority of Nimes. No artefacts had been recovered except for a few isolated fragments of mosaic.”

Cayn told the website that the mosaic is very impressive for its size, the motifs of geometric shapes and animals and because it is well-preserved. He said sophisticated mosaics were common among the Romans in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, but this one is surprising because it is much older. It goes back about 200 years earlier, to the 2nd or 1st century BC.

One of the mosaics had in one corner an eagle—a symbol of ancient Rome and many other regimes around the world through history. (Copyright Denis Gliksman of INRAP)

Overall, the site is 4,000 square meters (13,000 square feet). The team ascertained that people lived in Ucetia from around the 1st century BC until the 3rd or 4th century AD, when the city was abandoned. The reason people left Ucetia is a mystery to the researchers, but people again lived there from the 4th to the 7th centuries AD. Archaeologists also found a few ruins from the Middle Ages.

The Roman conquest of the area occurred in the late 2nd century BC. The researchers found a wall and remnants of several other structures dating to just before the Romans occupied the area. One of these ruins was a room with a bread oven. At some point the room was later converted to a space with a dolium—a large ceramic container. Dolia were made of fired clay and were up to 6 feet tall (1.83 meters) tall. People used them to store food and beverages, including grains and wine.

This is the foundation of a building dating to the 7th century AD. The entire site lies near the modern city of Uzes. Evidence of the first people first to live in Ucetia goes back to around the 2nd century BC. Authorities found the ancient town when archaeologists surveyed and excavated to find any old buildings in 2016 to prepare for construction of a school. (Photo copyright Denis Gliksman of INRAP)